Abstract

Objective:

In the past decades economic sanctions have been used by different countries or international organizations in order to deprive target countries of some transactions. While the sanctions do not target health care systems or public health structures, they may, in fact, affect the availability of health care in target countries. In this study, we used media analysis to assess the impacts of recent sanctions imposed by the Central Bank of Iran in 2012 on access to medicines in Iran.

Methods:

We searched different sources of written news media including a database of nonspecialized weeklies and magazines, online news sources, web pages of daily newspapers and healthcare oriented weeklies from 2011 to 2013. We searched the sources using the general term “medicine” to reduce the chances of missing relevant items. The identified news media were read, and categorized under three groups of items announcing “shortage of medicines,” “medicines related issues” and “no shortage.” We conducted trend analyzes to see whether the news media related to access to medicines were affected by the economic sanctions.

Findings:

A total number of 371 relevant news media were collected. The number of news media related to medicines substantially increased in the study period: 30 (8%), 161 (43%) and 180 (49%) were published in 2011, 2012 and 2013, respectively. While 145 (39%) of media items referred to the shortage of medicines, 97 (26%) reported no shortage or alleviating of concerns.

Conclusion:

Media analysis suggests a clear increase in the number of news media reporting a shortage in Iran after the sanctions. In 2013, there were accompanying increases in the number of news media reporting alleviation of the shortages of medicines. Our analysis provides evidence of negative effects of the sanctions on access to medicines in Iran.

Keywords: Economic crisis, economic sanction, health, medicine, news media

INTRODUCTION

Medicines form an essential part of medical care and ensuring access of those in need to essential medicines is a globally emphasized objective.[1] Governments play an important role in ensuring access to and rational use of medicines. Issue of access to medicine is among the most serious considerations in health systems, and it is still considered one of their main challenges.[2] Medicines consume an important part of the total health expenditures. In many low- and middle-income countries such proportion often is over 10% of the total health expenditures.[3] While in most low- and middle-income countries the users bear an important share of medicines costs as out of pocket expenditures, still social protection policies (such as general revenue expenditures or social insurance policies) are the responsible tools to improve access to medicines.

Implementing social protection policies prudently and effectively require an economic infrastructure that can be responsive to the population needs. Hence, economic hardship or crisis for whatever reason may result in the disorganization of policies and programs that provide social protection for medical care expenditures or results in deterioration in the availability of care including medicines. But the extent of these effects varies depending on the severity of the economic crisis and the government approach in response to the financial hardship, including the implementation of policies aimed at ensuring access to health care and medicines.[4,5,6] As an example, the recent global economic crisis in Europe resulted in financial hardship in countries such as Greece, Portugal and Ireland and might have resulted in a reduction in access to medicine and the quality of health care.[7]

Economic sanctions and their impacts on public health are similar to those of economic crises. This similarity is mainly through the loss of currency power and a rise in inflation that inevitably affects the ability of the country to obtain the required goods and services, including medicines. Sanctions may have different forms in terms of their economic aspects, their international or legal standing and the severity of their implementation. Economic sanctions are mainly applied in business or financial ways. Business sanctions may constraint or prevent different types of export and import relations or business interactions. Financial sanctions focus on financial links between countries, institutions or individuals. They limit the target countries via limiting access to investments, financing strategies or transactions.

Iran had suffered from a relatively continuous string of sanctions by certain international powers (e.g., the USA) since the Islamic revolution in 1979. These sanctions might have affected the country's economic status, still they targeted specific aspects of the economy and business relations. Since 2011, the country was put under extensive and widespread international sanctions. The manner of sanctions application in Iran involved targeting several financing and business aspects of the economy and culminated in targeting all international monetary transactions via stopping swift transactions and targeting the Central Bank of Iran.

Although medicines themselves were not under sanctions, the country seemed to encounter limitations in paying for any commodity needed inside the country.[5] The pharmaceutical industry of Iran includes 89 domestic production companies, 93 importers, 30 emergency medicine centers and 30 raw material suppliers.[8] National generic policies are always more successful with powerful domestic production, and Iran has achieved that. Therefore in recent history Iran had a reasonable level of access by the public to essential medicines and most needed pharmaceutical products.[8] Such a level of access had been achieved via implementing a national generic policy, enforcing an overarching pricing system for medicines throughout the country and establishing a widespread procurement and provision network for medicines.

Although there were still concerns about access to certain imported expensive medicines, and the growing costs of medicines, the country did not face a major public health problem in terms of access to medicines until 2011. Few academic literature and other reports raised concerns that the recent economic sanctions might have negatively affected access to medicines in Iran.[5,9,10,11] But methodological assessments of the potential effects of sanctions on medicines are still lacking. One-way of documenting of a country condition and also public concerns is through reviewing the media. News media may play an important role in highlighting problems, and magnifying, sensitizing, supporting, and even put pressure on policy makers.[12] Media has also played an important role in countries faced with economic crises to clarify the real situation and impacts of the crisis on public.[13] While there has been international media coverage of the potential impacts of sanctions on access to medicines in the country,[14,15] a thorough analysis of such content in Iran's local media may better reflect the public concerns about availability of important medicines and challenges reported by the general public when accessing needed medications. We conducted a time-series analysis of news media in Iran to answer the questions we raised above.

METHODS

Media content analysis includes a set of different methods that deal with the analysis of the articles, essays, and news distributed via media outlets to develop the relevant messages and concepts in order to interpret the media content.[16] In this study we conducted a simple written media content analysis in which we assigned a general message to each media content (e.g., a news or an “article”) and then quantified the monthly distribution of each general message as described below.

Sources of data

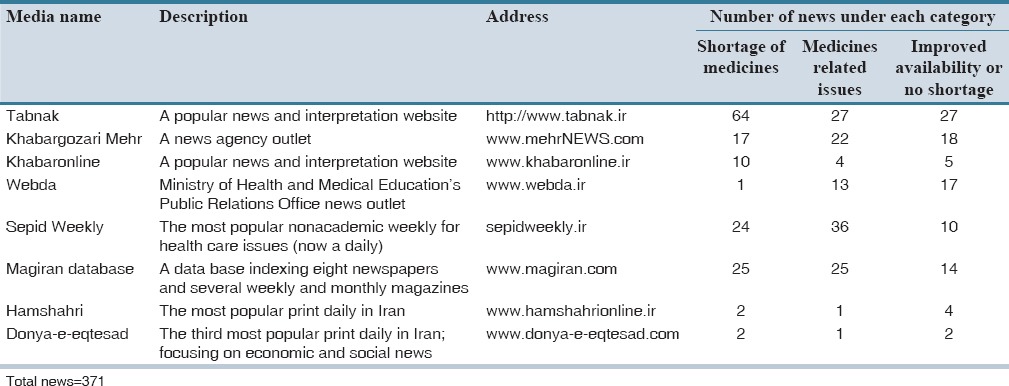

Sanctions on banking systems in Iran had been implemented since 2011. The effects of these sanctions peaked in March 2012 following an unprecedented sanction on the Central Bank of Iran. Given the impact of this sanction on all international banking transactions with the country, we looked at data from 2011 to 2013 covering at least 1-year before and 1-year after the sanctions implemented upon the Central Bank of Iran. We searched Magiran, a database of newspapers and magazines, over the period of the study [Table 1]. We also specifically searched three popular web outlets that published hundreds of news media and interpretations on a daily basis and two of the most popular broadsheet newspapers with interests in social and economic affairs. All these sources were nonspecialized sources of news and interpretations that covered a wide range of issues of public interest and concerns. Additionally we conducted searches of Iran's Ministry of Health and Medical Education news website (Webda), and a weekly magazine (“Sepid,” now a daily publication) that focused on health care news and events. The list of all the data sources is available in Table 1.

Table 1.

News media sources and the number of news identified under each category

Data collection

In order to ensure we capture all the relevant contents, we used a sensitive search strategy via searching for any content that included the words medicine or drug, and their Farsi translation (i.e., “Daru”). All the searches covered the study period from March 2011 to September 2013. Using a sensitive search strategy like this meant that we encountered many irrelevant news media; however it helped to ensure we would not miss the relevant medical content. As a result the identified news media that discussed medicines related issues that did not relate to the topic of the study were excluded. For example, such news media might discuss medicines dosage forms, new treatments for a disease, educational meetings or events, etc., All the identified news media were read to identify the ones that discussed or mentioned anything related to the availability, affordability or access to medicines, regardless of whether or not they directly mentioned the economic sanctions. Two authors checked the extracted data to diminish errors and increase the reliability and reproducibility of data extraction.

Data analysis

We categorized the content of each identified news media into one of the following three categories:

Media content that mentioned the continuation or exacerbation of a medicine (s) shortage or difficulty of access (i.e., “shortage of medicines”)

Discussing or mentioning sanction related concerns related to the availability, distribution, affordability or management of medicines without an explicit reference to a medicine shortage or nonaffordability (i.e., “medicines related issues”)

Improvement in availability and affordability of medicines or a lack of shortage (i.e., “improved availability or no shortage”).

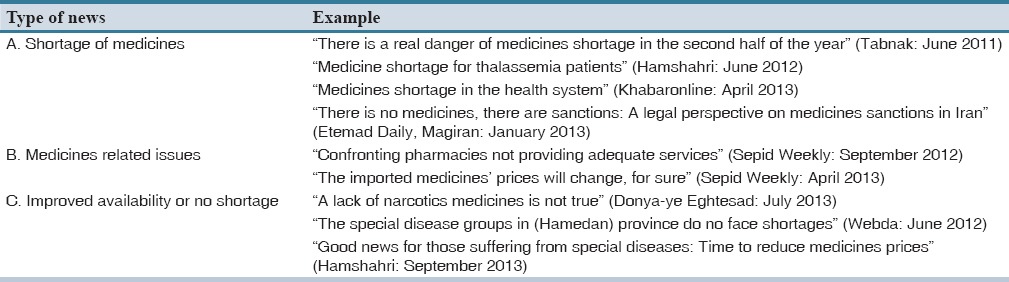

Occasionally, if we were in doubt about a relevant media content message, we gave careful attention for alternative potential meanings in the media text, and used our collective judgments to assign it to one of the above categories. Examples of news items for each category are demonstrated in Table 2.

Table 2.

Example extracts from selected news content used for categorization

The numbers of news media under each category were calculated and the 6-monthly collations of these counts were used to develop the data series and present the changes in media content during the study period. To provide a balance score of different news media categories in each time period, we arbitrarily assigned a value of + 1 to each category A media item, +0.5 to each category B media item, and − 1 to each category C media item, and developed the algebraic sums of media contents for monthly and seasonal analyses of the news media and presented the findings as charts and graphs. We hypothesized a priori that the Ministry of Health and Medical Education “Webda” news outlet might have been less willing to report medicines’ shortage concerns, and more willing to cover the news about availability (or restored availability) of medicines. Hence, we re-calculated the algebraic sums after removing the news media included in the study from Webda.

RESULTS

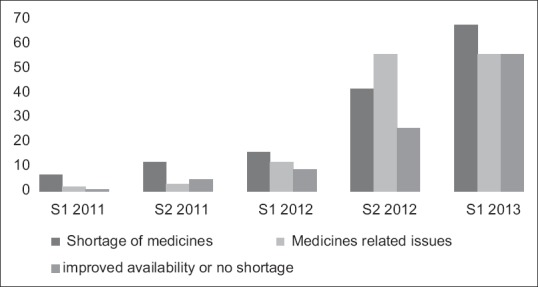

A total of 371 news media were categorized under the three groups after the review of the contents. The number of relevant items increased during the study period. While 2011 items accounted for 30 (8%) of the identified items, 161 (43.4%) and 180 (48.6%) of the identified items were published in 2012 and 2013, respectively [Figure 1]. The largest share of news media originated from the Tabnak (37%) and Magiran (17%). The minimum share related to Hamshahri and Donya-e-eqtesad newspapers with 1.8% and 1.3% respectively. Out of 371 items, 145 (39%) items reported “shortage of medicines,” 129 (35%) referred to “medicines related issues,” and 97 (26%) pertained to “improved availability or no shortage” (categories A, B and C, respectively).

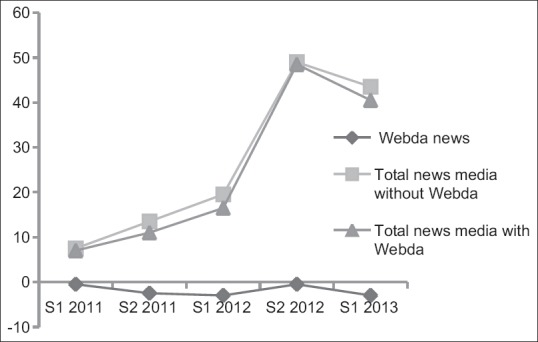

Figure 1.

Number of relevant news media in each category at 6 months intervals (2011–2012)

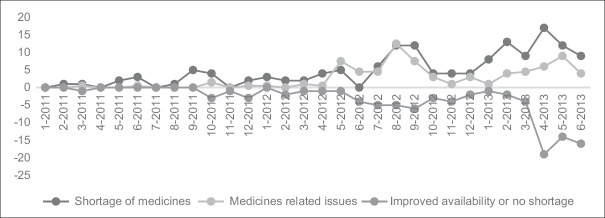

Figure 1 shows an increasing trend of all related news media during the studied period based on their content at 6 monthly intervals. As shown in this figure, their algebraic sum was positive in general and changed from + 7 during in the period April–June 2011 to + 40.5 during June–September 2013. We had hypothesized a priori that the Webda website, because of its affiliations to the Ministry of Health was likely to give a better coverage to “improved availability or no shortage” category of the news items. Hence, we assessed the trends after removing all the items reported in the Webda [Figure 2]. This did not change the results dramatically: A positive trend remained changing from + 7.5 in the second quarter of 2011 to + 43.5 in the first quarter of 2013. Figure 3 provides a monthly analysis of the identified items, demonstrating a clear surge in the number of related items since early March alongside with the peak of the economic sanctions inflicted upon Iran.

Figure 2.

Trend of algebraic sum of news media with and without Webda news (2011–2013)

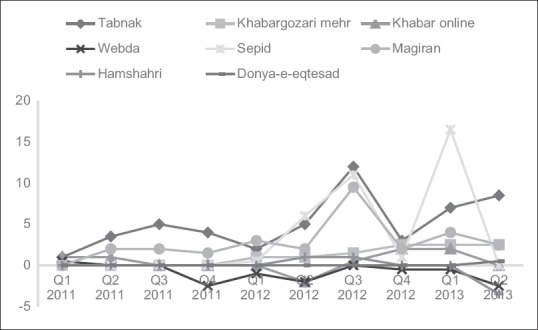

Figure 3.

Monthly trend of news media categorized by content (2011–2013)

A media source specific analysis of the content is presented in Figure 4. While the overall reports in the daily newspapers and the Webda were more toward alleviating shortage concerns, the rest of the sources were much more likely to report news of shortages in medicines. Daily published newspapers in Iran were the least likely to report any news about medicines concerns while the Webda predominantly reported news of “improved availability.”

Figure 4.

Seasonal trend of algebraic sum of news media based on each source (2011–2013)

DISCUSSION

We observed an increasing number of news media in Iran reporting contents related to access to medicines after the implementation of the economic sanctions upon the Central Bank of Iran. Assessing the trend of news media based on their content indicated that there was an increase in the news media which were informing about medicines shortages in Iranian pharmaceutical market after the implementation of the sanctions. This is despite the fact that the pharmaceutical market in Iran was not targeted by the sanctions and was exempted from the unilateral and multilateral economic sanctions inflicted upon Iran.[10,17]

Although we had focused on the local news media content in Iran for this analysis, there has been media coverage at the international level.[14] Despite these, we found no previous study that had assessed the reflections of diminishing access to medicines due to any economic hardship or sanctions in the media. As such, while there are published studies that have used media analysis to assess public policy impacts,[16] this is the first study that has used media analysis to assess the impact of sanctions (and indeed any economic hardship) on access to medicine or health care. Our findings should be interpreted in line with claims of negative impacts of previous international sanctions imposed on different countries on their health care, as well as the studies recently conducted in Europe after the economic crisis. A strong argument, supported by published evidence, has been presented in the report by Bossuyt that economic sanctions on several countries including Burundi, Cuba, and Iraq resulted in reduced access to essential health care in these countries despite the claims that the sanctions spared the health sector.[18] Also three studies assessed the impacts of economic crisis in Europe on health and demonstrated that the crisis influenced health sector through increasing public vulnerability and the increased inability of the health system to respond to the public needs and expectations because of limitations in resources.[6,19,20] In the study conducted by Buysse et al. to assess the impacts of the global financial crisis on the pharmaceutical sector, the results showed that both pharmaceutical consumption and expenditure reduced during the crisis.[21]

A similar pattern might have occurred in Iran. That is, despite the claims of the sanctions in sparing health care and medicines, they affected this sector dramatically. This effect might, in essence, be explained by the general economic hardship in the country. In Iran case, an additional factor of targeting the Central Bank might have also made it more difficult to use its existing financial resource to procure the required medicines from the international market. The peak of news media related to medicine shortage in Iran happened during June to September 2012, just after the implementation of the sanctions targeting the Central Bank. This was followed, perhaps as a result efforts to reduce the shortages and public concerns, by an increase in the number of news media reporting about the alleviation of the concerns over medicine shortages. The latter was coincided by the national presidential election in Iran resulting in an increasing expectation that the sanctions might ease in the country. Still the algebraic sum of the news media remained in favor of the ones reporting medicine shortage alongside the continuation of the sanctions. While there are reports that some of the shortages might have occurred due to the local mismanagement,[10] our study provides strong evidence that the media coverage of the issue, in fact, had followed the impact of severe sanctions, and the expectations that the sanctions might be eased.

Based on our findings, it is prudent to argue that effective policy making in response to sanctions might reduce the negative impacts of international sanctions and the shortages of medicines.[22] In another study, it has been argued that certain interventions implemented by Iran's Food and Drug Organization might have reduced the negative impacts of the sanctions on public health. The interventions included close monitoring of the market via regular meetings with the producers and importers, the establishment of a direct telephone line for reporting medicine shortages, and the establishment of an information center for drug shortages.[23] While this issue should be assessed further in the context of the sanctions, previous research have shown that effective policies in Latvia and Italy after economic crisis reduced the negative impacts on access to medicines in these countries.[24]

Still in none of these countries, the economic hardship resulted in difficulty of transaction of available financial resources, while the economic sanctions in Iran made it difficult for the country to pay for the goods and services it had to obtain from the international market, even when the funds were available.

Media analysis takes the pulse of public concerns through the analyzes of people's everyday challenges as presented in the media. It is almost extemporaneous. It has, however, the limitation that the partisan reports cannot be excluded, and there may be a bias toward sensational news and anecdotal evidence. As a result, it might be difficult to assess the validity of the news content. We tried to overcome these challenges by browsing a broad range of news sources and via including both newspapers and news databases. However, some over-reporting might not be excluded as news sources might reproduce news from major news agencies such as IRNA, creating a spinning effect for the same news. These limitations may apply to any media analysis study. However, to increase the validity of our findings, we assumed certain media outlets may have inherent biases, and considered that in our analyzes. Media analysis should, therefore, be used to identify the scope and the timing of a problem, which may then be investigated using other research methodologies.

The study used the media analysis to suggest that the widespread economic sanctions on Iran, while they did not target the pharmaceutical market in Iran, was very likely to have affected the worsening of medicines shortages in Iran.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

AR and MB conceived the study. MK and AR developed the methods, collected and analyzed the data. AR, MK and MB wrote the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Financial support and sponsorship

WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We received the financial support from the WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research to conduct this study, for which we are grateful to them.

WHO Alliance for Health Policy and Systems Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. MDG – Health and the Millennium Development Goals. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Methodology Report 2012 Stakeholder Review. Access to Medicine Foundation. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abdollahias A, Nikfar S, Abdollahi M. Pharmaceutical market and health system in the Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries: Time for innovations and changes in policies and actions. Arch Med Sci. 2011;7:365–7. doi: 10.5114/aoms.2011.23397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewis M, Verhoeven M. Washington: World Bank; 2010. Financial Crises and Social Spending, The Impact of the 2008-2009 Crisis. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheraghali AM. Impacts of international sanctions on Iranian pharmaceutical market. Daru. 2013;21:64. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rechel B, Suhrcke M, Tsolova S, Suk JE, Desai M, McKee M, et al. Economic crisis and communicable disease control in Europe: A scoping study among national experts. Health Policy. 2011;103:168–75. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vandoros S, Stargardt T. Reforms in the Greek pharmaceutical market during the financial crisis. Health Policy. 2013;109:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kebriaeezadeh A, Koopaei NN, Abdollahiasl A, Nikfar S, Mohamadi N. Trend analysis of the pharmaceutical market in Iran; 1997-2010; policy implications for developing countries. Daru. 2013;21:52. doi: 10.1186/2008-2231-21-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mohammadi D. US-led economic sanctions strangle Iran's drug supply. Lancet. 2013;381:279. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60116-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Namazi S. Dubai: Woodrow Wilson Center; 2013. Sanctions and Medical Supply Shortages in Iran. Viewpoints No. 20. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golzari S, Ghabili K, Mohammad Khanli H, Tizro P, Rikhtegar R. Access to cancer medicine in Iran. Lancet. 2013;381:279. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolfensohn J. Washington: World Bank; 2002. The Right to Tell: The Role of Mass Media in Economic Development. World Bank Institute Report. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chakravartty P, Dowing J. Media, technology, and the global financial crisis. Int J Commun. 2010;4:693–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Butler D. Iran hit by drug shortage. Nature. 2013;504:15–6. doi: 10.1038/504015a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamali Dehghan S. Iran Sanctions ’Putting Millions of Lives at Risk. The Guardian Daily. 2012 Oct 17; [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jönsson AM. Framing environmental risks in the Baltic Sea: A news media analysis. Ambio. 2011;40:121–32. doi: 10.1007/s13280-010-0124-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geneva: International Institute for Peace, Justice and Human Rights; 2013. The Impact of Sanctions on the Iranian People's Healthcare System. Ver 11. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bossuyt M. Geneva: Commission on Human Rights; 2000. The Adverse Consequences of Economic Sanctions. Economic and Social Council 21 June 2000; E/CN4/Sub 2//33. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Karanikolos M, Mladovsky P, Cylus J, Thomson S, Basu S, Stuckler D, et al. Financial crisis, austerity, and health in Europe. Lancet. 2013;381:1323–31. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60102-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kastanioti C, Kontodimopoulos N, Stasinopoulos D, Kapetaneas N, Polyzos N. Public procurement of health technologies in Greece in an era of economic crisis. Health Policy. 2013;109:7–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2012.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buysse IM, Laing RO, Mantel AK. Utrecht: Utrecht University; 2010. Impact of the economic recession on the pharmaceutical sector. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kheirandish M, Rashidian A, Kebriaeezade A, Cheraghali AM, Soleymani F. A review of pharmaceutical policies in response to economic crises and sanctions. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;4:115–22. doi: 10.4103/2279-042X.162361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hosseini SA. Impact of sanctions on procurement of medicine and medical devices in Iran; a technical response. Arch Iran Med. 2013;16:736–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Behmane D, Innus J. Pharmaceutical policy and the effects of the economic crisis: Latvia. Eurohealth. 2011;4:69–79. [Google Scholar]