Abstract

Liposuction is one of the most frequently performed cosmetic surgeries worldwide for reshaping the body contour. Although liposuction is minimally invasive and relatively safe, it is a surgical procedure, and it carries the risk of major and minor complications. These complications vary from postoperative nausea to life-threatening events. Common complications include infection, abdominal wall injury, bowel herniation, bleeding, haematoma, seroma, and lymphoedema. Life-threatening complications such as necrotizing fasciitis, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism have also been reported. In this paper, we provide a brief introduction to liposuction with the related anatomy and present computed tomography and ultrasonography findings of a wide spectrum of postoperative complications associated with liposuction.

Keywords: Liposuction, Lipoplasty, Complication, Computed tomography

INTRODUCTION

Liposuction is one of the most common aesthetic plastic surgeries performed in both Western and Eastern countries, and the number of liposuction procedures has been increasing recently (1,2). It is usually performed for cosmetic reasons such as reshaping the body contour rather than as a treatment for obesity. Because liposuction is known to be a minimally invasive and safe surgery and can be performed in outpatient clinics, the associated risks can be easily overlooked (1). The overall complication rate has been reported to be in the range of 8.6-20%, and the most common complication is contour deformity, with a reported incidence of 20%, followed by seroma, hyperpigmentation, asymmetry, and hypertrophic scar (2,3). Major or lethal complications such as skin necrosis, infection, necrotizing fasciitis, pulmonary embolism, and even death have been reported in 0.02-0.25% of cases (2,4). In contrast to surgical procedures for obesity such as sleeve gastrectomy, gastric banding, and gastric bypass surgery, most radiologists and clinicians are unfamiliar with normal and abnormal postoperative findings following liposuction, in spite of the risk of minor and major complications and the high number of surgeries that are performed. In this article, we briefly review liposuction surgery and the related anatomy. We also present imaging findings of postoperative complications associated with liposuction. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital, and informed consent was waived.

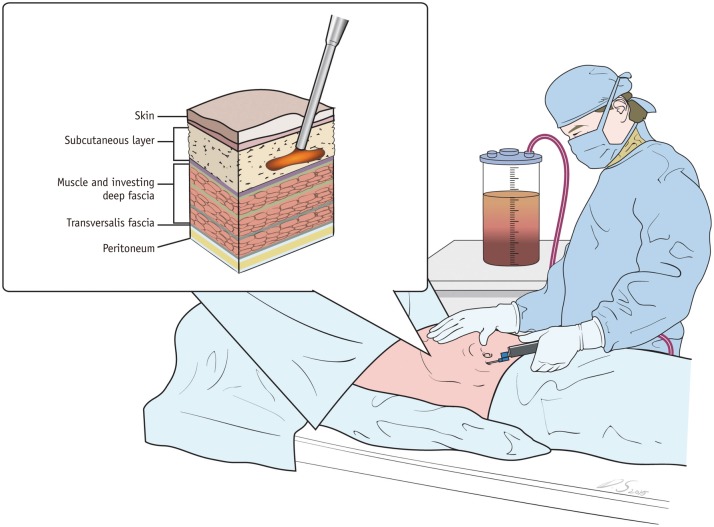

Liposuction Surgery

Suction-assisted liposuction (SAL) has been developed as a common and effective aesthetic plastic surgery since the late 1970s (5,6). After small access incisions are made in the skin, a blunt cannula is inserted through the incisions to aspirate fat from the deep subcutaneous layer (Fig. 1). The cannulae that are used are smaller than 5 mm and 2.4 mm for the body and face, respectively (6,7). A tumescent solution that consists of diluted lidocaine, epinephrine, and saline is frequently used in traditional SAL. It is introduced into the body through the cannula to provide local anaesthesia and reduce blood loss (7). A suction pump is connected to the cannula by a transparent tube (6,8). This system allows for visualising the isolated fat as it is suctioned. The operator determines the endpoint of the liposuction process by colour changes in the aspirated fat, which shifts from a pure yellow to a bloody shade. At this point, the operator inserts the cannula into a different tunnel. With the recent evolution of new techniques, various additional techniques such as laser-, power-, ultrasound-, and radiofrequency-assisted liposuction have been adapted to improve the outcomes (5,6,7). Table 1 shows the characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of various liposuction techniques (3,5,6,7,8,9).

Fig. 1. Illustration of liposuction surgery.

Blunt cannula is inserted through small incisions to aspirate fat from subcutaneous layer. Aspirated fat is transferred to suction pump through transparent tube. Operator can know amount of fat aspirated and when to end liposuction by checking amount collected in suction pump.

Table 1. Characteristics, Advantages, and Disadvantages of Various Liposuction Techniques (3,5,6,7,8,9).

| Methods | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|

| Water-assisted liposuction | ||

| Loosens fat cells by injection of pressurised fluid | Minimizes traumatic damage of surrounding soft tissue | Does not provide proper skin contraction after liposuction |

| Power-assisted liposuction | ||

| Use of rapidly vibrating cannula (where operator moves cannula around in back and forth motion in order to break down fat cells in traditional SAL technique) | Reduces patient injury | Additional costs and inconvenience to operator due to noise and vibration |

| Laser-assisted liposuction | ||

| Use of laser energy to melt fat | Reduction of intraoperative blood loss and postoperative ecchymosis | Risk of thermal injury and increased operation time |

| Ultrasound-assisted liposuction | ||

| Use of ultrasound for lipolysis of selective fat tissues by transforming electrical energy to mechanical vibration | Reduction of operation time and blood loss by cavity formation in tumescent fluid | High costs, need for larger incisions, and risk of thermal burns |

| Radiofrequency-assisted liposuction | ||

| Use of high-frequency oscillating electrical current to dissolve fat cells and to create small cavities in fatty cells | Induces immediate contractions of soft tissue and skin after suction of subcutaneous fat | Risk of thermal injury to skin and nerves |

SAL = suction-assisted liposuction

Anatomy of the Abdominal Wall

The principal anatomy of the abdominal wall comprises multiple layers: skin, subcutaneous tissue including fatty layer and Scarpa fascia, muscles and investing deep fascia, transversalis fascia, and peritoneum from exterior to interior (10,11). The primary target of liposuction is the subcutaneous layer in which the cannula is inserted. The dissected skin and subcutaneous layer can be vulnerable to microorganism infections, resulting in cellulitis, necrosis of the skin, necrotizing fasciitis, and sepsis (7,12). In addition to fat tissue, there are perforating arteries, veins, lymphatics, and nerve branches in the subcutaneous layer of the abdominal wall. Small branching vessels originate from (or are drained into) the thoracic, lumbar, intercostal, external/internal iliac, common femoral, and superior or inferior epigastric vessels (10,11). The superficial vascular structures in the subcutaneous tissues supply the tissues that are superficial to the external oblique aponeurosis and anterior rectus sheath. The deep vascular structures in the musculofascial layers the supply muscles and tissues below these layers (10,11). Vessels can be injured during liposuction, and bleeding from injured vessels may cause haematoma and even hypovolemic shock (5,13,14). Abdominal lymphatics also run the venous pathway, and an injury to the lymphatics may result in lymphoedema or seroma. Nerves that originate from the intercostal and lumbar nerves innervate between the internal oblique muscles and the transversus abdominis in a caudal and medial direction (10,11). Swelling and oedema after liposuction can compress nerves and cause sensations such as pain and numbness in the affected area (13). Longitudinal incisions can even transect nerves and cause sensory impairment at the inferior and medial levels of the injured nerves.

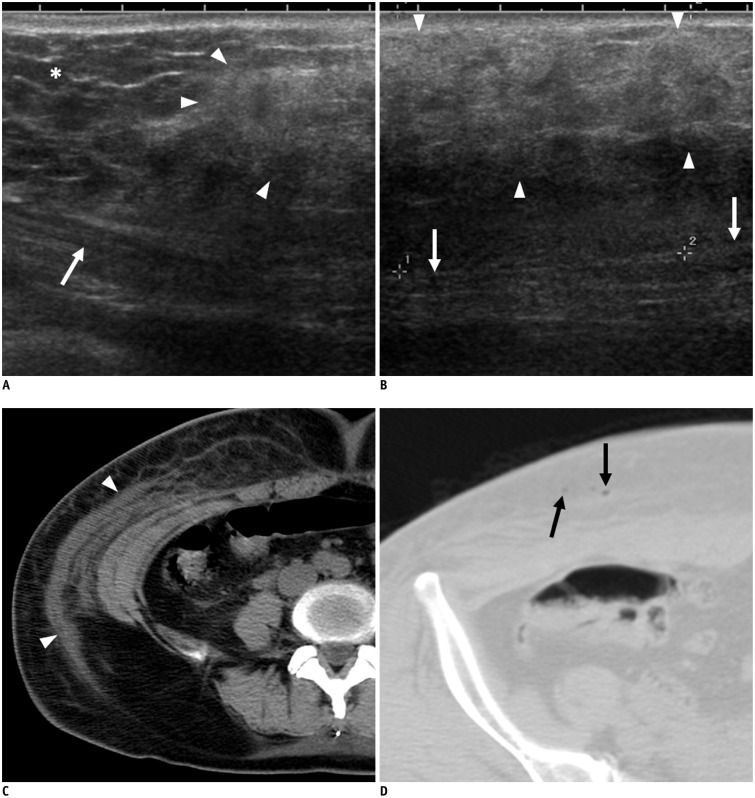

Imaging Findings of Normal Post-Liposuction Changes

During liposuction, the cannula is inserted into the subcutaneous layer, and sometimes, water or vasoconstrictor solutions are also administered. Immediately after the liposuction, the surgery site appears as a heterogeneous hyperechoic or hypoechoic mass-like lesion on ultrasonography (15). On computed tomography (CT), an infiltrative lesion with fluid collection, or lymphoedema, with or without air bubbles, can be seen in the subcutaneous layer (Fig. 2) (5,16). Thin, linear radiating lesions perpendicular to the skin may also be present (5). Cannula insertion tracks can be seen as thick linear lesions parallel to the skin (16).

Fig. 2. 53-year-old woman who underwent liposuction 3 days previously.

She had no symptoms at liposuction site or abdominal wall. A, B. On ultrasonography, heterogeneous hyperechoic area (arrowheads) compared with adjacent normal fat (asterisk) is seen in subcutaneous layer of abdominal wall. Abdominal muscle is seen below lesion (arrows). C. On non-contrast axial CT image, infiltrative lesion with fluid collection or lymphoedema is seen in subcutaneous area (arrowheads). D. Subcutaneous emphysema (arrows) is also seen in subcutaneous layer.

Complications of Liposuction

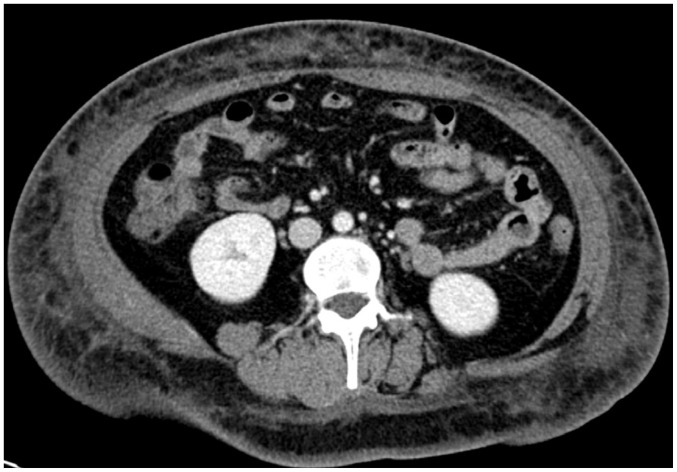

Infection

The dissected subcutaneous layer can be a good medium for bacterial growth. If the wound or instrument is contaminated, infections from cellulitis to life-threatening necrotizing fasciitis can occur after liposuction. Cellulitis is an infection of the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and manifests as skin thickening, septation of subcutaneous fat, fascial thickening, and lymph node enlargement on CT (Fig. 3) (12). Because imaging findings of uncomplicated cellulitis may be similar to normal findings immediately after liposuction, clinical diagnosis based on symptoms such as fever, local heating sensation, pain, and erythema, as well as laboratory results including elevated C-reactive protein and white blood cell count should be considered (12,17,18). Uncomplicated cellulitis is treated with antibiotics. Necrotizing fasciitis is defined as deep infection involving deep fascia with tissue necrosis. Necrotizing fasciitis is a surgical emergency, and radical surgical debridement of the necrotic tissue is the first treatment of choice (1,19). CT is the most sensitive modality for both diagnosing necrotizing fasciitis and evaluating the extent of the disease. Although the CT findings are similar to those of cellulitis, we can diagnose necrotizing fasciitis when an air bubble is noted in the muscle layer (Fig. 4) (20).

Fig. 3. 36-year-old woman presented with persisting fever for 4 days after liposuction.

On portal venous-phase CT image, diffuse fat infiltration is seen in subcutaneous layer of body along with suspicious skin thickening. She was diagnosed with cellulitis at liposuction site and treated with intravenous antibiotics after admission.

Fig. 4. 36-year-old woman who had received liposuction 2 days before presented with abdominal pain and shock.

Her blood pressure was 70 mm Hg systolic and 50 mm Hg diastolic. A. On non-contrast CT image, massive subcutaneous emphysema is seen (arrowheads). At abdominal wall incision, and staining from faecal material is seen at subcutaneous fat layer. B. During exploratory laparotomy, perforation site was detected at ileum. After resection of small bowel and massive peritoneal irrigation, retention suture was made at muscle layer. Subcutaneous fat layer and skin were not closed so that infected material could be effectively drained. C. On photograph taken during surgery, colour changes to rectus sheath are seen, which were likely attributable to inflammation (asterisk). In spite of immediate and intensive care, she died 4 days later.

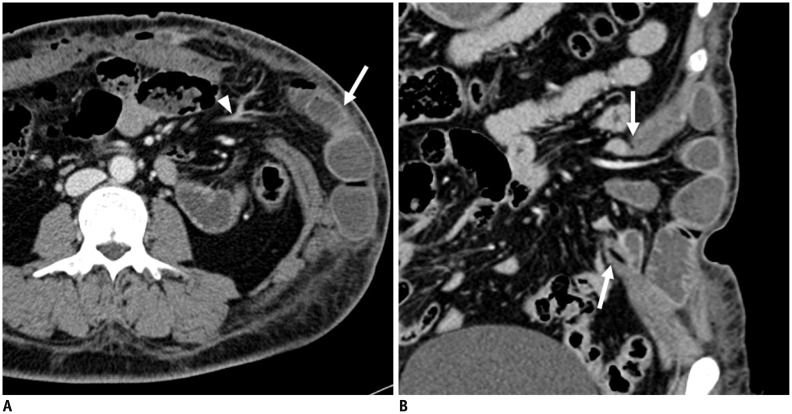

Injury to the Abdominal Wall and Internal Organs

Although the cannula is inserted into the subcutaneous layer of the abdominal wall, it can damage deeper structures such as the abdominal wall muscle or even the small bowel (5). Generally, this is because the cannula is inserted blindly without imaging guidance, and if the insertion angle of the cannula is larger, it can penetrate the abdominal muscle or peritoneum. Abdominal muscle injury can result in bowel herniation through the defect in the abdominal muscle (Fig. 5). The bowel wall can also be damaged during liposuction, resulting in bowel perforation or bowel obstruction (Fig. 6). Abdominal or bowel wall perforation is the second most common cause of mortality after liposuction (9). Rarely, damage to other internal organs such as the gallbladder, pancreas, and spleen has been reported (1,3).

Fig. 5. 39-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and left upper quadrant bulging during liposuction at local clinic.

A. Portal venous-phase axial CT images show ventral herniation of small bowel (arrow) with mesentery and associated vessels (arrowhead). Perfusion of bowel wall was preserved. B. On coronal image, full-thickness defects of abdominal wall are seen (arrows). Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed, and reduction of herniated small bowel and layer by layer closure of abdominal wall were performed.

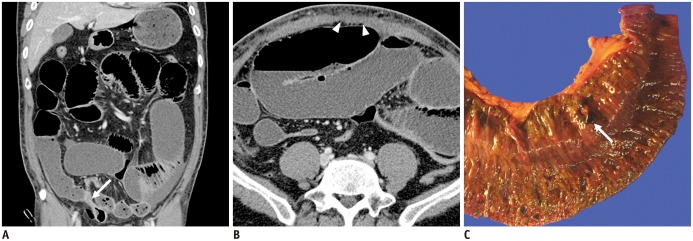

Fig. 6. 47-year-old man presented with abdominal distension for 5 days and dyspnoea for 2 days. He had undergone liposuction 5 days previously at local clinic.

A. On portal venous-phase coronal CT image, abrupt luminal narrowing of small bowel lumen (arrow) is seen. B. Proximal small bowel was diffusely dilated. Focal defect in rectus muscle (arrowheads) was also detected. On diagnostic laparotomy, perfusion was decreased in distal small bowel loop, and segmental resection of ischemic bowel loop was performed. C. Small perforation site was detected, as seen, at resected small bowel loop (arrow). There were also defects in rectus muscle, in sheath below umbilicus, and at liposuction site. Primary repair of these defects was performed during surgery. Despite undergoing emergency operation, patient did not recover from sepsis and died from multi-organ failure.

Vascular and Lymphatic Injury

Small perforating vessels in the subcutaneous layer can be injured frequently during liposuction. Bleeding from these small vessels can be controlled with vasoconstrictor solutions, which are administered during liposuction and compression dressing after the surgery (3). If complete bleeding control is not achieved or if the patient has a bleeding tendency, haematoma with or without active bleeding can occur during or after liposuction (Fig. 7) (5,14). Small lymphatic channels can also be injured during the liposuction, and lymphoedema or a seroma may develop after the surgery (Fig. 8). According to previous studies, seroma development is the second most common complication after liposuction, and the approximate incidence is 2.3-3.5% (2). Tissue trauma with extensive breaking of the fibrous tissue network may lead to a seroma or lymphoedema. Scrotal or labial lymphoedema can develop after abdominal (especially pubic fat) liposuction (Fig. 9) (21). Although appropriate compression garments and early drainage massage can improve the seroma or lymphoedema in most cases, drainage catheter insertion might be needed in long-standing cases of localised seroma (Fig. 8) (21).

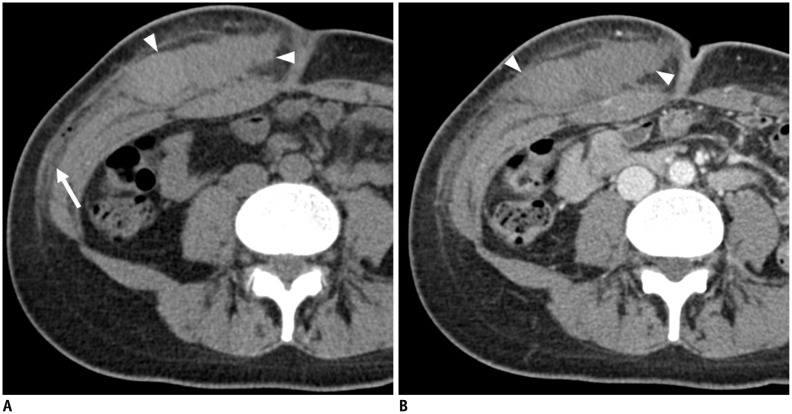

Fig. 7. 34-year-old woman who had received liposuction few hours previously presented with swelling and pain in right lower abdominal wall.

A. On non-contrast CT image, high-attenuating mass-like lesion is seen in subcutaneous layer of right abdominal wall (arrowheads). Fat infiltration is also seen in subcutaneous layer (arrow). B. On contrast-enhanced CT image, mass-like lesion (arrowheads) does not show enhancement. Contrast media extravasation was also not detected within lesion. She was diagnosed with haematoma without active bleeding in subcutaneous layer of right abdominal wall.

Fig. 8. 64-year-old woman presented with abdominal pain and right abdominal wall bulging after liposuction.

A. On axial portal venous-phase CT images, loculated fluid collection was noted in right lower abdominal wall (arrowheads). B. Fluoroscopy-guided pigtail catheter (arrow) insertion was performed. C. On follow-up CT, compete drainage of fluid collection is observed. Inserted catheter, which was located within fluid collection, is visible (arrow).

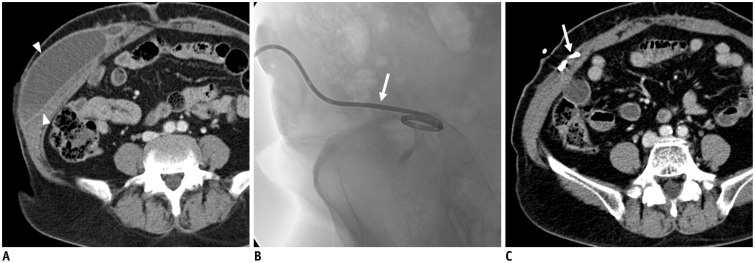

Fig. 9. 36-year-old man who had undergone liposuction 3 days previously presented with scrotal swelling that had persisted for 2 days.

A. On portal venous-phase CT image, diffuse infiltration, possibly caused by liposuction, is seen (arrowheads). B. On axial CT images of lower pelvis, diffuse subcutaneous oedema (arrow) is noted in scrotum. He was diagnosed with lymphoedema of scrotum caused by liposuction.

Pulmonary Embolism and Deep Vein Thrombosis

Venous thromboembolism is one of the most common complications observed after surgery. The overall incidence of deep vein thrombosis in patients with prophylaxis was 3-20% after general surgery and 14-41% after total hip replacement (22). The incidence of pulmonary embolism and/or deep venous thrombosis after liposuction is only < 1%, but it accounts for 23% of post-operative mortalities and is the most common cause of death following liposuction (3,9,21). Although there are relatively few incidents of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis after liposuction, many attempts have been made to predict the risk of post-procedural pulmonary embolism and/or deep venous thrombosis as has been done for other major surgeries. The margin for rationalising risk versus benefit is considered smaller for liposuction because it is performed for cosmetic reasons and is optional rather than mandatory or life-saving (23). The mechanism of venous thromboembolism after liposuction is similar to its mechanisms after other surgeries including vascular injury during surgery, increased blood viscosity caused by fluid loss, and decreased blood flow caused by restricted movement (24). In terms of pulmonary embolism, both conventional thromboembolism and fat embolism can occur after liposuction, similar to what happens after long bone surgery (4,25). Suctioning a large volume of fat, prolonged operation time, and concomitant surgery are known as risk factors (1,3). According to a previous study, early mobilisation, a compression device for legs, low molecular weight heparin, or resection of less than 1500 g of tissue volume could reduce the possibility of pulmonary embolism and/or deep vein thrombosis (9). On CT, pulmonary embolism manifests as an intraluminal filling defect, cut-off of involved vascular enhancement, and an enlarged occluded vessel (Fig. 10) (25). Deep vein thrombosis can be seen as a filling defect with upstream venous dilatation and perivenous or distal body part oedema (25).

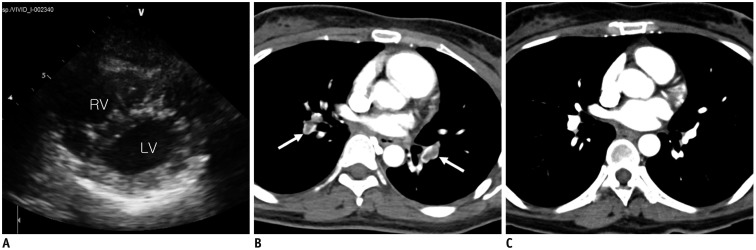

Fig. 10. 43-year-old woman presented with dyspnoea and dizziness. She had undergone liposuction at trunk and both thighs 2 days previously.

A. On parasternal short axis view of emergency portable echocardiography, mild pulmonary hypertension (D shape of left ventricle [LV], estimated right ventricular [RV] systolic pressure = 45 mm Hg) was suspected. B. On contrast-enhanced axial CT image, filling defects are seen in both pulmonary arteries (arrows), suggesting pulmonary embolism. She underwent thrombolytic therapy using heparin and tissue plasminogen activator. C. On follow-up chest CT 6 months later, pulmonary embolism was found to have completely resolved.

Shock and Acute Renal Failure

In liposuction surgery, careful intraoperative and postoperative fluid management is crucial for preventing volume-related complications. The tumescent liposuction technique induces volume overloading and pulmonary oedema (3). Hypovolemic shock can occur if a large volume of fat has been removed because of the increased damage to small subcutaneous blood vessels and lymphatic vessels, which results in bleeding or seroma (Fig. 11) (26,27). Proper patient monitoring during liposuction and appropriate fluid resuscitation should be carried out (5).

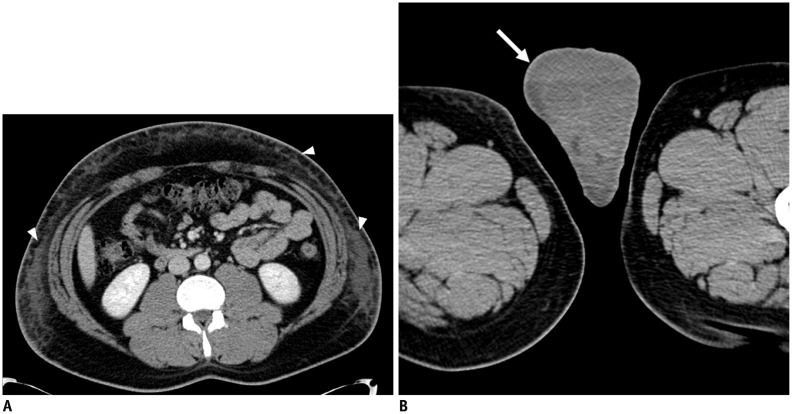

Fig. 11. 26-year-old female who had received liposuction few hours before visiting hospital presented with abdominal pain and vomiting.

Because BUN and serum creatinine showed increased levels of 35.5 mg/dL (normal range: 7.3-20.5 mg/dL) and 2.6 mg/dL (normal range: 0.49-0.91 mg/dL) on laboratory examination, only non-contrast CT scan was performed. On axial CT image, diffuse subcutaneous emphysema was seen (arrowheads). Both kidneys showed oedematous change without hydronephrosis. Patient was diagnosed with pre-renal acute renal failure. After intravenous administration of fluid, her renal function recovered without sequelae.

CONCLUSION

Although liposuction is a minimally invasive surgery, a number of different complications can occur. Subcutaneous emphysema and fat infiltration with fluid collection may be normal findings immediately after liposuction if the patient has no other relevant symptoms. Common complications include infection, abdominal wall injury, bowel herniation, bleeding, haematoma, seroma, lymphoedema, pulmonary embolism, and deep vein thrombosis. Pulmonary oedema and shock can develop if the fluid management is not appropriate during the surgery. The severity of complications can vary from simple postoperative nausea to mortality. Because liposuction is one of the most frequently performed cosmetic surgeries worldwide, radiologists will benefit from the improved ability to interpret images of possible complications by becoming familiar with normal and abnormal post-surgical findings.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dong-Su Jang, B.A. (Research Assistant, Department of Anatomy, Yonsei University College of Medicine, Seoul, Korea), for his help with the figures.

Footnotes

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (NRF-2013R1A1A2009391 and NRF-2014R1A1A2057091).

References

- 1.Lehnhardt M, Homann HH, Daigeler A, Hauser J, Palka P, Steinau HU. Major and lethal complications of liposuction: a review of 72 cases in Germany between 1998 and 2002. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:396e–403e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318170817a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim YH, Cha SM, Naidu S, Hwang WJ. Analysis of postoperative complications for superficial liposuction: a review of 2398 cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:863–871. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318200afbf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stephan PJ, Kenkel JM. Updates and advances in liposuction. Aesthet Surg J. 2010;30:83–97. quiz 98-100. doi: 10.1177/1090820X10362728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grazer FM, de Jong RH. Fatal outcomes from liposuction: census survey of cosmetic surgeons. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:436–446. discussion 447-448. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200001000-00070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank SJ, Flusberg M, Friedman S, Swinburne N, Sternschein M, Wolf EL, et al. CT appearance of common cosmetic and reconstructive surgical procedures and their complications. Clin Radiol. 2013;68:e72–e78. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2012.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shridharani SM, Broyles JM, Matarasso A. Liposuction devices: technology update. Med Devices (Auckl) 2014;7:241–251. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S47322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lipoadvisor. Lipotite/BodyTite. lipoadvisor.com Web site. [Accessed June 3, 2015]. http://www.lipoadvisor.com/lipotite-bodytite/

- 8.Matarasso A, Levine SM. Evidence-based medicine: liposuction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1697–1705. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a807cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sterodimas A, Boriani F, Magarakis E, Nicaretta B, Pereira LH, Illouz YG. Thirtyfour years of liposuction: past, present and future. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2012;16:393–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rozen WM, Ashton MW, Taylor GI. Reviewing the vascular supply of the anterior abdominal wall: redefining anatomy for increasingly refined surgery. Clin Anat. 2008;21:89–98. doi: 10.1002/ca.20585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grevious MA, Cohen M, Shah SR, Rodriguez P. Structural and functional anatomy of the abdominal wall. Clin Plast Surg. 2006;33:169–179. v. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fayad LM, Carrino JA, Fishman EK. Musculoskeletal infection: role of CT in the emergency department. Radiographics. 2007;27:1723–1736. doi: 10.1148/rg.276075033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Liposuction: What are the risks or complications? FDA.com Web site. [Last updated January 16, 2015]. [Accessed June 3, 2015]. http://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ProductsandMedicalProcedures/SurgeryandLifeSupport/Liposuction/ucm256139.htm.

- 14.Lim H, Kim HJ, Cho YS. Active bleeding in abdominal wall developing after liposuction. Emerg Med J. 2008;25:814. doi: 10.1136/emj.2008.057976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwak JY, Lee SH, Park HL, Kim JY, Kim SE, Kim EK. Sonographic findings in complications of cosmetic breast augmentation with autologous fat obtained by liposuction. J Clin Ultrasound. 2004;32:299–301. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank SJ, Flusberg M, Friedman S, Sternschein M, Wolf EL, Stein MW. Aesthetic surgery of the buttocks: imaging appearance. Skeletal Radiol. 2014;43:133–139. doi: 10.1007/s00256-013-1753-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shin SU, Lee W, Park EA, Shin CI, Chung JW, Park JH. Comparison of characteristic CT findings of lymphedema, cellulitis, and generalized edema in lower leg swelling. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;29(Suppl 2):135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10554-013-0332-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chung YE, Kim YE, Park I, You JS. Subcutaneous emphysema after carbon dioxide injection. J Emerg Med. 2014;47:e89–e90. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakkarainen TW, Kopari NM, Pham TN, Evans HL. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51:344–362. doi: 10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chaudhry AA, Baker KS, Gould ES, Gupta R. Necrotizing fasciitis and its mimics: what radiologists need to know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2015;204:128–139. doi: 10.2214/AJR.14.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dixit VV, Wagh MS. Unfavourable outcomes of liposuction and their management. Indian J Plast Surg. 2013;46:377–392. doi: 10.4103/0970-0358.118617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geerts WH, Heit JA, Clagett GP, Pineo GF, Colwell CW, Anderson FA, Jr, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism. Chest. 2001;119(1 Suppl):132S–175S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.132s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition) Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Esmon CT. Basic mechanisms and pathogenesis of venous thrombosis. Blood Rev. 2009;23:225–229. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han D, Lee KS, Franquet T, Müller NL, Kim TS, Kim H, et al. Thrombotic and nonthrombotic pulmonary arterial embolism: spectrum of imaging findings. Radiographics. 2003;23:1521–1539. doi: 10.1148/rg.1103035043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cantarelli J, Godoy MF. Safe limits for aspirate volume under wet liposuction. Obes Surg. 2009;19:1642–1645. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9958-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Di Martino M, Nahas FX, Barbosa MV, Montecinos Ayaviri NA, Kimura AK, Barella SM, et al. Seroma in lipoabdominoplasty and abdominoplasty: a comparative study using ultrasound. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;126:1742–1751. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181efa6c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]