Abstract

Objectives:

To assess potential roles of effector cells and immunologic markers in demyelinating CNS lesion formation, and their modulation by interferon β-1a (IFN-β-1a).

Methods:

Twenty-three patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) received IFN-β-1a for 6 months. Immunologic marker results were correlated with brain MRI lesion volumes, and volumes of normal-appearing brain tissue (NABT) with decreasing or increasing voxel-wise magnetization transfer ratio (VW-MTR), suggestive of demyelination and remyelination, respectively.

Results:

Baseline expression of Th22 cell transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and interleukin (IL)-17F, and percentages of IL-22–expressing CD4+ and CD8+ cells, were significantly higher in patients vs 15 healthy controls; IL-4 in CD4+ cells was lower. Baseline percentage of IL-22–producing CD8+ cells positively correlated with T2 lesion volumes, while percentage of IL-17A–producing CD8+ cells positively correlated with T2 and T1 lesion volumes. IFN-β-1a induced reductions in transcription factor AHR, T-bet, and retinoic acid–related orphan nuclear hormone receptor C (RORc) gene expression, while it increased GATA3's expression in CD4+ cells. Percentages of IL-22-, IL-17A-, and IL-17F-expressing T cells significantly decreased following treatment. Increased percentages of IL-10–expressing CD4+ and CD8+ cells correlated with greater NABT volume with increasing VW-MTR, while decreased percentage of IL-17F–expressing CD4+ cells positively correlated with decreased NABT volume with decreasing VW-MTR.

Conclusions:

Findings indicate that IFN-β-1a suppresses Th22 and Th17 cell responses, which were associated with decreased MRI-detectable demyelination.

Classification of evidence:

This pilot study provides Class III evidence that reduced Th22 and Th17 responses are associated with decreased demyelination following IFN-β-1a treatment in patients with RRMS.

In multiple sclerosis (MS), inflammatory cells induce blood–brain barrier permeability and migrate into the CNS,1 where antigen recognition propagates inflammatory responses leading to demyelination. CD4+ T cells are key mediators of the MS autoimmune response. Interferon (IFN)-γ–producing Th1 cells and interleukin (IL)-17A–producing Th17 cells contribute to inflammation,2 while IL-4–producing Th2 cells and transforming growth factor β1 (TGFβ1)– and IL-10–producing T regulatory cells (Treg) have immunoregulatory roles.3 IL-22–producing Th22 cells are a recently identified human T cell lineage, whose function and regulation are incompletely understood.4,5 Transcription factors mediating Th1, Th2, Th17, and Th22 cell differentiation (T-bet, GATA3, retinoic acid–related orphan nuclear hormone receptor C [RORc], and aryl hydrocarbon receptor [AHR], respectively) are reported to cross-regulate each other. In addition, IL-12 induces Th1 cell differentiation, and IL-4 induces Th2 differentiation. IL-6,6 IL-1β,7 TGFβ, IL-21,8 and IL-23 contribute to Th17 cell differentiation, while IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-27,9 IL-12, and IL-10 inhibit it.

Adoptive transfer of myelin-specific CD8+ T cells induces experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis,10 and activated CD8+ T cells secrete proinflammatory cytokines and express adhesion molecules, facilitating CNS infiltration.11 A high percentage of MS lesion CD8+ T cells expressed the proinflammatory cytokine IL-17.12

Voxel-wise magnetization transfer ratio (VW-MTR) is an advanced MRI technique sensitive to myelin changes. Decreasing and increasing VW-MTR volumes suggest demyelination and remyelination, respectively,13–17 which studies suggest can occur in parallel or sequence.

In this open-label, prospective pilot study, specific effector cells and immunologic markers potentially involved in demyelinating CNS lesion formation were evaluated at baseline and after 6 months of treatment with IFN-β-1a subcutaneously (SC) 3 times a week (Rebif; EMD Serono, Inc., Rockland, MA).

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01085318) was approved by the institutional review board and written informed consent was obtained from participants in accordance with Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study participants.

The study enrolled 23 patients with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) to undergo treatment with IFN-β-1a SC 3 times a week over 6 months, and 15 age- and sex-matched healthy controls (HCs), as recently reported.17 The inclusion criteria for patients were a diagnosis of RRMS according to the revised McDonald criteria,18 age 18 to 65 years, and treatment-naive or currently not receiving US Food and Drug Administration–approved disease-modifying therapies with a treatment-free period of 3 months before enrollment, as indicated in the recent clinical trial report.17 Participants were first treated in June 2010 and follow-up ended in February 2012, and the trial was conducted at a single center in Buffalo, NY. The sample size was based on clinical rather than statistical considerations.

Cell isolation.

Blood samples for immunologic studies were collected at baseline from HCs and at baseline and 6 months after IFN-β-1a SC treatment from patients with RRMS. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were separated by Ficoll density gradient (GE Healthcare Life Sciences, Pittsburgh, PA). CD4+ T cells and CD14+ monocytes were isolated from PBMCs using magnetic bead separation (Mylteni Biotech, San Diego, CA); purity was consistently >95%.

Quantitative reverse transcription–PCR.

Primers were purchased from Applied Biosystems (Grand Island, NY), and gene expression of transcription factors (T-bet, GATA3, RORc, interferon regulatory factor 4, forkhead box P3, and AHR), cytokines (IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A, IL-17F, IL-21, IL-22, and IL-10), cytokine receptors (IL-1R1, IL-23R, IL-21R, IL-12Rβ, and IL-27Rα), and neurotrophic factors nerve growth factor (NGF) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) were measured in CD4+ T cells by quantitative reverse transcription–PCR (qRT-PCR) using Taqman Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems). Similarly, gene expression of TLR3, 7, and 9; cytokines IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-23p19, TGFβ, IL-12p70, IL-10, and IL-27p28; and cytokine receptors IL-1R1, IL-12Rβ, IL-23R, IL-21R, and IL-27Rα was measured in CD14+-separated monocytes.19

Flow cytometry.

Fresh PBMCs were placed in serum-free medium and stimulated with PMA (50 ng/mL) and ionomycin (500 ng/mL; Sigma, St. Louis, MO) for 2 hours and brefeldin A (1:1,000 dilution; eBioscience, San Diego, CA) for an additional 3 hours for intracellular cytokine staining. Cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with fluorescein-conjugated antibodies against IFN-γ, IL-4, IL-17A, IL-21, IL-22 (eBioscience), IL-17F, BDNF (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN), IL-10, CD4, and CD8 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA).20 For NGF staining, cells were stained with primary antibody against NGF (Epitomics, Burlingame, CA), followed by fluorescein isothiocyanate–conjugated secondary antibody (BD Biosciences). Percentages of gated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells expressing each molecule were determined using a BD FACSCalibur Flow Cytometer and CellQuest software (BD Biosciences).

MRI acquisition.

Brain MRIs were performed using a 3T GE Signa LX Excite 12.0 scanner (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). Patients received a single dose (0.1 mM/kg) of gadolinium (Gd) contrast IV.

T2-weighted hyperintense and T1-weighted hypointense pre- and postcontrast lesion volumes were assessed using a semiautomated edge detection contouring/thresholding technique.21 T2 lesions were delineated on fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images and confirmed on proton density (PD) and T2 images. T1 hypointense lesions were delineated on T1 spin-echo images, and T1 Gd lesions were delineated on postcontrast T1 spin-echo images.

The VW-MTR maps were obtained using PD images obtained with and without magnetization transfer pulse with an offset of 1,200 Hz, described in detail previously.14 T1, T1 Gd-enhancing, T2/PD/FLAIR, MTR, and 3D T1-weighted images were coregistered using FSL's linear image registration tool (FMRIB, Oxford, UK). Three-dimensional T1-weighted images were segmented to classify voxels as gray matter, white matter, and CSF. VW-MTR difference maps were created by subtracting VW-MTR map pairs based on longitudinal time points. Voxels were classified as increasing or decreasing (suggesting remyelination or demyelination, respectively) within normal-appearing brain tissue (NABT), T2, T1, and T1 Gd-enhancing lesion volumes.17

Statistical analyses.

Differences in immunologic biomarkers between patients and HCs at baseline were compared using an unpaired t test. The change from baseline to 6 months for patients with RRMS was analyzed using a paired t test for each immunologic biomarker.

Spearman rank correlation was used to test the correlations between baseline immunologic measures and conventional MRI/VW-MTR measures, as well as between changes in each from baseline to 24 weeks posttreatment in all enrolled patients; this was also measured in a subgroup of patients who had ≥1 relapse in the 12 months before enrollment (active patient subgroup).

Since the purpose of these analyses was to explore the relationships between the immunologic and radiologic data, no p value adjustments for multiplicity were made.

Classification of evidence.

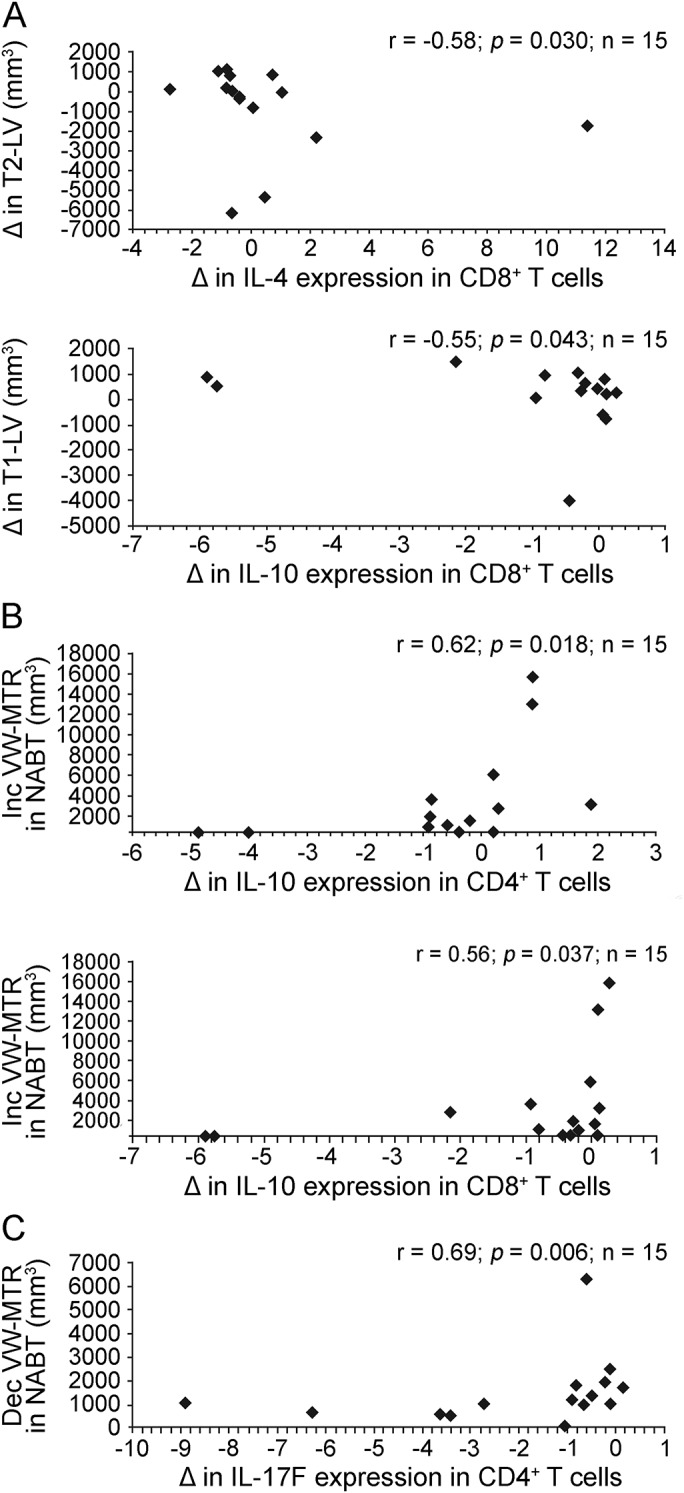

This research was designed to assess differences between patients with RRMS and HCs in immunologic biomarkers; to evaluate changes in immunologic biomarkers in patients with RRMS after treatment with IFN-β-1a; and to examine the relationships of immunologic biomarkers to demyelinating MRI brain lesion formation in patients with RRMS. Baseline gene expression of Th22 cell transcription factor AHR was increased 2.1-fold in the CD4+ T cells from patients compared with HCs (p = 0.044), and IL-17F gene expression was 1.9-fold higher (p = 0.026) in CD4+ T cells. Following 6 months of IFN-β-1a treatment, significant reductions were observed in CD4+ T cell gene expression of Th22 transcription factor AHR (2.2-fold; p = 0.035), Th1 transcription factor T-bet (1.9-fold; p = 0.011), and Th17 transcription factor RORc (1.6-fold; p = 0.024). Among patients with active disease, increased percentages of IL-10–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlated with a greater volume of NABT with increasing VW-MTR (r = 0.62, p = 0.018 and r = 0.56, p = 0.037, respectively), while decrease in the percentage of IL-17F–producing CD4+ T cells correlated with lower volume of NABT with decreasing VW-MTR (r = 0.69, p = 0.006). This study provides Class III evidence that reduced Th22 and Th17 responses are associated with less demyelination following IFN-β-1a treatment in patients with RRMS.

RESULTS

Patients with RRMS have increased Th17 and Th22 cytokine gene expression and intracellular IL-22 production by T cells compared with HCs.

A total of 23 patients with RRMS were enrolled; 21 patients (14 women, 9 men; age 39.9 [SD: 10.2] years) and 15 sex- and age-matched HCs (8 women, 7 men; age 36.7 [SD: 10.3] years) completed the study. There were no significant differences in demographic characteristics between the patient and HC groups.17 One patient with RRMS was lost to follow-up, and one was withdrawn by investigator's decision.

Post hoc analysis of the 15 patients with active disease (characterized by ≥1 relapse during the 12 months prior to study enrollment) found that baseline demographic characteristics of the patient subgroup were not significantly different from the total patient population (table e-1 at Neurology.org/nn).

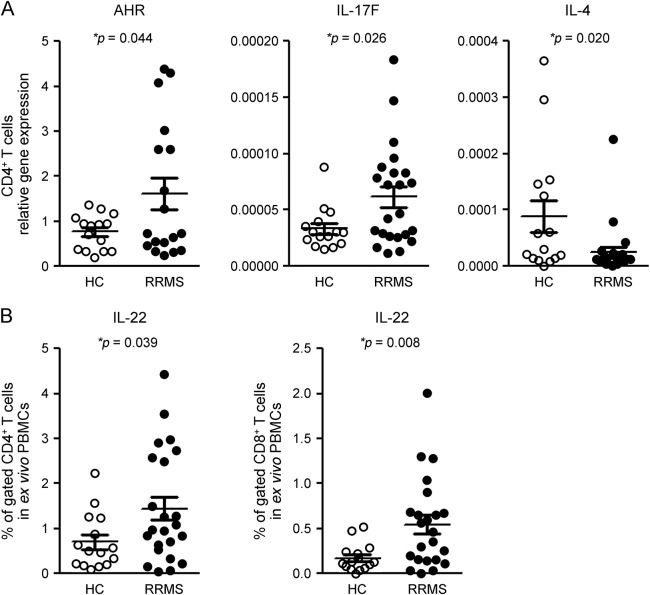

In comparison with HCs, baseline gene expression of Th22 cell transcription factor AHR was significantly increased (2.1-fold) in the CD4+ T cells of patients; IL-17F gene expression was also higher (by 1.9-fold) in CD4+ T cells from patients, while IL-4 gene expression was 3.6-fold lower (figure 1A).

Figure 1. Patients with RRMS have increased Th22 and Th17 cytokine gene expression and intracellular IL-22 production.

Gene expression of Th22 transcription factor AHR and of IL-17F, and the percentage of IL-22–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, are significantly increased in patients with RRMS in comparison with HCs, while IL-4 gene expression is decreased. (A) CD4+ T cells from 15 HCs and 23 patients with RRMS at baseline were separated using magnetic beads. Gene expression was measured using quantitative real time–PCR. Results are expressed as the relative gene expression normalized against 18S messenger RNA. Horizontal bars and error bars indicate the means and SDs, respectively. (B) Fresh PBMCs derived from the same 15 HCs and 23 patients with RRMS were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for intracellular cytokine staining. Percentages of cells expressing IL-22 in gated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired t test. AHR = aryl hydrocarbon receptor; HC = healthy control; IL = interleukin; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

In comparison with HCs, intracellular cytokine staining studies demonstrated that the percentage of IL-22–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells at baseline was significantly increased (2.1-fold and 3.2-fold, respectively) in patients (figure 1B).

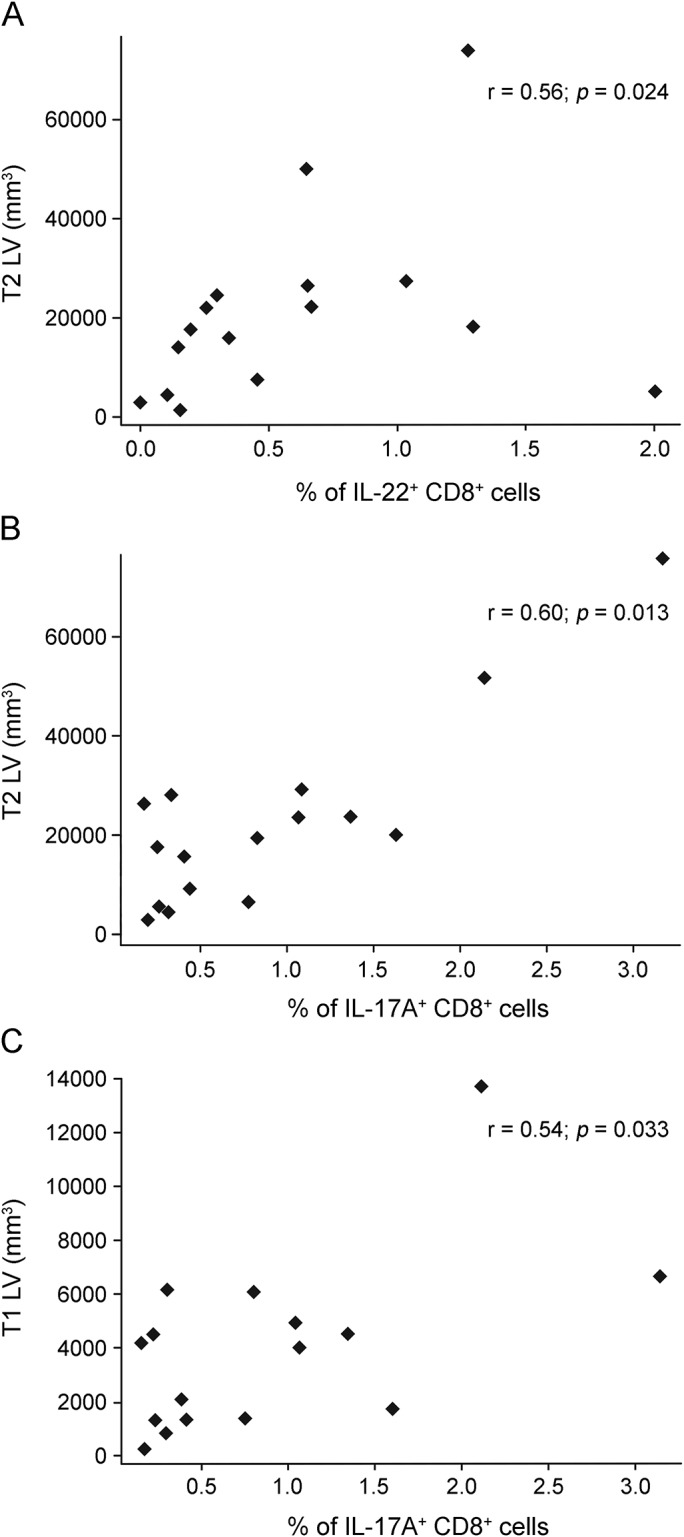

In the patient subgroup with active disease, baseline percentages of CD8+ cells expressing intracellular IL-22 correlated positively with baseline T2 lesion volume (r = 0.56, p = 0.024; figure 2A), while baseline percentages of CD8+ cells expressing intracellular IL-17A correlated positively with baseline T2 (r = 0.60, p = 0.013; figure 2B) and T1 (r = 0.54, p = 0.033; figure 2C) lesion volumes. Baseline T2 and T1 lesion volumes were highly positively correlated (r = 0.86, p < 0.001).

Figure 2. Baseline immunologic markers are associated with lesion volumes in patients with active disease.

Associations between baseline immunologic markers and lesion volume in the subgroup of patients with active disease (≥1 relapse in the year before baseline). (A) Baseline percentage of CD8+ T cells expressing intracellular IL-22 correlated positively with baseline T2 lesion volume. (B) Baseline percentages of CD8+ cells expressing intracellular IL-17A correlated positively with baseline T2 lesion volume. (C) Baseline percentages of CD8+ cells expressing intracellular IL-17A correlated positively with baseline T1 lesion volume. Fresh peripheral blood mononuclear cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for intracellular cytokine staining. Percentages of cells expressing IL-17A and IL-22 in gated CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were determined by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis was performed using Spearman rank correlation. IL = interleukin; LV = lesion volume.

In gene expression studies of CD4+ T cells from patients with RRMS, several significantly higher ratios of proinflammatory vs immunoregulatory cytokines in comparison with HCs at baseline were observed; these were ratios of IL-22, IL-17F, and IL-21 to IL-4, and IFN-γ to IL-10 (figure e-1A). Significantly higher ratios of CD4+ cells with intracellular expression of IL-22 to IL-4 and IL-21 to IL-4 were also identified at baseline in patients with RRMS compared with HCs (figure e-1B).

Gene expression studies of CD14+ monocytes revealed decreased baseline expression of IFNAR1 (1.8-fold) and IFNAR2 (2.0-fold) in patients in comparison with HCs (figure e-2).

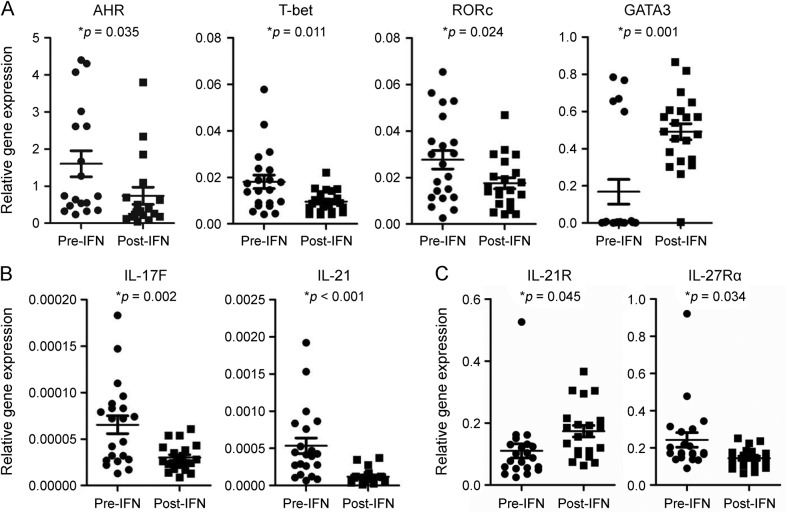

IFN-β-1a treatment inhibited Th22 and Th17 cytokine production in CD4+ cells.

After 6 months of treatment with IFN-β-1a, significant reductions were observed in CD4+ T cell gene expression of Th22 transcription factor AHR (2.2-fold), Th1 transcription factor T-bet (1.9-fold), and Th17 transcription factor RORc (1.6-fold), whereas expression of Th2 transcription factor GATA3 was significantly increased compared with baseline (2.9-fold; figure 3A).

Figure 3. IFN-β-1a treatment inhibits expression of Th22- and Th17-related genes in CD4+ cells.

IFN-β-1a treatment of patients with RRMS inhibited Th22, Th1, and Th17, while inducing Th2 cell-related gene expression in CD4+ T cells. CD4+ T cells from 21 patients with RRMS at baseline and month 6 after IFN-β-1a treatment were separated using magnetic beads. Gene expression of (A) transcription factors, (B) cytokines, and (C) cytokine receptors was measured using quantitative real time–PCR. Results are expressed as the relative gene expression normalized against 18S messenger RNA. Statistical analysis was performed using a paired t test. AHR = aryl hydrocarbon receptor; IFN-β-1a = interferon β-1a; IL = interleukin; RORc = retinoic acid–related orphan nuclear hormone receptor C; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

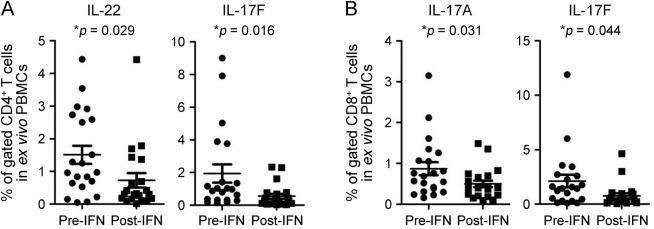

After treatment with IFN-β-1a, gene expression of IL-17F (2.2-fold), IL-21 (4.5-fold), and IL-27Rα (1.7-fold) was significantly reduced, while IL-21R gene expression was significantly increased (1.6-fold; figure 3, B and C) in separated CD4+ T cells. In addition, there were significant decreases in the percentages of IL-22– and IL-17F–expressing CD4+ T cells (2.1-fold and 3.5-fold, respectively; figure 4A), and in IL-17A– and IL-17F–expressing CD8+ T cells (1.7- and 2.8-fold, respectively; figure 4B).

Figure 4. IFN-β-1a treatment decreases the percentage of Th22 and Th17 cells.

IFN-β-1a treatment significantly decreased the percentages of IL-22– and IL-17F–producing CD4+ T cells (A), and IL-17A– and IL-17F–producing CD8+ T cells in patients with RRMS (B). Fresh PBMCs from 21 patients with RRMS at baseline and after 6 months of IFN-β-1a treatment were used for intracellular cytokine staining. The percentages of CD4+ or CD8+ T cells expressing indicated cytokines were determined by flow cytometry. Statistical analysis was performed using a paired t test. IFN-β-1a = interferon β-1a; IL = interleukin; PBMC = peripheral blood mononuclear cell; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.

IFN-β-1a SC treatment significantly reduced gene-expression ratios of AHR and T-bet to GATA3, IL-17F and IL-21 to IL-4, and IL-21 to IL-10 in CD4+ T cells compared with baseline (figure e-3A). Protein expression ratios of the percentage of CD4+ T cells expressing IL-22 and IL-17F to IL-4, and IL-22 to IL-10, were also significantly reduced (figure e-3B).

Finally, gene expression of TLR9 and IL-23p19 was significantly decreased (1.5- and 4.5-fold, respectively), while IL-21R gene expression was significantly increased (1.7-fold) in CD14+ monocytes (figure e-4).

Decreased percentage of IL-17–producing CD4+ cells induced by IFN-β-1a treatment correlates with decreased demyelination, while increased percentage of IL-10–producing CD4+ and CD8+ cells correlates with increased remyelination in NABT.

In the subgroup of patients with active disease, an anti-inflammatory effect of IFN-β-1a, associated with increase in the percentage of IL-4–expressing CD8+ T cells, correlated with greater decrease in the volume of T2 lesions, representing the total brain lesion burden accumulated over the duration of the disease. Similarly, an increase in the percentage of IL-10+ CD8+ cells inversely correlated with hypointense T1 lesion volume, which reflects more advanced lesions characterized by axonal loss. The immunologic markers and MRI readout changes were from baseline to 6 months, as measured by conventional MRI (figure 5A). In addition, increased percentages of IL-10–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlated with greater volume of NABT with increasing VW-MTR (figure 5B), while decrease in the percentage of IL-17F–producing CD4+ T cells correlated with lower volume of NABT with decreasing VW-MTR (figure 5C).

Figure 5. Changes in immunologic markers correlate with demyelination or remyelination on brain MRIs: Baseline to 6 months.

A decrease in the percentage of IL-17–producing CD4+ cells induced by IFN-β-1a treatment correlates with decreased demyelination, while increase in the percentage of IL-10–producing CD4+ and CD8+ cells correlates with increased remyelination in NABT. Subgroup analysis was performed in 15 patients with RRMS with ≥1 relapse during the 12 months preceding study entry. (A) Patients with RRMS with active disease had flow cytometry study and 25 conventional brain MRI at baseline and 6 months after IFN-β-1a therapy. Correlation between changes in the percentage of IL-4– and IL-10–producing CD8+ cells and T2 and T1 lesion volume from baseline to 6 months posttherapy was tested using Spearman correlation test. (B) Correlation between changes in the percentage of IL-10–expressing CD4+ and CD8+ cells and increasing VW-MTR NABT volume indicating remyelination from baseline to 6 months of IFN-β-1a treatment. (C) Correlation between change in the percentage of IL-17F–expressing CD4+ T cells and NABT volume with decreasing VW-MTR indicating demyelination from baseline to 6 months. Dec = decreasing; IFN-β-1a = interferon β-1a; IL = interleukin; Inc = increasing; LV = lesion volume; NABT = normal-appearing brain tissue; RRMS = relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis; VW-MTR = voxel-wise magnetization transfer ratio.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we found several differences in the baseline immunologic profile of patients in comparison with HCs. Gene expression of Th22 transcription factor AHR in CD4+ T cells and the percentages of IL-22–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in patients compared with HCs. Baseline gene expression studies also revealed increased IL-17F and decreased IL-4 cytokine gene expression in patients, as well as higher ratios of IL-22, IL-17F, and IL-21 relative to IL-4, and IFN-γ relative to IL-10 cytokine gene expression in patients compared with HCs.

Notably, at baseline among patients with active disease, the percentage of IL-22–producing CD8+ T cells correlated positively with brain T2 lesion volume, and the percentage of IL-17A–producing CD8+ T cells correlated positively with T2 and T1 lesion volume, suggesting an involvement of those cytokines in the pathogenesis of MS lesions.

Gene expression studies in CD14+ monocytes revealed decreased baseline expression of IFNAR1 and IFNAR2 in patients, which may reflect decreased endogenous IFN-β secretion and signaling in RRMS, as recently reported by our laboratory.22

Our previous studies have reported that IFN-β-1a inhibited CD4+-naive T cell differentiation to Th17 cells,23 suppressed the secretion of Th17-polarizing cytokines in human dendritic cells,2 decreased antigen-presenting capacity of B cells and inhibited their secretion of IL-1β and IL-23, and induced IL-12, IL-27, and IL-10 secretion.23 The aim of the present study was to evaluate treatment effects of IFN-β-1a on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and on CD14+ monocytes, as well as to investigate associations between inflammatory markers in RRMS and ongoing events suggestive of demyelination and remyelination in NABT and MS lesions following treatment with IFN-β-1a.

In this study, we found that IFN-β-1a treatment resulted in significant downregulation of gene expression of the Th22 transcription factor AHR and decreased percentage of IL-22+ CD4+ cells, which may represent a novel mechanism of action of IFN-β-1a. Th22 cells secrete IL-22 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and coexpress the chemokine receptors CCR4, CCR6, and CCR10. Both RORc and AHR control the production of IL-22, but AHR more selectively affects Th22 cell differentiation.5 Multiple studies have indicated that Th22 cells are involved in the pathogenesis of inflammatory disorders4,24–27; however, only a few studies have addressed the role of this cell subset in MS. A recent study found that serum IL-22 levels and the percentages of Th22 cells are significantly increased in patients with MS.28 The number of Th22 cells is increased in the peripheral circulation and CSF of patients with RRMS in comparison with HCs, particularly before clinical relapses. Th22 cells from patients with MS are reactive to myelin basic protein and express CCR6, a CNS homing chemokine receptor.29 In contrast to our results revealing inhibition of Th22 cell numbers following IFN-β treatment, this study did not identify inhibition of Th22 cells following short-term in vitro IFN-β treatment, which was associated with a decreased IFNAR1 expression on this cell subset.

In addition to the Th22 cell inhibition following IFN-β-1a treatment in our study, gene expression of Th1 transcription factor T-bet and Th17 markers RORc, IL-17F, and IL-21 was inhibited, while gene expression of Th2 transcription factor GATA3 was increased, demonstrating effect of IFN-β-1a on multiple CD4+ T cell subsets. Treatment also reduced the percentages of IL-17F–producing CD4+ T cells and IL-17A– and IL-17F–producing CD8+ T cells, which is consistent with multiple previous reports of the inhibitory effect of IFN-β-1a on the differentiation and expansion of Th17 cells.30,31 We propose that the inhibition of IL-27Rα gene expression in CD4+ T cells of patients following treatment with IFN-β-1a likely reflects increased IL-27 signaling,32,33 which in turn suppresses Th17 cell differentiation.9 The observed induction of IL-21R expression in CD4+ T cells and in IL-21R gene expression in CD14+ monocytes may reflect a negative feedback loop following decreased secretion of IL-21, perhaps contributing to the inhibition of Th17 responses mediated by IFN-β-1a treatment.

Transcription factor AHR to GATA3, and T-bet to GATA3 gene expression ratios decreased significantly after treatment with IFN-β-1a. In addition, the significant inhibition of the gene expression ratios of IL-17F and IL-21 to IL-4, and IL-21 to IL-10, as well as the ratios of CD4+ T cell numbers expressing IL-17F and IL-22 to IL-4, and IL-22 to those expressing IL-10, would suggest a rebalance of the immune system as a result of treatment.

In CD14+ monocytes, IFN-β-1a treatment significantly inhibited gene expression of TLR9, consistent with the inhibitory effects of IFN-β-1a on TLR9 processing in patients with MS.34 IL-23 is one of the key cytokines that induces human Th17 cell differentiation.6 In this study, IFN-β-1a SC treatment inhibited gene expression of IL-23p19 in monocytes, which may also contribute to the IFN-β-1a–mediated inhibition of Th17 response.

In the measurement of immunology markers following treatment in the active patient subgroup, an increased percentage of immunoregulatory IL-4– and IL-10–producing CD8+ T cells correlated with decreasing T2 and T1 lesion volume in the conventional brain MRI, respectively. With advanced MRI outcomes, the increase in the percentages of IL-10–producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells correlated positively with NABT volume changes suggestive of remyelination, while the observed decrease in the numbers of proinflammatory IL-17F–producing CD4+ cells correlated positively with decreased volume of NABT with decreasing VW-MTR, which suggests less demyelination. In contrast, previous studies did not identify correlations between TNF-β, TNFR1, TNFR2, IL-4, IL-10, and IFN-γ and brain lesion volumes as measured by conventional MRI.35 Seasonal fluctuations of IFN-γ and TNF-α did not correlate with the number of active MRI lesions.36

Over the course of the treatment period, 5 patients experienced clinical exacerbations.17 However, when we analyzed their immunologic marker expression in comparison to the remaining 18 patients who responded favorably to IFN-β-1a treatment, we did not identify any statistically significant changes in the immunologic marker expression between the 2 groups. The treatment period of 6 months may have been too short to assess responsiveness to IFN-β-1a SC in RRMS. Thus, longer-term analysis of immunologic measures would be valuable and should take into account patient subpopulations (e.g., disease activity and treatment history that may influence the immunologic status of patients). Longer duration and larger sample size than was included in this pilot study are needed to draw conclusions regarding the effect of IFN-β-1a on immunologic measures in patients with RRMS.

Treatment with IFN-β-1a resulted in the inhibition of proinflammatory Th22 and Th17 responses, suggesting an anti-inflammatory mechanism of action, while immunoregulatory markers induced during the treatment course correlated with imaging changes suggestive of remyelination.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank Sara Hussein (Buffalo Neuroimaging Analysis Center, Department of Neurology, State University of New York at Buffalo) for technical assistance with imaging, and Esther Law and Chris Grantham of Caudex Medical for editorial assistance in the preparation of the manuscript. The authors also thank Manisha Chopra (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for study coordination and Neal Bhat (University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) for assistance with qRT-PCR experiments.

GLOSSARY

- AHR

aryl hydrocarbon receptor

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- Gd

gadolinium

- HC

healthy control

- IFN-β-1a

interferon β-1a

- IL

interleukin

- MS

multiple sclerosis

- NABT

normal-appearing brain tissue

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PBMC

peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PD

proton density

- qRT-PCR

quantitative reverse transcription–PCR

- RORc

retinoic acid–related orphan nuclear hormone receptor C

- RRMS

relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis

- SC

subcutaneous

- TGF

transforming growth factor

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- Treg

T regulatory cell

- VW-MTR

voxel-wise magnetization transfer ratio

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org/nn

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yazhong Tao, Xin Zhang, and Silva Markovic-Plese: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, and drafting of the manuscript. Robert Zivadinov: study concept and design, acquisition of data, and analysis and interpretation of data. Brooke Hayward and Fernando Dangond: study concept and design and analysis and interpretation of data. Michael G. Dwyer, Cheryl Kennedy, Niels Bergsland, Deepa Ramasamy, Jacqueline Durfee, David Hojnacki: acquisition of data. All authors provided critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

STUDY FUNDING

The study was supported by EMD Serono.

DISCLOSURE

Y. Tao received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from EMD Serono. X. Zhang consulted for EMD Serono, Inc. R. Zivadinov received speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, Claret, EMD Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, is a section editor for BMC Neurology for demyelinating diseases, consulted for Biogen Idec, Clare, EMD Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Teva Pharmaceuticals, and received research support from Biogen Idec, Claret, EMD Serono, Novartis, Sanofi-Genzyme, and Teva Pharmaceuticals. M.G. Dwyer is on the scientific advisory board for EMD Serono, has consulted for Claret Medical, and received research support from Novartis. C.L. Kennedy, N. Bergsland, D. Ramasamy, and J. Durfee report no disclosures. D. Hojnacki received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen, Teva, EMD Serono, and Genzyme, has consulted for Biogen, EMD Serono, Teva, and Genzyme, is on the speakers bureau for Biogen, EMD Serono, Teva, Pfizer, and Genzyme. B. Hayward is employed by EMD Serono. F. Dangond is employed by EMD Serono. B. Weinstock-Guttman is on the scientific advisory board for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, received travel funding and/or speaker honoraria from Biogen Idec, Teva Neuroscience, EMD Serono, Pfizer, Novartis, Acorda, Genzyme/Sanofi, and Questcor, is on the editorial board for Multiple Sclerosis International, BMJ Neurology Journal of Multiple Sclerosis, has consulted for Biogen Idec, Teva Neuroscience, EMD Serono, Novartis, Acorda, Mylan, Questcor, and Genzyme/Sanofi, is on the speakers bureau for Biogen Idec, Teva Neuroscience, EMD Serono, Genzyme, Genetech, and Novartis, received research support from Biogen Idec, EMD Serono, Teva Novartis, Acorda, Genzyme/Sanofi, Questcor, NIH, National MS Society, and DOD. S. Markovic-Plese is on the advisory board for Genzyme, Serono EMD, Chugai Inc., and received research support from Biogen Idec, Novartis, Chugai Inc., Genzyme Inc., EMD Serono, NIH/NINDS, and NMSS. Go to Neurology.org/nn for full disclosure forms.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Immunol 2005;23:683–747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Jin J, Tang Y, Speer D, Sujkowska D, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta1a inhibits the secretion of Th17-polarizing cytokines in human dendritic cells via TLR7 up-regulation. J Immunol 2009;182:3928–3936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wan YY, Flavell RA. TGF-beta and regulatory T cell in immunity and autoimmunity. J Clin Immunol 2008;28:647–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. J Clin Invest 2009;119:3573–3585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Trifari S, Kaplan CD, Tran EH, Crellin NK, Spits H. Identification of a human helper T cell population that has abundant production of interleukin 22 and is distinct from T(H)-17, T(H)1 and T(H)2 cells. Nat Immunol 2009;10:864–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhou L, Ivanov II, Spolski R, et al. IL-6 programs T(H)-17 cell differentiation by promoting sequential engagement of the IL-21 and IL-23 pathways. Nat Immunol 2007;8:967–974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Acosta-Rodriguez EV, Napolitani G, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Interleukins 1beta and 6 but not transforming growth factor-beta are essential for the differentiation of interleukin 17-producing human T helper cells. Nat Immunol 2007;8:942–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yang L, Anderson DE, Baecher-Allan C, et al. IL-21 and TGF-beta are required for differentiation of human T(H)17 cells. Nature 2008;454:350–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amadi-Obi A, Yu CR, Liu X, et al. TH17 cells contribute to uveitis and scleritis and are expanded by IL-2 and inhibited by IL-27/STAT1. Nat Med 2007;13:711–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huseby ES, Liggitt D, Brabb T, Schnabel B, Ohlen C, Goverman J. A pathogenic role for myelin-specific CD8(+) T cells in a model for multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med 2001;194:669–676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bao M, Hanabuchi S, Facchinetti V, et al. CD2AP/SHIP1 complex positively regulates plasmacytoid dendritic cell receptor signaling by inhibiting the E3 ubiquitin ligase Cbl. J Immunol 2012;189:786–792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tzartos JS, Friese MA, Craner MJ, et al. Interleukin-17 production in central nervous system-infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol 2008;172:146–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deloire-Grassin MS, Brochet B, Quesson B, et al. In vivo evaluation of remyelination in rat brain by magnetization transfer imaging. J Neurol Sci 2000;178:10–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwyer M, Bergsland N, Hussein S, Durfee J, Wack D, Zivadinov R. A sensitive, noise-resistant method for identifying focal demyelination and remyelination in patients with multiple sclerosis via voxel-wise changes in magnetization transfer ratio. J Neurol Sci 2009;282:86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tjoa CW, Benedict RH, Dwyer MG, Carone DA, Zivadinov R. Regional specificity of magnetization transfer imaging in multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimaging 2008;18:130–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zivadinov R. Advanced magnetic resonance imaging metrics: implications for multiple sclerosis clinical trials. Methods Find Exp Clin Pharmacol 2009;31:29–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zivadinov R, Dwyer MG, Markovic-Plese S, et al. Effect of treatment with interferon beta-1a on changes in voxel-wise magnetization transfer ratio in normal appearing brain tissue and lesions of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 24-week, controlled pilot study. PLoS One 2014;9:e91098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Polman CH, Reingold SC, Banwell B, et al. Diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: 2010 revisions to the McDonald criteria. Ann Neurol 2011;69:292–302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang X, Jin J, Peng X, Ramgolam VS, Markovic-Plese S. Simvastatin inhibits IL-17 secretion by targeting multiple IL-17-regulatory cytokines and by inhibiting the expression of IL-17 transcription factor RORC in CD4+ lymphocytes. J Immunol 2008;180:6988–6996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X, Tao Y, Chopra M, et al. Differential reconstitution of T cell subsets following immunodepleting treatment with alemtuzumab (anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody) in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2013;191:5867–5874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zivadinov R, Heininen-Brown M, Schirda CV, et al. Abnormal subcortical deep-gray matter susceptibility-weighted imaging filtered phase measurements in patients with multiple sclerosis: a case-control study. Neuroimage 2012;59:331–339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao Y, Zhang X, Chopra M, et al. The role of endogenous IFN-beta in the regulation of Th17 responses in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Immunol 2014;192:5610–5617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ramgolam VS, Sha Y, Jin J, Zhang X, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta inhibits human Th17 cell differentiation. J Immunol 2009;183:5418–5427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Duhen T, Geiger R, Jarrossay D, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Production of interleukin 22 but not interleukin 17 by a subset of human skin-homing memory T cells. Nat Immunol 2009;10:857–863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ma HL, Liang S, Li J, et al. IL-22 is required for Th17 cell-mediated pathology in a mouse model of psoriasis-like skin inflammation. J Clin Invest 2008;118:597–607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Geboes L, Dumoutier L, Kelchtermans H, et al. Proinflammatory role of the Th17 cytokine interleukin-22 in collagen-induced arthritis in C57BL/6 mice. Arthritis Rheum 2009;60:390–395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cobrin GM, Abreu MT. Defects in mucosal immunity leading to Crohn's disease. Immunol Rev 2005;206:277–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu W, Li R, Dai Y, et al. IL-22 secreting CD4+ T cells in the patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol 2013;261:87–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rolla S, Bardina V, De Mercanti S, et al. Th22 cells are expanded in multiple sclerosis and are resistant to IFN-beta. J Leukoc Biol 2014;96:1155–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Durelli L, Conti L, Clerico M, et al. T-helper 17 cells expand in multiple sclerosis and are inhibited by interferon-beta. Ann Neurol 2009;65:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweeney CM, Lonergan R, Basdeo SA, et al. IL-27 mediates the response to IFN-β therapy in multiple sclerosis patients by inhibiting Th17 cells. Brain Behav Immun 2011;25:1170–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1680–1690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Prinz M, Schmidt H, Mildner A, et al. Distinct and nonredundant in vivo functions of IFNAR on myeloid cells limit autoimmunity in the central nervous system. Immunity 2008;28:675–686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Balashov KE, Aung LL, Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Dhib-Jalbut S, Weiner HL. Interferon-beta inhibits toll-like receptor 9 processing in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 2010;68:899–906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus J, Kuehne BS, Tofighi J, et al. Serum cytokine levels do not correlate with disease activity and severity assessed by brain MRI in multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand 2002;105:300–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Killestein J, Rep MH, Meilof JF, et al. Seasonal variation in immune measurements and MRI markers of disease activity in MS. Neurology 2002;58:1077–1080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.