Abstract

Background/Aims

The obesity epidemic has spread to young adults, and obesity is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. The prominence and increasing functionality of mobile phones may provide an opportunity to deliver longitudinal and scalable weight management interventions in young adults. The aim of this manuscript is to describe the design and development of the intervention tested in the Cell Phone Intervention for You (CITY) study and to highlight the importance of adaptive intervention design (AID) that made it possible. The CITY study was an NHLBI-sponsored, controlled 24-month randomized clinical trial (RCT) comparing two active interventions to a usual-care control group. Participants were 365 overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2) young adults.

Methods

Both active interventions were designed based on social cognitive theory and incorporated techniques for behavioral self-management and motivational enhancement. Initial intervention development occurred during a 1-year formative phase utilizing focus groups and iterative, participatory design. During the intervention testing, AID, where an intervention is updated or extended throughout a trial while assuring the delivery of exactly the same intervention to each cohort, was employed. The AID strategy distributed technical work and allowed introduction of novel components in phases intended to help promote and sustain participant engagement. AID was made possible by exploiting the mobile phone's remote data capabilities so that adoption of particular application components could be continuously monitored and components subsequently added or updated remotely.

Results

The cellphone intervention was delivered almost entirely via cell phone and was always-present, proactive, and interactive – providing passive and active reminders, frequent opportunities for knowledge dissemination, and multiple tools for self-tracking and receiving tailored feedback. The intervention changed over two years to promote and sustain engagement. The personal coaching intervention, alternatively, was primarily personal coaching with trained coaches based on a proven intervention, enhanced with a mobile application, but where all interaction with the technology was participant-initiated.

Conclusions

The complexity and length of the technology-based RCT created challenges in engagement and technology adaptation, which were generally discovered using novel remote monitoring technology and addressed using the AID. Investigators should plan to develop tools and procedures that explicitly support continuous remote monitoring of interventions to support AID in long-term, technology-based studies, as well as developing the interventions themselves.

Keywords: Weight loss, weight maintenance, intervention, mobile technology, adaptive clinical trial, lifestyle

Introduction

The obesity epidemic has spread to young adults and is a significant risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Rapid weight gain occurs during the early adult years, but effective strategies to curb the trend are lacking. Mobile technology is well suited for delivering weight loss interventions to a large segment of the population, particularly young adults because of their frequent and regular usage of mobile phones. Currently, mobile phone penetration in the US is about 104%1 (more than one phone per person) with nearly 90% of adults using mobile phones2 and accessing as much as 150 times per day.3 The phones can prompt for action or information, display tailored, multi-media content, measure motion, send and receive data to and from the Internet – all features with potential for delivering a weight loss intervention. Not surprisingly, there is increasing interest in delivering weight loss interventions via mobile phones. Examples include weight loss studies using mobile phones to send one-way text messages to participants as reminders.4-7 Commercial weight loss mobile applications are used by millions of people, at least for short periods of time, but few have been vigorously tested and proven effective, especially for two or more years.

Further, translating theoretical constructs and intervention designs that have been successfully delivered by human coaches into applications delivered by mobile phone, with the objectives of creating coherent, integrative, acceptable and engaging interaction that leads to behavior change, is important but rarely studied. The main challenge is the limitations in the ability of software to reason about behavior in the sophisticated way that a person can; this increased the need to adapt software to meet needs in other ways. In the Cell Phone Intervention for You (CITY) study, a NHLBI-sponsored, randomized clinical trial (RCT), we sought to create and test a fully-automated weight loss intervention that could be widely deployed and work well for two years, helping young adults achieve and sustain weight loss.

This paper describes the intervention design process of CITY, the two active interventions that resulted from that process, and observations on how the design and use of the longitudinal mobile intervention impacted the execution of this RCT. Documentation of previous mobile intervention design processes and outcomes is often lacking; this manuscript provides details so that the intervention components may be understood and improvements may be made in future studies.

Methods

Overall design

CITY was a RCT comparing two active interventions for weight loss with a usual-care control group in young adults -- a cellphone intervention and a personal coaching intervention. A total of 365 participants were recruited who were 18-35 years, overweight or obese (BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2), and using a mobile phone. Participants were recruited in four cohorts from January, 2011 to April, 2012 so that recruitment could be paced with available resources and staffing. The intervention was delivered to each cohort of participants with exactly the same time schedule, amount of intervention exposure and content. Data collected from all cohorts were combined in the final statistical analyses by a constrained longitudinal data analysis model to estimate changes in absolute weight over time.8 The main outcome of the study was weight change at 24 months. A description of the main study design has been published elsewhere.9

Design goals of the CITY interventions

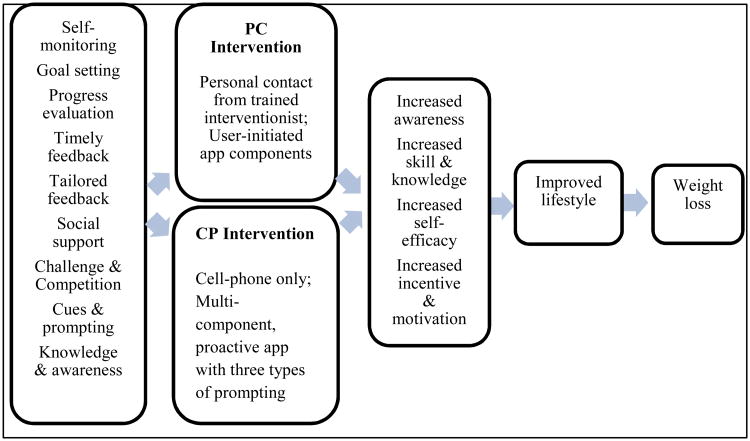

Both the cellphone and personal coaching interventions were generally rooted in social cognitive theory10 and techniques of behavioral self-management.11 They also employed the trans-theoretical, stages-of-change model12,13 and used motivational enhancement approaches.14 The behavioral framework for both interventions (Figure 1) was based on the previous proven intervention programs where significant weight loss was achieved in six months.15,16 Further, Table 1 lists the lifestyle guidelines that were incorporated into various elements of both interventions for weight loss. We hypothesized that by implementing the behavioral strategies, participants could increase awareness about lifestyle behaviors, gain self-efficacy and enhance motivation to change and thus improve lifestyles, resulting in eventual weight loss.

Figure 1. Behavioral framework for CITY intervention.

Table 1. Lifestyle guidelines incorporated throughout both personal coaching and cellphone interventions.

| Guidelines: | Recommended targets: |

|---|---|

| 1. Weigh yourself | Weigh yourself at least weekly |

| 2. Keep calories in moderation | For women: consume approximately 1500-1800 calories/day to lose weight For men: consume approximately 2000-2300 calories/day to lose weight |

| 3. Exercise regularly | Gradually increase to at least 180 minutes of moderate intensity activity per week |

| 4. Keep records of what you eat | Keep records of what you eat for at least 4 days a week |

| 5. Limit alcohol intake | Limit to one drink per day for women and two for men |

| 6. Stay connected with the study | Attend all study meetings and visits |

The personal coaching intervention was delivered mainly via a trained coach. The coach was trained in motivational interviewing techniques supplemented with a mobile application configured to allow self-monitoring but without any prompting or proactive presentation of information on the phone screens.

The cellphone intervention, alternatively, was delivered nearly entirely through a fully-automated mobile application that included several mechanisms to prompt extensively with information and gather data. The mobile application was made available to the participants post randomization but different components (goal setting, food tracker, etc.) of the application were delivered in stages throughout the 24-month study period. In order to adapt to the rapidly changing mobile phone hardware and operating system constraints, and user expectations about the technology, we employed the adaptive intervention design (AID) approach, where an intervention was updated or extended throughout a trial while assuring the delivery of exactly the same intervention to every participant.

Intervention content development

Initial CITY intervention development occurred during a 1-year formative phase. The intervention was further developed and refined over the 24-month period for the first cohort. Once the first cohort was randomized, it became the pioneer cohort of an adaptive intervention.17 Starting with the goals described earlier, four strategies were used when developing the intervention in the formative phase and beyond: 1) focus groups for idea generation, 2) single-person participatory design sessions for usability evaluation and improvement, 3) technical testing, and 4) phased rollout of the intervention content. These steps were followed by iterative content development based on actual application usage for system refinement and improvement.

Focus groups

Nominal group technique was used in conducting six group discussions with 33 members sharing the same characteristics as that of the target population. The results of the focus groups informed the advertising strategies, including message framing, advertising avenues, preferred format and intervention content.18

Iterative and participatory design

Participatory design is a technique for developing software where potential users are engaged in the process of design creation.19 In this project, paper prototypes20 of application components were developed, tested and refined with the input of young adults. The paper interfaces were further adapted, and then prototype software was developed.

Technical testing

During the formative phase, extensive testing was performed to select an operating system that would support motion sensing, transmit motion data simultaneously to study database, remote data upload, and intensive prompting. Once application components were prototyped, the research team, mainly represented by young adults with diversity in gender, race and ethnicity, tested the components extensively before releasing to study participants.

Phased roll-out

A phased roll-out approach was used in delivering application components in order to: (1) meet the fast pace of technical improvements, (2) implement procedural improvements and testing (which could not be tested adequately before release of the application components), (3) manage technical challenges and distribution of work (i.e., it was unrealistic to build the entire system at the outset, especially given technical testing and the constantly changing mobile technology), and (4) enhance and/or maintain engagement.

Ongoing content development and application updating

The intervention framework remained the same from enrollment to the end of the study for all participants and guided the development of the specific intervention content to achieve the behavioral goals. At roll-out, addition of some new content was planned. However, in most cases, content was also added in response to intervention monitoring, as described below.

Adaptive intervention design (AID)

Engagement data from the first cohort's experiences were used to inform, select and design application components that would be introduced later during the 24-month intervention. Each subsequent cohort was exposed to the same intervention components at the same time. For example, the physical activity tracker was delivered in month 3 for all participants regardless of their enrollment date. As various application components were launched, engagement data were reviewed and participant feedback received, study investigators and staff considered both enhancements to existing application components and the introduction of new components. Engagement data were obtained in two ways: (1) server-side software collected data that was uploaded daily from mobile phones and generated reports about how participants were using the application or specific components (e.g., taking weight measurements), and (2) qualitative reports on the software usage were obtained when study staff communicated with participants during the “check in” calls every six months. The supplemental “check in” calls were included for the cellphone intervention group only to confirm proper functioning of the phone application, to conduct a progress check, and to problem solve if deemed helpful to the participants. At the first “check in” calls at six month only, three specific questions were used to solicit participant feedback: 1. What do you like or dislike about the existing CITY phone applications, 2. What changes or new additions would you like to see on the CITY phone applications that can help with your weight loss, and 3. How is the prompting working or not working for you. Feedback was reviewed within the study team and modification to the application was made when the modification was expected to be useful for weight loss and feasible with existing resources.

None of the changes of the intervention content occurred within a month prior to any data collection visit, and all changes except bug fixes were introduced at the same time (and in the same way) for all four cohorts to maintain the integrity of the RCT by delivering exactly the same intervention to every cohort. This constraint, as well as the need to ensure data stored on phones in early phases of the study were not lost or ignored because of any future changes (i.e., maintaining backwards compatibility), introduced additional technical constraints.

Results

Below is the detailed description of the two active interventions that resulted from the process described above, as the research team responded to the use of the application and the evolution of mobile phone technology over the course of the two-year intervention.

Personal coaching intervention

Participants randomized to the personal coaching intervention attended six weekly group sessions (each ≈2 hr), with the first scheduled within four weeks after randomization. The sessions were conducted by a trained coach and included 5 to 10 participants. At the conclusion of all six group sessions, participants received a monthly coaching call (each ≈10-20 min) from the coach for the rest of the study. The outline and key topics for each group session are listed in Table 2. The structure for the monthly calls included a progress check, followed by discussion driven by the participant, and ending with goal setting and action planning. The coach reviewed each participant's progress quarterly with the intervention team to detect at-risk behaviors and develop strategies to help the participants with behavior change. No other intervention contact was made between the coach and participants outside group sessions and monthly phone coaching.

Table 2.

Topics discussed with personal coaching group participants and a trained interventionist during each of the 6 weekly group sessions at the outset of the personal coaching intervention.

| Group session | Overall Emphasis | Lifestyle Behavioral Weight Management Information & Skills | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| General | Diet | Activity | ||

| 1 | Introduction & orientation | Self-monitoring; lifestyle patterns; change plan | Eating Plan; DASH & diet monitoring; weight loss myths; application appetite awareness | Physical activity plan & monitoring |

| 2 | Mindfulness | Goal setting | Calorie goals; food groups; food labels; portion control vs. serving size; conscious eating | Formal exercise vs. lifestyle activity |

| 3 | Setting priorities | Setting priorities; value sort | Fat & sodium; sugar; social eating & eating out; review calorie goals | Review past logs & find ways to increase activities |

| 4 | Managing stress & thoughts & behavior | Thoughts & the thought of behavior change; stress management; triggers/cravings | Potassium; fruits & vegetables; low fat dairy foods | Physical activity barriers and goals |

| 5 | Social support | Social relationships & influence on making changes; asking for support; continuing weight loss after group sessions | Grains; meats and other protein foods; alcohol; implementing change | Physical activity that can be done with partners; finding enjoyable activities |

| 6 | Relapse prevention | Review negative thoughts & influence on making changes; relapse prevention & high risk situations | Meal planning; healthy snacks; review portion control | Increasing lifestyle activities & calorie burning; monitoring intensity of physical activities |

To supplement coaching, personal coaching participants were encouraged to use the selected CITY cellphone application for tracking weight, diet and physical activity. However, the application available to this group was entirely passive, only accessible via a standard application icon, did not proactively present with information or prompt for information, and was unlikely to be seen every time the participants used their phones. Participants only received reminders about using the application from the coach.

In addition, participants were given a scale (HD-351BT, Tanita Corp, Tokyo, Japan) that could communicate with the CITY application wirelessly via Bluetooth to record weight readings. The CITY application uploaded the weight and application usage data to the research server, and these data were available to the coach. This allowed the coach to know, for example, if a participant was taking weight measurements regularly, and to discuss such behavior (or lack of it) on the monthly calls. Table 3 describes the purpose and function of each component of the CITY application, highlighting as well where the capabilities diverged between the two interventions.

Table 3. Description of the major components of the CITY application, noting differences between the cellphone and personal coaching versions*.

| Application component (sample screenshots) | Behavioral goals | Cellphone application version | Personal coaching application version |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tutorial (Fig 2a) | Skill building |

|

|

| Phone “Live wallpaper” displaying tips, links, and facts (Fig 2b) | Skill building, peripheral and persistent visual reminder |

|

|

| Weighing (Fig 2c, 2d) | Self-monitoring, feedback |

|

|

| Food tracking (Fig 2e,2f,2g) | Self-monitoring, feedback |

|

|

| Physical activity tracking (Fig 2h) | Self-monitoring, feedback |

|

|

| Buddy system (Fig 2i) | Social support, accountability |

|

|

| Goal setting (Fig 2j) | Goal setting |

|

|

| Countdown (Fig 2k) | Goal setting |

|

|

| Challenge/game (Fig 2l, 2m) | Motivation enhancement |

|

|

| Rewards and feedback (Fig 2n, 2o) | Positive reinforcement |

|

|

Not listed here are components for getting help on the application.

In the personal coaching group, the coaches adapted responses to individuals. Coaches received feedback from participants directly, and were assisted by the remote data collection ability of the application. The remote monitoring tools therefore proved valuable, but the intervention adaptation itself could primarily be done without updating the technology itself, in contrast to the cellphone intervention.

Cellphone intervention

The cellphone intervention was designed following the same behavioral framework (Figure 1) but was implemented for a mobile phone – no frequent interaction with a live coach was required. The cellphone application had ten components that covered several behavioral strategies (Table 3).

In addition, the cellphone application incorporated the same lifestyle guidelines (Table 1) that were used in the personal coaching intervention, all of which have been shown previously to be important in behavioral change.15,21 Figure 2 shows screenshots of some of the components. Whenever appropriate, the application components were designed to help the participants in following the study guidelines. For example, the food tracking component that allowed detailed entry of food intake showed the total calories consumed up to that point and the balance left for that day based on the study guidelines. These participants were also provided a wireless scale that could send readings to the mobile application.

Figure 2. Sample screenshots of components of the CITY application.

Prompting and application introduction schedule

A primary component of the cellphone intervention was proactive and tailored prompting, where the application used audio, vibration, and/or turning on the screen to get the participant's attention and present information or challenges. The application used three types of prompting: (1) peripheral prompting, (2) notification prompting, and (3) full-application-interruption prompting. Table 4 describes in more detail the nature and disruptive level of the promptings and how they were used in the CITY application. The prompting schedule for each application component was determined based on the team's best judgment of what may help the participants the most in making lifestyle changes for weight loss. Generally, most prompting in the early part of the study was the extensive full-application-interruption prompting desired to help participants establish a habit of self-monitoring, along with peripheral prompting on the live wallpaper and phone lock screen. Less disruptive notifications were introduced gradually more after the first four months. On average, participants were full-application-interruption prompted 2.7 times/day for the first four months, which then decreased to about 1.6 times/day for remainder of study.

Table 4.

Description of the different types of promptings used by the Cellphone application.

| Type of prompting | Nature | Level of disruption | Application in CITY |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral | Provides an “always on” reminder to gently remind the participant that s/he is focused on weight loss. No audio or vibration prompting is used with this technique, but this mechanism requires that the participant leave the application setup to provide the phone's “live wallpaper” (as shown in Figure 2b). | Least disruptive but prohibits use of wallpaper for other things. | Presents information on the phone's home screen and lock screen, so that whenever the participant uses the phone, which for young adults can be tens of times per day3, there is a chance that a message related to the weight loss goal might be seen. |

| Notification prompting: ephemeral | Recommended strategy to queue messages to users. Messages create a tone or vibration when they are presented, and they briefly show up at the top of the phone screen. Subsequently, an icon appears at the top of the phone, and when the user “pulls down” the top bar they see a list of all notifications in the notification “window shade.” Tapping on a notification can launch a relevant component of the CITY application. | Standard method of notification on phones. They can clutter up the notification bar and become intermixed with other notifications for text messages, emails, and phone calls, and people can become desensitized to them, clearing them in bulk without reading them. |

This notification can be dismissed once viewed. In addition to those generated by CITY, ephemeral notifications were generated by the participants in the form of “buddy messages,” an anonymous and limited form of text messaging for between-buddy communication. Each buddy message had a CITY application component associated with it, and on receiving a message notification from a buddy, a participant could choose to open the relevant component. Figure 2b shows a peripheral prompt. |

| Notification prompting: Persistent | Persistent notifications remain active all the time and can be seen any time the participant checks any other notification (e.g., when viewing a text message or checking who called the phone). | Same as ephemeral notifications. Without sustained refreshing of content on the notifications, they run the risk of quickly “fading into the background” and becoming ignored. |

Figure 2o shows a persistent notification bar prompt. |

| Full-application interruption prompting | The phone plays an audio chime, vibrates, turns on the phone's display, and then pops a relevant application component to the foreground on the phone. If the phone is set to no-audio mode, the phone will only vibrate and turn on the display, and if the phone is set to silent mode only the display will come on. The application will remain present for 10 minutes, so if the participant accesses the phone (unlocking it) within that time, the application that was prompted will be present. | Most aggressive. Application components pop to the foreground regardless of what the participant is doing on the phone. |

Figure 2c shows a typical full-screen prompt |

The adaptive intervention design (AID)

The AID allowed development of intervention throughout the end of cohort 1 while keeping exactly the same intervention framework and specific content for all cohorts to achieve the same behavioral goals. Unlike in the personal coaching group where coaches tailored the intervention, the cellphone intervention was adapted by remotely updating the software. Although some qualitative feedback was obtained from some participants in “check in” calls, systematic adaptation mainly took place by considering the following elements.

Refreshing/changing content to simulate engagement. To generate new enthusiasm among participants, new content or entire new components were periodically added. This is based on the common belief that content and delivery must change frequently in order to sustain interest.

-

Resolving technical problems. Although all application components were tested prior to release to study participants, technical problems arose due to a variety of factors: (1) software errors (“bugs”) not uncovered during testing, (2) inconsistencies in the Android operating system between phone models that created software errors, (3) inconsistencies between capabilities of some phone models that prevented use of some application features, and (4) unanticipated user behavior that required software changes to fully accommodate. Other technical issues were experienced during the initial phase of the intervention delivery ranging from difficulty transferring a participant's own phone contract and data to study phones, to limited battery life, unexpected phone freezing and restarting, malfunctioning chargers, corrupted SD memory cards, and problems uploading data reliably and automatically. When participants broke or lost the phone hardware or a phone was malfunctioning in an unexplainable way, the phones were replaced by the study.

At times, mobile phone service providers and manufacturers updated features of the Android operating system that interfered with the function of certain phone features, such as sensing and prompting. In these cases, participants would experience a temporary interruption of the usage of study application, and study staff would have to spend extra time diagnosing and fixing technical problems. A related problem was that any technical issue could create gaps in the data being collected by the phone. Teasing apart the source of unexpected or missing data – was it user behavior, an error in our application, a manufacturer software limitation, or a broken phone – could often be challenging, especially given some participants were difficult to contact. Future studies should develop resources and procedures to handle such needs.

Supplementing features that showed clear engagement falloff. By monitoring engagement data, showing use of various components of the application, the team could identify when a component was used less than anticipated or desired, and in some cases changes to applications were made in response. For example, daily weighing was emphasized throughout the study because regular weighing has been shown to be effective for weight loss.22 The weight tracker component provided meaningful, objective feedback to participants for relatively little user effort. This may help to explain the relatively high engagement levels observed in self-weighing relative to other application components initially. Although this engagement pattern started high, the pattern still trended downward soon after launching; thus, effort was made to enhance this component, by adding a tailored weight graph. In addition, email and text messages were automatically sent to participants in response to weight measurements, predicting their weight trend based on the current weight.

Participants' feedback sent through the application. Initially, when the weight trend prediction was released, it displayed on the live wallpaper peripheral notification component that showed on the phone screen when unlocked. Several participants subsequently expressed concerns about others seeing their weight information if they shared their phone (indicating that they were paying attention to the peripheral messages). In response, the application was changed to provide the prediction information through email and text messages. This demonstrates how the strategy of peripheral, continual awareness conflicts with expectations about phone usage patterns. Similarly, at the start of this study, asking participants to customize their phone background seemed reasonable, but phone customization has now become so common and important to young adults that peripheral display of information may need to occur through less obvious but more widely accepted phone notification mechanisms.

Introducing new behavioral elements. During the formative phase, some desired behavioral elements (for example, social support) could not be implemented in time for the launch of the study. These elements were added to the application for the first cohort as they progressed through the study and delivered at the same study month for all following cohorts.

Simplifying behavioral elements. As it became apparent that the components of the application that required the simplest interactions were used more, efforts were made to simplify some tracking because participants presumably need less guidance for self-monitoring over time and simpler interaction may be used more. For example, the healthy meal tracker was developed as an alternative to the detailed food tracker.

Discussion

The personal coaching intervention was designed based on many previous trials and did not rely as heavily on the technology as the cellphone intervention, and so the most serious challenges and greatest opportunities for innovation were experienced for the cellphone intervention.

The cellphone intervention was designed with the goal of translating multiple components of traditional coaching into a comprehensive mobile phone application. As expected, many features of traditional coaching could not be directly automated on the phone with the available technology, because most successful weight loss interventions require skilled professionals. These professionals listen to the participants, perform cognitive tasks such as problem solving, build rapport and trust, tailor feedback using motivational interviewing, and provide tailored guidance. Nevertheless, effort was made such as in capturing the spirit of motivational interviewing by incorporating praising (e.g., “Great job weighing yourself today!”) and evoking “change talk” from patients (e.g., “What are some good things that could come from making healthy food choices?”) when sending messages to the participants.

Another major challenge that we anticipated was maintaining engagement. Frequently changing content and delivery style may help to sustain interest, especially for the targeted 18-35 year olds, who are used to constant change in their electronic environment. To generate enthusiasm among participants, new components and content were added periodically to the application. This was only logistically possible because we could remotely and automatically update the application. Thus, the remote monitoring of engagement data was essential to maximize the usefulness of the AID approach.

Companies making popular mobile weight loss applications do not generally report on long-term compliance or weight-loss outcomes, but some previous studies showed rapid deterioration in usage of commercial applications and fitness monitoring devices.23,24 We are unaware of independent research validating most applications. Although 50 million mobile applications are downloaded every day, it is reported that 95 percent are abandoned within a month and less than five percent of smartphone owners are still using free applications 30 days after downloading them.25 Not unexpectedly, we observed that participant engagement with some application components decreased quickly after they were introduced. We staged rollout of features to offset such attrition within the constraints of the RCT and available resources, updated and improved the study application as much as feasible. Participants may have been motivated by our application to try out commercial applications, which may be more polished/complete than some of our components (e.g., detailed food tracker), but it was beyond the scope of this study to track the usage of other commercial applications.

By design, the cellphone application periodically prompted cellphone participants to complete certain tasks such as weighing or tracking food intake. Some participants may be annoyed by the prompting to the point of uninstalling the applications or turning off the phone, either of which interrupted the data transmission process. Emails and text messages were sent to the participants who appeared to have uninstalled the application. The tension and balance between the researcher's desire to prompt, which does seem to increase engagement in other short intervention studies,26 and a participant's desire to not be interrupted deserves further exploration.

There are many improvements that could be made to the CITY intervention but were not possible given limited time and resources. For example, the tutorials might be made to be more interactive, with components that ask participants to reflect deeply on the content and that link to other application components. The weight tracker might be improved with more sophisticated weight trend prediction, tying the weight tracker with healthy meal tracker and social networking components more explicitly. The buddy system could be made even more interactive and to elicit more accountability and support. Overall, the application might be improved by more creative strategies for customizing prompting further. Analysis of the extensive data generated by the CITY study on the usage of the various components, the response to prompting, and the type of information that was entered by participants may help us determine which improvements are most worth exploring in future work. Ultimately, the relationship between usage of cellphone components and weight loss will drive future development.

Conclusion

The CITY study is unique in its goal of studying a 24-month weight loss intervention for young adults, with the cellphone intervention delivered nearly entirely on mobile phones. The mobile application developed and described here creates unique opportunities to interact with participants using three prompting strategies and a suite of application components that creatively implemented a variety of behavior change strategies ranging from tailoring to goal setting. While the technology creates new opportunities for health behavior intervention, the use of technology also creates challenges in terms of the design and execution of the clinical trial. Overall, the fast changing nature of the phone technology and young adults' expectations about their phones are, in some respects, in conflict with some of the constraints required for a RCT. The development of the technology-based RCT required a collaborative, iterative effort between lifestyle intervention trialists and mobile technology experts lasting over five years, and the complexity and length of the study created challenges in engagement and technology adaptation, which were generally discovered using novel remote monitoring technology and addressed using the AID approach.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: NIH 5U01HL096720

Abbreviations

- AID

Adaptive intervention design

- RCT

Randomized controlled trial

- CITY

Cell Phone Intervention for You

Footnotes

Clinical trials registry: NCT01092364

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to report.

References

- 1.CTIA. CTIA wireless industry indices. CTIA; 2014. US wireless quick facts. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pew Research internet project. Pew Research Center; 2014. Mobile technology fact sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meeker M, Wu L. 2013 internet trends. Kleiner Perkins Caufield Byers. 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw RJ, Bosworth HB, Silva SS, et al. Mobile health messages help sustain recent weight loss. Am J Med. 2013;126:1002–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joo NS, Kim BT. Mobile phone short message service messaging for behaviour modification in a community-based weight control programme in Korea. J Telemed Telecare. 2007;13:416–420. doi: 10.1258/135763307783064331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newton KH, Wiltshire EJ, Elley CR. Pedometers and text messaging to increase physical activity: randomized controlled trial of adolescents with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:813–815. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuoka Y, Vittinghoff E, Jong SS, et al. Innovation to motivation--pilot study of a mobile phone intervention to increase physical activity among sedentary women. Prev Med. 2010;51:287–289. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu GF, Lu K, Mogg R, et al. Should baseline be a covariate or dependent variable in analyses of change from baseline in clinical trials? Stat Med. 2009;28:2509–2530. doi: 10.1002/sim.3639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Batch BC, Tyson C, Bagwell J, et al. Weight loss intervention for young adults using mobile technology: design and rationale of a randomized controlled trial - Cell Phone Intervention for You (CITY) Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bandura A. Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson DT. Self-directed behavior: Self-modification for personal adjustment. 5th. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–395. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.51.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prochaska JO, Velicer WF, Rossi JS, et al. Stages of change and decisional balance for 12 problem behaviors. Health Psychol. 1994;13:39–46. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.13.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing : preparing people for change. 2nd. Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the weight loss maintenance randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Appel LJ, Champagne CM, Harsha DW, et al. Effects of comprehensive lifestyle modification on blood pressure control: main results of the PREMIER clinical trial. JAMA. 2003;289:2083–2093. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.16.2083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patrick K, Marshall SJ, Davila EP, et al. Design and implementation of a randomized controlled social and mobile weight loss trial for young adults (project SMART) Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;37:10–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corsino L, Lin PH, Batch BC, et al. Recruiting young adults into a weight loss trial: report of protocol development and recruitment results. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Muller MJ, Kuhn S. Participatory design. Commun ACM. 1993;36:24–28. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rettig M. Prototyping for tiny fingers. Commun ACM. 1994;37:21–27. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svetkey LP, Harsha DW, Vollmer WM, et al. Premier: a clinical trial of comprehensive lifestyle modification for blood pressure control: rationale, design and baseline characteristics. Ann Epidemiol. 2003;13:462–471. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(03)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Steinberg DM, Tate DF, Bennett GG, et al. The efficacy of a daily self-weighing weight loss intervention using smart scales and e-mail. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21:1789–1797. doi: 10.1002/oby.20396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trefren T. Social game developers use tutorials to get crucial early retention. [accessed 30 March 2015];2010 http://www.adweek.com/socialtimes/mixpanel-social-game-developers/571441.

- 24.Ledger D, McCaffrey D. How the science of behavior change offers the secret to long-term engagement. [accessed 30 March 2015];Endeavour Partners LLC. 2014 http://endeavourpartners.net/assets/Endeavour-Partners-Wearables-White-Paper-20141.pdf 2014.

- 25.Gary R. Why 95% of mobile apps are abandoned-and tips to keep your apps from becoming part of that statistic. 20. Nuance Communications, Inc.; Nov, 2011. pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Consolvo S, McDonald DW, Toscos T, et al. Activity sensing in the wild: a field trial of ubifit garden. Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on human factors in computing systems; Florence, Italy. ACM; 2008. pp. 1797–806. [Google Scholar]