Abstract

The interpretation of visual information relies on precise maps of retinal representation in the brain coupled with local circuitry that encodes specific features of the visual scenery. In nonmammalian vertebrates, the main target of ganglion cell projections is the optic tectum. Although the topography of retinotectal projections has been documented for several species, the spatiotemporal patterns of activity and how these depend on background adaptation have not been explored. In this study, we used a combination of electrical and optical recordings to reveal a retinotectal map of ganglion cell projections to the optic tectum of rainbow trout and characterized the spatial and chromatic distribution of ganglion cell fibers coding for increments (ON) and decrements (OFF) of light. Recordings of optic nerve activity under various adapting light backgrounds, which isolated the input of different cone mechanisms, yielded dynamic patterns of ON and OFF input characterized by segregation of these two fiber types. Chromatic adaptation decreased the sensitivity and response latency of affected cone mechanisms, revealing their variable contributions to the ON and OFF responses. Our experiments further demonstrated restricted input from a UV cone mechanism to the anterolateral optic tectum, in accordance with the limited presence of UV cones in the dorsotemporal retina of juvenile rainbow trout. Together, our findings show that retinal inputs to the optic tectum of this species are not homogeneous, exhibit highly dynamic activity patterns, and are likely determined by a combination of biased projections and specific retinal cell distributions and their activity states.

Keywords: cone mechanism, fish retina, retinotectal projections, ultraviolet cone, voltage-sensitive dye

the determination of how retinal output is organized and processed in the brain is key to understanding how visual systems encode information. In nonmammalian vertebrates, the main target of retinal ganglion cell axons (or optic nerve fibers) is the optic tectum, the primary brain center responsible for visually guided behavior (Nevin et al. 2010). Early investigations into the spatial organization of optic nerve afferents in fish demonstrated precise retinotectal projections (Vanegas 1984). Optic nerve fibers from the dorsal, ventral, nasal, and temporal quadrants of the retina mapped, respectively, onto lateral, medial, posterior, and anterior regions of the optic tectum (Horder and Martin 1982; Jacobson and Gaze 1964; Schwassmann 1968; Schwassmann and Kruger 1965). Furthermore, the majority of projections targeted two specific lamina: the stratum opticum and the stratum fibrosum et griseum superficiale (Luckenbills-Edds and Sharma 1977; Vanegas et al. 1977).

Electrophysiological studies also revealed three to five optic nerve fiber types, based on conduction velocity, and a multitude of postsynaptic (tectal) potentials, the largest and fastest of which correlated with afferent input from the optic nerve fibers (Northmore and Oh 1998; O'Benar 1976; Schmidt 1979; Vanegas et al. 1974). In several fish species, including the rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), optic nerve fiber responses coding for increments (ON) and decrements (OFF) of light were found to consist of two major depolarization events, followed by another one of smaller amplitude (Beaudet 1997; Beaudet et al. 1993; DeMarco and Powers 1991). The two major depolarization events varied in relative amplitude with stimulus intensity, and the latency of the first one (i.e., the time-to-peak amplitude from stimulus onset/offset) approached one-half that of the second one. The third, delayed depolarization event was found to carry efferent information from the optic tectum back to the retina (Vanegas et al. 1974). Evoked potentials recorded from the surface of the optic tectum further revealed two major hyperpolarization events that correlated in time with the two main depolarization peaks from the optic nerve response (McDonald et al. 2004; Vanegas 1984; Vanegas et al. 1974).

During the past decade, an increasing number of optical imaging studies have revealed a large number of ganglion cell types (∼20 in mammals; >50 in fish) and unprecedented target specificity within individual brain laminae (Dhande and Huberman 2014; Robles et al. 2014; Roska and Meister 2014). In mammals and fish, the projections of retinal ganglion cell types are spatially segregated within their brain targets (Hong et al. 2011; Martin and Lee 2014; Robles et al. 2013, 2014). In marmoset monkeys, for instance, blue-yellow opponent cells are primarily found in the koniocellular layers of the dorsolateral geniculate nucleus, whereas red-green opponent cells are found preferentially in the parvocellular layers (Martin and Lee 2014). In zebrafish, orientation- and direction-selective ganglion cells show biases for different laminae of the optic tectum as well as for topographic regions (Nikolau et al. 2012). Furthermore, ON and OFF fibers preferentially target superficial and deep sublaminae of the stratum fibrosum et griseum superficiale, respectively, whereas ON-OFF fibers predominate at intermediate depths (Robles et al. 2013).

Information on the spatial distribution of chromatic inputs to the optic tectum of nonmammalian vertebrates is lacking, and the changes in activity elicited by chromatic adaptation of retinal projections have been rarely explored. In particular, changes in latency of the optic nerve response as a function of chromatic adaptation have not been documented. Yet the latency of responses is a crucial parameter to understand encoding of sensory stimuli or features thereof, such as color saturation in the visual cortex (Conway 2014) and odor type in the mammalian olfactory bulb (Schaefer and Margrie 2007). Here, we explored the spatiotemporal properties of retinal ganglion cell projections to the optic tectum of rainbow trout across the UV and (human) visible spectrum with a focus on the effects of chromatic adaptation. Our findings suggest spatial segregation of ON and OFF inputs to the optic tectum with response characteristics that vary dynamically as a function of stimulus and background properties.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Juvenile rainbow trout were obtained from the Sandwich Fish Hatchery (Sandwich, MA) or the Fraser Valley Trout Hatchery (Abbotsford, BC, Canada) and kept in tanks with aerated, circulating water under a 12-h light:12-h dark light cycle. All animal use was approved by the Animal Care Committees at Simon Fraser University and the University of Victoria and the veterinarian at the Marine Biological Laboratory. The protocols conformed to the guidelines set by the Canadian Council for Animal Care and the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Mean fish weight and total length ± SD for the experiments were 14.5 ± 3.1 g and 13.2 ± 0.6 cm (n = 54). Rainbow trout of this size are at the parr stage (Novales Flamarique 2005) and are tetrachromatic, possessing UV, short (S; blue), middle (M; green), and long (L; red) wavelength (λ) cone mechanisms (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997). A cone mechanism, for the purpose of this work, is defined as the cone photoreceptor and associated retinal neurons that contribute to the optic nerve response. The λ range of maximum sensitivity for each cone mechanism in parr rainbow trout is 380–390 nm (UV), 420–430 nm (S), 520–540 nm (M), and 620–630 nm (L) (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique 2012; Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997). This range is primarily determined by the type of opsin (SWS1, SWS2, RH2, or LWS) and chromophore (vitamin A1 or A2 based), which together, constitute the visual pigment in each cone class (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007; Novales Flamarique 2005).

Optic tectum surgery.

Fish were anesthetized by bath immersion in buffered MS-222 solution (0.2 g/l, pH 7.4). Once the upright reflex had been lost, the fish was paralyzed by intramuscular injection of Flaxedil (10 μg/g fish), placed into a holding apparatus, and irrigated through the mouth with MS-222 solution (0.02 g/l). A gauze was placed along the body and maintained wet throughout the experiment. The gauze was opened at two places to expose the iris and the area of the head above the contralateral optic tectum. With the use of a high-speed micro drill, the portion of the skull and connective tissue above the optic tectum was removed and excess fluid absorbed by suction. Anesthetic (Xylocaine Jelly, 2%) was applied around the surgical area, and irrigation was then changed to holding water. During the surgical procedure, regularity and strength of tectal blood flow were monitored as an indicator of fish physical condition.

Visual stimuli and adapting backgrounds.

Stimuli and adapting backgrounds were generated with two separate optical channels whose components and configuration varied depending on the experiment conducted (Fig. 1). The stimulus channel consisted of a 150-W Xenon light source coupled to a monochromator (Photon Technology International, Edison, NJ), whose output traversed a Uniblitz shutter (Vincent Associates, Rochester, NY) and neutral density wheel (Delta Photonics, Ottawa, ON, Canada) before entering an optical fiber that delivered the light to the eye (Fig. 1, A and B). The shutter and neutral density wheel were under computer control. We used three types of light guides for the various experiments.

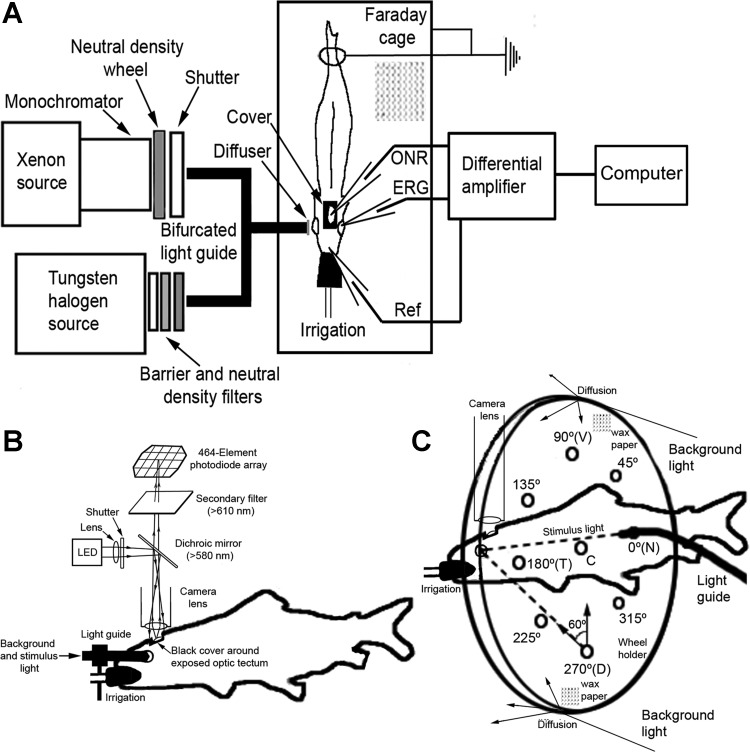

Fig. 1.

Diagrams showing main features of setup for electrical and optical recordings. A: schematic of the 2 optical channels: stimulus (Xenon source) and background (tungsten/halogen source), converging onto the common end of a bifurcated light guide with a diffuser at its extremity. Light from the guide illuminates the fish's eye, and electrical or optical recordings of retinal activity are acquired using electrodes or a voltage-sensitive dye (VSD) and photodiode array system. Differential recordings of electrical activity between the optic nerve [optic nerve response (ONR)] or the retina [electroretinogram (ERG)] and a reference (Ref) electrode are amplified and analyzed by computer. B: for optical recordings, a photodiode array system was positioned above the exposed optic tectum to acquire fluorescence signals. LED, light-emitting diode. C: modification of the stimulus and background illumination using a diffusive acrylic wheel equipped with holes for light-guide insertion. Except for the center (C) hole, which approached alignment with the normal to the center of the iris, the other holes were directed at 60° to the center of the iris. The holes were placed every 45° around the trigonometric circle, with 0° illuminating the nasal (N), 90° the ventral (V), 180° the temporal (T), and 270° the dorsal (D) retina.

In one type of optical recording experiment, we used a 1-mm entrance diameter liquid light guide (Edmund Optics, Barrington, NJ) to project small spots of light from various parts of the visual field onto specific areas of the retina (Fig. 1C). To do this, the exit end of the light guide was inserted into one of multiple angled holes in a transparent acrylic wheel holder (15 cm in diameter), placed 5 cm in front of the fish's eye. The wheel holder was positioned such that the center hole was aligned with the center of the eye, and holes every 45° of angle along the trigonometric circle sustained a 60° angle of incidence with respect to the normal to the center of the eye. Because the fish holder was tilted at a 5° angle to accommodate for the slight slope of the optic tectum from medial to lateral (and hence, to be able to image the entire structure on approximately the same plane), the alignment of the central hole on the wheel was not axial with respect to the retina but slightly tilted toward the ventrotemporal quadrant. This tilt is represented in the sketches of retinal illumination in results. The back of the acrylic wheel was lined with wax paper, creating a large, diffusive screen in front of the fish. We used a tungsten/halogen source (Photon Technology International) and neutral density and barrier filters (Andover, Rochester, NY) to project a circle of light of specific intensity and spectral content that filled the back of the wheel holder constituting the adapting background. Thus the fish's eye was stimulated with a small diameter (1 mm) light flash (500 ms in duration), superimposed on a large, diffuse background. Based on the mean lens diameter of the fish studied (2.1 mm), the 1-mm light spot would project a 50-μm image on the retina. This would cover approximately one cone mosaic unit, i.e., five single cones and four double cones (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007), or two to three ganglion cell soma, each with a dendritic field area of ∼0.09 mm2 (Picones et al. 2003). The 5° tilt of the fish holder would have no appreciable effect on image size, as the rainbow trout lens is well corrected for longitudinal aberration on and off axis (Jagger and Sands 1996).

In another type of experiment, a larger diameter (4 mm) bifurcated liquid light guide with a diffuser at its output end was used to achieve broad stimulation of the retina (Fig. 1B), although a majority of the light remained directed along the optical axis of the fiber. The output end of the fiber was placed 1 cm in front of the fish's eye, and its angle of incidence could be changed by rotating a ball-joint holder. One input end of the bifurfacted light guide received light from the stimulus channel, whereas the other received background light from a tungsten/halogen source whose output traversed associated barrier and neutral density filters (Fig. 1A). Both inputs were therefore superimposed and, as such, illuminated the same area of the retina. The fish was adapted to a specific light background and stimulated with a flash of light superimposed on the background. The same optical configuration was used in the case of electrical recordings, where the response was measured using electrodes instead of optically. The spectral characteristics of the backgrounds used in this study have been published previously (Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997, 1998) and correspond to light levels that are >10 times greater than those at which rod photoreceptors start to become operative (Beaudet 1997). Thus all of the responses measured were driven by cone photoreceptors.

Optical recordings.

A voltage-sensitive dye (RH-414, 0.2 g/l in fish Ringer's solution) was applied onto the surface of the optic tectum and allowed to stain it for 1 h during which the fish became adapted to a particular light background. Cross-sections of several fish brains examined postmortem showed that the dye penetrated the entire depth of the optic tectum evenly. Excess dye that had not penetrated the optic tectum after the 1-h incubation period was washed away with Ringer's solution. At this time, the fish was ready for optical recordings.

Optical recordings involved the acquisition of fluorescent signals from areas in the optic tectum with active ganglion cell fiber input following the light stimulus. This was achieved by imaging the optic tectum through a 0.95-f/25-mm field lens connected to a 464-diode array detector (WuTech Instruments, Georgetown, Washington, DC). The output from a high-power, 530-nm light-emitting diode (LED; Thorlabs, Newton, NJ) was reflected onto the optic tectum by a 590-nm long-pass dichroic mirror. Light fluorescence from the optic tectum was acquired by the photodiode array, with each photodiode receiving light from an ∼150 × 150-μm2 region. The photocurrents from each diode were amplified separately, band-pass filtered by the amplifiers (0.07–500 Hz), and digitized at 1 kHz using NeuroPlex software (RedShirt Imaging, Decatur, GA). During experiments, control of the shutters and the LED source for synchronous stimulation of the eye and optic tectum was achieved with a Master-8 (A.M.P.I., Jerusalem, Israel) under the control of NeuroPlex.

To avoid LED light that illuminated the optic tectum interfering with the stimulus and adapting background, a black cover with small overhangs was built that fitted around the exposed optic tectum. This cover was positioned before lowering the diode array for focusing the optic tectum. Focusing of the optic tectum was achieved using a high-resolution charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (Dage-MTI, Michigan City, IN). Images of fluorescence from the optic tectum through a calibration pattern were recorded with the CCD camera and the diode array to allow alignment of response patterns between fish.

Optical imaging was used to evaluate the spatial pattern of optic nerve fiber inputs to the optic tectum as a function of location of retinal illumination and chromatic adaptation. As such, we used stimuli of suprathreshold intensity known to elicit responses from the various cone mechanisms under the light backgrounds used (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997). For a given stimulus of specific λ and intensity, the mean response to three, 500-ms flashes (presented in a series with a 30-s interstimulus interval) was acquired using NeuroPlex. Responses were obtained to full-spectrum light and to multiple λs in the spectrum 360–660 nm, with emphasis on λs (380, 430, 540, and 630 nm) within the maximum-sensitivity range of the four cone mechanisms present in juvenile rainbow trout (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997). Responses were further filtered (2 Hz high-pass Tau filter, 30 Hz low-pass Binomial filter) and measurements of amplitude and latency (see Fig. 2G) for the ON and OFF components of each response obtained for diode elements of interest, including those exhibiting the maximal response. Contours encompassing diodes with amplitude equal to or surpassing one-half of the maximal response were also generated for topographical comparisons.

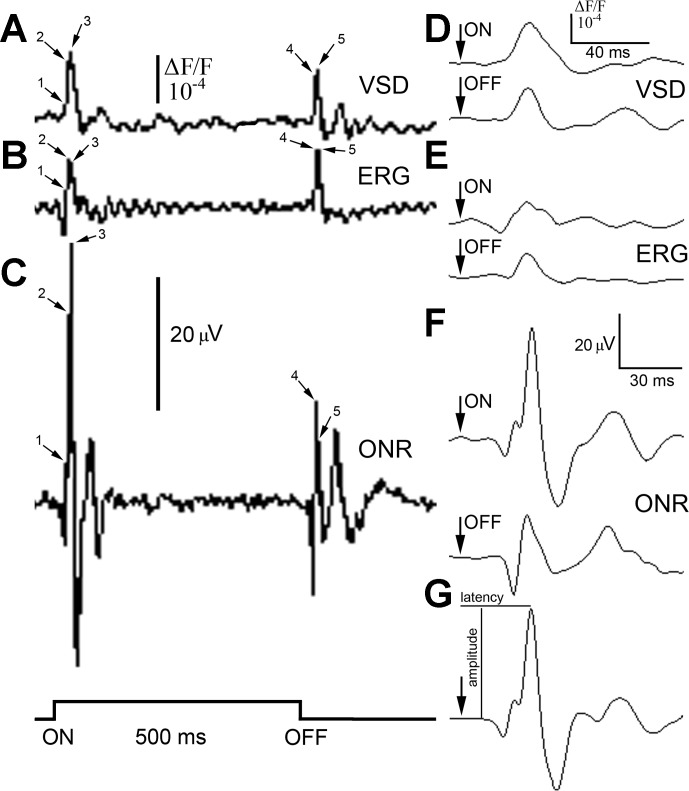

Fig. 2.

Responses (mean of n = 3) to the onset (ON) and termination (OFF) of a 500-ms, 380-nm light stimulus of suprathreshold intensity (2.5 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1), recorded using electrode or optical means from the rainbow trout visual system. A–C: recordings, from the same fish, of optical activity at the level of the optic tectum using the RH-414 VSD (A), an ERG (B), and the ONR recorded with an electrode inserted through the optic tectum into the optic nerve (C). The step trace at the bottom left of the figure shows the stimulus time course. Before recordings, the fish was adapted to a dim, full-spectrum light background [4.6 × 1012 photons cm−2s−1; wavelength (λ): 380–740 nm]. Time points 1–5 indicate several components of the ON (1–3) and OFF (4 and 5) responses that occurred in all traces. D–F: at 10-fold temporal resolution, the ON and OFF responses showed a single, main peak associated with the first upward deflection (consisting of components 2 and 3 in A–C), as illustrated for the VSD (D), ERG (E), and ONR (F) traces. The arrow on each trace indicates the onset or termination of the light stimulus. The main ON response peak occurred at 35 ms (VSD), 33 ms (ERG), and 34 ms (ONR) following the onset of the light stimulus. The main OFF response peak occurred at 34 ms (VSD) and 33 ms (ERG and ONR) following termination of the stimulus. G: another ON response, obtained using the ONR technique, to a 380-nm light stimulus, illustrating the measures of amplitude and latency. The scale bars with amplitude in microvolts apply to corresponding ERG and ONR traces (B, C, and E–G), and those denoting increment fluorescence above background (ΔF/F) correspond to the VSD traces (A and D).

Electrical recordings of optic nerve activity.

These experiments were undertaken to reveal the cone mechanisms (and their kinetic properties) that contribute to the ON and OFF responses in rainbow trout. Our data were used to validate general results and conclusions obtained by Beaudet (1997), who allowed the incorporation of his findings into the present study. The experiments focused on the temporal retina and used the same large fiber-diffuser combination used in the optical recordings described earlier. The optic nerve recording procedure used in this study has been described in detail previously (Beaudet et al. 1993) and will only be summarized here. Following surgical exposure of the optic tectum, a Teflon-coated silver wire (0.45 mm diameter; A-M Systems, Sequim, WA) with an exposed, chlorodized tip was inserted through the optic tectum into the optic nerve. Another reference wire was inserted into the contralateral nare. Following adaptation of the fish for 1 h to a background light, the fish's eye was stimulated with a given λ in incremental steps of intensity. At each intensity, three responses to a 500-ms light flash (with 30 s interstimulus interval) were differentially amplified 100,000 times (DAM 60; World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) with band pass 1 Hz–1 Khz and the mean acquired using NeuroPlex. The amplitude and latency of the ON and OFF responses were obtained from the first major positive deflection after the onset and offset of the stimulus, respectively (Fig. 2G). For intensities at or near threshold, the first deflection peak had the highest amplitude of all of the response peaks.

At each λ, response amplitude vs. log (stimulus-intensity) curves were generated for the ON and OFF components of the response and fitted with third-order polynomials (Beaudet et al. 1993). Sensitivity was determined as the reciprocal of the intensity that elicited a threshold response of 30 μV. This level of response was chosen because it resided in the lower range of the linear part of the fit for all λs tested. Under chromatic adaptation, the response at low intensities is likely caused by the isolated cone mechanism alone, such that peaks in sensitivity represent the activity of discrete cone mechanisms (Beaudet et al. 1993).

At each λ, latency response as a function of stimulus intensity was fitted with the equation (Donner et al. 1995)

| (1) |

where L is latency, a is a constant, b is the slope of the function, and I is the stimulus intensity. Amplitude and latency functions as a function of stimulus intensity were generated for up to 16 λs, ranging the spectrum from 360 to 660 nm. The λs were presented in a sequence that minimized selective adaptation of any particular cone mechanism by the stimulus.

For each adapting background used, a mean spectral sensitivity curve was generated for both ON and OFF responses by averaging normalized curves from multiple fish. Slope b values under a given background were normalized to the absolute highest value, and means ± SD were computed for four test λs (380, 420, 520, and 620 nm) and plotted against λ. This analysis was restricted to the ON response, as the variations in OFF response did not always follow a consistent pattern. In the remainder of the manuscript, higher slope values correspond to higher rates of latency decrease with stimulus intensity. Normalized slopes were compared within each adapting background using Scheffé's multiple comparison test with α = 0.05.

Response latency at threshold across the spectrum was determined for each fish using the latency-intensity curve by choosing the latency that corresponded to the threshold intensity determined from the corresponding amplitude-intensity function. Response latency values across the spectrum were normalized and means ± SD calculated for the various adapting backgrounds. In addition, latency at each λ was determined for a stimulus of fixed intensity for the ON response. The value of the fixed intensity was selected as the minimal intensity that triggered a response at all test λs. Differences in latency across the spectrum were evaluated using Scheffé's multiple comparison test with α = 0.05.

Electroretinograms.

In a few fish, an electroretinogram (ERG) was recorded simultaneously with the optic nerve response (Fig. 1A). The recording procedure was modified from a published study (Makhankov et al. 2004) and involved insertion of a pulled glass micropipette with an ∼20-μm tip loaded with Ringer's solution into the dorsal part of the eye. Postmortem analysis of retinal sections showed that the tip of the pipette resided in the ganglion cell fiber layer or near it in the aqueous humor. The micropipette contained a chlorodized silver wire attached to an Ag/AgCl holder (A-M Systems). The differential signal, with respect to the reference wire in the nare, was amplified and processed in the same manner as per the electrical signal recorded directly from the optic nerve. ERGs were compared with parallel recordings using the other two techniques to determine the source of measured signals.

RESULTS

Characteristics of the optic nerve response in juvenile rainbow trout.

We used three recording methods to assess the waveform and temporal characteristics of ON and OFF optic nerve responses in rainbow trout: optical recordings using the voltage-sensitive dye RH-414 impregnated throughout the optic tectum (Fig. 2A), the ERG (Fig. 2B), and electrical recordings from the optic nerve (Fig. 2C). All of the methods resulted in responses that were multiphasic, comprising a major upward deflection made up of multiple components that traveled at different velocities (examples of such components are indicated on the traces in Fig. 2, A–C). These components were present in all traces and occurred quasi-simultaneously; at higher temporal resolution, they merged into one dominant peak (Fig. 2, D–G). Since both types of electrical recordings (ERG and optic nerve response) measured potentials from presynaptic tectal elements, the similarity in responses between methods indicated that our optical recordings also measured optic nerve activity. Nonetheless, optical responses incorporated activity from postsynaptic elements as well, although in our analyses, which examined the first deflection (shortest latency) response, such input was likely restricted to cells in the vicinity and above the ganglion cells' terminals (Grinvald et al. 1984). Non-ERG recordings further revealed a prominent, downward deflection, followed by an upward deflection of smaller amplitude than that of the main peak. This secondary-positive deflection had a latency that approached twice that of the main peak, and the relative amplitudes of these two major positive deflections varied with stimulus intensity and λ.

Distribution of retinal projections to the optic tectum of rainbow trout.

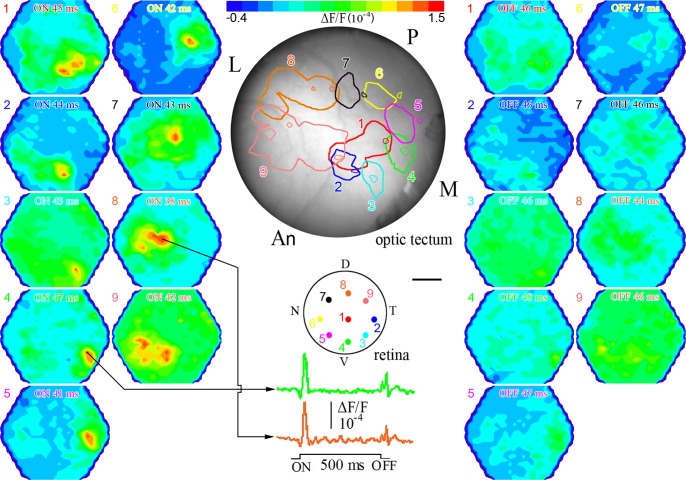

Stimulation with a small diameter optical fiber revealed a topographic map of ganglion cell projections to the contralateral optic tectum with nasal, temporal, ventral, and dorsal sectors of the retina projecting onto posterior, anterior, medial, and lateral parts of the optic tectum, respectively (Fig. 3). Adjacent regions of the retina mapped near each other, forming a precise, orderly representation of the retina in the optic tectum. The spatial extent of the signal above one-half maximum amplitude and the latency at maximum amplitude varied with retinal illumination, with the strongest OFF responses originating from ventrotemporal retinal locations (Fig. 3). This retinotectal map was reproducible between fish and revealed that latency to a full-spectrum suprathreshold light stimulus was shorter by ∼7 ms for the dorsal retina compared with the ventral retina, with intermediate latencies associated with the nasotemporal axis (i.e., the posterior-anterior axis of the optic tectum; Fig. 4).

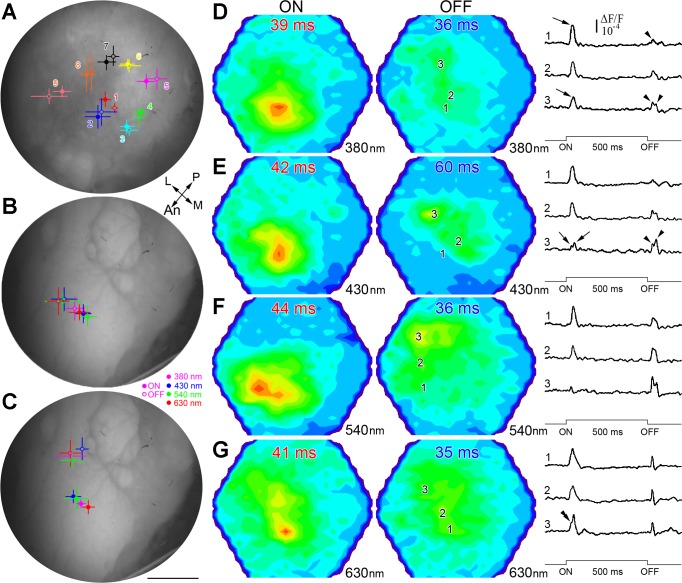

Fig. 3.

Map of retinal ganglion cell afferent input to the contralateral optic tectum derived by optical recordings with the RH-414 VSD. Shown are 2 sets of corresponding pseudocolor images illustrating ON (left) and OFF (right) responses to 9 locations of retinal stimulation. The stimulus was full-spectrum light (λ: 320–740 nm) of 500 ms duration and of suprathreshold intensity (2.8 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1). The adapting light background was the same as in Fig. 2. Labeled at the top of each pseudocolor image is the type of response (ON or OFF) and the latency at maximum amplitude of depolarization (see Fig. 2G for measures). At the top of the figure is a bar showing the color range of responses, from hyperpolarization (blue) to depolarization (red). The colored dots on the drawing of the retina illustrate the locations of retinal illumination and are numbered 1–9. Corresponding pseudocolor images are likewise numbered with the color matching that of the latency of the ON and OFF responses. Below the retina drawing, the trace from the diode with maximum ON response is shown for 2 locations of retinal illumination. Color-matched (and numbered) ganglion cell response contours, each comprising the area with ≥50% of the maximum ON response, are mapped onto the surface of the optic tectum (middle, top). Smaller contours within or near larger contours of same color delineate areas with ≥50% of the maximum OFF response. M, medial; P, posterior; L, lateral; An, anterior optic tectum. Scale bar, 0.32 mm (retina) and 0.42 mm (optic tectum). All other symbols are as in Fig. 2.

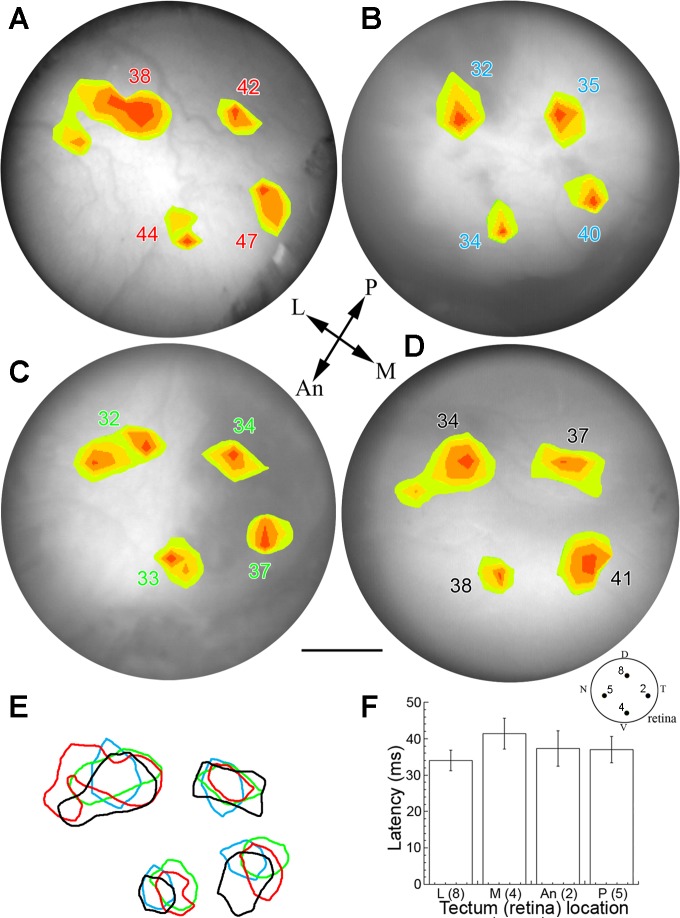

Fig. 4.

Consistency of retinal projections to the optic tectum of juvenile rainbow trout. A–D: pseudocolor response contours mapped onto the optic tectum for each of 4 juvenile rainbow trout. Each pseudocolor area encompasses responses with an amplitude ≥50% of the maximum ON response. The number associated with each contour is the latency of the response. The recording technique, light stimulus, and background adaptation were as in Fig. 3. The 4 locations of retinal stimulation correspond to the D, T, V, and N spots on the retina drawing in Fig. 3 (and reproduced at the bottom right of this figure); these light stimulations resulted in projections to the L, An, M, and P regions of the optic tectum, respectively (reference arrows for optic tectum orientation are shown in the middle of this figure). E: the retinotectal projections were spatiotemporally consistent between fish, as shown by the extensive overlap of corresponding depolarization areas (color-matched to corresponding latencies). F: differences in response latency as a function of illumination area (matching numbers on retinal drawing). The mean latency of the medial projection (ventral retina) is significantly longer than that of the lateral projection (dorsal retina; t-test, α = 0.05). The spatial comparison between fish was achieved by mapping coordinates of each response contour with respect to the medial line separating both tecta and to the posterior end of the optic tectum. Scale bar, 0.72 mm, applies to all panels.

Spatial segregation of ON and OFF ganglion cell projections.

For a given region of the retina, the location of maximal response at the level of the optic tectum differed between the ON and OFF responses for individual fish. However, when illuminating with the 1-mm fiber (Fig. 5A), the mean response was not statistically different between the ON and OFF responses for any location except for the center and only along the x dimension (t-test, α = 0.05). When averaged over all locations, the mean spatial difference was 125 ± 58 μm between corresponding responses. Under a dim, full-spectrum adapting background, when a diffuser was used to illuminate the entire retina (although with a preponderance of light aimed at the temporal retina), the maximal responses occurred in the anterior optic tectum (Fig. 5B). ON and OFF responses to various λs within the maximal-sensitivity range of the four cone mechanisms present in juvenile rainbow trout grouped in different locations of the optic tectum and were statistically different along the x dimension (Fig. 5B). The mean spatial difference between corresponding responses was 316 ± 118 μm. When the fish was exposed to a new background (λ > 430 nm) that preferentially adapted the M and L cone mechanisms, the locations of maximal OFF responses shifted toward the lateral optic tectum (dorsal retina; Fig. 5C), and the difference between corresponding responses became greater (and statistically significant along both the x and y dimensions), with a mean of 702 ± 115 μm. ON and OFF maximal responses were thus highly dynamic in their topographic location and dependent on adaptation background and stimulus λ.

Fig. 5.

Separation of maximal response location between ON and OFF fiber projections to the optic tectum of juvenile rainbow trout. A–C: mean location (n = 4) of ON (full circles) and OFF (rings) maximal responses to: full-spectrum stimulation on the retina (A) as per the conditions in Fig. 3 (numbers and colors of projections match corresponding ones on retinal drawing in Fig. 3), stimulation with various λ (B; 380, 430, 540, or 630 nm; see key at bottom right of panel) under the background conditions of Fig. 3 but using a larger stimulus light guide with a diffuser at its end (this permitted illumination of the entire retina, although a majority of the light was directed at the temporal retina), and same stimulus (C) as per B but following 1-h adaptation of the fish to a >430-nm background, which preferentially adapted the longer wavelength (middle and long) cone mechanisms. Bars around the means are the SDs of the (x, y) coordinates. In each case, means ± SD are mapped onto the surface of a representative optic tectum. Scale bar, 0.75 mm (A–C). D–G: representative pseudocolor image pairs (arranged horizontally) illustrating ON and OFF responses at their respective maxima to a 500-ms suprathreshold light stimulus under the >430-nm background. The characteristics of the light stimulus were λ = 380 nm (2.5 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1; D), λ = 430 nm (5.9 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1; E), λ = 540 nm (6.8 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1; F), and λ = 630 nm (4.7 × 1013 photons cm−2s−1; G). Associated with each image pair are response traces corresponding to locations 1–3 in the optic tectum (illustrated on the OFF pseudocolor images only). These traces are for diodes that recorded the maximal ON amplitude (1), maximal OFF amplitude (3), and representative in-between amplitudes (2). The shapes of the ON and OFF responses varied with λ, and the location of the ON and OFF maxima also differed for a given λ. Other presentation and abbreviations are as in Fig. 3.

Examples of typical response patterns and waveforms under the longer λ (λ > 430 nm) background are shown in Fig. 5, E–G. Overall, the OFF maxima were displaced laterally at the level of the optic tectum with respect to the ON maxima, which were mapped to the anterior tectum, and the responses were dependent on stimulus λ. With the exception of responses to 630 nm, which had a similar ON-to-OFF-amplitude ratio across the optic tectum, responses to other λs tested showed reverse gradients of ON and OFF dominance with location: ON responses dominated the anterior part of the optic tectum, whereas OFF responses were more prevalent in the lateral tectum (compare various traces). Where dominant over the OFF response, the ON response comprised one prominent peak (e.g., arrows on 380 nm traces; Fig. 5D), although large bandwidths at one-half maximum amplitude and inflexion points (double arrowhead on 630 nm trace 3; Fig. 5G) indicated multiple response components (see also Fig. 2). ON responses with two separate peaks were found in tectal areas dominated by the OFF response (e.g., trace 3 of 430 nm stimulation; Fig. 5E). With the exception of responses to 630 nm stimulation, characterized by single-peak profiles, the majority of OFF responses to other λs tested showed two peaks consisting of a fast component (similar to the one resulting from 630 nm stimulation) and a slower component, 20–30 ms, delayed with respect to the first one (arrowheads over traces; e.g., Fig. 5, D and E). The relative amplitudes of the two OFF peaks varied with λ (compare 430 with 540 nm traces; Fig. 5, E and F).

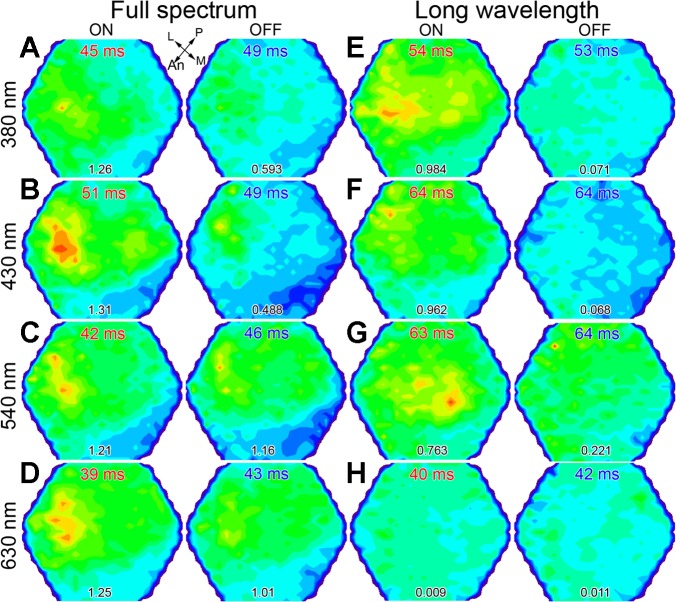

UV cone-mediated sensitivity is strongest in the dorsal retina of juvenile rainbow trout.

With the use of a diffuser in front of the fish's eye, stimulation directed at the dorsotemporal retina led to a broad response pattern over the optic tectum (Fig. 6). Under dim, full-spectrum adaptation, the maxima of responses were located in the anterolateral area of the optic tectum (corresponding to the dorsotemporal retina), regardless of stimulating λ (Fig. 6, A–D). Under a background that chromatically adapted the spectral sensitivity of the L cone mechanism (note that the maximum ON signal amplitude in Fig. 6H is 1/96th that in Fig. 6D and 76–100 times lower than corresponding amplitudes in Fig. 6, E–G) and isolated that of the UV cone mechanism (maximum ON amplitude ratios for Fig. 6, F–H, with respect to Fig. 6E, are 1:0.98:0.76:0.01), the 380-nm ON response was spatially enhanced and remained strongest in the anterolateral optic tectum, whereas the OFF response became heavily depressed (maximum OFF response in Fig. 6E is 8 times lower than the corresponding one in Fig. 6A). These trends were somewhat similar for 430 nm stimulation, although the maximum ON amplitude shifted to the lateroposterior optic tectum (Fig. 6F). In contrast, the maximum 540-nm ON response was located centromedially, and the OFF response, which dominated all OFF signaling under this background adaptation (OFF maximum response amplitude ratios, with respect to the 540-nm response, were 0.51:0.42:1:0.86 for Fig. 6, A–D, and 0.32:0.31:1:0.054 for Fig. 6, E–H), had its maximum shifted posteriorly (Fig. 6G). Thus besides restricted UV cone-mediated input to the anterolateral optic tectum, these experiments revealed that under adaptation to longer λs and for suprathreshold stimuli, the UV cone mechanism contributed primarily to the ON response, whereas the M mechanism dominated the OFF response.

Fig. 6.

UV cone-mediated sensitivity in the dorsotemporal retina of juvenile rainbow trout. A–H: pairs of pseudocolor images (arranged horizontally) showing maximal ON and OFF responses to different λs (380, 430, 540, or 630 nm) under the dim, full-spectrum light background of Fig. 5 (A–D) and under a >540-nm (long λ) background (E–H), which chromatically adapted the long λ cone mechanism (see minimum signal in H). The numbers at the bottom are the maximal response amplitude in 10−4 ΔF/F. The light guide used to generate the results in Fig. 5, B and C, here, was pointed toward the dorsotemporal retina. Both ON and OFF maxima were located in the anterolateral optic tectum (corresponding to the dorsotemporal retina) under the full-spectrum condition (A–D) and under the long λ background for 380 nm stimulation (E). Under the latter background, the maximal response to 540 nm light shifted toward the medial optic tectum (ventral retina; G). Other presentation of data and abbreviations are as in Fig. 3.

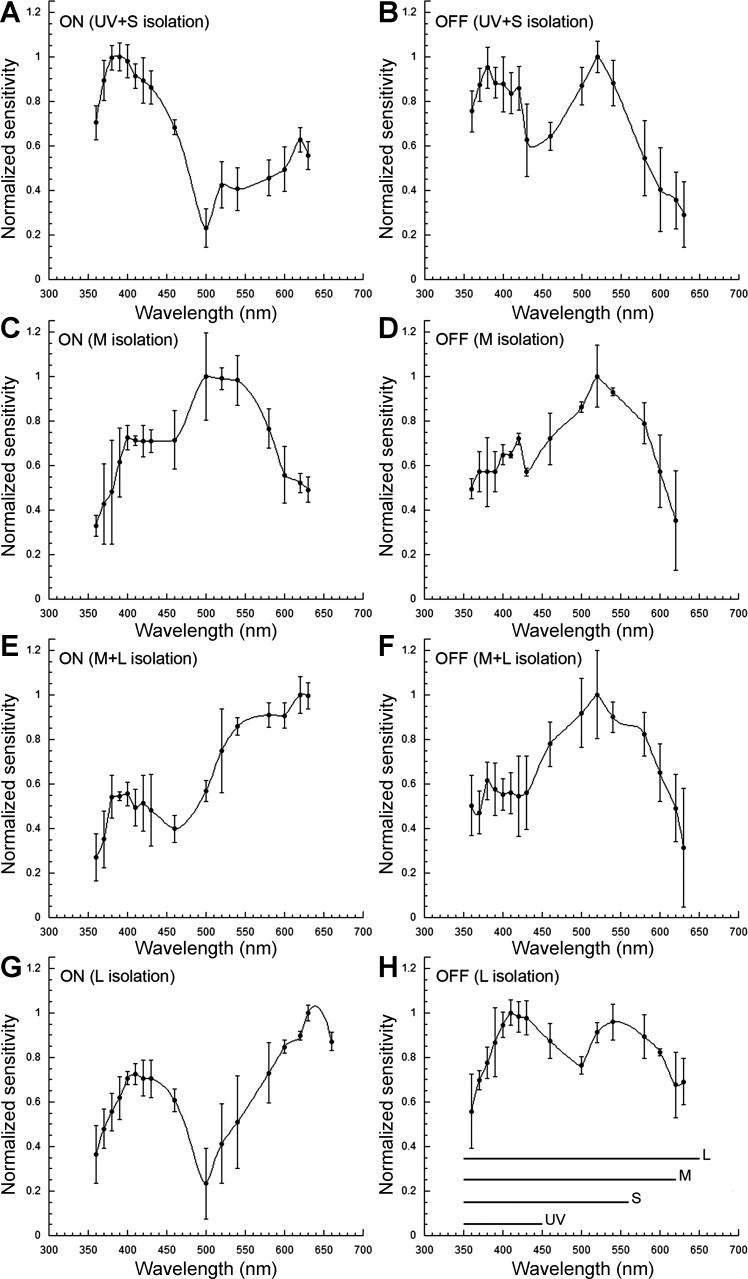

Different combinations of cone mechanisms contribute to the ON and OFF spectral sensitivity responses.

Spectral sensitivity of the temporal retina, obtained from optic nerve electrical recordings under light-adapting backgrounds that isolated the UV + S, M, M + L, or L cone mechanisms revealed inputs to the ON response from the four cone mechanisms: UV, S, M, and L (Fig. 7, A, C, E, and G). Under UV + S mechanism isolation, a predominant sensitivity peak at 390 nm (UV) was accompanied by secondary peaks at 420, 520, and 620 nm, indicative of S, M, and L input, respectively, to the ON response (Fig. 7A). Under M mechanism isolation (Fig. 7C), the ON response was characterized by a prominent peak, 520–540 nm, and increased sensitivity in the range of 400–430 nm. No contributions from the UV or L mechanisms could be discerned under this background adaptation. Under M + L mechanism isolation (Fig. 7E), the ON response showed highest sensitivity at 630 nm and a local peak at 540 nm, denoting L and M mechanism input, respectively. Two sensitivity peaks, at 630 nm and in the range of 400–430 nm, were present under L mechanism isolation (Fig. 7G), indicating inputs from the L and S cone mechanisms.

Fig. 7.

Spectral sensitivity of juvenile rainbow trout under different light-adapting backgrounds derived from electrical recordings of the ONR. A–H: relative spectral sensitivity of ON and OFF responses under UV + short (UV + S; A and B), middle (M; C and D), M + long (M + L; E and F), and L (G and H) cone mechanism(s) isolation. The λ range of the 4 visual pigments (UV, S, M, and L), present in the retina of juvenile rainbow trout of this size, is indicated at the bottom of H. Each point is the mean ± SD of n = 5 (A, B, G, and H) and n = 3 (C–F). Adapted, with permission, from Beaudet (1997).

In contrast to the ON response, the OFF response consistently showed prominent input from the M mechanism regardless of adapting background, with sensitivity peaks in the range of 520–540 nm (Fig. 7, B, D, F, and H). Under UV + S (Fig. 7B) or L (Fig. 7H) mechanism isolation, sensitivity in the short λs (410–430 nm) rivaled that in the middle λs (peak at 540 nm), denoting input from the S mechanism. Thus S cone input to the OFF response was only present when the sensitivity of the M mechanism was depressed through chromatic adaptation. Under M (Fig. 7D) or M + L (Fig. 7F) mechanism isolation, when the M mechanism adaptation was minimal, its input dominated the OFF response (peak at 520 nm).

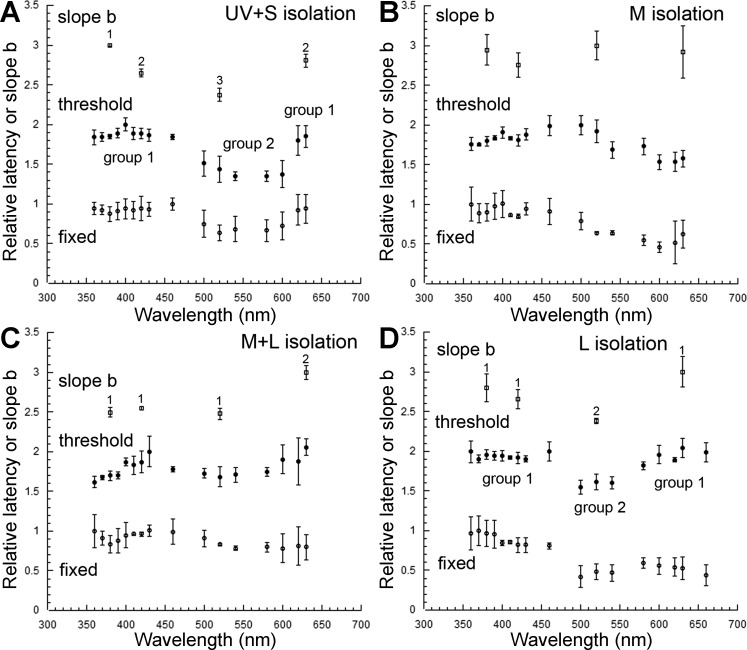

Chromatic adaptation decreases ON response latency and its rate of change.

Over the range of stimulus intensities used and for any particular background adaptation, latency decreased with increasing stimulus intensity, according to Eq. 1. The relative rate of latency decrease (i.e., slope b of Eq. 1) of the ON response varied across the spectrum and depended on the adapting background (Fig. 8; see top traces). In general, slope b was highest for the isolated and lowest for the adapted cone mechanisms. An exception to this rule occurred under UV + S mechanism isolation (Fig. 8A), where b was higher at 630 than at 420 nm, even though the sensitivity of the L mechanism was lower than that of the S mechanism (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 8.

Latency of the juvenile rainbow trout ON response under different light-adapting backgrounds. A–D: slope b and latency at threshold and for a fixed stimulus of the ON response in the case of UV + S (A), M (B), M + L (C), and L (D) cone mechanism isolation. For clarity, in each graph, a value of 1 and 2 was added to the latency at threshold and slope b normalized means, respectively, to displace them vertically from the normalized latency means for a fixed stimulus. In each graph, statistical difference between slope b means is indicated by a different number. In A and D, groups of latencies at threshold with statistically different means are assigned different numbers (groups 1 and 2). Statistical difference between latencies at threshold for 4 specific λs (380, 420, 520, and 630 nm) represented in all graphs is shown in Table 2. Each point is the mean ± SD of n = 5 (A and D) and n = 3 (B and C). Adapted, with permission, from Beaudet (1997).

Under M mechanism isolation, the differences in slope b across the spectrum were not statistically significant (Fig. 8B), as may have been expected from the M mechanism dominance of the ON response (Fig. 7C). Under M + L mechanism isolation, slope b at 380 and 420 nm was significantly lower than at 630 nm (Fig. 8C), the latter result driven by the least adapted and thus most sensitive L cone mechanism (Fig. 7E). The slope b at 520 nm was significantly lower than at 630 nm but similar to that at 380 and 420 nm, reflecting the dominance of the M mechanism at shorter λs. Under L mechanism isolation, slope b was highest at 630 nm, lowest at 520 nm, and intermediate at 380 and 420 nm (Fig. 8D) in accordance with the relative sensitivities of the various cone mechanisms (Fig. 7G).

Parallels could be established between the effects of chromatic adaptation on slope b and on the latency of the ON response. In both cases, latency at threshold and slope b tended to be smaller for the adapted cone mechanisms (Fig. 8; compare top and middle traces). Table 1 lists the mean maximum and minimum latencies at threshold for the various adapting backgrounds and the λs at which they occurred, and Table 2 shows the results from the statistical analyses. The largest difference in latency for the ON response (28 ms) was found between 630 and 500 nm, under L mechanism isolation. For the OFF response, the largest difference was 30 ms, between 360 and 600 nm, under UV + S mechanism isolation, and between 500 and 630 nm, under M + L mechanism isolation.

Table 1.

Relative difference (maximum − minimum) in latency at threshold and for a fixed stimulus intensity under chromatic isolation of various cone mechanisms

| Mechanism(s) isolated | UV + S | UV + S | M | M | M + L | M + L | L | L |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Response parameter | λ, nm | Latency, ms | λ, nm | Latency, ms | λ, nm | Latency, ms | λ, nm | Latency, ms |

| ON Threshold | ||||||||

| Maximum | 400 | 61 ± 3 | 500 | 57 ± 8 | 630 | 56 ± 4 | 630 | 65 ± 11 |

| Minimum | 540 | 34 ± 5 | 600 | 34 ± 3 | 360 | 47 ± 4 | 500 | 37 ± 9 |

| Difference | 27 | 23 | 9 | 28 |

| ON Fixed Intensity | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 460 | 60 ± 3 | 400 | 50 ± 4 | 430 | 43 ± 1 | 370 | 52 ± 5 |

| Minimum | 520 | 47 ± 4 | 600 | 39 ± 4 | 600 | 38 ± 0 | 500 | 36 ± 4 |

| Difference | 13 | 11 | 5 | 16 |

| OFF Threshold | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maximum | 360 | 63 ± 3 | 430 | 72 ± 7 | 500 | 79 ± 10 | 460 | 67 ± 7 |

| Minimum | 600 | 33 ± 4 | 600 | 48 ± 7 | 630 | 49 ± 14 | 500 | 43 ± 8 |

| Difference | 30 | 24 | 30 | 24 |

UV, ultraviolet cone mechanism; S, short wavelength (λ) cone mechanism; M, middle λ cone mechanism; L, long λ cone mechanism; ON, optic nerve response (ONR) to light onset; OFF, ONR to light termination. Adapted, with permission, from Beaudet (1997).

Table 2.

Statistical groupings of latency differences between the various cone mechanisms

| Mechanism Isolated | ON Response | OFF Response |

|---|---|---|

| UV + S | (UV, S, L) (M) | (UV, S, M) (L) |

| M | (UV, S, M) (L) | (S) UV, M (L) |

| M + L | (UV, M) S (L) | (UV, S, M, L) |

| L | (UV, S, L) (M) | (UV, S) (M, L) |

Significant difference present only between mechanisms enclosed in different sets of parentheses. No significant difference within sets of parentheses or between groups in parentheses and mechanism not enclosed in parentheses. λs of mechanisms analyzed: UV, 380 nm; S, 420 nm; M, 520 nm; and L, 630 nm. Adapted, with permission, from Beaudet (1997).

Under UV + S mechanism isolation, there were two statistically different groups of latencies: those encompassing λs <500 and >600 nm and those in between, i.e., 500–600 nm (Fig. 8A, middle trace). Latencies were significantly shorter for the latter group, corresponding to the lowest sensitivity of the M mechanism (Fig. 7A). Under M mechanism isolation (Fig. 8B), there was a trend toward longer latencies in the middle part of the spectrum, but only the 630-nm latency was significantly different from that at 520 nm (Table 2). This result confirmed the dominance of M input in the short and middle λ parts of the spectrum (Fig. 7C). The results under M + L (Fig. 8C) and L (Fig. 8D) mechanism isolation followed the trends derived from the analysis of slope b, in that latency was not statistically different among the UV, S, and M mechanisms under M + L isolation, and latencies followed the relative sensitivities of cone mechanisms under L mechanism isolation (Table 2 and Fig. 7G).

Because chromatic adaptation led to differences in slope b across the spectrum, differences in latency between cone mechanisms were expected to diminish with increasing stimulus intensity. This hypothesis was tested by determining latency for a fixed stimulus intensity (1013 photons cm−2s−1) across the spectrum. In this case, stimulus intensity was near threshold for the less-sensitive cone mechanisms and above threshold for the most sensitive ones. As expected, the overall differences in latency across the spectrum diminished compared with those found at threshold, regardless of adapting background (Fig. 8; compare middle and lower traces).

Chromatic adaptation reveals multiple cone mechanism input to the OFF latency response.

Latency at threshold for the OFF response varied significantly across the spectrum under various adapting backgrounds (Fig. 9). Under UV + S mechanism isolation, two statistically different groups of latencies were found corresponding to λs <550 and >550 nm (Fig. 9A). The homogeneity in latencies <550 nm and the variability in the OFF response in the UV to short λs (Fig. 7B) suggest that the latter sensitivity was primarily due to the M mechanism β-band absorption. The second group of latencies, corresponding to λs >550 nm, indicated input from the L cone mechanism, although such input was not readily apparent from the spectral sensitivity results (Fig. 7B).

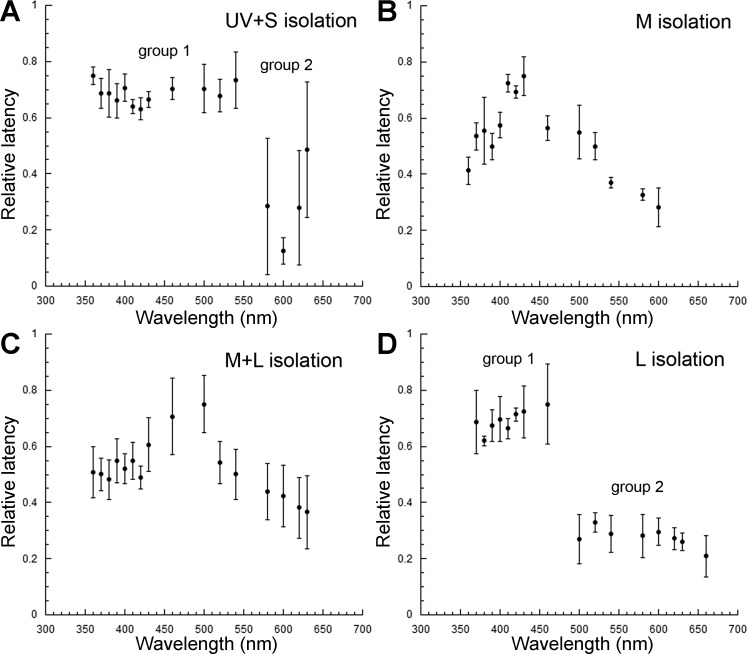

Fig. 9.

Latency of the juvenile rainbow trout OFF response under different light-adapting backgrounds. A–D: relative latency of the OFF response in the case of UV + S (A), M (B), M + L (C), and L (D) cone mechanism isolation. A and D: groups of latencies with statistically different means are assigned different numbers (groups 1 and 2). Statistical difference between latencies for 4 specific λs (380, 420, 520, and 630 nm), represented in all graphs, is shown in Table 2. Each point is the mean ± SD of n = 5 (A and D) and n = 3 (B and C). Adapted, with permission, from Beaudet (1997).

Under M mechanism isolation, longer latencies at short λs (ca. 420 nm) indicated the presence of S mechanism input (Fig. 9B), although this was also not apparent from the spectral sensitivity curve (Fig. 7D). Differences in latency between the short and long λs were statistically significant (Table 2). Under M + L mechanism isolation (Fig. 9C), when the OFF sensitivity response was characterized by a single peak at 520 nm (Fig. 7F), latencies were not significantly different (Table 2). Two groups of latencies were found under L mechanism isolation corresponding to λs <500 and >500 nm (Fig. 9D). Although in this situation, sensitivity was similar for the two OFF peaks (occurring in the short and middle λs), latency was nonetheless longer at shorter λs. This suggests inherent latency differences between the S and M cone mechanisms.

DISCUSSION

ON and OFF response maxima vary in topographical location and as a function of stimulus and background parameters.

The general pattern of ganglion cell projections to the optic tectum of rainbow trout and the shape of associated responses conformed to those reported previously in this and other species (Beaudet et al. 1993; DeMarco and Powers 1991; Schwassmann and Kruger 1965; Vanegas 1984). In particular, the optic nerve response comprised two major positive deflections with a negative deflection in between, and each deflection comprised multiple components corresponding to the three to five optic nerve fiber velocities previously found in several fish species (Northmore and Oh 1998; Vanegas et al. 1974). The general pattern of retinotectal projections, whereby front, back, top, and bottom of the visual field mapped onto corresponding areas of the optic tectum (Ben-Tov et al. 2013; Gosse et al. 2008; Schwassmann and Kruger 1965; Vanegas 1984), was also found in rainbow trout.

Within this general pattern of retinotectal projections, ON and OFF responses varied in their location of maximal response, indicating segregation of these two fiber types in the optic tectum. As per similar optical recordings obtained from the optic tectum of the frog (Grinvald et al. 1984), the source of our signals was a combination of ganglion cell afferents and postsynaptic cells. Given a maximum diameter of 300 μm for the arborization of a single afferent terminal (Grinvald et al. 1984; Ito et al. 1984) and the small area of tectum that typically comprised responses with amplitude >90% of the maximal response (∼0.09 mm2), we surmise that the responses analyzed comprised contributions from a small number of localized terminals and their connections. Afferent ganglion cell fiber input spreads first laterally and afterwards vertically along the optic tectum (Kinoshita et al. 2002; Vanegas 1984), but this spread is depressed by inhibitory mechanisms in live preparations (Grinvald et al. 1984) and was likely excluded in our measurements, which focused on the short latency response.

Segregation of ON, OFF, and ON-OFF fiber types to different sublaminar layers has been demonstrated in the zebrafish, where the ON and OFF fibers form reverse gradients as a function of tectal depth (Robles et al. 2013). Although this vertical separation may also occur in rainbow trout, our results indicate segregation of fibers along the longitudinal (sagittal) direction. Longitudinal segregation of ON and OFF responses has also been reported in the optic tectum of toads (Schwippert et al. 1996) and along the dorsolateral geniculate nucleus of the rat (Davidowa and Gabriel 1985). These studies, however, did not record from ganglion cell fibers, so it is possible that the differences observed could have arisen from postsynaptic processes rather than local segregation of fiber input.

The relative location of ON and OFF maxima further varied with stimulus λ and background adaptation. Such observations can be understood based on the unequal distributions of cone types in the rainbow trout retina (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007) and differential activation of cone mechanisms as a function of background adaptation (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique 2012). It is well known that background adaptation changes the activity of different cone types and induces alterations to the center-surround organization of ganglion cell receptive fields (Field et al. 2007; O'Benar 1976; van Dijk and Spekreijse 1984). Because a diffuser was placed before the fish's eye, the entire retina was illuminated, although the majority of light remained directed at the temporal retina. Under such background conditions, the difference in maximal response location between ON and OFF fibers suggests heterogeneity in the distribution of ON and OFF inputs to the optic tectum. These results are likely based on different combinations of cone types being most active coupled to corresponding chromatic fibers that are ON, OFF, or ON-OFF, as has been reported in several fishes, including the rainbow trout (Coughlin and Hawryshyn 1994; Jacobson and Gaze 1964; O'Benar 1976; van Dijk and Spekreijse 1984).

The large shift in OFF maximal response location when the background was changed from full-spectrum light to longer (>430 nm) λs indicates that multiple cone mechanisms contributed to the OFF response with varying topographic strength. Double cones, which carry M and L visual pigments, are twice as numerous as single cones, which house UV or S visual pigments, in the ventral retina of juvenile rainbow trout, but the ratio is 1:1 in the dorsal retina (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007). These differences alone would predict a shift of response maxima toward the dorsal retina (lateral optic tectum) if the combination of inputs favored that from single cones, as was the case when changing adaptation from full spectrum to a longer λ background. Nonetheless, the shift was more pronounced for the OFF than the ON response, indicating unequal contributions of the various cone types to the ON and OFF information channels (as found in a more detailed analysis; Figs. 7–9). Previous recordings from single units in the optic nerve of rainbow trout revealed OFF responses in which M and L input opposed S input (Coughlin and Hawryshyn 1994). Thus the depression of M and L input through chromatic adaptation would further unveil S input at locations associated with single cone preponderance, as we found.

While our results show dynamic segregation of ON and OFF input to the optic tectum, the nature of the electrical and optical recordings performed here limits our understanding at the single cell level of how retinal output is transmitted to the tectum and how this output changes as a function of adaptation. For example, the optic nerve signals measured here represent the combined activity of multiple ganglion cells whose spiking rate, polarity, latency, and firing mode (e.g., phasic, tonic) are expected to vary within the population, as shown for other vertebrates (Asari and Meister 2012; Devries and Baylor 1997). The optical signals recorded from the optic tectum likewise represent population averages of the neurons and axon terminals underlying each imaged pixel or group of pixels. As a result, it is impossible from our recordings to disambiguate changes in ON or OFF response amplitude or latency from changes in other features, such as synchrony of activation across units or changes in tonic activity levels. Some of these response features may be important under different adaptation backgrounds and types of visual stimuli not tested in our study, and we expect that there is very likely a higher degree of diversity in ganglion cell responses than is reflected in these population measurements. Nonetheless, the fact that we observed significant changes in ON and OFF population response patterns within a preparation as a function of chromatic adaptation shows that these channels carry information from different combinations of cone mechanisms, are highly dynamic in their activity patterns, and appear segregated longitudinally at the level of the optic tectum. Additional studies at the single cell level are important to understand the detailed impacts that adaptation has on retinal processing and the response of distinct output channels.

Although ON and OFF amplitudes varied with topographical location over the tectal surface, ON responses tended to be overall larger than OFF responses. Recordings from giant danio bipolar cells (Wong and Dowling 2005) found more cells with ON vs. OFF characteristics, raising the possibility that the differences in ON vs. OFF magnitude observed in this study could be due to a higher density of ON bipolar cells. Another possibility may be that ON ganglion cells have larger receptive fields or faster kinetics than OFF ganglion cells in the rainbow trout retina, as occurs in several species of mammals, including primates (Chichilnsky and Kalmar 2002). Such attributes would improve the gain of ON ganglion cells, as these could sample a larger portion of the cone mosaic (via bipolar cells) and preferentially contribute to the short latency response analyzed. Other mechanisms that may have contributed to the relative magnitude and latency between ON and OFF responses involve inhibitory mechanisms that modulate the output of specific bipolar and ganglion cell types and neighboring postsynaptic cells in the optic tectum. These inhibitory mechanisms are particularly active in the light-adapted retina, sharpening the spatial and temporal aspects of the response to visual stimuli (Masland 2012; Roska et al. 2006; Wässle 2004).

Localization of the UV cone-driven signal to the dorsal retina of juvenile rainbow trout.

UV cones are present in the retinas of nonmammalian vertebrates and small mammals in varying numbers and topographical location (Novales Flamarique 2012), yet the contribution of these cones to neural pathways beyond the retina is widely unknown. In rainbow trout, electrical recordings from the optic tectum failed to find any single units with UV cone-driven input (Coughlin and Hawryshyn 1994), despite this brain center receiving the bulk of retinal projections (Pinganaud and Clairambault 1979). Our chromatic adaptation studies show that UV cone-driven input is primarily restricted to the lateral optic tectum, in accordance with the prevalence of this cone type in the dorsal retina of juvenile rainbow trout of this size (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007). The lack of evidence found in previous single-unit studies probably resulted from limited topographic sampling at a time when the cone distributions in the retina of this animal were unknown.

Under conditions that isolated the UV cone mechanism by depressing the L cone mechanism, the UV and S OFF responses to a suprathreshold stimulus were nearly absent. The M mechanism, which dominated the OFF response, exhibited opposite gradients in maximal response location between ON and OFF fibers. These results were similar to the gradients of ON-OFF fiber input observed under conditions that preferentially adapted the longer λ (M + L) cone mechanisms, although in the latter experiments, the L cone mechanism was more active. Negative interactions between L and M cone mechanisms have been documented in a variety of fishes (Burkhardt 2014; Connaughton and Nelson 2010; O'Benar 1976; van Dijk and Spekreijse 1984), and our results indicate that their relative state of adaptation determines the magnitude of the single cone (UV or S) (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007) mechanism OFF response in rainbow trout.

Latency analysis reveals inputs from the S and L cone mechanisms to the OFF response.

As per previous studies on rainbow trout (Beaudet et al. 1993; Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997), spectral sensitivity results showed a dominant contribution of the M cone mechanism to the OFF response. The incorporation of latency into the analysis further revealed smaller contributions of the S and L cone mechanisms. These results are consistent with the reported predominance of single units with M mechanism OFF input in the optic nerve and brain of juvenile rainbow trout (Coughlin and Hawryshyn 1994). Of the 38 units recorded by these authors, 29 received M OFF input compared with 9 and 1 that received L and S input, respectively. Because their study was restricted to the ventral retina, the domination of double cones over single cones in this area of the retina (Cheng and Novales Flamarique 2007) likely influenced the low number of OFF S units measured.

The contribution of the S cone mechanism to the OFF response was most prominent when the M mechanism was depressed by chromatic adaptation. This indicates a negative interaction between the S and M cone mechanisms, as has been shown in cyprinid fishes (Connaughton and Nelson 2010; McDowell et al. 2004; van Dijk and Spekreijse 1984) and macaques (De Monasterio et al. 1975; Field et al. 2007; Valberg et al. 1986). The finding of a displacement of the M OFF sensitivity peak from 520 to 540 nm under L mechanism isolation concurs with psychophysically derived results from goldfish that illustrate inhibitory action of the S on the M cone mechanism (Neumeyer 1984). In our study, unveiling the full complexity of cone mechanism inputs to the ON and OFF responses necessitated both latency and spectral sensitivity analyses.

Chromatic adaptation and latency: implications for neuronal coding and retinal specializations.

The latencies of the responses from the various cone mechanisms were affected by retinal adaptation. This was especially the case when the backgrounds were spectrally biased, i.e., when they chromatically adapted the retina. A multitude of studies have shown that increases in background intensity and hence, in the level of light adaptation of photoreceptors lead to decreases in the time course of their response at threshold (Baylor and Hodgkin 1974; Daly and Normann 1985; Koch 1992; Peachy et al. 1989). Adaptation in cones also results in the shifting of the response curve along the stimulus-intensity axis and its compression (Cone 1964; Normann and Werblin 1974), which is also the pattern exhibited by other retinal neurons, including horizontal, bipolar, amacrine, and ganglion cells (Werblin 1974; Werblin and Copenhaggen 1974). Our study shows that not only the latency but also the rate of latency change as a function of stimulus intensity (slope b) were affected by light adaptation. Light adaptation decreased the rate at which latency decreased with stimulus intensity, a phenomenon also observed in frog retinal ganglion cells (Donner 1981b; Donner et al. 1995, 1998), although the effect of chromatic adaptation was not investigated in these studies. The functional implication of this adaptation-dependent change in slope b is that increases in stimulus intensity beyond threshold lead to decreases in latency differences across the spectrum. Thus temporally sensitive interactions between cone mechanisms depend not only on the relative state of adaptation of each mechanism but also on stimulus intensity.

A main conclusion of our study is that chromatic adaptation results not only in shifts in the relative sensitivity of the various cone mechanisms but also on their temporal properties. Such dynamic modulation in the timing of ON and OFF inputs to the optic tectum should have important consequences for neuronal integration and encoding of visual scenery. The differences in latency observed across the spectrum suggest that differential adaptation could determine whether different chromatic inputs to higher levels of processing may temporally coincide, thereby influencing the efficacy of opponent interactions and the organization of receptive fields (Donner 1981a, b). An example illustrating the importance of such timing can be found in the primate retina, where a delay between the response of the receptive field center and surround leads to different behaviors of retinal ganglion cells depending on the frequency of light flicker: at high frequency, chromatic stimuli trigger responses characteristic of the achromatic channel (Gouras and Zrenner 1979).

The underwater environment operates as a dynamic chromatic-adapting background, where the intensity and spectral distribution change according to direction of sight, water depth, and time of day (Novales Flamarique and Hawryshyn 1997; Novales Flamarique et al. 1992). Under daylight conditions, the upwelling, longer λ spectrum would preferentially isolate the UV and S cone mechanisms in the dorsal retina of the rainbow trout, whereas the downwelling, full spectrum would favor higher sensitivity to middle λs in the ventral retina (Novales Flamarique and Hárosi 2000; Novales Flamarique et al. 2007). Juvenile rainbow trout generally prey on drifting zooplankton and insects close to the water surface and are, in turn, preyed on by larger fishes coming at oblique angles from below. Predation on slow-drifting organisms that cast a shadow over the ventral retina (Beaudet et al. 1993) and avoidance of fast predators that reflect shorter λs with respect to the upwelling background (Novales Flamarique et al. 2007) are consistent with the spatiotemporal specializations in the rainbow trout retina. Not only are combinations of cone mechanisms strategically more active in different parts of the retina to provide higher contrast depending on the ecological task (UV and S ON responses in the dorsal retina, M OFF response in the ventral retina), but also, the overall latency of the response is shorter in the dorsal retina, in accordance with the fast reaction times needed to avoid predation. Thus the underwater light environment, through chromatic adaptation, should affect the temporal interactions in the visual system of juvenile rainbow trout, and this has likely shaped the functional segregation of retinotectal fibers and their highly dynamic response characteristics.

GRANTS

Support for this work was provided by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Discovery Grant 31-611336 (to I. Novales Flamarique). Some of the data was obtained in the laboratory of Dr. Lawrence B. Cohen at the Marine Biological Laboratory (Woods Hole, MA), and support for that work was provided by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant NS08437 (to Dr. Lawrence B. Cohen) and Marine Biological Laboratory Summer Research Fellowships (to I. Novales Flamarique).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: I.N.F. conception and design of research; I.N.F. and M.W. performed experiments; I.N.F. analyzed data; I.N.F. interpreted results of experiments; I.N.F. prepared figures; I.N.F. drafted manuscript; I.N.F. and M.W. edited and revised manuscript; I.N.F. and M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Dr. Luc Beaudet for granting permission to use data and analyses from his Ph.D. thesis toward Figs. 7–9 and Tables 1 and 2 of the manuscript and for reviewing it and Dr. Lawrence B. Cohen for reviewing the manuscript.

Present address of M. Wachowiak: Dept. of Neurobiology and Anatomy and Brain Institute, Univ. of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT 84112.

REFERENCES

- Asari H, Meister M. Divergence of visual channels in the inner retina. Nat Neurosci 15: 1581–1589, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baylor DA, Hodgkin AL. Changes in time scale and sensitivity in turtle photoreceptors. J Physiol 242: 729–758, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet L. Adaptation Mechanisms in the Salmonid Visual System (PhD thesis) Victoria, BC, Canada: University of Victoria, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudet L, Browman HI, Hawryshyn CW. Optic nerve response and retinal structure in rainbow trout of different sizes. Vision Res 33: 1739–1746, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Tov M, Kopilevich I, Donchin O, Ben-Shahar O, Giladi C, Segev R. Visual receptive field properties of cells in the optic tectum of the archer fish. J Neurophysiol 110: 748–759, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt DA. Signals for color and achromatic contrast in the goldfish inner retina. Vis Neurosci 31: 365–371, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng CL, Novales Flamarique I. Chromatic organization of cone photoreceptors in the retina of rainbow trout: single cones irreversibly switch from UV (SWS1) to blue (SWS2) light sensitive opsin during natural development. J Exp Biol 210: 4123–4135, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichilnisky EJ, Kalmar RS. Functional asymmetries in ON and OFF ganglion cells of primate retina. J Neurosci 22: 2737–2747, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone RA. The rat electroretinogram. I. Contrasting effects of adaptation on the amplitude and latency of the b-wave. J Gen Physiol 47: 1089–1105, 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connaughton VP, Nelson R. Spectral responses in zebrafish horizontal cells include a tetraphasic response and a novel UV-dominated response. J Neurophysiol 104: 2407–2422, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway BR. Color signals through dorsal and ventral visual pathways. Vis Neurosci 31: 197–209, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlin DJ, Hawryshyn CW. The contribution of ultraviolet and short-wavelength sensitive cone mechanisms to color vision in rainbow trout. Brain Behav Evol 43: 219–232, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly SJ, Normann RA. Temporal information processing in cones: effects of light adaptation on temporal summation and modulation. Vision Res 25: 1197–1206, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidowa H, Gabriel HJ. Distribution of ON- and OFF-cells within the rat dorsal lateral geniculate nucleus. Biomed Biochim Acta 44: 1735–1737, 1985. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Monasterio FM, Gouras P, Tolhurst DJ. Trichromatic colour opponency in ganglion cells of the rhesus monkey retina. J Physiol 251: 197–216, 1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMarco PJ Jr, Powers MK. Spectral sensitivity of ON and OFF responses from the optic nerve of goldfish. Vis Neurosci 6: 207–217, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries S, Baylor DA. Mosaic arrangement of ganglion cell receptive fields in rabbit retina. J Neurophysiol 78: 2048–2060, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhande OS, Huberman AD. Retinal ganglion cell maps in the brain: implications for visual processing. Curr Opin Neurobiol 24: 133–142, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner K. How the latencies of excitation and inhibition determine ganglion cell thresholds and discharge patterns in the frog. Vision Res 21: 1689–1692, 1981a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner K. Receptive fields of frog retinal ganglion cells: response formation and light-dark adaptation. J Physiol 319: 131–142, 1981b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner K, Hemilä S, Koskelainen A. Light adaptation of cone photoresponses studied at the photoreceptor and ganglion cell levels in the frog retina. Vision Res 38: 19–36, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donner K, Koskelainen A, Djupsund K, Hemilä S. Changes in retinal time scale under background light: observations on rods and ganglion cells in the frog retina. Vision Res 35: 2255–2266, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field GD, Sher A, Gauthier JL, Greschner M, Shlens J, Litke AM, Chichilnisky EJ. Spatial properties and functional organization of small bistratified ganglion cells in primate retina. J Neurosci 27: 13261–13272, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosse NJ, Nevin LM, Baier H. Retinotopic order in the absence of axon competition. Nature 452: 892–896, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras P, Zrenner E. Enhancement of luminance flicker by color-opponent mechanisms. Science 205: 587–589, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grinvald A, Anglister L, Freeman JA, Hildesheim R, Manker A. Real-time optical imaging of naturally evoked electrical activity in intact frog brain. Nature 308: 848–850, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YK, Kim IJ, Sanes JR. Stereotyped axonal arbors of retinal ganglion cell subsets in the mouse superior colliculus. J Comp Neurol 519: 1691–1711, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horder TJ, Martin KA. Some determinants of optic terminal localization and retinotopic polarity within fibre populations in the tectum of goldfish. J Physiol 333: 481–509, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito H, Vanegas H, Murakami T, Morita Y. Diameters and terminal patterns of retinofugal axons in their target areas: an HRP study in two teleosts (Sebasticus and Navodon). J Comp Neurol 230: 179–197, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M, Gaze RM. Types of visual response from single units in the optic tectum and optic nerve of goldfish. Q J Exp Physiol Cogn Med Sci 49: 199–209, 1964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jagger WS, Sands PJ. A wide-angle gradient index optical model of the crystalline lens and eye of the rainbow trout. Vision Res 36: 2623–2639, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita N, Ueda R, Kojima S, Sato K, Watanabe M, Urano A, Ito E. Multiple-site optical recording for characterization of functional synaptic organization of the optic tectum of rainbow trout. Eur J Neurosci 16: 868–876, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch KW. Biochemical mechanism of light adaptation in vertebrate photoreceptors. Trends Biochem Sci 17: 307–311, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luckenbills-Edds L, Sharma SC. Retinotectal projection of the adult winter flounder (Pseudopleuronectes americanus). J Comp Neurol 173: 307–318, 1977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makhankov YV, Rinner O, Neuhauss SC. An inexpensive device for non-invasive electroretinography in small aquatic vertebrates. J Neurosci Methods 135: 205–210, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin PR, Lee BB. Distribution and specificity of S-cone (“blue cone”) signals in subcortical visual pathways. Vis Neurosci 31: 177–187, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masland H. The neuronal organization of the retina. Neuron 76: 266–280, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CG, Haimberger TJ, Hawryshyn CW. Wavelength-dependent waveform characteristics of tectal evoked potentials in rainbow trout. Can J Zool 82: 1614–1620, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McDowell AL, Dixon LJ, Houchins JD, Bilotta J. Visual processing of the zebrafish optic tectum before and after optic nerve damage. Vis Neurosci 21: 97–106, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumeyer C. On spectral sensitivity in the goldfish. Evidence for neural interactions between different “cone mechanisms”. Vision Res 24: 1223–1231, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nevin LM, Robles E, Baier H, Scott EK. Focusing on optic tectum circuitry through the lens of genetics. BMC Biol 8: 126, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou N, Lowe AS, Walker AS, Abbas F, Hunter PR, Thompson ID, Meyer MP. Parametric functional maps of visual inputs to the tectum. Neuron 76: 317–324, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Normann RA, Werblin FS. Control of retinal sensitivity. I. Light and dark adaptation of vertebrate rods and cones. J Gen Physiol 63: 37–61, 1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northmore DP, Oh DJ. Axonal conduction velocities of functionally characterized retinal ganglion cells in goldfish. J Physiol 506: 207–217, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I. Opsin switch reveals function of the ultraviolet cone in fish foraging. Proc Biol Sci 280: 20122490, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I. Temporal shifts in visual pigment absorbance in the retina of Pacific salmon. J Comp Physiol A 191: 37–49, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I, Hárosi FI. Photoreceptors, visual pigments, and ellipsosomes in the killifish, Fundulus heteroclitus: a microspectrophotometric and histological study. Vis Neurosci 17: 403–420, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I, Hawryshyn CW. Is the use of underwater polarized light by fish restricted to crepuscular time periods? Vision Res 37: 975–989, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I, Hawryshyn CW. The common white sucker (Catostomus commersoni): a fish with ultraviolet sensitivity that lacks polarization sensitivity. J Comp Physiol A 182: 331–341, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I, Hendry A, Hawryshyn CW. The photic environment of a salmonid nursery lake. J Exp Biol 169: 121–141, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Novales Flamarique I, Mueller GA, Cheng CL, Figiel CR. Communication using eye roll reflective signalling. Proc Biol Sci 274: 877–882, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Benar JD. Electrophyiology of neural units in goldfish optic tectum. Brain Res Bull 1: 529–541, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peachey NS, Alexander KR, Fishman GA, Derlacki DJ. Properties of the human cone system electroretinogram during light adaptation. Appl Opt 28: 1145–1150, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]