Abstract

INTRODUCTION

This paper reviews the current status of the Clinical Core of the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), and summarizes planning for the next stage of the project.

METHODS

Clinical Core activities and plans were synthesized based on discussions among the Core leaders and external advisors.

RESULTS

The longitudinal data in ADNI2 provide natural history data on a clinical trials population and continue to inform refinement and standardization of assessments, models of trajectories, and clinical trial methods that have been extended into sporadic preclinical AD.

DISCUSSION

Plans for the next phase of the ADNI project include maintaining longitudinal follow-up of the normal and MCI cohorts, augmenting specific clinical cohorts and incorporating novel computerized cognitive assessments and patient-reported outcomes. A major hypothesis is that AD represents a gradually progressive disease that can be identified precisely in its long pre-symptomatic phase, during which intervention with potentially disease-modifying agents may be most useful.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, cognitive assessment, amyloid

INTRODUCTION

Since its inception in 2004, the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) has been advancing the standardized assessment of cognitive, clinical and biomarker measures of disease progression in cohorts of individuals who are clinically normal or have mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. The Clinical Core is been responsible for regulatory oversight, central recruitment efforts, site management, data capture, monitoring and tracking, supply management, safety monitoring and clinical guidance of the project [1, 2].

Operational activities of the ADNI Clinical Core

The current ADNI2 grant period included plans to continue the longitudinal follow-up of subjects from the earlier ADNI phases, as well as recruitment of new participants into the normal cohort (n=150), early mild cognitive impairment (EMCI, n= 100 to be added to 200 enrolled in ADNI-GO), late mild cognitive impairment (LMCI, n=150), and mild dementia (n=150). The EMCI group was differentiated from the LMCI group by virtue of degree of memory impairment. The EMCI participants were recruited with memory function approximately 1.0 SD below expected education adjusted norms while the LMCI participants were approximately 1.5 SD below expectation. In addition, during the course of ADNI2, an additional cohort was added: individuals who are clinically normal but with subjective memory concerns (SMC, n=100); for entry into the SMC cohort, a score of 16 or greater on the first 12 questions of the Cognitive Change Index[3] was required. All enrollment targets were met or exceeded, with 780 new participants along with 391 individuals followed from ADNI1 and ADNI-GO for a total of 1171 participants in ADNI2.

Adverse events are captured in the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study (ADCS) electronic data capture system, and reported on a quarterly basis to the ADCS Data and Safety Monitoring Board. To date there have been over 5000 adverse events, and over 400 serious adverse events occurring in ADNI2 participants. The majority are unrelated to study participation. The most common adverse events that have been considered to be related to the study are headaches occurring in about 4% of participants following lumbar puncture.

Baseline data for the ADNI2 cohorts are shown in Table 1. Baseline assessments are displayed graphically in Figure 1.

Table 1. Newly enrolled ADNIGO and ADNI2 subjects by Baseline Diagnosis.

Count (%) or mean (SD). P-values are from F-tests and Pearson Chi-square tests. CN: clinically normal; SMC: clinically normal with subjective memory concerns.

| N | CN (N=184) | SMC (N=103) | EMCI (N=301) | LMCI (N=160) | AD (N=145) | Combined (N=893) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 893 | 73.4 (6.3) | 72.2 (5.6) | 71.3 (7.4) | 72.2 (7.5) | 74.6 (8.1) | 72.5 (7.2) | <0.001 |

| Age: <60 | 893 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (4%) | 9 (5%) | 6 (4%) | 28 (3%) | <0.001 |

| 60–69 | 43 (23%) | 38 (37%) | 113 (38%) | 40 (25%) | 27 (19%) | 261 (29%) | ||

| 70–79 | 103 (56%) | 55 (53%) | 126 (42%) | 85 (53%) | 70 (48%) | 439 (49%) | ||

| 80–89 | 37 (20%) | 9 (9%) | 50 (17%) | 26 (16%) | 38 (26%) | 160 (18%) | ||

| >90 | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (3%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Sex: Female | 893 | 94 (51%) | 61 (59%) | 132 (44%) | 74 (46%) | 59 (41%) | 420 (47%) | 0.027 |

| Education | 893 | 16.5 (2.5) | 16.7 (2.6) | 16.0 (2.7) | 16.5 (2.6) | 15.8 (2.7) | 16.3 (2.6) | 0.005 |

| Marital: Married | 893 | 125 (68%) | 69 (67%) | 228 (76%) | 115 (72%) | 126 (87%) | 663 (74%) | <0.001 |

| Widowed | 25 (14%) | 13 (13%) | 21 (7%) | 21 (13%) | 13 (9%) | 93 (10%) | ||

| Divorced | 26 (14%) | 11 (11%) | 35 (12%) | 19 (12%) | 5 (3%) | 96 (11%) | ||

| Never married | 8 (4%) | 10 (10%) | 13 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 35 (4%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 6 (1%) | ||

| Ethnicity: Unknown | 893 | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (1%) | 0.14 |

| Not Hisp/Latino | 171 (93%) | 99 (96%) | 286 (95%) | 158 (99%) | 137 (94%) | 851 (95%) | ||

| Hisp/Latino | 12 (7%) | 2 (2%) | 14 (5%) | 2 (1%) | 7 (5%) | 37 (4%) | ||

| Race: Asian | 893 | 5 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 5 (3%) | 15 (2%) | 0.24 |

| Am Indian/Alaskan | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Hawaiian/Other PI | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (0%) | ||

| Black | 14 (8%) | 3 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 6 (4%) | 6 (4%) | 36 (4%) | ||

| White | 162 (88%) | 97 (94%) | 279 (93%) | 151 (94%) | 132 (91%) | 821 (92%) | ||

| More than one | 2 (1%) | 3 (3%) | 6 (2%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (1%) | 14 (2%) | ||

| Unknown | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0%) | ||

| CDR-SB: 0 | 893 | 173 (94%) | 88 (85%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 261 (29%) | <0.001 |

| 0.5 | 10 (5%) | 15 (15%) | 89 (30%) | 25 (16%) | 0 (0%) | 139 (16%) | ||

| 1–1.5 | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 138 (46%) | 67 (42%) | 5 (3%) | 211 (24%) | ||

| 2–2.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 61 (20%) | 40 (25%) | 20 (14%) | 121 (14%) | ||

| 3–3.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (3%) | 24 (15%) | 23 (16%) | 57 (6%) | ||

| 4–4.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (1%) | 3 (2%) | 34 (23%) | 40 (4%) | ||

| >4.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 63 (43%) | 64 (7%) | ||

| CDR Memory: 0 | 893 | 184 (100%) | 103 (100%) | 1 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 289 (32%) | <0.001 |

| 0.5 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 288 (96%) | 125 (78%) | 15 (10%) | 428 (48%) | ||

| 1 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 12 (4%) | 34 (21%) | 115 (79%) | 161 (18%) | ||

| 2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 14 (10%) | 14 (2%) | ||

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (0%) | ||

| ADAS-Cog 13 | 889 | 9.2 (4.5) | 8.9 (4.3) | 12.7 (5.4) | 18.7 (7.1) | 31.0 (8.4) | 15.5 (9.6) | <0.001 |

| MMSE | 893 | 29.0 (1.3) | 29.0 (1.2) | 28.3 (1.6) | 27.6 (1.8) | 23.1 (2.1) | 27.6 (2.6) | <0.001 |

| Participant ECog | 890 | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.3) | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.6) | 1.7 (0.5) | <0.001 |

| Study Partner ECog | 887 | 1.2 (0.3) | 1.3 (0.3) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.9 (0.7) | 2.7 (0.7) | 1.7 (0.7) | <0.001 |

Figure 1.

Baseline Assessments by Diagnosis. CN: clinically normal; SMC: subjective memory concerns; EMCI: early mild cognitive impairment; LMCI: late mild cognitive impairment; AD: mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia; ADAS13: 13 item version of the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale; MMSE: mini-mental state examination; ECog: measurement of everyday cognition.

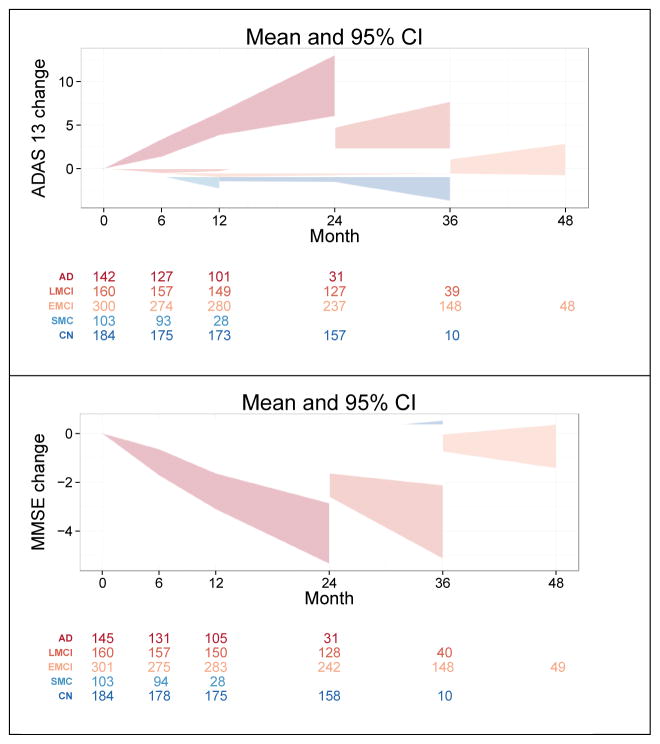

In general, the groups of participants progressed in an expected fashion. Cognitive progression by cohort is shown in Figure 2. The CN group progressed to MCI at a rate of approximately 3.6% per year while the EMCI developed dementia at a rate of 2.3% and LMCI participants went on to dementia at a rate of 17.5% per year.

Figure 2.

Mean Change by baseline diagnosis. Shaded areas represent 95% Confidence intervals. Number of observations for each cohort at each time point are shown below the graphs. CN: clinically normal; SMC: subjective memory concerns; EMCI: early mild cognitive impairment; LMCI: late mild cognitive impairment; AD: mild Alzheimer’s disease dementia; ADAS13: 13 item version of the cognitive subscale of the Alzheimer’s Disease Assessment Scale; MMSE: mini-mental state examination.

The discontinuation rates of subjects in the various clinical groups has been reasonably low, at 6–10% per year. The continued participation of the subjects has been a testimonial to their dedication to the project.

Academic aims of the Clinical Core

Apart from its operational mission, the Clinical Core pursues academic goals: utilizing ADNI data to study the course of the disease and to advance clinical trial methodology. These goals include optimization of outcome measures, evaluation of statistical analysis approaches, development of new trial designs, refinement of models of disease trajectories and staging, and clinical features of AD.

Work on outcome measures ranges from standard cognitive assessments to novel instruments. An important study of ADAScog items clarified the impact of the delayed recall component at specific stages of disease [4]. New instruments were described for use as endpoints in preclinical phase studies [5, 6]. Also using ADNI data, the added efficiency of continuous outcomes as opposed to categorical endpoints in prodromal AD trials was quantified [7] and mixed models were compared to slope-based analyses [8]. A novel approach to generating long-term trajectories from relatively short-interval ADNI data was used to test hypotheses proposed in the Jack models [9](see also Biostatistics Core paper in this issue).

The clinical and biomarker characterization and outcome of mild cognitive impairment (MCI) has continued [10]. Participants in ADNI diagnosed with late MCI were followed longitudinally and classified by their biomarker profiles. Their frequency of biomarkers and outcomes were compared with a group of community participants from the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. The participants were classified on their amyloid status as well as features of neurodegeneration such as hippocampal atrophy or FDG PET hypometabolism. A group of participants designated as MCI SNAP (suspected non-AD pathology) was described since they had no evidence of amyloid on imaging but had features of neurodegeneration. These participants progressed to dementia at rates similar to those with the presence of amyloid and neurodegeneration. These findings will be pursued in ADNI 3 (see below) with the advent of tau imaging to further characterize neurodegeneration.

Among individuals with MCI, those with subsyndromal symptoms of depression show faster rates of conversion to dementia and significantly greater levels of disability compared to MCI participants without symptoms of depression [11]. These results suggest that even very mild depressive symptoms in older adults may be accompanied by neurodegenerative brain changes which impact cognitive decline and functional status. Additionally, biochemical biomarkers of depressive symptoms in older adults may be useful in investigations of pathophysiological mechanisms of depression in aging and neurodegenerative dementias and as targets of novel treatment approaches [12]. Based on such observations, a new study (Depression-ADNI) has been launched with NIA funding to characterize biomarker trajectories associated with depressive symptoms in older individuals.

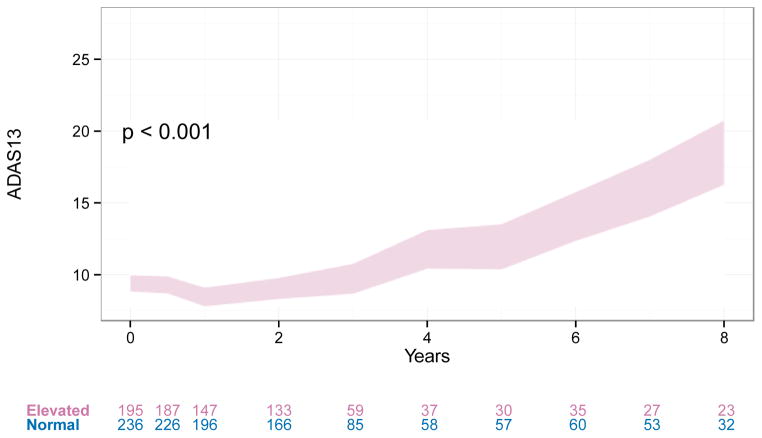

Among the highest impact efforts from the ADNI Clinical Core investigators has been the development of the first trial design for studies conducted in the preclinical, asymptomatic stage of sporadic AD [13]; the design was based in part on the observation in ADNI that the presence of elevated brain amyloid in clinically normal individuals distinguished those that will decline cognitively from those that will remain stable (Figure 3.). This design has now been implemented in the A4 (Anti-Amyloid treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s) trial that is under way, and will be the basis for another pivotal trial to be launched later this year. In the A4 trial, clinically normal individuals aged 65 or older are screened with an amyloid PET scan; those who have elevated brain amyloid qualify for randomization into a three year randomized placebo-controlled trial of anti-amyloid immunotherapy, with a cognitive measure [5] as the primary outcome. If this trial successfully demonstrates that anti-amyloid treatment slows cognitive decline in the individuals, it may lead to regulatory approval of the first therapeutic for the secondary prevention of the clinical manifestations of AD. In essence, analysis of ADNI clinical, cognitive and biomarker data were vital in facilitating a new phase in drug development for AD.

Figure 3.

Long-term ADAS13 trajectories of CN or SMC with and without elevated amyloid. Trajectories are modeled using a categorical time mixed model of repeated measures with covariates for APOEε4, age, gender, education, and ventricular volume at baseline. All of these covariate effects were significant at 0.05 level except APOEε4. Age, gender, and education were highly significant (p <0.001). Trajectories are similar when we only control for age.

Future aims of the Clinical Core

In the application for the next phase of ADNI, ADNI3, the Clinical Core will continue to be responsible for the operational management of the project: data management, tracking and quality control, recruitment and retention of participants, regulatory oversight and financial management. Clinical Core investigators will continue work on the characterization of the cross-sectional features and longitudinal trajectories of cognitively normal older individuals and mild cognitive impairment, study of the relationships among clinical/demographic, cognitive, genetic, biochemical and neuroimaging features of AD from the preclinical through dementia stages, and assessment of genetic, biomarker and clinical predictors of decline. Refinement of clinical trial designs, including secondary prevention, slowing of progression in symptomatic disease, and cognitive/behavioral management, will continue to be a primary focus.

Toward these aims, the ADNI3 phase would maintain the longitudinal follow-up of the current ADNI2 pre-dementia cohorts (normals with and without subjective memory concerns, and early and late mild cognitive impairment). We estimate that approximately 700 ADNI2 subjects will remain in ADNI3. Additional recruitment will allow enrollment of new participants, to an approximate total number of 900 participants at the clinically normal (CDR=0, aged 65 and older, with or without memory concerns), mild cognitive impairment (CDR=0.5, MMSE 24–30, logical memory scores at least 1.0 to 1.5 standard deviations below education-adjusted norms) and mild AD dementia stages (CDR 0.5-1, MMSE 20-26).

Most of the cognitive and clinical assessments of ADNI2 will continue. In addition, there will be a particular focus on computerized cognitive assessment (now being piloted in ADNI2), as well as patient-reported outcomes. The computerized instrument, CogState is being introduced in a pilot study in ADNI2 and will likely be included in ADNI3. CogState involves four tests largely assessing psychomotor speed and working memory using a playing card format. The participants perform simple reaction time, choice reaction time, and two working memory tasks in approximately 15 minutes. These tasks have been shown to be sensitive to change over time while minimizing any practice effects. If successful, these tasks will be given to participants in ADNI3 to track their performance over time. Eventually these tasks can be performed by the participants in their homes and the data will be transmitted to the Clinical Core of ADNI.

The Clinical Core will continue its efforts to advance AD therapeutic trial design. Continued characterization of early phase disease will be a focus, including confirmation of the hypothesis that brain amyloid deposition in clinically normal older individuals identifies a population that will progress to the symptomatic stages of AD. The inclusion of patient-reported outcomes and web-based computerized assessments will add potential outcomes for preclinical trials. Webbased cognitive assessment may also provide a means for selection of candidates for early stage trials, perhaps including primary prevention studies.

Research in Context.

Systematic review: The content of this report is based on discussions among the ADNI Clinical Core leaders and review of the relevant scientific literature.

Interpretation: The Clinical Core continues to provide operational support to ADNI, and has elucidated clinical and biomarker features of the disease course facilitating major advances in trial design.

Future directions: Continued longitudinal follow-up of existing participants, recruitment of new cohorts, and additional of novel cognitive and clinical assessments will support further advances to our understanding of the disease course and optimal therapeutic interventions.

Footnotes

Conflicts

Data collection and sharing for this project were funded by the Alzheimer's Disease

Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s

Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; BioClinica, Inc.;

Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; EuroImmun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company

Genentech, Inc.; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; ; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck & Co., Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Paul S. Aisen, Department of Neurosciences, University of California San Diego.

Ronald C. Petersen, Department of Neurology, Mayo Clinic.

Michael Donohue, Department of Family Medicine and Public Health, Division of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, University of California San Diego.

Michael W. Weiner, Departments of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, Medicine, Psychiatry and Neurology, University of California San Francisco.

References

- 1.Aisen PS, Petersen RC, Donohue MC, Gamst A, Raman R, Thomas RG, Walter S, Trojanowski JQ, Shaw LM, Beckett LA, et al. Clinical Core of the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative: progress and plans. Alzheimer's & dementia : the journal of the Alzheimer's Association. 2010;6:239–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Harvey DJ, Jack CR, Jr, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Toga AW, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181cb3e25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saykin AJ, Wishart HA, Rabin LA, Santulli RB, Flashman LA, West JD, McHugh TL, Mamourian AC. Older adults with cognitive complaints show brain atrophy similar to that of amnestic MCI. Neurology. 2006;67:834–842. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000234032.77541.a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sano M, Raman R, Emond J, Thomas RG, Petersen R, Schneider LS, Aisen PS. Adding delayed recall to the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale is useful in studies of mild cognitive impairment but not Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer disease and associated disorders. 2011;25:122–127. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f883b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Donohue MC, Sperling RA, Salmon DP, Rentz DM, Raman R, Thomas RG, Weiner M, Aisen PS, et al. for the Australian Imaging B, Lifestyle Flagship Study of A. The Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite. Measuring Amyloid-Related Decline. JAMA neurology. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Amariglio RE, Donohue MC, Marshall GA, Rentz DM, Salmon DP, Ferris SH, Karantzoulis S, Aisen PS, Sperling RA for the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative S. Tracking Early Decline in Cognitive Function in Older Individuals at Risk for Alzheimer Disease Dementia: The Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Cognitive Function Instrument. JAMA neurology. 2015 doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.3375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Donohue MC, Gamst AC, Thomas RG, Xu R, Beckett L, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen P Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. The relative efficiency of time-to-threshold and rate of change in longitudinal data. Contemporary clinical trials. 2011;32:685–693. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donohue MC, Aisen PS. Mixed model of repeated measures versus slope models in Alzheimer's disease clinical trials. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2012;16:360–364. doi: 10.1007/s12603-012-0047-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jack CR, Jr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, et al. Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer's disease: an updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers. Lancet neurology. 2013;12:207–216. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70291-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Petersen RC, Aisen P, Boeve BF, Geda YE, Ivnik RJ, Knopman DS, Mielke M, Pankratz VS, Roberts R, Rocca WA, et al. Mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer disease in the community. Annals of neurology. 2013;74:199–208. doi: 10.1002/ana.23931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackin RS, Insel P, Aisen PS, Geda YE, Weiner MW Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging I. Longitudinal stability of subsyndromal symptoms of depression in individuals with mild cognitive impairment: relationship to conversion to dementia after 3 years. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2012;27:355–363. doi: 10.1002/gps.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackin RS, Insel P, Tosun D, Mueller SG, Schuff N, Truran-Sacrey D, Raptentsetsang ST, Lee JY, Jack CR, Jr, Aisen PS, et al. The effect of subsyndromal symptoms of depression and white matter lesions on disability for individuals with mild cognitive impairment. The American journal of geriatric psychiatry : official journal of the American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry. 2013;21:906–914. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sperling RA, Rentz DM, Johnson KA, Karlawish J, Donohue M, Salmon DP, Aisen P. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Science translational medicine. 2014;6:228fs213. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]