Highlights

-

•

We hereby report a case which closely mimicked signs and symptoms of Subclavian Steal syndrome.

-

•

On further analysis, etiology was found to be due to congenital vascular malformations and atherosclerotic changes in the internal carotid artery.

-

•

We could not find similar reported cases in literature.

-

•

The figures are updated to clarify the clinical findings.

Keywords: Persistent trigeminal artery, Carotid atherosclerosis, Syncope attacks

Abstract

Introduction

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency (VBI) is a condition that results from restricted blood flow to the posterior portions of the brain, which are primarily served by the vertebral and basilar arteries. It is the most common cause of vertigo in the elderly and is usually accompanied by impaired vision and sensation. Congenital abnormalities, atherosclerosis, stroke and/or trauma may all lead to decreased vertebrobasilar circulation. A syndrome called Subclavian Steal Syndrome (SSS), which manifests with similar neurological symptoms but with a different pathophysiology, may also cause VBI.

Case presentation

A middle-aged female presented with gradual onset fainting and vertigo attacks. Cardiac, auditory and autonomic etiologies were investigated and excluded. Clinical findings and presentation were highly suggestive of subclavian steal. However, subsequent CT angiography showed normal subclavian arteries. Instead, findings included a persistent right trigeminal artery (PTA), stenosis of the right proximal internal carotid artery, atresis of the left vertebral artery and distal segment of right vertebral artery, congenitally compromised changes in vertebral circulation (bilateral absence of the posterior communicating arteries (PCOMs)) and an absent anterograde vertebrobasilar circulation. Symptoms resolved after carotid endarterectomy.

Discussion

Due to the absence of a normally developed posterior circulation, the PTA was the main source of blood supply for the patient. Development of recent artheromatous changes in the right internal carotid artery, however, resulted in decreased blood through PTA, further compromising posterior circulation. This resulted in vertebrobasilar insufficiency, and manifested in symptomology similar to SSS.

Conclusions

This clinical encounter illustrates the relative contribution of anatomical and vasoocclusive factors in closely mimicking symptoms of subclavian steal syndrome.

1. Introduction

Subclavian steal syndrome (SSS) is a relatively rare phenomenon that usually presents in patients 55 years or older, more frequently in Caucasians due to increased incidence of atherosclerosis. It has a 2:1 male to female ratio, and is characterized primarily by the occlusion of the subclavian artery proximal to the origin of the vertebral artery. Typical clinical findings of SSS are a difference of more than 20 mm Hg in blood pressure between two arms, unilaterally decreased pulses, supraclavicular bruits, and absence of radial pulse during exercise of affected extremity. Ultrasound, MRI or angiography confirms diagnosis. Surgical intervention is required for symptomatic patients after critical evaluation of complete hemodynamic situation, and aims at restoring antegrade vertebral artery flow, alleviating cerebral hypoperfusion and improvement of arterial perfusion in upper arm. In addition, aggressive management and modification of risk factors, namely control of hypertension, diabetes, hypocholesterolemia, and tobacco use, is essential in optimal treatment algorithm for this syndrome [1], [2].

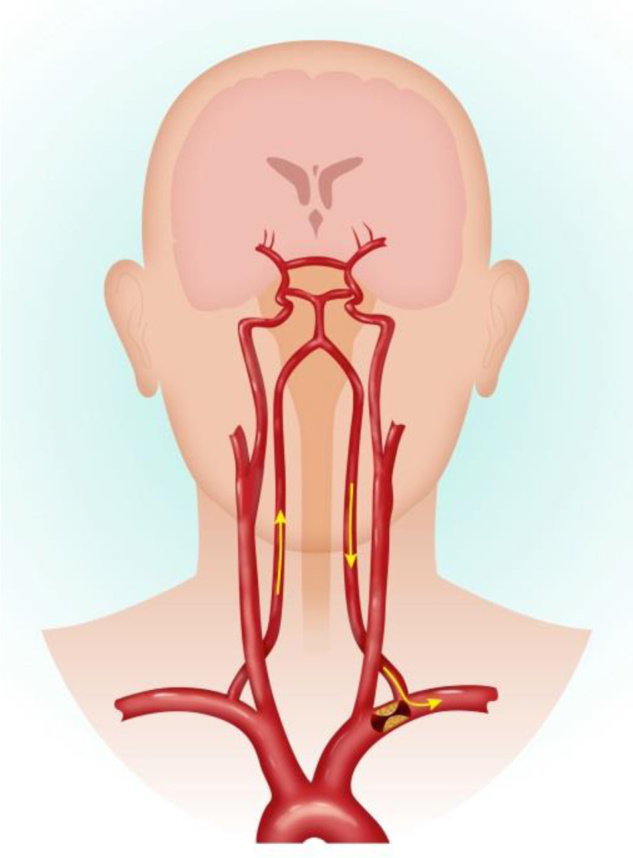

Underlying pathophysiology is a build up of a negative pressure gradient between the vertebral-basiliar and vertebral-subclavian artery junctions, resulting in altered vascular hemodynamics. Blood flows in the retrograde direction in the ipsilateral vertebral artery toward the upper arm, distal to stenosed subclavian artery, effectively stealing blood away from vertebrobasilar circulation (Fig. 1). This syndrome is usually asymptomatic due to abundant collateral circulation in head and neck region, and is usually discovered incidentally in ultrasound or angiography. It may also be prompted by clinical findings such as unilateral upper limb pulse and blood pressure [3].

Fig. 1.

Pathology of subclavian steal syndrome.

Decreased blood flow to the brain and affected upper extremity can result in a diverse gamut of symptoms, but can be generally categorized into two main broad categories: (1) Vertebrobasilar insufficiency, (2) Ischemia of the affected extremity. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency results if too much blood is diverted away from intracranial structures. Posterior cerebral circulation is particularly compromised. Collateral circulation to the posterior fossa is primarily through the circle of Willis, principally through the posterior communicating artery. Compromise of this circulation, frequently due to concurrent extracranial carotid stenosis, leads to vertebrobasilar symptomology. Syncope, vertigo, ataxia, seizures and confusion comprise the constellation of symptoms that may result in this situation. Ischemia of the affected extremity is less common and symptomology includes weakness or arm claudication after exercise, paresthesias, or temperature changes on affected side. Both classes of symptoms are particular manifest and classically reproducible when patient acquires certain body postures that increase circulatory demand from distal subclavian artery or the brachial artery of the upper limb [4], [5].

SSS has a wide range of clinical manifestations, and although less common, any compromise of the posterior cerebral circulation can give rise to similar signs and symptoms, as highlighted in this particular case. It is therefore paramount that the clinician be vigilant and informed of such presentations to avoid its morbidity and potential for mortality if misdiagnosed.

2. Case report

A thirty nine year old female presented with gradual onset “usually” postural syncope and vertigo episodes. According to the patient, her likelihood of having a vertigo attack or syncope was greater when suddenly rising from a seated or spine position. Milder and less conspicuous spontaneous episodes would also manifest in certain upper limb positions e.g., sudden lifting of her right arm and prolonged manual work involving the right arm, the latter of which became more evident recently.

Patient did not experience any chest pain, palpitations or signs and symptoms of epilepsy prior to or following these syncope episodes. She regained consciousness from these episodes in few seconds without any urinary or fecal incontinence. She did not have any auditory difficulties, tinnitus, ear infections, or trauma, all of which can be normally attributed to this clinical presentation.

When initially presented to the clinic, routine tests were performed and results excluded cardiac pathologies, medications, autonomic pathologies, or auditory pathologies. EEGs and other neurologic physical examinations were also normal. When directed to the vascular clinic, a diagnosis of subclavian steal syndrome was high on the clinician’s list of differential diagnoses. However, no blood pressure differential between arms or vascular pathology in hands was noted, both clinical features of which are normally seen in patients with subclavian steal syndrome.

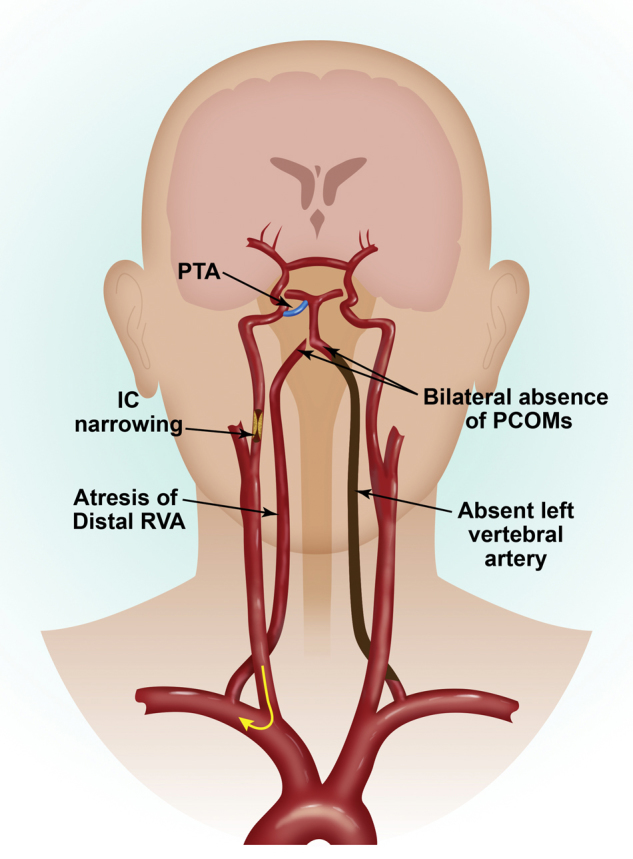

Subsequent CTA angiography showed normal subclavian arteries, ruling out SSS entirely. Abnormal findings included a persistent right trigeminal artery, atresis of the left vertebral artery and distal segment of right vertebral artery, and bilateral absence of the posterior communicating arteries (PCOMs). A significant anterograde vertebrobasilar circulation was absent. The right internal carotid artery (ICA) had atherosclerotic plaque with 75% narrowing of the lumen. Patient was asymptomatic after undergoing a carotid endocartectomy.

3. Discussion

In a healthy adult, two vertebral arteries form the basilar artery, which connects to the anterior circulation through bilateral posterior communicating arteries, comprising the Circle of Willis. In ideal circumstances, the posterior cerebral circulation is maintained with little anterior contribution. However in vascular pathologies in which a cerebral artery is occluded, the Circle of Willis interconnects anterior and posterior circulation allowing collateral blood circulation to target tissues of occluded vasculature to avoid ischemia.

One such pathology that prompts a direct communication between anterior and posterior circulation is the subclavian steal syndrome (SSS). In SSS, the proximal subclavian artery is stenosed, compromising blood flow. As a result, blood travels through ipsilateral vertebral artery to basilar artery, around Circle of Willis, and descends through contralateral vertebral artery to supply affected upper limb [6]. Affected upper limb is supplied by blood flowing down the vertebral artery at the expense of vertebrobasilar circulation, resulting in symptoms such as syncope, vertigo, and neurologic deficits [7]. Patient presented to clinic with similar symptoms, namely syncope and vertigo, with unremarkable cardiac and neurologic physical examinations, prompting a possible diagnosis of SSS. However, no circulatory differences were noted between upper extermities and CT angiography excluded subclavian steal syndrome altogether. CT angiography findings further elucidated medical mystery: atresis of patient’s left vertebral artery, absent posterior communicating arteries due to bilateral fetal posterior cerebral artery (PCA) configuration, and absent distal segments of right vertebral artery (VA) [8]. Patient’s right vertebral artery (VA) ended in the posterior inferior cerebellar artery (PICA). Patient’s vascular configuration resulted in posterior blood supply being almost entirely dependent on anterior circulation through patient’s persistent trigeminal artery (PTA). However, PTA was compromised due to high-grade proximal right internal carotid artery stenosis, resulting in vertebrobasilar insufficiency, manifesting in patient’s neurological symptoms. This particular type of PTA—with an ill-developed basilar artery and absent posterior communicating arteries—has a designated classification of Saltzman type II [9]. An artist’s rendition of patient’s circulation is shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Patient circulation with Saltzmann type 2 PTA and internal carotid artery occlusion.

Vertebrobasilar insufficiency, in which blood flow to the vertebral and basilar arteries is inadequate leading to compromised posterior cerebral circulation, can be caused by a variety of factors such as vaso occlusive disease (e.g., anterior circulation stenosis), developmental anatomical variations or a combination of both [10]. Patients with a persistent posterior trigeminal artery (PTA) can also develop vertebrobasiliar insufficiency. A persistent trigeminal artery, which normally involutes after development of the posterior communicating artery, is present in approximately 0.2% of the population [11], [12]. If persistent, a developmental anomaly is present in which a short, wide fetal connection between the carotid and upper third of basilar artery does not regress. It is assumed that these embryonic connections tend to remain patent due to demand. This is commonly associated with numerous vascular anomalies and disorders not limited to aneurysms and arteriovenous malformations [11]. Pathogenesis of vertebrobasilar insufficiency in patients with PTA may be attributed to the development of microemboli due to artherosclerosis of carotid artery, compromising blood flow; the presence of direct communication between anterior and posterior circulation further exacerbates collateral circulation, jeopardizing vertebrobasiliar system further [11], [13], [14]. Such pathophysiology is presented in this case, in which patient’s congenital abnormalities coupled with atherosclerosis in right ICA resulted in transient insufficient blood flow to posterior part of brain, manifesting as vertigo, syncope and dizziness, which closely mimic features of SSS.

A microembolic pathogenesis may also be considered and is validated as part of the differential diagnosis. The patient’s symptomology could be attributed to microemboli originating from artherosclerosis of the carotid artery, however symptoms disappeared following surgery. If symptoms were due to microemboli, rapid recovery would be unlikely.

Upon review of current literature, another case report presents a similar scenario: symptomology (vertigo and dizziness) as a result of persistent trigeminal artery and occlusive artery disease [15]. Parallels can be drawn between the two case studies. Both patients presented with varied arterial findings that resulted in VBI, which was ultimately resolved by carotid endarterectomy. The importance of identifying relevant arteriographic anatomy in relation to manifestation of VBI—persistent fetal vessels, artery occlusion, tight stenosis, and/or artherosclerosis—is highlighted in both case reports. While the other case focuses mainly on the manifestation of VBI in terms of a persistent trigeminal artery, this report further expands upon this relation and the pathophysiology of VBI, while also drawing similarities and parallels between the manifestation of this condition and the presentation of SSS, applying and relating the condition to a different setting.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Sources of funding

Internal.

Ethical approval

Meets the Scott and White health care ethical approval guidelines for publication.

Consent

Meets the Scott and White health care ethical approval guidelines for publication.

Author contributions

S. Konda and S. Dayawansa: Writing.

S. Singel and J.H. Huang: Reviewing.

Guarantor

J.H. Huang.

Acknowledgements

Authors would like to thank Mr. Bryan Moss, medical illustrator affiliated with Baylor Scott & White Healthcare, Temple, TX for the two illustrations.

References

- 1.Osiro S., Zurada A., Gielecki J., Shoja M.M., Tubbs R.S., Loukas M. A review of subclavian steal syndrome with clinical correlation. Med. Sci. Monit. 2012;18(May (5)):RA57–RA63. doi: 10.12659/MSM.882721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Psillas G., Kekes G., Constantinidis J., Triaridis S., Vital V. Subclavian steal syndrome: neurotological manifestations. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2007;27(February (1)):33–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chan-Tack K.M. Subclavian steal syndrome: a rare but important cause of syncope. South. Med. J. 2001;94(April (4)):445–447. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reivich M., Holling H.E., Roberts B., Toole J.F. Reversal of blood flow through the vertebral artery and its effect on cerebral circulation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1961;265(November):878–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196111022651804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harper C.A., 3rd, Haines J.D., Jr. Subclavian steal syndrome. A report of two cases. Postgrad. Med. 1988;83(February (2)):97–100. doi: 10.1080/00325481.1988.11700138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord R.S., Adar R., Stein R.L. Contribution of the circle of Willis to the subclavian steal syndrome. Circulation. 1969;40(December (6)):871–878. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.40.6.871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Welsh L.W., Welsh J.J., Lewin B., Dragonette J.E. Incompetent circle of Willis and vertebrobasilar insufficiency. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2003;112(August (8)):657–664. doi: 10.1177/000348940311200801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kao C.L., Tsai K.T., Chang J.P. Large extracranial vertebral aneurysm with absent contralateral vertebral artery. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 2003;30(2):134–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saltzman G.F. Patent primitive trigeminal artery studied by cerebral angiography. Acta Radiol. 1959;51(May (5)):329–336. doi: 10.3109/00016925909171103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosenthal D., Cossman D., Ledig C.B., Callow A.D. Results of carotid endarterectomy for vertebrobasilar insufficiency: an evaluation over ten years. Arch. Surg. 1978;113(November (11)):1361–1364. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1978.01370230151019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Azab W., Delashaw J., Mohammed M. Persistent primitive trigeminal artery: a review. Turk. Neurosurg. 2012;22(4):399–406. doi: 10.5137/1019-5149.JTN.4427-11.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alcala-Cerra G., Tubbs R.S., Nino-Hernandez L.M. Anatomical features and clinical relevance of a persistent trigeminal artery. Surg. Neurol. Int. 2012;3:111. doi: 10.4103/2152-7806.101798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirashima Y., Endo S., Koshu K., Takaku A. Vertebrobasilar insufficiency in a patient with persistent trigeminal artery and stenosis of the ipsilateral carotid bifurcation-case report. Neurol. Med. Chir. 1988;28(June (6)):584–587. doi: 10.2176/nmc.28.584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meckel S., Spittau B., McAuliffe W. The persistent trigeminal artery: development, imaging anatomy, variants, and associated vascular pathologies. Neuroradiology. 2013;55(January (1)):5–16. doi: 10.1007/s00234-011-0995-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Battista R.A., Kwartler J.A., Martinez D.M. Persistent trigeminal artery as a cause of dizziness. Ear Nose Throat J. 1997;76(January (1)):43–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]