Background: PME and PMEI isoforms are co-expressed in Arabidopsis. Their biochemical interaction is yet to be characterized.

Results: The processive activity of AtPME3 is regulated by AtPMEI7 in a pH-dependent manner in vitro.

Conclusion: AtPMEI7 is a key component of the regulation of AtPME3 activity in planta.

Significance: The tuning of AtPME3 activity by AtPMEI7 brings insights into the control of homogalacturonan methylesterification in plant cell walls.

Keywords: homology modeling, plant biochemistry, plant cell wall, protein expression, protein-protein interaction, degree of blockiness, gel diffusion assay, microscale thermophoresis, pectin methylesterase (PME), pectin methylesterase inhibitor (PMEI)

Abstract

Pectin methylesterases (PMEs) catalyze the demethylesterification of homogalacturonan domains of pectin in plant cell walls and are regulated by endogenous pectin methylesterase inhibitors (PMEIs). In Arabidopsis dark-grown hypocotyls, one PME (AtPME3) and one PMEI (AtPMEI7) were identified as potential interacting proteins. Using RT-quantitative PCR analysis and gene promoter::GUS fusions, we first showed that AtPME3 and AtPMEI7 genes had overlapping patterns of expression in etiolated hypocotyls. The two proteins were identified in hypocotyl cell wall extracts by proteomics. To investigate the potential interaction between AtPME3 and AtPMEI7, both proteins were expressed in a heterologous system and purified by affinity chromatography. The activity of recombinant AtPME3 was characterized on homogalacturonans (HGs) with distinct degrees/patterns of methylesterification. AtPME3 showed the highest activity at pH 7.5 on HG substrates with a degree of methylesterification between 60 and 80% and a random distribution of methyl esters. On the best HG substrate, AtPME3 generates long non-methylesterified stretches and leaves short highly methylesterified zones, indicating that it acts as a processive enzyme. The recombinant AtPMEI7 and AtPME3 interaction reduces the level of demethylesterification of the HG substrate but does not inhibit the processivity of the enzyme. These data suggest that the AtPME3·AtPMEI7 complex is not covalently linked and could, depending on the pH, be alternately formed and dissociated. Docking analysis indicated that the inhibition of AtPME3 could occur via the interaction of AtPMEI7 with a PME ligand-binding cleft structure. All of these data indicate that AtPME3 and AtPMEI7 could be partners involved in the fine tuning of HG methylesterification during plant development.

Introduction

The primary cell wall of dicots consists of cellulose primarily cross-linked by xyloglucans and embedded in a complex matrix of pectic polysaccharides (1). Pectins are important structural polysaccharides in cell walls, representing up to one-third of primary wall dry mass. They are complex polysaccharides, rich in galacturonic acids (GalA),4 which comprise three main domains: homogalacturonan (HG), rhamnogalacturonan-I, and minor amounts of rhamnogalacturonan-II (2). HG is composed of α-1,4-linked-d-galacturonic acid units. It can be methylesterified at the C-6 carboxyl and/or acetylated at the O-2 or O-3 residues (3). HG is synthesized from nucleotide sugars in the Golgi apparatus and then secreted as a fully methylesterified (up to 80%) form into the cell wall (4), where it can be de-esterified by cell wall enzymes, pectin methylesterases (PMEs; EC 3.1.1.11).

PMEs are encoded by a large multigene family of 66 members in Arabidopsis (5). Based on their structure, plant PMEs have been classified into two groups. Both group 1 and group 2 PMEs possess a conserved PME domain (Pfam 01095). Group 2 PMEs contain an N-terminal extension called the PRO region, which shares similarity with the PME inhibitor domain (Pfam 04043 (5)). It has been shown that the PRO region mediates the retention of unprocessed group 2 PMEs in the Golgi apparatus, thus regulating PME enzyme activity through a post-translational mechanism (6). PME isoforms are either constitutively or differentially expressed in plant tissues at specific developmental stages or in response to biotic and abiotic stresses (7–11).

The mechanism of action of PMEs consists of the hydrolysis of the methyl ester bond at the C-6 position of GalA of HG. This releases methanol and provides a free carboxyl group on the pectin backbone, thus lowering the degree of methylesterification (DM). As a result, the gelling properties and calcium reactivity of the pectic polymer are modified (12, 13). The enzyme activity of PMEs is regulated by pH (14–17). It is generally assumed that PMEs with an alkaline pI remove methyl ester in a blockwise manner, leading to the formation of demethylated stretches (14, 18, 19), whereas acidic isoform activity results in a random-like distribution of the non-methylated GalA residues (20). The activity of PMEs is also regulated by PMEIs (21). In Arabidopsis, 76 genes have been annotated as encoding putative PMEIs, and some of them have been characterized at a biochemical (22, 23) or functional level (24–27). PMEI inhibits plant PME through interaction in a complex of 1:1 stoichiometry, in which PMEI covers the pectin-binding cleft of PME and hides its putative catalytic site, thereby impairing access to the substrate (28–30).

Considering the sizes of the PME and PMEI gene families, the determination of the specificity of the interactions between the proteins is a key issue for understanding the fine tuning of pectin methylesterification and its effects on plant development and defense mechanisms. In this report, we have identified AtPME3 (At3g14310) and AtPMEI7 (At4g25260) as being two of the major PME and PMEI isoforms expressed in Arabidopsis dark-grown hypocotyls, both at the transcript and protein levels. This co-expression suggested that AtPME3 (thereafter PME3) and AtPMEI7 (thereafter PMEI7) could interact in vivo. Both proteins were overexpressed in heterologous systems and purified by affinity chromatography. We showed that purified PME3 has an optimal enzyme activity at slightly alkaline pH and exhibits strong substrate specificity toward HG with a DM between 60 and 80% and a random distribution of methyl esters. The inhibition of recombinant PME3 by purified PMEI7 was shown to be regulated by pH. Using structural modeling, the docking of PMEI7 into PME3 revealed a strong conservation of the interaction. Altogether, this study brings new insights into the interactions between PMEs and PMEIs and provides new tools for the identification of PME-PMEI pairs in vitro and in muro.

Experimental Procedures

Plant Material and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis wild-type plants or gene promoter::GUS lines, cv. Columbia (Col-0), were grown in a phytotronic chamber on plates (16-h photoperiod at 120 μmol·m−2·s−1 and 22 °C) or on soil (16 h photoperiod at 100 μmol·m−2·s−1 and 23 °C/19 °C day/night) as described (25, 31). Transfer to light is referred to as t = 0 for all experiments. Hypocotyls were harvested at various time points (24, 48, 72, and 96 h) for determination of promoter activities and RNA extraction. 4-day-old dark-grown hypocotyls, 10-day-old roots and 3-week-old leaves were harvested and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. They were subsequently ground to a fine powder in a ball mill and kept frozen (−80 °C) until processing.

RNA Extraction and Gene Expression Analysis by RT-Quantitative PCR

RNAs were extracted from 200 mg of dark-grown hypocotyls as described (32). DNA was removed using the Turbo DNA-freeTM kit (Ambion, catalog no. AM1907, Austin, TX), according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNA synthesis was performed using 5 μg of treated RNAs, 50 μm oligo(dT)20, and the RevertAid H Minus reverse transcriptase (Fisher) using the manufacturer's protocol. RT-quantitative PCR was performed on 1:20 diluted cDNA using the FastStart SYBR Green Master (catalog no. 04673484001, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and the LightCycler® 480 real-time PCR system (Roche Diagnostics). Oligonucleotide primers used to amplify PME3 and PMEI7 transcripts as well as the reference gene and CLA, e.g. clathrine, are listed in Table 1. Reference genes were used as internal controls to calculate the relative expression of genes of interest (33).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of oligonucleotide primers used for GUS constructs, constructs designed for the heterologous expression of proteins, and quantitative RT-PCR analyses

| Primer name | Sequence | Amplicon size gDNA/cDNA |

|---|---|---|

| bp | ||

| GUS construction primers | ||

| pPMEI7-F | 5′-ACTGGTTCTTCCCAAAAGGTA-3′ | 643 |

| pPMEI7-R | 5′-TTTAGATTTAAAACACAAATGGGTTATTTTAG-3′ | |

| Heterologous expression construction primers | ||

| PME3-for | 5′-ATTCTGCCCGGGATGGCACCATCAATGAAAG-3′ | 1779 |

| PME3-rev | 5′-AAAACAATAAGCGGCCGCTAAGACCGAGCGAGAAG-3′ | |

| PMEI7-for | 5′-GAGGGATCCAGAAACCTTGAAGAGGAATCAAG-3′ | 600 |

| PMEI7-rev | 5′-GAGGTCGACGAAATGATTTCAATGCTTGGAAGC-3′ | |

| Quantitative PCR primers | ||

| PME3-qF | 5′-TCAAATGTCTCATCGCCGGAACC-3′ | 80 |

| PME3-qR | 5′-AGCGTGGATGTCACAGTCTTGG-3′ | |

| PMEI7-qF | 5′-TTGTGAGTGTTGCGGAAGAG-3′ | 97 |

| PMEI7-qR | 5′-CCCAAAGACTAAACCCCTTTG-3′ | |

| CLA-F | 5′-GTTTGGGAGAAGAGCGGTTA-3′ | 114 |

| CLA-R | 5′-CTGATGTCACTGAACCTGAACTG-3′ | |

| TIP41-F | 5′-GCTCATCGGTACGCTCTTTT-3′ | 117 |

| TIP41-R | 5′-TCCATCAGTCAGAGGCTTCC-3′ | |

Generation of Gene Promoter::GUS Lines and GUS Activity Assay

The construction and selection of the promPME3:GUS, e.g. β-glucuronidase line has been previously described (34). To generate the promPMEI7:GUS construct, a 643-base pair region upstream of the ATG codon (whole region from the end of the closest gene) was reamplified from the SAP promoterome collection (35) using the oligonucleotide primers listed in Table 1. The PCR product was inserted into the Gateway®-compatible vector pDONR207 before cloning into the destination vector pGWB3 (36). The plasmid was transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain C58C1 (pMP90), and Col-0 plants were transformed by the floral dip method (37). Transformants were selected on kanamycin at 80 μg·ml−1. GUS assays and image acquisitions were as described (31).

Cloning of PME3 and PMEI7 Coding Sequences into Expression Plasmids

The coding sequence of PME3 was cloned into the pRTL2-GUS vector (38). Two adaptors, 5′-CATGGCACCCGGGGCGGCCGCCACCACCACCACCACCACTGAG-3′ (forward) and 5′-GATCCTCAGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGTGGCGGCCGCCCCGGGTGC-3′ (reverse), were synthesized and inserted into pRTL2, replacing GUS and producing pRTL2Adapt. These adaptors contain SmaI and NotI restriction sites, a sequence encoding a His6 tag in frame with a stop codon (TGA). The PME3 coding sequence was PCR-amplified from the RIKEN clone pda01596 using the Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega, Madison, WI) and oligonucleotide primers containing SmaI and NotI sites (Table 1). The 1779-bp PME3 coding region was ligated downstream of tobacco etch virus (TEV) leader sequence involved in translational enhancement into the pRTL2Adapt vector. That vector contains a 35S transcriptional terminator/polyadenylation sequence (T35S). This generates a fusion protein, TEV-PME3-His6, suitable for nickel affinity purification. A HindIII fragment containing 2CaMV35S-TEV-PME3-His6-T35S in pRTL2 Adapt was inserted into the HindIII site of a binary vector pCAMBIA1300, generating pCambia PME3. The A. tumefaciens LBA4404 strain containing the binary pCambia PME3 vector was used to generate transgenic Nicotiana tabacum plants (var. PBD6). Hygromycin-resistant T1 transformants were selected, and seeds from T2 lines were sown. Leaves of 3-month-old tobacco plants were used for PME3-His6 purification.

The PMEI7 coding sequence without the signal peptide was PCR-amplified from the RIKEN clone pda05287 using oligonucleotide primers (Table 1) and Pfu DNA polymerase (Promega). The amplified DNA was digested with BamHI and SalI and inserted into the same sites of pQE30 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) downstream of a His6, thus generating a fusion protein, His6-PMEI7. Escherichia coli strain Rosetta-gamiTM was subsequently transformed.

Purification of Recombinant AtPME3 and AtPMEI7

Recombinant PME3 (PME3-His6) was purified from N. tabacum leaves according to a method adapted from (39). Frozen leaf powder (1 g) was homogenized in 3 ml of 50 mm NaH2PO4 containing 2 m NaCl (pH 7) and incubated for 30 min at 4 °C with gentle shaking. The protein extract was centrifuged at 27,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. After supernatant recovery, a second extraction was carried out on the pellet in the same conditions. The supernatants were combined and diluted 6.6-fold in a 50 mm NaH2PO4 buffer (pH 8) containing 40 mm imidazole. The supernatant was loaded onto a nickel affinity column (HisTrap FF, GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK) and washed with 10 column volumes of 40 mm imidazole in 50 mm NaH2PO4 buffer, 500 mm NaCl (pH 8). The recombinant protein was eluted from the affinity resin with 500 mm imidazole in NaH2PO4 50 mm buffer, 500 mm NaCl (pH 8). The purified protein was loaded onto a spin column (Microcon YM-10, Merck Millipore, Tullagreen Carrigtwohill, Ireland) and desalted with 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5). The tube was centrifuged at 3000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C, and the elution volume was adjusted to 200 μl.

Bacteria carrying the recombinant PMEI7 (PMEI7-His6) construct were grown in LB medium with 100 μg/ml ampicillin at 37 °C to reach an A600 of 0.6. Expression of the fusion protein was induced by the addition of 0.2 mm isopropylthio-β-galactoside, and subsequent growth was at room temperature for 17 h. The bacterial pellet was harvested by centrifugation. Extraction of proteins was performed by resuspension/incubation of this pellet in lysozyme solution, followed by sonication. Lysate was collected by centrifugation and used to perform PMEI7-His6 purification with Ni-NTA-agarose resin (Qiagen, catalog no. 30210). Protein concentration was determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay dye reagent concentrate. Proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using a 12% acrylamide/bis-acrylamide gel and stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250.

MS Analysis

MALDI-TOF MS analyses were performed as described (40), whereas nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS analyses were performed as described (31).

Homogalacturonan Models

Three series of HGs with a large range of DM and patterns of methylesterification were prepared by saponification (B-series) and/or plant pectin methylesterase (Sigma P5400; 194 units/mg) treatments (BP- and -P series) as described (41). The HG models (20 mg/ml) were dissolved in 50 mm phosphate buffer, at the appropriate pH of the enzyme activity assay overnight at room temperature.

Pectin Methylesterase Activity Assay

The purified enzyme (1–2 μg/5 μl) was incubated in 50 mm NaH2PO4 (80 μl) at pH 4.0, 6.0, or 7.5 with 5 μl of HG substrate (20 mg/ml) for 30 min at 30 °C. At the end of the reaction, the enzyme was inactivated and freeze-dried to evaporate the methanol released. Methanol ester-linked to HG was released after saponification (27) and was assessed by quantifying base-released methanol using N-methylbenzothiazolinone-2-hydrazone (42). PME activity was determined with reference to a methanol standard curve (20 μg/ml) in a range of 0–20 μg/ml and expressed in nmol of methanol·min−1·μg of proteins−1.

To study the inhibition of PME3-His6 activity by PMEI7-His6, PME3 (2 μg/5 μl) was preincubated for 30 min at 30 °C with PMEI7 (5 μl, 1–8 μg) in 20 μl of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 or 6.0. The HG substrate (5 μl, 20 mg/ml) and 65 μl of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.5 or 6.0, were then added to the reaction and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped at 100 °C for 10 min, and the PME3 enzyme activity was assayed as described above.

Kinetic Assay

The apparent Km and Vmax were determined by measuring PME activity based on methanol oxidation to formaldehyde via alcohol oxidase as described (43). Purified PME3-His6 (0.03–0.05 μg/2 μl) was incubated with HG substrates (1 mg/ml) in a methoxy range of 0.0725–1 mm, 125 μl of alcohol oxidase (1 unit/ml), and 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, to give a final volume of 250 μl. The reaction was incubated in a water bath at 30 °C for 15 min. A solution (250 μl) containing 20 mm pentane-2,4-dione, 2 m ammonium acetate, and 50 mm acetic acid was added to the sample. After 15 min at 65 °C, absorbance was read at 412 nm. PME activity was determined with reference to a methanol standard curve in a range of 0–20 mm. A standard curve was performed for each HG substrate. PME activity was expressed in nmol of methanol·min−1·μg of proteins−1.

Inhibition Test of PME Activity with PMEI7 by a Gel Diffusion Assay

PME activity was quantified by a gel diffusion assay (44) with some modifications (45). The standard curve was obtained using commercial orange PME (Sigma, catalog no. P5400) to quantify the activity based on red stain diameters (46). Protein extraction from Arabidopsis material was performed according to (39), starting from a fine powder of frozen material mixed with 50 mm sodium phosphate dibasic buffer, containing 20 mm citric acid, 1 m NaCl, and 0.01% Tween 20, at pH 7.0, for 1 h at 4 °C with shaking. The extracts were clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C. Protein concentrations were measured by the Bradford method (47). To load identical activities (milliunits or nmol/min) in each well, PME activities were measured by colorimetric assay using an alcohol oxidase-coupled microassay (48). A volume of 5 μl containing 1 milliunit of PME3-His6 (2 μg) or 3 milliunits of total PME activity from Arabidopsis protein extracts was preincubated for 30 or 60 min at room temperature with a volume of 5 μl containing various amounts of PMEI7-His6. Then, the reaction mixture was loaded onto each well in gel diffusion at various pH values and incubated for 16 h at 37 °C. Diameters of the halos were measured using ImageJ software.

Microscale Thermophoresis (MST) Binding Assay

Molecular interaction between purified PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 was studied by an MST approach, as described previously (49, 50). In all experiments, PME3-His6 was labeled with the Dye NT-495 NHS from the Monolith NT.115TM protein labeling kit Blue NHS Amine Reactive (NanoTemper, (Munich, Germany), catalog no. L003) and resuspended in a 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, buffer. For PMEI7-His6, a PD SpinTrap G-25 column (GE Healthcare, catalog no. 28-9180-04) was used, following the manufacturer's instructions, to change the protein buffer to a 50 mm sodium phosphate buffer containing 300 mm NaCl at the appropriate pH (i.e. pH 5, 6, or 7.5). For assays, a constant concentration of labeled PME3-His6 (333 nm) was titrated with increasing concentrations of non-labeled PMEI7-His6 at the different pH values. Mixtures of recombinant PME3 and PMEI7 were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and then loaded into Monolith NT.115TM series capillaries Standard Treated (NanoTemper, catalog no. K002). Thermophoresis analyses were then performed with Monolith NT.115 (NanoTemper) with 90% of LED power and 40% of MST power for fluorescence acquisitions. Data were treated with NT analysis software (NanoTemper) to determine dissociation constants (Kd).

Enzymatic Fingerprinting Assay

PME3-His6 (2 μg) was preincubated in 20 μl of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, for 30 min at 30 °C with or without PMEI7-His6 (8 μg). The HG substrate (150 μg) in 5 μl of 50 mm phosphate buffer, pH 6.0, was added to the reaction (100-μl final volume) and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped at 100 °C for 10 min. A sample containing only the substrate was also assayed. The samples were loaded onto a spin column (Microcon YM-10, Millipore), desalted with water, and then freeze-dried. The samples were dissolved in water (700 μl). The degree of methylesterification and the uronic acid residues were quantified as described (41). The samples were hydrolyzed by pectin lyase or endopolygalacturonase II, and the degree of blockiness was determined as described (51).

Three-dimensional Homology Modeling and Protein Docking

The structural homology modeling of PME3 and PMEI7 was performed as described (31). The best templates suitable for the proteins were chosen based on sequence identity, secondary structure comparison, and good query coverage. The structure of carrot PME (PDB code 1GQ8 (52)) was used to construct a homology model of PME3 because it has the highest sequence identity with PME3 (78%). Similarly, the model of PMEI7 was built by using kiwi PMEI (PDB code 1XG2 (29)) as a structural template with a sequence identity of 17–20%. Modeling, visualization, labeling, and accuracy of the protein structure were carried out as described (31). Important putative amino acid residues were labeled according to the literature (29, 52–54). Interaction between PME3 and PMEI7 was evaluated by docking analysis using LZerD based on shape complementarity (55, 56). Model number 8 from the 15 best models was selected based on the literature data and the number of contacting residues.

Statistical Analysis

Normality of data and homogeneity of variances were analyzed using Shapiro-Wilk and Levene tests, respectively. When these hypotheses could not be verified, log or square root transformations were carried out to check normality and homogeneity of variances and perform parametric tests. ANOVA was used, followed by multiple comparisons of means with Tukey's range test to determine significant differences between several data groups. In this case, the different letters indicate data sets significantly different for a p value <0.05. For mean comparisons between two samples, Student's t test was used to determine significant differences, which are highly significant (p < 0.001; ***), significant (p < 0.1; **) and moderately significant (p < 0.05; *). For quantification of degree of methylesterification, despite log or square root transformations, normality and homogeneity of variance were not verified. Consequently, a nonparametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test was performed to determine significant differences between two sample conditions, which are highly significant for p < 0.001 (***), significant for p < 0.1 (**), and moderately significant for p < 0.05 (*).

Results

PME3 and PMEI7 Are Expressed in Arabidopsis Dark-grown Hypocotyls at the Transcript and Protein Levels

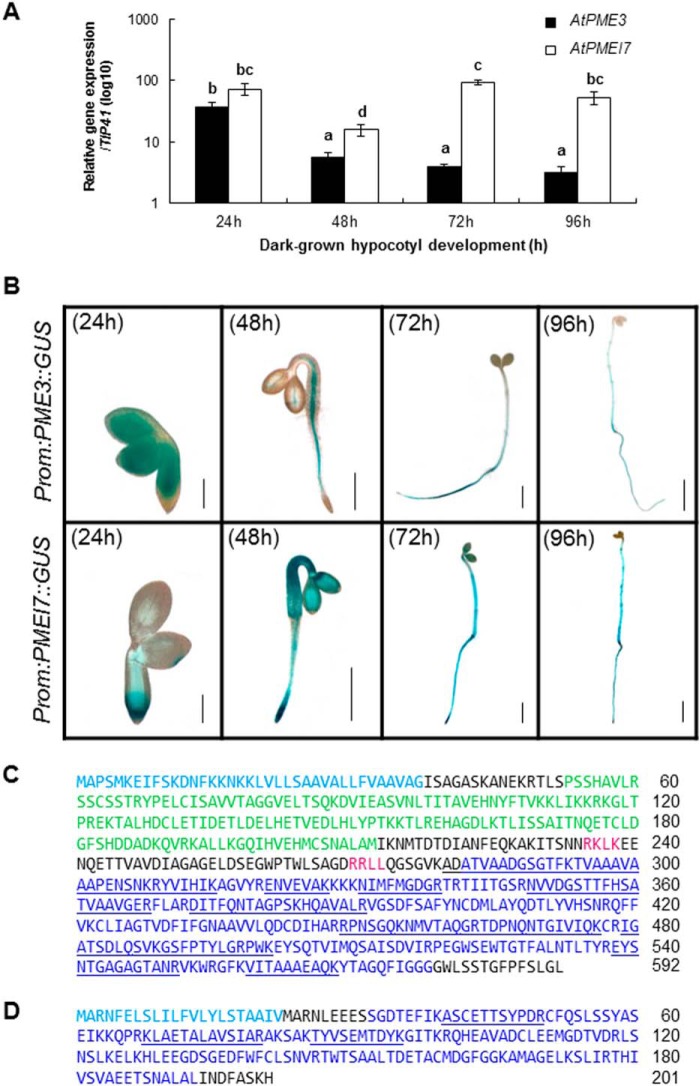

In order to determine the expression of PME3 and PMEI7 in dark-grown hypocotyls, their transcript levels were assessed using RT-quantitative PCR in dissected hypocotyls harvested at 24, 48, 72, and 96 h postgermination (Fig. 1A). The transcripts of both genes were present in relatively high abundance at 24 h but subsequently displayed distinct patterns of accumulation. The relative abundance of PME3 transcripts decreased over the course of hypocotyl development up to 96 h postgermination. In contrast, after a transient decrease at 48 h, the quantity of PMEI7 transcripts remained at a steady-state level up to 96 h. In order to identify cells in which PME3 and PMEI7 were transcribed, the activity of their promoters was followed in dark-grown hypocotyls of transgenic Arabidopsis plants carrying gene promoter::GUS constructs. Both of them were particularly active up to 96 h postgermination, with overlapping localization, in particular from 48 h onward (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

PME3 and PMEI7 are expressed in dark-grown hypocotyls at transcriptomic and proteomic levels. A, level of transcripts of PME3 (■) and PMEI7 (□) in dark-grown hypocotyls from 24 to 96 h postgermination determined by RT-quantitative PCR analysis. The relative level of accumulation was measured using the reference genes TIP41 and CLA, but only the results obtained with TIP41 are shown. Relative expression is shown in means of log10 ± S.E. (error bars) of four replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001. B, activity of the promoters of PME3 and PMEI7, revealed by GUS staining of transgenic dark-grown hypocotyls up to 96 h postgermination. Black scale bars, 0.2 mm (24 h), 0.5 mm (48 h), 1 mm (72 h), and 2 mm (96 h). C, identification of PME3 protein in cell wall protein extracts of 5-day-old dark-grown hypocotyls. The PMEI domain is represented in green, the PME domain is shown in dark blue, and putative basic processing motifs (RKLK and RRLL) are shown in red. D, identification of PMEI7 protein in cell wall protein extracts of 5-day-old dark-grown hypocotyls. The inhibitor domain is indicated in dark blue. For both proteins, signal peptide is indicated by a sky blue-colored sequence, and peptides identified by MALDI-TOF MS analysis are underlined.

In addition, cell wall proteomics analysis of dark-grown hypocotyls allowed identification of six PMEs and three PMEIs (40). Although MALDI-TOF MS does not provide precise quantification of proteins, the number of peptides related to each protein present in the extract showed that At3g43270 (PME32) and At3g14310 (PME3) were identified with the highest number of peptides (67 and 45, respectively, after 5 days). Some other PMEs were identified as well but with lower amounts of peptides: At1g11580 (29 peptides), At1g53830 (28 peptides), At4g33220 (25 peptides), and At5g53370 (9 peptides). In a similar way, a number of PMEIs were identified in cell walls from 5-day-old etiolated hypocotyls, including At4g25260 (PMEI7), At5g46940, and At5g46960, with four, three, and four peptides, respectively (40). The position of the different peptides allowing the identification of PME3 and PMEI7 is reported in Fig. 1, C and D. On the basis of their co-expression at the transcript and protein levels in dark-grown hypocotyls, PME3 and PMEI7 could, among other putative pairs, potentially interact in the cell wall and were thus chosen as candidates to investigate PME-PMEI interactions in vitro. For this purpose, the two proteins were expressed as recombinant proteins in heterologous systems and purified.

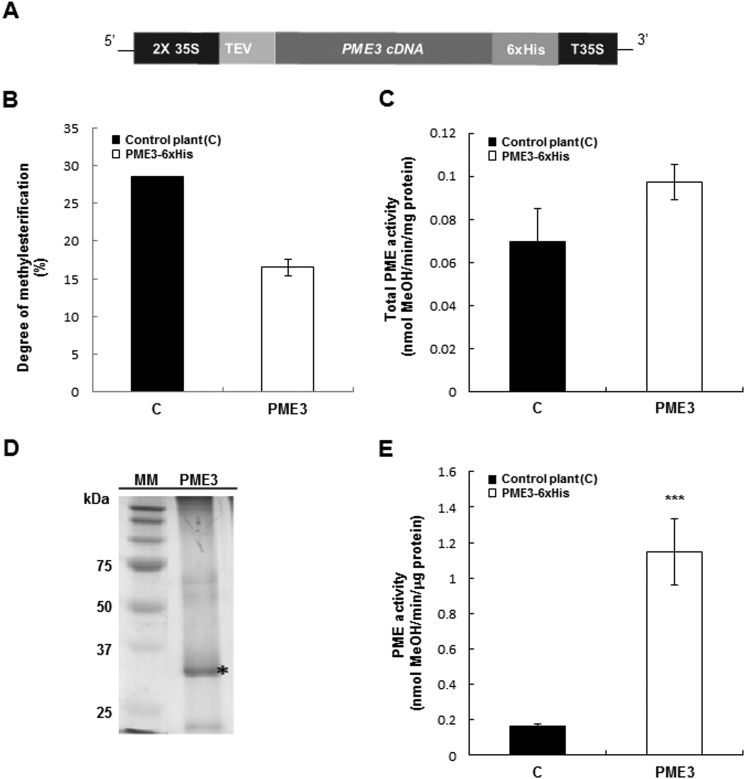

Recombinant PME3 Is Properly Processed in an Active Form in Transgenic N. tabacum Plants

Transgenic plants expressing PME3-His6 under the control of a double 35S promoter were generated using A. tumefaciens-mediated transformation (Fig. 2A). No obvious phenotype was observed in these plants during their development. The leaves of the selected transgenic line showed a slight increase in total PME activity and a lower DM (5%) compared with wild-type plants, albeit not significant (Fig. 2, B and C). The presence of the His tag enabled a single-step purification of PME3-His6 from a cell wall-enriched extract using nickel affinity chromatography. Following SDS-PAGE analysis and Coomassie Blue staining, a band at a molecular mass of ±34 kDa was clearly visible (Fig. 2D). The band was excised from the Coomassie Blue-stained gel, and the presence of recombinant processed PME3-His6 was confirmed by proteomic analysis. 17 peptides were found, covering 52% of the mature protein (data not shown). This unequivocally shows that PME3-His6 was properly processed in transgenic N. tabacum plants. The purified fraction isolated from the PME3-His6-overexpressing line showed a significant increase in PME activity compared with the control when pectins with DM of 90% were used (Fig. 2E).

FIGURE 2.

PME3-His6 is processed properly and is active in transgenic N. tabacum plants. A, transgenic N. tabacum plants overexpressing PME3-His6 were generated. Expression of PME3 under the control of a double CaMV 35S promoter and a 35S transcriptional terminator/polyadenylation sequence (T35S) was carried out using a binary vector. The PME coding region was fused to the TEV sequence for enhanced transcription and to the His6 tag for affinity purification. B, DM in control plants (■) and transgenic tobacco plants overexpressing PME3-His6 (□). DM was calculated as described (51). Data represent mean values ± S.E. (error bars) from three replicates. No significant differences were shown with non-parametric Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney test. C, PME activity from total protein extract of control plants (■) and the PME3-His6-overexpressing line (□). Data represent means ± S.E. from three independent samples. According to Student's t test, no significant differences are shown. D, Ni-NTA-purified PME3-His6 analysis by SDS-PAGE. MM, molecular mass marker. PME3, Purified PME3-His6 (*). E, PME activity from Ni-NTA retained the fraction of control plants (■) and a representative PME3-His6-overexpressing line (□). For determination of PME activity, assays were performed according to the method adapted from Ref. 43. Data represent mean values ± S.E. from three independent samples. Significant differences were determined with Student's t test (***, p < 0.001).

PME3-His6 Has an Optimal Enzyme Activity at Slightly Alkaline pH and a Substrate Specificity toward HG with a DM of 60–80% and a Random Distribution of Methyl Esters

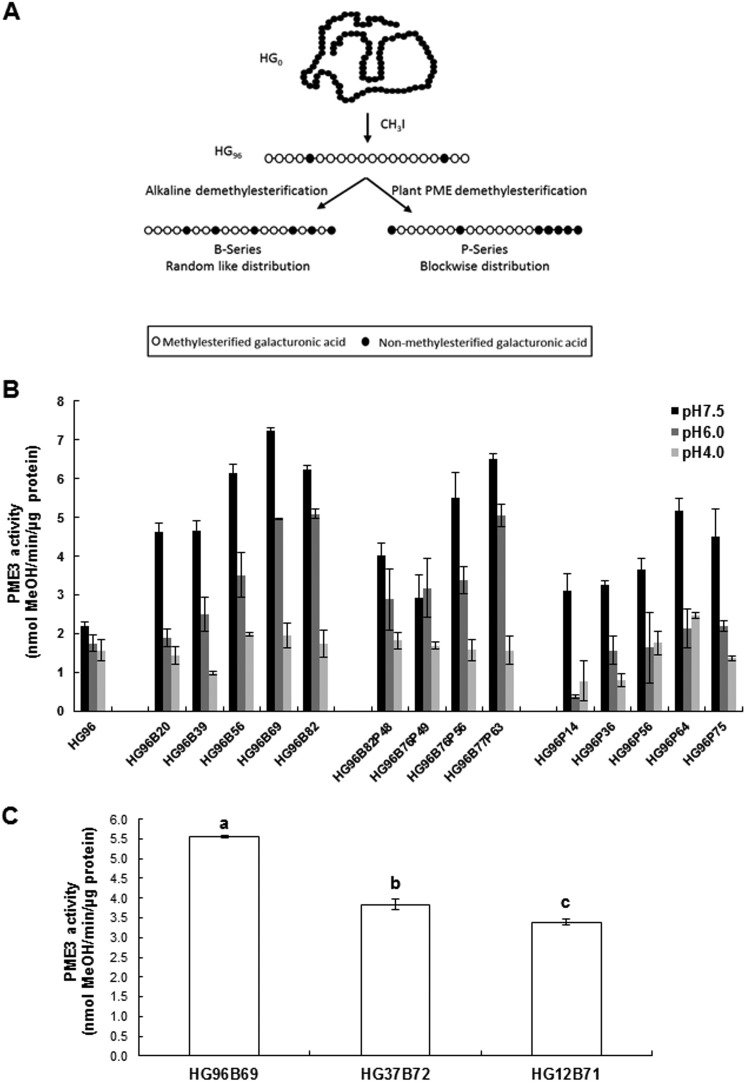

To characterize further PME3-His6 substrate specificity and optimal pH activity, three series of HG models and three distinct pH values (pH 7.5, 6.0, and 4.0) were assayed (Fig. 3A). The optimal enzymatic activity was at alkaline pH (pH 7.5) for all of the HG models (Fig. 3B). PME3-His6 enzymatic activity was the highest with substrates HG96B69 (7.23 nmol of methanol·μg of protein−1·min−1) and HG96B76P63 (6.43 nmol of methanol/μg of protein/min). In contrast, at this pH, the lowest activity was observed when blockwise-demethylesterified HG substrates (P-series) were used. Within the P-series, the highest activity was observed for HG96P64 (5.15 nmol of methanol·μg of protein−1·min−1). However, this activity was 20–30% lower compared with that observed for the B- and BP-series in the same range of DM. At pH 7.5, PME3-His6 enzymatic activity was decreased when substrates with a lower DM were used (Fig. 3B). A 1.3–4-fold decrease in activity was measured at slightly acidic pH values (pH 4–6) when HG96B69, HG96B77P63, and HG96P64 were used (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

Substrate specificity and pH dependence of PME3-His6. A, HG isolation and tailoring. Lime pectin was first saponified before HG isolation. The recovered HG0 was then highly methylated (96%, HG96). HG96 was further chemically (B-series) or enzymatically (P-series) demethylesterified to reach a specific DM. In the BP series, HG96 was first given alkaline base treatment before further action of orange PME. B, purified PME3-His6 activities assayed at three pH values (pH 7.5, 6.0, and 4.0) on various HG substrates with different lengths and degrees of methylation. Activities were determined colorimetrically using N-methylbenzothiazolinone-2-hydrazone and alcohol oxidase for released methanol oxidation. Data represent means ± S.D. (error bars) from three replicates. C, PME3-His6 enzyme activity assayed at pH 7.5 on HG substrates (B-series) with different lengths and a similar degree of methylation (HG96B69, HG37B72, and HG12B71). Data represent the means ± S.D. of three replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001.

The substrate specificity of PME3-His6 was also determined with HG (B-series) displaying an optimal DM (from 69 to 72) for the enzymatic activity but different degrees of polymerization (DP −96, −37, and −12). PME3-His6 activity was 30 and 40% higher with DP 96 compared with DP 37 and 12, respectively, indicating that it requires the longer chain of GalA to hydrolyze methyl esters on the HG backbone (Fig. 3C).

The best substrates of each series (HG96B69, HG96B77P63, and HG96P64), as well as HG96B20 and HG96B82, were used to determine the apparent Km of PME3-His6 at pH 7.5. Six different concentrations of substrates in a range of 0.03–1 mm were chosen. The lowest apparent kinetic constant was similar (∼5–6 μm) when using HG96B69 and HG96B77P63, respectively (Table 2). It slightly increased when using HG96B20 (∼9 μm) and was 2-fold higher with HG98B82 (12 μm). The highest apparent Km was observed with HG96P64 (∼224 μm), indicating a lower affinity for substrates displaying a blockwise methyl ester distribution pattern. All of these data indicate that PME3-His6 has a strong affinity for HGs displaying a random distribution of methyl esters (i.e. B- and BP-series) and with a high DM (∼70%). This is likely to be the type of substrates exported in the cell wall.

TABLE 2.

Km and Vmax values of PME3 obtained with HG types containing different degrees and pattern of methylation

PME3-His6 activity assays were performed at pH 7.5 on HG96B82, HG96B69, HG96B20, HG96B77P63, and HG96P64 substrates as described (43).

| Substrate | Apparent Vmax | Apparent Km |

|---|---|---|

| μmol MeOH/min/μg PME3 | μm substrate | |

| HG96B82 | 0.07 | 12 |

| HG96B69 | 0.05 | 5 |

| HG96B20 | 0.10 | 9 |

| HG97B77P63 | 0.05 | 6 |

| HG96P64 | 0.02 | 224 |

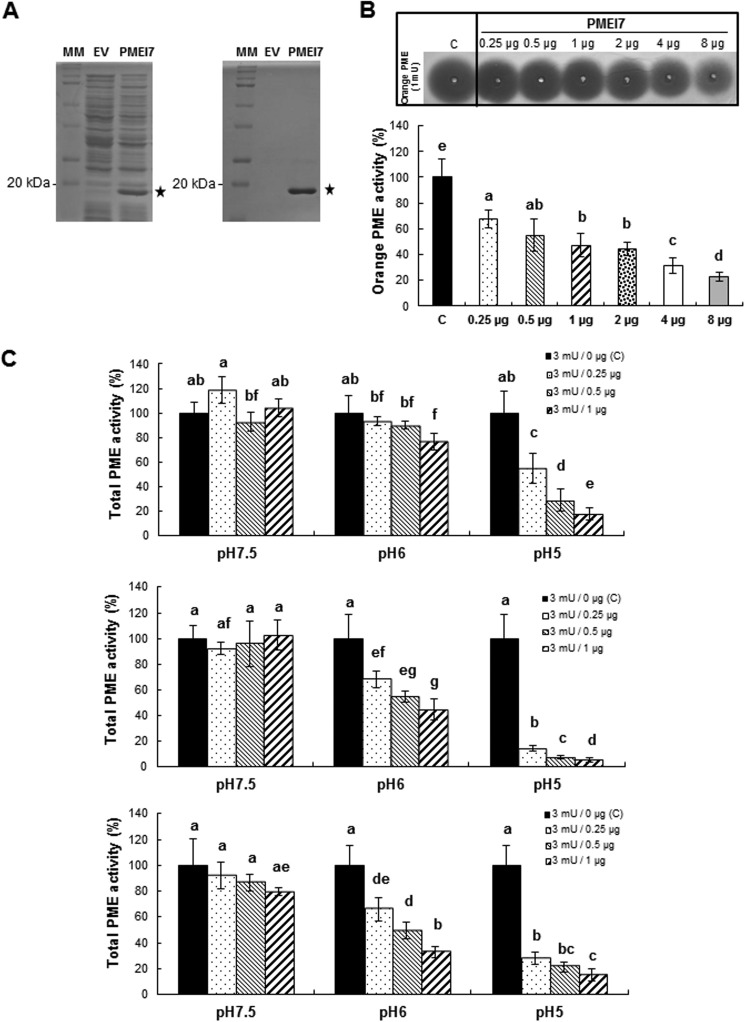

Recombinant PMEI7 Differentially Inhibits Total PME Activity from Different Arabidopsis Organs

In order to characterize the PME-inhibiting capacity of PMEI7-His6, the protein was expressed in E. coli as a fusion protein. For this purpose, the coding sequence, minus the putative signal peptide, was cloned in frame with a His6 tag. When compared with E. coli containing the empty vector (EV) (i.e. the expression vector without the PMEI7 insert), induced cultures harboring the construct (PMEI7-His6) displayed a clear band at the expected molecular mass of about 20 kDa (Fig. 4A, left). The putative PMEI7-His6 protein was subsequently purified using Ni-NTA-agarose beads, and the purified fraction (PMEI7) was resolved using SDS-PAGE showing a clear band at the expected size (Fig. 4A, right). Nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS analysis of this band showed 21 different peptides altogether, covering 90% of the PMEI7-His6 amino acid sequence (data not shown). The purified fraction was subsequently used for PME activity inhibition tests.

FIGURE 4.

Expression of PMEI7-His6 in bacteria. Purification and tests of PME activity inhibition. A, expression of PMEI7-His6 in E. coli and purification. SDS-PAGE analysis of total protein extracts (left) and Ni-NTA-purified protein extracts (right) of isopropylthio-β-galactoside-induced cultures containing empty vector (EV) or recombined vector (PMEI7). MM, molecular mass markers. B, gel diffusion assay of the inhibitory capacity of the purified PMEI7-His6 on commercial orange PME at pH 6.0. Experiments were carried out using 1 milliunit of orange PME and various quantities of purified PMEI7-His6. Results are means ± S.D. (error bars) of six replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001. C, quantification of the pH dependence of the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 on total PME activity of cell wall-enriched protein extracts from three Arabidopsis organs. Top, 3-week-old light-grown leaves; middle, 10-day-old light-grown roots; bottom, 4-day-old dark-grown hypocotyls. 3 milliunits of total PME activity was used with either PMEI7-His6 storage solution (■) or a PME activity/PMEI7-His6 (μg) ratio of 3:0.25 (dotted bars), 3:0.5 ( ), and 3:1 (▨). Results are means ± S.D. of six replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001.

), and 3:1 (▨). Results are means ± S.D. of six replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001.

To determine the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 toward PME activity, commercial orange PME was first used. Using a gel diffusion assay and a standard curve based on increasing quantities of orange PME activity, the relationship between the diameter of the halo and PME activity was established (data not shown). In a second step, 1 milliunit of orange PME was incubated for 30 min in the presence of increasing quantities (from 0.25 μg up to 8 μg) of purified PMEI7-His6 (Fig. 4B). Results showed that recombinant PMEI7 had an inhibitory effect on orange PME activity when a minimum of 0.25 μg of purified protein was used (∼30% inhibition of PME activity). This corresponded to a protein ratio of 0.1 μg/0.25 μg PME/PMEI. The inhibition of PME activity reached 80% when 8 μg of PMEI7-His6 was used. Various incubation times (0, 30, and 60 min) were tested, and no significant difference in the inhibition by PMEI7-His6 was shown when comparing 30 or 60 min (data not shown). Based on these results, we concluded that PMEI7-His6 is indeed an inhibitor of PME activity.

The inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 on Arabidopsis PMEs was then tested on cell wall-enriched protein extracts from various organs (leaves, roots, and hypocotyls), which were incubated with increasing quantities of purified PMEI7-His6 (Fig. 4C). The pH dependence of the inhibition effect was assayed using gel diffusion assays and 3 milliunits of total PME activity. Our results showed that PMEI7-His6 did inhibit PME activity of the cell wall-enriched protein extracts when the assay was carried out at slightly acidic to acidic pH values (pH 6.0 and 5.0). At pH 7.5, no inhibition of PME activity was shown for leaf and root extracts (Fig. 4C, top and middle). On the contrary, total PME activity of dark-grown hypocotyls was decreased by 22% when 1 μg of PMEI7-His6 was used (Fig. 4C, bottom). In this organ, several putative PME targets could thus form a complex with PMEI7-His6 in slightly alkaline conditions. Interestingly, the inhibition of total PME activity by PMEI7-His6 at acidic pH values differed, depending on the organs considered (Fig. 4C). Based on these results and on the PME3-PMEI7 co-expression data in dark-grown hypocotyls, we postulated that PMEI7 could be one of the key components of the regulation of PME3 and decided to investigate the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7 toward PME3.

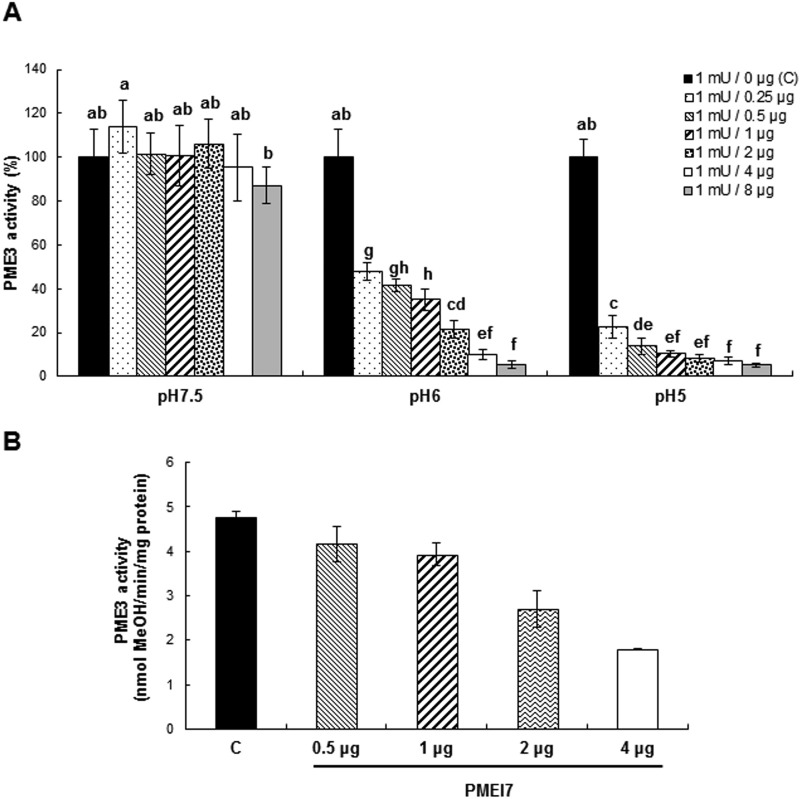

PMEI7 Interacts with PME3 to Inhibit Its Activity

To assess the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7 toward PME3, increasing quantities (from 0.25 μg up to 8 μg) of purified PMEI7-His6 were incubated for 30 min with 1 milliunit of PME3-His6. Recombinant PME3 enzymatic activity was then quantified using a gel diffusion assay with a pectin of DM 90% at three different pH values (pH 7.5, 6.0, and 5.0). We showed that PMEI7-His6 inhibited PME3-His6 activity and that this inhibition was pH-dependent. No inhibition was observed at pH 7.5 except when large quantities of PMEI7-His6 were used (8 μg; Fig. 5A). However, although this inhibition was relatively low (13% compared with the control), it showed that both recombinant PME3 and PMEI7 could interact in these neutral/alkaline conditions. In contrast, at pH 6.0, a 50% inhibition of PME3-His6 activity was observed even when using a low amount of PMEI7-His6 (0.25 μg). This corresponds to a PME3-His6/PMEI7-His6 protein ratio of 2 μg/0.25 μg or a molar ratio of ∼60 pmol/15 pmol. The inhibition of PME3-His6 enzymatic activity increased with increasing quantities of PMEI7-His6. Similar results, albeit more pronounced (80% of inhibition of PME3 activity using 0.25 μg of PMEI7-His6), were observed at pH 5.0. As shown using orange PME, no difference in the inhibition of PME3-His6 could be observed when incubating the protein with PMEI7-His6 for either 30 or 60 min (data not shown).

FIGURE 5.

Inhibition of PME3-His6 activity by PMEI7-His6 due to pH-dependent complex formation.

A, quantification, using a gel diffusion assay and a substrate of DM 90%, of the pH dependence of the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 on PME3-His6 enzymatic activity. 1 milliunit of PME3-His6 activity (corresponding to 2 μg of protein) was used with either PMEI7-His6 conservation solution (■) or a PME3-His6 activity (milliunits)/PMEI7-His6 (μg) ratio of 1:0.25 (lightly dotted bars), 1:0.5 ( ), 1:1 (

), 1:1 ( ), 1:2 (heavily dotted bars), 1:4 (□), and 1:8 (gray bars). Results are means ± S.D. (error bars) of six replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001. At the most acidic pH, the maximum inhibition of PME3-His6 activity is reached for a ratio of ±60 pmol of PME3-His6/60 pmol of PMEI7-His6. B, inhibition of PME3-His6 activity by PMEI7-His6 on the HG96B82 substrate. PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 were preincubated for 30 min at 30 °C at pH 6.0. HG96B82 was added to the mixture and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped at 90 °C for 10 min. PME activity was determined using a procedure adapted from Ref. 43. 1 μg of PME3-His6 was used with either PMEI7-His6 conservation solution (■) or a PME3-His6 activity/PMEI7-His6 (μg) ratio of 1:0.5 (

), 1:2 (heavily dotted bars), 1:4 (□), and 1:8 (gray bars). Results are means ± S.D. (error bars) of six replicates. The different letters indicate data sets significantly different according to Tukey's range test, preceded by a one-way ANOVA having p < 0.001. At the most acidic pH, the maximum inhibition of PME3-His6 activity is reached for a ratio of ±60 pmol of PME3-His6/60 pmol of PMEI7-His6. B, inhibition of PME3-His6 activity by PMEI7-His6 on the HG96B82 substrate. PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 were preincubated for 30 min at 30 °C at pH 6.0. HG96B82 was added to the mixture and incubated for 30 min at 30 °C. The reaction was stopped at 90 °C for 10 min. PME activity was determined using a procedure adapted from Ref. 43. 1 μg of PME3-His6 was used with either PMEI7-His6 conservation solution (■) or a PME3-His6 activity/PMEI7-His6 (μg) ratio of 1:0.5 ( ), 1:1 (▨), 1:2 (heavily dotted box), or 1:4 (□). Results are the means ± S.D. of two replicates.

), 1:1 (▨), 1:2 (heavily dotted box), or 1:4 (□). Results are the means ± S.D. of two replicates.

Next, we used HG96B82 and the base-released methanol method (42) to assay the inhibition of PME3-His6 activity by PMEI7-His6 under optimal substrate conditions. Increasing quantities (0.5–4 μg) of PMEI7-His6 were preincubated for 30 min with 2 μg of PME3-His6. PME activity was assayed at pH 6.0 because this does not completely inhibit the enzyme activity in the presence of PMEI7-His6 and thus allows observation of a progressive inhibition. HG96B82 was used as substrate because it displayed an affinity for the enzyme similar to that of HG96B69 and HG96B77P63 at pH 6.0 (Fig. 3B) and was available in large quantity compared with the other substrates. The inhibition of PME3-His6 enzymatic activity increased with increasing quantities of PMEI7-His6, and the best inhibition efficiency was for a ratio of 2 μg/4 μg PME/PMEI (Fig. 5B).

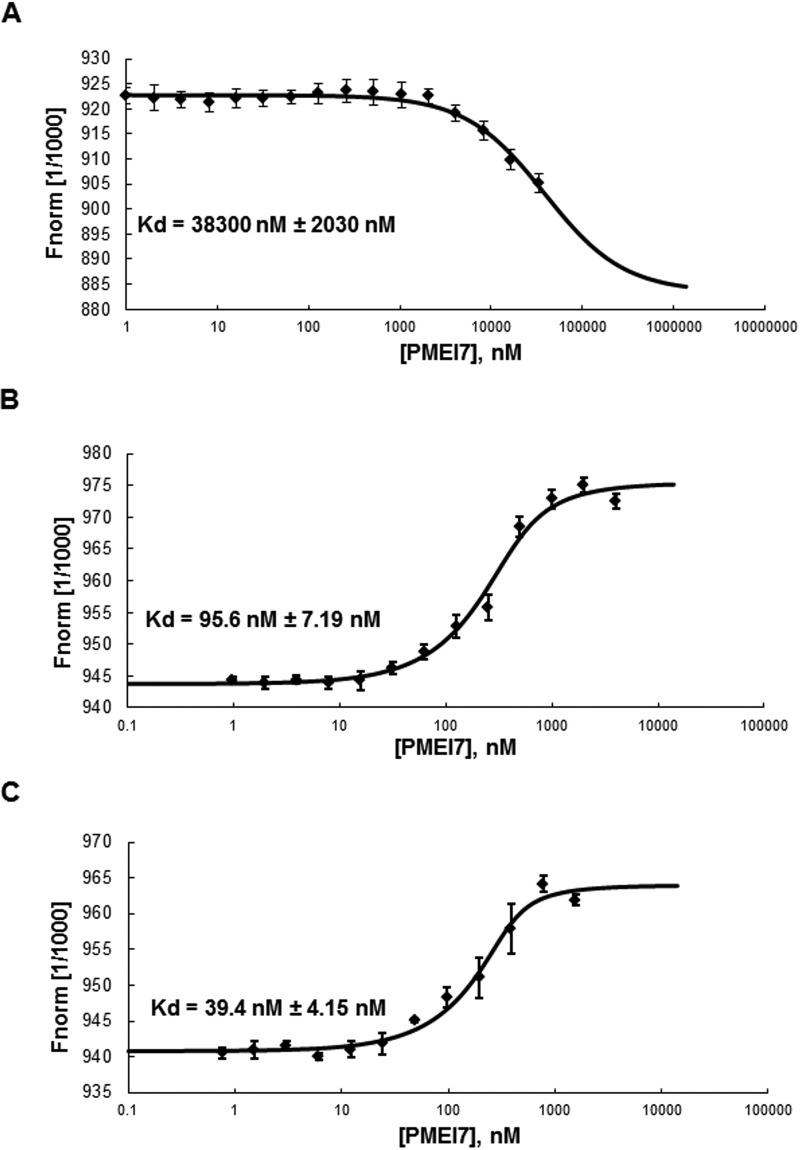

To investigate whether PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 physically interact in vitro, binding affinities of purified PME3-His6 with different concentrations of PMEI7-His6 at three different pH values (pH 7.5, 6.0, and 5.0) was determined by MST analyses. This sensitive new method measures the ligand-ligand interaction in vitro (49, 50). That method measures the motion of molecules along microscopic temperature gradients and detects changes in their hydration shell, charge, or size.

Recombinant PME3-His6 was labeled with the blue fluorescent dye. The addition of recombinant unlabeled PMEI7-His6 to the MST capillaries showed interaction between the two proteins in a pH-dependent manner (Fig. 6). The dissociation constant (Kd) in the MST measurement was higher at pH 7.5 (38 μm; Fig. 6A) than at pH 6 (96 nm; Fig. 6B) and pH 5 (39 nm; Fig. 6C). This suggests a higher affinity between PMEI7 and PME3 at acidic pH, as reflected by the Kd values at nanomolar levels. The sigmoidal binding curve observed at pH 7.5 is different from those obtained at acidic pH values. The different shape of the fit curves can be related to thermophoresis type (positive or negative), which is dependent on the pH, salt, solvation, and size of the molecules affecting the thermophoretic movement. Furthermore, the fluorescence intensity detected by the MST reader does not vary, indicating no or low aggregation of the proteins during the experiment (data not shown). All of these data confirm that there is a direct interaction between PME3 and PMEI7.

FIGURE 6.

Molecular interaction between PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 according to pH. The interaction between PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 was determined by MST. For the MST binding assay at various pH, PME3-His6 was labeled by a fluorescence blue dye, covalently attached to the protein. The concentration of the blue dye-labeled PME3-His6 was kept constant (333 nm), whereas the different concentrations of the non-labeled PMEI7-His6 between 33,000 and 1 nm, between 4000 and 0.98 nm, and between 1562 and 0.76 nm were used for pH 7.5 (A), pH 6 (B), and pH 5 (C), respectively. Mixtures of blue dye-labeled PME3-His6 and titrated non-labeled PMEI7-His6 were incubated for 15 min at room temperature and loaded into standard capillaries for MST experiments with 90% LED power and 40% MST power as thermophoresis conditions. The fit curve and the resulting dissociation constant (Kd) values were calculated by averaging replicates assimilated using NT analysis software. Kd values represent the mean ± S.D. (error bars) from 6–8 replicates, depending on pH. Concentrations on the x axis are plotted in nm. Kd of 38,000 ± 2030 nm, 95.6 ± 7.19 nm, and 39.4 ± 4.15 nm, respectively, were shown for pH 7.5, 6, and 5.

PME3 Generates Long Non-methylesterified Blocks on HG96B82, Which Are Reduced up to 50% in the Presence of PMEI7

Incubation of HG96B82 at pH 6.0 with PME3-His6 or the PME3-His6·PMEI7-His6 complex resulted in an 80 or 50% decrease in the DM, respectively (Table 3), thus confirming a strong inhibition of recombinant PME3 by PMEI7-His6. To gain insight into the methyl ester group distribution, non-treated, PME3-His6-treated, PMEI7-His6-treated, and PME3-His6·PMEI7-His6-treated HG96B82 samples were subsequently degraded by pectin lyase or endopolygalacturonase II. The degradation products were analyzed by high performance anion exchange chromatography with pulsed amperometric detection to determine the degree of blockiness (DB) and the DB of the highly methylesterified zones (DBMe). HG96B82 exhibited low DB and high DBMe values (3.6 and 81.4, respectively), as expected for a highly methylesterified HG sample with a random distribution of methyl groups (51). Similar DB and DBMe values were observed after incubation of HG96B82 with PMEI7-His6 alone, showing that PMEI7-His6 has no effect on the substrate methylation status. After incubation of HG96B82 with PME3-His6 alone, the DB value strongly increased (to 105) and the DBMe value strongly decreased (to 33.8), indicating the generation of long non-methylesterified zones interspersed with short methylesterified stretches. After incubation of HG96B82 with the PME3-His6·PMEI7-His6 complex, both DB and DBMe values were high (89.1 and 72.0, respectively), suggesting the presence of long non-methylesterified zones interspersed with long methylesterified ones. All of these data indicate different methyl ester group distribution patterns between HG96B82·PME3-His6 and HG96B82·PME3-His6·PMEI7-His6 samples but no impairment of the processivity of PME3-His6.

TABLE 3.

DB and DM for HG96B82 pretreated with PME3, PMEI, or a PME3/PMEI mixture at pH 6

The preincubated samples were digested by either pectin lyase or endopolygalacturonase. Values are the means of three samples. DB and DBMe (of non-methylesterified zones and methylesterified zones, respectively) are shown. DB and DBMe were determined as described (51). Values are expressed in mol % ± S.D.

| DM | DB | DBMe | |

|---|---|---|---|

| mol % | mol % | mol % | |

| HG96B82 | 80.5 ± 1.0 | 3.6 ± 1.8 | 81.4 ± 3.1 |

| HG96B82 + PME3 | 13.0 ± 0.6 | 105.0 ± 6.0 | 33.8 ± 3.6 |

| HG96B82 + PMEI7 | 79.4 ± 0.6 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 82.7 ± 3.7 |

| HG96B82 + PME3 + PMEI7 | 43.2 ± 0.6 | 89.1 ± 6.9 | 72.0 ± 2.3 |

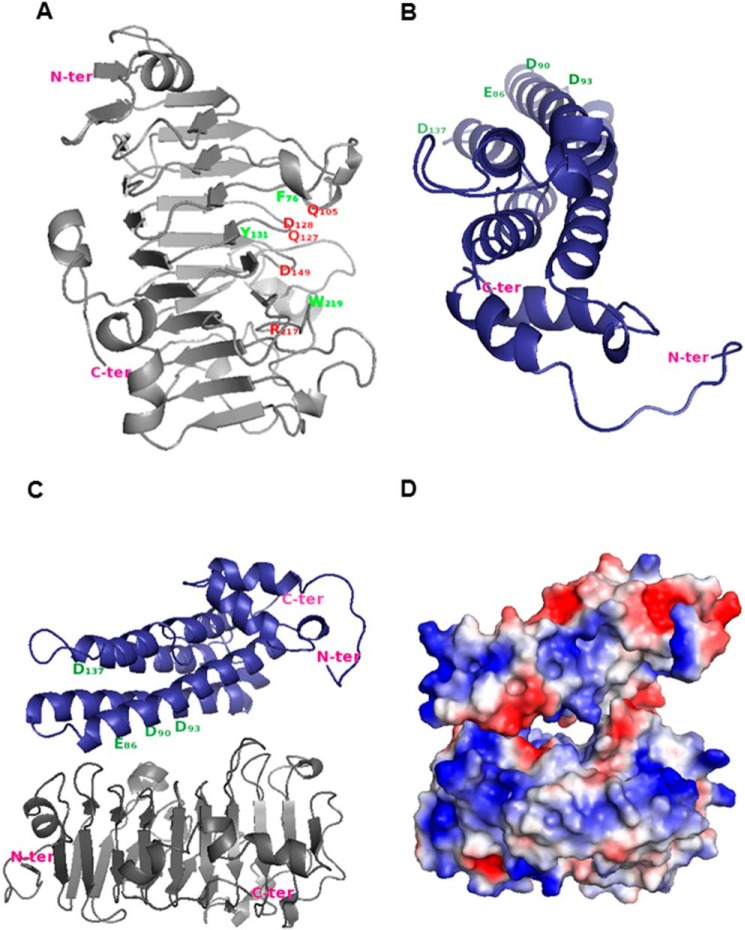

Docking Analysis Indicates That the Inhibition of PME3 Occurs via the Interaction of PMEI7 with the PME Ligand-binding Cleft Structure

The three-dimensional structure of PME3 was modeled using carrot PME coordinates (PDB code 1GQ8, chain A) as the best template. In the first step, PME proteins of known tertiary structure were searched for in the PDB. Multiple sequence alignment of PME3 with carrot and tomato PMEs showed that PME3 had the highest identity (79%) with carrot PME compared with tomato PME (61%). Homology modeling indicated a high similarity in the overall shape (Fig. 7A). The similarity of carrot PME and PME3 displayed a root mean square deviation value of 0.16 Å and a template modeling score of 0.97, demonstrating that the structure of plant PMEs is well conserved. The aromatic amino acid residues characteristic of the pectin/carbohydrate-binding site (Phe-83, Tyr-138, Phe-159, Tyr-221, Trp-226, Trp-248, and Trp-251) of the carrot PME structure were well co-aligned with Phe-76, Tyr-131, Phe-152, Tyr-214, Trp-219, Trp-241, and Trp-244 of PME3 with only one exception, Phe-249, which was not found in PME3, (29). Similarly, the amino acid residues of the carrot PME catalytic site (Gln-112, Gln-134, Asp-135, Asp-156, and Arg-224) were conserved at the same position in PME3 (Gln-105, Gln-127, Asp-128, Asp-149, and Arg-217).

FIGURE 7.

Proposed model for the inactivation of PME3 by PMEI7. A, PME3 model. Putative amino acid residues involved in the catalytic site are shown in red, and putative important residues involved in both the pectin-binding site and the PME-PMEI interaction are shown in green. B, PMEI7 model. Putative amino acid residues interacting with the PME pectin-binding site are shown in green. Arabidopsis PME3 and PMEI7 models were built using carrot PME (PDB code 1GQ8, chain A) and kiwi PMEI (PDB code 1XG2, chain B) coordinates, respectively. The tertiary structure was modeled according to Ref. 31. C, interaction between PME3 (gray) and PMEI7 (blue) was evaluated as described (55, 56) using LZerD based on shape complementarity. Model number 8 from the 15 best models was selected based on the literature data and the number of contacting residues. D, electrostatic potential of PMEI7 on PME3.

A similar approach was used for PMEI7. For this purpose, the search for the PMEI tertiary structure in the PDB and other servers enabled the selection of templates, including a kiwi PMEI (PDB code 1XG2, chain B) and an Arabidopsis cell wall invertase inhibitor (PDB code 1X8Z), showing the highest sequence identity of 18–20% and 19–21%, respectively (data not shown). The best model was obtained using kiwi PMEI. The root mean square deviation value (0.45 Å) and template modeling score (0.85) suggested that PMEI7 shared the same aligned fold structure as kiwi PMEI. The PMEI7 model showed an overall shape similar to that found in the PMEI structure despite the low sequence identity (Fig. 7B). Two important putative Asp residues, found to be part of PME·PMEI complex formation in kiwi PMEI (Asp-80 and Asp-83), are conserved in PMEI7 (Asp-90 and Asp-93) (53). In addition, some important amino acid residues of kiwi PMEI, including Glu-76 and Asp-116, covering the pectin-binding site of tomato PME, are conserved at the same position in PMEI7 (Glu-86 and Asp-137) (29).

The modeling of the interaction between PME3 and PMEI7 was performed by docking kiwi PMEI and carrot PME coordinates as templates. PMEI7 was perpendicular to the PME3 ligand-binding cleft structure. PMEI7 mostly covered the pectin-binding cleft of PME3, which normally harbors the substrate and catalytic site, thus preventing substrate access (Fig. 7, C and D). Our biochemical study at pH 5.0 indicated a 1:1 complex between PME3 and PMEI7, which is consistent with our docking model.

Discussion

In this study, we characterized PME3 and its inhibition by PMEI7. On the basis of gene expression analysis, PME3 and PMEI7 were identified, among other genes encoding HG-modifying enzymes (25, 34), as being expressed during dark-grown hypocotyl development. The proteins were identified in cell wall-enriched fractions of such hypocotyls using both nano-LC-ESI-MS/MS and MALDI-TOF MS analysis. PME3 was only present in a processed form, which is in accordance with the processing of group 2 PME isoforms at specific sites (6) and the recent identification of PME3 processing (10). Transcript level and proteome analyses strongly suggested that PME3 and PMEI7 were two major isoforms present in the cell wall of developing dark-grown hypocotyls and that these proteins could interact in muro. PME3 was previously shown to be a putative interacting protein of AtPMEI1 and AtPMEI2, regulating PME activity in response to plant pathogens, such as Botrytis (57). However, the existence of PME3-PMEI1 or PME3-PMEI2 pairs in vivo is highly questionable because it is known that whereas the two PMEI genes are specifically expressed in pollen, PME3 is widely expressed except in pollen (7, 22, 23). The occurrence of specific spatial and temporal PME-PMEI interactions is likely to be a key determinant of the fine tuning of HG-methylesterification status, as shown previously in the pollen tube (58).

The purification of the recombinant PME3-His6 protein enabled the characterization of its substrate specificity using dedicated HG models. To our knowledge, this is the first report of such a characterization for a PME from Arabidopsis. PME3-His6 activity was optimal at an alkaline pH (pH 7.5), which is similar to that reported for apple, banana, and green pepper PMEs (14, 59–61) and contrasts with that reported for fungal PMEs (62, 63). Interestingly, at an optimal pH, PME3-His6 activity was dependent on the DM and DP values and methylesterification distribution within HG. Using HG models, PME3-His6 showed a strong activity toward substrates, with a DM of 60–80%, a long chain of HG (DP >37%), and a random distribution of methyl ester groups, as reflected by the determination of apparent Km values. The apparent Km values obtained with the best substrates (HG98B69, HG96B77P63, and HG96B82) were lower but still in the same range as those found with LuPME5, a flax ortholog of PME3 (64). The difference could be related to the types of substrates used. In fact, we worked on pure HG and not on commercial pectin (DM 64), which was used for LuPME5. Surprisingly, the apparent Km value obtained with HG96B20 showed a stronger affinity of PME3-His6 for HG96B20 than for HG96B82. At pH 7.5, PME3 (pI ∼9.6) is positively charged and therefore interacts strongly with the many free carboxylic groups of HG96B20. Although plant PME enzymatic activity was previously shown to be optimal using a broad spectrum of pectic substrates, in the DM range of 62–94% (14, 15, 17, 65), our study brings new insight into the close relationship between HG structure (DP, DM, and pattern of methylesterification) and enzyme activity. This probably reflects, at the level of methylesterification, the preferential substrates that PME3 could target within the cell wall. The action of PME3 on HG96B82 (B-series) produces a methyl distribution pattern bearing a high level of blockwise non-methylesterified GalA zones and short methylesterified stretches. Our study could not assess the intermolecular heterogeneity of methyl ester group distribution. However, the identification of long demethylesterified blocks after the action of PME3-His6 on HG96B82 indicates that it is a processive enzyme in vitro and that the PME mode of action could be a single chain mechanism. We did not characterize the number and the size of the demethylesterified blocks per HG molecule. That could be investigated in the future and thus allow the determination of either a single chain mechanism or multiple attack mode of action of PME3 as described previously with apple PME and citrus PME (14, 17). Plant PMEs with basic pI have been shown to produce order distributions of methylated stretches within HG (3, 17, 51).

Understanding the specificity of the interactions between PME and PMEI is likely to be a key point in our understanding of how PME enzymatic activities could be fine tuned within the cell wall. So far, purified PMEIs from Arabidopsis have only been tested for their inhibitory capacity on either cell wall-enriched protein extracts or commercially available tomato and orange PMEs (22, 23). In our study, we expressed and purified PMEI7-His6 and showed, using MST experiments, that PME3-His6 and PMEI7-His6 formed a complex with higher affinity at acidic pH. At pH 7.5, the affinity of PMEI7-His6 for PME3-His6 was markedly decreased, as assessed by MST analysis, mainly due to a faster dissociation of the complex, as observed with the kaki PME·kiwi PMEI complex (66). The inhibition of PME3-His6 by PMEI7-His6 is pH-dependent, with an optimal inhibition at acidic pH (pH 5.0) and a stoichiometric ratio of 1:1. This suggests that, within the cell wall, at this pH, the majority of PME3 would be complexed with PMEI7 in a 1:1 molecular ratio. The pH dependence of the inhibition of PME by PMEI was previously reported for Arabidopsis PMEI·tomato PME complexes, but the optimal inhibition was at pH 6.5 (22). When using kiwi PMEI, distinct pH dependence of the inhibition was observed. In response to changes in pH, the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 was more similar to that observed with kiwi PMEI. This suggests that, depending on the presence of specific PME isoforms and the local changes in pH in the cell wall, distinct PME-PMEI pairs might occur. This hypothesis is in accordance with the observed differences in the inhibitory capacity of PMEI7-His6 toward cell wall-enriched extracts of various organs and with previous results (66, 67). The methylesterification pattern of HG was determined at pH 6.0, to evaluate the DBMe, in the presence of the PME3-His6·PMEI7-His6 complex. That condition provided a partial inhibition of PME3-His6 by PMEI7-His6 as expected, which means that the proteins alternately interact and dissociate. In order to gain insight into the specificity of the PME3-PMEI7 interaction, three-dimensional homology modeling of both proteins PME3 and PMEI7 was carried out and showed strong structural similarities with plant PME and plant PMEI structures (29, 52, 53). Docking analysis showed that inhibition most probably occurs through the interaction of PMEI7 with the ligand-binding cleft structure within PME3 as described previously for the crystallized structure of the tomato or kiwi PME·kiwi PMEI complex (29, 53). Amino acid sequence alignment between kiwi PMEI and PMEI7 displayed important common amino acid residues for the interaction. Among them, Asp-137 found in PMEI7 is conserved in kiwi PMEI. However, docking analysis indicated that Asp-137 is unlikely to be involved in the interaction. This might reveal structural differences among plant PMEIs. The discrepancy observed between tomato PME-kiwi PMEI and our PME3-PMEI7 model could also be due to species specificities. The determination of the crystallographic structure of PME3 and PMEI7 will help in deciding which hypothesis is the most likely.

From our in vitro experiments and the fact that genes are co-expressed, we assume that PME3-PMEI7 is one of the pairs that indeed fine tune the degree of methylesterification of pectins in the cell wall in dark-grown hypocotyls. However, considering the size of the PME and PMEI gene families, it is likely that distinct PMEIs could target PME3 and conversely that each PMEI could target several PMEs. For instance, PME32, which is as abundant as PME3 in dark-grown hypcotyl, based on proteomics data, could be another candidate for PMEI7. Our data should shed new light on the key role of PME-PMEI interactions in the regulation of PME activity in muro and the consequences on HG remodeling and development. Further studies are required to understand how PME-PMEI pairs could spatially and temporally control the DM of HG and its consequences for cell wall rheology.

Author Contributions

F. S. performed transcriptomic expression of PME3 and PMEI7, GUS assays, subcellular localization, and MST experiments. E. R and C. R. designed and cloned PME3. M. L., J.-M. D., and C. R. led PME3 purification. M. L. and C. R. performed PME3 enzyme activity assay experiments. O. S., A. M., and C. R. performed kinetic assay studies, and P. L. assisted in interpretations. P. M. and E. J. performed proteomic experiments. J. M., F. G. and F. S designed, cloned, and purified PMEI7. F. S. performed gel diffusion assays experiments, and J. P. assisted in interpretations. M.-C. R. and E. B. led studies of degree of blockiness (DB) with M.-J. C. J. E.-S., H. R. K., C. R., and D. K. led studies of protein modeling and docking. J. P. and C. R. designed the experiments. F. S., J. P., and C. R. wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by Agence Nationale de la Recherche Grants ANR-09-BLANC-0007-01 GROWPEC and ANR-12-BSV5-0001 GALAPAGOS and by the Conseil Régional de Picardie through a Ph.D. studentship (to F. S.). Work was also supported in part by the “Trans Channel Wallnet” project, which was selected by the INTERREG IVA program France (Channel)-England European cross-border cooperation program and National Institutes of Health Grant R01GM097528 (to D. K.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- GalA

- galacturonic acid(s)

- HG

- homogalacturonan

- PME

- pectin methylesterase

- PMEI

- DM, degree(s) of methylesterification

- DP

- degree(s) of polymerization

- DB

- degree of blockiness

- DBMe

- DB of highly methylesterified zones

- PMEI

- pectin methylesterase inhibitor

- TEV

- tobacco etch virus

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid

- ESI

- electrospray ionization

- MST

- microscale thermophoresis

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance.

References

- 1. Carpita N. C., Gibeaut D. M. (1993) Structural models of primary cell walls in flowering plants: consistency of molecular structure with the physical properties of the walls during growth. Plant J. 3, 1–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Caffall K. H., Mohnen D. (2009) The structure, function, and biosynthesis of plant cell wall pectic polysaccharides. Carbohydr. Res. 344, 1879–1900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ralet M.-C., Cabrera J. C., Bonnin E., Quéméner B., Hellìn P., Thibault J.-F. (2005) Mapping sugar beet pectin acetylation pattern. Phytochemistry 66, 1832–1843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sterling J. D., Quigley H. F., Orellana A., Mohnen D. (2001) The catalytic site of the pectin biosynthetic enzyme α-1,4-galacturonosyltransferase is located in the lumen of the Golgi. Plant Physiol. 127, 360–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pelloux J., Rustérucci C., Mellerowicz E. J. (2007) New insights into pectin methylesterase structure and function. Trends Plant Sci. 12, 267–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wolf S., Rausch T., Greiner S. (2009) The N-terminal pro region mediates retention of unprocessed type-I PME in the Golgi apparatus. Plant J. 58, 361–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Louvet R., Cavel E., Gutierrez L., Guénin S., Roger D., Gillet F., Guerineau F., Pelloux J. (2006) Comprehensive expression profiling of the pectin methylesterase gene family during silique development in Arabidopsis thaliana. Planta 224, 782–791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sexton T. R., Henry R. J., Harwood C. E., Thomas D. S., McManus L. J., Raymond C., Henson M., Shepherd M. (2012) Pectin methylesterase genes influence solid wood properties of Eucalyptus pilularis. Plant Physiol. 158, 531–541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Lionetti V., Cervone F., Bellincampi D. (2012) Methyl esterification of pectin plays a role during plant-pathogen interactions and affects plant resistance to diseases. J. Plant Physiol. 169, 1623–1630 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weber M., Deinlein U., Fischer S., Rogowski M., Geimer S., Tenhaken R., Clemens S. (2013) A mutation in the Arabidopsis thaliana cell wall biosynthesis gene pectin methylesterase 3 as well as its aberrant expression cause hypersensitivity specifically to Zn. Plant J. 76, 151–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Futamura N., Mori H., Kouchi H., Shinohara K. (2000) Male flower-specific expression of genes for polygalacturonase, pectin methylesterase and β-1,3-glucanase in a dioecious willow (Salix gilgiana Seemen). Plant Cell Physiol. 41, 16–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Yoo S.-H., Fishman M. L., Hotchkiss A. T. Jr., Lee H. G. (2006) Viscometric behavior of high-methoxy and low-methoxy pectin solutions. Food Hydrocolloids 20, 62–67 [Google Scholar]

- 13. Agoda-Tandjawa G., Durand S., Gaillard C., Garnier C., Doublier J. L. (2012) Properties of cellulose/pectins composites: implication for structural and mechanical properties of cell wall. Carbohydr. Polym. 90, 1081–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Denès J. M., Baron A., Renard C. M., Péan C., Drilleau J. F. (2000) Different action patterns for apple pectin methylesterase at pH 7.0 and 4.5. Carbohydr. Res. 327, 385–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Duvetter T., Fraeye I., Sila D. N., Verlent I., Smout C., Hendrickx M., Van Loey A. (2006) Mode of de-esterification of alkaline and acidic pectin methyl esterases at different pH conditions. J. Agric. Food Chem. 54, 7825–7831 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Thonar C., Liners F., Van Cutsem P. (2006) Polymorphism and modulation of cell wall esterase enzyme activities in the chicory root during the growing season. J. Exp. Bot. 57, 81–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cameron R. G., Luzio G. A., Goodner K., Williams M. A. K. (2008) Demethylation of a model homogalacturonan with a salt-independent pectin methylesterase from citrus: I. Effect of pH on demethylated block size, block number and enzyme mode of action. Carbohydr. Polym. 71, 287–299 [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ralet M. C., Dronnet V., Buchholt H. C., Thibault J. F. (2001) Enzymatically and chemically de-esterified lime pectins: characterisation, polyelectrolyte behaviour and calcium binding properties. Carbohydr. Res. 336, 117–125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. van Alebeek G.-J. W. M., van Scherpenzeel K., Beldman G., Schols H. A., Voragen A. G. J. (2003) Partially esterified oligogalacturonides are the preferred substrates for pectin methylesterase of Aspergillus niger. Biochem. J. 372, 211–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Daas P. J., Voragen A. G., Schols H. A. (2001) Study of the methyl ester distribution in pectin with endo-polygalacturonase and high-performance size-exclusion chromatography. Biopolymers 58, 195–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Jolie R. P., Duvetter T., Van Loey A. M., Hendrickx M. E. (2010) Pectin methylesterase and its proteinaceous inhibitor: a review. Carbohydr. Res. 345, 2583–2595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Raiola A., Camardella L., Giovane A., Mattei B., De Lorenzo G., Cervone F., Bellincampi D. (2004) Two Arabidopsis thaliana genes encode functional pectin methylesterase inhibitors. FEBS Lett. 557, 199–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wolf S., Grsic-Rausch S., Rausch T., Greiner S. (2003) Identification of pollen-expressed pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis. FEBS Lett. 555, 551–555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Peaucelle A., Louvet R., Johansen J. N., Höfte H., Laufs P., Pelloux J., Mouille G. (2008) Arabidopsis phyllotaxis is controlled by the methyl-esterification status of cell-wall pectins. Curr. Biol. 18, 1943–1948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Pelletier S., Van Orden J., Wolf S., Vissenberg K., Delacourt J., Ndong Y. A., Pelloux J., Bischoff V., Urbain A., Mouille G., Lemonnier G., Renou J.-P., Höfte H. (2010) A role for pectin de-methylesterification in a developmentally regulated growth acceleration in dark-grown Arabidopsis hypocotyls. New Phytol. 188, 726–739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Müller K., Levesque-Tremblay G., Bartels S., Weitbrecht K., Wormit A., Usadel B., Haughn G., Kermode A. R. (2013) Demethylesterification of cell wall pectins in Arabidopsis plays a role in seed germination. Plant Physiol. 161, 305–316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Saez-Aguayo S., Ralet M. C., Berger A., Botran L., Ropartz D., Marion-Poll A., North H. M. (2013) PECTIN METHYLESTERASE INHIBITOR6 promotes Arabidopsis mucilage release by limiting methylesterification of homogalacturonan in seed coat epidermal cells. Plant Cell 25, 308–323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hothorn M., Wolf S., Aloy P., Greiner S., Scheffzek K. (2004) Structural insights into the target specificity of plant invertase and pectin methylesterase inhibitory proteins. Plant Cell 16, 3437–3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Di Matteo A., Giovane A., Raiola A., Camardella L., Bonivento D., De Lorenzo G., Cervone F., Bellincampi D., Tsernoglou D. (2005) Structural basis for the interaction between pectin methylesterase and a specific inhibitor protein. Plant Cell 17, 849–858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hothorn M., Van den Ende W., Lammens W., Rybin V., Scheffzek K. (2010) Structural insights into the pH-controlled targeting of plant cell-wall invertase by a specific inhibitor protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 107, 17427–17432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sénéchal F., Graff L., Surcouf O., Marcelo P., Rayon C., Bouton S., Mareck A., Mouille G., Stintzi A., Höfte H., Lerouge P., Schaller A., Pelloux J. (2014) Arabidopsis PECTIN METHYLESTERASE17 is co-expressed with and processed by SBT3.5, a subtilisin-like serine protease. Ann. Bot. 114, 1161–1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Verwoerd T. C., Dekker B. M., Hoekema A. (1989) A small-scale procedure for the rapid isolation of plant RNAs. Nucleic Acids Res. 17, 2362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gutierrez L., Bussell J. D., Pacurar D. I., Schwambach J., Pacurar M., Bellini C. (2009) Phenotypic plasticity of adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis is controlled by complex regulation of AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR transcripts and microRNA abundance. Plant Cell 21, 3119–3132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guénin S., Mareck A., Rayon C., Lamour R., Assoumou Ndong Y., Domon J.-M., Sénéchal F., Fournet F., Jamet E., Canut H., Percoco G., Mouille G., Rolland A., Rustérucci C., Guerineau F., Van Wuytswinkel O., Gillet F., Driouich A., Lerouge P., Gutierrez L., Pelloux J. (2011) Identification of pectin methylesterase 3 as a basic pectin methylesterase isoform involved in adventitious rooting in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 192, 114–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Benhamed M., Martin-Magniette M.-L., Taconnat L., Bitton F., Servet C., De Clercq R., De Meyer B., Buysschaert C., Rombauts S., Villarroel R., Aubourg S., Beynon J., Bhalerao R. P., Coupland G., Gruissem W., Menke F. L. H., Weisshaar B., Renou J.-P., Zhou D.-X., Hilson P. (2008) Genome-scale Arabidopsis promoter array identifies targets of the histone acetyltransferase GCN5. Plant J. 56, 493–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Nakagawa T., Kurose T., Hino T., Tanaka K., Kawamukai M., Niwa Y., Toyooka K., Matsuoka K., Jinbo T., Kimura T. (2007) Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104, 34–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Clough S. J., Bent A. F. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16, 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Restrepo M. A., Freed D. D., Carrington J. C. (1990) Nuclear transport of plant potyviral proteins. Plant Cell 2, 987–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Pilling J., Willmitzer L., Fisahn J. (2000) Expression of a Petunia inflata pectin methyl esterase in Solanum tuberosum L. enhances stem elongation and modifies cation distribution. Planta 210, 391–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Irshad M., Canut H., Borderies G., Pont-Lezica R., Jamet E. (2008) A new picture of cell wall protein dynamics in elongating cells of Arabidopsis thaliana: confirmed actors and newcomers. BMC Plant Biol. 8, 94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Tanhatan-Nasseri A., Crépeau M.-J., Thibault J.-F., Ralet M.-C. (2011) Isolation and characterization of model homogalacturonans of tailored methylesterification patterns. Carbohydr. Polym. 86, 1236–1243 [Google Scholar]

- 42. Anthon G. E., Barrett D. M. (2004) Comparison of three colorimetric reagents in the determination of methanol with alcohol oxidase: application to the assay of pectin methylesterase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 3749–3753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Klavons J. A., Bennett R. D. (1986) Determination of methanol using alcohol oxidase and its application to methyl ester content of pectins. J. Agric. Food Chem. 34, 597–599 [Google Scholar]

- 44. Downie B., Dirk L. M., Hadfield K. A., Wilkins T. A., Bennett A. B., Bradford K. J. (1998) A gel diffusion assay for quantification of pectin methylesterase activity. Anal. Biochem. 264, 149–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ren C., Kermode A. R. (2000) An increase in pectin methyl esterase activity accompanies dormancy breakage and germination of yellow cedar seeds. Plant Physiol. 124, 231–242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bourgault R., Bewley J. D. (2002) Gel diffusion assays for endo-β-mannanase and pectin methylesterase can underestimate enzyme activity due to proteolytic degradation: a remedy. Anal. Biochem. 300, 87–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bradford M. M. (1976) A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal. Biochem. 72, 248–254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Baldwin L., Domon J.-M., Klimek J. F., Fournet F., Sellier H., Gillet F., Pelloux J., Lejeune-Hénaut I., Carpita N. C., Rayon C. (2014) Structural alteration of cell wall pectins accompanies pea development in response to cold. Phytochemistry 104, 37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wienken C. J., Baaske P., Rothbauer U., Braun D., Duhr S. (2010) Protein-binding assays in biological liquids using microscale thermophoresis. Nat. Commun. 1, 100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jerabek-Willemsen M., André T., Wanner R., Roth H. M., Duhr S., Baaske P., Breitsprecher D. (2014) Microscale thermophoresis: interaction analysis and beyond. J. Mol. Struct. 1077, 101–113 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Ralet M.-C., Williams M. A. K., Tanhatan-Nasseri A., Ropartz D., Quéméner B., Bonnin E. (2012) Innovative enzymatic approach to resolve homogalacturonans based on their methylesterification pattern. Biomacromolecules 13, 1615–1624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Johansson K., El-Ahmad M., Friemann R., Jörnvall H., Markovic O., Eklund H. (2002) Crystal structure of plant pectin methylesterase. FEBS Lett. 514, 243–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ciardiello M. A., D'Avino R., Amoresano A., Tuppo L., Carpentieri A., Carratore V., Tamburrini M., Giovane A., Pucci P., Camardella L. (2008) The peculiar structural features of kiwi fruit pectin methylesterase: amino acid sequence, oligosaccharides structure, and modeling of the interaction with its natural proteinaceous inhibitor. Proteins 71, 195–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. D'Avino R., Camardella L., Christensen T. M. I. E., Giovane A., Servillo L. (2003) Tomato pectin methylesterase: modeling, fluorescence, and inhibitor interaction studies-comparison with the bacterial (Erwinia chrysanthemi) enzyme. Proteins 53, 830–839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Venkatraman V., Yang Y. D., Sael L., Kihara D. (2009) Protein-protein docking using region-based 3D Zernike descriptors. BMC Bioinformatics 10, 407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Esquivel-Rodriguez J., Filos-Gonzalez V., Li B., Kihara D. (2014) Pairwise and multimeric protein-protein docking using the LZerD program suite. Methods Mol. Biol. 1137, 209–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Lionetti V., Raiola A., Camardella L., Giovane A., Obel N., Pauly M., Favaron F., Cervone F., Bellincampi D. (2007) Overexpression of pectin methylesterase inhibitors in Arabidopsis restricts fungal infection by Botrytis cinerea. Plant Physiol. 143, 1871–1880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Röckel N., Wolf S., Kost B., Rausch T., Greiner S. (2008) Elaborate spatial patterning of cell-wall PME and PMEI at the pollen tube tip involves PMEI endocytosis, and reflects the distribution of esterified and de-esterified pectins. Plant J. 53, 133–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Grsic-Rausch S., Rausch T. (2004) A coupled spectrophotometric enzyme assay for the determination of pectin methylesterase activity and its inhibition by proteinaceous inhibitors. Anal. Biochem. 333, 14–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Castro S. M., Van Loey A., Saraiva J. A., Smout C., Hendrickx M. (2004) Activity and process stability of purified green pepper (Capsicum annuum) pectin methylesterase. J. Agric. Food Chem. 52, 5724–5729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Ly Nguyen B., Van Loey A., Fachin D., Verlent I., Indrawati, Hendrickx M., Hendrickx I. M. (2002) Purification, characterization, thermal, and high-pressure inactivation of pectin methylesterase from bananas (cv. Cavendish). Biotechnol. Bioeng. 78, 683–691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Christgau S., Kofod L. V., Halkier T., Andersen L. N., Hockauf M., Dörreich K., Dalbøge H., Kauppinen S. (1996) Pectin methyl esterase from Aspergillus aculeatus: expression cloning in yeast and characterization of the recombinant enzyme. Biochem. J. 319, 705–712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Gonzalez S. L., Rosso N. D. (2011) Determination of pectin methylesterase activity in commercial pectinases and study of the inactivation kinetics through two potentiometric procedures. Food Sci. Technol. 31, 412–417 [Google Scholar]

- 64. Al-Qsous S., Carpentier E., Klein-Eude D., Burel C., Mareck A., Dauchel H. L. N., Gomord V., Balangé A. P. (2004) Identification and isolation of a pectin methylesterase isoform that could be involved in flax cell wall stiffening. Planta 219, 369–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]