Abstract

Since the introduction of the term “gut-liver axis”, many studies have focused on the functional links of intestinal microbiota, barrier function and immune responses to liver physiology. Intestinal and extra-intestinal diseases alter microbiota composition and lead to dysbiosis, which aggravates impaired intestinal barrier function via increased lipopolysaccharide translocation. The subsequent increased passage of gut-derived product from the intestinal lumen to the organ wall and bloodstream affects gut motility and liver biology. The activation of the toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) likely plays a key role in both cases. This review analyzed the most recent literature on the gut-liver axis, with a particular focus on the role of TLR-4 activation. Findings that linked liver disease with dysbiosis are evaluated, and links between dysbiosis and alterations of intestinal permeability and motility are discussed. We also examine the mechanisms of translocated gut bacteria and/or the bacterial product activation of liver inflammation and fibrogenesis via activity on different hepatic cell types.

Keywords: Gut microbiota, Dysbiosis, Toll-like receptor 4, Gut motility, Lipopolysaccharide tolerance, Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, Chronic hepatitis, Intestinal barrier function, Liver fibrosis

Core tip: Liver disease is associated with significant changes in intestinal microbiota, but whether liver disease modifies the complement of gut bacteria or dysbiosis causes liver disease is not clearly understood. This review outlines current knowledge on the gut-liver axis, with a particular focus on the role of toll-like receptor 4 activation in functional gastrointestinal disorders, liver inflammation and fibrosis.

INTRODUCTION

The term gut-liver axis was introduced approximately 40 years ago, when Volta et al[1] described the production of IgA antibodies directed against intestinal microorganisms and food antigens in liver cirrhosis. The functional link between the gut and liver has been extensively investigated since this first report[1]. Intestinal microbiota, barrier function and immune responses that link the gut and liver are intriguing and promising research topics.

Growing evidence demonstrates that gut microbiota play an important role in the gut-liver axis[2]. Disturbances in gut microbiota composition may contribute to many diseases and affect local and remote organ systems[3]. Several conditions are associated with specific microbial patterns and/or leaky gut. These disorders range from intestinal diseases, such as irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel diseases, to numerous extra-intestinal diseases[3], including diseases that affect the liver[4]. The intestinal mucosa exhibits impaired barrier function in the presence of abnormal microbiota, such as increased intestinal permeability and endotoxin translocation, with the subsequent increased passage of waste materials from the intestinal lumen to the organ wall and bloodstream[2,5]. The gut epithelium is a natural barrier that allows the selective entry of substances present in the lumen and avoids the entry of harmful elements, including bacteria and their bio-products[6].

Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are a family of highly conserved receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns and allow the host to recognize bacteria, mycobacteria, yeast membrane/wall components and several gut-derived products. TLR-4 is one of the most intriguing of these receptors because it plays a key role in innate immunity by triggering inflammatory responses. TLR-4 initiates innate immune responses via nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB) when it is activated by its primary ligand, Gram-negative bacterial lipopolysaccharides (LPS), which results in the transcription of several genes that encode inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and antimicrobial agents[7,8].

This review analyzed the most recent literature on the gut-liver axis, with a particular focus on the role of TLR-4 activation. First, we evaluated the evidence that links liver disease with the condition of dysbiosis. Second, we discuss the links between dysbiosis and alterations in intestinal permeability and motility. Finally, we examine the mechanisms of translocated gut bacteria and/or the bacterial product activation of liver inflammation and fibrogenesis via activity on different hepatic cell types.

DYSBIOSIS DURING CHRONIC LIVER DISEASE AND CIRRHOSIS

Liver disease is associated with significant qualitative and quantitative changes in intestinal microbiota, which is defined as “dysbiosis”. Dysbiosis is directly involved in the pathogenesis of several different forms of hepatic injury and many complications of advanced cirrhosis. Whether liver disease modifies the complement of gut bacteria or dysbiosis causes liver disease is not clearly understood. Existing evidence supports the need to contextualize the argument within the etiology of liver disease. Conversely, advanced liver disease is associated with dysbiosis that is independent from the original cause of hepatic damage. The hypothesis of a vicious circle in which microbiota alterations are supported by cirrhosis, which contributes to many cirrhosis complications seems appropriate and well structured.

Most of the research on dysbiosis during chronic liver disease investigated non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Qualitative and quantitative dysbiotic changes are clearly documented during NAFLD in patients with simple fatty liver and non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). NAFLD patients exhibit a high prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth[9,10], and microbial samples from NAFLD and NASH patients exhibit a significantly lower proportion of members of the Ruminococcaceae family than healthy subjects[11]. Some conflicting results emerged in studies that compared the microbiota between NAFLD and NASH patients, and further studies are anticipated on this subject.

The feeding of a high-fat/high-polysaccharide or a calorie-restricted diet to wild-type mice significantly alters microbial taxonomic composition in experimental models[12,13], and gut microbiota exacerbate NAFLD development via several different mechanisms. First, gut microbes participate in calorie extraction from food and regulate obesity and its complications, including NAFLD. Human enzymes cannot degrade most complex carbohydrates and plant polysaccharides, which are fermented in the colon by intestinal microbes. The resultant short-chain fatty acids account for approximately 10% of daily energy intake[14] and stimulate de novo lipogenesis[15]. The intestinal microflora is also responsible for the increased endogenous ethanol production that is observed during NAFLD. An age-related increase in breath ethanol content was reported in ob/ob mice, and neomycin treatment abolished this effect[16]. Increased systemic ethanol levels were also confirmed in NASH patients[17], which may contribute to hepatocyte trygliceride accumulation and reactive oxygen species production. Bacterial conversion of dietary choline into methylamines experimentally produced similar effects of choline-deficient diets and caused NASH[18]. More recently, gut microbiota, which are responsible for the conversion of cholic and chenodeoxycholic acid into secondary bile acids, were suggested to control lipid and glucose metabolism through the regulation of bile acid pools. Bile acids also function as signaling molecules and bind to cellular receptors. For example, bile acid synthesis controls the activation of nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor and the Takeda G-protein-coupled receptor 5[19,20], which are strongly implicated in the modulation of glucose metabolism[21,22]. Hepatotoxic bacterial products that pass across a dysregulated intestinal barrier trigger liver damage, as discussed below, and provoke systemic inflammation and insulin resistance[23], which is a primary event in NAFLD pathogenesis. Circulating levels of LPS, which is a component of the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, are elevated in rodent NAFLD[24,25] and NAFLD patients[26,27].

Research on the role of the microbiome in alcoholic liver disease is not as advanced as NAFLD, but dysbiosis is clearly associated with alcohol-induced liver damage. Significant microbial alterations were observed in the Tsukamoto-French model of alcoholic liver disease in mice[28], and Lactobacilli administration reduced the features of alcoholic liver disease in several animal models[29,30]. Significant changes in the composition of the microbiome are also observed in alcoholic patients, which is consistent with these experimental results[31,32]. There are several mechanisms by which alcohol may contribute to dysbiosis. Commensal flora produce and metabolize ethanol, and alcohol intake may influence the complement of bacteria. Alcohol also produces intestinal dysmotility, alters gastric acid secretion and impairs the intestinal innate immune response[33].

Dysbiosis is closely associated with advanced liver disease, e.g., liver cirrhosis. An apparent increase in potentially pathogenic bacteria occurs during cirrhosis independently of the etiology of liver disease, with a greater abundance of Gram-negative taxa (Enterobacteriaceae, Bacteroidaceae)[34,35]. Similar to alcohol abuse, impaired intestinal motility and innate immunity may represent a basis for the dysbiosis that is observed during cirrhosis[36]. Cirrhotic patients are frequently exposed to hospitalization, antibiotics and dietary modifications, which are potential factors associated with alterations in the intestinal microbiome.

DYSBIOSIS: BARRIER DAMAGE, BACTERIAL TRANSLOCATION AND INTESTINAL DYSMOTILITY

Experimental models suggest that dysbiosis itself contributes to intestinal inflammation and mucosal leakage, which favors the translocation of several inflammatory bacterial products[37,38]. Intestinal decontamination with non-absorbable antibiotics also significantly reduces intestinal inflammation and permeability[38].

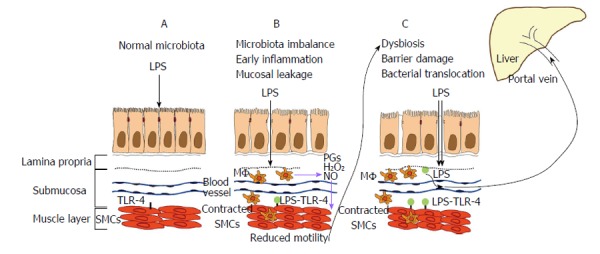

Intestinal barrier damage allows bacterial translocation, which is defined as the migration of viable microorganisms and microbial products (e.g., LPS, lipoteichoic acid, bacterial DNA) across the intestinal barrier, from the intestinal lumen to mesenteric lymph nodes and other extra-intestinal organs and sites[39]. The translocation of viable bacteria may induce “spontaneous” bacterial infections in some cases, such as the spontaneous bacterial peritonitis that is observed during cirrhosis. The translocation of bacterial products that enter the systemic circulation via the portal vein and activate inflammatory pathways of hepatic cells contributes to the progression of liver damage in other cases, as discussed below. Viable microbes and bacterial fragments entering the systemic circulation via the portal vein or following the enteric lymphatic drainage trigger a proinflammatory state by provoking the release of cytokines, such as tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-1β, which contributes to the hyperdynamic circulation and portal hypertension that are typical of advanced liver cirrhosis[40]. Recent evidence suggests that intestinal barrier damage is due to a microbial imbalance that influences gut motility[41]. The observations of intestinal dysmotility in germ-free animals further suggest that microbiota play a crucial role in the modulation of intestinal motility[42]. TLRs may explain how microbiota act on gut motility and the gut-liver axis because TLR activation during conditions of impaired intestinal barrier mediates intestinal and liver disorders. Intestinal disorders that are associated with impaired motility may be caused by intestinal dysbiosis[41], which further increases intestinal permeability and the translocation of bacterial substances, especially LPS, that may reach the liver[5] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The results of intestinal disorders that are associated with impaired motility. A: Normal conditions with intestinal mucosa tolerance; B: In the presence of microbiota imbalance, intestinal mucosa is characterized by a leak and mild inflammatory infiltrate. The subsequent passage of modest quantities of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) induces activation of resident macrophages (MΦ) with the release of inflammatory mediators, such as prostaglandins (PGs) and nitric oxide (NO). LPS can also reach the muscle layer and bind to smooth muscle cell (SMC) toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4). Both conditions cause morpho-functional changes of SMCs. The reduced intestinal motility further induces intestinal microbiota imbalance, which leads to dysbiosis; C: Dysbiosis induces barrier damage and relevant bacterial and LPS translocation. The large amount of translocated LPS reaches the blood vessels through the portal vein and reaches the liver.

The importance of aberrant intestinal microbiota in the pathogenic mechanisms of several gastro-intestinal diseases was raised previously, in addition to its health-inducing effects[2]. Commensal microbiota provides beneficial effects, including neuroimmune and pain modulation, and a possible effect on intestinal motility modulation. Polymicrobial sepsis induces a complex inflammatory response within the intestinal muscularis with the recruitment of leukocytes and the production of mediators that inhibit intestinal muscle function[43]. Therefore, the intestine is a source of bacteremia and an important target of bacterial products that affect intestinal motility[43]. Barbara et al[42] suggested in a recent paper that one of the possible mechanisms of microbiota influence on gut motor function occurs through the release of bacterial substances and the effects of mediators released by the gut immune response[42]. These inflammatory changes are partially determined by IL-1β mucosal expression, which is higher in patients suffering from post-infective irritable bowel syndrome (PI-IBS) than in patients without post-infectious symptoms[44]. Patients with IBS present increased IL-1β expression by peripheral blood mononuclear cells[45], and prolonged exposure to IL-1β alters neurotransmitter and electrically induced Ca2+ responses in the myenteric plexus[46]. The immune response also includes the release of histamine, tryptase and prostaglandins by mucosal-activated mast cells in PI-IBS[41] or activated macrophages during sepsis. Increased mucosal permeability was widely demonstrated during the course of sepsis and cases of severe mucosal inflammation[5], and impairment of contraction in these conditions seems to be related to the activation of normally quiescent intestinal muscularis macrophages by LPS or inflammatory mediators released by the mucosa[47-49]. Activated macrophages secrete several mediators, including prostaglandins, H2O2, cytokines and nitric oxide. Many of these mediators also alter the kinetic properties of smooth muscle cells (SMCs)[49-51]. Cyclooxygenase (COX)-1 and COX-2 are expressed in the neuromuscular compartment of the human colon, and these enzymes appear to modulate the cholinergic excitatory control of colonic motility at prejunctional and postjunctional sites, respectively[52]. IL-1β induces a decrease in tonic contraction in rat mesenteric lymphatic muscle cells in a COX-2 dependent manner via prostaglandin E2[53].

Scirocco et al[54] demonstrated the constitutive expression of functionally active TLR-4 on primary human colonic SMCs in an in vitro model. Notably, exposure of SMCs to LPS caused contractile alterations[54]. This result suggests that the gastrointestinal dysmotility that occurs during acute infection is related to inflammation and a direct effect of circulating LPS on SMCs. TLR-4 activation following LPS binding leads to NF-κB activation, which participates in oxidative-dependent transcriptional changes in SMCs that modify the agonist-induced contraction[49,54]. LPS may also directly affect muscle cell contractility via alterations in electro-mechanical coupling[54], which could trigger a wide cascade of intracellular events that modify SMC integrity and function. Our group recently demonstrated that acute exposure of the human colonic mucosa to pathogenic LPS[49] impairs muscle cell contractility, and this effect was due to LPS translocation, which directly affects smooth muscle contractility, or the mucosal production of free radicals and inflammatory mediators that reach the muscle layer[49].

Notably, modulation of the intestinal microflora balance using probiotics likely plays an important role in the treatment and prevention of various gastrointestinal disorders[55]. The specific mechanisms underlying probiotic efficacy are not clearly elucidated, but most gastrointestinal diseases in which probiotics exhibit efficacy are associated with non-specific alterations of gastrointestinal motility, which suggests that the modulation of intestinal motility is another possible mechanism for the benefits of probiotic[55]. For example, Lactobacillus paracasei attenuated persistent muscle hypercontractility of jejunal strips in an animal model of PI-IBS[56], and Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus, but not Streptococcus, alleviated visceral hypersensitivity and recovered intestinal barrier function and inflammation in a recent study in the PI-IBS mouse model, which correlated with an increase in tight junction proteins[57], such a claudin-1 and occludin. One of the mechanisms that underlies the altered permeability in IBS includes changes in the expression, localization and function of tight junctions[58]. Decreased levels of zonule occludin-1 (ZO-1) protein expression and disruption of claudin-1, occludin and ZO-1 expression were found in the apical region of the enterocytes during the course of IBS[59,60]. An increased risk of developing PI-IBS was also conferred by single nucleotide polymorphisms in the that gene encodes the tight junction protein E-cadherin[61].

Our group demonstrated that exposure of human colonic mucosa to Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG) may affect smooth muscle contraction, suggests that the modulation of muscle contractility represents a possible mechanism of action of these bacteria[62]. Notably, LGG acts through the direct activation of the Gram-positive sensing TLR-2, which is expressed on the surface of human colonic SMCs. We recently demonstrated that the surface expression of TLR-2 in resting cells was significantly decreased in cells exposed to LGG. This reduction in available receptors for monoclonal anti-TLR-2 binding further suggests the occurrence of an interaction of LGG with TLR-2 receptors. TLR-2 activation likely induces transitory myogenic changes with alterations in morpho-functional parameters in muscle tissue and isolated SMCs[63]. TLR-2 activates an intrinsic myogenic response that likely counteracts the damage that is induced by the pro-inflammatory burst from pathogen LPS on human gastrointestinal smooth muscle[63]. LGG likely protects human SMCs from LPS-induced damage via LGG binding to TLR-2, and TLR-2 activation leads to IL-10-mediated anti-inflammatory effects.

TLR-4-EXPRESSING CELLS AND SIGNALING IN THE LIVER

Inflammation during chronic liver damage correlates with fibrosis progression, but the molecular mechanism that links inflammation and fibrosis are not definitively understood. Several factors that participate in inflammation and liver fibrosis at the molecular and cellular levels were mentioned, regardless of the specific etiology involved. One of the pathways that has attracted the most attention in recent years as the putative link between liver inflammation and fibrosis is regulated by TLR-4 activation.

Several cell types express TLR-4 in the liver, including Kupffer cells, hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), biliary epithelial cells, hepatocytes and liver sinusoidal endothelial cell (LSECs)[64]. TLR-4 expression in healthy liver tissue is generally low because of the high degree of tolerance of this organ to the continuously incoming gut-derived TLR-4 ligands. The liver receives high concentrations of gut-derived endotoxin because of its location between the systemic and portal bloodstream and the connection with the intestine through the biliary tract. Kupffer cells and hepatocytes take up the incoming LPS, which removes it from the blood and places it into the bile[65-67]. Increased TLR-4 expression is induced in the injured liver, and inflammatory signaling cascades are triggered by this activation[68]. Two microRNAs are primarily involved in the regulation of “LPS tolerance”. TLR-4 activation increases miR-155 levels, which leads to the degradation of Src homology 2 domain-containing inositol-5-phosphatase 1, a down-regulator of TLR-4 signaling, and stimulation of the TLR-4 signaling pathway[69]. However, TLR-4 activation increases miR-21 expression, which upregulates IL-10 via programmed cell death protein 4 inhibition[70]. TLR-4-induces IL-10, which inhibits miR-155 and downgrades TRL-4 signaling. Therefore, the balance between miR-21 and miR-155 likely plays a pivotal role in the regulation of “LPS tolerance”. Other microRNAs are as fundamental in the control of the TLR-4-induced inflammatory response, particularly miR-146a and miR-9, which resolve the pro-inflammatory response by targeting key components in the TLR-4 signaling pathways, and miR-147, which promotes an anti-inflammatory response via repression of cytokine production[71].

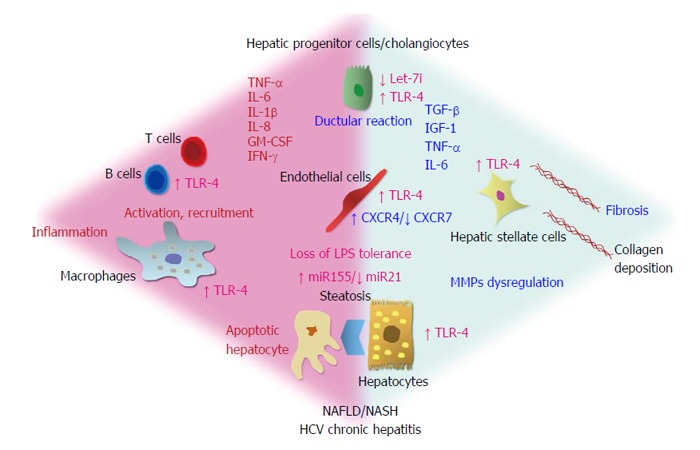

Once normal immune tolerance is exceeded, LPS directly activates the TLR-4 signaling pathway on Kupffer cells, HSCs, hepatocytes and cholangiocytes (Figure 2). LPS cooperates with circulating LPS-binding protein and binds to TLR-4 on the plasma membrane of cells with two co-receptors [CD14 and myeloid differentiation protein (MD)2] to activated TLR-4 signaling pathways in a myeloid differentiation factor (MyD)88-dependent or independent manner[72]. The MyD88 dependent signaling pathway primarily uses the iκB kinase and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathways, which determines the activation of NF-κB and activator protein-1, respectively, and regulates the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and other genes related to immune functions[72]. The MyD88-independent signaling pathway is mediated by the Toll/interleukin-1 receptor domain-containing adaptor inducing interferon-β, which activates interferon regulatory factor 3 and induces the expression of interferon (IFN)-β and genes that respond to IFN[72].

Figure 2.

Hepatic cell types express toll-like receptor-4. In the presence of the loss of lipopolysaccharides (LPS) tolerance, such as during non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, non-alcoholic steatohepatitis or HCV chronic hepatitis, TLR-4 is activated by gut-derived LPS and overexpressed. An altered balance of known miRNAs (miR155, miR21, let-7i) and chemokine receptors (CXCR4, CXCR7) could promote this condition. Then, activation and recruitment of inflammatory cells, ductular reaction and activation of endothelial and stellate cells drive liver inflammation and fibrosis. On the right, the mediators mainly involved in the fibrosis are presented (TGF-β, IGF-1, TNF-α, IL-6), on the left, mediators related to the inflammation are shown (TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1α, IL-8, GM-CSF, IFN-γ). TLR-4: Toll-like receptor-4; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor alpha; IL: Interleukin; GM-CSF: Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor; IFN: Interferon; HCV: Hepatitis C virus; MMPs: Matrix metalloproteinases; NAFLD/NASH: Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis.

LPS, via activation of TLR-4 and the consequent inflammatory cascade in target cells, plays a key role in the pathogenesis and progression of fatty liver of alcoholic and non-alcoholic origin[24,73]. Szabo et al[73] recently suggested that alcohol and its metabolites regulate the intestinal barrier and allow increased LPS blood concentrations to reach the liver via the portal blood and promote TLR-4-induced inflammation and liver damage. The molecular mechanisms triggered by the LPS/TLR-4 binding are likely crucial in NAFLD. Animal models of genetically induced obesity demonstrate an increased susceptibility to liver damage from endotoxin, and exposure to low doses of LPS also determines steatohepatitis development[74]. Animal models of diet-induced steatohepatitis also exhibit increased levels of portal endotoxemia and TLR-4 hepatic hyperexpression[24]. Probiotic treatment prevents the histological features of NASH in genetically obese animal models[75], which supports the hypothesis of the pathogenetic role of intestinal-derived bacterial products.

TLR-4 likely plays a role in viral hepatitis C, but the relationship between hepatitis C virus (HCV) and TLR-4 is quite complex. HCV infection directly induces TLR-4 expression[76] and may determine the loss of tolerance to TLR-4 ligands by monocytes and macrophages[77]. The TLR-4 signal may also regulate HCV replication[78]. Variants of the TLR-4 gene modulate the risk for liver fibrosis in Caucasian patients with chronic HCV infection[79,80]. TLR-4 was also involved in the cooperation between HCV and alcohol towards liver damage and hepatic oncogenesis in the liver progenitor cell transplantation model[81].

Inflammation (with secretion of TNF-α and IL-6) and anti-viral effects (with secretion of IFN-β) are determined by TLR-4 activation, depending on whether the MyD88-dependent or independent pathway is induced, respectively[82]. The function of TLR-4 in LPS-stimulated proinflammatory responses of Kupffer cells is well characterized[76,77], but new insights were proposed recently. A TLR-4-driven metalloprotease expression has been postulated since matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-10 was recently added to the list of genes that TLR-4 induces in liver macrophages[83]. MMP-10 was induced during hepatic injury and played a fundamental role in liver tissue repair[83]. Monocytes/macrophages represent the primary cellular targets of intestinal-derived endotoxin, and they are primary effectors of LPS-induced liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy and the experimental cholestatic liver disease, in which LPS promotes fibrogenesis[84,85].

TLR-4 expression by HSCs suggests a direct role of the receptor in hepatic fibrogenesis[72]. Transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) signaling and liver fibrosis were enhanced by TLR-4 expression in HSCs[86], and the apoptotic threshold of HSCs is lowered by two TLR-4 polymorphisms that are protective against fibrosis[87].

The expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules in HSCs by TLR-4 signaling is likely also involved in macrophage recruitment to fibrogenesis sites[86].

LSECs and Kupffer cells play important roles in the clearance of gut-derived LPS without inducing local inflammatory reactions under physiological conditions. LPS tolerance in LSECs depends on reducing the nuclear translocation of NF-κB without a change in TRL-4/CD14 surface expression or scavenger activity[88]. The C-X-C chemokine receptor type-(CXCR)4 was recently demonstrated to be a part of the LPS “sensing apparatus”, and inhibition of CXCR4 expression in endothelial cells (by RNA interference) decreased IL-6 production, LPS binding and chemotaxis[89]. CXCR4 over-expression on the LSECs membrane is driven by chronic injury[90,91], and CXCR4 expression likely plays a central role in provoking fibrosis after chronic insult. CXCR4 downregulation (together with CXCR7 expression) stimulates regeneration immediately after injury. LSEC phenotype conversion from a CXCR7- to a CXCR4-expressing cell may enhance the response to gut-derived LPS, which provides a further mechanism for the induction of TLR-4 activation and pro-fibrogenic cascade.

Hepatic progenitor cells, which were traditionally not described as TLR-4-expressing elements, were also recently demonstrated to be involved in TLR-4 signaling. TLR-4 expression by hepatic progenitor cells and inflammatory cells at the porto-septal and interface level in patients with NAFLD, was supported by increased LPS activity and associated with the activation of fibrogenic cells and the degree of fibrosis[92]. Biliary cells of the interlobular bile ducts and liver progenitor cells exhibit the highest TLR-4 immunohistochemical expression in patients with chronic hepatitis C, which correlated with the degree of inflammation, portal/septal myofibroblasts activity and fibrosis stage[93].

Hepatic progenitor cells, which are bipotential stem cells that reside in human and animal livers, differentiate towards hepatocytic and cholangiocytic lineages, and proliferation leads to the so-called “ductular reaction”[93-96]. Studies in patients with biliary disorders and experimental models of biliary fibrosis demonstrated that the ductal epithelium expressed several profibrogenic and chemotactic proteins[97-100], and TLR-4 expression by biliary epithelial cells was associated with inflammation and fibrosis progression[93,101,102]. Proinflammatory cytokines produced in response to TLR-4 signaling may participate in the cross-talk between hepatic progenitor cells and proliferating cholangiocytes or inflammatory cells and portal/septal myofibroblasts[93].

Increased TLR-4 expression by cholangiocytes represents a marker of loss of tolerance to LPS, which contributes to chronic biliary inflammation[102]. TLR-4-expressing cholangiocytes produce high levels of IL-1β, IL-8, IFN-γ, TNF-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and TGF-β[101]. LPS treatment of cultured biliary epithelial cells induces nuclear translocation of NF-κB, NF-κB-DNA binding and the production of TNF-α[103]. Human cholangiocytes cultured under normal physiological conditions express let-7i (a family members of let-7 miRNA), which post-transcriptionally downregulates TLR-4 expression[104]. The formation of an NF-κB p50-C/EBPβ silencer complex after LPS treatment or Cryptosporidium parvum infection inhibits the transcription of Let-7i and leads to increased TLR-4 expression[104,105]. This mechanism was hypothesized to allow detection and response to microbes without enhancing the inflammatory response.

Activation of the hepatic progenitor cell compartment and the consequent ductular reaction are also associated with the severity of nonbiliary chronic liver disease[93,106-108], and endotoxin also exhibits a role in stem cell/progenitor activation in other organs. LPS directly induces the proliferation of embryonic stem cells and adult tissue-specific stem cells/progenitors[109], hematopoietic progenitors[110], bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells[111]. The transplantation of p53-deficient hepatic progenitor cells transduced with TLR-4 results in liver-tumor development in mice following repetitive LPS injection[80].

CONCLUSION

The term “gut-liver axis” comes from the evidence of a strict interconnection between the gut and liver physiology and pathophysiology, and gut microbiota were recently claimed as a key mediator of this linkage. Chronic liver diseases are associated with qualitative and quantitative changes in the intestinal microbiota, which are partially dependent on the specific hepatic disease, and dysbiosis is almost always present during liver cirrhosis, regardless of the etiology of liver injury. Altered gut microflora contribute to intestinal dysmotility, inflammation and mucosal leakage. Finally, intestinal barrier damage allows the translocation of viable microorganisms and bacterial products, which reach the liver through portal blood and activate inflammatory pathways on liver cells.

These bases suggest that the TLR-4 receptor for bacterial endotoxin plays a starring role in the gut-liver axis. TLR-4 is activated in intestinal muscolaris macrophages, which are stimulated to produce and release prostaglandins and cytokines, and intestinal SMCs, which exhibit altered contractility with resulting dysmotility. TLR-4 activation in the gut exacerbates intestinal mucosal damage and bacterial translocation. Finally, most hepatic cell types express TLR-4, and LPS directly activates TLR-4 signaling in the liver once normal immune tolerance is exceeded. TLR-4 activation in Kupffer cells, HSCs, hepatocytes and cholangiocytes is implicated in most of inflammatory and fibrogenic pathways and activation contributes to the progression of liver disorders and complications of liver cirrhosis.

There are two promising strategies to hinder the deleterious effects of excessive TLR-4 activation: Modulation of gut microbiota to reduce the amount of TLR-4 ligand and direct interference with TLR-4 signaling. Drugs that are capable of attaining the first outcome, such as probiotics, prebiotics and antibiotics, already exist, and probiotic therapy produces beneficial effects on the liver, at least in the context of NAFLD[112]. Drugs of the second class are far from clinical application, but TLR-4 antagonism could weaken host immunity. However, some interesting evidence already comes from experimental studies, and the TLR-4 antagonist eritoran tetrasodium was recently demonstrated to attenuate liver damage in a liver ischemia/reperfusion injury model[113].

In conclusion, TLR-4 has emerged as a clear protagonist in the gut liver-axis over the past few years. Now that the pathophysiological basis is mostly known, it is time to see whether we can convert this knowledge into effective therapeutic interventions.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Thanks are due to Mr. Mislav Dadic and Mr. Rocco Simone Flammia for their help in the artwork generation.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Gafencu AV, Santos MM, Tanaka H S- Editor: Ji FF L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

Conflict-of-interest statement: The author has no conflict of interests.

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Peer-review started: May 28, 2015

First decision: July 10, 2015

Article in press: October 19, 2015

References

- 1.Volta U, Bonazzi C, Bianchi FB, Baldoni AM, Zoli M, Pisi E. IgA antibodies to dietary antigens in liver cirrhosis. Ric Clin Lab. 1987;17:235–242. doi: 10.1007/BF02912537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minemura M, Shimizu Y. Gut microbiota and liver diseases. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:1691–1702. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i6.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sekirov I, Russell SL, Antunes LC, Finlay BB. Gut microbiota in health and disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:859–904. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00045.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seki E, Schwabe RF. Hepatic inflammation and fibrosis: functional links and key pathways. Hepatology. 2015;61:1066–1079. doi: 10.1002/hep.27332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fukui H. Gut-liver axis in liver cirrhosis: How to manage leaky gut and endotoxemia. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:425–442. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barreau F, Hugot JP. Intestinal barrier dysfunction triggered by invasive bacteria. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2014;17:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beutler B. Inferences, questions and possibilities in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nature. 2004;430:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kawasaki T, Kawai T. Toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Front Immunol. 2014;5:461. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miele L, Valenza V, La Torre G, Montalto M, Cammarota G, Ricci R, Mascianà R, Forgione A, Gabrieli ML, Perotti G, et al. Increased intestinal permeability and tight junction alterations in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2009;49:1877–1887. doi: 10.1002/hep.22848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sabaté JM, Jouët P, Harnois F, Mechler C, Msika S, Grossin M, Coffin B. High prevalence of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth in patients with morbid obesity: a contributor to severe hepatic steatosis. Obes Surg. 2008;18:371–377. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9398-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Raman M, Ahmed I, Gillevet PM, Probert CS, Ratcliffe NM, Smith S, Greenwood R, Sikaroodi M, Lam V, Crotty P, et al. Fecal microbiome and volatile organic compound metabolome in obese humans with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11:868–75.e1-3. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turnbaugh PJ, Bäckhed F, Fulton L, Gordon JI. Diet-induced obesity is linked to marked but reversible alterations in the mouse distal gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:213–223. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ley RE, Turnbaugh PJ, Klein S, Gordon JI. Microbial ecology: human gut microbes associated with obesity. Nature. 2006;444:1022–1023. doi: 10.1038/4441022a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Conterno L, Fava F, Viola R, Tuohy KM. Obesity and the gut microbiota: does up-regulating colonic fermentation protect against obesity and metabolic disease? Genes Nutr. 2011;6:241–260. doi: 10.1007/s12263-011-0230-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zambell KL, Fitch MD, Fleming SE. Acetate and butyrate are the major substrates for de novo lipogenesis in rat colonic epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2003;133:3509–3515. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.11.3509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cope K, Risby T, Diehl AM. Increased gastrointestinal ethanol production in obese mice: implications for fatty liver disease pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2000;119:1340–1347. doi: 10.1053/gast.2000.19267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu L, Baker SS, Gill C, Liu W, Alkhouri R, Baker RD, Gill SR. Characterization of gut microbiomes in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients: a connection between endogenous alcohol and NASH. Hepatology. 2013;57:601–609. doi: 10.1002/hep.26093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dumas ME, Barton RH, Toye A, Cloarec O, Blancher C, Rothwell A, Fearnside J, Tatoud R, Blanc V, Lindon JC, et al. Metabolic profiling reveals a contribution of gut microbiota to fatty liver phenotype in insulin-resistant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:12511–12516. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601056103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hylemon PB, Zhou H, Pandak WM, Ren S, Gil G, Dent P. Bile acids as regulatory molecules. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1509–1520. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R900007-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinal CJ, Tohkin M, Miyata M, Ward JM, Lambert G, Gonzalez FJ. Targeted disruption of the nuclear receptor FXR/BAR impairs bile acid and lipid homeostasis. Cell. 2000;102:731–744. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Prawitt J, Abdelkarim M, Stroeve JH, Popescu I, Duez H, Velagapudi VR, Dumont J, Bouchaert E, van Dijk TH, Lucas A, et al. Farnesoid X receptor deficiency improves glucose homeostasis in mouse models of obesity. Diabetes. 2011;60:1861–1871. doi: 10.2337/db11-0030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas C, Gioiello A, Noriega L, Strehle A, Oury J, Rizzo G, Macchiarulo A, Yamamoto H, Mataki C, Pruzanski M, et al. TGR5-mediated bile acid sensing controls glucose homeostasis. Cell Metab. 2009;10:167–177. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cani PD, Osto M, Geurts L, Everard A. Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes associated with obesity. Gut Microbes. 2012;3:279–288. doi: 10.4161/gmic.19625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivera CA, Adegboyega P, van Rooijen N, Tagalicud A, Allman M, Wallace M. Toll-like receptor-4 signaling and Kupffer cells play pivotal roles in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic steatohepatitis. J Hepatol. 2007;47:571–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kodama Y, Kisseleva T, Iwaisako K, Miura K, Taura K, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Schnabl B, Seki E, Brenner DA. c-Jun N-terminal kinase-1 from hematopoietic cells mediates progression from hepatic steatosis to steatohepatitis and fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2009;137:1467–1477.e5. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alisi A, Manco M, Devito R, Piemonte F, Nobili V. Endotoxin and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 serum levels associated with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2010;50:645–649. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c7bdf1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harte AL, da Silva NF, Creely SJ, McGee KC, Billyard T, Youssef-Elabd EM, Tripathi G, Ashour E, Abdalla MS, Sharada HM, et al. Elevated endotoxin levels in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. J Inflamm (Lond) 2010;7:15. doi: 10.1186/1476-9255-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yan AW, Fouts DE, Brandl J, Stärkel P, Torralba M, Schott E, Tsukamoto H, Nelson KE, Brenner DA, Schnabl B. Enteric dysbiosis associated with a mouse model of alcoholic liver disease. Hepatology. 2011;53:96–105. doi: 10.1002/hep.24018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forsyth CB, Farhadi A, Jakate SM, Tang Y, Shaikh M, Keshavarzian A. Lactobacillus GG treatment ameliorates alcohol-induced intestinal oxidative stress, gut leakiness, and liver injury in a rat model of alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcohol. 2009;43:163–172. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y, Liu Y, Sidhu A, Ma Z, McClain C, Feng W. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG culture supernatant ameliorates acute alcohol-induced intestinal permeability and liver injury. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;303:G32–G41. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutlu EA, Gillevet PM, Rangwala H, Sikaroodi M, Naqvi A, Engen PA, Kwasny M, Lau CK, Keshavarzian A. Colonic microbiome is altered in alcoholism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2012;302:G966–G978. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00380.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bode JC, Bode C, Heidelbach R, Dürr HK, Martini GA. Jejunal microflora in patients with chronic alcohol abuse. Hepatogastroenterology. 1984;31:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bode C, Bode JC. Alcohol’s role in gastrointestinal tract disorders. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21:76–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Yang F, Lu H, Wang B, Chen Y, Lei D, Wang Y, Zhu B, Li L. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2011;54:562–572. doi: 10.1002/hep.24423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu ZW, Lu HF, Wu J, Zuo J, Chen P, Sheng JF, Zheng SS, Li LJ. Assessment of the fecal lactobacilli population in patients with hepatitis B virus-related decompensated cirrhosis and hepatitis B cirrhosis treated with liver transplant. Microb Ecol. 2012;63:929–937. doi: 10.1007/s00248-011-9945-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang CS, Chen GH, Lien HC, Yeh HZ. Small intestine dysmotility and bacterial overgrowth in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Hepatology. 1998;28:1187–1190. doi: 10.1002/hep.510280504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gómez-Hurtado I, Santacruz A, Peiró G, Zapater P, Gutiérrez A, Pérez-Mateo M, Sanz Y, Francés R. Gut microbiota dysbiosis is associated with inflammation and bacterial translocation in mice with CCl4-induced fibrosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23037. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen P, Stärkel P, Turner JR, Ho SB, Schnabl B. Dysbiosis-induced intestinal inflammation activates tumor necrosis factor receptor I and mediates alcoholic liver disease in mice. Hepatology. 2015;61:883–894. doi: 10.1002/hep.27489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benten D, Wiest R. Gut microbiome and intestinal barrier failure--the “Achilles heel” in hepatology? J Hepatol. 2012;56:1221–1223. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Quigley EM. Gastrointestinal dysfunction in liver disease and portal hypertension. Gut-liver interactions revisited. Dig Dis Sci. 1996;41:557–561. doi: 10.1007/BF02282341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quigley EM. Microflora modulation of motility. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2011;17:140–147. doi: 10.5056/jnm.2011.17.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Barbara G, Stanghellini V, Brandi G, Cremon C, Di Nardo G, De Giorgio R, Corinaldesi R. Interactions between commensal bacteria and gut sensorimotor function in health and disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100:2560–2568. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Overhaus M, Tögel S, Pezzone MA, Bauer AJ. Mechanisms of polymicrobial sepsis-induced ileus. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2004;287:G685–G694. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00359.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gwee KA, Collins SM, Read NW, Rajnakova A, Deng Y, Graham JC, McKendrick MW, Moochhala SM. Increased rectal mucosal expression of interleukin 1beta in recently acquired post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 2003;52:523–526. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Liebregts T, Adam B, Bredack C, Röth A, Heinzel S, Lester S, Downie-Doyle S, Smith E, Drew P, Talley NJ, et al. Immune activation in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:913–920. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kindt S, Vanden Berghe P, Boesmans W, Roosen L, Tack J. Prolonged IL-1beta exposure alters neurotransmitter and electrically induced Ca(2+) responses in the myenteric plexus. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:321–e85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2009.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Barona I, Fagundes DS, Gonzalo S, Grasa L, Arruebo MP, Plaza MÁ, Murillo MD. Role of TLR4 and MAPK in the local effect of LPS on intestinal contractility. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63:657–662. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tomita M, Ohkubo R, Hayashi M. Lipopolysaccharide transport system across colonic epithelial cells in normal and infective rat. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2004;19:33–40. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.19.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Guarino MP, Sessa R, Altomare A, Cocca S, Di Pietro M, Carotti S, Schiavoni G, Alloni R, Emerenziani S, Morini S, et al. Human colonic myogenic dysfunction induced by mucosal lipopolysaccharide translocation and oxidative stress. Dig Liver Dis. 2013;45:1011–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carotti S, Guarino MP, Cicala M, Perrone G, Alloni R, Segreto F, Rabitti C, Morini S. Effect of ursodeoxycholic acid on inflammatory infiltrate in gallbladder muscle of cholesterol gallstone patients. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2010;22:866–73, e232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Guarino MP, Carotti S, Morini S, Perrone G, Behar J, Altomare A, Alloni R, Caviglia R, Emerenziani S, Rabitti C, et al. Decreased number of activated macrophages in gallbladder muscle layer of cholesterol gallstone patients following ursodeoxycholic acid. Gut. 2008;57:1740–1741. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.160333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fornai M, Blandizzi C, Colucci R, Antonioli L, Bernardini N, Segnani C, Baragatti B, Barogi S, Berti P, Spisni R, et al. Role of cyclooxygenases 1 and 2 in the modulation of neuromuscular functions in the distal colon of humans and mice. Gut. 2005;54:608–616. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.053322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Kofahi M, Becker F, Gavins FN, Woolard MD, Tsunoda I, Wang Y, Ostanin D, Zawieja DC, Muthuchamy M, von der Weid PY, et al. IL-1β reduces tonic contraction of mesenteric lymphatic muscle cells, with the involvement of cycloxygenase-2 and prostaglandin E2. Br J Pharmacol. 2015;172:4038–4051. doi: 10.1111/bph.13194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scirocco A, Matarrese P, Petitta C, Cicenia A, Ascione B, Mannironi C, Ammoscato F, Cardi M, Fanello G, Guarino MP, et al. Exposure of Toll-like receptors 4 to bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) impairs human colonic smooth muscle cell function. J Cell Physiol. 2010;223:442–450. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foxx-Orenstein AE, Chey WD. Manipulation of the Gut Microbiota as a Novel Treatment Strategy for Gastrointestinal Disorders. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;1 Suppl:41–46. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Verdú EF, Bercík P, Bergonzelli GE, Huang XX, Blennerhasset P, Rochat F, Fiaux M, Mansourian R, Corthésy-Theulaz I, Collins SM. Lactobacillus paracasei normalizes muscle hypercontractility in a murine model of postinfective gut dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:826–837. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang H, Gong J, Wang W, Long Y, Fu X, Fu Y, Qian W, Hou X. Are there any different effects of Bifidobacterium, Lactobacillus and Streptococcus on intestinal sensation, barrier function and intestinal immunity in PI-IBS mouse model? PLoS One. 2014;9:e90153. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hyland NP, Quigley EM, Brint E. Microbiota-host interactions in irritable bowel syndrome: epithelial barrier, immune regulation and brain-gut interactions. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:8859–8866. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i27.8859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bertiaux-Vandaële N, Youmba SB, Belmonte L, Lecleire S, Antonietti M, Gourcerol G, Leroi AM, Déchelotte P, Ménard JF, Ducrotté P, et al. The expression and the cellular distribution of the tight junction proteins are altered in irritable bowel syndrome patients with differences according to the disease subtype. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:2165–2173. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Martínez C, Lobo B, Pigrau M, Ramos L, González-Castro AM, Alonso C, Guilarte M, Guilá M, de Torres I, Azpiroz F, et al. Diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome: an organic disorder with structural abnormalities in the jejunal epithelial barrier. Gut. 2013;62:1160–1168. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villani AC, Lemire M, Thabane M, Belisle A, Geneau G, Garg AX, Clark WF, Moayyedi P, Collins SM, Franchimont D, et al. Genetic risk factors for post-infectious irritable bowel syndrome following a waterborne outbreak of gastroenteritis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:1502–1513. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Guarino MP, Altomare A, Stasi E, Marignani M, Severi C, Alloni R, Dicuonzo G, Morelli L, Coppola R, Cicala M. Effect of acute mucosal exposure to Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG on human colonic smooth muscle cells. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42 Suppl 3 Pt 2:S185–S190. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31817e1cac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ammoscato F, Scirocco A, Altomare A, Matarrese P, Petitta C, Ascione B, Caronna R, Guarino M, Marignani M, Cicala M, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus protects human colonic muscle from pathogen lipopolysaccharide-induced damage. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2013;25:984–e777. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Seki E, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptors and adaptor molecules in liver disease: update. Hepatology. 2008;48:322–335. doi: 10.1002/hep.22306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwabe RF, Seki E, Brenner DA. Toll-like receptor signaling in the liver. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1886–1900. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van Bossuyt H, De Zanger RB, Wisse E. Cellular and subcellular distribution of injected lipopolysaccharide in rat liver and its inactivation by bile salts. J Hepatol. 1988;7:325–337. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(88)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mimura Y, Sakisaka S, Harada M, Sata M, Tanikawa K. Role of hepatocytes in direct clearance of lipopolysaccharide in rats. Gastroenterology. 1995;109:1969–1976. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90765-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kitazawa T, Tsujimoto T, Kawaratani H, Fujimoto M, Fukui H. Expression of Toll-like receptor 4 in various organs in rats with D-galactosamine-induced acute hepatic failure. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:e494–e498. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.05246.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.O’Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:7113–7118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902636106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sheedy FJ, Palsson-McDermott E, Hennessy EJ, Martin C, O’Leary JJ, Ruan Q, Johnson DS, Chen Y, O’Neill LA. Negative regulation of TLR4 via targeting of the proinflammatory tumor suppressor PDCD4 by the microRNA miR-21. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/ni.1828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.O’Neill LA, Sheedy FJ, McCoy CE. MicroRNAs: the fine-tuners of Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:163–175. doi: 10.1038/nri2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Guo J, Friedman SL. Toll-like receptor 4 signaling in liver injury and hepatic fibrogenesis. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2010;3:21. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Szabo G, Bala S. Alcoholic liver disease and the gut-liver axis. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:1321–1329. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i11.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang SQ, Lin HZ, Lane MD, Clemens M, Diehl AM. Obesity increases sensitivity to endotoxin liver injury: implications for the pathogenesis of steatohepatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2557–2562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Li Z, Yang S, Lin H, Huang J, Watkins PA, Moser AB, Desimone C, Song XY, Diehl AM. Probiotics and antibodies to TNF inhibit inflammatory activity and improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2003;37:343–350. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Machida K, Cheng KT, Sung VM, Levine AM, Foung S, Lai MM. Hepatitis C virus induces toll-like receptor 4 expression, leading to enhanced production of beta interferon and interleukin-6. J Virol. 2006;80:866–874. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.2.866-874.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dolganiuc A, Norkina O, Kodys K, Catalano D, Bakis G, Marshall C, Mandrekar P, Szabo G. Viral and host factors induce macrophage activation and loss of toll-like receptor tolerance in chronic HCV infection. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:1627–1636. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Broering R, Wu J, Meng Z, Hilgard P, Lu M, Trippler M, Szczeponek A, Gerken G, Schlaak JF. Toll-like receptor-stimulated non-parenchymal liver cells can regulate hepatitis C virus replication. J Hepatol. 2008;48:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang H, Shiffman ML, Friedman S, Venkatesh R, Bzowej N, Abar OT, Rowland CM, Catanese JJ, Leong DU, Sninsky JJ, et al. A 7 gene signature identifies the risk of developing cirrhosis in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology. 2007;46:297–306. doi: 10.1002/hep.21695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Li Y, Chang M, Abar O, Garcia V, Rowland C, Catanese J, Ross D, Broder S, Shiffman M, Cheung R, et al. Multiple variants in toll-like receptor 4 gene modulate risk of liver fibrosis in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis C infection. J Hepatol. 2009;51:750–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Machida K, Tsukamoto H, Mkrtchyan H, Duan L, Dynnyk A, Liu HM, Asahina K, Govindarajan S, Ray R, Ou JH, et al. Toll-like receptor 4 mediates synergism between alcohol and HCV in hepatic oncogenesis involving stem cell marker Nanog. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1548–1553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807390106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Andreakos E, Foxwell B, Feldmann M. Is targeting Toll-like receptors and their signaling pathway a useful therapeutic approach to modulating cytokine-driven inflammation? Immunol Rev. 2004;202:250–265. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Garcia-Irigoyen O, Carotti S, Latasa MU, Uriarte I, Fernández-Barrena MG, Elizalde M, Urtasun R, Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Morini S, Banales JM, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-10 expression is induced during hepatic injury and plays a fundamental role in liver tissue repair. Liver Int. 2014;34:e257–e270. doi: 10.1111/liv.12337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Isayama F, Hines IN, Kremer M, Milton RJ, Byrd CL, Perry AW, McKim SE, Parsons C, Rippe RA, Wheeler MD. LPS signaling enhances hepatic fibrogenesis caused by experimental cholestasis in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;290:G1318–G1328. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00405.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Strey CW, Markiewski M, Mastellos D, Tudoran R, Spruce LA, Greenbaum LE, Lambris JD. The proinflammatory mediators C3a and C5a are essential for liver regeneration. J Exp Med. 2003;198:913–923. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, Schwabe RF. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Guo J, Loke J, Zheng F, Hong F, Yea S, Fukata M, Tarocchi M, Abar OT, Huang H, Sninsky JJ, et al. Functional linkage of cirrhosis-predictive single nucleotide polymorphisms of Toll-like receptor 4 to hepatic stellate cell responses. Hepatology. 2009;49:960–968. doi: 10.1002/hep.22697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Uhrig A, Banafsche R, Kremer M, Hegenbarth S, Hamann A, Neurath M, Gerken G, Limmer A, Knolle PA. Development and functional consequences of LPS tolerance in sinusoidal endothelial cells of the liver. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:626–633. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0604332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Triantafilou M, Lepper PM, Briault CD, Ahmed MA, Dmochowski JM, Schumann C, Triantafilou K. Chemokine receptor 4 (CXCR4) is part of the lipopolysaccharide “sensing apparatus”. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:192–203. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ding BS, Nolan DJ, Butler JM, James D, Babazadeh AO, Rosenwaks Z, Mittal V, Kobayashi H, Shido K, Lyden D, et al. Inductive angiocrine signals from sinusoidal endothelium are required for liver regeneration. Nature. 2010;468:310–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Ding BS, Cao Z, Lis R, Nolan DJ, Guo P, Simons M, Penfold ME, Shido K, Rabbany SY, Rafii S. Divergent angiocrine signals from vascular niche balance liver regeneration and fibrosis. Nature. 2014;505:97–102. doi: 10.1038/nature12681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Carotti S, Perrone G, Mazzarelli C, Galati G, Onetti-Muda A, Picardi A, Morini S. Hepatic toll-like receptor 4 expression is associated with portal inflammation and fibrosis in patients with NAFLD. Liver Int. 2015;35:569–581. doi: 10.1111/liv.12531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Carotti S, Onetti-Muda A, Perrone G, Ginanni-Corradini S, Latasa MU, Avila MA, Carpino G, Picardi A, Morini S. Toll-like receptor-4 expression by hepatic progenitor cells and biliary epithelial cells in HCV-related chronic liver disease. Mod Pathol. 2012;25:576–589. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2011.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roskams TA, Theise ND, Balabaud C, Bhagat G, Bhathal PS, Bioulac-Sage P, Brunt EM, Crawford JM, Crosby HA, Desmet V, et al. Nomenclature of the finer branches of the biliary tree: canals, ductules, and ductular reactions in human livers. Hepatology. 2004;39:1739–1745. doi: 10.1002/hep.20130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gaudio E, Carpino G, Cardinale V, Franchitto A, Onori P, Alvaro D. New insights into liver stem cells. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:455–462. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Glaser SS, Gaudio E, Miller T, Alvaro D, Alpini G. Cholangiocyte proliferation and liver fibrosis. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2009;11:e7. doi: 10.1017/S1462399409000994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yasoshima M, Kono N, Sugawara H, Katayanagi K, Harada K, Nakanuma Y. Increased expression of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha in pathologic biliary epithelial cells: in situ and culture study. Lab Invest. 1998;78:89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Grappone C, Pinzani M, Parola M, Pellegrini G, Caligiuri A, DeFranco R, Marra F, Herbst H, Alpini G, Milani S. Expression of platelet-derived growth factor in newly formed cholangiocytes during experimental biliary fibrosis in rats. J Hepatol. 1999;31:100–109. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(99)80169-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Sedlaczek N, Jia JD, Bauer M, Herbst H, Ruehl M, Hahn EG, Schuppan D. Proliferating bile duct epithelial cells are a major source of connective tissue growth factor in rat biliary fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 2001;158:1239–1244. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64074-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.O’Hara SP, Tabibian JH, Splinter PL, LaRusso NF. The dynamic biliary epithelia: molecules, pathways, and disease. J Hepatol. 2013;58:575–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Karrar A, Broomé U, Södergren T, Jaksch M, Bergquist A, Björnstedt M, Sumitran-Holgersson S. Biliary epithelial cell antibodies link adaptive and innate immune responses in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1504–1514. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mueller T, Beutler C, Picó AH, Shibolet O, Pratt DS, Pascher A, Neuhaus P, Wiedenmann B, Berg T, Podolsky DK. Enhanced innate immune responsiveness and intolerance to intestinal endotoxins in human biliary epithelial cells contributes to chronic cholangitis. Liver Int. 2011;31:1574–1588. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2011.02635.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Harada K, Ohira S, Isse K, Ozaki S, Zen Y, Sato Y, Nakanuma Y. Lipopolysaccharide activates nuclear factor-kappaB through toll-like receptors and related molecules in cultured biliary epithelial cells. Lab Invest. 2003;83:1657–1667. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000097190.56734.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chen XM, Splinter PL, O’Hara SP, LaRusso NF. A cellular micro-RNA, let-7i, regulates Toll-like receptor 4 expression and contributes to cholangiocyte immune responses against Cryptosporidium parvum infection. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28929–28938. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702633200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.O’Hara SP, Splinter PL, Gajdos GB, Trussoni CE, Fernandez-Zapico ME, Chen XM, LaRusso NF. NFkappaB p50-CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein beta (C/EBPbeta)-mediated transcriptional repression of microRNA let-7i following microbial infection. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:216–225. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lowes KN, Brennan BA, Yeoh GC, Olynyk JK. Oval cell numbers in human chronic liver diseases are directly related to disease severity. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:537–541. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65299-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Carpino G, Renzi A, Onori P, Gaudio E. Role of hepatic progenitor cells in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease development: cellular cross-talks and molecular networks. Int J Mol Sci. 2013;14:20112–20130. doi: 10.3390/ijms141020112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Carotti S, Vespasiani-Gentilucci U, Perrone G, Picardi A, Morini S. Portal inflammation during NAFLD is frequent and associated with the early phases of putative hepatic progenitor cell activation. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68:883–890. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lee SH, Hong B, Sharabi A, Huang XF, Chen SY. Embryonic stem cells and mammary luminal progenitors directly sense and respond to microbial products. Stem Cells. 2009;27:1604–1615. doi: 10.1002/stem.75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, Bahrun U, Kouro T, Akira S, Takatsu K, Kincade PW. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24:801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Pevsner-Fischer M, Morad V, Cohen-Sfady M, Rousso-Noori L, Zanin-Zhorov A, Cohen S, Cohen IR, Zipori D. Toll-like receptors and their ligands control mesenchymal stem cell functions. Blood. 2007;109:1422–1432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ma YY, Li L, Yu CH, Shen Z, Chen LH, Li YM. Effects of probiotics on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a meta-analysis. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:6911–6918. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Mcdonald KA, Huang H, Tohme S, Loughran P, Ferrero K, Billiar T, Tsung A. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) antagonist eritoran tetrasodium attenuates liver ischemia and reperfusion injury through inhibition of high-mobility group box protein B1 (HMGB1) signaling. Mol Med. 2014;20:639–648. doi: 10.2119/molmed.2014.00076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]