Highlights

-

•

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a newly described carcinoma of the salivary glands.

-

•

MASC is characterized by morphologic and immunohistochemical features that strongly resemble a secretory carcinoma (SC) of the breast.

-

•

MASC and SC of the breast share the presence of translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25), that results in the formation of an oncogenic fusion gene ETV6-NTK3.

-

•

The majority of MASC present among men and arise from the parotid gland.

-

•

MASC is a low-grade carcinoma with potential for high-grade transformation.

Abstract

Background

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) was first described in 2010 by Skálová et al. This entity shares morphologic and immunohistochemical features with the secretory carcinoma (SC) of the breast. MASC usually presents as an asymptomatic mass in the parotid gland and predominantly affects men. This tumor is considered a low-grade carcinoma but has the potential for high-grade transformation. We report one MASC case and a review of world literature.

Case report

A 66-year-old male patient presented because he noticed a mass of approximately 3 × 3 cm on the right pre-auricular region. Physical examination demonstrated a 3 × 3.5 cm, firm, fixed, non-tender mass in the right pre-auricular region. An MRI of the head and neck showed an ovoid heterogeneous lesion, dependent of the right parotid gland of 27 × 28 mm. We performed a superficial parotidectomy with identification and preservation of the facial nerve. The immunophenotype was positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CK8/18, vimentin, S-100 protein, and mammoglobin. No further surgical interventions or adjuvant therapies were needed. The patient will have a close follow up.

Conclusion

The presence of t(12;15) (p13;q25) translocation which results in the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion or positive immunochemical studies for STAT5, mammoglobin and S100 protein, are necessary to confirm the diagnosis of MASC. MASC treatment should mimic the management of other low-grade malignant salivary gland neoplasms. The inhibition of ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion could be used as treatment in the future.

1. Introduction

Mammary analog secretory carcinoma (MASC) is a newly described carcinoma of the salivary glands, characterized by morphologic and immunohistochemical features, that strongly resembles a secretory carcinoma (SC) of the breast [1]. Secretory carcinoma of the breast (SC) has shown to have a recurrent balanced chromosomal translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25), which leads to an oncogenic fusion gene ETV6-NTRK3. This translocation is also present in MASC [1], [2], [3]. This fusion gene encodes a chimeric tyrosine kinase that is known to play an important role on its oncogenesis [3]. Immunohistochemical similarities between MASC and SC of the breast also include being S100 protein, epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and vimentin positive and “triple negative” (ER/PR/Her2 negative) [4]. MASC predominantly affects men and normally does not behave in an aggressive way [5], [6]. The parotid gland is the most common affected gland by MASC [6], [7]. We present a case of MASC occurring in a 66-year-old, male, Mexican patient that manifested an asymptomatic mass in the pre-auricular region. This article includes information from various case series, in order to present the best recommendations for the diagnosis and treatment of this newly described disease. This case report follows the CARE criteria [8].

2. Case report

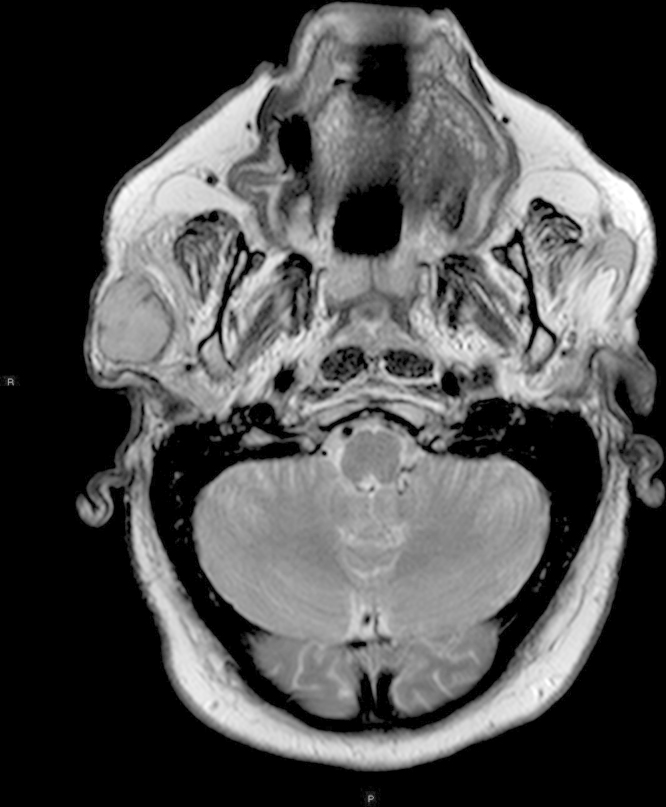

We present a 66-year-old male patient with a past medical history of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and morbid obesity. During the last months, he experienced an intentional weight loss of 18 kg. Due to the body mass loss, he noticed a mass of approximately 3 × 3 cm on the right pre-auricular region. A family practice physician explored the patient and ordered an ultrasound, which reported a necrotic lymph node. There was no other pertinent history. Physical examination demonstrated a 3 × 3.5 cm, firm, fixed, non-tender mass on the right pre-auricular region. Facial nerve function was preserved. No palpable lymphadenopathy was present on the neck region. A head and neck MRI showed an ovoid heterogeneous lesion, dependent of the right parotid gland of 27 × 28 mm, hypointense in T1 and isointense in T2 with well-defined borders and an area of hemorrhage in its interior (Fig. 1). It was reported as a probable pleomorphic adenoma with hemorrhagic transformation.

Fig. 1.

Neck magnetic resonance imaging of the head and neck showing the right parotid lesion.

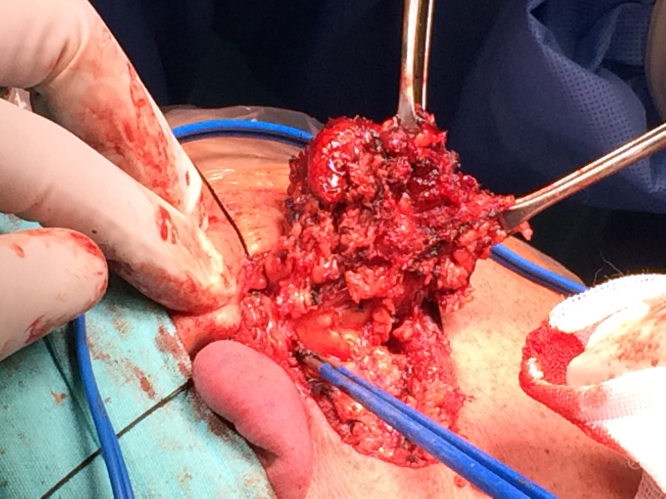

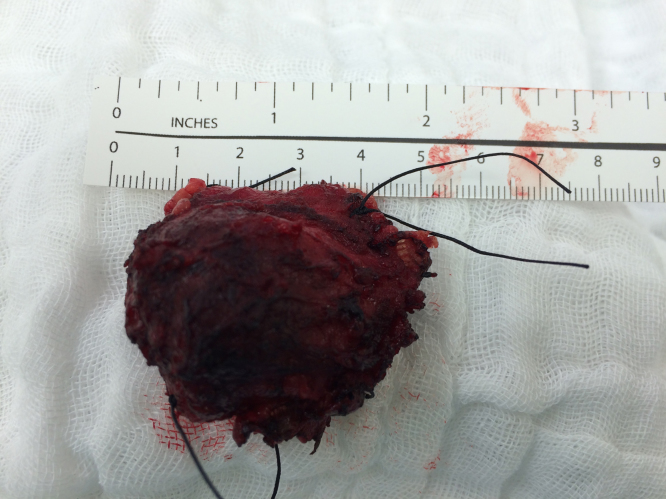

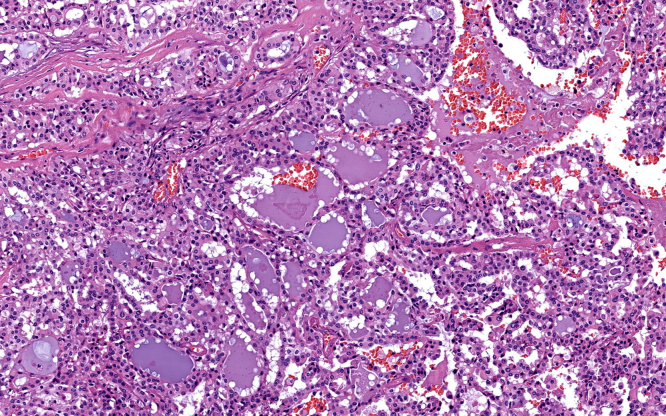

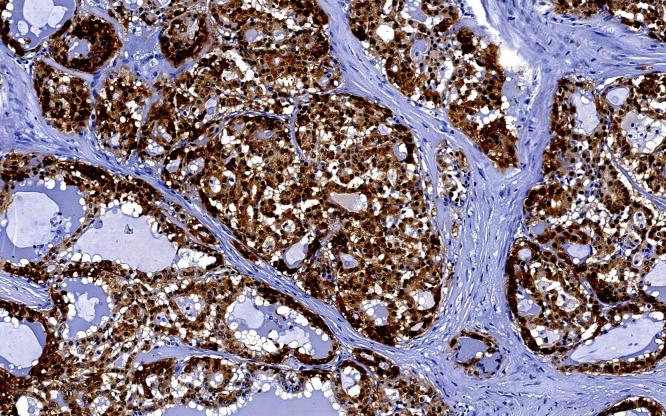

A superficial parotidectomy with identification and preservation of the facial nerve was performed (Fig. 2). The right parotid gland was extracted with a mass of approximately 4 × 4 cm (Fig. 3) and a No. 10 Blake drain was inserted. The final pathology report revealed a well-differentiated MASC. The neoplasm substituted the normal parotid parenchyma and had well-defined borders. The tumor had a multinodular rearrangement with nodules divided by fibrous septa. The nodules showed a microcystic pattern with papillary structures. The neoplastic cells were medium size, with predominant eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 4). A dense multivacuolated eosinophilic secretion was identified inside de cysts. The cellular nucleus was medium size, with smooth borders and homogeneous chromatin. There was no significant number of mitoses or necrotic areas. The immunophenotype was positive for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), CK8/18, vimentin, S-100 protein (Fig. 5), and mammoglobin. There was no expression of p63, CK5/6, DOG1 or zymogen granule formation. The surgical margins were negative for malignancy.

Fig. 2.

Superficial parotidectomy with preservation of the facial nerve.

Fig. 3.

Superficial parotidectomy surgical specimen.

Fig. 4.

Hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Fig. 5.

Immunohistochemical study for S-100 protein.

The final diagnosis was MASC staged as a pT2, cN0, cM0, stage II, R0 salivary carcinoma. The patient presented slight facial nerve dysfunction (grade II House–Brackmann facial nerve grading system), that recovered approximately one month after surgery. The Blake drain was removed on the twelfth day after the procedure. After discussing the case in our multidisciplinary tumor board, no further surgical intervention (total parotidectomy or selective neck dissection) or adjuvant therapy (radiation) was recommended. The patient will have a close follow up that would entail a complete history and physical examination every 3 months for the first 5 years. There is no evidence of persistent or recurrent disease 4 months post-surgery and the facial nerve function is back to baseline.

MASC was first described in 2010 by Skálová et al. in a clinicopathologic study of a series of 16 salivary gland tumors with histomorphologic and immunohistochemical features similar to SC of the breast [1]. One of the principal similarities between MASC and SC of the breast is the presence of the translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25), that results in the formation of the oncogenic fusion gene ETV6-NTK3 [1], [2], [3], [4], which is also present in other tumors such as infantile fibrosarcoma [3], [4], [9], myelogenous leukemia [3], and congenital mesoblastic nephroma [1], [3], [4], [10]. The fusion of the transcriptional regulator gene ETV6 and the membrane receptor kinase-type NTRK3 results in a chimeric tyrosine kinase that activates cell proliferation and increases survival of the tumor cells playing a fundamental role on its oncogenesis [3], [11]. MASC and SC of the breast also share immunohistochemical features such as being positive for S100 protein, EMA, and vimentin, while being “triple negative” (ER/PR/Her2 negative) [4].

The most important differential diagnosis for MASC is the ACC [3]. ACC is characterized by the presence of large, serous, acinar cells with cytoplasmatic PAS positive zymogen-like granules that are absent in MASC [1], [12]. MASC is histologically characterized by the proliferation of uniform eosinophilic cells with a vacuolated cytoplasm, growing within a microcystic, macrocystic, and papillary architecture [13], [14], [15]. Even though the similar growth rate between MASC and ACC, MASC is more likely to metastasize to the regional lymph nodes, it should be considered as a more aggressive tumor compared with the regular low grade ACC [16].

MASC has a slight preference for male patients while ACC mainly affects women [7]. In Table 1, we state the gender preferences of MASC from nine case series published between 2010 and 2014. Immunophenotypic features that can be used to differentiate MASC from ACC are the expression of protein S100 and positive mammaglobin staining [3]. S100 is strongly positive in MASC, while it is negative in ACC [17]. Immunohistochemistry is also helpful in differentiating SDC from MASC because SDC normally expresses androgen receptors or HER-2/neu and not S100 protein [3]. Vimentin, STAT5a and cytokeratin 7 are other important immunohistochemical markers present in MASC [7]. MASC has also been misdiagnosed as cystadenocarcinoma because of the cystic component that is sometimes present [4].

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with MASC diagnosis in nine case series.

| Case series author | Publish year | Number of cases | Male | Female | Mean age | Age range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skálová et al. [1] | 2010 | 16 | 9 | 7 | 46 | 21–75 |

| Connor et al. [4] | 2012 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 40 | 14–77 |

| Chiosea et al. [17] | 2012 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 45.5 | NA |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 2013 | 5 | 3 | 2 | 52 | 21–78 |

| Griffith et al. [14] | 2013 | 6 | 3 | 3 | 43.7 | 27–66 |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 2013 | 11 | 4 | 7 | 56 | 20–86 |

| Skálová et al. [5] | 2014 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 63 | 55–73 |

| Majewska et al. [3] | 2014 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 51.4 | 17–73 |

| Serrano-Arévalo et al. [18] | 2014 | 4 | 1 | 3 | 50.5 | 28–83 |

NA indicates not available.

MASC usually presents as a painless, non-tender mass that increases in size overtime [1], [18]. The majority of MASC arise from the parotid gland, accounting for two thirds of the reported cases [2]. Table 2 presents the location, size, and lymph node involvement of MASC in eight case series. Bishop found that the mean age for presentation of MASC is 47 years (Table 2), in contrast with SC of the breast that usually occurs in younger patients [19]. MASC is considered a low-grade carcinoma with a favorable prognosis; according to Skálová et al. it has moderate risk for local recurrence (15%), lymph node metastases (20%), and a low risk for distant metastases (5%) [1], [5]. In Table 3 we present the clinical follow up of six case series. There have been reports of high-grade transformation in MASC in which it becomes a far more aggressive tumor with an accelerated clinical course that results in cancer dissemination and death [5].

Table 2.

Size, location, and lymph node involvement of MASC in eight case series.

| Case series author | Number of cases | Size (cm) |

Location |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Range | Parotid gland | Submandibular gland | Minor salivary glands in the buccal mucosa | Lips | Palate | Lymph node involvement at time of diagnosis | ||

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 16 | 2.1 | 0.7–5.5 | 13 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Connor et al. [4] | 7 | 1.8 | 0.5–0.3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 5 | 1.9 | 0.8–4.0 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Griffith et al. [14] | 6 | 1.72 | 1.0–2.5 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 11 | 0.9 | 0.3–2.0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 0 |

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 3 | 3.6 | 3.0–4.0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Majewska et al. [3] | 7 | 2.8 | 2.0–4.0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Serrano-Arévalo et al. [18] | 4 | 2.6 | 0.5–7.5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

NA indicates non available.

Table 3.

Clinical follow up of MASC in six case series.

| Case series author | Number of cases | Clinical follow up |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients with clinical follow up | Time range (months) | Recurrences | Dissemination to cervical lymph nodes | Death | ||

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 16 | 13 | 3–120 | 3 | 1 | 2 |

| Griffith et al. [14] | 6 | 5 | 2–6 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 11 | 10 | 4–85 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 3 | 3 | 24–72 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Majewska et al. [3] | 7 | 7 | 67–120 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Serrano-Arévalo et al. [18] | 4 | 2 | 10–20 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

The definite diagnosis of MASC is done by confirming the translocation t(12;15) (p13;q25), which results in the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion [15]. However, a negative test for ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion does not rule out the diagnosis of MASC [1], [18], it can also be done with the presence of positive immunohistochemical studies for STAT5, mammoglobin, and S-100 protein [16], [18]. We revised the data from different case series regarding the presence of ETV6-NTK3 gene rearrangement and the immunohistochemical findings of MASC and stated it on Table 4.

Table 4.

Presence of ETV6-NTK3 gene rearrangement and immunohistochemical findings of MASC in nine case series.

| Case series author | Number of cases | ETV6-NTRK3 gene rearrangement | Immunohistochemical findings |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S-100 | Vimentin | EMA | Mammaglobin | STAT5a | |||

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 16 | 13 | 16 | 16 | 9 | 16 | 16 |

| Connor et al. [4] | 7 | 7 | 5 | 4 | NA | NA | NA |

| Chiosea et al. [17] | 10 | 10 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 5 | 5 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Griffith et al. [14] | 6 | 3 | 2 | NA | NA | 1 | NA |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 11 | 11 | 11 | NA | NA | 7 | NA |

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | NA | 3 | NA |

| Majewska et al. [3] | 7 | 6 | 7 | 7 | NA | 7 | 7 |

| Serrano-Arévalo et al. [18] | 4 | 3 | 4 | NA | NA | 4 | 4 |

NA indicates non available.

The treatment of MASC is not well defined because most studies in the literature are retrospective in nature [19]. The reported disease free period for MASC ranges from 71 to 115 months, shorter than the one reported in ACC, which is 92–148 months [16]. Table 5 presents different treatment alternatives that have been used for MASC. The treatment of choice in high-grade transformation MASC should be radical surgery with neck dissection in addition to adjuvant radiotherapy [5]. In the future, the inhibition of ETV6-NTRK3 may become a therapeutic target for patients with MASC as for other tumors that express this mutation (Table 5) [20].

Table 5.

Treatment of MASC in different case series.

| Case series author | Number of cases | Treatment |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative parotidectomy | Non-radical parotidectomy | Resection of the tumor | Radical parotidectomy | Radiotherapy | Neck dissection | Chemotherapy | ||

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 16 | 3 | 10 | 0 | 3 | 7 | 1 | 0 |

| Connor et al. [4] | 7 | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Griffith et al. [14] | 6 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Bishop et al. [2], [15] | 11 | 0 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Skálová et al. [1], [5] | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Majewska et al. [3] | 7 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Serrano-Arévalo et al. [18] | 4 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | NA |

NA indicates non available.

3. Conclusion

MASC is a salivary gland tumor first described in 2010, which is characterized by histologic, immunophenotypic, and genetic similarities to SC of the breast. MASC and SC of the breast share the t(12;15) (p13;q25) translocation which results in the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion, they are also both positive for S100 protein, EMA, and vimentin and “triple negative” (ER/PR/Her2). Confirming the presence of ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion or positive immunochemical studies for STAT5, mammoglobin and S100 protein are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. MASC is considered a low-grade carcinoma with a favorable prognosis, so at this time, treatment should mimic the management of other low-grade malignant salivary gland neoplasms. When high-grade transformation occurs, a more aggressive multidisciplinary management should be undertaken because of its poor prognosis. The inhibition of ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion could be used as treatment in the future.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

There was no need for ethical approval.

Author contributions

Balanzá Ricardo: Writing, and data analysis.

Muñoz Manuel: Data collection.

Moreno Eduardo: Data collection.

Luque Enrique: Data collection.

Cordera Fernando: Data collection.

Arrangoiz Rodrigo: Data analysis, writing, and study design.

Toledo Carlos: Data collection.

Gonzalez Edgar A: Data collection.

Guarantors

Balanzá Ricardo

Arrangoiz Rodrigo

Contributor Information

Ricardo Balanzá, Email: balanza.ricardo@gmail.com.

Rodrigo Arrangoiz, Email: rodrigo.arrangoiz@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Skálová A., Vanecek T., Sima R. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands, containing the ETV6-NTRK3 fusion gene: a hitherto undescribed salivary gland tumor entity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2010;34:599–608. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181d9efcc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bishop J., Yonescu R., Bastista D. Most nonparotid actinic cell carcinomas represent mammary analog secretory carcinomas. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2013;37:1053–1057. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3182841554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Majewska H., Skálová A., Stodulski D. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands: a new entity associated with ETV6 gene rearrangement. Virchows Arch. 2014 doi: 10.1007/s00428-014-1701-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connor A., Perez-Ordoñez B., Shago M. Mammary analog secretory carcinoma of salivary gland origin with the ETV6 gene rearrangement by FISH: expanded morphologic and immunohistochemical spectrum of a recently described entity. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2012;36:27–34. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318231542a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skálová A., Vanecek T., Majewska H. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with high-grade transformation report of 3 cases with the ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion and analysis of TP53, beta-catenin, EGFR, and CCND1 genes. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014;38:23–33. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levine P., Fried K., Krevitt L. Aspiration biopsy of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of accessory parotid gland: another diagnostic dilemma in matrix-containing tumors of the salivary glands. Diagn. Citopathol. 2012;42:49–53. doi: 10.1002/dc.22886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuroda N., Miyazaki K., Michal M. Small mammary analogue secretory carcinoma arising from minor salivary gland of buccal mucosa. Int. Cancer Conf. J. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 8.and the CARE Group. Gagnier J., Kienle G., Altman D.G., Moher D., Sox H., Riley D.S. The CARE guidelines: consensus-based clinical case report guideline development. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2013;67(1):46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Knezevich S.R., McFadden D.E., Tao W. A novel ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion in congenital fibrosarcoma. Nat. Genet. 1998;18:184–187. doi: 10.1038/ng0298-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rubin B.P., Chen C.J., Morgan T.W. Congenital mesoblastic nephroma t(12;15) is associated with ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion: cytogenetic and molecular relationship to congenital (infantile) fibrosarcoma. Am. J. Pathol. 1998;153:1451–1458. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65732-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Knezevich S.R., Garnett M.J., Pysher T.J., Beckwith B., Grundy P., Sorensen P. ETV6-NTRK3 gene fusion and trisomy 11 establish a histogenetic link between mesoblastic nephroma and congenital fib-rosarcoma. Cancer Res. 1998;15:5046–5048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis G.L.A., Auclair P.L. Acinic cell adenocarcinoma. In: Ellis G.L.A., Auclair P.L., editors. AFIP Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Salivary Glands. ARP Press; Washington, D.C: 2008. pp. 204–224. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hirokawa M., Sugihara K., Sai T. Secretory carcinoma of the breast: a tumour analogous to salivary gland acinic cell carcinoma? Histopathology. 2002;40:223–229. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2002.01346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Griffith C., Stelow E., Saqi A. The cytological features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma a series of 6 molecularly confirmed cases. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:234–241. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bishop J., Yonescu R., Batista D. Cytopathologic features of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:228–233. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiosea S.I., Griffith C., Assaad A., Seethala R.R. Clinicopathological characterization of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Histopathology. 2012;61:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2012.04232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chiosea S., Griffith C. The profile of acinic cell carcinoma after recognition of mammary analog secretory carcinoma. Am. J. Sug. Pathol. 2012;36:343–350. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318242a5b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Serrano-Arévalo M.L., Mosqueda-Taylor A., Domínguez-Malagón H., Michal M. Mammary analogue secretory carcinoma (MASC) of salivary gland in four mexican patients. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2014 doi: 10.4317/medoral.19874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bishop J. Unmasking MASC: bringing to light the unique morphologic, inmunohistochemical and genetic features of the newly recognized mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2013;7:35–39. doi: 10.1007/s12105-013-0429-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tognon C.E., Somasiri A.M., Evdokimova V.E. ETV6-NTRK3-mediated breast epithelial cell transformation is blocked by targeting the IGF1R signaling pathway. Cancer Res. 2011;71:1060–1070. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]