ABSTRACT

HLA-B*13 is associated with superior in vivo HIV-1 viremia control. Protection is thought to be mediated by sustained targeting of key cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes and viral fitness costs of CTL escape in Gag although additional factors may contribute. We assessed the impact of 10 published B*13-associated polymorphisms in Gag, Pol, and Nef, in 23 biologically relevant combinations, on HIV-1 replication capacity and Nef-mediated reduction of cell surface CD4 and HLA class I expression. Mutations were engineered into HIV-1NL4.3, and replication capacity was measured using a green fluorescent protein (GFP) reporter T cell line. Nef-mediated CD4 and HLA-A*02 downregulation was assessed by flow cytometry, and T cell recognition of infected target cells was measured via coculture with an HIV-specific luciferase reporter cell line. When tested individually, only Gag-I147L and Gag-I437L incurred replicative costs (5% and 17%, respectively), consistent with prior reports. The Gag-I437L-mediated replication defect was rescued to wild-type levels by the adjacent K436R mutation. A novel B*13 epitope, comprising 8 residues and terminating at Gag147, was identified in p24Gag (GQMVHQAIGag140–147). No other single or combination Gag, Pol, or Nef mutant impaired viral replication. Single Nef mutations did not affect CD4 or HLA downregulation; however, the Nef double mutant E24Q-Q107R showed 40% impairment in HLA downregulation with no evidence of Nef stability defects. Moreover, target cells infected with HIV-1-NefE24Q-Q107R were recognized better by HIV-specific T cells than those infected with HIV-1NL4.3 or single Nef mutants. Our results indicate that CTL escape in Gag and Nef can be functionally costly and suggest that these effects may contribute to long-term HIV-1 control by HLA-B*13.

IMPORTANCE Protective effects of HLA-B*13 on HIV-1 disease progression are mediated in part by fitness costs of CTL escape mutations in conserved Gag epitopes, but other mechanisms remain incompletely known. We extend our knowledge of the impact of B*13-driven escape on HIV-1 replication by identifying Gag-K436R as a compensatory mutation for the fitness-costly Gag-I437L. We also identify Gag-I147L, the most rapidly and commonly selected B*13-driven substitution in HIV-1, as a putative C-terminal anchor residue mutation in a novel B*13 epitope. Most notably, we identify a novel escape-driven fitness defect: B*13-driven substitutions E24Q and Q107R in Nef, when present together, substantially impair this protein's ability to downregulate HLA class I. This, in turn, increases the visibility of infected cells to HIV-specific T cells. Our results suggest that B*13-associated escape mutations impair HIV-1 replication by two distinct mechanisms, that is, by reducing Gag fitness and dampening Nef immune evasion function.

INTRODUCTION

The natural history of HIV-1 is influenced by human leukocyte antigen (HLA) class I polymorphisms (1–4). Notably, HLA-B*57 and B*27 are associated with viral load control and slower disease progression (5, 6), but other “protective” HLA class I alleles have also been identified (4, 7, 8). HLA-B*13 is one such allele, but it remains understudied in part because it is relatively rare in many populations (expressed in less than 4% of Caucasians [9] and Africans [10, 11] although its frequency exceeds 10% in some Asian populations [12–14]). HLA-B*13, of which the most common subtype is B*13:02 (15), is associated with lower viral loads in chronic infection (10, 11, 14, 16, 17) and lower hazard ratios of progression to AIDS in historic natural history studies (18). HLA-B*13 is also enriched among HIV controllers (6, 19, 20).

B*13-mediated protective effects are attributed, at least partially, to sustained targeting of conserved B*13-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) epitopes, particularly in HIV-1 Gag (11) and Nef (21). Optimally described B*13 epitopes have also been identified in Pol (22) although these responses appear to contribute less to control (11). Similar to the effects of B*57 (23–25) and B*27 (26), the protective effects of B*13 may also be mediated to some extent by costs to viral replicative fitness incurred as a result of immune escape within certain CTL epitopes, notably in Gag (27). These replicative costs may limit the net viral “benefit” gained via immune evasion, leading to relative viral control or reduced pathogenesis. In particular, selection of a Gag-I437L or -I437M escape mutation at the C-terminal anchor residue of the B*13-restricted p1Gag RI9 epitope (the 9-residue Gag sequence at position 429 to 437, RQANFLGKI429–437) substantially impaired in vitro HIV-1 replicative capacity (27, 28). Likewise, the B*13-driven Gag-I147L polymorphism, located four codons downstream of the p24Gag VV9 epitope (VQNLQGQMV135–143) confers minor replication defects (28).

Though fitness-reducing CTL escape mutations in HIV-1 commonly occur in Gag (28, 29), escape in Pol can also incur replicative costs (30, 31). In addition, naturally occurring sequence variation in Nef (32–34), including HLA-driven escape mutations (35, 36), can modulate this protein's major functions, including cell surface CD4 (37) and HLA class I (38) downregulation. However, the functional costs of B*13-driven immune escape mutations outside Gag and their possible contributions to B*13-mediated protective effects have not been investigated. Moreover, the extent to which secondary (compensatory) polymorphisms can restore fitness costs of primary B*13-driven escape mutations also remains incompletely known. Such effects, however, are supported by observations of reduced replication capacity of patient-derived B*13 Gag sequences in early, but not chronic, infection (25).

To further elucidate the replicative and functional consequences of B*13-driven HIV-1 evolution, we investigated the 10 polymorphisms in Gag, Pol, and Nef that are most commonly selected in B*13-expressing individuals (39). Specifically, we tested these polymorphisms alone and in biologically observed combinations for effects on in vitro HIV-1 replication capacity and Nef-mediated CD4 and HLA class I downregulation activity. Our results extend current knowledge of B*13-driven Gag replicative costs (27, 28) by identifying Gag-K436R as a compensatory mutation for Gag-I437L. We also provide evidence for a novel B*13-restricted CTL epitope terminating at Gag codon 147, B*13's most frequent escape site in HIV-1 (39). Notably, although B*13-associated substitutions in Pol and Nef did not impair viral replication, the B*13-associated Nef polymorphisms E24Q-Q107R, when expressed together, reduced Nef's ability to downregulate HLA class I from the infected cell surface. This, in turn, enhanced the recognition of infected cells by HIV-1-specific T cells in vitro. Though this mutation combination is observed in less than 5% of B*13-expressing persons, it nevertheless represents a novel consequence of CTL escape in HIV-1. Specifically, our results suggest that B*13-mediated immune control could also be attributable, at least in part, to CTL escape-driven attenuation of Nef's immune evasion function.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Definition of HLA-B*13-associated polymorphisms.

Ten published HLA-B*13 and/or B*13:02-associated polymorphisms in HIV-1 Gag (n = 4), Pol (n = 4), and Nef (n = 2), originally identified via statistical association with phylogenetic correction in the International HIV Adaptation Collaborative (IHAC) cohort comprising >1,800 antiretroviral-naive chronically HIV-1 subtype B-infected individuals (39), were selected for analysis (Table 1 and Fig. 1A; see also Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). These polymorphisms represent all B*13/B*13:02-associated sites in Gag, Pol, and Nef for which a specific “adapted” (CTL escape form) amino acid was identified at a P value of <0.0001 and q value of <0.05 in the original study (39). At two of these codons (protease 63 and reverse transcriptase [RT] 369), the original study identified two possible adapted forms; the one with the lower P value was selected for the present analysis. The extent to which these polymorphisms are enriched in B*13:02-positive (B*13:02+) versus B*13:02-negative (B*13:02−) individuals in the original study (39), along with their locations respective to published or bioinformatically predicted B*13-restricted CTL epitopes, is shown in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material.

TABLE 1.

Single and combination mutations in HIV-1 Gag, Pol, and Nef evaluated in this study

| Protein and mutation type | Mutation(s) | Mutant namea |

|---|---|---|

| Gag | ||

| Single | A146S | S--- |

| I147L | -L-- | |

| K436R | --R- | |

| I437L | ---L | |

| Combination | I147L-I437L | -L-L |

| A146S-I147L | SL-- | |

| I147L-K436R | -LR- | |

| I147L-K436R-I437L | -LRL | |

| A146S-I147L-K436R | SLR- | |

| K436R-I437L | --RL | |

| A146S-I147L-K436R-I437L | SLRL | |

| A146S-I147L-I437L | SL-L | |

| Pol | ||

| Single | L63S (protease) | S--- |

| Q334N (RT) | -N-- | |

| T369A (RT) | --A- | |

| K374R (RT) | ---R | |

| Combination | L63S-T369A-K374R | S-AR |

| T369A-K374R | --AR | |

| L63S-T369A | S-A- | |

| L63S-K374R | S--R | |

| Nef | ||

| Single | E24Q | Q- |

| Q107R | -R | |

| Combination | E24Q-Q107R | QR |

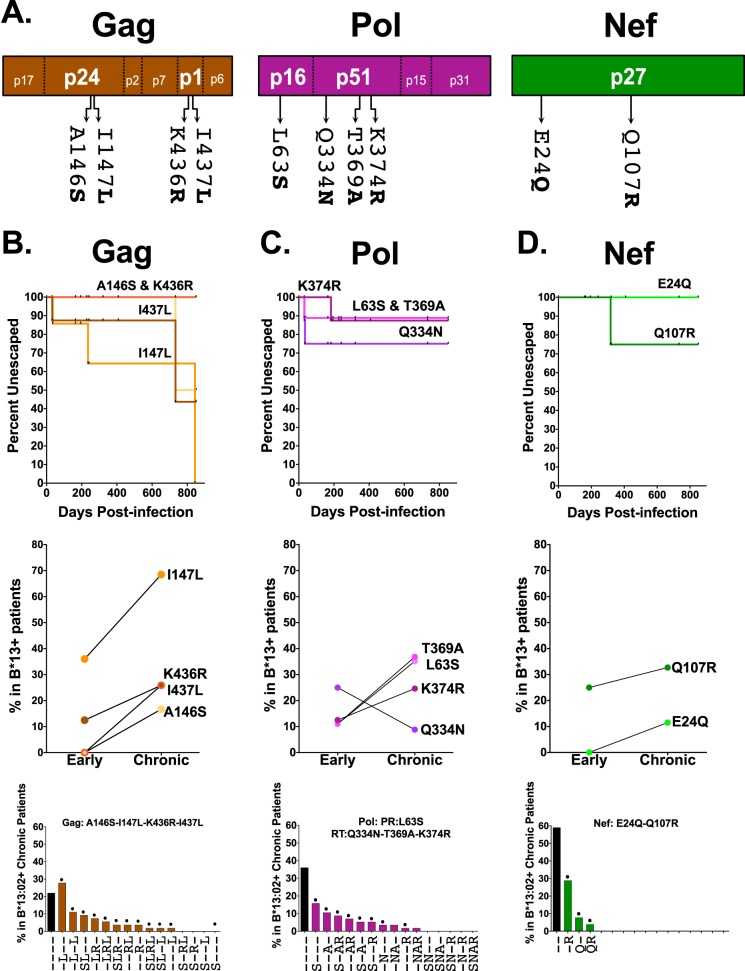

FIG 1.

HLA-B*13-associated polymorphisms in HIV-1 Gag, Pol, and Nef. (A) Locations of 10 published HLA-B*13-associated polymorphisms in HIV-1 subtype B Gag, Pol, and Nef (HXB2 codon numbering) (39). (B to D) Top panels show the rates of escape of these polymorphisms, calculated from longitudinal plasma HIV-1 RNA sequences from nine B*13:02 seroconverters using Kaplan-Meier methods. Note that curves for Gag-A146S-K436R and Pol-L63S-T369A are superimposed. Prevalences of these polymorphisms in B*13:02+ individuals in early (1 year postinfection; n = 9) and chronic (n = 69) infection are shown in the middle panels. Frequencies of these polymorphisms, alone and in combination, in 69 B*13:02+ individuals with chronic infection are shown in the bottom panels. Polymorphisms are listed in decreasing frequency, with hyphens denoting the wild-type (nonescaped) form. Single and combination mutants indicated with a dot were engineered into NL4.3 and tested for in vitro viral RC. PR, protease.

Characterization of escape rates and frequencies in B*13+ individuals.

The frequencies and kinetics of selection of B*13-associated polymorphisms in acute/early HIV-1 subtype B infection were defined using longitudinal plasma HIV-1 RNA sequences from nine B*13:02+ seroconverters from cohorts in Berlin (Jessen-Praxis Medical Clinic, Berlin, Germany), New York (Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center, New York, NY, USA), Boston (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA), and Vancouver (British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS; Vanguard and Vancouver Injection Drug Users Study [VIDUS], Canada) (40, 41). All patients provided written informed consent, and the cohort studies were approved by their respective institutional review boards. For four patients, HIV-1 sequences were already published (41). For others, HIV-1 RNA was extracted from plasma, and Gag, Pol, and Nef were amplified in independent nested reverse transcription-PCRs (RT-PCRs) using HIV-1-specific primers. Amplicons were bidirectionally sequenced on a 3130xl automated DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems, Inc.), and chromatograms were analyzed using Sequencher, version 5.0 (Genecodes). Sequences were aligned to the HIV-1 subtype B reference strain HXB2 (GenBank accession number K03455) using an algorithm based on the HyPhy platform (42). Time from estimated infection date to the first detection of the specific B*13-associated polymorphism was determined using Kaplan-Meier methods; these data were also used to calculate escape prevalence after 1 year of infection. The prevalence of these mutations in chronic infection was calculated using published plasma HIV-1 RNA sequences from 69 B*13:02+ individuals in the IHAC cohort (39). Note that cryopreserved peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were not available from these patients. Patient HIV and HLA data are available upon request in accordance with the Providence Health Care/University of British Columbia Institutional Review Board protocols.

Generation of mutant HIV-1.

B*13-associated polymorphisms were engineered into the HIV-1 subtype B reference strain NL4.3 (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, catalog 114; contributed by Malcolm Martin [43]). First, pNL4.3 gag, pol (covering protease and the first 400 codons of reverse transcriptase), and nef were subcloned into pCR2.1-TOPO (Life Technologies). Individual mutations were introduced into these plasmids using a QuikChange II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). Combination mutants were generated by successive rounds of mutagenesis. All mutants were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Mutant subcloned genes were then used to generate recombinant NL4.3 viruses by homologous recombination (25). Briefly, mutant gag, pol, and nef were reamplified from subclones using 100-mer primers complementary to NL4.3. After verification on an agarose gel, each amplicon was cotransfected, along with the relevant linearized pNL4.3 vector (Δgag, Δpol, or Δnef vector), into a Tat-inducible CEM-GFP-reporter (where GFP is green fluorescent protein) T cell line (GXR25) (44) via electroporation. Cells were incubated for 10 days at 37°C in R20+ medium (RPMI medium with phenol red, supplemented with 20% [vol/vol] fetal bovine serum [FBS] and 1% [vol/vol] penicillin-streptomycin) to allow the generation and propagation of infectious virions. GFP expression (indicating HIV-1 infection) of these cultures was monitored daily by flow cytometry (Guava easyCyte 8HT; Millipore); once this reached >15%, supernatants containing infectious mutant virions were harvested, aliquoted, and frozen at −80°C. The median time to harvest was 13 days (range, 11 to 14 days). HIV-1 RNA from each virus stock was reextracted (Invitrogen PureLink Genomic DNA/RNA kit; Life Technologies) and reamplified, and the relevant gene was resequenced to confirm the presence of the desired substitution(s) and the absence of any others.

In vitro HIV-1 replication capacity assays.

Viral titers were assessed as described previously by infecting GXR25 reporter cells in order to determine the volume necessary to achieve a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.003 (0.3% HIV-infected cells) at 2 days after infection (25, 31, 45, 46). For subsequent viral replication assays, GXR25 cells were infected with control (wild-type NL4.3 [wtNL4.3]) and mutant viruses at an MOI of 0.003, after which the percentage of GFP-positive (GFP+; HIV-infected) cells was monitored daily by flow cytometry until day 6. For each virus, the natural log of the slope of virus spread (measured as percent infected cells) was calculated during the exponential phase. This value was then normalized by the mean rate of spread of wtNL4.3 such that replication capacity (RC) values of <1.0 or >1.0 indicate a rate of viral spread lower than or higher than that of NL4.3, respectively. Each virus was assayed in a minimum of two independent experiments with each containing three replicates.

Characterization of a novel putative HLA-B*13:02-restricted epitope in p24 Gag.

The presence of a novel B*13:02-restricted epitope overlapping Gag146 and Gag147 was investigated bioinformatically and experimentally. First, the HIV-1 consensus B amino acid sequence at Gag135–155 was scanned for the presence of B*13:02-restricted 8- to 11-mer epitopes using NetMHCpan, version 2.8 (47, 48) (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/NetMHCpan/). This algorithm identifies candidate epitopes based on their predicted half-maximal inhibitory concentrations (IC50), where values of <500 nM, 500 to 5,000 nM, and >5,000 nM are predictive of strong binders, weak binders, and nonbinders, respectively (47, 48). After candidate epitopes were experimentally verified, binding predictions were repeated for variants containing B*13-associated polymorphisms at Gag146 and/or Gag147. PBMCs from seven B*13:02+ chronically HIV-1 subtype B-infected individuals recruited at the Hospital Clinic Barcelona (n = 4) and at IrsiCaixa AIDS Research Institute, Badalona (n = 3), Spain, collected with written informed consent, were screened for responses against C- and N-terminally extended versions of the predicted optimal epitope using a gamma interferon (IFN-γ) enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISpot) assay as described previously (31). The threshold for positive responses was defined as the highest of the following three criteria: a minimum of five spots per well, the mean number of spot-forming cells (SFC) of the negative-control wells plus three times its standard deviation, or three times the mean of negative-control well values (49). Plasma samples were also available from three of the patients; these were subjected to HIV-1 RNA Gag sequencing.

Assessment of Nef-mediated CD4 and HLA class I downregulation in infected cells.

Nef-mediated CD4 and HLA class I downregulation was assessed in a GXR25 cell line stably transduced to express HLA-A*02:01 (GXR-A*02). Briefly, one million GXR-A*02 cells were infected with Nef control and mutant viruses at an MOI of 0.01. Control viruses included wtNL4.3, NL4.3 with a deletion of Nef (ΔNef), and NL4.3 with an M20A mutation in Nef (NefM20A) (the latter two kindly provided by Takamasa Ueno, Kumamoto University), as well as an HIV-uninfected culture. The NefM20A virus was used as a control since it is impaired for HLA class I downregulation (50). The NL4.3-ΔNef virus was pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus G protein (VSV-G) to enhance infection in GXR-A*02 cells (51). Once HIV-1 infection reached ≈10 to 15%, 500,000 cells were stained with allophycocyanin (APC)-labeled anti-CD4 and phycoerythrin (PE)-labeled anti-HLA-A*02 antibodies (BD Biosciences), and cell surface expression of these molecules was measured by flow cytometry. The level of Nef-mediated CD4 downregulation of each virus was expressed as the ratio of the median fluorescence intensity (MFI) of CD4 expression in GFP+ (HIV-infected) cells to the MFI of CD4 in the uninfected cultures (the latter was used because CD4 downregulation precedes GFP expression in GXR25 cells, leading to lower MFIs in the GFP− gate in infected cultures). These values were then normalized to the value of the wtNL4.3 control. The calculation was as follows: [(1 − (MFI of GFP+nef mutant/MFI of GFP−uninfected))/(1 − (MFI of GFP+wtNL4.3/MFI of GFP−uninfected))] × 100. As such, normalized values of <100% and >100% indicate CD4 downregulation functions lower than or higher than values for wtNL4.3, respectively. The same calculation was used to quantify Nef-mediated HLA-A*02 downregulation. Viruses were assessed in a minimum of three independent experiments.

Impact of Nef-mediated HLA class I downregulation on infected-cell recognition by HIV-1-specific effector T cells.

To determine the impact of Nef-mediated HLA-A*02 downregulation on the recognition of infected target cells by HIV-1-specific effector T cells, we employed a reporter T cell coculture assay. Briefly, 1 million GXR-A*02 target cells were infected with control (wtNL4.3-Nef, ΔNef, or NefM20A) or Nef mutant virus at an MOI of 0.01 in R20+ medium without phenol red. Cultures were monitored daily by flow cytometry and used as “targets” when the proportion of GFP+ (HIV-infected) cells reached ≈10 to 15%. HLA-A*02-restricted reporter “effector” T cells were generated using a modification of previously described methods (52, 53). Briefly, Jurkat T cells were cotransfected with four expression plasmids: 3 μg each of pSELECTGFPZeo (Invivogen) containing T cell receptor α (TCRα) and TCRβ genes isolated from a CTL clone specific for the A*02-restricted p24Gag FK10Gag epitope (FLGKIWPSYK, Gag residues 433 to 442) (kindly provided by Mario Ostrowski and Brad Jones, University of Toronto); 5 μg of a CD8α expression plasmid (Invivogen); and 10 μg of a luciferase reporter plasmid driven by nuclear factor of activated T cells (NFAT) (Panomics/Affymetrix). Reporter effector T cells were electroporated using a Gene Pulser Xcell Electroporation System (Bio-Rad Laboratories) (square-wave protocol; 500 V, 2,000 μF, 3 ms, and 1 pulse), recovered at room temperature for 10 min, and incubated for 18 h in R10+ medium (RPMI 1640 medium, 10% FBS, and 1% [vol/vol] penicillin-streptomycin) to allow the expression of TCR. A total of 50,000 HIV-1-infected target cells were cocultured with 50,000 effector cells (1:1 effector/target [E/T] ratio) for 6 h, and TCR-mediated signaling was detected as NFAT-driven luciferase expression using a Steady-Glo luciferase system (Promega) and quantified using a Tecan Infinite M200 plate reader. Prior studies have indicated that this signal is dependent on endogenously processed HIV-1 Gag FK10Gag peptide antigen presented on HLA-A*02.

Western blotting.

Western blotting was performed as described previously (36). GXR-A*02 cells were infected with control or mutant viruses. When cultures reached ≈10 to 15% infection, 800,000 cells were pelleted and lysed. Due to the similar molecular masses (≈27 kDa) of Nef and GFP (HIV-1 infection control), lysates were split in half, and two blots were processed in parallel (with Nef and the β-actin housekeeping gene control on one and GFP on the other). Cell lysates were subjected to SDS-PAGE using Mini-Protean TGX 4% to 20% gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and proteins were electroblotted onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (GE Healthcare). Nef was detected using a polyclonal rabbit antibody (NIH AIDS Research and Reference Reagent Program, catalog 2949; contributed by Ronald Swanstrom) (1:4,000) (54), followed by staining with secondary donkey anti-rabbit antibody (GE Healthcare) (1:30,000). Expression levels of β-actin and GFP were assessed using primary mouse anti-actin (Sigma) (1:20,000) and primary mouse anti-GFP (1:10,000), respectively, followed by secondary goat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch) (1:20,000). Western blots were developed using Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories), based on the chemiluminescence detection method. Blots were developed with ImageQuant LAS 400 (GE Healthcare).

Statistical analyses.

The one-sample t test was used to assess whether replication capacities and CD4/HLA-A*02 downregulation functions of mutant NL4.3 viruses differed significantly from those of the wtNL4.3 reference strain (whose function was set to 1.0 for RC or 100% for CD4/HLA downregulation). A Bonferroni correction was used to adjust for multiple tests. Spearman's correlation was used to assess the relationship between Nef-mediated HLA-A*02 downregulation in HIV-infected target cells and NFAT-mediated TCR signaling in HIV-specific effector T cells. Statistical analyses were performed in Prism, version 5.0 (GraphPad Software). All tests of significance were two tailed.

RESULTS

Rates and frequencies of B*13-mediated escape in HIV-1 Gag, Pol, and Nef.

Ten published HLA-B*13 and/or B*13:02-associated polymorphisms in HIV-1 were investigated: A146S, I147L, K436R, and I437L in Gag; L63S in protease; Q334N, T369A, and K374R in reverse transcriptase; and E24Q and Q107R in Nef (Table 1 and Fig. 1A) (39). These polymorphisms are significantly enriched in B*13:02+ individuals with chronic HIV-1 subtype B infection, and nine of them lie within or near published or predicted B*13-restricted CTL epitopes (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). In addition, Gag-I437L and, to a lesser extent, Gag-K436R are experimentally verified B*13-driven escape mutations within the RI9Gag epitope (RQANFLGKI429–437) (11) while Nef-Q107R confers escape from CTL responses against the RI9Nef epitope (RQDILDLWI106–114) (21). Together, these observations support these 10 polymorphisms as commonly selected B*13 escape mutations in vivo.

To infer the extent and timing of HLA-B*13-driven escape during HIV-1 infection, we analyzed longitudinal plasma HIV-1 RNA sequences from nine B*13:02+ seroconverters (40, 41) and cross-sectional sequences from 69 B*13:02+ individuals with chronic infection (39). In HIV-1 Gag, 36% and 13% of B*13:02+ individuals harbored Gag-I147L and -I437L, respectively, at 1 year postinfection; by the chronic stage, 69% and 26% of B*13:02+ individuals harbored these substitutions (Fig. 1B, top and middle). In contrast, Gag-A146S and Gag-K436R emerged later in infection (reaching 17% and 26%, respectively, by the chronic stage). For HIV-1 Pol, the protease-L63S, RT-T369A, and RT-K374R substitutions were observed in ≈12% of B*13:02+ individuals in early infection and in 25 to 37% of B*13:02+ individuals in chronic infection (Fig. 1C, top and middle). RT-Q334N frequency was higher in early (25%) than in chronic (9%) infection sequences, suggesting it as a possible transient escape form in some individuals (40); however, our ability to conclude this is limited since the data are derived from independent cross-sectional early and chronic cohorts rather than from longitudinal samples from the same individuals. For HIV-1 Nef, E24Q was observed in 0% and 12% of early and chronic infection sequences whereas Q107R was observed in 25% and 33% of sequences at these stages, respectively (Fig. 1D, top and middle).

Chronic HIV-1 sequences were additionally analyzed for the presence of naturally occurring mutant combinations (Fig. 1B, C, and D, bottom). We began by engineering all combinations observed at >5% frequency (plus the Nef double E24Q-Q107R mutation, observed at 4% frequency) into an HIV-1NL4.3 backbone. Later, we engineered two additional Gag combinations for our analyses of compensatory mutation pathways. Together a total of 23 mutant viruses (10 single and 13 combination mutations) were constructed (Table 1).

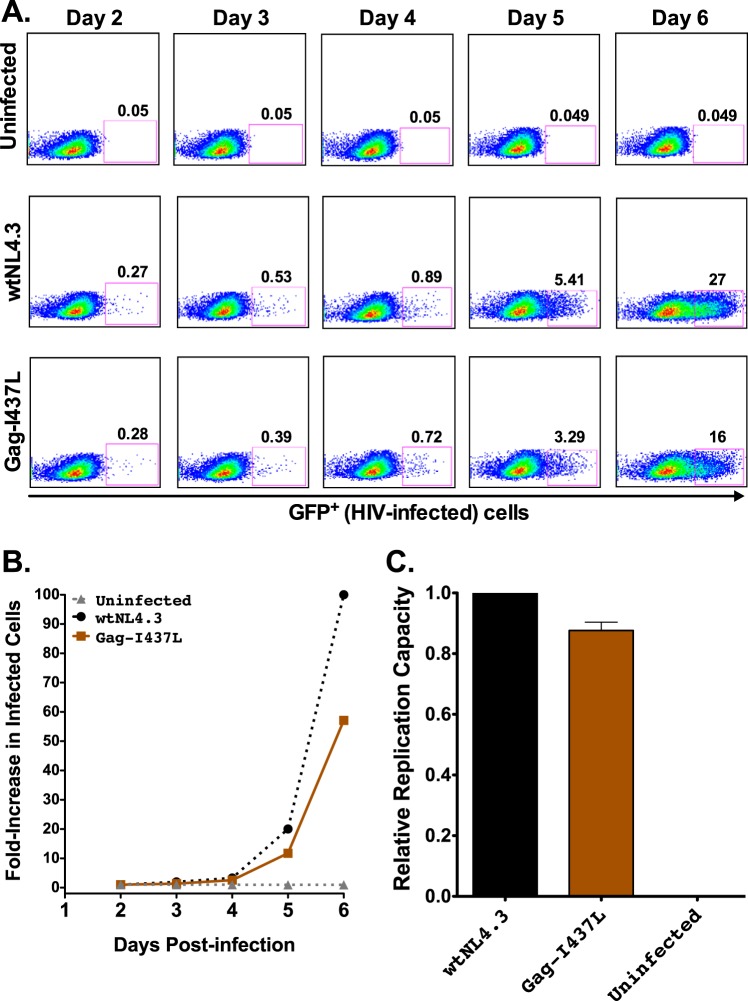

Impact of HLA-B*13-associated polymorphisms in Gag on viral RC.

Mutant HIV-1NL4.3 viruses were evaluated using a multicycle in vitro replication capacity (RC) assay using the GXR25 GFP reporter cell line (25, 44). Representative data are shown in Fig. 2, including flow cytometry results, viral growth curves, and wtNL4.3-normalized replication capacity measurements for uninfected cultures and those infected with wtNL4.3 and Gag-I437L virus (which is known to impair in vitro RC) (27, 28).

FIG 2.

HIV-1 replication capacity: control data. (A) Representative flow plots of virus spread in culture (measured as percent GFP+ cells) for uninfected controls and cells infected with wtNL4.3 and mutant Gag-I437L viruses. (B) Growth curves for the data shown in panel A, expressed as the fold increase in infected cells from the day 2 value. (C) Mean RC value for Gag-I437L normalized to that of the wtNL4.3 control, from one representative experiment containing three replicates. Histograms and error bars denote the means and standard deviations, respectively.

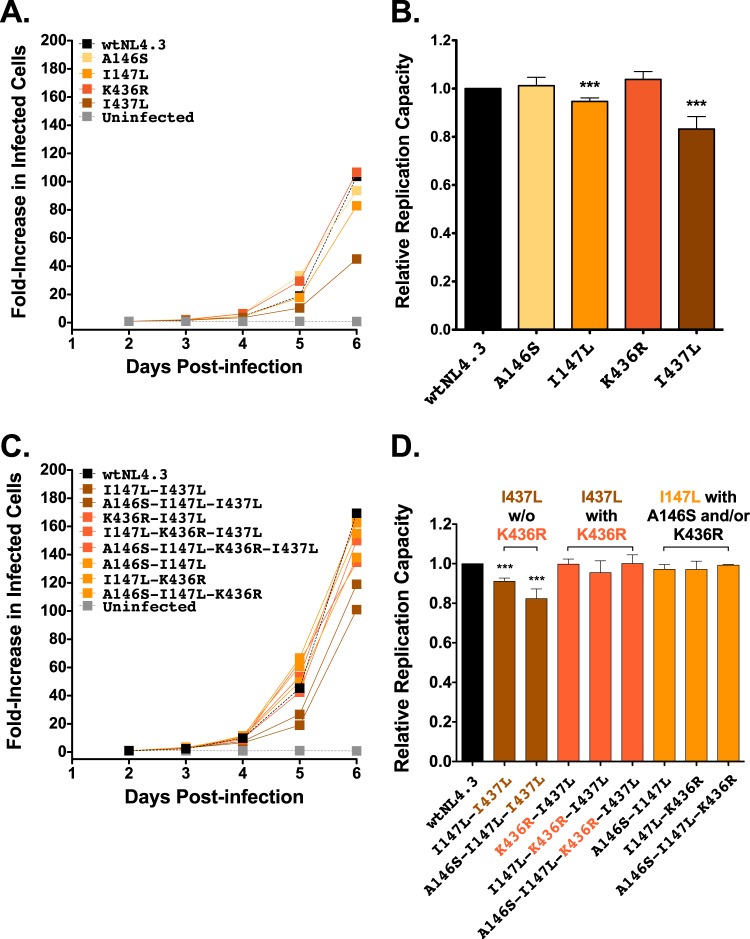

When engineered alone into HIV-1NL4.3, two of the four B*13-associated Gag polymorphisms, Gag-I147L and Gag-I437L, reduced RC by 5% and 17%, respectively (P < 0.001), while replication capacities of Gag-A146S and Gag-K436R viruses were comparable to the wtNL4.3 level (Fig. 3A and B). The RC measurements for Gag-I147L, Gag-K436R, and Gag-I437L viruses are consistent with those of previous studies conducted in Jurkat T cells and CD8+-depleted peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (27, 28). To our knowledge, no studies have previously investigated A146S for RC costs (though A146P, which is selected by HLA-B*57 and other alleles [39, 55], does not carry a replicative cost in PBMCs [28, 55, 56]).

FIG 3.

Replication capacities of NL4.3 viruses encoding B*13-associated polymorphisms in Gag. (A) Representative growth curves of single Gag mutants, expressed as the fold increase in infected cells from the day 2 value. (B) NL4.3-normalized RC values of each single Gag mutant, derived from two independent experiments, each containing triplicate measurements. Histograms and error bars denote the means and standard deviations, respectively. ***, P < 0.001. (C and D) Experiments are the same as those described for panels A and B, respectively, but with data for combination Gag mutants.

B*13-associated polymorphisms have not been evaluated previously in combination for their effects on RC; in particular, it is unclear whether they all represent primary escape mutations or may also include secondary (compensatory) changes. Eight B*13-associated polymorphism combinations in Gag were therefore assessed (Fig. 3C and D). The two combinations that contained Gag-I437L in the absence of the adjacent K436R (i.e., I147L-I437L and A146S-I147L-I437L) exhibited 9% and 17% reductions in RCs, respectively. These values were significantly lower than the wtNL4.3 value (P < 0.001) but not significantly different than the value for Gag-I437L alone, indicating that neither A146S nor I147L compensates for Gag-I437L-mediated replicative costs. In contrast, mutant combinations that included Gag-I437L in the presence of K436R (K436R-I437L, I147L-K436R-I437L, and A146S-I147L-K436R-I437L) exhibited RCs comparable to the wtNL4.3 value, indicating that the replicative cost of Gag-I437L was compensated by the adjacent K436R. Similarly, the three combination mutants with Gag-I147L in the presence of the adjacent A146S and/or the downstream K436R also exhibited RCs that were not significantly different from the wtNL4.3 value. This suggests that the modest replicative cost of Gag-I147L in the absence of I437L might be compensated by A146S or K436R although further study will be required to elucidate these mechanisms, particularly in the case of K436R, which lies in a different Gag protein subunit (p1).

A novel putative B*13-restricted epitope in p24 Gag.

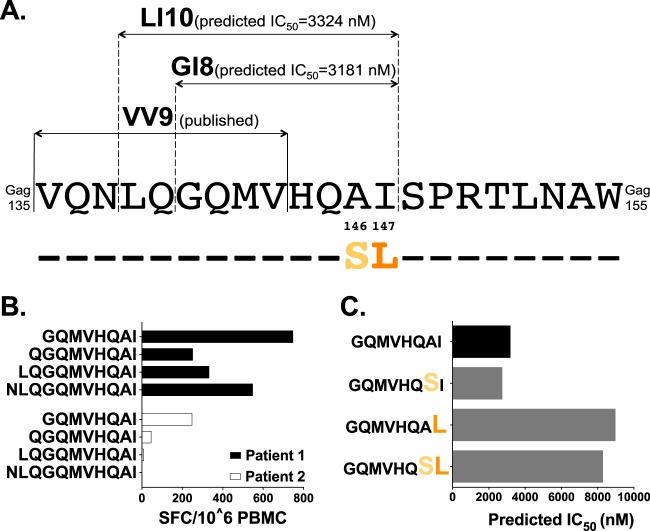

The region spanning Gag135–155 is dense in CTL epitopes (22). It has previously been hypothesized that Gag-I147L confers escape from CTL targeting the upstream B*13:02-restricted VV9 epitope (VQNLQGQMV135–143) (Fig. 4A) via an antigen-processing mechanism (11). Another possibility is that Gag-A146S and/or -I147L confers escape from an undiscovered B*13:02-restricted epitope at this site, a hypothesis that is consistent with the higher prevalence of escape within (versus outside) CTL epitopes (39). To investigate this, we utilized NetMHCpan, version 2.8, to predict B*13:02-restricted epitopes in the HIV-1 subtype B consensus sequence at Gag135–155. We identified two overlapping candidate epitopes, LI10 (Gag138–147) and GI8 (Gag140–147) (Fig. 4A), where the latter is fully embedded in the former. Predicted half-maximal (IC50) HLA binding affinities were 3,324 nM (LI10) and 3,181 nM (GI8), classifying them as weak binders of potentially low immunogenicity (57) (Fig. 4A). However, for context, the published adjacent VV9 epitope has a predicted IC50 of 9,174 nM, suggesting that responses to both LI10 and GI8 are feasible. Of note, Gag-A146S and -I147L lie at the penultimate and C-terminal residues of both LI10 and GI8.

FIG 4.

Prediction of a novel putative B*13-restricted CTL epitope in p24Gag. (A) Locations and sequences of published and bioinformatically predicted B*13:02-restricted epitopes are shown above the HIV-1 consensus B amino acid sequence spanning Gag135–155. (B) IFN-γ ELISpot responses, measured as the number of spot-forming cells (SFC) per million PBMCs, to predicted epitopes and their N-terminal extensions in two B*13:02+ chronically HIV-1 subtype B-infected patients who responded to this region. (C) NetMHCpan-predicted IC50 for GI8 and variants harboring the B*13:02-associated polymorphisms Gag-A146S and/or -I147L.

IFN-γ ELISpot assays were performed using PBMCs from two chronically infected B*13:02+ individuals with responses to this region. In both cases, GI8 elicited the strongest response to a series of N-terminally extended peptide sequences that included LI10 (Fig. 4B). Removal of the C-terminal isoleucine abrogated responses, suggesting that this position served as the F-pocket anchor residue for HLA-B*13 (data not shown). Limited cell numbers precluded HLA restriction confirmation and experimental validation of A146S and/or I147L as bona fide escape mutations. Still, the predicted IC50 values of GI8 variants harboring Gag-I147L were nearly 3-fold higher than the wild-type value, supporting I147L as a potential escape mutation (Fig. 4C). This conclusion is reinforced by the observation that responding patient 1 harbored wild-type I147 whereas patient 2 harbored I147L in plasma (data not shown): the latter's lower GI8 response is thus consistent with waning of CTL responses to the wild-type epitope following in vivo escape.

HLA-B*13-associated polymorphisms in Pol and Nef do not impair viral RC.

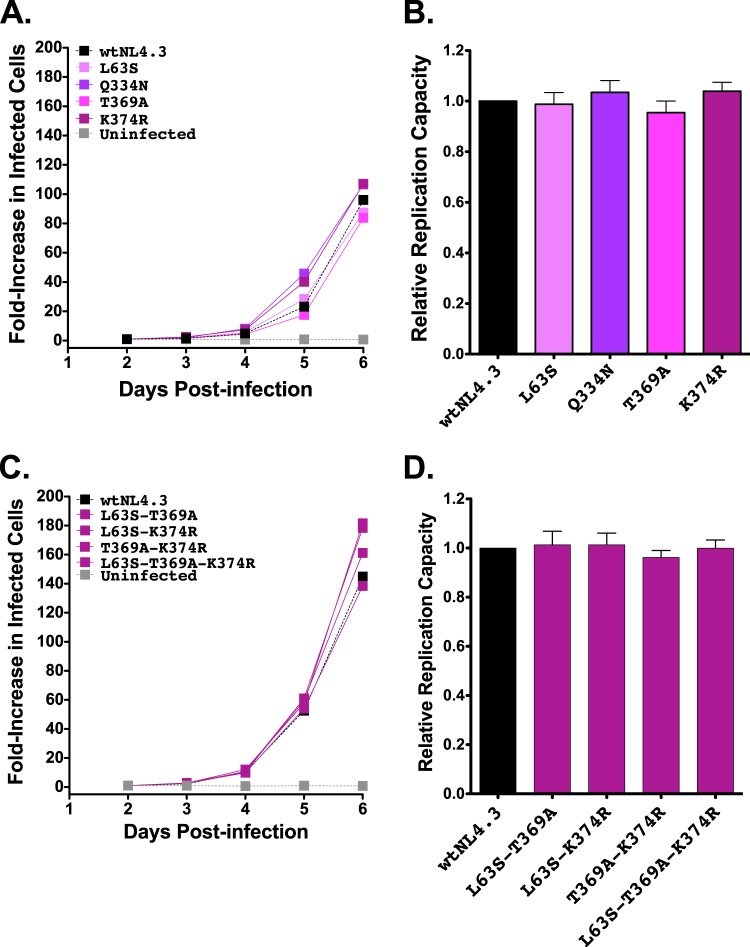

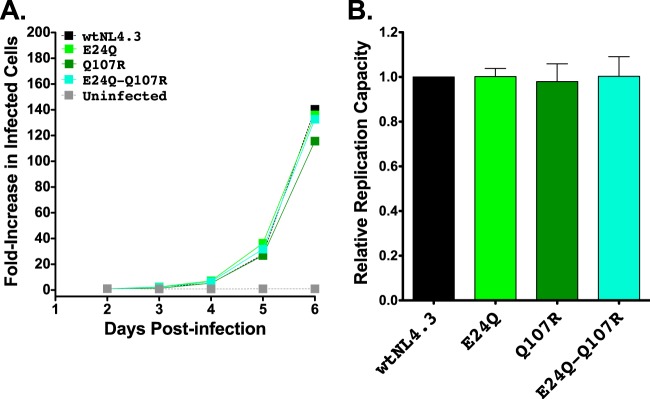

We next examined the effects of B*13-associated polymorphisms in Pol (L63S in protease and Q334N, T369A, and K374R in RT) and in Nef (E24Q and Q107R) on viral replication. None of the Pol substitutions significantly altered in vitro RCs when engineered alone into NL4.3 (Fig. 5A and B), and the four most common Pol mutant combinations observed in natural sequences also did not significantly affect RC (Fig. 5C and D). Similarly, the two B*13-associated Nef polymorphisms did not impair the RC, either alone or in combination (Fig. 6A and B). Note that the Nef observations are not simply attributable to the lack of requirement of this protein for viral replication in vitro as ΔNef virus replicated poorly in GXR25 cells (in experiments initiated at an MOI of 0.01, HIV-1ΔNef and VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1ΔNef exhibited 45% and 32% reductions in RCs, respectively, compared to the HIV-1NL4.3 level).

FIG 5.

Replication capacities of NL4.3 viruses encoding B*13-associated polymorphisms in Pol. (A) Representative growth curves of single Pol mutants, expressed as the fold increase in infected cells from the day 2 value. (B) NL4.3-normalized RC values of each Pol single mutant, obtained from two independent experiments, each containing triplicate measurements. Histograms and error bars denote the means and standard deviations, respectively. (C and D) Experiments are the same as those described for panels A and B, respectively, but with data for combination Pol mutants.

FIG 6.

Replication capacities of NL4.3 viruses encoding B*13-associated polymorphisms in Nef. (A) Representative growth curves of single and double Nef mutants, expressed as the fold increase in infected cells from the day 2 value. (B) NL4.3-normalized RC values of each Nef mutant, obtained from two independent experiments, each containing triplicate measurements. Histograms and error bars denote the means and standard deviations, respectively.

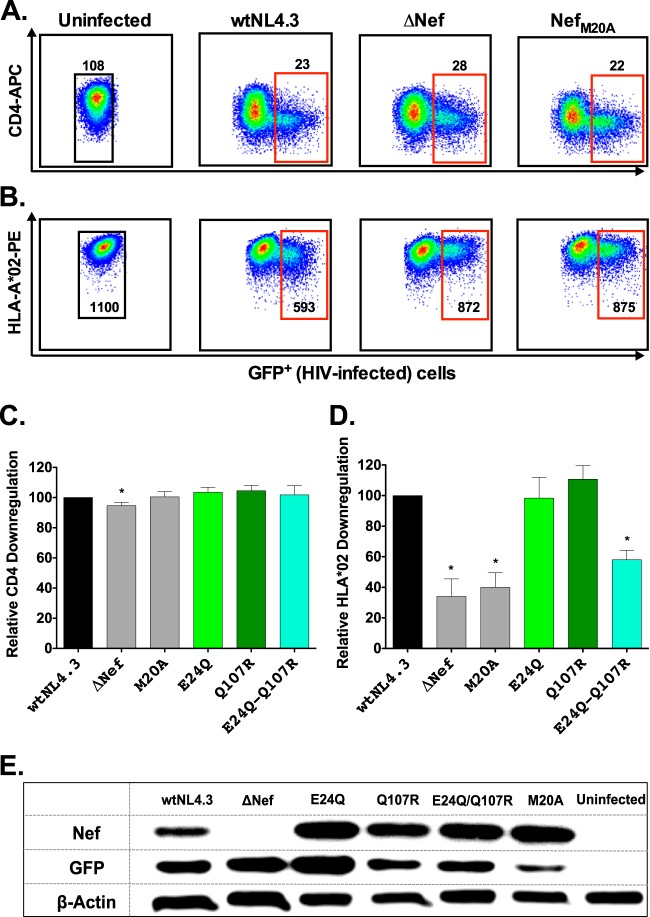

Impact of HLA-B*13-associated Nef polymorphisms on CD4 and HLA class I downregulation.

Naturally occurring sequence variation in Nef can modulate its CD4 and HLA class I downregulation activities (33–36, 58). We therefore investigated the impact of B*13-associated polymorphisms on Nef function. To this end, the GXR25 cell line was stably transduced to express HLA-A*02:01 (GXR-A*02) as a representative HLA class I molecule. GXR-A*02 cells were infected with control viruses (wtNL4.3, ΔNef, and NefM20A; the last is impaired for HLA class I downregulation [50] but replicates comparably to wtNL4.3 [data not shown]) or mutant Nef viruses (E24Q, Q107R, and E24Q-Q107R) and stained for surface CD4 and A*02 expression once infection reached ≈10 to 15%. Representative data for uninfected and control-infected cultures are shown in Fig. 7A and B. Compared to the activity of wtNL4.3, ΔNef virus displayed a modest (5%) reduction in CD4 downregulation that was nevertheless statistically significant and a substantial (66%) defect in HLA class I downregulation activity (P ≤ 0.01) (Fig. 7C and D). Efficient downregulation of CD4 by ΔNef virus is likely due to the actions of Vpu and Env in our culture system (59). The ability of NefM20A to downregulate CD4 was comparable to that of wtNL4.3, but the HLA downregulation function of NefM20A was impaired by 60% (P < 0.01). Neither Nef-E24Q nor -Q107R significantly affected CD4 or HLA class I downregulation alone; moreover, the CD4 downregulation function of the E24Q-Q107R double mutant was comparable to that of wtNL4.3. However, the ability of the double mutant to downregulate HLA class I was 42% reduced compared to that of wtNL4.3 (P = 0.007). Intracellular Nef expression was readily detectable in cultures infected with control and mutant HIV-1, suggesting that the attenuated HLA downregulation activity of the Nef double mutant was not simply due to poor expression or to a stability defect (Fig. 7E).

FIG 7.

Impact of B*13-associated polymorphisms on Nef-mediated CD4 and HLA class I downregulation. (A and B) Representative flow plots of CD4 (A) and HLA class I (B) downregulation for uninfected cells and cells infected with wtNL4.3, ΔNef, and NefM20A control viruses. Median fluorescence intensities (MFIs) of CD4 and HLA class I expression (y axis) are shown for GFP+ (HIV-infected; red gates) versus GFP− (HIV-1 uninfected; black gates) cells. (C and D) Impact of control viruses and those harboring B*13-associated Nef polymorphisms on CD4 and HLA-A*02 downregulation, normalized to wtNL4.3 levels. Receptor downregulation values were obtained from a minimum of three independent experiments, each containing one measurement. Histograms and error bars denote the means and standard deviations, respectively. *, P ≤ 0.01. (E) Detection of Nef, GFP, and β-actin protein expression by Western blotting in GXR-A*02 reporter T cells infected with NL4.3 viruses encoding control or mutant Nef sequences.

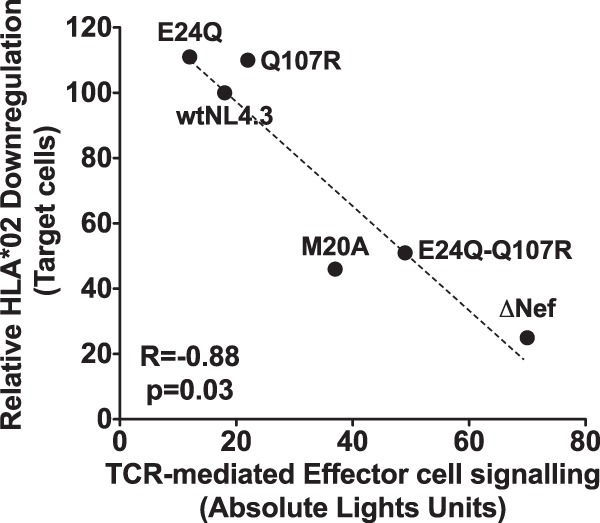

Impaired HLA class I downregulation of Nef double mutant renders infected cells more susceptible to recognition by HIV-1-specific T cells.

An impaired ability of the Nef-E24Q-Q107R double mutant to downregulate viral peptide/HLA complexes implies that cells infected with this virus should become more visible to HIV-specific CD8+ T cells, regardless of HLA restriction. To test this hypothesis, we used a novel coculture assay that features target cells (GXR-A*02 cells infected with control or mutant HIV-1) and HIV-1-specific effector cells transiently expressing an A*02-restricted FK10Gag-specific TCRα/β, CD8α, and an NFAT-driven luciferase reporter construct (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). In this assay, TCR-dependent signaling is quantified based on luminescence following coculture with A*02/FK10Gag-expressing target cells. Downregulation of HLA-A*02 by wild-type Nef from the infected target cell surface is expected to lead to reduced TCR signaling in effector cells, while target cells infected with HIV-1 containing defective Nef sequences that fail to downregulate HLA-A*02 should lead to increased TCR signaling.

Consistent with this, we observed a significant negative correlation between the extent of Nef-mediated HLA-A*02 downregulation on target cells and TCR-driven luciferase signal in HIV-1-specific effector cells (Spearman's R, −0.88; P = 0.03) (Fig. 8). This was confirmed in three independent experiments (Spearman's R, −0.82 to 0.89; P = 0.03 to 0.06). Importantly, control experiments using uninfected GXR-A*02 target cells and parental GXR25 target cells (lacking A*02) did not induce luciferase upon coculture with effector cells (data not shown), indicating that target cell recognition was HIV-1 epitope and HLA specific. Taken together, our results suggest that the impaired HLA class I downregulation activity of the B*13:02-associated Nef-E24Q-Q107R double mutant could render HIV-1-infected cells more vulnerable to CD8+ T cell responses in vivo.

FIG 8.

Impact of the Nef double mutant E24Q-Q107R on recognition of HIV-infected target cells by HIV-specific effector T cells. Representative data depicting a negative correlation between the Nef-mediated ability to downregulate HLA-A*02 on GFP reporter target cells infected with control and mutant Nef viruses and TCR-driven luciferase signal in A*02-FK10Gag-specific Jurkat effector cells following coculture (Spearman's R, −0.88; P = 0.03).

DISCUSSION

We engineered a total of 23 mutant HIV-1NL4.3 recombinant viruses harboring B*13-associated polymorphisms either alone (n = 10) or in naturally occurring combinations (n = 13) and investigated their effects on HIV-1 replication and Nef protein function. Our results extend current knowledge in multiple ways. First, we confirmed that escape via Gag-I437L incurs a substantial (17%) fitness cost (27, 28), and we extend this observation by demonstrating that the adjacent K436R mutation rescues in vitro RC to wild-type levels. This compensatory relationship is corroborated by the time course of selection of these polymorphisms in vivo (I437L is ultimately selected in 26% of B*13:02+ individuals; of these, 33% also developed K436R), the highly significant negative association reported between I437L and wild-type K436 in HIV-1 subtype B sequences (39), and evidence that despite its strong association with B*13:02, K436R alone does not confer escape in the majority of HIV-infected individuals (27, 60). Similarly, we confirmed that Gag-I147L, the most rapidly and frequently selected B*13:02 escape mutation in HIV-1 (39), incurs a minor (5%) replicative cost, which appears to be rescued by the adjacent A146S and/or distal K436R mutation. Again, these putative compensatory relationships are corroborated by their time course of selection (I147L is ultimately selected in 70% of B*13:02 individuals; of these, 13% also develop the A146S or K436R mutation). Taken together, we hypothesize that replicative costs of Gag-I147L and -I437L escape mutations, which usually occur within the first year of infection and may be compensated only later in fewer than half of cases, contribute to the long-term enhanced viremia control observed in B*13:02-expressing persons.

While B*13-mediated escape in Pol and Nef does not substantially impair viral RC, the B*13-driven Nef-E24Q-Q107R double mutant conferred a >40% reduction in Nef's ability to downregulate cell surface HLA class I. This defect was nearly as profound as that conferred by ΔNef or the Nef-M20A mutation (which does not occur naturally) in our assay system. Moreover, the inability of Nef-E24Q-Q107R to downregulate HLA class I enhanced the recognition of infected cells by HIV-1-specific T cells in vitro. In other words, this naturally occurring mutant combination, selected in vivo under B*13-mediated CTL pressure, conferred a functional cost to Nef's immune evasion activity. Although attenuation of Nef's HLA class I downregulation function as a consequence of CTL escape has been described previously (35, 36), the mutations required to confer these effects are rare in vivo. The HLA-B*35-driven Nef-R75T and -Y85F escape mutations, when present together, reduced Nef's HLA class I downregulation activity nearly 2-fold, but this combination occurs in <0.2% of natural HIV-1 sequences (35). Similarly, a Nef clone exhibiting ≈15% lower HLA downregulation activity was isolated from an acutely HIV-infected individual who subsequently controlled HIV-1 viremia spontaneously to <2,000 copies/ml; however, this defect required the selection of four Nef mutations in the context of two independent HLA alleles (36). Although the E24Q-Q107R double mutant is observed in only 4% of B*13-expressing individuals and although this combination tends to arise late in infection, it nevertheless represents the most frequent in vivo CTL escape pathway identified to date that significantly compromises this Nef function. Importantly, once this double mutant arises in vivo, its HLA downregulation defect would serve to boost the levels of viral epitopes complexed with all HLA-A and HLA-B alleles expressed by the individual (not just those restricted by HLA-B*13), thus rendering infected cells more susceptible to recognition by numerous HIV-1-specific T cells (or at least those specific for viral epitopes that had not yet developed CTL escape mutations). In fact, we hypothesize that the reason this double mutant is observed only rarely in vivo is because of its substantial functional cost.

Several limitations of the study merit comment. First, we focused on escape in Gag, Pol, and Nef because all known B*13-restricted epitopes lie in these proteins. However, undiscovered B*13 epitopes are likely to exist in other regions, as indicated by the existence of B*13-associated polymorphisms in gp41, Tat, Vif, and Vpr (39), and their impact on HIV-1 replication and protein function remains unknown. Second, due to the relatively large number of mutants assessed here, all replication capacity assays were performed in an immortalized GFP reporter T cell line. However, the magnitude of replication defects observed for Gag-I437L and Gag-I147L corroborated previous results in PBMCs (27, 28), indicating that RC measurements in our assay system are generally representative of those in other cell types. Third, due to insufficient PBMCs from B*13+ individuals, we were unable to fully characterize the novel GI8 epitope in p24Gag although its bioinformatically guided discovery (combined with reduced predicted binding affinities of its escape variants) supports it as such. Fourth, we assessed the impact of Nef-E24Q and/or Nef-Q107R on only three of Nef's in vitro functions (viral replication and CD4/HLA class I downregulation), but the impact of Nef-E24Q and Nef-Q107R on other Nef functions, including upregulation of HLA class II invariant chain (CD74) (61), enhancement of virion infectivity (62), and alteration of T cell receptor signaling (63), remains to be determined. Moreover, to evaluate the effect of Nef mutations on HLA downregulation and its consequences for T cell-mediated recognition of infected cells, we used HLA-A*02 and an FK10Gag-specific TCR as representative indicators of this process. Since HLA-B molecules may generally be more resistant to Nef-mediated downregulation than HLA-A molecules (64) and since the impact of Nef-mediated HLA downregulation may be to some extent HIV gene and/or epitope specific (65–67), recognition of other CTL epitopes might differ from that observed here for A*02-FK10Gag. However, using a transient-transfection system, we previously demonstrated a strong correlation between the ability of natural Nef sequences to downregulate HLA-A*02 and HLA-B*07 (34), and Gag-specific CTL in general may be less susceptible to Nef-mediated HLA downregulation than CTL targeting other HIV-1 proteins (67), possibly due to presentation of Gag epitopes before Nef-mediated HLA downregulation is complete (68). Together, these observations suggest that our luciferase reporter T cell approach should be broadly representative of CTL recognition and may be a conservative measure of Nef function. Finally, while we have demonstrated enhanced recognition of target cells infected with Nef-E24Q-Q107R mutant virus using a reporter T cell assay, we have not performed inhibition studies or assessed other effector functions directly with primary CTL clones.

The mechanism whereby Nef-E24Q and -Q107R together confer such a profound HLA downregulation defect requires further study. While these codons have not been explicitly identified as being critical for Nef function, both lie within or adjacent to important motifs. Nef-E24 is located in the N-terminal alpha helix within a region (amino acids 17 to 26) that, when deleted and engineered along with a V10E substitution, renders Nef defective for HLA downregulation (69); it also lies four codons downstream of M20, which, when artificially mutated to alanine, produces a severe HLA downregulation defect (50). Nef-Q107 lies adjacent to arginine residues R105/R106 that are essential for several Nef functions, including dimerization (70–72); it is therefore possible that the creation of a triple arginine (RRR105–107) via a Q107R substitution may alter this protein-protein interface. Mutations at the adjacent residue 106 (e.g., R106K and R106L) also confer modest to severe HLA class I downregulation defects (73). Moreover, a recent crystal structure of Nef in complex with HLA class I suggests that Nef codons 24 and 107 lie nearby and within (respectively) neighboring antiparallel alpha helices, suggesting that their presence in combination could modulate interactions between these helices and possibly impact HLA downregulation function (74). Further studies will be required to test this hypothesis and identify compensatory pathways in natural sequences.

Taken together with the previous literature, our results suggest that B*13-mediated viremia control is achieved via multiple mechanisms. The major mechanism, demonstrated by other studies, is likely to be effective sustained targeting of CTL epitopes in multiple HIV-1 proteins (11, 21). Fitness costs of the resulting viral escape mutations, which presumably limit the net viral “benefit” gained from evading the CTL response, also likely contribute. Specifically, B*13 escape mutations may impair HIV-1 by two distinct mechanisms: by reducing Gag fitness and by dampening Nef's immune evasion function by compromising its HLA downregulation activity. Functional costs of CTL escape in Nef have been reported by others (35, 36, 75); our results extend these observations by suggesting that such costs may be biologically relevant. More broadly, our study highlights the potential utility of HIV-1 T cell vaccines designed to target vulnerable epitopes in Nef where escape mutations impair its viral immune evasion activity.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Denis Chopera for engineering the pNL4.3-Δnef vector used in the homologous recombination procedure, Takamasa Ueno for providing control mutant Nef plasmids, Bemuluyigza Baraki for generating the GXR-A*02 cell line, and Mario Ostrowski and Brad Jones for providing the 5B2 CTL clone used to generate the FK10Gag-specific TCR. We thank Chanson Brumme for assistance with data analysis. We also thank Mina John, Simon Mallal, P. Richard Harrigan, Martin Markowitz, Bruce Walker, Heiko Jessen, Evan Wood, Kanna Hayashi, and M.-J. Milloy for specimen and/or data access.

This work was supported by operating grants from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) (MOP-93536 and HOP-115700 to Z.L.B. and M.A.B.). The VIDUS and ACCESS studies were supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health (VIDUS, R01DA011591 and U01DA038886; ACCESS, R01DA021525). This research was undertaken, in part, thanks to funding from the Canada Research Chairs program through a Tier 1 Canada Research Chair in Inner City Medicine which supports Evan Wood. X.T.K. was supported by a Master's Scholarship from the CIHR Small Health Organizations Partnership Program (SHOPP), in partnership with the Canadian Association for HIV Research in partnership with Bristol-Myers Squibb Canada and ViiV Healthcare, and currently holds a CIHR Frederick Banting and Charles Best Canada Graduate Scholarship (doctoral). A.O. was funded by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III (PI12/00529). M.A.B. holds a Canada Research Chair (Tier 2) in Viral Pathogenesis and Immunity from the Canada Research Chairs Program. Z.L.B. was supported by a CIHR New Investigator Award and currently holds a Scholar Award from the Michael Smith Foundation for Health Research.

The funders of this study played no role in determining the content of the manuscript or the authors' decision to publish.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JVI.01955-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaslow RA, Carrington M, Apple R, Park L, Munoz A, Saah AJ, Goedert JJ, Winkler C, O'Brien SJ, Rinaldo C, Detels R, Blattner W, Phair J, Erlich H, Mann DL. 1996. Influence of combinations of human major histocompatibility complex genes on the course of HIV-1 infection. Nat Med 2:405–411. doi: 10.1038/nm0496-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saah AJ, Hoover DR, Weng S, Carrington M, Mellors J, Rinaldo CR Jr, Mann D, Apple R, Phair JP, Detels R, O'Brien S, Enger C, Johnson P, Kaslow RA. 1998. Association of HLA profiles with early plasma viral load, CD4+ cell count and rate of progression to AIDS following acute HIV-1 infection. Multicenter AIDS cohort study. AIDS 12:2107–2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang J, Costello C, Keet IP, Rivers C, Leblanc S, Karita E, Allen S, Kaslow RA. 1999. HLA class I homozygosity accelerates disease progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 15:317–324. doi: 10.1089/088922299311277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrington M, O'Brien SJ. 2003. The influence of HLA genotype on AIDS. Annu Rev Med 54:535–551. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.54.101601.152346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gao X, Bashirova A, Iversen AK, Phair J, Goedert JJ, Buchbinder S, Hoots K, Vlahov D, Altfeld M, O'Brien SJ, Carrington M. 2005. AIDS restriction HLA allotypes target distinct intervals of HIV-1 pathogenesis. Nat Med 11:1290–1292. doi: 10.1038/nm1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pereyra F, Jia X, McLaren PJ, Telenti A, de Bakker PI, Walker BD, Ripke S, Brumme CJ, Pulit SL, Carrington M, Kadie CM, Carlson JM, Heckerman D, Graham RR, Plenge RM, Deeks SG, Gianniny L, Crawford G, Sullivan J, Gonzalez E, Davies L, Camargo A, Moore JM, Beattie N, Gupta S, Crenshaw A, Burtt NP, Guiducci C, Gupta N, Gao X, Qi Y, Yuki Y, Piechocka-Trocha A, Cutrell E, Rosenberg R, Moss KL, Lemay P, O'Leary J, Schaefer T, Verma P, Toth I, Block B, Baker B, Rothchild A, Lian J, Proudfoot J, Alvino DM, Vine S, Addo MM, Allen TM, et al. 2010. The major genetic determinants of HIV-1 control affect HLA class I peptide presentation. Science 330:1551–1557. doi: 10.1126/science.1195271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kiepiela P, Leslie AJ, Honeyborne I, Ramduth D, Thobakgale C, Chetty S, Rathnavalu P, Moore C, Pfafferott KJ, Hilton L, Zimbwa P, Moore S, Allen T, Brander C, Addo MM, Altfeld M, James I, Mallal S, Bunce M, Barber LD, Szinger J, Day C, Klenerman P, Mullins J, Korber B, Coovadia HM, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2004. Dominant influence of HLA-B in mediating the potential co-evolution of HIV and HLA. Nature 432:769–775. doi: 10.1038/nature03113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Naruto T, Gatanaga H, Nelson G, Sakai K, Carrington M, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2012. HLA class I-mediated control of HIV-1 in the Japanese population, in which the protective HLA-B*57 and HLA-B*27 alleles are absent. J Virol 86:10870–10872. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00689-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brumme ZL, John M, Carlson JM, Brumme CJ, Chan D, Brockman MA, Swenson LC, Tao I, Szeto S, Rosato P, Sela J, Kadie CM, Frahm N, Brander C, Haas DW, Riddler SA, Haubrich R, Walker BD, Harrigan PR, Heckerman D, Mallal S. 2009. HLA-associated immune escape pathways in HIV-1 subtype B Gag, Pol and Nef proteins. PLoS One 4:e6687. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tang J, Tang S, Lobashevsky E, Myracle AD, Fideli U, Aldrovandi G, Allen S, Musonda R, Kaslow RA. 2002. Favorable and unfavorable HLA class I alleles and haplotypes in Zambians predominantly infected with clade C human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 76:8276–8284. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8276-8284.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Honeyborne I, Prendergast A, Pereyra F, Leslie A, Crawford H, Payne R, Reddy S, Bishop K, Moodley E, Nair K, van der Stok M, McCarthy N, Rousseau CM, Addo M, Mullins JI, Brander C, Kiepiela P, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2007. Control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is associated with HLA-B*13 and targeting of multiple Gag-specific CD8+ T-cell epitopes. J Virol 81:3667–3672. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02689-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li S, Jiao H, Yu X, Strong AJ, Shao Y, Sun Y, Altfeld M, Lu Y. 2007. Human leukocyte antigen class I and class II allele frequencies and HIV-1 infection associations in a Chinese cohort. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 44:121–131. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000248355.40877.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhai S, Zhuang Y, Song Y, Li S, Huang D, Kang W, Li X, Liao Q, Liu Y, Zhao Z, Lu Y, Sun Y. 2008. HIV-1-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte (CTL) responses against immunodominant optimal epitopes slow the progression of AIDS in China. Curr HIV Res 6:335–350. doi: 10.2174/157016208785132473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jia M, Hong K, Chen J, Ruan Y, Wang Z, Su B, Ren G, Zhang X, Liu Z, Zhao Q, Li D, Peng H, Altfeld M, Walker BD, Yu XG, Shao Y. 2012. Preferential CTL targeting of Gag is associated with relative viral control in long-term surviving HIV-1 infected former plasma donors from China. Cell Res 22:903–914. doi: 10.1038/cr.2012.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzalez-Galarza FF, Takeshita LY, Santos EJ, Kempson F, Maia MH, da Silva AL, Teles e Silva AL, Ghattaoraya GS, Alfirevic A, Jones AR, Middleton D. 2015. Allele frequency net 2015 update: new features for HLA epitopes, KIR and disease and HLA adverse drug reaction associations. Nucleic Acids Res 43:D784–D788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Chui C, Mo T, Wynhoven B, Woods CK, Henrick BM, Hogg RS, Montaner JS, Harrigan PR. 2007. Effects of human leukocyte antigen class I genetic parameters on clinical outcomes and survival after initiation of highly active antiretroviral therapy. J Infect Dis 195:1694–1704. doi: 10.1086/516789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wei Z, Liu Y, Xu H, Tang K, Wu H, Lu L, Wang Z, Chen Z, Xu J, Zhu Y, Hu L, Shang H, Zhao G, Kong X. 2015. Genome-wide association studies of HIV-1 host control in ethnically diverse Chinese populations. Sci Rep 5:10879. doi: 10.1038/srep10879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O'Brien SJ, Gao X, Carrington M. 2001. HLA and AIDS: a cautionary tale. Trends Mol Med 7:379–381. doi: 10.1016/S1471-4914(01)02131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Emu B, Sinclair E, Hatano H, Ferre A, Shacklett B, Martin JN, McCune JM, Deeks SG. 2008. HLA class I-restricted T-cell responses may contribute to the control of human immunodeficiency virus infection, but such responses are not always necessary for long-term virus control. J Virol 82:5398–5407. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02176-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antoni G, Guergnon J, Meaudre C, Samri A, Boufassa F, Goujard C, Lambotte O, Autran B, Rouzioux C, Costagliola D, Meyer L, Theodorou I. 2013. MHC-driven HIV-1 control on the long run is not systematically determined at early times post-HIV-1 infection. AIDS 27:1707–1716. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328360a4bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrer EG, Bergmann S, Eismann K, Rittmaier M, Goldwich A, Muller SM, Spriewald BM, Harrer T. 2005. A conserved HLA B13-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope in Nef is a dominant epitope in HLA B13-positive HIV-1-infected patients. AIDS 19:734–735. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000166099.36638.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yusim K, Korber BTM, Brander C, Haynes BF, Koup R, Moore JP, Walker BD, Watkins DI (ed). 2014. HIV molecular immunology 2014. Theoretical Biology and Biophysics, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Los Alamos, NM: http://www.hiv.lanl.gov/content/immunology/pdf/2014/immuno2014.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martinez-Picado J, Prado JG, Fry EE, Pfafferott K, Leslie A, Chetty S, Thobakgale C, Honeyborne I, Crawford H, Matthews P, Pillay T, Rousseau C, Mullins JI, Brander C, Walker BD, Stuart DI, Kiepiela P, Goulder P. 2006. Fitness cost of escape mutations in p24 Gag in association with control of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 80:3617–3623. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.7.3617-3623.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Crawford H, Prado JG, Leslie A, Hue S, Honeyborne I, Reddy S, van der Stok M, Mncube Z, Brander C, Rousseau C, Mullins JI, Kaslow R, Goepfert P, Allen S, Hunter E, Mulenga J, Kiepiela P, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2007. Compensatory mutation partially restores fitness and delays reversion of escape mutation within the immunodominant HLA-B*5703-restricted Gag epitope in chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 81:8346–8351. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00465-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brockman MA, Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Miura T, Sela J, Rosato PC, Kadie CM, Carlson JM, Markle TJ, Streeck H, Kelleher AD, Markowitz M, Jessen H, Rosenberg E, Altfeld M, Harrigan PR, Heckerman D, Walker BD, Allen TM. 2010. Early selection in Gag by protective HLA alleles contributes to reduced HIV-1 replication capacity that may be largely compensated for in chronic infection. J Virol 84:11937–11949. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01086-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schneidewind A, Brockman MA, Yang R, Adam RI, Li B, Le Gall S, Rinaldo CR, Craggs SL, Allgaier RL, Power KA, Kuntzen T, Tung CS, LaBute MX, Mueller SM, Harrer T, McMichael AJ, Goulder PJ, Aiken C, Brander C, Kelleher AD, Allen TM. 2007. Escape from the dominant HLA-B27-restricted cytotoxic T-lymphocyte response in Gag is associated with a dramatic reduction in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication. J Virol 81:12382–12393. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01543-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prado JG, Honeyborne I, Brierley I, Puertas MC, Martinez-Picado J, Goulder PJ. 2009. Functional consequences of human immunodeficiency virus escape from an HLA-B*13-restricted CD8+ T-cell epitope in p1 Gag protein. J Virol 83:1018–1025. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01882-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boutwell CL, Carlson JM, Lin TH, Seese A, Power KA, Peng J, Tang Y, Brumme ZL, Heckerman D, Schneidewind A, Allen TM. 2013. Frequent and variable cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte escape-associated fitness costs in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype B Gag proteins. J Virol 87:3952–3965. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03233-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang YE, Li B, Carlson JM, Streeck H, Gladden AD, Goodman R, Schneidewind A, Power KA, Toth I, Frahm N, Alter G, Brander C, Carrington M, Walker BD, Altfeld M, Heckerman D, Allen TM. 2009. Protective HLA class I alleles that restrict acute-phase CD8+ T-cell responses are associated with viral escape mutations located in highly conserved regions of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 83:1845–1855. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01061-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brumme ZL, Li C, Miura T, Sela J, Rosato PC, Brumme CJ, Markle TJ, Martin E, Block BL, Trocha A, Kadie CM, Allen TM, Pereyra F, Heckerman D, Walker BD, Brockman MA. 2011. Reduced replication capacity of NL4-3 recombinant viruses encoding reverse transcriptase-integrase sequences from HIV-1 elite controllers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 56:100–108. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181fe9450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brockman MA, Chopera DR, Olvera A, Brumme CJ, Sela J, Markle TJ, Martin E, Carlson JM, Le AQ, McGovern R, Cheung PK, Kelleher AD, Jessen H, Markowitz M, Rosenberg E, Frahm N, Sanchez J, Mallal S, John M, Harrigan PR, Heckerman D, Brander C, Walker BD, Brumme ZL. 2012. Uncommon pathways of immune escape attenuate HIV-1 integrase replication capacity. J Virol 86:6913–6923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.07133-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoon K, Jeong JG, Yoon H, Lee JS, Kim S. 2001. Differential effects of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef sequences on downregulation of CD4 and MHC class I. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 284:638–642. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mwimanzi P, Markle TJ, Martin E, Ogata Y, Kuang XT, Tokunaga M, Mahiti M, Pereyra F, Miura T, Walker BD, Brumme ZL, Brockman MA, Ueno T. 2013. Attenuation of multiple Nef functions in HIV-1 elite controllers. Retrovirology 10:1. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mann JK, Byakwaga H, Kuang XT, Le AQ, Brumme CJ, Mwimanzi P, Omarjee S, Martin E, Lee GQ, Baraki B, Danroth R, McCloskey R, Muzoora C, Bangsberg DR, Hunt PW, Goulder PJ, Walker BD, Harrigan PR, Martin JN, Ndung'u T, Brockman MA, Brumme ZL. 2013. Ability of HIV-1 Nef to downregulate CD4 and HLA class I differs among viral subtypes. Retrovirology 10:100. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ueno T, Motozono C, Dohki S, Mwimanzi P, Rauch S, Fackler OT, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2008. CTL-mediated selective pressure influences dynamic evolution and pathogenic functions of HIV-1 Nef. J Immunol 180:1107–1116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.2.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kuang XT, Li X, Anmole G, Mwimanzi P, Shahid A, Le AQ, Chong L, Qian H, Miura T, Markle T, Baraki B, Connick E, Daar ES, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Little S, Markowitz M, Pereyra F, Rosenberg ES, Walker BD, Ueno T, Brumme ZL, Brockman MA. 2014. Impaired Nef function is associated with early control of HIV-1 Viremia. J Virol 88:10200–10213. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01334-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Garcia JV, Miller AD. 1991. Serine phosphorylation-independent downregulation of cell-surface CD4 by nef. Nature 350:508–511. doi: 10.1038/350508a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwartz O, Marechal V, Le Gall S, Lemonnier F, Heard JM. 1996. Endocytosis of major histocompatibility complex class I molecules is induced by the HIV-1 Nef protein. Nat Med 2:338–342. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carlson JM, Brumme CJ, Martin E, Listgarten J, Brockman MA, Le AQ, Chui CK, Cotton LA, Knapp DJ, Riddler SA, Haubrich R, Nelson G, Pfeifer N, Deziel CE, Heckerman D, Apps R, Carrington M, Mallal S, Harrigan PR, John M, Brumme ZL. 2012. Correlates of protective cellular immunity revealed by analysis of population-level immune escape pathways in HIV-1. J Virol 86:13202–13216. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01998-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin E, Carlson JM, Le AQ, Chopera DR, McGovern R, Rahman MA, Ng C, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Markowitz M, Allen TM, Milloy MJ, Carrington M, Wainberg MA, Brumme ZL. 2014. Early immune adaptation in HIV-1 revealed by population-level approaches. Retrovirology 11:64. doi: 10.1186/s12977-014-0064-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Carlson J, Streeck H, John M, Eichbaum Q, Block BL, Baker B, Kadie C, Markowitz M, Jessen H, Kelleher AD, Rosenberg E, Kaldor J, Yuki Y, Carrington M, Allen TM, Mallal S, Altfeld M, Heckerman D, Walker BD. 2008. Marked epitope- and allele-specific differences in rates of mutation in human immunodeficiency type 1 (HIV-1) Gag, Pol, and Nef cytotoxic T-lymphocyte epitopes in acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Virol 82:9216–9227. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01041-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pond SL, Frost SD, Muse SV. 2005. HyPhy: hypothesis testing using phylogenies. Bioinformatics 21:676–679. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adachi A, Gendelman HE, Koenig S, Folks T, Willey R, Rabson A, Martin MA. 1986. Production of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-associated retrovirus in human and nonhuman cells transfected with an infectious molecular clone. J Virol 59:284–291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brockman MA, Tanzi GO, Walker BD, Allen TM. 2006. Use of a novel GFP reporter cell line to examine replication capacity of CXCR4- and CCR5-tropic HIV-1 by flow cytometry. J Virol Methods 131:134–142. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2005.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miura T, Brockman MA, Brumme ZL, Brumme CJ, Pereyra F, Trocha A, Block BL, Schneidewind A, Allen TM, Heckerman D, Walker BD. 2009. HLA-associated alterations in replication capacity of chimeric NL4-3 viruses carrying Gag-protease from elite controllers of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 83:140–149. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01471-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cotton LA, Kuang XT, Le AQ, Carlson JM, Chan B, Chopera DR, Brumme CJ, Markle TJ, Martin E, Shahid A, Anmole G, Mwimanzi P, Nassab P, Penney KA, Rahman MA, Milloy MJ, Schechter MT, Markowitz M, Carrington M, Walker BD, Wagner T, Buchbinder S, Fuchs J, Koblin B, Mayer KH, Harrigan PR, Brockman MA, Poon AF, Brumme ZL. 2014. Genotypic and functional impact of HIV-1 adaptation to its host population during the North American epidemic. PLoS Genet 10:e1004295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoof I, Peters B, Sidney J, Pedersen LE, Sette A, Lund O, Buus S, Nielsen M. 2009. NetMHCpan, a method for MHC class I binding prediction beyond humans. Immunogenetics 61:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00251-008-0341-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nielsen M, Lundegaard C, Blicher T, Lamberth K, Harndahl M, Justesen S, Roder G, Peters B, Sette A, Lund O, Buus S. 2007. NetMHCpan, a method for quantitative predictions of peptide binding to any HLA-A and -B locus protein of known sequence. PLoS One 2:e796. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Frahm N, Korber BT, Adams CM, Szinger JJ, Draenert R, Addo MM, Feeney ME, Yusim K, Sango K, Brown NV, SenGupta D, Piechocka-Trocha A, Simonis T, Marincola FM, Wurcel AG, Stone DR, Russell CJ, Adolf P, Cohen D, Roach T, StJohn A, Khatri A, Davis K, Mullins J, Goulder PJ, Walker BD, Brander C. 2004. Consistent cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte targeting of immunodominant regions in human immunodeficiency virus across multiple ethnicities. J Virol 78:2187–2200. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.5.2187-2200.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akari H, Arold S, Fukumori T, Okazaki T, Strebel K, Adachi A. 2000. Nef-induced major histocompatibility complex class I down-regulation is functionally dissociated from its virion incorporation, enhancement of viral infectivity, and CD4 down-regulation. J Virol 74:2907–2912. doi: 10.1128/JVI.74.6.2907-2912.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bartz SR, Vodicka MA. 1997. Production of high-titer human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pseudotyped with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein. Methods 12:337–342. doi: 10.1006/meth.1997.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Birkholz K, Hofmann C, Hoyer S, Schulz B, Harrer T, Kampgen E, Schuler G, Dorrie J, Schaft N. 2009. A fast and robust method to clone and functionally validate T-cell receptors. J Immunol Methods 346:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anmole G, Kuang X, Toyoda M, Martin E, Shahid A, Le A, Markle T, Baraki B, Jones B, Ostrowski M, Ueno T, Brumme Z, Brockman M. 28 August 2015. A robust and scalable TCR-based reporter cell assay to measure HIV-1 Nef-mediated T cell immune evasion. J Immunol Methods. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shugars DC, Smith MS, Glueck DH, Nantermet PV, Seillier-Moiseiwitsch F, Swanstrom R. 1993. Analysis of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 nef gene sequences present in vivo. J Virol 67:4639–4650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Draenert R, Le Gall S, Pfafferott KJ, Leslie AJ, Chetty P, Brander C, Holmes EC, Chang SC, Feeney ME, Addo MM, Ruiz L, Ramduth D, Jeena P, Altfeld M, Thomas S, Tang Y, Verrill CL, Dixon C, Prado JG, Kiepiela P, Martinez-Picado J, Walker BD, Goulder PJ. 2004. Immune selection for altered antigen processing leads to cytotoxic T lymphocyte escape in chronic HIV-1 infection. J Exp Med 199:905–915. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pohlmeyer CW, Buckheit RW III, Siliciano RF, Blankson JN. 2013. CD8+ T cells from HLA-B*57 elite suppressors effectively suppress replication of HIV-1 escape mutants. Retrovirology 10:152. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-10-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sette A, Vitiello A, Reherman B, Fowler P, Nayersina R, Kast WM, Melief CJ, Oseroff C, Yuan L, Ruppert J, Sidney J, del Guercio MF, Southwood S, Kubo RT, Chesnut RW, Grey HM, Chisari FV. 1994. The relationship between class I binding affinity and immunogenicity of potential cytotoxic T cell epitopes. J Immunol 153:5586–5592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kirchhoff F, Easterbrook PJ, Douglas N, Troop M, Greenough TC, Weber J, Carl S, Sullivan JL, Daniels RS. 1999. Sequence variations in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 Nef are associated with different stages of disease. J Virol 73:5497–5508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wildum S, Schindler M, Munch J, Kirchhoff F. 2006. Contribution of Vpu, Env, and Nef to CD4 down-modulation and resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected T cells to superinfection. J Virol 80:8047–8059. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00252-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verheyen J, Schweitzer F, Harrer EG, Knops E, Mueller SM, Daumer M, Eismann K, Bergmann S, Spriewald BM, Kaiser R, Harrer T. 2010. Analysis of immune selection as a potential cause for the presence of cleavage site mutation 431V in treatment-naive HIV type-1 isolates. Antivir Ther 15:907–912. doi: 10.3851/IMP1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schindler M, Wurfl S, Benaroch P, Greenough TC, Daniels R, Easterbrook P, Brenner M, Munch J, Kirchhoff F. 2003. Down-modulation of mature major histocompatibility complex class II and up-regulation of invariant chain cell surface expression are well-conserved functions of human and simian immunodeficiency virus nef alleles. J Virol 77:10548–10556. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.19.10548-10556.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Munch J, Rajan D, Schindler M, Specht A, Rucker E, Novembre FJ, Nerrienet E, Muller-Trutwin MC, Peeters M, Hahn BH, Kirchhoff F. 2007. Nef-mediated enhancement of virion infectivity and stimulation of viral replication are fundamental properties of primate lentiviruses. J Virol 81:13852–13864. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00904-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abraham L, Fackler OT. 2012. HIV-1 Nef: a multifaceted modulator of T cell receptor signaling. Cell Commun Signal 10:39. doi: 10.1186/1478-811X-10-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajapaksa US, Li D, Peng YC, McMichael AJ, Dong T, Xu XN. 2012. HLA-B may be more protective against HIV-1 than HLA-A because it resists negative regulatory factor (Nef) mediated down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 109:13353–13358. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204199109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tomiyama H, Fujiwara M, Oka S, Takiguchi M. 2005. Cutting edge: epitope-dependent effect of Nef-mediated HLA class I down-regulation on ability of HIV-1-specific CTLs to suppress HIV-1 replication. J Immunol 174:36–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Adnan S, Balamurugan A, Trocha A, Bennett MS, Ng HL, Ali A, Brander C, Yang OO. 2006. Nef interference with HIV-1-specific CTL antiviral activity is epitope specific. Blood 108:3414–3419. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-030668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Chen DY, Balamurugan A, Ng HL, Cumberland WG, Yang OO. 2012. Epitope targeting and viral inoculum are determinants of Nef-mediated immune evasion of HIV-1 from cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Blood 120:100–111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-409870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sacha JB, Chung C, Rakasz EG, Spencer SP, Jonas AK, Bean AT, Lee W, Burwitz BJ, Stephany JJ, Loffredo JT, Allison DB, Adnan S, Hoji A, Wilson NA, Friedrich TC, Lifson JD, Yang OO, Watkins DI. 2007. Gag-specific CD8+ T lymphocytes recognize infected cells before AIDS-virus integration and viral protein expression. J Immunol 178:2746–2754. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mangasarian A, Piguet V, Wang JK, Chen YL, Trono D. 1999. Nef-induced CD4 and major histocompatibility complex class I (MHC-I) down-regulation are governed by distinct determinants: N-terminal alpha helix and proline repeat of Nef selectively regulate MHC-I trafficking. J Virol 73:1964–1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hua J, Blair W, Truant R, Cullen BR. 1997. Identification of regions in HIV-1 Nef required for efficient downregulation of cell surface CD4. Virology 231:231–238. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Poe JA, Smithgall TE. 2009. HIV-1 Nef dimerization is required for Nef-mediated receptor downregulation and viral replication. J Mol Biol 394:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kwak YT, Raney A, Kuo LS, Denial SJ, Temple BR, Garcia JV, Foster JL. 2010. Self-association of the lentivirus protein, Nef. Retrovirology 7:77. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.O'Neill E, Kuo LS, Krisko JF, Tomchick DR, Garcia JV, Foster JL. 2006. Dynamic evolution of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 pathogenic factor, Nef. J Virol 80:1311–1320. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.3.1311-1320.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jia X, Singh R, Homann S, Yang H, Guatelli J, Xiong Y. 2012. Structural basis of evasion of cellular adaptive immunity by HIV-1 Nef. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:701–706. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Adland E, Carlson JM, Paioni P, Kloverpris H, Shapiro R, Ogwu A, Riddell L, Luzzi G, Chen F, Balachandran T, Heckerman D, Stryhn A, Edwards A, Ndung'u T, Walker BD, Buus S, Goulder P, Matthews PC. 2013. Nef-specific CD8+ T cell responses contribute to HIV-1 immune control. PLoS One 8:e73117. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0073117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.