Background: N-Methylpurines are repaired by the base excision repair pathway.

Results: Induction and repair of N-methylpurines in human cells is significantly affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides.

Conclusion: Modulation of N-methylpurine repair by nearest-neighbor nucleotides is primarily achieved by affecting the initial step of the base excision repair process.

Significance: Excision of N-methylpurines by alkyladenine glycosylase is most dramatically affected by sequence context.

Keywords: base excision repair (BER), DNA damage, DNA enzyme, DNA repair, mutagenesis, alkyladenine glycosylase, lesion-adjoining fragment sequencing, N7-methylguanine, N3-methyladenine, nearest-neighbor nucleotides, human fibroblast

Abstract

N-Methylpurines (NMPs), including N7-methylguanine (7MeG) and N3-methyladenine (3MeA), can be induced by environmental methylating agents, chemotherapeutics, and natural cellular methyl donors. In human cells, NMPs are repaired by the multi-step base excision repair pathway initiated by human alkyladenine glycosylase. Repair of NMPs has been shown to be affected by DNA sequence contexts. However, the nature of the sequence contexts has been poorly understood. We developed a sensitive method, LAF-Seq (Lesion-Adjoining Fragment Sequencing), which allows nucleotide-resolution digital mapping of DNA damage and repair in multiple genomic fragments of interest in human cells. We also developed a strategy that allows accurate measurement of the excision kinetics of NMP bases in vitro. We demonstrate that 3MeAs are induced to a much lower level by the SN2 methylating agent dimethyl sulfate and repaired much faster than 7MeGs in human fibroblasts. Induction of 7MeGs by dimethyl sulfate is affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being enhanced at sites neighbored by a G or T on the 3′ side, but impaired at sites neighbored by a G on the 5′ side. Repair of 7MeGs is also affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being slow if the lesions are between purines, especially Gs, and fast if the lesions are between pyrimidines, especially Ts. Excision of 7MeG bases from the DNA backbone by human alkyladenine glycosylase in vitro is similarly affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, suggesting that the effect of nearest-neighbor nucleotides on repair of 7MeGs in the cells is primarily achieved by modulating the initial step of the base excision repair process.

Introduction

Alkylation damage to DNA can be caused by environmental or chemotherapeutic alkylating agents, or by natural cellular methyl donors such as S-adenosylmethionine (1). Simple SN2 methylating agents, such as dimethyl sulfate (DMS),2 produce a variety of damaged bases in DNA, of which N-methylpurines (NMPs), including N7-methylguanine (7MeG) and N3-methyladenine (3MeA), constitute ∼90% of the lesions (2). NMPs are repaired by the multi-step base excision repair (BER) pathway. In human cells, the BER process is initiated by human alkyladenine glycosylase (hAAG), which recognizes and excises the methylated purine bases (1). The apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) sites formed are typically recognized by an AP endonuclease that cleaves the DNA on the 5′ side of the AP sites. The repair process concludes following DNA repair synthesis and ligation. BER of NMPs plays an important role in protecting the genome, and at the same time confounds cancer alkylation therapies, by excising the cytotoxic lesions.

The efficiency of BER can be affected by local DNA sequences (3). The different efficiencies may have implications for genome stability as lesions that persist longer in DNA have a greater chance of leading to mutagenesis. It was demonstrated that the rates of NMP repair in the PGK1 gene of human cells are highly heterogeneous and can be affected by some DNA sequence contexts (4). However, until now, the exact nature of the sequence contexts that affect the repair of NMPs in human cells has been poorly understood. Also, the excision kinetics of NMP bases have been difficult to measure in vitro because the methylated bases are labile to spontaneous depurination and the AP sites formed after excision of the methylated bases are labile to spontaneous strand cleavage. This difficulty has made it impossible to unambiguously address the question as to whether the heterogeneity of NMP repair is caused by the excision of the methylated bases or by a later step of the BER process.

Multiple methods have been developed to map the formation and repair of DNA adducts in living cells (5, 6). Broadly speaking, these methods can be grouped into the genome overall level, gene/DNA fragment level, and nucleotide level. The nucleotide-level methods can be powerful for delineating the modulation of DNA adduct formation and repair by various cellular elements, such as DNA sequence context, chromatin structure, epigenetic modifications, and certain cellular processes (e.g. transcription) (7). However, most of the nucleotide-level methods are only sensitive enough for mapping DNA adduct formation and repair in prokaryotes and lower eukaryotes (i.e. organisms with small genomes) or in multi-copy sequences (e.g. those in mitochondria) of mammalian cells. Indeed, until very recently, ligation-mediated PCR had been the only method that allowed nucleotide-level mapping of DNA lesions in single-copy sequences in mammalian cells (8). However, the ligation-mediated PCR technique is unsuitable for large scale analyses of DNA damage and repair in the cell. Also, the gel bands corresponding to DNA lesions cannot always be well separated, and the lesions cannot be precisely counted. Very recently, a high-throughput method, called XR-Seq (excision repair sequencing), which allows mapping of nucleotide excision repair (NER) of UV photoproducts (cis-syn cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and 6-4 photoproduct) in human cells, was developed (9). This method can provide a snapshot measurement of UV photoproduct-containing oligonucleotides (∼30 nucleotides) that are excised during NER. As it relies on immunoprecipitation of the excised oligonucleotides that transiently exist in the cell, the XR-Seq method is not suitable for accurately measuring the kinetics of NER. Also, the XR-Seq method cannot be used for mapping the formation and repair of DNA lesions that are not NER substrates.

Here, we report the development of a sensitive method, LAF-Seq (Lesion-Adjoining Fragment Sequencing), which allows nucleotide-resolution digital mapping of DNA damage and repair in multiple genomic fragments of interest in human cells. This method is suitable for mapping any type of DNA lesions, provided that they can be converted into DNA single or double strand breaks after isolation of total genomic DNA. We also developed a strategy that allows accurate measurement of the excision kinetics of NMP bases in vitro. We demonstrate that 3MeAs are induced to a much lower level by DMS and repaired much faster than 7MeGs in human fibroblasts. Induction of 7MeGs is affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being enhanced at sites neighbored by a G or T on the 3′ side, but impaired at sites neighbored by a G on the 5′ side. Repair of 7MeGs is also affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being slow if the lesions are between purines, especially Gs, and fast if the lesions are between pyrimidines, especially Ts. Furthermore, we show that the excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG in vitro is similarly affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, suggesting that the effect of nearest-neighbor nucleotides on repair of 7MeGs in human cells is primarily achieved by modulating the initial step of the BER process, namely the excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG.

Experimental Procedures

Cell Culture, DMS Treatment, and DNA Isolation

Telomerase-immortalized human foreskin fibroblast R2F/TERT cells (10) were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 15% newborn calf serum and 10 ng/ml epidermal growth factor. A fraction of the cultured cells was saved as control, and the rest were treated with 0.005% (v/v) DMS for 10 min. This treatment induced ∼1 NMP/10 kb of genomic DNA and caused no obvious cell killing. The cells were washed twice with PBS containing 0.005% (v/v) β-mercaptoethanol, washed twice with PBS, and then replenished with fresh medium and incubated at 37 °C. At 0, 6, 12, and 24 h of the incubation, an aliquot of the cells was harvested. Each aliquot (10 million cells) was resuspended in 2 ml of nuclei isolation buffer (10 mm Tris-Cl, 10 mm NaCl, 3 mm MgCl2, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, pH 7.9) and incubated on ice for 30 min. The nuclei were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in 10 ml of lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, 1 mm EDTA, 400 mm NaCl, 1% SDS, 10 μg/ml proteinase K, pH 8.0), and incubated at 65 °C for 12 h. In addition to releasing DNA, this 12-h incubation at 65 °C caused complete depurination of NMP bases from the DNA backbone. The AP sites formed might be further cleaved by spontaneous β elimination or β and δ eliminations, leaving an unsaturated sugar or a phosphate at the 3′ ends of the cleaved sites. Each of the samples was mixed with 5 ml of 5 m NaCl and incubated on ice overnight. The samples were centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was collected. The genomic DNA was precipitated with isopropanol.

Construction and Sequencing of Libraries of DNA Fragments of Interest

Six μg of genomic DNA of each sample (DMS-treated and untreated) were digested with 12 units of MseI and 3 units of endonuclease IV (New England Biolabs) in 100 μl of NEBuffer 3 (50 mm Tris-HCl, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 100 μg/ml BSA, pH 7.9) overnight. MseI digestion releases the three fragments encompassing exons 11 (281 bp) and 15 (264 bp) of the BRAF gene and the coding exon 1 (228 bp) of the NRAS gene. In addition to incising the DNA on the 5′ side of the AP sites formed after spontaneous depurination of NMPs, endonuclease IV also removes unsaturated sugar or phosphate groups from the 3′ ends of the DNA (11). Each of the samples was added with NaCl to a final concentration of 1 m and a mixture (0.5 pmol each) of biotinylated oligonucleotides (see Table 1). The samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and then incubated at 50 °C for 30 min. Ten μl of streptavidin magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280 streptavidin, Life Technologies) were added to each of the samples and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The beads were washed with STES (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, 0.5% SDS, pH 7.5) at room temperature and with STE (10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, pH 7.5) at 55 °C. To estimate the efficiencies of fishing out the fragments of interest, a small fraction of the beads was resuspended in 25% ammonium hydroxide. The eluted fragments of interest (contained in the supernatants) were vacuum-dried and quantified by real-time PCR (using SYBR Select Master Mix from Life Technologies).

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotides used for construction and sequencing of libraries of DNA fragments of interest

NTS, nontranscribed strand; TS, transcribed strand.

| Name | Sequences (5′ → 3′) | Used for |

|---|---|---|

| Adapter P1 | CCTCTCTATGGGCAGTCGGTGAT | PCR amplification and sequencing of fragment libraries |

| Adapter A | CCATCTCATCCCTGCGTGTCTC | PCR amplification and sequencing of fragment libraries |

| RC-A1 | Phosphate-ATCGTTACCTTAGCTGAGTCGGAGACACGCAGGGATGAGATGG-inverted T | Reverse complement of Adapter A with barcode 1 |

| RC-A2 | Phosphate-ATCGTTCTCCTTACTGAGTCGGAGACACGCAGGGATGAGATGG-inverted T | Reverse complement of Adapter A with barcode 2 |

| RC-A3 | Phosphate-ATCGAATCCTCTTCTGAGTCGGAGACACGCAGGGATGAGATGG-inverted T | Reverse complement of Adapter A with barcode 3 |

| RC-A4 | Phosphate-ATCGATCTTGGTACTGAGTCGGAGACACGCAGGGATGAGATGG-inverted T | Reverse complement of Adapter A with barcode 4 |

| RC-A5 | Phosphate-ATCGTTCCTTCTGCTGAGTCGGAGACACGCAGGGATGAGATGG-inverted T | Reverse complement of Adapter A with barcode 5 |

| BRAF11-1 | AGGGATACAGGAAGAGATCCCCTTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out the NTS of BRAF exon 11; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

| BRAF11-2 | GTGACATTGTGACAAGTCATAATAGGATATGTTTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out the TS of BRAF exon 11; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

| BRAF15-1 | GAGTTTAGGTAAGAGATCTAATTTCTATAATTCTGTAATATAATATTCTTTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out the NTS of BRAF exon 15; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

| BRAF15-2 | GGTAAGAATTGAGGCTATTTTTCCACTGATTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out the TS of BRAF exon 15; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

| NRAS1-1 | CTGTTGGAAACCAGTAATCAGGGTTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out NTS of NRAS coding exon 1; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

| NRAS1-2 | TGTCGGATCATCTTTACCCATATTCTGTATTAATCACCGACTGCCCATAGAGAGG-biotin | Fishing out the TS of NRAS coding exon 1; assisting ligation of adapter P1 |

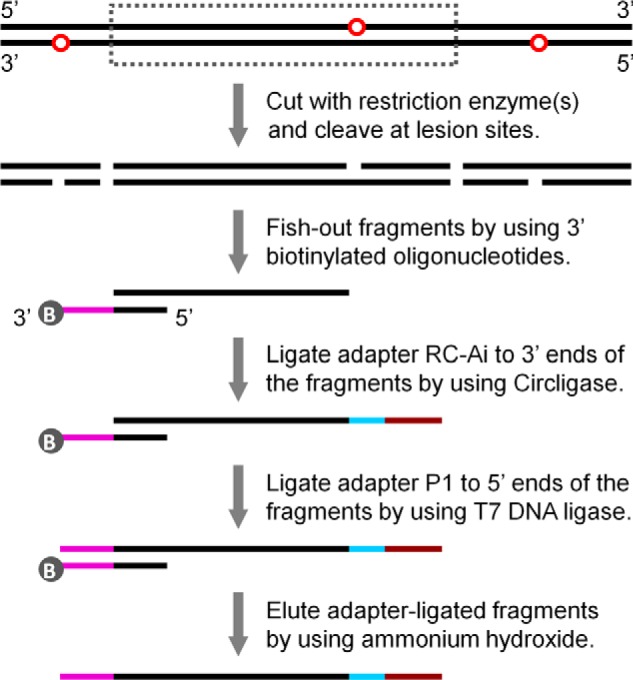

To ligate adapter RC-Ai (see Table 1) to the 3′ ends of the fragments of interest, the beads were resuspended in 10 μl of CircLigase buffer (50 mm MOPS, pH 7.5, 20% PEG 8000, 10 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 0.5 m betaine, 20 μm ATP, 2.5 mm MnCl2, 200 μg/ml BSA, 1 mm DTT), which we have extensively optimized to allow efficient ligation of single-stranded DNA molecules by CircLigase (Epicentre) (12). Two hundred pmol of RC-Ai and 10 units of CircLigase were added to each of the samples and incubated at 55 °C for 1 h. The beads were washed with STES at room temperature, binding and washing buffer with SDS (10 mm Tris, 1 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 0.5% SDS, pH 8.0) at 55 °C, and Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at room temperature. The RC-Ai-ligated fragments were eluted from the beads by using 25% ammonium hydroxide and vacuum-dried.

To ligate adapter P1 to the 5′ ends of the fragments of interest, the DNA samples were dissolved in 50 μl of T7 DNA ligation buffer (66 mm Tris-HCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 1 mm ATP, 1 mm DTT, 7.5% PEG 6000, pH 7.6) containing a mixture (0.25 pmol each) of the biotinylated oligonucleotides and 20 pmol of adapter P1 (see Table 1). The samples were heated at 95 °C for 5 min and at 50 °C for 30 min and then cooled to room temperature. The samples were added with 3 units of T7 DNA ligase (Molecular Cloning Laboratories) and incubated at room temperature for 20 min. Each of the samples was added with 50 μl of 2×binding and washing buffer (20 mm Tris, 2 m NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, pH 8.0) and 10 μl of streptavidin magnetic beads and incubated at room temperature for 30 min. The beads were washed with STES, Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0), and H2O at room temperature. The adapter-ligated fragments were eluted from the beads by using 25% ammonium hydroxide and vacuum-dried. The efficiencies of adapters RC-Ai and P1 ligations were estimated by real-time PCR using a small fraction of the eluted fragments as templates.

The libraries of DNA fragments were amplified by 10–14 cycles of PCR, using Herculase II fusion DNA polymerase (Agilent Technologies) and adapters A and P1 (see Table 1) as primers. The qualities and quantities of the libraries were analyzed by using a Bioanalyzer (Agilent). The barcoded libraries were then pooled, and the sequencing templates were prepared on Ion Sphere particles by using the Ion OneTouch 2 system. The templates were loaded onto Ion 318 chips and sequenced from the RC-Ai-ligated ends (by “reading” the complementary strand in the 5′ to 3′ direction) on an Ion Torrent personal genome machine.

Analysis of Sequencing Data

The sequencing reads were sorted according to their barcodes by using the Torrent Suite software. After being trimmed of barcode sequences, the reads were aligned to the sequences of the fragments of interest by using Bowtie 2 in Galaxy (The Galaxy Project). As the NMPs were induced to a relatively low level (∼1 NMP/10 kb of DNA), the majority (≥97%) of the reads correspond to the complementary strands of the full-length (undamaged) fragments of interest. A small fraction of the reads (≤3%) corresponds to the complementary strands of the fragments of interest adjoining the NMP sites. The total numbers of reads from the DMS-treated samples were normalized to those from the control (not treated with DMS) samples. The 5′ ends of the reads that align to the internal sites of the fragments of interest would correspond to the NMPs induced or remaining (at different times of repair) at sites on the complementary strands. The reads whose 5′ ends align to the same sites of the fragments of interest were counted. To remove background signals, the read counts aligned to different sites of the fragments of interest from the DMS-treated samples were deducted by the corresponding counts from the control samples. Only those sites with >10 counts of lesions at 0 h of repair were analyzed for NMP repair.

Excision of 7MeG Bases by hAAG in Vitro

Eighty pmol of each of the substrates (see Fig. 9A) was treated with 0.6% (v/v) DMS in a total volume of 100 μl of Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 8.0) at room temperature for 15 min, which induced ∼0.05 7MeG per fluorescein (FAM)-labeled fragment of the substrates. The DMS-treated substrates were purified and dissolved in 80 μl of ThermoPol buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, 10 mm (NH4)2SO4, 10 mm KCl, 2 mm MgSO4, 100 μg/ml BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100, pH 8.8, at 25 °C). Two pmol of purified hAAG (New England Biolabs) was added to each of the samples and incubated at 37 °C. At different times of the incubation, an aliquot of 10 μl (10 pmol of DNA) was taken, and the DNA was purified. Each of the aliquots was then treated with 100 mm O-(tetrahydro-2H-pyr an-2-yl)hydroxylamine (OTX) (Sigma) in a total volume of 25 μl of STE at 37° C for 1 h. Each of the aliquots (10 pmol of DNA) was then treated with 1.2 pmol of hAAG and an excess amount of AP endonuclease 1 (APE1) (New England Biolabs) at 37 °C for 3 h to excise all the remaining NMPs and completely cleave the DNA at the resulting unprotected AP sites.

FIGURE 9.

Experimental design for measuring the excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG in vitro. A, DNA substrates. 7MeGs formed at the underlined Gs neighbored by G (gGg), A (aGa), C (cGc), or T (tGt) in the FAM-labeled strand were intended for analysis. B, schematic outlining the process of the analysis. Open circles denote 7MeGs formed in the FAM-labeled strand. Open triangles indicate OTX-reacted AP sites formed after excision of the 7MeG bases.

To analyze the samples on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems), 0.1 pmol of each of the samples was loaded into an 80-cm capillary column filled with POP-6 polymer. The FSA binary files generated were converted to text files by using BatchExtract (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/pub/forensics/BATCHEXTRACT). The fluorescent signals were then analyzed by using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Development of LAF-Seq

We reasoned that DNA lesions at specific sites of the genome could be digitally mapped if single-stranded DNA fragments adjoining the lesions could be fished out, sequenced, and counted. Exons 11 and 15 of the BRAF gene and the coding exon 1 of the NRAS gene contain frequent mutations in cutaneous melanoma and other human cancers (13). We chose to develop the method by mapping NMP induction and repair in both strands of genomic DNA fragments encompassing these exons.

Human fibroblasts were treated with DMS to induce a low level of NMPs in the genomic DNA (∼1 NMP/10 kb of DNA). Following different times of repair incubation, aliquots were taken and total genomic DNA was isolated. DNA samples from the DMS-treated cells at different times of repair and from the untreated cells was separately cut with a restriction enzyme to release the fragments of interest and cleaved at the NMP sites (Fig. 1). The fragments of interest were simultaneously fished out from each of the samples by using excess copies of a mixture of biotinylated oligonucleotides that are complementary to the 5′ end region of the fragments of interest (Table 1). The efficiency of fishing out the genomic fragments of interest from the total genomic DNA was around 70% (Fig. 2). To allow sequencing by the Ion Torrent personal genome machine, adapter RC-Ai (reverse complement of adapter Ai, “i” stands for a barcode number) and adapter P1 were ligated to the 3′ and 5′ ends of the fragments of interest, respectively. Each of the samples was ligated with specifically barcoded RC-Ai. Under our optimized conditions, over 90% of the fished-out fragments of interest were ligated to adapters RC-Ai and P1 (Fig. 3). The adapter-ligated fragments with different barcodes were pooled and sequenced simultaneously from the adapter RC-Ai ligated ends (by reading the complementary strand in the 5′ to 3′ direction) on Ion Torrent 318 chips, which typically generate 5–6 million high quality sequencing reads each run (Fig. 4). Most of the sequencing reads can be aligned to the reference sequences of the fragments of interest (94 and 99% for the two sequencing runs, respectively). The low read counts aligned to specific sites of the fragments of interest from the control (untreated with DMS) samples reflect background signals, which were deducted from the corresponding sites from the DMS-treated samples. NMPs induced (at 0 h of repair) or remaining (at different times of repair) at specific sites of the fragments of interest were then counted by tallying the sequencing reads whose ends align to the respective damaged sites.

FIGURE 1.

Construction of a sequencing library of DNA fragments that are full-length (undamaged) or adjoining the lesion sites. Red circles represent lesions induced initially or remaining after different times of repair. Dashed line box indicates a fragment that can be released by restriction digestion. Gray circles marked with B denote the biotin group. The 3′ (pink) and 5′ (black) regions of the biotinylated oligonucleotides are complementary to adapter P1 and the 5′ end region of fragments of interest, respectively. Adapter RC-Ai (“i” stands for a barcode number) is an oligonucleotide whose 5′ end is phosphorylated and 3′ end blocked by an inverted dT. The 5′ region (cyan) of RC-Ai is a barcode sequence (i). The 3′ region (brown) of RC-Ai is complementary to adapter A. See Table 1 for sequences of the oligonucleotides.

FIGURE 2.

Estimation of efficiencies of fishing out the fragment of interest. A and B, schematic representation of the experiment for real-time PCR using restricted genomic DNA (A) versus fished-out template (B). Fa and Fb are PCR primers. oligo, oligonucleotides. C, examples of real-time PCR results. Amplifications of the fragment encompassing exon 15 of the BRAF gene are shown. The templates used for each of the repeats were 100 ng of the restricted genomic DNA or the fragment fished out from the equivalent of 100 ng of the restricted genomic DNA. D, gel showing products of the real-time PCR reactions (after 40 cycles) shown in C. M, DNA size maker.

FIGURE 3.

Estimation of ligation efficiencies of adapters RC-Ai and P1 to the fished-out fragments of interest. A, schematic showing real-time PCR of the ligated fragment with the indicated primer pairs. B, examples of real-time PCR results. Shown here are amplifications of the fragment encompassing exon 15 of the BRAF gene ligated to adapters RC-A1 and P1. The templates used for each of the repeats were fragments fished out from the equivalent of 100 ng of the restricted genomic DNA. C, gel showing products of the real-time PCR reactions (after 40 cycles) shown in B. M, DNA size maker.

FIGURE 4.

Summary of sequencing runs and alignments. A and B, statistics of one sequencing run and alignment of the sequencing reads to DNA fragments of interest. C and D, statistics of another sequencing run and alignment of the sequencing reads to DNA fragments of interest. ISP, Ion Sphere Particle (on which the sequencing templates were prepared).

Induction and Repair of NMPs in Human Cells

Lesion counts at different sites of the fragments analyzed are shown in Figs. 5–7. As can be seen, most (∼90%) of the NMPs induced by DMS were 7MeGs, and a small fraction (∼10%) was 3MeAs. For five out of six strands of the three fragments analyzed, NMPs that can be detected are located in sites that are ≥2–9 nucleotides from the regions that are complementary to the biotinylated oligonucleotides used to fish out the fragments (Fig. 1). This is consistent with the fact that the CircLigase we used to ligate adapter RC-Ai to the 3′ end of the fragments of interest can only ligate single-stranded but not double-stranded DNA (12). However, we detected 7MeGs at a site of the region that is complementary to BRAF11-2 (Table 1). This site is complementary to the 5th nucleotide (from the 5′ end) of BRAF11-2 and is located in the transcribed strand of the fragment encompassing exon 11 of the BRAF gene (Fig. 5, see the “g” site that is the second nucleotide from the 5′ end of the transcribed strand). Presumably, the fragment adjoining 7MeG at this site was ligated to adapter RC-Ai due to “breathing” of double-stranded DNA. The “breathing” at 55 °C (the temperature we used for ligation of RC-Ai) might be frequent but did not cause detachment of the fragment from the biotinylated BRAF11-2.

FIGURE 5.

Lesion counts in the genomic DNA fragment encompassing exon 11 of the BRAF gene in human fibroblasts. Bottom and top panels show the transcribed and nontranscribed strands, respectively. Bars in the panels denote lesion counts per 105 DNA molecules at the indicated sites at 0 (blue), 6 (red), 12 (cyan), and 24 (violet) h of repair incubation. Nucleotide positions are numbered from “A” in the start codon (ATG) of the DNA sequences present in the mature mRNA. Arrows indicate sites that are frequently mutated (≥10 recurrence in human cancers; based on the COSMIC). Nucleotides underneath the arrows indicate common nucleotide changes at the mutation sites.

FIGURE 6.

Lesion counts in the genomic DNA fragment encompassing exon 15 of the BRAF gene in human fibroblasts. Bottom and top panels show the transcribed and nontranscribed strands, respectively. Bars in the panels denote lesion counts per 105 DNA molecules at the indicated sites at 0 (blue), 6 (red), 12 (cyan), and 24 (violet) h of repair incubation. Nucleotide positions are numbered from “A” in the start codon (ATG) of the DNA sequences present in the mature mRNA. Arrows indicate sites that are frequently mutated (≥10 recurrence in human cancers; based on the COSMIC). Nucleotides underneath the arrows indicate common nucleotide changes at the mutation sites.

FIGURE 7.

Lesion counts in the genomic DNA fragment encompassing coding exon 1 of the NRAS gene in human fibroblasts. Bottom and top panels show the transcribed and nontranscribed strands, respectively. Bars in the panels denote lesion counts per 105 DNA molecules at the indicated sites at 0 (blue), 6 (red), 12 (cyan), and 24 (violet) h of repair incubation. Nucleotide positions are numbered from “A” in the start codon (ATG) of the DNA sequences present in the mature mRNA. Arrows indicate sites that are frequently mutated (≥10 recurrence in human cancers; based on the COSMIC). Nucleotides underneath the arrows indicate common nucleotide changes at the mutation sites.

In addition to inducing the predominant NMPs, DMS induces a small fraction (0.3%) of O6-methylguanine, which is stable (2) and cannot be converted to a strand break and detected by the LAF-Seq method. DMS also induces ∼10 other minor adducts (e.g. N1-methyladenine, N7-methyladenine, N3-methylguanine, and O2-methylcytosine), some of which are heat-labile (2) and may be detected by the LAF-Seq method. However, as together they comprise <5% of the total lesions induced by DMS (2), the levels of the minor adducts were expected to be marginal when compared with NMPs we detected here.

The induction levels and repair rates of NMPs were highly heterogeneous. However, the heterogeneity did not seem to correlate with the hotspots of carcinogenic mutations in these fragments documented in the Catalogue of Somatic Mutations in Cancer (COSMIC) (Figs. 5–7), suggesting that NMPs may not particularly cause more mutations at these hotspots. According to data deposited in the UCSC Genome Browser, some weakly positioned nucleosomes are present in the fragments we analyzed. The repair rates did not seem to significantly correlate with these weakly positioned nucleosomes (not shown).

7MeGs were induced to higher levels at sites of aGg, aGt, tGg, and tGt, but to lower levels at sites of gGa, gGc, gGg, and gGt (Gs are the sites of 7MeG formation, and lowercase letters denote nearest-neighbor nucleotides) (Fig. 8A, compare 0-h lesion levels at the different sites). It appears that 7MeG induction was enhanced at sites neighbored by a G or T on the 3′ side, but impaired at sites neighbored by a G on the 5′ side. In G tracts (with ≥2 continuous Gs), 7MeG induction tended to be high at the 5′-most G site but low at the other G sites (Figs. 5–7 and 8A).

FIGURE 8.

NMPs remaining at different times of repair. A, 7MeG counts (means + standard deviation) at sites with different nearest-neighbor nucleotides. Gs indicate 7MeG sites, and lowercase letters denote nearest-neighbor nucleotides. The levels of 7MeG at the cGt site are not shown because <10 7MeGs were induced at the sole cGt site in all the three fragments analyzed. No error bars are shown for the cGc site as >10 7MeGs were induced at only one of three cGc sites in all the three fragments analyzed. The levels of 7MeG induced (0 h of repair) at aGg, aGt, tGg, and tGt sites were significantly higher than those at gGa, gGc, gGg, and gGt sites (p < 0.01, Student's t test). B, the percentage of 7MeGs remaining (mean) at sites with different nearest-neighbor nucleotides. The values at sites of fast repair (tGt and tGc) are significantly different from those at sites of slow repair (aGg, gGg, gGa, aGa) at all the time points of repair (p < 0.05, Student's t test). C, 7MeG counts (mean + standard deviation) at sites neighbored by purines on both sides (rGr), by a purine on one side and a pyrimidine on the other (rGy/yGr), and by pyrimidines on both sides (yGy). D, the percentage of 7MeGs remaining (mean) at sites of rGr, rGy/yGr, and yGy. The value at each of the repair time points is significantly different from one context of the neighbor nucleotides to any of the other two (p < 0.01, Student's t test). E, the percentage of 3MeAs and 7MeGs remaining (mean). The percentage of 3MeAs remaining is significantly different from the percentage of 7MeGs remaining at each of the repair time-points (p < 0.01, Student's t test).

The 7MeG counts at some sites, especially those between purines (As or Gs), were higher after certain times of repair than those at 0 h of repair (Figs. 5–7 and 8, A and B), presumably reflecting certain levels of continued induction of the lesions after DMS was removed from the medium and slow repair at these sites. Indeed, repair of 7MeGs appeared to be significantly affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being slow for the lesions between purines, especially Gs, and fast for the lesions between pyrimidines, especially Ts (Fig. 8, A–D). 7MeGs neighbored by a pyrimidine on one side and a purine on the other were repaired at intermediate rates. In contrast, the second- or third-nearest nucleotides did not seem to significantly affect the rate of 7MeG repair (data not shown). The average repair rate of all 3MeAs in these fragments was much faster than that of 7MeGs (Fig. 8E). Indeed, the average half-life of 3MeAs was ∼7 h, whereas that of 7MeGs was ∼22 h.

Excision of 7MeG Bases by hAAG in Vitro

The rates of 7MeG repair we measured in the cells reflect the speeds of the whole BER process. We wondered whether the heterogeneity of 7MeG repair in the cells was caused by the initial step (i.e. the excision of 7MeG bases) of the BER process. The excision kinetics of 7MeG bases by purified hAAG had been difficult to measure because 7MeG bases are labile to spontaneous depurination and the AP sites formed after excision of the 7MeG bases are labile to spontaneous strand cleavage, especially at an elevated temperature. We therefore developed a new strategy for the measurement (Fig. 9). All the DNA substrates we used were identical except for the 2 nucleotides neighboring the G in the middle of the 5′-FAM-labeled strand (Fig. 9A). The substrates were treated with DMS to induce ∼0.05 7MeG per FAM-labeled fragment of the substrates. The inductions of 7MeGs by DMS are largely random events, although they may be modulated by certain DNA sequences. At an induction level of 0.05 7MeG/fragment, the chance that the fragment molecules may contain >1 lesion is very low (0.12%). The DMS-treated substrates were incubated with a limited amount of hAAG. At different times of the incubation, aliquots were taken and the AP sites formed after excision of the damaged bases were stabilized by treatment with OTX. AP sites stabilized by OTX are resistant to cleavage by heat and the human AP endonuclease APE1 (14, 15). The DNA was then completely cleaved at the remaining 7MeG sites by extended incubation with excess amounts of hAAG and APE1. The DNA fragments were analyzed by capillary electrophoresis on a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer, which is commonly used for routine DNA sequencing. We found that, when compared with DNA sequencing gels, the capillary electrophoresis has a much higher resolution in separating bands of DNA fragments and allows much more sensitive detection (the limit is ∼0.1 fmol or 6 × 107 of FAM-labeled molecules for detecting a band) and accurate quantification of the bands.

As can be seen in Fig. 10, 7MeG bases between purines, especially Gs, were excised much more slowly than those between pyrimidines, especially Ts. The trend of nearest-neighbor nucleotide effect on excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG in vitro resembles that on 7MeG repair in human cells. The overall excision rates of 7MeG bases in vitro under our conditions were much faster than those of 7MeG repair in the cells, presumably because 1) a relatively low level of hAAG existed in the cell and/or 2) the rates of 7MeG repair we measured in the cell reflected the whole process of BER, rather than just the excision of the damaged bases. The scattered distribution of 7MeGs and the chromatin structure might also contribute to the slow repair of 7MeGs in the cell. These results support the idea that the effect of nearest-neighbor nucleotides on repair of 7MeGs in human cells is primarily achieved by modulating the initial step of the repair process, namely the excision of the damaged bases by hAAG.

FIGURE 10.

Measurement of the excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG in vitro. A–D, overlays of FAM signals in capillary columns loaded with samples that had been treated with a limited amount of hAAG for the indicated lengths (in min) of time. FAM-labeled DNA substrates (Fig. 9A) containing 7MeGs neighbored by G (gGg), A (aGa), C (cGc), or T (tGt) were treated with a limited amount of hAAG for different lengths of time. The resulting AP sites were stabilized by treatment with OTX. The DNA substrates were then cleaved at all the remaining 7MeG sites and subjected to capillary electrophoresis. The nucleotide positions of the peaks are indicated at the bottom of each of the panels. The underlined Gs in red indicate the sites of 7MeG bases that were intended for analysis. E, the percentage of 7MeG bases remaining. The values are averages of three measurements. The values are significantly different from one context of the neighbor nucleotides to any of the other three (p < 0.01, Student's t test).

Discussion

We developed the LAF-Seq method for high-resolution digital mapping of NMP induction and repair in human cells. When compared with currently available gel-based methods, the LAF-Seq method has several advantages. First, the LAF-Seq method is highly sensitive. We mapped lesions that were induced to a level of ∼1 per 10 kb of DNA. Second, the LAF-Seq method is much less labor-intensive, especially for simultaneously mapping DNA damage and repair in multiple sequences of the genome. Although we have tested fishing out and mapping three fragments of interest, there is no reason why more fragments cannot be fished out and analyzed simultaneously. Third, the LAF-Seq method can be used to achieve true nucleotide resolution mapping and digital quantification of DNA lesions. This is in contrast to gel-based methods where bands cannot always be well separated and lesions cannot be precisely counted. Furthermore, the LAF-Seq method should be able to be used for mapping other types of DNA lesions if they can be converted to single or double strand breaks after the genomic DNA is isolated from the cells. Many enzymes are available that can specifically incise DNA at the sites of different lesions. For example, the bifunctional DNA glycosylases formamidopyrimidine DNA glycosylase (FPG) and endonuclease VIII can excise oxidized purine and pyrimidine bases, respectively, and incise the DNA 3′ (through β-elimination) and 5′ (through δ-elimination) to the resulting AP sites, leaving a phosphate group at the 3′ end (16). On the other hand, T4 endonuclease V can incise DNA at cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers, resulting in an unsaturated sugar at the 3′ end (17). To make the 3′ ends ligatable to adaptor RC-Ai, the lesion-incised DNA samples can be treated with endonuclease IV, which seems to be able to remove essentially any non-OH groups at the 3′ ends of DNA formed after incision by different damage-specific enzymes (11). However, certain fragments cannot be fished out from the genomic DNA due to the lack of appropriate restriction sites. Therefore, although it can be used for simultaneous mapping of DNA lesions in multiple restriction fragments, the LAF-Seq method is not suitable for genome-wide mapping of DNA lesions.

The N7 position of Gs faces the major groove of DNA and has a high electrostatic potential, which is the major reason why this position is preferentially methylated by such SN2 methylating agents as DMS (2). It was reported that DMS preferentially methylates the 5′ end G in G runs, presumably due to the highest electrostatic potential at the N7 position of the 5′ end G (18). Our result that 7MeG induction is high at the 5′-most G site but low at the other G sites in a G tract agrees well with the previous study. However, unlike the previous study, which showed that an A present in a G run did not affect the damage pattern, we found that an A present in a G run will disrupt the pattern (i.e. N7-methylation of a G 3′ to the A is not impaired by the G(s) 5′ to the A (Figs. 5–7)). We also found that 7MeG induction was enhanced at sites neighbored by a G or T on the 3′ side. The effects of the 3′ neighbor nucleotides on the 7MeG induction may also be due to modulation of the electrostatic potential. It can be predicted that the electrostatic potential at the N7 position of a G can be reinforced by a 3′-G or -T (19, 20).

Each human cell contains thousands of copies of mitochondrial DNA (21). Using a gel-based method that is only sensitive enough for mapping DNA damage in multi-copy sequences in the human genome, we previously found that repair of 7MeGs in human mitochondria is affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being slow for the lesions between purines and fast for the lesions between pyrimidines (22). It was found recently that hAAG is present in human mitochondria and associates with mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein (23). Taken together with our results, it appears that excision of 7MeG bases by hAAG may be similarly affected by neighbor nucleotides in the nucleus and mitochondria, although the local environments can be quite different.

The crystal structure of hAAG (1BNK) showed that a damaged base is flipped from the DNA base stack into a sequestered active site pocket where the glycosidic bond between the damaged base and the deoxyribose is hydrolyzed (24). The stability of base stacking between two adjacent bases follows the order: purine-purine ≫ purine-pyrimidine > pyrimidine-purine > pyrimidine-pyrimidine, with a 2-kcal/mol free energy spread between the most stable purine-purine and the least stable pyrimidine-pyrimidine base stacks (25). Under the physiological pH, a 7MeG base can be positively charged (protonated) (26). The positive charge may increase base stacking through the cation-π interaction (27). To date, the free energies of base stacking between 7MeG and normal purines or pyrimidines have not been documented. It is likely that a 7MeG base has more stable stacking with purines than with pyrimidines. The different base-stacking stabilities may affect the flipping of the 7MeG base by hAAG, thereby modulating the excision of the damaged bases. Indeed, it has been shown that hAAG is exquisitely sensitive to the structural context of a deoxyinosine lesion (an uncharged substrate of hAAG), and an inverse correlation between duplex stability and catalytic efficiency was observed (28).

The overall repair of NMPs in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae (29, 30) appears to be much faster than that in the human cells we reported here. Interestingly, however, repair of 7MeGs in the yeast has also been found to be affected by nearest-neighbor nucleotides, being slow if they are between purines and fast if they are between pyrimidines (29, 30). Repair of NMPs in the yeast is solely initiated by Mag1, the homolog of hAAG (29). The crystal structure of the yeast Mag1 complexed with its substrate has not been reported. The nearest-neighbor nucleotides appear to affect hAAG and Mag1 similarly in excising the damaged bases.

Similar to hAAG, most DNA glycosylases have converged on a single mechanistic solution for damaged base recognition and excision: flip of the damaged base from the DNA base stack into a sequestered active site pocket (31). The activities of some but not all glycosylases have been shown to be modulated to some extent by DNA sequence context (for a review, see Ref. 3). Interestingly, altering either the global DNA sequence or the 5′-flanking base pair failed to influence the excision of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine (8-oxoG) by human 8-oxoguanine glycosylase (OGG1) in vitro (32). However, an 8-oxoG located in the CAGGGC[8-oxoG]GACTG motif is poorly excised by OGG1 (33). Therefore, the excision of 8-oxoG by OGG1 does not seem to be significantly affected by base stacking with nearest-neighbor nucleotides. It seems that the activities of alkyladenine glycosylases (e.g. hAAG and Mag1) are more dramatically modulated by nearest-neighbor nucleotides than those of any other DNA glycosylases analyzed so far.

Author Contributions

S. L. and M. L. conceived and designed the studies. M. L., S. L., and T. K. conducted the experiments. M. L. and S. L. analyzed the data and wrote the paper. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Scott Herke of the Louisiana State University (LSU) Genomics Facility for excellent help with the next generation sequencing and capillary electrophoresis. We also thank our laboratory members for helpful discussion.

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R15CA164862 (to S. L.) and National Science Foundation Grant MCB-1244019 (to S. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- DMS

- dimethyl sulfate

- NMP

- N-methylpurine

- 3MeA

- N3-methyladenine

- 7MeG

- N7-methylguanine

- hAAG

- human alkyladenine glycosylase

- BER

- base excision repair

- NER

- nucleotide excision repair

- AP site

- apurinic/apyrimidinic site

- LAF-Seq

- lesion-adjoining fragment sequencing

- XR-Seq

- excision repair sequencing

- RC-A

- reverse complement of adapter A

- OTX

- O-(tetrahydro-2H-pyran-2-yl)hydroxylamine

- APE1

- AP endonuclease 1

- OGG1

- 8-oxoguanine glycosylase

- FAM

- fluorescein

- 8-oxoG

- 7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine.

References

- 1. Fu D., Calvo J. A., Samson L. D. (2012) Balancing repair and tolerance of DNA damage caused by alkylating agents. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 104–120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wyatt M. D., Pittman D. L. (2006) Methylating agents and DNA repair responses: methylated bases and sources of strand breaks. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 19, 1580–1594 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Donigan K. A., Sweasy J. B. (2009) Sequence context-specific mutagenesis and base excision repair. Mol. Carcinog. 48, 362–368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ye N., Holmquist G. P., O'Connor T. R. (1998) Heterogeneous repair of N-methylpurines at the nucleotide level in normal human cells. J. Mol. Biol. 284, 269–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Henderson D. S. (ed) (2005) DNA Repair Protocols: Mammalian Systems, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 6. Vaughan P. (ed) (2000) DNA Repair Protocols: Prokaryotic Systems, Humana Press, Totowa, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 7. Li S., Waters R., Smerdon M. J. (2000) Low- and high-resolution mapping of DNA damage at specific sites. Methods 22, 170–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Besaratinia A., Pfeifer G. P. (2012) Measuring the formation and repair of UV damage at the DNA sequence level by ligation-mediated PCR. Methods Mol. Biol. 920, 189–202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hu J., Adar S., Selby C. P., Lieb J. D., Sancar A. (2015) Genome-wide analysis of human global and transcription-coupled excision repair of UV damage at single-nucleotide resolution. Gene Dev. 29, 948–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Rheinwald J. G., Hahn W. C., Ramsey M. R., Wu J. Y., Guo Z., Tsao H., De Luca M., Catricalà C., O'Toole K. M. (2002) A two-stage, p16INK4A- and p53-dependent keratinocyte senescence mechanism that limits replicative potential independent of telomere status. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5157–5172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Demple B., Johnson A., Fung D. (1986) Exonuclease III and endonuclease IV remove 3′ blocks from DNA synthesis primers in H2O2-damaged Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 7731–7735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Blondal T., Thorisdottir A., Unnsteinsdottir U., Hjorleifsdottir S., Aevarsson A., Ernstsson S., Fridjonsson O. H., Skirnisdottir S., Wheat J. O., Hermannsdottir A. G., Sigurdsson S. T., Hreggvidsson G. O., Smith A. V., Kristjansson J. K. (2005) Isolation and characterization of a thermostable RNA ligase 1 from a Thermus scotoductus bacteriophage TS2126 with good single-stranded DNA ligation properties. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, 135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hocker T., Tsao H. (2007) Ultraviolet radiation and melanoma: a systematic review and analysis of reported sequence variants. Hum. Mutat. 28, 578–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Luke A. M., Nakamura J. (2012) O-Hydroxylamine-coupled alkaline gel electrophoresis assay for the detection and measurement of DNA single-strand breaks. Methods Mol. Biol. 920, 307–313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rosa S., Fortini P., Karran P., Bignami M., Dogliotti E. (1991) Processing in vitro of an abasic site reacted with methoxyamine: a new assay for the detection of abasic sites formed in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 19, 5569–5574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Prakash A., Doublié S., Wallace S. S. (2012) The Fpg/Nei family of DNA glycosylases: substrates, structures, and search for damage. Prog. Mol. Biol. Transl. Sci. 110, 71–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dodson M. L., Michaels M. L., Lloyd R. S. (1994) Unified catalytic mechanism for DNA glycosylases. J. Biol. Chem. 269, 32709–32712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cloutier J. F., Drouin R., Castonguay A. (1999) Treatment of human cells with N-nitroso(acetoxymethyl)methylamine: distribution patterns of piperidine-sensitive DNA damage at the nucleotide level of resolution are related to the sequence context. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 12, 840–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pullman A., Pullman B. (1981) Molecular electrostatic potential of the nucleic acids. Q. Rev. Biophys. 14, 289–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Weiner P. K., Langridge R., Blaney J. M., Schaefer R., Kollman P. A. (1982) Electrostatic potential molecular surfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 79, 3754–3758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Miller F. J., Rosenfeldt F. L., Zhang C. F., Linnane A. W., Nagley P. (2003) Precise determination of mitochondrial DNA copy number in human skeletal and cardiac muscle by a PCR-based assay: lack of change of copy number with age. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Li S. (2011) N-Methylpurines are heterogeneously repaired in human mitochondria but not evidently repaired in yeast mitochondria. DNA Repair (Amst.) 10, 65–72, 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.09.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Loon B., Samson L. D. (2013) Alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG) localizes to mitochondria and interacts with mitochondrial single-stranded binding protein (mtSSB). DNA Repair (Amst.) 12, 177–187, 10.1016/j.dnarep.2012.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lau A. Y., Schärer O. D., Samson L., Verdine G. L., Ellenberger T. (1998) Crystal structure of a human alkylbase-DNA repair enzyme complexed to DNA: mechanisms for nucleotide flipping and base excision. Cell 95, 249–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Friedman R. A., Honig B. (1995) A free energy analysis of nucleic acid base stacking in aqueous solution. Biophys. J. 69, 1528–1535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ruszczynska K., Kamienska-Trela K., Wojcik J., Stepinski J., Darzynkiewicz E., Stolarski R. (2003) Charge distribution in 7-methylguanine regarding cation-π interaction with protein factor eIF4E. Biophys. J. 85, 1450–1456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mahadevi A. S., Sastry G. N. (2013) Cation-π interaction: its role and relevance in chemistry, biology, and material science. Chem. Rev. 113, 2100–2138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lyons D. M., O'Brien P. J. (2009) Efficient recognition of an unpaired lesion by a DNA repair glycosylase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 17742–17743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li S., Smerdon M. J. (2002) Nucleosome structure and repair of N-methylpurines in the GAL1-10 genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 44651–44659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li S., Smerdon M. J. (1999) Base excision repair of N-methylpurines in a yeast minichromosome: effects of transcription, DNA sequence, and nucleosome positioning. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 12201–12204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Friedman J. I., Stivers J. T. (2010) Detection of damaged DNA bases by DNA glycosylase enzymes. Biochemistry 49, 4957–4967 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sassa A., Beard W. A., Prasad R., Wilson S. H. (2012) DNA sequence context effects on the glycosylase activity of human 8-oxoguanine DNA glycosylase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 36702–36710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Allgayer J., Kitsera N., von der Lippen C., Epe B., Khobta A. (2013) Modulation of base excision repair of 8-oxoguanine by the nucleotide sequence. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, 8559–8571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]