Abstract

This paper reports effects of surface preparation and contact loads on abrasive wear properties of highly aesthetic and high-strength pressible lithium disilicate glass-ceramics (LDGC). Abrasive wear testing was performed using a pin-on-disk device in which LDGC disks prepared with different surface finishes were against alumina pins at different contact loads. Coefficients of friction and wear volumes were measured as functions of initial surface finishes and contact loads. Wear-induced surface morphology changes in both LDGC disks and alumina pins were characterized using 3D laser scanning microscopy, scanning electron microscopy and energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy. The results show that initial surface finishes of LDGC specimens and contact loads significantly affected the friction coefficients, wear volumes and wear-induced surface roughness changes of the material. Both wear volumes and friction coefficients of LDGC increased as the load increased while surface roughness effects were complicated. For rough LDGC surfaces, three-body wear was dominant while for fine LDGC surfaces, two-body abrasive wear played a key role. Delamination, plastic deformation and brittle fracture were observed on worn LDGC surfaces. The adhesion of LDGC matrix materials to alumina pins was also discovered. This research has advanced our understanding of the abrasive wear behaviour of LDGC and will provide guidelines for better utilisation and preparation of the material for long-term success in dental restorations.

Keywords: Lithium disilicate glass ceramic, Coefficient of friction, Wear mechanisms, Wear volume, Surface roughness

1. INTRODUCTION

All-ceramic restorations have been very popular in last decades, and this trend is expected to continue due to successful applications of advanced dental technologies and biocompatible and aesthetic ceramics.1–8 The development of durable dental ceramics with high strength and toughness, such as lithium disilicate glass ceramics (LDGC) and yttria-stabilized tetragonal zirconia polycrystals (Y-TZP), significantly contributes to the popularity rise of all-ceramic restorations.9–15 Classic Y-TZP is opaque and does not match the natural tooth colour although it has the highest fracture resistance among dental ceramics.16 In general, zirconia crowns need to be veneered with aesthetic porcelains for improved aesthetic outcomes.15,17 Based on fatigue findings, the CAD/CAM-made lithium disilicate ceramic in a monolithic/fully anatomical configuration resulted in fatigue-resistant crowns, whereas hand-layer-veneered zirconia crowns revealed a high susceptibility to mouth-motion cyclic loading with early veneer failures.14,17–19 Thus, highly aesthetic and high-strength LDGC are an excellent material choice for monolithic dental crowns.14

LDGC can be made from pressable ceramic ingots with different degrees of opacity.20 Their microstructures consist of approximately 70% needle-like lithium disilicate (Li2Si2O5) crystals embedded in a glassy matrix containing SiO2, K2O, MgO, Al2O3, P2O5 and other oxides. Lithium disilicate crystal sizes generally range from 3 μm to 6 μm in length and 0.5 μm to 0.8 μm in width.20 LDGC provide a good combination of durability with excellent aesthetics, enhanced mechanical strength of 400 MPa and improved translucency.20–23

LDGC have been used for single restorations as anterior and posterior crowns24 and three-unit fixed dental prostheses.25 A two-year clinical evaluation of chairside lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns has shown that monolithic lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns may be an effective option for all-ceramic crowns.26 They had a low clinical failure rate after up to 120 months.27 The cumulative survival rate for single crowns according to Kaplan-Meier was 97.4% after five years and 94.8% after eight years, respectively.24 The survival rate for three-unit LDGC fixed dental prostheses according to Kaplan-Meier was 93% after eight years.25 Another study has shown that the fixed dental prostheses’ survival rate (survival being defined as remaining in place either with or without complications) was 100% after five years and 87.9% after 10 years.28 Their success rate (success being defined as remaining unchanged and free of complications) was 91.1% after five years and 69.8% after 10 years.28

Tribological properties are important in the material design and fabrication of dental restorations, which determine the restorative longevity and functions.29–34 Wear is a continuous and progressive phenomenon associated with ceramic restorations. Occlusal wear is influenced by material structures and properties, fabrication processes and service conditions.29,35,36 Especially, surface quality of ceramic restorations, hardness of food, pH values of saliva, chewing behaviours and magnitudes of masticatory loads, remarkably affect the wear performance of ceramic restorations in the oral environment.4,29,37–42

Efforts have been made towards the wear behaviour of LDGC. A clinical study demonstrated that the wear resistance of LDGC (IPS e.max Press) crowns were superior to the alumina-coping-based ceramic (Procera AllCeram) crowns.43 Comparisons among three porcelain-veneered zirconia ceramics, LDGC and conventional feldspathic porcelain have found that leucite ceramic (Vita-Omega 900) led to the greatest amount of enamel wear, followed by LDGC-based IPS e.max Press, zirconia-based Prettau, zirconia-based Lava and zirconia-based Rainbow.30 A claim that the surface roughness of ceramic specimens had no significant effect on wear30 is controversial to general wear principles. The systematic laboratory tests concluded that LDGC generally caused more antagonist wear than the low-fusing metal-ceramic structures and leucite ceramics.44 The antagonist wear properties of LDGC, specifically the effects of its hardness, strength and surface roughness on wear, were evaluated. The study concluded that neither the hardness nor the strength of the material had a decisive effect on abrasive wear while the surface roughness played a particularly important role in the abrasion of antagonists.44

Despite significant research on contributing factors in wear processes of dental ceramics, published data provide either inconsistent or inconclusive results. The main influences on the wear behaviour of newer dental ceramics, such as LDGC, need to be further researched to obtain consistent results.44 Surface properties are important as many bioceramics exhibit sensitivities to contact morphologies. Thus, the friction and wear behaviour would be dependent on these properties. In particular, in the oral environment, the abrasive wear of dental ceramics is normally due to very hard, rough particles in food. The abrasive wear behaviour of dental ceramics is critical to long-term survival of ceramic restorations. However, the knowledge of such behaviour of LDGC is unknown.

This study was to investigate effects of surface roughness and contact loads on the wear behaviour of LDGC. More specifically, two fundamental questions were addressed: (a) whether a highly polished surface is beneficial to the abrasive wear process and (b) whether wear mechanisms are affected by initial surface finishes and loading conditions. The abrasive wear between LDGC disks with different surface finishes and alumina pins were tested at different contact loads. Coefficients of friction, wear volumes, and wear-induced surface morphology changes in both LDGC disks and alumina pins were assessed. Finally, abrasive wear mechanisms of LDGC were analysed.

2. MATERIALS & METHODS

2.1. Materials

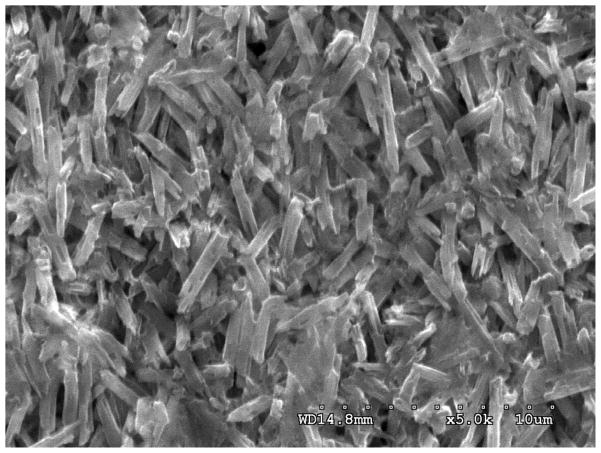

Pressible LDGC blocks (IPS e.max press, Ivoclar Vivadent) of 13-mm diameter and 10-mm thickness, were selected as the wear disk material in this investigation. The microstructure of this ceramic consists of approximately 70 vol% crystalline lithium disilicate (Li2Si2O5) phase embedded in a glassy matrix of the SiO2–Li2O–K2O–ZnO–P2O5–Al2O3–La2O3 system.21,22,45 The properties of the material are: fracture toughness of 2.5–3.0 MPam1/2, average modulus of elasticity of 95 GPa, average Vickers hardness of 5.9 GPa and density of 2.5 g/cm3.20 LDGC specimens were prepared to obtain four different surface finishes, i.e., unpolished, low-, medium- and high-polished finishes. Low-polished surfaces were polished using 45-μm diamond paste. Medium- and high-polished finishes were achieved using diamond pastes down to 3 μm and 1 μm, respectively. Prior to the wear testing, all LDGC specimens were cleaned with ethanol and water and then dried in airflow. Their surface finishes were measured using three-dimensional laser scanning microscopy (3D-LSM, Keyence, Hong Kong). The average arithmetic surface roughness values of the unpolished, low-polished, medium-polished and highly polished LDGC specimens were 1846 nm, 164 nm, 69 nm and 28 nm, respectively. One highly polished LDGC specimen was etched by 4% HF for 30 s to remove the glass phase. The etched LDGC surface was viewed using scanning electron microscopy (Model S-3500N, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Figure 1 shows the SEM micrograph of LDGC morphology in which lithium disilicate crystal structures are clearly revealed. Most lithium disilicate crystals are needle-like and randomly oriented, with the maximum length of approximately 5 μm and the average diameter of less than 1 μm. The residual glass matrix is also observed, where the lithium disilicate crystal boundaries look unclear. The crystallite content in the glass matrix is approximately 70 vol%.

Figure 1.

SEM micrograph of the etched LDGC surface revealing lithium disilicate crystals.

Alumina balls with 92% of alumina and approximately 19 GPa Vickers hardness were used as pins to wear against the LDGC disk specimens. The 2D laser scanning of a fresh alumina pin surface indicates that average alumina grain sizes were smaller than 5 μm. The pins had a diameter of 6 mm and an average arithmetic surface roughness of 1608 nm measured using the laser scanning microscopy. The alumina pin surfaces used in this investigation were much rougher than 10–20 nm alumina pins previously used in abrasive wear studies of dental ceramics.46 This is because in the oral environment, hard particles in food causing serious abrasive wear to both enamel and prostheses are normally very rough without the nano-scale smoothness. Thus, the abrasive wear testing using rough alumina pins was closer to the wear situations in the oral environment.

2.2. Wear testing

A pin-on-disk tribometer (CETR, Campbell, California, USA) was used to conduct the wear tests. Loads of 5 N and 25 N47–49 and a sliding speed of 2.5 mm/s,46,47,50 which were previously applied in dental wear studies, were used in this investigation. All wear tests conducted underwent 10,000 cycles, corresponding to a total contact length of 20 m.47,50 Room temperature and dry conditions were applied to avoid any effect of tribochemical reactions in the pin-disk system.37 The loads were monitored and recorded to make sure that they deviated less than 5% from the targeted loads of 5 and 25 N although the standard deviation for 25 N load was slightly higher. The friction coefficients were automatically recorded throughout the wear testing by the tribometer.

2.3. Surface and wear characterisation

The wear volumes of LDGC specimens were calculated by measuring the width, depth and length of their wear tracks. Surface roughness values of worn LDGC surfaces and alumina pins were measured using the 3D laser scanning microscopy. All measurements were repeated three times to obtain the mean and standard deviation values. Worn LDGC and alumina surfaces were also analyzed using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Hitachi, Dallas, USA) equipped with an energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy. For the SEM analyses, all surfaces were carbon-coated.

Two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at a 95% significance level was used to evaluate effects of the surface roughness and contact loads on the coefficients of friction, wear volumes and wear-induced LDGC roughness changes.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Coefficients of friction

All coefficients of friction measured increased with the time in the first 4000 s and then reached steady plateaus during the wear processes. Figure 2 shows the mean steady-state coefficients of friction versus the mean initial LDGC surface roughness on a logarithmic scale at contact loads of 5 N and 25 N. It reveals that the coefficients of friction significantly increased with the load (p < 0.05), particularly for the medium-polished (69 nm roughness), low-polished (164 nm roughness) and unpolished (1846 nm roughness) surfaces. The difference between the coefficients of friction for the high-polished (28 nm roughness) surfaces at 5 N and 25 N loads was very small. Meanwhile, the initial LDGC surface roughness also significantly affected the coefficients of friction at both loads (p < 0.05). The unpolished LDGC surfaces with the largest surface roughness of 1846 nm yielded higher coefficients of friction at both 5 N and 25 N loads than those of the low-polished roughness of 164 nm and medium-polished roughness of 69 nm. Interestingly, the largest friction coefficients at 5 N and 25 N load were found on the high-polished surfaces, i.e., the smoothest surfaces with 28 nm roughness.

Figure 2.

Coefficients of friciton versus initial LDGC surface roughness on a logarithmic scale.

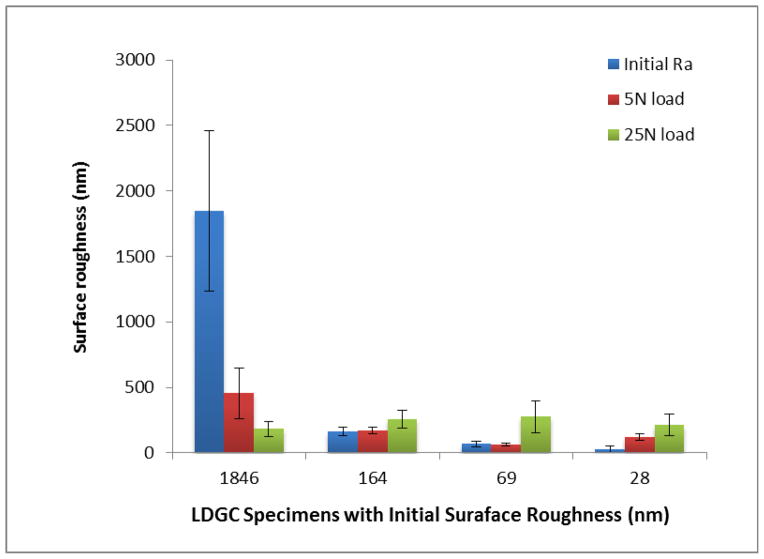

3.2. Wear-induced surface roughness change in LDGC surfaces

Figure 3 shows the wear-induced surface roughness changes of the LDGC specimens. It reveals that the roughest LDGC surfaces with 1846 nm initial surface roughness was remarkably polished in the wear process at both loads, resulting in the much smoother surfaces. The low- and medium-polished LDGC surfaces with 164 nm and 69 nm initial surface roughness values remained nearly unchanged after the wear process at 5 N load. However, they were rubbed to be rougher by wear at 25 N load. The highly polished LDGC surfaces with the initial surface roughness of 28 nm were deteriorated by wear at both loads. These results indicate that both the applied loads and the initial surface roughness of LDGC specimens played important roles in controlling the LDGC surface morphologies during the wear processes.

Figure 3.

Wear-induced surface roughness changes in LDGC surfaces.

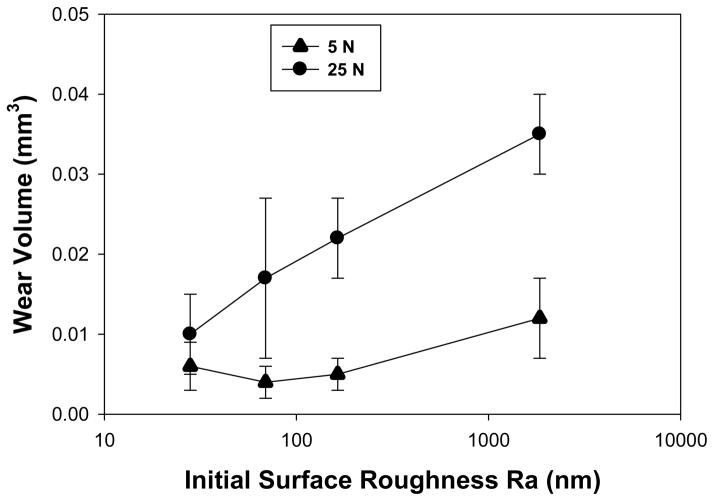

3.3. Wear volumes of LDGC specimens

Figure 4 shows the wear volumes of LDGC versus the initial LDGC surface roughness on a logarithmic scale at 5 N and 25 N loads. The wear volumes for LDGC were significantly higher at 25 N load than at 5 N load (p < 0.05). At 25 N load, the wear volume increased with the initial LDGC surface roughness. At 5 N load, the wear volume also increased with the surface roughness except for the high-polished surfaces (28 nm roughness), at which the wear volumes were higher than the medium-polished surfaces (69 nm roughness). This indicates that at the lower load, wear volumes for highly polished LDGC surfaces were higher than those for medium- and low-polished surfaces. Two-way ANOVA results show that both the initial LDGC surface roughness and contact loads significantly affected the wear volumes in LDGC (p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Wear volumes versus initial LDGC surface roughness on a logarithmic scale.

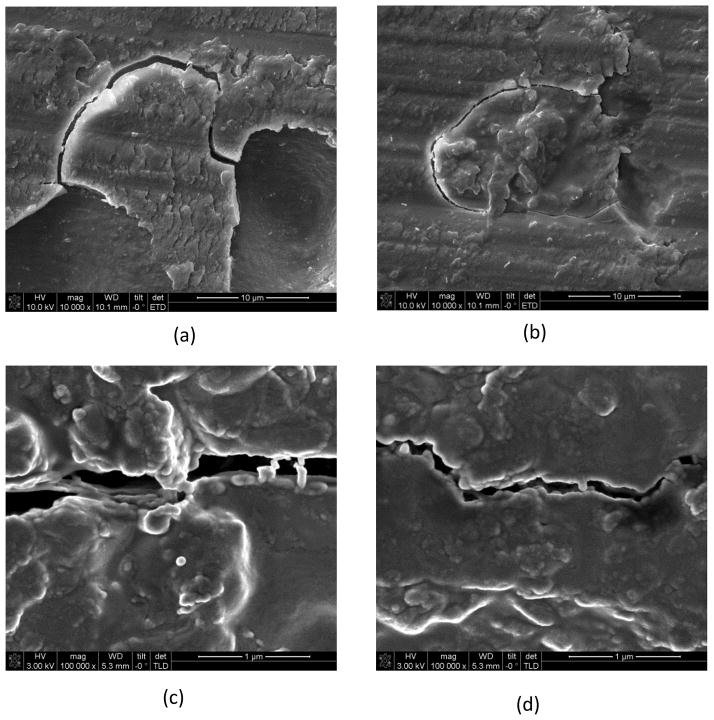

3.4. Wear tracks in LDGC surfaces

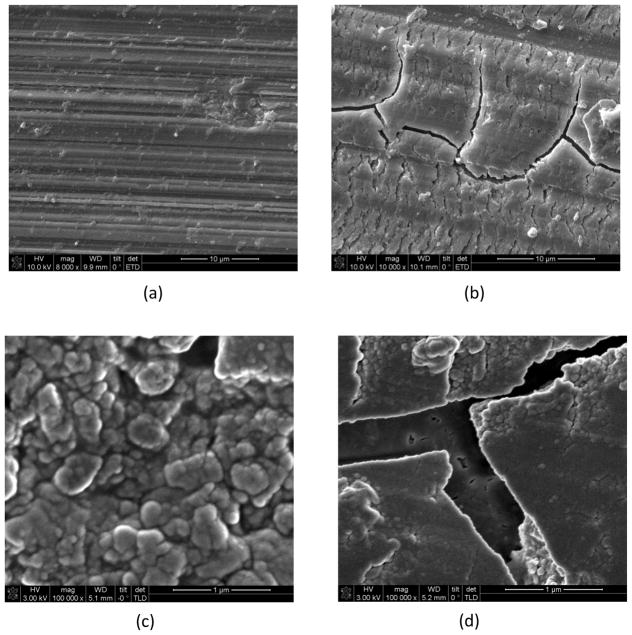

Figures 5a and 5b show the SEM micrographs of wear traces on the unpolished LDGC surface with the initial roughness 1846 nm at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. Both large cracks and shear-removed, plastically deformed layers were observed on the wear traces at both loads. Figures 5c and 5d show the high-magnification SEM micrographs of the cracks and the plastic deformation at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. The cracks with the maximum gap of approximately 300 nm were observed and the crack bridges were also observed in both Figures 5c and 5d. As these crack gaps are much smaller than the sizes of lithium disilicate crystals, this indicates that transgranular fracture occurred in the reinforced crystal phase at both loads. Meanwhile, the shear-removed, plastically deformed layers cover and smoothen the crystal phase structure.

Figure 5.

SEM micrographs of LDGC wear tracks at (a) 5N and (b) 25 N loads on unpolished surfaces (1864 nm roughness); high-magnification SEM micrographs showing details of the wear tracks at (c) 5 N and (d) 25 N loads.

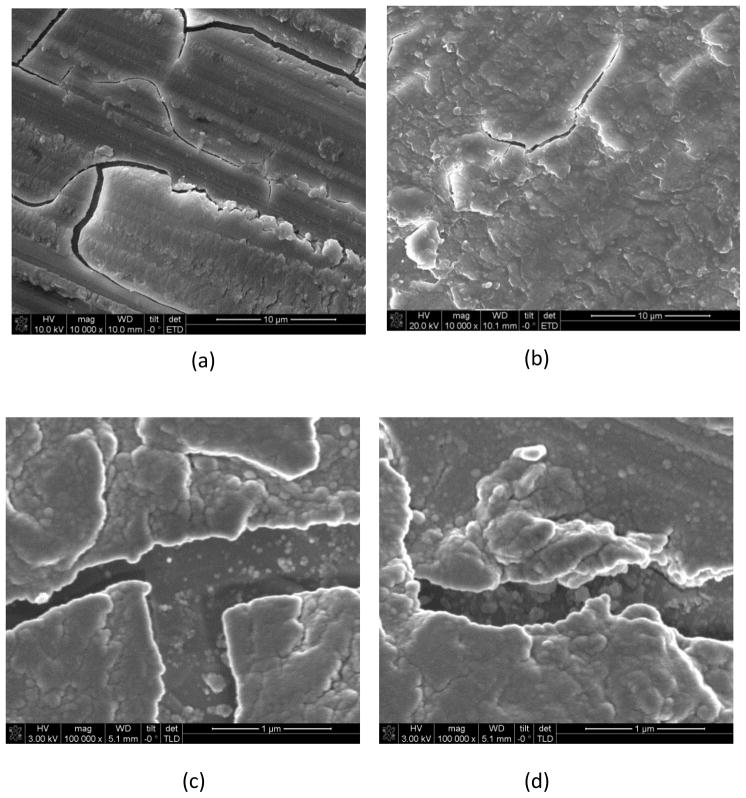

Figures 6a and 6b show the SEM micrographs of wear traces of the low-polished LDGC surface with the initial roughness 164 nm at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. At the low load, the wear scar reveals smooth, with only plastically deformed layers and microscale removal pits. In contract, microcraks and smeared layers are found on the surface loaded with 25 N. Figures 6c shows the high-magnification SEM micrograph of the microscale removal pit area at 5 N load, where the worn area contains nanoparticles with grain sizes of approximately 100–200 nm and microcracks. Figure 6d shows the high-magnification SEM micrograph of the smeared area at 25 N load, where irregular microcracks and 100–300 nm nanoparticles are evident.

Figure 6.

SEM micrographs of LDGC wear tracks at (a) 5N and (b) 25 N loads on low-polished surfaces (164 nm roughness); high-magnification SEM micrographs showing details of the wear tracks at (c) 5 N and (d) 25 N loads.

Figures 7a and 7b shows the SEM micrographs of wear tracks of the medium-polished LDGC surface (69 nm roughness) at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. At the load of 5 N, plastic deformation with minimum material removal was observed. In contrast, large cracks and numerous micro-cracks existed on the surface loaded at 25 N. Figure 7c shows the high-magnification SEM micrograph of the minimally removed area at 5 N load, in which the residual crystal phase in the form of microparticles of up to 400 nm are observed. Figure 7d shows the high-magnification SEM micrograph of microcracks on the worn area at 25 N, in which the crack gaps of up to 400 nm were found.

Figure 7.

SEM micrographs of LDGC wear tracks at (a) 5N and (b) 25 N loads on medium-polished surfaces (69 nm); high-magnification SEM micrographs showing details of the wear tracks at (c) 5 N and (d) 25 N loads.

Figures 8a and 8b show the SEM micrographs of wear tracks on the high-polished LDGC surface (28 nm roughness) at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. Both worn surfaces at 5 N and 25 N loads contain large microcracks and plastically deformed layers. Figures 8c and 8d show the high-magnification SEM micrographs of the microcracks and deformed layers at 5 N and 25 N, respectively. The crack gaps can be as wide as 400 nm.

Figure 8.

SEM micrographs of LDGC wear tracks at (a) 5N and (b) 25 N loads on high-polished surfaces (28 nm); high-magnification SEM micrographs showing details of the wear tracks at (c) 5 N and (d) 25 N loads.

3.5. Wear scars on alumina pins

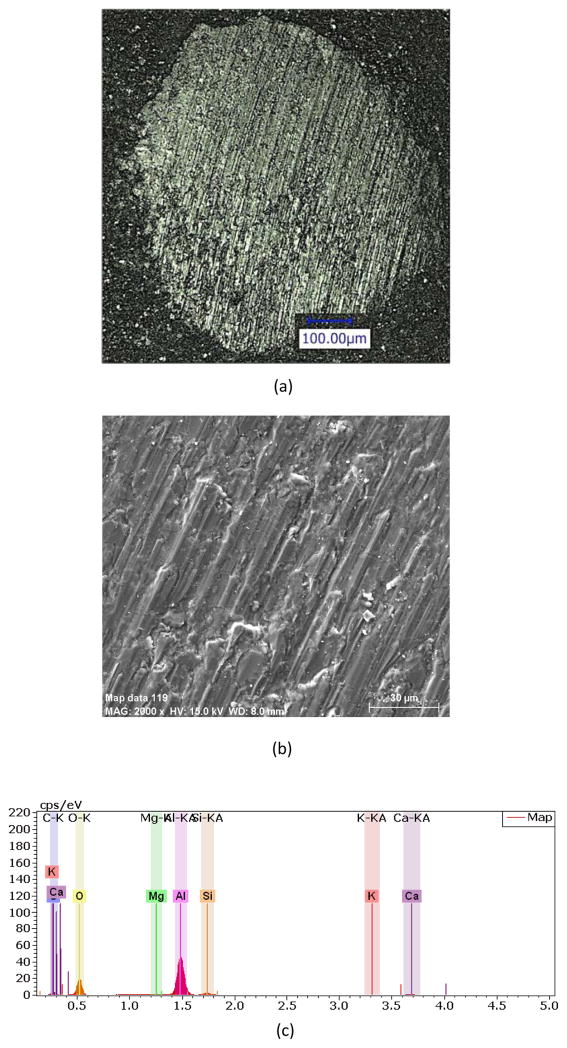

Figure 9a reveals a 2D laser scanning micrograph of a worn alumina pin surface with an arithmetic average roughness of approximately 1300 nm. It shows the scratching traces and adhesions on the alumina surface. Figure 9b shows a SEM micrograph of the detailed wear traces of the alumina pin, in which micro-fracture, plastic deformation and micro-debris are clearly visible. Figure 9c is an energy dispersive x-ray spectrum of the worn alumina pin surface shown in Figure 9b, in which K, Ca, Mg, Si, and Al elements were found. This indicates that the glass matrix in LDGC containing these elements was adhered on the alumina pin surfaces during the wear process.

Figure 9.

(a) 2D laser scanning image of a worn alumina pin; (b) An SEM micrograph of the wear tracks of the alumina pin; and (c) The energy dispersive x-ray spectrum of the wear tracks of the alumina pin demonstrated in Figure 7(b).

4. DISCUSSION

This study has investigated the abrasive wear behaviour of LDGC against alumina using a pin-on-disk tribometer to mimic abrasive wear situations due to hard and coarse particles in the oral environment. Efforts have been made in understanding the influences of surface roughness and contact loads on the wear performance and mechanisms of LDGC.

4.1. Surface roughness effects

Wear-induced surface roughness changes in LDGC (Figure 3) demonstrate that the most significant change occurred on the unpolished surface which roughness decreased approximately five and ten times after wear at 5 N and 25 N loads, respectively. This indicates that a polishing process of the LDGC surfaces occurred during wear. The LDGC surfaces were believed to have undergone a three-body polishing wear process,50 i.e., wear debris acted as a polishing media.51 Consequently, the three-body wear process, involving wear debris generated from the LDGC surfaces with a lower hardness than the alumina pins, resulted in the highest wear volumes for the unpolished surfaces (Figure 4) as well as shear-removed, plastically deformed layers (Figures 5a and 5b). In contract, two-body wear was observed in LDGC against human enamel.38 For the polished LDGC surfaces, their surface roughness increased after wear and the increase was more remarkable at 25 N load than at 5 N (Figure 3). The polished LDGC surfaces must have been damaged by sliding motions of hard alumina pins. Evidently, the wear tracks of the polished LDGC surfaces shown in Figures 6(b), 7(b) and 8(b) had the thin transfer layers.

The highly polished LDGC surfaces with 28 nm roughness did not yield the lowest friction coefficient (Figure 2). The low friction coefficients were obtained in the medium-polished (69 nm roughness) and low-polished (164 nm roughness) LDGC surfaces against the alumina pins at both 5 N and 25 N loads (Figure 2). Thereby, to achieve a minimal coefficient of friction, the optimal surface finish for LDGC surfaces was approximately 69–164 nm. In addition, the medium-polished LDGC surfaces of 69 nm roughness resulted in the lowest wear volume at 5N load (Figure 4). With respect to both friction coefficients and wear volumes, the desirable surface roughness for LDGC surfaces ranged 69–164 nm.

4.2. Contact Load effects

Higher contact loads profoundly affected the wear process, resulting in higher friction coefficients (Figure 2), higher wear volumes (Figure 4) and more damages on LDGC surfaces (Figures 5–8). This is because the increased pressures on the pin-disk contact areas yielded higher crushing and removal forces on LDGC specimens. Thus, higher wear volumes and surface damages were produced on LDGC specimens.

Although plastically deformed layers were generated on LDGC wear tracks at both 5 N and 25 N loads (Figures 5–8), the companied damage degrees were different. At 5 N low load, the low- and medium-polished LDGC surfaces yielded visibly shallower pits and much smaller scales cracks (Figures 6a and 7a) than the unpolished and high-polished surfaces (Figures 5a and 8a). At 25 N high load, all LDGC surfaces had similar wear characteristics of a combination of plastically deformed layers, cracks and smeared pits (Figures 5b, 6b, 7b and 8b). Consistent with the surface roughness results shown in Figure 3, 25 N high load produced the improved smoothness for unpolished LDGC surfaces on which less cracks were observed than the worn surfaces at 5 N low load (Figures 5a and 5b). Surprisingly, both loads resulted in large cracks on high-polished LDGC surfaces (Figure 7d).

4.3. Wear mechanisms

Our results indicate that wear mechanisms were controlled by initial surface roughness prepared for LDGC. For unpolished LDGC surfaces, a combination of abrasive and three-body wear was involved while for polished LDGC surfaces, abrasive wear dominated the wear process. Critical effects for abrasive wear include the geometry properties of hard asperities.52 Wear studies on dental ceramics also suggest that adequate surface finishing is critical to improve the friction and wear performance of zirconia.53 However, these studies lack the quantitative data for surface roughness evaluation of dental ceramics. Our quantitative roughness measurements indicate that asperity peaks on unpolished LDGC surfaces played a key role in this wear process. Wear tracks on LDGC surfaces reveal that all wear tracks had deformed and fractured layers consisting of crushing, grinding and polishing asperities (Figures 5–8). Shallow pits with sharp edges were also observed in Figures 5–8, where wear debris with ultrafine particles were found. Compared with the LDGC microstructures shown in Figure 1, all wear debris with the size ranges of 100–400 nm in Figures 5–8 are significantly smaller than the original needle-like lithium disilicate crystals. This means that lithium disilicate crystals underwent wear-induced transgranular fracture, fermentation and pulverization. These ultrafine wear particles might also have functioned as protectors for the LDGC surfaces from excessive wear by accommodating the interfacial shear stresses.46 Plastically deformed layers underwent brittle fracture penetrated by alumina pins, resulting in non-uniform depths and widths of the wear traces on LDGC surfaces. Further, highly polished LDGC surfaces were suspected to undergo more shear-induced plastic deformation companied by crack network formation (Figure 8). Thus, for the highly polished LDGC surfaces, wear was dominated by delamination wear. This indicates that highly polished LDGC surfaces may not have the best wear resistance and optimal selection of surface roughness for LDGC is essential for their applications in restorations.

Wear mechanisms were also affected by contact loads. At 5 N load, the wear process was dominated by plastic deformation on low- and medium-polished LDGC surfaces (Figures 6a and 7a). At 25 N load, the wear on the LDGC surfaces was dominated by a delaminating wear process, where numerous joining cracks after shear deformation were observed (Figures 5–8). Meanwhile, LDGC surfaces also experienced brittle fracture to form shallow pits with sharp edges due to the indentation effect caused by alumina pins.46,50 At the higher contact load, penetration shear stresses in wear areas were higher to form cracks, promoting material removal by delamination (e.g., Figure 6b).

The surface roughness of the alumina pins decreased after wear. However, the decrease was small compared to the unpolished LDGC specimens with the similar roughness. This is because the harder alumina pins had a greater resistance to wear, resulting in a much less reduction in roughness. The SEM micrograph in Figure 9b shows adhered debris on the worn alumina pin, indicating the occurrence of adhesion wear. In general, adhesion is resulted from the surface interactions and welding of asperity junctions at the sliding contact.54 The energy dispersive x-ray spectrum in Figure 9c confirmed that the top, thin layer of the wear scar on an alumina pin was formed from the wear debris generated from the glass matrix or grain boundary in both LDGC and alumina, but more from LDGC owing to its relatively low hardness. This reconfirms the occurrence of adhesion wear. This phenomenon is considered corrosion by means of mechanical action rather than chemical reaction between alumina and LDGC contact surfaces. When compressive loads are applied, the alumina-LDGC asperity junctions were plastically deformed and finally welded together due to the high contact pressure generated in the vicinities of these junctions. As sliding continues, these bonds were broken, producing cavities on LGDC surfaces shown in Figures 5–8. Abrasive particles generated from wear debris may have also possibly detached and rubbed against LDGC surfaces, contributing to wear. In Figure 9c, lithium element was, however, not found in the spectrum. This is because with current energy dispersive x-ray spectroscopy, Li, together with H and He cannot be detected. Secondary ion mass spectrometry is a sensitive technique for the analysis of Li, which will be applied in the future study.

It should be noted that the oral environmental conditions are extremely complex to replicate their contributions to the wear of dental materials.34 The extensively published work on oral tribology has improved our understanding of dental wear mechanisms and helped the development of wear-resistant restorative materials.34, 55 However, an appropriate wear testing device and standardized method have not yet been developed in restorative dentistry.34, 39, 44, 55 Numerous wear testing devices have been developed to predict the clinical performance of many dental biomaterials, but they differ in the degree of complexity and used different variables including force, contact geometry, displacement, lubricant, antagonist, and cycles.34, 55, 56 Thus, it is unlikely to conduct cross-comparison among all polished wear testing data. For instance, in the wear performance of dental ceramics after grinding and polishing,57 no wear was found for polished (200 nm roughness), ground (850 nm roughness) and repolished (120 nm roughness) zirconia in two-body wear against human enamel. This test was performed in a chewing simulator in a pin-on-disk design for 1.2×105 mastication cycles at 50 N, 1.2 Hz.57 This study shows that the repolished zirconia had a better wear resistance than porcelains but the best polishing conditions were not provided. Additionally, in dental practice, most zirconia restorations are veneered with porcelains so that zirconia cores seldom make direct contacts with enamel. Another interesting investigation was conducted on the influence of roughness on wear transition in glass-infiltrated alumina. It reveals that the wear volume of glass-infiltrated alumina linearly increased with the initial surface roughness in a pin-on-disk testing against 10 nm alumina balls at the conditions similar to our current study.50 The coefficients of friction were decreased with the improved roughness.50 In comparison, LMGC studies reveals more complex tribological properties under the wear testing conditions applied.

What do our results mean to clinical application of LDGC for dental restorations? Surface preparation of dental ceramics is critical to long-term successes of ceramic restorations. This investigation has contributed to a better understanding of the wear behaviour and mechanisms of LDGC. The findings will provide tribological insights into optimal material design and preparation of ceramic restorations for improved longevity.

5. CONCULSIONS

This work addressed effects of surface roughness and contact loads on abrasive wear of LDGC, a high-strength dental ceramic, using a pin-on-disk tribometer. It was found that both initial LDGC surface roughness and contact loads played critical roles in controlling the abrasive wear performance of LDGC with respect to the coefficients of friction, wear volumes, wear-induced surface roughness changes and wear mechanisms. Unpolished LDGC surfaces underwent a three-body wear while the polished LDGC surfaces mainly had two-body wear. Highly polished LDGC surfaces with 28 nm roughness did not achieve the lowest coefficient of friction and wear volume. Delamination, plastic deformation, brittle fracture and adhesion occurred in the wear process for LDGC, resulting in wear layers containing plastically deformed areas, crack networks and shallow pits. This study contributed to the fundamental knowledge on proper surface preparation for restorative applications of LDGC to achieve long-term wear resistance in clinical services.

Acknowledgments

PZ thanks Scientia Professor Liangchi Zhang and Dr. Jingping Wu of School of Mechanical & Manufacturing Engineering at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) and the Mark Wainwright Analytical Center of UNSW for technical assistance. LY thanks Drs. Kevin Blake and Shane Askew of the JCU Advanced Analytical Center for technical discussion. This study was supported by the James Cook University (JCU) Collaboration Grants Scheme and the US National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grant 2R01 DE017925.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Della Bona A, Kelly JR. The clinical success of all-ceramic restorations. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139 (suppl 4):8S–13S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2008.0361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Conrad HJ, Seong WJ, Pesun IJ. Current ceramic materials and systems with clinical recommendations: a systematic review. J Prosthet Dent. 2007;98:389– 404. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(07)60124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson JY, Stoner BR, Piascik JR. Ceramics for restorative dentistry: critical aspects for fracture and fatigue resistance. Mater Sci Eng C. 2007;27:565–569. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rekow ED, Silva NRFA, Coelho PG, Zhang Y, Guess P, Thompson VP. Performance of dental ceramics: Challenges for improvements. J Dent Res. 2011;90:937–952. doi: 10.1177/0022034510391795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang Y, Lee JJ-W, Srikanth R, Lawn BR. Edge chipping and flexural resistance of monolithic ceramics. Dent Mater. 2013;29:1201–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin L, Lymer R, Billau N, Peng Z, Stoll R. Damage morphology produced in low-cycle high-load indentations of feldspar porcelain and leucite glass ceramic. J Mater Sci. 2013;48:7902–7912. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yin L, Stoll R. Ceramics in restorative dentistry. In: Low IM, editor. Advances in Ceramic Matrix Composites. Woodhead Publishing Limited; Cambridge, UK: 2014. pp. 624–655. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadowsky SJ. An overview of treatment considerations for esthetic restorations: a review of the literature. J Prosthet Dent. 2006;96:433–442. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yin L. Property-process relations in clinical abrasive adjusting of dental ceramics. J Mech Behavior Biomed Mater. 2012;16:55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yin L, Song SF, Song YL, Huang T, Li J. An overview of in vitro abrasive finishing and CAD/CAM of bioceramics in restorative dentistry. Int J Machine Tool Manufact. 2006;46:1013–1026. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yin L, Jahanmir S, Ives LK. Abrasive machining of porcelain and zirconia with a dental handpiece. Wear. 2003;255:975–989. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chai H, Lee JJ-W, Mieleszko AJ, Chu SJ, Zhang Y. On the interfacial fracture of porcelain/zirconia and graded zirconia dental structures. Acta Biomater. 2014;8:3756–3761. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guess PC, Schultheis S, Bonfante EA, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG, Ferencz JL, Silva NRFA. All-ceramic systems: laboratory and clinical performance. Dent Clin N Am. 2011;55:333– 352. doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2011.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guess PC, Zavanelli RA, Silva NR, Bonfante EA, Coelho PG, Thompson VP. Monolithic CAD/CAM lithium disilicate versus veneered Y-TZP crowns: comparison of failure modes and reliability after fatigue. Int J Prosthodont. 2010;23:434–442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Swain MV. Unstable cracking (chipping) of veneering porcelain on all-ceramic dental crowns and fixed partial dentures. Acta Biomater. 2009;5:1668–1677. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tinscher J, Mautsch W, Augthun M, Spiekermann H. Fracture resistance of lithium disilicate-, alumina-, and zirconia-based three-unit fixed partial dentures: a laboratory study. Int J Prosthodont. 2001;14:231–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang Y, Pajares A, Lawn BR. Fatigue and damage tolerance of Y-TZP ceramics in layered biomechanical systems. J Biomed Mater Res Part B Appl Biomater. 2004;71:166–171. doi: 10.1002/jbm.b.30083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baldassarri M, Zhang Y, Thompson VP, Rekow ED, Stappert CFJ. Reliability and failure modes of implant-supported zirconia-oxide fixed dental prostheses related to veneering techniques. J Dent. 2011;39:489–498. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2011.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baldassarri M, Stappert CFJ, Wolff MS, Thompson VP. Residual stresses in porcelain-veneered zirconia prostheses. Dent Mater. 2012;28:873–879. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Denry I, Holloway HA. Ceramics for dental applications: a review. Matererials. 2010;3:351– 368. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Höland W, Apel E, van ‘t Hoen Ch, Rheinberger V. Studies of crystal phase formations in high-strength lithium disilicate glass–ceramics. J Non-Cryst Solids. 2006;352:4041–4050. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Höland W, Rheinberger V, Apel E, van’t Hoen C, Höland M, Dommann A, Obrecht M, Mauth C, Graf-Hausner U. Clinicla applications of glass-ceramics in dentistry. J Mater Sci Mater Med. 2006;17:1037–1042. doi: 10.1007/s10856-006-0441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Höland W, Schweiger M, Watzke R, Peschke A, Kappert H. Ceramics as biomaterials for dental restoration. Expert Rev Med Devic. 2008;5(6):29–45. doi: 10.1586/17434440.5.6.729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gehrt M, Wolfart S, Rafai N, Reich S, Edelhoff D. Clinical results of lithium-disilicate crowns after up to 9 years of service. Clin Oral Invest. 2013;17:275–284. doi: 10.1007/s00784-012-0700-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wolfart S, Eschbach S, Scherrer A, Kern M. Clinical outcome of three-unit lithium-disilicate glass–ceramic fixed dental prostheses: Up to 8 years results. Dent Mater. 2009;25(9):e63–e71. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fasbinder DJ, Dennison JB, Heys D, Neiva G. A clinical evaluation of chairside lithium disilicate CAD/CAM crowns: a two-year report. J Am Dent Assoc. 2010;141(Suppl 2):10S–4S. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2010.0355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Valenti M, Valenti A. Retrospective survival analysis of 261 lithium disilicate crowns in a private general practice. Quintessence Int. 2009;40:573–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kern M, Sasse M, Wolfart S. Ten-year outcome of three-unit fixed dental prostheses made from monolithic lithium disilicate ceramic. J Am Dent Assoc. 2012;143:234–240. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2012.0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Preis V, Hahnel S, Kolbeck C, Behrend D, Warkentin M, Handel G, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of dental materials: A comparison of substructure ceramics, veneering ceramics, and non-precious alloys. Adv Eng Mater. 2011;13:B432–B439. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MJ, Oh SH, Kim JH, Ju SW, Seo DG, Jun SH, Ahn JS, Ryu JJ. Wear evaluation of the human enamel opposing different Y-TZP dental ceramics and other porcelains. J Dent. 2012;40:979–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitov G, Herntze SD, Walz S, Woll K, Muecklich F, Pospiech P. Wear behaviour of dental Y-TZP ceramic against natural enamel after different finishing procedures. Dent Mater. 2012;28:909–918. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2012.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guidoni GM, Swain MC, J_ger I. enamel: from brittle to ductile like tribological response. J Dent. 2008;36:786–794. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2008.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guidoni GM, Swain MC, J_ger I. Wear behaviour of dental enamel at the nanoscale with a sharp and blunt indenter tip. Wear. 2009;266:60–68. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee A, He LH, Lyong K, Swain MV. Tooth wear and wear investigations in dentistry. J Rehab. 2012;39:217–225. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2842.2011.02257.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arsecularatne JA, Hoffman M. On the wear mechanism of human dental enamel. J Mech Behavior of Biomed Mater. 2010;3:347–356. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arsecularatne JA, Hoffman M. Ceramic-like wear behaviour of human dental enamel. J Mech Behavior of Biomed Mater. 2012;8:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2011.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schuh C, Kinast EJK, Mezzomo E, Kapczinski MP. Effect of glazed and polished surface finishes on the friction coefficient of two low-fusing ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosentritt M, Preis V, Behr M, Hahnel S, Handel G, Kolbeck C. Two-body wear of dental porcelain and substructure oxide ceramics. Clin Oral Invest. 2012;16:935–943. doi: 10.1007/s00784-011-0589-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ren L, Zhang Y. Sliding contact fracture of dental ceramics: principles and validation. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:3243–3253. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2014.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Field J, Waterhouse P, German M. Quantifying and qualifying surface changes on dental hard tissues in vitro. J Dent. 2010;38:182–190. doi: 10.1016/j.jdent.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Las Casas EB, Bstos FS, Godoy GCD, Buono VTL. Enamel wear and surface roughness characterization using 3D profilometry. Tribology Int. 2008;41:1232–1236. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lohbauer U, Müller FA, Petschelt A. Influence of surface roughness on mechanical strength of resin composite versus glass ceramic materials. Dent Mater. 2008;24:250–256. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Etman MK, Woolford MJ. Three-year clinical evaluation of two ceramic crown systems: A preliminary study. J Prosthet Dent. 2010;103:80–90. doi: 10.1016/S0022-3913(10)60010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Heintze SD, Cavalleri A, Forjanic M, Zellweger G, Rousson V. Wear of ceramic and antagonist—A systematic evaluation of influencing factors in vitro. Dent Mater. 2008;24:433–449. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2007.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hench LL, Day DE, Höland W, Rheinberger VM. Glass and Medicine. Int J Appl Glass Sci. 2010;1(Spe):104–117. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kalin M, Jahanmir S, Drazic G. Wear Mechanisms of Glass-Infiltrated Alumina Sliding Against Alumina in Water. J Am Ceram Soc. 2005;88:346–352. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kalin M, Jahanmir S, Ives LK. Effect of counterface roughness on abrasive wear of hydroxyapatite. Wear. 2002;252:679–685. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lambrechts P, Debels E, Van Landuyt K, Peumans M, Van Meerbeek B. How to simulate wear? Overview of existing methods Dent Mater. 2006;22:693–701. doi: 10.1016/j.dental.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Christian S, Julio KE, Elio M, Pereira KM. Effect of glazed and polished surface finishes on the friction coefficient of two low-fusing ceramics. J Prosthet Dent. 2005;93:245–252. doi: 10.1016/j.prosdent.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kalin M, Jahanmir S. Influence of roughness on wear transition in glass-infiltrated alumina. Wear. 2003;255:669–676. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bhushan B. Principles and Applications of Tribology. John Wiley & Sons; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rabinowicz E. Friciton and Wear of Materials. 2. Wiley; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang L, Liu Y, Si W, Feng H, Tao Y, Ma Z. Friction and wear behavior of dental ceramics against natural tooth enamel. J Euro Ceram Soc. 2012;32:2599–2606. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Basu B, Kalian M. Tribology of ceramics and composites: A materials Science Perspective. John Wiley & Sons; New jersey, USA: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhou ZR, Zheng J. Tribology of dental materials: a review. J Phys D Appl Phys. 2008;41:113001. (22pp) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Borrero-Lopez O, Pajares A, Constantino PJ, Lawn BR. A model for predicting wear rates in tooth enamel. J Mech Behavior Biomed Mater. 2014;37:226–234. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Preis V, Behr M, Handel G, Schneider-Feyrer, Hahnel S, Rosentritt M. Wear performance of dental cermaicsafer grinding and polishing treatments. J Mech Behavior Biomed Mater. 2012;10:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]