Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Rising costs present a major threat to the sustainability of health care delivery. Resource stewardship is increasingly becoming an expected competency of physicians. The Choosing Wisely framework was used to introduce resource stewardship at a national educational retreat for infectious disease and microbiology residents.

METHODS:

During the 2014 Annual Canadian Infectious Disease and Microbiology Resident Retreat in Toronto, Ontario, infectious disease (n=50) and microbiology (n=17) residents representing 11 Canadian universities from six provinces, were invited to participate in a modified Delphi panel. Participants were asked, in advance of the retreat, to submit up to five practices that infectious disease and microbiology specialists should not routinely perform due to lack of proven benefit(s) and/or potential harm to patients. Submissions were discussed in small and large group forums using an iterative approach involving electronic polling until consensus was reached for five practices. A finalized list was created for both educational purposes and for residents to consider enacting; however, it was not intended to replace formal society-endorsed statements. A follow-up survey at two-months was conducted.

RESULTS:

Consensus was reached by the residents regarding five low-value practices within the purview of infectious diseases and microbiology physicians. After the retreat, 20 participants (32%) completed the follow-up survey. The majority of respondents (75%) believed that the session was at least as relevant as other sessions they attended at the retreat, including 95% indicating that at least some of the material discussed was new to them. Since returning to their home institutions, nine (45%) respondents have incorporated what they learned into their daily practice; four (20%) reported that they have considered initiating a project related to the session; and one (5%) reported having initiated a project.

CONCLUSIONS:

The present educational forum demonstrated that trainees can become actively engaged in the identification and discussion of low-value practices. Embedding residence training programs with resource stewardship education will be necessary to improve the value of care offered by the future members of our profession.

Keywords: Choosing Wisely, Health care resources, Health care value, Resource stewardship

Abstract

HISTORIQUE :

Les coûts croissants représentent une menace importante pour la pérennité des soins de santé. De plus en plus, on s’attend que les médecins aient les compétences nécessaires pour gérer les ressources. Lors d’une journée de réflexion nationale pour les résidents en infectiologie et en microbiologie, la gestion des ressources a été abordée conformément au cadre Choosing Wisely.

MÉTHODOLOGIE :

Pendant la journée de réflexion canadienne annuelle de 2014 pour les résidents en infectiologie et en microbiologie tenue à Toronto, en Ontario, des résidents en infectiologie (n=50) et en microbiologie (n=17) représentant 11 universités canadiennes réparties dans six provinces ont été invités à participer à un groupe Delphi modifié. Avant la journée de réflexion, ils ont été invités à soumettre jusqu’à cinq pratiques que les spécialistes de l’infectiologie ou de la microbiologie ne devraient pas effectuer systématiquement parce que leurs avantages ne sont pas démontrés ou qu’elles comportent des risques potentiels pour les patients. Ils ont examiné ces pratiques lors de forums en petits et grands groupes selon une méthode itérative par sondage électronique, jusqu’à atteindre un consensus pour cinq pratiques. Une liste définitive a été créée pour des besoins d’éducation et pour que les résidents envisagent de la respecter. Cette liste ne visait toutefois pas à remplacer les documents officiels approuvés par la Société. Un sondage de suivi a été effectué au bout de deux mois.

RÉSULTATS :

Les résidents sont parvenus à un consensus sur cinq pratiques de faible valeur qui relèvent des médecins en infectiologie et en microbiologie. Après la journée de réflexion, 20 participants (32 %) ont rempli le sondage de suivi. La majorité d’entre eux (75 %) trouvaient que cette séance était au moins aussi pertinente que les autres séances auxquelles ils avaient assisté pendant la journée de réflexion, et 95 % ont indiqué qu’au moins une partie de ce qui avait été abordé était nouveau pour eux. Depuis leur retour au sein de leur établissement, neuf (45 %) répondants avaient intégré ce qu’ils avaient appris à leur pratique, quatre (20 %) ont déclaré avoir envisagé un projet lié à la séance et un (5 %) a affirmé avoir lancé un projet.

CONCLUSIONS :

Le présent forum d’éducation a démontré que les résidents peuvent s’investir pour cerner les pratiques de faible valeur et en discuter. Il faudra intégrer la gérance de l’éducation aux programmes de résidence pour améliorer la valeur des soins offerts par les futurs membres de notre profession.

The rising cost of health care is one of the greatest threats to the sustainability and advancement of medical practice (1). Recognizing that some medical practices lack supporting evidence and may be harmful to patients, the American Board of Internal Medicine launched the Choosing Wisely campaign in 2012, which sought to empower both medical practitioners and patients to make clinical decisions that promote high-value care (2). This initiative has been adopted and adapted throughout the United States and Canada, spreading beyond internal medicine to other medical specialties. There are presently >70 societies participating in the United States and at least 30 in Canada (3). These societies have engaged members to create lists of “five things that physicians and patients should question” to begin discussions about ways to improve the value of health care (3).

While physicians must take ownership and achieve competence in the area of resource stewardship, this important aspect of physician competence has not traditionally been incorporated into medical school curricula and residency training (4). Traditionally, infectious disease specialists and microbiologists have played important roles in infection prevention and control, and antimicrobial stewardship; however, broader training and involvement in resource stewardship has generally been lacking. Extending the scope of infectious diseases and microbiology practice to include resource stewardship should be viewed as being complimentary to these existing roles.

The practice patterns of attending physicians, encountered early by learners, can have a lasting impact on the future practices of trainees (5). We believe that engaging residents in active reflection regarding the consequences of their clinical decisions and actions may have lasting effects on their future patterns of practice (5). Therefore, we sought to engage infectious diseases and microbiology residents from across Canada in developing their own statements, modelled after the Choosing Wisely campaign, to facilitate reflection and education regarding resource stewardship in infectious diseases and microbiology training and, in doing so, demonstrate a method of consensus building through facilitated discussion. It was not our intent to replace a formal Choosing Wisely initiative in infectious diseases and microbiology with official support of societies, but rather to introduce the concept at the trainee level with the hope that they would apply this knowledge to their own practices.

METHODS

During the 2014 Annual Canadian Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Resident Retreat held from August 11 to 14, 2014, in Toronto, Ontario, infectious diseases and microbiology trainees (representing 11 Canadian universities and all six provinces with training programs in infectious diseases and microbiology [British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia]) who enrolled in the retreat, were asked to participate in a modified Delphi panel (6) modelled after the Choosing Wisely initiative (Figure 1). Participants included 50 residents in infectious diseases (adult infectious diseases [n=35], pediatric infectious diseases [n=15] and microbiology [n=17]). The retreat was an educational forum organized by residents in the Adult Infectious Diseases program at the University of Toronto (Toronto, Ontario), who determined the curriculum and teaching formats for the sessions.

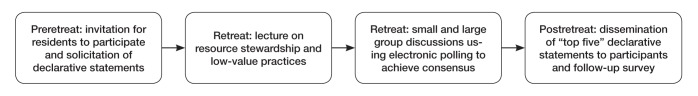

Figure 1).

Flow diagram of the educational formats and process to generate the ‘top five’ declarative statements

In advance of the retreat, attendees were asked to participate in this session beginning with reflection of both personal practice patterns and those of their attending physicians, to identify unnecessary tests or procedures falling within their own scopes of practice that could be eliminated (3). These practices were defined as those lacking proven benefit or posing potential harm to patients. A brief description of the format of the session was provided, including examples of appropriate and inappropriate submissions in the form of declarative statements (3). An example of an inappropriate recommendation included “do not routinely order urine cultures to assess patients with changes in mental status who do not have signs or symptoms of urinary tract infection”, because infectious disease physicians and microbiologists are not typically the individuals who assess these patients and order this test.

Of 67 participants from 11 Canadian universities, 18 (27%) provided submissions in advance of the session. These were formatted into 15 declarative statements by three of the authors (DRM, WLG, JAL) and were accompanied by supporting evidence. The statements were then circulated to all participants before the retreat. The 90 min session included several educational formats. A collaborative approach to this exercise was emphasized. To begin, a lecture introduced the concepts of high- and low-value health care, resource stewardship, the Choosing Wisely campaign and included a review of the list of declarative statements. The overall goal of the session was for the participants to apply the knowledge learned from the large group lecture to finalize a list of statements, which they determined to be actionable and through implementation, may improve the value of care provided. Following the large group lecture, participants were divided into small groups (eight to 10 participants per group); residents in the Adult Infectious Diseases program at the University of Toronto were responsible for facilitating discussions to arrive at consensus within each group regarding their ‘top five list’, which they presented to the group at large. The rationales for their choices were recorded. All participants were then polled in real-time using interactive polling software (www.polleverywhere.com) and a ‘top 10 list’ was created. Using a modified Delphi method (6), polling and open discussion continued through three additional rounds, until consensus was reached. This was defined as two consecutive polls without change in rank of the statements. Final statements were formalized and disseminated to all participants to both ensure integrity of the statements, and to encourage engagement of faculty and residents at their own institutions in further discussions. Two months following the retreat, participants were surveyed to obtain quantitative feedback on the impact of this session. Research ethics board approval was obtained.

RESULTS

Participants achieved consensus regarding “five things physicians and patients should question” (3) related to infectious diseases practice (Table 1). Each statement pertains to a test or procedure encountered in infectious diseases or microbiology practice for which there is an evidence base to support reducing or eliminating its use (7–11). Twenty participants (32%) completed the survey. Eighty percent of responders agreed/strongly agreed that an effective presentation style was used (55% somewhat agree; 25% strongly agree). The majority of participants (75%) believed that the session was at least as relevant as other sessions at the retreat (as relevant 55% ; somewhat more relevant 15%; more relevant 5%), with 95% indicating that at least some of the material discussed was new to them (80% somewhat new to respondent; 15% new to respondent). After returning to their home institutions, nine respondents (45%) reported they have incorporated what they learned into their daily practice. Four respondents (20%) reported that they have considered initiating a project related to the session and one respondent (5%) reported having initiated a project.

TABLE 1.

“Five things physicians and patients should question” regarding low-value practices in infectious diseases and microbiology as developed by residents in infectious diseases and microbiology

|

Do not routinely repeat CD4 measurements in patients with HIV infection who are stable on antiretroviral therapy with suppressed viral loads for >2 years. In prospective trials, among patients who have responded to antiretroviral therapy with HIV-1 RNA below 50 copies/mL and rises in CD4 cell count >200 cells/μL, there was little clinical benefit from continued measurement of CD4 cell count. The 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society – United States Panel state that measurement of CD4 is optional (7). |

|

Do not perform tuberculin skin testing for diagnostic purposes in cases of suspected active tuberculosis in adults. Tuberculin skin tests in adult patients with suspected active tuberculosis is not recommended by current guidelines because positive results may lead to unnecessary multidrug treatment when they occur in cases of latent tuberculosis, or to erroneous exclusion of tuberculosis in patients with false-negative tests (8). |

|

Do not routinely perform repeat magnetic resonance imaging for uncomplicated bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis following clinical improvement using appropriate antimicrobial therapy. In patients who are clinically improving, unless a large epidural abscess was present on initial imaging, observational studies suggest that repeat spinal imaging generally does not alter management and may lead to unnecessary prolongation of antimicrobial therapy (9). |

|

Do not routinely prescribe intravenous forms of highly bioavailable antimicrobial agents for patients who can reliably receive and absorb medications via the enteral route. Among patients who can reliably receive and absorb medications via the enteral route, there is no additional benefit of using intravenous formulations of clindamycin, fluoroquinlones, linezolid, metronidazole, tetracyclines or trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (10). Oral administration may permit more timely hospital discharge and reduce the use of intravascular catheters in both inpatient and outpatient settings. |

|

Do not routinely request transesophageal echocardiography in patients with uncomplicated Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Transesophageal echocardiography may be safely avoided in patients with S aureus bacteremia who lack several infective endocarditis risk factors. These include absence of a permanent intracardiac device, sterile follow-up blood cultures within four days after the initial set, no hemodialysis dependence, nosocomial acquisition of S aureus bacteremia, absence of secondary foci of infection and no clinical signs of infective endocarditis (negative predictive value 93% to 100%) (11). |

DISCUSSION

Through this national educational forum, we demonstrated feasibility of introducing the concept of high-value health care delivery into the curriculum of infectious diseases and microbiology trainees, through the generation of individual and peer-developed statements modelled after the Choosing Wisely campaign. The items, identified by the residents, have not been rigorously scrutinized for official endorsement by any professional society, but represent the opinions of infectious diseases and microbiology trainees who have not yet completed their training. With additional years of training and practice, other declarative statements may have been included and some excluded.

However, the primary objective of this session was to facilitate reflection and education regarding resource stewardship at the trainee level. Despite a low response rate to our postretreat survey, we demonstrated that participants who replied are contemplating or have initiated projects related to this project, which was a goal of the session.

We conclude that an interactive, educational forum modelled after the Choosing Wisely campaign was an effective way of introducing the concepts of resource stewardship to subspecialty trainees. Embedding resource stewardship in residency training curricula, as highlighted at our retreat, represents one approach that may improve the value of care offered by the future members of our profession (4).

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr Wendy Levinson of Choosing Wisely Canada for her review of the manuscript and her advice on this initiative. They thank the participants of the 2014 Canadian Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Resident Retreat for their participation in the conference, and for their thoughtful submissions and discussions relating to resource stewardship in infectious diseases and microbiology.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURES: The authors have no financial relationships or conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Curfman G, Morrissey S, Drazen J. High-value health care – a sustainable proposition. N Engl JMed. 2013 Sep 17; [Epub ahead of print] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caasel C, Guest J. Choosing Wisely – helping physicians and patients make smart decisions about their care. JAMA. 2012;307:1801–2. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levinson W, Huynh T. Engaging physicians and patients in conversations about unnecessary tests and procedures: Choosing Wisely Canada. CMAJ. 2014;186:325–6. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.131674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McMillan J, Ziegelstein R. Implementing a graduate medical education campaign to reduce or eliminate potentially wasteful tests or procedures. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1693. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.3472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Detsky A, Verma A. A new model for medical education: Celebrating restraint. JAMA. 2012;308:329–30. doi: 10.1001/2012.jama.11869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the Delphi method to the use of experts. Manage Sci. 1963;9:458–67. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gunthard H, Aberg J, Eron J, et al. Antiretroviral treatment of adult HIV infection: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society – USA panel. JAMA. 2014;312:410–25. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pai M, Minion J, Jamieson F, Wolfe J, Behr M. Canadian Tuberculosis Standards. 7th edn. Ottawa: Public Health Agency of Canada; 2014. Diagnosis of active tuberculosis and drug resistance; pp. 43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zarrouk V, Feydy A, Salles F, et al. Imaging does not predict the clinical outcome of bacterial vertebral osteomyelitis. Rheumatology. 2007;46:292–5. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control . Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2014. Core Elements of Hospital Antibiotic Stewardship Programs. < www.cdc.gov/getsmart/healthcare/pdfs/core-elements.pdf> (Accessed August 29, 2014) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holland TL, Arnold C, Fowler VG., Jr Clinical management of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia: A review. JAMA. 2014;312:1330–41. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.9743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]