Abstract

Aim:

Vitamin D is associated with inflammatory diseases such as periodontal disease and diabetes mellitus (DM). The aim of our study was to find out the level of serum Vitamin D in chronic periodontitis patients (CHP) with and without type 2 DM.

Materials and Methods:

This study consists of 141 subjects, including 48 controls. Case groups consisted of 43 chronic periodontitis patients with type 2 DM (CHPDM) and 50 CHP. pocket depth (PD), clinical attachment loss (CAL), modified gingival index (MGI), plaque index (PI), and calculus index (CI) were taken. Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH] D) level in ηg/ml was estimated by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay with Elecsys and cobase e immunoassay analysers(cobase e 411). Other laboratory investigations including fasting blood sugar (FBS) and serum calcium were measured in all subjects.

Results:

The mean serum 25(OH) D level was 22.32 ± 5.76 ηg/ml, 14.06 ± 4.57 ηg/ml and 16.94 ± 5.58 ηg/ml for control, CHPDM and CHP groups respectively. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.05). The mean value of FBS was significantly high in CHPDM group as compared to CHP group. Periodontal parameters like MGI, PI, PD, and CI showed significant difference between groups (P < 0.05) and higher score was found in CHP group, while CAL and PI showed no statistically significant difference between CHP and CHPDM group (P > 0.05).

Conclusions:

This study observed a low level of serum Vitamin D level in patients with CHP and CHPDM. Low Vitamin D level was observed in case groups may be due to the diseases process rather than low Vitamin D acting as a cause for the disease.

Keywords: 25-hydroxvitamin D, blood glucose, chronic periodontitis, clinical attachment loss, type 2 diabetes mellitus

INTRODUCTION

Chronic periodontitis is a multifactorial disease primarily caused by dental plaque microorganisms with modifying effects from other local and systemic factors. It results from the immunoinflammatory response to chronic infection, which leads to the destruction of periodontal tissues. Host susceptibility plays an important role in the initiation and progression of periodontitis.[1] Recent studies have demonstrated that chronic periodontitis is a potential risk factor for systemic diseases such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus (DM) etc.[2]

Periodontal disease has now been recognized as the sixth complication of diabetes.[3] Mounting evidences suggest that a bidirectional link exists between chronic periodontitis and DM.[4,5] Diabetes influences the periodontium mainly due to the classic microvascular and macrovascular diabetic complications, changes in subgingival microbiota, and alterations in the host immunoinflammatory response to potential periodontal pathogens.[4] Diabetes may result in impairment of neutrophil adherence, chemotaxis, and phagocytosis, which may facilitate bacterial persistence in the periodontal pocket and progressive periodontal destruction. Chronic periodontal inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) β, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and IL-6 leads to insulin resistance in type 2 DM.[6] The control of periodontal infection has an impact on improvement of glycemic control in diabetic patients.[7]

Vitamin D plays an important role in many chronic inflammatory diseases by influencing the expression of inflammation related cytokines.[8] Insulin secretion is reduced in Vitamin D deficiency.[9] Recent evidences showed that persons with diabetes have lower serum concentrations of Vitamin D and its supplementation has improved glycemic control and insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 DM.[10,11] Vitamin D has potential anti-inflammatory effect and its active metabolite, 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D inhibit cytokine production. Vitamin D deficiency results in bone loss and increased inflammation through its immunomodulatory effects.[12,13,14] Recent data suggested that Vitamin D deficiency may play a role both in periodontal disease and DM.[14,15,16]

The inflammatory status as well as Vitamin D insufficiency may create an environment conducive for the progression of chronic diseases such as diabetes and periodontitis. Since a bidirectional relationship exist between periodontitis and diabetes, we hypothesized that the serum Vitamin D level in patients with chronic periodontitis with type 2 DM could be at a lower level than that of patients with chronic periodontitis and healthy subjects. Surprisingly, this association has not been elucidated in the literature so far to the best of our knowledge. Hence, the aim of our study was to find out the level of serum Vitamin D in chronic periodontitis patients with (CHPDM) and without type 2 DM.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional hospital-based clinical study was conducted in the Department of Periodontics, Government Dental College, Calicut, Kerala, India in collaboration with the Department of Biochemistry and the Department of Internal Medicine, Government Medical College Calicut from January 2012 to June 2012. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee Dental College Calicut. One hundred and forty-one subjects were selected and written informed consent was obtained.

The case groups included 93 subjects, of which 43 subjects (male-16, female-27) had CHPDM and 50 subjects (male-18, female-32) had chronic periodontitis without type 2 diabetes mellitus (chronic periodontitis patients [CHP]). The mean age for CHPDM and CHP group was 43.44 and 40.76 years, respectively. The control group comprised of 48 subjects (male-28, female-20) and their mean age was 40.77 years. A decline in serum Vitamin D is reported with aging and it may be attributed to an age-related reduction in the capacity of the skin to produce Vitamin D3.[17] So we selected the age range between 30 and 50 years.

The diagnostic criteria for periodontitis was based on American Academy of Periodontology Criteria 1999, and clinical case definitions proposed by the center for disease control and prevention working group.[18,19] Chronic periodontitis subjects were selected from the outpatient wing of Department of Periodontics, Government Dental College, Calicut. DM was defined based on standard medical care 2010 criteria (serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl after fasting for a minimum of 8 h).[20] Patients with type 2 DM were recruited from the outpatient wing of diabetic clinic, Department of Internal Medicine, Medical College Calicut and they were screened for chronic periodontitis. Control group consists of 48 periodontally healthy subjects or those with mild periodontitis who were selected from patient's bystanders and staff members of Government Dental College, Calicut. History of periodontal therapy within 6 months, antibiotic intake within 3 weeks, postmenopausal woman, subjects with cardiovascular or renal diseases and disease associated with Vitamin D deficiency including bone diseases, malignancies, and multiple sclerosis were excluded from the study.

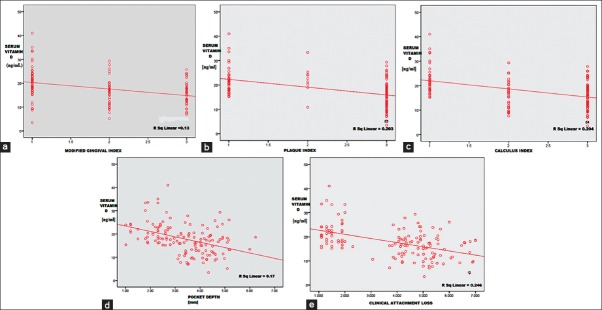

Age, gender, educational status, family history of diabetes, smoking habits, duration of sun exposure, frequency of outdoor activity, history of diabetes, and history of oral hypoglycemic drug intake or insulin administration were assessed by an interview and questionnaire [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic data

Oral hygiene and gingival status were assessed by Silness and Loe plaque index (PI),[21] calculus component of simplified Greene and Vermillion index (CI)[22] and Lobene et al. Modified gingival index (MGI).[23] Pocket depth (PD), gingival recession, and the clinical attachment loss (CAL) were measured for all teeth on six sites (mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-buccal, mesio-lingual, mid-lingual, and disto-lingual) using a William's graduated periodontal probe. Clinical examination was carried out by a single trained examiner (NAV).

All the study blood samples (cases and controls) were collected and assessed in the month of March 2012. Fasting blood sugar (FBS), serum calcium, and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH] D) were assessed. Serum 25(OH) D concentrations is considered to be a suitable biomarker of Vitamin D status that reflects both exposure to sunlight and Vitamin D intake from food supplements. This form of Vitamin D is biologically inactive with levels approximately 1000 fold greater than the circulating 1, 25(OH)2D. It is the major storage form of Vitamin D in the human body and the half-life of circulating 25(OH) D is 2–3 weeks.[24,25] Ideally, the desirable concentration of 25(OH) D for general health is ≥30 ng/ml[26] and 20–30 ng/ml is considered as Vitamin D insuffiency.[27] Level < 20 ng/ml is generally considered as Vitamin D deficiency.[28] Assessment of Vitamin D and other laboratory parameters were done by a qualified and experienced laboratory person who was blinded about periodontal and diabetic status.

Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D assessment by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay

Electrochemiluminescence immunoassay† was used to measure the serum 25(OH) D level. Both internal and external quality control had been done prior to the estimation of Vitamin D level. Total duration of assay was 18 min. Serum was collected and stored at 2–8°C. Measuring range was 10–250 ng/ml (defined by the lower detection limit and the maximum of the master curve).

Statistical analysis

All data were analyzed using software package‡. One-way ANOVA test with post-hoc adjustment (Bonferroni test) was used to compare the mean for periodontal parameters like GI, PI, CI, PD, CAL and (25[OH] D) among the groups. Linear regression analysis was also performed. The relation between clinical parameters of the whole study population (control + CHPDM + CHP) and serum Vitamin D concentration was analyzed using Spearman's rank correlation coefficient test. The α value and confidence interval was set at 0.05 and 95% respectively.

RESULTS

The distributions of percentages of person for education status, smoking habits and outdoor activity, and sun duration were similar in these groups [Table 1]. Body mass index (BMI) (World Health Organization2000 classification)[29] was statistically insignificant among the groups (P > 0.05). The mean FBS was 94.9 ± 15.4 mg/dl, 145.8 ± 52.4 mg/dl and 108 ± 38.7 mg/dl for control, CHPDM, and CHP group respectively and there was significant difference for CHPDM group as compared to control (P = 0.001) and CHP group (P = 0.01). The mean serum calcium level did not achieve statistical significance between CHPDM and CHP groups [Table 2].

Table 2.

Systemic parameters

Oral hygiene habits did not differ among the groups when evaluated for their oral hygiene methods (finger/brush), frequency (once/twice/after every meal), and materials (tooth paste/tooth powder/others), whereas poor oral hygiene predominated in the CHP group.

All periodontal clinical parameters were significantly higher in case groups as compared to healthy controls. Post-hoc and Bonferroni correction for mean PI and CAL scores, showed no statistically significant difference between CHPDM and CHP groups, (P > 0.05), whereas the comparison of means of MGI, CI, and PD between the pairs of groups showed high significance [Table 3].

Table 3.

Comparison of mean periodontal parameters MGI, PI, CI, PD, CAL and mean serum 25(OH) D level between control, CHPDM and CHP group

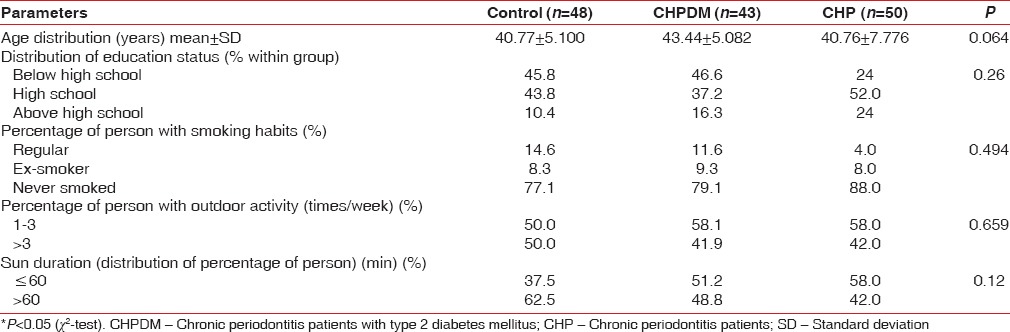

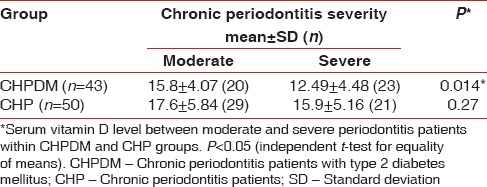

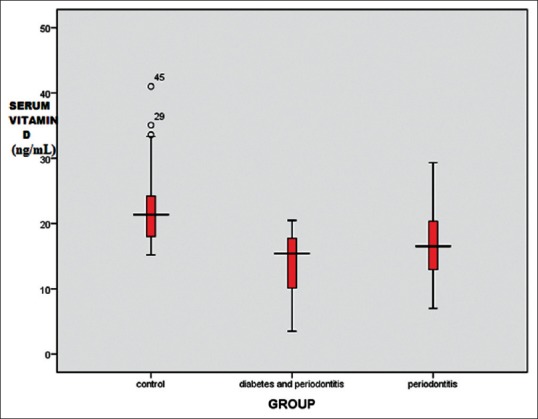

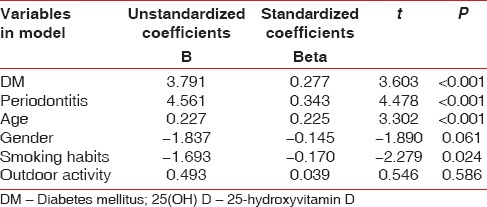

The mean serum 25(OH) D level was found to be 22.3 ± 5.8 ng/ml, 14.1 ± 4.6 ng/ml and 16.9 ± 5.6 ng/ml for control, CHPDM, and CHP group respectively. The difference was statistically significant between CHP and CHPDM groups (P = 0.001), CHPDM and control groups (P = 0.001) and CHP and control groups (P = 0.001) [Table 3]. This showed that a strong association exists between chronic periodontitis with type 2 DM and serum 25(OH) D levels. In CHPDM groups a statistical significant difference was observed in Vitamin D level between moderate periodontitis and severe periodontitis subjects, whereas in CHP groups a significant association was not attained [Table 4]. The distribution of 25(OH) D levels in different groups (CHPDM, CHP and Control) was showed in scatter box plot [Figure 1]. The values PI, MGI, CI, PD, and CAL for the whole study population (control + CHPDM + CHP) were plotted in scatter plot on X axis and serum 25(OH) D values were plotted on Y axis [Figure 2]. It was found that correlation of serum 25(OH) D with MGI, PI, CI, PD, and CAL (control + CHPDM + CHP) was highly significant [Figure 2]. Linear regression analysis indicated that the serum Vitamin D level was influenced by DM and Periodontitis even after adjusting for age, smoking habits and outdoor activity [Table 5].

Table 4.

Serum vitamin D level in cases with moderate and severe chronic periodontitis

Figure 1.

Distribution of mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D level in groups

Figure 2.

(a) Relation between mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25[OH]D) level and clinical parameters (control + chronic periodontitis patients + chronic periodontitis patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus) serum 25(OH)D level versus modified gingival index, (b) serum 25(OH)D level versus plaque index, (c) serum 25(OH)D level versus calculus index, (d) serum 25(OH)D level versus probing depth, (e) serum 25(OH)D level versus clinical attachment loss

Table 5.

Linear regression analysis of serum 25(OH) D level and demographic parameters

DISCUSSION

In our study, CHP group have showed a tendency towards the prediabetes. Chronic systemic inflammation from periodontal disease stimulates inflammatory cytokines leading to insulin resistance and impaired fasting glucose level.[30] Our findings suggested that periodontal disease could have an effect on increased risk for prediabetes. Vitamin D stored in fat tissue causes decreased bioavailability and exposes obese patients to greater risk of developing Vitamin D insufficiency. However, in the present study, BMI of the patients in case groups and control group did not differ significantly.

In this study, even though the probing pocket depth and calculus index was significantly higher in CHP group as compared to CHPDM group, the CAL was not statistically significant between them. This showed that the rate of tissue destruction was more in CHPDM group and diabetes could have an effect on CAL. Factors other than calculus and pathogenic microorganism may influence the actual presentation of chronic periodontitis in diabetes subjects. This is in accordance with the previous studies[5,31] showing that diabetes is a risk factor for periodontitis.

One of the important observations found in this study: The mean serum Vitamin D level was less than the normal range in all groups including control subjects. The insufficient Vitamin D level (22.3 ± 5.8. ng/ml) in control subject may be due to inadequate intake of Vitamin D containing food substances coupled with inadequate sunlight exposure. With modernization the number of hours spent on outdoor activity is decreased. Harinarayan et al. in 2008 reported low Vitamin D status in urban and rural population of Andhra Pradesh state in South India.[32]

Most of the patients in CHPDM group had Vitamin D deficiency. Yu et al. in 2012[33] reported that in his study population, the majority of patients with type 2 diabetes were Vitamin D deficient. Baynes et al.[34] in 1997 found that 25(OH) D concentrations has an inverse correlation to blood glucose concentration. Recently, a meta-analysis for observational studies showed a relatively consistent association between low Vitamin D status, and type 2 DM.[10] From these studies, it is evident that a relationship exists between insufficient serum Vitamin D level and type 2 diabetes. In contrast, Hidayat et al. in 2010[11] suggested that there was no correlation between Vitamin D deficiency and type-2 DM.

In our study, the prevalence of Vitamin D deficiency was high in CHP group as compared to control group. Dietrich et al. in 2005 evaluated the association between serum 25(OH) D and gingival inflammation[35] and found a strong negative association. They concluded that this inverse association may be due to the anti-inflammatory effect of Vitamin D. Boggess et al. in 2011 examined the relationship between maternal Vitamin D status and periodontal disease[36] and reported that pregnant women with moderate to severe periodontal disease had lower median 25(OH) D levels than controls. However, literature also revealed a contrasting report regarding elevated plasma 25(OH) D level in aggressive periodontitis patients.[37] In our study, a negative correlation with Vitamin D level and CAL was observed. Our result is consistent with the study conducted by Dietrich et al. in 2004 who reported an inverse association between serum 25(OH) D and periodontal attachment loss.[14]

Vitamin D deficiency could negatively affect the periodontal health. Its anti-inflammatory effect is mediated through inhibition of cytokine production, stimulation of monocytes and macrophages, and secretion of peptides with potent antibiotic activity. Recently, it has been suggested that its effect on periodontal disease, tooth loss, and gingival inflammation is through its anti-inflammatory effect.[35] The low Vitamin D level observed in CHP group in our study could have an effect on periodontal disease process and progression. The serum Vitamin D level in CHPDM group was at a lower level than that of patients with chronic periodontitis in this study. The Inflammatory status as well as Vitamin D insufficiency may create an environment conducive for the progression of diabetes and periodontitis in this group.

Studies have suggested that patients with chronic inflammatory diseases are deficient in 25(OH) D.[38,39] The Vitamin D nuclear receptors (VDR) located in the nucleus of a variety of cells including immune cells.[39,40] The body controls the activity of VDR through recognition of Vitamin D metabolite 25(OH) D, which antagonize or inactivate the receptor, while 1, 25 dihydroxyvitamin D agonize or activates the receptor. When exposed to infection, the body begins to convert the inactive form of 25-D into the active form, 1, 25-D. As cellular concentrations of 1, 25-D increase, 1, 25-D activates the VDR. However, bacteria create ligands, which like 25-D, inactivates the VDR and in turn, the innate immune response.[40,41] An intraphagocytic bacterial microbiota is proposed to be the primary cause of VDR dysfunction which allows the microbes to proliferate.[40] In response, the body increases the production of 1, 25-D from 25-D, leading to low 25-D and a high 1, 25-D, one of the hallmarks of chronic inflammatory disease. A low level of serum 25-D is seen as the result of down regulation, rather than a causal factor leading to illness.

The present study reveals, it is possible that the low serum Vitamin D level in the case groups (CHP and CHPDM) may be due to the diseases process rather than low Vitamin D acting as a cause.

CONCLUSIONS

This study observed a low level of serum Vitamin D level in patients with chronic periodontitis and chronic periodontitis with type 2 diabetes. Low serum Vitamin D level in CHP and CHPDM group in our study may be due to the disease process rather than low Vitamin D acting as a cause. So the underlying microbial disease process and diabetes could have a synergistic effect in lowering serum 25(OH) D levels in CHPDM patients. In this article, we are trying to put forward a new hypothesis, regarding the possibility of association between periodontal inflammation and low serum Vitamin D level as future directions. Multicenter study with large sample size is needed to study the serum Vitamin D status in chronic periodontitis and diabetes patients.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank Dr. P.K. Sasidharan, Professor, Department of Internal Medicine, Government Medical College, Calicut, Kerala, India for the help rendered during this study.

Footnotes

† Elecsys and cobas e immunoassay analyzers (cobas e 411), Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Sandhofer Strasse, Indianapolis, USA

‡ SPSS 17.0 for Windows

Source of Support: This study was supported by a grant from the State Board of Medical Research (SBMR) (No: E 4/6001/10 MCC dated 6/12/11), Directorate of Medical Education, Government of Kerala; India

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cochran DL. Inflammation and bone loss in periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 2008;79(8 Suppl):1569–76. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.080233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kuo LC, Polson AM, Kang T. Associations between periodontal diseases and systemic diseases: A review of the inter-relationships and interactions with diabetes, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular diseases and osteoporosis. Public Health. 2008;122:417–33. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Löe H. Periodontal disease. The sixth complication of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:329–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santos Tunes R, Foss-Freitas MC, Nogueira-Filho Gda R. Impact of periodontitis on the diabetes-related inflammatory status. J Can Dent Assoc. 2010;76:a35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mealey BL. Periodontal disease and diabetes. A two-way street. J Am Dent Assoc. 2006;137(Suppl):26S–31. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2006.0404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engebretson S, Chertog R, Nichols A, Hey-Hadavi J, Celenti R, Grbic J. Plasma levels of tumour necrosis factor-alpha in patients with chronic periodontitis and type 2 diabetes. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:18–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01017.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vergnes JN, Arrivé E, Gourdy P, Hanaire H, Rigalleau V, Gin H, et al. Periodontal treatment to improve glycaemic control in diabetic patients: Study protocol of the randomized, controlled DIAPERIO trial. Trials. 2009;10:65. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-10-65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Srivastava MD, Ambrus JL. Effect of 1,25(OH) 2 Vitamin D3 analogs on differentiation induction and cytokine modulation in blasts from acute myeloid leukemia patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:2119–26. doi: 10.1080/1042819032000159924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez JA, Ashraf A. Role of Vitamin D in insulin secretion and insulin sensitivity for glucose homeostasis. Int J Endocrinol. 2010;2010:351–85. doi: 10.1155/2010/351385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pittas AG, Lau J, Hu FB, Dawson-Hughes B. The role of Vitamin D and calcium in type 2 diabetes. A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2017–29. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hidayat R, Setiati S, Soewondo P. The association between Vitamin D deficiency and type 2 diabetes mellitus in elderly patients. Acta Med Indones. 2010;42:123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guillot X, Semerano L, Saidenberg-Kermanac’h N, Falgarone G, Boissier MC. Vitamin D and inflammation. Joint Bone Spine. 2010;77:552–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2010.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brazdilova K, Dlesk A, Koller T, Killinger Z, Payer J. Vitamin D deficiency – A possible link between osteoporosis and metabolic syndrome. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2012;113:412–6. doi: 10.4149/bll_2012_093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dietrich T, Joshipura KJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 and periodontal disease in the US population. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;80:108–13. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/80.1.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boucher BJ. Vitamin D insufficiency and diabetes risks. Curr Drug Targets. 2011;12:61–87. doi: 10.2174/138945011793591653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borissova AM, Tankova T, Kirilov G, Dakovska L, Kovacheva R. The effect of Vitamin D3 on insulin secretion and peripheral insulin sensitivity in type 2 diabetic patients. Int J Clin Pract. 2003;57:258–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.MacLaughlin J, Holick MF. Aging decreases the capacity of human skin to produce Vitamin D3. J Clin Invest. 1985;76:1536–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI112134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Williams RC, Offenbacher S. Periodontal medicine: The emergence of a new branch of periodontology. Periodontol 2000. 2000;23:9–12. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0757.2000.2230101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diabetes and periodontal diseases. Committee on Research, Science and Therapy. American Academy of Periodontology. J Periodontol. 2000;71:664–78. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Diabetes Association. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62–9. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Löe H. The gingival index, the plaque index and the retention index systems. J Periodontol. 1967;38(Suppl):610–6. doi: 10.1902/jop.1967.38.6.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Greene JC, Vermillion JR. The simplified oral hygiene index. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;68:7–13. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1964.0034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lobene RR, Weatherford T, Ross NM, Lamm RA, Menaker L. A modified gingival index for use in clinical trials. Clin Prev Dent. 1986;8:3–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart GR, Furniss JL, Laurie D, Durham SK. Measurement of Vitamin D status: Background, clinical use, and methodologies. Clin Lab. 2006;52:335–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maunsell Z, Wright DJ, Rainbow SJ. Routine isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for simultaneous measurement of the 25-hydroxy metabolites of Vitamins D2 and D3. Clin Chem. 2005;51:1683–90. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.052936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vieth R, Bischoff-Ferrari H, Boucher BJ, Dawson-Hughes B, Garland CF, Heaney RP, et al. The urgent need to recommend an intake of Vitamin D that is effective. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:649–50. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rucker D, Allan JA, Fick GH, Hanley DA. Vitamin D insufficiency in a population of healthy western Canadians. CMAJ. 2002;166:1517–24. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Holick MF. The Vitamin D deficiency pandemic and consequences for nonskeletal health: Mechanisms of action. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:361–8. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deurenberg P, Yap M. The assessment of obesity: Methods for measuring body fat and global prevalence of obesity. Baillieres Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;13:1–11. doi: 10.1053/beem.1999.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zadik Y, Bechor R, Galor S, Levin L. Periodontal disease might be associated even with impaired fasting glucose. Br Dent J. 2010;208:E20. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2010.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan WC, Tay FB, Lim LP. Diabetes as a risk factor for periodontal disease: Current status and future considerations. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2006;35:571–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harinarayan CV, Ramalakshmi T, Prasad UV, Sudhakar D. Vitamin D status in Andhra Pradesh: A population based study. Indian J Med Res. 2008;127:211–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yu JR, Lee SA, Lee JG, Seong GM, Ko SJ, Koh G, et al. Serum Vitamin D status and its relationship to metabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chonnam Med J. 2012;48:108–15. doi: 10.4068/cmj.2012.48.2.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Baynes KC, Boucher BJ, Feskens EJ, Kromhout D. Vitamin D, glucose tolerance and insulinaemia in elderly men. Diabetologia. 1997;40:344–7. doi: 10.1007/s001250050685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dietrich T, Nunn M, Dawson-Hughes B, Bischoff-Ferrari HA. Association between serum concentrations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D and gingival inflammation. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:575–80. doi: 10.1093/ajcn.82.3.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boggess KA, Espinola JA, Moss K, Beck J, Offenbacher S, Camargo CA., Jr Vitamin D status and periodontal disease among pregnant women. J Periodontol. 2011;82:195–200. doi: 10.1902/jop.2010.100384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu K, Meng H, Tang X, Xu L, Zhang L, Chen Z, et al. Elevated plasma calcifediol is associated with aggressive periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1114–20. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brenner DR, Arora P, Garcia-Bailo B, Wolever TM, Morrison H, El-Sohemy A, et al. Plasma Vitamin D levels and risk of metabolic syndrome in Canadians. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34:E377. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i6.15899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haussler MR, Whitfield GK, Kaneko I, Haussler CA, Hsieh D, Hsieh JC, et al. Molecular mechanisms of Vitamin D action. Calcif Tissue Int. 2013;92:77–98. doi: 10.1007/s00223-012-9619-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marshall TG. Vitamin D discovery outpaces FDA decision making. Bioessays. 2008;30:173–82. doi: 10.1002/bies.20708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Arnson Y, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. Vitamin D and autoimmunity: New aetiological and therapeutic considerations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1137–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]