Abstract

Background

A statistical model based on four kallikrein markers (total prostate-specific antigen [tPSA], free PSA [fPSA], intact PSA, and human kallikrein-related peptidase 2) in blood can predict risk of Gleason score ≥7 (high-grade) cancer at prostate biopsy.

Objective

To determine the value of this model in predicting high-grade cancer at biopsy in a community-based setting in which referral criteria included percentage of fPSA to tPSA (%fPSA).

Design, setting, and participants

We evaluated the model, with or without adding blood levels of microseminoprotein-β (MSMB) in a cohort of 749 men referred for prostate biopsy due to elevated PSA (≥3 ng/ml), low %fPSA (<20%), or suspicious digital rectal examination at Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden.

Outcome measurements and statistical analysis

The kallikrein markers, with or without MSMB levels, measured in cryopreserved anticoagulated blood were combined with age in a published statistical model (Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment [ProtecT]) to predict high-grade cancer at biopsy. Predictive accuracy was compared with a base model.

Results and limitations

The %fPSA was low (median: 17; interquartile range: 13–22) in this cohort because this marker was used as a referral criterion. The ProtecT model improved discrimination over age and PSA for high-grade cancer (0.777 vs 0.719; p = 0.002). At one illustrative cut point, use of the panel would reduce the number of biopsies by 236 per 1000 and detect 195 of 208 (94%) but delay diagnosis of 13 of 208 high-grade cancers. MSMB levels in blood did not improve the accuracy of the panel (p = 0.2).

Conclusions

The kallikrein model is predictive of high-grade cancer if criteria for biopsy referral also include %fPSA, and it can reduce unnecessary biopsies without missing an undue number of tumors.

Patient summary

We evaluated a published model to predict biopsy outcome in men biopsied due to low percentage of free to total prostate-specific antigen. The model helps reduce unnecessary biopsies without missing an undue number of high-grade cancers.

Keywords: Prostate-specific antigen, Biopsy, Four-kallikrein panel, Prostate cancer

1. Introduction

In unscreened men aged 45–60 yr, the risk of metastasis and death from prostate cancer (PCa) is strongly associated with the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) concentration in the blood [1]. Data from large randomized trials in Europe show that PSA-based screening for PCa significantly reduces death from PCa among men not otherwise screened for this disease [2–4]. PSA is widely used for the early detection of PCa [5]. However, PSA has only moderate specificity, with only a minority of men with elevated PSA harboring high-grade PCa.

Previous studies showed that a statistical model based on a panel of four kallikrein markers (total PSA [tPSA], free PSA [fPSA], intact PSA, and human kallikrein-related peptidase 2 [hK2]) can predict the outcome of prostate biopsy in a variety of different settings including unscreened men, men with a prior PSA test, and those with a prior negative biopsy [6–11].

These studies involved cohorts from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) in which decisions to biopsy men were based on findings of an elevated PSA (≥3 ng/ml). In routine clinical practice, urologists often take into account percentage of fPSA to tPSA (%fPSA) before deciding to biopsy. Because fPSA is part of the kallikrein panel, it is plausible that the panel would lose its value if evaluated in this context. We evaluated the four-kallikrein panel in a large community-based referral cohort at Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, Sweden, in which referral criteria explicitly included low %fPSA.

As a secondary aim, we assessed whether another abundant secretory protein in the prostate suggested as an additional blood marker, microseminoprotein-β (MSMB) [12], would contribute additional discriminatory accuracy above and beyond that of the kallikrein-based model alone. The common single nucleotide polymorphism (rs10993994) in the 5′ region of the MSMB gene encoding β-microseminoprotein (MSP) is associated with both circulating levels of MSP in serum and with PCa risk [13,14]. MSP levels in serum were shown to be significantly lower in men with PCa and even lower in men with aggressive disease [15,16].

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Patient population

The study cohort included 749 men referred to Skåne University Hospital for prostate biopsy between 2004 and 2010. Decisions to perform prostate biopsies were based on tPSA levels in serum ≥3.0 ng/ml, %fPSA ≤20%, or a suspicious digital rectal examination (DRE). Patients underwent an eight-core prostate biopsy. All participants gave written informed consent at the time of recruitment, and the project was approved by the research ethics board at Lund University (research authorization number 367/2003). Histopathologic assessment of biopsies was undertaken by urologic pathologists blinded to marker levels using standardized protocols [17].

2.2. Immunoassay measurements of four kallikrein markers and MSMB

Ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid anticoagulated blood was collected by venipuncture, centrifuged at 3000 g for 10 min within 30–90 min of the blood draw, and frozen at −80°C as anticoagulated plasma to minimize the risk of biomarker degradation in the cryopreserved samples [18,19]. Immunoassay measurements for tPSA, fPSA [18], intact PSA, hK2 [20,21], and MSMB [22,23] were conducted on the AutoDelfia 1235 automatic immunoassay system in H.L.’s laboratory at the Wallenberg Research Laboratories, Department of Translational Medicine, Lund University, Skåne University Hospital, as reported previously [9,12].

The fPSA and tPSA were measured using the dual-label DELFIA Prostatus tPSA/fPSA assay (Perkin-Elmer, Turku, Finland) [18] calibrated against the World Health Organization (WHO) 96/670 (PSA-WHO) and WHO 68/668 (fPSA-WHO) standards. The measurements of intact PSA and hK2 were performed with F(ab′)2 fragments of the monoclonal capture antibodies, as previously reported [8]. The intact PSA assay measures only single-chain intact forms of fPSA (uncomplexed) because the monoclonal 4D4 immunoglobulin G used in this assay does not bind multichain forms of fPSA cleaved at Lys145 or Lys146 [24]. Production and purification of the polyclonal rabbit anti-MSMB antibody, protocols for biotinylation and Europium labeling of the anti-MSMB antibody, and performance of the MSMB immunoassay were carried out as previously reported [12,23]. All assay measurements were conducted blind to biopsy result.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Our primary aim was to validate the accuracy of the four-kallikrein model for predicting high-grade cancer on biopsy in a large referral cohort at Skåne University Hospital. The kallikrein model was built utilizing data from 4765 men enrolled in the prospective randomized trial Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment (ProtecT) [25]. In brief, the ProtecT study enrolled men aged 50–69 yr and invited them between 2001 and 2008 to receive PSA testing. Men with a PSA measurement ≥3.0 ng/ml were invited to undergo a 10-core prostate biopsy [26]. Although the primary aim was to assess the performance of the kallikrein markers to predict high-grade cancer (Gleason score ≥7) on biopsy, because these men will likely undergo immediate treatment, we repeated all analyses evaluating the performance of a model predicting any-grade cancer using the four-kallikrein markers and patient age. Models incorporating the DRE result (normal vs abnormal), patient age, and the four kallikrein markers were also assessed. The DRE result was not available in the ProtecT cohort at the time of the model development, and so the coefficient for DRE was taken from a separate model [7].

We began by comparing the performance of the kallikrein model with two base models consisting of tPSA and patient age and tPSA, patient age, and DRE. The base models were built on the Skåne University Hospital cohort using logistic regression. The tPSA was entered into the model using restricted cubic splines to account for any nonlinearity. The predictions from the resulting model were corrected for overfit using 10-fold cross validation. Separate models were created for predicting high-grade PCa and any-grade cancer on biopsy.

Analysis of area under the curve (AUC) was utilized to assess the ability of each model to discriminate between patients with and without evidence of high-grade cancer at biopsy. To compare the discrimination of the kallikrein model with the discrimination of the base model, the DeLong, DeLong, and Clarke-Pearson method was used [27]. Calibration plots were used to assess calibration.

To determine the clinical value of the four-kallikrein model in this cohort, we used decision curve analysis [28]. This method estimates a net benefit for prediction models by summing the benefits (true positives) and subtracting the harms (false positives). Because the harms of missing a true positive generally differ from those resulting from a false positive, the net benefit calculation weights true and false positives differently. The weighting is derived from the threshold probability of a disease at which a patient would opt for intervention, in this case the probability of high-grade cancer at which a patient would agree to a biopsy [10].

We also sought to investigate the marginal significance of MSMB when added to a model including the kallikrein panel. Specifically, we investigated the marginal significance of MSMB in logistic regression models predicting biopsy outcome with age, four kallikrein markers (included in the model as the prespecified algorithm), and MSMB as covariates. We also examine whether MSMB enhanced discrimination or AUC of the ProtecT model. Analyses were conducted using Stata v.12.0 (StataCorp., College Station, TX, USA).

3. Results

Of the 749 biopsied men, 293 (39%) had any-grade PCa on biopsy, and 156 (21%) had high-grade cancer (Gleason score ≥7). As expected, %fPSA was low (median: 17; interquartile range: 13–22) because this marker was used as a referral criterion. Further, men with cancer were slightly older and had higher rates of abnormal DRE and higher tPSA than men without evidence of cancer at biopsy (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Overall n = 749 (100%) |

No evidence of cancer at biopsy n = 456 (61%) |

Gleason score ≤6 PCa n = 137 (18%) |

Gleason score ≥7 PCa n = 156 (21%) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at biopsy, yr | 65 (60–70) | 64 (59–68) | 64 (60–69) | 68 (64–73) | <0.0001 |

| Total PSA | 6.3 (4.4–10.7) | 5.7 (4.2–8.7) | 6.0 (4.4–9.8) | 10.2 (5.6–20.3) | <0.0001 |

| Free-to-total PSA ratio |

0.17 (0.13–0.22) | 0.18 (0.14–0.23) | 0.17 (0.13–0.21) | 0.14 (0.10–0.18) | <0.0001 |

| Free PSA | 1.1 (0.8–1.8) | 1.1 (0.7–1.7) | 1.1 (0.8–1.7) | 1.4 (0.8–2.3) | 0.0005 |

| Intact PSA | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.5 (0.3–0.7) | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0.8 (0.4–1.2) | <0.0001 |

| hK2 | 0.06 (0.04–0.11) | 0.06 (0.04–0.09) | 0.08 (0.04–0.12) | 0.09 (0.06–0.19) | <0.0001 |

| Abnormal DRE | 246 (33) | 116 (25) | 39 (28) | 91 (58) | <0.0001 |

| Clinical T stage | |||||

| T1 | 98 (72) | 64 (41) | |||

| T2 | 34 (25) | 47 (30) | |||

| T3 | 5 (3.6) | 42 (27) | |||

| T4 | 0 (0) | 2 (1.3) | |||

| Unknown | 0 (0) | 1 (0.6) |

DRE = digital rectal examination; hK2 = human kallikrein-related peptidase 2; PCa = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

All values are median (interquartile range) or frequency (%).

The prespecified four-kallikrein model discriminated men with evidence of high-grade cancer at biopsy from those without high-grade cancer with an AUC of 0.777 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.736–0.819). This was significantly higher than the base model including age and PSA (AUC: 0.719 [95% CI, 0.672–0.767]; p = 0.002). Similar results were observed comparing the base model with PSA, age, and DRE with the four-kallikrein model including age and DRE (AUC increase 0.048 for high-grade disease; p = 0.001). However, DRE did not significantly improve the AUC of a model predicting high-grade cancer based on age and the four kallikrein markers (AUC increase: 0.007; p = 0.4). We found a similar increase in discrimination using the four-kallikrein model compared with the base model for predicting evidence of any-grade PCa at biopsy (Table 2).

Table 2.

Discrimination of total prostate-specific antigen

| High-grade cancer | Any-grade cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| Age and PSA* | 0.719 (0.672–0.767) | 0.632 (0.590–0.674) |

| Age, four-kallikrein panel | 0.777 (0.736–0.819) | 0.683 (0.644–0.722) |

| Age, PSA, DRE* | 0.736 (0.689–0.782) | 0.638 (0.597–0.679) |

| Age, four-kallikrein panel, and DRE | 0.784 (0.742–0.826) | 0.690 (0.652–0.729) |

AUC = area under the curve; DRE = digital rectal examination; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Data are shown as AUC (95% confidence interval). This risk model incorporates age and total PSA, a previously specified model using age and a panel of four kallikrein markers, and a second previously specified model using age, a panel of four kallikrein markers, and digital rectal examination.

AUC was corrected for overfit using 10-fold cross validation.

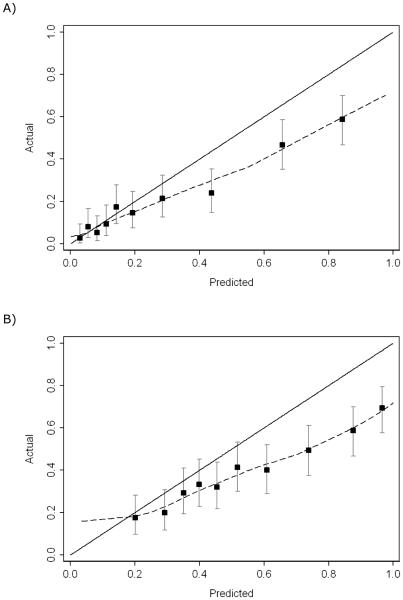

Figure 1 shows the calibration plots for high-grade cancer and overall positive biopsy. There is some overestimation of risk for the high-grade model, but this is only apparent at risks >20%. As such, it has little clinical relevance. For instance, high-grade disease was only found in about 40% of men with a predicted risk of 65%; however, biopsy would still be indicated irrespective of whether risk was 40% or 65%. The model predicting risk of any-grade cancer at biopsy is not well calibrated.

Fig. 1.

Calibration plot for the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment model predicts (a) high-grade cancer and (b) any-grade cancer using age, total prostate-specific antigen (PSA), free PSA, intact PSA, and human kallikrein-related peptidase 2 (dashed lines).

PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

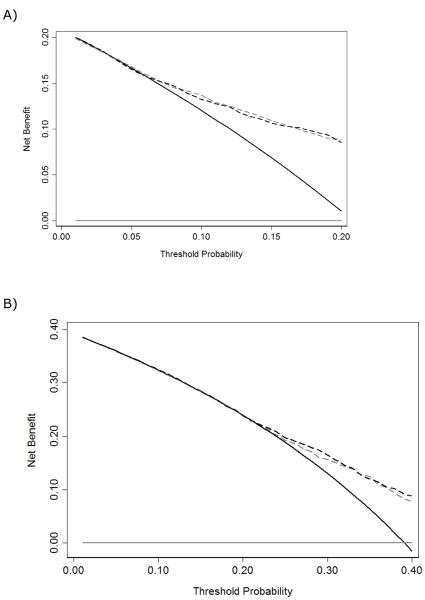

On decision curve analysis, the model predicting high-grade cancer suggests a net benefit above biopsy thresholds of 5% (Fig. 2). Conversely, the model predicting any-grade PCa did not exhibit a higher net benefit compared with a strategy of biopsying all men in this cohort, indicating a limited clinical value near a 20% biopsy threshold. These results suggest the high-grade kallikrein model is better suited for guiding decision making about prostate biopsy.

Fig. 2.

Decision curve analysis for the Prostate Testing for Cancer and Treatment model predicts (a) high-grade cancer and (b) any-grade cancer. The dashed gray line is the net benefit of the laboratory model (age and the kallikrein [KLK] panel); the dashed black line is the net benefit of the clinical model (age, digital rectal examination, and KLK panel). As a comparison, the net benefits from a biopsy-all strategy (solid black line) and a biopsy-none strategy (solid gray line) are shown.

DRE = digital rectal examination; KLK = kallikrein.

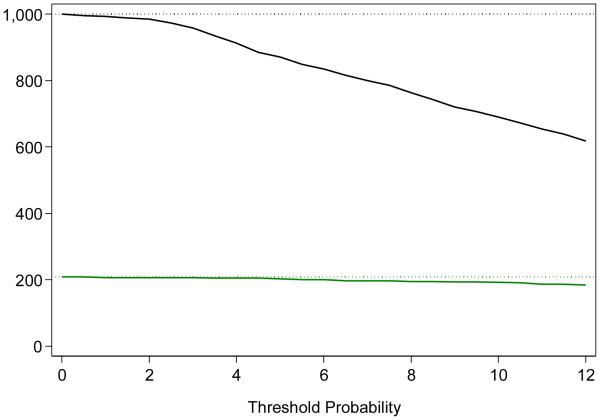

The use of the four-kallikrein model to identify men harboring high-grade cancer can reduce the number of men requiring biopsy. As an illustration, we imagined that a threshold of 8% risk of high-grade disease was used to determine biopsy. For every 1000 men who are clinically indicated for biopsy, 764 would undergo biopsy (a reduction of about 25%) based on the four-kallikrein panel; 195 of 208 (94%) high-grade cancers would be found, whereas diagnosis would be delayed for 13 high-grade cancers (60% 3 + 4, 20% 4 + 3, and 20% ≥8) (Table 3; Fig. 3). In this scenario, the initial indication for prostate biopsy would be based on DRE, PSA, and fPSA. If biopsy is believed to be indicated on the basis of those markers, the kallikrein panel would be used as a reflex test to determine which men should be subject to biopsy.

Table 3.

Results of differing biopsy strategies*

| Biopsies | Any-grade PCa | Gleason score ≥7 (high grade) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Performed | Avoided (%) | Found | Delayed | Found | Delayed | |

| Biopsy all men |

1000 | 0 (0) | 391 | 0 | 208 | 0 |

|

| ||||||

| Risk by age and total prostate-specific antigen | ||||||

| ≥4% | 997 | 3 (0.3) | 390 | 1 | 208 | 0 |

| ≥6% | 996 | 4 (0.4) | 390 | 1 | 208 | 0 |

| ≥8% | 948 | 52 (5.2) | 371 | 20 | 202 | 7 |

| ≥10% | 850 | 150 (15) | 351 | 40 | 191 | 17 |

| ≥12% | 746 | 254 (25) | 324 | 67 | 184 | 24 |

|

| ||||||

| Risk by age and panel of four kallikrein markers | ||||||

| ≥4% | 913 | 87 (8.7) | 375 | 16 | 206 | 3 |

| ≥6% | 834 | 166 (17) | 360 | 31 | 200 | 8 |

| ≥8% | 764 | 236 (24) | 344 | 47 | 195 | 13 |

| ≥10% | 690 | 310 (31) | 323 | 68 | 192 | 16 |

| ≥12% | 618 | 382 (38) | 303 | 88 | 184 | 24 |

PCa = prostate cancer; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Per 1000 men screened at varying thresholds for high-grade cancer.

Fig. 3.

Clinical implications of using a model developed to predict the risk of Gleason score ≥7 (high-grade) prostate cancer based on four kallikrein markers. The graph illustrates the results of using the model per 1000 men eligible for biopsy, with the x-axis denoting the threshold risk of high-grade cancer and the y-axis indicating the number of men biopsied (black line) or detected with evidence of high-grade cancer (green line).

Upon investigation of the marginal value in discrimination of each of the four kallikrein markers, we found that tPSA and fPSA increase the discrimination of the high-grade model far more than either intact PSA or hK2 (Table 4). The tPSA increased the discrimination by 0.149 and fPSA by 0.165. Together, intact PSA and hK2 increased the discrimination of the model by 0.073; that is, the full model has an AUC of 0.073 higher than a model with age, tPSA, and fPSA only.

Table 4.

Marginal discrimination of each of the four kallikrein markers

| Age and kallikreins | Age, kallikreins, and DRE | |

|---|---|---|

| High-grade cancer | ||

| Full model | 0.777 (0.736–0.819) | 0.784 (0.742–0.826) |

| Without total PSA | 0.628 (0.577–0.678) | 0.685 (0.637–0.733) |

| Without free PSA | 0.612 (0.562–0.662) | 0.628 (0.578–0.679) |

| Without intact PSA | 0.740 (0.695–0.785) | 0.759 (0.716–0.803) |

| Without hK2 | 0.770 (0.728–0.811) | 0.782 (0.741–0.823) |

| Without intact PSA nor hK2 |

0.704 (0.656–0.752) | 0.732 (0.686–0.778) |

| Any-grade cancer | ||

| Full model | 0.683 (0.644–0.722) | 0.690 (0.652–0.729) |

| Without total PSA | 0.572 (0.529–0.614) | 0.608 (0.567–0.650) |

| Without free PSA | 0.638 (0.597–0.679) | 0.647 (0.607–0.688) |

| Without intact PSA | 0.682 (0.643–0.722) | 0.690 (0.651–0.728) |

| Without hK2 | 0.649 (0.608–0.689) | 0.665 (0.625–0.705) |

| Without intact PSA nor hK2 |

0.648 (0.607–0.688) | 0.664 (0.624–0.704) |

DRE = digital rectal examination; hK2 = human kallikrein-related peptidase 2; PSA = prostate-specific antigen.

Data are shown as area under the curve (95% confidence interval).

Finally, we evaluated the diagnostic value of adding MSMB levels in blood to the prespecified statistical models based on age and the four kallikrein markers. MSMB was not significantly associated with high-grade disease after adjustment for age and the kallikrein markers (p = 0.2). MSMB was significantly associated with the detection of any-grade cancer on biopsy (p = 0.043); however, little improvement in diagnostic accuracy was found by adding MSMB in blood to these models (data not shown).

4. Discussion

We evaluated the diagnostic performance of a previously specified statistical model based on a panel of four kallikrein markers in a large community-based referral study at Skåne University Hospital. We found that the model had higher discrimination than a base model including PSA and age, plus or minus DRE. The model predicting risk of high-grade cancer at biopsy was well calibrated, with decision analysis demonstrating that use of the model in practice would improve biopsy-outcome predictions. Previous studies showed that men with low blood levels of MSMB have an increased risk of PCa [12]. However, we did not find any evidence of improved discrimination if we used MSMB as an additional marker.

Our findings replicate the original studies on the ERSPC [6,10,11], as well as two more recent studies [11,25,29]. Bryant et al reported an increase in AUC from 0.738 to 0.820 if fPSA, intact PSA, and hK2 were added to a base model containing tPSA and patient age to predict high-grade cancer in the ProtecT cohort [25]. In the current independent validation of the ProtecT data, we observed an improvement in discrimination that was attenuated compared with the ProtecT study. Moreover, the ProtecT model slightly overpredicted risk when applied to our cohort. Two differences between the current cohort and ProtecT may help explain each of these two inconsistencies. With respect to discrimination, biopsy in ProtecT was based solely on an elevated PSA (≥3 ng/ml), but referral for the current cohort was also based on fPSA:tPSA ratios (≤20%), an important component of the kallikrein model. A model that includes fPSA contains less additional information if fPSA is already used in biopsy decision making. With respect to miscalibration, the observed overprediction of risk when applying the ProtecT model to the current cohort may be related to the use of a more extended biopsy scheme in ProtecT.

Parekh et al [29] reported an AUC similar to that found in the ProtecT cohort (0.74–0.82), and there was no important miscalibration. The Parekh cohort is similar to our cohort because they both consist of men who are clinically indicated for biopsy; however, the use of %fPSA for biopsy decision making is far less frequent in a US population compared with a Swedish population [29]. As such, it is not unexpected that the increase in the AUC would be greater in the Parekh study than in our cohort.

Our study had several limitations. Patients were biopsied between 2004 and 2010 using an eight-core approach. This may help explain why there is some miscalibration compared with a model based on the ProtecT cohort that used a more contemporary biopsy scheme with a minimum of 10 cores [25].

Furthermore, the study cohort was ethnically homogeneous. Therefore, we cannot make inferences about the effects of race on the value of the kallikrein model. Family history data were not available, and so we could not evaluate family history as a marker. That said, it was previously reported that family history does not add to the prediction of high-grade disease, which is our primary outcome here [30].

5. Conclusions

In a large referral cohort of men biopsied due to modest tPSA elevation with a low %fPSA, a prespecified model based on four kallikrein markers in the blood contributed significant improvements in the predictive accuracy of biopsy outcome. This confirms that a model incorporating four kallikrein markers improves clinical decision making regarding whether or not to biopsy a patient who is otherwise indicated for biopsy. Furthermore, the kallikrein model improves decision making in addition to using fPSA:tPSA ratio as a biopsy indication in a clinical setting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gun-Britt Eriksson, Mona Hassan Al-Battat, and AnnaPeri Erlandsson for expert assistance with immunoassay measurements of the blood samples at the Wallenberg Research Laboratories at Lund University, Malmö, Sweden.

Funding/support and role of the sponsor: This work was supported in part by the National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health (R01 CA160816 to Hans Lilja and Andrew J. Vickers and P50 CA092629 and P30 CA008748 to Andrew J. Vickers); the Sidney Kimmel Center for Prostate and Urologic Cancers; David H. Koch through the Prostate Cancer Foundation to Andrew J. Vickers and Hans Lilja; the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre Program to Hans Lilja; Swedish Cancer Society (projects no. 11-0624 and 14-0722 to Hans Lilja 13-0479 and 14-0274 to Anders Bjartell); Swedish Scientific Council (projects no. K2011-67X-21861-01-6 and K2014-66X-20760-07-4 to Anders Bjartell) and Fundación Federico SA to Hans Lilja. The funding sources did not have any role in the design or conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of the data; or the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial disclosures: Hans Lilja certifies that all conflicts of interest, including specific financial interests and relationships and affiliations relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript (eg, employment/affiliation, grants or funding, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, royalties, or patents filed, received, or pending), are the following: Hans Lilja holds patents for free PSA, hK2, and intact PSA assays, and he is named, along with Andrew J. Vickers, on a patent application for a statistical method to detect PCa. The method has been commercialized by OPKO. Hans Lilja and Andrew J. Vickers will receive royalties from any sales of the test.

References

- [1].Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Bjork T, et al. Prostate specific antigen concentration at age 60 and death or metastasis from prostate cancer: case-control study. BMJ. 2010;341:c4521. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Screening and prostate cancer mortality: results of the European Randomised Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer (ERSPC) at 13 years of follow-up. Lancet. 2014;384:2027–35. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60525-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Schroder FH, Hugosson J, Roobol MJ, et al. Prostate-cancer mortality at 11 years of follow-up. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:981–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hugosson J, Carlsson S, Aus G, et al. Mortality results from the Goteborg randomised population-based prostate-cancer screening trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:725–32. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70146-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lilja H, Ulmert D, Vickers AJ. Prostate-specific antigen and prostate cancer: prediction, detection and monitoring. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:268–78. doi: 10.1038/nrc2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Benchikh A, Savage C, Cronin A, et al. A panel of kallikrein markers can predict outcome of prostate biopsy following clinical work-up: an independent validation study from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer screening, France. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:635. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Gupta A, Roobol MJ, Savage CJ, et al. A four-kallikrein panel for the prediction of repeat prostate biopsy: data from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer screening in Rotterdam, Netherlands. Br J Cancer. 2010;103:708–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Vaisanen V, Peltola MT, Lilja H, et al. Intact free prostate-specific antigen and free and total human glandular kallikrein 2. Elimination of assay interference by enzymatic digestion of antibodies to F(ab′)2 fragments. Anal Chem. 2006;78:7809–15. doi: 10.1021/ac061201+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Vickers A, Cronin A, Roobol M, et al. Reducing unnecessary biopsy during prostate cancer screening using a four-kallikrein panel: an independent replication. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:2493–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Aus G, et al. A panel of kallikrein markers can reduce unnecessary biopsy for prostate cancer: data from the European Randomized Study of Prostate Cancer Screening in Goteborg, Sweden. BMC Med. 2008;6:19. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-6-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Vickers AJ, Cronin AM, Roobol MJ, et al. A four-kallikrein panel predicts prostate cancer in men with recent screening: data from the European Randomized Study of Screening for Prostate Cancer, Rotterdam. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3232–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Haiman CA, Stram DO, Vickers AJ, et al. Levels of beta-microseminoprotein in blood and risk of prostate cancer in multiple populations. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013;105:237–43. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Eeles RA, Kote-Jarai Z, Giles GG, et al. Multiple newly identified loci associated with prostate cancer susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2008;40:316–21. doi: 10.1038/ng.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Thomas G, Jacobs KB, Yeager M, et al. Multiple loci identified in a genome-wide association study of prostate cancer. Nat Genet. 2008;40:310–5. doi: 10.1038/ng.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Nam RK, Reeves JR, Toi A, et al. A novel serum marker, total prostate secretory protein of 94 amino acids, improves prostate cancer detection and helps identify high grade cancers at diagnosis. J Urol. 2006;175:1291–7. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(05)00695-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reeves JR, Dulude H, Panchal C, et al. Prognostic value of prostate secretory protein of 94 amino acids and its binding protein after radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:6018–22. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Gleason DF. Histologic grading of prostate cancer: a perspective. Hum Pathol. 1992;23:273–9. doi: 10.1016/0046-8177(92)90108-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Mitrunen K, Pettersson K, Piironen T, et al. Dual-label one-step immunoassay for simultaneous measurement of free and total prostate-specific antigen concentrations and ratios in serum. Clin Chem. 1995;41:1115–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Ulmert D, Becker C, Nilsson JA, et al. Reproducibility and accuracy of measurements of free and total prostate-specific antigen in serum vs plasma after long-term storage at −20 degrees C. Clin Chem. 2006;52:235–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.050641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Nurmikko P, Pettersson K, Piironen T, et al. Discrimination of prostate cancer from benign disease by plasma measurement of intact, free prostate-specific antigen lacking an internal cleavage site at Lys145-Lys146. Clin Chem. 2001;47:1415–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Piironen T, Lovgren J, Karp M, et al. Immunofluorometric assay for sensitive and specific measurement of human prostatic glandular kallikrein (hK2) in serum. Clin Chem. 1996;42:1034–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Abrahamsson PA, Andersson C, Bjork T, et al. Radioimmunoassay of beta-microseminoprotein, a prostatic-secreted protein present in sera of both men and women. Clin Chem. 1989;35:1497–503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Valtonen-Andre C, Savblom C, Fernlund P, et al. Beta-microseminoprotein in serum correlates with the levels in seminal plasma of young, healthy males. J Androl. 2008;29:330–7. doi: 10.2164/jandrol.107.003616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nurmikko P, Vaisanen V, Piironen T, et al. Production and characterization of novel anti-prostate-specific antigen (PSA) monoclonal antibodies that do not detect internally cleaved Lys145-Lys146 inactive PSA. Clin Chem. 2000;46:1610–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bryant RJ, Sjoberg DD, Vickers AJ, et al. Predicting high-grade cancer at then-core prostate biopsy using four kallikrein markers measured in blood in the ProtecT study. J Natl Cancer Inst. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv095. In press. DOI:10.1093/jnci/djv095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Lane JA, Donovan JL, Davis M, et al. Active monitoring, radical prostatectomy, or radiotherapy for localised prostate cancer: study design and diagnostic and baseline results of the ProtecT randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2014;15:1109–18. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70361-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Vickers AJ, Elkin EB. Decision curve analysis: a novel method for evaluating prediction models. Med Decis Making. 2006;26:565–74. doi: 10.1177/0272989X06295361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Parekh DJ, Punnen S, Sjoberg DD, et al. A multi-institutional prospective trial in the USA confirms that the 4Kscore accurately identifies men with high-grade prostate cancer. Euro Urol. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.021. In press. DOI: 10.1016/j.eururo.2014.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Kaplan DJ, Boorjian SA, Ruth K, et al. Evaluation of the Prostate Cancer Prevention Trial Risk calculator in a high-risk screening population. BJU Int. 2010;105:334–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2009.08793.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]