Abstract

Large proportion of Asian populations have moderate to severe periodontal disease and a substantial number are anticipated to be at high risk of cardiovascular diseases (CVD). This study reviews epidemiology and association of periodontal and CVDs from the South-Asian region. Observational studies and clinical trials published during January 2001–December 2012 focusing association between periodontitis and CVDs in South-Asian countries were retrieved from various databases and studied. Current evidence suggests that both periodontal and CVDs are globally prevalent and show an increasing trend in developing countries. Global data on epidemiology and association of periodontal and CVDs are predominantly from the developed world; whereas Asia with 60% of the world's population lacks substantial scientific data on the link between periodontal and CVDs. During the search period, 14 studies (5 clinical trials, 9 case–controls) were reported in literature from South-Asia; 100% of clinical trials and 77% case–control studies have reported a significant association between the oral/periodontal parameters and CVD. Epidemiological and clinical studies from South-Asia validate the global evidence on association of periodontal disease with CVDs. However, there is a need for meticulous research for public health and scientific perspective of the Periodontal and CVDs from South-Asia.

Keywords: Cardiovascular diseases, periodontal diseases, South-Asian countries

INTRODUCTION

Periodontal and cardiovascular diseases (CVD) are prevalent globally. In Asia, the periodontal disease remains at higher levels[1] and CVDs are predicted to rise to epidemic levels.[2] In developed and developing countries, CVDs are one of the leading causes of death and the main underlying pathological process is atherosclerosis. No single factor can account for all the causes of CVD, and a considerable section of CVD patients do not carry any of the traditional risk factors like hypertension, smoking, obesity, hypercholesterolemia or genetic predisposition.[3,4]

Scientific evidence regarding the link between CVDs and emerging risk factors that also include infectious and/or inflammatory diseases is growing. Epidemiological, pathological, microbiological and immunological studies show that infectious agents, such as periodontopathic pathogens and inflammatory markers in the blood have been correlated with increased risk of CVD.[5] Inflammatory biomarkers including high-sensitive C-reactive protein (CRP), fibrinogen, serum amyloid A, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and cellular adhesion molecules are known CVD risk markers.[6] Scientists have explored the potential mechanisms of association between periodontal disease and CVDs. As a result, different theories have emerged that include: The theory of bacterial invasion, the cytokine theory, the autoimmunization theory.[7]

Global data on epidemiology and association between periodontal and CVDs is predominantly from the developed world; the corresponding situation in Asian countries which are going to face an increasing burden of noncommunicable diseases including CVDs, are not well studied.[8] In this review paper, we have explored and analyzed relevant scientific literature to account for the level of evidence available on the status and association of periodontal and CVDs from South-Asian region including Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, and Nepal.

METHODOLOGY

Databases (January 2001 to December 2012), including MedLine, EMBASE, Google scholar, Scopus and Web of Science were searched by the PubMed interface on December 2012, using the following MeSH headings: “Periodontal disease, periodontitis, or periodontal therapy,” and “CVD, coronary heart disease (CHD), coronary artery disease, stroke, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease,” and global, Asian countries, developed/developing countries.”

All articles on observational (cohort, case–control, cross-sectional) and intervention studies (comparison studies, randomized controlled trials,) and systematic reviews/meta-analysis investigating epidemiology and/or association between periodontal disease and CVDs were screened. Articles, not available in full text, printed in a language other than English, reporting association of periodontal disease with systemic condition (s) other than CVDs, and review papers were excluded. The electronic search yielded 1524 references and the inclusion criteria were relatively broadly specified to include articles, which have analyzed the epidemiology and association of periodontal conditions and CVDs with respect to the South-Asian perspective. Fourteen (14) most relevant articles were retrieved and analyzed for this paper. Articles were screened and retrieved by author (SAHB) and analyzed independently by authors (SAHB and GW) for inclusion in review. Authors (AAK and KWL) contributed in manuscript preparation.

RESULTS

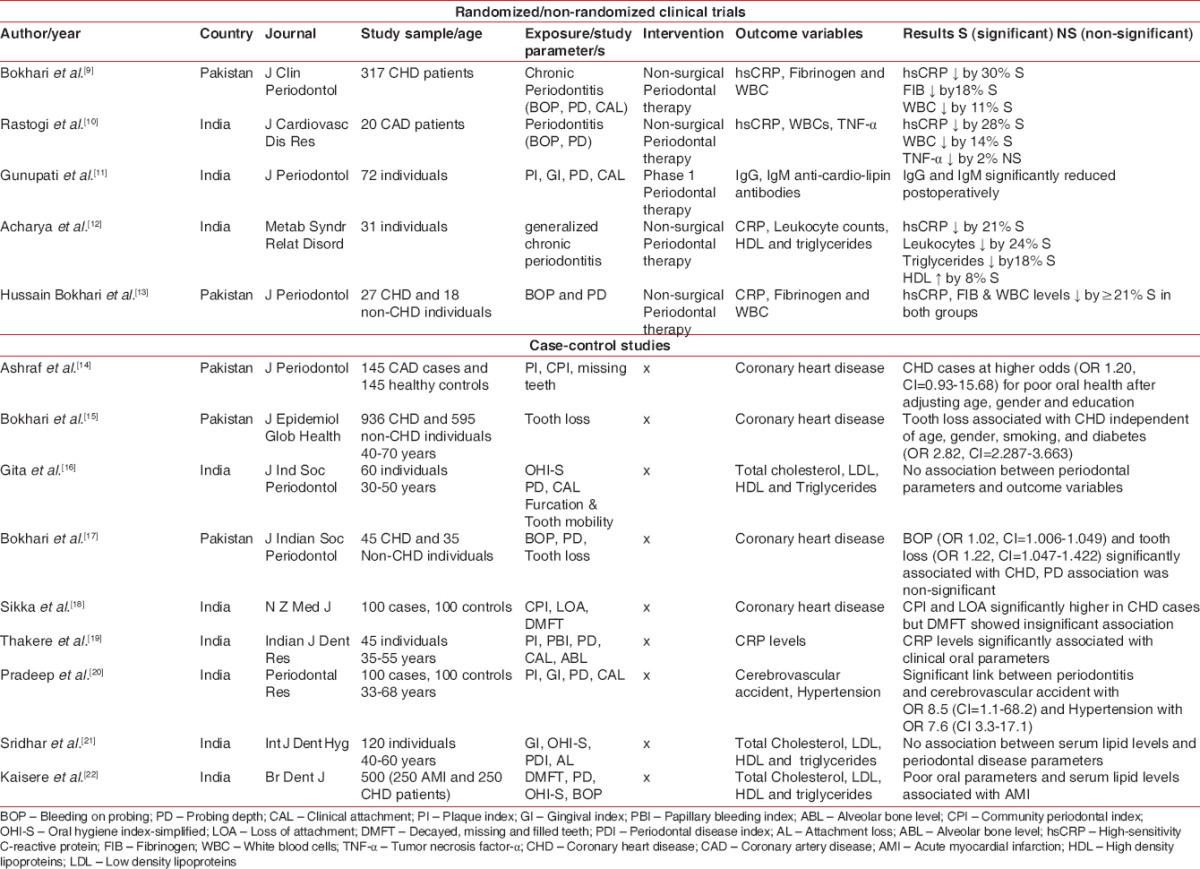

Scientific literature on the association of oral/periodontal and CVDs available from South-Asia includes five clinical/intervention trials,[9,10,11,12,13] nine case–control studies[14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] [Table 1].

Table 1.

South-Asian studies on “Perio-CVD” association: 2001-2012

All studies reported on the topic were either from India or Pakistan. Five randomized and nonrandomized trials were conducted in India and Pakistan. Indian researchers have contributed six case–control studies while three case–control studies have been reported from Pakistan. Five studies from Pakistan observed 2263 individuals and 9 Indian studies were conducted on 1248 individuals.

Oral parameters of bleeding on probing; probing depth; clinical attachment loss (AL)/level; plaque index; gingival index; papillary bleeding index; alveolar bone level; community periodontal index (CPI); oral hygiene index-simplified; loss of attachment; decayed, missing and filled teeth; periodontal disease index; AL; missing teeth and dental prosthesis were used in studies to measure status of oral/periodontal diseases. Systemic parameters of hsCRP, fibrinogen, white blood cells, TNF-α, IgG, IgM, high density lipoprotein (HDL), triglycerides, total cholesterol, IL-6, serum leptin, CHD, stroke, hypertension, acute myocardial infarction, and cardiac disease were noted as outcome measures.

Four hundred and eighty-five subjects were observed in 5 clinical trials for the effect of nonsurgical periodontal therapy on serum levels of hsCRP, fibrinogen, WBC, TNF-α, IgG, IgM, HDL and triglycerides. A significant reduction of ≥14% in all systemic parameters except TNF-α was observed in all trials.

Seven out of nine case–control studies showed a significant association of oral parameters and CHD/CVA/hypertension/total cholesterol, low density lipoprotein, HDL and triglycerides on 2846 individuals; however two studies conducted on 180 individuals reported no association between periodontal and systemic outcome parameters.

In summary, of the 14 studies, 12 studies (5 RCTs and 7 case–controls) suggested an association of oral/periodontal disease parameters with increased risk of cardiovascular outcome measures. Randomized trials showed that periodontal health may significantly reduce CVD associated risk markers.

DISCUSSION

The majority of the studies analyzed in this systematic review were from India and then from Pakistan, no study has been reported from Bangladesh, Nepal, and Sri Lanka. All studies have observed an association of oral/periodontal clinical parameters with various systemic biomarkers and systemic conditions of CHD, Stroke, and hypertension.

Tonetti and Claffey[23] noted variations in the epidemiology of periodontal disease (PD) because of the lack of uniformity in case definition of PD used in studies of different populations. Globally in all WHO regions, the most severe form of periodontal disease (CPI score 4) varies from 10% to 15% and the most prevalent form is gingival bleeding and calculus (CPI score 2) that reflects poor oral hygiene and lack of appropriate dental care.[24] Corbet et al.[1] reported periodontal status of low- and -middle income countries, and observed a very low percentage with healthy periodontal status (0–7%) and a high percentage of gingival bleeding and calculus (55–99%) in the younger age groups (15 years old) and shallow PD is not a common condition (0–20%), a higher prevalence, as high as 44%, of shallow pocket was observed in slightly older age groups. In Eastern Mediterranean Region (EMRO) periodontal diseases affect 95% of populations and 5–15% people are presented with bleeding gums, 40% with calculus, 20–25% with shallow pockets and 15% with deep pockets when measured through CPI.[25]

Cardiovascular diseases, the most prevalent category of systemic diseases in developed as well in developing countries,[26] are the prevailing noncommunicable ailment in the Indian subcontinent, and will become the major cause of mortality among inhabitants of South Asia in the next 20 years.[27] South Asian countries, namely Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan and Sri Lanka, not only represent a quarter of the world's population but also contribute to the highest proportion of CVD burden when compared with any other region globally.[28] Lifestyle changes resulting from urbanization, industrialization; economic transition and globalization are promoting increased prevalence of CVDs.[25,29] Risk factors of tobacco consumption, physical inactivity, unhealthy diet, including foliate deficiency and emerging risk factors such as chronic infections are common in the underprivileged populations of the low- and middle-income countries.[29] South Asian ethnicity per se is a risk factor for CVD that appeared to be independent of traditional risk factors.[26] CHD occurs at least 10 years earlier in South Asians as compared to other ethnic groups, and the average age of stroke is much lower than in the western countries.[30]

Asian Indians are at 3–4 times higher risk of coronary artery disease (CAD) than white Americans, 6 times higher than Chinese, and 20 times higher than Japanese.[31] Median age for first presentation of acute MI in the five South Asian populations is 53 years, whereas the corresponding age in Western Europe, China, and Hong Kong is 63 years, with more men than women affected.[32] The incidence of CHD has increased in Pakistan over the past three decades.[33] Two studies[34,35] have reported the status and gravity of stroke in Pakistan and have shown that 46% of the stroke patients had cardiac disease and 30% had hyperlipidemia, whereas carotid artery stenosis was noted in 8%. Peripheral artery disease (PAD) shares a common underlying pathological change, atherosclerosis, with CHDs and stroke.[36] The disease is reported to be under diagnosed, under treated, and poorly understood by the medical community and rate of death from myocardial infarction; stroke is increased in patients with symptomatic and asymptomatic peripheral arterial disease.[37] A recent study[38] reported incidence of peripheral arterial disease in 17.7% acute coronary syndrome (ACS) patients of Karachi, Pakistan.

Since Mattila et al.[39] reported the association of dental infections with CVD; researchers have tried to collect further evidence on the biological plausibility of this association. Over the last two decades, epidemiological, etiopathological and clinical studies have implicated periodontal disease as a risk factor for the development of CVD and suggested various pathways involved in the potential mechanism to link these conditions. A number of epidemiological studies[40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49] have suggested the role of infectious and inflammatory periodontal disease in the initiation/progression of CVD and have addressed the mechanisms by which periodontal disease may influence the development of CVD. The epidemiological evidence from South-Asia also support the notion observed in these studies.

Helfand et al.[4] reported a nonexplanatory nature of traditional risk factors for incident CHD and evaluated novel or emerging risk factors of CRP, coronary artery calcium score, lipoprotein level, homocysteine level, leukocyte count, fasting blood glucose, periodontal disease, ankle-brachial index, and carotid intima-media thickness which detection and/or control of any one factor might potentially contribute to improvement in global risk assessment for CHD. These emerging risk factors have been observed in case–control studies[14,15,17,18,19,20,22] from India and Pakistan and randomized trials[9,10,11,12,13] have provided evidence of reduction in serum levels by improving periodontal health.

The positive association of oral infections and tooth loss to CVDs has also been observed.[39,40,50,51,52,53,54] Few studies[55,56,57] reported a less convincing relationship or no association of oral health indicators (gingivitis, dental caries or tooth loss) with CVD or CHD; these findings correspond with the findings of studies[16,21] from South-Asia. However other studies[39,40,58,59,60,61,62,63,64] provided strong evidence regarding relationship between oral/periodontal diseases to CVDs and CHD. The relationship between PD and ischemic stroke has been studied, and the outcome is different across the various studies, ranging from total stroke to fatal stroke, nonfatal stroke, and ischemic stroke.[65,66,67] Men with periodontal disease or any tooth loss showed a significantly higher risk of peripheral arterial disease (PAD) than men without periodontitis or without any tooth loss during a follow-up period of study.[36] Mendez et al.[68] reported subjects with clinically significant periodontal disease were at higher risk of having PAD at baseline.

Poor oral health and CVD are major health problems worldwide and of significant public health importance. Evidence from epidemiological and clinical studies provides an insight into their potential association; therefore it is rational to investigate potential contributing mechanisms by periodontitis that could play a role in increasing someone's risk for CVDs. A higher prevalence of periodontal disease is observed in developing countries[69] and the five South-Asian countries have the highest rates of periodontal diseases and CVD. The much more prevalence and severe problem of periodontal disease in developing countries seems to be truly reflected by poorer oral hygiene and considerably more plaque retentive factors in the form of calculus, often evident in individuals at a young age.[70] Dietary habits[71] tooth brushing habits,[72] smoking, or tobacco use[73,74] alcohol use,[75] psychosocial,[76] and life style[77] factors related to the periodontal diseases have also been observed in CVD patients in Asian countries. Within the Asia and Oceania region, many countries still have poor economic status, high illiteracy levels and a very low dentist to population ratios.[1]

SUMMARY

Periodontal diseases are public health problem worldwide and more so in developing countries; the specific and unique needs of low-and middle-income countries and that of their poor and under-privileged population groups are to be identified and recognized for a population-based, national oral health program.[23] The health and economic implications of this staggering rise in early CVD deaths in South Asian countries are profound and warrant prompt attention from governing bodies and policymakers of these countries.

Although current scientific research proves deep connections of periodontal and CVDs; however in the absence of hard evidence (from Asia) that these diseases are of public health problems, these diseases remain outside of mainstream public health planning in the countries’ concern. The challenges, in developing countries, to address the increasing burden of CVD include low health budgets, education and skill of health care workforce.[78] The same challenges may contribute to poor oral health that is also associated with higher CVD risk. In view of the low socioeconomic status and high treatment cost, preventive measures need to be introduced to reduce morbidity and mortality of these chronic diseases. If unattended, growing levels of CVDs in South Asian countries may induce substantial economic and social impacts in the future. The limitations observed in the studies conducted on the topic in South Asian countries may be small sample sizes and single center. There is also lacking of large scale cross sectional studies.

RECOMMENDATIONS

On the basis of current evidence on the epidemiology and association of periodontal and CVDs in South Asian countries, there is a need to encourage meticulous research not only from scientific point of view but from public health perspective also. A multi-factorial risk screening and intervention approach at the population level could provide immediate benefit.[30] To slow the momentum of CVD in developing countries, major initiatives regarding promotion of diet and physical activity, creation of awareness among both sexes, or development of guidelines for risk reduction, appropriate therapeutic and surgical strategies, are needed to combat periodontitis and CVD.[31]

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Corbet EF, Zee KY, Lo EC. Periodontal diseases in Asia and Oceania. Periodontol 2000. 2002;29:122–52. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2002.290107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nishtar S, Bile KM, Ahmed A, Amjad S, Iqbal A. Integrated population-based surveillance of noncommunicable diseases: The Pakistan model. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:102–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong IW. Emerging relations between infectious diseases and coronary artery disease and atherosclerosis. CMAJ. 2000;163:49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Helfand M, Buckley DI, Freeman M, Fu R, Rogers K, Fleming C, et al. Emerging risk factors for coronary heart disease: A summary of systematic reviews conducted for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:496–507. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suzuki J, Aoyama N, Ogawa M, Hirata Y, Izumi Y, Nagai R, et al. Periodontitis and cardiovascular diseases. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2010;14:1023–7. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2010.511616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tzorbatzoglou ID, Sfyroeras GS, Giannoukas AD. Periodontitis and carotid atheroma: Is there a causal relationship? Int Angiol. 2010;29:27–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bartold PM, Meng H. An Asian perspective of periodontology. Periodontol 2000. 2011;56:11–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2010.00375.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bokhari SA, Khan AA, Butt AK, Azhar M, Hanif M, Izhar M, et al. Non-surgical periodontal therapy reduces coronary heart disease risk markers: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:1065–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01942.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rastogi P, Singhal R, Sethi A, Agarwal A, Singh VK, Sethi R. Assessment of the effect of periodontal treatment in patients with coronary artery disease: A pilot survey. J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2012;3:124–7. doi: 10.4103/0975-3583.95366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gunupati S, Chava VK, Krishna BP. Effect of phase I periodontal therapy on anti-cardiolipin antibodies in patients with acute myocardial infarction associated with chronic periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2011;82:1657–64. doi: 10.1902/jop.2011.110002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acharya A, Bhavsar N, Jadav B, Parikh H. Cardioprotective effect of periodontal therapy in metabolic syndrome: A pilot study in Indian subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2010;8:335–41. doi: 10.1089/met.2010.0002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hussain Bokhari SA, Khan AA, Tatakis DN, Azhar M, Hanif M, Izhar M. Non-surgical periodontal therapy lowers serum inflammatory markers: A pilot study. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1574–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashraf J, Hussain Bokhari SA, Manzoor S, Khan AA. Poor oral health and coronary artery disease: A case-control study. J Periodontol. 2012;83:1382–7. doi: 10.1902/jop.2012.110563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bokhari SA, Khan AA, Ansari JA, Alam R. Tooth loss in institutionalized coronary heart disease patients of Punjab Institute of Cardiology, Lahore, Pakistan. J Epidemiol Glob Health. 2012;2:51–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jegh.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gita B, Sajja C, Padmanabhan P. Are lipid profiles true surrogate biomarkers of coronary heart disease in periodontitis patients: A case-control study in a south Indian population. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2012;16:32–6. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.94601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bokhari SA, Khan AA, Khalil M, Abubakar MM, Rehman MU, Azhar M. Oral health status of CHD and non-CHD adults of Lahore, Pakistan. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 2011;15:51–4. doi: 10.4103/0972-124X.82273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sikka M, Sequeira PS, Acharya S, Bhat M, Rao A, Nagaraj A. Poor oral health in patients with coronary heart disease: A case-control study of Indian adults. N Z Med J. 2011;124:53–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thakare KS, Deo V, Bhongade ML. Evaluation of the C-reactive protein serum levels in periodontitis patients with or without atherosclerosis. Indian J Dent Res. 2010;21:326–9. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.70787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pradeep AR, Hadge P, Arjun Raju P, Shetty SR, Shareef K, Guruprasad CN. Periodontitis as a risk factor for cerebrovascular accident: A case-control study in the Indian population. J Periodontal Res. 2010;45:223–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2009.01220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sridhar R, Byakod G, Pudakalkatti P, Patil R. A study to evaluate the relationship between periodontitis, cardiovascular disease and serum lipid levels. Int J Dent Hyg. 2009;7:144–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1601-5037.2008.00318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kaisare S, Rao J, Dubashi N. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for acute myocardial infarction. A case-control study in Goans highlighting a review of the literature. Br Dent J. 2007;203:E5. doi: 10.1038/bdj.2007.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tonetti MS, Claffey N. European Workshop in Periodontology group C. Advances in the progression of periodontitis and proposal of definitions of a periodontitis case and disease progression for use in risk factor research. Group C consensus report of the 5th European Workshop in Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2005;32(Suppl 6):210–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Petersen PE, Ogawa H. The global burden of periodontal disease: Towards integration with chronic disease prevention and control. Periodontol 2000. 2012;60:15–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.2011.00425.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chronic Diseases and Health Promotion. Preventing Chronic Diseases a Vital Investment. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/chronic_diseases.htm .

- 26.Strategic Priorities of the Cardiovascular Disease Program. [Last accessed on 2012 Dec 12]. Available from: http://www.who.int/cardiovasculardiseases/priorities/

- 27.Goyal A, Yusuf S. The burden of cardiovascular disease in the Indian subcontinent. Indian J Med Res. 2006;124:235–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramaraj R, Chellappa P. Cardiovascular risk in South Asians. Postgrad Med J. 2008;84:518–23. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2007.066381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reddy KS, Yusuf S. Emerging epidemic of cardiovascular disease in developing countries. Circulation. 1998;97:596–601. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.6.596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gupta R, Misra A, Vikram NK, Kondal D, Gupta SS, Agrawal A, et al. Younger age of escalation of cardiovascular risk factors in Asian Indian subjects. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2009;9:28. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-9-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma M, Ganguly NK. Premature coronary artery disease in Indians and its associated risk factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1:217–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yusuf S, Hawken S, Ounpuu S, Dans T, Avezum A, Lanas F, et al. Effect of potentially modifiable risk factors associated with myocardial infarction in 52 countries (the INTERHEART study): Case-control study. Lancet. 2004;364:937–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17018-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aziz K, Aziz S, Patel N, Faruqui AM, Chagani H. Coronary heart disease risk-factor profile in a lower middles class urban community in Pakistan. East Mediterr Health J. 2005;11:258–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Basharat RA, Yousaf M, Iqbal J, Khan MM. Frequency of known risk factors for stroke in poor patients admitted to Lahore General Hospital in 2000. Pak J Med Sci. 2002;18:280–3. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vohra EA, Ahmed WU, Ali M. Aetiology and prognostic factors of patients admitted for stroke. J Pak Med Assoc. 2000;50:234–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hung HC, Willett W, Merchant A, Rosner BA, Ascherio A, Joshipura KJ. Oral health and peripheral arterial disease. Circulation. 2003;107:1152–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000051456.68470.c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olin JW, Sealove BA. Peripheral artery disease: Current insight into the disease and its diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:678–92. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Siddiqi RO, Paracha MI, Hammad M. Frequency of peripheral arterial disease in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome at a tertiary care centre in Karachi. J Pak Med Assoc. 2010;60:171–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mattila KJ, Nieminen MS, Valtonen VV, Rasi VP, Kesäniemi YA, Syrjälä SL, et al. Association between dental health and acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1989;298:779–81. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6676.779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeStefano F, Anda RF, Kahn HS, Williamson DF, Russell CM. Dental disease and risk of coronary heart disease and mortality. BMJ. 1993;306:688–91. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6879.688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Beck J, Garcia R, Heiss G, Vokonas PS, Offenbacher S. Periodontal disease and cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1123–37. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joshipura KJ, Rimm EB, Douglass CW, Trichopoulos D, Ascherio A, Willett WC. Poor oral health and coronary heart disease. J Dent Res. 1996;75:1631–6. doi: 10.1177/00220345960750090301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grau AJ, Buggle F, Ziegler C, Schwarz W, Meuser J, Tasman AJ, et al. Association between acute cerebrovascular ischemia and chronic and recurrent infection. Stroke. 1997;28:1724–9. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.9.1724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jansson L, Lavstedt S, Frithiof L, Theobald H. Relationship between oral health and mortality in cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;28:762–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.280807.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herzberg MC, Meyer MW. Effects of oral flora on platelets: Possible consequences in cardiovascular disease. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1138–42. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Haraszthy VI, Zambon JJ, Trevisan M, Zeid M, Genco RJ. Identification of periodontal pathogens in atheromatous plaques. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1554–60. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.10.1554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuramitsu HK, Qi M, Kang IC, Chen W. Role for periodontal bacteria in cardiovascular diseases. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:41–7. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beck JD, Offenbacher S. The association between periodontal diseases and cardiovascular diseases: A state-of-the-science review. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:9–15. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Persson RE, Hollender LG, Powell VL, MacEntee M, Wyatt CC, Kiyak HA, et al. Assessment of periodontal conditions and systemic disease in older subjects. II. Focus on cardiovascular diseases. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:803–10. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290903.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Loesche WJ, Schork A, Terpenning MS, Chen YM, Dominguez BL, Grossman N. Assessing the relationship between dental disease and coronary heart disease in elderly U.S. veterans. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:301–11. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1998.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Joshipura KJ, Douglass CW, Willett WC. Possible explanations for the tooth loss and cardiovascular disease relationship. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:175–83. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Desvarieux M, Demmer RT, Rundek T, Boden-Albala B, Jacobs DR, Jr, Papapanou PN, et al. Relationship between periodontal disease, tooth loss, and carotid artery plaque: The Oral Infections and Vascular Disease Epidemiology Study (INVEST) Stroke. 2003;34:2120–5. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000085086.50957.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hung HC, Colditz G, Joshipura KJ. The association between tooth loss and the self-reported intake of selected CVD-related nutrients and foods among US women. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 2005;33:167–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.2005.00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Okoro CA, Balluz LS, Eke PI, Ajani UA, Strine TW, Town M, et al. Tooth loss and heart disease: Findings from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System. Am J Prev Med. 2005;29:50–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ylöstalo PV, Järvelin MR, Laitinen J, Knuuttila ML. Gingivitis, dental caries and tooth loss: Risk factors for cardiovascular diseases or indicators of elevated health risks. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;33:92–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2005.00875.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tuominen R, Reunanen A, Paunio M, Paunio I, Aromaa A. Oral health indicators poorly predict coronary heart disease deaths. J Dent Res. 2003;82:713–8. doi: 10.1177/154405910308200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Beck JD, Eke P, Heiss G, Madianos P, Couper D, Lin D, et al. Periodontal disease and coronary heart disease: A reappraisal of the exposure. Circulation. 2005;112:19–24. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.511998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Briggs JE, McKeown PP, Crawford VL, Woodside JV, Stout RW, Evans A, et al. Angiographically confirmed coronary heart disease and periodontal disease in middle-aged males. J Periodontol. 2006;77:95–102. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.77.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andriankaja OM, Genco RJ, Dorn J, Dmochowski J, Hovey K, Falkner KL, et al. The use of different measurements and definitions of periodontal disease in the study of the association between periodontal disease and risk of myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2006;77:1067–73. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Buhlin K, Gustafsson A, Ahnve S, Janszky I, Tabrizi F, Klinge B. Oral health in women with coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2005;76:544–50. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.4.544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Geerts SO, Legrand V, Charpentier J, Albert A, Rompen EH. Further evidence of the association between periodontal conditions and coronary artery disease. J Periodontol. 2004;75:1274–80. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.9.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Elter JR, Champagne CM, Offenbacher S, Beck JD. Relationship of periodontal disease and tooth loss to prevalence of coronary heart disease. J Periodontol. 2004;75:782–90. doi: 10.1902/jop.2004.75.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.López R, Oyarzún M, Naranjo C, Cumsille F, Ortiz M, Baelum V. Coronary heart disease and periodontitis – A case control study in Chilean adults. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;29:468–73. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2002.290513.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Emingil G, Buduneli E, Aliyev A, Akilli A, Atilla G. Association between periodontal disease and acute myocardial infarction. J Periodontol. 2000;71:1882–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.12.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Joshipura KJ, Hung HC, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Ascherio A. Periodontal disease, tooth loss, and incidence of ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:47–52. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000052974.79428.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wu T, Trevisan M, Genco RJ, Dorn JP, Falkner KL, Sempos CT. Periodontal disease and risk of cerebrovascular disease: The first national health and nutrition examination survey and its follow-up study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2749–55. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.18.2749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Morrison HI, Ellison LF, Taylor GW. Periodontal disease and risk of fatal coronary heart and cerebrovascular diseases. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1999;6:7–11. doi: 10.1177/204748739900600102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Mendez MV, Scott T, LaMorte W, Vokonas P, Menzoian JO, Garcia R. An association between periodontal disease and peripheral vascular disease. Am J Surg. 1998;176:153–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00158-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Taylor GW, Manz MC, Borgnakke WS. Diabetes, periodontal diseases, dental caries, and tooth loss: A review of the literature. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004;25:179–84. 186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pilot T. The periodontal disease problem. A comparison between industrialised and developing countries. Int Dent J. 1998;48:221–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1875-595x.1998.tb00710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sakki TK, Knuuttila ML, Vimpari SS, Hartikainen MS. Association of lifestyle with periodontal health. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1995;23:155–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1995.tb00220.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sakki TK, Knuuttila ML, Vimpari SS, Kivelä SL. Lifestyle, dental caries and number of teeth. Community Dent Oral Epidemiol. 1994;22:298–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0528.1994.tb02055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tomar SL, Asma S. Smoking-attributable periodontitis in the United States: Findings from NHANES III. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. J Periodontol. 2000;71:743–51. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.5.743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ling LJ, Hung SL, Tseng SC, Chen YT, Chi LY, Wu KM, et al. Association between betel quid chewing, periodontal status and periodontal pathogens. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2001;16:364–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-302x.2001.160608.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Shizukuishi S, Hayashi N, Tamagawa H, Hanioka T, Maruyama S, Takeshita T, et al. Lifestyle and periodontal health status of Japanese factory workers. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:303–11. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nicolau B, Netuveli G, Kim JW, Sheiham A, Marcenes W. A life-course approach to assess psychosocial factors and periodontal disease. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:844–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Teng HC, Lee CH, Hung HC, Tsai CC, Chang YY, Yang YH, et al. Lifestyle and psychosocial factors associated with chronic periodontitis in Taiwanese adults. J Periodontol. 2003;74:1169–75. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.8.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Celermajer DS, Chow CK, Marijon E, Anstey NM, Woo KS. Cardiovascular disease in the developing world: Prevalences, patterns, and the potential of early disease detection. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:1207–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.03.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]