Abstract

How do cats manage to walk so graciously on top of narrow fences or windowsills high above the ground while apparently exerting little effort? In this study we investigated cat full-body mechanics and the activity of limb muscles and motor cortex during walking along a narrow 5-cm path on the ground. We tested the hypotheses that during narrow walking 1) lateral stability would be lower because of the decreased base-of-support area and 2) the motor cortex activity would increase stride-related modulation because of imposed demands on lateral stability and paw placement accuracy. We measured medio-lateral and rostro-caudal dynamic stability derived from the extrapolated center of mass position with respect to the boundaries of the support area. We found that cats were statically stable in the frontal plane during both unconstrained and narrow-path walking. During narrow-path walking, cats walked slightly slower with more adducted limbs, produced smaller lateral forces by hindlimbs, and had elevated muscle activities. Of 174 neurons recorded in cortical layer V, 87% of forelimb-related neurons (from 114) and 90% of hindlimb-related neurons (from 60) had activities during narrow-path walking distinct from unconstrained walking: more often they had a higher mean discharge rate, lower depth of stride-related modulation, and/or longer period of activation during the stride. These activity changes appeared to contribute to control of accurate paw placement in the medio-lateral direction, the width of the stride, rather than to lateral stability control, as the stability demands on narrow-path and unconstrained walking were similar.

Keywords: accuracy, motor cortex, locomotion

real-world locomotion involves navigation through various terrains, obstacles, and paths of different widths—a complex behavioral task with many, often conflicting requirements. For example, walking on a narrow path requires both accurate foot placement and lateral balance control. Cats, in contrast to humans (Schrager et al. 2008), seem to have the natural ability to meet these task demands, as they are often seen walking on narrow fences or windowsills high above the ground without falling. How does the cat perform locomotion when both accurate paw placement and control of balance are required? Previous research has demonstrated that the motor cortex is closely involved in both of these motor behaviors.

It has been shown that during normal unobstructed locomotion the activity of almost all neurons in layer V of the motor cortex, including neurons that project to the pyramidal tract (PTNs), is modulated in the rhythm of strides: it is higher during one phase of the stride and lower during another phase (e.g., Armstrong and Drew 1984a; Beloozerova and Sirota 1985, 1993a, 1993b; Drew 1993; Fitzsimmons et al. 2009; Stout and Beloozerova 2012, 2013; Widajewicz et al. 1994). For most neurons, this modulation becomes even more pronounced when the animal has to step over objects or to step on specific locations (Beloozerova and Sirota 1993a; Drew 1993; Stout and Beloozerova 2012, 2013; Widajewicz et al. 1994). Moreover, in about one-third of neurons, the depth of modulation changes proportionally to the demand on accuracy of stepping, i.e., the reduction in the maximal allowable deviation of paw placement location from the center of the target and the associated progressively smaller dispersion of foot placements on the surface (see, e.g., Fig. 3 in Beloozerova et al. 2010). When the motor cortex is inactivated or lesioned, accurate stepping is impossible, whereas normal walking is not affected (Beloozerova and Sirota 1993a; Chambers and Liu 1957; Friel et al. 2007; Liddell and Phillips 1944; Metz and Whishaw 2002; Trendelenburg 1911). This group of data has led to the conclusion that during locomotion over a complex terrain the control of stepping accuracy is a special function of the motor cortex (Beloozerova and Sirota 1988, 1993a, 1993b). Subsequently, parameters of signals that the motor cortex produces to ensure accurate paw positioning during locomotion were investigated across a number of neuronal subpopulations of the motor cortex (Beloozerova et al. 2003; Sirota et al. 2005; Stout and Beloozerova 2012, 2013). It has been found that, although different neuronal groups responded differently to accuracy demands on stepping, the leading theme in their responses was a change, typically an increase, in the depth of the stride-related activity modulation. That is, to ensure more spatially accurate stepping, the activity of motor cortex neurons becomes more precise in timing with respect to the stride phase. All accurate-stepping tasks that have been investigated so far, however, imposed demands on stepping accuracy chiefly in the longitudinal direction. These demands were created either by hurdles placed across the walkway, which the animal had to overstep, or by similarly placed planks, on top of which the animal had to walk. Thus a question has remained as to whether motor cortex signals for accurate stepping generalize to the medio-lateral direction.

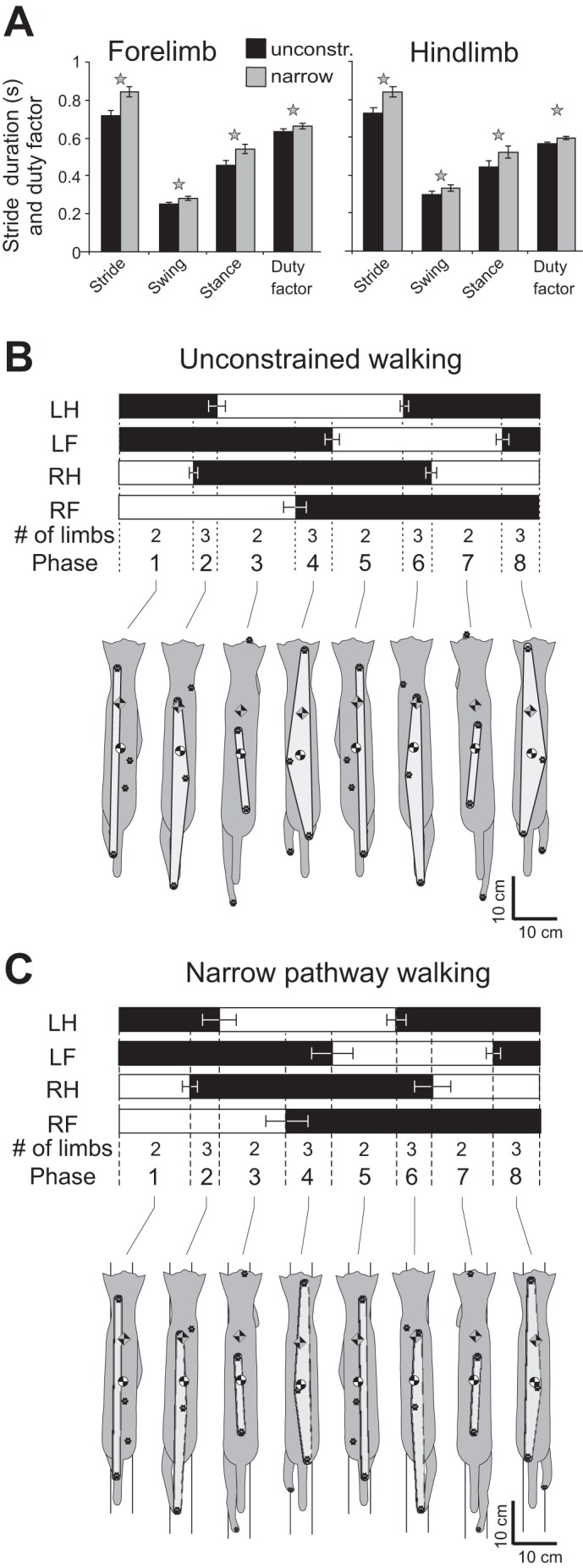

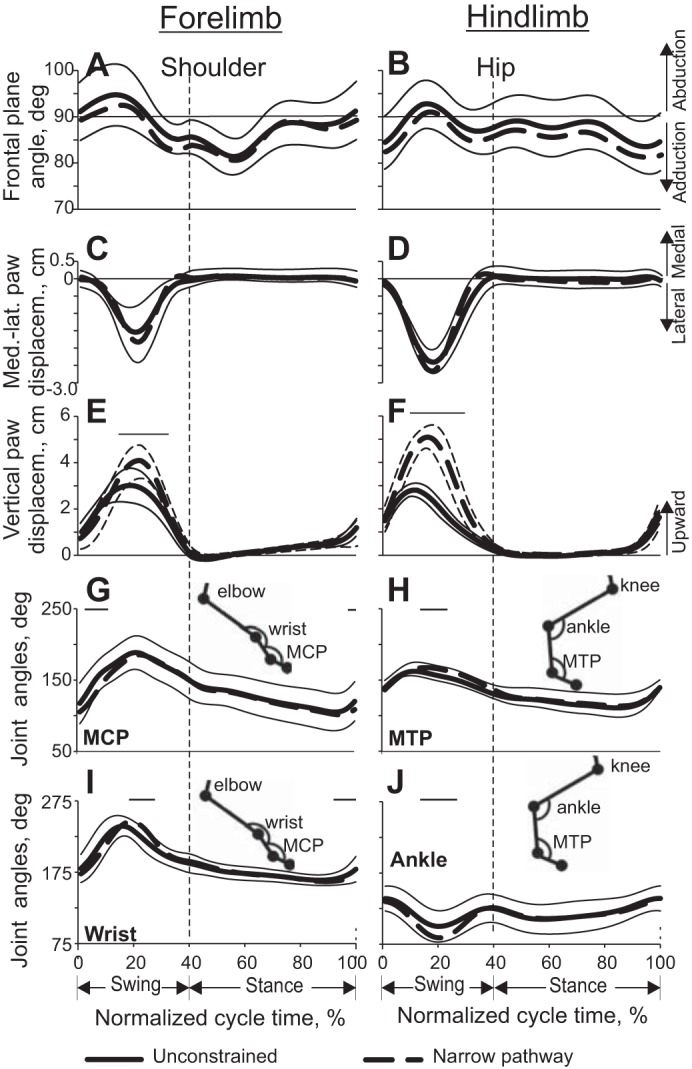

Fig. 3.

General kinematic characteristics of unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A: mean cycle, swing, and stance phase duration and cycle duty factor for the fore- and hindlimb during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. Vertical bars show SDs; stars indicate significant differences between the walking conditions (P < 0.05). B: stance and swing stride phases for each limb and representative base of support, center of mass, and extrapolated center of mass position for each limb support phase during unconstrained locomotion. Top: stance phase is shown in black. LH, left hindlimb; LF, left forelimb; RH, right hindlimb; RF, right forelimb. Thin horizontal bars indicate SD for the phase onset and offset normalized time. Limb support phases follow the 2-3-2-3-2-3-2-3 pattern; each phase is indicated by numbers 1–8. Bottom: base of support area (in light gray), paw prints, CoM, and XCoM are overlaid on the cat postures. C: stance and swing stride phases for each limb and representative base of support, CoM, and XCoM position for each limb support phase during narrow-path locomotion. Mean data of 5 cats.

It has been also shown that modulation of motor cortex activity during locomotion is related to maintenance of lateral stability of the body when it is perturbed by alteration in the body configuration (Beloozerova et al. 2005), by tilt of support surface in the frontal plane (Karayannidou et al. 2009), or by increased lateral displacement of the body during walking with wide stance (Farrell et al. 2014). Given that imposing requirements on either accuracy of stepping or lateral stability results in a change in activity of the motor cortex in the cat, we expected that walking along a narrow path only slightly wider than the paw will lead to greater involvement of motor cortex in this task. Indeed, during normal unobstructed locomotion the distance between left and right paws while on the ground, the stance width, may be >6 cm, whereas the shortest distance between paws in the rostro-caudal direction is at least 20 cm (Farrell et al. 2014; Macpherson et al. 2007; Misiaszek 2006). Therefore the body center of mass is much closer to the boundaries of support in the frontal than in the sagittal plane, and thus the cat's body is likely to be less stable in lateral than rostro-caudal directions even in normal conditions. Walking on a narrow path appears to make lateral stability even more challenging. In addition, walking along a narrow path imposes accuracy demands on paw placement in the medio-lateral direction. Although walking along narrow pathways is a part of the cat's everyday behavioral repertoire, little is known about the role of the motor cortex in the control of this behavior and the motor strategies employed.

The goal of this study was to compare full-body mechanics, electromyographic (EMG) activity, and activity of neurons from the forelimb and hindlimb representations of the primary motor cortex between normal unobstructed walking and walking on a narrow (5 cm wide) path in the cat. We tested the hypotheses that during narrow-path walking 1) the margins of static and dynamic stability would be smaller and 2) the activity of the motor cortex would be more modulated in the rhythm of strides because of imposed additional requirements on lateral stability and accuracy of paw placement.

Preliminary results have been published in abstract form (Farrell et al. 2008, 2011).

METHODS

Ethical Approval

All animal procedures were in agreement with the US Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of Barrow Neurological Institute and Georgia Institute of Technology.

Animal Characteristics and Locomotion Tasks

Ten cats (Table 1) were used in this study. Full-body mechanics and hindlimb EMG activity were investigated in a group of five cats, and motor cortex activity and EMG of fore- and hindlimbs were studied in a separate group of five cats. All cats were trained 1–2 h a day for at least 4 wk to walk on a Plexiglas-enclosed walkway (2.5–3.0 m long and 0.3 m wide) with unconstrained stance width (unconstrained walking) and along a 5-cm-wide path created within this walkway by placing two small triangular prisms with 2-cm sides on either side of the walkway (narrow-path walking) (Fig. 1A). One cat (cat Zv) was also trained to perform the same tasks on a treadmill. All training was performed with positive reinforcement (food) according to Skinner's operant conditioning method (Pryor 1975; Skinner 1938). Cats that participated in cortical recording experiments were trained to wear a cotton jacket, a light backpack containing connectors, EMG preamplifiers, and an electro-mechanical sensor on the right forepaw for recording paw ground contact and liftoff (Beloozerova et al. 2010; Beloozerova and Sirota 1993a). Some data on the activity of the motor cortex in these cats have been included in previous publications (Beloozerova et al. 2010; Farrell et al. 2014; Sirota et al. 2005; Stout and Beloozerova 2012, 2013).

Table 1.

Animal characteristics and analyses conducted

| Cat | Sex | Mass, kg | Forelimb Length, cm | Hindlimb Length, cm | Full-Body Mechanics (Unc/Nar), no. of cycles | EMG (Unc/Nar), no. of cycles | Motor Cortex, no. of cells |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Az | Female | 4.2 | 21.1 | 24.4 | 17/21 | 24/20 | |

| Ba | Female | 3.0 | 19.1 | 25.6 | 8/29 | 12 | |

| In | Female | 3.2 | 19.1 | 25.8 | 29/20 | 23/22 | |

| Ko | Male | 3.8 | 21.3 | 28.4 | 28 | ||

| Kr | Female | 3.0 | 19.4 | 25.1 | 36/19 | 15/43 | |

| Mz | Female | 2.8 | 21.4 | 27.6 | 20/19 | 19/11 | |

| Mc | Female | 3.7 | 23.0 | 26.7 | 157/244 | 15 | |

| Sv | Female | 3.8 | 19.5 | 26.0 | 23/20 | 5/8 | |

| Va | Male | 4.2 | 64 | ||||

| Zv | Female | 4.0 | 20.5 | 25.0 | 61/90 | 55 |

Hindlimb length is defined as the sum of metatarsal, shank, and thigh lengths; forelimb length is defined as the sum of metacarpal, forearm, and arm lengths. Unc and Nar, unconstrained and narrow-path walking conditions. Cats studied for full-body mechanics had the following muscles implanted: soleus, medial and/or lateral gastrocnemius (LG), tibialis anterior, vastus medialis or vastus lateralis (VL), rectus femoris, sartorius medial, iliopsoas, biceps femoris anterior, biceps femoris posterior, and adductor femoris (AF). Cats studied for motor cortex activity had implanted LG, VL, AF, gluteus medius, triceps brachii lateral head, extensor digitorum communis, and flexor carpi ulnaris.

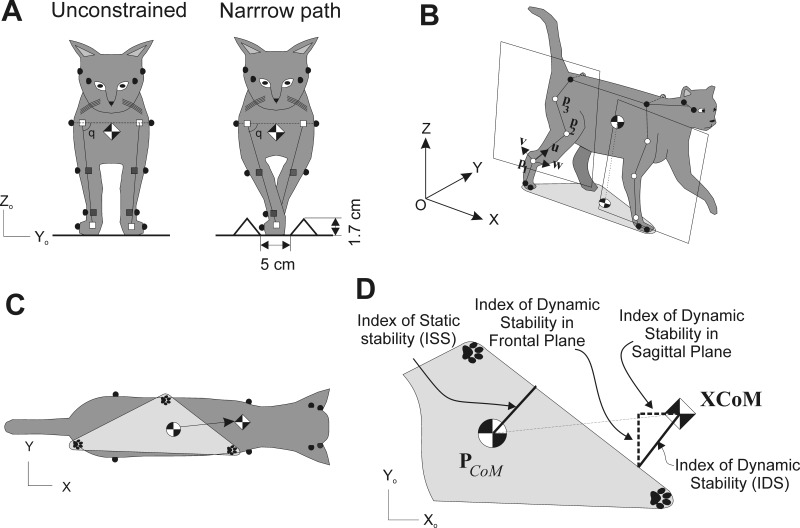

Fig. 1.

Determining static and dynamic stability of locomotion. A: frontal view of the cat demonstrating unconstrained and narrow path walking conditions. Gray and open squares indicate estimated centers of the joints or paws. Angle q is the hip and shoulder angle in the frontal plane. B: perspective view of the cat during walking and definition of the hindlimb plane (the forelimb plane was defined in the same way). Three open markers on each limb were used to define unit vectors v, u, and w and the limb plane (see text for further explanations). C: dorsal view of the cat during walking: black-and-white circle, center of mass (CoM); black-and-white diamond, extrapolated center of mass (XCoM) position. Paw prints indicate paws on the ground that form the base of support, a lighter gray area. Filled circles are markers on iliac crests, scapulars, at the corner of each eye and ear. D: definitions of the base of support, index of static stability (ISS), index of dynamic stability (IDS), and its components, i.e., index of dynamic stability in the frontal plane (IDSf) and index of dynamic stability in the sagittal plane (IDSs) (see text for further explanations).

Surgical Procedures

After animals were trained, eight cats were implanted with EMG electrodes in selected limb muscles and five cats additionally were implanted with guide tubes for access to the motor cortex and pyramidal tract (Table 1; for details see Beloozerova et al. 2010; Prilutsky et al. 2005). The surgery was performed in aseptic conditions and under general anesthesia (ketamine 10 mg/kg sc; atropine 0.05 mg/kg sc; isoflurane inhalation, induction at 5%, maintained at 1–3%). The animal was continuously monitored for temperature, respiration, heart rate, and blood pressure throughout the surgery. Teflon-insulated multistranded stainless steel wires (CW5402, Cooner Wire) were passed subcutaneously along the back from connectors mounted on the skull with stainless steel screws and dental cement to muscles of interest, and pairs of wires with a small strip of insulation removed were secured in the midbelly of each muscle 5–10 mm apart. EMG electrodes were implanted in the following muscles of five cats used for full-body biomechanical analysis: soleus (SO; ankle extensor), medial (MG) and lateral (LG) gastrocnemii (ankle extensors and knee flexors), tibialis anterior (TA; ankle flexor), vastus medialis (VM) or lateralis (VL) (knee extensors), rectus femoris (RF; knee extensor and hip flexor), sartorius medial (SAM; knee and hip flexor), iliopsoas (IP; hip flexor), biceps femoris anterior (BFA; hip extensor), biceps femoris posterior (BFP; hip extensor and knee flexor), and adductor femoris (magnus) (AF; hip adductor and extensor). Three cats prepared for cortical recordings had the following muscles implanted: LG, VL, AF, gluteus medius (GLM; hip abductor and extensor), triceps brachii lateral head (TRL; elbow extensor), extensor digitorum communis (EDC; wrist and phalanges dorsiflexor), and flexor carpi ulnaris (FCU; wrist plantar flexor). Electrode location was confirmed with electrical stimulation through the leads. Length of each limb segment and width of limb joints were measured with a caliper.

In five cats, which were prepared for recording of the motor cortex activity, a portion of the skull and dura above the left motor cortex was removed and the motor cortex was identified by the surface features and photographed (Fig. 2A). The exposure was covered by a 1-mm-thick acrylic plate with holes of 0.36-mm diameter spaced 0.5 mm apart. Holes in the plate were prefilled with bone wax and allowed later insertion of recording electrodes into cortex in the awake animal. For the purpose of physiological identification of PTNs, two 26-gauge hypodermic guide tubes for a later insertion of stimulating electrodes into the pyramidal tract in the awake animal were implanted above the medullary pyramids so that their tips were approximately at the Horsley-Clarke coordinates (P7.5, L0.5) and (P7.5, L1.5), and the depth of H0. A ring-shaped plastic base resting on 10 screws implanted around the circumference of the scull served to affix connectors, a miniature microdrive, preamplifiers, and a protective cap with metal foil for electrical shielding. After all skin incisions were closed and pain medication was administered [fentanyl (transdermal patch 25 μg/h) and/or buprenorphine (0.01 mg/kg sc) or ketoprofen (2 mg/kg sc)], anesthesia was discontinued.

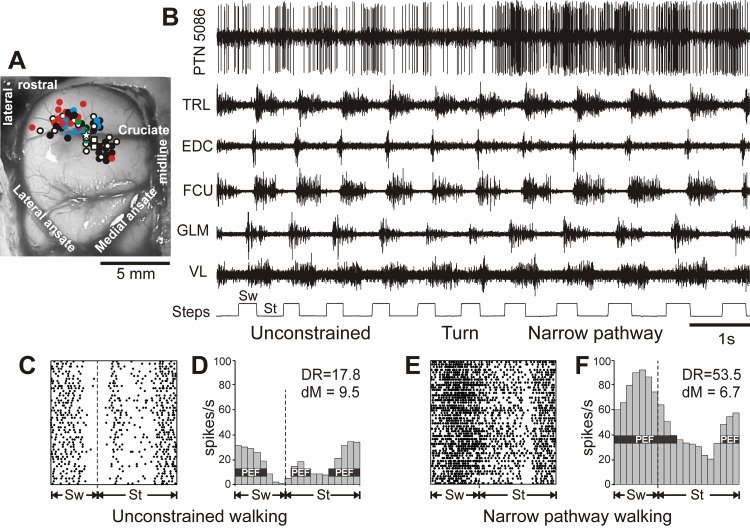

Fig. 2.

The area of recording in the motor cortex and an example of the activity of a neuron along with selected muscles during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A: areas of recording in the left motor cortex. Microelectrode entry points into the cortex were combined from all cats and are shown as circles on the photograph of cat Mc cortex: cat Mc entry points are depicted by white symbols, while those of cats Ba, Ko, Va, and Zv are shown by red, blue, green, and black symbols, respectively. Squares designate tracts where neurons with receptive fields spanning both the fore- and hindlimb were recorded. The star marks the track from which the neuron's activity shown in fragments B–F was recorded. B–F: an example of the activity of a neuron [pyramidal tract neuron (PTN)5086] and selected right fore- and hindlimb muscles during unrestrained and narrow-path walking. B: activity of the neuron and muscles during walking first with unconstrained paw placement and then, after a turn, along the narrow path. Bottom trace shows the swing (Sw) and stance (St) phases of the step cycle of the right forelimb that is contralateral to the recording site in the cortex. TRL, triceps brachii lateral head; EDC, extensor digitorum communis; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; GLM, gluteus medius; VL, vastus lateralis. C and D: the activity of the same neuron during unconstrained walking is presented as a raster of 50 step cycles (C) and as a frequency distribution histogram (D). The duration of step cycles is normalized to 100%. Vertical dashed lines indicate the end of the swing and the beginning of the stance phase. In the histogram, the horizontal black bar shows the period of elevated firing (PEF) as defined in methods. The average discharge rate (DR, spikes/s) and the depth of frequency modulation (dM, %) are shown. E and F: the raster and distribution of the activity of the same neuron during narrow-path walking.

Biomechanical and EMG Recordings

Full-body mechanical recordings during unconstrained walking have been described previously (Farrell et al. 2014; Prilutsky et al. 2005) and are only briefly outlined here. The three-dimensional (3D) positions of 28 markers placed on skin overlying major limb joints were recorded in five cats (Table 1) at 120 frames/s (Vicon Motion Systems; Fig. 1, A–C; for details see Beloozerova et al. 2010; Farrell et al. 2014). The ground reaction force vector and the coordinates of its point of application (center of pressure, CoP) were recorded in 3D at 360 Hz with three floor-embedded force platforms (Bertec). The accuracy of force recordings, determined as the range of force fluctuations around the baseline, was typically lower than 0.1 N for the anterior-posterior and medio-lateral force components and better than 0.3 N for the vertical component. During each experimental session, both unconstrained and narrow-path walking were recorded without changing positions of markers or the EMG cable attached. The EMG signals in these cats were collected with a shielded cable, sampled at 3,000 Hz, amplified, and saved on a hard drive of a PC computer for subsequent analysis. In three cats with cortical implants, EMG was preprocessed with preamplifiers in the cat backpack before the signal was saved on a PC. Examples of raw EMG signals recorded during unconstrained and narrow-path walking are shown in Fig. 2B. Biomechanics and EMG data collection lasted for 2–4 wk and started at least a month after the surgery.

Neuronal Recording and Identification

Extracellular single-neuron activity recordings were obtained from the rostral and lateral sigmoid gyrus (forelimb representation area) as well as from the postcruciate cortex within the fold of the cruciate sulcus (hindlimb representations) (Fig. 2A). These areas are considered to be the motor cortex based on a considerable body of data obtained by means of inactivation, stimulation, and recording techniques (Armstrong and Drew 1984a, 1984b, 1985a, 1985b; Beloozerova and Sirota 1993a; Drew 1993; Martin and Ghez 1985, 1993; Nieoullon and Rispal-Padel 1976; Phillips and Porter 1977; Vicario et al. 1983; Widajewicz et al. 1994). Recordings were obtained with tungsten varnish-insulated microelectrodes with outer diameter of 120 μm and impedance of 1–3 MΩ at 1,000 Hz (Frederick Haer). Electrodes were inserted into cortex through 0.36-mm holes in the plastic plate implanted above the cortex as explained above. The electrode was advanced into the tissue by means of a custom-made miniature manual microdrive (2.5 g) attached to the head base. The signals recorded at 30 kHz were preamplified by a miniature custom-made preamplifier on the cat's head and subsequently further amplified with a stationary CyberAmp 380 amplifier (Axon Instruments). The amplified signals were filtered (0.3–10 kHz band pass), fed to a screen and audio monitor, and saved on the hard drive of a PC computer with a Power1401/Spike2 data acquisition and analysis system (Cambridge Electronic Design). Examples of recordings from a PTN during unconstrained and narrow-path walking are shown in Fig. 2, B–F.

Each encountered neuron was tested for antidromic activation with pulses of graded intensity (0.2-ms duration, up to 0.5 mA) delivered through the bipolar stimulating electrode in the medullary pyramidal tract. Construction and insertion of this electrode have been detailed previously (Prilutsky et al. 2005). The cells that passed the test for collision of spikes (Bishop et al. 1962; Fuller and Schlag 1976; also see, e.g., Fig. 2 in Stout and Beloozerova 2013) were identified as PTNs. Each recorded neuron was tested for antidromic activation before, during, and after locomotion tests. In addition, waveform analysis was employed to identify and isolate the spikes of a single neuron with the Power1401/Spike2 system waveform-matching algorithm.

The distance between electrodes in the medullary pyramidal tract and at recording sites in the pericruciate cortex was estimated at 51.5 mm, which includes the curvature of the pathway as well as the spread of current and the refractory period at the site of stimulation. Neurons were classified as fast or slow conducting based on the criteria of Takahashi (1965): neurons with conduction velocity of 21 m/s or higher were considered to be fast conducting, whereas those with lower conduction velocities were considered to be slow conducting.

Somatic receptive fields of the neurons were tested while the animals were resting on a pad with their head restrained. Somatosensory stimulation was produced by palpation of skin, muscles, and tendons and by passive movements of joints. Responses of individual cells and populations of neurons were detected by listening to the output of the audio monitor. Neurons responsive to passive movements of joints were assessed for directional preference.

Neuronal recordings were obtained over periods of 4–16 wk and started 2.5–10 mo after the surgery.

Terminal Experiments

After completion of the experiments, the animals were deeply anesthetized and, in cats used for cortical activity recordings, several reference lesions were made in the motor cortex in the vicinity of areas from which neurons were recorded and in the pyramidal tract where stimulation electrodes were located. Cats were then euthanized with pentobarbital sodium and immediately perfused with isotonic saline followed by a 3% formalin solution. Frozen brain sections of 50-μm thickness were cut in the regions of recording and stimulating electrodes. The tissue was stained for Nissl substance with cresyl violet, and the positions of recording and stimulating electrodes were verified. The cadavers of cats were used to verify segment lengths and joint widths as well as locations of implanted EMG electrodes.

Kinematic and Kinetic Analysis

The full-body mechanical analysis has been described in detail previously (Farrell et al. 2014), and only a brief description is presented here. Only trials in which the cat maintained a steady forward walking speed were selected for analysis. Recorded markers' 3D coordinates were low-pass filtered (4th-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter, cutoff frequency 6 Hz). A limb plane for each frame of the gait cycle was determined with three markers on each limb (Fig. 1B, white circles) that defined the limb plane unit vector triad ulvlwl (Farrell et al. 2014):

| (1) |

where ul and vl are orthogonal unit vectors in the limb plane and wl is a unit vector orthogonal to the limb plane l (Fig. 1B); pl1, pl2, and pl3 are position vectors defining locations of three limb markers in the global coordinate frame OXYZ. Within this plane, the knee and elbow marker positions were recalculated to reduce errors caused by skin movement in these areas (see Goslow et al. 1973). The knee marker position was recalculated with measured shank and thigh lengths and the positions of the ankle and hip markers; the elbow marker position was recalculated with measured forearm and upper arm lengths and positions of the wrist and shoulder markers. The location of the distal limb joint centers [metatarsophalangeal joint (MTP), ankle, knee, metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP), wrist, elbow] and the location of digit/paw centers were computed by shifting the marker position along the vector perpendicular to the limb plane by a distance equal to the marker radius plus half the measured width of the joint (Fig. 1A). The hip and shoulder joint center positions were computed by shifting the marker position medially along the line connecting the two hip and two shoulder markers, respectively (Fig. 1A). The displacement of the general center of mass (CoM; Fig. 1) was calculated with an 18-segment body model (Fig. 1, A and B), the measured cat mass and segment lengths (Table 1), and the previously published regression equations for computing mass of individual segments (mi; Hoy and Zernicke 1985):

| (2) |

where pCoM is the positional vector describing the 3D location of the CoM of the full-body model in the global coordinate system at each video frame; pCoMi is the position of the center of mass location of segment i in the global coordinate system [pCoMi = ppi + λi(pdi − ppi)], where ppi and pdi are vectors describing positions of the proximal and distal joint centers of segment i; λi is the relative location of segment center of mass on the long segment axis (Hoy and Zernicke 1985); and m is total mass of the body.

Additional computed stride-related kinematic parameters included stride length; stance width; forward velocity of the CoM; stride, stance, and swing durations; and stride duty factor (ratio of stance duration over stride duration). Stance width was calculated as the paw center-to-paw center distance for the forelimbs and for the hindlimbs. Stance, swing, and stride durations were determined based on the times of paw contact with the ground and paw liftoff. The paw contact and liftoff times were determined with either the force plate measurements or the forward velocity of the paw (for details see Pantall et al. 2012) or, in experiments with cortical activity recordings, based on readings from the electromechanical sensor on the right forepaw.

Frontal plane angles and moments were calculated at the shoulder and hip joints. Shoulder ab/adduction angles were defined using the shoulder joint centers and the line from the shoulder center to the forepaw center (Fig. 1A; see also Misiaszek 2006). Hip ab/adduction angles were calculated similarly using the hip joint centers and the hindpaw center. The ab/adduction resultant muscle moments at the hip and shoulder joints (Mj) were calculated as the cross product of the position vector from the joint center to point of force application (pj) and the ground reaction force vector applied to the paw (F) (Farrell et al. 2014):

| (3) |

Equation 3 assumes negligibly small contributions of inertial terms in the dynamic equations of motion. This assumption was tested by comparing the sagittal-plane resultant joint moments during stance of walking computed with Eq. 3 and dynamic equations of motion and shown to be justified, as the difference in the computed joint moments did not exceed several percents of peak moments (see Fig. 6I in Farrell et al. 2014).

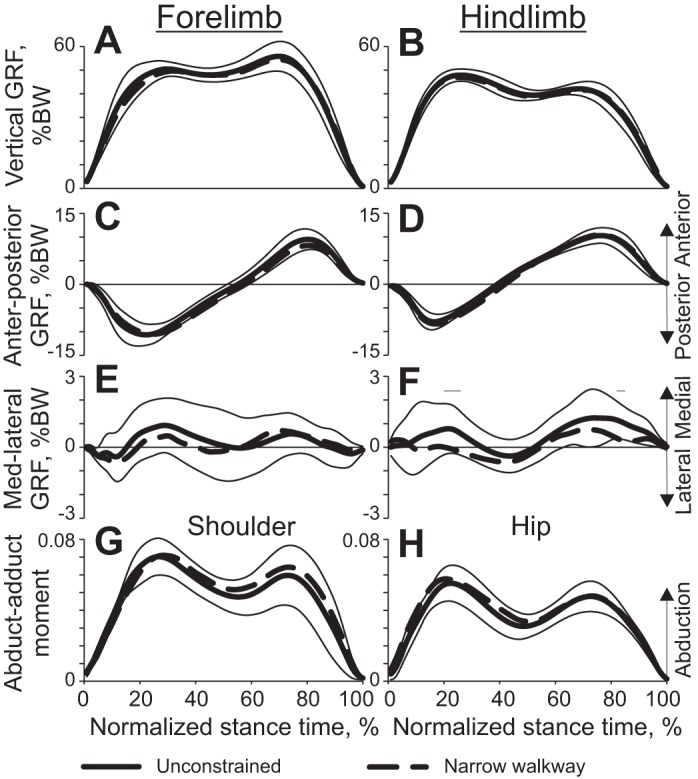

Fig. 6.

Selected kinetic variables (means ± SD) of unconstrained and narrow-path walking as functions of the normalized stance time (see Fig. 4 for definition of lines). Mean data of 5 cats (Table 1). Thin horizontal lines above panels indicate phases in which there is a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between narrow and unconstrained walking. A and B: vertical ground reaction force (GRF) applied to the fore- and hindlimbs, respectively. BW, body weight. C and D: anterior-posterior GRF applied to the fore- and hindlimbs. E and F: medial-lateral GRF applied to the fore- and hindlimbs. G and H: normalized frontal plane moment for the shoulder and hip joints, respectively. The moment (in Nm) is normalized to the cat's body mass and limb length.

Analysis of Body Stability

Static and dynamic stability was defined as margins of body stability, which were determined for each percent of the gait cycle. The static stability margin (or static stability index) was defined as the shortest distance between the projection of the CoM onto the ground and the border of base of support (Fig. 1D). The cat was considered statically stable at a given time instant if the CoM projection fell within the support area; otherwise the cat was considered statically unstable. To determine the margin of dynamic stability, the extrapolated center of mass position of the cat (XCoM) in the horizontal plane was calculated based on the previously published model (Hof et al. 2005):

| (4) |

where XCoM is a vector describing position of the extrapolated center of mass in the horizontal plane, pCoM and vCoM are the general CoM position and velocity vectors in the horizontal plane, ω0 = √g/l is the eigen (natural) frequency of the pendulum with mass equaled cat mass m suspended on a massless stick of length l equaled leg length (Table 1), and g is acceleration of gravity. The index (margin) of dynamic stability, IDS, was computed as the shortest distance between the projection of the XCoM onto the ground and the border of base of support (Fig. 1D). The cat was considered dynamically unstable if XCoM fell outside the support area (IDS < 0). The IDS was further broken down into two components representing indices of dynamic stability in the frontal (IDSf) and sagittal (IDSs) planes, respectively (Fig. 1D).

It should be pointed out that the IDS computed in this study is different from the measures of dynamic stability proposed in Hof et al. (2005, 2007). The latter are based on the distance between XCoM and the center of pressure (CoP). Since recording CoP for the entire stride was not possible with the three force plates available, we selected to use IDS as a measure of dynamic stability. When IDS crosses the border of the base of support (BoS) and becomes negative, CoP can no longer be moved in front of XCoM to reverse its movement away from an instability region, and thus the animal must make a step and place the paw in front of XCoM to prevent falling. Thus when IDS < 0, the animal is dynamically unstable (see condition C, p. 3 in Hof et al. 2005). When IDS is inside BoS (IDS > 0), it does not necessarily mean the animal is dynamically stable, especially if XCoM is close to the BoS border; this follows from the analysis of the inverted pendulum model provided by Hof et al. (2005).

Since it was not possible to measure the instantaneous magnitude and position of the point of application of the resultant vector of ground reaction forces applied to all legs on the ground during a single walking cycle with only three force plates, we computed the mean medio-lateral force (Fy) and position of resultant ground reaction force application (CoPy) for each percent of the walking cycle based on the mean force profiles (see Fig. 6, A–F) and timing of stance phases (Fig. 3, B and C) of each leg l:

| (5) |

where Fly and ply are the mean ground reaction force magnitude and center of paw position in the medio-lateral direction for the lth limb and Flz is the mean ground reaction force magnitude in the vertical direction for the lth limb.

EMG Analysis

EMG signals were sampled at 3,000 Hz. They were first band-pass filtered (30–1,000 Hz) and full-wave rectified. EMG activity onset and offset times were determined when the full-wave rectified activity crossed a threshold value defined as the mean EMG during a silent period plus 2 SDs (Gregor et al. 2006; Prilutsky et al. 2011). The mean EMG burst magnitude and duration were then calculated for all analyzed strides. EMG activity was normalized by the maximum among mean EMG burst values seen in a given muscle and animal across all strides of unconstrained walking. In addition, the full-wave rectified EMG signal was low-pass filtered by the 4th-order, zero-lag Butterworth filter with a cutoff frequency of 30 Hz to obtain a linear EMG envelope. The linear EMG envelopes were generated for each cycle, time normalized to stride duration, and averaged across all selected cycles.

Analysis of Cortical Activity

Paw ground contact by the right forelimb was detected with an electromechanical sensor on the right forepaw (Fig. 2B), and the stride duration was divided into 20 equal bins. For forelimb-related neurons, the onset of the swing phase of this limb was taken as the beginning of the stride. For hindlimb-related neurons, the beginning of the 16th bin of the forelimb cycle, which approximately corresponds to the beginning of the swing phase of the right hindlimb, was taken as the onset of the hindlimb stride cycle. For each neuron, a distribution of spike activity in the stride cycle was generated for each walking task (e.g., Fig. 2, D and F). Phase distributions of spike activity were smoothed by recalculating the values of the bins according to the equation = 0.25·Fn−1 + 0.5·Fn + 0.25·Fn+1, where Fn is the bin's original value. The first bin in the cycle was considered to follow the last bin, and the last bin was considered to precede the first bin. The “depth” of modulation, dM, characterizing fluctuation in probability of the discharge, was calculated as dM (%) = (Nmax − Nmin)/N × 100, where Nmax and Nmin are the numbers of spikes in the maximal and minimal histogram bins and N is the total number of spikes in the histogram. Neurons with dM > 4% were judged to be stride related. This was based on an analysis of fluctuations in the activity of neurons in the resting animal (Efron and Tibshirani 1993; Marlinski et al. 2012). In stride-related neurons, the period of elevated firing (PEF) was defined as the portion of the cycle in which the activity level exceeds the minimal activity by 25% of the difference between the maximal and minimal frequencies in the neuronal discharge histogram (Fig. 2, D and F). PEFs were smoothed by removing all one-bin peaks and troughs (a total of 0.4% of bins were altered throughout the database). The “preferred phase” of discharge of each neuron with a single PEF was assessed with circular statistics (Batshelet 1981; Drew and Doucet 1991; Fisher 1993; Sirota et al. 2005).

The following parameters were calculated for each recorded neuron: mean discharge frequency, dM, number of PEFs, duration of PEF(s), and, for neurons with a single PEF per cycle, the preferred cycle phase. For populations of neurons the following parameters were calculated: proportion of neurons at their PEF during different phases of the locomotion cycle, distribution of average population discharge frequency over the cycle, range of coefficients of modulation, and average widths of PEFs. The difference in all parameters of the activity of individual neurons and populations of neurons between unconstrained and narrow-path walking was evaluated.

Statistical Analysis

The effects of walking conditions on general characteristics of walking mechanics, EMG, and motor cortex activity were assessed with the linear mixed model (LMM) analysis (Brown and Prescott 2006; West et al. 2015) in the IBM SPSS statistics software (Chicago, IL). During analyses of walking mechanics and EMGs, the walking condition (unconstrained or narrow) was considered a fixed factor; the cats and walking cycles were random factors. For post hoc comparisons the Bonferroni test was used. Differences in time-dependent mechanical variables and EMG linear envelopes between unconstrained and narrow-path walking at each percent of the walking cycle were tested with the paired Student's t-test applied to the means obtained by averaging the values across all studied walking cycles within each cat. During the analysis of motor cortex activity the walking condition and limb were fixed factors, whereas cat and stride were random factors. In addition, when comparing depth of frequency modulation dM of individual neurons, their preferred phases, and duration of PEF, differences equal to or greater than 2%, 10%, and 20%, respectively, were considered significant. These criteria were established based on the results of a bootstrapping analysis (Efron and Tibshirani 1993; Stout and Beloozerova 2013) that compared differences in discharges between various reshufflings of strides of the same locomotion task. Data on mechanical variables, EMG linear envelopes, EMG burst magnitude, and EMG burst duration are reported as means ± SD. When data on the mean activities of populations of motor cortical neurons are compared, the results are presented as means ± SE. The difference between two proportions was evaluated by Z-test for proportions. When data were categorical, a nonparametric Mann-Whitney (U) or Fisher's two-tailed (F) test was used. The significance level for all tests was set at 0.05.

RESULTS

In total, 227 strides from five cats were used for mechanical analysis of unconstrained and narrow-path walking, and 779 strides from eight cats were used for analysis of EMG (Table 1). The activity of 174 neurons from the right fore- and hindlimb representations of the motor cortex in five cats was recorded and analyzed using 20–150 strides of each locomotion task for each neuron.

Mechanics of Walking Along Narrow Path

General stride characteristics.

The average stance width for the forelimbs (1.66 ± 0.84 cm; LMM estimated mean ± SD) and hindlimbs (0.99 ± 0.73 cm) during walking along the narrow path was smaller than during unconstrained walking (2.67 ± 0.83 cm and 2.42 ± 0.71 cm; P < 0.05, F4,218 = 97.9 and F4,218 = 117.3, for fore- and hindlimb, respectively). On average, the mean walking speed was slightly lower during narrow-path walking than during unconstrained walking (0.546 ± 0.077 m/s and 0.619 ± 0.077; mean ± SD, F4,218 = 59.3, P < 0.05). Correspondingly, the stride, stance, and swing durations and the duty factor for fore- and hindlimbs during narrow walking slightly exceeded those of unconstrained walking (Fig. 3A; F4,442 = 15.6–169.3, P < 0.05).

The limb support pattern (sequence of phases with different number of limbs on the ground) was similar between narrow-path and unconstrained walking: 2-3-2-3-2-3-2-3 (Fig. 3, B and C). The number of limbs in contact with the ground at a given time determined the area of support and body static stability (see below). The area of support during both narrow-path and unconstrained walking was the smallest during cycle phases with two limbs on the ground (phases 1, 3, 5, and 7; Figs. 3 and 4, Tables 2 and 3), especially when the contralateral fore- and hindlimbs were in support (phases 3 and 7). The minimum support area during the stride of narrow-path walking was similar to that of unconstrained walking, whereas the maximum support area was smaller (F4,218 = 192.2, P < 0.05; Figs. 3 and 4, Table 2). The normalized duration of the double-support phases was shorter while the normalized duration of the three-legged support phases was longer during narrow-path compared with unconstrained walking (F4,214 = 6.6–52.6, P ≤ 0.05; Table 3).

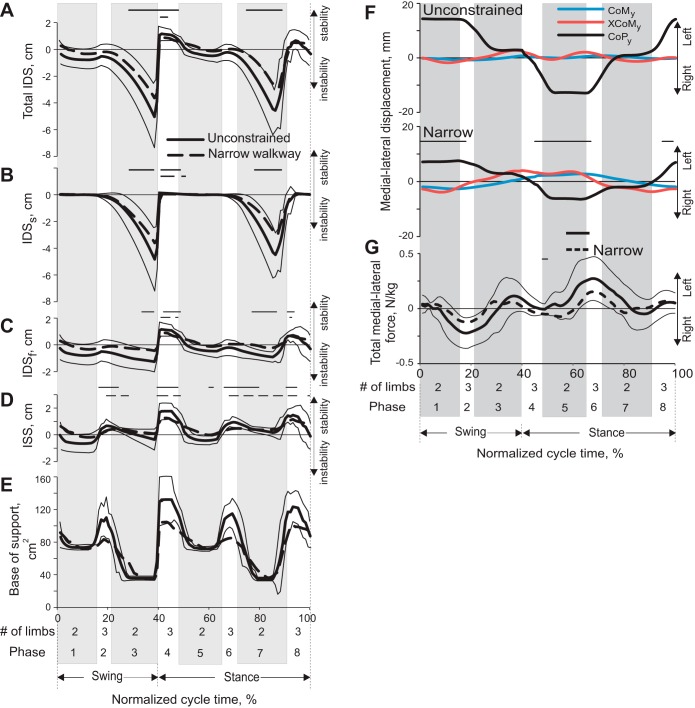

Fig. 4.

Indices of static and dynamic stability (means ± SD) during a stride of unconstrained and narrow-path walking. Thick continuous lines, mean for unconstrained walking; thick dashed lines, narrow walking; thin continuous lines, SD for the mean of the unconstrained condition. x-Axis is the normalized stride time of the right forelimb; 0% corresponds to swing onset of the right forelimb; 8 cycle phases are the same as in Fig. 3. Solid and dashed horizontal bars indicate phases in which a variable for unconstrained and narrow walking is significantly (P < 0.05) different from 0. Negative values of indices of stability indicate instability. Mean data from 5 cats (see Table 1). A: IDS (see Fig. 1 and text for explanations) averaged across studied strides and cats. B: IDSs. C: IDSf. D: ISS. E: base of support area. F: mean position of the center of mass (CoMy), extrapolated center of mass (XCoMy), and center of pressure (CoPy) in the y-direction (see Fig. 1B) during unconstrained and narrow walking. Thin horizontal lines indicate statistically significant (P < 0.05) differences in CoP between the 2 walking tasks. G: resultant ground reaction force in the y-direction during unconstrained walking (mean, continuous line ± SD, thin lines) and narrow-path walking (dashed line). Mean data of 5 cats.

Table 2.

Characteristics of dynamic stability during the cycle of unconstrained and narrow-path walking

| Stability Parameter | Unconstrained Walking | Narrow-Path Walking |

|---|---|---|

| Maximal IDS, cm | 1.61 ± 0.24 | 1.36 ± 0.24 |

| Minimal IDS, cm | −6.68 ± 2.23 | −5.15 ± 0.24* |

| Peak lateral CoM acceleration, cm/s2 | 59.8 ± 11.3 | 55.1 ± 11.6* |

| Max BoS area, cm2 | 145.2 ± 16.7 | 116.1 ± 16.8* |

| Min BoS area, cm2 | 31.6 ± 1.9 | 31.2 ± 2.0 |

Values are means ± SD. CoM, center of mass; IDS, index of dynamic stability; BoS area, base of support area.

Significant difference between unconstrained and narrow-path walking.

Table 3.

Area of support and normalized duration of support phases during unconstrained and narrow-path walking

| Area of Support, cm2 |

Normalized Time, % |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Limbs in Support | Support Phase No. | Unconstrained walking | Narrow-path walking | Unconstrained walking | Narrow-path walking |

| 1 | 2 | 76.7 ± 4.1 | 74.1 ± 4.9 | 16.8 ± 3.0 | 15.6 ± 3.1* |

| 2 | 3 | 113.1 ± 14.9 | 92.8 ± 15.3* | 7.2 ± 2.2 | 8.5 ± 2.3* |

| 3 | 2 | 39.9 ± 5.8 | 38.9 ± 6.5 | 15.6 ± 2.6 | 13.0 ± 2.7* |

| 4 | 3 | 122.7 + 17.0 | 97.4 + 17.4* | 11.7 ± 2.5 | 13.3 ± 2.5* |

| 5 | 2 | 75.6 + 4.1 | 73.4 + 4.9 | 15.5 ± 2.0 | 14.1 ± 2.1* |

| 6 | 3 | 113.0 + 9.5 | 90.9 + 10.1* | 7.8 ± 1.8 | 9.8 ± 1.9* |

| 7 | 2 | 40.6 + 6.1 | 37.6 + 6.9 | 15.9 ± 1.3 | 13.1 ± 1.6* |

| 8 | 3 | 118.2 + 13.3 | 97.5 + 13.9* | 9.5 ± 2.4 | 12.5 ± 2.4* |

Values are means ± SD. Normalized time is % of cycle time.

Significant difference between unconstrained and narrow-path walking.

Body stability during walking along narrow path.

Indices of static (ISS) and dynamic (IDS) stability fluctuated during the walking cycle in accordance with the limb support pattern and the support area. In three-legged support phases (phases 2, 4, 6, and 8; Fig. 3) the ISS and the IDS, with its frontal (IDSf) and sagittal (IDSs) components, were either positive or near zero during both narrow-path and unconstrained walking, i.e., the cat was statically stable (Fig. 4, A–E). In double-support phases of both narrow-path and unconstrained walking (phases 1, 3, 5, and 7), the static stability (ISS) and dynamic frontal stability (IDSf) indices were generally nonnegative and there was no difference between the two tasks (P > 0.05, Fig. 4, A–E). Thus both narrow-path and unconstrained walking were statically stable in the frontal plane during these stride phases. The cat was dynamically unstable in the sagittal plane, however, during the double-support phases by contralateral fore- and hindlimbs (phases 3 and 7): the peak margin of dynamic instability (or minimal IDS) was −5.15 ± 0.24 cm (LMM, mean ± SD) for narrow-path walking and −6.38 ± 2.23 cm for unconstrained walking (Table 2, Fig. 4, A–E). The peak values of IDS were statistically different between the two tasks during these stride phases (F4,218 = 39.3, P < 0.05), but the difference was relatively small (Table 2).

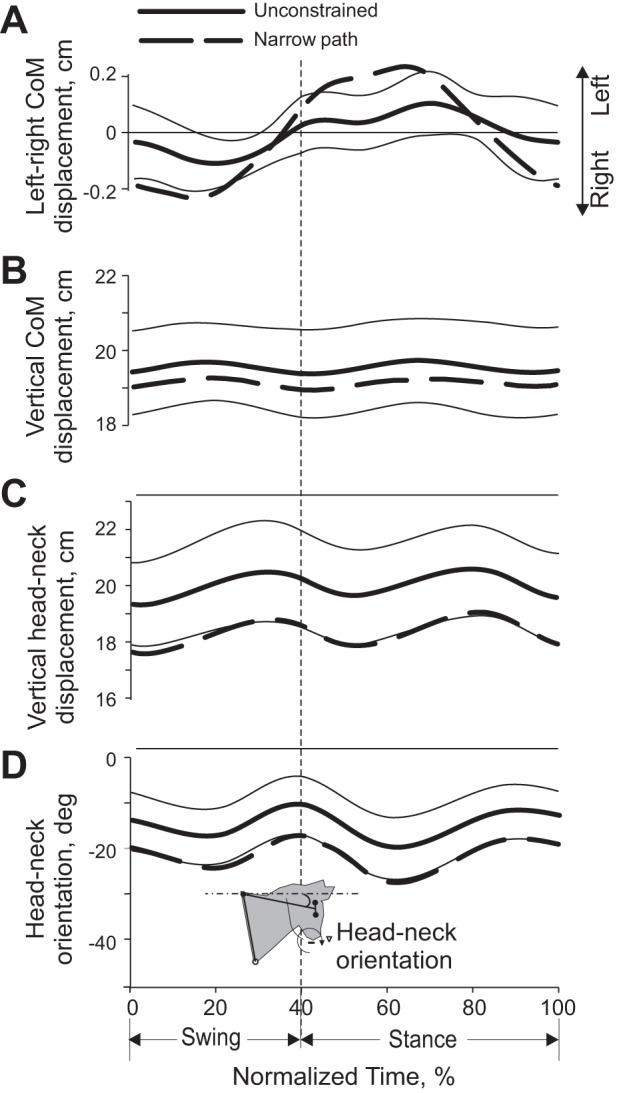

Although there was no substantial difference in static and dynamic frontal stability between narrow-path and unconstrained walking, the range of CoM displacement toward the left and right sides of the cat had a tendency to be larger during narrow-path walking (up to 0.4 cm) than during unconstrained walking (which was close to 0.2 cm; Fig. 4F and Fig. 5A); however, this difference did not reach the level of statistical significance. The peak CoM displacement in the left and right directions occurred at 10–25% and 60–75% of the right forelimb stride during double-support phases by the right fore- and hindlimb and the left fore- and hindlimb, respectively (see Fig. 3, Fig. 4, A–E, and Fig. 5A, phases 1 and 5). The CoM frontal plane positions were closest to the midline of the cat body during the transition from a double support by diagonal fore- and hindlimbs (phases 3 and 7) to a three-legged support provided by two forelimbs and one hindlimb (phases 4 and 8; Fig. 3, Fig. 4, F and G, and Fig. 5A). Vertical displacement of the CoM was synchronized with left-right CoM displacement during both narrow and unconstrained walking (Fig. 5B): the CoM reached peak vertical positions during the phases of maximum CoM deviations from the body midline (phases 2 and 6), whereas the CoM lowest position occurred during the phases with the minimum CoM deviation from the body midline. Interestingly, just prior to reaching the lowest CoM position at 50% and 100% of cycle time, the body was most dynamically unstable in the anterior direction (IDS reached its negative peak for both narrow and unconstrained walking; Table 2, Fig. 4, A and B) because of relatively high forward CoM velocity (not shown) and a small support area (Table 3, Fig. 4E). The recovery of dynamic stability was achieved by a forelimb that contacted the ground rostral to the XCoM and “caught” the CoM moving forward and downward.

Fig. 5.

Selected mechanical variables (means ± SD) during a stride of unconstrained and narrow-path walking. Thick continuous lines, mean for unconstrained walking; thick dashed lines, narrow walking; thin continuous lines, SD for the mean of the unconstrained condition. Mean data of 5 cats (Table 1). Thin horizontal lines above panels indicate phases in which there is a statistically significant difference (P < 0.05) between narrow and unconstrained walking. A: displacement of the CoM in the left and right directions; left direction corresponds to the left side of the body. B: vertical displacement of the CoM. C: vertical displacement of the head-neck segment. D: head-neck segment orientation; clockwise segment rotation from the horizontal is defined as negative.

There was a small trend for the CoM vertical position to be lower during narrow-path walking; however, this trend did not reach the level of statistical significance (paired t-test, P > 0.05; Fig. 5B). The vertical position of the head-neck segment was, however, significantly lower during narrow-path walking than unconstrained walking by ∼1 cm throughout the stride (Fig. 5C). The pattern of vertical displacement of this segment was similar to that of the CoM (both had 2 peaks and 2 nadirs) but was slightly delayed in phase. The head-neck segment was also more rotated from the horizontal line to the ground throughout the whole stride of narrow-path walking (paired t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 5D).

Other mechanical characteristics of locomotion along narrow path.

The ground reaction forces acting on the cat's body determined motion of the CoM. The three orthogonal components of the ground reaction force vectors applied to the fore- and hindlimbs were similar between narrow-path and unconstrained walking (paired t-test, P > 0.05; Fig. 6). No difference in the peak vertical and anterior-posterior forces were found between narrow-path and unconstrained walking (paired t-test, P > 0.05). The medio-lateral forces applied to fore- and hindlimbs during both narrow and unconstrained walking were relatively small (typically <1% of body weight). Throughout most of the stance, this force was directed medially, which corresponded to exerting force by the limb on the ground in the lateral direction. The values of these forces were similar between narrow-path and unconstrained walking except during two short periods of stance, in which the hindlimb exerted a greater lateral force on the ground during unconstrained walking than in narrow-path walking (paired t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 6F). The resultant medio-lateral forces computed by summing the medio-lateral forces applied to each limb had a trend to be smaller during narrow-path walking, but this trend did not typically reach statistical significance (paired t-test; Fig. 4G).

The patterns of shoulder and hip muscle moments in the frontal plane resembled the patterns of the vertical ground reaction forces (Fig. 6, G and H). Throughout the stance phase, the moment direction was in abduction, which means that the resultant action of all muscles around the shoulder and the hip in the frontal plane tended to abduct the limb in contact with the ground and thus contributed to body medial acceleration. No difference in muscle moment magnitude was found between narrow and unconstrained walking (paired t-test, P > 0.05).

The shoulder and hip joint angles in the frontal plane fluctuated around 90° and had a rather small range of motion between 10° and 15° for both narrow-path and unconstrained walking (Fig. 7, A and B). The shoulder and hip frontal plane angles averaged across the walking cycle of narrow walking (83.9 ± 1.7° and 84.8 ± 1.3°, respectively; LMM, mean ± SD) were slightly more adducted than the corresponding angles during unconstrained walking (85.5 ± 1.4° and 86.7 ± 1.1°; F4,446 = 8.4–17.4, P ≤ 0.05). During most of stance of narrow and unconstrained walking the hindlimbs were slightly adducted, and in midswing the hindlimbs were slightly abducted. This pattern of frontal angles was consistent with hindlimb circumduction during swing, which resulted in lateral displacement of hindpaws by ∼2.5 cm (see Fig. 7D). Lateral displacements of forelimbs were slightly smaller (Fig. 7C). Vertical paw displacements were higher in midswing during narrow compared with unconstrained walking, which was especially apparent for the hindlimbs (paired t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 7, E and F).

Fig. 7.

Limb joint angles and paw linear displacement (means ± SD) as functions of the normalized stride time during unconstrained and narrow-path walking (see Fig. 4 for definition of lines). Mean data of 5 cats (Table 1). Thin horizontal lines indicate statistically significant differences (P < 0.05) between narrow and unconstrained walking. Vertical dashed line separates the swing and stance phases. A and B: shoulder and hip frontal plane angles, respectively. C and D: medial-lateral displacement of the fore- and hindpaws, respectively. E and F: vertical displacement of the fore- and hindpaws, respectively. G–J: angles at the metacarpophalangeal (MCP), metatarsophalangeal (MTP), wrist, and ankle joints, respectively, in the sagittal plane (for definition of angles see insets).

Patterns of joint angles at the proximal limb joints (shoulder, elbow, hip, knee) in the sagittal plane were similar between narrow-path and unconstrained walking (P > 0.05; results not shown). Patterns of joint angles at distal joints (wrist, MCP, ankle, MTP) showed only minor differences between the tasks (Fig. 7, G–J).

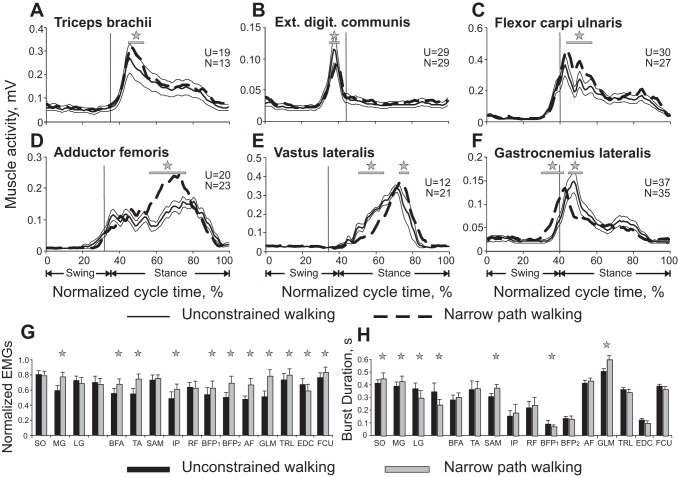

Muscle Activity During Walking Along Narrow Path

EMG activity from 14 hindlimb and 3 forelimb muscles was recorded in eight cats during narrow-path and unconstrained walking (Table 1). Hindlimb EMG patterns during narrow-path walking were qualitatively similar to those of unconstrained walking (see representative examples in Fig. 2B and Fig. 8, D–F). Specifically, extensor muscles SO, MG, LG, VM/VL, BFA, and AF were active during stance; two-joint RF and biceps femoris (BFP) muscles demonstrated their typical activity at the transition from swing to stance (burst BFP1) and from stance to swing (BFP2); and swing-related EMG activity occurred in flexors (TA, IP, SAM). Across all cats in which activity of these muscles was recorded (n = 3–8 depending on muscle; see methods and Table 1), the EMG magnitude in many muscles was generally larger during narrow-path than unconstrained walking (Fig. 8, G and H). Some of the studied muscles have a function in adduction and abduction. The AF (hip extensor and adductor) and GLM (hip extensor and abductor) were both active during stance, and their mean EMG activity was higher during narrow-path than during unconstrained walking (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8, D and G). The MG (ankle extensor and abductor) (Lawrence et al. 1993) produced higher activity during narrow walking and had a significantly larger EMG burst duration (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8, G and H). The SO and LG (ankle extensors) demonstrated longer burst duration during narrow-path walking (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8H). The burst duration of the extensors VM/VL was shorter, however, during narrow-path than during unconstrained walking (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8H), and the burst activity of BFA (hip extensor) was higher (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8G). The flexors TA and IP and both bursts of BFP (BFP1 and BFP2) had a greater activity during narrow-path walking (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8G), with BFP1 also being shorter (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8H). The burst duration of SAM (hip and knee flexor) was longer during narrow-path walking (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8H).

Fig. 8.

Muscle EMG activity during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A–F: each panel shows a representative EMG activity of a forelimb (A–C) or a hindlimb (D–F) muscle. For each muscle, data for the 2 locomotor tasks were recorded during the same recording session and averaged over 12–37 strides for each task. See Fig. 4 for definition of lines. These examples were obtained from different cats and recording sessions. Vertical dashed lines separate the swing and stance phases. Horizontal lines and stars denote significant differences (P < 0.05) between the conditions at corresponding time bins (Student's unpaired t-test was applied to each of the 100 bins of the EMG activity envelopes). G and H: normalized mean (±SD) EMG burst magnitude and burst duration, respectively, for unconstrained and narrow-path walking across all cats. The numbers of strides obtained from individual cats are listed in Table 1. Stars indicate statistically significant difference [linear mixed model (LMM), P < 0.05] between the 2 walking tasks. SO, soleus; MG, medial gastrocnemius; LG, lateral gastrocnemius; VM, vastus medialis; BFA, biceps femoris anterior; TA, tibialis anterior; SAM, sartorius medial; IP, iliopsoas; RF, rectus femoris; BFP1 and BFP2, biceps femoris posterior bursts 1 and 2; AF, adductor femoris.

Forelimb EMG activity was recorded from TRL (elbow extensor), EDC (dorsi-flexor of wrist and digits), and FCU (wrist plantar flexor). Representative examples are shown in Fig. 2B and Fig. 8, A–C. Across the cats in which activity of these muscles was recorded (see methods and Table 1) the mean activity of TRL and FCU was slightly higher during narrow-path than unconstrained walking (by 7–8%), while the activity of EDC was smaller by a similar amount (LMM, P < 0.05; Fig. 8, A–C and G). The duration of activity bursts in all three forelimb muscles of all cats was similar between the two walking tasks (Fig. 8, A–C and H).

Characteristics of Neurons

Neuronal data were collected from a total of 63 tracks through the left motor cortex of five cats (3–23 tracks per cat; Fig. 2A). These data were considered together to analyze the activity of 174 neurons (12–64 neurons per cat). One hundred fourteen neurons were recorded from the motor cortex forelimb representation and 60 from the representation of the hindlimb. Based on cytoarchitectural features, it was determined that all neurons were located in layer V of the motor cortex area 4γ. One hundred and fifty-six cells responded to stimulation of the pyramidal tract. The latencies of responses ranged from 0.7 to 6 ms. Estimated conduction velocities were between 8.5 and 73 m/s. Among responding neurons 69% (108/156) responded at 2.0 ms or faster, conducting at 25 m/s or faster, and thus were “fast-conducting” PTNs, whereas 31% (48/156) were “slow-conducting” PTNs (Takahashi 1965).

Ninety-eight neurons had a receptive field on the forelimb, 59 had a receptive field on the hindlimb, and 7 neurons responded to stimulation of both the forelimb and hindlimb. Somatosensory receptive fields of all neurons were located on the contralateral (right) side of the body, and all but four were excitatory. From neurons responding to the forelimb, 25 were activated by passive movements of the shoulder, 16 responded to movements in the elbow joint, and 24 were activated by movements of the wrist or palpation of the paw. In addition, 30 neurons responded to movement in two joints [either both shoulder and elbow (n = 6) or elbow and wrist (n = 8)] or had a receptive field spanning the entire forelimb (n = 16). Seven neurons had a cutaneous receptive field, five of which had also a joint-related field. Cutaneous receptive fields of four neurons included the wrist and/or paw. Neurons activated by a passive movement in a joint typically had a preferred direction. One-third (n = 9) of shoulder-related cells responded to abduction of the shoulder, occasionally in conjunction with its extension, while others responded to extension (n = 4), flexion (n = 4), or adduction (n = 3) of the joint. From elbow-related cells, five neurons responded to flexion of the joint and two responded to its extension. From wrist-related neurons, three responded to the wrist plantar flexion whereas four were activated by the wrist dorsal flexion.

From neurons responding to stimulation of the hindlimb, nine were activated by passive movements of the hip, seven responded to movement of the knee or a touch to the skin on the back of the knee joint, and nine were activated by movements of the ankle or palpation of the paw. In addition, 26 neurons responded to movement in two joints, typically knee and ankle (n = 9), or had a receptive field spanning the entire hindlimb (n = 12). Five of the hip-related cells preferentially responded to flexion, two in conjunction with adduction and two in conjunction with abduction. From ankle-related neurons, three responded to flexion and one to extension. Eleven neurons had a cutaneous receptive field on the knee and either the ankle or hip; in four cases these fields were confined to the inner surface of the leg.

An example of activity of a neuron during unconstrained and narrow-path walking is shown in Fig. 2B along with activities of selected muscles. This neuron was recorded from the motor cortex forelimb representation region and was responsive to passive movements in all forelimb joints (in Fig. 2A the microelectrode track in which this neuron was recorded is indicated with a star). The raster plots in Fig. 2, C and E, show the activity of the neuron across 50 strides during unconstrained (Fig. 2C) and narrow-path (Fig. 2E) walking. The activity is summed in Fig. 2, D and F, which show corresponding distributions of firing rate across the stride cycle. The period of elevated firing (PEF; see definition in methods) is indicated by a black horizontal bar. One can see that the discharge of the neuron was modulated in the rhythm of strides during both locomotor tasks. During unconstrained walking, the neuron was preferentially active during the end of the stance phase and throughout the first two-thirds of the swing while discharging at a very low rate in the end of the swing phase. There was a second small PEF in the beginning of the stance phase. During walking along the narrow path, the neuron's activity in the swing phase dramatically increased, especially in the end of this phase where it was previously silent; the discharge rate in the beginning of stance also rose. As a result, the neuron discharged one long and much more intensive PEF throughout all of the swing and some of the stance phases.

A LMM analysis of parameters of motor cortex activity conducted on all recorded cells together to examine the effects of two fixed factors, walking condition (unconstrained and narrow path) and limb (forelimb and hindlimb), revealed no statistical differences in the mean firing rate, activity modulation, preferred phase, and number of PEF phases (P > 0.05). Therefore, further analysis was conducted on the mean activity of the individual neurons calculated across multiple strides for each neuron and time bin.

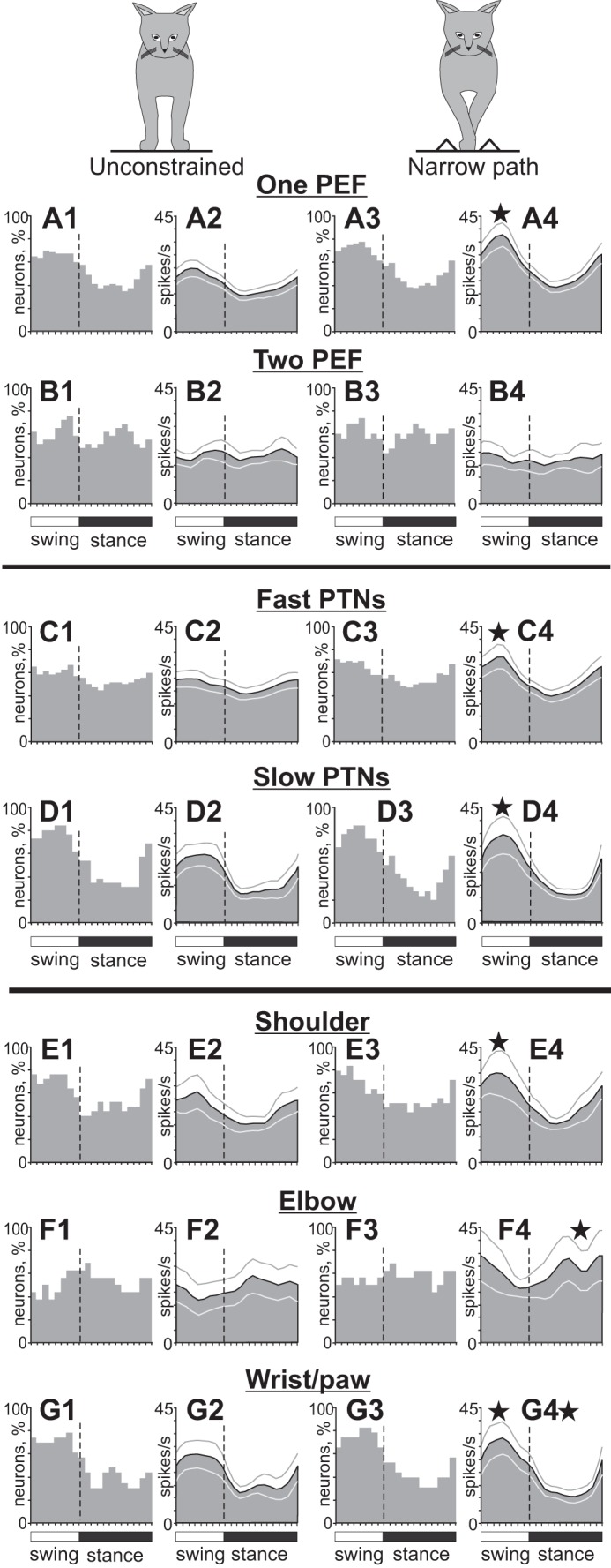

Activity of Neurons During Unconstrained Walking

Forelimb-related neurons.

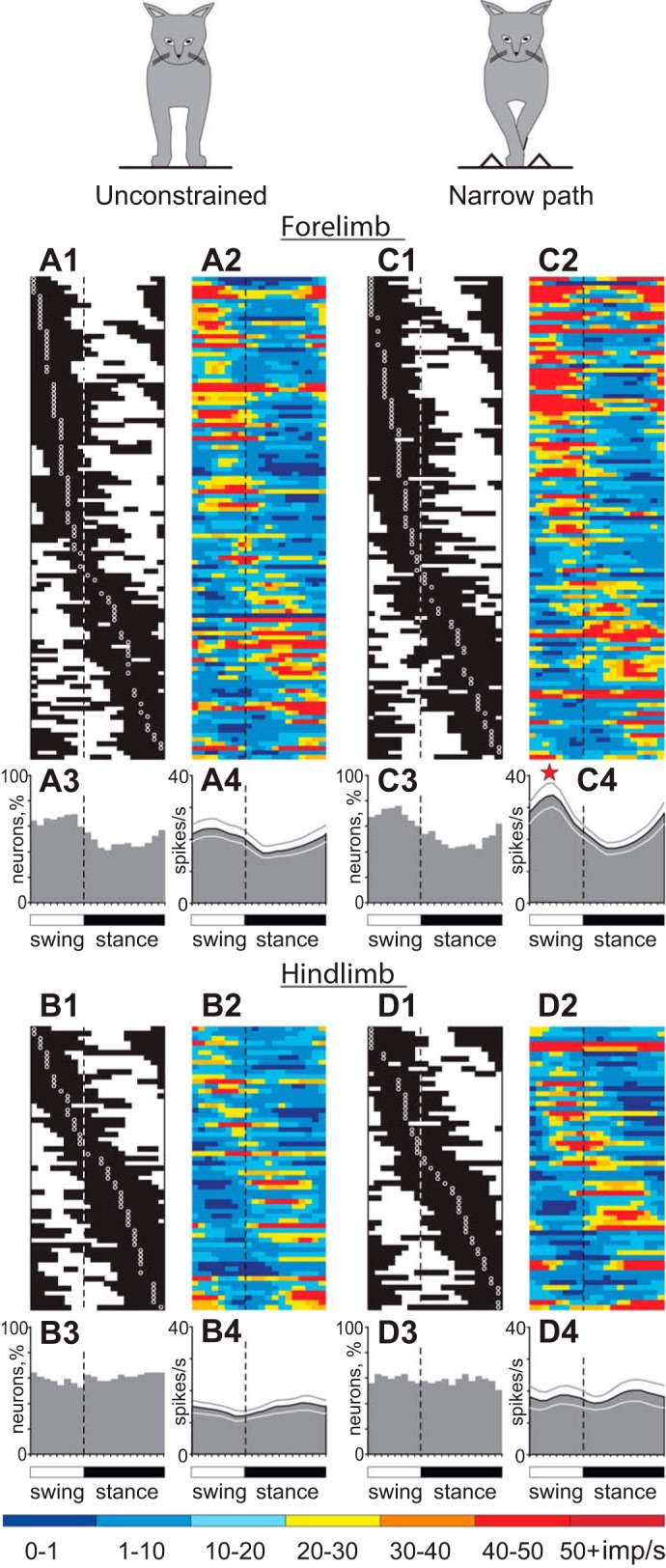

The mean activity of the forelimb-related population during unconstrained walking was 15.5 ± 1.0 spikes/s (mean ± SE). The discharge rate of 96% (109/114) of cells was modulated in the rhythm of strides: it was higher in one phase of the stride and lower in another phase. Of these, the majority of neurons (73%, 80/109) had a single PEF, whereas 27% (29/109) showed two PEFs. The activity of neurons in the one-PEF group was more modulated than that of two-PEF cells (dM = 11.9 ± 0.6 vs. 9.3 ± 0.6 spikes/s, respectively, t-test, P < 0.05). PEFs of both groups of neurons were distributed across the stride cycle (Fig. 9, A1 and A2). The average duration of the PEF was 55 ± 1.5% of the stride cycle. In two-PEF neurons the activity was typically split into a longer PEF occupying ∼40% of the cycle and a shorter PEF for <20% of the cycle. Because of a relatively long duration of PEFs and their wide distribution across the cycle, PEFs of different neurons overlapped and between 40% and 65% of cells were simultaneously active in most phases of the cycle (Fig. 9A3 and Fig. 10, A1 and B1). There were, however, slightly more neurons with PEFs during the swing phase of the stride (F-test, P < 0.05), and they were more active. As a result, the entire population was more active during the first half of the swing phase, firing at a mean peak rate of 24.7 ± 3.2 spikes/s as opposed to the mean minimum rate of 14.0 ± 1.8 spikes/s at the beginning of the stance phase (U-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 9A4). The one-PEF neurons were the ones that chiefly contributed to such modulation of the population activity (Fig. 10A2), as the activity of the two-PEF neurons as a group was largely steady across the cycle (Fig. 10B2). The group of slow-conducting PTNs had a substantially more modulated activity compared with fast-conducting PTNs (Fig. 10, D1 and D2 vs. C1 and C2). Neurons with receptive fields related to different joints differed in their stride-related activity. Shoulder- and wrist-related cells as groups preferred to discharge during the swing phase; their average population peaks were at ∼27 spikes/s, and dips went to ∼15 spikes/s during the stance phase (Fig. 10, E1 and E2 and G1 and G2). In contrast, in the elbow-related group more neurons were active during transition from the swing to the stance phase (Fig. 10F1), and this group tended to discharge more intensively during the stance phase (Fig. 10F2).

Fig. 9.

Population characteristics of forelimb-related (A and C) and hindlimb-related (B and D) neurons during unconstrained (A and B) and narrow-path (C and D) walking. A1 and C1: phase distribution of PEFs of all forelimb-related neurons during unconstrained (A1) and narrow-path (C1) walking. Each row represents PEF of 1 cell. A circular mark on a PEF denotes the preferred phase for cells with a single PEF per stride cycle. Neurons are rank-ordered so that those with a PEFs earlier in the cycle are plotted at top of the graph. Vertical dashed lines separate the swing and stance phases. A2 and C2: corresponding phase distributions of discharge frequencies. The average discharge frequency in each 1/20th portion of the cycle is color-coded according to the scale shown at bottom of figure. A3 and C3: proportion of active forelimb-related neurons (neurons in their PEF) in different phases of the step cycle during unconstrained (A3) and narrow-path (C3) walking. A4 and C4: mean discharge rate of forelimb-related neurons during unconstrained (A4) and narrow-path (C4) walking. Thin lines show SE. The star indicates that the activity of the population in the swing phase was significantly different (P < 0.05) between narrow-path and unconstrained walking. B1–B4 and D1–D4 show characteristics of hindlimb-related neurons during unconstrained (B1–B4) and narrow-path (D1–D4) walking.

Fig. 10.

Population characteristics of forelimb-related neurons during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A: neurons with 1 PEF per stride. B: neurons with 2 PEFs per stride. C: PTNs with fast axonal conduction velocities. D: PTNs with slow axonal conduction velocities. E: neurons responsive to passive movements in the shoulder joint. F: neurons responsive to passive movement of the elbow joint or palpation of arm muscles. G: neurons responsive to passive movement in the wrist joint or palpation of muscles on the forearm or paw. Other designations are as in Fig. 9.

Hindlimb-related neurons.

The mean activity of hindlimb-related neurons during unconstrained walking was 14.2 ± 1.2 spikes/s (this group also included 7 cells with receptive fields stretched over both the fore- and hindlimb). This was similar to the average activity of forelimb-related neurons. Fast-conducting PTNs were more active than slow-conducting PTNs at 16 ± 1.8 vs. 10.7 ± 1.3 spikes/s (P = 0.05; Fig. 11, A1 vs. B1). The discharge rate of 98% (59/60) of hindlimb-related cells was modulated in the rhythm of strides. However, unlike the forelimb-related neurons, more than a quarter of which discharged two PEFs per stride, 93% (55/59) of neurons in the hindlimb-related population had only one PEF (Z-test, P < 0.05). The average duration of the PEF across all hindlimb-related neurons was 60.5 ± 2.5%, and PEFs of different neurons were evenly distributed across the cycle (Fig. 9, B1 and B2). PEFs of different neurons overlapped, and ∼60% of neurons were simultaneously active in all phases of the stride (Fig. 9B3), so the activity of the entire population was only slightly modulated, with a peak of 15.6 ± 0.2 spikes/s during the second half of the stance phase and a minimum of 12.5 ± 0.3 spikes/s during the second half of the swing phase (P = 0.05; Fig. 9B4). Similar to forelimb-related slow-conducting PTNs, the activity of the hindlimb-related slow-conducting PTN group was more modulated than that of the fast-conducting PTN group (Fig. 11, B2 vs. A2); however, they had their population peak during the stance rather than the swing phase (compare Fig. 10D2 and Fig. 11B2). Neurons with receptive fields constrained to a single hindlimb joint (only hip, knee, or ankle and paw) all had a preference to discharge during the stance phase of the stride (Fig. 11, C–E), producing as a group 19.4 ± 0.8 spikes/s during this period vs. 13.8 ± 0.4 spikes/s during the swing phase (U-test, P < 0.05), with a peak of the activity at the end of phase 7 of the walking cycle (Fig. 3, Fig. 4).

Fig. 11.

Population characteristics of hindlimb-related neurons during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A: PTNs with fast axonal conduction velocities. B: PTNs with slow axonal conduction velocities. C: neurons responsive to passive movements in the hip joint. D: neurons responsive to passive movement of the knee joint. E: neurons responsive to passive movement in the ankle joint or palpation of muscles and skin on the paw. Other designations are as in Fig. 9.

Effect of Narrow Walking on Activity of Neurons

Forelimb-related neurons.

The mean activity of the forelimb-related population during walking along the narrow path was slightly higher than during unconstrained walking (17.9 ± 1.1 vs. 15.5 ± 1.0 spikes/s; Student's unpaired t-test, P < 0.05). This was because the mean discharge rate of 40% (45/114) of neurons was higher by 135 ± 22%, while only 23% (26/114) of neurons decreased their rate by 37 ± 3% (paired t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 12A). Neurons active during the swing phase tended to have a higher activity more frequently (P = 0.07), thus the activity of the entire population rose during the midswing from ∼25 to ∼35 spikes/s, while the discharge rate during the stance phase did not significantly change (Fig. 9, C2 and C4 vs. A2 and A4). Neurons with one PEF per stride were the chief contributors to this population activity increase, as the discharge of the two-PEF group was largely similar between the walking tasks (Fig. 10B). The group of fast-conducting PTNs (1- and 2-PEF PTNs considered together) substantially increased activity during the midswing, going from 23 ± 0.4 to 33 ± 1.4 spikes/s (paired t-test, P < 0.05) while keeping the activity during the stance phase largely unchanged. As a result, the population activity of fast-conducting PTNs became pronouncedly modulated during walking along the narrow path (Fig. 10C4). The group activity of slow-conducting PTNs increased their modulation by increasing the activity during the swing phase from 25.3 ± 0.6 to 30.2 ± 1.4 spikes/s (P < 0.05; Fig. 10D4).

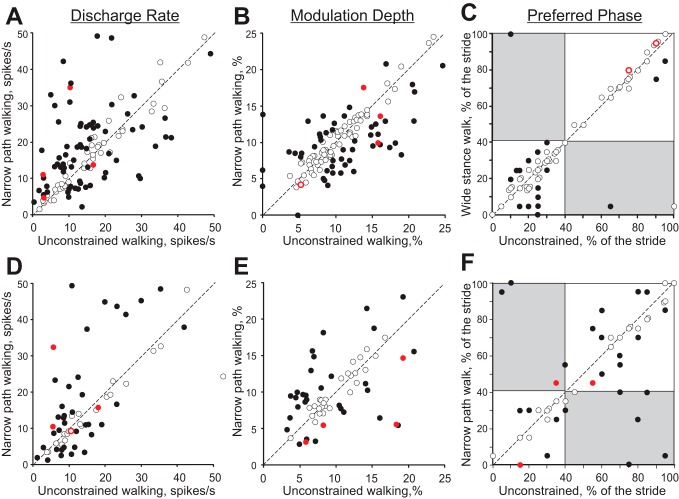

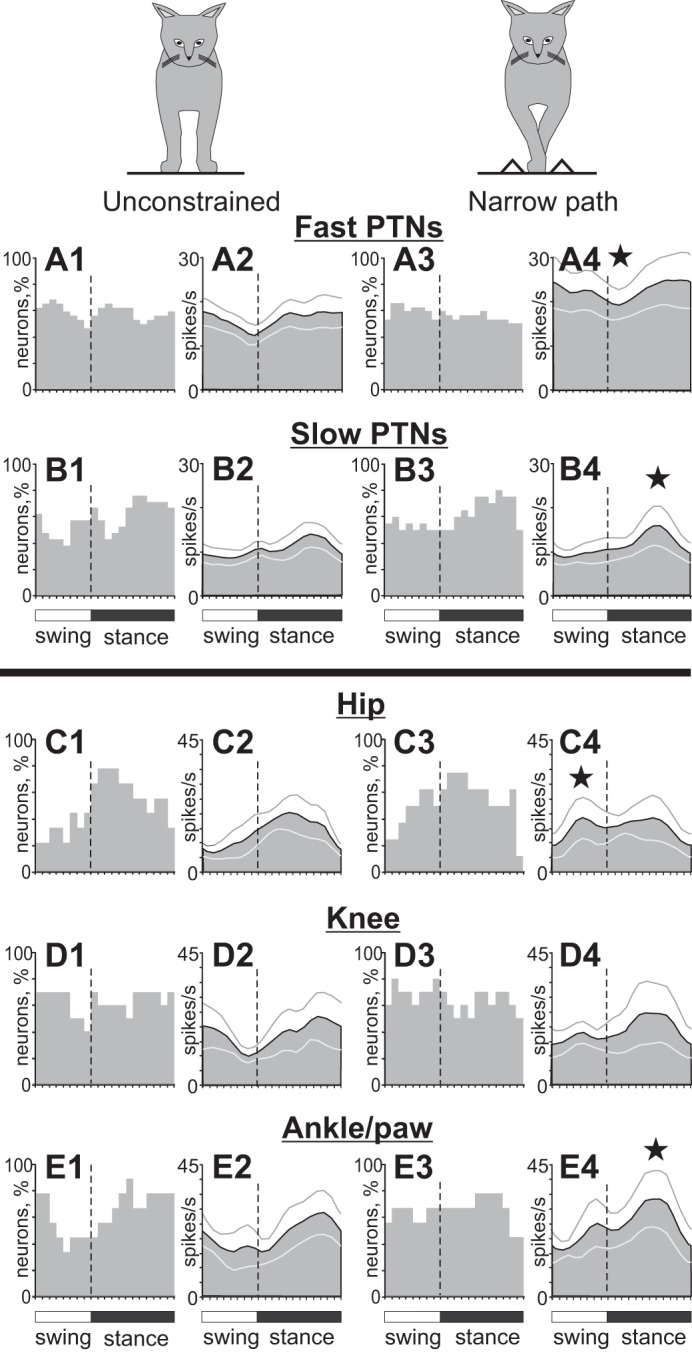

Fig. 12.

Comparison of activity characteristics in individual neurons from forelimb representation (A–C) and hindlimb representation (D–F) during unconstrained and narrow-path walking. A and D: mean discharge frequency averaged over the stride. B and E: depth of frequency modulation, dM. C and F: preferred phase of the activity for neurons with a single PEF during both locomotion tasks. A–F: x- and y-axes show the values observed during unconstrained and narrow-path walking, respectively. Neurons whose characteristics were statistically different during locomotion in the 2 conditions (see methods) are shown with filled circles; the others are shown with open circles. Red color indicates neurons that had cutaneous receptive fields, which during locomotion could have come into contact with dividers forming the walkway.

Neurons with receptive fields related to different joints responded differently to stepping restriction in the frontal plane. The shoulder-related group became more active during the swing phase at 31.2 ± 1.4 spikes/s, up from 23.8 ± 1.0 spikes/s during unconstrained walking (P < 0.05; Fig. 10E4). The wrist/paw-related cell group behaved similarly (P < 0.05), while additionally reducing activity during the midstance (P < 0.05; Fig. 10G4). In contrast, the activity of the elbow-related group increased during the stance phase (P < 0.05; Fig. 10F4).

Across the entire forelimb-related population, the activity of 87% (99/114) of individual neurons was different between narrow-path and unconstrained walking. In addition to differences in the discharge rates described above, the depth of frequency modulation was different in 46% (52/112) of stride-related neurons. During walking along the narrow path, it was lower in 32 neurons by 33 ± 2% and higher in 20 cells by 67 ± 16% (P = 0.055, Z-test; Fig. 12B). The duration of the PEF was different in 20% (22/112) of neurons: during walking along the narrow path, it was longer in 15 neurons by 25–45% of the cycle and shorter in 7 cells. In addition, half (16/29) of cells with two PEFs during unconstrained walking discharged only one PEF during walking along the narrow path. This typically occurred by an increase of the activity in between the former two PEFs (“filling in” one of the gaps between them), thus making one long PEF instead of two shorter ones (Fig. 2, B–F). On the other hand, only 11 of 80 neurons with one PEF per cycle during the unconstrained condition discharged two PEFs during narrow walking, which was a smaller proportion of cells compared with those that switched the other way around (P < 0.05). In the population of neurons that discharged one PEF during both walking tasks, 25% (17/69) of cells changed the preferred activity phase and discharged either later or earlier in the cycle, but nearly always only by 10–15% of the stride cycle (Fig. 12C). Wrist/paw-related neurons showed fewer changes to their activity parameters compared with either shoulder- or elbow-related cells (Z-test, P < 0.05). Among the latter, elbow-related neurons were most prone to modify the duration of the PEF, typically by increasing it during walking along the narrow path (Z-test, P < 0.05). Overall, the majority of neurons (63%, 72/114) had only one or two parameters of their activity different between the two walking conditions, while the activity of some cells (24%, 27/114) differed in three or four parameters.

Hindlimb-related neurons.

The mean activity of the hindlimb-related population during walking along the narrow path was similar to that during unconstrained walking (17.1 ± 1.8 vs. 14.2 ± 1.2 spikes/s, Student's paired t-test, P = 0.1; Fig. 9, B and D). The activity of the fast-conducting PTN group, however, rose across the entire step cycle by 44% from ∼16 to ∼23 spikes/s on average (P < 0.05; Fig. 11A4) but remained not modulated in respect to the cycle, as the PEFs of individual neurons stayed evenly distributed over it (Fig. 11A3). The activity of the slow-conducting PTN group was approximately half as low at 11.3 ± 2.1 spikes/s (P < 0.05) but was notably modulated in the stepping rhythm with an even higher peak during the stance phase compared with unconstrained walking (P < 0.05; Fig. 11, B4 vs. B2).

Neurons with receptive fields related to different joints responded differently to stepping restriction in the frontal plane. Similarly to shoulder-related cells, the hip-related neuronal group increased its activity during the swing phase of the stride (P < 0.05; Fig. 11C4), while the ankle/paw group, in opposition to the behavior of wrist/paw-related cells, augmented it during the stance phase (P = 0.05; Fig. 11E4). There was no clear change in the activity of the knee-related neuronal group (Fig. 11D4).

Across the entire hindlimb-related population, the activity of 90% (54/60) of individual neurons was different between narrow-path and unconstrained walking. The mean discharge rate was different in 55% (39/60) of neurons: it was higher in 38% cells by 113 ± 24% and lower in 27% by 42 ± 5% (Student's paired t-test, P < 0.05; Fig. 12D). Unlike the forelimb-related group, however, where fast- and slow-conducting PTN changed their activities similarly, slow-conducting hindlimb-related PTNs changed it more often than fast-conducting PTNs (Z-test, P < 0.05). The depth of frequency modulation was different in 52% (31/60) of stride-related neurons. Unlike the forelimb-related group, where neurons had a tendency to decrease the depth of modulation during narrow-path walking compared with the unconstrained condition, in the hindlimb-related group there were approximately similar numbers of neurons increasing and decreasing the depth of modulation: higher in 19 cells by 78 ± 9% and lower in 12 neurons by 37 ± 5% during narrow walking (Fig. 12E). The duration of the PEF was different in 27% (16/60) of neurons: during walking along the narrow path, it was shorter in 8 and longer in 8 cells by 25–50% of the cycle. In the population of neurons that discharged one PEF during both walking tasks, 29% (14/48) of neurons changed the preferred activity phase and discharged either later or earlier in the cycle (Fig. 12F).

DISCUSSION

The goal of this study was to examine mechanics and muscle and motor cortex activity during walking along a narrow pathway. By reducing the width of walking path to 5 cm, we imposed accuracy demands on paw placement in the medio-lateral direction and stability demands in the frontal plane. We found, however, that during walking along the narrow path cats were statically stable in the frontal plane despite the smaller base of support area during three-legged support phases, and that narrow-path and unconstrained walking had generally similar frontal and sagittal plane mechanics. The few differences included the slightly longer stride duration, lower vertical position and greater incline toward the ground of the head-neck segment, smaller lateral peak forces exerted by the hindlimbs, and greater fore- and hindpaw elevations during swing of narrow-path walking. The activity of 87–90% of neurons in the motor cortex, however, was substantially different during narrow-path walking compared with the unconstrained condition: the mean discharge rate was often higher, the depth of stride-related activity modulation was lower, and/or neurons were active for longer periods of the stride.

Experimental Design: Advantages and Limitations

Before discussing the obtained results and their significance, we should first explain the features of our experimental design and its advantages and limitations. We conducted a detailed investigation of the full-body mechanics and motor cortex and EMG activity in freely behaving cats that performed two highly trained locomotor tasks—unrestrained and narrow-path walking. To enhance and simplify experimental recordings and analysis, we studied the locomotor mechanics and the activity of motor cortex in different subjects (Table 1). This approach permitted a thorough analysis of fore- and hindlimb mechanics in the frontal and sagittal planes including static and dynamic stability, as well as an extensive analysis of activities of motor cortical neurons that included, for both the fore- and hindlimb cortical representations, a comparative evaluation of the activities of fast- and slow-conducting PTNs and neurons with receptive fields located on different segments of the limb. To our knowledge there have been only a handful of other similar multifaceted investigations of natural behaviors in mammals.