Abstract

Objective

Web-based brief alcohol intervention (WBI) programs have efficacy in a wide range of college students and have been widely disseminated to universities to address heavy alcohol use. In the majority of efficacy studies, web-based research assessments were conducted before the intervention. Web-based research assessments may elicit reactivity, which could inflate estimates of WBI efficacy. The current study tested whether web-based research assessments conducted in combination with a WBI had additive effects on alcohol use outcomes, compared to a WBI only.

Methods

Undergraduate students (n= 856) from universities in the United States and Canada participated in this online study. Eligible individuals were randomized to complete 1) research assessments + WBI or 2) WBI-only. Alcohol consumption, alcohol-related problems, and protective behaviors were assessed at one-month follow up.

Results

Multiple regression using 20 multiply imputed datasets indicated there were no significant differences at follow up in alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, or protective behaviors used when controlling for variables with theoretical and statistical relevance. A repeated measures analysis of covariance revealed a significant decrease in peak estimated blood alcohol concentration in both groups, but no differential effects by randomized group. There were no significant moderating effects from gender, hazardous alcohol use, or motivation to change drinking.

Conclusions

Web-based research assessments combined with a web-based alcohol intervention did not inflate estimates of intervention efficacy when measured within-subjects. Our findings suggest universities may be observing intervention effects similar to those cited in efficacy studies, although effectiveness trials are needed.

Keywords: web-based intervention, alcohol, assessment reactivity, methodology, college students

1. Introduction

Unhealthy alcohol use is prevalent among college students (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2013; Wechsler & Nelson, 2008). Commercially available web-based brief intervention (WBI) programs have been developed to address this problem, have demonstrated efficacy in a range of student groups (Khadjesari, Murray, Hewitt, Hartley, & Godfrey, 2011; White et al., 2010), and have been widely disseminated to universities (San Diego State University Research Foundation, 2009).

Typically, efficacy studies assess alcohol use at baseline, randomize participants to a WBI condition or assessment-only control condition, and then compare 1) within-groups change in alcohol use from baseline to follow up, and 2) alcohol use between groups at follow up. However, conducting baseline research assessments (RAs) may present a methodological issue when attempting to establish WBI efficacy. Research has demonstrated that simply asking participants about their alcohol use can lead to decreases in alcohol use and alcohol-related problems (Clifford & Davis, 2012; McCambridge & Kypri, 2011; Schrimsher & Filtz, 2011). Reactivity to baseline RAs may inflate effect size estimates when efficacy is measured within-subjects.

Assessment reactivity has been hypothesized to occur because assessments draw attention to the targeted behaviors and prompt participants to think about their behavior and reasons to change (Clifford & Maisto, 2000). Researchers have suggested that RAs contain similar elements to brief interventions (BI) themselves: identifying risk behavior, providing a menu of options for change, and highlighting personal responsibility for the behavior (Clifford & Davis, 2012; Schrimsher & Filtz, 2011).

Assessment reactivity is a double- edged sword, because it can be a confounder in intervention efficacy trials, but also used as a valuable therapeutic tool. WBI programs have assessments built into the intervention and these assessments likely contribute to intervention effectiveness. However, reactivity to baseline RAs conducted for research purposes could cloud the detection of accurate treatment effect sizes.

Experimental tests of reactivity in college student samples have found that when RAs were administered alone (not combined with an intervention) significant reactivity effects were present, with small to moderate Cohen's d effect sizes of .23 to .37 (Kypri, Langley, Saunders, & Cashell-Smith, 2007; McCambridge & Day, 2008; Walters, Vader, Harris, & Jouriles, 2009). Reactivity has also been found when a live, in-person Timeline Follow Back (TLFB) assessment was conducted in combination with a live BI. Participants who received a BI plus TLFB significantly reduced drinking and related problems at one month follow up compared to the BI-only group (Cohen's d effect sizes .32 to. 52; Carey, Carey, Maisto, & Henson, 2006).

While the Carey et al (2006) study administered the RAs and BI in-person, the majority of WBI studies administer RAs online. It is currently unknown whether assessment reactivity occurs to web-based RAs when administered in combination with a WBI. This research question is important to consider, as WBI programs have been widely disseminated to universities for use as general services for university students, where they do not include RAs. The purpose of the current study was to experimentally test whether assessment reactivity occurs when web-based RAs are administered in combination with a WBI, compared to WBI-only condition. We hypothesized that there would be significant assessment reactivity effects in the RAs+WBI group as evidenced by lower alcohol use, alcohol-related problems, and higher use of protective behaviors related to alcohol consumption at follow up compared with the WBI-only group.

2. Material and Methods

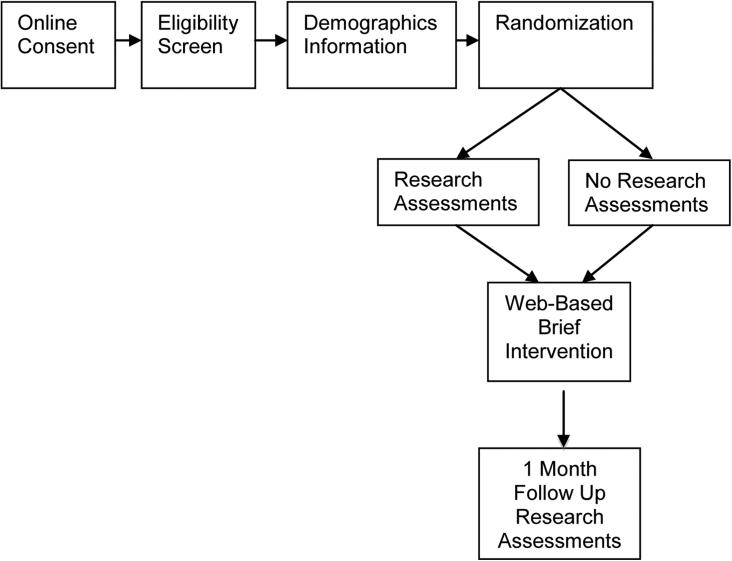

Figure 1 presents the study design. The study was conducted entirely online, allowing students to participate at any time from any computer or mobile device with Internet access. Following approval from the Institutional Review Board, undergraduate students attending universities in the United States or Canada were recruited to participate.

Figure 1.

Study Design

2.1 Recruitment and Procedure

Recruitment was conducted during the Spring 2013, Summer 2013, Fall 2013, and Spring 2014 university semesters by announcing the study on social media sites Facebook and Twitter and by posting flyers at the host campus (see Fazzino, Rose, Pollack, & Helzer, 2015 for a detailed description of our recruitment methods). The recruitment announcements directed interested individuals to the study website where they could read information about the study and provide informed consent. The study purpose was presented in the consent form as a test of a new web-based alcohol assessment and feedback program for university students. Participants were blinded to the study hypothesis, because their awareness about the hypothesis may have altered their behavior during the investigation.

After consenting, participants completed an eligibility screening questionnaire. Eligibility criteria consisted of the following: 1) current undergraduate student, 2) attending college/university in the U.S. or Canada, 3) self-reported alcohol consumption in excess of NIAAA guidelines for low-risk drinking: 4[5] or more drinks for women [men] at least one time in the past month, and 4) age 18-26. On the screening form, beer, wine, mixed drinks, and shots were asked separately. The amount of alcohol considered one standard drink was listed in both ounces and milliliters.

Eligible individuals provided demographic information and then were randomized to the RAs+WBI condition or WBI-only condition. In considering gender differences in rates of alcohol consumption and related consequences among students (Kelly-Weeder, 2008, O'Malley & Johnston, 2002; Wechsler, Dowdall, Davenport, & Rimm, 1995), the randomization procedure was blocked on gender.

One month following WBI completion, all participants were emailed a request to complete follow up RAs online. A one-month follow up period to test for assessment reactivity effects was selected because it was important to observe any potential reactivity effects at their strongest and Carey et al. (2006) found diminution of reactivity effects three months post-intervention. Also, effects from WBIs have been shown to be most prominent in the first month post-WBI (Chiauzzi, Green, Lord, Thum, & Goldstein, 2010; Hester, Delaney, & Campbell, 2012).

Incentives were provided for participating and were structured to encourage early study enrollment. For signing up for the study and completing the WBI, participants were entered into up to three drawings for iPad minis; the earlier participants completed the WBI relative to overall study recruitment, the more drawings they were entered into. For completing the follow up RAs, participants were entered into one of four drawings for a $500 Amazon.com gift card.

2.2 Assessments

Research Assessments

RAs were chosen to reflect those commonly used in WBI studies to allow for generalizability of the study findings. The majority of WBI efficacy studies reported using 3-7 questionnaires at baseline, with RAs time duration of 15 – 45 minutes (Mean = 30 minutes) to complete (Hustad, Barnett, Borsari, & Jackson, 2010; Lee et al., 2014; Lewis et al., 2014; Paschall, Antin, Ringwalt, & Saltz, 2011) and took 25-100% as long as the actual WBI. The RAs in the current study consisted of 3 questionnaires and were expected to take approximately 10 minutes, or half as long as the WBI. Participants in the RA+WBI condition completed RAs at baseline and all participants across both conditions completed the same RAs at one month follow up

The Daily Drinking Calendar (DDC) is a calendar measure of frequency and quantity of alcohol consumption that asks participants to identify the number of drinks they consumed each day during a specified period in time, modified from the Daily Drinking Questionnaire (Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). It has established test-retest reliability and concurrent validity when compared with the paper version (Miller et al., 2002), the TLFB, and the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Pedersen, Grow, Duncan, Neighbors, & Larimer, 2012; Rueger, Trela, Palmeri, & King, 2012). Outcome variables derived from drinking calendar data consisted of: 1) total number of drinks consumed in the past month (TOT), 2) peak estimated blood alcohol content in the past month (PBAC), derived from the formula from Matthews and Miller (1979) and 3) the number of times participants drank past NIAAA guidelines in the past month (DP).

The Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index (RAPI; White & Labouvie, 1989) is a 23-item tool that measures the number of alcohol-related consequences experienced in college students and has good internal consistency (Borsari & Carey, 2000; Neal & Carey, 2004; H. R. White & Labouvie, 1989) and strong test-retest reliability in college student samples (Miller et al., 2002). The RAPI can be scored as a count of the number of times participants reported experiencing each alcohol-related problem in the past month. Total RAPI score was used as an outcome variable in analyses and items were scored as 0 for response option “none”, 1 for “1-2 times”, 2 for “3-4 times”, and 3 for “5 or more times.” Thus, scores could range from 0-69.

The Protective Behavioral Strategies Scale (PBSS) is a fifteen item questionnaire that evaluates self-control behaviors related to alcohol consumption (Martens et al., 2005). Researchers have established concurrent validity with alcohol use measures (Pearson, Kite, & Henson, 2012). PBSS score is calculated by summing all items; thus total score can range from 15-75. PBSS score was used as an outcome variable in analyses.

Web-Based Brief Intervention Assessments

In addition to the RAs, the WBI itself collected alcohol use information from participants. The WBI administered the AUDIT (Babor, de la Fuente, Saunders, & Grant, 1992; Saunders, Aasland, Babor, & de la Fuente, 1993) and collected the following information: the highest number of drinks consumed in the past month in a single day, number of hours drank during the largest drinking episode, weight, Greek membership, student athlete status (yes/no), and whether students reside on or off campus. Also, at the end of the WBI, the WBI asked participants to rate how important it was for them to change their drinking and how confident they were that they could change their drinking, each assessed on a separate 10-point scale from 0-9. Single-item ratings of importance and confidence have been shown to predict change in alcohol use following a BI (Bertholet, Gaume, Faouzi, Gmel, & Daeppen, 2012).

2.3 Web-Based Brief Intervention Program

The WBI used for the current study was the Electronic Check Up to Go (ECHUG), a commercially available program that has demonstrated efficacy with a wide range of college students (Hustad et al., 2010; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, & Jouriles, 2009; Doumas & Andersen, 2009; Doumas, Haustveit, & Coll, 2010). ECHUG collects information about student drinking and immediately presents a personalized feedback report. The program takes about 20 minutes to complete.

2.4 Statistical Process for Evaluating Assessment Reactivity

2.4.1 Analytic Models

All participants who completed the WBI were included in the analyses. However, not all participants completed the follow up assessment and we considered the missing data to be missing at random (MAR) (Rubin, 1976) because we expected there was some relationship between alcohol use and other variables in the analysis models that existed in relation to the missing data. Therefore, we used multiple imputation, a robust statistical estimation technique that produces unbiased parameter estimates with MAR data (Enders, 2010) to cope with the missing data.

Multiple regression using 20 multiply imputed datasets (Graham, Olchowski, & Gilreath, 2007; Enders, 2010) was used to determine whether the RAs+WBI and the WBI-only groups significantly differed on three measures of alcohol use (TOT, PBAC, DP), RAPI score, and PBSS score at follow up, while controlling for statistically and theoretically important confounding variables. Analyses were conducted with each dependent variable in a separate regression model. Moderating effects of gender, AUDIT hazardous alcohol use (score of 8 or more; Saunders et al., 1993), confidence rating, and importance ratings were evaluated for each dependent variable in separate analyses.

Based on evaluations of multiple regression assumptions for the models, multiple regression with least squares was used for the normally distributed continuous PBSS score. Multiple regression with generalized linear models (GLM) specifying a negative binomial distribution was used for non-normally distributed count variables TOT, DP, and RAPI, because GLM allows for regression with variables that have non-normally distributed error variances (Nelder & Wedderburn, 1972). Coefficients from a negative binomial regression analysis are presented as the mean log count of the dependent variable. Because PBAC was a positively skewed continuous variable, a square root transformation was applied before using a least squares regression model.

2.4.2 Choosing Potential Confounding Variables

To choose potential confounding variables for our models, we first created a list of variables that have been shown in the literature to influence or be related to the outcome variables of interest. The variable list consisted of the following: membership in a Greek fraternity/sorority, residence on or off campus, student athlete status (yes/no), attending school in the U.S. or Canada, age, AUDIT dichotomous designation of hazardous alcohol use (score of 8 or more; Saunders et al., 1993), highest number of drinks consumed in the past month in a single day at baseline, year in school, importance in changing drinking as rated at the end of the WBI, confidence in changing drinking as rated at the end of the WBI, and the semester in which participants enrolled (Fall 2013, Summer 2013, Spring 2014).

We next evaluated the individual influence of each of these variables in each of the five main models. We first ran each model with only the predictor (randomization group variable) and the outcome variable. Then, we systematically ran individual regression models with each potential confounding variable and randomization variable for each of the 5 outcomes to evaluate whether and how the beta and/or p values of the randomization variable changed in a meaningful way with regard to the outcome variable and whether it predicted the outcome. The determination of whether the variable changed the beta in a meaningful way was made by the researcher based on the magnitude of change in relation to the scale of each outcome variable. For example, a beta change of 0.03 was not considered meaningful for the PBSS outcome, however it was considered meaningful for the PBAC variable. In the interest of presenting the most parsimonious models, the final model for each dependent variable included only potential confounding variables that influenced the model. Gender was not evaluated as a confounding variable, because the randomization procedure was blocked on gender.

2.4.3 Validation of WBI Efficacy

We calculated PBAC at baseline from the screening data we collected on all participants before they were enrolled in the study. We chose to use this data instead of the data from the WBI, because we asked about beer, wine, shots, and mixed drinks separately (the WBI combined shots and mixed drinks). This information was assessed the same way in the follow up assessment. Change in PBAC from baseline to follow up was modeled to determine whether the effect size of the WBI was consistent with the literature using a repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) with randomization group, baseline hazardous alcohol use, and importance in changing drinking as covariates.

All analyses were conducted using R statistical software (R Development Core Team, 2012) with the Amelia() package (Honaker, King, & Blackwell, 2011) for data imputation and the Zelig () package (Imai, King, & Lau, 2007, 2008) for multiple regression with least squares and GLM and for pooling regression results.

2.4.4 Power Calculation

A priori power analysis using G*POWER (Faul, 2010) and assuming standard values for Type I error (.05) and Type II error (.95), 80% power, and effect size of .33 (Kypri et al., 2007; McCambridge & Day, 2008; McCambridge & Kypri, 2011; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, et al., 2009) indicated that 176 participants would be needed for each study group. Considering participant attrition at both the WBI (10%) and follow up (20%), a total of 490 randomized participants were required to achieve adequate statistical power to detect small effect sizes.

3. Results

3.1 Recruitment

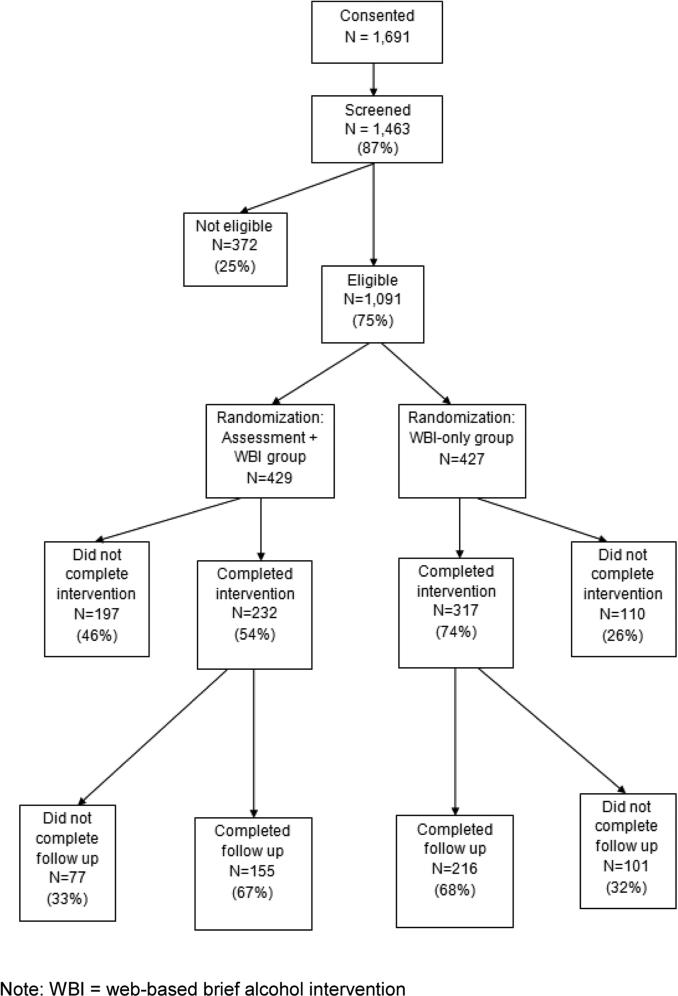

Figure 2 presents a flowchart of recruitment and retention in the study. Overall, the percentage of randomized participants (from both groups) who completed the WBI was 64%. The WBI took a median of 16.1 minutes (mean= 19.1, SD = 11.1) to complete. The RAs took a median of 11 minutes (mean = 17.1, SD = 15.6) to complete.

Figure 2.

Recruitment and Retention

Follow Up Completion Rates

Of those who completed the WBI, 371 (68%) completed the follow up RAs and an additional 30 participants (5%) provided complete alcohol data in the 30-day drinking calendar, but did not complete the RAPI and PBSS positioned at the end of the questionnaire. There was no differential completion rate by group (67% vs 68%).

3.2 Descriptive Statistics

Table 1 provides demographic characteristics and baseline alcohol use information for the final sample. Participants were from 30 U.S. states and four Canadian provinces. Locations that garnered the most participants were Vermont (n=328), Ontario (n=109), New York (n=46), and Quebec (n=41).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics

| Demographic Characteristic | RAs+WBI group (n = 429) | WBI-only group (n = 427) |

|---|---|---|

| Age; mean (standard deviation) | 20.0 (1.27) | 20.0 (1.18) |

| Gender (% female) | 296 (69%) | 297 (70%) |

| Year in School: | ||

| Freshmen | 50 (12%) | 62 (15%) |

| Sophomore | 121 (28%) | 123 (29%) |

| Junior | 152 (35%) | 143 (33%) |

| Senior | 104 (24%) | 98 (23%) |

| Not provided | 2 | 1 |

| Country in which participants were attending college | ||

| U.S. | 346 (81%) | 340 (80%) |

| Canada | 83 (19%) | 87 (20%) |

| Host University Students | 111 (26%) | 156 (37%) |

| Race (% Caucasian, non-Hispanic) | 349 (81%) | 356 (83%) |

| Source of Recruitment | ||

| Flyer | 20 (4.5%) | 11 (2.5%) |

| 367 (86%) | 379 (89%) | |

| 4 (1%) | 2 (0.5%) | |

| Friend | 14 (3%) | 7 (2%) |

| University news email | 20 (5%) | 22 (5%) |

| Health/counseling center | 2 (0.5%) | 5 (1%) |

| Not specified | 2 (0.5%) | 1 |

| Highest number of drinks consumed in the past month in a single day | ||

| Mean (SD) | 10.4 (6.7) | 10.2 (6.9) |

| Median | 8 | 8 |

3.3 Baseline Differences and Descriptive Statistics for the Outcome Measures

There were no significant differences at baseline between the two randomized groups on any demographic variables (all p values > .05). In both groups, participants who did not complete the WBI had significantly higher baseline alcohol use compared to participants in each respective group who completed the WBI (RA+WBI: t(420) = 2.38, p = 0.01; WBI only: t(424) = 5.56, p =.002). However, participants from each randomized group who completed the WBI were not significantly different from each other on baseline alcohol consumption (t(406) = 0.83, p = 0.41).

Descriptive statistics for the outcome variables, moderating variables, and potential confounding variables are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for outcome, moderating, and potentially confounding variables.

| Outcome Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean or median | Standard Deviation or Interquartile Rangec | |

| Total number of drinks consumed in the past month (TOT)b | 34.00 | 48 |

| Peak estimated blood alcohol contentb | 0.11 | 0.13 |

| Number of times drank past NIAAA guidelinesb | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Alcohol-related problems (RAPI)b | 3.00 | 6.00 |

| Protective behaviors used (PBSS)a | 45.00 | 11.50 |

| Moderating Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean/ % endorsed | Standard deviation | |

| Hazardous alcohol use (AUDITd score 8+) | 54% | - |

| Gender (% female) | 69% | - |

| Importance rating | 2.72 | 2.09 |

| Confidence rating | 8.52 | 1.97 |

| Potential Confounding Variables | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mean/ % endorsed | Standard deviation | |

| Fraternity/sorority membership | 10% | - |

| Residence on/off campus (% on campus) | 41% | - |

| College athlete | 13% | - |

| U.S./Canadian student (% U.S.) | 80% | - |

| Year in school: | ||

| Freshmen | 12% | - |

| Sophomore | 28% | - |

| Junior | 35% | - |

| Senior | 24% | - |

| Spring 2013 enrollment | 21% | - |

| Summer 2013 enrollment | 6% | - |

| Fall 2013 study enrollment | 52% | - |

| Spring 2014 enrollment | 21% | - |

| Highest number of drinks in past montha | 10.3 | 6.8 |

Mean

Median

Standard deviations correspond to means and interquartile ranges correspond to medians.

AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test

3.4 Multiple Regression with Multiply Imputed Datasets

Results of the multiple regression analysis using multiply imputed datasets revealed that randomization group did not significantly predict the total number of drinks consumed in the past month (TOT), while controlling for baseline total number of drinks consumed in a single day in the past month, hazardous alcohol use (as defined by the AUDIT), athletic status, summer enrollment, and importance in changing drinking (Table 3).

Table 3.

Main effect of randomization assignment on alcohol use outcomes

| DV: Total number of drinks in the past month (TOT) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log diff a | SE | p | 95%CI (low, high) | |

| Intercept | 2.99 | 0.09 | .001 | (2.81, 3.18) |

| Randomization groupb | 0.04 | 0.10 | .69 | (−0.15, 0.22) |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.74 | 0.11 | .001 | (0.53, 0.95) |

| Baseline highest drinks | 0.05 | 0.01 | .001 | (0.04, 0.06) |

| Importance rating | −0.02 | 0.02 | .40 | (−0.06, 0.02) |

| Athlete (yes/no) | −0.26 | 0.13 | .05 | (−0.53, −0.001) |

| Summer enrollment (yes/no) | −0.25 | 0.23 | .02 | (−0.97, −0.08) |

| DV: Peak estimated blood alcohol content (PBAC) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log diff a | SE | p | 95%CI (low, high) | |

| Intercept | 0.24 | 0.02 | .001 | (0.20, 0.27) |

| Randomization groupb | 0.01 | 0.01 | .84 | (−0.03, 0.03) |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.12 | 0.02 | .001 | (0.08, 0.15) |

| Baseline highest drinks | 0.005 | 0.002 | .001 | (0.002, 0.009) |

| Importance rating | −0.008 | 0.004 | .03 | (−0.15, −0.001) |

| Athlete (yes/no) | −0.04 | 0.02 | .08 | (−0.08, 0.01) |

| Summer enrollment (yes/no) | −0.03 | 0.04 | .43 | (−0.11, 0.04) |

| DV: Number of days drank past NIAAA guidelines |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| log diff a | SE | p | 95%CI (low, high) | |

| Intercept | 0.07 | 0.15 | .61 | (−0.21, 0.35) |

| Randomization groupb | 0.001 | 0.13 | .99 | (−0.26, 0.26) |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.95 | 0.16 | .001 | (0.64, 1.27) |

| Baseline highest drinks | 0.04 | 0.01 | .001 | (0.03, 0.06) |

| Importance rating | −0.003 | 0.03 | .91 | (−0.06, 0.06) |

| Athlete (yes/no) | −0.27 | 0.18 | .14 | (−0.63, 0.09) |

| Summer enrollment (yes/no) | −0.80 | 0.34 | .02 | (−1.47, −0.13) |

Note. DV: dependent variable; SE: standard error; p: p-value; CI: confidence interval.

Negative binomial regression coefficients are presented as the mean difference in log count.

Randomization group coded 0 for control group and 1 for experimental group.

Results of the multiple regression analysis revealed that randomization group did not significantly predict peak blood alcohol concentration in the past month (PBAC), while controlling for baseline total number of drinks consumed in a single day in the past month, hazardous alcohol use, athletic status, summer enrollment, and importance in changing drinking (Table 3). Participants in the experimental group had an estimated .0001 higher PBAC in the past month compared to control group.

Multiple regression analyses also indicated that randomization group did not significantly predict the number of days in which participants drank past NIAAA guidelines in the past month (DP) (Table 3), the number of times participants experienced alcohol-related problems in the past month (RAPI score), or the number of protective behaviors used in the past month (PBSS score) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Main effect of randomization assignment on alcohol-related problems and protective behaviors related to alcohol consumption

| DV: Rutgers Alcohol Problem Index score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | 95%CI (low, high) | |

| Intercept | 1.42 | 0.16 | .01 | (1.11, 1.74) |

| Randomization groupa | −0.02 | 0.13 | .88 | (−0.28, 0.24) |

| Hazardous drinking | 0.41 | 0.14 | .003 | (0.14, 0.68) |

| Baseline highest drinks | 0.01 | 0.01 | .32 | (−0.01, 0.03) |

| Spring 2013 Enrollment (yes/no) | −0.33 | 0.13 | .01 | (−0.59, −0.07) |

| DV: Protective Behaviors Strategies Scale score |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | SE | p | 95%CI (low, high) | |

| Intercept | 45.37 | 2.78 | .001 | (39.91, 50.82) |

| Randomization groupa | 0.23 | 1.25 | .85 | (−2.21, 2.68) |

| Hazardous drinking | −4.75 | 1.28 | .002 | (−7.25, −2.24) |

| Baseline highest drinks | −0.15 | 0.10 | .14 | (−0.36, 0.05) |

| Importance rating | 0.56 | 0.30 | .07 | (−0.04, 1.15) |

| Confidence rating | 0.43 | 0.29 | .14 | (−0.14, 1.01) |

| Spring 2014 enrollment (yes/no) | 0.83 | 1.36 | .54 | (−1.84, 3.49) |

| U.S./Canadian studentb | −4.44 | 1.59 | .01 | (−7.56, −1.32) |

Note. DV: dependent variable; SE: standard error; p: p-value; CI: confidence interval.

Randomization group coded 0 for control group and 1 for experimental group.

U.S. student used as the reference category.

3.5 Moderation Analyses

Although the main analyses found no significant differences in outcomes, it was plausible that reactivity may have been present at some levels of the aforementioned variables, but not for others (for example, for females but not males). For this reason, the moderating effects of each variable were examined while controlling for the same potential confounding variables that were included in the main models for each outcome. Analyses indicated that none of the variables significantly moderated the relationship between the outcome and predictor variables.

Specifically, hazardous alcohol use did not significantly moderate the relationship between randomization group and TOT (mean difference in log count= −0.12, CI= −0.51, 0.28, p = .57), PBAC (b = −0.001, CI = −0.059, 0.057, p = .97), DP (mean difference in log count = −0.20, CI = −0.80, 0.39, p = .51), RAPI score (mean difference in log count = −0.44, CI = −0.95, 0.07, p = .10), or PBSS score (b= 2.45, CI = −2.15, 7.06, p = .30) after controlling for potential confounding variables.

Gender did not significantly moderate the relationship between randomization group and TOT (mean difference in log count = −0.27, CI = −0.64, 0.11, p = .16), PBAC (b = −0.02, CI = −0.08, 0.04, p = .60), DP (mean difference in log count = −0.22, CI = −0.72, 0.28, p = .40), RAPI score (mean difference in log count = −0.07, CI = −0.59, 0.46, p = .80), or PBSS score (b= −4.08, CI = −8.87, 0.72, p = .10) after controlling for potential confounding variables.

Importance rating did not significantly moderate the relationship between randomization group and TOT (mean difference in log count = 0.04, CI= −0.10, 0.02, p=.37), PBAC (b = 0.003, CI = −0.010, 0.017, p = .63), DP (mean difference in log count = 0.02, CI = −0.10, 0.14, p = .73), RAPI score (mean difference in log count = −0.06, CI = −0.17, 0.06, p = .34), or PBSS score (b= 0.20, CI= −0.89, 1.29, p = .71) after controlling for potential confounding variables.

Finally, confidence rating did not significantly moderate the relationship between randomization group and TOT (mean difference in log count= −0.28, p=.16), PBAC (b = −0.002, CI= −0.013, 0.017, p = .85), DP (mean difference in log count = −0.01, CI = −0.13, 0.11, p = .86), RAPI score (mean difference in log count = −0.03, CI = −0.16, 0.11, p = .68), and PBSS score (b= −0.10, CI= −1.30, 1.09, p = .86) after controlling for potential confounding variables.

3.6 Validation of WBI Efficacy: Change in Peak Estimated Blood Alcohol Content

Results from the repeated measures ANCOVA with hazardous alcohol use, randomization group, and importance rating included as potential confounding variables demonstrated that there was a significant decrease in PBAC from baseline to follow up, with a moderate Cohen's d effect size of .41 (F = 28.34, partial η2 = .10, p= .001). However, randomization assignment was not significantly associated with PBAC (F = 0.17, partial η2 = .001, p= .68).

4. Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to test whether assessment reactivity occurs when web-based research assessments are administered in combination with a web-based brief alcohol intervention for college students. There were no significant reactivity effects for alcohol use, alcohol-related consequences, or protective behaviors related to alcohol consumption when comparing an RAs + WBI condition and a WBI-only condition at one month follow up. Further, a repeated measures ANCOVA confirmed that there were significant, moderately sized WBI effects consistent with the literature (Khadjesari et al., 2011; White et al., 2010), but there were no reactivity effects. Results are in contrast to studies in the college student literature that found evidence of reactivity (Kypri et al., 2007; McCambridge & Day, 2008; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, et al., 2009; Carey et al., 2006). However, these previous studies tested reactivity when RAs were conducted either 1) alone and not combined with a WBI (Kypri et al., 2007; McCambridge & Day, 2008; Walters, Vader, Harris, Field, et al., 2009), or 2) live, in-person (Carey et al, 2006); the current study was the first to test reactivity to web-based RAs combined with a WBI.

It is likely that both the online administration method used for the RAs and their administration in combination with the WBI both contributed to the lack of significant reactivity effects in the current study. In addition it is possible that the brief, 10-minute RAs length was related to the lack of reactivity effects and that longer RAs may produce reactivity effects when administered in combination with a WBI. Clifford, Maisto, and Davis (2007) did find in an experimental test that length of RAs was significantly associated with magnitude of reactivity effects; comprehensive RAs produced more reactivity than brief RAs. However, the Clifford et al (2007) study tested reactivity with RAs administered alone (not combined with an intervention). Thus, it is currently unknown whether longer RAs would produce reactivity effects when combined with a WBI; this is a topic that warrants future investigation. Finally, the lack of reactivity effects may have in part been related to our sample; we recruited a wide range of students with heavy drinking levels, however heavier drinkers were more likely to drop out. Thus, it is possible that among very heavy drinkers, reactivity may occur, and this is another topic for future research.

The results of the current study have implications for establishing WBI efficacy when measuring within-subjects change in alcohol use from baseline to follow up. Our findings suggest that brief pretreatment assessment for research purposes may not bias within-subjects estimates of WBI efficacy. Thus, the results are positive for WBI researchers, who may be justified in conducting brief RAs online to collect information about participant alcohol use pretreatment without biasing within-subjects estimates of efficacy.

Our findings also have implications for establishing efficacy between-groups. While we found there were no significant reactivity effects in a RAs+WBI condition, previous research has demonstrated significant reactivity to RAs-only control conditions (Kypri et al., 2007; McCambridge & Day, 2008; Walters, Vader, Harris, & Jouriles, 2009). When researchers compare treatment and control groups that may have differential reactivity effects, WBI effects may be underestimated, as was observed by Hester et al (2012). This point is important to consider, given that WBI efficacy is usually established by examining both within-subjects change and between groups difference in alcohol consumption at follow up.

Clifford and Davis (2012) highlighted in their review of the assessment reactivity literature that the field's understanding of assessment reactivity is “rudimentary” and called for more studies to evaluate factors that contribute to assessment reactivity. As decided a priori, we tested four variables as potential moderating variables: hazardous alcohol use (as defined by the AUDIT), gender, importance in changing drinking as rated at the end of the WBI, and confidence in changing drinking as rated at the end of the WBI. None of these variables significantly moderated the relationship between randomization group and any of the outcomes. Although students with heavier alcohol use/higher AUDIT scores have been shown to be more responsive to WBIs than students with lighter alcohol use patterns (Bersamin, Paschall, Fearnow-Kenney, & Wyrick, 2007; Chiauzzi et al., 2010; Elliott, Carey, & Bolles, 2008), this responsivity did not extend to the RAs administered in the current study. Previously, AUDIT score was found to moderate the relationship between in-person RAs and alcohol use outcomes among students who recently experienced a negative alcohol event (Magill, Kahler, Monti, & Barnett, 2012). The sample in the current study was possibly less severe than the Magill et al (2012) sample and the present study conducted online RAs, not in-person; both of these factors may have contributed to the lack of hazardous alcohol use moderating effects in the current study.

Our analysis of confidence and importance ratings as potential moderating variables was opportunistic in nature rather than comprehensive; single item ratings of importance and confidence are automatically collected in the WBI program we used in the study and we thought these ratings provided as provided at the end of the WBI may have been related to reactivity outcomes. Single item ratings may not sufficient to evaluate motivation; however, previous work has shown that single item importance and confidence ratings predicted change in alcohol use following a BI (Bertholet, Gaume, Faouzi, Gmel, & Daeppen, 2012). There was very low variability in both confidence and importance ratings; participants generally rated their confidence in changing drinking as high and importance in changing their drinking low. Thus, it is possible that this restricted response range dampened our ability to detect of any effects that could possibly be present with a more representative set of responses. This area of research warrants additional examination because it is commonly assumed that assessment reactivity results from RAs increasing participants’ motivation to change or self-efficacy (Clifford & Davis, 2012; Schrimsher & Filtz, 2011).

Finally, gender has been found previously to moderate assessment reactivity in adolescent smoking (Murray, Swan, Kiryluk, & Clarke, 1988), however gender did not appear to have a substantial differential effect on reactivity to assessments among heavy drinking college students.

There were several limitations of the study. First, the study used a convenience sample, which may not be representative of the college student population in the U.S. and Canada. A second limitation is that a substantial proportion of the participants randomized did not complete the WBI, and those who were lost were heavier drinkers at baseline. In addition, participants were more likely to complete the WBI if they were randomized to the WBI only condition as opposed to the RAs+WBI condition, likely due to the differential length of time required for participation. In addition, our follow up completion rate of 68% was lower than expected, however we used multiple imputation, a robust estimation technique, to cope with the missing data. Finally, we used a formula (Matthews & Miller, 1979) to calculate estimated peak blood alcohol content and did not measure blood alcohol content directly. We recognize that the PBAC estimation has inherent limitations as it uses data from self-reports of alcohol use and can over or underestimate PBAC based on over or underestimation of self-reported alcohol use. In addition, this formula does not account for variations in alcohol metabolism. However,BAC calculations have been found to be comparable in accuracy to in vivo breath tests of alcohol concentration (Carey & Hustad, 2002) and to correlate strongly with alcohol use and alcohol-related consequences in college student samples (Borsari et al., 2001; Turner et al., 2004). Thus, while estimated PBAC was imperfect, we feel it was an appropriate proxy measure for PBAC.

The study had several strengths. First, features of the study were designed in accordance with WBI efficacy studies in the literature to aid in generalizability. The study used RAs that have been used extensively in the WBI efficacy literature (e.g., Doumas & Andersen, 2009; Neighbors, Lee, Lewis, Fossos, & Walter, 2009; Walters, Vader, & Harris, 2007). The WBI used in the study has been widely disseminated to universities nationally and abroad (San Diego State University Research Foundation, 2009) and has been widely researched. Also in accordance with the literature, the RAs were designed to take about 50% as long as the WBI, although they took somewhat longer than projected. Finally, the study was adequately powered to detect small effects.

5. Conclusions

The current study contributes to the literature by identifying an experimental condition under which assessment reactivity may not be present and does not appear to inflate WBI efficacy estimates when examined within-subjects. In addition to the implications for WBI efficacy research, the results also have positive implications for WBI dissemination. WBI programs have been widely distributed to universities nationwide and abroad as general services for students. Universities using these programs may likely observe similar effect sizes to those reported in the literature; however, effectiveness studies are needed.

Highlights.

No significant reactivity effects from online assessments combined with an alcohol intervention

Online assessments did not inflate intervention efficacy estimates measured within-subjects

Findings indicate universities may observe intervention effects similar to efficacy studies

Acknowledgments

Funded by the Vermont Conferences on Primary Prevention. NIAAA grant R01 AA018658 (Gail Rose, PI) supported the authors’ time during the study.

Abbreviations used

- WBI

Web-based brief alcohol intervention

- RAs

Research assessments

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. Guidelines for use in primary health care. World Health Organization; 1992. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test. [Google Scholar]

- Bersamin M, Paschall MJ, Fearnow-Kenney M, Wyrick D. Effectiveness of a Web-based alcohol-misuse and harm-prevention course among high- and low-risk students. Journal of American College Health: J of ACH. 2007;55(4):247–254. doi: 10.3200/JACH.55.4.247-254. http://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.55.4.247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertholet N, Gaume J, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Daeppen J-B. Predictive value of readiness, importance, and confidence in ability to change drinking and smoking. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:708. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-708. http://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-12-708. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Carey KB. Effects of a Brief Motivational Intervention with College Student Drinkers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68(4):728–733. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.68.4.728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsari B, Neal DJ, Collins SE, Carey KB. Differential Utility of Three Indexes of Risky Drinking for Predicting Alcohol Problems in College Students. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors : Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2001;15(4):321. doi: 10.1037//0893-164x.15.4.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Carey MP, Maisto SA, Henson JM. Brief motivational interventions for heavy college drinkers: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74(5):943–954. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.5.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Hustad JTP. Are Retrospectively Reconstructed Blood Alcohol Concentrations Accurate? Preliminary Results from a Field Study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2002;63(6):762. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiauzzi E, Green TC, Lord S, Thum C, Goldstein M. My Student Body: A High-Risk Drinking Prevention Web Site for College Students. Journal of American College Health. 2010;53(6):263–274. doi: 10.3200/JACH.53.6.263-274. http://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.6.263-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure: A critical review of the literature. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(4):773–781. doi: 10.1037/a0029747. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0029747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA. Subject Reactivity Effects and Alcohol Treatment Outcome Research. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2000;61(6):787–793. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2000.61.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clifford PR, Maisto SA, Davis CM. Alcohol treatment research assessment exposure subject reactivity effects: part I. Alcohol use and related consequences. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68(4):519–528. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social Determinants of Alcohol Consumption: The Effects of Social Interaction and Model Status on the Self-Administration of Alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53(2):189–200. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.2.189. http://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Andersen LL. Reducing Alcohol Use in First-Year University Students: Evaluation of a Web-Based Personalized Feedback Program. Journal of College Counseling. 2009;12(1):18–32. [Google Scholar]

- Doumas DM, Haustveit T, Coll KM. Reducing Heavy Drinking Among First Year Intercollegiate Athletes: A Randomized Controlled Trial of Web-Based Normative Feedback. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology. 2010;22(3):247–261. http://doi.org/10.1080/10413201003666454. [Google Scholar]

- Ekman DS, Andersson A, Nilsen P, Ståhlbrandt H, Johansson AL, Bendtsen P. Electronic screening and brief intervention for risky drinking in Swedish university students — A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(6):654–659. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.015. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott JC, Carey KB, Bolles JR. Computer-based interventions for college drinking: A qualitative review. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(8):994–1005. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied Missing Data Analysis. Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F. G*Power (Version 3.1.3) Universitat Kiel; Germany: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.psycho.uni-duesseldorf.de/abteilungen/aap/gpower3/ [Google Scholar]

- Fazzino TL, Rose GL, Pollack S, Helzer JE. Recruiting U.S. and Canadian college students via social media for participation in a web-based brief intervention study. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2015 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Olchowski AE, Gilreath TD. How many imputations are really needed? Some practical clarifications of multiple imputation theory. Prevention Science: The Official Journal of the Society for Prevention Research. 2007;8(3):206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-007-0070-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester RK, Delaney HD, Campbell W. The College Drinker's Check-Up: Outcomes of Two Randomized Clinical Trials of a Computer-Delivered Intervention. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(1):1–12. doi: 10.1037/a0024753. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0024753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Honaker J, King G, Blackwell M. Amelia II: A Program for Missing Data. Journal of Statistical Software. 2011;45(7):1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Hustad JTP, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35(3):183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imai K, King G, Lau O. Zelig: Everyone's Statistical Software. 2007 Retrieved from http://GKing.harvard.edu/zelig.

- Imai K, King G, Lau O. Toward A Common Framework for Statistical Analysis and Development. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics. 2008;17(4):892–913. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly-Weeder S. Binge drinking in college-aged women: framing a gender-specific prevention strategy. Journal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners. 2008;20(12):577–584. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00357.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-7599.2008.00357.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khadjesari Z, Murray E, Hewitt C, Hartley S, Godfrey C. Can stand-alone computer-based interventions reduce alcohol consumption? A systematic review. Addiction. 2011;106(2):267–282. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03214.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kypri K, Langley JD, Saunders JB, Cashell-Smith ML. Assessment may conceal therapeutic benefit: findings from a randomized controlled trial for hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2007;102(1):62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01632.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CM, Neighbors C, Lewis MA, Kaysen D, Mittmann A, Geisner IM, Larimer ME. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Spring Break Intervention to Reduce High-Risk Drinking. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035743. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0035743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lewis MA, Patrick ME, Litt DM, Atkins DC, Kim T, Blayney JA, Larimer ME. Randomized Controlled Trial of a Web-Delivered Personalized Normative Feedback Intervention to Reduce Alcohol-Related Risky Sexual Behavior Among College Students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2014 doi: 10.1037/a0035550. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0035550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Magill M, Kahler CW, Monti P, Barnett NP. Do research assessments make college students more reactive to alcohol events? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(2):338–344. doi: 10.1037/a0025571. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0025571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martens MP, Ferrier AG, Sheehy MJ, Corbett K, Anderson DA, Simmons A. Development of the Protective Behavioral Strategies Survey. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2005;66(5):698–705. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2005.66.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DB, Miller WR. Estimating blood alcohol concentration: two computer programs and their applications in therapy and research. Addictive Behaviors. 1979;4(1):55–60. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(79)90021-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Day M. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of completing the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test questionnaire on self-reported hazardous drinking. Addiction. 2008;103(2):241–248. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02080.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCambridge J, Kypri K. Can Simply Answering Research Questions Change Behaviour? Systematic Review and Meta Analyses of Brief Alcohol Intervention Trials. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10):e23748. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023748. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0023748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller ET, Neal DJ, Roberts LJ, Baer JS, Cressler SO, Metrik J, Marlatt GA. Test-Retest Reliability of Alcohol Measures: Is There a Difference Between Internet-Based Assessment and Traditional Methods? Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2002;16(1):56–63. http://doi.org/10.1037/0893-164X.16.1.56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray M, Swan AV, Kiryluk S, Clarke GC. The Hawthorne effect in the measurement of adolescent smoking. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 1988;42(3):304–306. doi: 10.1136/jech.42.3.304. http://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/jech.42.3.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal DJ, Carey KB. Developing Discrepancy Within Self-Regulation Theory: Use of Personalized Normative Feedback and Personal Strivings with Heavy-Drinking College Students. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29(2):281–297. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Walter T. Internet-Based Personalized Feedback to Reduce 21st-Birthday Drinking: A Randomized Controlled Trial of an Event-Specific Prevention Intervention. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):51–63. doi: 10.1037/a0014386. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0014386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelder JA, Wedderburn RWM. Generalized Linear Models. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General) 1972;135(3):370. http://doi.org/10.2307/2344614. [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of Alcohol and Other Drug Use Among American College Students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;(Suppl14):23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Antin T, Ringwalt CL, Saltz RF. Effects of AlcoholEdu for College on Alcohol-Related Problems Among Freshmen: A Randomized Multicampus Trial. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2011;72(4):642. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson MR, Kite BA, Henson JM. The assessment of protective behavioral strategies: Comparing prediction and factor structures across measures. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):573–584. doi: 10.1037/a0028187. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0028187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen ER, Grow J, Duncan S, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Concurrent validity of an online version of the Timeline Followback assessment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: Journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26(3):672–677. doi: 10.1037/a0027945. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0027945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2012 Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/

- Rubin DB. Inference and missing data. Biometrika. 1976;63(3):581–592. http://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/63.3.581. [Google Scholar]

- Rueger SY, Trela CJ, Palmeri M, King AC. Self-administered web-based timeline followback procedure for drinking and smoking behaviors in young adults. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(5):829–833. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Diego State University Research Foundation eCHECKUP TO GO :: San Diego State University Research Foundation. 2009 Retrieved January 28, 2015, from http://www.echeckuptogo.com/usa/

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption: II. Addiction. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrimsher G, Filtz K. Assessment Reactivity: Can Assessment of Alcohol Use During Research be an Active Treatment? Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly. 2011;29(2):108–115. http://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2011.557983. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . Results from the 2012 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings, NSDUH Series H-46, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 13-4795. Rockville, MD: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Turner JC, Bauerle J, Shu J. Estimated blood alcohol concentration correlation with self-reported negative consequences among college students using alcohol. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65(6):741–749. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR. A Controlled Trial of Web-Based Feedback for Heavy Drinking College Students. Prevention Science. 2007;8(1):83–88. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-006-0059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Field CA, Jouriles EN. Dismantling Motivational Interviewing and Feedback for College Drinkers: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77(1):64–73. doi: 10.1037/a0014472. http://doi.org/10.1037/a0014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters ST, Vader AM, Harris TR, Jouriles EN. Reactivity to alcohol assessment measures: an experimental test. Addiction. 2009;104(8):1305–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02632.x. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02632.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Rimm EB. A gender-specific measure of binge drinking among college students. American Journal of Public Health. 1995;85(7):982. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler H, Nelson TF. What we have learned from the Harvard School Of Public Health College Alcohol Study: focusing attention on college student alcohol consumption and the environmental conditions that promote it. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(4):481–490. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White A, Kavanagh D, Stallman H, Klein B, Kay-Lambkin F, Proudfoot J, Young R. Online alcohol interventions: a systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2010;12(5):e62. doi: 10.2196/jmir.1479. http://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White HR, Labouvie EW. Towards the Assessment of Adolescent Problem Drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1989;50(1):30–37. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1989.50.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]