Abstract

Background:

Hepatologists have studied serologic markers of liver injury for decades. Annexins are a prominent group of such markers and annexin A2 (AnxA2) is one of the best characterized annexins. AnxA2 inhibits HBV polymerase among other functions. Its expression is up-regulated in regenerative hepatocytes.

Objectives:

To determine if serum AnxA2 level has a role in estimating liver damage in chronic HBV infection and investigate whether AnxA2 levels correlate with hepatic fibrosis.

Patients and Methods:

This study included 173 patients with chronic hepatitis B (CHB) and 51 healthy controls. Liver fibrosis was graded histologically on liver biopsy samples. Blood samples were taken from patients during biopsy and serum AnxA2 levels were measured with ELISA.

Results:

In a group of adult patients with CHB, AnxA2 values were far higher than those of the control group (P = 0.001). When we assessed AnxA2 levels based on fibrosis stages, serum AnxA2 levels of patients with early stage fibrosis (stages 1 - 3) were significantly higher than those of patients with advanced stage fibrosis (stages 4 - 5; P = 0.001).

Conclusions:

AnxA2 is a useful biomarker for early stage fibrosis in patients with CHB.

Keywords: Annexin A2, Hepatitis B, Chronic, Liver Fibrosis, Biological Marker

1. Background

There are more than 350 million hepatitis B virus (HBV) infected people worldwide. HBV is the most important cause of chronic hepatitis, cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). HBV causes significant morbidity and medical expenditure (1, 2).

ANXs are a family of calcium and lipid-binding proteins that contain unique calcium-binding properties. Twelve ANX subfamilies have been identified in vertebrates (3). AnxA2, also called annexin II, is one of the best-characterized ANXs. AnxA2 has a role in exocytosis and endocytosis, cell-cell adhesion, cell proliferation, cell surface fibrinolysis, osteoclast formation and bone resorption. Furthermore, AnxA2 has been implicated in cell growth regulation and apoptosis. It has also been reported that HBV polymerase activity is inhibited by S100A10, a protein binding to AnxA2 (3, 4).

AnxA2 expression is up-regulated in several types of spontaneous neoplasms, such as pancreatic cancer, gastric cancer, colorectal cancer and high-grade glioma (5, 6). AnxA2 levels are increased in proliferative or regenerative hepatocytes, suggesting that this protein plays a role in normal hepatocyte growth (7). AnxA2 levels are also elevated in patients with HCC.

To overcome the complications risked by invasive tissue sampling in liver biopsy, noninvasive serological biomarkers of hepatic fibrosis have been developed to estimate liver damage. Among serologic biomarkers, so-called “direct serological markers” include procollagen types I and III. Indirect serological markers include gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), total bilirubin, alpha-2-macroglobulin and alpha-2-globulin (haptoglobin). Furthermore, some diagnostic panels for liver fibrosis include aspartate aminotransferase (AST) to platelet ratio (APRI), Hepascore, FibroTest/FibroSure and FibroSpect (8). These clinical diagnostic panels of liver fibrosis have been studied mainly in chronic hepatitis C (HCV). Currently, no single serum biomarker is the diagnostic “gold standard” for liver fibrosis (9).

As AnxA2 is overexpressed in regenerative hepatocytes, we hypothesized that AnxA2 could be implemented as a surrogate marker of liver injury in CHB patients.

2. Objectives

To determine if serum AnxA2 level has a role in estimating liver damage in chronic HBV infection and investigate whether AnxA2 levels correlate with hepatic fibrosis.

3. Patients and Methods

3.1. Patients

A total of 173 CHB patients and 51 healthy controls were included in this study. The study was performed in the infectious disease clinics of Adiyaman State Hospital, Adiyaman 82nd Year State Hospital, and Adana State Hospital between January 1st and December 31st, 2010. Patients’ characteristics and demographic data were recorded in special forms. The control group consisted of healthy volunteers without any sign of viral hepatitis (HBsAg negative, anti-HBc negative, anti-HCV negative) with normal ALT/AST ratios. Patients with coagulation abnormalities (PT ≥ 1.5 INR [international normalized ratio] and/or platelet count ≤ 50,000/mm3) and those who did not consent to liver biopsy were excluded from the study. Furthermore, patients were screened for underlying HCC with AFP and liver ultrasound. Patients who had an elevated AFP level or mass lesion in the liver were excluded from the study.

3.2. Ethics

This study was performed in accordance with the 2000 Declaration of Helsinki of the World Medical Association. The ethical committee of Adiyaman University reviewed and approved the study protocol. All patients were informed about possible adverse outcomes by the authors before the liver biopsy. All participants read and signed an informed consent agreement.

3.3. Preparation for Liver Biopsy

All patients underwent pre-biopsy screening tests including a hepatitis panel as well as tests for ALT, AST, HBV DNA, platelet (PLT) count and prothrombin time (PT). Ultrasound imaging of the liver was mandatory before the liver biopsy. Patients were excluded per the criteria above.

3.4. Liver Biopsy

Liver biopsy indication was established as suggested by the American Association for the study of liver diseases (AASLD) (10). The degree of fibrosis was assessed using a six-stage scoring system, the Ishak score (11). This scoring system has separate staging systems for fibrosis and necro-inflammation (11).

3.5. Determination of AnxA2

This study was performed using a USCN AnxA2 micro ELISA kit (Uscn E91944HU, Wuhan, Hubei, China).

3.6. Virological and Biochemical Parameters

HBsAg, anti-HBs, HBeAg and anti-HBe were detected with Macro-ELISA (Abbott AXSYM System, Germany). HBV DNA was measured with real-time PCR (ICycler IQ Real-Time PCR; BioRad, USA). ALT, AST and albumin levels were measured using an Abbott Architect Plus c16000 device. Complete blood count was measured with Sysmex XT 2000i (Roche). A Modular E170 (Roche) device was used to determine serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels.

3.7. Statistical Analyses

Data was analyzed using SPSS 16.0 software (IBM, America). The descriptive statistics are shown as Mean ± Standard Deviation, median (minimum–maximum value) and percentage distribution. Statistical analysis was performed using a chi-square test and t-test for independent groups. Kruskal-Wallis test and post-hoc Bonferroni modified Mann-Whitney U test were used for AnxA2 analysis based on stages. As a result of the analyses, P < 0.05 considered as statistically significant.

4. Results

Of 173 patients, 112 (64.7%) were male and 61 (35.3%) female. The control group consisted of 25 (49.0%) male and 26 (51.0%) female volunteers. The mean age of patients was 34.0 ± 10.8 years and that of the control group 33.8 ± 9.3 years.

ALT, HBV DNA, AFP, PLT and albumin values (median; range) of patients based on fibrosis stages in the liver biopsies are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. ALT, HBV DNA, AFP, PLT and Albumin Values of Patients Based on Fibrosis Stages in Liver Biopsya,b.

| Variable | Stage 1 (N = 33) | Stage 2 (N = 68) | Stage 3 (N = 37) | Stage 4 (N = 23) | Stage 5 (N = 12) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT, U/L | 54 (32 - 144) | 56 (32 - 124) | 82 (32 - 164) | 69 (43 - 145) | 87 (54 - 144) |

| HBV DNA, IU/mL | 6.7 × 104 (1.2 × 104 - 11 × 107) | 1.3 × 105 (1.2 × 104 - 11 × 107) | 11 × 108 (1.2 × 104 - 9.8 × 1010) | 6 × 107 (4.5 × 105 - 1.2 × 1010) | 1.1 × 109 (2.3 × 106 - 3.2 × 109) |

| AFP, ng/mL | 5 (3 - 8) | 5 (3 - 8) | 6 (3 - 8) | 6 (3 - 13) | 6 (3 - 34) |

| PLT, mm3 | 2.3 × 105 (1.1 × 105 - 4.3 × 105) | 2.8 × 105 (1.8 × 105 - 4.3 × 105) | 2.8 × 105 (1.8 × 105 - 3.5 × 105) | 2.7 × 105 (1.1 × 105 - 4.3 × 105) | 1.8 × 105 (1.1 × 105 - 2.8 × 105) |

| Albumin, g/dL | 4.0 (3.9 - 4.5) | 4.0 (3.9 - 4.6) | 4.0 (3.8 - 4.6) | 3.9 (3.2 - 4.0) | 3.5 (3.0 - 4.1) |

aAbbreviations: AFP: alpha fetoprotein, ALT: alanine aminotransferase, HBVDNA; hepatitis B virus DNA, PLT: platelet.

bValues are presented as median (range).

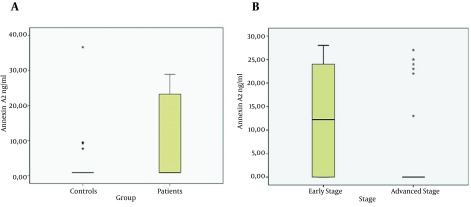

The AnxA2 value of patients was higher than that of the control group (P = 0.001; Figure 1 A). When we assessed AnxA2 levels based on fibrosis stages, the serum AnxA2 levels of patients with early fibrosis (stages 1, 2, and 3) were significantly higher than the AnxA2 levels of patients with advanced fibrosis (stages 4 and 5, P = 0.001; Figure 1 B).There was no difference between serum AnxA2 levels of patients with stage 5 fibrosis and those of the control group; AnxA2 levels did not differ according to age and gender groups.

Figure 1. Change in Annexin A2 Levels.

A, Annexin A2 values of patients and control groups. B, Annexin A2 levels according to Fibrosis stages.

5. Discussion

AnxA2 is a biomarker associated with liver fibrosis, but its mechanism and clinicaluse are unknown. Only a few studies have investigated the association of AnxA2 and liver fibrosis (3, 4).

During the development of liver fibrosis, many molecular changes occur. AnxA2 was first defined as a biomarker of liver fibrosis by Zhang et al. (12). It was postulated that AnxA2 could be used as a noninvasive marker for diagnosis of HBV-related liver fibrosis. Moreover, we and others have shown that age and gender did not affect serum AnxA2 levels (13). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study evaluating serum AnxA2 levels in CHB patients. In our study, AnxA2 levels of CHB patients were significantly higher than those of control group, reflecting ongoing hepatocyte injury through the course of CHB disease. Furthermore, we examined whether serum AnxA2 levels could be implemented as a tool for noninvasive liver fibrosis measurement. Serum AnxA2 levels of patients with early stage fibrosis (stages 1, 2, and 3) were significantly higher than serum AnxA2 levels of patients with advanced stage fibrosis (stages 4 and 5; Figure 1 B). Zhang et al. (12) previously showed in an animal model that AnxA2 expression was elevated in advanced cirrhosis compared to early liver damage. They could not demonstrate that plasma AnxA2 levels differed between early and advanced stages of fibrosis. We speculate that AnxA2 may be overexpressed in the liver without elevating serum AnxA2. Since hepatocytes are the main source of AnxA2, decreased serum AnxA2 levels may reflect a diminished hepatocyte reservoir at advanced fibrosis stages. Elevated AnxA2 levels could also result from denovo liver carcinogenesis. In this study, we tried to rule out possible underlying HCC by excluding patients with elevated AFP levels or ultrasound abnormalities. That is why we think our results were not biased by underlying HCC. Furthermore, to our knowledge, none of our patients developed cancer until the year 2015.

Our study had some limitations, including its retrospective design and a limited number of advanced-stage patients. Future studies designed to analyze larger cohorts prospectively could improve the evidence for AnxA2 as a clinical biomarker for hepatic fibrosis. Because we could not identify the source of AnxA2 in this study, it is not easy to speculate regarding abnormal AnxA2 levels.AnxA2 is not liver-specific and its level may increase in the presence of concomitant inflammatory conditions. In addition, its serum level depends on its clearance rate, which may be influenced by some cofounders such as dysfunction of endothelial cells, impaired biliary excretion or renal function, ethnicity and body mass index (12), which were not focused in the study.

In conclusion, we showed that serum AnxA2 levels are most elevated early in the course of CHB infection. AnxA2 may have clinical use as a biomarker or may be integrated with one or more liver fibrosis-predicting biomarker panels for the detection of early-stage fibrosis in patients with CHB infection.

Footnotes

Authors’ Contributions:Servet Kolgelier, Nazlim Aktug Demir, Serap Ozcimen: examination of patients, data collection, writing the manuscript; Ahmet Cagkan Inkaya, Sua Sumer: writing the manuscript; Lutfi Saltuk Demir: statistical analysis; Fatma Seher Pehlivan: pathological analysis; Mahmure Arslan, Abdullah Arpaci: biochemical analysis.

References

- 1.Pungpapong S, Kim WR, Poterucha JJ. Natural history of hepatitis B virus infection: an update for clinicians. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(8):967–75. doi: 10.4065/82.8.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liaw YF. Natural history of chronic hepatitis B virus infection and long-term outcome under treatment. Liver Int. 2009;29 Suppl 1:100–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2008.01941.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ji NY, Park MY, Kang YH, Lee CI, Kim DG, Yeom YI, et al. Evaluation of annexin II as a potential serum marker for hepatocellular carcinoma using a developed sandwich ELISA method. Int J Mol Med. 2009;24(6):765–71. doi: 10.3892/ijmm_00000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao Y, Ben H, Qu S, Zhou X, Yan L, Xu B, et al. Proteomic analysis of primary duck hepatocytes infected with duck hepatitis B virus. Proteome Sci. 2010;8:28. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-8-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki S, Tanigawara Y. Forced expression of S100A10 reduces sensitivity to oxaliplatin in colorectal cancer cells. Proteome Sci. 2014;12:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-5956-12-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Deng S, Wang J, Hou L, Li J, Chen G, Jing B, et al. Annexin A1, A2, A4 and A5 play important roles in breast cancer, pancreatic cancer and laryngeal carcinoma, alone and/or synergistically. Oncol Lett. 2013;5(1):107–12. doi: 10.3892/ol.2012.959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohammad HS, Kurokohchi K, Yoneyama H, Tokuda M, Morishita A, Jian G, et al. Annexin A2 expression and phosphorylation are up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Oncol. 2008;33(6):1157–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranova A, Lal P, Birerdinc A, Younossi ZM. Non-invasive markers for hepatic fibrosis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:91. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parkes J, Guha IN, Roderick P, Rosenberg W. Performance of serum marker panels for liver fibrosis in chronic hepatitis C. J Hepatol. 2006;44(3):462–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rockey DC, Caldwell SH, Goodman ZD, Nelson RC, Smith AD, American Association for the Study of Liver D. Liver biopsy. Hepatology. 2009;49(3):1017–44. doi: 10.1002/hep.22742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishak K, Baptista A, Bianchi L, Callea F, De Groote J, Gudat F, et al. Histological grading and staging of chronic hepatitis. J Hepatol. 1995;22(6):696–9. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(95)80226-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang L, Peng X, Zhang Z, Feng Y, Jia X, Shi Y, et al. Subcellular proteome analysis unraveled annexin A2 related to immune liver fibrosis. J Cell Biochem. 2010;110(1):219–28. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ibrahim AM, Hashem ME, Mostafa EF, Refaey MM, Hamed EF, Ibrahim I, et al. Annexin A2 versus Afp as an efficient diagnostic serum marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gastroenterol Hepatol Res. 2013;2(9):780–5. [Google Scholar]