Abstract

Many important learning tasks feel uninteresting and tedious to learners. This research proposed that promoting a prosocial, self-transcendent purpose could improve academic self-regulation on such tasks. This proposal was supported in four studies with over 2,000 adolescents and young adults. Study 1 documented a correlation between a self-transcendent purpose for learning and self-reported trait measures of academic self-regulation. Those with more of a purpose for learning also persisted longer on a boring task rather than giving in to a tempting alternative, and, many months later, were less likely to drop out of college. Study 2 addressed causality. It showed that a brief, one-time psychological intervention promoting a self-transcendent purpose for learning could improve high school science and math GPA over several months. Studies 3 and 4 were short-term experiments that explored possible mechanisms. They showed that the self-transcendent purpose manipulation could increase deeper learning behavior on tedious test review materials (Study 3), and sustain self-regulation over the course of an increasingly-boring task (Study 4). More self-oriented motives for learning—such as the desire to have an interesting or enjoyable career—did not, on their own, consistently produce these benefits (Studies 1 and 4).

Keywords: Self-regulation, Motivation, Purpose, Meaning, Psychological intervention

“It's only when you hitch your wagon to something larger than yourself that you realize your true potential and discover the role that you'll play in writing the next great chapter in the American story.”

- President Barack Obama,

Wesleyan University Commencement Speech, 2008

Many of the tasks that contribute most to the development of valuable skills are also, unfortunately, commonly experienced as tedious and unpleasant (Duckworth, Kirby, Tsukayama, Berstein, & Ericsson, 2010; also see Ericsson, 2006, 2007, 2009; Ericsson & Ward, 2007; Ericsson, Krampe, & Tesch-Romer, 1993). For example, skills in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) are in high demand, and, according to some estimates, jobs in the STEM sector will grow by more than 20% in the next few decades (U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee, 2012). Yet in a representative sample survey, over half of middle school students said they would rather eat broccoli than do their math homework; 44% would rather take out the trash (Raytheon Company, 2012).

To achieve longer-term aims, learners must sometimes regulate attention, emotion, and behavior in the face of tempting alternatives (Duckworth & Carlson, in press; Fujita, 2011; Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989). Indeed, individual differences in factors such as “grit” and self-control are predictive of eventual skill acquisition and expert performance, controlling for cognitive ability (Duckworth, Tsukayama, & Kirby, 2013; Duckworth, Peterson, Matthews, & Kelly, 2007; Moffitt et al., 2011). Where do these factors come from? Individuals are known to marshal self-discipline more when they are pursuing personally-meaningful goals (see Fishbach & Trope, 2005; Fishbach, Zhang, & Trope, 2010; Loewenstein, 1996; Mischel, Cantor, & Feldman, 1996; Rachlin, Brown, & Cross, 2000; Thaler & Shefrin, 1981; Trope & Fishbach, 2000; also see Eccles, 2009, Marshall, 2001). In the present research we propose that what has been called a purpose for learning (Andrews, 2011; Yeager, Bundick, & Johnson, 2012) can foster greater meaning in schoolwork and promote academic self-regulation as students take on tedious learning tasks.

Defining a “Purpose for Learning”

An enormous amount of research has focused on the wide variety of possible motives for engaging in and succeeding at learning tasks (e.g., Ames, 1992; Atkinson, 1957; Carver & Scheier, 1981; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002; Elliot et al., 2010; Emmons, 1986; Ford & Nichols, 1987; Harackiewicz & Sansone, 1991; Higgins, 2005; Lepper, Corpus, & Iyengar, 2005; Markus & Nurius, 1986; Nicolls, 1984; Little, 1983; Oyserman & Destin, 2010; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Here we focus on only one distinction—that between self-interest and self-transcendence. Learners may view a task as likely to benefit the self, believing it will be intrinsically enjoyable or lead to a personally-fulfilling career (see Eccles & Wigfield, 1995). Learners may also have motives that transcend self-interest. These may involve service to other individuals, to an ideal, to a social justice cause, or to a spiritual entity (Damon, Menon, & Bronk, 2003; Frankl, 1963; Koltko-Rivera, 2006; Schwartz, 1992; Maslow, 1969; also see Eccles, 2009).

We define a “purpose for learning” as a goal that is motivated both by an opportunity to benefit the self and by the potential to have some effect on or connection to the world beyond the self (Yeager & Bundick, 2009; Yeager et al., 2012; see Burrow & Hill, 2011; Damon et al., 2003). Embedded in this definition is a focus on the motive or rationale for the goal (e.g., “helping people”) rather than on content of a goal (e.g. “being an engineer;” Massey, Gebhardt, & Garnefski, 2008). For example, a purpose for learning in a high school science class might be that a student would one day like to use the acquired knowledge to build bridges that help people (a self-transcendent component). The same student might also believe that engineering would be a fulfilling, interesting, and enjoyable career (a self-oriented component). Both of these types of motives—self-oriented and self-transcendent—can be important for learners and can motivate task persistence (Eccles, 2009; Eccles & Wigfield, 2002). These different motives also frequently co-exist (Batson, 1998; also see Feiler, Tost, & Grant, 2012). In fact, in a series of qualitative interviews conducted with a diverse group of high school adolescents, it was common for teens to pair self-transcendent motives with self-oriented motives—much more common in fact than having only a self-transcendent motive (Yeager & Bundick, 2009; Yeager et al., 2012). Here we examine whether adding self-transcendent motives to self-oriented ones—what we call a “purpose for learning”—could produce benefits that self-oriented motives alone could not achieve.

Purpose, Meaning and Persistence

There is good reason to believe that a purpose for learning could promote the view that a task is personally meaningful (e.g., Grant, 2007, 2013; Olivola & Shafir, 2013; also see Duffy & Dik, 2009; Steger et al., 2008; Steger, 2012).1 A classic example comes from Viktor Frankl (1963). In writing about the psychology of surviving a concentration camp, he describes how a self-transcendent purpose in life creates a feeling that one’s actions are important for the world, empowering a person to persist even in the most appalling circumstances. He wrote “A [person] who becomes conscious of the responsibility he bears toward a human being who affectionately waits for him, or to an unfinished work, will never be able to throw away his life” (p. 80). Channeling Neitzche, Frankl states “He knows the ‘why’ for his existence and will be able to bear almost any ‘how’” (1963, p. 80).

Further support comes from observational research of people working in “dirty” jobs—jobs with low-status and requiring extremely repetitive tasks (e.g., trash men, hospital orderlies, prison guards). Individuals with these jobs find their work more meaningful and carry it out more effectively when they focus on the benefit of these tasks for helping others or society at large (Ashforth & Kreiner, 1999; Hughes, 1958, 1962; also see Dutton, Roberts, & Bednar, 2010; Wrzesniewski, Dutton, & Debebe, 2003; cf. Olivola & Shafir, 2013). Altogether, highly aversive experiences may become more bearable when they are viewed as having consequences that transcend the self.

More directly relevant, Yeager et al. (2012) found that some high school-aged adolescents spontaneously generated a purpose for learning during interviews—mentioning both a self-transcendent motive and an intrinsic, self-oriented motive for their future work, such as “being a doctor to help people and because it would be enjoyable.” Students with a purpose rated their schoolwork in general as more personally meaningful than adolescents with no career goal or only extrinsic motives (making money, gaining respect), even at a two-year follow-up (also see Lepper et al., 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000). Other high school students discussed only typical interest-based, self-oriented motives. This group rated their schoolwork as no more meaningful compared to students with no future work goals or only extrinsic motives (Yeager et al., 2012). However, this study was limited in that it did not directly assess perceptions of tedious, skill-building tasks. Nor did it assess behavior or address causality with experimental designs. These limitations are addressed in the present research.

Some past experiments have linked prosocial, self-transcendent motives to behavioral persistence on tasks at work, not school. For example, telemarketers raised more money when they were asked to focus on the benefits of their efforts for poor children as compared to benefits for the self, while medical professionals were more likely to stop and wash their hands when they focused on others’ health as opposed to their own health (Grant, 2008; Grant & Hoffman, 2011; also see Feiler et al., 2012; for findings from other workplaces see, Grant & Rothbard, 2013; cf. Sansone, Weir, Harpster, & Morgan, 1992). Note that a self-transcendent motive makes aversive experiences more bearable, not more enjoyable; prosocial motives diminish the correlation between feeling bad during a task and the reduced motivation to complete it (Grant & Sonnentag, 2010; also see Grant & Campbell, 2007). Prosocial trash men do not find trash more appealing, but they collect it more effectively (Hughes, 1958, 1962)

The present research is among the first to test whether students with more of a self-transcendent purpose for learning can show greater persistence even on tedious learning activities that provide a foundation for uncertain future contributions to the world beyond the self (see Harackiewicz & Sansone, 1991). Some past studies investigated, for instance, raising money for poor children (Grant, 2008; also see Dunn, Aknin, & Nortin, 2008) or preventing infection (Grant & Hoffman, 2011). It is easy to see how these actions help others. But when high school students engage in a learning task such as factoring trinomials in Algebra, or balancing stoichiometric equations in Chemistry, it can be difficult to see the steps through which deeply learning from these tasks can help them benefit others. That is, raising money for poor people is directly prosocial, but learning fractions must be construed as such.

Other past research has found that providing intrinsic vs. extrinsic motives for learning tasks (e.g., becoming healthy vs. looking physically attractive) can lead to greater task persistence and deeper processing of information (e.g., Vansteenkiste, Simons, Lens, Sheldon, & Deci, 2004; also see Jang, 2008; for a review, see Vansteenkiste, Lens, & Deci, 2006 or Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008). Similarly, some research has found that asking students to generate reasons why a learning task could be relevant to their daily lives and future goals could improve course performance among low-performers, by enhancing the perceived utility value of a task (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; Hulleman, Godes, Hendricks, & Harackiewicz, 2010). These studies were foundational to the present research. However they were not designed to distinguish the intended beneficiary of the learning—the self versus something that transcends the self—as the present research seeks to do.

In addition, past studies have focused on the perceived prosocial value of completing a given task or learning objective (Eccles & Wigfield, 1995)—for instance, learning about correlation coefficients to interpret education research (Jang, 2008), or using the week’s science class lessons to help out on the family farm (Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; see Eccles et al., 1983; Eccles, 2009). However an important skill for self-regulation is to abstract up a level from the task at hand to one’s motives for being involved in an educational enterprise more generally—e.g., “science” or “math” or even “school.” It is often uncertain whether or how one will use the knowledge gained from a given learning objective or task. Indeed, teachers very rarely provide any rationale for mastering a learning objective (Stipek, 2004; also see Eccles, 2009), let alone a self-transcendent rationale. This is especially true in STEM courses, where many tasks are unexplained (Carnevale & Desrochers, 2003; also see Diekman, Clark, Johnston, Brown, & Steinberg, 2011). It may be helpful to re-construe a foundational task—such as practicing math facts—more generally in terms of their relation to one’s broader, self-transcendent motives for working hard in school or in a subject area.

The Present Research

Four studies investigated the hypothesis that a higher-order, self-transcendent purpose for learning in school would promote academic self-regulation on tedious schoolwork. In Study 1 we hypothesized that a self-transcendent purpose for learning would be correlated with indicators of academic self-regulation both at the trait level (self-reported grit and self-control) and at the behavioral level (short-term persistence on a boring math task and longitudinal persistence in college). We further hypothesized that these relations would be found above and beyond the effects of more intrinsic, self-oriented motives (e.g., following one’s intellectual interests), and of cognitive ability.

Study 2 examined a possible causal effect of a self-transcendent purpose for learning. In order to do so it was necessary to create an exercise to adjust adolescents’ purposes for learning, which past research has had difficulty doing (Dik, Steger, Gibson, & Peisner, 2011). Indeed, a purpose is likely to be highly personal and represent the product of a large number of influences in life, including teachers, parents, friends and the media, perhaps making it difficult to manipulate (e.g., Damon, 2008; Harackiewicz, Rozek, Hulleman, & Hyde, 2012; Moran, Bundick, Malin, & Reilly, 2013; Steger, Bundick, & Yeager, 2012). Yet advances have been made in recent years in the optimal design of psychological interventions in educational settings (e.g., Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007; Cohen & Sherman, 2014; Garcia & Cohen, 2012; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; Walton & Cohen, 2011; also see Walton, 2014; Wilson & Linville, 1982). We were informed by these. We hypothesized that a novel self-transcendent purpose for learning intervention could improve grades in subject areas likely to be seen as tedious, such as high school math and science classes.

Studies 3 and 4 examined potential behavioral antecedents to the outcomes studies in Studies 1 and 2. Specifically, Study 3 examined effects of the novel intervention on behavior on a shorter time-course, testing the hypothesis that a self-transcendent purpose for learning could lead students to learn more deeply from an immediate, real-world academic task. Study 4 sought to isolate the effect of a purpose for learning manipulation on self-regulation more precisely by administering a dependent measure that pitted a boring math activity directly against tempting alternatives.

Study 1: An Initial Correlational Investigation

Study 1 was a correlational study among a low socioeconomic status (SES) group of high school seniors. Based on prior research, they might have significant difficulty regulating immediate motivations in the service of long-term goals (Evans & Rosenbaum, 2008; Vohs, 2013). We hypothesized that in this population a self-transcendent purpose would correlate with indicators of self-discipline—both self-reported and behavioral—assessed at the same measurement time. We further hypothesized that, in a multiple regression controlling for more self-oriented motives—even intrinsic-interest-focused ones—a purpose for learning would continue to predict greater success at self-regulation.

We also examined longitudinal relations with goal persistence. This was done by collecting data on whether students were enrolled in college in the Fall semester following high school graduation, as they intended to do. Low-income students of color more commonly drop out of the college pipeline in the summer after college or during their first Fall semester, even when they have successfully graduated high school and been admitted to a college of their choice (Ryu, 2012). We hypothesized that a self-transcendent purpose would predict college persistence over time—a potential indicator of successfully regulating competing demands for time and attention in this low-income population. We also hypothesized that this relation would be found when controlling for self-oriented motives in a multiple regression.

Method

Participants

Participants were N = 1,364 seniors in their final semester at one of 17 participating urban public high schools (eight charters and two district schools). Ninety-nine percent said that they had applied for college and were planning on attending college in the Fall semester. They were located in Los Angeles, CA, Oakland, CA, New York City, NY, Austin, TX, Houston, TX, or Little Rock, AR. They were from low socio-economic backgrounds: over 90% received free or reduced-price lunch, a measure of low socio-economic status, and only 9% had one parent who had completed a 2 or 4-year degree; by contrast, 25% of parents did not have a high school diploma. The sample overall was nearly evenly split on gender (57% female), and had a large proportion of students that are typically under-represented in higher education in the U.S., 38% African American, 48% Hispanic / Latino, 5% Asian, 4% White. Some participants did not provide data on some measures, and so degrees of freedom varied across analyses. No other participants were excluded from analyses. There was no stopping rule for data collection because all college-going students in each school were invited to participate.

Procedures

Participants completed a web-based survey in the school’s computer lab during the school day in the Spring semester (February to May) of senior year. Teachers directed students to a website (www.perts.net) that delivered the survey session, which lasted one class period. Many months later, toward the end of what was the Fall semester for students in college, college persistence data were collected from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC).

Measures

Motives for going to college

The primary predictor variables were self-transcendent motives, intrinsic self-oriented motives, and extrinsic self-oriented motives. The preface for the items assessing these motives was: “How true for you personally are each of the following reasons for going to college?” Each was rated on a five-point scale (Response options: Not at all true, Slightly true, Somewhat true, Very true, Completely true) and coded to range from 1 to 5, with 5 corresponding to greater endorsement.

Self-transcendent motives (purpose for learning)

We averaged across the following three items to assess students’ self-transcendent motives for going to college (a purpose for learning), operationalized as a personally-relevant desire to learn in order to make a contribution to the world beyond the self: “I want to learn things that will help me make a positive impact on the world,” “I want to gain skills that I can use in a job that help others,” and “I want to become an educated citizen that can contribute to society” (α = .75).

Self-oriented motives

We averaged across the following three items adapted from Stephens et al.’s (2012) assessment of self-oriented, interest-driven motives for going to college: “I want to expand my knowledge of the world,” “I want to become an independent thinker,” and “I want to learn more about my interests” (α = .70). Note that these are still personally-important intrinsic motives for learning, and might be expected to predict greater self-regulation, thus providing a high standard of comparison for the self-transcendent motives.

Extrinsic motives

Finally, we measured typical extrinsic, self-oriented motives for going to college: “I want to get a good job,” “I want to leave my parents’ house,” “I want to earn more money,” and “I want to have fun and make new friends.” We wrote these items in collaboration with college counselors at the participating high schools. They were designed to reflect the counselors’ perceptions of why students want to go to college. Although the internal consistency reliability for these items was somewhat low (α = .50), they were face-valid. Below we show that a composite of these items produced relations with each of the constructs measured that replicates past research (Lee, McInerney, Liem, & Ortiga, 2010), supporting the validity of the composite despite low internal consistency. The same findings emerged when analyzing these items separately.

Meaningfulness of schoolwork

To assess individual differences in the meaningfulness of everyday academic tasks, we adapted a measure commonly used in research on action-identification theory: the Behavioral Identification Form (BIF; Vallacher & Wegner, 1989). The standard BIF asks participants to view a task and choose a description of it that either aligns with personally-meaningful values or goals, or with concrete actions required to complete the task. In the present research, we treat the choice of the former, more goal-directed description as an indication that a person is viewing it more meaningfully. Indeed, Michaels, Parkin and Vallacher (2013) stated “people take meaning from their goals and values rather than the details of their actions” (p. 109).

We created a four-item version of the BIF that was tailored to assess whether students chronically make meaning out of boring and uninteresting everyday academic tasks in high school. See Figure 1 for an example. The measure presented participants with a description of each behavior, accompanied by a picture, and asked participants to select which of two action identifications best matched how they thought about the behavior. The four behaviors were “Taking the SAT,” “Doing your math homework,” “Writing an essay,” and “Using a planner to record upcoming tasks” (for pictures and response options, see the online supplement). In pre-testing focus groups with high school students, all four behaviors were evaluated as very tedious and very common. For each of the behaviors, (e.g., taking the SAT), we asked students whether a more concrete, lower-level statement (a description that emphasizes the means by which the action is performed, e.g., “Filling out bubbles on the SAT”) or a more goal-directed, personally-meaningful statement (a description emphasizing the meaning the action can have for a person’s pursuits in life, e.g., “Taking steps toward a college degree”) best described that behavior. The latter was our operationalization of whether the task was seen as more personally-meaningful. We summed across the items, so that higher values corresponded to a greater tendency to see schoolwork as meaningful (Range: 0 to 4).2

Figure 1. Sample item for assessing the meaningfulness of schoolwork.

Grit scale

Participants completed an abbreviated version of the validated grit scale (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009), a measure that signals strong self-regulation in a number of past studies. The scale asks: “I finish whatever I begin,” “I work very hard. I keep working when others stop to take a break,” “I stay interested in my goals, even if they take a long time (months or years) to complete,” and “I am diligent. I never give up.” Participants answered all items on 5-point fully-labeled scales (Response options: Not at all like me, Not much like me, Somewhat like me, Mostly like me, Very much like me). We averaged across the responses, with higher values corresponding to higher levels of grit (α = .78).

Self-control scale

Participants completed a validated measure of self-control when completing academic work (Tsukayama, Duckworth, & Kim, 2013; Patrick & Duckworth, 2013). Items were: “I come to class prepared,” “I pay attention and resist distractions in class,” “I remember and follow directions,” and, “I get to work right away rather than procrastinating” (Response options: Not at all like me, Not much like me, Somewhat like me, Mostly like me, Very much like me). We averaged across these items, with higher values corresponding to greater academic self-control, (α = .71). Past research has shown that these items are correlated with other measures of self-regulation (such as grit, e.g. Table 1) but demonstrate divergent validity from them (Duckworth et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Zero-Order Correlations for Study 1 Measures.

| Self- transcendent motives (“Purpose for learning”) |

Self-oriented, intrinsic motives |

Extrinsic motives |

Meaningful- ness of schoolwork |

Self- reported grit |

Self-reported self-control |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Self-transcendent motives (“Purpose for learning”) | - | |||||

| Self-oriented, intrinsic motives | 0.66*** | |||||

| Extrinsic motives | 0.61*** | 0.48*** | ||||

| Meaningfulness of schoolwork | 0.23*** | 0.20*** | 0.19*** | |||

| Self-reported grit | 0.39*** | 0.32*** | 0.32*** | 0.26*** | ||

| Self-reported self-control | 0.33*** | 0.26*** | 0.21*** | 0.22*** | 0.58*** | |

| Number of boring math problems solved during the diligence task |

0.09** | 0.04 | −0.09** | 0.09** | 0.07* | 0.16*** |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

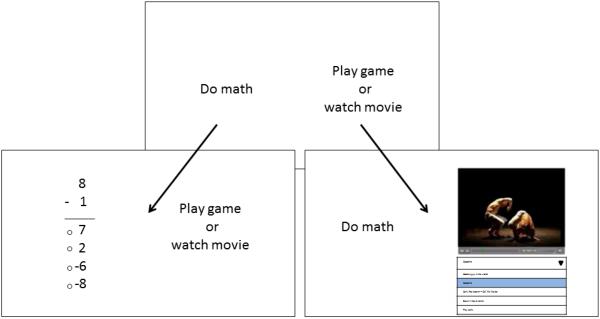

The “diligence task:” A behavioral measure of academic self-regulation

At the end of the survey, participants completed a novel standardized behavioral measure of self-regulation, called “the diligence task” (Galla et al., 2014). This task was designed to mirror the real-world choices students confront when completing homework and being tempted by the distractions of the digital age. Specifically, this task involved the choice of completing boring math problems (single-digit subtraction) or consuming captivating but time-wasting media (watching one or several entertaining, brief, viral videos [lasting 20-60 seconds] or playing the video game Tetris). At any time, participants could click on the left side of the screen and complete math problems (“Do Math”) or click on the right side of the screen and consume media (“Play game or watch movie”). Participants were told there were no negative consequences for their choices and that they could do whatever they preferred. See Figure 2. The software (unknown to the participant) tracked the number of math problems completed successfully, producing our focal dependent measure.

Figure 2. The “diligence task:” A behavioral measure of academic self-regulation.

To make the math problems potentially meaningful in students’ eyes—and worth completing—we told participants that successfully completing the tasks could possibly help them sharpen their math skills and stay prepared for their future careers. As a part of this cover story, we presented participants with summaries of actual scientific studies showing that increasingly as people rely on technology to do simple tasks, their grasp of basic skills can atrophy. As a result, all participants could plausibly see the successful completion of boring math problems as preparatory for a future career, if they so desired.

The task itself involved three blocks. Block 0 was a warm-up block to become familiar with the layout of the task. It involved a brief (1 minute) set of math problems, but without the option to play videos or video games. It will not be discussed further. Blocks 1 and 2 lasted four minutes each and involved the key behavioral choice: toggling between the math problems and the media (videos or Tetris). See Figure 2. We totaled the number of correct math responses in each block. In a separate validation study, five blocks were administered and boredom was assessed after each. A large increase in self-reported boredom occurred between the first block and the second, a significant difference, t(1019) = 4.69, p < .001, and boredom appeared to level-off after that. Therefore in the present study, values from Block 2, the more boring of the two blocks, were used in analyses. The same overall pattern of results and level of statistical significance was found when Blocks 1 and 2 were averaged and analyzed as a single metric.3

Finally, to ensure that the task elicited boredom as expected, one question assessed boredom on the math problems, immediately after Block 2: “How bored were you when working on the math problems?” (Response options: Not bored at all, A little bored, Somewhat bored, Very bored, Extremely bored; scoring: 1-5).

College persistence

College enrollment data were obtained from the National Student Clearinghouse (NSC), which is a non-profit database that reports on students receiving financial aid to both private and federal loan providers (Dynarski, Scott-Clayton, & Wiederspan, 2013). Colleges submit student names to this database, and so it allows for objective, longitudinal assessment of student behavior with little or no missing data. In the present study, a value of 1 indicates that students were still enrolled at a four-year college during the Fall of 2013 after the “census date” (the date after which students owe tuition, normally 4-8 weeks into the term). A value of 0 means that they did not have an official enrollment value in the database at that time. Possible reasons for not being enrolled in the Fall include students who were admitted to a college but did not ever appear at their college in the Fall, or students who appeared at their college but withdrew during the semester.4

Initial analyses support the interpretation that college persistence was indeed meaningfully affected by self-regulation. The number of boring math problems solved during the diligence task positively predicted college persistence six to ten months later, OR = 1.006, Z = 4.05, p < .001 (r = .14), and the number of tempting videos or games consumed negatively did so, OR = .91, Z = 2.09, p = .036 (r = −.08). This was true even controlling for cognitive ability (measure described below). Thus college persistence was at least one informative variable for assessing theory regarding longitudinal behavioral self-regulation.

Cognitive ability

To rule out the alternative hypothesis that observed correlations between variables were due to shared variance in cognitive ability, we administered a brief (10-item) set of moderately-challenging problems from Raven’s progressive matrices (Raven, Raven, & Court, 1998). We used a sub-set of items rather than the full battery due to time limitations in the school setting. Although brief, this set of items showed substantial convergent validity with other measures of cognitive ability in a validation study that administered a full battery of IQ measures to a sub-sample of the present study’s participants (see online supplement).

Results

Our primary hypothesis was that a greater endorsement of self-transcendent motives for going to college would predict 1) the tendency to view tedious academic tasks in a more personally-meaningful fashion, and 2) the tendency to display greater academic self-regulation. Analyses focus first on the concurrently-measured variables, followed by the analysis of the longitudinal behavioral outcome: college persistence. Our secondary hypothesis was whether individual differences in the endorsement of the self-oriented motives showed the same pattern as the self-transcendent motives.

Concurrent measures

When inspecting zero-order correlations (Table 1), students who reported more of a self-transcendent purpose for learning also scored higher on the meaningfulness of schoolwork measure, r = .23, p < .001, conceptually replicating past research (Yeager & Bundick, 2009) but with a novel and more theoretically-precise measure. A self-transcendent purpose for learning also predicted more grit, r = .39, p < .001, more academic self-control, r = .33, p < .001, and showed a modest correlation with a greater number of boring math problems solved in the face of tempting media, r = .09, p < .01.

Supplementary analyses of survey questions asked after the diligence task help clarify those results. Students who endorsed a self-transcendent purpose for learning did not perceive the single-digit subtraction problems as less boring, r = −.02, p = .47. Furthermore, 91% of participants reported at least some boredom, and 72% were “Extremely,” “Very,” or “Somewhat” bored. Thus the task was indeed boring. Yet those with more of a purpose solved somewhat more math problems despite the boredom (also see Grant & Sonnentag, 2010).

The overall correlations with measures of self-regulation were maintained when controlling for potential confounding variables in a multiple regression: self-oriented, intrinsic motives for learning (e.g., exploring your interests), extrinsic motives for going to college (e.g., making more money), as well as sex, race and ethnicity, and cognitive ability. Regression models are shown in Table 2. Inspecting the standardized regression coefficients in Table 2 shows that a self-transcendent purpose for learning predicted greater personal meaningfulness of schoolwork, β = .15, p < .001, grit, β = .27, p < .001, academic self-control, β = .29, p < .001, and the number of correctly-solved boring math problems, β = .09, p = .01. In this multiple regression, a self-oriented, intrinsic motive for learning did not significantly predict number of math problems solved (see row 2 in Table 2), and it was a significantly weaker predictor of reported grit and self-control compared to a purpose for learning, Wald test of equality of coefficients, F(1,1349) = 4.74, p = .03.

Table 2.

Ordinary Least Squares Regressions Predicting Construal and Academic Self-regulation in Study 1

| Dependent measure |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meaningfulness of schoolwork |

Grit |

Self-control |

Number of boring math problems solved during the diligence task |

|||||||||

| Predictor | β | t | p = | β | t | p = | β | t | p = | β | t | p = |

| Self-transcendent motives (“Purpose for learning”) |

.15 | 4.06 | .00 | .27 | 7.04 | .00 | .29 | 7.05 | .00 | .09 | 2.59 | .01 |

| Self-oriented, intrinsic motives | .09 | 2.74 | .01 | .10 | 2.63 | .01 | .09 | 2.45 | .01 | .01 | 0.41 | .68 |

| Extrinsic motives | −.10 | −3.50 | .00 | −.09 | −3.04 | .00 | −.10 | −3.47 | .00 | −.11 | −3.58 | .00 |

| Cognitive ability | −.07 | 2.78 | .01 | −.10 | −2.49 | .01 | −.02 | −.34 | .73 | −.02 | −.34 | .73 |

| Sex | −.02 | −.76 | .45 | −.10 | −4.25 | .00 | −.05 | −1.87 | .06 | −.05 | −1.87 | .06 |

| Ethnicity | −.07 | −2.61 | .01 | −.11 | −4.21 | .00 | −.10 | −3.75 | .00 | −.10 | −3.75 | .00 |

|

| ||||||||||||

| Adjusted R2 | .07 | .20 | .13 | .09 | ||||||||

| N | 1360 | 1358 | 1358 | 1234 | ||||||||

Note: β = standardized regression coefficient. Sex: 1 = Female, 0 = Male; Ethnicity: 1 = Hispanic /Latino, 0 = Non-Hispanic

Note that these analyses do not show that self-oriented motives are unimportant. Almost all participants who reported at least some self-transcendent motives (e.g., at or above the scale midpoint) also expressed at least modest levels of intrinsic, self-oriented motives (also at or above the scale midpoint; also see Yeager et al. 2012). Nevertheless, more strongly endorsing a self-oriented motive was not related to individual differences self-regulation. By contrast, in a sample of adolescents with at least some level of self-oriented motivation, greater endorsement of self-transcendent motives consistently predicted greater self-regulation.

Finally, zero-order correlations showed that intuitively appealing extrinsic self-oriented motives such as making money in a future job were significant positive predictors of meaningfulness of schoolwork and trait-level self-regulation (Table 1). However this appeared to be due to shared variance with the other motives. The extrinsic self-oriented items include variance both due to a general motivation to go to college—which would be shared with the purpose items—as well as variance due to more specific extrinsic motives (making money, getting out of the house), which might not be. In regression analyses that presumably remove the former source of variance, extrinsic motives were in every case strong negative predictors of both personal meaningfulness of schoolwork and academic self-regulation (see row 3 in Table 2). That is, wanting to go to college in order to make money or get out of the house predicted significantly worse academic self-regulation, net of other motives to go to college.

Longitudinal measure: college persistence

Many factors are likely to affect whether high-school graduates follow through with their college aspirations. These include academic preparation or the need for financial aid. Yet students also face barriers that require self-regulation, such as navigating the bureaucratic difficulties of completing the paperwork for enrollment, housing, course and major selection, etc., as well as the need to take entry-level, sometimes-tedious or disconnected introductory courses (Ryu, 2012). College students also have more freedom with their time as compared to high school students, and they must freely choose to work in service of their long-term goals even as they face daily temptations to engage in social activities or consume entertaining media. Because self-regulation, in theory, should help students complete these tasks and therefore persist in college—and recall that diligence task behavior predicted college enrollment—we hypothesized that a purpose for learning might predict goal persistence across the socially, academically, and bureaucratically-difficult transition to college.

Consistent with this theoretical expectation, in a logistic regression with no covariates, a self-transcendent purpose for learning significantly predicted college enrollment, Odds Ratio (OR) = 1.40, Z = 4.82, p <. 001. Controlling for sex, race and ethnicity, cognitive ability, as well as cumulative high school grade point average (GPA), did not diminish this relation, OR = 1.40, Z = 4.62, p <. 001. Estimated values from this model are depicted in Figure 3. This figure shows that for students with responses at the bottom of the purpose scale (the lowest two out of five points), only 30% of students were still enrolled at college in the Fall immediately following high school graduation. Among students at the mid-point of the purpose scale, 57% were still enrolled in college. For students at the highest two out of five scale points, this number was even greater: 64%.5 Controlling for self-oriented, intrinsic motives for learning as well as extrinsic motives for going to college did not diminish the significant relation between a purpose for learning and college enrollment, OR = 1.34, Z = 2.77, p =. 006.6 These additional motives did not significantly predict college enrollment: self-oriented, intrinsic motives (OR = 1.10, Z = .85, p = .40) and extrinsic motives (OR = 1.11, Z = 1.05, p = .30). Wald tests comparing the sizes of these coefficients to a self-transcendent purpose for learning failed to reach statistical significance (ps = .35 and .22, respectively). Altogether, a self-transcendent purpose for learning predicted persistence toward the eventual goal of college graduation. In the full regression model, other, more self-oriented motives did not.

Figure 3. A self-transcendent purpose for learning predicts long-term persistence toward an academic goal (enrollment at a four-year college 6-10 months post-assessment, among college-going high school graduates) in Study 1.

Note: Predicted values that adjusted for cognitive ability, gender, racial minority status, and high school grade point average. All participants are high school graduates who stated that their goal was to graduate from college.

Discussion

This research was conducted with a large sample of low-income, mostly racial minority students, many of whom would be the first in their families to graduate from college. In this sample, those who expressed more of a self-transcendent purpose for learning as they were leaving high school also viewed tedious academic activities as more personally-meaningful and both reported and behaviorally displayed greater academic self-regulation. They were also more likely to continue toward their stated goal of persisting in college. These effects were independent of cognitive ability. In addition, stronger endorsement of more typical self-oriented motives did not as consistently predict greater self-regulation, suggesting that there is a unique contribution of adding more self-transcendent motives.

More generally, the results of Study 1 raise the intriguing possibility that an intervention designed to promote a self-transcendent purpose for learning might improve adolescents’ academic performance over time. We tested this in Study 2.

Study 2: A Longitudinal Intervention Experiment

Study 1 was the first to show that a self-transcendent purpose for learning could predict a tendency to display greater diligence and self-regulation on academic activities as well as greater college persistence. Although encouraging support for our theory, these correlational analyses are limited in their ability to isolate causal processes. We therefore created a novel purpose for learning intervention and assessed its effects on behavior over time. This was informed most directly by pioneering research by Hulleman and Harackiewicz (2009; also see Hulleman et al., 2008, 2010). It was also informed by past studies showing that even brief persuasive messages that alter students’ appraisals of recurring events in school can improve student achievement months or years later (Aronson, Fried, & Good, 2002; Blackwell, Trzesniewski, & Dweck, 2007; Sherman, Hartson, Binning, Purdie-Vaughns, Garcia, Taborsky-Barba, Tomassetti, & Cohen, 2013; Cohen, Garcia, Purdie-Vaughns, Apfel, & Brzustoski, 2009; Walton & Cohen, 2011; see Yeager & Walton, 2011; Garcia & Cohen, 2012). Building on this, a one-time purpose intervention might produce a shift in students’ thinking that buffers them from a loss in self-regulation when confronted with uninteresting tasks on a daily basis (cf. Grant & Sonnentag, 2010). Specifically, we hypothesized that an intervention promoting a self-transcendent purpose for learning could improve GPA in STEM courses several months later, compared to a control group that completed a neutral exercise.

Method

Participants

Participants were 338 ninth grade students at a middle class suburban high school in the Bay Area of Northern California. Exactly half were male and half were female; 60% were Asian, 28% were White, 9% were Hispanic / Latino, and 1% were African American. The present study’s population adds to Study 1’s, which showed the importance of a purpose for learning among predominately low-income students of color attending urban public schools. In the present study, poverty and poor quality instruction were not common barriers for students; only 8% percent were eligible for free or reduced-price lunch and over 85% were considered proficient in math and science on state tests. Thus it was possible to examine whether the effects of a self-transcendent purpose could generalize beyond the type of sample employed in Study 1. There was no stopping rule for data collection in the present study because all students in the school were invited to participate.

Procedures

The intervention was delivered in the school’s computer lab during the school day. Teachers directed students to a website (www.perts.net) that delivered the session via a computer. All that was required of the teachers was to keep the class orderly. The materials took less than one class period (20-30 minutes) to complete.

The school has four grading periods in the year, each producing independent grades, and each lasting one fourth of the school year. In the first week of the fourth grading period of the year (in March), students completed Study 2’s web-based self-transcendent purpose intervention or a control intervention (see below). This allowed for a test of the intervention on grades in the final quarter of the year, controlling for prior grades in the third quarter.

The intervention was delivered during an elective period, not in a math or science class. This provides a strict test of the hypothesis that students themselves could create a purposeful framework that they could apply even with no explicit associations between the intervention content and STEM course learning objectives. We made no mention to students that the purpose intervention was designed to affect their thinking or behavior—instead, it was a framed as a student survey requiring their input. No teacher at the school had access to the intervention materials (so they could not reinforce it knowingly), and they were unaware of treatment and control assignments.

Purpose for learning intervention

A number of insights informed our intervention design. First, in past qualitative research (Moran et al., 2013; Yeager & Bundick, 2009; Yeager et al., 2012) many high school students spontaneously named both self-oriented motives and self-transcendent motives. Students who did so showed the greatest improvements in terms of the meaning of their schoolwork over a two-year period (Yeager et al., 2012; for analogous research in the workplace, see Grant, 2008). Almost no adolescents (8%), however, mentioned only self-transcendent motives. We therefore expected that teens would find it implausible to only focus on the world beyond the self, especially because high school is transparently a preparation for one’s future personal academic and professional goals. Therefore the intervention asked students to connect self-transcendent aims to self-relevant reasons for learning, rather than asking them to be completely altruistic.

Next, a premise of our approach is that it is either not possible or extremely difficult to tell a teenager what his or her purpose for learning should be. Doing this could threaten autonomy, a key concern for adolescents (Erikson, 1968; Hasebe, Nucci & Nucci, 2004; Nucci, 1996). Indeed, teens commonly express reactance in response to adults’ attempts to influence their personal goals (Brehm, 1966; Erikson, 1968), rejecting adult’s suggestions—or even endorsing their opposite—to reassert autonomy (see Lapsley & Yeager, in press). Furthermore, Vansteenkiste et al. (2004) showed that autonomy-supportive framing was especially important when providing intrinsic motives for a learning task. At the same time, it may be possible to lead a teenager to reflect on and construct motives in a certain direction, in a way that leads them to develop their own self-transcendent purposes for learning (see Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009). In past research on service learning activities with adolescents, reflecting on the personal meaning of one’s past prosocial behaviors led to changes in beliefs, attitudes, and thinking styles (Eyler, 2002; Eyler & Giles, 1999). Informed by these insights, our intervention did not seek to give a personally-relevant, self-transcendent purpose to a student. Instead it sought to serve as an “enzyme” to catalyze students’ reflections about their own self-transcendent purposes for learning and facilitate connections to self-oriented motives.

More concretely, the intervention first primed students’ self-transcendent thoughts by asking them to write an open-ended essay response to a question about social injustices they found particularly egregious. The prompt was:

How could the world be a better place? Sometimes the world isn't fair, and so everyone thinks it could be better in one way or another. Some people want there to be less hunger, some want less prejudice, and others want less violence or disease. Other people want lots of other changes. What are some ways that you think the world could be a better place?

Student responses dealt with issues such as war, poverty, or politics. Some examples were “Without discrimination, there would be much less violence and war in this world” or “The hunger problem can be solved if we have proper energy sources.” With those prosocial concerns in mind, students next completed a structured reading and writing exercise.

In doing so, the intervention drew on a variety of strategies designed to be maximally persuasive without threatening autonomy (Yeager & Walton, 2011; see Aronson et al., 2002; Walton & Cohen, 2011). The intervention conveyed the social norm that “many students like you” have a self-transcendent purpose for learning. Such descriptive norms can motivate behavior change (Cialdini, Reno & Kallegren, 1990; Goldstein, Cialdini & Griskevicius, 2008; see Cialdini, 2003), especially during adolescence (Cohen & Prinstein, 2006). To create a descriptive norm, we presented results of a survey that communicated that, in addition to common motives like making money or having freedom, most students also (sometimes secretly) are motivated to do well in school in order to gain skills that can be used for prosocial ends. Survey statistics presented to participants indicated that most students were motivated to do well in high school at least in part “to gain knowledge so that they can have a career that they personally enjoy” and “to learn so they can make a positive contribution to the world.” These statistics were also designed to counteract pluralistic ignorance about the norm that people are purely self-interested (also see Grant & Patil, 2012; Miller, 1999). As in similar social-psychological interventions (e.g., Walton & Cohen, 2011), summary statistics were accompanied by representative quotes purportedly from upperclassmen at the school that reinforced the focal message. One such quote stated:

For me, getting an education is all about learning things that will help me do something I can feel good about, something that matters for the world. I used to do my schoolwork just to earn a better grade and look smart. I still think doing well in school is important, but for me it's definitely not just about a grade anymore. I'm growing up, and doing well in school is all about preparing myself to do something that matters, something that I care about.

Finally, building on self-perception and cognitive dissonance (Bem, 1972; Festinger, 1957), past research finds that when a person freely chooses to advocate for a message this can lead a person to internalize it (Aronson, 1999; Aronson et al., 2002). Therefore, students next wrote brief testimonials to future students about their reasons for learning. Specifically, students explained how learning in high school would help them be the kind of person they want to be or help them make the kind of impact they want on the people around them or society in general. Participants on average wrote 2-4 sentences. In this way, rather than being passive recipients of the intervention, students themselves authored it. This allowed students to make the message both personal and persuasive to the self (Yeager & Walton, 2011).

We conducted a pilot experiment to confirm that the self-transcendent purpose intervention could indeed promote personal meaning in school as expected by theory (Yeager & Bundick, 2009; also see Study 1). This pilot involved N = 451 high school students from 13 different high schools across the United States (extensive detail is presented in the online supplemental material). In the pilot, students were randomized to the purpose intervention or a neutral control activity (see below). Students then completed a more extended version of the Study 1 meaningfulness of schoolwork measure—the academically-oriented BIF (Figure 1; cf. Vallacher & Wegner, 1989). As expected, in this pilot the purpose manipulation led to greater personal meaningfulness of tedious academic tasks compared to a neutral control, t(446) = 2.67, p = .007, d = .25 (Control raw M = 4.78, SD = 2.53 vs. Purpose raw M = 5.39, SD = 2.41). This confirms that the purpose intervention can operate as expected, at least in the short term in the pilot sample.

Control exercise

In a control condition, participants read about and then explained how high school was different from middle school. As in the purpose condition, participants saw summary statistics, read messages purportedly from helpful upperclassman (e.g., statements discussing the differences in the number of teachers or difficulty of time management), and wrote essays about how their lives were different now compared to when they were in middle school. Thus the control exercise was age-appropriate, social, and engaging, but was devoid of the focus on motives for learning. It primarily rules out the alternative explanation that any positive and friendly message about school from older students could create a sense of connection with others and facilitate prosocial motivation.

Measures

STEM Grade point average (GPA)

The primary dependent variable was grades in STEM courses (math and science) for the fourth grading period of the year. As is common, we scored grades from individual courses on a four-point GPA scale (i.e., A = 4, A− = 3.67, B+ = 3.33, etc.) and then averaged them. We did the same for the pre-intervention grading periods. Math courses were Algebra 1, Algebra 2, or Geometry (depending on where guidance counselors placed students); all students took Biology, although some students were in more advanced Biology classes than others.

Results

Preliminary analyses

The two conditions did not differ in terms of word count of their written responses, t(319)= −.10, p = .92, suggesting that, at least along this index, the two interventions elicited similar levels of engagement with the activity. Next, students successfully responded to the prompt. Some examples for the purpose intervention condition were:

“I would like to get a job as some sort of genetic researcher. I would use this job to help improve the world by possibly engineering crops to produce more food, or something like that.”

or

“I believe learning in school will give me the rudimentary skills to survive in the world. Science will give me a good base for my career in environmental engineering. I want to be able to solve our energy problems.”

or

“I think that having an education allows you to understand the world around you. It also allows me to form well-supported, well-thought opinions about the world. I will not be able to help anyone without first going to school”

GPA analyses

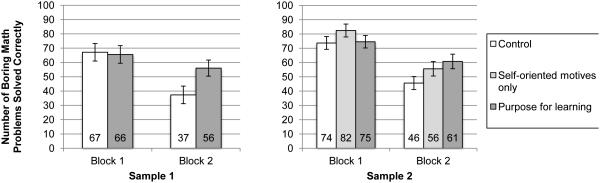

Did the purpose intervention improve overall grades in STEM-related courses (math and science)? It did, as shown in Figure 4. In an OLS regression, there was a full-sample effect of the one-time intervention on STEM-course GPA in the months following the experiment (Control covariate-adjusted M = 2.93, SD = 1.03; Purpose covariate-adjusted M = 3.04, SD = .89), t(337) = 3.20, p = .001, d = .11.7 As is standard procedure in analyses of psychological intervention effects on GPA (Blackwell et al., 2007; Cohen et al., 2009; Walton & Cohen, 2011; Yeager et al., 2014), this analysis was conducted controlling for prior performance (in the present case, third grading period grades; the same findings emerged controlling for all prior grading periods). Indeed, doing so reduced the standard errors associated with the condition variable, allowing for more precise estimates of treatment effects and maximization of statistical power.8 Additional models that added controls for race, gender, age and level of math course did not change the finding of a main effect of condition on GPA (p = .001). These control variables also did not moderate treatment effects (all interaction effect ps > .15).9

Figure 4. A self-transcendent purpose for learning intervention raises grades in math and science for all students but especially for poor performers in Study 2 (students with a GPA below 3.0 in the pre-intervention quarter).

Error bars: 1 standard error.

Under the assumption that low-achieving math and science students might be more likely to be disinterested (see, e.g., Skinner, Kindermann, & Furrer, 2009; also see Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009), we tested whether the purpose for learning would have the greatest effect on students who were earning the lowest math and science grades pre-intervention. Indeed, there was a significant Purpose intervention × Pre-intervention GPA interaction, t(338) = −2.92, p = .004, such that lower-performing students benefitted more. To illustrate this interaction, which was tested using the continuous pre-intervention GPA variable, it is possible to examine simple effects within meaningful subgroups of lower-performers (students with a GPA < 3.0) and higher-performers (GPA of 3.0 or higher). A cut-point of a GPA of 3.0 was selected for this illustration because an analysis of high school transcripts and college enrollment statistics identified this as the best GPA threshold for college readiness (Roderick, Nagaoka, & Allensworth, 2006). Among lower-performers, who are typically less likely to successfully complete college on the basis of their high school GPAs, there was a significant treatment effect of 0.2 grade points, t(119) = 2.90, p = .005, d = .21. This is shown in Figure 4. Among higher-performers, there was a non-significant effect of 0.05 grade points, t(207) = 1.38, p = .17, d = .06.

Thus, the self-transcendent purpose for learning increased STEM-course grades for students overall, but especially so for low-performers who were on track for being underprepared for higher education. This result mirrors past intervention studies, which have found that lower-performing students tend to benefit most from activities that redirect their thinking about academic work in a positive way (e.g., Cohen et al., 2009; Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; also see Wilson & Linville, 1982). It is of course possible that this moderation by baseline grades is a statistical issue; indeed, A, A−, and B+ students have less room to improve. At the same time, to the extent that lower grades could be caused by disinterest and disengagement (see, e.g., Skinner et al., 2009), the present moderation is consistent with the theory that the purpose intervention would confer the greatest benefits when disinterest and disengagement are greatest.

Discussion

Extending the Study 1 correlational findings, Study 2 showed that a self-transcendent purpose intervention could affect overall achievement in STEM courses several months into the future. How could a brief purpose intervention increase official GPA? In the next two studies we sought to illuminate some of the behavioral processes that might be set in motion by the self-transcendent purpose manipulation.

Study 3: Deeper Learning During Tedious Multiple-Choice Questions

Study 2 was a contribution in showing a causal effect of a one-time self-transcendent purpose intervention on accumulated behavior over time—specifically, GPA in high school STEM classes. It provides causal evidence for the kinds of achievement effects that may have produced the Study 1 correlational finding that purpose for learning predicted college persistence. However, a number of issues remain. Study 2 did not document which short-term behaviors were affected by the intervention and that subsequently added up to the long-term treatment effect. For instance, we do not know if a self-transcendent purpose increased overall grades by making students more likely to truly learn from their academic experiences, as opposed to moving as quickly as possible through their academic work without trying to retain the information for future use (see Jang, 2008).

Study 3 was a naturalistic field experiment conducted among undergraduates preparing for one of their final exams in their psychology course. A few days before the exam, the instructor emailed students a survey link that randomized them to a purpose intervention or a control exercise. The survey then directed students to complete a tedious (>100-question) web-based test review. Our hypothesis was that the self-transcendent purpose intervention would increase students’ attempts to seriously review the material, operationalized as the average amount of time spent on each question. Notably, the materials were presented as an actual extra-credit exercise, not as a study, in order to more closely re-create the real-world choices students might have been making in Study 2.

Method

Participants

A total of 89 second- through fifth-year students in an undergraduate psychology course received an email inviting them to access a test review and receive extra credit. A total of 71 (80%) completed the intervention materials and provided any data on dependent measures. Of these, 78% were women. There was no stopping rule because all students in the class were invited. No data were excluded.

Note that in this study (and Study 4), participants are college students, not high school students. In part this is because of our interest in understanding the processes that lead to the attainment of long-term educational goals such as college graduation (e.g., Study 1). This sample was also convenient. This difference in sample provides the benefit of possibly generalizing the prior results. It would be informative if a self-transcendent purpose for learning intervention produced analogous effects among high school freshmen (Study 2), high school seniors (Study 1), and college students (Studies 3 and 4).

Procedure

Near the end of the term, students completed the online purpose intervention and exam review activity. During the review activity, the survey software tracked students’ behavior (e.g., time spent on each practice problem) and this constituted the primary dependent measure.

More specifically, two days before an exam, students were sent the following email from their professor:

Hello class. I'm currently working on an online activity to help the students in my class do better. This online activity involves two things. First, it helps you think about how our psychology class fits into the context of your lives. Second, I've created an online activity to help you study the course material and prepare for your next exam, which involves showing you several sample multiple-choice questions that are similar to the kinds of questions that you will be tested on during EXAM 3. Since this online tool is still a work in progress, I’m offering you 2 points extra credit (to be applied to your lowest exam score) if you decide to go through it and help refine it. … [It] will take as long as you'd like--you can answer as many or as few questions as you want.

Purpose and control exercises

The self-transcendent purpose materials were highly similar to those used in Study 2. They were edited slightly to refer to reasons for learning psychology, so that the materials could conceivably be seen as related to the psychology course. The normative quotes were also framed as coming from former students in the course, as opposed to upperclassmen in general. The control exercise was highly similar to the Study 2 control group, only it discussed how learning in college is different from learning in high school. Both of these changes were made because the experiment was conducted as institutional research, which means that the goal of the study was to improve instructional practice, although the data could also be used for generalizable knowledge. And in fact the review boosted grades, dramatically so for the lowest performers across conditions (see online supplement). This ethics arrangement also had implications for random assignment. Because the research team already possessed evidence that the intervention could benefit students (e.g., Study 2) and because there were real-world grades at stake for students, for ethical reasons 75% of students received the purpose intervention and 25% received the control. Furthermore , no self-report attitudes or other psychological measures were assessed. Only students’ post-manipulation behaviors on the review materials were measured.

Measures

As a dependent measure, we created a situation that was tedious: reviewing for a test by answering over 100 multiple-choice questions. We then measured behavior that could signify an intention to truly learn from it: time spent on each review question. All questions were taken from a psychology test bank. On average, students answered 90 questions and spent 40 minutes doing so. Review questions were programmed so that students could not proceed to the next question until they answered it correctly, and task instructions clearly stated that spending more time on each question—rather than just guessing randomly until they got it right and could move on—signaled a desire for deeper learning. The instructions were:

IMPORTANT: HOW TO ACTUALLY LEARN FROM THESE QUESTIONS

New cognitive psychology research shows that simply guessing on multiple-choice questions does not promote deep learning on the activity, because it doesn't force you to retrieve the information…. So, if you want to deeply learn from this activity, it is best to look through your notes and the textbook and try to recall the information while answering the questions, as if you were really taking an important exam.

Students were also given web links to actual published empirical articles showing that memory is improved only by earnest retrieval behaviors. Thus, we created a situation in which the longer students thought about each question before trying to answer it, and the longer they spent clarifying their understanding before moving on, the more they were choosing to “learn deeply” from the activity. We conducted a number of additional analyses to confirm this theoretical interpretation of the data, and they are reported in the online supplement.

The survey software recorded the number of milliseconds that each question was displayed before students ultimately submitted a correct answer. These values were summed and then divided by the number of questions attempted, to produce an average time per question per person. Treatment versus control students did not differ in terms of the number of questions students completed, p = .38, but the effect was in the direction of treated students completing more problems (see online). As is common in analyses of time, our measure showed significant skew and kurtosis (joint test p < .00001). We therefore conducted a “ladder of powers” analysis (Tukey, 1977) to identify the transformation that best reduced deviation from normality (it was one divided by the square root of the number of seconds). The ladder analysis and subsequent transformation were done blind to the effect of the transformations on the significance of the intervention effect. The transformed measure had no significant skew or kurtosis, joint test p = .90. Time was ultimately coded so that higher numbers corresponded to more time on average on each page, and then z-scored to have a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. All analyses are from regressions that control for prior test performance, which significantly predicted time per page and reduced standard errors associated with treatment effects.

Results

Results showed that a self-transcendent purpose for learning increased the tendency to attempt to deeply learn from the tedious academic task. Students who completed the self-transcendent purpose intervention spent more time working on each review question (Z-scored time per question: Control M = −0.43, SD = 1.11; Purpose M = 0.13, SD = 0.93), t(69) = 2.11, p = .038, d = .56. In the untransformed data, this corresponded to spending roughly twice as much time on each question (Control M = 25 seconds per question vs. Treatment M = 49 seconds per question).10

Discussion

Study 3 investigated one of the short-term behaviors that might have led to the long-term effects of a purpose in Study 2: deeper learning on a tedious exam review. Students spent twice as long on their review questions when they had just written about how truly understanding the subject area could allow them to contribute to the world beyond the self, compared to controls. Importantly, this was done in a naturalistic setting—that is, looking at real world student behavior on an authentic examination review. Perhaps the purpose intervention increased grades over time in Study 2 because it led students to complete their academic work in a qualitatively distinct fashion—one that privileged learning and retention over “getting through it.”

Study 4: Working Hard in the Face of Temptations

The findings from Study 3 suggest one way in which a one-time self-transcendent purpose intervention might have increased overall grades in STEM courses in Study 2: deeper learning during review activities. However we have not shown that the purpose manipulation altered students’ abilities to regulate their competing desires. That is, we have not shown effects in situations that clearly require self-regulation. To begin to answer this, a more precise behavioral test is required—one that pits the desire to meet one’s learning goals against the desire to give up and engage in a tempting alternative.

Therefore Study 4 examined behavior on the “diligence task” described in Study 1 (also see Figure 2). This task simulates a common experience for students: having to complete problem sets for math and science classes while being tempted to consume entertaining media on the Internet. Thus, the present study allowed for a face-valid test of our hypothesis that a self-transcendent purpose for learning could lead students to continue to solve math problems and eschew tempting alternatives even as boredom is increasing.

Second, it would be helpful to know if a self-transcendent purpose could benefit all learners, but especially when a task is most uninteresting. Therefore, instead of examining between-person differences that might moderate treatment effects, as in Study 2, Study 4 focused on within-person differences. That is, Study 4 examined whether the purpose manipulation would lead to more math problems solved on the later trials of the diligence task, when boredom is greatest.

Study 4 was primarily designed to address these two research questions. However a third objective was to test whether simply emphasizing the self-oriented benefits of learning in school would be sufficient to promote academic self-regulation. Recall that Studies 2 and 3 compared the purpose manipulation to a neutral control exercise, something that has often been done in many past social-psychological interventions that have affected long-term educational outcomes (e.g., Hulleman & Harackiewicz, 2009; Walton & Cohen, 2011). Yet it is unknown whether an analogous self-oriented manipulation would show the same benefits as the purpose manipulation. While Study 1 is helpful in showing the unique correlational effect of a self-transcendent purpose, an analogous experimental study has not been conducted. To address this, in the second of the two samples included in the present study we added a self-oriented condition, making it a three-cell design. We hypothesized that the self-oriented condition would not be sufficient to lead to higher numbers of math problems solved when boredom was greatest, as compared to controls. We did not have a strong prediction about the comparison between the self-oriented condition and the purpose condition, however, because the former was intentionally designed to share much of the same content, and because past research has found these two groups do not differ significantly (Yeager et al., 2012; also recall the inconsistent Wald test results in Study 1).

Method

Participants

Participants (total N =429) were two samples of students taking introductory psychology at the University of Texas at Austin in consecutive semesters. They participated in exchange for partial course credit. Forty-eight percent were male and 52% were female. Race and ethnicity information was not collected from these students; however, the freshmen cohort at the university (which historically closely mirrors introductory psychology) is 57% White, 18% Asian, 17% Hispanic / Latino, and 5% African American. Students were predominately first or second year students: 37% were 18 years old, 36% were 19 years old, and 15% were 20 years old. Data were collected during daytime hours in the last few days of the semester, a time when self-regulation might have been precarious due to final exams.

Sample 1 had no stopping rule. We sought to collect as much data as possible (final n = 117) before the end of the term, and data were not analyzed until after the term was over. Sample 2 was collected the following semester and so it was possible to conduct a power analysis based on the results of Sample 1 before collecting data. This led to a target sample size of 300 for Sample 2, because a power analysis revealed that roughly 95 participants per cell would be required to have 80% power to detect an effect of d = .41 between any two conditions (the effect size estimate for the purpose intervention from Sample 1). Ultimately Sample 2 involved usable data from a maximum of n = 312 students (data collection was stopped at the end of the first day on which more than 300 complete responses had been collected). Some students did not provide data for some measures, and so degrees of freedom varied across analyses. No data were excluded except for those mentioned here or in the online supplement.

Procedures

The intervention procedures were nearly identical to those used in Study 3. Immediately after completing the intervention materials, participants completed the diligence task as described in Study 1.

Purpose and control exercises

These were nearly identical to those used in Study 2.

Self-oriented control exercise

Sample 2 had a three-cell design that added a self-oriented (and intrinsic) condition to the control and self-transcendent purpose conditions. The self-oriented manipulation was similar to the purpose manipulation in nearly every way except for the elimination of self-transcendent prompts in the stimuli. It was future-oriented, goal-directed, and highly focused on learning and on developing skills—all things expected by theory to promote a commitment to learning (e.g., Lepper et al., 2005; Ryan & Deci, 2000; Vansteenkiste et al., 2006). This is a highly conservative test in that the manipulations shared much of the same content—approximately 90% of the text was the same. Also recall that Study 1 indicated that self-transcendent and self-oriented motives were strongly correlated, r = .66. The present self-oriented control group was designed to rule out the alternative explanation that any manipulation involving reading and writing about intrinsic personal motives for learning would be sufficient to lead to greater self-regulation on an uninteresting task.

In the self-oriented exercise, an initial essay question asked about changes in the world. This held time-perspective and counterfactual thinking constant, both shown to affect level of construal, which could promote self-regulation (Trope & Liberman, 2010; 2011). However this prompt asked how the world might be changed to benefit the self, rather than to address an injustice in the world:

How could the world be better for you? Sometimes the world isn't what you want it to be, and so everyone thinks it could be better for them in one way or another. Some people want more fun, some want it to be less stressful, and others want to be more interested in what they’re doing. Other people want lots of other changes. What are some ways that you think the world could be better for you?

All but one of the summary statistics and all but one of the representative quotes were identical across conditions. For the one quote that was not the same, we removed self-transcendent information without sacrificing a focus on building skills, so that it read:

"For me, getting an education is all about learning things that will help me do something I can be good at—something that I can be the best at. I used to do my homework just to earn a better grade and look smart. I still think doing well in school is important, but for me it's definitely not just about a grade anymore. I'm growing up, and doing well in school is all about preparing myself to do a job that I can be good at. That seems really rewarding to me—knowing that at the end of the day you completed an important job, and you did an awesome job at it” (differences from the quotation in Study 2 shown in italics).

Next, participants were asked to share their own testimonials. The prompt closely mirrored the purpose condition and strongly emphasized the acquisition of skills (rather than the accumulation of extrinsic benefits). It asked “Why is learning important to your goals”, and “How will learning in school help you be the kind of person you want to be and help you have a career in life that you enjoy or are interested in?” It was designed to promote a suite of self-oriented motives, including task value (i.e., personal interest) and utility value (i.e., gaining a fulfilling career; Eccles & Wigfield, 1995, 2002). Supplementing this was a clear invocation of mastery goals for learning (Elliot & McGregor, 2001). All of these motives, on their own, might be expected to promote persistence. Yet this manipulation lacks explicit mention of the potential to use that mastery to benefit others, allowing for a test of our theory regarding the benefits of adding self-transcendent motives, above and beyond this suite of more self-oriented motives.

Measures

Participants completed the same behavioral measure of academic self-regulation (i.e., the diligence task) that was used in Study 1 (see Figure 2). As in Study 1, we analyzed the total number of correct math responses.11 Performance on each of the two blocks was analyzed separately to allow for a test of whether self-regulatory benefits would be greatest when boredom had increased. To verify the extent to which the task was boring for participants in all conditions, at the end we asked participants whether the task was in fact boring, using the same item described in Study 1.

Results

Analytic plan