Brain neurons form auditory feature detector circuit for song pattern recognition in acoustically communicating crickets.

Keywords: Auditory Processing, Delay Line, Coincidence Detection, Feature Detection, Sound Pattern Recognition, Identified Neuron, Brain Circuitry, Communication Signals, Neural Computation, Fundamental Principle

Abstract

From human language to birdsong and the chirps of insects, acoustic communication is based on amplitude and frequency modulation of sound signals. Whereas frequency processing starts at the level of the hearing organs, temporal features of the sound amplitude such as rhythms or pulse rates require processing by central auditory neurons. Besides several theoretical concepts, brain circuits that detect temporal features of a sound signal are poorly understood. We focused on acoustically communicating field crickets and show how five neurons in the brain of females form an auditory feature detector circuit for the pulse pattern of the male calling song. The processing is based on a coincidence detector mechanism that selectively responds when a direct neural response and an intrinsically delayed response to the sound pulses coincide. This circuit provides the basis for auditory mate recognition in field crickets and reveals a principal mechanism of sensory processing underlying the perception of temporal patterns.

INTRODUCTION

Like Morse code, acoustic communication in lower vertebrates (1–3) and insects (3–5) is based on simple patterns of sound pulses. At the receiver side, selective response properties of feature-detecting networks in the auditory pathway allow reliable recognition of the species-specific signal (6–9). Whereas information on sound amplitude and frequency is gathered in the auditory periphery, the analysis of temporal pulse patterns requires processing by the central nervous system (5, 10, 11). Interneurons responding to specific pulse rates have been recorded in the brains of mammals (12, 13), frogs (14, 15), fish (2, 8), and insects (16, 17), but the neural mechanisms establishing their response selectivity are not yet revealed (10, 18). To explain response selectivity for pulse rates, neural processing by coincidence detection with matching delay lines has been proposed (19–22). According to this concept, the auditory response is carried forward to a coincidence detector, both directly and by a parallel delaying pathway (Fig. 1). If the pulse period of the acoustic signal matches the internal delay, the delayed response coincides with the next direct response and boosts the coincidence detector output. A feature detector that selectively responds to a specific pulse repetition rate emerges with an activation threshold above the response to single pulses.

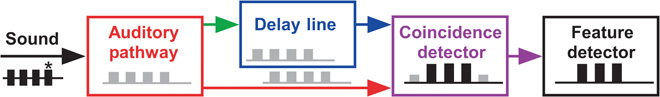

Fig. 1. Pulse period recognition by a delay line and coincidence detection mechanism.

Flow diagram based on the concept of Reiss (19) and Weber and Thorson (20) for the sequence of auditory processing; the first sound pulse entering the auditory pathway is indicated by an asterisk. See the text for detailed explanation.

Our study focused on field crickets as an invertebrate model system to investigate auditory feature detection underlying acoustic communication (7, 9, 23). In the Mediterranean field cricket (Gryllus bimaculatus), females are selectively attracted to the chirps of the male calling song, in which 3 to 5 sound pulses are repeated with a pulse period of 30 to 40 ms (17, 20). The hearing organs are located in their front legs, and auditory afferents terminate in the prothoracic ganglion. At each side of the central nervous system, auditory responses to the male song are carried forward to the brain via a single ascending interneuron, AN1 (9, 16). AN1 activates a small group of identified spiking brain neurons that is confined to the axonal projection area of the ascending interneuron in the anterior protocerebrum (17, 23). Here, we demonstrate that these neurons form a local auditory network that has the fundamental characteristics of a coincidence detector circuit. The postinhibitory rebound (PIR) properties of a newly identified nonspiking interneuron provide the required intrinsic delay matching the species-specific pulse period.

RESULTS

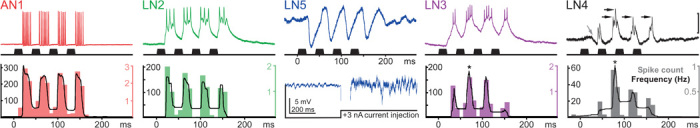

To analyze the processing in this network, we performed single-cell intracellular recordings in the anterior protocerebrum of the brain. This revealed different characteristic auditory responses of four previously identified spiking neurons (17) and of a newly identified nonspiking interneuron (Fig. 2) upon stimulation with standardized chirps of the species-specific pulse pattern. The spike activity of the ascending neuron AN1 and the local neuron LN2 reliably copies the sound pattern with a slight adaptation, typical for most sensory neurons. From the first to the fourth pulse of a chirp, the response gradually declines from 7.7 ± 1.3 spikes to 6.2 ± 0.9 spikes for AN1 (n = 70; P < 0.001; t = 13.7) and from 3.5 ± 0.6 spikes to 2.4 ± 0.6 spikes for LN2 (N = 8; P < 0.001; t = 5.7). However, the brain neurons LN3 and LN4 show properties of more complex auditory processing because both respond more strongly to the second pulse of the chirp. In LN3, the excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) and spike response to the first pulse are always lower than the response to the second pulse (1.8 ± 0.6 spikes versus 3.1 ± 0.7 spikes; P < 0.001; t = 10.7; N = 12). LN4 responds to the first sound pulse with an inhibition and a subsequent depolarization that rarely elicits a spike, whereas the second pulse evokes a substantially larger EPSP that reliably triggers spike activity (0.1 ± 0.1 spikes/pulse versus 1.5 ± 0.5 spikes/pulse; P < 0.001; t = 8.4; N = 9). The membrane potential of the newly identified interneuron LN5 alternates between inhibition and subsequent depolarization in response to each sound pulse. We did not record any spikes in LN5 (N = 18), nor could we evoke spiking by depolarizing current injection (tested in five animals). We therefore conclude that this is a nonspiking interneuron (24). The inhibitory response to the first pulse starts after 25.2 ± 1.4 ms (N = 18), and after 35.5 ± 2.1 ms, it reaches a maximum hyperpolarization of −4 to −9 mV in different recordings. Subsequently, the membrane depolarizes to 3 to 5 mV above the resting potential. The inhibitory response to the following sound pulse truncates the depolarization, and only in response to the last pulse of a chirp does the depolarization slowly decay. In the following text, we provide experimental evidence that, according to the signal-processing mechanisms outlined in Fig. 1, in the cricket brain, a delay line is formed by neurons LN2 and LN5 and a coincidence detector and a feature detector are implemented by neurons LN3 and LN4.

Fig. 2. Typical responses of auditory neurons to the pulse pattern of calling song chirps.

(Top) Intracellular recordings (upper trace) and acoustic stimulation (lower trace); AN1 and LN2-LN4 are spiking neurons and LN5 is a nonspiking neuron. In the LN4 recording, gray arrow indicates initial inhibition and black arrows indicate spikes. Scale bar, 35 mV (AN1); 25 mV (LN2); 5 mV (LN5); 20 mV (LN3); 10 mV (LN4). (Bottom) The diagrams of spiking neurons show poststimulus time histograms (colored bar charts) and average spike frequency (black line) in response to artificial standard chirps (n = 50 each) with a sound frequency of 4.8 kHz. AN1 and LN2 copy the sound pattern, with the strongest spike response to the first pulse of the chirp. LN3 and LN4 respond most strongly to the second pulse (asterisks). Depolarizing current injection fails to elicit spiking in LN5, which confirms that it is a nonspiking interneuron. Neuron recordings were obtained from different specimens and are aligned to the start of the sound stimulus.

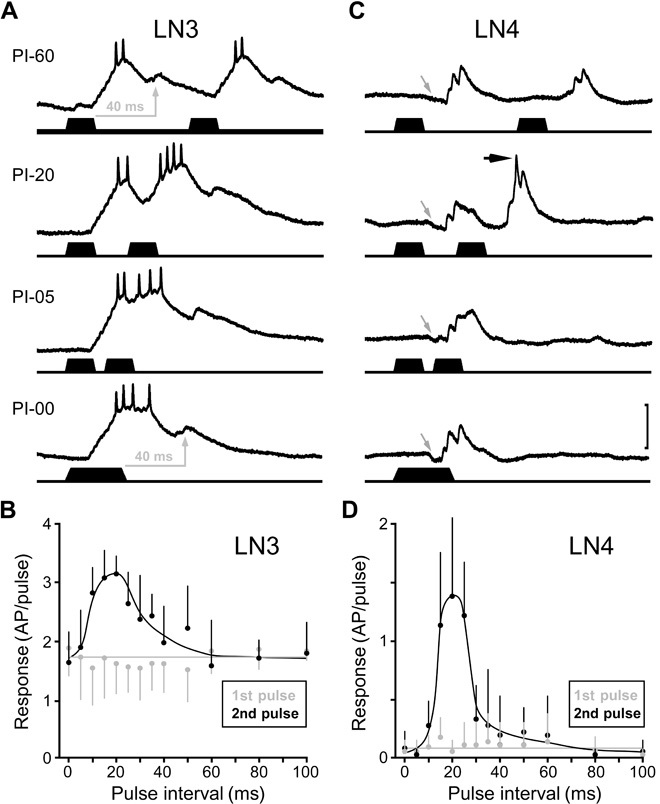

We tested the temporal tuning of neurons LN3 and LN4 by challenging them with pairs of 20-ms sound pulses with varying pulse intervals. At a pulse interval of 60 ms, LN3 generated two similar and separate responses (Fig. 3, A and B). For each pulse, the membrane potential showed an initial depolarization driving a response of 1.8 ± 0.6 spikes/pulse (N = 7 each) and a delayed subthreshold depolarization. The initial depolarization results from a sequence of temporally summing small EPSPs, whereas the delayed depolarization appears to be a single EPSP with a larger amplitude and longer time course (fig. S1). For all intervals above 35 ms, each sound pulse elicited a similar response of 1 to 2 spikes (first versus second: P > 0.2 for each interval tested; N = 7). With a 20-ms interval, however, the delayed depolarization to the first sound pulse coincides with the initial depolarization elicited by the second pulse. As a consequence, the response significantly increases from 1.6 ± 0.5 spikes for the first pulse to 3.2 ± 0.3 spikes for the second pulse (first versus second: P < 0.001; t = 6.5; N = 7). For intervals below 10 ms, both responses merged, and a delayed depolarization only occurred after the second pulse. In contrast with the initial depolarization, the delayed depolarization was strictly coupled to the sound offset (see arrows in Fig. 3A) with a constant latency of 43.5 ± 2.4 ms (N = 4) for the depolarization maximum. The LN3 response to the second pulse was strongest, with 3.0 ± 0.5 spikes/pulse (N = 7) for intervals of 15 to 25 ms, corresponding to the pulse interval range of the species-specific song. On the basis of these data, LN3 qualifies as a coincidence detector; its band-pass sensitivity for interval duration is established by the summation of direct and delayed excitatory inputs, coupled to the sound pulse onset and offset, respectively.

Fig. 3. Pulse interval sensitivity of LN3 and pulse interval selectivity of LN4.

(A and C) Intracellular recordings (upper traces) of synaptic and spike activity in LN3 (A) and LN4 (C) upon stimulation (lower traces) with pairs of sound pulses with 60-, 20-, 5-, and 0-ms pulse intervals (PI). In both neurons, the EPSP and spike response to the second pulse were increased at a pulse interval of 20 ms; recordings were obtained from different specimens. Scale bar, 20 mV (LN3); 10 mV (LN4). (A) Gray arrows indicate delayed depolarization of LN3 with the peak always occurring 40 to 45 ms after the offset of the sound pulse. (C) For LN4, gray arrows indicate initial inhibition and black arrow indicates spiking. (B and D) Quantitative analysis of systematic paired-pulse stimulation. The spike responses of LN3 (B) (N = 7) and LN4 (D) (N = 4) to the first pulse are interval-independent; their spike responses to the second pulse are significantly increased for the 15- to 25-ms pulse intervals.

In LN4 (Fig. 3, C and D), individual sound pulses elicited an initial inhibition followed by a depolarization that rarely exceeded spiking threshold (Fig. 3C, gray arrows indicate inhibition). However, a second pulse after 20 ms caused a suprathreshold depolarization (Fig. 3C, black arrow indicates spike), leading to the generation of 1.4 ± 0.7 spikes/pulse (N = 4). When the second sound pulse is presented after less than 10 ms, or when the interval is zero (40 ms pulse), both responses merge but stay below the spiking threshold. Quantitative analysis of LN4 spike activity shows a distinct band-pass selectivity for pulse intervals of 15 to 25 ms. Because LN4 does not receive a delayed excitation, we conclude that it is not a primary coincidence detector. LN4 spikes only toward pulses presented at the interval of the species-specific song pattern, and we therefore refer to this neuron as a feature detector. In comparison to the band-pass sensitivity of LN3, the additional inhibition of LN4 establishes a response selectivity that closely matches the band-pass tuning of the phonotactic behavior (16, 17). LN3 and LN4 show characteristic response patterns as a consequence of the outlined processing (Fig. 1). When stimulated with two appropriately timed sound pulses, the coincidence detector neuron LN3 will respond to both pulses, but its response toward the second pulse will be stronger. The feature detector neuron LN4 responds only to the second pulse.

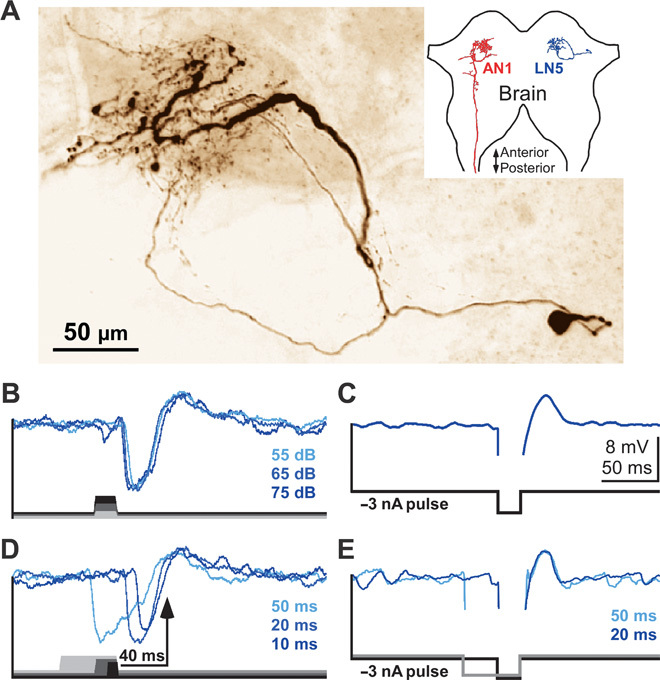

The coincidence detector in this circuit (Fig. 1) requires a delayed input after about 40 ms, corresponding to the species-specific pulse period, as can be seen in the delayed depolarization in LN3 recordings. We identified the nonspiking brain neuron LN5 by intracellular recordings in 18 animals. The neuron has a ventrolateral cell body, and together with the previously identified spiking neurons (17), its neurite branches in immediate vicinity to the axonal arborization of AN1 (Fig. 4A and figs. S2 and S3). Upon acoustic stimulation, LN5 generated a suitably delayed depolarization by PIR. Each single sound pulse elicited in LN5 a strong inhibition followed by a depolarization (Fig. 4B and fig. S4). Injection of hyperpolarizing current pulses revealed that the depolarization of LN5 was due to PIR and was not a delayed excitatory input from the auditory network (Fig. 4C). When the neuron was released from a 20-ms hyperpolarization, it also generated a rebound depolarization of 3 to 5 mV. The PIR amplitude was independent of the stimulus duration within the range of 10 to 50 ms, was independent of sound amplitude in the range of 50 to 80 dB sound pressure level (SPL) (Fig. 4B and fig. S5), and peaked 43.0 ± 2.9 ms (N = 18) after sound offset. PIR was always coupled to the release from membrane hyperpolarization, evoked by either sound-induced inhibition or intracellular current injection (Fig. 4, D and E). Thus, during acoustic stimulation, LN5 generates an excitatory response with a delay corresponding to the species-specific pulse period of the calling song. Crucially, the PIR in LN5 closely matches the timing of the delayed excitation in the coincidence detector LN3, and both are coupled to the end of a sound pulse. This points to LN5 forwarding the delayed excitation to LN3, and therefore, we refer to LN5 as the delay-line neuron of the network (Fig. 1).

Fig. 4. Nonspiking interneuron LN5 generates a delayed excitatory response by PIR depolarization.

(A) Confocal image of LN5. Neurite arborizations are in the immediate vicinity of AN1 terminals in the brain (see also figs. S2 and S3 for more details). In the inset, only the left AN1 and the right LN5 are depicted to indicate the location of the neurons in the brain. (B) Intensity-invariant responses to 20-ms sound pulses of 55, 65, and 75 dB SPL (signal averages, n = 5). (C) Rebound depolarization after a 20-ms injection of −3 nA intracellular current (signal average, n = 20). (D and E) For sound and current pulses of different duration, the rebound is always time-coupled to the sound offset (D) or the release from hyperpolarization (E) (signal averages, n = 5).

Simultaneous intracellular recordings of these brain neurons to directly characterize their synaptic connectivity were not feasible. However, the flow of neural activity based on the response latencies to sound pulses reveals the circuitry of the network (Fig. 5A, figs. S6 and S7, and table S1). AN1 is the only ascending interneuron that provides auditory activity to the brain in response to the calling song (9, 16); from the start of a sound pulse, its spike response takes 20.4 ± 2.0 ms (N = 70) to arrive at the brain. The local neurons LN2 and LN3 show the earliest auditory response. Response latencies and frequency tuning of LN2 and LN3 provide evidence that spikes of AN1 directly drive EPSPs in both neurons (Fig. 5B, fig. S6, and table S1). LN3 generates a sequence of gradually summing EPSPs starting after 20.5 ± 1.6 ms (N = 12) and occurring with a timing that matches the spike pattern of AN1 (fig. S1). At 75 dB SPL, for example, summation of 5 to 6 EPSPs is required to elicit LN3 spiking with a latency of 34.2 ± 3.5 ms (N = 12). In LN2, EPSPs also start after 20.6 ± 1.8 ms; however, this neuron spikes after 22.6 ± 2.0 ms (N = 8). The large amplitude of individual EPSPs indicates that summing of two EPSPs driven by AN1 spikes is sufficient to trigger spiking in LN2. Although AN1 activity linearly increases with sound intensity, LN2 activity is intensity-independent above 50 dB SPL (fig. S5). This is in accord with models for intensity-independent responses proposing strong synapses that drive the postsynaptic neuron to saturation for all stimulus amplitudes (25). In the feature detector neuron LN4 and the delay-line neuron LN5, the first auditory responses are inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. In comparison to the excitation in LN2 and LN3, the inhibition in LN4 and LN5 occurred with a slightly longer latency of 24.9 ± 2.9 ms (N = 9) and 25.2 ± 1.4 ms (N = 18), respectively. It is unlikely that AN1 directly drives excitatory as well as inhibitory responses in postsynaptic neurons. The inhibition in LN4 and LN5 closely follows the spike activity of LN2 and is also sound intensity–independent, indicating that LN2 inhibits LN4 and LN5 (Fig. 5, A and B, figs. S5 and S6, and table S1). In the nonspiking neuron LN5, this inhibition triggers a PIR that drives the delayed depolarization in LN3. When a second pulse is presented after the species-specific pulse interval of 20 ms, the response of the coincidence detector LN3 is substantially enhanced (Fig. 5C); the AN1 input now coincides with the delayed PIR excitation from LN5 that is generated in response to the first pulse (blue arrows in Fig. 5, B and C). In response to the first and second pulses, LN3 spikes after 34.2 ± 3.5 ms and 28.6 ± 2.1 ms (N = 12) and EPSPs in LN4 follow the LN3 spikes with a constant 3-ms delay at 37.4 ± 3.1 ms and 31.6 ± 2.7 ms (N = 9), respectively. Thus, besides initial inhibition via LN2, the feature detector LN4 receives excitation via LN3. The enhanced response of the coincidence detector LN3 to the second pulse provides stronger excitation to the feature detector LN4, which now overcomes the inhibition and spikes (black arrow in Fig. 5C). Together, the response properties of the auditory brain neurons and the sequential timing of their activity reveal a network architecture in which AN1 provides a direct pathway and LN2 and LN5 establish a delayed pathway to the coincidence detector LN3, and the feature detector LN4 integrates inhibition from LN2 and excitation from LN3 (Fig. 5A). Any other connectivity between the neurons would not be in accord with the experimental data.

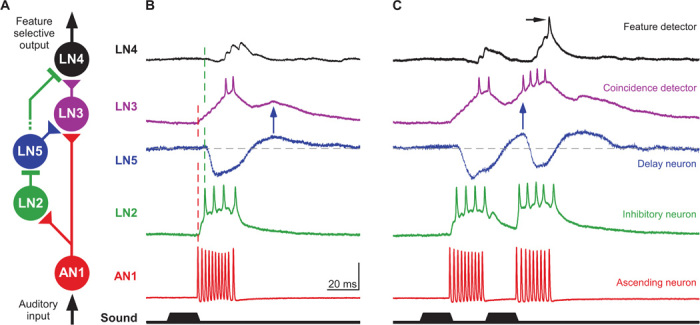

Fig. 5. Circuitry and processing mechanism of the auditory feature detector network.

(A) Circuitry based on the response properties and the latency of neural responses. Triangular and rectangular symbols indicate excitatory and inhibitory synapses, respectively. (B and C) The typical responses of the five auditory neurons are aligned to the onset of a single (B) and a pair (C) of sound pulses with a 20-ms pulse interval. (B) AN1 spiking is immediately followed by a fast depolarization of LN2 and a gradually increasing depolarization in LN3 (first dashed line). Inhibition in LN4 and LN5 follows the spike activity of LN2 with short latency (second dashed line). The timing of the PIR depolarization in LN5 corresponds to the delayed EPSP in LN3 (blue arrow). The spike activity in LN3 precedes the excitatory response in LN4. (C) The LN3 response is enhanced for a second sound pulse presented after an interval of 20 ms as the direct (via AN1) and delayed (via LN5) excitatory inputs coincide. Driven by a stronger LN3 activity, LN4 now overcomes its inhibition and spikes (black arrow). Scale bar, 35 mV (AN1); 25 mV (LN2); 5 mV (LN5); 20 mV (LN3); 10 mV (LN4). Neural response patterns were recorded in different specimens and are aligned to the start of the sound stimulus.

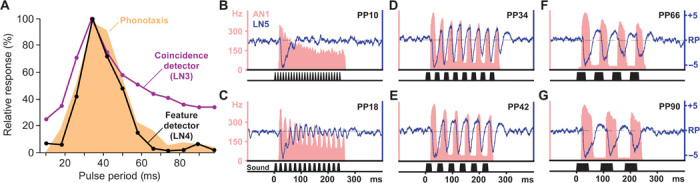

To relate the tuning mechanisms of the circuit to the band-pass tuning of the phonotactic behavior, we analyzed the neuronal responses to artificial chirps with different pulse periods (Fig. 6 and fig. S7), a standard test to characterize the phonotactic behavior (16, 17, 26). When tested for pulse periods ranging from 10 to 98 ms (PP10 to PP98), the phonotactic response exhibited clear band-pass selectivity with the maximum around PP34. This is closely reflected by the spike responses of the coincidence detector LN3 and the feature detector LN4 (Fig. 6A). The response of the coincidence detector LN3 depended on the relative timing and amplitude of the direct input from AN1 and the delayed excitation from LN5. For recordings subsequently obtained in the same animals, we therefore analyzed the spike activity of AN1 and the changes in the membrane potential of LN5 in response to chirps that either elicit strong phonotaxis (Fig. 6, D and E) or are phonotactically unattractive (Fig. 6, B, C, F, and G). For attractive pulse periods from PP34 to PP42 (17- to 21-ms intervals), the depolarization of LN5 and the spike response in AN1 are in phase and occur at the same time beginning from the second pulse onward (Fig. 6, D and E). For unattractive pulse periods of PP66 to PP98 (33- to 49-ms intervals), the AN1 response and PIR of LN5 drift out of phase (Fig. 6, F and G), and therefore, direct and delayed excitatory inputs do not add up in the coincidence detector LN3. This mechanism establishes a high-pass filter. At pulse periods below PP34 (interval shorter than 17 ms), the PIR in LN5 elicited by a sound pulse becomes increasingly reduced as it is truncated and diminished by the inhibition in response to the subsequent pulse. Additionally, AN1 activity increasingly habituates and fails to copy the fast pulse pattern in its spike activity, thereby reducing the direct input to the coincidence detector and, indirectly, the phasic inhibition of LN5 that is essential to drive its PIR (Fig. 6, B and C). These properties establish a very effective low-pass filter. Therefore, two different processing mechanisms define the band-pass selectivity of the circuit for pulse periods.

Fig. 6. The tuning of LN3 and LN4 results from the timing of AN1 and LN5 excitation and matches the phonotactic behavior.

(A) Response tuning of the coincidence detector LN3 (N = 10), the feature detector LN4 (N = 5), and the phonotactic behavior (N = 14) toward chirps with different pulse periods but constant sound energy (26). (B to G) Instantaneous spike rate of AN1 (red area; average n = 10) and changes in the membrane potential of LN5 (blue trace; signal average, n = 5) for chirps from the same paradigm as used in (A). Both interneurons were recorded subsequently in the same animal, independent of phonotaxis tests. See fig. S7 for m3ore details.

DISCUSSION

The key to understanding the neural basis of recognition processes is the identification of mechanisms that cause “high-order” brain neurons to selectively respond to the same stimuli that trigger a specific behavior (6, 27). Our data demonstrate how a network of only five interneurons functions as an auditory feature detector circuit in the cricket brain. The final neuron selectively responds to the temporal pulse pattern of the male calling song with a band-pass tuning matching the female phonotactic behavior. Previous suggestions for the mechanism of song pattern recognition in crickets include cross-correlation with an internal template (7, 28), matched high- and low-pass filtering for pulse rates (16), and processing by a combination of Gabor filters (9). Our experimental data strongly support the early concept of coincidence detection between a direct and an intrinsically delayed sensory response (19, 20). The combination of cellular and network properties and the flow of neural activity in response to sound pulses reveal the operation of this feature detection circuit. Spiking and nonspiking neurons, excitatory and inhibitory processing, membrane integration times, and the PIR mechanism all contribute to the properties in this small network. A diminutive response to an individual stimulus and a pronounced response to an appropriately timed subsequent one are obvious signs for a coincidence detection mechanism with a delay line. In the cricket brain, LN3 exhibits band-pass sensitivity for the species-specific pulse rate and shows explicit coincidence detector characteristics, whereas the downstream feature detector neuron LN4 shows a highly selective response to the species-specific pulse pattern. According to the original concept (Fig. 1), the feature detector would also respond to integer multiples of the preferred pulse rate (19–21). However, corresponding phonotactic responses have never been observed in these crickets (16, 17, 26). For low pulse rates, the activities of the direct (AN1) and delayed (LN5) pathways are out of phase and establish a high-pass filter as predicted. At high pulse rates, a combination of factors diminishes the PIR depolarization in LN5 and provides an effective low-pass filter. This makes the actual neural circuit even more specific than predicted by the original coincidence detection with delay line concept. It also shows that band-pass filtering occurs, but in a different way from the previously proposed concept (16). The resulting pattern selectivity closely matches the phonotactic behavior (Fig. 6).

In the field cricket G. bimaculatus, an auditory response with a delay matching the species-specific pulse period of about 40 ms is required for processing of the communication signal. Because adaptations in axonal path length are limited to provide microsecond delays (29, 30), the PIR depolarization produced by the nonspiking interneuron LN5 is an expedient solution to generate the long delays required (31). Because the PIR in LN5 is coupled to the end of sound pulses, it determines the pulse interval selectivity of the network and may be regarded as an internal “predictor” or “template” for the next pulse to occur. Modifications of the membrane conductance that set the time constants in LN5 are likely to adjust the phonotactic selectivity in cricket species that use different pulse rates. However, for effective communication, the sender and the receiver need to be attuned to the same signal (1, 4, 32), and in crickets, the generation and recognition of the song pattern are genetically coupled (33, 34). Delayed excitation by PIR is not only crucial for song pattern recognition but also essential in the singing pattern generating network (35). To ensure concomitant changes of time constants in the networks for signal generation and recognition, a coupling at the level of membrane proteins, such as hyperpolarization-activated ion channels that are controlled by the same genes, seems plausible.

PIR has been widely implicated in precisely timed auditory processing (31, 36, 37). In the mouse superior olivary nucleus, neurons display a pronounced PIR underlying their temporal selectivity for periodic low-frequency amplitude modulations (13). Sound-evoked PIR in midbrain neurons of the fish Pollimyrus has been proposed for detecting the rate of repetitive click signals (8, 22). Differently tuned delay line and coincidence detector circuits can be arranged for auditory processing in chronotopical maps (11, 38), such as delay-sensitive maps in echolocating bats (39). The overall network design of the auditory feature detector circuit for pulse patterns in the cricket brain is also very similar to that of the elementary motion detector circuit in the visual pathway (40, 41). The striking similarities between these systems point to a fundamental circuitry layout underlying the temporal processing of sequential events, which is shared among different sensory modalities in very different nervous systems (21, 22, 31, 38, 41). The proposed circuitry of the network in the cricket brain emerges from response latencies and activity patterns of the auditory neurons, and future experiments with simultaneous electrophysiological or optical recordings will be required to directly characterize the synaptic connections. Intracellular double recordings of these small neurons are technically not feasible yet, but would be of particular interest to further investigate the connections of AN1 and LN5 to LN3, as this may provide new insight on how the response selectivity of a small brain neuron can result from temporal correlation based on nonlinear integration of different synaptic inputs (42–44). Furthermore, computational modeling studies based on the framework of the proposed circuit may allow new predictions for the operation of the network that could then be tested in neurophysiological, neuropharmacological, and behavioral experiments (45).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experiments were performed with mature female field crickets (G. bimaculatus de Geer) as previously described (17, 46). Female larvae were isolated as last instars and were reared in a separate room to ensure physical and acoustic isolation from males. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (20° to 25°C) and complied with the principles of Laboratory Animal Care. During intracellular recordings, the animals were free to walk on a trackball (47), only tethered at the head. Neuronal signals were amplified and recorded using standard techniques (17, 48). Recordings were monitored with an analog oscilloscope (Tektronix 5440) and simultaneously digitized (Micro1401 mk II, CED) for storage on a PC hard drive. Data were analyzed off-line using customized Neurolab (49) and Spike2 (CED) software. Mean values and SDs are given for normally distributed metric data (D’Agostino and Pearson omnibus normality test; Prism 5.0, GraphPad). If not stated otherwise, paired Student’s t test was used to calculate the significance levels for data comparison. N indicates the number of animals and n indicates the number of analyzed events.

Sharp microelectrodes were pulled (DMZ-Universal Puller, Zeitz-Instruments) from borosilicate glass capillaries (GC100F-10, Harvard Apparatus Ltd.). Electrode depth in the brain was controlled with a Mitutoyo absolute digimatic indicator (ID-C125MB, Mitutoyo Corporation). For intracellular labeling, microelectrode tips were loaded with 5% Lucifer yellow (Sigma-Aldrich) or 0.5% Alexa Fluor 568 Hydrazide (Molecular Probes), and the dye was injected with 2- to 5-nA hyperpolarizing current; the shaft of the microelectrodes was filled with 0.5 M LiCl or 1 M potassium acetate, respectively. Brains were processed following standard protocols for fluorescent dyes, and images were captured with either a conventional epifluorescence microscope (Axiophot, Zeiss) or a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica SP5). The ascending auditory neuron AN1 and the local spiking brain neurons LN2, LN3, and LN4 have been previously described as TH1-AC1, B-LI2, B-LI3/B-LC3, and B-LI4, respectively (17). Together with the newly described nonspiking neuron LN5, they were identified according to their structure and characteristic response patterns (see Fig. 2).

Sound stimuli were generated with Cool Edit Pro 2000 software (Syntrillium; now Adobe Audition software, Adobe Systems). Signals from a PC audio board were amplified with a custom-made amplifier and presented by speakers (Sinus Live NEO 13 S, Conrad Electronics). If not stated otherwise, sound stimuli had a carrier frequency of 4.8 kHz and an intensity of 75 dB SPL relative to 20 μPa. The SPL of acoustic stimulation was calibrated at the position of the cricket to an accuracy of 1 dB (1/2-inch microphone type 4191 and measuring amplifier type 2610, Brüel & Kjær). Standard artificial chirps of the species-specific pulse pattern had 4 pulses (20 ms duration, 20 ms interval) and were repeated during a 500-ms chirp period. Paired pulses of 20 ms duration were also presented while the pulse interval was increased from 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 50, 60, 80, to 100 ms. We also tested with a well-established pulse-period paradigm of “constant sound energy” chirps (16, 17, 26, 46). Frequency tuning of the neurons was tested with pure-tone sound pulses of 20 ms duration (with 1 ms rising and falling ramps; 80 ms silence between pulses) at sound frequencies of 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 10, 12, 14, 16, 18, and 20 kHz. For each frequency, the sound amplitude was systematically increased from 35 to 80 dB SPL by steps of 5 dB to measure the response threshold of the neuron.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to M. Burrows, R. Patterson, B. Sengupta, and M. Hennig for constructive discussions and helpful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. Funding: Financial support for the study was provided by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/J01835X/1) and the Isaac Newton Trust (Trinity College, Cambridge). Author contributions: B.H., K.K., and S.S. designed the experiments. S.S. and K.K. collected and analyzed the data. S.S. prepared the figures. S.S. and B.H. drafted, edited, and revised the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests. Data and materials availability: The data for this study is available at www.repository.cam.ac.uk.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/8/e1500325/DC1

Table S1. Summary of key properties of the six synaptic connections in the proposed circuit.

Fig. S1. Processing of AN1 spike activity by LN2 and LN3.

Fig. S2. Confocal whole-mount scans of AN1 and LN3.

Fig. S3. Confocal whole-mount scans of an LN5 neuron labeled with Lucifer yellow.

Fig. S4. LN5 responses to the standard chirp pattern.

Fig. S5. Sound intensity–invariant responses of delay-line neurons LN2 and LN5.

Fig. S6. Mean threshold curves for spiking responses of AN1, AN2, LN2, and LN3 and for synaptic responses of LN3, LN4, and LN5.

Fig. S7. AN1 spike activity and LN5 PIR.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Doherty J. A., Gerhardt H. C., Hybrid tree frogs: Vocalizations of males and selective phonotaxis of females. Science 220, 1078–1080 (1983). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bass A. H., McKibben J. R., Neural mechanisms and behaviors for acoustic communication in teleost fish. Prog. Neurobiol. 69, 1–26 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.H. C. Gerhardt, F. Huber, Acoustic Communication in Insects and Anurans (University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 2002). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alexander R. D., Evolutionary change in cricket acoustical communication. Evolution 16, 443–467 (1962). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pollack G. S., Analysis of temporal patterns of communication signals. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11, 734–738 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.T. H. Bullock, The problem of recognition in an analyzer made of neurons, in Sensory Communication, W. A. Rosenblith, Ed. (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1961), pp. 717–724. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hoy R. R., Acoustic communication in crickets: A model system for the study of feature detection. Fed. Proc. 37, 2316–2323 (1978). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crawford J. D., Feature-detecting auditory neurons in the brain of a sound-producing fish. J. Comp. Physiol. A 180, 439–450 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ronacher B., Hennig R. M., Clemens J., Computational principles underlying recognition of acoustic signals in grasshoppers and crickets. J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 61–71 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mizrahi A., Shalev A., Nelken I., Single neuron and population coding of natural sounds in auditory cortex. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 24, 103–110 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hildebrandt K. J., Neural maps in insect versus vertebrate auditory systems. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 24, 82–87 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schulze H., Langner G., Periodicity coding in the primary auditory cortex of the Mongolian gerbil (Meriones unguiculatus): Two different coding strategies for pitch and rhythm? J. Comp. Physiol. A 181, 651–663 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Felix R. A. II, Fridberger A., Leijon S., Berrebi A. S., Magnusson A. K., Sound rhythms are encoded by postinhibitory rebound spiking in the superior paraolivary nucleus. J. Neurosci. 31, 12566–12578 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rose G. J., Leary C. J., Edwards C. J., Interval-counting neurons in the anuran auditory midbrain: Factors underlying diversity of interval tuning. J. Comp. Physiol. A 197, 97–108 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott T. M., Christensen-Dalsgaard J., Kelley D. B., Temporally selective processing of communication signals by auditory midbrain neurons. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 1620–1632 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schildberger K., Temporal selectivity of identified auditory neurons in the cricket brain. J. Comp. Physiol. A 155, 171–185 (1984). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kostarakos K., Hedwig B., Calling song recognition in female crickets: Temporal tuning of identified brain neurons matches behavior. J. Neurosci. 32, 9601–9612 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goel A., Buonomano D. V., Timing as an intrinsic property of neural networks: Evidence from in vivo and in vitro experiments. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 369, 20120460 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.R. F. Reiss, A theory of resonant networks, in Neural Theory and Modeling, R. F. Reiss, Ed. (Stanford Univ. Press, Palo Alto, CA, 1964), pp. 105–137. [Google Scholar]

- 20.T. Weber, J. Thorson, Phonotactic behavior of walking crickets, in Cricket Behavior and Neurobiology, F. Huber, T. E. Moore, W. Loher, Eds. (Cornell Univ. Press, Ithaca, NY, 1989), pp. 310–339. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedel P., Bürck M., van Hemmen J. L., Neuronal identification of acoustic signal periodicity. Biol. Cybern. 97, 247–260 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Large E. W., Crawford J. D., Auditory temporal computation: Interval selectivity based on post-inhibitory rebound. J. Comput. Neurosci. 13, 125–142 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kostarakos K., Hedwig B., Pattern recognition in field crickets: Concepts and neural evidence. J. Comp. Physiol. A 201, 73–85 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.M. Burrows, Nonspiking local interneurons, in The Neurobiology of an Insect Brain (Oxford Univ. Press, Oxford, 1996), pp. 84–100. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hooper S. L., Buchman E., Hobbs K. H., A computational role for slow conductances: Single-neuron models that measure duration. Nat. Neurosci. 5, 552–556 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thorson J., Weber T., Huber F., Auditory behavior of the cricket. II. Simplicity of calling-song recognition in Gryllus, and anomalous phonotaxis at abnormal carrier frequencies. J. Comp. Physiol. A 146, 361–378 (1982). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Konishi M., Deciphering the brain’s codes. Neural Comput. 3, 1–18 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hennig R. M., Acoustic feature extraction by cross-correlation in crickets? J. Comp. Physiol. A Neuroethol. Sens. Neural Behav. Physiol. 189, 589–598 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jeffress L. A., A place theory of sound localization. J. Comp. Physiol. A 41, 35–39 (1948). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Carr C. E., Konishi M., Axonal delay lines for time measurement in the owl’s brainstem. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 8311–8315 (1988). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carr C. E., Processing of temporal information in the brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 16, 223–243 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.J. W. Bradbury, S. L. Vehrenkamp, Principles of Animal Communication (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA, 1998). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hoy R. R., Hahn J., Paul R. C., Hybrid cricket auditory behavior: Evidence for genetic coupling in animal communication. Science 195, 82–84 (1977). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaw K. L., Lesnick S. C., Genomic linkage of male song and female acoustic preference QTL underlying a rapid species radiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 9737–9742 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schöneich S., Hedwig B., Cellular basis for singing motor pattern generation in the field cricket (Gryllus bimaculatus DeGeer). Brain Behav. 2, 707–725 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koch U., Grothe B., Hyperpolarization-activated current (Ih) in the inferior colliculus: Distribution and contribution to temporal processing. J. Neurophysiol. 90, 3679–3687 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kopp-Scheinpflug C., Tozer A. J. B., Robinson S. W., Tempel B. L., Hennig M. H., Forsythe I. D., The sound of silence: Ionic mechanisms encoding sound termination. Neuron 71, 911–925 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mauk M. D., Buonomano D. V., The neural basis of temporal processing. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 27, 307–340 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kössl M., Hechavarria J. C., Voss C., Macias S., Mora E. C., Vater M., Neural maps for target range in the auditory cortex of echolocating bats. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 24, 68–75 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.B. Hassenstein, W. Reichardt, Functional structure of a mechanism of perception of optical movement, in Proceedings of the First International Congress on Cybernetics, Namar, 1956, pp. 797–801. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Borst A., In search of the holy grail of fly motion vision. Eur. J. Neurosci. 40, 3285–3293 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peña J. L., Konishi M., Robustness of multiplicative processes in auditory spatial tuning. J. Neurosci. 24, 8907–8910 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gabbiani F., Krapp H. G., Hatsopoulos N., Mo C.-H., Koch C., Laurent G., Multiplication and stimulus invariance in a looming-sensitive neuron. J. Physiol. Paris 98, 19–34 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clemens J., Hennig R. M., Computational principles underlying the recognition of acoustic signals in insects. J. Comput. Neurosci. 35, 75–85 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hennig R. M., Heller K.-G., Clemens J., Time and timing in the acoustic recognition system of crickets. Front. Physiol. 5, 286 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zorović M., Hedwig B., Processing of species-specific auditory patterns in the cricket brain by ascending, local and descending neurons during standing and walking. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 2181–2194 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hedwig B., Poulet J. F. A., Mechanisms underlying phonotactic steering in the cricket Gryllus bimaculatus revealed with a fast trackball system. J. Exp. Biol. 208, 915–927 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schöneich S., Hedwig B., Corollary discharge inhibition of wind-sensitive cercal giant interneurons in the singing field cricket. J. Neurophysiol. 113, 390–399 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hedwig B., Knepper M., NEUROLAB, a comprehensive program for the analysis of neurophysiological and behavioural data. J. Neurosci. Methods 45, 135–148 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/8/e1500325/DC1

Table S1. Summary of key properties of the six synaptic connections in the proposed circuit.

Fig. S1. Processing of AN1 spike activity by LN2 and LN3.

Fig. S2. Confocal whole-mount scans of AN1 and LN3.

Fig. S3. Confocal whole-mount scans of an LN5 neuron labeled with Lucifer yellow.

Fig. S4. LN5 responses to the standard chirp pattern.

Fig. S5. Sound intensity–invariant responses of delay-line neurons LN2 and LN5.

Fig. S6. Mean threshold curves for spiking responses of AN1, AN2, LN2, and LN3 and for synaptic responses of LN3, LN4, and LN5.

Fig. S7. AN1 spike activity and LN5 PIR.