Abstract

Background

Prevalence of smoking in diabetic patients remains high, and reliable quantification of the excess mortality and morbidity risks associated with smoking is important for diabetes management. We performed a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to evaluate the relation of active smoking with risk of total mortality and cardiovascular events among diabetic patients.

Methods and Results

We searched MEDLINE and EMBASE databases through May 2015, and multivariate-adjusted relative risks (RRs) were pooled using random-effects models. A total of 89 cohort studies were included. The pooled adjusted RR (95% confidence interval [CI]) associated with smoking was 1.55 (1.46–1.64) for total mortality (48 studies with 1,132,700 participants and 109,966 deaths), and 1.49 (1.29–1.71) for cardiovascular mortality (13 studies with 37,550 participants and 3,163 deaths). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.44 (1.34–1.54) for total cardiovascular disease (CVD; 16 studies), 1.51 (1.41–1.62) for coronary heart disease (CHD; 21 studies), 1.54 (1.41–1.69) for stroke (15 studies), 2.15 (1.62–2.85) for peripheral arterial disease (3 studies), and 1.43 (1.19–1.72) for heart failure (4 studies). Compared to never smokers, former smokers were at a moderately elevated risk of total mortality (1.19; 1.11–1.28), cardiovascular mortality (1.15; 1.00–1.32), CVD (1.09; 1.05–1.13) and CHD (1.14; 1.00–1.30), but not for stroke (1.04; 0.87–1.23).

Conclusions

Active smoking is associated with significantly increased risks of total mortality and cardiovascular events among diabetic patients, while smoking cessation was associated with reduced risks compared to current smoking. The findings provide strong evidence for the recommendation of quitting smoking among diabetic patients.

Keywords: smoking, diabetes mellitus, meta-analysis, follow-up study, epidemiology

INTRODUCTION

Diabetes has become a global public health crisis, and the International Diabetes Federation estimated that 387 million adults were affected by diabetes in 2014 worldwide, and the number was predicted to continue to rise at an alarming rate and reach 592 million by 2035.1 Furthermore, people with diabetes have an increased risk of developing a number of serious health problems, including macrovascular (cardiovascular disease, CVD) and microvascular (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy) complications.2 It has also been widely acknowledged that smoking is a leading risk factor for diabetes,3,4 CVD,4 and total mortality4 in the general population. Smoking cessation is a major target for diabetes treatment;2 however, many patients continue to smoke even after diagnosis of diabetes,5 and the success rate of smoking cessation interventions among diabetic patients is not high with some studies reporting to be around 20%.6 Therefore, evaluation of the additional hazards associated with active smoking and potential benefits of smoking cessation among diabetic patients will provide direct evidence for the clinical practice and behavior changes.

Numerous studies have assessed the association between smoking and subsequent risks of mortality and morbidity, but the effect estimates varied substantially across studies.7 A previous meta-analysis included 46 studies published before 2011 that focused on total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes, and suggested that smoking was a modifiable risk factor for adverse outcomes among diabetic patients.7 However, the meta-analysis omitted several important papers which were eligible. Since 2011, many more studies have been published, which allow more detailed analysis of the association in different populations and subgroups. Therefore, we conducted a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies to describe the association between smoking and risk of total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes among diabetic patients.

METHODS

Data sources, search strategy, and eligibility criteria

We first searched the literature in April 2014 of MEDLINE and EMBASE for studies describing the association between cigarette smoking and any adverse outcomes among diabetic patients. To make sure our study was based on up-to-date results, we further updated the literature search of MEDLINE on May 3, 2015. In addition, we searched the reference lists of all identified relevant publications, and relevant reviews.6,7 Only papers published in English language were considered. The search focused on three themes of Medical Subject Headings terms and related exploded versions: smoking or cigarette, diabetes mellitus or glucose metabolism irregularity, and studies with a prospective design. The three themes were combined using the Boolean operator “and.” The detailed search strategies are shown in the Supplemental Material.

Study selection

Two investigators (Y.W. and M.T.) independently assessed literature eligibility; discrepancies were resolved by consensus, or by consulting with the third investigator (A.P.). Articles were considered for inclusion in the systematic review if: (1) the authors reported data from an original, peer-reviewed study (i.e., not review articles, or meeting abstracts); (2) the study was a cohort study consisting of non-institutionalized adults (>18 years old) with diabetes (including type 1 or type 2 diabetes); and (3) the authors reported risk estimates of total mortality or cardiovascular outcomes in diabetes participants by baseline smoking status. We included different comparisons by smoking status (comparing current with never smokers, current with non-current smokers, former with never smokers, and ever with never smokers). Given the large number of included studies and to reduce the influence from studies of limited statistical power, we decided to exclude studies with total sample size of less than 100 participants, or less than 50 total disease outcomes. Studies reporting crude associations without any adjustment were also excluded. A sensitivity analysis of including those studies in the meta-analysis did not materially alter the results (data not shown). In the case of multiple publications, we included the articles with the longest follow-up years or the largest number of incident cases. We identified articles eligible for further review by performing an initial screen of identified titles or abstracts, followed by a full-text review.

Data extraction

We extracted the following information about the studies: study characteristics (study name, authors, publication year, journal, study location, follow-up years, and number of participants), participants’ characteristics (mean age or age range, sex, ethnicity), smoking status (never, past and current), disease outcomes (assessed by self-reports, death certificates, medical records or clinical examinations), and analysis strategy (statistical models, covariates included in the models). If the information was unavailable or not clear from a published report, we collected relevant data by corresponding with the authors. Quality assessment was performed with consideration of the following aspects:8 validity of outcome measurements, exclusion of outcome at baseline, selection of non-exposure group, follow-up years, confounding adjustment, and generalizability to other populations. Smoking status was self-reported in all the studies, and most studies did not report information of response rate and follow-up rate.

Data synthesis and analysis

The relative risk (RR) was used as the common measure of association across studies, and the hazard ratio (HR) or rate ratio was considered equivalent to RR,9 while the odds ratio (OR) was converted to RR by the formula RR=OR/[(1−Po)+(Po×OR)], in which Po is the incidence of the outcome of interest in the nonexposed group.10 Forest plots were produced to visually assess the RRs and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) across studies. Heterogeneity across studies was evaluated by the Cochrane Q statistic (significance level of p <0.10) and the I2 statistic (ranges from 0% to 100% with lower values representing less heterogeneity).11 The RRs were pooled using the DerSimonian and Laird12 inverse-variance-weighted random-effects models. The possibility of publication bias was evaluated using the Egger’s test and visual inspection of a funnel plot.13 The Duval and Tweedie14 nonparametric trim-and-fill method was used to further assess the possible effect of publication bias. Moreover, stratified analyses and sensitivity analyses were performed to evaluate the influences of selected study and participant characteristics on the results. Finally, we omitted one study at each time to test the robustness of the results and the influence of individual study on the heterogeneity. The analyses were performed with Stata version 11.2 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

We calculated absolute risk differences associated with smoking by multiplying the background incidence rate of disease outcomes in diabetic populations with estimated (RR−1). Population attributable fraction (PAF) was calculated based on the following equation: PAF=100%×Pe(RR−1)/(Pe[RR−1]+1), where Pe is the prevalence of the smoking in the population and RR was derived from this meta-analysis.

RESULTS

Literature search

The search strategy identified 12,598 unique citations. After the first round screening based on titles and abstracts with the aforementioned criteria, 1,066 articles remained for further evaluation. After detailed examination, 996 articles were excluded for reasons shown in Figure 1. Another 15 studies were retrieved from the reference lists of relevant articles and reviews, and 4 studies were from the full publications of meeting abstracts (see Supplemental Material). In total, 89 articles were included, and the full list of the publications is shown in the Supplemental Material.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the Meta-analysis.

Among these 89 articles, 48 studies specifically reported results on total mortality, 13 studies on cardiovascular mortality, 16 studies on total CVD, 21 studies on coronary heart disease (CHD), 15 studies on stroke, 3 studies on peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and 4 studies on heart failure (HF). Some studies reported multiple outcomes. The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2.

Smoking and risk of mortality among diabetic patients

Characteristics of the studies reporting smoking and all-cause mortality are shown in Supplemental Table 1. One study15 reported results separately for type 1 diabetes (T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D), and one study16 reported results separately for those with and without baseline CVD, and thus 50 reports from 48 studies were included with a total of 1,132,700 participants and 109,966 deaths. Of the 48 studies, most were conducted in European countries (n=24) and US (n=14). Most studies were performed in T2D patients, while five studies were in T1D patients, and four studies in both types. Most studies included both men and women, while three studies were conducted exclusively in men and one in women. The prevalence of current smoking and the follow-up years varied across studies.

The majority of studies reported a positive association (i.e., RR >1.00), only two studies reported RR <1.00 but not statistically significant. A high heterogeneity was detected (I2=77.6%; P <0.001), and the RR (95% CI) from random-effects model was 1.55 (1.46–1.64; Figure 2). A sensitivity analysis of omitting one study in each turn showed no substantial change on the results with pooled RR ranging from 1.53 to 1.57 (data not shown). The RR (95% CI) remained significant in T1D patients (1.77; 1.52–2.07; 6 reports) and T2D patients (1.53; 1.44–1.63; 41 reports), as well as many subgroups (Supplemental Table 3). The results were similar when comparing current smoking with never (RR=1.62) or non-current (RR=1.53) smoking, or comparing ever with never smoking (RR=1.51; Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, 13 studies reported results for former compared with never smoking, and the pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.19 (1.11–1.28; Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 2.

Adjusted Relative Risks of Smoking with Total Mortality among Diabetic Participants. The summary estimates were obtained using a random-effects model. The data markers indicate the adjusted relative risks (RRs) comparing smoking to no smoking. The size of the data markers indicates the weight of the study, which is the inverse variance of the effect estimate. The diamond data markers indicate the pooled RRs. CI indicates confidence interval.

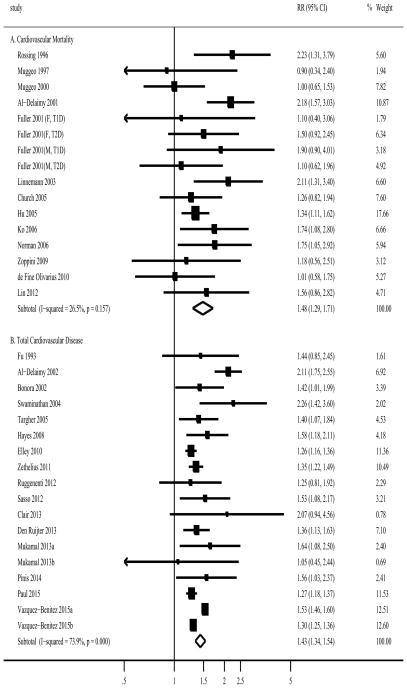

For cardiovascular mortality, one study17 reported results separately for types of diabetes and sex, thus a total of 16 reports from 13 studies were combined with 37,550 participants and 3,163 CVD deaths (Supplemental Table 1). Most studies were conducted in both sexes (n=11), and in European countries (n=7). The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.49 (1.29–1.71; I2=26.5%; P for heterogeneity=0.16; Figure 3). The association remained significant in studies among T1D patients (1.91; 1.29–2.85; 3 reports) and T2D patients (1.44; 1.24–1.68; 13 reports), and many subgroups (Supplemental Table 3). Furthermore, 8 studies reported results for former compared with never smoking, and the pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.15 (1.00–1.32; Supplemental Table 3).

Figure 3.

Adjusted Relative Risks of Smoking with (A) Cardiovascular Mortality and (B) Total Cardiovascular Disease among Diabetic Participants. The summary estimates were obtained using a random-effects model. The data markers indicate the adjusted relative risks (RRs) comparing smoking to no smoking. The size of the data markers indicates the weight of the study, which is the inverse variance of the effect estimate. The diamond data markers indicate the pooled RRs. CI indicates confidence interval.

Smoking and risk of cardiovascular events among diabetic patients

Characteristics of the studies reporting smoking and cardiovascular outcomes are shown in Supplemental Table 2. For CVD risk, 18 reports from 16 studies were found with 1,028,982 participants and 94,929 outcomes (one study18 did not report number of CVD cases). Most studies were conducted in European countries (n=8), and the others were from US (n=4), Australia and New Zealand (n=2), China (n=1) and International collaboration (n=1). All studies were conducted in T2D patients except one in T1D patients. The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.44 (1.34–1.54; I2=73.9%; P for heterogeneity <0.001; Figure 4). A sensitivity analysis of omitting one study in each turn showed no substantial change on the results with pooled RR ranging from 1.39 to 1.47 (data not shown).

Figure 4.

Adjusted Relative Risks of Smoking with (A) Coronary Heart Disease and (B) Stroke among Diabetic Participants. The summary estimates were obtained using a random-effects model. The data markers indicate the adjusted relative risks (RRs) comparing smoking to no smoking. The size of the data markers indicates the weight of the study, which is the inverse variance of the effect estimate. The diamond data markers indicate the pooled RRs. CI indicates confidence interval.

For CHD risk, 26 reports from 21 studies were found with 1,009,457 participants and 38,752 outcomes (Supplemental Table 2). Again, most studies were conducted in US (n = 9) and European countries (n=8), and the others were in New Zealand (n=1), China (n=1), Japan (n=1) and International collaboration (n=1). Seventeen studies were done in T2D patients, three in T1D patients and one in both types. The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.51 (1.41–1.62; I2=60.8%; P for heterogeneity <0.001; Figure 4). A sensitivity analysis of omitting one study in each turn showed no substantial change on the results with pooled RR ranging from 1.49 to 1.55 (data not shown). There were 3 studies reported results for CHD mortality,19–21 and the pooled RR was 2.01 (1.39–2.91; I2=0%; data not shown).

For stroke risk, 20 reports from 15 studies were found with 1,013,724 participants and 33,170 outcomes (one study18 did not report number of stroke cases; Supplemental Table 2). Again, most studies were conducted in European countries (n=8) and US (n=4), and the others were in China (n=1) and International collaboration (n=2). All studies were done in T2D patients except one study in both types. The pooled RR (95% CI) was 1.54 (1.41–1.69; I2=70.9%; P for heterogeneity <0.001; Figure 4). A sensitivity analysis of omitting one study in each turn showed no substantial change on the results with pooled RR ranging from 1.47 to 1.62 (data not shown).

The significant relations of smoking with CVD, CHD and stroke among diabetic patients were observed in most subgroups (Supplemental Table 4). Compared to never smoking, former smoking was associated with a moderately elevated risk of CVD (RR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.05–1.13; 7 reports) and CHD (1.14; 1.00–1.30; 13 reports), but not significant for stroke (1.04; 0.87–1.23; 9 reports).

As for other cardiovascular outcomes, we also found significant relations of smoking with PAD (RR 2.15; 95% CI 1.63–2.85; I2=33.6%; P for heterogeneity =0.22; 3 reports), and HF (RR 1.43; 95% CI 1.19–1.72; I2=93.8%; P for heterogeneity <0.001; 5 reports), and all the associations in individual studies were significant (Supplemental Figure 1).

Analysis of publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plot revealed moderate asymmetry for total mortality (Supplemental Figure 2A), and the Egger’s test was not significant (P=0.11). A sensitivity analysis using the trim-and-fill method was performed with 14 additional imputed studies, which produced a symmetrical funnel plot (Supplemental Figure 2B), and a pooled RR (95% CI) of 1.45 (1.38–1.53; Supplemental Table 4). No significant publication bias was observed for other outcomes: CVD mortality (P=0.91), CVD (P=0.33), CHD (P=0.38), and a moderate bias for stroke (P=0.045; RR, 1.40 after trim-and-fill method; 95% CI, 1.26–1.54; Supplemental Table 4).

Absolute risk difference and population attributable fraction

Using the data from the WHO Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetes,17 we estimated that the absolute risk difference associated with smoking for total mortality was 117 for T2D and 286 for T1D per 10,000 patients per year worldwide. According to the global prevalence of daily smoking from a recent publication (assuming that the smoking prevalence was similar between diabetic patients and the general population),22 and using the risk estimates from our meta-analysis and global estimates of deaths from diabetes,1 we estimated that 14.6% of total deaths in men and 3.3% in women (about 438,000 deaths annually) were attributable to active smoking among diabetic patients worldwide. The corresponding PAFs for other outcomes (CVD mortality, total CVD, CHD, and stroke) ranged from 12.0% to 14.4% in men, and 2.7% to 3.3% in women (Supplemental Table 5). The PAF calculations should vary in diabetic populations with different smoking prevalence and risk estimates for disease outcomes, and we used the populations in the United States (US), United Kingdom (UK), and China as examples in the Supplemental Table 5. For example, the PAFs were much higher in Chinese men while substantially lower in Chinese women. The PAFs were similar in men and women among US and UK populations where smoking was prevalent in both genders.

DISCUSSION

Using data from 89 prospective studies, our meta-analysis demonstrates that active smoking is prospectively associated with around 50% increased risk of total mortality and cardiovascular events. Furthermore, the associations persisted across most subgroups stratified by various study and participant characteristics. In addition, although the former smokers still had higher risks of total mortality and cardiovascular disease compared to never smokers, the increased risks were much lower compared to that in current smokers, suggesting the substantial benefits of smoking cessation among diabetic patients.

Our results are consistent with a previous meta-analysis of 46 studies published before 2011 regarding total mortality and cardiovascular outcomes.7 However, that meta-analysis missed many important papers. In particular, they had missed 6 eligible studies23–28 in the analysis of total mortality that were published before 2011. Our current meta-analysis included those studies together with many newly published articles (particularly some recent large studies16,29,30), thus providing the most accurate and comprehensive estimates of smoking related adverse health outcomes among diabetic patients. We included almost double the number of studies, and ten-fold more study participants. For example, our meta-analysis of total mortality included 48 studies with 1,132,700 participants and 109,966 deaths, while Qin et al’s paper7 only included 27 studies with 100,089 participants and 13,046 deaths. Finally, we also summarized the results for PAD and HF in our meta-analysis.

Given the consistency of the results for various outcomes in populations with different characteristics, our findings provide strong evidence that smoking is associated with adverse health consequences among diabetic patients. Similar to studies in the general population that have indicated a causal link between smoking and various disease outcomes (diabetes, CVD, and mortality),4 the observed associations among diabetic patients are likely to be causal as well. We observed the positive associations in most subgroups for various outcomes. Although the point estimates may vary in different subgroups, the 95% CIs largely overlapped and the meta-regression analyses did not reveal significant differences between groups. The number of studies in some subgroups was small thus making the risk estimates unstable. For example, studies in T1D patients and Asian populations are still limited. Furthermore, fewer studies are available for the dose-response analysis, and analysis of other cardiovascular events, like heart failure.

Smoking remains to be a major public health threat globally despite large reductions in the prevalence over the past several decades.22 Among diabetic patients, the prevalence of current smoking varied substantially in different studies as shown in our meta-analysis (Supplemental Tables 1–2). A previous study in US representative samples found that nearly one-fifth of diabetic patients were still current smokers.5 Furthermore, the prevalence of current smoking among young adults (18–39 years) with diabetes was even higher compared to non-diabetic individuals (37.0% vs. 30.4%).5 Therefore, smoking cessation remains a major treatment target for diabetic patients.2 There might be a potential concern for diabetic patients who motivated to quit smoking because smoking cessation can result in short-term weight gain,31 deterioration in glycemic control,32 and worsening of some diabetic symptoms.6 However, our current meta-analysis clearly showed that former smokers had relatively lower risk estimates compared to current smokers. Several studies have consistently reported attenuated risks with longer duration of smoking cessation,18,23,33 which are consistent with the findings in general populations regarding the long-term benefits of smoking cessation on health outcomes.34,35 Furthermore, studies in the Framingham Offspring Study36 and the Women’s Health Initiative37 showed that the recent smoking quitters had similar incidence rates of CVD/CHD events compared to the never smokers, and weight gain did not modify the association. Therefore, the current evidence supports a net cardiovascular benefit of smoking cessation among diabetic patients, despite significant short-term weight gain associated with smoking cessation.

We estimated that 14.6% of total deaths in men and 3.3% in women were attributable to smoking among diabetic patients worldwide. These numbers might be underestimated for several reasons. First, we used the age-standardized prevalence of daily smoking in adults above 15 years old,22 but the prevalence could be higher in middle-aged population22 when diabetes is diagnosed. Second, we used the daily smoking prevalence,22 and the PAFs would be higher if we used the current smoking prevalence from the WHO database.38 Nevertheless, our findings confirm that smoking is still a leading avoidable cause of morbidity and mortality among diabetic patients, particularly in men. Our results are also comparable to the recent WHO report,39 where globally 16% of deaths in men and 7% in women were attributable to smoking in the general population. Our point estimates of the increased risks of mortality and CVD associated with smoking among diabetic patients are slightly lower compared to that in the general population.4 Given the much higher mortality and morbidity rate in diabetic patients compared to the general population, the absolute numbers of excess mortality and morbidity cases due to smoking are considerable.

Several limitations of this meta-analysis should be acknowledged. First, we found a significant heterogeneity across studies for some outcomes, which may result from differences in study designs, sample sizes, analysis strategies, and participants’ characteristics. Although moderate to high heterogeneities still remained in many subgroups, the pooled RRs showed consistent positive associations in most subgroups. Second, the funnel plot indicated a possible publication bias for total mortality and total CVD; however, the trim-and-fill sensitivity analysis did not materially change the results, and the asymmetry of a funnel plot does not necessarily imply publication bias.40 Third, the meta-analysis was limited to English publications, and the possibility of unpublished reports was not yet identified. The literature screening and data extraction were conducted independently by two investigators, and thus, selection bias was unlikely. Fourth, the definition of smoking varied across studies, but our analysis found similar results of different comparison groups (i.e., current with never smoking, ever with never smoking, and current with non-current smoking) for all health outcomes. In addition, the associations were presented in different forms (OR, HR, RR etc.), and RR was used as the common measure of association in this meta-analysis. The summary results might be influenced by the conversion of other measures to RR, but such influence, if any, is likely to be small because only a few studies reported ORs. Moreover, despite strong associations, residual confounding is still possible given that many studies did not adjust for lifestyle factors in their models. Smoking is commonly related to other unhealthy lifestyle factors (e.g., unhealthy diet, excessive alcohol use, and physical inactivity)41,42 and depression and stress,43,44 which are also risk factors for poor health outcomes in diabetic patients. Finally, more studies are needed to determine the magnitude of the associations in certain populations such as Asians and T1D patients.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, this meta-analysis provides compelling evidence that smoking is a significant modifiable factor for adverse health consequences in diabetic patients. Given the increasing prevalence of diabetes and remaining high prevalence of smoking in many countries, the observed associations between smoking and disease outcomes among diabetic patients have significant clinical and public health importance. Our study supports the routine and thorough assessment of tobacco use in diabetic patients, and inclusion of the prevention and cessation of tobacco use as an important component of clinical diabetes care. More studies are needed to examine the efficacy and effectiveness of smoking cessation interventions to reduce the burden of excess morbidity and mortality associated with smoking among diabetic patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the following study investigators for providing unpublished data: Dr. Juhua Luo, PhD, from the School of Public Health, Indiana University, Indiana, USA; Drs. Lars Hung-Yuan Li, MD, PhD, Lee-Ming Chuang, MD, PhD, Tse-Ya Yu, MD, from the National Taiwan University Hospital, Taiwan, China; Dr. Carole Clair, MD, MSc, from the University of Lausanne, Switzerland; Dr. Graham A. Hitman, MD, from the Royal London Hospital, UK; Dr. Karin Nelson, MD, from the University of Washington, Washington, USA; and Dr. Philippos Orfanos, PhD, from the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Ciudad Universitaria, Spain. We also thank the following study investigators for clarifying inquiry of their papers: Dr. Toru Aizawa, MD, PhD, from the Shinshu University, Matsumoto, Japan; Dr. Shiro Tanaka, PhD, from the Kyoto University Hospital, Kyoto, Japan; Dr. Jiaqiong (Susan) Xu, PhD, from The Methodist Hospital Research Institute, Texas, USA; Dr. Simona Bo, MD, from the University of Torino, Italy; Dr. Esther Gerrits, MD, PhD, from the Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, The Netherlands; Dr. Gaston Perman, MD, MSc, from the Hospital Italiano de Buenos Aires, Argentina; Dr. Giuseppe Remuzzi, MD, from the Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo and Mario Negri Institute for Pharmacological Research, Bergamo, Italy. None of them were compensated.

Funding Sources: The project was supported by NIH grants HL034594 and DK058845. The funding sources did not involve in the data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing and publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.International Diabetes Federation. [Accessed February 7, 2015];IDF Diabetes Atlas: Sixth Edition. http://www.idf.org/diabetesatlas/update-2014.

- 2.American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes-2015: summary of revisions. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:S4. doi: 10.2337/dc15-S003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Willi C, Bodenmann P, Ghali WA, Faris PD, Cornuz J. Active smoking and the risk of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2007;298:2654–64. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.22.2654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed February 7, 2015];The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A report of the Surgeon General. http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/reports/50-years-of-progress.

- 5.Resnick HE, Foster GL, Bardsley J, Ratner RE. Achievement of American Diabetes Association clinical practice recommendations among U.S. adults with diabetes, 1999–2002: the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Diabetes Care. 2006;29:531–7. doi: 10.2337/diacare.29.03.06.dc05-1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tonstad S. Cigarette smoking, smoking cessation, and diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2009;85:4–13. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2009.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qin R, Chen T, Lou Q, Yu D. Excess risk of mortality and cardiovascular events associated with smoking among patients with diabetes: meta-analysis of observational prospective studies. Int J Cardiol. 2013;167:342–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2011.12.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wells GA, Shea B, O’Connell D, Peterson J, Welch V, Losos M, Tugwell P. [Accessed October 19, 2014];The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality if nonrandomized studies in meta-analyses. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp.

- 9.Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration; 2011. [Accessed July 25, 2015]. updated March 2011. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang J, Yu KF. What’s the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–60. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klein R, Moss SE, Klein BE, DeMets DL. Relation of ocular and systemic factors to survival in diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149:266–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vazquez-Benitez G, Desai JR, Xu S, Goodrich GK, Schroeder EB, Nichols GA, Segal J, Butler MG, Karter AJ, Steiner JF, Newton KM, Morales LS, Pathak RD, Thomas A, Reynolds K, Kirchner HL, Waitzfelder B, Elston Lafata J, Adibhatla R, Xu Z, O’Connor PJ. Preventable major cardiovascular events associated with uncontrolled glucose, blood pressure, and lipids and active smoking in adults with diabetes with and without cardiovascular disease: a contemporary analysis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:905–12. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fuller JH, Stevens LK, Wang SL. Risk factors for cardiovascular mortality and morbidity: The WHO multinational study of vascular disease in diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44:S54–S64. doi: 10.1007/pl00002940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Al-Delaimy WK, Manson JE, Solomon CG, Kawachi I, Stampfer MJ, Willett WC, Hu FB. Smoking and risk of coronary heart disease among women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:273–9. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford ES, DeStefano F. Risk factors for mortality from all causes and from coronary heart disease among persons with diabetes. Findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey I Epidemiologic Follow-up Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;133:1220–30. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adlerberth AM, Rosengren A, Wilhelmsen L. Diabetes and long-term risk of mortality from coronary and other causes in middle-aged Swedish men. A general population study. Diabetes Care. 1998;21:539–45. doi: 10.2337/diacare.21.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Florkowski CM, Scott RS, Coope PA, Moir CL. Predictors of mortality from type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canterbury, New Zealand; a ten-year cohort study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2001;53:113–20. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8227(01)00246-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ng M, Freeman MK, Fleming TD, Robinson M, Dwyer-Lindgren L, Thomson B, Wollum A, Sanman E, Wulf S, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Gakidou E. Smoking prevalence and cigarette consumption in 187 countries, 1980–2012. JAMA. 2014;311:183–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.284692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chaturvedi N, Stevens L, Fuller JH. Which features of smoking determine mortality risk in former cigarette smokers with diabetes? The World Health Organization Multinational Study Group. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:1266–72. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.8.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Church TS, Cheng YJ, Earnest CP, Barlow CE, Gibbons LW, Priest EL, Blair SN. Exercise capacity and body composition as predictors of mortality among men with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:83–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saremi A, Nelson RG, Tulloch-Reid M, Hanson RL, Sievers ML, Taylor GW, Shlossman M, Bennett PH, Genco R, Knowler WC. Periodontal disease and mortality in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:27–32. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McAuley PA, Myers JN, Abella JP, Tan SY, Froelicher VF. Exercise capacity and body mass as predictors of mortality among male veterans with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1539–43. doi: 10.2337/dc06-2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng CH, Chong CK, Tseng CP, Cheng JC, Wong MK, Tai TY. Mortality, causes of death and associated risk factors in a cohort of diabetic patients after lower-extremity amputation: a 6.5-year follow-up study in Taiwan. Atherosclerosis. 2008;197:111–7. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wells BJ, Jain A, Arrigain S, Yu C, Rosenkrans WA, Rattan MW. Predicting 6-year mortality risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2301–6. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly PJ, Clarke PM, Hayes AJ, Gerdtham UG, Cederholm J, Nilsson P, Eliasson B, Gudbjornsdottir S. Predicting mortality in people with Type 2 diabetes mellitus after major complications: a study using Swedish National Diabetes Register data. Diabetes Med. 2014;31:954–62. doi: 10.1111/dme.12468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Paul SK, Klein K, Majeed A, Khunti K. Association of smoking and concomitant use of metformin with cardiovascular events and mortality in people newly diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes. 2015 Apr 30; doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12302. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Aubin HJ, Farley A, Lycett D, Lahmek P, Aveyard P. Weight gain in smokers after quitting cigarettes: meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;345:e4439. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e4439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lycett D, Nichols L, Ryan R, Farley A, Roalfe A, Mohammed MA, Szatkowski L, Coleman T, Morris R, Farmer A, Aveyard P. The association between smoking cessation and glycaemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes: a THIN database cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3:423–30. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(15)00082-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Al-Delaimy WK, Willett WC, Manson JE, Speizer FE, Hu FB. Smoking and mortality among women with type 2 diabetes: the Nurses’ Health Study cohort. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:2043–8. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.12.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirie K, Peto R, Reeves GK, Green J, Beral V. The 21st century hazards of smoking and benefits of stopping: a prospective study of one million women in the UK. Lancet. 2013;381:133–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61720-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jha P, Ramasundarahettige C, Landsman V, Rostron B, Thun M, Anderson RN, McAfee T, Peto R. 21st-century hazards of smoking and benefits of cessation in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:341–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1211128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clair C, Rigotti NA, Porneala B, Fox CS, D’Agostino RB, Pencina MJ, Meigs JB. Association of smoking cessation and weight change with cardiovascular disease among adults with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2013;309:1014–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Luo J, Rossouw J, Margolis KL. Smoking cessation, weight change, and coronary heart disease among postmenopausal women with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2013;310:94–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.6871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.World Health Organization. [Accessed February 7, 2015];WHO report on the global tobacco epidemic. 2013 http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_report/2013/en/

- 39.World Health Organization. [Accessed February 7, 2015];WHO global report: mortality attributable to tobacco. http://www.who.int/tobacco/publications/surveillance/rep_mortality_attributable/en/

- 40.Sterne JA, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Jones DR, Lau J, Carpenter J, Rücker G, Harbord RM, Schmid CH, Tetzlaff J, Deeks JJ, Peters J, Macaskill P, Schwarzer G, Duval S, Altman DG, Moher D, Higgins JP. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d4002. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Strine TW, Okoro CA, Chapman DP, Balluz LS, Ford ES, Ajani UA, Mokdad AH. Health-related quality of life and health risk behaviors among smokers. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28:182–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiolero A, Wietlisbach V, Ruffieux C, Paccaud F, Cornuz J. Clustering of risk behaviors with cigarette consumption: a population-based survey. Prev Med. 2006;42:348–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Strine TW, Mokdad AH, Balluz LS, Gonzalez O, Crider R, Berry JT, Kroenke K. Depression and anxiety in the United States: findings from the 2006 Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59:1383–90. doi: 10.1176/ps.2008.59.12.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collins MM, Corcoran P, Perry IJ. Anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26:153–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2008.02648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.