Abstract

Introduction:

Fourth-generation HIV-1 rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) detect HIV-1 p24 antigen to screen for acute HIV-1. However, diagnostic accuracy during clinical use may be suboptimal.

Methods:

Clinical sensitivity and specificity of fourth-generation RDTs for acute HIV-1 were collated from field evaluation studies in adults identified by a systematic literature search.

Results:

Four studies with 17 381 participants from Australia, Swaziland, the United Kingdom and Malawi were identified. All reported 0% sensitivity of the HIV-1 p24 component for acute HIV-1 diagnosis; 26 acute infections were missed. Specificity ranged from 98.3 to 99.9%.

Conclusion:

Fourth-generation RDTs are currently unsuitable for the detection of acute HIV-1.

Keywords: acute infection, diagnostic accuracy, HIV, point-of-care testing, rapid diagnostic tests, systematic review

Introduction

An estimated 5–20% of HIV infections are due to transmission from recently infected individuals [1], although this depends on epidemic characteristics [2,3]. Diagnosing HIV in the weeks after an individual has acquired infection is likely to be critical to epidemic control as prompt diagnosis allows early entry into care and treatment, reducing the risk of onward transmission. Laboratory diagnosis relies on the appearance of HIV antigen (e.g. HIV-1 p24 antigen) or nucleic acid in the bloodstream prior to detectable antibodies to HIV-1/2, but testing procedures can be burdensome. Easy-to-use and accurate in-vitro diagnostics for detection of acute HIV infection that can be used at point of care are required to realize the potential public health benefits of early diagnosis, especially in resource-limited settings wherein the large majority of HIV transmissions occur.

New fourth-generation point-of-care rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for HIV-1 detect HIV-1 p24 antigenaemia as well as antibodies to HIV-1/2. They have the potential to meet these requirements, and have been approved for their sale in many settings. However, the sensitivity of the p24 antigen component has been variable (2–92%) in laboratory evaluations on banked panels of specimens [4–9] leading to concerns that this may translate into poor diagnostic accuracy in the field for the diagnosis of acute HIV-1 [10]. We therefore performed a systematic review to assess the field accuracy of fourth-generation RDTs for the diagnosis of acute HIV-1 in clinical practice.

Methods

In accordance with our published protocol [11], we systematically searched Medline (using PubMed) and ISI Web of Science for studies published between 1 January 2005 and 22 April 2015 that evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of fourth-generation RDTs for acute HIV-1 (Supplementary Table 1: Search Strategy). Studies were eligible if they evaluated the field performance of at least one fourth-generation RDT for acute HIV-1 in adults (aged >15 years). We defined field performance as the RDT being used on an unselected population, at the point of care (defined as being conducted in the presence of the patient [12]), in the setting of intended use and carried out by the intended user. Cross-sectional studies, cohort studies and randomized control trials were included. Studies that evaluated fourth-generation RDTs within laboratories or retrospectively against specimen panels were excluded. We placed no restrictions on assay manufacturer, language or country.

Two reviewers (P.M., E.A.) independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of all studies against inclusion and exclusion criteria, with discrepancies resolved by group decision with a third reviewer (M.T.). Two reviewers (J.L., P.M.) independently reviewed the full text of all selected studies using a piloted data extraction form to determine final selection status. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by group decision with a third reviewer (M.T.). Participants receiving the index test were defined as true positive, false positive, false negative and true negative for the presence of a positive HIV-1 p24 antigen reaction on the fourth-generation HIV RDT compared with the study-defined reference standard for acute HIV-1 infection. We recognized that there is no current consensus reference standard for the diagnosis of acute HIV infection and specified that an acceptable reference standard for the diagnosis of acute HIV-1 infection would include at least one nonreactive antibody test result using a third-generation HIV immunoassay, and at least one reactive antigen test result on a fourth-generation HIV immunoassay, and/or at least one reactive result using an HIV-1 p24 antigen immunoassay. However, where this was not used, we used study-reported reference standards. Details of studies excluded after full-text review are shown in the supplementary appendix (Supplementary Table 2) [5–9,13–37].

Risk of bias in the included studies was independently assessed by two reviewers (J.L. and P.M.) using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS 2) tool [38] with signalling questions used across four domains (selection, index test conduct, reference standard conduct and participant flow and timing) to assess overall risk of bias.

Study flow and results are reported in accordance with the Standards for Reporting of Diagnostic Accuracy (STARD) checklist [39]. Given the high degree of heterogeneity in study populations and conduct, we did not perform meta-analysis, but would have done so if results had indicated this to be appropriate.

Results

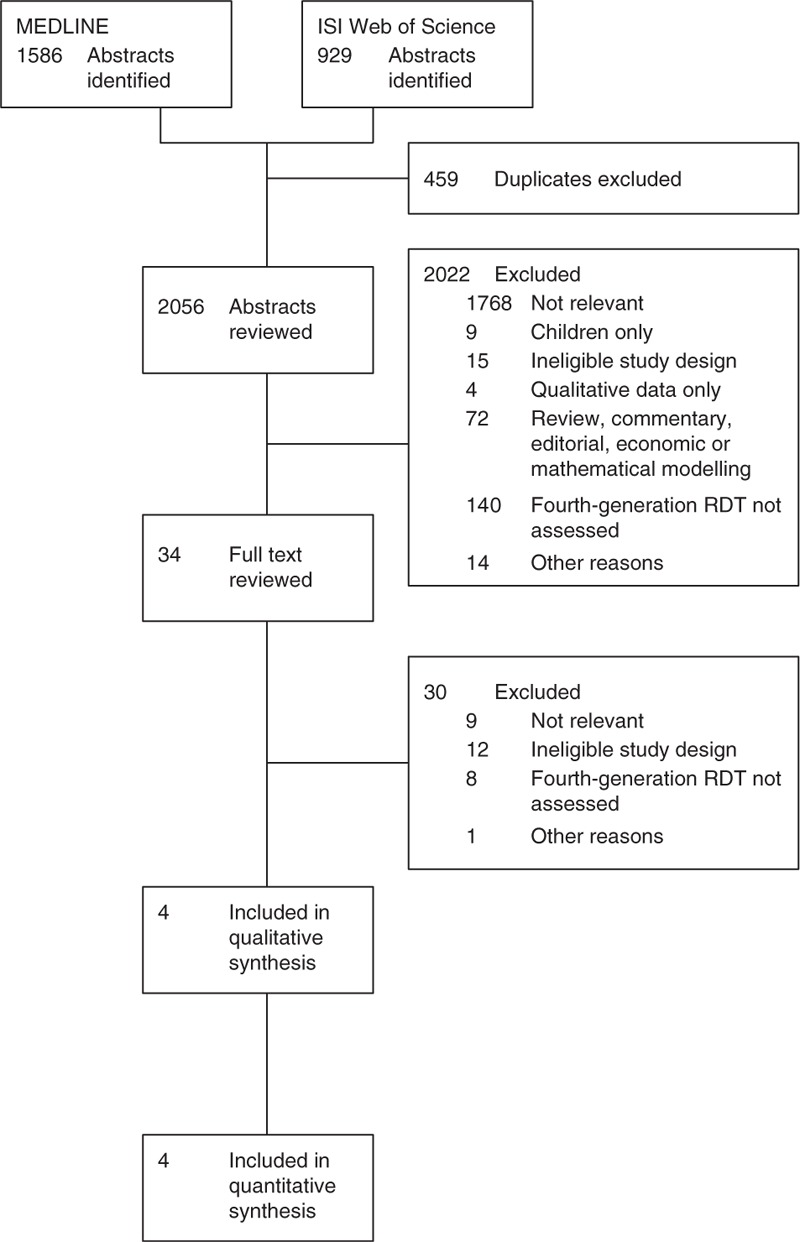

Of 2056 unique studies identified, four met inclusion criteria and contributed data relating to 17 381 participants to this analysis (Fig. 1). Studies came from Swaziland [40], Malawi [41], Australia [42] and the United Kingdom [43] (Table 1). Three studies included community members [41], MSM [42] or IDUs [43] attending specialist sexually transmitted diseases or HIV testing clinics, whereas in the fourth, participants were recruited from a national HIV incidence survey [40]. All had a cross-sectional study design.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of included and excluded studies.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies investigating diagnostic accuracy of fourth-generation HIV rapid diagnostic tests.

| Study | Countries | Study population | Proportion men | Reference standard for diagnosis | True positive | False positive | False negative | True negative | Sensitivity (95% CI) | Specificity (95% CI) |

| Conway et al., 2014 [42] | Australia | Adult (≥18 years old) MSM attending STD clinics in four suburbs | 100% | Algorithm comprising of: | 0 | 6 | 3 | 3181 | 0.00b | 0.998b |

| Fourth-generation immunoassay (Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo or Elecsys HIV Combi PT) – All participants | ||||||||||

| Supplementary antibody immunoassay (Serodia HIV-1 Antibody particle agglutination assay or Genscreen HIV 1&2 Antibody EIA) – If index test antigen or antibody reactive | ||||||||||

| HIV p24 antigen immunoassay (Genscreen HIV-1 p24 Antigen) – If index test antigen or antibody reactive | ||||||||||

| HIV Western blot (HIV Western Blot 2.2, MP Diagnostics) – If index test antigen or antibody reactive | ||||||||||

| Duong et al., 2014 [40] | Swaziland | Adult (18–49 years old) community members participating in a national HIV incidence survey | 39% | Algorithm comprising of: | 0 | 12 | 13 | 12 345 | 0.00 (0–0.23) | 0.999 (0.998–0.999) |

| Third-generation RDT (Uni-Gold Recombigen) – Index test antibody reactive | ||||||||||

| Fourth-generation RDT (Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo) – Index test antigen reactive | ||||||||||

| HIV viral load quantification (COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan) – Index test antigen reactive | ||||||||||

| Pooled (with deconstruction and individual retesting if detected) HIV viral load quantification (COBAS AmpliPrep/COBAS TaqMan) – Index test antigen and antibody nonreactive | ||||||||||

| Jones et al., 2012 [43] | United Kingdom | Adult (≥18 years old) MSM, IDUs, individuals from high-prevalence settings and at-risk partners attending STD clinic in London | 87% | Algorithm comprising of: | 0 | 3 | 2 | 980 | 0.00b | 0.997b |

| Third-generation RDT (Determine HIV-1/2) – All participants | ||||||||||

| Fourth-generation immunoassay (Architect HIV Ag/Ab Combo) – All participants | ||||||||||

| Fourth-generation immunoassay (VIDAS platform, assay not specified) – Index test reactive | ||||||||||

| Rosenberg et al., 2012 [41] | Malawi | Adults (18–49 years old) attending hospital STDa and HIV testing clinics in Lilongwe | STD: 65% | Third-generation RDT (Uni-Gold Recombigen, SD Bioline HIV 1/2 3.0) – All participants | 0 | 14 | 8 | 824 | 0.00 (0.00–0.37) | 0.983 (0.972–0.991) |

| HTC: 52% | HIV viral load quantification (Roche Monitor) – Participants with nonreactive or discrepant HIV antibody RDT results |

CI, confidence interval; HTS, HIV testing services; NR, not reported; PWID, people who inject drugs; RDT, rapid diagnostic test; STIs, sexually transmitted infections. True positive/false positive/true negative/false negative all refer to p24 antigen strip of index test.

aOnly patients with negative or discrepant HIV RDTs results at high risk for acute HIV infection attending STD clinic were invited to participate.

b95% CIs not reported.

All four studies evaluated the diagnostic accuracy of Alere Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Alere Medical Co. Ltd., Chiba, Japan), hereafter described as the index test. This is a fourth-generation RDT that can detect antibody to HIV-1/2 and HIV-1 p24 antigen. Only two studies used reference standards as defined in our study protocol [42,43], with the other two studies variously using laboratory-performed testing algorithms for characterization of acute HIV comprising of a third-generation RDT, a fourth-generation RDT and HIV quantitative nucleic acid testing (NAT) technology (HIV viral load) for participants with a reactive HIV-1 p24 antigen index test result [40], and a third-generation RDT (all participants) and HIV viral load quantification (participants with nonreactive or discrepant antibody index test results) [41].

In all four studies, sensitivity of the HIV-1 p24 antigen component of the index test for reference standard-classified acute HIV infection was 0%, with a total of 26 acute HIV infections missed (Table 1). Specificity of HIV-1 p24 antigen component of the index test for acute HIV infection was similar across all studies (98.3–99.9%); a total of 35 false-positive results were observed. It was possible to extract data on the accuracy of the antibody component of the index test from two of the four studies; in the first, the antibody component detected zero of three (0%) acute HIV infections [42]; in the second, two of eight (25%) [41].

The risk of bias in these studies as assessed across the four assessed domains was largely low or unclear. Only in one domain of one study was there a high risk of bias: in patient selection; in this study, a nonconsecutive, nonrandom cohort of patients were enrolled – only patients who were assessed as high risk for acute HIV infection [41]. The full assessment of risk of bias is shown in the supplementary appendix (Supplementary Table 3).

Discussion

This systematic review reveals unacceptably low-field sensitivity in the diagnosis of acute HIV-1 of the p24 antigen component of Determine HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Alere Medical Co. Ltd, Chiba, Japan) – the only product evaluated in the included studies – with not a single true positive for acute infection detected in over 17 000 individuals from at-risk groups in sub-Saharan Africa, Australia and the United Kingdom. Across these studies, 26 reference-standard-defined acute HIV infections were missed, and 35 false positives were observed. On the basis of these findings, we recommend that Determine HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo (Alere Medical Co. Ltd) is not currently used for screening for acute HIV-1 infection at the point of care.

There are a number of likely reasons for the poor test performance. The assay detects free HIV-1 p24 antigen; this has a short window of detection, before developing antibodies from immune complexes with antigen in the bloodstream and preclude binding of antigen to the test strip. This technical difficulty can be overcome with an antigen dissociation step [44], but this may be hard to implement at the point of care. Differential affinity of binding to different HIV subtypes could also contribute to poor detection of HIV-1 p24 antigen.

We excluded a number of studies as they did not meet our inclusion criteria. The majority were not field evaluations but rather evaluations in reference laboratory settings on specimen panels. Of those studies that did perform a field evaluation, but were excluded from this review, the reference and/or index test(s) were often inconsistently applied across all patients making evaluation of true sensitivity and specificity impossible. This likely represents the inherent difficulty in designing a study to assess an in-vitro diagnostic for acute HIV infection, which is rare even in areas of high HIV prevalence and has a short timeframe for detection.

The lack of a consistent application of a clinical definition of acute HIV-1 infection makes it challenging to compare results across studies and compare diagnostic accuracy. The included studies defined acute HIV-1 infection using a variety of biomarkers and clinical parameters. In laboratory terms, acute HIV-1 infection has been clearly defined in terms of the Fiebig stages of acute HIV-1 infection, characterized by sequential appearance of HIV-1 nucleic acid, HIV-1 p24 antigen followed by immunoglobulin M and then immunoglobulin G antibodies to HIV-1 [45]. These stages were originally defined using second and third-generation immunoassays and attempts have been made to redefine these stages in terms of more modern third and fourth-generation assays [46]. Regardless of the existence of these clear laboratory definitions, we found that clinical definitions of acute HIV-1 are inconsistently applied across studies. Internationally agreed and applied consensus definitions of acute HIV infection for use in clinical studies would go some considerable way to clarifying a confusing field.

Despite a comprehensive literature search and rigorous analysis, there are some limitations to our study: data may be reported as supplementary material, and have been missed by our search; only adults were included. Owing to the small number of studies identified, and high degree of heterogeneity in study settings and populations, it was inappropriate to undertake meta-analysis, meaning that overall summary estimates for diagnostic accuracy cannot be made. All studies assessed the accuracy of only one fourth-generation RDT; others are available [e.g. SD Bioline HIV Ag/Ab (Standard Diagnostics, Inc., Giheung-gu, Republic of Korea) and ImmunoComb II HIV 1&2 TriSpot Ag-Ab (Orgenics Ltd, Yavne, Israel)]. The generalizability of our results are unclear but it seems likely that the same technical difficulties will affect other fourth-generation RDTs [47], and clinicians should interpret the results of HIV-1 RDT antigen testing with caution.

In conclusion, the fourth-generation RDT for HIV that was the subject of this systematic review has low sensitivity for detection of acute HIV-1, and is unsuitable for this purpose. Point-of-care options for diagnosis of acute HIV-1 are therefore currently limited to third-generation RDTs alongside careful assessment of timing of exposure and serial testing, with a continuing need for laboratory support for antigen testing or NAT wherein the suspicion of acute HIV infection is high. New approaches to diagnosis of acute HIV such as point-of-care testing with third-generation RDT exhibiting best possible seroconversion sensitivity, or NAT – including the prospect of expansion of qualitative NAT platforms for use at point of care that have been developed for early infant diagnosis – need evaluating in the field against agreed definitions of acute HIV in order to realize the public health benefits of making this important diagnosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Indo Sachiko for translation of one manuscript from Japanese to English. Joseph Lewis is financially supported by the Wellcome Trust as a Wellcome Trust funded clinical PhD fellow (grant number 109105/Z/15/Z).

Author contributions: P.M., E.A., E.O., A.S. and M.T. conceived the idea and developed the protocol. J.L., P.M., E.A. and M.T. performed the systematic review and data extraction. J.L. wrote the manuscript. All authors redrafted and approved the final manuscript.

Sources of funding: none.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Cohen MS, Shaw GM, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Acute HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:1943–1954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellan SE, Dushoff J, Galvani AP, Meyers LA. Reassessment of HIV-1 acute phase infectivity: accounting for heterogeneity and study design with simulated cohorts. PLoS Med 2015; 12:e1001801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abu-Raddad LJ. Role of acute HIV infection in driving HIV transmission: implications for HIV treatment as prevention. PLoS Med 2015; 12:e1001803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beelaert G, Fransen K. Evaluation of a rapid and simple fourth-generation HIV screening assay for qualitative detection of HIV p24 antigen and/or antibodies to HIV-1 and HIV-2. J Virol Methods 2010; 168:218–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brauer M, De Villiers JC, Mayaphi SH. Evaluation of the DetermineTM fourth generation HIV rapid assay. J Virol Methods 2013; 189:180–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eller LA, Manak M, Shutt A, Malia J, Trichavaroj R, Danboise B, et al. Performance of the Determine HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo Rapid Test on Serial Samples from an Acute Infection Study (RV217) in East Africa and Thailand. Aids vaccine Conf 2013; 7–10 October, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fox J, Dunn H, O'Shea S. Low rates of p24 antigen detection using a fourth-generation point of care HIV test. Sex Transm Infect 2011; 87:178–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kilembe W, Keeling M, Karita E, Lakhi S, Chetty P, Price MA, et al. Failure of a novel, rapid antigen and antibody combination test to detect antigen-positive HIV infection in African adults with early HIV infection. PLoS One 2012; 7:e37154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laperche S, Leballais L, Ly TD, Plantier JC. Failures in the detection of HIV p24 antigen with the Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo rapid test. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1946–1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alere Limited. Urgent Field Safety Notice: Alere Determine HIV 1/2 Ag/Ab Combo. Waltham, MA, USA; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis J, Machpherson P, Adams E, Ochodo E, Sands A, Taegtmeyer M. Field accuracy of 4th generation rapid diagnostic tests for acute HIV: a systematic review. PROSPERO Int Prospect Regist Syst Rev 2014; CRD42014010206. http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42014010206 [Accessed 01 April 2015].. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drain PK, Hyle EP, Noubary F, Freedberg KA, Wilson D, Bishai WR, et al. Diagnostic point-of-care tests in resource-limited settings. Lancet Infect Dis 2014; 14:239–249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belza MJ, Rosales-Statkus ME, Hoyos J, Segura P, Ferreras E, Sánchez R, et al. Supervised blood-based self-sample collection and rapid test performance: a valuable alternative to the use of saliva by HIV testing programmes with no medical or nursing staff. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88:218–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bhowan K, Kalk E, Khan S, Sherman G. Identifying HIV infection in South African women: how does a fourth generation HIV rapid test perform?. Afr J Lab Med 2011; 1:1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chetty V, Moodley D, Chuturgoon A. Evaluation of a 4th generation rapid HIV test for earlier and reliable detection of HIV infection in pregnancy. J Clin Virol 2012; 54:180–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.d’Almeida KW, Kierzek G, de Truchis P, Le Vu S, Pateron D, Renaud B, et al. Modest public health impact of nontargeted human immunodeficiency virus screening in 29 emergency departments. Arch Intern Med 2012; 172:12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De la Fuente L, Rosales-Statkus ME, Hoyos J, Pulido J, Santos S, Bravo MJ, et al. Are participants in a street-based HIV testing program able to perform their own rapid test and interpret the results?. PLoS One 2012; 7:e46555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fitzpatrick F, Kaminski G, Jones L, Drudy E, Crean M. Use of a fourth generation HIV assay for routine screening: the first year's experience. J Infect 2006; 53:415–416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goodhue T, Kazianis A, Werner BG, Stiles T, Callis BP, Dawn Fukuda H, et al. 4th generation HIV screening in Massachusetts: a partnership between laboratory and program. J Clin Virol 2013; 58 Suppl 1:e13–e18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kagulire SC, Opendi P, Stamper PD, Nakavuma JL, Mills LA, Makumbi F, et al. Field evaluation of five rapid diagnostic tests for screening of HIV-1 infections in rural Rakai, Uganda. Int J STD AIDS 2011; 22:308–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kannangai R, Moorthy M, Kandathil AJ, Sachithanandham J, Thirupavai V, Nithyanandam G, et al. Experience with a fourth generation human immunodeficiency virus serological assay at a tertiary care centre in south India. Indian J Med Microbiol 2008; 26:200–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khanom A, Hurday S, Holmes M, Chaytor S, Evans A, Garcia A, et al. Evaluation of third- and fourth-generation point-of-care tests for the detection of HIV. HIV Med 2013; 14 Suppl 2:12–77. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee E, Lee J, Park Y, Seok Y, Kim H, Hong D, et al. Clinical experience of fourth-generation HIV Ag/Ab Combo Test as a screening tool in a low-prevalence area. J Mol Diagnostics 2010; 12:890. [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacPherson P, Chawla A, Jones K, Coffey E, Spaine V, Harrison I, et al. Feasibility and acceptability of point of care HIV testing in community outreach and GUM drop-in services in the North West of England: a programmatic evaluation. BMC Public Health 2011; 11:419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masciotra S, Luo W, Youngpairoj AS, Kennedy MS, Wells S, Ambrose K, et al. Performance of the Alere DetermineTM HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo Rapid Test with specimens from HIV-1 seroconverters from the US and HIV-2 infected individuals from Ivory Coast. J Clin Virol 2013; 58 Suppl 1:e54–e58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Monari M, Valaperta S, Assandri R, Montanelli A. Analytical performance of a new point-of-care test for HIV 1-2 Ag/Ab selective and combined detection. Infection 2010; 38 Suppl I:91. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mungrue K, Sahadool S, Evans R, Boochay S, Ragoobar F, Maharaj K, et al. Assessing the HIV rapid test in the fight against the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Trinidad. HIV AIDS (Auckl) 2013; 5:191–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naylor E, Axten D, Makia F, Tong C, White J, Fox J. Fourth generation point of care testing for HIV: validation in an HIV-positive population. Sex Transm Infect 2011; 87:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel P, Bennett B, Sullivan T, Parker MM, Heffelfinger JD, Sullivan PS. Rapid HIV screening: missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis and prevention. J Clin Virol 2012; 54:42–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pilcher CD, Louie B, Facente S, Keating S, Hackett J, Vallari A, et al. Performance of rapid point-of-care and laboratory tests for acute and established HIV infection in San Francisco. PLoS One 2013; 8:e80629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rezel E, Walker C, Collins S. 4th generation (Ag/Ab) HIV testing: 47% of clinics contradict current guidelines. HIV Med 2012; 13 Suppl 1:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanders EJ, Mugo P, Prins HB, Wahome E, Thiong’o AN, Mwashigadi G, et al. Acute HIV-1 infection is as common as malaria in young febrile adults seeking care in coastal Kenya. AIDS 2014; 28:1357–1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sarna A, Saraswati LR, Sebastian M, Sharma V, Madan I, Lewis D, et al. High HIV incidence in a cohort of male injection drug users in Delhi, India. Drug Alcohol Depend 2014; 139:106–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stekler JD, Swenson PD, Coombs RW, Dragavon J, Thomas KK, Brennan CA, et al. HIV testing in a high-incidence population: is antibody testing alone good enough?. Clin Infect Dis 2009; 49:444–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stekler JD, O’Neal JD, Lane A, Swanson F, Maenza J, Stevens CE, et al. Relative accuracy of serum, whole blood, and oral fluid HIV tests among Seattle men who have sex with men. J Clin Virol 2013; 58 Suppl 1:e119–e122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Taegtmeyer M, MacPherson P, Jones K, Hopkins M, Moorcroft J, Lalloo DG, et al. Programmatic evaluation of a combined antigen and antibody test for rapid HIV diagnosis in a community and sexual health clinic screening programme. PLoS One 2011; 6:e28019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wouters K, Fransen K, Beelaert G, Kenyon C, Platteau T, Van Ghyseghem C, et al. Use of rapid HIV testing in a low threshold centre in Antwerp, Belgium, 2007-2012. Int J STD AIDS 2014; 25:936–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med 2011; 155:529–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig LM, et al. Towards complete and accurate reporting of studies of diagnostic accuracy: the STARD initiative. BMJ 2003; 326:41–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Duong YT, Mavengere Y, Patel H, Moore C, Manjengwa J, Sibandze D, et al. Poor performance of the determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combo fourth-generation rapid test for detection of acute infections in a National Household Survey in Swaziland. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52:3743–3748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rosenberg NE, Kamanga G, Phiri S, Nsona D, Pettifor A, Rutstein SE, et al. Detection of acute HIV infection: a field evaluation of the determine( HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab combo test. J Infect Dis 2012; 205:528–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conway DP, Holt M, McNulty A, Couldwell DL, Smith DE, Davies SC, et al. Multi-centre evaluation of the Determine HIV Combo Assay when used for point of care testing in a high risk clinic-based population. PLoS One 2014; 9:e94062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones CB, Kuldanek K, Muir D, Phekoo K, Black A, Sacks R, et al. Clinical evaluation of the Determine HIV-1/2 Ag/Ab Combo test. J Infect Dis 2012; 206:1947–1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schüpbach J, Böni J. Quantitative and sensitive detection of immune-complexed and free HIV antigen after boiling of serum. J Virol Methods 1993; 43:247–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg NE, Pilcher CD, Busch MP, Cohen MS. How can we better identify early HIV infections?. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2015; 10:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ananworanich J, Fletcher JLK, Pinyakorn S, van Griensven F, Vandergeeten C, Schuetz A, et al. A novel acute HIV infection staging system based on 4th generation immunoassay. Retrovirology 2013; 10:56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sands A, Vercauteren G, Fransen K, Beelaert G. Poor antigen sensitivity of three innovative rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) for detection of HIV-1 p24 antigen and HIV-1/2 antibodies. In 19th International AIDS Conference; 2012. Abstract No. LBPE14. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.