Abstract

Objectives

The efficacy and hepatic safety of the non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors rilpivirine (TMC278) and efavirenz were compared in treatment-naive, HIV-infected adults with concurrent hepatitis B virus (HBV) and/or hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in the pooled week 48 analysis of the Phase III, double-blind, randomized ECHO (NCT00540449) and THRIVE (NCT00543725) trials.

Methods

Patients received 25 mg of rilpivirine once daily or 600 mg of efavirenz once daily, plus two nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors. At screening, patients had alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase levels ≤5× the upper limit of normal. HBV and HCV status was determined at baseline by HBV surface antigen, HCV antibody and HCV RNA testing.

Results

HBV/HCV coinfection status was known for 670 patients in the rilpivirine group and 665 in the efavirenz group. At baseline, 49 rilpivirine and 63 efavirenz patients [112/1335 (8.4%)] were coinfected with either HBV [55/1357 (4.1%)] or HCV [57/1333 (4.3%)]. The safety analysis included all available data, including beyond week 48. Eight patients seroconverted during the study (rilpivirine: five; efavirenz: three). A higher proportion of patients achieved viral load <50 copies/mL (intent to treat, time to loss of virological response) in the subgroup without HBV/HCV coinfection (rilpivirine: 85.0%; efavirenz: 82.6%) than in the coinfected subgroup (rilpivirine: 73.5%; efavirenz: 79.4%) (rilpivirine, P = 0.04 and efavirenz, P = 0.49, Fisher's exact test). The incidence of hepatic adverse events (AEs) was low in both groups in the overall population (rilpivirine: 5.5% versus efavirenz: 6.6%) and was higher in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients than in those not coinfected (26.7% versus 4.1%, respectively).

Conclusions

Hepatic AEs were more common and response rates lower in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients treated with rilpivirine or efavirenz than in those who were not coinfected.

Keywords: TMC278, efavirenz, hepatitis, hepatic safety, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, HBV, HCV

Introduction

As HIV type-1 (HIV-1), hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) share transmission routes, patients with HIV are frequently coinfected with HBV or HCV. Approximately 2–4 million HIV-infected people worldwide have chronic HBV and 4–5 million have chronic HCV coinfection.1 In Western Europe and the USA, chronic HBV infection has been found in 6%–14% and HCV infection in 25–30% of HIV-positive individuals.1 Data suggest that coinfection affects the overall survival of HIV-infected patients, with a 3.6- to 8-fold increased risk of liver-related mortality in HIV/HBV-coinfected individuals.2,3 Furthermore, in both HCV- and HBV-infected patients, HIV coinfection has been associated with more rapid progression of viral hepatitis-related liver disease (e.g. cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, hepatocellular carcinoma and liver failure).3–5

Antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) that are active against HIV and HBV, such as tenofovir, lamivudine and emtricitabine, can directly suppress HBV replication and thus prevent or slow the progression of liver disease.6–8 Although HCV replication is not inhibited by antiretroviral treatment, HCV treatment outcomes can improve as a result of suppressed HIV replication and increased CD4 cell count.9 Based on these findings, current HIV therapy guidelines recommend that HIV patients with HBV, and possibly with HCV coinfection, begin highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART), regardless of their CD4 cell count.10–12

Several studies have shown that hepatotoxicity can occur with any antiretroviral and the risk of severe toxicity following initiation of HAART is higher in HBV- or HCV-coinfected individuals.13–20 Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) have been associated with hepatotoxicity, both in clinical trials and in practice.21–25 Liver-related adverse events (AEs) occur less frequently with efavirenz than with nevirapine. The frequency of severe elevations in liver transaminases ranges from 1% to 8% in patients receiving efavirenz26–33 compared with from 4% to 18% in patients receiving nevirapine.23,29–34 In addition, nevirapine hepatotoxicity has been more frequent in females and in individuals with higher CD4 cell counts at the initiation of HAART.25,35

The NNRTI rilpivirine (TMC278; EDURANT®) has recently been approved for use in the USA, Canada and Europe in combination with other ARVs in HIV-1-infected treatment-naive adult patients.36–38 Rilpivirine has been compared with efavirenz, each in combination with two nucleoside/nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors [N(t)RTIs], in two Phase III, randomized, double-blind, double-dummy trials [ECHO (TMC278-C209, NCT00540449) and THRIVE (TMC278-C215, NCT00543725)] in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected adults. In the pooled week 48 primary analysis of the two trials, compared with efavirenz, rilpivirine had non-inferior efficacy and a more favourable tolerability profile, with lower overall incidences of treatment-related grade 2–4 AEs, rash and neuropsychiatric AEs, and smaller lipid increases.39

Given that HIV patients coinfected with HBV and/or HCV have a higher risk of developing hepatic-related AEs with NNRTIs,32,40 we analysed the efficacy and safety of rilpivirine compared with efavirenz in this subgroup of patients, using pooled week 48 Phase III data from the ECHO and THRIVE trials.

Methods

Trial design

ECHO and THRIVE were two Phase III, double-blind, double-dummy, international randomized trials in treatment-naive, HIV-1-infected adults (NCT00540449 and NCT00543725, respectively; www.clinicaltrials.gov). Their primary objective was to determine whether rilpivirine was non-inferior to efavirenz in overall response [confirmed viral load <50 copies/mL, intent to treat, time to loss of virological response (ITT-TLOVR), 12% non-inferiority margin] at week 48. The trial design and methods have been reported in detail for the individual trials.41,42

The main inclusion criteria were viral load ≥5000 copies/mL, absence of NNRTI resistance-associated mutations (based on a list of 39 out of 44 known NNRTI mutations)41–43 and susceptibility to the N(t)RTIs in the background regimen as determined by virco®TYPE HIV-1 (Virco, Beerse, Belgium). Patients with clinically significant hepatic impairment or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and/or aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels that were five times above the upper limit of normal were excluded from the trials. Patients diagnosed with acute clinical viral hepatitis during the trial were withdrawn. The HBV and HCV status was determined at baseline by HBV surface antigen, HCV antibody and HCV RNA testing.

The patients were randomized 1 : 1 to receive 25 mg of rilpivirine once daily or 600 mg of efavirenz once daily, plus a combination of two N(t)RTIs: tenofovir/emtricitabine in the ECHO trial and investigator-selected tenofovir/emtricitabine, zidovudine/lamivudine or abacavir/lamivudine in the THRIVE trial.

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Trial protocols were reviewed and approved by the appropriate institutional Ethics Committees and Health Authorities, and the trials were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

AEs were assessed using the Clinical Trials Group's ‘Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Paediatric Adverse Events’ (version 1.0, December 2004).44 Reported AEs were classified using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA version 11.0).45

Trial and subanalysis assessments

Efficacy and safety data were analysed according to HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status. The efficacy analysis included only patients with HBV/HCV status available at baseline and data gathered up to week 48. The safety analysis included all patients and all available data, including those beyond week 48. The cut-off date for this analysis was 28 January 2010 for THRIVE and 1 February 2010 for ECHO. In addition, patients who seroconverted for HBV/HCV during the trials were considered as HBV/HCV coinfected in the safety analysis. Pharmacokinetic data were collected and population-based pharmacokinetic parameters determined.

The ITT population was used for all efficacy analyses and all evaluations were performed on pooled data from the two trials. Response rate (defined as the proportion of patients with viral load <50 copies/mL) at week 48 was determined using the TLOVR algorithm. In post-hoc analyses, Fisher's exact test was used to compare differences in the response rates between different subgroups and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for differences in the CD4 cell counts. The incidences of hepatic AEs and laboratory abnormalities were assessed on all available safety data from the trials. Fisher's exact test (post-hoc analysis) was used to compare safety differences between the treatment groups. The Wilcoxon rank-sum test (post-hoc analysis) was used to compare population pharmacokinetic data.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

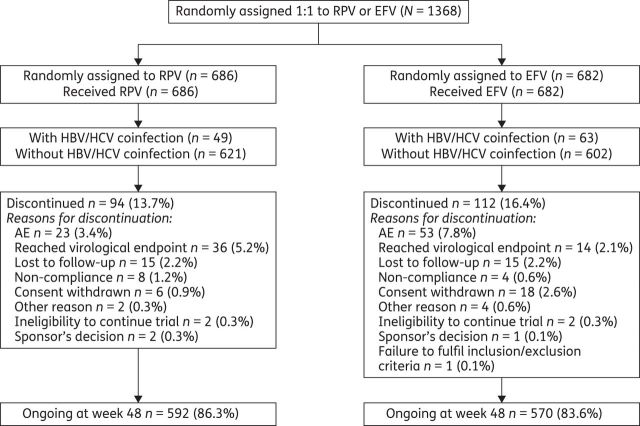

A total of 1368 patients were randomized and treated in the two trials (N = 686 in the rilpivirine group and N = 682 in the efavirenz group; Figure 1). At baseline, the median viral load was 5.0 log10 copies/mL and the median CD4 cell count was 256 cells/mm3. Demographics and baseline characteristics were well-balanced between the treatment groups within each trial; the median treatment duration was 56 weeks in both groups.39

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram showing patient disposition for the pooled primary analysis of ECHO and THRIVE. RPV, rilpivirine; EFV, efavirenz.

At baseline, the HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status was determined in 1335 patients (N′ = 670 in the rilpivirine group and N′ = 665 in the efavirenz group). A total of 8.4% (112/1335) of patients were coinfected with HBV and/or HCV: 7.3% (49/670) of patients in the rilpivirine group and 9.5% (63/665) in the efavirenz group. HBV and HCV coinfection occurred at similar frequencies, with 55/1357 patients (4.1%) being HBV positive and 57/1333 patients (4.3%) being HCV positive.

During the trial, an additional eight patients seroconverted for HBV/HCV (five patients in the rilpivirine group and three in the efavirenz group). Data from these patients were included in the coinfected subgroup in the safety analysis.

Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of patients with known HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status. The baseline disease characteristics were suggestive of a slightly more advanced HIV infection stage in patients in the rilpivirine-coinfected group than in the other groups (Table 1).

Table 1.

ECHO and THRIVE: baseline characteristics of patients according to HBV and/or HCV coinfection status at baseline (N = 1335)

| Parameter | HIV patients with HBV/HCV coinfection |

HIV patients without HBV/HCV coinfection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 49 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 63 | 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 621 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 602 | |

| Patient demographics | ||||

| male, % | 77.6 | 73.0 | 75.2 | 76.4 |

| Caucasian/white, % | 46.9 | 50.8 | 62.6 | 60.6 |

| age (years), median (range) | 38 (25–78) | 35.5 (22–63) | 36 (18–74) | 36 (19–69) |

| Disease characteristics | ||||

| HIV-1 viral load (log10 copies/mL), median (range) | 5.2 (3.2–6.2) | 5.0 (3.2–6.1) | 4.9 (2.2–7.3) | 5.0 (3.0–6.7) |

| HIV-1 viral load >100 000 copies/mL, % | 61.2 | 47.6 | 44.8 | 51.8 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3), mean (95% CI) | 230 (198–263) | 246 (216–276) | 262 (251–273) | 274 (262–285) |

| CDC category C, % | 8.2 | 4.8 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

RPV, rilpivirine; EFV, efavirenz.

Efficacy outcomes by treatment group at week 48

The response rate was greater overall in the subgroup of HIV patients without HBV/HCV coinfection than in the subgroup of HIV/HBV- and/or HIV/HCV-coinfected patients (P = 0.06; Fisher's exact test) (Table 2). Among patients with HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection, 73.5% and 79.4% of patients in the rilpivirine and efavirenz groups, respectively, achieved viral load <50 copies/mL, whereas in non-coinfected patients the response rates were 85.0% and 82.6%, respectively (Table 2). This difference between coinfected and non-coinfected patients was significant for rilpivirine (P = 0.04), though not for efavirenz (P = 0.49, Fisher's exact test).

Table 2.

Pooled week 48 efficacy outcomes for patients with known HBV and/or HCV coinfection status at baseline (N = 1335)

| Efficacy parameters at week 48a | HIV patients with HBV/HCV coinfection |

HIV patients without HBV/HCV coinfection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 49 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 63 | 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 621 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 602 | |

| Patients with viral load <50 copies/mL (ITT-TLOVR), % (95% CI) | 73.5 (61–86) | 79.4 (69–90) | 85.0 (82–88) | 82.6 (80–86) |

| Virological failures, n (%) | 5 (10.2) | 3 (4.8) | 55 (8.9) | 30 (5.0) |

| Discontinuation due to AE/death, n (%) | 2 (4.1) | 6 (9.5) | 13 (2.1) | 40 (6.6) |

| Discontinuation due to reason other than AEb, n (%) | 6 (12.2) | 4 (6.3) | 25 (4.0) | 35 (5.8) |

| Change in CD4 count (NC = Fc) from baseline (cells/mm3), mean (95% CI)d | +137 (100–175) | +192 (147–238) | +197 (186–209) | +173 (161–185) |

RPV, rilpivirine; EFV, efavirenz.

aPatients included in efficacy analysis were those with baseline HBV/HCV assessments.

bLost to follow-up, non-compliance, withdrew consent, ineligible to continue, sponsor's decision.

cNC = F, non-completer = failure: missing values after discontinuation imputed with change = 0; last observation carried forward otherwise.

dN′ = 48 for rilpivirine for HBV- and/or HCV-coinfected patients.

Similarly, for rilpivirine the mean improvement in the CD4 cell count was higher in the subgroup of HIV patients without coinfection than in the subgroup of patients with HBV/HCV coinfection (Table 2). In patients with coinfection, the mean increase in the absolute CD4 cell count from baseline was lower in the rilpivirine group than in the efavirenz group (although the 95% confidence intervals overlapped), while in non-coinfected patients the mean increase was higher in the rilpivirine group (with no overlap in the confidence intervals, Table 2). The change from baseline in the CD4 cell count was statistically significant for each of the four subgroups (P < 0.0001; Wilcoxon signed-rank test).

HBV or HCV coinfection did not significantly influence rilpivirine or efavirenz pharmacokinetics, with no effect on the area under the concentration–time curve (AUC24) of rilpivirine or efavirenz compared with non-coinfected patients (rilpivirine, P = 0.45; efavirenz, P = 0.71; Wilcoxon rank-sum test).

Hepatic safety and tolerability by treatment group in the overall patient population

The overall incidence of hepatic AEs was low [5.5% (38/686) for rilpivirine versus 6.6% (45/682) for efavirenz]. Hepatic AEs considered at least possibly related to treatment by the investigator (treatment-related AEs) occurred in 2.2% (15/686) of patients in the rilpivirine group and 2.1% (14/682) of patients in the efavirenz group. Increased AST [rilpivirine: 2.3% (16/686) versus efavirenz: 2.8% (19/682)] and increased ALT [1.9% (13/686) versus 2.8% (19/682), respectively] were the most commonly reported hepatic AEs (regardless of causality). All other hepatic AEs occurred in <1% of patients in each treatment group. Most hepatic AEs were asymptomatic grade 1 or 2 increases in transaminase levels.

Serious hepatic AEs (regardless of causality) occurred infrequently in both treatment groups [rilpivirine: 0.4% (3/686) versus efavirenz: 0.7% (5/682)]. Two serious treatment-related hepatic AEs occurred. Both were in the efavirenz group and led to discontinuation: one was a grade 3 increase in both ALT and AST, and one a grade 3 increase in ALT. Hepatic AEs infrequently led to treatment discontinuation, with three patients stopping treatment permanently in the rilpivirine group (0.4%) compared with nine patients in the efavirenz group (1.3%). No fatal hepatic AEs occurred.

Regarding treatment-emergent hepatic laboratory abnormalities, there was a lower incidence of grade 2–4 ALT and AST elevations in the rilpivirine group than in the efavirenz group [ALT: 5.1% (35/685) for rilpivirine versus 9.9% (66/670) for efavirenz, P = 0.0009; AST: 4.8% (33/685) versus 9.0% (60/669), respectively, P = 0.003; Fisher's exact test]. The incidence of grade 2–3 total hyperbilirubinaemia was higher in the rilpivirine group [3.1% (21/685) versus 0.4% (3/670) for efavirenz, P = 0.0003; Fisher's exact test].

Hepatic AEs by HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status

Compared with patients without HBV/HCV coinfection, coinfected patients developed more hepatic AEs and laboratory abnormalities reported as AEs in both treatment groups (Table 3). These were mostly increases in AST and ALT levels.

Table 3.

Frequency of treatment-emergent hepatic AEs by HBV and/or HCV coinfection status (N = 1368)a

| Treatment-emergent hepatic AEs, n (%) | HIV patients with HBV/HCV coinfection |

HIV patients without HBV/HCV coinfection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 54 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 66 | 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 632 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 616 | |

| Any hepatic AE | 15 (27.8) | 17 (25.8) | 23 (3.6) | 28 (4.5) |

| Hepatobiliary disordersb | 3 (5.6) | 7 (10.6) | 6 (0.9) | 9 (1.5) |

| cholelithiasis | — | — | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.2) |

| cytolytic hepatitis | — | 1 (1.5) | — | — |

| abnormal hepatic function | — | 3 (4.5) | — | — |

| hepatic steatosis | — | 2 (3.0) | — | — |

| hepatitis | 1 (1.9) | — | — | 1 (0.2) |

| acute hepatitis | — | — | — | 1 (0.2) |

| hepatomegaly | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.5) |

| hyperbilirubinaemia (total) | 1 (1.9) | — | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| hypertransaminasaemia | — | — | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.3) |

| Incident cases of HBV or HCVc | 3 (5.6) | 5 (7.6) | — | — |

| HBV | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.5) | — | — |

| HCV | 2 (3.7) | 4 (6.1) | — | — |

| Hepatic laboratory abnormalities reported as an AEd | 9 (16.7) | 8 (12.1) | 19 (3.0) | 21 (3.4) |

| abnormal ALT | — | — | 1 (0.2) | — |

| increased ALT | 6 (11.1) | 7 (10.6) | 7 (1.1) | 12 (1.9) |

| increased AST | 7 (13.0) | 5 (7.6) | 9 (1.4) | 14 (2.3) |

| increased blood alkaline phosphatase | — | — | — | 3 (0.5) |

| increased blood bilirubin | — | — | 4 (0.6) | — |

| increased unconjugated blood bilirubin | — | — | 1 (0.2) | — |

| increased hepatic enzyme | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.5) | — | 1 (0.2) |

| abnormal liver function test | — | — | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) |

| increased transaminases | 1 (1.9) | — | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.6) |

RPV, rilpivirine; EFV, efavirenz.

aPatient numbers are higher than for the efficacy analyses because the safety analyses were performed using all available data, including beyond week 48.

bSelection of preferred terms from the System Organ Class, as defined by MedDRA.

cPatients who seroconverted for HBV/HCV during the study were also included in the subgroup of HIV/HBV- and/or HIV/HCV-coinfected patients.

dSelection of preferred terms reported under the System Organ Class of investigations, not hepatobiliary disorders.

Of the two serious hepatic AEs that occurred in the overall population and considered at least possibly related to treatment, one was in a coinfected patient (grade 3 increase in ALT while receiving efavirenz) and led to discontinuation. The other (grade 3 increase in ALT and AST) was in a non-coinfected patient receiving efavirenz.

Three patients in the rilpivirine group discontinued for hepatic AEs; two were HBV/HCV coinfected and one patient had an unknown coinfection status. Of the nine patients in the efavirenz group who discontinued for this reason, six were HBV/HCV coinfected and one patient had an unknown coinfection status. The reason for discontinuation in the two HBV/HCV-coinfected patients in the rilpivirine group was a grade 3 or 4 increase in AST and/or ALT levels (as required by the protocol). One of the six HBV/HCV-coinfected patients in the efavirenz group also discontinued for this reason and the other five discontinued for HCV (n = 2), cytolytic HCV (n = 1), elevated hepatic enzymes (n = 1) and abnormal hepatic function (n = 1).

Hepatic laboratory abnormalities by HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status

In both treatment groups, grade 2–4 increases in hepatic laboratory abnormalities were observed more frequently in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients than in patients who were not coinfected (Table 4). The majority of patients had increased indirect bilirubin above the normal limit. In HBV/HCV-coinfected patients, 3/54 patients (5.6%) in the rilpivirine group and 1/66 patients (1.5%) in the efavirenz group had a treatment-emergent indirect bilirubin level above normal. In patients without HBV/HCV coinfection, the proportions were 32/631 patients (5.1%) versus 2/603 (0.3%), respectively.

Table 4.

Frequency of grade 2–4 treatment-emergent hepatic laboratory abnormalities occurring in ≥2% of patients per treatment group by HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status (N = 1368)a

| Laboratory parameter, n (%) | HIV patients with HBV/HCV coinfection |

HIV patients without HBV/HCV coinfection |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 54 | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 66 | 25 mg of RPV once daily, N = 631b | 600 mg of EFV once daily, N = 604b | |

| Increased alkaline phosphatase | ||||

| all grades | 4 (7.4) | 13 (19.7) | 16 (2.5) | 75 (12.4) |

| grade 2–3c | 0 | 2 (3.0) | 1 (0.2) | 6 (1.0) |

| Increased ALT | ||||

| all grades | 27 (50.0) | 28 (42.4) | 114 (18.1) | 161 (26.7) |

| grade 2–4 | 18 (33.3) | 19 (28.8) | 17 (2.7) | 47 (7.8) |

| Increased ASTd | ||||

| all grades | 22 (40.7) | 24 (36.4) | 94 (14.9) | 146 (24.7) |

| grade 2–4 | 11 (20.4) | 12 (18.2) | 22 (3.5) | 48 (7.9) |

| Hyperbilirubinaemia (total)e | ||||

| all grades | 7 (13.0) | 1 (1.5) | 50 (7.9) | 4 (0.7) |

| grade 2–3c | 4 (7.4) | 1 (1.5) | 17 (2.7) | 2 (0.3) |

RPV, rilpivirine; EFV, efavirenz.

aPatient numbers are higher than for the efficacy analyses because the safety analyses were performed using all available data, including beyond week 48; patients who seroconverted for HBV/HCV during the study were also included in the subgroup of HIV/HBV- and/or HIV/HCV-coinfected patients.

bNumber of patients with data.

cNo grade 4 laboratory abnormality observed.

dData available for 603 patients in the efavirenz non-coinfected group.

eThe majority of patients had increased indirect bilirubin above the normal limit.

Discussion

Analysis of the pooled 48 week data from the ECHO and THRIVE trials showed that rilpivirine and efavirenz have comparable efficacy and hepatic safety profiles in antiretroviral treatment-naive patients coinfected with HIV-1 and HBV or HCV. Response rates were similar for rilpivirine and efavirenz within the HBV/HCV-coinfected and non-coinfected groups. Overall, the response rate was lower in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients than in patients who were not coinfected, with the difference being statistically significant for rilpivirine. The lower overall response rate in coinfected than in non-coinfected patients in the rilpivirine group was due to more discontinuations for reasons other than AEs (12.2% discontinuations for coinfected versus 4.0% for non-coinfected patients, respectively). For efavirenz, the main reason for the lower response rate in coinfected than in non-coinfected patients was a higher discontinuation rate due to AEs (9.5% versus 6.6% for non-coinfected patients). Virological failure rates were similar within each treatment group, regardless of the HIV/HBV and/or HIV/HCV coinfection status (10.2% in coinfected patients versus 8.9% in non-coinfected patients for rilpivirine, and 4.8% and 5.0%, respectively, for efavirenz).

In general, both rilpivirine and efavirenz were well tolerated, with no hepatic safety differences observed. Rilpivirine was, however, associated with a lower incidence of grade 2–4 increases in liver function test enzymes compared with efavirenz. While hyperbilirubinaemia (grade 1–3) was more frequent in the rilpivirine group compared with the efavirenz group, the majority of patients had an increased indirect bilirubin above the normal limit, which is not indicative of hepatic toxicity. This could be due to an interaction with a transporter or due to conjugation, but additional in vitro experiments would be required to explore this further. There have been no signs of haemolysis in pre-clinical or clinical studies. There were no grade 4 cases of hyperbilirubinaemia in either group. Consistent with observations from previous studies,13–19,32,40 hepatic AEs occurred more frequently in HBV- and/or HCV-coinfected patients than in those patients who were not coinfected (26.7% versus 4.1%, respectively). Our results suggest that the liver safety profile of rilpivirine is similar to that of efavirenz.

Hepatotoxicity can lead to morbidity, mortality and the discontinuation of antiretroviral therapy in HIV patients, and those who are coinfected with HBV or HCV are more vulnerable.40 Although varying degrees of drug-related liver injury have been associated with almost every antiretroviral regimen, previous reports suggest that NNRTIs tend to cause a slight increase in the cumulative incidence of hepatotoxicity with prolonged use, especially in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients.21,40,46 However, this analysis showed that liver-related AEs were uncommon with rilpivirine or efavirenz over ≥48 weeks of treatment. Moreover, most of the hepatic AEs reported were laboratory abnormalities, generally asymptomatic grade 1 or 2 increases in transaminase levels, rather than clinical hepatic AEs. These findings are similar to those of other studies on the safety of NNRTIs.32,47

The current pooled analysis of two trials has several limitations. The individual trials were not designed to compare rilpivirine with efavirenz in coinfected patients. In addition, patients entering the trials were highly selected, e.g. those with clinically significant hepatic impairment or ALT and/or AST levels five times above the upper limit of normal were excluded. As such, this subpopulation was restricted to mild-to-moderately hepatically impaired patients, and thus the proportion of HBV/HCV-coinfected patients (8.4%) was different (smaller) compared with the incidence of coinfection previously reported in Western Europe and the USA (HCV coinfection: 25%–30%; HBV coinfection: 6%–14%).1 However, treatment comparison within the study remains valid. Also, this exclusion criterion meant the safety of rilpivirine or efavirenz in patients with more advanced liver disease at baseline was not explored. The small numbers preclude: separate analyses of the HBV- and HCV-coinfected patients; further study of the effect on response and safety of other baseline risk factors; or further study of the background N(t)RTIs that have anti-HBV activity (tenofovir, lamivudine and emtricitabine). Lastly, it is beyond the scope of this analysis to determine the reasons for the differences in the virological response and tolerability profile between HBV/HCV-coinfected patients and non-coinfected patients, e.g. whether or not they are due to an intrinsic effect of the NNRTIs.

The results of the analysis suggest that hepatic AEs are more common and the response rates lower in HBV/HCV-coinfected patients than in patients with HIV who are not coinfected, when treated with rilpivirine or efavirenz. Rilpivirine demonstrated an efficacy and hepatic safety profile similar to that of efavirenz in both coinfected and non-coinfected individuals. Standard clinical monitoring is considered adequate when HBV/HCV-coinfected patients receive a HAART regimen that includes rilpivirine. Finally, clinical practice will also be guided by the extensive drug interactions study programme being conducted with rilpivirine, particularly in the light of the known drug interactions between some current ARVs and certain HCV therapies.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Janssen Pharmaceuticals. The medical writing support and assistance in coordinating and collating author contributions from Ian Woolveridge (principal writer) of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications was funded by Janssen.

Members of the ECHO and THRIVE Study Groups

ECHO

Argentina: L. Abusamra, P. Cahn, H. E. Laplume, I. Cassetti, M. Ceriotto, M. D. Martins and A. Krolewiecki; Australia: M. Bloch, J. Gold, J. Hoy and P. Martinez; Austria: A. Rieger, N. Vetter and R. Zangerle; Brazil: C. A. Da Cunha, B. Grinsztejn, J. V. Madruga, J. H. Pilotto and D. Sampaio; Canada: P. Junod, D. Kilby, A. Rachlis and S. Walmsley; Denmark: J. Gerstoft, L. Mathiesen and C. Pedersen; France: L. Cotte, P.-M. Girard, J. M. Molina, F. Raffi, D. Vittecoq, Y. Yazdanpanah and P. Yeni; Great Britain: M. Fisher, M. Nelson, C. Orkin and S. Taylor; Italy: A. Lazzarin, P. Narciso, A. Orani and S. Rusconi; Mexico: G. Amaya and G. Reyes-Teran; Netherlands: B. Rijnders; Puerto Rico: J. Santana; Portugal: F. Antunes, T. Branco, R. Sarmento, E. Castro, T. Eugenio and K. Mansinho; Romania: D. Duiculescu, L. Negrutiu and L. Prisacariu; Russia: V. Kulagin, E. Voronin and A. Yakovlev; South Africa: E. Baraldi, N. David, O. Ebrahim, E. Krantz, G. H. Latiff, D. Spencer and R. Wood; Spain: J. R. Arribas, J. Portilla Sogorb, E. Ribera and I. Santos Gil; Sweden: K. Westling; Thailand: P. Chetchotisakd, T. Sirisanthana, S. Sungkanuparph and A. Vibhagool; Taiwan: C.-C. Hung, H.-C. Lee, H.-H. Lin and W. W. Wong; and USA: H. Albrecht, N. Bellos, D. Berger, C. Brinson, B. Casanas, R. Elion, J. Feinberg, T. File, J. Flamm, C. Hicks, S. Hodder, C.-B. Hsiao, P. Kadlecik, H. Khanlou, C. Kinder, R. Liporace, C. Mayer, D. Mildvan, A. Mills, R. A. Myers, I. Nadeem, O. Osiyemi, M. Para, G. Pierone, B. Rashbaum, J. Rodriguez, M. Saag, J. Sampson, R. Samuel, M. Sension, P. Shalit, P. Tebas, W. Towner, A. Wilkin, J. Eron and D. Wohl.

THRIVE

Australia: D. Baker, R. Finlayson and N. Roth; Belgium: R. Colebunders, N. Clumeck, J.-C. Goffard, F. Van Wanzeele and E. Van Wijngaerden; Brazil: C. R. Gonsalez, M. P. Lima, F. Rangel and A. Timerman; Canada: M. Boissonnault, J. Brunetta, J. De Wet, J. Gill, K. Kasper and J. Macleod; Chile: J. Ballesteros, R. Northland and C. Perez; China: L. Hongzhou, T. Li, W. Cai, H. Wu and X. Li; Costa Rica: G. Herrera; France: F. Boue, C. Katlama and J. Reynes; Germany: K. Arastéh, S. Esser, G. Fätkenheuer, T. Lutz, R. Schmidt, D. Schuster and H.-J. Stellbrink; Great Britain: M. Johnson, E. Wilkins, I. G. Williams and A. Winston; India: N. Kumarasamy and P. Patil; Italy: A. Antinori, G. Carosi and F. Mazzotta; Mexico: J. Andrade-Villanueva and J. G. Sierra Madero; Panama: A. Canton Martinez, A. Rodriguez-French and N. Sosa; Portugal: R. Marques; Puerto Rico: C. Zorrilla; Russia: N. Dushkina, A. Pronin, O. Tsibakova and E. Vinogradova; South Africa: M. Botes, F. Conradie, J. Fourie, L. Mohapi, D. Petit and D. Steyn; Spain: B. Clotet, F. Gutierrez, D. Podzamczer and V. Soriano; Thailand: K. Ruxrungtham and W. Techasathit; and USA: L. Amarilis Lugo, R. Bolan, L. Bush, R. Corales, L. Crane, J. De Vente, M. Fischl, J. Gathe, R. Greenberg, K. Henry, D. Jayaweera, P. Kumar, J. Lalezari, J. Leider, R. Lubelchek, C. Martorell, K. Mounzer, C. Cohen, H. Olivet, R. Ortiz, F. Rhame, A. Roberts, P. Ruane, A. Scribner, S. Segal-Maurer, W. Short, L. Sloan, T. Wilkin, M. Wohlfeiler and B. Yangco.

Transparency declarations

M. N. has acted as consultant and received educational and research grants from Merck Sharpe & Dohme (MSD), GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS), Gilead Sciences, Johnson & Johnson, Janssen, Abbott Laboratories, Boehringer Ingelheim (BI), Schering-Plough, Pfizer and Roche. N. C. has participated as an expert or investigator for Abbott Laboratories, BI, Gilead Sciences, GSK, MSD, Pfizer, Roche and Janssen. C. A. da C. has received research support from BMS, Janssen, Gilead Sciences and Schering-Plough. In addition, he has served as consultant and speaker for BMS, Janssen-Cilag, Gilead Sciences, Abbott Laboratories, MSD and Roche. D. J. has been an investigator and/or scientific advisor (Review Panel or Advisory Committee) for Janssen, BMS, Gilead Sciences, BI and GSK. He has received research support from Janssen, BMS, Roche and GSK, and speaker honorarium from Janssen, BMS, Gilead Sciences, BI, Roche and GSK. He has served as a consultant for Janssen, BMS, Gilead Sciences, Roche and GSK, and has been on the Speaker's Bureau for Janssen, BMS, Gilead Sciences, BI and GSK. P. J. has received consulting fees and or grants from Abbott Laboratories, Gilead Sciences, Merck, Janssen, ViiV Healthcare and BMS. P. T. has received consulting fees from GSK, Merck and, more than 1 year since publication, Pfizer and Janssen. M. S., S. V. and K. B. are full-time employees of Janssen. M. S. owns stock in Johnson and Johnson. A. B. is a contractor for Janssen. G. A. and T. L. declare no conflicts of interest.

The authors received medical writing support and assistance in coordinating and collating author contributions from Ian Woolveridge (senior medical writer) of Gardiner-Caldwell Communications, Macclesfield, UK.

Author contributions

All authors substantially contributed to the study's conception, design and performance. Mark Nelson, Gerardo Amaya, Nathan Clumeck, Clovis Arns da Cunha, Dushyantha Jayaweera, Patrice Junod, Taisheng Li and Pablo Tebas all participated in recruiting significant numbers of patients to the trial and reported data for those patients. Marita Stevens, Annemie Buelens, Simon Vanveggel and Katia Boven all had a significant involvement in the data analyses. All authors were involved in the development of the primary manuscript, interpretation of the data, have read and approved the final version, and have met the criteria for authorship as established by the ICMJE.

Acknowledgements

Data contained in this article were presented during the 10th International Congress on Drug Therapy in HIV Infection, Glasgow, UK, 2010 (Abstract P210) and at the Seventh International Workshop on HIV and Hepatitis C Co-infection, Milan, Italy, 2011 (Abstract O_02).

We are very grateful to the patients and their families for their participation and support during the study, the ECHO and THRIVE study teams from Janssen, the study centre staff and principal investigators, and the members of the Janssen TMC278 team, in particular Guy De La Rosa, David Anderson, Eric Lefebvre, Peter Williams and Eric Wong, for their input.

References

- 1.Alter MJ. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and HIV co-infection. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl):S6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konopnicki D, Mocroft A, de Wit S, et al. Hepatitis B and HIV: prevalence, AIDS progression, response to highly active antiretroviral therapy and increased mortality in the EuroSIDA cohort. AIDS. 2005;19:593–601. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000163936.99401.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thio CL, Seaberg EC, Skolasky R, Jr, et al. HIV-1, hepatitis B virus, and risk of liver-related mortality in the Multicenter Cohort Study (MACS) Lancet. 2002;360:1921–6. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11913-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sulkowski MS. Management of hepatic complications in HIV-infected persons. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(Suppl 3):S279–93. doi: 10.1086/533414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thein HH, Yi Q, Dore GJ, et al. Natural history of hepatitis C virus infection in HIV-infected individuals and the impact of HIV in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy: a meta-analysis. AIDS. 2008;22:1979–91. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32830e6d51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matthews GV, Avihingsanon A, Lewin SR, et al. A randomized trial of combination hepatitis B therapy in HIV/HBV coinfected antiretroviral naive individuals in Thailand. Hepatology. 2008;48:1062–9. doi: 10.1002/hep.22462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peters MG, Andersen J, Lynch P, et al. Randomized controlled study of tenofovir and adefovir in chronic hepatitis B virus and HIV infection: ACTG A5127. Hepatology. 2006;44:1110–6. doi: 10.1002/hep.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Puoti M, Cozzi-Lepri A, Paraninfo G, et al. Impact of lamivudine on the risk of liver-related death in 2,041 HBsAg- and HIV-positive individuals: results from an inter-cohort analysis. Antivir Ther. 2006;11:567–74. doi: 10.1177/135965350601100509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avidan NU, Goldstein D, Rozenberg L, et al. Hepatitis C viral kinetics during treatment with peg IFN-α-2b in HIV/HCV coinfected patients as a function of baseline CD4+ T-cell counts. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52:452–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181be7249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the Use of Antiretroviral Agents in HIV-1-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Department of Health and Human Services; 10 January 2011. pp. 1–174. http://www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/ContentFiles/AdultandAdolescentGL.pdf. (21 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 11.WHO. Antiretroviral Therapy for HIV Infection in Adults and Adolescents: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach - 2010 Revision. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599764_eng.pdf. (21 September 2011, date last accessed) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson MA, Aberg JA, Cahn P, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2010 recommendations of the International AIDS Society-USA panel. JAMA. 2010;304:321–33. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aceti A, Pasquazzi C, Zechini B, et al. Hepatotoxicity development during antiretroviral therapy containing protease inhibitors in patients with HIV: the role of hepatitis B and C virus infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;29:41–8. doi: 10.1097/00042560-200201010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonfanti P, Landonio S, Ricci E, et al. Risk factors for hepatotoxicity in patients treated with highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:316–8. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200107010-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.den Brinker M, Wit FW, Wertheim-van Dillen PM, et al. Hepatitis B and C virus co-infection and the risk for hepatotoxicity of highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 2000;14:2895–902. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200012220-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Núñez M, Lana R, Mendoza JL, et al. Risk factors for severe hepatic injury after introduction of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2001;27:426–31. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200108150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saves M, Raffi F, Clevenbergh P, et al. Hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection is a risk factor for severe hepatic cytolysis after initiation of a protease inhibitor-containing antiretroviral regimen in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients. The APROCO Study Group. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3451–5. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.12.3451-3455.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL, Chaisson RE, et al. Hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in adults infected with human immunodeficiency virus and the role of hepatitis C or B virus infection. JAMA. 2000;283:74–80. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wit FW, Weverling GJ, Weel J, et al. Incidence of and risk factors for severe hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral combination therapy. J Infect Dis. 2002;186:23–31. doi: 10.1086/341084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuping G, Wei L, Yang H, et al. Impact of hepatitis C virus coinfection on HAART in HIV-infected individuals: multicentric observation cohort. J AIDS. 2010;54:137–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181cc5964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dieterich DT, Robinson PA, Love J, et al. Drug-induced liver injury associated with the use of nonnucleoside reverse-transcriptase inhibitors. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38(Suppl 2):S80–9. doi: 10.1086/381450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lucas GM, Chaisson RE, Moore RD. Comparison of initial combination antiretroviral therapy with a single protease inhibitor, ritonavir and saquinavir, or efavirenz. AIDS. 2001;15:1679–86. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200109070-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez E, Blanco JL, Arnaiz JA, et al. Hepatotoxicity in HIV-1-infected patients receiving nevirapine-containing antiretroviral therapy. AIDS. 2001;15:1261–8. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200107060-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moyle G. The emerging roles of non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors in antiretroviral therapy. Drugs. 2001;61:19–26. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peters PJ, Stringer J, McConnell MS, et al. Nevirapine-associated hepatotoxicity was not predicted by CD4 count ≥250 cells/μL among women in Zambia, Thailand and Kenya. HIV Med. 2010;11:650–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.DeJesus E, Herrera G, Teofilo E, et al. Abacavir versus zidovudine combined with lamivudine and efavirenz, for the treatment of antiretroviral-naive HIV-infected adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:1038–46. doi: 10.1086/424009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gallant JE, Staszewski S, Pozniak AL, et al. Efficacy and safety of tenofovir DF vs stavudine in combination therapy in antiretroviral-naive patients: a 3-year randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:191–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gallant JE, DeJesus E, Arribas JR, et al. Tenofovir DF, emtricitabine, and efavirenz vs. zidovudine, lamivudine, and efavirenz for HIV. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:251–60. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manfredi R, Calza L, Chiodo F. Efavirenz versus nevirapine in current clinical practice: a prospective, open-label observational study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004;35:492–502. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200404150-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Martin-Carbonero L, Núñez M, Gonzalez-Lahoz J, et al. Incidence of liver injury after beginning antiretroviral therapy with efavirenz or nevirapine. HIV Clin Trials. 2003;4:115–20. doi: 10.1310/N4VT-3E9U-4BKN-CRPW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez E, Arnaiz JA, Podzamczer D, et al. Substitution of nevirapine, efavirenz, or abacavir for protease inhibitors in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1036–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL, Mehta SH, et al. Hepatotoxicity associated with nevirapine or efavirenz-containing antiretroviral therapy: role of hepatitis C and B infections. Hepatology. 2002;35:182–9. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.van Leth F, Phanuphak P, Ruxrungtham K, et al. Comparison of first-line antiretroviral therapy with regimens including nevirapine, efavirenz, or both drugs, plus stavudine and lamivudine: a randomised open-label trial, the 2NN Study. Lancet. 2004;363:1253–63. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15997-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Law WP, Dore GJ, Duncombe CJ, et al. Risk of severe hepatotoxicity associated with antiretroviral therapy in the HIV-NAT cohort, Thailand, 1996–2001. AIDS. 2003;17:2191–9. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200310170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Viramune® (Nevirapine) Prescribing Information - January 2011. http://bidocs.boehringer-ingelheim.com/BIWebAccess/ViewServlet.ser?docBase=renetnt&folderPath=/Prescribing+Information/PIs/Viramune/Viramune.pdf. (21 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Janssen-Cilag International NV. EDURANT 25 mg Film-Coated Tablets, Summary of Product Characteristics, 2011. http://www.medicines.org.uk/EMC/medicine/25490/SPC/Edurant+25+mg/ (4 April 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Janssen, Inc. EDURANT™ (Rilpivirine) Tablets, Full Prescribing Information, 2011. http://www.edurant-info.com/sites/default/files/EDURANT-PI.pdf. (4 April 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 38.Janssen, Inc. EDURANT™ (Rilpivirine) Tablets, Product Monograph, Canada, 2011. http://webprod3.hc-sc.gc.ca/dpd-bdpp/item-iteme.do?pm-mp=00013725. (4 April 2012, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cohen C, Molina J-M, Cahn P, et al. Efficacy and safety of rilpivirine (TMC278) versus efavirenz at 48 weeks in treatment-naïve, HIV-1-infected patients: pooled results from the phase 3 double-blind, randomized ECHO and THRIVE trials. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;60:33–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31824d006e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Núñez M. Hepatotoxicity of antiretrovirals: incidence, mechanisms and management. J Hepatol. 2006;44(Suppl):S132–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Molina J-M, Cahn P, Grinsztejn B, et al. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with tenofovir and emtricitabine in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (ECHO): a phase 3 randomised double-blind active-controlled trial. Lancet. 2011;378:238–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60936-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohen CJ, Andrade-Villanueva J, Clotet B, et al. Rilpivirine versus efavirenz with two background nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors in treatment-naive adults infected with HIV-1 (THRIVE): a phase 3, randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2011;378:229–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60983-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vingerhoets J, Rimsky L, Van Eygen V, et al. Screening and baseline mutations in the TMC278 phase III trials ECHO and THRIVE: prevalence and impact on virological response (Abstract 41) Antivir Ther. 2011;16(Suppl 1):A51. doi: 10.3851/IMP2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.AIDS Clinical Trials Group. Division of AIDS Table for Grading the Severity of Adult and Pediatric Adverse Events Version 1.0, December 2004. Clarification August 2009. http://rsc.tech-res.com/safetyandpharmacovigilance/ (21 September 2011, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) Version 11.0. http://meddramsso.com. (21 September 2011, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kontorinis N, Dieterich D. Hepatotoxicity of antiretroviral therapy. AIDS Rev. 2003;5:36–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bruck S, Witte S, Brust J, et al. Hepatotoxicity in patients prescribed efavirenz or nevirapine. Eur J Med Res. 2008;13:343–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]