Abstract

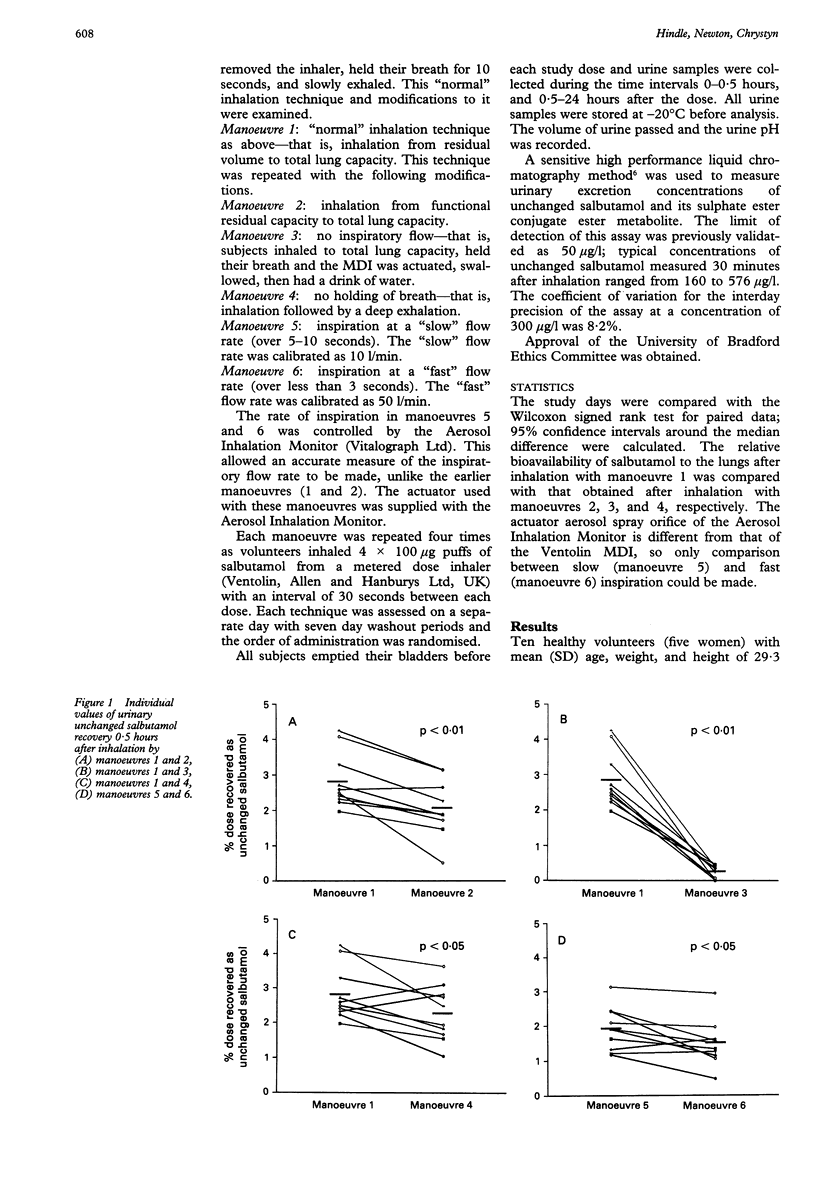

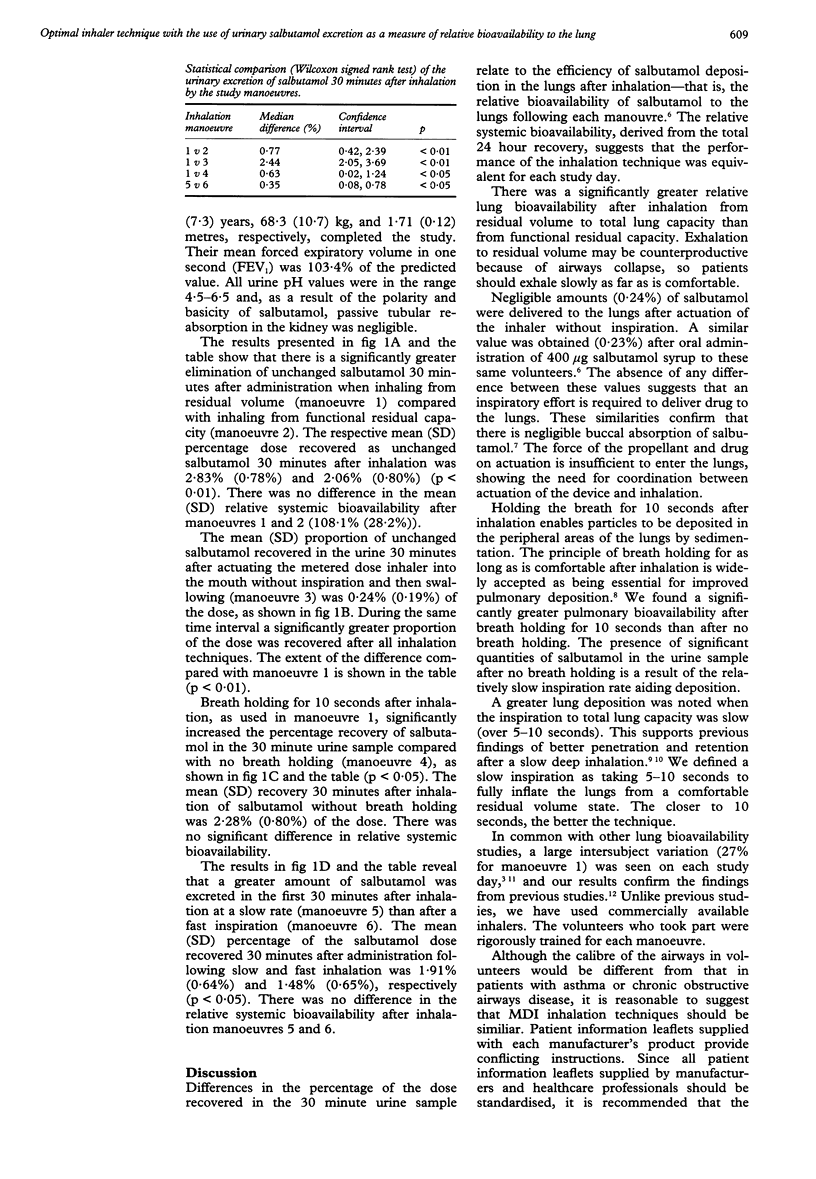

BACKGROUND--A simple non-invasive method, in which a urine sample is taken 30 minutes after drug administration, has previously been shown to be a measure of the relative bioavailability of salbutamol to the lungs. This technique has been used to determine an optimal inhaler technique with commercially available metered dose inhalers (MDI). METHODS--Ten healthy subjects were trained in the use of MDIs. Each inhaled 4 x 100 micrograms salbutamol in a series of experiments to examine the relative bioavailability to the lung after different respiratory manoeuvres. Urine collection intervals were 0-0.5 hours and 0.5-24 hours after administration. RESULTS--There was significantly greater elimination of unchanged salbutamol 30 minutes after administration, indicating a greater relative bioavailability of salbutamol to the lungs after (1) exhaling gently to residual volume rather than to functional residual capacity before inhalation; (2) slow inhalation (10 l/min) compared with fast inhalation (50 l/min); (3) breath holding for 10 seconds after inhalation compared with no breath holding. CONCLUSIONS--All patient information leaflets and healthcare personnel should standardise the instructions given to patients and should adopt the inhalation method proposed.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Borgström L., Nilsson M. A method for determination of the absolute pulmonary bioavailability of inhaled drugs: terbutaline. Pharm Res. 1990 Oct;7(10):1068–1070. doi: 10.1023/a:1015951402799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies D. S. The fate of inhaled terbutaline. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1984;134:141–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hindle M., Chrystyn H. Determination of the relative bioavailability of salbutamol to the lung following inhalation. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1992 Oct;34(4):311–315. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1992.tb05921.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipworth B. J., Clark R. A., Dhillon D. P., Moreland T. A., Struthers A. D., Clark G. A., McDevitt D. G. Pharmacokinetics, efficacy and adverse effects of sublingual salbutamol in patients with asthma. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;37(6):567–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00562546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. P., Pavia D., Clarke S. W. How should a pressurized beta-adrenergic bronchodilator be inhaled? Eur J Respir Dis. 1981 Feb;62(1):3–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. P., Pavia D., Garland N., Clarke S. W. Effects of various inhalation modes on the deposition of radioactive pressurized aerosols. Eur J Respir Dis Suppl. 1982;119:57–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. P., Pavia D., Morén F., Sheahan N. F., Clarke S. W. Deposition of pressurised aerosols in the human respiratory tract. Thorax. 1981 Jan;36(1):52–55. doi: 10.1136/thx.36.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmes E. D., Wang C. S., Goldring R. M., Altshuler B. Effect of depth of inhalation on aerosol persistence during breath holding. J Appl Physiol. 1973 Mar;34(3):356–360. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1973.34.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson I. C., Crompton G. K. Use of pressurised aerosols by asthmatic patients. Br Med J. 1976 Jan 10;1(6001):76–77. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.6001.76-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavia D., Thomson M., Shannon H. S. Aerosol inhalation and depth of deposition in the human lung. The effect of airway obstruction and tidal volume inhaled. Arch Environ Health. 1977 May-Jun;32(3):131–137. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1977.10667269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]