Abstract

Background

Transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) is the most common treatment for patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). Post-embolization syndrome (PES) is a common post-TACE complication. The goal of this study was to evaluate PES as an early predictor of the long-term outcome.

Methods

A retrospective cohort study of HCC patients treated with TACE at a tertiary referral centre was performed (2008–2014). Patients were categorized on the basis of PES, defined as fever with or without abdominal pain within 14 days of TACE. The primary outcome was overall survival (OS). Multivariate Cox regression was done to examine the association between PES and OS.

Results

Among 144 patients, 52 (36.1%) experienced PES. The median follow-up for the cohort was 11.4 months. The median and 3-year OS rates were 16 months and 18% in the PES group versus 25 months and 41% in the non-PES group (log rank, P = 0.027). After multivariate analysis, patients with PES had a significantly increased risk of death [hazard ratio 2.0 (95%CI 1.2–3.3), P = 0.011].

Conclusions

PES is a common complication after TACE and is associated with a two-fold increased risk of death. Future studies should incorporate PES as a relevant early predictor of OS and examine the biological basis of this association.

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is the fifth most common malignancy worldwide with over 700 000 new cases diagnosed annually and is the second leading cause of cancer-related death.1,2 It is the fastest growing cause of cancer-related mortality, and has a poor prognosis with 5-year overall survival (OS) rates of less than 12%.3 Liver transplantation and liver resection are the only potentially curative treatments, but only a small proportion of patients are candidates for these therapies.4,5 A number of locoregional liver-directed therapies are currently available for patients not amenable to curative treatment, with transarterial chemoembolization (TACE) among the most commonly used. TACE is indicated as a primary treatment (palliative), in combination with other treatments, or as a bridge to surgery – more commonly while waiting for liver transplantation.6,7

As a primary treatment, TACE has been associated with an improved OS when compared with best supportive care in several randomized trials, with reported 3-year OS rates of 26–47%, as compared with as low as 3% for untreated patients.8–10 These findings have been confirmed by at least three recent meta-analyses,11–13 and support recommendations by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and other international guidelines to use TACE as the treatment of choice for patients with advanced, unresectable HCC.6,14 Based on this, it is estimated that TACE will target at least 20% of the HCC population, and indeed, a population-level study from Japan revealed that TACE was the most commonly used therapy, treating over 36% of patients presenting with HCC.14,15 Notwithstanding the improved survival observed with TACE, a number of prognostic factors such as vascular invasion and advanced liver disease have been found to carry a significantly worse prognosis,16 and TACE provides only a minimal survival benefit in these settings for which alternative and more effective therapies are evolving.17 Likewise, recent studies have emphasized the role of inflammatory serum markers as prognostic factors after TACE. However, no clinical data have been identified to correlate these with a worse prognosis.18–20 Although TACE has been shown to be safe with low rates of severe complications,5,21,22 post-embolization syndrome (PES) – a post-inflammatory clinical syndrome defined by fever and right upper quadrant abdominal pain with or without nausea and vomiting – is a common complication,23–27 and there are currently no available data evaluating the impact of PES on the long-term outcome.

Based on this, using a contemporary cohort of HCC patients, we sought to characterize the incidence of PES after TACE and its association with long-term outcomes. The primary goal of the present study was to examine the impact of PES on OS in patients with advanced, unresectable HCC, who received TACE as the primary treatment strategy. Our hypothesis was that patients experiencing PES after TACE are at an increased risk of death, and that in the setting of other validated risk factors, PES can be used as an early predictor of worse survival for this population.

Patients and methods

Study design

This is a retrospective cohort study of HCC patients treated with TACE at the Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center (MEDVAMC) in Houston, TX, USA. The Baylor College of Medicine institutional review board and the MEDVAMC Research & Development Committee approved the research protocol and waived the requirement to obtain informed consent and HIPAA authorization.

Study setting

The study was conducted at the MEDVAMC in Houston, TX, which is one of 10 VA medical centres within the South Central VA Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN 16). VISN16 provides care for close to 2 million veterans across eight different states. MEDVAMC serves as a tertiary regional and national referral centre for the evaluation and treatment of patients with HCC in the VA system. All patients with HCC referred to the MEDVAMC are evaluated in a multidisciplinary setting during a weekly HCC-specific tumour board, which is staffed by all disciplines involved in the care of HCC and represents the treatment modalities available locally [i.e. transplant, liver resection, ablation, interventional radiology-based liver-directed therapies (including TACE), radiation and systemic therapy].

Study population and data collection

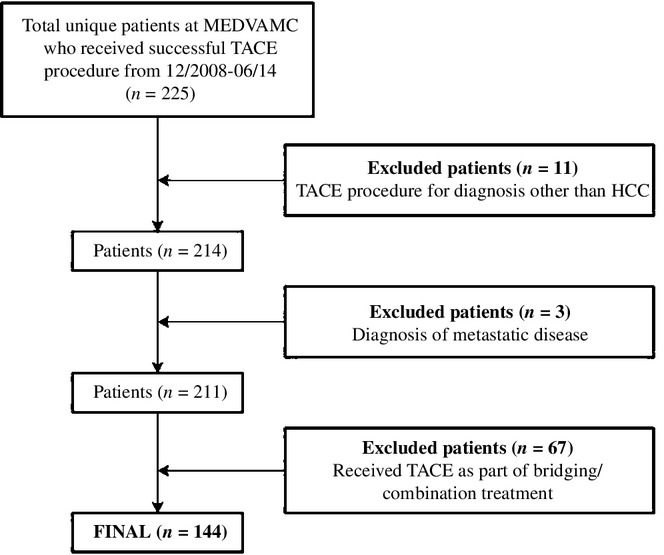

All patients with a confirmed diagnosis of HCC diagnosed by imaging and/or biopsy who were treated with TACE by the MEDVAMC interventional radiology service between 1 December 2008 and 30 June 2014 were eligible for study inclusion. Patients were included if they met the diagnostic criteria for HCC and were treated with TACE as the primary treatment strategy. Patients were excluded if they received any treatment in addition to TACE such as chemotherapy, liver resection, liver transplantation and/or liver ablation procedures, if they had TACE for any diagnosis other than HCC and/or if they had metastatic disease at the time of first TACE (Fig.1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study design and inclusion/exclusion criteria. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MEDVAMC, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, TX; PES, post-embolization syndrome (defined in Methods); TACE, transarterial chemoembolization

Data collection was performed using direct chart review by a trained abstractor with pre-defined algorithms and definitions, and included demographic information, clinical characteristics, measures of liver function, tumour characteristics and Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC) staging. Details regarding the TACE procedure included the embolization technique (selective versus non-selective), the chemotherapy regimen used (single agent versus multiple agents), the type of TACE [conventional versus drug-eluting beads (DEB-TACE)] and the number of TACE procedures performed for each patient. A collection of post-TACE information included the occurrence of complications and severity according to the Dindo–Clavien classification.28 PES was recorded, and defined as a fever with/without right upper quadrant abdominal pain without evidence of sepsis, occurring within 14 days of the first TACE procedure.24,26 As our goal was to include PES as a measure of the inflammatory process, we chose to focus on the clinical hallmark of PES – fever – and did not include measures of cytolysis such as changes in transaminase levels. Additionally, previous studies have described a good correlation between cytolysis and fever after TACE.29 Patients were followed with cross-sectional imaging (MRI and/or CT) and laboratory tests 1 month after TACE and every 3 to 4 months thereafter. The vital status was assessed for all patients, and the date of death was verified when applicable, using the VA electronic medical record and the social security death index.

Statistical analysis

Patients were categorized based on PES, and descriptive statistics were used to compare baseline data and procedure characteristics. Categorical variables were compared using the two-sided chi-square test, and continuous variables were compared using the Student's t-test, Mann–Whitney U-test and Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. The primary outcome of interest was OS, which was measured from the date of the TACE procedure to the date of death of any cause. Patients were censored if alive at the date of last follow-up. OS was estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method and differences in survival functions were compared using the log-rank test. Multivariable Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the association of PES with OS while adjusting for important covariates. The selection of variables for inclusion in the multivariate model was clinically and statistically driven (P < 0.1 on univariate analysis for the primary outcome). PES was also examined as a secondary outcome, and univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were done to identify predictors of PES using the same approach. Hazard ratios (HR) or odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated accordingly. A P-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses. STATA version 12 (STATACORP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses in the study.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics

A total of 144 HCC patients met the criteria and were included in the study (Fig.1). Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table1. Notably, 142 (98.6%) were male, with the majority having a significant burden of comorbidities (Charlson's index ≥ 3 = 79.9%), cirrhosis (95.8%) and associated portal hypertension (69.4%). Likewise, the majority of patients had multifocal disease (> 1 tumour = 68.1%) and 17 (11.8%) had macroscopic vascular invasion (MVI) at presentation. According to BCLC staging, the majority of patients had intermediate or more advanced disease (43.8%), with 16.7% of patients having unstaged disease.

Table 1.

Baseline clinical, tumour and TACE-procedure character-istics, and post-TACE complications for all the study cohort (N = 144)

| Characteristic | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | |

| Mean Age, years (SD) | 62.0 (6.7) |

| Age | |

| <65 years | 101 (70.1) |

| ≥65 years | 43 (29.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 142 (98.6) |

| Female | 2 (1.4) |

| Race | |

| White | 85 (59.0) |

| Non-white | 59 (41.0) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Hispanic | 13 (9.0) |

| Other | 131 (91.0) |

| Clinical Characteristics | |

| Mean BMI, kg/m2 (SD) | 28.0 (5.1) |

| Obesity | |

| BMI <30 | 95 (66.0) |

| BMI ≥30 | 49 (34.0) |

| ECOG performance status | |

| 0–1 | 106 (73.6) |

| 2–4 | 4 (2.8) |

| Unknown | 34 (23.6) |

| Charlson's Comorbidity index | |

| 0–2 | 29 (20.1) |

| ≥3 | 115 (79.9) |

| HCC Aetiology | |

| HCV | 45 (31.3) |

| Alcohol | 11 (7.6) |

| HCV + Alcohol | 69 (47.9) |

| HBV + Alcohol | 5 (3.5) |

| HBV + HCV + Alcohol | 2 (1.4) |

| Other/Unknown | 12 (8.3) |

| Liver Cirrhosis | 138 (95.8) |

| Portal Hypertension | 100 (69.4) |

| Liver Function | |

| Child-Pugh Class | |

| A | 80 (55.6) |

| B | 51 (35.4) |

| C | 13 (9.0) |

| Median MELD Score (Range) | 10 (6–23) |

| Tumour Characteristics | |

| Median AFP, ng/ml (Range) | 17.8 (1.5–303 000) |

| Tumour Type | |

| Primary | 134 (93.1) |

| Recurrent | 10 (6.9) |

| Number of tumours | |

| Solitary | 46 (31.9) |

| Multiple | 98 (68.1) |

| Median largest tumour size, cm (Range) | 3.3 (1–18.5) |

| Distribution | |

| Unilobar | 84 (58.3) |

| Bilobar | 60 (41.7) |

| Macrovascular invasion | 17 (11.8) |

| BCLC Staging | |

| Early | 57 (39.6) |

| Intermediate | 42 (29.2) |

| Advanced | 13 (9.0) |

| Terminal | 8 (5.6) |

| Unknown | 24 (16.7) |

| Procedure Characteristics | |

| Procedure success – first attempt | 143 (99.3) |

| Technique | |

| Selective | 131 (91.0) |

| Non-Selective | 13 (9.0) |

| TACE type | |

| Traditional | 34 (23.6) |

| Beads | 110 (76.4) |

| Chemotherapy type | |

| Single Agent | 108 (75.0) |

| Multiple Agent | 36 (25.0) |

| Number of TACE procedure >1 | 60 (41.7) |

| Median number of TACE procedures (Range) | 1 (1–5) |

| Post-TACE complications | |

| Any Complication | 70 (48.6%) |

| Severe Complication (Dindo ≥3)a | 6 (4.2%) |

| GI bleeding | 4 (2.7%) |

| Severe hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin ≥7.0) | 2 (1.4%) |

| Respiratory failure | 1 (0.7%) |

| Death | 1 (0.7%) |

| Mild Complication | 64 (44.4%) |

| PESb | 52 (36.1%) |

| Nausea/vomiting | 13 (9.0%) |

| Mild hyperbilirubinemia (total bilirubin <7.0) | 7 (4.9%) |

| Ascites | 5 (3.5%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 3 (2.1%) |

| Otherc | 17 (11.8%) |

Severe complications classified as Dindo ≥ 3 includes patients who had one or more of the following that occurred within 30 days of the first TACE procedure: GI bleeding, severe hyperbilirubenemia (total bilirubin ≥7.0), and/or death.

Post-embolization syndrome, defined as a fever with or without right upper quadrant abdominal pain within 14 days of the first TACE procedure.

Other includes: acute kidney injury, urinary retention, haematoma, post-procedure anaemia, pleural effusion, thrombocytopenia, and/or pneumonia.

AFP, alpha-fetoprotein; BCLC, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer; DEB-TACE, beads; BMI, body mass index; GI, gastrointestinal; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; PES, post-embolization syndrome; TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

TACE characteristics and complications post-TACE

The first TACE procedure was successful in 99.3% of the cases with only one patient requiring a second procedure to accomplish chemoembolization. In the majority of the cases, a selective approach targeting the vessel feeding the tumour was used (91%), with only 13 cases requiring a non-selective strategy. Conventional TACE was used in close to one-fourth of all patients, but the majority of the procedures during the whole study period used DEB-TACE (76.4%). Importantly, although the median number of TACE procedures was one (IQR 1–5), 41.7% of patients had more than one TACE procedure performed (Table1).

In all, 70 patients (48.6%) had one or more complications within 30 days after the initial TACE procedure, and only 6 (4.2%) had severe complications (Dindo class ≥ 3) including one death. The most common complication was PES, occurring in a total of 52 patients (36.1%). Details of the specific complications are listed in Table1.

Overall survival and post-embolization syndrome

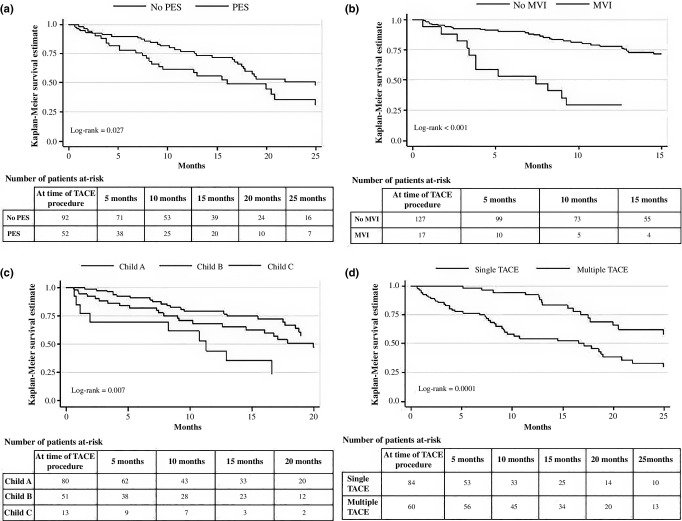

The median follow-up for the whole cohort was 11.4 months (IQR 0.6–49.9). Median and 1-, 3- and 5-year OS rates were 20 months, and 71%, 32% and 0%, respectively. On univariate analysis, when comparing patients with and without PES, survival was significantly better for the latter group with a median OS of 25 months versus 16 months, and 1- and 3-year OS rates significantly higher (77% versus 56%, and 41% versus 18%, respectively, P = 0.027) (Fig.2a). After adjusting for other important variables, PES was associated with an increased risk of death as compared with those without PES [HR 2.0 (95% CI 1.2–3.3); P = 0.011] (Table2).

Figure 2.

Overall survival for HCC patients (N = 144) after a TACE procedure, by (a) the presence of post-embolization syndrome, (b) the presence of macrovascular invasion, (c) liver function using Child–Pugh classification and (d) the number of TACE procedures performed. HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MEDVAMC, Michael E. DeBakey VA Medical Center in Houston, TX; MVI, macrovascular invasion; PES, post-embolization syndrome (defined in Methods); TACE, transarterial chemoembolization

Table 2.

Multivariate Cox regression model examining the association of selected variables with risk of death following TACE (N = 144)

| Predictors of Survival | Hazard Ratio | 95 % Confidence Interval | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG 2–4 (versus 0–1) | 2.5 | 0.7–8.8 | 0.144 |

| ECOG Unknown | 0.6 | 0.3–1.1 | 0.103 |

| Multiple tumors (versus single tumor) | 0.9 | 0.5–1.5 | 0.575 |

| Macrovascular invasion (versus no macrovascular invasion) | 4.5 | 2.4–8.6 | <0.001 |

| Child B (versus Child A) | 1.9 | 1.0–3.4 | 0.040 |

| Child C (versus Child A) | 6.3 | 2.7–14.5 | <0.001 |

| PES (versus no PES) | 2.0 | 1.2–3.3 | 0.011 |

| Multiple TACE (versus single TACE) | 0.4 | 0.3–0.8 | 0.004 |

PES, post-embolization syndrome (defined in Methods); TACE, transarterial chemoembolization.

Other independent predictors of overall survival

Table2 displays results from the multivariate Cox regression model. In addition to PES, the presence of MVI [HR 4.5 (2.4–8.6); P < 0.001] and advanced liver disease [Child-Pugh class B HR 1.9 (1.0–3.4); P = 0.040, and Child-Pugh class C HR 6.3 (2.7–14.5); P < 0.001] were both associated with an increased risk of death. In contrast, having multiple TACE procedures, was associated with a protective effect (HR 0.4 [0.3–0.8]; P = 0.004), when compared with those having only one TACE during the course of the study period. Additional Kaplan–Meier curves for each of these predictors are displayed in Fig.2b–d.

Predictors of post-embolization syndrome

After univariate analysis and using the pre-determined selection criteria, four variables were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. Bilobar versus unilobar disease [OR 2.07 (1.01–4.24); P 0.048] and the use of DEB-TACE, as compared with conventional TACE, [OR 0.44 (0.19–0.98); P 0.045] were identified as independent predictors of PES, while tumour size [OR 0.57 (0.23–1.41); P 0.223] and a non-selective approach [OR 2.21 (0.67–7.22); P 0.191], were not associated with this outcome. Other tumour-related variables such as pre-TACE AFP levels had no correlation with the occurrence of PES.

Discussion

TACE is the most commonly used therapy for patients with HCC and has been shown to provide a survival benefit in those with unresectable disease not amenable to curative treatment.6,14 Although a relatively safe procedure, TACE is often associated with post-embolization syndrome, a clinical syndrome mediated by an inflammatory response associated with the embolization itself and/or chemotherapeutic agent delivered.23–27 Although, a number of studies have shown an association between inflammatory markers after TACE and worse survival,18–20 the role of PES as a prognostic factor in patients with HCC has not been studied. The goals of our study were to examine the incidence of PES in a contemporary cohort of HCC patients treated with TACE and to evaluate its role as an early predictor of worse OS. Using a strict definition, we found that PES was the most common complication after TACE, occurring in over one-third of patients, and after adjusting for important variables, it was associated with a two-fold increased risk of death. Further, we were able to identify specific tumour- and procedure-related characteristics that were associated with the increased risk of PES, including bilobar disease and the use of conventional TACE (as compared with DEB-TACE). These results are significant because, in the context of other well-established prognostic factors, PES can be used to identify a population at an increased risk of death early during the treatment plan. Similarly, understanding that patients are at increased risk of PES provides important information when considering competing treatment alternatives in patients not amenable to surgical treatment.

There are a number of noteworthy points derived from these findings. First, the incidence of PES after TACE varies widely in the literature ranging from 15% up to 90%.23,25,26 This variation is likely related to measurement bias derived from differences in the definitions used and a lack of appropriate follow-up and/or capture of events. We found a PES incidence of 36% using a strict definition based solely on clinical parameters. Although subject to this definition, our results corroborate the high incidence of PES in this population of patients, and this pre-defined criteria allows for future comparisons focused on validating these results. Second, we found that PES after TACE was associated with a worse survival and a two-fold increased risk of death, after adjusting for important confounders. Few studies have explored this association. Jun and colleagues recently published a similar analysis in which no association was found between PES and 20-months overall survival.30 Although these findings are important, they need to be interpreted within the context of marked differences between such a study and ours; specifically, their study included patients from South Korea treated with TACE using lipiodol infusion (100%) – which in turn was associated with higher incidence of PES – whereas in the present study patients were predominantly treated with drug-eluting beads (76%), a more contemporary and accepted strategy for TACE procedures (see next paragraph), and hence the results are not comparable. Importantly, our multivariate model revealed that well-established prognostic factors, including the presence of MVI and the extent of liver disease,16,18–20 were independently associated with a worse survival in our population, providing face validity to our analysis, and hence, strengthening the value of the association between PES and OS. Third, when evaluating predictors of survival after TACE, in addition to these well-established variables, different investigators have reported a variety of procedure-related factors associated with a worse prognosis, such as the selectivity of the approach, the type and number of chemotherapeutic agents used, and the embolization technique.17,31 The findings from this study may explain these differences by emphasizing a more biological relationship between PES, as an inflammatory marker, with long-term outcomes. Other studies have found inflammatory markers, such as a high neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, to be predictive of worse survival,19,20 and our findings potentially validate this concept using a clinical representation of such inflammatory response. However, this biological association will need further study and validation.

The association between PES and a worse survival has significant implications beyond its predictive ability to identify high-risk patients. Our findings indicate that patients experiencing PES derive minimal benefit from TACE, as the median and 3-year overall survival rate are only 16 months and 18%, respectively. A novel approach to more aggressive treatment strategies or multimodality therapies using systemic agents may accomplish better responses and should be considered for these patients.32,33 Similarly, when considering TACE, results from our multivariate analysis support the use of sequential procedures over isolated TACE, as this was found to be a protective factor associated with improved survival. Other studies, including a recent phase II/III trial, have found improved outcomes with similar safety patterns for patients receiving TACE procedures in a planned sequential fashion.34,35 An important finding from our analysis relates to the ability to identify patients at risk of PES. Interestingly, in addition to the burden of disease, we found that patients receiving DEB-TACE were less likely to experience PES, when compared with those having conventional TACE. Retrospective studies, prospective randomized trials and a systematic review comparing DEB-TACE with conventional TACE have found at least similar efficacy and improved safety profile in patients treated with DEB-TACE.36–39 Although none of these reports evaluated differences in PES, in this context, our findings would support the use of DEB-TACE whenever possible. Finally, patients experiencing a poor survival after TACE, such as those with MVI, are typically not considered good candidates for this therapy, and current guidelines do not recommend it.6,14 Although selected patients with poor prognostic factors may benefit from TACE,40 in addition to the considerations previously discussed, alternative and evolving liver-directed therapies such as transarterial radioembolization should be considered for this high-risk population, particularly given recent data showing equivalent survival and a lower incidence of PES.41–43

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting our study findings. Given the retrospective nature of our study, some of our findings may be subject to selection bias. Additionally, there is potential for unmeasured confounders that we were unable to adjust for in our analyses. Nonetheless, we did adjust for all statistically significant covariates in the final multivariate analysis. Although our study population was relatively small, this did not seem to hinder our ability to identify PES as a statistically significant factor associated with worse a overall survival, and this is one of the largest cohort studies of its kind, analysing TACE and OS. Our study cohort was restricted to the Veteran population that was predominantly male, thereby potentially limiting the overall generalizability of our study findings, in particular as it relates to female patients and those with other comorbidity profiles. Lastly, the findings observed in this study may be limited to the TACE practice patterns from our centre, including the preferential use of DEB over conventional TACE (including lipiodol infusion).

In conclusion, we found PES to be a common complication in patients with advanced, unresectable HCC. In the setting of other well-established prognostic factors, PES is an early predictor of worse OS for this population of patients. The biological basis of this association may be related to the inflammatory nature of PES, although this needs to be further studied and characterized. DEB-TACE should be the preferred approach whenever possible as it is associated with a decreased risk of PES. Further, for patients at an increased risk of PES, more aggressive strategies (e.g. combined therapies) and/or other evolving liver-directed therapies such as transarterial radioembolization should be considered. Moving forward, PES must be viewed as a critically relevant event for patients with HCC, and future studies should focus on validating these results using standardized definitions that facilitate multi-institutional comparisons.

Acknowledgments

The authors had full access to all of the data in the study and took responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government. The authors would like to thank Diana Castillo for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding sources

This research was supported in part by the by the Office of Rural Health VISN 16 Clinical Systems Program Office, Telehealth and Rural Access Program (N16-P00494). This material is based upon work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, and the Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (CIN13-413).

References

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent trends in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2004;127(5 Suppl. 1):S27–S34. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB. Hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1118–1127. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1001683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Serag HB, Kanwal F. alpha-Fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma surveillance: mend it but do not end it. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:441–443. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poon RT, Fan ST. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection and postoperative outcome. Liver Transpl. 2004;10(2 Suppl. 1):S39–S45. doi: 10.1002/lt.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sangro B. Chemoembolization and radioembolization. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:909–919. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma: an update. Hepatology. 2011;53:1020–1022. doi: 10.1002/hep.24199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrero JA. Multidisciplinary management of hepatocellular carcinoma: where are we today? Semin Liver Dis. 2013;33(Suppl. 1):S3–S10. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1333631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo CM, Ngan H, Tso WK, et al. Randomized controlled trial of transarterial lipiodol chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2002;35:1164–1171. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayasu K, Arii S, Ikai I, et al. Prospective cohort study of transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma in 8510 patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:461–469. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camma C, Schepis F, Orlando A, et al. Transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Radiology. 2002;224:47–54. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2241011262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Bruix J. Systematic review of randomized trials for unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma: chemoembolization improves survival. Hepatology. 2003;37:429–442. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marelli L, Stigliano R, Triantos C, et al. Transarterial therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: which technique is more effective? A systematic review of cohort and randomized studies. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2007;30:6–25. doi: 10.1007/s00270-006-0062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llovet JM, Ducreux M, Lencioni R, et al. EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikai I, Arii S, Ichida T, et al. Report of the 16th follow-up survey of primary liver cancer. Hepatol Res. 2005;32:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2005.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barman PM, Sharma P, Krishnamurthy V, et al. Predictors of mortality in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2821–2825. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura JT, Gamblin TC. Transarterial chemoembolization for primary liver malignancies and colorectal liver metastasis. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2015;24:149–166. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang ZL, Luo J, Chen MS, Li JQ, Shi M. Blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio predicts survival in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:702–709. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinato DJ, Sharma R. An inflammation-based prognostic index predicts survival advantage after transarterial chemoembolization in hepatocellular carcinoma. Transl Res. 2012;160:146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNally ME, Martinez A, Khabiri H, et al. Inflammatory markers are associated with outcome in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma undergoing transarterial chemoembolization. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:923–928. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2639-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pietrosi G, Miraglia R, Luca A, et al. Arterial chemoembolization/embolization and early complications after hepatocellular carcinoma treatment: a safe standardized protocol in selected patients with Child class A and B cirrhosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2009;20:896–902. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, Kulik LM, et al. Chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: comprehensive imaging and survival analysis in a 172-patient cohort. Radiology. 2010;255:955–965. doi: 10.1148/radiol.10091473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JW, Park JH, Han JK, et al. Hepatic tumors: predisposing factors for complications of transcatheter oily chemoembolization. Radiology. 1996;198:33–40. doi: 10.1148/radiology.198.1.8539401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark TW. Complications of hepatic chemoembolization. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2006;23:119–125. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-941442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhand S, Gupta R. Hepatic transcatheter arterial chemoembolization complicated by postembolization syndrome. Semin Intervent Radiol. 2011;28:207–211. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paye F, Farges O, Dahmane M, Vilgrain V, Flejou JF, Belghiti J. Cytolysis following chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Surg. 1999;86:176–180. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.1999.01014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin SW. The current practice of transarterial chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Korean J Radiol. 2009;10:425–434. doi: 10.3348/kjr.2009.10.5.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo D, Demartines N, Clavien PA. Classification of surgical complications: a new proposal with evaluation in a cohort of 6336 patients and results of a survey. Ann Surg. 2004;240:205–213. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000133083.54934.ae. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wigmore SJ, Redhead DN, Thomson BN, et al. Postchemoembolisation syndrome–tumour necrosis or hepatocyte injury? Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1423–1427. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jun CH, Ki HS, Lee HK, et al. Clinical significance and risk factors of postembolization fever in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:284–289. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i2.284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talenfeld AD, Sista AK, Madoff DC. Transarterial therapies for primary liver tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2014;23:323–351. doi: 10.1016/j.soc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho EY, Cozen ML, Shen H, et al. Expanded use of aggressive therapies improves survival in early and intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB. 2014;16:758–767. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Chen H, Wang M, et al. Combination therapy of sorafenib and TACE for unresectable HCC: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e91124. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer T, Kirkwood A, Roughton M, et al. A randomised phase II/III trial of 3-weekly cisplatin-based sequential transarterial chemoembolisation vs embolisation alone for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:1252–1259. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaeger HJ, Mehring UM, Castaneda F, et al. Sequential transarterial chemoembolization for unresectable advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 1996;19:388–396. doi: 10.1007/BF02577625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malagari K, Pomoni M, Spyridopoulos TN, et al. Safety profile of sequential transcatheter chemoembolization with DC Bead: results of 237 hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2011;34:774–785. doi: 10.1007/s00270-010-0044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogl TJ, Lammer J, Lencioni R, et al. Liver, gastrointestinal, and cardiac toxicity in intermediate hepatocellular carcinoma treated with PRECISION TACE with drug-eluting beads: results from the PRECISION V randomized trial. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;197:W562–W570. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golfieri R, Giampalma E, Renzulli M, et al. Randomised controlled trial of doxorubicin-eluting beads vs conventional chemoembolisation for hepatocellular carcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2014;111:255–264. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2014.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Geller D, Espat J, et al. Safety and efficacy of trans arterial chemoembolization with drug-eluting beads in hepatocellular cancer: a systematic review. Hepatogastroenterology. 2012;59:255–260. doi: 10.5754/hge10240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades CS, Hong K, D'Angelo M, Geschwind JF. Safety and efficacy of transarterial chemoembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein thrombosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2005;16:1653–1659. doi: 10.1097/01.RVI.0000182185.47500.7A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lance C, McLennan G, Obuchowski N, et al. Comparative analysis of the safety and efficacy of transcatheter arterial chemoembolization and yttrium-90 radioembolization in patients with unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2011;22:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2011.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreno-Luna LE, Yang JD, Sanchez W, et al. Efficacy and safety of transarterial radioembolization versus chemoembolization in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2013;36:714–723. doi: 10.1007/s00270-012-0481-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seinstra BA, Defreyne L, Lambert B, et al. Transarterial radioembolization versus chemoembolization for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma (TRACE): study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2012;13:144. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-13-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]