Highlights

-

•

We present a rare case of exertional paravertebral lumbar compartment syndrome that was initially misdiagnosed as ureteric colic.

-

•

Exertional lumbar paravertebral compartment syndrome typically present with intractable lumbar back pain 6–12 h following lumbar specific exercise.

-

•

There is currently no consensus on management with both conservative and surgical techniques used and case reports the only standard for comparison.

-

•

Long term back pain is more likely in patients managed conservatively.

Keywords: Paravertebral, Compartment, Syndrome, Rhabdomyolysis, Colic

Abstract

Introduction

Ureteric colic frequently presents as loin to groin pain and accounts for a significant proportion of emergency urological admissions. However, a number of differential diagnoses should be considered in a systematic approach when assessing patients.

Presentation of case

We report a case of a 30 year old man admitted with severe unilateral loin to groin pain following lumbar specific weightlifting exercises. After a significant delay due to initial mis-diagnosis he was diagnosed with acute paravertebral lumbar compartment syndrome (PVCS) and managed conservatively.

Discussion

Exertional PVCS is a rare and potentially life threatening condition arising following lumbar specific exercise that has only been recorded a handful of times previously. Patients typically present with intractable lumbar pain and rhabdomyolysis 6–12 h following exercise. Due to initial diagnostic delay our case was managed conservatively with fluid resuscitation and monitoring of renal function.

Conclusion

Assessment of patients with loin pain requires a systematic approach. PVCS is a rare cause of lumbar back and loin pain but one that should be considered, particularly in active young males. Early diagnosis is key to prevent the potential sequalae of untreated rhabdomyolysis. There is currently no consensus on management option for PVCS with only a few cases being reported in the literature. We describe successful management with supportive non operative treatment.

1. Case report

A 30 year old male presented to the emergency department complaining of acute severe left loin pain with a visual analogue score of 10 radiating to his groin. He had vomited four times and was complaining of dysuria and discoloured urine. He had no significant past medical history and took no regular medications. He admitted to smoking cannabis daily but denied other substance misuse. On examination he was afebrile and haemodynamically stable. His chest was clear and abdominal examination revealed left renal angle tenderness with voluntary guarding. Laboratory investigations revealed white cells of 15 × 109/L (reference range 4–11 × 109/L) with a neutrophilia of 13 × 109/L (reference range 1.5–7 × 109/L). CRP was within normal limits. Urine dip was positive for three plus blood. The patient’s main concern was that he had a trapped nerve from a weights session the night before.

He was initially diagnosed with renal colic and admitted for intravenous opioid analgesia and fluid resuscitation. CT kidney, ureter, bladder the next day was difficult to interpret due to paucity of intra-abdominal and retroperitoneal fat but revealed left sided calcifications adjacent to the expected position of the vesicoureteric junction. No proximal obstruction could be visualised and therefore excretory urogram was arranged to confirm the calcification position. Laboratory tests were repeated including liver function tests revealing an AST of 378 U/L (reference range 10–36 U/L). The following day CT urogram reported the pelvic calcifications to be phleboliths lying outside the urinary tract.

The patient was reassessed and found to still be very tender in lumbar area, but also noted to have paravertebral paraesthesia overlying a 10 cm × 15 cm area. Flexion and extension of the spine significantly worsened his pain, as did left hip flexion. Further specifics to the history were clarified; he had participated in a deadlifting weight training session targeting the lumbar muscle groups. MSU remained positive for 3+ blood only. Creatine phosphokinase and LDH were markedly raised, at 42,000 IU/L, and 1314 IU/L respectively. Urine sample was sent to the lab revealing high levels of myoglobin.

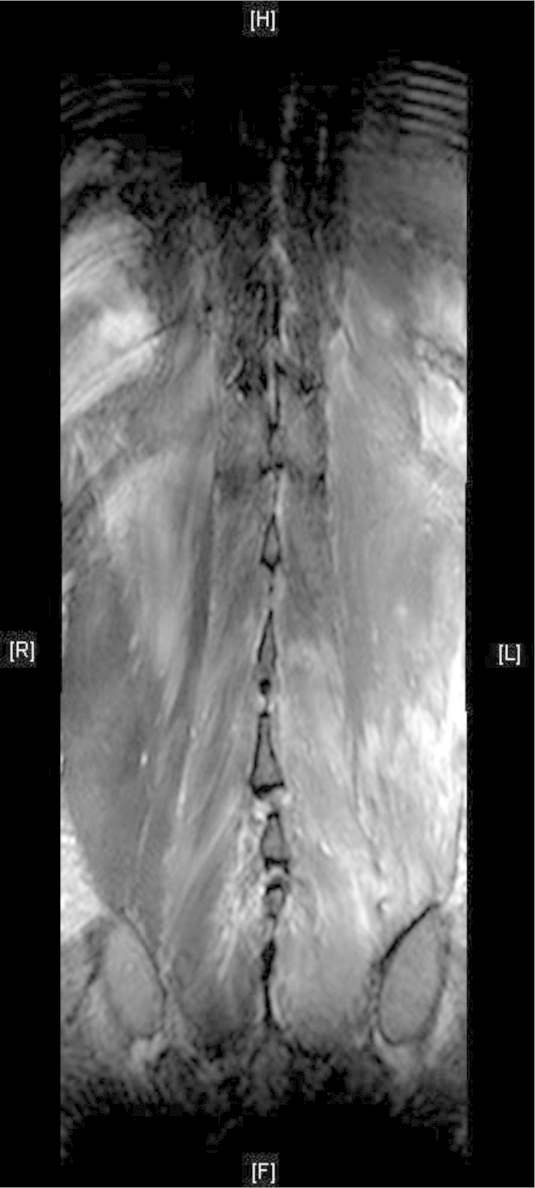

The CT urogram was then re-examined, and the possibility of enlargement and decreased density of the left paravertebral muscles was raised, with an MRI suggested for further investigation (Fig. 1). The MRI confirmed a diagnosis of erector spinae rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome with increased uptake in the left paravertebral muscles suggestive of oedema (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

CT urogram showing enlargement and decreased density of left sided paravertebral muscles. This was not reported on the original scan.

Fig. 2.

MRI lumbar spine with contrast showing enhancement and increased signal of the left erector spinae muscle complex consistent with acute myositis and rhabdomyolysis.

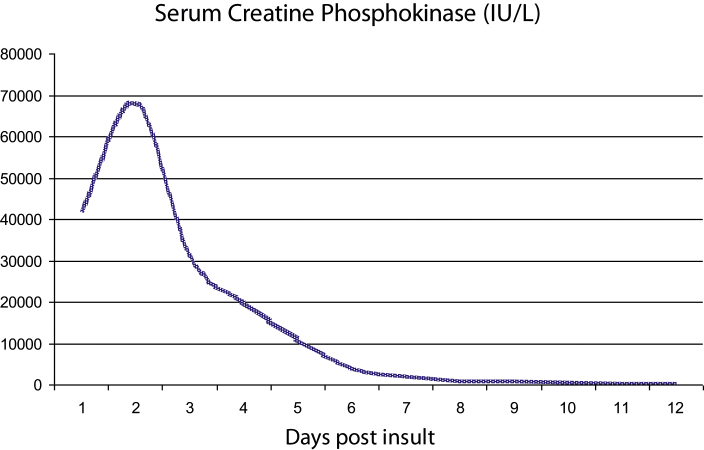

The patient was managed with intravenous fluids resuscitation and analgesia as supportive therapy. The role of surgical fascia decompression was limited due to the risk of introducing infection. Renal function was monitored closely with daily urea, electrolytes, base excess and serum pH being performed. Over the following days CPK increased to 68,000 IU/L before recovering without operative intervention (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Serum creatine phosphokinase over time.

He was discharged around two weeks post admission with significant improvement in back pain and function. At one week post discharge his CK was 224 IU/L, with lumbar pain and parenthesis completely resolved.

2. Discussion

This case demonstrates the importance of having a broad base of differential diagnoses. Loin pain accounts for 25–35% of emergency urological admissions, but only 64% due to renal calculi confirmed on CT [1]. Acute paravertebral lumbar compartment syndrome is a rare differential diagnosis of loin pain, but this case highlights the need for a systematic approach when assessing patients.

Compartment syndrome (CS) has various aetiologies and was first described by Von Volkmann in 1881. CS is caused by raised intra-compartmental pressure of the interstitium over its capillary perfusion pressure impairing capillary flow [2]. Interruption of the local microcirculation causes endothelial destruction, capillary leak, protein loss and accumulation of fluid in the interstitial and intracellular spaces resulting in lack of blood flow to tissues and ischaemia [3]. Untreated, ischaemic tissues can be irreversibly damaged, releasing high levels of muscle enzymes with resulting rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. Treatment is typically with urgent surgical decompression and rehydration to induce diuresis. Initial delay in diagnosis influenced the decision to treat our patient conservatively, as it has been previously demonstrated that in cases of CS with delayed diagnosis >48 h the post-operative risk of infection out weights the benefits of surgery [4].

On review of the literature, in all cases reported of PVCS the main presentation has been intractable lumbar/flank pain with or without radiation 6–12 h following exertion. On examination lumbar erector spinae muscles are tense and swollen with board like rigidity and an overlying area or paraesthsiae. In some cases patients have been found to have tenderness on deep abdominal palpation with reduced or absent bowel sounds. Lumbar lordosis may be reduced and pain was often worse on flexion of the hip and extension and flexion of the spine.

Whilst exertional CS is well described in the hand, forearm, arm, leg and thigh [6], [7], [8], [9], [10], acute exertional paravertebral compartment syndrome (PVCS) has only been reported 15 times previously; (Table 1) On three occasions in downhill skiers [5], [11], [12], once in a surfer [13] and 11 times in weight lifters participating in lumbar specific exercises such as dead lifts [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. All cases were in males with an average age of 28. Acute PVCS has also presented following direct trauma to the area [24] and after surgical procedures such as abdominal aortic aneurysm repair and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass [25], [26], [27], [28].

Table 1.

Summary of examination, biochemical and radiological findings in the known cases of exertional PVCS.

| Carr et al. [5] | Difazio et al. [11] | Kitajima et al. [13] | Khan et al. [12] | Minnema et al. [14] | Paryavi et al. [15] | Wik et al. [16] | Allerton et al. [19] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (year) | 24 | 27 | 25 | 35 | 32 | 20 | 30 | 25 |

| Precipitant | Downhill skiing | Downhill skiing | Surfing | Downhill skiing | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting |

| Loss of lumbar lordosis | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not stated | Not stated |

| Affected side | Bilateral | Bilateral | Left | Bilateral | Right | Bilateral | Bilateral | Right |

| Sensory loss | Not stated | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not stated | Yes |

| Straight leg raise | Exacerbated pain | Exacerbated pain | Not stated | No affect | Exacerbated pain | Exacerbated pain | Not stated | Not stated |

| WBC (×109/L) | 23 | 9 | 8.6 | 9.8 | 9 | 9.6 | 17.4 | Not stated |

| AST (U/L) | 365 | 565 | 196 | 804 | 608 | 504 | Not stated (ALT 156) | Not stated (ALT 389) |

| CK (IU/L) | 5465 | 60,000 | 21,440 | 48,550 | 72,820 | 72,516 | 82,000 | 60,800 |

| LDH (IU/L) | Not stated | Not stated | 505 | 3823 | 2089 | 2089 | Not stated | Not stated |

| CT | Paravertebral muscle swelling | Not done | Not done | Paravertebral muscle swelling | Normal | Paravertebral muscle swelling | Not done | Not done |

| MRI of lumbar paravertebral muscles | Not done | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal left side | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal right side | Increased signal left side | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal right side |

| Compartment pressures (mmHg) | Not done | Left 80, right 70 | Left 14–16, right 4–5 | Left 26, right 44 | Left 21, right 108 | Left 78, right 26 | Left 20, right 150 | Left 7, right 20 |

| Management | Conservative | Conservative | Fasciotomy | Fasciotomy | Fasciotomy | Fasciotomy | Conservative | Conservative; hyperbaric oxygen |

| Karam et al. [20] | Calvert et al. [23] | Mattiassich et al. [17] | Rha et al. case 1 [21] | Rha et al. case 2 [21] | Buckalew et al. [22] | Hoyle et al. [18] | Current case | |

| Age (year) | 23 | 25 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 37 | 24 | 30 |

| Precipitant | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting | Weight lifting |

| Loss of lumbar lordosis | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | yes |

| Affected side | Right | Bilateral | Left | Bilateral | Left | Bilateral | Right | Left |

| Sensory loss | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Not stated | Yes | Not stated | Yes |

| Straight leg raise | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Exacerbated pain |

| WBC (×109/L) | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 19.3 | Not stated | 14.9 |

| AST (U/L) | Not stated | 389 | Not stated | 632 | Elevated | Not stated | Not stated | 585 |

| CK (IU/L) | 77,440 | 60,800 | 43,000 | 67,200 | Elevated | 19,044 | 4949 | 68,000 |

| LDH (IU/L) | Not stated | Not stated | Not stated | 3048 | Elevated | Not stated | Not stated | 1345 |

| CT | Not done | Swelling of lumbar paravertebral erector spinae complex | Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done | Swelling of lumbar paravertebral erector spinae complex |

| MRI of lumbar paravertebral muscles | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal left side | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal left side | Increased signal bilaterally | Increased signal right side | Increased signal left side |

| Compartment pressures (mmHg) | Not done | Left 7, right 20 | Left 47, right 3–10 | Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done | Not done |

| Management | Conservative; hyperbaric oxygen | Conservative | Fasciotomy | Fasciotomy | Fasciotomy | Conservative | Conservative | Conservative |

CS of the extremities is well known and presents classically with severe intractable pain, paraesthesia, pallor, paresis and pain on passive stretching. Not all of these are seen in paravertebral lumbar CS and therefore a high index of suspicion is required. In two other case reports the patients were also originally mis-diagnosed with ureteric colic [15], [18] causing delay in initiating appropriate management.

On review of the literature, in all cases reported of PVCS the main presentation has been intractable lumbar/flank pain with or without radiation 6–12 h following exertion. On examination lumbar erector spinae muscles are tense and swollen with board like rigidity. Paravertebral lumbar paraesthesiae was frequently commented on and many patients complained of tenderness on deep abdominal palpation with reduced or absent bowel sounds. Lumbar lordosis may be reduced and pain was often worse on flexion of the hip and extension and flexion of the spine.

All patients with PVCS presented with features of rhabdomyolysis with raised creatine phosphokinase, AST, ALT, and raised urinary and serum myoglobin. T2 weighted MRI is the gold standard for diagnosis of PVCS with oedema of the affected muscle group. Intra-compartmental pressures can be measured with slit catheter insertion to confirm the diagnosis, but given the clinical, biochemical and radiological findings in our case we did not feel that it was required.

There is no consensus on the treatment of acute exertional PCVS and currently case reports provide the only standard for comparison. Out of the 15 cases reported 7 underwent thoraco-dorsal fasciotomy with immediate improvement in physical symptoms and biochemical parameters. All patients treated surgically recovered well and all were able to return to their previous physical activities over the following 6 months. 8 of the 15 cases were treated conservatively and recovered well from the acute compartment syndrome, although several developed chronic exertional back pain. Conservative measures involve aggressive fluid resuscitation and monitoring of urine output to optimise renal perfusion and prevent acute kidney injury. Two patients with PVCS were treated with hyperbaric oxygen with good outcomes [19], [20].

3. Conclusion

Assessment of patients with loin pain requires a systematic approach and it is important for differential diagnoses to be considered. Paravertebral lumbar compartment syndrome is a rare cause of lumbar back pain/loin pain but one that should be considered, particularly in active young males. Early diagnosis is vital to prevent the potential complications of untreated rhabdomyolysis and to allow consideration of surgical decompression.

PVCS should be managed with aggressive fluid resuscitation and monitoring of urine output to avoid acute kidney injury. Early surgical decompression has good short and long term outcomes, but frequently initial mis-diagnosis causes delay necessitating conservative treatment.

Consent

“Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request”.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Ahmed N.A., Ather M.H., Rees J. Incidental diagnosis of diseases on un-enhanced helical computed tomography performed for ureteric colic. BMC Urol. 2003;3:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-3-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rorabeck C.H. The treatment of compartment syndromes of the leg. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66:93–97. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.66B1.6693486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Volkmann R. Die ischamischen muskellahmungen und kontrakturen. Zentralbl Chir. 1881;8:801–803. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finkelstein J.A., Hunter G.A., Hu R. Lower limb compartment syndrome. J. Trauma. 1996;40:342–344. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carr D., Gilbertson L., Frymoyer J., Krag M., Pope M. Lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome. Spine. 1989;10:816–820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilder R.P. Exertional compartment syndrome. Clin. J. Sports Med. 2010;29:429–435. doi: 10.1016/j.csm.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chopra R., Hayton M., Dunbar P.J.A. Exercise induced chronic compartment syndrome of the first dorsal interosseous compartment of the hand: a case report. Hand. 2009;4:415–417. doi: 10.1007/s11552-009-9203-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boland M.R., Heck C. Acute exercise-induced bilateral thigh compartment syndrome. Orthopaedics. 2009;32:218–221. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20090301-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oh J.Y., Laidler M., Fiala S.C., Hedberg K. Acute exertional rhabdomyolysis and triceps compartment syndrome during a high school football camp. Sports Health. 2011;4:57–62. doi: 10.1177/1941738111413874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.King T.W., Lerman O.Z., Carter J.J., Warren S.M. Exertional compartment syndrome of the thigh: a rare diagnosis and literature review. Am. J. Emerg. Med. 2010;39:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2007.10.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiFazio F.A., Barth R.A., Frymoyer J.W. Acute lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome. A case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73:1101–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Khan R.J., Fick D.P., Guier C.A., Menolascino M.J., Neal M.C. Acute paraspinal compartment syndrome: a case report. J. Bone Joint Surg. 2005;87:1126–1128. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitajima I., Tachibana S., Hirota Y., Nakamichi K. Acute paraspinal muscle compartment syndrome treated with surgical decompression: a case report. Am. J. Sports Med. 2002;2:83–85. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300022301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minnema B.J., Neligan P.C., Quraishi N.A., Fehlings M.G., Prakash S. A case of occult compartment syndrome and nonresolving rhabdomyolysis. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2008;23:871–874. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paryavi E., Jobin C.M., Ludwig S.C., Zahiri H., Cushman J. Acute exertional lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome. Spine. 2010;35 doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181ec4023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wik L., Patterson J.M., Oswald A.E. Exertional paraspinal muscle rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome: a cause of back pain not to be missed. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2010;29:803–805. doi: 10.1007/s10067-010-1391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mattiassich G., Lorenz L., Leitinger M., Trinka E., Wechselberger G., Schubert H. Paravertebral compartment syndrome after training causing severe back pain in an amateur rugby player: report of a rare case and review of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2013;14:259. doi: 10.1186/1471-2474-14-259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoyle A., Tang V., Baker A., Blades R. Acute paraspinal compartment syndrome as a rare cause of loin pain. Ann. R. Coll. Surg. Engl. 2015;97:11–12. doi: 10.1308/003588414X14055925059471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Allerton C., Gawthrope I.C. Acute paraspinal compartment syndrome as an unusual cause of severe low back pain. Emerg. Med. Australas. 2012;24:457–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2012.01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karam M.D. Case report: successful treatment of acute exertional paraspinal compartment syndrome with hyperbaric oxygen therapy. Iowa Orthop. J. 2010;30:188–190. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rha E.Y., Kim D.H., Yoo G. Acute exertional lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome treated with fasciotomy and dermatotraction: case report. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2014;67:425–426. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Buckalew N.A., Lanphere J., Ferrell T. Acute paraspinal compartment syndrome: a diagnosis to consider. PM&R. 2014:6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Calvert N., Bhalla T., Twerenbold R. Acute exertional paraspinal compartment syndrome. ANZ J. Surg. 2015;82:64–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06117.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sava J., Moelleken A., Waxman K. Cardiac arrest caused by reperfusion injury after lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome. J. Trauma. 1999;46:196–197. doi: 10.1097/00005373-199901000-00035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferreira J., Galle C., Aminian A., Michel P., Guyot S., Wilde J.D., Motte S., Wautrecht J., Dereume J.P. Lumbar paraspinal rhabdomyolysis and compartment syndrome after abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J. Vasc. Surg. 2003;37:198–201. doi: 10.1067/mva.2003.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Osamura N., Takahashi K., Endo M., Kurumaya H., Shima I. Lumbar paraspinal myonecrosis after abdominal vascular surgery. Spine. 2000;25:1852–1854. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200007150-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiltshire J.P., Custer T. Lumbar muscle rhabdomyolysis as a cause of acute renal failure after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes. Surg. 2003;13:306–313. doi: 10.1381/096089203764467270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haig A.J., Hartigan A.G., Quint D. Low back pain after nonspinal surgery: the characteristics of presumed lumbar paraspinal compartment syndrome. PM&R. 2009;1:383–388. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]