Abstract

Background

Over 350 000 patients are treated in German hospitals for sepsis or pneumonia each year. The rate of antibiotic use in hospitals is high. The growing problem of drug resistance necessitates a reconsideration of antibiotic treatment strategies.

Methods

Antibiotics were given liberally in the years 2010 and 2011 in a German 312-bed hospital. Special training, standardized algorithms to prevent unnecessary drug orders, and uniform recommendations were used in 2012 and 2013 to lessen antibiotic use. We retrospectively studied the hospital’s mortality figures and microbiological findings to analyze how well these measures worked.

Results

Antibiotic consumption fell from 67.1 to 51.0 defined daily doses (DDD) per 100 patient days (p <0.001) from the period 2010–2011 to the period 2012–2013. The mortality of patients with a main diagnosis of sepsis fell from 31% (95/305) to 19% (63/327; p = 0.001), while that of patients with a main diagnosis of pneumonia fell from 12% (22/178) to 6% (15/235; p = 0.038). The overall mortality fell from 3.0% (623/ 20 954) to 2.5% (576/22 719; p = 0.005). In patients with nosocomial urinary tract infections with Gram-negative pathogens (not necessarily exhibiting three- or fourfold drug resistance), the rate of resistance to three or four of the antibiotics tested fell from 11% to 5%.

Conclusion

Reducing in-hospital antibiotic use is an achievable goal and was associated in this study with lower mortality and less drug resistance. The findings of this single-center, retrospective study encourage a more limited and focused approach to the administration of antibiotics.

Sepsis is associated with high rates of comorbidity and death (1– 7). Treatment with antibiotics represents a milestone in the management of septic diseases. It is indisputable that timely antibiotic treatment improves survival (8– 11). Retrospective analyses have shown that mortality increases to over 50% when treatment with antibiotics is delayed (12– 14). Administration of antibiotics within 60 min of “diagnosis of infection/sepsis” is one of the quality indicators of the German Interdisciplinary Association for Intensive Care Medicine (DIVI) (15), although no mandatory detailed algorithm for the diagnosis is provided. Many patients present indicators of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (16, 17) on admission without sepsis being confirmed later. For many years, therefore, young clinicians have been taught that antibiotics should be given early (within 60 min) in all cases of severe infection. Also for pneumonia, guidelines advise immediate antibiotic treatment (18).

However, this approach risks unnecessary administration of antibiotics to many patients who fulfill the criteria of SIRS but in fact have neither sepsis nor pneumonia.

It is undisputed that antibiotic use in Europe—including Germany—is excessively high (19– 21). According to the GERMAP report on the consumption of antimicrobials and the spread of antimicrobial resistance in human and veterinary medicine in Germany (22), the antibiotic use density in this country is ca. 57 defined daily doses (DDD) per 100 patient days. This leads to various problems, one of which is increased antibiotic resistance, e.g., the rise in the rate of multiresistant (3-MRGN) Escherichia coli from 5.1% in 2008 to 8.8% in 2013 (23). Another consequence is the spread of Clostridium difficile infections. It is therefore crucial to identify patients with sepsis and avoid giving antibiotics to patients with non-septic diseases. A campaign to systematically reduce antibiotic use in Germany was launched in 2011 (19). An S3 guideline on strategies for the rational use of anti-infectives (antibiotic stewardship) was published in December 2013 (24).

The study presented here was designed to answer the following questions:

Can the use of antibiotics in a hospital be decreased?

If antibiotic use is reduced, do deaths from sepsis and pneumonia increase as a result?

Does the reduced use of antibiotics affect antimicrobial resistance?

Methods

Hospital/study

The Asklepios Hospital Schildautal comprises facilities for internal medicine, surgery, vascular surgery, neurosurgery, and neurology (with a supraregional stroke unit). The hospital has 312 acute beds. A neurological rehabilitation center with 170 beds is attached but was not included in the analysis. There were no changes in structure or personnel during the study period. The study was observational in nature and was approved by the institutional ethics committee.

Phase 1: liberal use of antibiotics

From 1 January 2010 to 31 December 2011, immediate administration of antibiotics was the conventional and expected course of action whenever sepsis was suspected.

Phase 2: structured use of antibiotics

The antibiotic policy was then changed from one day to the next. From 1 January 2012 to 31 December 2013, a systematic attempt was made to reduce the use of antibiotics. The background to this decision was an analysis of the prescription of reserve antibiotics in the framework of the German Antimicrobial Resistance Strategy (Deutsche Antibiotika-Resistenzstrategie, DART) (19), leading to the realization that the use of antibiotics would have to be reduced. The hospital’s medical director therefore ordered a 50% decrease in antibiotic consumption; this marked the onset of restrictive antibiotic use. The hygiene committee became the “Committee for Hospital Hygiene and Antibiotic Stewardship” and its membership was extended to include a microbiologist and a pharmacist.

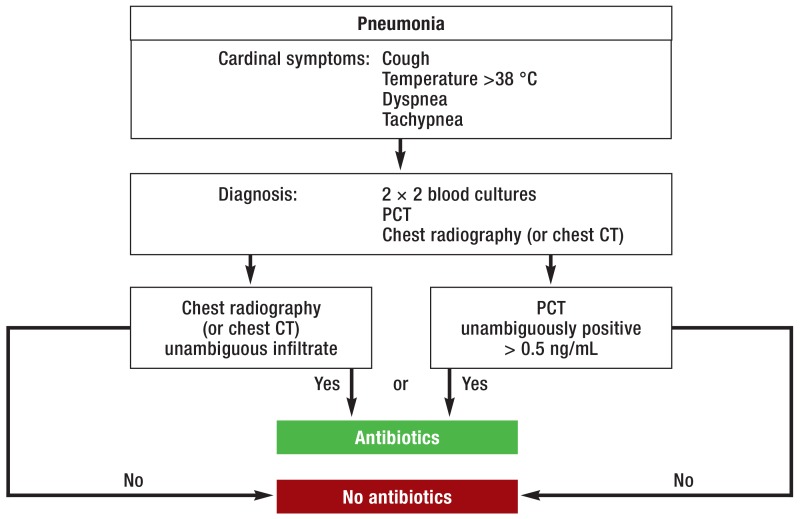

Internal recommendations for antibiotic prescription practice were drawn up. These included algorithms and advice on both the indications for antibiotic use and the class of antibiotic drugs to be prescribed if the indications were met. Physicians from all disciplines represented in the hospital attended training courses on restrictive use of antibiotics (coverage: 61% of all medical staff). Pocket algorithms were produced and handed to all physicians (100%). Three examples of these algorithms are shown in Figure 1. In analogy to the original charts, blood cultures were clearly indicated before administration of antibiotics in suspected sepsis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, and endocarditis. Emphasis was placed on compelling indications, choice of preparations, and dosage of calculated antibiotic treatment. The algorithms supported physicians in deciding to forgo treatment with antibiotics.

Figure 1a.

Pocket algorithm for suspected pneumonia

PCT, procalcitonin; CT, computed tomography

In 2012 the membership of the Committee for Hospital Hygiene and Antibiotic Stewardship was again extended to include two trained hygienists and a physician specialized in internal medicine who was freed from her regular duties and had begun curricular training in hospital hygiene. A system was set up for direct reporting of relevant pathogens by digital fax to the workplace computers of all members of the hospital hygiene team. The contact persons for antibiotic treatment were the microbiologist, the pharmacist, and an experienced internist. As part of the documentation of nosocomial infections, on one or two occasions each week the internist went to all the intensive care units and checked the antibiotic treatment there against the pocket algorithm recommendations and the microbiological findings.

Patient population

All patients were documented in structured fashion in the framework of the hospital information system (HIS): the principal diagnosis, secondary diagnoses, times of admission and discharge, type of discharge, and all operations and other procedures classified using the German modification of the International Classification of Procedures in Medicine (OPS) according to the relevant section of the German law regulating payments for inpatient hospital services were recorded. The discharge type “death” was defined as hospital mortality. In the presence of an advance directive or other declaration of the patient’s wishes in this regard, the desired restriction of treatment was entered in the HIS, categorized as “no resuscitation, but intensive care,” “no invasive ventilation,” or “palliative care” (the last two generally without intensive care). Medicinal treatments were not necessarily affected by the treatment restriction and were determined on an individual basis. In phase 2 of the study period, staff members’ awareness of this aspect of care was heightened by participation in training sessions offered by the ethics committee. The three categorical variables were summarized as treatment restriction “yes” or “no.”

Definition of sepsis

Sepsis was coded when the patient showed clinical signs of sepsis and four of four SIRS criteria were fulfilled, or alternatively two of four SIRS criteria plus positive blood culture or documented organ complication (17). This practice was followed over the whole 4-year period. The incidence of cases with the ICD code A40/41 was similar in phase 1 (1.46%) and phase 2 (1.44%). The members of staff were aware of the clinical imprecision of this definition from the medical service of the health insurance providers in Germany (MDK, Medizinischer Dienst der Krankenkassen).

Additional analysis of patients with sepsis

Every case coded as sepsis was double-checked for plausibility, blood culture findings, and initial antibiotic treatment. Of a total of 1104 coded cases, 1102 could be analyzed. These 1102 patients with a principal or secondary diagnosis coded as A40/41 (sepsis) were classified on the basis of their digital hospital records into one of two categories:

Community-acquired sepsis (no hospital stay within the previous 30 days)

Nosocomial sepsis (sepsis >48 h after admission to hospital or hospital stay within the previous 30 days or transfer from another hospital).

Patients with both secondary and principal diagnosis A40 or A41 (sepsis) were counted as “principal diagnosis sepsis;” those with secondary diagnosis A40 or A41 (sepsis) without principal diagnosis of sepsis were classed as “secondary diagnosis sepsis.” The patients with a principal diagnosis of sepsis were those who had been admitted for inpatient treatment because of sepsis, while the group “secondary diagnosis sepsis, nosocomial” comprised those who acquired their sepsis in the Asklepios Hospital. Patients classed as “secondary diagnosis sepsis, community acquired” had already had sepsis on arrival in the hospital but were admitted owing to another principal diagnosis.

Microbiological diagnosis

The blood cultures were systematically analyzed by means of the laboratory electronic data processing (EDP) system. Pathogen resistance was determined via the EDP system in cooperation with the Institute for Medical Microbiology of the School of Medicine at Göttingen University. For urine cultures, the data were drawn directly from the microbiology institute’s EDP system. In every patient, the urine culture used for analysis was the first pathogen-positive sample obtained more than 3 days after hospital admission; this ensured that the colonization or infection was nosocomial. If different pathogens were detected in consecutive urine samples from the same patient, the first microbe identified by the EDP system was recorded. During the study the procedure for sensitivity testing was switched from the guidelines of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) to the guidelines of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). For the Gram-negative bacteria (E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus spp., Pseudomonas spp.), ampicillin, cefuroxime, ciprofloxacin, and meropenem were included in the analysis: resistance to these antibiotics was tested in >95% of all pathogen-positive samples in both phases of the study period.

Antibiotic consumption

The consumption of antibiotics was systematically recorded by the hospital pharmacy using the EDP system and, via an Access database set up by ASMIN (a newly founded project for coordination of antibiotic stewardship in the hospitals of the German federal state of Lower Saxony), converted into the official DDD of the German Institute of Medical Documentation and Information (DIMDI), and assigned to the J01 groups of the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. Using the data from the HIS, the hospital’s financial controllers recorded the patient days to the minute, with midnight marking the end of the day. Only patients treated wholly on an inpatient basis were included. The days of admission and discharge were counted together as 1 day.

Data analysis

On completion of data acquisition the data sets were fully anonymized and analyzed using SPSS 21.0. The results are expressed below as absolute values with relative values in percentages. The mortality in a patient group and the resistance of individual pathogens to an antibiotic or to at least three antibiotics were employed as categorical variables (yes/no). The Pearson chi-square test was used to compare the two phases of the study period. Relative risk reduction (RR), odds ratio (OR), and 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were calculated. Mean values were compared by analysis of variance.

Results

The numbers of persons treated, patient days, and persons admitted to hospital owing to sepsis or pneumonia were similar in the two phases of the study period (Table).

Table. Inpatient cases over the 4-year study period (liberal use of antibiotics in phase 1 [2010–2011]. structured use of antibiotics in phase 2 [2012–2013])*1.

| Phase 1: liberal use of antibiotics 2010–2011 | Phase 2: structured use of antibiotics 2012–2013 | Change from phase 1 (2010–2011) to phase 2 (2012–2013) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total fully inpatient cases | n=20954 | n=22719 | +1765 cases | n. c. |

| Overall mortality | n=623 (3.0%) | n=576 (2.5%) | –0.5% (RR −15%. OR 0.85. CI 0.76–0.95 | p=0.005 |

| Patients with sepsis (ICD code A40–A41) as principal diagnosis | n=305 | n=327 | +22 cases | n. s. |

| Proportion of all fully inpatient cases | 1.5% | 1.4% | –0.1% | n. s. |

| Average age of all patients with sepsis (years) | 77 ± 12 | 75 ± 14 | –2 years | p=0.027 |

| Average hospital stay of all patients with sepsis (days) | 21 ± 23 | 17 ± 30 | –4 days | p=0.037 |

| Hospital mortality of all patients with sepsis | n=95 (31%) | n=63 (19%) | –12% (RR −38%. OR 0.53. CI 0.37–0.76) | p=0.001 |

| Patients with sepsis without treatment restrictions*2 | n=221 | n=198 | n. c. | |

| Hospital mortality of patients with sepsis without treatment restrictions*2 | n=47 (21%) | n=19 (10%) | –11% (RR −55%. OR 0.39. CI 0.22–0.70) | p=0.002 |

| Patients with nosocomial sepsis (ICD code A40–A41) as secondary diagnosis (NSSD) | n=155 | n=121 | –34 cases | n. c. |

| Proportion of all fully inpatient cases | 0.7% | 0.5% | –0.2% (RR −28%. OR 0.72. CI 0.57–0.91) | p=0.006 |

| Average age of all patients with NSSD (years) | 71 ± 13 | 73 ± 12 | +2 years | n. s. |

| Average hospital stay of all patients with NSSD (days) | 38 ± 36 | 39 ± 36 | +1 day | n. s. |

| Hospital mortality of all patients with NSSD | n=54 (35%) | n=40 (33%) | –2% | n. s. |

| Patients with NSSD without treatment restrictions*2 | n=132 (85%) | n=91 (75%) | –10% | n. c. |

| Hospital mortality of patients with NSSD without treatment restrictions*2 | n=36 (27%) | n=19 (21%) | –6% | n. s. |

| Patients with pneumonia (ICD code J13–J18) as principal diagnosis | n=178 | n=235 | +57 cases | n. c. |

| Proportion of all fully inpatient cases | 0.9% | 1.0% | 0.1% | n. c. |

| Average age of all patients with pneumonia (years) | 74 ± 14 | 75 ± 15 | +1 year | n. s. |

| Average hospital stay of all patients with pneumonia (days) | 11 ± 12 | 9 ± 7 | –2 days | p=0.004 |

| Hospital mortality of all patients with pneumonia | n=22 (12%) | n=15 (6%) | –6% (RR −52%. OR 0.48. CI 0.24–0.96) | p=0.038 |

| Patients with pneumonia without treatment restrictions*2 | n=143 (80%) | n=157 (67%) | –13 % | n. c. |

| Hospital mortality of patients with pneumonia without treatment restrictions*2 | n=8 (6%) | n=5 (3%) | –3% | n. s. |

*1Particular attention was paid to patients who were admitted with either sepsis or pneumonia or developed sepsis in the hospital. In phase 2 of the study with structured and thus reduced use of antibiotics. there was lower mortality both overall and in the subgroups pneumonia and sepsis. The mortality of patients with nosocomial sepsis was the same in both phases. but nosocomial sepsis occurred less frequently in phase 2.

*2In the presence of an advance directive or other declaration of the patient’s wishes. treatment restrictions (categorized as “no resuscitation.” “no invasive ventilation.” or “palliative care” were entered in the hospital information system (HIS). Medicinal treatment was not necessarily affected by treatment restrictions and was decided on an individual basis. In phase 2 members of staff attended training sessions to heighten their awareness in this regard. Patients with the treatment restriction “no resuscitation” were transferred to the intensive care unit just like patients with no treatment restrictions. Patients with the treatment restriction “no invasive ventilation” were not transferred to the intensive care unit.

Case numbers and mortality compared using Pearson’s chi-square test. reported as difference and for statistically significant results (p<0.05). the RR (relative risk reduction). OR (odds ratio). and 95% CI (95% confidence interval) are given. Comparison of mean age and hospital stay by analysis of variance. n. c.. not calculated;

n. s.. not significant

]

The overall mortality was n = 623 (3.0%) in phase 1 and decreased significantly to n = 576 (2.5%) in phase 2 (-0.5%, RR -15%, OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.95; p = 0.005).

In phase 1, 98.6% of patients with sepsis received antibiotics on the first day, in phase 2, 98.0%. Mortality among patients with sepsis or pneumonia was significantly lower in phase 2 (sepsis: RR -38%, OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.37 to 0.76; p = 0.001/pneumonia: RR -52%, OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24 to 0.96; p = 0.038) (Table).

The number of patients with nosocomial sepsis went down by 28% from n = 155 (0.74% of all inpatients) in phase 1 to n = 121 (0.53% of all inpatients) in phase 2 (Ttable).

The antibiotic consumption density was 67.1 DDD/100 patient days in the years 2010 to 2011 versus 51.0 DDD/100 patient days in the years 2012 to 2013 (OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.50 to 0.52; p <0.001). The decrease was particularly noticeable for the reserve antibiotics linezolid (-40%), cefepime (-77%), and tigecycline (-68%). Antibiotic costs decreased by 47% (eTable 1).

eTable 1. Antibiotic prescription densities over the 4-year study period (liberal use of antibiotics in phase 1 [2010–2011], structured use of antibiotics in phase 2 [2012–2013])*.

| ATC code | Antibiotic group | Phase 1: liberal use of antibiotics 2010–2011 | Phase 2:structured use of antibiotics 2012–2013 | Change fromphase 1 (2010–2011) to phase 2 (2012–2013) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J01AA | Tetracyclines without tigecycline | 2525 | 920 | –1605 DDD | –64% |

| J01AA | Tetracyclines, tigecycline only | 238 | 75 | –163 DDD | –68% |

| J01CA | Penicillins with extended spectrum of action | 10429 | 7598 | –2831 DDD | –27% |

| J01CE | Beta-lactamase–sensitive penicillins | 4700 | 4491 | –209 DDD | –4% |

| J01CF | Beta-lactamase–resistant penicillins | 1102 | 1003 | –99 DDD | –9% |

| J01CG | Beta-lactamase inhibitors | 1191 | 0 | –1191 DDD | –100% |

| J01CR | Penicillins with beta-lactamase inhibitors | 20366 | 13868 | –6498 DDD | –32% |

| J01DB | First-generation cephalosporins | 97 | 66 | –31 DDD | –32% |

| J01DC | Second-generation cephalosporins | 34054 | 23124 | –10 930 DDD | –32% |

| J01DD | Third-generation cephalosporins | 6998 | 7735 | +737 DDD | +11% |

| J01DE | Fourth-generation cephalosporins (cefepime) | 950 | 215 | –735 DDD | –77% |

| J01DH | Carbapenems | 8570 | 6953 | –1617 DDD | –19% |

| J01EE | Combination sulfonamide/trimethoprim | 4674 | 2719 | –1955 DDD | –42% |

| J01FA | Macrolides | 11676 | 9253 | –2423 DDD | –21% |

| J01FF | Lincosamides | 4059 | 2926 | –1133 DDD | –28% |

| J01GB | Other aminoglycosides | 1110 | 864 | –246 DDD | –22% |

| J01MA | Fluoroquinolones | 8091 | 7753 | –338 DDD | –4% |

| J01XA | Glycopeptide antibiotics | 4212 | 3076 | –1136 DDD | –27% |

| J01XD | Imidazole derivatives | 5398 | 3591 | –1807 DDD | –34% |

| J01XX | Other antibiotics without linezolid | 180 | 77 | –103 DDD | –57% |

| J01XX | Other antibiotics, linezolid only | 3078 | 1837 | –1241 DDD | –40% |

| J01XB | Polymyxins | 0 | 7 | +7 DDD | n. c. |

| Antibiotic prescriptions, all wards (DDD) | 133693 | 98148 | –35 545 DDD | –27% | |

| Antibiotic costs (€) | 1 012434 | 532623 | –479 811 | –47% | |

| Fully inpatient cases | 20954 | 22719 | +1765 cases | +8% | |

| Patient days, fully inpatient cases | 199311 | 192344 | –6967 days | –3% | |

| DDD/100 patient days (PD) | 67.1 | 51 | −16 DDD/100 PD | –24%*2 | |

| DDD/case | 6.4 | 4.3 | –2.1 DDD/case | –32% | |

*Overall, antibiotic use was reduced by 24% (expressed as defined daily doses [DDD]/100 patient days) or 32% (expressed as DDD/case). The effect was particularly pronounced for the reserve antibiotics linezolid (–40%), cefepime (overall DDD –77%) and tigecycline (overall DDD –68%). Only the use of third-generation cephalosporins (ceftriaxone) went up, by 11%. The overall expenditure on antibiotics decreased by 47%.

*2Pearson’s chi-square test (DDD versus „antibiotic-free patient days“): RR -24%, OR 0.51, 95% CI 0.50–0.52; p<0.001

ATC, Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical classification; DDD, defined daily doses; RR, relative risk reduction; OR, odds ratio; CI, 95% confidence interval;

n. c., not calculated

The number of paired blood cultures per 1000 patient days was 41 in phase 1 and 48 in phase 2; for urine cultures the figures were 34 and 37 respectively.

The resistance of Gram-negative bacteria responsible for nosocomial infection or colonization of the urinary tract to the tested antibiotics cefuroxime, ampicillin, ciprofloxacin, and meropenem showed a decreasing trend (eTable 2).

eTable 2. Monitoring of antibiotic treatment on the basis of positive urine cultures with nosocomial pathogens (samples taken >72 h after admission)*1; Antibiotics tested and analyzed: ampicillin. cefuroxime. ciprofloxacin. meropenem*2.

| Microbiological characteristics—urine cultures with nosocomial pathogens | Phase 1: liberal use of antibiotics 2010–2011 | Phase 2: structured use of antibiotics 2012–2013 | Change from phase 1 (2010–2011) to phase 2 (2012–2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Gram-negative pathogens | n=434 | n=373 | −61 cultures |

| Number of positive urine cultures. nosocomial E. coli only | n=312 | n=292 | −20 cultures |

| Number of positive urine cultures. nosocomial Klebsiella spp. only | n=50 | n=30 | −20 cultures |

| Number of positive urine cultures. nosocomial Proteus spp. only | n=34 | n=33 | −1 culture |

| Number of positive urine cultures. nosocomial Pseudomonas only | n=38 | n=18 | −20 cultures |

| Development of resistance | |||

| Resistance of nosocomial E. coli in urine cultures | |||

| Resistant to ampicillin | n=174 of 312 (56%) | n=167 of 290*3 (58%) | +2% n. s. |

| Resistant to cefuroxime | n=77 of 312 (25%) | n=30 of 290*3 (10%) | −15% (RR −58%. OR 0.35. CI 0.22 –0.56; p <0.001)*6 |

| Resistant to ciprofloxacin | n=63 of 312 (20%) | n=43 of 288*3 (15%) | −5% n. s. |

| Resistant to meropenem | n=0 of 300*3. (0%) | n=0 of 279*3 (0%) | +/-0 n. s. |

| Resistance of nosocomial Klebsiella spp.*4. Proteus spp.. Pseudomonas aeruginosa*4. in urine cultures | |||

| Resistant to ampicillin (Proteus only) | n=18 of 34 (53%) | n=13 of 33 (39%) | −14% n. s. |

| Resistant to cefuroxime (Klebsiella and Proteus only) | n=20 of 84 (24%) | n=12 of 63 (19%) | −5% n. s. |

| Resistant to ciprofloxacin (Klebsiella. Proteus. Pseudomonas) | n=21 of 122 (17%) | n=15 of 80*319%) | +2% n. s. |

| Resistant to meropenem (Klebsiella. Proteus. Pseudomonas) | n=5 of 122 (4%) | n=1 of 79*3 (1%) | −3% n. s. |

| Development of multiple resistance | |||

| Resistance of all nosocomial Gram-negative pathogens in urine cultures | |||

| Resistant to three or all four of the antibiotics tested*5 | n=49 of 434 (11%) | n=18 of 373 (5%) | –6% (RR –57%. OR 0.40. CI 0.23–0.70; p=0.001)*5 |

*1Urine cultures with nosocomial pathogens are known to be suitable for monitoring the treatment of nosocomial infections and were thus selected for that purpose here. The reduction in antibiotic use in phase 2 of the study was accompanied by a more favorable pattern of resistance on the part of Gram-negative pathogens. particularly E. coli. Comparison of microbiological findings in 2010–2011 (liberal use of antibiotics) and 2012–2013 (structured use of antibiotics).

*2.The test procedure was changed to comply with the EUCAST guidelines in phase 2. Therefore these four antibiotics were chosen because they were tested in over 95% of cultures.

*3Numbers may differ from total because some samples were not tested assuming polysensitivity

*4.Natural resistance of Pseudomonas to ampicillin and cefuroxime or of Klebsiella to ampicillin; resistance was assessed by the criteria conventionally used in the year concerned (= data expressed as % of total). Antibiotics that were not tested (usually in the case of polysensitivity to other antibiotics) were exclusively rated as sensitive for comparison of multiple resistance.

*5Given the antibiotics tested. this is not equivalent to multiple resistance of Gram-negative bacteria to three or all four classes of antibiotics (3-. 4-MRGN); the antibiotics used to define 3-. 4-MRGN were published in the Bundesgesundheitsblatt in September 2011 (after the beginning of our study period) and were not investigated here.

*6Comparison of resistance by means of Pearson’s chi-square test: absolute difference with relative risk reduction (RR). odds ratio (OR). and 95% confidence interval (CI)

n.s.. not significant

The overall proportion of blood cultures demonstrating methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in patients with nosocomial sepsis decreased from 39% (7 of 18) in phase 1 to 25% (5 of 20) in phase 2; however, the difference was not statistically significant (eTable 3).

eTable 3. Microbiological characteristics of blood cultures in sepsis*1.

| Microbiological characteristics | Phase 1: liberal use of antibiotics 2010–2011 | Phase 2: structured use of antibiotics 2012–2013 | Change from phase 1 (2010–2011) to phase 2 (2012–2013) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood culture events in patients with sepsis | |||

| Pathogen spectrum of blood cultures in all patients with sepsis | n=558 | n=544 | |

| No bacteria demonstrated in blood culture (n [%]) | 209 (38%) | 170 (31%) | −7% (RR -18%. OR 0.76. CI 0.59–0.97; p=0.03) |

| Demonstration of two or more bacteria in blood culture (n [%]) | 59 (11%) | 50 (9%) | −2% n. s. |

| MSSA (n [%]) | 31 (6%) | 41 (8%) | +2% n. s. |

| MRSA (n [%]) | 16 (3%) | 12 (2%) | −1% n. s. |

| CNS (n [%]) | 99 (18%) | 86 (16%) | −2% n. s. |

| Streptococci (n [%]) | 38 (7%) | 40 (7%) | +/-0% n. s. |

| Various Gram-positive bacteria (n [%]) | 12 (2%) | 12 (2%) | +/-0% n. s. |

| Escherichia coli (n [%]) | 60 (11%) | 83 (15%) | +4% (RR +42%. OR 1.49. CI 1.05–2.13; p=0.03) |

| Klebsiella (n [%]) | 5 (1%) | 19 (4%) | +3% (RR +290%. OR 4.0. CI 1.48–10.80; p=0.006) |

| Proteus (n [%]) | 5 (1%) | 9 (2%) | +1% n. s. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n [%]) | 7 (1%) | 5 (1%) | +/-0% n. s. |

| Various Gram-negative bacteria (n [%]) | 13 (2%) | 6 (1%) | −1% n. s. |

| Anaerobes/fungi (n [%]) | 4 (1%) | 11 (2%) | +1% n. s. |

| Pathogen spectrum of all patients with sepsis (A40–A41) as principal diagnosis | |||

| Community-acquired (no hospital stay in preceding 30 days) | n=255 | n=284 | |

| No bacteria demonstrated in blood culture (n [%]) | 86 (34%) | 70 (25%) | −9% (RR −27%. OR 0.64. CI 0.44–0.94; p=0.02) |

| Demonstration of two or more bacteria in blood culture (n [%]) | 26 (10%) | 25 (9%) | −1% n. s. |

| MSSA (n [%]) | 8 (3%) | 16 (6%) | +3% n. s. |

| MRSA (n [%]) | 6 (2%) | 4 (1%) | −1% n. s. |

| CNS (n [%]) | 38 (15%) | 46 (16%) | +1% n. s. |

| Streptococci (n [%]) | 27 (11%) | 25 (9%) | −2% n. s. |

| Various Gram-positive bacteria (n [%]) | 7 (3%) | 11 (4%) | +1% n. s. |

| Escherichia coli (n [%]) | 39 (15%) | 56 (20%) | +5% n. s. |

| Klebsiella (n [%]) | 2 (1%) | 10 (4%) | +3% n. s. |

| Proteus (n [%]) | 3 (1%) | 8 (3%) | +2% n. s. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n [%]) | 4 (2%) | 3 (1%) | −1% n. s. |

| Various Gram-negative bacteria (n [%]) | 8 (3%) | 3 (1%) | −2% n. s. |

| Anaerobes/fungi (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 7 (3%) | +2% n. s. |

| Sepsis (A40–A41) as secondary diagnosis | |||

| Nosocomial | n=155 | n=121 | |

| No bacteria demonstrated in blood culture (n [%]) | 63 (41%) | 48 (40%) | +1% n. s. |

| Demonstration of two or more bacteria in blood culture (n [%]) | 19 (12%) | 15 (12%) | +/-0% n. s. |

| MSSA (n [%]) | 11 (7%) | 15 (12%) | +5% n. s. |

| MRSA (n [%]) | 7 (5%) | 5 (4%) | −1% n. s. |

| CNS (n [%]) | 34 (22%) | 13 (11%) | −11% (RR −51%. OR 0.43. CI 0.22–0.85; p=0.02) |

| Streptococci (n [%]) | 3 (2%) | 8 (7%) | +5% n. s. |

| Various Gram-positive bacteria (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | −1% n. s. |

| Escherichia coli (n [%]) | 10 (7%) | 12 (10%) | +3% n. s. |

| Klebsiella (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 2 (2%) | +1% n. s. |

| Proteus (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | −1% n. s. |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | +/-0% n. s. |

| Various Gram-negative bacteria (n [%]) | 3 (2%) | 1 (1%) | −1% n. s. |

| Anaerobes/fungi (n [%]) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | +/-0% n. s. |

*1The pathogen spectrum remained essentially unchanged in phase 2. The increase in positive blood cultures. i.e.. the reduction in blood cultures without demonstration of bacteria and the decrease in CNS could be attributed to improved pre-analysis.

*2Expressed in percent and rounded. difference calculated from rounded percentages. The German coding guidelines define the diagnosis leading to hospital admission as the principal diagnosis (ICD code A40–A41 for sepsis). Nosocomial and community-acquired sepsis were not distinguished. All cases of sepsis were therefore assessed individually according to the genesis of sepsis. “All patients with sepsis” thus includes both nosocomial and community-acquired sepsis whether assigned as principal or secondary diagnosis (n=1102). The most important groups are therefore community-acquired sepsis as principal diagnosis (n=539) and nosocomial sepsis as secondary diagnosis (n=276). The following groups are not specifically listed: patients with a principal diagnosis of nosocomial sepsis (in most cases acquired during a stay in our or another hospital <30 days before admission) and patients with a secondary diagnosis of community-acquired sepsis (admission owing to another principal diagnosis with accompanying sepsis).

RR. relative risk reduction; OR. odds ratio; CI. 95% confidence interval; MRSA. methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA. methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus; CNS. coagulase-negative staphylococci; n. s.. not significant

Discussion

The introduction of training sessions and clear guidelines on antibiotic use achieved a 32% reduction in consumption of antibiotics (DDD/case) in a 312-bed hospital. A study in China demonstrated a decrease of 50% (25).

At the same time, mortality went down among patients with sepsis or pneumonia in our study. This association was not causal in nature. Patients with sepsis continued to receive antibiotics. Despite a more restrictive antibiotic prescription policy, patients with sepsis were still discriminated accurately from those without sepsis. The fact that regulation of antibiotic prescription did not lead to increased mortality in this population is positive.

Limitations

The limitations of this study include its observational character and the restriction to a single hospital. Moreover, the patients with sepsis were not classified with regard to severity (e.g., by using the APACHE score). The reduction in mortality may have been due to many different factors. The increased likelihood of survival can also be explained by improvements in intensive care practices or a change in attitude in the diagnosis of sepsis. Overdiagnosis of sepsis in phase 2 of the study can be ruled out, because the prevalence did not increase. Effects of out-of-hospital antibiotic treatment were not systematically recorded; however, we do not believe that there was any essential change in strategy.

Decreasing mortality in patients with sepsis has been reported previously. In the USA, for instance, sepsis mortality was 27.9% in 1979 but fell to 17.9% by 2000 (26). An Australian study of patients with severe sepsis found a reduction in mortality from 35.0% to 18.4% over a 12-year period (2000 to 2012) (27). However, the patients in these studies, with a mean age of 57 to 64 years, were on average more than 10 years younger than our patients, whose mean age was 75 years. Age is known to be an important trigger of mortality, and the Goslar district, where the Asklepios Hospital is situated, is one of the regions of Germany with the highest average age (28). This is one reason for frequent treatment restrictions. The proportion of patients with MRSA on admission (data from the MRSA module of the German Hospital Infection Surveillance System, KISS), at 2.2%, is double the overall mean prevalence for Germany. Training in hygiene was intensified in our institution in 2012, so the reduction in cases of MRSA sepsis is not necessarily explained by reduced antibiotic consumption.

The fall in the number of cases of nosocomially aquired sepsis as secondary diagnosis is not easily explained. It may be that unnecessary antibiotic treatment leads to selection of resistant bacteria or, in the case of infusions, to device-associated infections. Improvements in hygiene management could also be responsible.

The volume of microbiological diagnostic procedures remained above average throughout the observation period. Increased resistance of enterobacteria to betalactams (29, 30) has been described with the switch of resistance testing to EUCAST sensitivity testing. In phase 2 of our study, however, there were fewer cases of resistance, which cannot be explained by the change to a different testing strategy. The reduction in resistance of nosocomially acquired bacteria in urine cultures cannot be explained by the decreased antibiotic consumption alone. The observation that resistance did not increase is important, however.

The marked reduction in the prescription of reserve antibiotics (cefepime, linezolid, tigecycline) is an important finding; among other things, it helps to explain the 47% decrease in costs. In contrast, there was increased prescription of ceftriaxone. This should be viewed critically and indicates the need for closer regulation, i.e., planned time-dependent changes in medication (cycling).

Summary

Optimized patient management must, on one hand, _enable immediate recognition of patients with severe sepsis so that they can receive the appropriate treatment. On the other hand, patients without sepsis must also be identified promptly in order to avoid unnecessary antibiotic treatment. A similar strategy was recently reported in a study of postoperative patients in the USA (31); waiting for the microbiology findings before deciding on the treatment was associated with reduced mortality.

Antibiotic stewardship programs should not focus only on the types of antibiotics but should also provide clear guidelines and thus encourage physicians to forgo antibiotics altogether in many cases. Reserve antibiotics should only be given when indicated. In a further step, attention should be focused on individualized antibiotic management, including treatment duration, dosage, and dose interval (24). This was not included in the scope of our study; higher study staffing would be required.

Furthermore, microbiological monitoring—of tracheal secretions, urine from long-term catheter wearers, skin and wound swabs—on the basis of which no treatment is usually indicated should be differentiated from diagnostic investigations following which treatment is generally required—pathogenic bacteria in blood cultures, cerebrospinal fluid, ascites, and pleura. There should also be heightened awareness of the possibility of contamination (coagulase-negative staphylococci in blood cultures, Candida spp. in secretions, etc.). This can only be achieved by means of regular interdisciplinary discussion of hygiene and microbiological topics.

The results of this study lead us to conclude that reduction of hitherto liberal administration of antibiotics is feasible. Quite clearly, patient safety does not suffer; indeed, there may even be a positive impact on patients’ prognosis and the spectrum of nosocomially related bacteria. Randomized double-blind studies of antibiotic use in severely ill patients are undoubtedly problematic from the ethical viewpoint. Larger prospective studies are warranted and will have to be coordinated at national level.

Figure 1b.

Pocket algorithm for suspected urinary tract infection

Figure 1c.

Pocket algorithm for suspected sepsis

PCT, procalcitonin; SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome

Key Messages.

Consistent guidelines and staff training achieved a significant decrease in antibiotic prescription density in a 312-bed acute hospital with previously liberal use of antibiotics.

The prescription density of all antibiotics went down by 24% from 67.1 defined daily doses (DDD)/100 patient days in the period 2010–2011 to 51.0 DDD/100 patient days in 2012–2013 (odds ratio [OR] 0.51, 95% confidence interval [95% CI] 0.50–0.52; p <0.001), while the DDD/case fell by 32%.

Decreased antibiotic prescription density was associated with reduced mortality in patients with sepsis (31% in 2010–2011 vs 19% in 2012–2013; OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.37–0.76; p = 0.001) and pneumonia (12% in 2010–2011 vs 6% in 2012–2013; OR 0.48, 95% CI 0.24–0.96; p = 0.038).

Overall mortality also fell significantly from n = 623/20 954 (3.0%) to n = 576/22 719 (2.5%) (OR 0.85, 95% CI 0.76–0.95; p = 0.005).

The decrease in antibiotic prescription density was accompanied by a reduction in the resistance of hospital-acquired bacteria in urine cultures to three or four consistently tested antibiotics from n = 49/434 (11%) to n = 18/373 (5%) (OR 0.40, 95% CI 0.23–0.70; p = 0.001).

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Prof. Groß has received support for other research projects from Pfizer, Gilead, and Astellas; speaker’s fees from Pfizer, Gilead, Diasorin, and Biomérieux; and remuneration of travel costs from Pfizer, Gilead, Diasorin, Biomérieux, and Astellas.

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Ott E, Saathoff S, Graf K, Schwab F, Chaberny IF. The prevalence of nosocomial and community acquired infections in a university hospital—an observational study. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:533–540. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heublein S, Hartmann M, Hagel S, Hutagalung R, Brunkhorst FM. Abstract epidemiology of sepsis in German hospitals derived from administrative databases. Infection. 2013;41:71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lübbert C, John E, von Müller L. Clostridium difficile infection—guideline-based diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:723–731. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heublein S, Hartmann M, Hagel S, Hutagalung R, Brunkhorst FM. Epidemiologie der Sepsis in deutschen Krankenhäusern - eine Analyse administrativer Daten. Intensiv-News. 2013;4:1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Linnér A, Sundén-Cullberg J, Johansson L, Hjelmqvist H, Norrby-Teglund A, Treutiger CJ. Short- and long-term mortality in severe sepsis/septic shock in a setting with low antibiotic resistance: a prospective observational study in a Swedish University Hospital. Front Public Health. 2013;1 doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2013.00051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stevenson EK, Rubenstein AR, Radin GT, Wiener RS, Walkey AJ. Two decades of mortality trends among patients with severe sepsis: a comparative meta-analysis. Crit Care Med. 2014;42:625–631. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign guidelines committee including the pediatric subgroup. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of severe sepsis and septic shock: 2012. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:580–637. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31827e83af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garnacho-Montero J, Garcia-Garmendia JL, Barrero-Almodovar A, Jimenez FJ, Perez-Paredes C, Ortiz-Leyba C. Impact of adequate empirical antibiotic therapy on the outcome of patients admitted to the intensive care unit with sepsis. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2742–2751. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000098031.24329.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vallés J, Rello J, Ochagavía A, Garnacho J, Alcalá MA. Community-acquired bloodstream infection in critically ill adult patients: impact of shock and inappropriate antibiotic therapy on survival. Chest. 2003;123:1615–1624. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.5.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kollef MH, Sherman G, Ward S, Fraser VJ. Chest. Inadequate antimicrobial treatment of infections: a risk factor for hospital mortality among critically ill patients. Chest. 1999;115:462–474. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.2.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaieski DF, Mikkelsen ME, Band RA, et al. Impact of time to antibiotics on survival in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock in whom early goal-directed therapy was initiated in the emergency department. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:1045–1053. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181cc4824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kumar A, Roberts D, Wood KE, Light B, Parrillo JE, Sharma S, et al. Duration of hypotension before initiation of effective antimicrobial therapy is the critical determinant of survival in human septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1589–1596. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000217961.75225.E9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar A, Ellis P, Arabi Y, et al. Cooperative antimicrobial therapy of septic shock. Database Research Group. Initiation of inappropriate antimicrobial therapy results in a fivefold reduction of survival in human septic shock. Chest. 2009;136:1237–1248. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Braun JP, Kumpf O, Deja M, et al. The German quality indicators in intensive care medicine - second edition. GMS German Medical Science. 2013;11 doi: 10.3205/000177. www.egms.de/static/en/journals/gms/2013-11/000177.shtml (last accessed on 22 July 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rangel-Frausto MS, Pittet D, Costigan M, Hwang T, Davis CS, Wenzel RP. The natural history of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) JAMA. 1995;273:117–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Deutsches Institut für Medizinische Dokumentation und Information. Was versteht man unter SIRS? www.dimdi.de/static/de/klassi/faq/icd-10/icd-10-gm/maticd-sirs-def-2007-1007.pdf. (last accessed on 22 July 2015)

- 18.Dalhoff K, Ewig S. on behalf of the Guideline Development Group: Clinical Practice Guideline: Adult patients with nosocomial pneumonia—epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:634–640. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bundesministerium für Gesundheit. www.bmg.bund.de/fileadmin/dateien/Publikationen/Gesundheit/Broschueren/Deutsche_Antibiotika_Resistenzstrategie_DART_110331.pdf. Berlin: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2011. Deutsche Antibiotika-Resistenzstrategie (DART) (last accessed on 22 July 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behnke M, Hansen S, Leistner R. Nosocomial infection and antibiotic use—a second national prevalence study in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2013;110:627–633. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2013.0627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hauer T. Antibiotikamanagement-Programme-das zweite Standbein der Infektionskontrolle. Krankenhaushygiene up2date. 2010;5:293–307. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bundesamt für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit, Paul-Ehrlich-Gesellschaft für Chemotherapie e.V. http://www.bvl.bund.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/08_PresseInfothek/Germap_2012.pdf?__blob=publicationFile&v=2. Freiburg: Germap; Infektiologie. (last accessed on 16 August 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robert-Koch-Institut. ARS - Antibiotika-Resistenz-Surveillance in Deutschland. https://ars.rki.de. (last accessed on 22 July 2013).

- 24.With de K, Allerberger F, Amann S, et al. Arbeitsgemeinschaft der Wissenschaftlichen Medizinischen Fachgesellschaften e. V.: S3 Leitlinie Antibiotika Anwendung im Krankenhaus. www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/092-001l_S3_Antibiotika_Anwendung_im_Krankenhaus_2013-12.pdf. (last accessed on 22 July 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lidao B, Rui P, Yi W, et al. Significant reduction of antibiotic consumption and patients’ costs after an action plan in china, 2010-2014. PloS one. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin GS, Mannino DM, Eaton S, Moss M. The epidemiology of sepsis in the United States from 1979 through 2000. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1546–1554. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa022139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaukonen KM, Bailey M, Suzuki S, Pilcher D, Bellomo R. Mortality related to severe sepsis and septic shock among critically ill patients in Australia and New Zealand, 2000-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:1308–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Berlin-Institut für Bevölkerung und Entwicklung./ www.berlin-institut.org/fileadmin/user_upload/Demenz/Demenz_online.pdf. (last accessed on 22 July 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu PY, Shi ZY, Tung KC, et al. Antimicrobial resistance to cefotaxime and ertapenem in Enterobacteriaceae: the effects of altering clinical breakpoints. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2014;8:289–296. doi: 10.3855/jidc.3335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polsfuss S, Bloemberg GV, Giger J. Comparison of European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and CLSI screening parameters for the detection of extended-spectrum β -lactamase production in clinical Enterobacteriaceae isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:159–166. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hranjec T, Rosenberger LH, Swenson B, Metzger R, Flohr TR, Politano AD, et al. Aggressive versus conservative initiation of antimicrobial treatment in critically ill surgical patients with suspected intensive-care-unit-acquired infection: a quasi-experimental, before and after observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:774–780. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]