Abstract

Objective

Uganda has one of the highest unmet needs for family planning globally, which is associated with negative health outcomes for women and population-level public health implications. The present cross-sectional study identified factors influencing family planning service uptake and contraceptive use among postpartum women in rural Uganda.

Methods

Participants were 258 women who attended antenatal care at a rural Ugandan hospital. We used logistic regression models in SPSS to identify determinants of family planning service uptake and contraceptive use postpartum.

Results

Statistically significant predictors of uptake of family planning services included: education (AOR = 3.03, 95 % CI 1.57–5.83), prior use of contraceptives (AOR = 7.15, 95 % CI 1.58–32.37), partner communication about contraceptives (AOR = 1.80, 95 % CI 1.36–2.37), and perceived need of contraceptives (AOR = 2.57, 95 % CI 1.09–6.08). Statistically significant predictors of contraceptive use since delivery included: education (AOR = 2.04, 95 % CI 1.05–3.95), prior use of contraceptives (AOR = 10.79, 95 % CI 1.40–83.06), and partner communication about contraceptives (AOR = 1.81, 95 % CI 1.34–2.44).

Conclusions

Education, partner communication, and perceived need of family planning are key determinants of postpartum family planning service uptake and contraceptive use, and should be considered in antenatal and postnatal family planning counseling.

Keywords: Family Planning, Contraception, Uganda

Introduction

Maternal mortality remains a significant public health concern in Uganda (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012). It is estimated that if all women in need of contraceptives in Uganda were using them, the number of maternal deaths would be reduced by 40 % (Guttmacher 2009). However, contraceptive use in Uganda is low and the unmet need for family planning is among the highest in the world (Khan et al. 2008). An unmet need for family planning refers to women capable of reproducing who are not using contraception, but wish to postpone their next birth for 2 or more years or to stop childbearing all together (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012). According to the 2012 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) data, among currently married rural women, 37 % have an unmet need for family planning and only 27 % report currently using effective contraceptives (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012). Furthermore, 44 % of pregnancies are unplanned (Guttmacher Institute 2009) and spacing between pregnancies is poor, which is associated with an increased risk of infant mortality, childhood malnutrition, and complications during pregnancy (Gribble et al. 2008; Rutstein 2008, 2011).

One important step in addressing the unmet need for family planning in Uganda is to explore factors that influence women wanting to delay their next pregnancy to use contraceptives. Prior research in developing countries has identified an array of multi-level determinants of contraceptive uptake. Examples of determinants identified at the individual-level include age, education, income, relationship status, and religion (e.g., Agyei and Migadde 1995; Okech et al. 2011; UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012), and psychosocial factors encompassed by theories of behavior change, such as one’s knowledge of contraceptive methods (Ankomah and Anyanti 2011), beliefs toward contraceptive efficacy and safety (Eliason et al. 2013; Salway and Nurani 1998), and self-efficacy toward contraceptive use (Rijsdijk et al. 2012). At the interpersonal-level, evidence supports the influence of the male partner on women’s reproductive health and decision making, especially in resource-limited settings. Gender norms and unequal power in relationships may manifest in several ways that influence a woman’s ability to use contraceptives, such as gendered sexual decision making (Nalwadda et al. 2010), norms prohibiting communication about sexual health (Kiene et al. 2013), and intimate partner violence (Hung et al. 2012). Finally, there is increasing support for the importance of contextual determinants of family planning in resource-limited settings (Stephenson et al. 2007). Health system factors associated with access to care include access to trained staff, follow-up care, cost, and the environment of health facilities (e.g., wait time, space) (Ensor and Cooper 2004; Ketende et al. 2003).

While a sizable body of research exists on determinants of family planning uptake among the general population, little is known about what factors influence women’s use of contraception postpartum. Pregnancy and the postpartum period is considered an ideal time to deliver family planning as women more regularly visit healthcare facilities during this time (Warren et al. 2010) and may be more motivated for health behavior change, having recently given birth (Phelan 2010). Given national trends of short intervals between births (Rutstein 2011), the provision of postpartum family planning (PPFP) should be prioritized in Uganda as there may only be a brief window of time to link many postpartum women to family planning services before their next pregnancy. Despite the need for increased PPFP in Uganda, there are few studies exploring contraceptive use that specifically target women postpartum. It is possible that different factors influence family planning service uptake and contraceptive use during this time period. Thus, the purpose of this study is to explore determinants of uptake of family planning services and contraceptive use among postpartum women in rural Uganda.

Theoretical framework

We used Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use (ABM) (Andersen 1968, 1995; Andersen and Newman 1973) to guide the selection of independent variables in the present study. The ABM is a multilevel model that has been used extensively to explain and predict utilization of health services (Babitsch et al. 2012). In sum, the model posits environmental (i.e., external environment and health system) and person characteristics (i.e., predisposition of people to use services, factors that enable or impede this use, a person’s perception of need for care) combine to influence health behavior (i.e., personal health practices and health service use), which influence health status outcomes (i.e., perceived and evaluated health status). In the present study, the ABM was modified to include an additional domain to encompass factors at the relationship-level. Based on the ABM and the literature reviewed, we hypothesized that the following factors would predict contraceptive use and uptake of family planning services postpartum: health system factor: time to clinic; predisposing factors: number of children, age, education, religion, depression, contraceptive knowledge, attitudes toward contraceptive use; enabling factors: income, self-efficacy toward contraceptive use, prior use of contraceptives, location of delivery; relationship factors: relationship control, dominance in decision making, perceived partner attitudes toward family planning, history of abuse, communication with partner about contraceptives, male/female differences in fertility desires; need factor: perceived need of family planning. See Fig. 1 for a depiction of the hypothesized independent and outcome variables of interest mapped onto the ABM domains.

Fig. 1.

Independent variables and outcome variables mapped on to the theoretical framework: Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use, Uganda 2010. FP family planning

Methods

The research was conducted in Butambala District, Uganda at a rural 100 bed public hospital, among postpartum women and was part of a larger study assessing the influence of male partner involvement in antenatal care (ANC) on family planning outcomes. Gombe Hospital serves a population of approximately 300,000 people with active ANC and postnatal care clinics 3 days a week, providing a comprehensive selection of contraceptive methods, including long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs) methods, free of charge. Pregnant women receiving antenatal services typically first report to ANC at their fourth month of pregnancy, returning approximately monthly until their eighth month, and subsequently every 1 or 2 weeks until their delivery. Health education delivered by nurses is one component of the ANC program, which includes a range of health topics, including family planning which is generally discussed at the eighth month visit. Six weeks postpartum, women return for postnatal care and again at 10 and 14 weeks for infant immunizations.

Participants were recruited from the ANC clinic at Gombe Hospital. Women attending ANC for their 7-month visit were informed by hospital staff about the research study and referred to a research assistant to learn more about the study. Of those offered participation, 301 enrolled in the study and 49 declined to participate. The research assistant obtained written informed consent. Women were excluded from the study if they did not meet the following criteria: (1) at least 18 years of age, (2) if the father of the current pregnancy was not living with them or nearby or if they did not have a partner (necessary for the original study’s aims), (3) if they lived further than 20 km from the hospital (for retention purposes), (4) if they were not willing to return for a follow-up interview 10 weeks post-delivery, and (5) if they were not well enough to participate as judged by hospital staff.

Participants were interviewed by a research assistant at study enrollment and again approximately 10 weeks postpartum. With the exception of demographic items collected at baseline, only follow-up data is included in the current analysis (participants not completing follow-up were excluded, n = 43), since the baseline data did not include many of the factors of interest for the present analysis. Women returned an average of 13 weeks post-delivery and completed the follow-up questionnaire. The average return follow-up was longer than the planned 10-week follow-up time because of differences in estimated due dates and actual due dates and based upon when mothers brought their infants to the hospital for immunizations. A research assistant conducted the baseline and follow-up questionnaires in a one-on-one interview using CAPI (Computer-Assisted Personal Interview software) (NOVA Research Company 2013). The study was approved by the Rhode Island Hospital Institutional Review Board (IRB), Makerere University School of Public Health IRB in Uganda, and the Uganda National Council for Science and Technology. All participants provided written informed consent.

The measures relevant to the current study included potential ABM factors associated with uptake of family planning services and use of contraceptives. Questions were translated into Luganda, back-translated, piloted, and modified for cultural equivalence.

The health system factor time to clinic was measured with an item assessing participants’ travel time to the clinic. Predisposing factors included the following demographic variables: age, education level, number of children, and religion. Postpartum depression was assessed by use of a modified 15-item version of the CESD scale (Radloff 1977) (α = 0.85 in the present sample). The cutoff for ‘possible depression’ was set at 11 and for ‘probable depression’ at 16, which is proportionate to the standard cutoffs used for the CESD-20 (Radloff 1977). Contraceptive knowledge of the effectiveness of different family planning methods (e.g., pills, injectables, rhythm method, etc.) was assessed with nine items adapted from the DHS measures (Measure DHS 2013b). We calculated the mean score of two items assessing attitudes toward family planning modified from information-motivation-behavioral skills (IMB) measures (Misovich et al. 1998) for sexual risk behavior (α = 0.87) with two items asking how the respondent would feel about using family planning and receiving couples counseling with their current partner; responses were formatted on a 5 point scale ranging from “very bad” to “very good.”

Among enabling factors, items were included to measure income, prior use of contraceptives, and location of delivery (at home vs. at a health care facility). Self-efficacy toward contraceptive use was measured by the mean of two items modified from IMB measures (α = 0.80, Misovich et al. 1998) assessing how easy or hard it would be to use family planning methods with their partner’s knowledge and receive couples counseling with their partner with response options ranging from “very hard” to “very easy” on a 5-point scale.

Sexual relationship power was assessed using Pulerwitz et al’s (2000) Sexual Relationship Power Scale, which included the Relationship Control and Decision-making Dominance sub-scales. The mean of eleven 5-point scale relationship control items was calculated (α = 0.82 in the present sample) and the mean of five 3-point scale decision-making questions was calculated separately (α = 0.67 in the present sample).

The mean of two items adapted from Rosengard et al. (2004) was used to measure perceived partner’s attitudes toward family planning. Participants were asked how their partner would feel about them using family planning methods and how their partner would feel about receiving couples counseling about family planning with them (response options ranging from (1) very bad to (5) very good). Communication with partner about contraceptives was measured with a four-point scale item asking how often the respondent discussed family planning with their current partner, with the response option ranging from “never” to “regularly.” Perceived male/female difference in fertility desires between partners assessed the number of additional children women believed their partner desired them to have compared to the number of additional children women themselves wanted to have with their partner.

History of emotional and physical abuse was measured through the Measures of Abuse scale from the Demographic Health Survey (DHS) measures (Measure DHS 2013a; Straus 1990). Four questions assessed whether women had ever experienced any emotional abuse (α = 0.62 in the present sample) and eight assessed any physical abuse (α = 0.68 in the present sample) from their current partner.

Adapted from Rosengard et al. (2004), perceived need of contraceptives was assessed by the following question: “In the future do you plan to use family planning?” with response options ranging from “not at all likely” to “extremely likely” on a 5-point scale.

The outcome variable, uptake of family planning services since delivery, was operationalized by the combination of two items asking participants if they sought family planning services and if they received couples counseling about family planning since delivery (response options: yes or no). Responding yes to either question was coded as having sought family planning services since delivery. Uptake of family planning services was included as an outcome variable in addition to contraceptive use because women in this sample may not have yet had a need for contraceptives due to natural contraceptive properties of having recently given birth until menses returns and of breastfeeding, and possible delayed return to sexual activity after childbirth.

The second outcome variable measured use of any effective contraceptive method since delivery. Respondents indicated methods used from a list of family planning methods. Methods considered effective included: condoms (currently using during at least 90 % of sex acts), pills, injectables, tubal ligation, vasectomy, intrauterine device, and implants. Methods considered ineffective were the rhythm method and withdrawal. A positive response to any effective method was coded as using effective contraceptives since delivery, while responding no to all items, or yes to only ineffective methods were coded as not using effective methods since delivery.

Data analysis approach

Univariate logistic regression models using SPSS version 20 (IBM Corp 2011) were used to test the independent predictors of the outcomes of uptake of family planning services and use of any effective contraceptives. Separate models were run for each of the two outcomes. Factors found to be significantly associated (p < 0.10) with either of the outcome variables in the univariate analysis were included in separate hierarchical multivariate regression analyses for each of our two outcomes. Variables were entered into the multivariate regression models in blocks mapped onto Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: (1) health system factors, (2) predisposing factors, (3) enabling factors, (4) relationship factors, and (5) need (Andersen 1995). Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) with 95 % confidence intervals (CI) are presented and used to interpret the effect size of each predictor variable on the outcome variables. The model chi-square and corresponding p value is presented for each block, and block chi-squares and p values are also presented. The ability of the model variables to accurately predict the outcome was assessed by calculating the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for each block of the multivariate analysis for each outcome and comparing the improvement in classification of the predictor variables on the dichotomous outcome variables between each block. ROC statistics and graphs are presented.

Results

258 women completed follow-up measures and were included in the analysis. Most women were from the Buganda tribe (75 %) or the Munyarwanda tribe (14 %), and identified as Muslim (41.9 %), Catholic (33.2 %), or other religion (24.9 %). The majority of the women reported time of travel to the clinic being within 1 h (<30 min = 31.8 %, 31–60 min = 36 %), whereas approximately 21 % of women reporting living 61–120 min from the clinic and 11 % reporting living further than 120 min from the clinic. Twenty five percent of women reported using any effective contraceptives since delivery. Similarly, 31 % of women reported seeking family planning services (e.g., counseling about family planning, obtaining contraceptives) since delivery (see Table 1 for a summary of this and additional descriptive statistics related to the ABM).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics and descriptive statistics N = 258, Uganda 2010

| % | Mean | SD | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time to clinic | ||||

| 0–30 min | 31.8 | |||

| 31–60 min | 36.0 | |||

| 61–120 min | 21.1 | |||

| >120 min | 11.1 | |||

| Number of children | 2.37 | 2.29 | 0 to 10 | |

| Age | 25.85 | 6.13 | 18 to 44 | |

| Education | ||||

| Primary or less | 57.5 | |||

| Secondary | 33.0 | |||

| >than secondary | 9.6 | |||

| Religion | ||||

| Catholic | 33.2 | |||

| Muslim | 41.9 | |||

| Other | 24.9 | |||

| Depression | 6.61 | 6.24 | 0 to 42 | |

| Contraceptive knowledge | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.00 to 1.00 | |

| Attitudes toward contraceptive use | 3.63 | 0.66 | 0 to 4 | |

| Self-efficacy toward contraceptive use | 3.10 | 1.03 | 0 to 4 | |

| Prior use of contraceptives | ||||

| Yes | 83.3 | |||

| No | 16.7 | |||

| Monthly income | ||||

| 0–15 USD | 78.9 | |||

| >15–50 USD | 16.5 | |||

| >50 USD | 4.6 | |||

| Location of delivery | ||||

| Home | 11.6 | |||

| Health care facility | 88.4 | |||

| Relationship control | 2.28 | 0.79 | 0 to 4 | |

| Dominance in decision making | 0.65 | 0.44 | 0 to 2 | |

| Partner attitudes toward family planning | 2.40 | 1.03 | 0 to 4 | |

| Any emotional abuse | ||||

| Yes | 63.5 | |||

| No | 36.5 | |||

| Any physical abuse | ||||

| Yes | 45.8 | |||

| No | 54.2 | |||

| Communication with partner about contraceptives | 1.81 | 1.22 | 0 to 3 | |

| Male/female difference in fertility desires | 1.10 | 1.72 | −2.00 to 9.00 | |

| Perceived need of family planning | 3.71 | 0.81 | 0 to 4 | |

| Uptake of family planning services since delivery | ||||

| Yes | 31.0 | |||

| No | 69.0 | |||

| Use of any effective contraceptives since delivery | ||||

| Yes | 25.2 | |||

| No | 74.8 |

Table 2 displays the findings from univariate logistic regression analyses testing the associations between independent variables and the outcome of uptake of family planning services since delivery. In univariate analyses, factors associated with increased family planning uptake at the p < 0.10 level included: secondary-level education (OR 2.31, 95 % CI 1.31–4.08), prior use of contraceptives (OR 11.67, 95 % CI 2.75–49.57), perceived partner attitudes toward family planning (OR 1.37, CI 1.04–1.81), communication with partner about contraceptives (OR 1.79, 95 % CI 1.38–2.31), perceived need for family planning (OR 3.21, 95 % CI 1.29–7.96). Factors associated with increased contraceptive use in univariate analysis at the p < 0.10 level include: secondary-level education (OR 1.71, 95 % CI 0.94–3.11), prior use of contraceptives (OR 17.80, 95 % CI 2.40–132.14), communication with partner about contraceptives (OR 1.86, 95 % CI 1.39–2.48), and perceived need for family planning (OR 2.59, 95 % CI 1.10–6.09).

Table 2.

Results of univariate logistic regression analysis for predictors of uptake of family planning services and use of any effective contraceptives, Uganda 2010

| Uptake of family planning services since delivery n = 258 |

Use of effective contraceptives since delivery n = 258 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR (95 % CI) | χ 2 | p | OR (95 % CI) | χ 2 | p | |

| Health system factors | ||||||

| Time to clinic | ||||||

| >120 min | 1.32 (0.55–3.18) | 0.37 | 0.54 | 1.67 (0.68–4.08) | 1.25 | 0.26 |

| 61–120 min | 0.81 (0.38–1.72) | 0.31 | 0.58 | 0.76 (0.34–1.70) | 0.44 | 0.51 |

| 31–60 min | 0.94 (0.50–1.79) | 0.03 | 0.86 | 0.76 (0.38–1.52) | 0.61 | 0.43 |

| 0–30 min (reference) | ||||||

| Predisposing factors | ||||||

| Number of children | 0.98 (0.87–1.10) | 0.17 | 0.68 | 1.02 (0.90–1.15) | 0.09 | 0.76 |

| Age | 0.99 (0.95–1.03) | 0.33 | 0.57 | 1.01 (0.96–1.05) | 0.05 | 0.83 |

| Education | ||||||

| >than secondary | 0.95 (0.35–2.55) | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.66 (0.21–2.07) | 0.50 | 0.48 |

| Secondary | 2.31 (1.31–4.08) | 8.38 | 0.004** | 1.71 (0.94–3.11) | 3.13 | 0.08† |

| Primary or less (reference) | ||||||

| Religion | ||||||

| Catholic | 1.13 (0.18–6.93) | 0.02 | 0.90 | 0.64 (0.31–1.31) | 1.48 | 0.22 |

| Muslim | 0.59 (0.81–4.27) | 0.28 | 0.59 | 0.64 (0.32–1.27) | 1.66 | 0.20 |

| Other (reference) | ||||||

| Postpartum depression | 0.97 (0.93–1.03) | 1.04 | 0.31 | 0.98 (0.93–1.03) | 0.57 | 0.45 |

| Contraceptive knowledge | 2.67 (0.73–9.75) | 2.21 | 0.14 | 2.30 (0.58–9.08) | 1.42 | 0.23 |

| Attitudes toward family planning | 1.29 (0.82–2.00) | 1.20 | 0.27 | 1.09 (0.70–1.70) | 0.15 | 0.69 |

| Enabling factors | ||||||

| Monthly income | ||||||

| >50 USD | 0.69 (0.18–2.64) | 0.29 | 0.59 | 0.92 (0.24–3.52) | 0.02 | 0.90 |

| >15–50 USD | 0.71 (0.34–1.50) | 0.79 | 0.38 | 0.63 (0.28–1.45) | 1.19 | 0.28 |

| 0–15 USD (reference) | ||||||

| Self-efficacy toward family planning | 1.17 (0.89–1.52) | 1.17 | 0.28 | 1.02 (0.77–1.34) | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Prior use of contraceptives | ||||||

| Yes | 11.67 (2.75–49.57) | 11.09 | 0.001** | 17.80 (2.40–132.14) | 7.93 | 0.005** |

| No (reference) | ||||||

| Location of delivery | ||||||

| Health care facility | 1.27 (0.54–2.99) | 0.30 | 0.59 | 1.40 (0.54–3.58) | 0.48 | 0.49 |

| Home (reference) | ||||||

| Relationship factors | ||||||

| Relationship control | 0.90 (0.64–1.27) | 0.38 | 0.54 | 1.00 (0.69–1.44) | 0.00 | 0.98 |

| Dominance in decision making | 0.97 (0.53–1.79) | 0.01 | 0.93 | 0.81 (0.42–1.56) | 0.41 | 0.52 |

| Perceived partner attitudes toward family planning | 1.37 (1.04–1.81) | 4.96 | 0.03* | 1.18 (0.89–1.57) | 1.29 | 0.26 |

| Any emotional abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 1.19 (0.68–2.09) | 0.37 | 0.54 | 0.97 (0.53–1.75) | 0.01 | 0.92 |

| No (reference) | ||||||

| Any physical abuse | ||||||

| Yes | 1.06 (0.62–1.81) | 0.04 | 0.84 | 1.15 (0.64–2.04) | 0.23 | 0.64 |

| No (reference) | ||||||

| Communication with partner about contraceptives | 1.79 (1.38–2.31) | 19.51 | <0.001** | 1.86 (1.39–2.48) | 17.83 | <0.001** |

| Male/female difference in fertility desires | 0.87 (0.73–1.04) | 2.48 | 0.12 | 0.92 (0.77–1.09) | 0.96 | 0.33 |

| Need | ||||||

| Perceived need of family planning | 3.21 (1.29–7.96) | 6.33 | 0.01* | 2.59 (1.10–6.09) | 4.75 | 0.03* |

OR odds ratio

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01

Table 3 displays results of the multivariate model testing predictors of both outcomes. Note, we removed perceived partner attitudes from the multivariate analysis for both models due to multicollinearity between perceived partner attitudes and partner communication.

Table 3.

Results of multivariate hierarchical logistic regression model for predictors of uptake of family planning services and use of any effective contraceptives, Uganda 2010

| Model | Uptake of family planning services since delivery n = 258 |

Use of effective contraceptives since delivery n = 258 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR (95 % CI) | χ 2 | df | p | AOR (95 % CI) | χ 2 | df | p | |

| Block 1 predisposing factors | 9.08 | 2 | 0.01* | 4.47 | 2 | 0.11 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| >than secondary | 0.95 (0.35–2.55) | 0.11 | 0.92 | 0.66 (0.21–2.07) | 0.50 | 0.48 | ||

| Secondary | 2.31 (1.31–4.08) | 8.38 | 0.004** | 1.71 (0.94–3.11) | 3.13 | 0.08† | ||

| Primary or less (reference) | ||||||||

| Block 2 enabling factors | 21.24 | 1 | <0.001*** | 19.98 | 1 | <0.001*** | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| >than secondary | 0.80 (0.29–2.20) | 0.18 | 0.67 | 0.56 (0.18–1.76) | 0.99 | 0.32 | ||

| Secondary | 2.26 (1.25–4.07) | 7.30 | 0.007** | 1.63 (0.88–3.01) | 2.40 | 0.12 | ||

| Primary or less (reference) | ||||||||

| Prior use of contraceptives | 11.82 (2.76–50.59) | 11.08 | <0.001** | 18.11 (2.43–134.83) | 8.00 | 0.005** | ||

| Block 3 relationship factors | 19.62 | 1 | <0.01** | 17.86 | 1 | <0.001*** | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| >than secondary | 0.67 (0.24–1.87) | 0.59 | 0.44 | 0.46 (0.14–1.49) | 1.68 | 0.20 | ||

| Secondary | 2.81 (1.49–5.30) | 10.16 | 0.001** | 1.95 (1.02–3.74) | 4.04 | 0.04* | ||

| Primary or less (reference) | ||||||||

| Prior use of contraceptives | 9.13 (2.06–40.42) | 8.50 | 0.004** | 13.25 (1.74–100.72) | 6.23 | 0.01* | ||

| Communication with partner about contraceptive use |

1.79 (1.34–2.37) | 17.06 | 0.00** | 1.82 (1.34–2.45) | 15.10 | 0.00** | ||

| Block 4 need | 59.44 | 1 | <0.001*** | 5.29 | 1 | 0.02* | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| >than secondary | 0.68 (0.24–1.92) | 0.54 | 0.46 | 0.47 (0.15–1.52) | 1.59 | 0.21 | ||

| Secondary | 3.03 (1.58–5.82) | 11.09 | 0.001** | 2.04 (1.05–3.95) | 4.45 | 0.04* | ||

| Primary or less (reference) | ||||||||

| Prior use of contraceptives | 7.15 (1.58–32.37) | 6.53 | 0.01* | 11.03 (1.42–83.05) | 5.22 | 0.02* | ||

| Communication with partner about contraceptive use |

1.79 (1.36–2.37) | 16.95 | <0.001*** | 1.81 (1.34–2.44) | 14.89 | <0.001*** | ||

| Perceived need of family planning | 2.57 (1.09–6.08) | 4.63 | 0.03* | 2.06 (0.91–4.65) | 3.02 | 0.08† | ||

χ2, df and p are reported for the each block

AOR adjusted odds ratio, adjusted for variables included in the model

p < 0.10;

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001

The overall model was statistically significantly associated with uptake of family planning services (χ2 = 59.44, p < 0.01), and each variable was found to be a statistically significant predictor of the outcome. Specifically, looking at the final model which included all variables, secondary education was statistically significant (AOR = 3.03, 95 % CI 1.57–5.83). The effect of the enabling factor, prior use of contraceptives, decreased with all other model variables accounted for, but a statistically significant association remained (AOR = 7.15, 95 % CI 1.58–32.37). Communication with partner about contraceptives remained a statistically significant positive predictor of uptake of family planning use (AOR = 1.80, 95 % CI 1.36–2.37). Finally, with all other variables accounted for, a statistically significant positive relationship was found between the need variable and uptake of family planning services (AOR = 2.57, 95 % CI 1.09–6.08).

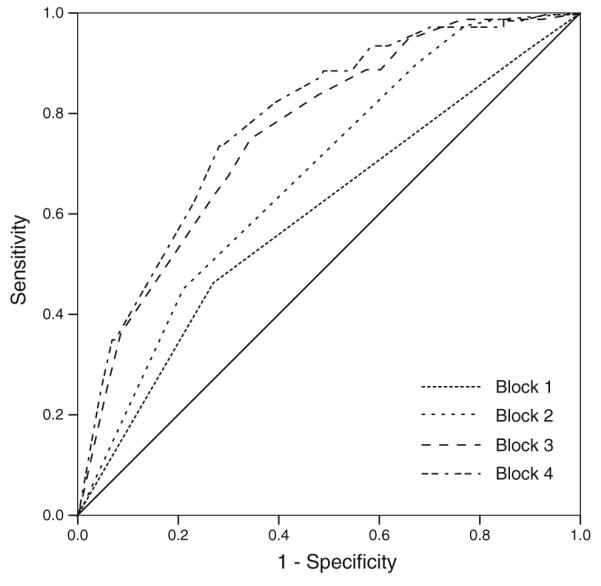

The ROC curves for each block are presented in Fig. 2. The area under the curve was statistically significant and increased with each addition to the model, indicating an improvement in fit of the model to the data with each added block. The area under the curve (0.79, 95 % CI 0.73–0.84, p < 0.001) with all predictors added in the final model indicates that the full model is performing well, with no large discrepancy between observed and expected rates of family planning service uptake.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for block 1–4 predicting family planning service uptake, Uganda 2010. Block 1 (enabling factors): area under curve = 0.60. 95 % CI (0.52–0.67), p = 0.01. Block 2 (predisposing factors): area under curve = 0.68, 95 % CI (0.61–0.75), p < 0.001. Block 3 (relationship factors): area under curve = 0.76, 95 % CI (0.70–0.82), p < 0.001. Block 4 (need): area under curve = 0.79, 95 % CI (0.73–0.84), p < 0.001. The dotted lines are the ROC curve for each block. The solid diagonal line is the line of no discrimination

For the outcome of contraceptive use, the overall model was a statistically significant predictor of contraceptive use (χ2 = 47.59, p < 0.01). In the final model, the effect of secondary education on contraceptive remained statistically significant (AOR = 2.04, 95 % CI 1.05–3.95). The effect of prior use of contraceptives decreased with all variables in the model, but remained strongly related to contraceptive use (AOR = 10.79, 95 % CI 1.40–83.06). The positive association between communication with partner and contraceptive use remained statistically significant with perceived need and other previously entered variables included (AOR = 1.81, 95 % CI 1.34–2.44). Finally, with all other variables controlled for, perceived need of family planning was trending toward a positive relationship with use of effective contraceptives since delivery (AOR = 2.06, 95 % CI 0.91–4.65).

The receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve for the model with the addition of each block are presented in Fig. 3. The area under the curve increased with each addition to the model, indicating an improvement in fit of the model to the data with each added block. The area under the curve with all predictors added in the final model was 76 % (95 % CI 0.70–0.83, p < 0.001), indicating that the full model is a good fit to the data with predictive accuracy in the outcome variable contraceptive use.

Fig. 3.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves for block 1–4 predicting contraceptive use, Uganda 2010. Block 1 (enabling factors): area under curve = 0.58. 95 % CI (0.50–0.66), p = 0.06. Block 2 (predisposing factors): area under curve = 0.66, 95 % CI (0.59–0.73), p < 0.001. Block 3 (relationship factors): area under curve = 0.74, 95 % CI (0.68–0.81), p < 0.001. Block 4 (need): area under curve = 0.76, 95 % CI (0.70–0.82), p < 0.001. The dotted lines are the ROC curve for each block. The solid diagonal line is the line of no discrimination

Discussion

The present study contributes to our understanding of Uganda’s high unmet need for family planning and lends support for the need to strengthen the delivery of postpartum family planning (PPFP) in this population. Despite a high perceived need for contraception and generally positive attitudes toward family planning among postpartum Ugandan women, the proportion of women who had sought family planning services (31 %) and used effective contraceptives (25 %) approximately 3 months postpartum was low. The unmet need for family planning in this sample was considerably higher than the 2011 DHS estimates of the unmet need for family planning among married rural women in Uganda (37 %) (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012): 66 % (n = 171) of the sample had an unmet need for family planning.

By identifying determinants of family planning service uptake and contraceptive use among postpartum women in rural Uganda, our findings also have practical implications for strengthening PPFP. Using an adapted version of Andersen’s Behavioral Health Service Use model to guide analysis (Andersen 1995; Andersen and Newman 1973), we identified statistically significant predictors of family planning service uptake and contraceptive use at multiple levels of the model, including predisposing, enabling, relationship, and need factors. Consistent with data across 24 sub-Saharan African countries (UNFPA 2010), the present study reinforces the importance of women’s education on family planning, which was a statistically significant predictor in multivariate analysis for both outcomes. This finding identifies women with lower education as more at risk of having an unmet need for family planning, highlighting the need for family planning counselors to pay more attention to and address the issues of the less educated women in order to improve their uptake of family planning services.

Most relevant to public health practice, the study also identified modifiable factors related to family planning service uptake and contraceptive use. The ROC curve (see Figs. 2, 3) demonstrated the greatest improvement in explaining both uptake in family planning services and contraceptive use with the addition of the relationship factor block to the model, lending support to a growing body of evidence demonstrating an association between partner communication and contraceptive use (e.g., Ankomah and Anyanti 2011; Oladeji 2008). Future interventions in Uganda should explore innovative approaches to increase male involvement in family planning discussions and improve communication between partners, while taking into account social taboos that may exist surrounding men’s active participation in women’s reproductive health (Mosha et al. 2013).

Finally, the present study calls attention to the importance of perceived need for family planning, which as hypothesized, was positively associated with family planning service uptake and contraceptive use. Qualitative research should examine factors associated with perceived need among postpartum women in Uganda in more depth, as women’s understanding of the natural contraceptive effects of postpartum amenorrhea interval and breastfeeding may influence their uptake of family planning during this time (Duong et al. 2005; Salway and Nurani 1998). Our study’s finding of the positive association between perceived partner attitudes toward family planning and family planning service uptake also suggest that women’s perceived need for family planning is likely in part a reflection of their perceived partner’s attitudes toward family planning, as found in prior research (Cleland et al. 2006). This further demonstrates the importance of garnering male support for family planning in the context of Uganda, which may be accomplished by increasing couples’ communication on reproductive health (Hartmann et al. 2012).

The present study has several limitations. Data were cross-sectional and originated from self-reported measures. Moreover, there was a lack of contextual factors related to the health system and environment that were available in the original study for us to include in the present study. While the hospital in which the present study took place provides a variety of contraceptive methods free of charge, the quality of counseling, drug stock out, wait time at the clinic and other structural barriers are likely factors influencing health service uptake as found in prior research in similar settings (Kiwanuka et al. 2008), and should be examined in future studies. Due to nonsystematic recruitment of women, as well as the recruitment of women attending ANC, generalizability may be limited. However, 95 % of pregnant Ugandan women attend ANC (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012), minimizing this limitation. Finally, women in the study were likely in the postpartum amenorrhea interval between childbirth and the return of menstruation and may have been breastfeeding, which offers relatively effective natural protection from contraception. It is possible that some of the null findings could be due to the fact that contraception use at this time is likely to be lower than during other times (Ross and Winfrey 2001). However, women were likely susceptible to pregnancy at the time of the study: 75.5 % of the sample had begun having vaginal sex again and postpartum amenorrhea is shorter in the region of the study (6 months) than national averages (UBOS and IFC International Inc. 2012).

In sum, fulfilling the unmet need for family planning in Uganda and other developing countries has significant health outcomes for women and infants and helps improve an array of social and economic outcomes on a population level (Guttmacher Institute 2009, 2010). The present study demonstrated an especially high unmet need (66 %) among ANC attendees at a rural Ugandan hospital approximately 3 months postpartum, indicating high risk for poorly spaced pregnancy. Predisposing, enabling, relationship, and perceived need factors were identified as key determinants of postpartum women’s uptake of family planning services and contraceptive use. Particularly, education, prior use of contraceptives, communication with partner about contraceptives, and perceived need were identified as determinants, and should be considered in antenatal and postnatal family planning counseling in Uganda.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Harriet Nantaba, Hajara Kagulire, and Farouk Kimbowa for their assistance with data collection, the midwives at Gombe Hospital, and Stephen Schensul and Howard Tennen for comments on an earlier version of this paper. The study was funded by an Innovations in Women’s Health Research Seed Grant from Brown University/Women & Infants Hospital National Center of Excellence in Women’s Health (PI: Kiene). This paper is a product of KMS’s MPH thesis at the University of Connecticut Health Center.

Contributor Information

Katelyn M. Sileo, Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA

Rhoda K. Wanyenze, Makerere University School of Public Health, Kampala, Uganda

Haruna Lule, Gombe Hospital, Gombe, Uganda.

Susan M. Kiene, Department of Community Medicine and Health Care, University of Connecticut School of Medicine, Farmington, CT, USA; Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Providence, RI, USA; Division of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Graduate School of Public Health, San Diego State University, 5500 Campanile Drive (MC-4162), San Diego, CA 92182, USA

References

- Agyei WKA, Migadde M. Demographic and sociocultural factors influencing contraceptive use in Uganda. J Biosoc Sci. 1995;27:47–60. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000006994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R. A behavioral model for families’ use of health services. Center for Health Administration Studies Research Series, University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1968. (Research Series No. 25). [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen RM, Newman JF. Social and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United States. Milbank Meml Q. 1973;51:95–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ankomah A, Anyanti J, Oladosu M. Myths, misinformation, and communication about family planning and contraceptive use in Nigeria. Open Access J Contracep. 2011;2:95–105. (2011) doi:10.2147/OAJC.S20921. [Google Scholar]

- Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998 to 2011. Psychosoc Med. 2012 doi: 10.3205/psm000089. doi:10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland J, Bernstein S, Ezeh A, Faundes A, Glasier A, Innis J. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 2006;368:1810–1827. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69480-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duong DV, Lee AH, Binns CW. Contraception within six-month postpartum in rural Vietnam: implications of family planning and maternity services. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2005;10(2):111–118. doi: 10.1080/13625180500131527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eliason S, Baiden F, Quansah-Asare G, Graham-Hayfron Y, Bonsu D, Phillips J, Awusabo-Asare K. Factors influencing the intention of women in rural Ghana to adopt postpartum family planning. Reprod Health. 2013;10(1):34. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-34. doi:10.1186/1742-4755-10-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensor T, Cooper S. Overcoming barriers to health service access: influencing the demand side. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19(2):69–79. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gribble JN, Murray N, Menotti EP. Reconsidering childhood undernutrition: can birth spacing make a difference? An analysis of the 2002–2003 El Salvador National Family Health Survey. Matern Child Nutr. 2008;5(1):49–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00158.x. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8709.2008.00158.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute . Benefits of meeting the contraceptive needs of Ugandan women. Guttmacher Institute and Economic Policy Research Centre; New York: 2009. (2009 series, No. 4). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmacher Institute . Sub-Saharan Africa: facts on investing in family planning and maternal and newborn health. Guttmacher Institute; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann M, Gilles K, Shattuck D, Kerner B, Guest G. Changes in couples’ communication as a result of a male-involvement family planning intervention. J Health Commun. 2012;17:802–819. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.650825. doi:10.1080/10810730.2011.650825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hung KJ, Scott J, Ricciotti HA, Johnson TR, Tsai AC. Community-level and individual-level influences of intimate partner violence on birth spacing in sub-Saharan Africa. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;119(5):975–982. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824fc9a0. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e31824fc9a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketende C, Gupta N, Bessinger R. Facility-level reproductive health interventions and contraceptive use in Uganda. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2003;29(3):130–137. doi: 10.1363/ifpp.29.130.03. doi:10.2307/3181079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan S, Bradley SEK, Fishel J, Mishra V. Unmet need and the demand for family planning in Uganda: further analysis of the Uganda Demographic and Health Surveys, 1995–2006. Macro International Inc.; Calverton, MD: [Accessed 13 May 2014]. 2008. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/FA60/FA60.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kiene SM, Sileo K, Wanyenze RK, Lule H, Bateganya MH, Jasperse J, Nantaba H, Jayaratne K. Barriers to and acceptability of provider-initiated HIV testing and counseling and adopting HIV prevention behaviors in rural Uganda: a qualitative study. J Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1359105313500685. doi:10.1177/1359105313500685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiwanuka SN, Ekirapa EK, Peterson S, Okui O, Rahman MH, Peters D, Pariyo GW. Access to and utilisation of health services for the poor in Uganda: a systematic review of available evidence. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008;102(11):1067–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.023. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Measure DHS. [Accessed 14 May 2014];DHS domestic violence module. 2013a http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/DHSQM/DHS6_Module_Domestic_Violence_28March2013_DHSQM.pdf.

- Measure DHS. [Accessed 14 May 2014];DHS model questionnaires. 2013b http://www.measuredhs.com/What-We-Do/Survey-Types/DHS-Questionnaires.cfm.

- Misovich SJ, Fisher WA, Fisher JD. A measure of AIDS prevention information, motivation, behavioral skills, and behavior. In: Davis CM, Yarber WH, Bauserman R, Schreer G, Davis SL, editors. Handbook of sexuality related measures. Sage Publishing; Thousand Oaks: 1998. pp. 328–337. [Google Scholar]

- Mosha I, Ruben R, Kakoko D. Family planning decisions, perceptions and gender dynamics among couples in Mwanza, Tanzania: a qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:523. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-523. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalwadda G, Mirembe F, Byamugisha J, Faxelid E. Persistent high fertility in Uganda: young people recount obstacles and enabling factors to use of contraceptives. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:530. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-530. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-10-530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NOVA Research Company . Questionnaire Development System (QDS) version 3.0. Silver Spring; MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Okech TC, Wawire NW, Mburu TK. Contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Kenya’s city slums. Int J Bus Soc Sci. 2011;2(1):22–43. [Google Scholar]

- Oladeji D. Communication and decision-making factors influencing couples interest in family planning and reproductive health behaviours in Nigeria. Stud Tribes Tribals. 2008;6(2):99–103. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S. Pregnancy: a “teachable moment” for weight control and obesity prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;202(2):135.e1–135.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Gortmaker SL, DeJong W. Measuring sexual relationship power in HIV/AIDS research. Sex Roles. 2000;42(7–8):637–660. doi:10.1023/A:100705150697220. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1(3):385–401. doi:10.1177/014662167700100306. [Google Scholar]

- Rijsdijk L, Bos A, Lie R, Ruiter R, Leerlooijer J, Kok G. Correlates of delayed sexual intercourse and condom use among adolescents in Uganda: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2012;12(1):817. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-817. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosengard C, Phipps MG, Adler NE, Ellen JM. Adolescent pregnancy intentions and pregnancy outcomes: a longitudinal examination. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JA, Winfrey WL. Contraceptive use, intention to use, and unmet need during the extended postpartum period. Int Fam Plan Perspect. 2001;27(1):20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein SO. Further evidence of the effects of preceding birth intervals on neonatal, infant, and under-five-years mortality and nutritional status in developing countries: Evidence from the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS Working Papers No. 41) Macro International Inc.; Calverton, MD: [Accessed 1 June 2014]. 2008. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/WP41/WP41.pdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutstein SO. Trends in birth spacing. DHS Comparative Reports No. 28. ICF Macro; Calverton, MD: [Accessed 1 June 2014]. 2011. http://www.measuredhs.com/pubs/pdf/CR28/CR28.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Salway S, Nurani S. Postpartum contraceptive use in Bangladesh: understanding users’ perspectives. Stud Fam Plan. 1998;29(1):41–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson R, Baschieri A, Clements S, Hennink M, Madise N. Contextual influences on modern contraceptive use in sub-Saharan Africa. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:1233–1240. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.071522. doi:10. 2105/AJPH.2005.071522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: the Conflict (CT) Scales. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families. Transaction Publishers; New Brunswick: 1990. pp. 29–47. [Google Scholar]

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) IFC International Inc. Uganda Demographic Health Survey 2011. IFC International; Calverton, MD: [Accessed 10 May 2014]. 2012. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR264/FR264.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) How universal is access to reproductive health? A review of the evidence. UNFPA; New York: [Accessed 14 May 2014]. 2010. http://www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2010/universal_rh.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Warren C, Mwangi A, Oweya E, Kamunya R, Koskei N. Safeguarding maternal and newborn health: improving the quality of postnatal care in Kenya. Int J Qual Health Care. 2010;22:24–30. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzp050. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzp050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]