Abstract

Eating in the Absence of Hunger (EAH) represents a failure to self-regulate intake leading to overconsumption. Existing research on EAH has come from the clinical setting, limiting our understanding of this behavior. The purpose of this study was to describe the adaptation of the clinical EAH paradigm for preschoolers to the classroom setting and evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of measuring EAH in the classroom. The adapted protocol was implemented in childcare centers in Houston, Texas (N=4) and Phoenix, Arizona (N=2). The protocol was feasible, economical, and time efficient, eliminating previously identified barriers to administering the EAH assessment such as limited resources and the time constraint of delivering the assessment to participants individually. Implementation challenges included difficulty in choosing palatable test snacks that were in compliance with childcare center food regulations and the limited control over the meal that was administered prior to the assessment. The adapted protocol will allow for broader use of the EAH assessment and encourage researchers to incorporate the assessment into longitudinal studies in order to further our understanding of the causes and emergence of EAH.

Keywords: Children, Preschool, Feeding Behavior, Eating, Hunger, Internal Cues

Introduction

Eating in the Absence of Hunger (EAH) significantly contributes to poor dietary habits and overweight and obesity in preschool children (Birch & Deysher, 1985; Birch, Fisher, & Davison, 2003; Fisher & Birch, 2002). EAH reflects a reduced ability to self-regulate energy intake leading to overconsumption of food in the absence of physiologic hunger (Schachter, 1968; Wardle, Guthrie, Sanderson, & Rapoport, 2001). EAH has been linked to increased levels of adiposity and weight gain over time in preschool children (Birch et al., 2003; Hill et al., 2008; Kral et al., 2012; Shunk & Birch, 2004).

The laboratory assessment developed by Fisher and Birch (1999) is the gold standard for assessing EAH. Children consume a standardized meal until they reach a self-determined level of satiety before they are taken to an observation room where they are given ad libitum access to 10 pre-weighed high energy/low nutrient snack foods for ten minutes (Birch et al., 2003; Fisher & Birch, 1999; Hill et al., 2008). Although the EAH paradigm has high measurement sensitivity and internal validity, it is time consuming, costly, and loses ecologic validity as children may behave differently in a lab setting (Birch, 1998; Madowitz et al., 2014; Mallan, Nambiar, Magarey, & Daniels, 2014).

More recently, Pieper et al. adapted the EAH laboratory assessment for use in the classroom setting for preschoolers with lower executive function (Pieper & Laugero, 2013). Similarly, Mallan et al. implemented the assessment in the home setting for four year old children (Mallan et al., 2014). More studies that evaluate and report on adaptations to the laboratory assessment are needed to increase knowledge of EAH and help develop effective, feasible and ecologically valid methods of measuring EAH (Birch et al., 2003; Esposito, Fisher, Mennella, Hoelscher, & Huang, 2009; Faith et al., 2006; Frankel et al., 2012; Schachter, 1968). This manuscript will provide a detailed description of the adaptation of the laboratory EAH paradigm to the classroom setting and explore the implementation, feasibility and acceptability of the adapted assessment.

Methods

Sustainability via Active Garden Education (SAGE) was a physical activity and nutrition garden-based education program for preschool aged children (R21HD073685-01) and was tested in two U.S. cities. Study 1 was conducted in four early childcare education centers (ECECs) in Houston, Texas, and Study 2 was conducted in two ECECs in Phoenix, Arizona. Students ages 3-5 were eligible to participate. All procedures and protocols were approved by the Committee for the Protection of Human Subjects at the University of Houston and the Institutional Review Board at Arizona State University.

Micro-level Environment Measures

Development and Delivery of EAH Assessment

A protocol was developed using previous variations of the EAH paradigm (Birch et al., 2003; Hill et al., 2008; Pieper & Laugero, 2013). The current protocol relied on strong partnerships with the childcare centers and pre-existing resources in the childcare setting. Research assistants participated in a two-hour, in-class training where they learned and practiced administering the adapted protocol.

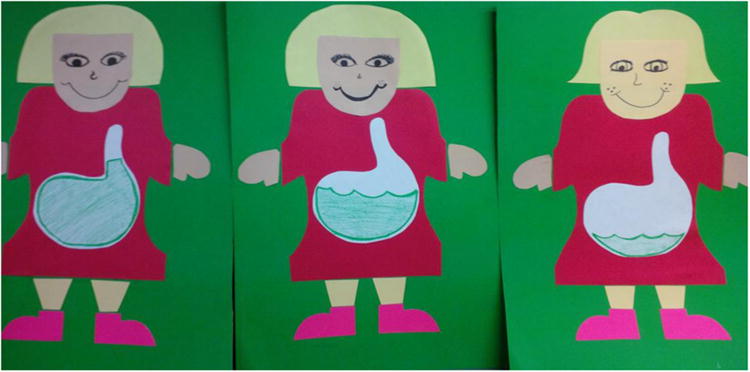

In Study 1, the EAH assessment was scheduled 30 minutes to 1 hour after a center provided lunch or breakfast (Cutting, Fisher, Grimm-Thomas, & Birch, 1999). The children were seated at their regular snack tables in the classroom and were told that they were going to be playing a tasting game. The children were first asked if they had consumed a meal prior to the assessment to verify that they had received lunch or breakfast. Research assistants then introduced the children to the tummy dolls (Figure 1), constructed to reflect an empty stomach, a satisfied stomach and a full stomach (Johnson, 2000).

Figure 1.

Tummy dolls used to guide children in identifying their level of satiety.

The research assistants explained the significance of the tummy dolls and led the class in two practice examples to ensure understanding. The research assistants then asked the children to identify their level of satiety by pointing to the tummy doll that best described their level of hunger or fullness.

Next, children were presented with two pre-weighed in plastic snack bags. One bag contained a salty snack of pretzels (20g, 71 kcals) and the other bag contained a sweet snack of unwrapped M&Ms (28g, 136kcals). After administering the snack bags, research assistants introduced the children to the cartoon “yummy, yucky, and just okay” faces (Figure 2) (Kral et al., 2012). They explained the significance of the faces and led the children in two examples to ensure understanding. The children were instructed to taste one piece of each snack and rate their preference by selecting a yummy, yucky, or just okay face to ensure that the snacks were acceptable and palatable to them.

Figure 2.

The yummy, yucky, and just okay used to indicate the children's preference for the snacks.

The EAH assessment in Study 2 was also scheduled 30 minutes to 1 hour after a school provided lunch or breakfast. The same protocol used in Study 1 was used in Study 2. However, due to center regulations on nutrition and parent concerns regarding the acceptability of the use of pretzels and M&Ms, the snacks in Study 2 were changed. Instead, children received two pre-weighed snack bags of Cheezit crackers (30g, 136.8 kcals) and animal crackers (30g, 150 kcals). After rating their preference, the children were told that they could continue snacking or they could choose to color using a provided coloring sheet and crayons (Pieper & Laugero, 2013).

Snack bags in both studies were re-weighed twice using a food scale and the average of both readings was used to indicate the final weight of the snack bag in grams to the nearest tenth. The pre-assessment weight was subtracted from the post-assessment weight to calculate the grams of snack that had been consumed by each child during the assessment. Kilocalories (kcals) consumed by each participant were calculated using calorie and serving information found on the nutrition label of the snacks. The number of calories per gram was multiplied by the number of grams consumed.

Results

Feasibility and Acceptability

The EAH assessment took 30-45 minutes to complete in the classroom. One research assistant could assess up to six children at once. In contrast, the laboratory and home assessment requires children to schedule individual appointments and takes one and a half to two hours to complete (Birch et al., 2003; Mallan et al., 2014). Adapting the assessment to the classroom substantially decreased the time burden of the assessment and allowed the research team to administer the test to a larger sample of children then would have been feasible using the laboratory assessment.

The classrooms in both studies had snack tables where the children could be seated during the assessment. The children were comfortable in this setting as they consume their daily snacks at these tables. This may have reduced feelings of self-consciousness that may arise in the laboratory setting if the child detects that they are being observed (Birch et al., 2003; Madowitz et al., 2014).

The adapted EAH assessment also reduced the need for extensive food resources as schools provided the meal prior to the assessment and a smaller range of snacks was used. In the laboratory and home assessment, a pre-weighed meal is provided at the cost of the research team and ten snacks including popcorn (15g), potato chips (58g), pretzels (39g), nuts (44g), fig bars (51g), chocolate chip cookies (66g), fruit-chew candy (66g), chocolate bars (66g), ice cream (168g) and frozen yogurt (168g) are used (Birch et al., 2003; Harris, Mallan, Nambiar, & Daniels, 2014; Mallan et al., 2014). Providing these ten snacks for a sizeable sample can be costly. In Study 1, children had two options, Pretzels (20g) and M&Ms (28g), and in Study 2, Cheezit Crackers (30g) and Animal crackers (30g). The adapted snacks were acceptable to the children with almost all participants (96%) indicating that at least one of the snacks were “yummy.”

In Study 1, the average number of kcals eaten in the absence of hunger was 80.63 kcals (SD=60.54). In Study 2, the average number of kcals eaten in the absence of hunger was 54.62 kcals (SD=54.78).

Challenges

Selecting the snack foods to be used in the assessment was an initial challenge. In Study 1, the children had high preference for M&Ms and moderate preference for pretzels; however, these snacks were not acceptable among parents and childcare centers. All centers were “peanut free zones” due to allergies; most centers and parents did not allow candy of any kind; and some centers had policies against serving foods that were classified as choking hazards such as popcorn and pretzels. The research team relied on current literature on EAH assessments and guidance from center directors to find appropriate snacks that complied with national childcare food regulations, individual centers'food policies, and were widely liked by most children.

During the observation period in Study 1, children had access to toys located in the classroom. However, allowing the students to engage in free play in any area of the room was burdensome for research assistants who were simultaneously recording the behavior of multiple participants. In Study 2, we implemented the use of a coloring sheet and crayons during the observation period to allow research assistants to more easily observe all participants (Pieper & Laugero, 2013).

Relying on school or parent resources to provide the meal prior to the assessment reduced the financial and resource burden of the research team, but our limited control over this meal presented the biggest challenge to adapting the assessment. Because assessments were scheduled following breakfast or lunchtime at the center, we were able to ensure that all children had consumed a meal before the assessment, but we were unable to verify that the children ate the meal to the point of satiety, increasing their chances of participating in the study while still feeling hungry. In fact, 50% of children in Study 1 indicated that they were still hungry prior to the assessment, and 37% in Study 2 indicated that they were still hungry prior to the assessment. There were also a few children that ate all of the snack foods presented, indicating that some children may have been eating in response to hunger. These findings are particularly detrimental to the results of the assessment as children who indicate that they are still hungry prior to the assessment are excluded from all analyses, as the child is not eating in the absence of hunger, but is eating in response to physiologic hunger.

Discussion

The adapted EAH assessment used in the SAGE study was a feasible ecological method and eliminated previously identified barriers to administering the laboratory EAH assessment such as limited financial and human resources and lack of facilities such as observation rooms or kitchen space for meal preparation. The adapted EAH assessment also eliminated time burdens associated with the laboratory EAH assessment. The significant time and financial costs associated with the laboratory assessment can discourage researchers from including measures of EAH in longitudinal studies (Shomaker et al., 2013). Conducting the assessment in a group or classroom setting is a time sensitive solution that may encourage investigators to incorporate the EAH assessment in longitudinal studies. Time and resources saved with the classroom adaptation may make it more feasible for investigators to simultaneously measure other factors that impact EAH, such as diet or parent feeding styles (Lansigan, Emond, & Gilbert-Diamond, 2015).

Future Applications and Recommendations

Future applications of the EAH should collaborate with participating ECECs in order to administer the meal prior to the EAH assessment. Having observers present to oversee the meal in the school can help ensure that children have the opportunity to consume the meal to the point of satiety prior to the assessment. Future applications of the EAH assessment in the classroom setting should also include a measure of the social environment. Eating is a social occasion for young children and parents, caregivers, and other peers may easily influence them (Birch, 1998; Birch et al., 2003; Cutting et al., 1999). Teaching the concept of hunger to children using games, pretend play and props, or other established methods, before administering the test can help improve measures of satiety in future applications. In both studies children indicated that they were still hungry even after participating in a mealtime prior to the assessment. Perhaps 3-5 year old children may not fully understand the concept of hunger (Piaget, 1974). In order to examine the validity of the adapted classroom protocol, future applications should simultaneously use a validated EAH questionnaire to compare results from the adapted EAH classroom protocol with a validated EAH questionnaire.

Conclusion

As more researchers have begun to adapt the laboratory assessment to other settings such as the home or classroom it is important to evaluate and report these adaptations in an effort to establish ecologically valid methods of assessing EAH in preschool aged children (Harris et al., 2014; Mallan et al., 2014; Pieper & Laugero, 2013). Despite several limitations, we were able to adapt the laboratory EAH assessment to the classroom setting to create a time and cost effective assessment. The feasibility and acceptability of the adapted protocol are promising for future adaptations of measuring EAH in the classroom setting.

Highlights.

The adapted protocol is time efficient and can be delivered to groups of children.

Partnering with centers made the adapted protocol feasible and economical.

Improving the ecologic validity will allow for broader use of the EAH assessment.

Acknowledgments

This work was completed as part of Sustainability via Active Garden Education (R21HD073685-01), awarded to Dr. Rebecca Lee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Birch LL. Development of food acceptance patterns in the first years of life. Proc Nutr Soc. 1998;57(4):617–624. doi: 10.1079/pns19980090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Deysher M. Conditioned and unconditioned caloriccompensation: evidence for self-regulation of food intake in young children. Learning and Motivation. 1985;16:341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: maternal use ofrestrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am JClin Nutr. 2003;78(2):215–220. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting TM, Fisher JO, Grimm-Thomas K, Birch LL. Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers' dietarydisinhibition. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(4):608–613. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito L, Fisher JO, Mennella JA, Hoelscher DM, Huang TT. Developmental perspectives on nutrition and obesity from gestation to adolescence. Prev Chronic Dis. 2009;6(3):A94. doi:A93[pii] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Eating in the absence of hunger: a genetic marker for childhood obesity in prepubertal boys? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(1):131–138. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.16. doi:14/1/131[pii]10.1038/oby.2006.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Birch LL. Restricting access to palatable foods affects children's behavioral response, food selection, and intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999;69(6):1264–1272. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.6.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Birch LL. Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):226–231. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel LA, Hughes SO, O'Connor TM, Power TG, Fisher JO, Hazen NL. Parental Influences on Children's Self-Regulation of Energy Intake: Insights from Developmental Literature on Emotion Regulation. J Obes. 2012;2012:327259. doi: 10.1155/2012/327259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris H, Mallan KM, Nambiar S, Daniels LA. The relationship between controlling feeding practices and boys' and girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Eat Behav. 2014;15(4):519–522. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.07.003. doi:S1471-0153(14)00097-X[pii]10.1016/j.eatbeh.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C, Llewellyn CH, Saxton J, Webber L, Semmler C, Carnell S. Adiposity and ‘eating in the absence of hunger’ in children. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(10):1499–1505. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.113. doi:ijo2008113[pii]10.1038/ijo.2008.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Improving Preschoolers' self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1429–1435. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kral TV, Allison DB, Birch LL, Stallings VA, Moore RH, Faith MS. Caloric compensation and eating in the absence of hunger in 5- to 12-y-old weight-discordant siblings. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;96(3):574–583. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.037952. doi:ajcn.112.037952[pii]10.3945/ajcn.112.037952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lansigan RK, Emond JA, Gilbert-Diamond D. Understanding Eating in the Absence of Hunger Among Young Children: A systematic review of existing studies. Appetite. 2015;85:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2014.10.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madowitz J, Liang J, Peterson CB, Rydell S, Zucker NL, Tanofsky-Kraff M. Concurrent and convergent validity of the eating in the absence of hunger questionnaire and behavioral paradigm in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2014;47(3):287–295. doi: 10.1002/eat.22213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallan KM, Nambiar S, Magarey AM, Daniels LA. Satiety responsiveness in toddlerhood predicts energy intake and weight status at four years of age. Appetite. 2014;74:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.001. doi:S0195-6663(13)00476-5[pii]10.1016/j.appet.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piaget J. Main Trends in Psychology. Harper & Row; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Pieper JR, Laugero KD. Preschool children with lower executive function may be more vulnerable to emotional-based eating in the absence of hunger. Appetite. 2013;62:103–109. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.020. doi:S0195-6663(12)00472-2 [pii]10.1016/j.appet.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachter S. Obesity and eating. Internal and external cues differentially affect the eating behavior of obese and normal subjects. Science. 1968;161(3843):751–756. doi: 10.1126/science.161.3843.751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shomaker, Tanofsky-Kraff M, Mooreville M, Reina SA, Courville AB, Field SE. Links of adolescent- and parent-reported eating in the absence of hunger with observed eating in the absence of hunger. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2013;21(6):1243–1250. doi: 10.1002/oby.20218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shunk JA, Birch LL. Girls at risk for overweight at age 5 are at risk for dietary restraint, disinhibited overeating, weight concerns, and greater weight gain from 5 to 9 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(7):1120–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.04.031S0002822304005760[pii]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of Children's Eating Behavior Questionnaire. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):963–970. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]