Abstract

Introduction and Aims

Crack cocaine use among illicit drug users is associated with a range of health and community harms. However, long-term epidemiological data documenting patterns and risk factors for crack use initiation remain limited especially among injection drug users. We investigated longitudinal patterns of crack cocaine use among polydrug users in Vancouver, Canada.

Design and Methods

We examined the rate of crack use among injection drug users enrolled in a prospective cohort study in Vancouver, Canada between 1996 and 2005. We also used a Cox proportional hazards regression analysis to identify independent predictors of crack use initiation among this population.

Results

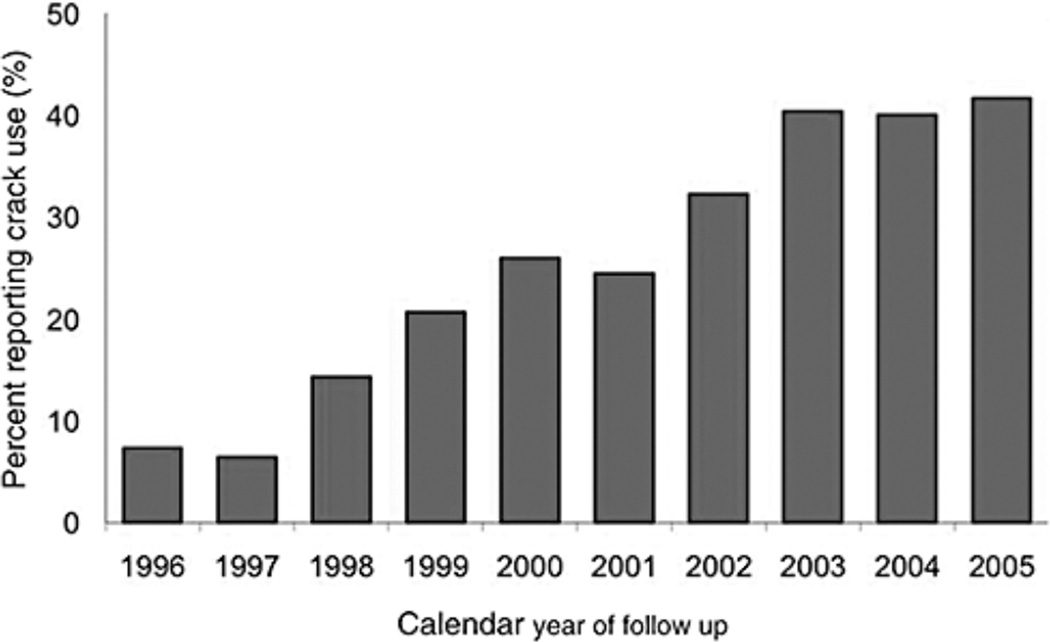

In total, 1603 injection drug users were recruited between May 1996 and December 2005. At baseline, 7.4% of participants reported ever using crack and this rate increased to 42.6% by the end of the study period (Mantel trend test P < 0.001).

Independent predictors of crack use initiation during the study period included frequent cocaine injection, crystal methamphetamine injection, residency in the city's drug using epicenter and involvement in the sex trade (all P < 0.05).

Discussion and Conclusions

These findings demonstrate a massive increase in crack use among injection drug users in a Canadian setting. Our findings also highlight the complex interactions that contribute to the initiation of crack use among injection drug users and suggest that evidence-based interventions are urgently needed to address crack use initiation and to address harms associated with its ongoing use.

Keywords: crack cocaine, injection drug use, initiation, Vancouver, predictive modelling

INTRODUCTION

Recent data have confirmed the wide scope of crack and cocaine use in North America. According to the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)'s World Drug Report 2007, cocaine and crack (a potent, smokeable form of cocaine) are used by 2.8% of Americans and 2.3% of Canadians annually [1]. These rates are among the highest in the world, surpassed only by the annual cocaine consumption rates of Spain (3%) and England & Wales (2.4%) [1]. These data are troubling, considering the serious consequences of crack use. For instance, crack use has been implicated in the transmission of hepatitis C (HCV), HIV and other blood-borne diseases through oral sores [2–5]. Prior research also suggests that crack use may facilitate the transmission of HIV through risky sexual behaviour [6–10]. Despite the identification of these health-related harms, controversy surrounding some health promotion programs, such as the distribution of safer crack kits in North America [11,12], has reduced the ability of many health authorities to combat effectively crack-related harms, as community groups and politicians resist demands by public health experts to provide resources for harm reduction interventions targeted towards crack users rather than employing enforcement-based drug control strategies [11,12].

Despite the increased use of crack in North America, long-term epidemiological data documenting patterns of crack use remain limited, particularly among polydrug-using populations, such as injection drug users (IDU). Although media and police reports suggest that Vancouver, Canada has experienced a massive increase in crack use over the course of the last decade [13,14], this increase has not been scientifically investigated. Given the intense harms associated with crack use, building the scientific evidence base on trends in the incidence and prevalence of crack use in our study setting may aid policymakers in determining the best method of reducing harms and preventing the use of this drug. Therefore, using data from an ongoing prospective cohort study of IDU, we sought to investigate rates of crack use, risk factors for crack use initiation and factors associated with ongoing crack use among this population.

METHODS

The Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study (VIDUS) is a prospective cohort of IDU based in Vancouver, Canada. Beginning in May 1996, recruitment began for active IDU (i.e. those who reported injecting drugs in the previous month) who resided in the Greater Vancouver region. VIDUS participants were recruited through street outreach and self-referral, which involves posting notices in key services, soliciting referrals from service providers and asking participants to refer other individuals. All participants provided written informed consent. At baseline and at scheduled semi-annual follow-up visits (i.e. every 6 months), study participants complete an interviewer-administered questionnaire and provide blood samples for diagnostic testing. Participants are reimbursed $20 for each visit and, when appropriate, are referred to additional health care and addiction treatment [15]. Ethical approval for this study has been granted by the University of British Columbia/Providence Health Care Ethics Review Board.

In our initial analysis, we graphed the prevalence of crack use during each year of the study between May 1996 and December 2005 and performed a Mantel test for trend to identify possible time trends in the prevalence of crack use among all individuals seen during the study period. We also calculated the incidence density of crack use initiation per 100 person-years among those not reporting crack use at baseline and evaluated factors associated with crack use initiation among this population. Here, the unadjusted and adjusted proportional hazards of initiation into crack use were calculated using Kaplan–Meier methods and a Cox proportional hazards analysis. In the latter analyses, all behavioural variables were treated as time-updated covariates based on semi-annual follow-up data. For each participant, relevant behaviourial variables were examined in the questionnaire prior to when the individual reported first crack use to avoid reverse causation (i.e. where associations with crack use are identified as associated with this current behaviour rather than as a risk factor for subsequent initiation).

We also conducted a sub-analysis considering all participants regardless of self-reported crack use at baseline, in which we examined factors associated with crack use throughout the study period. As these factors included serial measures for each subject, we used a generalised estimating equation (GEE) analysis for binary outcomes with logit link for the analysis of correlated data. This was done in order to determine which factors were independently associated with crack use during the study period. These methods provide modified standard errors adjusted by multiple observations per person using an exchangeable correlation structure [16,17].

Based on previous investigations of drug use among Vancouver IDU, we hypothesised that a range of socio-demographic and drug-use behavioural variables may be both potential risk factors for initiation (Cox model) as well as potentially associated with ongoing crack use (GEE model) among our study population [13,15,18]. The following variables were considered: age (per year older), gender (female vs. male), Aboriginal ethnicity (yes vs. no), involvement in the sex trade (yes vs. no), recent incarceration (yes vs. no), unstable housing (yes vs. no), frequent heroin injection (≥daily vs. <daily), frequent cocaine injection (≥daily vs. <daily), crystal methamphetamine use (yes vs. no) and crystal methamphetamine injection (yes vs. no). Variables that were included exclusively in the Kaplan–Meier and Cox proportional hazards analysis included: residency in the downtown eastside (where Vancouver's public illicit drug market is concentrated) (yes vs. no), having a partner who is an IDU (yes vs. no) and engaging in binge drug use (yes vs. no). Variables that were included exclusively in the GEE analysis included: borrowing used syringes (yes vs. no) and lending used syringes (yes vs. no). Variables were selected based on a priori hypotheses about risk factors for initiation into crack use (Cox model) or variables that may be consequences of, or associated with, ongoing crack use (GEE model). For all analyses, variable definitions were identical to previous analyses: recent incarceration was defined as having been in detention, prison or jail in the previous 6 months, and individuals who reported heroin, cocaine or crack use once a day or more were defined as frequent heroin, cocaine or crack users, respectively [18]. Unstable housing was defined as living in a single room occupancy hotel, shelter, recovery or transition house, jail, on the street or having no fixed address. In the Cox proportional hazards analysis, binge drug use was defined as a period in which drugs were used more heavily than usual (i.e. participants were asked the following question: in the last 6 months, have you gone on runs or binges when you injected drugs more than usual?) [15]. All drug-using, behavioural and socioeconomic data collected at baseline and throughout the study period referred to activities undertaken in the previous 6 months.

All multivariate models described were fit using an a priori defined model building protocol of adjusting for all variables that were statistically significant at the P < 0.05 level in bivariate analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS software version 9.1 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA). All P values are two-sided.

RESULTS

In total, 1603 IDUs were recruited between May 1996 and December 2005, including 584 (36.4%) women and 435 (27.1%) individuals who self-identified as Aboriginal. Attrition was low, with 87.7% of cohort participants returning for at least one follow-up visit throughout the study period. The median number of follow-up visits was 10 [Interquartile Range (IQR) = 4–16]. As shown in Figure 1, at baseline, 7.4% of participants reported daily use of crack and 42.6% reported daily use of crack by the end of the study period (Mantel test for trend: P < 0.001). The incidence density of crack use initiation was 8.5% [95% confidence interval (CI): 7.2–9.8%] per 100 person-years.

Figure 1.

Rate of daily crack cocaine use among a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver, Canada over a 10 year period. Mantel test for trend: P < 0.01.

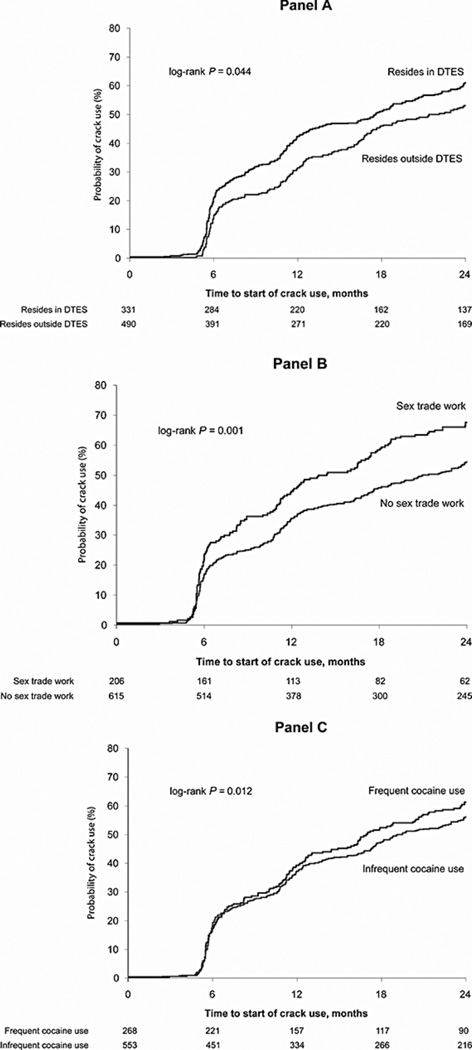

As presented in Figure 2, at 24 months after recruitment into the study, the cumulative incidence of crack use initiation was 60.8% (95% CI: 56.4–65.2%) among those who reported residency in the downtown eastside compared with a rate of 53.2% (95% CI: 47.7–58.7%) among those who did not report residency in the downtown eastside (Panel A; log-rank P > 0.05). During this same period, the cumulative incidence of crack use initiation was 67.4% (95% CI: 60.9–73.9%) among those who reported involvement in sex trade work compared with 54.2% (95% CI: 50.1–58.3%) among those who did not report involvement in sex trade work (Panel B; log-rank P < 0.05). Finally, the cumulative incidence of crack use initiation was 60.9% (95% CI: 54.8–67%) among individuals reporting frequent cocaine injection compared with 55.9% (95% CI: 51.6–60.2%) among those who did not report frequent cocaine injection (Panel C; log-rank P > 0.05). At 24 months, the cumulative incidence of crack use initiation among those not using crack at baseline was 57.6% (95% CI: 54.1–61.1%).

Figure 2.

Time to crack use initiation stratified by residency in the downtown eastside, sex trade work and frequent cocaine use.

Note: The n at the bottom of the figure panels reflect the number of individuals who remain at risk of initiating crack use over time. The diminishing number of participants at risk at each subsequent time interval is a result of events or limited follow up. The rapid increase in probability of crack use after approximately 6 months reflects the fact that individuals only returned for follow up after approximately 6 months.

As shown in Table 1, in multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis, frequent cocaine injection [adjusted hazard ratio (AHR) = 1.39, 95% CI: 1.17–1.66], injection crystal methamphetamine use (AHR = 1.55, 95% CI: 1.06–2.26), residency in the downtown eastside (AHR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.31–1.82), recent incarceration (AHR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.14–161) and involvement in the sex trade (AHR = 1.66, 95% CI: 1.37–2.02) were found to be independently predictive of crack use initiation among this cohort (all P < 0.05).

Table 1.

Cox proportional hazards analysis of factors predictive of crack use initiation during follow up (n = 821)

| Characteristic | Adjusted hazards ratioa (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Cocaine injection | ||

| ≥Daily vs. <daily | 1.39 (1.17–1.66) | <0.001 |

| Crystal methamphetamine injection | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.55 (1.06–2.26) | <0.025 |

| Heroin injection | ||

| ≥Daily vs. <daily | 1.04 (0.88–1.22) | 0.656 |

| Unstable housing | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.00 (0.85–1.19) | 0.949 |

| Residency in the downtown eastside | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.54 (1.31–1.82) | <0.001 |

| Recent incarceration | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.36 (1.14–1.61) | <0.001 |

| Sex trade involvement | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.66 (1.37–2.02) | <0.001 |

Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, crystal methamphetamine use, having a sexual partner who is an injection drug user and binge drug use.

CI, confidence interval.

As shown in Table 2, in multivariate GEE analysis, involvement in the sex trade [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 1.56, 95% CI: 1.36–1.80], unstable housing (AOR = 1.26, 95% CI: 1.17–1.37), frequent heroin injection (AOR = 1.21, 95% CI: 1.10–1.33), crystal methamphetamine use (AOR = 1.63, 95% CI: 1.32–2.02) and crystal methamphetamine injection (AOR = 1.23, 95% CI: 1.02–1.48) were found to be independently associated with crack use (all P < 0.05).

Table 2.

Multivariate logistic regression (GEE) analysis of factors associated with crack use during follow up (n = 1603)

| Characteristic | Adjusted odds ratioa (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|

| Sex trade involvement | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.56 (1.36–1.80) | <0.001 |

| Unstable housing | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.26 (1.17–1.37) | <0.001 |

| Recent incarceration | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.04 (0.95–1.13) | 0.426 |

| Heroin injection | ||

| ≥Daily vs. <daily | 1.21 (1.10–1.33) | <0.001 |

| Cocaine injection | ||

| ≥Daily vs. <daily | 1.05 (0.95–1.15) | 0.335 |

| Crystal methamphetamine use | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.63 (1.32–2.02) | <0.001 |

| Crystal methamphetamine injection | ||

| Yes vs. no | 1.23 (1.02–1.48) | 0.030 |

Adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, borrowing used syringes, lending used syringes and unsafe sex.

CI, confidence interval; GEE, generalised estimating equation.

DISCUSSION

The data presented here demonstrate a massive increase in crack use over a 10 year period among a cohort of IDU in Vancouver, Canada. Involvement in the sex trade and residency in the city's illicit drug use epicentre were strong independent predictors of initiating crack use among those not reporting crack use at baseline. When we examined factors associated with active crack use, frequent heroin injection, crystal methamphetamine use, crystal methamphetamine injection, involvement in the sex trade and residing in an unstable housing situation were all positively associated with crack use after adjustment for a range of potential confounders.

These results have far-reaching implications. Specifically, involvement in the sex trade and injection drug use, particularly among individuals reporting unstable housing, carry well-known risks for the transmission of HIV and other blood-borne diseases [19,20]. As such, our findings also suggest that crack users may be at higher risk of negatively impacting public order through involvement in the sex trade and as a result of the potential association between crack use and unstable housing. That socioeconomic factors, such as residency in the downtown eastside and involvement in sex trade work, appear to be predictive of crack use initiation among this sample suggests that crack use initiation may be deterred through the application of interventions that address these predictive factors, though more research is required in this area. While the impacts of crystal methamphetamine use among our study population are not well known, our finding that crystal methamphetamine injection independently predicted subsequent initiation of crack use suggests a variety of possible explanations. Crystal methamphetamine may promote transition to use of other stimulants, such as crack [21], or alternately, an unmeasured confounding factor may be related to both crystal methamphetamine and crack use among IDU in our sample. These findings should be considered in light of previous research suggesting that crack users are at heightened risk for a variety of health-related harms [6,22–25]. While drug use behaviours among our cohort appear to have migrated towards crack use over the last decade, rates of polydrug use and risky behaviours remain high among this population. We also observed that recent incarceration was predictive of subsequent crack use initiation among our cohort participants. This finding requires further study to determine whether the incarceration of IDU plays a causal role in the initiation of crack use among this population. Additionally, further research should be directed towards an investigation of polydrug use in the context of crack use, with a particular focus on the use of illicit drugs by individuals self-medicating to reduce the negative effects of crack consumption.

Though we observed a shift towards crack use among our cohort, our findings should be relevant for researchers and policymakers in settings experiencing substantial shifts in all drug use behaviours among vulnerable populations. Specifically, the rise in levels of polydrug use that we observed over a 10 year study period suggests that strategies that restrict focus to particular drugs may have limited long-term utility in addressing HIV and other drug-related risk behaviours. Instead, the implementation of a comprehensive set of interventions with a broad focus on illicit drug addiction may better address the diverse health needs of polydrug-using subpopulations. With respect to our study setting, it should be noted that drug use and associated high-risk behaviours are deeply entrenched among IDU and other polydrug-using subpopulations. Further, previous research in our study setting has demonstrated the limited ability of stand-alone public health interventions to adequately modify high-risk behaviours and we therefore conclude that a range of interventions may be required to successfully reduce the incidence of polydrug use and its related public health and public order harms [8,26,27].

Our study contains several limitations. First, our sample was made up of IDU, and our findings may not therefore be generalisable to non-IDU polydrug-using populations. Additionally, VIDUS is not a random sample and therefore these results may not be generalisable to other IDU populations, though it is noteworthy that previous studies of IDU in Vancouver suggest that VIDUS is representative of our population of interest [13,28,29]. As well, given the stigmatised nature of such activities, it is likely that self-reported drug use, incarceration and risk behaviours (e.g. syringe sharing) may have been under-reported among this cohort as has been observed in prior cohort studies of IDU [30]. The possibility also exists that we were not able to adjust for all variables that may have contributed to the increase in rates of crack use that we observed. However, this increase is likely explained by an increased availability of crack and a corresponding low price of crack in comparison with heroin or cocaine in our study setting [1,31,32].

Over a 10 year period, we observed a large increase in crack use among a representative sample of IDU in Vancouver. While drug use behaviours have diversified greatly from injection drug use over the last decade among our cohort, our findings suggest that a range of risk behaviours and socio-demographic factors may perpetuate drug-related harms among crack users. These findings indicate an urgent need for the consideration of a range of interventions aimed at reducing the vulnerability of those who use crack or are at high risk of initiating use of this drug. Additionally, data from a variety of settings indicate sustained increases in the rate of crack use among drug-using populations, as well as high levels of polydrug use among those who use crack [1,3,33,34]. Further, research suggests that crack users often face a double burden of poor health and social marginalisation [35]. Both an expansion and a redoubled commitment to combating drug-related harms creatively and comprehensively are therefore urgently needed in our setting and elsewhere to reduce the many harms related to illicit drug use, and these efforts should be coupled with ongoing monitoring of crack- and polydrug-using populations.

Acknowledgements

We would particularly like to thank the VIDUS participants for their willingness to be included in the study, as well as current and past VIDUS investigators and staff. We would specifically like to thank Deborah Graham, Tricia Collingham, Caitlin Johnston, Steve Kain and Calvin Lai for their research and administrative assistance.

The VIDUS is supported by CIHR Grant HHP-67262 and by NIH Grant R01 DA011591. Further support is provided CIHR Team Grant RAA-79918. Thomas Kerr, Kora DeBeck and Dan Werb are supported by the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The funders had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

D. W. and E. W. drafted the initial manuscript. K. L. performed the statistical analyses. J. M., T. K. and K. D. performed significant revisions to the manuscript. All authors were involved in the design of the study and approved the final version of the manuscript.

J. M. has received grants from, served as an ad hoc adviser to, or spoken at events sponsored by Abbott, Argos Therapeutics, Bioject Inc., Boehringer Ingelheim, BMS, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Hoffmann-La Roche, Janssen-Ortho, Merck Frosst, Panacos, Pfizer Ltd, Schering, Serono Inc., TheraTechnologies, Tibotec (J & J) and Trimeris.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

D. W., K. D., T. K., K. L. and E. W. have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.UNODC. World Drug Report 2007. Report. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Faruque S, Edlin BR, McCoy CB, et al. Crack cocaine smoking and oral sores in three inner-city neighborhoods. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1996;13:87. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199609000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward H, Pallecaros A, Green A, Day S. Health issues associated with increasing use of ‘crack’ cocaine among female sex workers in London. Sex Transm Infect. 2000;76:292. doi: 10.1136/sti.76.4.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elifson KW, Boles J, Darrow WW, Sterk CE. HIV seroprevalence and risk factors among clients of female and male prostitutes. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1999;20:195. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199902010-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doherty MC, Garfein RS, Monterroso E, Brown D, Vlahov D. Correlates of HIV infection among young adult shortterm injection drug users. AIDS. 2000;14:717. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200004140-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edlin B, Irwin K, Faruque S, et al. Intersecting epidemics— crack cocaine use and HIV infection among inner-city young adults. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1422. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199411243312106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kuyper LM, Lampinen TM, Li K, et al. Factors associated with sex trade involvement among male participants in a prospective study of injection drug users. Sex Transm Infect. 2004;80:531. doi: 10.1136/sti.2004.011106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Collins CL, Kerr T, Kuyper LM, et al. Potential uptake and correlates of willingness to use a supervised smoking facility for noninjection illicit drug use. J Urban Health. 2005;82:276–284. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wechsberg WM, Lam WK, Zule W, Hall G, Middlesteadt R, Edwards J. Violence, homelessness, and HIV risk among crack-using African-American women. Subst Use Misuse. 2003;38:669. doi: 10.1081/ja-120017389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webber MP, Schoenbaum EE, Gourevitch MN, Buono D, Klein RS. A prospective study of HIV disease progression in female and male drug users. AIDS. 1999;13:257. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199902040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staff. Ottawa council scraps crack pipe program. CBC. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunter J. A measure of prevention in a little bag of goodies. Globe and Mail. 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Buxton J, Mehrabadi A, Preston E, Tu A. Vancouver site report for the Canadian Community Epidemiology Network on Drug Use (CCENDU). Report. Vancouver: City of Vancouver; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones D. Detoxifying Vancouver’s drug culture. Globe and Mail. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kerr T, Palepu A, Barness G, et al. Psychosocial determinants of adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy among injection drug users in Vancouver. Antivir Ther. 2004;9:407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang KY, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986;73:13. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zeger SL, Liang KY. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42:121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wood E, Tyndall MW, Spittal PM, et al. Unsafe injection practices in a cohort of injection drug users in Vancouver: could safer injecting rooms help? CMAJ. 2001;165:405. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Corneil T, Kuyper LM, Shoveller J, et al. Unstable housing, associated risk behaviour, and increased risk for HIV infection among injection drug users. Health Place. 2006;12:79. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller CL, Spittal PM, LaLiberte N, et al. Females experiencing sexual and drug vulnerabilities are at elevated risk for HIV infection among youth who use injection drugs. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2002;30:335. doi: 10.1097/00126334-200207010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fairbairn N, Kerr T, Buxton JA, Li K, Montaner JS, Wood E. Increasing use and associated harms of crystal methamphetamine injection in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;88:313. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Falck RS, Wang J, Siegal HA, Carlson RG. The prevalence of psychiatric disorder among a community sample of crack cocaine users: an exploratory study with practical implications. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192:503. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000131913.94916.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seddon T. Drugs, crime and social exclusion: social context and social theory in British drugs-crime research. Br J Criminol. 2006;46:680. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferri CP, Gossop M. Route of cocaine administration: patterns of use and problems among a Brazilian sample. Addict Behav. 1999;24:815. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(99)00036-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prinzleve M, Haasen C, Zurhold H, et al. Cocaine use in Europe—a multi-centre study: patterns of use in different groups. Eur Addict Res. 2004;10:147. doi: 10.1159/000079835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strathdee SA, Patrick DM, Currie SL, et al. Needle exchange is not enough: lessons from the Vancouver injecting drug use study. AIDS. 1997;11 doi: 10.1097/00002030-199708000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Collins CL, Kerr T, Tyndall MW, et al. Rationale to evaluate medically supervised safer smoking facilities for noninjection illicit drug users. Can J Public Health. 2005;96:344. doi: 10.1007/BF03404029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Public Health Agency of C. I-Track: Enhanced surveillance of risk behaviours among people who inject drugs. Phase I report. Report. Ottawa: Surveillance and Risk Assessment Division, Centre for Infectious Disease Prevention and Control, Public Health Agency of Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Remis RS, Strathdee SA, Millson M, et al. Consortium to characterize injection drug users in Montreal, Toronto and Vancouver, Canada. Report. Ottawa: Bureau of HIV/AIDS, STD and TB, Health Canada; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Des Jarlais DC, Paone D, Milliken J, et al. Audio-computer interviewing to measure risk behaviour for HIV among injecting drug users: a quasi-randomised trial. Lancet. 1999;353:1657. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)07026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UNODC. Global illicit drug trends 2003. Report. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 32.UNODC. Global illicit drug trends 2001. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Parry CDH, Plüddemann A, Myers BJ. Cocaine treatment admissions at three sentinel sites in South Africa (1997– 2006): findings and implications for policy, practice and research. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2007;2:37–45. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-2-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNODC. World Drug Report 2006. Vienna: United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tyndall MW, Currie S, Spittal P, et al. Intensive injection cocaine use as the primary risk factor in the Vancouver HIV-1 epidemic. AIDS. 2003;17:887. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304110-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]