A method for creating electrocatalyst films extends the scope of usable substrates to non-conducting and three-dimensional electrodes.

Keywords: electrocatalysis, solar fuels

Abstract

Amorphous metal-based films lacking long-range atomic order have found utility in applications ranging from electronics applications to heterogeneous catalysis. Notwithstanding, there is a limited set of fabrication methods available for making amorphous films, particularly in the absence of a conducting substrate. We introduce herein a scalable preparative method for accessing oxidized and reduced phases of amorphous films that involves the efficient decomposition of molecular precursors, including simple metal salts, by exposure to near-infrared (NIR) radiation. The NIR-driven decomposition process provides sufficient localized heating to trigger the liberation of the ligand from solution-deposited precursors on substrates, but insufficient thermal energy to form crystalline phases. This method provides access to state-of-the-art electrocatalyst films, as demonstrated herein for the electrolysis of water, and extends the scope of usable substrates to include nonconducting and temperature-sensitive platforms.

INTRODUCTION

Amorphous metal-based films are pervasive in a myriad of applications [for example, transistors (1, 2) and flexible electronics (3)], including schemes that involve the electrocatalytic oxidation of water into clean hydrogen fuels. Indeed, there is a growing body of evidence showing that amorphous films mediate the oxygen evolution reaction (OER; Eq. 1) (4–8) and hydrogen evolution reaction (HER; Eq. 2) (9, 10) more efficiently than do crystalline phases of the same compositions. These findings are particularly important in the context of efficiently storing electricity produced from intermittent and variable renewable energy sources (for example, sunlight and wind) as high-density fuels (for example, hydrogen) (11, 12).

| 1 |

| 2 |

Most amorphous metal oxide films reported in the literature are formed by electrodeposition (4–7), sputtering (13), thermal decomposition (3, 14), or ultraviolet (UV) light–driven decomposition (8) of metal precursors. Although films prepared by these methods can demonstrate state-of-the-art electrocatalytic OER activities (15–20), the syntheses are not necessarily amenable to scalable manufacture because of sensitivities to metal work functions, reaction media, or prohibitively expensive precursors. Consequently, accessing specific compositions of amorphous metal oxides for commercial applications is not trivial, particularly when complex metal compositions are desired (3, 8). Moreover, the isolation of amorphous metals is substantially more challenging because single-element metallic films typically require sophisticated protocols (21).

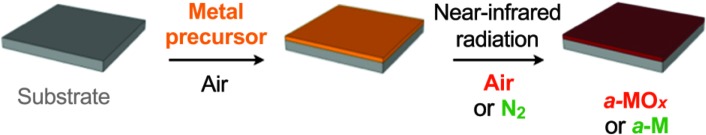

We report here a previously untested method for generating amorphous metal-based films, in the reduced and oxidized phases, that relies merely on the exposure of transition metal salts [for example, MClx and M(NO3)x] to near-infrared (NIR) radiation under inert and aerobic environments, respectively (Fig. 1). This method is distinctive from the UV-driven photochemical decomposition of metal complexes (8) in that it is ultimately a thermally driven process and therefore does not require photoactive precursors. Notwithstanding, this NIR-driven decomposition (NIRDD) process furnishes amorphous metal oxide films that display properties commensurate with films prepared by more complex methods and precursors, yet is amenable to curing techniques widely used in large-scale manufacturing processes, including roll-to-roll processing (22, 23). We therefore contend that NIRDD represents a significant advance toward a solar fuel economy, which will invariably require electrocatalysts to efficiently mediate small-molecule transformations. Moreover, NIRDD provides access to reduced phases of amorphous films using moderate experimental conditions. We demonstrate the broad use of this fabrication technique herein by examining the formation of amorphous oxide films containing metals of relevance to the OER reaction [for example, iron (7, 8), iridium (18, 24), manganese (6, 25), nickel (7, 8, 26), and copper (27, 28)]. We also provide evidence that NIRDD, which works despite substrate temperatures not reaching 200°C (fig. S1), can also be extended to substrates that are nonconducting and sensitive to temperature and UV radiation by documenting amorphous metal oxide film formation interfaced with Nafion.

Fig. 1. Scheme of NIRDD.

The NIRDD of a metal precursor (for example, FeCl3) on a substrate [for example, fluorine-doped tin oxide–coated glass (FTO)] leads to the formation of amorphous metal oxide (a-MOx) and reduced metal (a-M) films under air and nitrogen, respectively.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

The formation of amorphous metal oxide films upon exposure of metal salts to NIR radiation was confirmed by placing FeCl3 spin-cast on FTO, FeCl3/FTO, under a 175-W NIR lamp for 120 min in an aerobic environment. The color change from yellow to light brown upon irradiation supported the formation of iron oxide (UV-vis spectra are provided in fig. S2), whereas the absence of reflections in the powder x-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns indicated the amorphous nature of the material (figs. S3 and S4). (A signature Bragg reflection of hematite is apparent at 2θ = 35.9° only after annealing the same film in air for 1 hour at 600°C.) The electrochemical behavior of this amorphous film, a-FeOx, in aqueous media was also consistent with previous accounts of amorphous iron oxide (Fig. 2 and Table 1). These films demonstrated oxidative stability at a current density of 10 mA/cm2 over a 2-hour period (fig. S5). An extensive electrochemical analysis indicated that a-FeOx could be readily produced from other iron compounds [for example, Fe(NO3)3 and Fe(eh)3; eh = 2-ethylhexanoate] (fig. S6) and that the NIRDD method translated effectively to other metals: Films of a-IrOx, a-NiOx, and a-MnOx were also formed when the corresponding metal compounds were subjected to NIR radiation (figs. S7 and S8). The electrocatalytic properties of a-IrOx in 1 M H2SO4 (fig. S8) are consonant with literature values, as are those for a-NiOx and a-MnOx in alkaline conditions (Table 1).

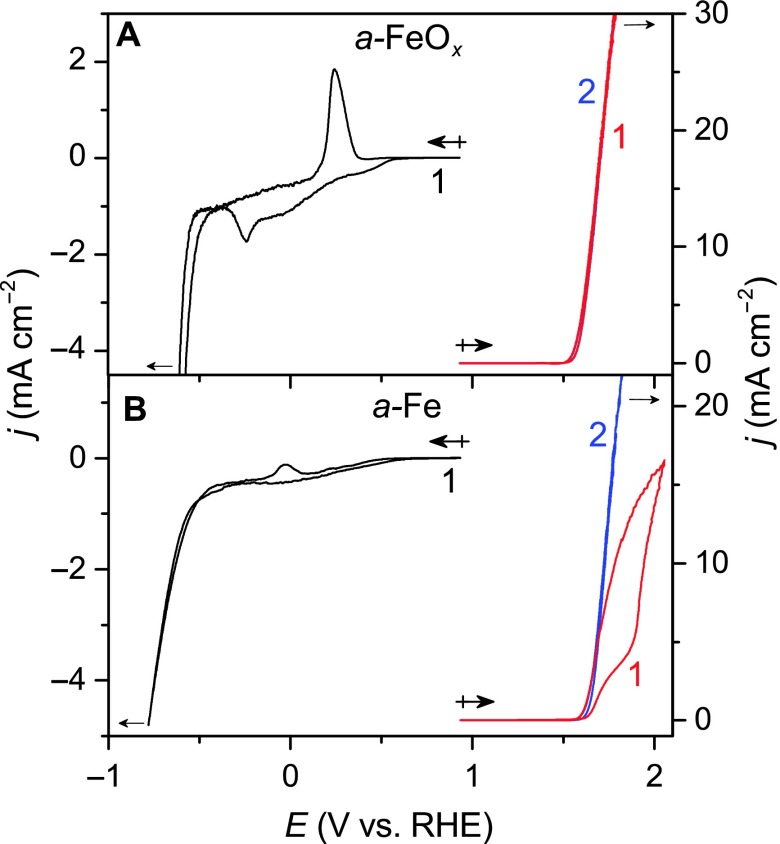

Fig. 2. Cyclic voltammograms for a-FeOx and a-Fe.

(A and B) Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of (A) a-FeOx and (B) a-Fe on FTO. Values indicate the sequence of the cycles that were recorded. (A) The oxidative sweep of a-FeOx leads to a sharp rise in current coincident with catalytic water oxidation, and subsequent cycles led to superimposable traces. (B) The oxidative sweep for a-Fe featured a markedly different current profile for the first cycle; however, subsequent cycles indicated that a-Fe was converted to a-FeOx upon oxidation on the basis of the superimposable scans. The differences in the reductive behavior were more stark, and the cathodic peak at −0.25 V for (A) a-FeOx was not detected for (B) a-Fe before HER catalysis, indicating a more reduced form of iron for (B). Experimental conditions: counter electrode = Pt mesh; reference electrode = Ag/AgCl, KCl (sat’d); scan rate = 10 mV s−1; electrolyte = 0.1 M KOH (aq).

Table 1. Benchmarked OER activities of a-MOX films.

All potentials in this article are expressed versus a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE).

| Sample* |

Onset η (V versus RHE) |

Tafel slope (mV dec−1) |

η10 mA/cm2 (V)† | |

| This work | Literature | |||

| a-FeOx | 0.33 | 38 | 0.24‡ | 0.40‡ (16) |

| a-NiOx | 0.21 | 62 | 0.36 | 0.36 (15) |

| a-Fe2Ni3Ox | 0.19 | 34 | 0.33 | 0.35§ (15) |

| a-MnOx | 0.22 | — | 0.43‡ | 0.51‡ (16) |

| a-IrOx¶ | 0.10 | 45 | 0.26 | 0.26 (15) |

*Ox is broadly defined as oxo/oxyl/hydroxo.

†Overpotential required to reach 10 mA/cm2, unless otherwise indicated, without correcting for mass transport.

‡Overpotential required to reach 1 mA/cm2; this value may be affected by stability issues at this pH. A Tafel slope value is not provided due to film instability under steady-state conditions.

§Corresponds to FeNiOx.

¶Recorded at pH 0; all other data in table recorded at pH 13.

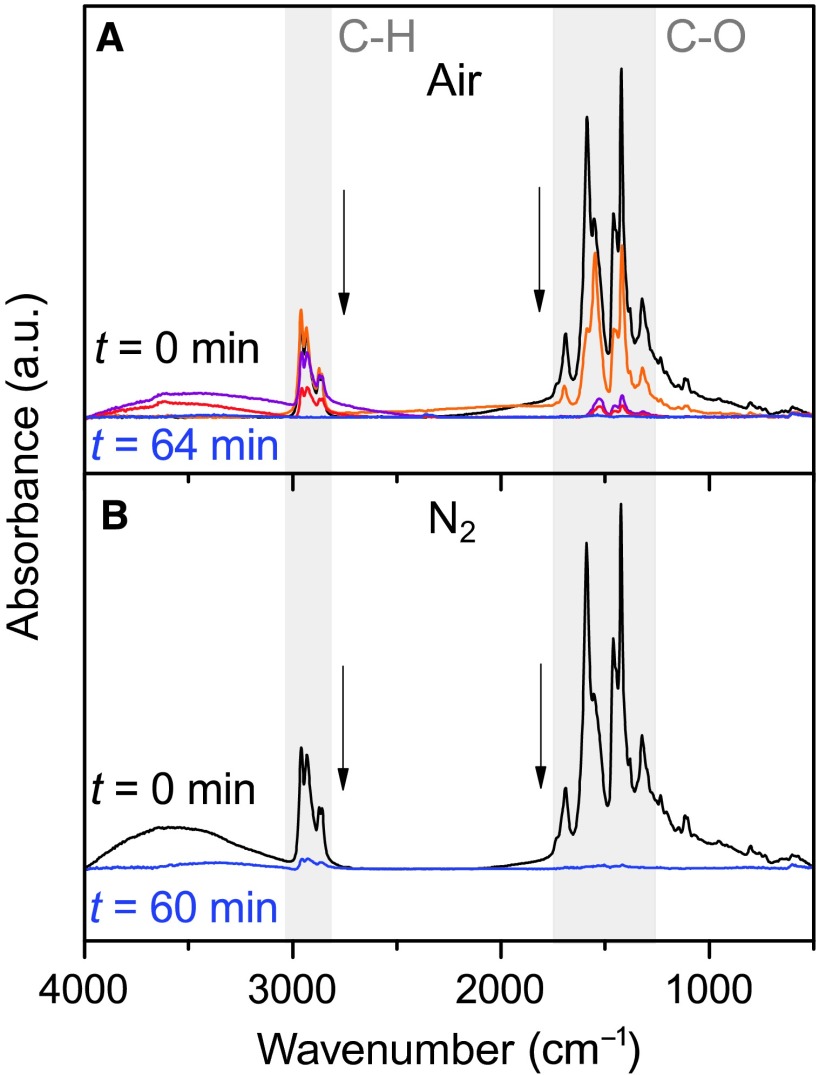

The discovery that NIRDD could drive a-MOx formation was not expected given the low absorptivities of the films at λ > 600 nm (fig. S2). We therefore contend that the efficacy of the process is due to localized heating of the film rather than a photochemical effect. This assessment is validated by the observations that: (i) substrates do not exceed 200°C under our experimental conditions (fig. S1); (ii) bulk samples of FeCl3 do not decompose to a mass corresponding to Fe2O3 until >300°C (figs. S9 and S10); (iii) samples of precursors on FTO exposed to 1 hour of constant irradiation yielded complete decomposition, whereas six successive 10-min segments of exposure separated by 5-min periods in the dark did not; and (iv) films of precursors on FTO did not show the same rates of decomposition when placed in an oven set at 200°C (fig. S11). The temporal resolution of the NIRDD process was evaluated by tracking the formation of a-FeOx during the NIR irradiation of Fe(eh)3, which contains reporter ligands that can be tracked by Fourier transform IR (FTIR) spectroscopy (17, 29), and indicated complete ligand loss within 1 hour in both air and N2 (Fig. 3). The absorption spectra (fig. S2), lack of powder XRD reflections (figs. S3 and S4), and electrochemical data (Table 1) collectively support the assignment of the as-prepared films as a-FeOx. Films of a-MOx (M = Ir, Ni, Mn) derived from Ir(acac)3 (acac = acetylacetonate), Ni(eh)2, or Mn(eh)2, were each formed quantitatively within 4 hours of irradiation (fig. S12).

Fig. 3. FTIR spectra for thin films of Fe(eh)3.

(A and B) FTIR spectra for thin films of Fe(eh)3 on FTO upon exposure to NIR radiation for (A) 0 min (black) and 4, 16, 32, and 64 min (blue) in air, and (B) 0 min (black) and 60 min (blue) under nitrogen. Arrows indicate trends in the intensities of the C-H and C-O vibrational modes of 2-ethylhexanoate (8). a.u., arbitrary units.

The formation of a-FeOx from FeCl3 signaled that oxygen was derived from the aerobic environment, thus raising the possibility that reduced forms of the films could be accessed merely by carrying out NIRDD in an inert atmosphere. This hypothesis was tested by irradiating a film of FeCl3 on FTO under nitrogen, which yielded a light gray film, denoted a-Fe, that did not produce any Bragg reflections (figs. S3 and S4). Moreover, the electrochemistry of a-Fe on FTO in 0.1 M KOH(aq) was consistent with a lower average iron valency than that of a-FeOx (Fig. 2). An oxidative sweep of a-FeOx leads to a sharp rise in current at 1.55 V coincident with catalytic OER (Fig. 2A), and subsequent cycles over the 1.0- to 1.8-V range led to superimposable traces. The oxidative sweep for a-Fe featured a markedly different current profile (Fig. 2B); however, subsequent cycles indicated that a-Fe was converted to a-FeOx upon oxidation in aqueous media on the basis of the superimposable scans. The differences in the reductive behavior were more stark because the cathodic peak at −0.25 V for a-FeOx was not detected for a-Fe before HER catalysis at ca. −0.50 V. The two films could be interconverted: Holding a-FeOx at −0.68 V for 10 min yields a color change that matches that of a-Fe (gray), whereas maintaining a-Fe at 1.92 V for 10 min drives a color change toward that of a-FeOx (brown).

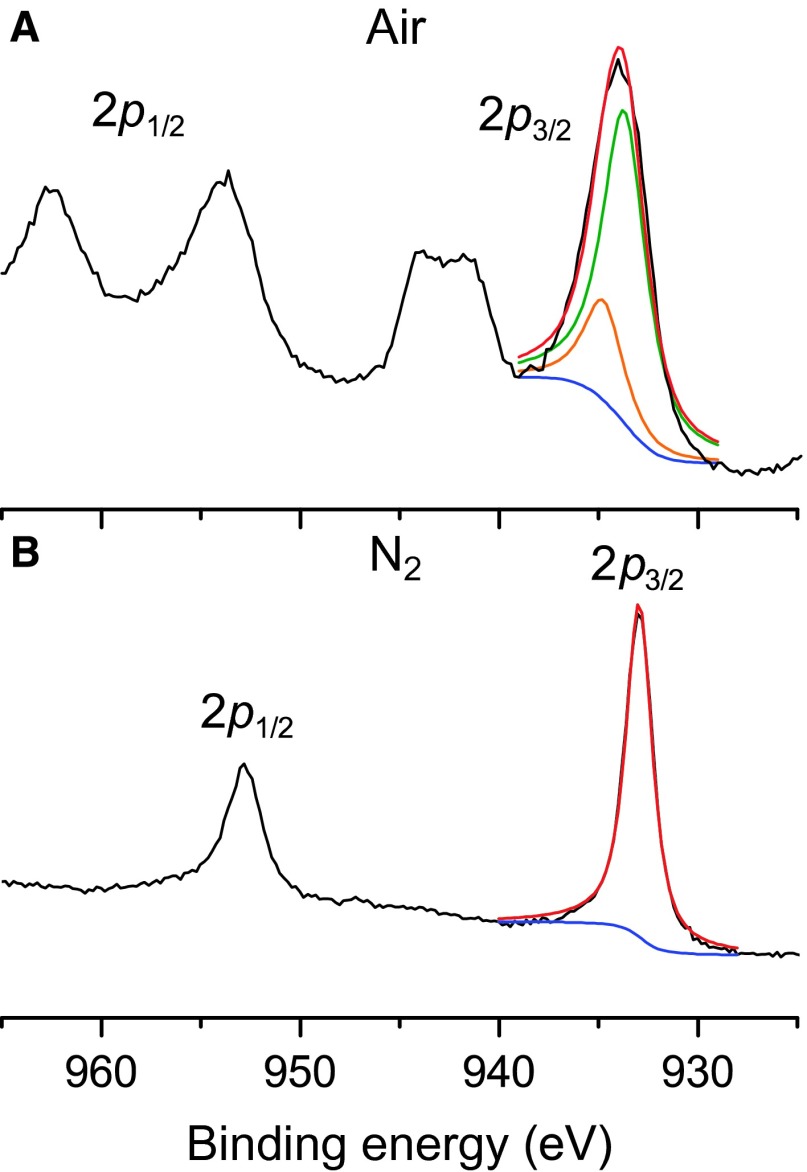

Evidence for the oxidized and reduced forms of the films formed under aerobic and nitrogen environments, respectively, is further supported by the different absorption (fig. S2) and x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; figs. S13 and S14) data. The XPS data for a-FeOx contain a signature iron(III) satellite signal at 719 eV that is not observed for a-Fe, and an iron 2p3/2 envelope that could be accurately modeled using peak parameters corresponding to Fe2O3 (30). The 2p3/2 envelope of a-Fe was fit to a combination of iron(III), iron(II), and iron(0), where the zero valency was implicated by the low-energy shoulder. Although these results confirm that a-Fe exists in a more reduced form, the high susceptibility of the films to areal oxidation prevented confirmation that elemental iron was being formed in exclusivity during the NIRDD process. We therefore analyzed surrogate films of a-CuOx and a-Cu prepared by applying the NIRDD process to Cu(eh)2 on FTO under air and nitrogen, respectively, in view of elemental copper oxidizing less readily to Cu2O and, in turn, CuO (31). XPS data recorded on these samples did indeed yield different spectroscopic signatures (Fig. 4 and fig. S15): The copper 2p3/2 envelope for a-CuOx showed a mixture of CuO and Cu(OH)2, whereas the same envelope for a-Cu shows a single peak corresponding to zero- or mono-valent copper sites. The Cu LMM peak indicated the presence of Cu2O (fig. S15), possibly due to aerial oxidation.Visible inspection of the samples prepared by NIRDD in an inert atmosphere indicated a color consistent with elemental copper (fig. S16), with XRD measurements ruling out formation of crystalline domains (fig. S17), lending credence to the samples existing in a reduced form, and potentially metallic phase, when prepared under nitrogen.

Fig. 4. XPS spectra of the copper 2p3/2 region.

(A and B) Fitting of the copper 2p3/2 region of XPS recorded on thin films of Cu(eh)2 on FTO after being subjected to the NIRDD process under (A) air and (B) nitrogen, respectively. Sums of the fitting components are indicated (red traces). Fitting of the data used center-of-gravity peaks for (A) Cu(O) (green) and Cu(OH)2 (orange), and (B) Cu(I)/Cu(0) (green). Signature copper(II) satellite peaks present in (A), but not in (B), confirm a more reduced form of the film when prepared under nitrogen. The computed baselines are indicated in blue.

Mixed-metal oxides are known to exhibit superior electrocatalytic behavior in basic media, which prompted us to synthesize the binary solid, a-Fe2Ni3Ox, by subjecting a mixture of iron precursors [for example, Fe(eh)3, FeCl3, or Fe(NO3)3] and nickel precursors [Ni(eh)2, NiCl2, or Ni(NO3)2] (mol Fe/mol Ni 2:3) spin-cast on FTO to the NIRDD process (fig. S18). The resultant films were amorphous according to powder XRD measurements (fig. S19), and the energy-dispersive x-ray spectroscopy (EDX) measurements recorded on different regions of the films confirmed uniform metal distributions across the substrates (table S1). The electrochemical behavior, including OER catalytic activity, also matches films of similar compositions prepared by other methods (fig. S20A and Table 1), including the absence of an oxidative peak at Ep ~ 1.45 V that is present in pure phases of NiOx (7).

Intrigued by the potential to access amorphous metal alloys, we set out to prepare the binary film a-Fe2Ni3 in the same manner as a-Fe2Ni3Ox, but under nitrogen. The electrocatalytic behavior of the films indicated a more reduced phase compared to that of a-Fe2Ni3Ox (fig. S20B). The film contained a uniform distribution of metals within the solid (table S1). Although the film was found not to be a state-of-the-art HER electrocatalyst, it is superior to pure phases of a-Fe and a-Ni, thus highlighting that metal cooperativity with other metal combinations may unearth superior catalysts in future studies (7, 17, 32).

Finally, we tested the viability of this synthetic method for situations where the substrate is nonconducting or sensitive to high temperatures (for example, interfacial layers in solar cells and carbon-based substrates). Proof-of-principle experiments of relevance to electrolysis were designed where an 180-μm-thick film of Nafion was coated with Ir(acac)3 and subjected to the NIRDD process. The exclusive formation of amorphous IrOx interfaced with the Nafion was found within 120 min of irradiation, with no damage to the membrane according to electrochemical and FTIR data (figs. S21 and S22). These results show that NIRDD may have the potential to efficiently coat three-dimensional substrates which may prove to be particularly important in contemporary electrolyzers.

CONCLUSIONS

Amorphous metal-based films can be prepared by exposing metal salts (for example, FeCl3) to NIR radiation. This NIRDD process also appears to provide facile access to more reduced phases of the films by avoiding the presence of oxygen during the irradiation process. This method presents the opportunity to prepare films on various substrates, and offers the ability to manufacture state-of-the-art electrocatalysts and other thin-film applications using infrastructure related to those used in curing processes currently used in industry (22, 23). Moreover, the NIRDD method provides strikingly easy access to complex metal compositions in the amorphous phase, and offers a much broader substrate scope than is available to other widely used methods.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Iron(III) 2-ethylhexanoate [Fe(eh)3, 50% (w/w) in mineral spirits], iridium(III) acetylacetonate [Ir(acac)3), nickel(II) 2-ethylhexanoate (Ni(eh)2, 78% (w/w) in 2-ethylhexanoic acid], manganese(III) 2-ethylhexanoate [Mn(eh)3, 40% (w/w) in 2-ethylhexanoic acid], and copper(II) 2-ethylhexanoate [Cu(eh)2] were purchased from Strem Chemicals. Nafion N117 proton exchange membranes (177.8 μm thick) were purchased from Ion Power; ferric chloride (98%) anhydrous (FeCl3) was purchased from Aldrich; iron(III) nitrate nonahydrate [Fe(NO3)3·9H2O], nickel nitrate hexahydrate [Ni(NO3)2·6H2O], and nickel chloride hexahydrate (NiCl2·6H2O) were purchased from Fischer Scientific. All reagents were used without further purification.

Film syntheses

a-FeOx on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.58 g of Fe(eh)3 (0.60 mmol) was added 1.07 g of hexanes (12.4 mmol). The solutions were then spin-cast onto FTO (or glass) at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, Fe(eh)3/FTO [or Fe(eh)3/glass], was left under a NIR lamp for 30 min. The following conditions for this NIRDD process were used for each experiment unless otherwise stated: the samples were placed underneath a Phillips 175-W NIR lamp, where the bottom of the lamp was positioned 2 cm above the substrate that was set on an aluminum foil surface to dissipate the heat; the face of the active film was positioned toward the lamp. We caution that unoptimized spacing of the lamp may lead to sufficiently high temperatures to yield crystalline phases. Alternative methods: Films were also prepared from FeCl3 (0.24 g) or Fe(NO3)3 (0.11 g) in deionized water (2 g), which were spin-cast on FTO to form FeCl3/FTO and Fe(NO3)3/FTO, respectively, and subjected to the NIRDD process described above to form a-FeOx. Samples prepared on glass were prepared using the same protocol as those prepared on FTO.

a-Fe on FTO (or glass). The films were prepared following the same protocol as a-FeOx, except the subsequent photolysis step being carried out in an MBRAUN LABmaster 130 glove box filled with nitrogen.

a-FeOx–annealed. Films of a-FeOx on FTO were annealed in a furnace at 600°C for 60 min.

a-Fe–annealed. Films of a-Fe on FTO were annealed for 60 min on a hot plate set at 600°C inside the glove box. The temperature of the hot plate was confirmed with a Fluke 52 thermocouple.

a-IrOx on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.09 g of Ir(acac)3 (0.3 mmol) was added 1.48 g of chloroform. The solution was spin-cast onto the substrates (glass or FTO) at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, Ir(acac)3/FTO, was subjected to the NIRDD process for 2 hours to ensure that the reaction was completed.

a-NiOx on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.27 g of Ni(eh)2 (0.61 mmol) was added 1.26 g of hexanes (14.6 mmol). The solutions were then spin-cast onto the substrates (glass or FTO) at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, Ni(eh)2/FTO, was subjected to the NIRDD process until the reaction was complete (~60 min). Alternative methods: Films could also be prepared from NiCl2 (0.17 g) or Ni(NO3)2 (0.14 g) in deionized water (2 g), which were spin-cast on FTO to form NiCl2/FTO and Ni(NO3)3/FTO, respectively, and then subjected to the NIRDD process to form a-NiOx on FTO (~30 min).

a-MnOx on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.55 g of Mn(eh)3 (0.64 mmol) was added 1.06 g of hexanes (12.3 mmol). The solutions were then spin-cast onto FTO at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, Mn(eh)3/FTO, was then subjected to the NIRDD process to form a-MnOx on FTO (~30 min).

a-CuOx on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.21 g of Cu(eh)2 (0.65 mmol) was added 1.62 g of ethanol (35.2 mmol). The solutions were then spin-cast onto FTO at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, Cu(eh)2/FTO, was then subjected to the NIRDD process to form a-CuOx on FTO (~30 min).

a-Fe2Ni3Ox on FTO (or glass). To a 20-ml beaker containing 0.23 g of Fe(eh)3 (0.24 mmol) and 0.16 g of Ni(eh)2 (0.36 mmol) was added 1.28 g of hexanes (14.9 mmol). The mixture was spin-cast onto FTO at 3000 rpm for 1 min. The resultant film, FeNi(eh)/FTO, was then subjected to the NIRDD process to form a-Fe2Ni3Ox on FTO (~30 min). Alternative methods: Films could also be prepared from a solution of NiCl2 (0.088 g) [or Ni(NO3)2 (0.105 g)] and FeCl3 (0.039 g) [or Fe(NO3)3 (0.097 g)] in deionized water (2 g) spin-cast on FTO and subjected to the NIRDD process as described above to form a-Fe2Ni3Ox.

a-Fe2Ni3 on FTO (or glass). Films of a-Fe2Ni3 on FTO were prepared in the same fashion as a-Fe2Ni3Ox, but the photolysis step was carried out in a glove box.

a-IrOx/membrane. Nafion membranes were cut into squares with geometric surface areas of 6.25 cm2 and then submerged in a bath of 3% (w/w) H2O2 stirring at 800 rpm for ~5 min. The membranes were then left to stand in a bath of stirring 0.5 M H2SO4 at 150°C for 60 min. The membranes were dehydrated in a vacuum oven (room temperature, 0.8 atm) for at least 5 hours. Excess acid was removed before dehydration with compressed nitrogen. A solution containing 0.004 g of Ir(acac)3 (0.009 mmol) in 0.9 ml of chloroform was then spray-coated on the surface of the dehydrated Nafion to form Ir(acac)3/membrane. The resultant film was then subjected to the NIRDD process to form a-IrOx/membrane (~120 min).

Physical methods

Electrochemical measurements were performed on a C-H Instruments Workstation 660D potentiostat. The Ag/AgCl (sat. KCl) reference electrode (Eref) was calibrated regularly against a 1 mM aqueous K3[Fe(CN)6] solution. Cyclic voltammograms were acquired at a scan rate of 10 mV s−1 unless otherwise indicated. All potentials were corrected for uncompensated resistance (Ru) and are reported relative to the reversible hydrogen electrode (versus RHE), ERHE = E + Eref + 0.059(pH) − iRu. Tafel plots were acquired through staircase voltammetry (10-mV steps, 50-s intervals for the final 25 s sampled). Chronopotentiometric experiments were held at 10 mA/cm2 for 7200 s. For the metal oxide and metal films on FTO, all experiments were carried out using 0.1 M KOH as an electrolyte, unless otherwise noted, in a standard three-compartment electrochemical cell. A Luggin capillary connects the reference and working electrodes, whereas a porous glass frit connects the working electrode to the platinum mesh counter electrode. All experiments involving Nafion were carried out in 0.5 M H2SO4. Membranes were hydrated in 0.2 M H2SO4 before electrochemical experiments. Measurements were performed in a customized three-electrode test cell using the above Ag/AgCl reference electrode. All potentials were corrected for Ru. The membrane electrode assembly was prepared by mechanically pressing a platinum mesh counter electrode (Aldrich), the prepared Nafion membrane, and a Toray carbon paper gas diffusion layer (Ion Power) between two Ti plate electrodes (McMaster-Carr). No aggregation was induced on the test cell besides that from evolved gaseous products. FTIR spectroscopy was recorded on a Bruker alpha spectrometer with a transmission accessory. Thin films were prepared as described above, the disappearance of the vibrations associated with the ligand were followed during photolysis. Powder XRD data were recorded with a Bruker D8 Advance diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation. Data were collected between 2θ angles of 5° and 90° with a step size of 0.04°. The step time was 0.6 s unless otherwise indicated. Thermogravimetric analysis and differential scanning calorimetry (TGA/DSC) measurements were collected simultaneously with a PerkinElmer Simultaneous Thermal Analyzer (STA) 6000. These measurements were carried out under both air and N2 at a flow rate of 20 ml min−1. Starting from a temperature of 50°C, the temperature was ramped up (10°C min−1) until 100°C, where it was held for 1 min. It was then ramped at 10°C min−1 until a final temperature of 500°C was reached and held for an additional minute. For constant temperature measurements, the temperature was ramped up (10°C min−1) until 200°C, where it was held for 60 min. UV-vis absorption spectroscopy on fresh and on metal oxide films was performed using a PerkinElmer Lambda 35 UV/Vis spectrometer with a solid sample holder accessory. Baseline scans were performed with clean glass. The films examined were prepared from 0.3 M precursor solutions of 1 to 5. XPS measurements were collected on a Leybold MAX200 spectrometer using Al Kα radiation. The pass energy used for the survey scan was 192 eV, whereas for the narrow scan it was 48 eV. Scanning electron microscopy and EDX measurements were carried out on an FEI Helios NanoLab 650 dual beam scanning electron microscope with an EDAX Pegasus system with EDS detector. The magnification was set to ×2000, the accelerating voltage was set to 2.0 keV, the current was set to 51 nA, and the working distance was 9 mm.

The temperature of the substrates was tracked with a Fluke 52 thermocouple attached to a multimeter. For the FTO measurements, constant contact of the tip of the detector was maintained throughout the experiment. For the thermocouple measurements, the tip of the detector was dipped in Fe(eh)3. The substrate and thermocouple were placed 2 cm from the lamp. Temperature values were recorded every 5 min.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for High-Throughput Phenogenomics for the use of the Helios NanoLab scanning electron microscope. Funding: We thank the Canada Foundation for Innovation, Canada Research Chairs, NSERC CREATE Sustainable Synthesis, and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for financial support. Author contributions: C.P.B. proposed the concept, designed the experiments, and supervised the project. D.A.S., K.E.D., and J.R.H. carried out experimental work. Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1400215/DC1

Fig. S1. Temperature profiles of substrates under the NIR lamp.

Fig. S2. UV-vis absorption spectra on amorphous films.

Fig. S3. Diffractograms of a-FeOx and a-Fe on FTO.

Fig. S4. Diffractograms of a-FeOx on glass.

Fig. S5. Chronoamperometric measurements of a-FeOx.

Fig. S6. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-FeOx.

Fig. S7. Diffractograms of thin films of a-IrOx, a-NiOx, and a-MnOx.

Fig. S8. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-IrOx, a-NiOx, and a-MnOx.

Fig. S9. TGA and DSC profiles for FeCl3 and Fe(eh)3.

Fig. S10. TGA and DSC profiles for FeCl3 and Fe(eh)3.

Fig. S11. FTIR spectra of independent samples of Fe(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S12. FTIR spectra of thin films of Ir(acac)3/FTO, Ni(eh)2/FTO, and Mn(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S13. X-ray photoelectron spectra for a-FeOx and a-Fe on FTO.

Fig. S14. X-ray photoelectron spectra detailing the Fe 2p3/2 region.

Fig. S15. XPS data for a-CuOx and a-Cu on FTO.

Fig. S16. Images of solid copper samples.

Fig. S17. Diffractograms of a-CuOx and a-Cu.

Fig. S18. FTIR spectra of Fe2Ni3(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S19. Diffractograms on a-Fe2Ni3Ox and a-Fe2Ni3.

Fig. S20. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-Fe2Ni3Ox and a-Fe2Ni3.

Fig. S21. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-IrOx/membrane.

Fig. S22. FTIR spectra of Ir(acac)3/membrane.

Table S1. Elemental analysis of amorphous metal oxide films determined by EDX.

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Nomura K., Ohta H., Takagi A., Kamiya T., Hirano M., Hosono H., Room-temperature fabrication of transparent flexible thin-film transistors using amorphous oxide semiconductors. Nature 432, 488–492 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim Y.-H., Heo J.-S., Kim T.-H., Park S., Yoon M.-H., Kim J., Oh M. S., Yi G.-R., Noh Y.-Y., Park S. K., Flexible metal-oxide devices made by room-temperature photochemical activation of sol–gel films. Nature 489, 128–132 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim M. G., Kanatzidis M. G., Facchetti A., Marks T. J., Low-temperature fabrication of high-performance metal oxide thin-film electronics via combustion processing. Nat. Mater. 10, 382–388 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kanan M. W., Nocera D. G., In situ formation of an oxygen-evolving catalyst in neutral water containing phosphate and Co2+. Science 321, 1072–1075 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhong D. K., Sun J., Inumaru H., Gamelin D. R., Solar water oxidation by composite catalyst/α-Fe2O3 photoanodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6086–6087 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zaharieva I., Najafpour M. M., Wiechen M., Haumann M., Kurz P., Dau H., Synthetic manganese–calcium oxides mimic the water-oxidizing complex of photosynthesis functionally and structurally. Energy Environ. Sci. 4, 2400–2408 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trotochaud L., Young S. L., Ranney J. K., Boettcher S. W., Nickel–iron oxyhydroxide oxygen-evolution electrocatalysts: The role of intentional and incidental iron incorporation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6744–6753 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smith R. D. L., Prévot M., Fagan R. D., Zhang Z., Sedach P. A., Siu M. K. J., Trudel S., Berlinguette C. P., Photochemical route for accessing amorphous metal oxide materials for water oxidation catalysis. Science 340, 60–63 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Benck J. D., Chen Z., Kuritzky L. Y., Forman A. J., Jaramillo T. F., Amorphous molybdenum sulfide catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen production: Insights into the origin of their catalytic activity. ACS Catal. 2, 1916–1923 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merki D., Fierro S., Vrubel H., Hu X., Amorphous molybdenum sulfide films as catalysts for electrochemical hydrogen production in water. Chem. Sci. 2, 1262–1267 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis N. S., Nocera D. G., Powering the planet: Chemical challenges in solar energy utilization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 15729–15735 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook T. R., Dogutan D. K., Reece S. Y., Surendranath Y., Teets T. S., Nocera D. G., Solar energy supply and storage for the legacy and nonlegacy worlds. Chem. Rev. 110, 6474–6502 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pierson J. F., Wiederkehr D., Billard A., Reactive magnetron sputtering of copper, silver, and gold. Thin Solid Films 478, 196–205 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merki D., Vrubel H., Rovelli L., Fierro S., Hu X., Fe, Co, and Ni ions promote the catalytic activity of amorphous molybdenum sulfide films for hydrogen evolution. Chem. Sci. 3, 2515–2525 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCrory C. L., Jung S., Peters J. C., Jaramillo T. F., Benchmarking heterogeneous electrocatalysts for the oxygen evolution reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 16977–16987 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Trotochaud L., Ranney J. K., Williams K. N., Boettcher S. W., Solution-cast metal oxide thin film electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 17253–17261 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith R. D. L., Prevot M. S., Fagan R. D., Trudel S., Berlinguette C. P., Water oxidation catalysis: Electrocatalytic response to metal stoichiometry in amorphous metal oxide films containing iron, cobalt, and nickel. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 11580–11586 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith R. D. L., Sporinova B., Fagan R. D., Trudel S., Berlinguette C. P., Facile photochemical preparation of amorphous iridium oxide films for water oxidation catalysis. Chem. Mater. 26, 1654–1659 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Luo J., Im J.-K., Mayer M. T., Schreier M., Nazeeruddin M. K., Park N.-G., Tilley S. D., Fan H. J., Grätzel M., Water photolysis at 12.3% efficiency via perovskite photovoltaics and Earth-abundant catalysts. Science 345, 1593–1596 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du C., Yang X., Mayer M. T., Hoyt H., Xie J., McMahon G., Bischoping G., Wang D., Hematite-based water splitting with low turn-on voltages. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 12692–12695 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhong L., Wang J., Sheng H., Zhang Z., Mao S. X., Formation of monatomic metallic glasses through ultrafast liquid quenching. Nature 512, 177–180 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knischka R., Lehmann U., Stadler U., Mamak M., Benkhoff J., Novel approaches in NIR curing technology. Prog. Org. Coat. 64, 171–174 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyung J. P., Dae I. W., Development of infrared ray curing technology at continuous coil coating line. Mater. Sci. Forum 654-656, 1819–1822 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Blakemore J. D., Schley N. D., Olack G. W., Incarvito C. D., Brudvig G. W., Crabtree R. H., Anodic deposition of a robust iridium-based water-oxidation catalyst from organometallic precursors. Chem. Sci. 2, 94–98 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huynh M., Bediako D. K., Nocera D. G., A functionally stable manganese oxide oxygen evolution catalyst in acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 6002–6010 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Singh A., Spiccia L., Water oxidation catalysts based on abundant 1st row transition metals. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 2607–2622 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paracchino A., Laporte V., Sivula K., Grätzel M., Thimsen E., Highly active oxide photocathode for photoelectrochemical water reduction. Nat. Mater. 10, 456–461 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu X., Jia H., Sun Z., Chen H., Xu P., Du P., Nanostructured copper oxide electrodeposited from copper(II) complexes as an active catalyst for electrocatalytic oxygen evolution reaction. Electrochem. Commun. 46, 1–4 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andronic L. S., Hill R. H., The mechanism of the photochemical metal organic deposition of lead oxide films from thin films of lead (II) 2-ethylhexanoate. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 152, 259–265 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grosvenor A. P., Kobe B. A., Biesinger M. C., McIntyre N. S., Investigation of multiplet splitting of Fe 2p XPS spectra and bonding in iron compounds. Surf. Interface Anal. 36, 1564–1574 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Platzman I., Brener R., Haick H., Tannenbaum R., Oxidation of polycrystalline copper thin films at ambient conditions. J. Phys. Chem. C 112, 1101–1108 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Louie M. W., Bell A. T., An investigation of thin-film Ni–Fe oxide catalysts for the electrochemical evolution of oxygen. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12329–12337 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material for this article is available at http://advances.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/1/2/e1400215/DC1

Fig. S1. Temperature profiles of substrates under the NIR lamp.

Fig. S2. UV-vis absorption spectra on amorphous films.

Fig. S3. Diffractograms of a-FeOx and a-Fe on FTO.

Fig. S4. Diffractograms of a-FeOx on glass.

Fig. S5. Chronoamperometric measurements of a-FeOx.

Fig. S6. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-FeOx.

Fig. S7. Diffractograms of thin films of a-IrOx, a-NiOx, and a-MnOx.

Fig. S8. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-IrOx, a-NiOx, and a-MnOx.

Fig. S9. TGA and DSC profiles for FeCl3 and Fe(eh)3.

Fig. S10. TGA and DSC profiles for FeCl3 and Fe(eh)3.

Fig. S11. FTIR spectra of independent samples of Fe(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S12. FTIR spectra of thin films of Ir(acac)3/FTO, Ni(eh)2/FTO, and Mn(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S13. X-ray photoelectron spectra for a-FeOx and a-Fe on FTO.

Fig. S14. X-ray photoelectron spectra detailing the Fe 2p3/2 region.

Fig. S15. XPS data for a-CuOx and a-Cu on FTO.

Fig. S16. Images of solid copper samples.

Fig. S17. Diffractograms of a-CuOx and a-Cu.

Fig. S18. FTIR spectra of Fe2Ni3(eh)3/FTO.

Fig. S19. Diffractograms on a-Fe2Ni3Ox and a-Fe2Ni3.

Fig. S20. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-Fe2Ni3Ox and a-Fe2Ni3.

Fig. S21. Cyclic voltammograms for thin films of a-IrOx/membrane.

Fig. S22. FTIR spectra of Ir(acac)3/membrane.

Table S1. Elemental analysis of amorphous metal oxide films determined by EDX.