Abstract

Background and Objective:

Preterm birth (PTB) is an important issue in public health and is a major cause for infant mortality and morbidity. There is a growing consensus that systemic diseases elsewhere in the body may influence PTB. Recent studies have hypothesized that maternal periodontitis could be a high-risk factor for PTB. The aim of the present study was to investigate the relationship between maternal periodontitis on PTB.

Materials and Methods:

Forty systemically healthy primiparous mothers aged 18–35 years were recruited for the study. Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, they were categorized into PTB group as cases and full term birth group (FTB) as controls. PTB cases (n = 20) defined as spontaneous delivery before/<37 completed weeks of gestation. Controls (FTB) were normal births at or after 37 weeks of gestation. Data on periodontal status, pregnancy outcome variables, and information on other factors that may influence adverse pregnancy outcomes were collected within 2 days of labor. Data were subjected to Student's t-test and Pearson's correlation coefficient statistical analysis.

Results:

Statistically significant difference with respect to the gestational period at the time of delivery and birth weight of the infants in (PTB) group (<0.001) compared to (FTB) group was observed. Overall, there was statistically significant poor periodontal status in the (PTB) group compared to (FTB) group. The statistical results also showed a positive correlation between gestational age and clinical parameters.

Conclusion:

An observable relationship was noticed between periodontitis and gestational age, and a positive correlation was found with respect to PTB and periodontitis. Further studies should be designed to establish periodontal disease as an independent risk factor for PTB/preterm low birth weight.

Keywords: Full term birth, low birth weight, periodontitis, preterm birth, risk factors

INTRODUCTION

Preterm birth (PTB) is defined by WHO as all the births completed before 37 weeks of gestation or fewer than 259 days since the 1st day of a woman's last menstrual period.[1] PTB can be further sub-divided based on gestational age: Extremely preterm (<28 weeks), very preterm (28–<32 weeks), and moderate preterm (32–<37completed weeks of gestation).[2]

It can be further classified into two broad subtypes depending on whether labor is induced or spontaneous: (1) Spontaneous PTB (spontaneous onset of labor or following prelabor premature rupture of membranes [pPROM]) and (2) provider-initiated PTB.[3]

PTB is the leading risk factor for deaths due to neonatal infections and contributes to long-term growth impairment and substantial long-term morbidity such as cognitive, visual, and learning impairments.[4,5]

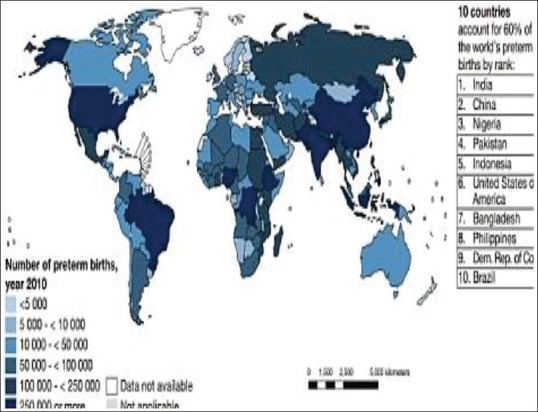

According to WHO data on PTBs India, stands first among the 10 countries which account for 60% PTBs [Figure 1].[6]

Figure 1.

Prevalence rate of preterm birth[6]

Maternal risk factors for PTB include young or advanced age, nutritional status, pre- and antenatal care, smoking and alcohol consumption, and chronic inflammation and infections[6] but the cause of spontaneous preterm labor remains unidentified in up to half of all cases.[7]

Periodontal disease is a Gram-negative anaerobic infection of the mouth that affects up to 90% of the population,[8] and has been demonstrated to be higher in pregnant women.[9] Offenbacher et al. suggested that the maternal periodontal disease was associated with a seven-fold increased risk of delivery of a preterm low birth weight (PLBW)/PTB infant. After controlling for known risk factors, the results of this study were the first to show that periodontitis was a significant risk factor for PTB/PLBW.[10] These findings were confirmed by showing that women with healthy periodontal status had a lower risk of having adverse pregnancy outcomes Dasanayake et al.[11]

Periodontal diseases share many common risk factors with PLBW/PTB such as age, smoking, low socioeconomic level, and systemic health status. It has been suggested that maternal infections leading to alterations in the normal cytokine and hormone-regulated gestation may result in preterm labor, pPROM, and PTB.[12] Hence, the maternal periodontal infection has been proposed to influence preterm delivery through mechanisms involving inflammatory mediators or direct bacterial assault on the amnion.[13] The purpose of the present study was to assess the effect of maternal periodontitis on PTB.

The aim of the study is:

To assess maternal periodontal health among PTB and full term birth (FTB) groups

To correlate gestational age with periodontal clinical parameters.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Source of data

A case-control study was conducted involving patients who reported to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sri Siddhartha Medical College and Hospital, Tumkur.

Method of collection of data

A sample of 40 systemically healthy primiparous mothers aged 18–35 years was recruited for the study. Exclusion criteria included women with caesarean deliveries, second and any subsequent deliveries, paired pregnancies, multiple gestation, high-risk gestation, hypertension, gestational diabetes or any other systemic diseases, chronic infectious diseases.

Based on inclusion and exclusion criteria, the samples were categorized into PTB group as cases and FTB group as controls. PTB cases (n = 20) were defined as spontaneous delivery before/<37 completed weeks of gestation. FTB group FTB controls (n = 20) were defined as women who had normal labor at or after 37 weeks of gestation.

Study design

After Institutional Ethical Committee approval, the purpose and the nature of the study were explained to the subjects and consent for the participation in the study was obtained prior to the commencement of the study.

Demographic data such as age, marital status, educational status, and detailed data about the pregnancy such as present pregnancy history, tobacco use, alcohol use, and genitourinary infections or vaginosis were recorded from the medical records. Data on the birth weight of the child were also noted from the patient's records in the hospital, while the additional information was gathered in an interview with every subject after the periodontal examination.

At 3 days postpartum, as suggested by Offenbacher et al., a single examiner blinded to the identity of the group (case/control) carried out the periodontal examination.

The clinical parameters recorded were Green and Vermillion (1964) oral hygiene index-simplified, Muhlemann and Son sulcus bleeding index (SBI), Jukka and Ainamo (1982) community periodontal index (CPI), probing pocket depth (PPD), and clinical attachment level (CAL).

PPD and CAL were measured to the nearest mm at six sites per tooth, that is, around mesio-buccal, mid-buccal, disto-buccal, mesio-lingual, mid-lingual, and disto-lingual using William's periodontal probe. Cases were considered to have chronic localized periodontitis if probing depth ≥4 mm and CAL ≥3 mm, at the same site in at least four teeth, was noted.[7]

Statistical analysis

A two-sample Student's t-test assuming equal variances using a pooled estimate of the variance was performed to test the hypothesis that the resulting mean parameters between the two study groups were equal. The Pearson's correlation coefficient was used to reveal correlation between the gestational age/period versus Clinical parameters. The statistical analysis was performed using a software program (SPSS Version 10.5, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA), statistical significance being defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

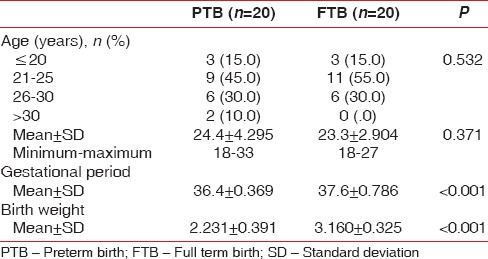

The present study population comprised of a total of 40 subjects between the ages of 18 and 35 years; divided into two groups, PTB and FTB groups, respectively. The mean age for PTB group was 24.4 ± 4.295 years was not statistically different from the FTB group at 23.3 ± 2.904 years. However, statistically significant difference was observed with respect to the gestational period at the time of delivery, with mean values 36.4 ± 0.369 weeks for PTB and 37.6 ± 0.786 weeks for FTB with a P < 0.001. The mean birth weight of the infants was also low in the PTB group 2.231 ± 0.391 kg compared to FTB group 3.160 ± 0.325 kg which was statistically significant (P < 0.001) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Demographic variables

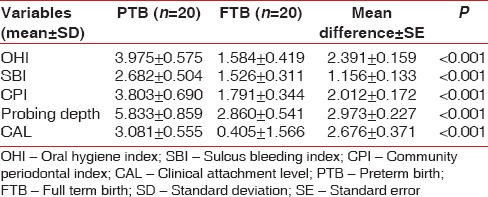

Oral hygiene status was poorer in the PTB group when compared with full term group (FTB), which was statistically significant (P < 0.001). Other clinical parameters like bleeding on probing, pocket depth and CALs between the two study groups were also showed a statistically significant difference (P < 0.001). In general, periodontal status was less healthy in the PTB group compared to full term group (FTB) [Table 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of different variables among the two study groups

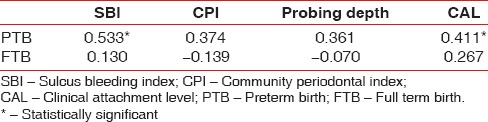

The statistical results also showed that there was a positive correlation between gestational age and other clinical parameters examined [Table 3].

Table 3.

Correlation between gestational period and clinical parameter

DISCUSSION

A total of 40 women admitted to the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Sri Siddhartha Medical College and Hospital, Tumkur, were included in this case-control study.

Subjects with maternal age under 18 and over 35 years were excluded since age outside this range is known as a risk factor for PTB/PLBW. Both the test and the controls were similar with respect to the major risk factors for PLBW such as socioeconomic status, and maternal age. Subjects with only singleton gestation were included because the relationship between multiple gestations and preterm labor is well-established.[14]

In the present study, the mean age of mothers among PTB was 24.4 ± 4.295 and 23.3 ± 2.904 for those in the FTB group, which shows no statistically significant difference between the two groups.

When means of gestational period/weeks at the time of delivery between PTB (36.4 ± 0.369) and FTB groups (37.6 ± 0.786) were compared the results were found to be statistically significant (P < 0.001). Similarly, birth weight of the infants in the PTB group was low (2.231 ± 0.391) when compared to FTB group (3.160 ± 0.325), which suggests that delivery outcomes have been influenced by gestational age. These findings strengthen the statements of the study performed by Love et al.[15]

The SBI (2.682 ± 0.504), oral hygiene index (3.975 ± 0.575), and CPI (3.803 ± 0.690) among PTB group showed statistically significant(<0.001) difference as compared to FTB group. This is in agreement with Zadeh-Modarres et al. indicating that the control group had a good periodontal condition than the case group. The increased circulating levels of progesterone in turn cause dilation of gingival capillaries, permeability, and gingival exudates that may explain the redness and increased bleeding tendency during pregnancy.[16]

In the present study, PTB group showed significant (P < 0.001) association between PPD (5.833 ± 0.859) and low birth weight (2.231 ± 0.391) as compared to FTB group. This is in concurrence with studies conducted byAgueda et al.[17,18]

In the present study, CALs were much higher in FTB group (0.405 ± 1.566) as compared to PTB group (3.081 ± 0.55). This indicated a greater loss of attachment in the PTB group, which was statistically significant. This is in agreement with Offenbacher et al., who found that attachment loss was significantly higher in mothers who had preterm delivery in a study group of 124 predominantly white women.[10] Further in 814 subjects, Jarjoura et al. compared the periodontal status of 83 PB mothers and 120 controls and found that PTB was associated with attachment loss.[19]

The present study showed a positive correlation between gestational age and clinical parameters which were significant in the PTB group compared to FTB with respect to bleeding index and CALs which was also observed in similar study conducted by Lopez et al.[20]

CONCLUSIONS

From the results of this study, it seems likely that periodontitis can influence pregnancy outcomes adversely. The potential relationship between maternal periodontitis and birth outcomes, if proven to be causative, could be significant for public health improvement, given that periodontitis affects a considerable proportion of the general population and is preventable and treatable. Multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trials are required to confirm this link between maternal periodontitis and PTB. As an oral health care provider, the periodontist is in a unique position to take the initiative toward motivating expectant mothers as well as gynecologists[19] regarding the importance of maintaining optimal oral health during pregnancy to avoid any possible adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.WHO: Recommended definitions, terminology and format for statistical tables related to the perinatal period and use of a new certificate for cause of perinatal deaths. Modifications recommended by FIGO as amended October 14, 1976. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1977;56:247–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marlow N. Full term; an artificial concept. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2012;97:F158–9. doi: 10.1136/fetalneonatal-2011-301507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goldenberg RL, Gravett MG, Iams J, Papageorghiou AT, Waller SA, Kramer M, et al. The preterm birth syndrome: Issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206:113–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang HH, Larson J, Blencowe H, Spong CY, Howson CP, Cairns-Smith S, et al. Preventing preterm births: Analysis of trends and potential reductions with interventions in 39 countries with very high human development index. Lancet. 2013;381:223–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61856-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steer P. The epidemiology of preterm labour. Br J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;112:1–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2005.00575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blencowe H, Cousens S, Chou D, Oestergaard M, Say L, Moller AB, et al. Born too soon: The global epidemiology of 15 million preterm births. Reprod Health. 2013;10(Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1742-4755-10-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menon R. Spontaneous preterm birth, a clinical dilemma: Etiologic, pathophysiologic and genetic heterogeneities and racial disparity. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:590–600. doi: 10.1080/00016340802005126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pihlstrom BL, Michalowicz BS, Johnson NW. Periodontal diseases. Lancet. 2005;366:1809–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67728-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contreras A, Herrera JA, Soto JE, Arce RM, Jaramillo A, Botero JE. Periodontitis is associated with preeclampsia in pregnant women. J Periodontol. 2006;77:182–8. doi: 10.1902/jop.2006.050020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Offenbacher S, Katz V, Fertik G, Collins J, Boyd D, Maynor G, et al. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1103–13. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dasanayake AP. Poor periodontal health of the pregnant woman as a risk factor for low birth weight. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:206–12. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Romero R, Mazor M. Infection and preterm labor. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1988;31:553–84. doi: 10.1097/00003081-198809000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.López NJ, Smith PC, Gutierrez J. Higher risk of preterm birth and low birth weight in women with periodontal disease. J Dent Res. 2002;81:58–63. doi: 10.1177/002203450208100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berkowitz GS, Papiernik E. Epidemiology of preterm birth. Epidemiol Rev. 1993;15:414–43. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Love EJ, Kinch RA. Factors influencing the birth weight in normal pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1965;91:342–9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(65)90248-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zadeh-Modarres S, Amooian B, Bayat-Movahed S, Mohamadi M. Periodontal health in mothers of preterm and term infants. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46:157–61. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agueda A, Ramón JM, Manau C, Guerrero A, Echeverría JJ. Periodontal disease as a risk factor for adverse pregnancy outcomes: A prospective cohort study. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:16–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2007.01166.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bassani DG, Olinto MT, Kreiger N. Periodontal disease and perinatal outcomes: A case-control study. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:31–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.01012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Offenbacher S, Lieff S, Boggess KA, Murtha AP, Madianos PN, Champagne CM, et al. Maternal periodontitis and prematurity. Part I: Obstetric outcome of prematurity and growth restriction. Ann Periodontol. 2001;6:164–74. doi: 10.1902/annals.2001.6.1.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarjoura K, Devine PC, Perez-Delboy A, Herrera-Abreu M, D’Alton M, Papapanou PN. Markers of periodontal infection and preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:513–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]