Background: The most common microdeletion congenital disorder, 22qDS, is the second risk factor for schizophrenia.

Results: Plasma metabolomics in 22qDS consisted of an oxidative phosphorylation-to-glycolysis shift with altered 2-hydroxyglutaric acid, cholesterol, and fatty acid concentrations.

Conclusion: Despite the haploinsufficiency of ∼30 genes, the 22qDS metabolic signature chiefly reflected deficits in the mitochondrial citrate transporter.

Significance: Biochemical profiling of 22qDS unveiled the impact of SLC25A1 haploinsufficiency.

Keywords: bioenergetics, epigenetics, metabolomics, mitochondria, schizophrenia, OXPHOS, citrate transporter, mtDNA copy number

Abstract

The congenital disorder 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22qDS), characterized by a hemizygous deletion of 1.5–3 Mb on chromosome 22 at locus 11.2, is the most common microdeletion disorder (estimated prevalence of 1 in 4000) and the second risk factor for schizophrenia. Nine of ∼30 genes involved in 22qDS have the potential of disrupting mitochondrial metabolism (COMT, UFD1L, DGCR8, MRPL40, PRODH, SLC25A1, TXNRD2, T10, and ZDHHC8). Deficits in bioenergetics during early postnatal brain development could set the basis for a disrupted neuronal metabolism or synaptic signaling, partly explaining the higher incidence in developmental and behavioral deficits in these individuals. Here, we investigated whether mitochondrial outcomes and metabolites from 22qDS children segregated with the altered dosage of one or several of these mitochondrial genes contributing to 22qDS etiology and/or morbidity. Plasma metabolomics, lymphocytic mitochondrial outcomes, and epigenetics (histone H3 Lys-4 trimethylation and 5-methylcytosine) were evaluated in samples from 11 22qDS children and 13 age- and sex-matched neurotypically developing controls. Metabolite differences between 22qDS children and controls reflected a shift from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis (higher lactate/pyruvate ratios) accompanied by an increase in reductive carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate (increased concentrations of 2-hydroxyglutaric acid, cholesterol, and fatty acids). Altered metabolism in 22qDS reflected a critical role for the haploinsufficiency of the mitochondrial citrate transporter SLC25A1, further enhanced by HIF-1α, MYC, and metabolite controls. This comprehensive profiling served to clarify the biochemistry of this disease underlying its broad, complex phenotype.

Introduction

A hemizygous deletion of 1.5–3 Mb on chromosome 22q11.2 (spanning ∼30–45 genes) gives rise to 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (named hereafter 22qDS), a rather common congenital disorder (prevalence of 1 in 4000) (1). This syndrome is characterized by a complex phenotype that includes congenital heart defects, craniofacial and velopharyngeal defects, recurrent infections, endocrine dysfunction, neural anomalies, learning disabilities, developmental delay, social impairments, and behavioral problems that often lead to diagnoses such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (2). The 22qDS constitutes the third highest genetic risk factor for schizophrenia (3) at around 20–30% (4). Although this complex phenotype results from an altered copy number/dosage of one or a combination of genes located within the deleted region, limited research has shed light on the contribution to developmental pathogenesis underlying this syndrome (5). Meechan et al. (5) proposed that a substantial number of genes within the 22q11.2 region act specifically and in concert to mediate early morphogenetic interactions and subsequent cellular differentiation at phenotypically compromised sites (limbs, heart, face, and forebrain). Thus, if functionally similar subsets of 22qDS genes remain expressed, the regulation of neurogenesis and synaptic development occurs, particularly, in developing brain; however, if the dosage of these genes is decreased, particularly during early morphogenesis, localization and connectivity of neurons essential for normal behavior may be disrupted. Such disruptions probably change the course of neurocognitive development in ways that impair intellectual and social development and increase the risk for schizophrenia in individuals with 22qDS (6–8).

In this context, little is still known about how and which genes within the 22q11.2 segment contribute, singly or in combination, to the range of phenotypic variation. Of the many genes (about 30) implicated in the 1.5–3-Mb deleted region, nine of them have the potential to disrupt mitochondria dynamics: COMT, UFD1L, DGCR8, MRPL40, PRODH, SLC25A1, TXNRD2, T10, and ZDHHC8. Among these, the first three might have an indirect effect on mitochondrial function (particularly DGCR8), whereas the remaining six encode for mitochondrial proteins expressed maximally at a time that coincides with peak forebrain synaptogenesis shortly after birth (9). A mouse model of 22qDS, with the 1.5-Mb deletion encompassing the mitochondrial genes, suggests that altered dosage of one or more of these genes could lead to mitochondrial dysfunction and affect neuronal development, metabolism, and/or synaptic signaling (9). The authors proposed that this deletion may alter metabolic properties of cortical mitochondria during early postnatal life because expression of Complex III subunits was increased at birth in the 22qDS mouse model and declined to normal values in adulthood (9). However, mitochondrial biogenesis increases dramatically after birth in several tissues, including the brain (10). Deficiencies in mitochondrial metabolism due to altered dosage of one or several 22qDS mitochondrial genes, particularly during early postnatal brain development, could set the basis for a disrupted neuronal metabolism or synaptic signaling during perinatal periods, leading to alterations in neurocognitive development in ways that impair intellectual and social development and increase the risk for schizophrenia (3, 4, 6, 7). Although lower gene expression in individuals with 22qDS is expected, due to the presence of single copy genes, different genotypes from the remaining allele could be associated with specific gene dosage thresholds, as observed in other models (11). Furthermore, the presence of different genetic backgrounds has the potential to affect the phenotype (12). Indeed, as observed in the cardiac phenotype associated with the TBX1 gene, a specific gene dosage threshold may exist in which very small mRNA level reductions can worsen the phenotype very rapidly (13). In addition, 6 of ∼30 genes within 22qDS encode for mitochondrial proteins. It is likely that an underlying mitochondrial dysfunction in 22qDS is contributing to the etiology and/or morbidity of the syndrome.

To bridge this gap in knowledge, we performed plasma metabolomics and mitochondrial function in peripheral blood monocytic cells (PBMCs)3 from 22qDS children (n = 11) and age- and sex-matched typically developing (TD) controls (n = 13). Although the use of plasma and/or PBMCs could be criticized because they may not reflect changes in other cells, such as neurons, several reports have shown differential gene expression in PBMCs in disorders of the central nervous system (14–16). In this regard, the use of PBMC gene expression as a surrogate for the brain has been reported for humans (17) as well as for non-human primates (18). Moreover, to date, altered expression of miRNAs involved in brain plasticity and maturation with links to schizophrenia and other psychiatric diagnoses has been detected in both brain tissues and blood cells (4, 19, 20), suggesting that PBMCs could reflect or partly share the metabolism of neural cells and therefore that they could also be used in studies of psychiatric disorders. Our study provides novel information for the development of targeted therapeutics to overcome the altered gene expression that, alongside a range of developmental processes, may contribute to the etiology and/or morbidity of the phenotypic expression of 22qDS.

Experimental Procedures

Clinical Evaluation of Participants

Medical history and physical examination (including weight, height, and body mass index) were collected for all participants (Table 1). Medical history provided information about biological risk factors, such as congenital heart disease, immunedysfunction, endocrine abnormalities (hypocalcemia and hypothyroidism), seizures, and cleft palate or velopharyngeal dysfunction. The Social Communication Questionnaire (21) was used to screen for child autism features/social impairments, with scores greater than 15 suggestive of autism symptoms (22). The Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham Questionnaire, 4th edition (23) was used to identify inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and screen for psychiatric diagnoses. Items were rated on a 4-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very much). Average rating-per-item subscale scores for both parent and teacher scales were calculated for the inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity, and opposition/defiance domains.

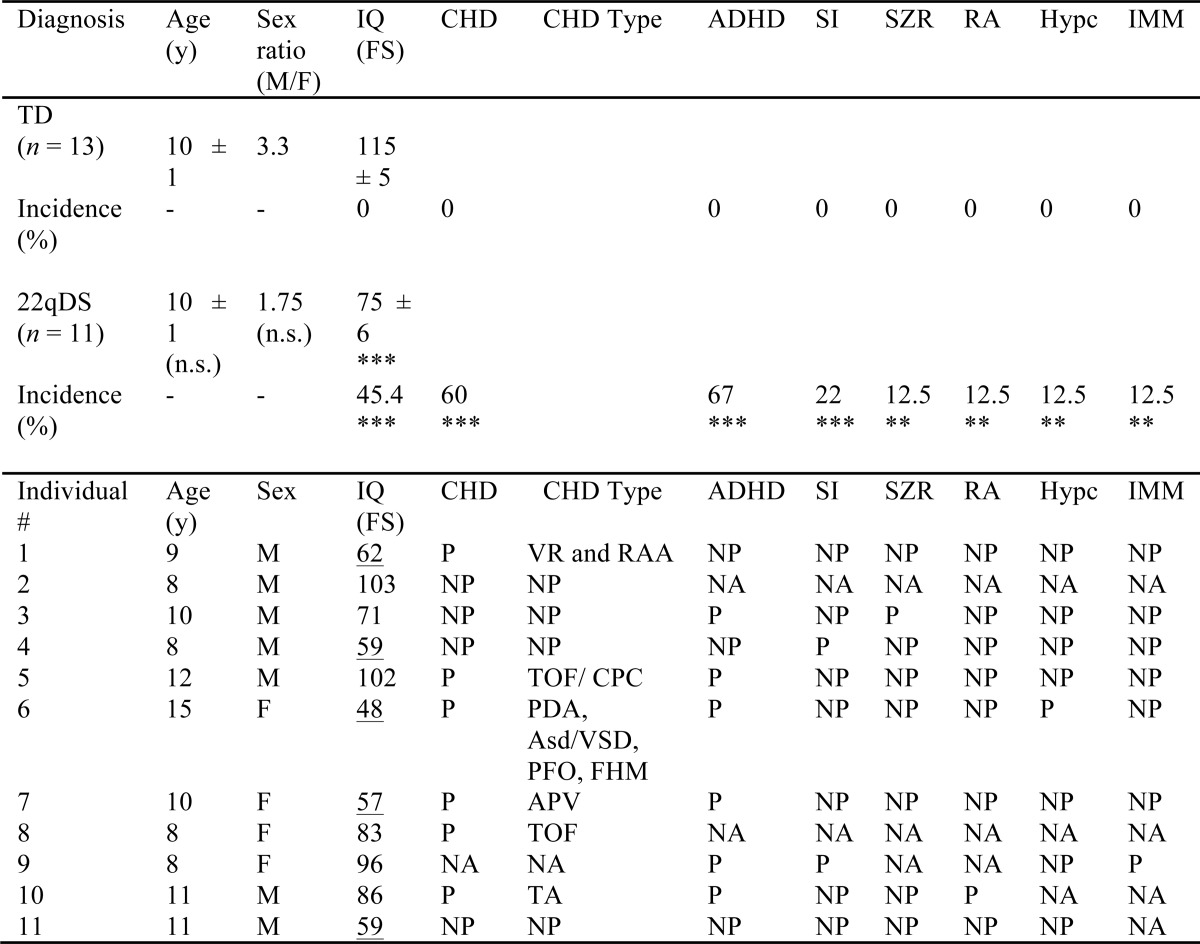

TABLE 1.

Details of the study population

NA, not available; NP, not present; P, present; n.s., not significant. Data are reported as mean ± S.E. ADHD, attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder; APV, absence of portal vein; Asd, atrial septal defect; CHD, congenital heart defect; CPC, choroid plexus cyst; FHM, functional heart murmur; FS, full scale; Hypc, hypocalcemia; IMM, immune dysfunction; IQ, intelligence quotient; PDA, patent ductus arteriosus; PFO, patent foramen ovale; RA, renal abnormalities; RAA, right atrial appendage; SI, social impairments; SZR, seizures; TA, trunchus arteriosus; TOF, tetralogy of Fallot; VR, venous return; VSD, ventricular septal defect. Underlined values are IQ scores < 70 (intellectually disability). Significance for the comparison between means was obtained by using the Student t-test, and between incidences was obtained by using the test for one proportion (**, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). No significant differences were observed for body mass index or head circumference; individual number 8 was the only one in this cohort classified as overweight.

Genetic Characterization of Subjects

Blood samples from children were collected, according to University of California, Davis, Institutional Review Board-approved human subject protocols, in PAXgene blood RNA tubes (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in addition to purple-top tubes (EDTA) for DNA isolation. Genomic DNA was isolated from 3–5 ml of PBMCs using standard procedures (Qiagen). PBMCs were isolated from BD Vacutainer CPT tubes (BD Biosciences) containing heparin, and PBMCs were separated, aliquoted, and stored in liquid nitrogen within 24 h of collection according to the manufacturer's directions. All 22qDS patients presented the 3-Mb deletion except for one subject who had the 1.5-Mb deletion. Diagnosis of 22qDS was performed by FISH using the TUPLE1 gene. Samples were also screened by droplet digital PCR, using a multiplex approach with the COMT and PIK4CA assays in order to differentiate between individuals with either the 1.5- or 3-Mb deletions. RPP30 was used as a reference control gene. Details of the methodology were described before (24).

Mitochondrial Outcomes

Mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) Copy Number

Changes in mtDNA copy number per PBMC were evaluated by dual-labeled probes using quantitative PCR by using the gene copy number of ND1 normalized by a single-copy nuclear gene pyruvate kinase (25).

Mitochondrial DNA Deletions

Patients with single and multiple mtDNA deletions have deletions in ND4 (mitochondrial gene encoding for the ND4 subunit of Complex I) and/or CYTB (mitochondrial gene encoding for cytochrome b), whereas the ND1 (mitochondrial gene encoding subunit ND1 in Complex I) is rarely deleted. Therefore, mtDNA microdeletions were estimated by using the gene copy number ratio of CYTB and ND4 normalized to ND1 with dual-labeled probes (26) in genomic DNA extracted from PBMCs. Incidence of deletions was counted if the Z-score was ≤−1.

Lactate and Pyruvate Ratios

Lactate concentration was measured with the YSI 2300 Stat Plus Glucose and l-Lactate Analyzer, model 2300D (YSI Life Sciences, Yellow Springs, OH). Pyruvate concentration was measured spectrophotometrically at 570 nm in 10 μl of plasma with a pyruvate colorimetric assay kit (BioVision, Milpitas, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Mitochondrial Enzymatic Measurements

Activities of cytochrome c oxidase and citrate synthase were analyzed spectrophotometrically in PBMCs from 22qDS and TD individuals as described previously (11).

Epigenetics

DNA Methylation

Genomic DNA was isolated from 3–5 ml of PBMCs from 13 TD and 11 22qDS individuals using standard procedures (Qiagen). The quantification of 5-methylcytosine was carried out with 100 ng of DNA using a 5-mC ELISA kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Western Blots for Histone H3K4 Trimethylation Levels

PBMCs were washed with PBS, pelleted by centrifugation at 300 × g for 5 min, and then extracted in 50 μl of radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. Cells were further homogenized by sonication for 2 × 30 s with a cooling interval of 1 min in ice. Protein concentrations of the samples were measured with the PierceTM BCATM protein assay kit (Thermo Scientific). Ten μg of protein were denatured in NuPAGE sample buffer (Invitrogen) plus 50 mm dithiothreitol at 70 °C for 10 min and then run in a 4–12% gradient BisTris gel with MES buffer. The iBlot system (Invitrogen) was utilized to transfer the proteins to a nitrocellulose membrane at P3 setting for 7 min. The membrane was washed with PBS and then blocked with (TBS) blocking buffer (LI-COR) for 1 h. Anti-histone H3 (trimethyl Lys-4) primary antibody (Abcam; 1:3000 dilution) was probed overnight at 0–4 °C. Anti-histone H3 antibody (Cell signaling; 1:1000) was probed for 3 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed with TBST three times for 10 min each. Secondary goat anti-rabbit IRDye 800RD or goat anti-mouse IRDye 680RD secondary antibody (LI-COR; 1:20,000 dilution) were added for 1 h at 20–22 °C. After three 10-min washes in TBST, the membrane was visualized by the Odyssey imaging system (LI-COR) and analyzed with the Carestream software (Eastman Kodak Co.).

Statistical Analyses

A priori analysis to compute the required sample size (given α = 0.05, power = 0.95, allocation ratio n TD/n 22qDS = 1.2) indicated that to detect a 0.5 S.D. difference within each group, the number of individuals per group would have to be 7 for controls and 9 for 22qDS. Post hoc analysis to compute the achieved power given the actual sample size utilized in this study (α = 0.05) indicated that it was >0.994 when performed with a selected group of metabolites (glucose, cholesterol, and proline), lactate/pyruvate ratio, and citrate synthase activity (G*Power version 3.0.10). An unpaired, two-tailed Student's t test was used to compare outcomes from 22qDS and TD individuals with a significance value of p < 0.05.

Metabolomics, Data Processing, and Multivariate Statistical Analysis

Analyte concentrations in plasma were determined by automated liner exchange-cold injection system-gas chromatography followed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry. The mass spectrometry was performed at the Metabolomics Facility at UC Davis. Data were normalized by vector normalization of identified metabolites. After verifying normal distribution of dependent variables by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, a one-way analysis of variance was carried out by using SPSS version 19.0 software (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL) to assess statistical difference in baseline characteristics and the content of each metabolite between the two diagnostic groups. A value of p < 0.05 was considered significant. The contents of metabolites from GC-MS were imported into XLSTAT for multivariate pattern recognition analysis. Partial least squares-discriminant analysis (PLS-DA), a method with the ability to effectively filter unrelated variations under a supervised model, was carried out to examine the distributions and discriminations among groups according to the metabolite patterns. S-plot and variable importance in projection (VIP) in the PLS-DA mode were implemented to search for important variables and potential biomarkers with the greatest contribution to discrimination. Pearson's correlation analysis between the contents of plasma metabolites and specific clinical features of 22qDS was conducted by using XLSTAT 2014.5.01 or GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

Results

Clinical Description of 22qDS Individuals

11 children (7 males and 4 females) diagnosed with 22qDS (age 8–15 years), 10 carrying the 3-Mb deletion and only one with a 1.5-Mb deletion, were recruited to ascertain putative metabolic disturbances originated directly or indirectly from a sole deleted gene or a combination of deleted genes within the 22q11.2 region. Their outcomes were compared with those of 13 typically neurodeveloping controls (10 males and 3 females) age 6–13 years. The incidence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorders (67%) was the highest in the 22qDS group, followed by (in decreasing order) congenital heart defects, low intellectual quotient (<70), and social impairments, with lower incidence of seizures, renal abnormalities, hypocalcemia, and immune dysfunction (Table 1). No differences were observed for head circumference or body mass index (not shown).

Metabolic Pattern Recognition of 22qDS Plasma Samples

Gas chromatography followed by time-of-flight mass spectrometry (GC-MS) was used to analyze plasma metabolites from control and 22qDS children. A total of 148 metabolites were identified, of which 34 were significantly different between children with 22qDS and controls (accounting for 23% of the ones identified). The majority of metabolites (94%) in 22qDS plasma samples were found at higher concentrations than controls (Table 2). Among them were higher concentrations of Pro and five other amino acids, two fatty acids, cholesterol, lactate, and 2-hydroxyglutaric acid (2HG).

TABLE 2.

Metabolite profiling from plasma of 22qDS compared with controls

Shown are significantly different metabolites between 22qDS and controls (Student's t test with p ≤ 0.05) and with a VIP of ≥0.8. The ratio of means (22qDS over controls) and their respective S.E. are shown. VIP was calculated from the PLS-DA run with all metabolites by using XLSTAT. In boldface type are shown metabolites involved in oxidative stress metabolism. NA, not available.

| KEGG | PUBCHEM | Compound | VIP | Ratio of means | S.E. of ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Higher abundance | |||||

| C00148 | 145742 | Proline | 1.47 | 2.22 | 1.02 |

| C00099 | 239 | β-Alanine | 1.19 | 2.14 | 0.99 |

| C01971 | 6255 | Cellobiose | 1.43 | 1.75 | 0.40 |

| C03046 | 262 | Butane-2,3-diol | 1.61 | 1.60 | 0.25 |

| C00064 | 5961 | Glutamine | 1.31 | 1.6 | 0.38 |

| C02989 | 158980 | Methionine sulfoxide | 1.62 | 1.60 | 0.23 |

| C00198 | 7027 | Gluconic acid lactone | 1.61 | 1.59 | 0.26 |

| C00135 | 6274 | Histidine | 1.42 | 1.56 | 0.30 |

| C00262 | 790 | Hypoxanthine | 1.61 | 1.54 | 0.19 |

| C03283 | 134490 | 2,4-Diaminobutyric acid | 1.28 | 1.45 | 0.22 |

| C00954 | 802 | Indole-3-acetate | 1.50 | 1.43 | 0.17 |

| C02630 | 43 | 2-Hydroxyglutaric acid | 1.64 | 1.42 | 0.15 |

| C00327 | 9750 | Citrulline | 1.49 | 1.37 | 0.15 |

| C00078 | 6305 | Tryptophan | 1.48 | 1.37 | 0.17 |

| NA | 150929 | 3,4-Dihydroxybutanoic acid | 1.49 | 1.36 | 0.13 |

| C00503 | 222285 | Erythritol | 1.46 | 1.33 | 0.12 |

| NA | 98009 | 2-Hydroxyvaleric acid | 1.18 | 1.32 | 0.18 |

| C00872 | 100714 | Aminomalonate | 1.74 | 1.28 | 0.08 |

| C00221 | 64689 | Glucose | 1.86 | 1.28 | 0.08 |

| C00160 | 757 | Glycolic acid | 1.28 | 1.25 | 0.11 |

| C02043 | 92904 | Indole-3-lactate | 1.40 | 1.25 | 0.17 |

| C06425 | 10467 | Arachidic acid | 1.17 | 1.24 | 0.10 |

| C01432 | 612 | Lactic acid | 1.10 | 1.23 | 0.11 |

| C00187 | 5997 | Cholesterol | 1.95 | 1.23 | 0.06 |

| C02457 | 10442 | Propane-1,3-diol | 1.81 | 1.22 | 0.06 |

| C00188 | 6288 | Threonine | 1.26 | 1.21 | 0.09 |

| C00079 | 6140 | Phenylalanine | 1.42 | 1.21 | 0.07 |

| C00978 | 903 | N-Acetyl-5-hydroxytryptamine | 1.49 | 1.20 | 0.07 |

| C01530 | 5281 | Stearic acid | 1.27 | 1.20 | 0.08 |

| C00192 | 787 | Hydroxylamine | 1.84 | 1.19 | 0.04 |

| C00065 | 5951 | Serine | 1.69 | 1.18 | 0.05 |

| C07064 | 11333 | Lactulose | 1.56 | 1.12 | 0.30 |

| Lower abundance | |||||

| C00022 | 1060 | Pyruvic acid | 1.20 | 0.58 | 0.16 |

| C02721 | 5288725 | N-Methylalanine | 1.41 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

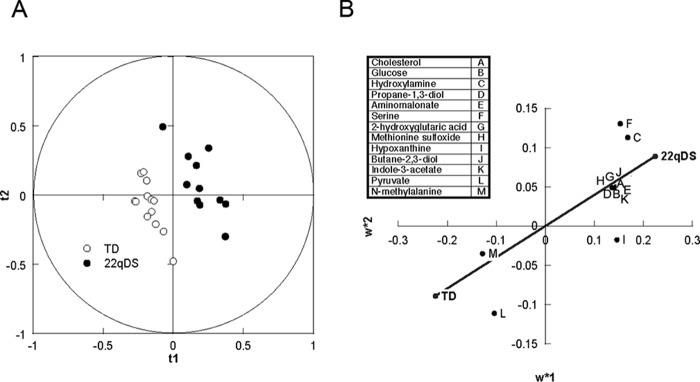

PLS-DA, a supervised multivariate statistical method for pattern recognition, was applied to discriminate the two diagnostic groups according to their differences in plasma metabolites profiles. In order to determine whether the plasma metabolite profile sufficiently distinguished between diagnostic groups (regardless of broad differences in the 22qDS phenotype), all children with 22qDS were combined as one class. Several parameters, including R2 and Q2, are commonly used to evaluate the quality and reliability of the PLS-DA model. The R2x(cum) and R2y(cum) represent explanatory capacity on variables in x and y matrices, whereas Q2(cum) explains the predictive power of the constructed model. All observations fell within the Hotelling T2 (0.95) ellipse, where the model fit parameters were 0.358 of R2x, 0.970 of R2y, and 0.711 of Q2 (Fig. 1A). These values indicated that the PLS-DA model constructed for simultaneous discrimination of controls and children with 22qDS has the appropriate fitness and prediction (R2 and Q2 ≤ 1). Indeed, the score plot analysis indicated that samples were clearly classified into two clusters (i.e. controls and children with 22qDS) according to the differences in their global plasma metabolite profiles (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

A, PLS-DA score plot based on the metabolomics profile of plasma from controls and 22qDS children. The plot of PLS-DA scores shows a significant separation between control subjects (n = 13) and 22qDS (n = 11) using complete digital maps. The observations were coded according to class membership: 22qDS (black circles) and controls or TD children (open circles). B, biomarker detection in plasma from 22qDS. The loading coefficient map shows that cholesterol, glucose, hydroxylamine, propane-1,3-diol, aminomalonate, Ser, and 2HG were predominantly responsible for the classification of the diagnostic groups.

In order to reveal potential metabolite biomarkers contributing the most to group separations, the S-plot and VIP were constructed following the PLS-DA (Fig. 1B). S-plot integrates covariance and loading plot of PLS-DA, in which the x axis and y axis represent variable contribution and variable confidence, respectively. The further the metabolite point departs from zero of the x axis and y axis, the more the metabolite contributes to group separation, and the higher reflects the confidence level of the metabolite for the difference between groups, respectively (27). The S-plot of controls and children with 22qDS showed that samples from those with 22qDS were higher than controls in cholesterol, glucose, hydroxylamine, propane-1,3-diol, aminomalonate, Ser, and 2HG, followed by others, and lower in metabolites, such as N-methyl-Ala and pyruvic acid (Fig. 1B).

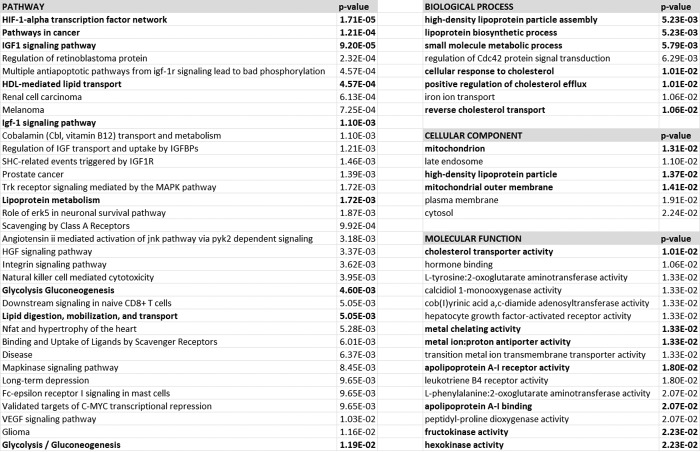

Biological Pathways Affected in 22qDS

To gain insight into the metabolic pathways in 22qDS that are different from controls, metabolomics data were analyzed by using PathVisio software (Table 3) and filtered by the false discovery rate p value ≤0.05 (28). This analysis revealed that solute-mediated transmembrane transport of small molecules was overrepresented in 22qDS. To avoid algorithm bias, the same analysis was carried out by importing metabolite data into REACTOME (29). This analysis confirmed previous conclusions obtained with PathVisio (30) in which the main pathways were related to transport of small molecules, tRNA aminoacylation, and metabolic genetic diseases (methylmalonic aciduria, 5-oxoprolinase deficiency, and multiple carboxylase deficiency among others; not shown). Proteins, mapped as identities by REACTOME based on the metabolite profile, were imported into INNATE for further pathway analysis because this resource includes data from databases other than REACTOME (Fig. 2). This analysis indicated the HIF-1α transcription factor network as the most significant pathway, followed by cancer pathways, IGF1 (insulin-like growth factor 1) signaling pathways, and lipoprotein metabolism. The mapped proteins were also analyzed by their gene ontology subdivided into biological processes, cellular component, and molecular function. Within the biological processes (Fig. 2), lipoprotein assembly, transport, and cholesterol metabolism scored as the most significant. In terms of the cellular component, mitochondrion and lipoprotein (assembly) were also significantly represented (Fig. 2), whereas the most represented molecular functions were cholesterol transport activity, apoprotein receptor activity, metal binding, and several dehydrogenases and kinases within the glycolytic pathway (Fig. 2).

TABLE 3.

Differential representation of pathways in 22qDS

Analysis was performed by uploading the metabolites' values and using PathVisio (28) to determine the enrichment of pathways. Pathways were filtered by the false discovery rate (p value ≤ 0.05). FDR, false discovery rate.

| Pathway identifier | Pathway name | Entities |

Reactions |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Found | Total | Ratio | Log (p value) | Log (FDR) | Found | Total | Log (ratio) | ||

| 352230 | Amino acid transport across the plasma membrane | 10 | 64 | 0.0070 | −7.77 | −5.13 | 26 | 34 | −2.3 |

| 70614 | Amino acid synthesis and interconversion (transamination) | 9 | 49 | 0.0054 | −7.64 | −5.13 | 12 | 22 | −2.5 |

| 442660 | Na+/Cl−-dependent neurotransmitter transporters | 9 | 50 | 0.0055 | −7.56 | −5.13 | 9 | 15 | −2.7 |

| 427975 | Proton/oligonucleotide cotransporters | 7 | 25 | 0.0027 | −7.27 | −4.97 | 2 | 2 | −3.5 |

| 425393 | Transport of inorganic cations/anions and amino acids/oligopeptides | 13 | 144 | 0.01581 | −7.16 | −4.95 | 32 | 65 | −2.0 |

| 425407 | SLC-mediated transmembrane transport | 21 | 419 | 0.0460 | −6.86 | −4.73 | 52 | 179 | −1.6 |

| 159424 | Conjugation of carboxylic acids | 6 | 23 | 0.0025 | −6.13 | −4.13 | 6 | 6 | −3.1 |

| 156587 | Amino acid conjugation | 6 | 23 | 0.0025 | −6.13 | −4.13 | 6 | 6 | −3.1 |

| 425366 | Transport of glucose and other sugars, bile salts and organic acids, metal ions and amine compounds | 13 | 181 | 0.0199 | −6.04 | −4.10 | 16 | 74 | −2.0 |

| 177135 | Conjugation of benzoate with glycine | 5 | 13 | 0.0014 | −6.01 | −4.10 | 2 | 2 | −3.5 |

| 174403 | Glutathione synthesis and recycling | 7 | 42 | 0.0046 | −5.78 | −3.91 | 5 | 9 | −2.9 |

| 379726 | Mitochondrial tRNA aminoacylation | 9 | 85 | 0.0093 | −5.66 | −3.83 | 21 | 21 | −2.5 |

| 379716 | Cytosolic tRNA aminoacylation | 9 | 88 | 0.0097 | −5.53 | −3.74 | 21 | 21 | −2.5 |

| 382551 | Transmembrane transport of small molecules | 25 | 731 | 0.0802 | −5.06 | −3.29 | 61 | 270 | −1.4 |

| 71291 | Metabolism of amino acids and derivatives | 17 | 383 | 0.0420 | −4.92 | −3.22 | 43 | 172 | −1.6 |

| 156580 | Phase II conjugation | 13 | 229 | 0.0251 | −4.94 | −3.22 | 20 | 55 | −2.1 |

| 379724 | tRNA aminoacylation | 9 | 106 | 0.0116 | −4.89 | −3.22 | 42 | 42 | −2.2 |

| 1236978 | Cross-presentation of soluble exogenous antigens (endosomes) | 7 | 69 | 0.0076 | −4.39 | −2.74 | 1 | 5 | −3.1 |

| 156590 | Glutathione conjugation | 7 | 72 | 0.0079 | −4.28 | −2.66 | 5 | 11 | −2.8 |

| 71406 | Pyruvate metabolism and citric acid cycle | 7 | 76 | 0.0083 | −4.13 | −2.54 | 22 | 26 | −2.4 |

| 428559 | Proton-coupled neutral amino acid transporters | 3 | 6 | 0.0007 | −4.12 | −2.54 | 2 | 2 | −3.5 |

| 73848 | Pyrimidine metabolism | 7 | 81 | 0.0089 | −3.96 | −2.41 | 19 | 34 | −2.3 |

| 15869 | Metabolism of nucleotides | 11 | 216 | 0.0237 | −3.84 | −2.30 | 53 | 118 | −1.8 |

| 1236977 | Endosomal/vacuolar pathway | 7 | 97 | 0.0107 | −3.49 | −1.99 | 2 | 4 | −3.2 |

| 177162 | Conjugation of phenylacetate with glutamine | 3 | 10 | 0.0011 | −3.47 | −1.98 | 2 | 2 | −3.5 |

| 804914 | Transport of fatty acids | 3 | 12 | 0.0013 | −3.24 | −1.76 | 1 | 1 | −3.8 |

| 70635 | Urea cycle | 4 | 30 | 0.0033 | −3.15 | −1.68 | 5 | 8 | −2.9 |

| 177128 | Conjugation of salicylate with glycine | 3 | 15 | 0.0017 | −2.96 | −1.53 | 2 | 2 | −3.5 |

| 425397 | Transport of vitamins, nucleosides, and related molecules | 6 | 92 | 0.0101 | −2.84 | −1.42 | 11 | 32 | −2.3 |

FIGURE 2.

Overrepresented biological pathways, biological processes, cellular components, and molecular functions in 22qDS. The mapped proteins, generated from metabolomics by REACTOME, were further analyzed by using Innate (96, 97).

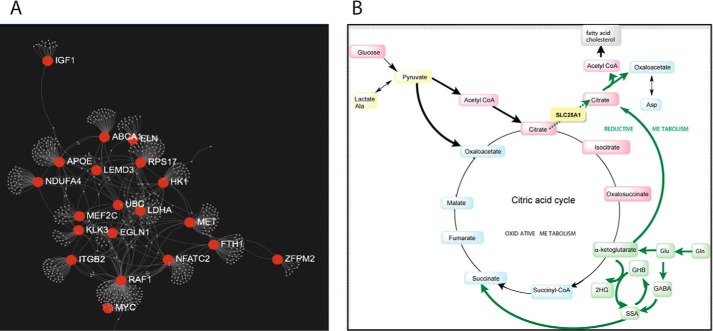

The mapped proteins were analyzed for network connectivity, resulting in the mapping of 679 genes (Fig. 3A). The main network nodes (with a degree of 10 or above) were constituted by the following 17 genes: RAF1, LDHA, RSP17, APOE, MET, NFATC2, ITGB2, FTH1, NDUFA4, ABCA1, MEF2C, KLK3, EGLN1, ELN, IGF1, UBC, and ZFPM2 (Fig. 3A). A subset of these 17 nodes consists of genes involved directly or indirectly with energy homeostasis and/or mitochondria metabolism (IGF1, HK1, LDHA, NDUFA4, RAF1, NFATC2, ITGB2, EGLN1, and MET) (Fig. 3A).

FIGURE 3.

Interacting genes and energy metabolism-related metabolic pathways in 22qDS. A, network of interacting genes in 22qDS. The mapped proteins, generated from metabolomics, were further analyzed in terms of network connectivity (NetworkAnalyst (98)). The plot shows the main nodes (with a degree of 10 or above) of 679 genes mapped. B, schematic representation of the deficits in SLC25A1 (in yellow) function leading to a decreased flux of citrate from mitochondria to the cytosol. The increased reductive metabolism of αKG from Gln (in green) in 22qDS, probably favored by a reprogramming of HIF-1α under normoxia and MYC, leads to increases in 2HG as well as increased citrate synthesis. Citrate, as a precursor of cytosolic acetyl-CoA, favors the synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol. Boldface arrows, steps with increased flux.

Further analyses to discern which transcription factors are associated with the profile of metabolites and proteins were accomplished by using the CisRed database. In this case, the MYC-MAX (p = 0.034; not shown) was significantly represented. The proto-oncogene MYC regulates glucose metabolism by inducing expression of key glycolytic enzymes, including lactate dehydrogenase and hexokinase, but also controls mitochondrial metabolism, because chronic depletion of MYC reduces mitochondrial mass, results in smaller and cristae-deficient mitochondria, and alters the dynamics of mitochondria fission and fusion, leading to reduced OXPHOS capacity (31, 32). Like MYC, HIF-1α also promotes glycolysis by inducing expression of glycolytic enzymes, and, when MYC expression is deregulated in cancers (amplified or translocated), both MYC and HIF-1α cooperate to regulate glucose metabolism.

Taking these results altogether, it appears that in 22qDS there is an underlying biochemistry that resembles that of cancer-related pathways with influences from HIF-1α and MYC and a clear contribution from a defective transport of small molecules. Consistent with this view, children with 22qDS are haploinsufficient for the mitochondrial citrate-H+/malate transporter, solute carrier family 25, member-1 (SLC25A1), which is required for the endogenous synthesis of fatty acids and cholesterol. However, an increased concentration of plasma cholesterol and fatty acids (and lactate) was observed in 22qDS (Table 2). To bridge this apparent discrepancy, we hypothesized that a shift toward glycolysis may favor the utilization of Gln as an anaplerotic carbon source for the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle, allowing the synthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids via reductive carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate (αKG) to citrate in mitochondria (33, 34). This switch would rely on mitochondria for biosynthetic processes to sustain growth rather than solely on ATP synthesis. By promoting glycolysis, as observed in tumors, a trade-off is set between a process that provides ATP at a lower efficiency but sustains rapid growth by providing precursors for biosynthetic pathways (e.g. Ser and nucleotide biosynthesis) as well as inducing key enzymes of biosynthetic processes (e.g. carbamoyl phosphate synthase II and Asp transcarbamylase (35)).

Shift from OXPHOS toward Glycolysis and from Oxidative to Reductive Carboxylation of Gln to Citrate in 22qDS

To gain insight into the shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis, we evaluated the lactate/pyruvate (L/P) ratios in plasma (36, 37). Considering that the plasma molar L/P ratio is <18.4 in defects of the pyruvate dehydrogenase complex and is >23.3 for hypoxia and primary (or secondary) respiratory chain defects (36–38), the high molar L/P ratio in 22qDS plasma samples (>50) sets it clearly within the last category (Table 4). High ratios of L/P as well as high Ala-to-pyruvate ratios (Ala is the transamination product of pyruvate) were obtained by GC-MS, confirming lower OXPHOS in 22qDS. The individual [pyruvate]/[glucose], and [lactate and Ala]/[glucose] ratios showed a trend toward lower (0.45-fold) and higher (1.97-fold) values, respectively, than controls. Thus, the increased L/P ratio in 22qDS indicated a shift of glucose metabolism from OXPHOS to glycolysis, as indicated by the higher percentage of ATP derived from glycolysis (1.47-fold; Table 4).

TABLE 4.

Plasma metabolites and mitochondrial outcomes in TD and 22qDS children

| Diagnosis | Outcome (mean ± S.E.) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plasma |

PBMC |

|||||||

| Ala/Pa,b | L/Pb | L/Pc | ATP from glycolysisd | Complex IV activitye | Citrate synthase activitye | Complex IV/CS | mtDNA copy number/cell | |

| % | ||||||||

| TD | 415 ± 92 | 345 ± 81 | 24 ± 6 | 17 ± 7 | 122 ± 23 | 137 ± 15 | 0.96 ± 0.23 | 226 ± 6 |

| 22qDS | 796 ± 203 | 720 ± 175 | 55 ± 44 | 25 ± 12 | 138 ± 42 | 181 ± 14 | 0.77 ± 0.28 | 292 ± 29 |

| pf | 0.054 | 0.036 | 0.025 | 0.068 | 0.379 | 0.030 | 0.281 | 0.003 |

a Ala/pyruvate ratio.

b From metabolomics data.

c L/P ratio was performed by evaluating lactate and pyruvate concentrations by an enzymatic assay as described under “Experimental Procedures” to obtain quantitative data that could be compared with published values.

d ATP from glycolysis was calculated as the percentage of plasma lactate generated per glucose for each individual, taking as 100% the theoretical value of 2 lactate (or 2 ATP) per glucose.

e Expressed as nmol of product × (min × mg of protein)−1; Complex IV/CS ratio was determined with both activities expressed as nmol of product × (min × mg of protein)−1. Data are shown as mean ± S.E.

f p value for mean comparisons was determined by using Student's t test.

To complement the above studies, PBMCs from five controls and four children with 22qDS (sex- and age-matched) were used to obtain more detailed information on bioenergetics. PBMCs from 22qDS showed an increased activity of citrate synthase and mtDNA copy number/cell (Table 4) with no changes in Complex IV activity when normalized by citrate synthase. Although the increase in citrate synthase activity may reflect an increase in citrate synthesis as a result of SLC25A1 deficits, the increases in mtDNA copy number seemed to be ascribable to increased oxidative stress. The mitochondrial electron transport chain is the major intracellular source of reactive oxygen species, and, as such, the mitochondrial DNA becomes one of the main targets for mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated damage, as evidenced by its relatively high mutation rate (39) and accumulation of deletions with age (40, 41). Under high oxidative stress conditions, the mtDNA copy number per cell and mtDNA deletions are usually increased (42, 43) in an attempt to maintain a normal level of “undamaged” template without increases in either OXPHOS or mitochondrial mass (11, 44–49). Deletions in the segment encoding for CYTB were evident in 22qDS carriers (4.8% versus <1.0% for 22qDS and controls, respectively, p = 0.092), with a higher incidence of individuals with deletions in the segments encoding for CYTB and ND4 (2.1- and 5-fold, respectively; χ2 test, p < 0.05).

Although we cannot rule out deficits in complexes other than Complex IV, a lower OXPHOS capacity in 22qDS was clearly implied by the high L/P ratio (Table 4). Furthermore, the higher plasma concentration of 2HG in 22qDS (1.3-fold; Table 2), a metabolite whose concentration has been found elevated under hypoxia (33, 34), suggested not only a shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis but also a shift from normal metabolism (in which citrate is mainly provided by glucose via pyruvate dehydrogenase complex) to an increased Gln reductive carboxylation to citrate (Gln → Glu → αKG via isocitrate dehydrogenases IDH1 or IDH2 to isocitrate → isomerization to citrate) to sustain both citrate synthesis and cell growth under conditions of mitochondrial dysfunction (Fig. 3B).

In support of a shift from oxidative carboxylation (glucose → pyruvate → citrate) to reductive carboxylation (Gln → citrate), leading to increases in citrate from Glu/Gln in 22qDS, we observed an increased concentration of (a) 2HG; (b) precursors of Glu/Gln (His and Pro); and (c) fatty acids (C18 and C20) and cholesterol, probably originating from citrate-derived acetyl-CoA (Table 2). As hypothesized before, these changes seem to originate from the haploinsufficiency of SLC25A1.

Of note, 22qDS and the combined dl-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (OMIM 61582 (50)), originating from homozygous or heterozygous inactivating mutations in SLC25A1, seem to share some common underlying molecular mechanisms. This autosomal recessive neurometabolic disorder results in the accumulation of 2HG isomers (51, 52). These compounds are metabolic intermediates in reactions catalyzed by malate dehydrogenase and hydroxyacid-oxoacid transhydrogenase (53, 54), and accumulation of 2HG affects some metabolic processes, such as the TCA cycle and branched-chain amino acid metabolism (55, 56). It is characterized by elevated urinary levels of Krebs' cycle intermediates and neonatal-onset encephalopathy with severe muscular weakness, intractable seizures, respiratory distress, and lack of psychomotor development, resulting in early death (1 month to up to 5 years in age; summarized in Ref. 57). Interestingly, the knockdown of SLC25A1 in zebrafish leads to mitochondria depletion and to proliferation defects that recapitulate features of the human velo-cardio-facial syndrome (i.e. cardiac defects, facial and jaw anomalies, and cleft palate) phenotype rescued by blocking autophagy (58). Although the concentration of 2HG was significantly higher in 22qDS plasma compared with controls, it was below that observed in patients with combined dl-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (3–50-fold of control levels; calculated from Ref. 50). This would explain the moderately lower ratios of citrate and/or isocitrate to the sum of malate and succinate (not shown) compared with the significantly lower ones in both urine and fibroblasts of dl-2HG compared with controls (50).

Epigenetics and 2HG in 22qDS

High 2HG concentrations are potentially interesting, because the d-isomer (d-2HG) may act as a competitive inhibitor of various αKG-dependent enzymes, including the TET (ten-eleven translocation) family of 5-methylcytosine hydroxylases and the Jumonji-C domain-containing histone demethylases (60, 61), resulting in global hypermethylation and changes in gene expression in cancer tissues (62). However, no statistically significant difference was seen in the average of H3K4 trimethylation (H3K4me3), a mark associated with active transcription (OD of H3K4me3/H3: TD = 0.66 ± 0.02; 22qDS = 0.54 ± 0.07; p = 0.170), or 5-methylcytosine (5-methylcytosine content: TD = 16 ± 2; 22qDS = 14 ± 2; p = 0.171) between 22qDS PBMCs compared with controls. Although these results precluded a 2HG-mediated inhibition of these enzymes, the incidence of 5-methylcytosine and H3K4me3 hypomethylation in 22qDS was 2-fold that of TD (χ2 test, p = 0.0182), suggesting an increased activity of demethylases with increased gene repression. Indeed, we found a significant homology between mitochondrial downstream targets of RBP2 or KDM5A (histone demethylase that specifically demethylates H3K4) and the predicted mitochondrial deficiencies inferred from the metabolomic analyses (compare with Ref. 63), among them enzymes of fatty acid oxidation; methylmalonyl-CoA mutase; several transporters; and subunits of Complex I, II, and III.

Another group of αKG-dependent enzymes is constituted by the prolyl hydroxylases. Relevant substrates of prolyl hydroxylase domain-containing proteins (also known as ELGN) and collagen prolyl 4-hydroxylases are the HIF-1/2α and various collagen proteins, respectively. An involvement of 2HG at stabilizing or transactivating HIF-1/2α seems likely given that 2HG can compete efficiently for ELGN, resulting in HIF-1/2α stabilization, promoting the activation of numerous genes ensuing in the activation of a cancer-like gene display, including glycolysis (61, 64). On the other hand, the levels of 4-hydroxyPro in 22qDS were not different from controls, suggesting that 2HG have not interfered with the hydroxylation of Pro in collagen.

Plasma Metabolites in 22qDS Resemble Propionic and Methylmalonic Acidemia

Several other metabolites were increased in the plasma of children with 22qDS, resembling the genetic disorder propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency. In this disorder, the catabolism of several compounds is disrupted, namely Val, Ile, Met, Thr, pyrimidines, cholesterol, and odd-chain-length fatty acids, with increased plasma levels of Gly and ammonia (as well as its oxidation product hydroxylamine). Indeed, higher mean levels of β-Ala (product of Asp and pyrimidine catabolism) and citrulline (urea cycle), 2,3-butanediol, 1,3-propanediol, and 2-hydroxyvaleric acid (Table 2), is consistent with the biochemistry underlying the defects in congenital propionic and methylmalonic acidemia (65). Deficiency in this pathway, due to the large number of substrates that normally contribute to it, may act as a CoA sink resulting in CoA deficiency if no cleavage of propionyl-CoA (or other acyl-CoA) to propionic acid occurs.

As discussed above, hyper-β-alaninemia (degradation product of Asp or dihydrouracil) has been reported elevated in propionyl-CoA carboxylase deficiency but also in other various genetic disorders with deficits in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, and GABA transaminase. However, given that no increased concentrations of uracil or thymidine (dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase) or GABA (GABA transaminase) were observed in 22qDS plasma samples, it is likely that the higher β-Ala concentration is the result of an increased RNA catabolism, probably via an increased nonsense RNA-mediated decay. An activation of the GABA shunt is supported by the increased levels of 3,4-dihydroxybutyrate (1.36-fold control levels; Table 2), suggesting deficits in succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase activity, because it is observed in patients with succinic semialdehyde dehydrogenase deficiency (Table 2).

Role of Haploinsufficiency of 22q11.2 Genes Other than SLC25A1 Evidenced by Metabolomics and Mitochondrial Outcomes

Our combined results pointed to the effect ofthe haploinsufficiency of three other genes, in addition to SLC25A1: PRODH, TXNRD2, and DGCR8.

The product of PRODH catalyzes the rate-limiting two-electron oxidation of the catabolism of Pro, resulting in the formation of 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate, with the product FADH2 being used at the electron transport chain (66, 67). 1-Pyrroline-5-carboxylate is the intermediate providing a direct carbon bridge connecting the Krebs' cycle and the urea cycle (68). Consistent with PRODH haploinsufficiency, hyperprolinemia (1.47-fold control levels; Table 2) was observed in 22qDS samples, accompanied by increases in the urea cycle metabolites Gln and citrulline. The phenotypic diversity in 22qDS carriers with identical PRODH haploinsufficiency, the lack of hyperprolinemia across all 22qDS patients (36% versus 7.7% in 22qDS and controls, respectively; test for one proportion, Z = 3.52, p = 0.0004, 95% confidence interval = 10.71–68.90), and the role of the HIF-1α pathway mentioned above suggest that PRODH activity, modulated by either polymorphisms in the remaining allele (69) or as a p53 downstream target (70), may affect the Glu/αKG levels, which in turn modulate the HIF-1α signaling pathway (68). Consistent with this view, the higher incidence of malignancies in DiGeorge syndrome carriers (71) may also be ascribed to the role of PRODH acting as a tumor suppressor via HIF-1α signaling (68).

The TXNRD2 gene encodes for a mitochondrial thioredoxin reductase that catalyzes the reduction of the active disulfide of thioredoxin 2 and other substrates (72), playing a critical role in the antioxidant defenses. Because the mtDNA copy number and mtDNA deletions were both increased in 22qDS PBMCs (see above), several plasma metabolites were also indicative of increased oxidative stress. In this regard, we observed an increased flux through the pentose phosphate shunt (gluconolactone, erythritol; Table 2) and products of oxidatively modified proteins (Met sulfoxide from Met, indole-3-lactate from Trp, and aminomalonate (73); Table 2) and hexoses (5-hydroxymethyl-2-furanoic acid, hexuronic acid (74, 75); Table 2).

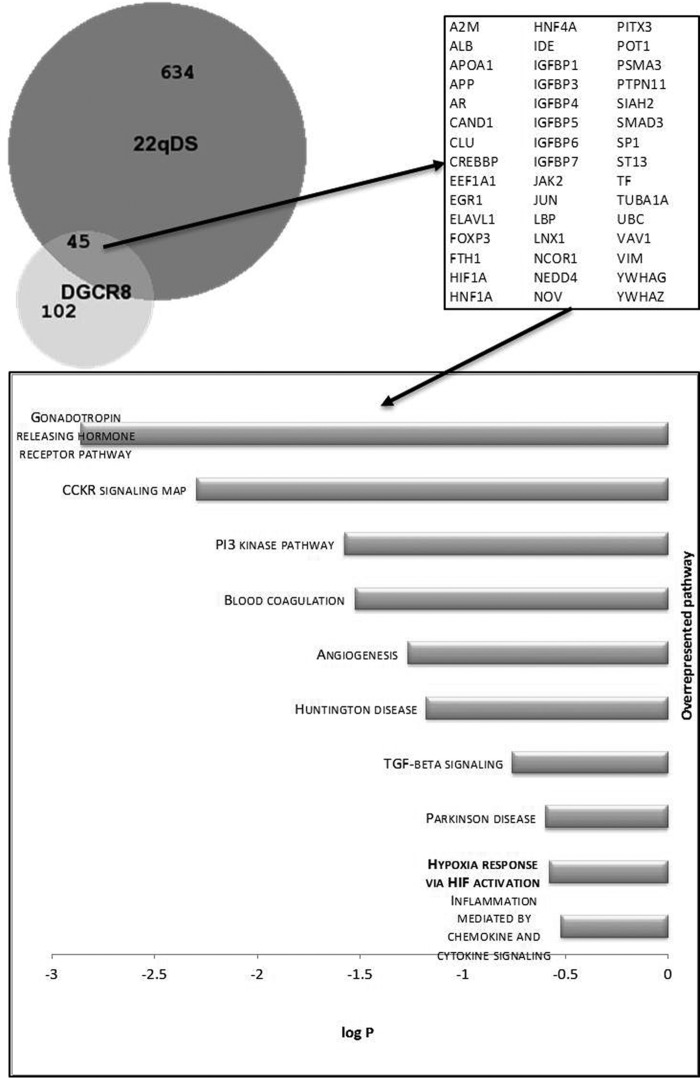

In terms of DGCR8 and given that its gene expression has been found decreased in individuals with 22qDS (76), we sought to evaluate whether any of the mapped identities (from REACTOME) overlapped with those involved with or connected to DGCR8-dependent pathways. From the network of genes cast solely by DGCR8 (filtered by a degree of 1 or above; n = 147), 5.76% were in common with the pathway generated by the metabolomics data presented in this study (Fig. 4), suggesting that a minor portion of the metabolite imbalances observed in 22qDS fraction (based on the number of overlapping genes but not on biological impact) has the potential to arise from the DGCR8 haploinsufficiency.

FIGURE 4.

Proteins identified under REACTOME analysis as a result of the uploaded metabolomics data were analyzed by using a network analysis and visualization application (98), as described in the legend to Fig. 3. All nodes that resulted from this analysis were compared with those resulting from the analysis performed when using DGCR8 as a query. Both lists of proteins were then compared and visualized using an area-proportional Venn diagram (59). The numbers in the diagram indicate the absolute number of mapped identities for each condition (22qDS or DGCR8). The 45 overlap identities are shown in the right panel. The bottom panel highlights the overrepresented pathways of the proteins in the intersection.

Discussion

This study has revealed four novel and interesting findings in the 22q11.2 deletion syndrome.

First, clear metabolic differences between children with 22qDS and age- and sex-matched controls were observed, reflecting a procatabolic phenotype with a dysregulation in energy homeostasis. Some of the observed changes reflect a combination of those shared by other disorders, such as cancer (glyomas and acute myeloid leukemias with IDH1/2 mutations (64)), combined dl-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (50, 77), and methylmalonic and propionic aciduria (65). This emphasizes the concept that metabolite profiling in plasma could be used as a biomarker to monitor the progress and the potential response to therapeutic approaches of this disease.

Second, and possibly the most remarkable finding, clear differences in biomarker profiles were observed within children with 22qDS, consistent with the broad presentation of symptoms. In this regard, this genetic disorder was found to underlie different features (e.g. DiGeorge syndrome, velocardiofacial syndrome, and cardiofacial syndrome) that are now known to be etiologically identical and are referred to as 22q11.2 DS. In our study, although most children with 22qDS (irrespective of the symptom status) had elevated levels of cholesterol (73% above 95% confidence interval) or 2HG (64%), less than half were associated with hyperprolinemia (36%). Thus, when mean comparisons are made between diagnostic groups, subtle differences among patients may be overlooked. Accordingly, the complex analyses of the dysregulation of intermediary metabolism among 22qDS cases may be a useful independent state marker to make rational decisions in terms of personalized therapy. For instance, to minimize the challenge through the path that leads to propionyl-CoA, it is suggested that some of these patients may benefit from a low protein diet, devoid of odd-chain-length fatty acids, preventing fasting periods, and increase the intake of carnitine (which should help with the disposal of propionic acid) and B12 (to maintain a saturation of the mutase).

Third, the occurrence of a shift from OXPHOS to glycolysis in 22qDS was accompanied by an increase in reductive metabolism of Gln/αKG. This shift seemed to be initiated by the deficits in SLC25A1 and sustained by the actions of HIF-1α and MYC-MAX (33, 34). Increased glycolysis could also be further promoted by the increased cytosolic citrate, originating from the sole SLC25A1 haploinsufficiency, which is an allosteric inhibitor of 6-phosphofructokinase-1, the main regulator of glycolysis (78). The shift to glycolysis, while providing less efficiently ATP for cellular processes than OXPHOS, provides for metabolites required for rapid cell growth and proliferation. In addition, it provides biochemical evidence for metabolite-driven changes resulting in the broad phenotypic differences in 22qDS. The elevation of 2HG is remarkable in two instances. (a) a 30% increase in total 2HG in plasma may reflect a significantly higher intracellular (more specifically intramitochondrial) concentration suggesting that accumulation of this metabolite has the potential to inhibit Complex IV (IC50 for d-2HG = 0.3 mm (79–81)), Complex V (IC50 for d-2HG and l-2HG ∼8 and 10 mm, respectively (82)), and creatine kinase (IC50 for d-2HG = 1–10 mm (83, 84)) and also increased oxidative stress (85, 86), leading to a secondary block of the TCA cycle. This would result in higher [NADH]/[NAD+] and [FADH2]/[FAD+] ratios, resulting in the production of NADPH (at the expense of NADH) via the mitochondrial nicotinamide nucleotide transhydrogenase to sustain IDH2 activity and the reductive carboxylation of Gln to citrate. (b) 2HG, by acting as a competitive inhibitor of several αKG-dependent enzymes, connects intermediary metabolism with epigenetics. The increased 2HG segregated with an increased “glycolytic response,” similar to that shared by stabilization of HIF-1/2α and the trend toward hypomethylation of KDM5A target genes. Further work will be required to test where 2HG is elevated (organ and subcellular location), to what extent it is altered, and at what stages of the disease; however, the metabolite changes (especially 2HG, lactate, and pyruvate) are all consistent with a dysregulation of intermediary metabolism and energy homeostasis in 22qDS. The fact that the higher L/P ratio segregated with 22qDS, in which affected children are usually less active than TD because they are limited in the amount and type of physical exercise they can tolerate, further indicates that the differences could not be attributed to disparities in diet and exercise habits (both groups were matched for sex, age, and geographical area, with no differences in body mass index).

Furthermore, because during brain development, energy requirements are high and in their most vulnerable phase (87, 88), other brain-specific effects of 2HG could also be envisioned. d-2HG is taken up by astrocytes at high rates, potentially interfering with the uptake of αKG via the Na+-dependent dicarboxylate transporter 3 (89, 90). This impaired uptake could interfere with the astrocytes' anaplerotic ability to support neurons with compounds needed for synthesis of neurotransmitters inducing neuronal dysfunction manifesting as seizures or other neurobehavioral disturbances.

Finally, although cholesterol is available through both diet and endogenous synthesis in most organs, and the overcompensation of endogenous fatty acid and sterol synthesis, including cholesterol via higher flow through reductive carboxylation, could be perceived as an adaptation and, therefore, not pathogenic, it is important to point out that the developing and mature central nervous system is dependent on endogenous cholesterol synthesis (91–93). Indeed, a number of human malformation syndromes have been associated with defects in sterol synthesis, including the autosomal recessive disorders, such as Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome. Relevant to this study, Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome shares some features with 22qDS (cleft palate, congenital heart defects, gastrointestinal problems, and learning and/or psychiatric disorders (94)). As with 22qDS, genotype-phenotype correlations in Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome are poor (95) because many missense mutations result in residual enzymatic activity of the remaining allele. As indicated above, factors other than genotype and residual activity appear to significantly influence subject phenotype (95), including endogenous factors affecting the function of other genes involved in brain cholesterol homeostasis, embryonic development, or maternal factors.

Author Contributions

E. N. measured some mitochondrial outcomes, analyzed the data, helped with drafting, and reviewed the manuscript; F. T. characterized the size of the deletions and reviewed the manuscript; S. W. measured mtDNA CN and reviewed the manuscript; K. A. and T. J. S. clinically evaluated all patients, provided all clinical data, and provided input for the manuscript; G. S. measured the mitochondrial enzymatic activities; C. G. conceptualized the work, analyzed the metabolomics data, and drafted and reviewed the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank all children and their families who participated in this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants NIEHS020392 and HD036071. This work was also supported by Simons Foundation Grant 271406. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PBMC

- peripheral blood monocytic cell

- TD

- typically developing

- mtDNA

- mitochondrial DNA

- H3K4

- histone H3 Lys-4

- H3K4me3

- H3K4 trimethylation

- BisTris

- 2-[bis(2-hydroxyethyl)amino]-2-(hydroxymethyl)propane-1,3-diol

- PLS-DA

- partial least squares-discriminant analysis

- VIP

- variable importance in projection

- OXPHOS

- oxidative phosphorylation

- L/P

- lactate/pyruvate

- 2HG

- 2-hydroxyglutaric acid

- TCA

- tricarboxylic acid

- αKG

- α-ketoglutarate.

References

- 1. Scambler P. J. (2000) The 22q11 deletion syndromes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 2421–2426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. McDonald-McGinn D. M., Sullivan K. E. (2011) Chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Medicine 90, 1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jurata L. W., Gallagher P., Lemire A. L., Charles V., Brockman J. A., Illingworth E. L., Altar C. A. (2006) Altered expression of hippocampal dentate granule neuron genes in a mouse model of human 22q11 deletion syndrome. Schizophr. Res. 88, 251–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Karayiorgou M., Simon T. J., Gogos J. A. (2010) 22q11.2 microdeletions: linking DNA structural variation to brain dysfunction and schizophrenia. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 402–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meechan D. W., Maynard T. M., Tucker E. S., LaMantia A. S. (2011) Three phases of DiGeorge/22q11 deletion syndrome pathogenesis during brain development: patterning, proliferation, and mitochondrial functions of 22q11 genes. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 29, 283–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Antshel K. M., Aneja A., Strunge L., Peebles J., Fremont W. P., Stallone K., Abdulsabur N., Higgins A. M., Shprintzen R. J., Kates W. R. (2007) Autistic spectrum disorders in velo-cardio facial syndrome (22q11.2 deletion). J. Autism Dev. Disord. 37, 1776–1786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fine S. E., Weissman A., Gerdes M., Pinto-Martin J., Zackai E. H., McDonald-McGinn D. M., Emanuel B. S. (2005) Autism spectrum disorders and symptoms in children with molecularly confirmed 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 35, 461–470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Vorstman J. A., Morcus M. E., Duijff S. N., Klaassen P. W., Heineman-de Boer J. A., Beemer F. A., Swaab H., Kahn R. S., van Engeland H. (2006) The 22q11.2 deletion in children: high rate of autistic disorders and early onset of psychotic symptoms. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 45, 1104–1113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Maynard T. M., Meechan D. W., Dudevoir M. L., Gopalakrishna D., Peters A. Z., Heindel C. C., Sugimoto T. J., Wu Y., Lieberman J. A., Lamantia A. S. (2008) Mitochondrial localization and function of a subset of 22q11 deletion syndrome candidate genes. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 39, 439–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pejznochova M., Tesarova M., Hansikova H., Magner M., Honzik T., Vinsova K., Hajkova Z., Havlickova V., Zeman J. (2010) Mitochondrial DNA content and expression of genes involved in mtDNA transcription, regulation and maintenance during human fetal development. Mitochondrion 10, 321–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Napoli E., Wong S., Hung C., Ross-Inta C., Bomdica P., Giulivi C. (2013) Defective mitochondrial disulfide relay system, altered mitochondrial morphology and function in Huntington's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 22, 989–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim A., Chen C. H., Ursell P., Huang T. T. (2010) Genetic modifier of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase-deficient mice delays heart failure and prolongs survival. Mamm. Genome 21, 534–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baldini A. (2006) Sci. World J. 6, 1881–1887 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Washizuka S., Iwamoto K., Kakiuchi C., Bundo M., Kato T. (2009) Expression of mitochondrial complex I subunit gene NDUFV2 in the lymphoblastoid cells derived from patients with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Neurosci. Res. 63, 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Scherzer C. R., Eklund A. C., Morse L. J., Liao Z., Locascio J. J., Fefer D., Schwarzschild M. A., Schlossmacher M. G., Hauser M. A., Vance J. M., Sudarsky L. R., Standaert D. G., Growdon J. H., Jensen R. V., Gullans S. R. (2007) Molecular markers of early Parkinson's disease based on gene expression in blood. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 955–960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Glatt S. J., Tsuang M. T., Winn M., Chandler S. D., Collins M., Lopez L., Weinfeld M., Carter C., Schork N., Pierce K., Courchesne E. (2012) Blood-based gene expression signatures of infants and toddlers with autism. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 51, 934–944.e2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sullivan P. F., Fan C., Perou C. M. (2006) Evaluating the comparability of gene expression in blood and brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 141B, 261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Jasinska A. J., Service S., Choi O. W., DeYoung J., Grujic O., Kong S. Y., Jorgensen M. J., Bailey J., Breidenthal S., Fairbanks L. A., Woods R. P., Jentsch J. D., Freimer N. B. (2009) Identification of brain transcriptional variation reproduced in peripheral blood: an approach for mapping brain expression traits. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4415–4427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gardiner E., Beveridge N. J., Wu J. Q., Carr V., Scott R. J., Tooney P. A., Cairns M. J. (2012) Imprinted DLK1-DIO3 region of 14q32 defines a schizophrenia-associated miRNA signature in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Mol. Psychiatry 17, 827–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lai C. Y., Yu S. L., Hsieh M. H., Chen C. H., Chen H. Y., Wen C. C., Huang Y. H., Hsiao P. C., Hsiao C. K., Liu C. M., Yang P. C., Hwu H. G., Chen W. J. (2011) MicroRNA expression aberration as potential peripheral blood biomarkers for schizophrenia. PLoS One 6, e21635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rutter M., Bailey A., Lord C. (2003) The Social Communication Questionnaire: Manual, Western Psychological Services, Torrance, CA [Google Scholar]

- 22. Schwichtenberg A. J., Young G. S., Hutman T., Iosif A. M., Sigman M., Rogers S. J., Ozonoff S. (2013) Behavior and sleep problems in children with a family history of autism. Autism Res. 6, 169–176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Swanson J. (1995) SNAP-IV Scale. University of California Child Development Center, Irvine, CA [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hwang V. J., Maar D., Regan J., Angkustsiri K., Simon T. J., Tassone F. (2014) Mapping the deletion endpoints in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome by droplet digital PCR. BMC Med. Genet. 15, 106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giulivi C., Zhang Y. F., Omanska-Klusek A., Ross-Inta C., Wong S., Hertz-Picciotto I., Tassone F., Pessah I. N. (2010) Mitochondrial dysfunction in autism. JAMA 304, 2389–2396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Campbell A. M., Capuano A., Chan S. H. (2002) A cholesterol-binding and transporting protein from rat liver mitochondria. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1567, 123–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang X. J., Huang L. L., Su H., Chen Y. X., Huang J., He C., Li P., Yang D. Z., Wan J. B. (2014) Characterizing plasma phospholipid fatty acid profiles of polycystic ovary syndrome patients with and without insulin resistance using GC-MS and chemometrics approach. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 95, 85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. van Iersel M. P., Kelder T., Pico A. R., Hanspers K., Coort S., Conklin B. R., Evelo C. (2008) Presenting and exploring biological pathways with PathVisio. BMC Bioinformatics 9, 399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Robertson M. (2004) Reactome: clear view of a starry sky. Drug Discov. Today 9, 684–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kutmon M., van Iersel M. P., Bohler A., Kelder T., Nunes N., Pico A. R., Evelo C. T. (2015) PathVisio 3: an extendable pathway analysis toolbox. PLoS Comput. Biol. 11, e1004085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Graves J. A., Wang Y., Sims-Lucas S., Cherok E., Rothermund K., Branca M. F., Elster J., Beer-Stolz D., Van Houten B., Vockley J., Prochownik E. V. (2012) Mitochondrial structure, function and dynamics are temporally controlled by c-Myc. PLoS One 7, e37699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Li F., Wang Y., Zeller K. I., Potter J. J., Wonsey D. R., O'Donnell K. A., Kim J. W., Yustein J. T., Lee L. A., Dang C. V. (2005) Myc stimulates nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 6225–6234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Grassian A. R., Parker S. J., Davidson S. M., Divakaruni A. S., Green C. R., Zhang X., Slocum K. L., Pu M., Lin F., Vickers C., Joud-Caldwell C., Chung F., Yin H., Handly E. D., Straub C., Growney J. D., Vander Heiden M. G., Murphy A. N., Pagliarini R., Metallo C. M. (2014) IDH1 mutations alter citric acid cycle metabolism and increase dependence on oxidative mitochondrial metabolism. Cancer Res. 74, 3317–3331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wise D. R., Ward P. S., Shay J. E., Cross J. R., Gruber J. J., Sachdeva U. M., Platt J. M., DeMatteo R. G., Simon M. C., Thompson C. B. (2011) Hypoxia promotes isocitrate dehydrogenase-dependent carboxylation of α-ketoglutarate to citrate to support cell growth and viability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 19611–19616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Dang C. V. (2012) MYC on the path to cancer. Cell 149, 22–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robinson B. H. (1993) Lacticacidemia. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1182, 231–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Debray F. G., Mitchell G. A., Allard P., Robinson B. H., Hanley J. A., Lambert M. (2007) Diagnostic accuracy of blood lactate-to-pyruvate molar ratio in the differential diagnosis of congenital lactic acidosis. Clin. Chem. 53, 916–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bernier F. P., Boneh A., Dennett X., Chow C. W., Cleary M. A., Thorburn D. R. (2002) Diagnostic criteria for respiratory chain disorders in adults and children. Neurology 59, 1406–1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Linnane A. W., Marzuki S., Ozawa T., Tanaka M. (1989) Mitochondrial DNA mutations as an important contributor to ageing and degenerative diseases. Lancet 1, 642–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee H. C., Pang C. Y., Hsu H. S., Wei Y. H. (1994) Differential accumulations of 4,977 bp deletion in mitochondrial DNA of various tissues in human ageing. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1226, 37–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fukui H., Moraes C. T. (2009) Mechanisms of formation and accumulation of mitochondrial DNA deletions in aging neurons. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1028–1036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. McComsey G. A., Kang M., Ross A. C., Lebrecht D., Livingston E., Melvin A., Hitti J., Cohn S. E., Walker U. A., and AIDS Clinical Trials Group A5084 (2008) Increased mtDNA levels without change in mitochondrial enzymes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of infants born to HIV-infected mothers on antiretroviral therapy. HIV Clin. Trials 9, 126–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ross-Inta C., Omanska-Klusek A., Wong S., Barrow C., Garcia-Arocena D., Iwahashi C., Berry-Kravis E., Hagerman R. J., Hagerman P. J., Giulivi C. (2010) Evidence of mitochondrial dysfunction in fragile X-associated tremor/ataxia syndrome. Biochem. J. 429, 545–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee H. C., Yin P. H., Lu C. Y., Chi C. W., Wei Y. H. (2000) Increase of mitochondria and mitochondrial DNA in response to oxidative stress in human cells. Biochem. J. 348, 425–432 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lee H. C., Lu C. Y., Fahn H. J., Wei Y. H. (1998) Aging- and smoking-associated alteration in the relative content of mitochondrial DNA in human lung. FEBS Lett. 441, 292–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Moreno-Loshuertos R., Acín-Perez R., Fernández-Silva P., Movilla N., Pérez-Martos A., Rodriguez de Cordoba S., Gallardo M. E., Enríquez J. A. (2006) Differences in reactive oxygen species production explain the phenotypes associated with common mouse mitochondrial DNA variants. Nat. Genet. 38, 1261–1268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Napoli E., Wong S., Hertz-Picciotto I., Giulivi C. (2014) Deficits in bioenergetics and impaired immune response in granulocytes from children with autism. Pediatrics 133, e1405–e1410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Napoli E., Wong S., Giulivi C. (2013) Evidence of reactive oxygen species-mediated damage to mitochondrial DNA in children with typical autism. Mol. Autism 4, 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Napoli E., Ross-Inta C., Wong S., Hung C., Fujisawa Y., Sakaguchi D., Angelastro J., Omanska-Klusek A., Schoenfeld R., Giulivi C. (2012) Mitochondrial dysfunction in Pten haplo-insufficient mice with social deficits and repetitive behavior: interplay between Pten and p53. PLoS One 7, e42504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nota B., Struys E. A., Pop A., Jansen E. E., Fernandez Ojeda M. R., Kanhai W. A., Kranendijk M., van Dooren S. J., Bevova M. R., Sistermans E. A., Nieuwint A. W., Barth M., Ben-Omran T., Hoffmann G. F., de Lonlay P., McDonald M. T., Meberg A., Muntau A. C., Nuoffer J. M., Parini R., Read M. H., Renneberg A., Santer R., Strahleck T., van Schaftingen E., van der Knaap M. S., Jakobs C., Salomons G. S. (2013) Deficiency in SLC25A1, encoding the mitochondrial citrate carrier, causes combined d-2- and l-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 92, 627–631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chalmers R. A., Lawson A. M., Watts R. W., Tavill A. S., Kamerling J. P., Hey E., Ogilvie D. (1980) d-2-Hydroxyglutaric aciduria: case report and biochemical studies. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 3, 11–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Duran M., Kamerling J. P., Bakker H. D., van Gennip A. H., Wadman S. K. (1980) l-2-Hydroxyglutaric aciduria: an inborn error of metabolism? J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 3, 109–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rzem R., Vincent M. F., Van Schaftingen E., Veiga-da-Cunha M. (2007) l-2-Hydroxyglutaric aciduria, a defect of metabolite repair. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 30, 681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Struys E. A., Verhoeven N. M., Ten Brink H. J., Wickenhagen W. V., Gibson K. M., Jakobs C. (2005) Kinetic characterization of human hydroxyacid-oxoacid transhydrogenase: relevance to d-2-hydroxyglutaric and γ-hydroxybutyric acidurias. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 28, 921–930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Reitman Z. J., Jin G., Karoly E. D., Spasojevic I., Yang J., Kinzler K. W., He Y., Bigner D. D., Vogelstein B., Yan H. (2011) Profiling the effects of isocitrate dehydrogenase 1 and 2 mutations on the cellular metabolome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3270–3275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Tönjes M., Barbus S., Park Y. J., Wang W., Schlotter M., Lindroth A. M., Pleier S. V., Bai A. H., Karra D., Piro R. M., Felsberg J., Addington A., Lemke D., Weibrecht I., Hovestadt V., Rolli C. G., Campos B., Turcan S., Sturm D., Witt H., Chan T. A., Herold-Mende C., Kemkemer R., König R., Schmidt K., Hull W. E., Pfister S. M., Jugold M., Hutson S. M., Plass C., Okun J. G., Reifenberger G., Lichter P., Radlwimmer B. (2013) BCAT1 promotes cell proliferation through amino acid catabolism in gliomas carrying wild-type IDH1. Nat. Med. 19, 901–908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Muntau A. C., Röschinger W., Merkenschlager A., van der Knaap M. S., Jakobs C., Duran M., Hoffmann G. F., Roscher A. A. (2000) Combined d-2- and l-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria with neonatal onset encephalopathy: a third biochemical variant of 2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria? Neuropediatrics 31, 137–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Catalina-Rodriguez O., Kolukula V. K., Tomita Y., Preet A., Palmieri F., Wellstein A., Byers S., Giaccia A. J., Glasgow E., Albanese C., Avantaggiati M. L. (2012) The mitochondrial citrate transporter, CIC, is essential for mitochondrial homeostasis. Oncotarget 3, 1220–1235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Hulsen T., de Vlieg J., Alkema W. (2008) BioVenn: a web application for the comparison and visualization of biological lists using area-proportional Venn diagrams. BMC Genomics 9, 488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chowdhury R., Yeoh K. K., Tian Y. M., Hillringhaus L., Bagg E. A., Rose N. R., Leung I. K., Li X. S., Woon E. C., Yang M., McDonough M. A., King O. N., Clifton I. J., Klose R. J., Claridge T. D., Ratcliffe P. J., Schofield C. J., Kawamura A. (2011) The oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate inhibits histone lysine demethylases. EMBO Rep. 12, 463–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Xu W., Yang H., Liu Y., Yang Y., Wang P., Kim S. H., Ito S., Yang C., Wang P., Xiao M. T., Liu L. X., Jiang W. Q., Liu J., Zhang J. Y., Wang B., Frye S., Zhang Y., Xu Y. H., Lei Q. Y., Guan K. L., Zhao S. M., Xiong Y. (2011) Oncometabolite 2-hydroxyglutarate is a competitive inhibitor of α-ketoglutarate-dependent dioxygenases. Cancer Cell 19, 17–30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lu C., Ward P. S., Kapoor G. S., Rohle D., Turcan S., Abdel-Wahab O., Edwards C. R., Khanin R., Figueroa M. E., Melnick A., Wellen K. E., O'Rourke D. M., Berger S. L., Chan T. A., Levine R. L., Mellinghoff I. K., Thompson C. B. (2012) IDH mutation impairs histone demethylation and results in a block to cell differentiation. Nature 483, 474–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Lopez-Bigas N., Kisiel T. A., Dewaal D. C., Holmes K. B., Volkert T. L., Gupta S., Love J., Murray H. L., Young R. A., Benevolenskaya E. V. (2008) Genome-wide analysis of the H3K4 histone demethylase RBP2 reveals a transcriptional program controlling differentiation. Mol. Cell 31, 520–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sasaki M., Knobbe C. B., Itsumi M., Elia A. J., Harris I. S., Chio I. I., Cairns R. A., McCracken S., Wakeham A., Haight J., Ten A. Y., Snow B., Ueda T., Inoue S., Yamamoto K., Ko M., Rao A., Yen K. E., Su S. M., Mak T. W. (2012) d-2-Hydroxyglutarate produced by mutant IDH1 perturbs collagen maturation and basement membrane function. Genes Dev. 26, 2038–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Casazza J. P., Song B. J., Veech R. L. (1990) Short chain diol metabolism in human disease states. Trends Biochem. Sci. 15, 26–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kowaloff E. M., Granger A. S., Phang J. M. (1976) Alterations in proline metabolic enzymes with mammalian development. Metabolism 25, 1087–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Phang J. M., Valle D., Kowaloff E. M. (1975) Proline biosynthesis and degradation in mammalian cells and tissue. Ann. Clin. Lab. Sci. 5, 298–302 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Liu Y., Borchert G. L., Donald S. P., Diwan B. A., Anver M., Phang J. M. (2009) Proline oxidase functions as a mitochondrial tumor suppressor in human cancers. Cancer Res. 69, 6414–6422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bender H.-U., Almashanu S., Steel G., Hu C.-A., Lin W.-W., Willis A., Pulver A., Valle D. (2005) Functional consequences of PRODH missense mutations. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 76, 409–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Raimondi I., Ciribilli Y., Monti P., Bisio A., Pollegioni L., Fronza G., Inga A., Campomenosi P. (2013) p53 family members modulate the expression of PRODH, but not PRODH2, via intronic p53 response elements. PLoS One 8, e69152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. McDonald-McGinn D. M., Reilly A., Wallgren-Pettersson C., Hoyme H. E., Yang S. P., Adam M. P., Zackai E. H., Sullivan K. E. (2006) Malignancy in chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (DiGeorge syndrome/velocardiofacial syndrome). Am. J. Med. Genet. A 140, 906–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Hanschmann E. M., Lönn M. E., Schütte L. D., Funke M., Godoy J. R., Eitner S., Hudemann C., Lillig C. H. (2010) Both thioredoxin 2 and glutaredoxin 2 contribute to the reduction of the mitochondrial 2-Cys peroxiredoxin Prx3. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 40699–40705 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Dean R. T., Fu S., Stocker R., Davies M. J. (1997) Biochemistry and pathology of radical-mediated protein oxidation. Biochem. J. 324, 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Mrochek J. E., Rainey W. T. (1972) Identification and biochemical significance of substituted furans in human urine. Clin. Chem. 18, 821–828 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Munekata M., Tamura G. (1981) The selective inhibitors against SV40-transfomed cells. 2. Anti-tumor activity of 5-hydroxymethyl-2-furoic acid. Agric. Biol. Chem. 45, 2149–2150 [Google Scholar]

- 76. Sellier C., Hwang V. J., Dandekar R., Durbin-Johnson B., Charlet-Berguerand N., Ander B. P., Sharp F. R., Angkustsiri K., Simon T. J., Tassone F. (2014) Decreased DGCR8 expression and miRNA dysregulation in individuals with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. PLoS One 9, e103884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Mühlhausen C., Salomons G. S., Lukacs Z., Struys E. A., van der Knaap M. S., Ullrich K., Santer R. (2014) Combined D2-/L2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria (SLC25A1 deficiency): clinical course and effects of citrate treatment. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 37, 775–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Mycielska M. E., Patel A., Rizaner N., Mazurek M. P., Keun H., Patel A., Ganapathy V., Djamgoz M. B. (2009) Citrate transport and metabolism in mammalian cells: prostate epithelial cells and prostate cancer. Bioessays 31, 10–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Latini A., Da Silva C. G., Ferreira G. C., Schuck P. F., Scussiato K., Sarkis J. J., Dutra Filho C. S., Wyse A. T. S., Wannmacher C. M. D., Wajner M. (2005) Mitochondrial energy metabolism is markedly impaired by d-2-hydroxyglutaric acid in rat tissues. Mol. Gen. Metab. 86, 188–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. da Silva C. G., Ribeiro C. A., Leipnitz G., Dutra-Filho C. S., Wyse A. T., Wannmacher C. M., Sarkis J. J., Jakobs C., Wajner M. (2002) Inhibition of cytochrome c oxidase activity in rat cerebral cortex and human skeletal muscle by d-2-hydroxyglutaric acid in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta 1586, 81–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Wajne M., Vargas C. R., Funayama C., Fernandez A., Elias M. L. C., Goodman S. I., Jakobs C., van der Knaap M. S. (2002) d-2-Hydroxyglutaric aciduria in a patient with a severe clinical phenotype and unusual MRI findings. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 25, 28–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kölker S., Pawlak V., Ahlemeyer B., Okun J. G., Hörster F., Mayatepek E., Krieglstein J., Hoffmann G. F., Köhr G. (2002) NMDA receptor activation and respiratory chain complex V inhibition contribute to neurodegeneration in d-2-hydroxyglutaric aciduria. Eur. J. Neurosci. 16, 21–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]