Abstract

Social scientific investigation into the religiospiritual characteristics of American Indians rarely includes analysis of quantitative data. After reviewing information from ethnographic and autobiographical sources, we present analyses of data from a large, population-based sample of two tribes (n = 3,084). We examine salience of belief in three traditions: aboriginal, Christian, and Native American Church. We then investigate patterns in sociodemographic subgroups, determining the significant correlates of salience with other variables controlled. Finally, we examine frequency with which respondents assign high salience to only one tradition (exclusivity) or multiple traditions (nonexclusivity), again investigating subgroup variations. This first detailed, statistical portrait of American Indian religious and spiritual lives links work on tribal ethnic identity to theoretical work on America’s “religious marketplace.” Results may also inform social/behavioral interventions that incorporate religiospiritual elements.

On the most recent decennial census, more than 4.1 million people identified themselves as American Indian or Alaska Native, either exclusively or in combination with other ancestries (Grieco and Cassidy 2001). The interest of sociology’s founders in the world’s indigenous religions notwithstanding (e.g., Durkheim 1915), early studies of American Indians’ religiospiritual characteristics were carried out overwhelmingly by anthropologists.1 Such work has allowed for critical advances in scholarship. Of special note is Boas’s turn-of-the-20th-century work among Arctic and Northwest Coast peoples (Boas and Stocking 1974), which challenged his discipline’s assumption that tribal societies were the evolutionary inferiors to “civilized,” industrial, Christian ones. Also notable are the subsequent writings of Deloria (1973), which opened the way for research on American Indian religions across a range of disciplines within the field of American Indian Studies. While still focused mainly on qualitative data and methods, contributions from within this new, interdisciplinary field commonly adopted more emic (or “insider”) perspectives on indigenous spiritual traditions. Importantly, these were increasingly developed by American Indian people working collaboratively with tribal communities (e.g., Baird-Olson and Ward 2000; O’Brien 2008; Kidwell 1995; Pesantubbee 2005; Talamantez 2000; Wilson 2005).

Nevertheless, even recent work on American Indian religion and spirituality typically focuses on in-depth investigations carried out in small communities or with modestly sized samples. It reflects, as well, relatively little interest in newer forms of belief, continuing to devote greatest effort to examining aboriginal traditions—meaning beliefs and practices with roots among America’s indigenous peoples prior to European contact.

Our distinctively sociological analysis begins by summarizing what is known about religious and spiritual expressions among contemporary American Indian people. We then offer a first detailed, statistical portrait of American Indian religiosity and spiritual engagement, based on large, tribally defined, population-based samples (n = 3,084). Data were collected from legally enrolled citizens of two of the largest, federally recognized tribal groups, which occupy reservations in the Southwest and the Northern Plains. In work with American Indian populations, maintenance of community confidentiality is as important as that of individual confidentiality (Norton and Manson 1996); therefore, by agreement with the participating tribes, general cultural descriptors are used rather than tribal names.

Our analysis focused exclusively on the dimension of religiosity and spiritual engagement2 that is defined by beliefs. We first investigated the importance respondents assigned to beliefs associated with several traditions common to each tribe: aboriginal, Christian, and the syncretic faith known as Native American Church (NAC) or Peyote Way. We then used multinomial logistic regression to examine individual sociodemographic predictors of high belief salience. Finally, we observed the frequency with which people identified beliefs of multiple religious or spiritual traditions as highly salient, again using multinomial logistic regression to investigate sociodemographic predictors. This analysis offers a foundation for examining other critical dimensions of religion and spirituality among American Indians, including relationships to social, behavioral, and health outcomes. It also allows links between work on American Indian ethnic identity and research on America’s “religious marketplace.”

Religion and Spirituality in Native America

Ethnographic and autobiographical accounts of American Indian religion and spirituality suggest a complex mix of at least three sets of beliefs and practices: aboriginal traditions, Christian, and “new” or syncretic faiths that fuse aboriginal and Christian elements (Baird-Olson and Ward 2000; Begay and Maryboy 2000; Csordas 1999; Gill 1982). We offer a description of each.

Aboriginal Spirituality

The cultural diversity among American Indian peoples is considerable. The U.S. government has formal relations with over 300 tribes in the 48 coterminous states (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs 2007). Historically, American Indian spirituality took many forms, most of which were culturally specific. Many have argued, however, that identifiable themes emerge across tribes (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992; Garrett and Wilbur 1999; Gill 1982; Hultkrantz 1987). First, spirits are associated with animals, plants, and other aspects of the natural world. The Great Spirit, found in some traditions, may be less a personal God as in the Judeo-Christian-Islamic traditions, and more an omnipresent spirit, or collectivity of spirits, inhabiting the universe (Garrett and Wilbur 1999; Hartz 1997; but see also Hultkrantz 1987:26–27, for a discussion of the complexity of this idea).

Also conceptualized as “unseen powers” (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992:9), such spirits are commonly understood as strongly interdependent with each other and with humans; moral humans are those who maintain balanced and harmonious relationships with all beings. American Indian aboriginal spiritualities often include rituals to accompany transitions between life stages such as birth, puberty, childbearing, and death. Above all, these spiritualities are geographically based: “generally rooted in a particular landscape, focused on this particular river, on that mountain” (Jenkins 2004:45; see further Martin 2001:ix–x; Deloria and Wildcat 2001). Sacred sites may be the location of collective ceremonies, as well as special places for individuals pursuing vision quests, pilgrimages, healing, and prayer. Such practices bring persons closer to aboriginal views of the world—and allow traditions to grow (Brown 2001; Cajete 1994).

Typically, meanings invoked in aboriginal rituals and oral traditions are multidimensional, drawing on culturally specific stories of a people’s origins and obligations to the spirit world. The same is true of everyday life because American Indian peoples generally do not relegate spiritual practice to a separate institutional sphere but foster its pervasiveness in all activities (de Angulo 1926). Appropriate behavior, while delineated differently across cultures, tends to be well specified and includes showing integrity in one’s affairs, respecting all beings (human and other-than-human), and attempting to maintain harmonious relationships (St. Pierre and Long Soldier 1995). Individual attentiveness to sacred traditions and practices is often seen as integral to collective well-being; great respect is accorded to those who follow often difficult, culturally defined religious “roads,” a common metaphor in many American Indian communities (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992).

The practice of aboriginal spiritualities has been actively discouraged or prohibited for most of the postcontact period—that is, after the arrival of Europeans in 1492. As part of assimilation policies, colonial agents (including the American government) interfered with and often outlawed aboriginal spiritual practices (Jennings 1975:3–14). Ceremonials such as feasts, dances, and giveaways were forbidden under the “Indian Religious Crimes Code,” developed in the late 19th century by the Secretary of the Interior and later codified as the “Rules for Indian Courts” (Irwin 1997). Penalties for religious observance included withholding food rations or imprisonment up to 30 days; practicing ceremonial leaders could be imprisoned up to six months (Morgan [1892] 1990; see further Prucha 1986). The harshness of federal policies toward aboriginal religions changed little until the 1930s, when appointment of John Collier as Commissioner of Indian Affairs led to the first policy statement (Bureau of Indian Affairs Circular #2970) aimed at protecting American Indian rights to spiritual practice (Irwin 1997). Still, it was only in 1978 that the American Indian Religious Freedom Act (AIRFA) was passed “to protect and preserve for American Indians their inherent right of freedom to believe, express, and exercise” their aboriginal spiritualities (Public Law 95–341).3 Some contemporary religions (notably strains of fundamentalist Christianity) continue to discourage American Indian people from participating in any type of aboriginal ceremonies (Baird-Olson and Ward 2000).4

Even during periods of active suppression, aboriginal beliefs and practices were observed privately. Moreover, the past several decades have been characterized by a resurgence of aboriginal traditions. Sociologists Baird-Olson and Ward (2000) draw on data from focus groups and in-depth interviews to describe the ways that three generations of contemporary women on two Northern Plains reservations used spiritual resources to survive victimization and resist colonization; their research reveals a number of “new traditionalists,” women who have reclaimed aboriginal spiritualities. Sociologist Nagel (1996:6) sees such spiritual renewal as part of a broader rebirth of American Indian ethnic identity, observing that “there has been a steady and growing effort on the part of many, perhaps most, Native American communities [since the 1960s] to preserve, protect, recover, and revitalize cultural traditions, religious and ceremonial practices, sacred or traditional roles, kinship structures, languages, and the normative bases of community cohesion” (cf. Cornell 1988; Cornell and Hartmann 1998).

That revitalization of aboriginal spiritualities has occurred several decades after the disappearance of tribal cultures was regularly predicted makes such developments especially remarkable. Yet no systematic data have documented prevalence and salience of specific beliefs and practices or investigated differences by demographic subgroups within any American Indian population.

Christianity

From first contact, conversion of American Indians has been a high priority among many Christian denominations, but the degree to which people accepted this faith varied tremendously (Bowden 1981; Martin 2001). Initially, Roman Catholicism was the predominant Christian faith, due to the influence of Spanish and French missionaries. As the United States gained control of tribal lands, Protestant faiths launched missionary movements, with the government often actively supporting such efforts and even assigning individual Indian agencies exclusively to specific denominations (Bowden 1981). These included mainline Protestant religions such as Episcopalian, Lutheran, and Methodist; starting in the late 1800s, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints became active in many American Indian communities in the intermountain west (Larson 1963). More recently, conservative sects such as Pentecostals and Jehovah’s Witnesses have gained adherents. In many communities, especially in the Southwest, tribal members have come together in fundamentalist congregations only loosely related to those elsewhere (e.g., Steinmetz 1998).

Reasons for tribal antipathy toward Christianity abound. Fifteenth-century papal bulls urged European rulers “to invade, search out, capture, vanquish, and subdue all … pagans … and to reduce their persons to perpetual slavery, and to … appropriate [their] … kingdoms … and goods” (Romanus Pontifex; full text in Davenport 1917:20–26). Similar ideas, subsequently developed into the Doctrine of Discovery, were codified into American law that assigned land title in the New World to its colonizers (Deloria and Lytle 1983:2–6). The entanglement of religious and political interests in the Americas (as elsewhere) too often made missionary activity an element in tribal expropriation (Baird-Olson 2005; Miller 2006; Newcomb 2008). This helps explain why some contemporary American Indian people reject Christianity (Martin 2001:77–78).

At the same time, other American Indians find Christian beliefs fully compatible with aboriginal ones and express commitments to both (Csordas 1999; Martin 2001:75–78, 82; Treat 1996). One author even described this “bireligious” impulse as the “normative stance,” at least among one of the larger Plains tribes (Vecsey 1999:63; cf. Heidenreich 2005). Visitors to today’s reservations will be struck by the presence of churches, as well as by wide variation in denominations across reservations. Yet little hard data have been available to support generalizations about American Indian Christianity—either its prevalence, its association with specific demographics, or the extent to which followers entertain simultaneous commitments to other traditions.

The Native American Church

American Indian religions were never static. Evidence abounds for accommodation of multiple traditions before European contact. In fact, fusion of belief systems has been observed by anthropologists as a hallmark of American Indian traditions and is especially notable in “new” religions postcontact. A prominent example of syncretic religions is the NAC, or Peyote Way. Its practices, which have roots in pre-Columbian traditions, were probably introduced to Oklahoma tribes by the Lipan Apache in the 1880s (Stewart 1987). Since that time, the NAC has spread to many tribes. Its central ceremony occurs at night and is conducted by a “roadman,” a leader who often travels between communities. Participants sing, pray, and consume peyote buttons, peyote tea, or dried ground peyote under carefully controlled ceremonial conditions; peyote is treated as a sacrament that assists practitioners in achieving closeness with the sacred. There are numerous subtraditions within the NAC, with some identifying more strongly with expressly Christian ideas, interpretations, and symbols. However, it is not uncommon for peyote to be compared to the Eucharist in Christian ceremonies, some followers believing that Jesus may be found in or through the spirit of peyote (Gill 1982; Spider 1996).

The NAC is not a structured religion in the sense of having codified creeds and rituals (Stewart 1987), but followers are encouraged to live the “right way,” and to seek balance in their physical, emotional, and spiritual lives. Typically, all use of alcohol and drugs is prohibited (Smith and Snake 1996). Adherents to the NAC have faced misperceptions and hostility from both formal and informal sources. Government agents, missionaries, law officers, and others worked to prohibit peyote in the early 20th century. Followers countered by formally incorporating as a church, but the move brought only partial protection. In 1994, Congress amended AIRFA (via the Native American Free Exercise of Religion Act) to provide for American Indians’ use of peyote in all states—or at least by those American Indian people who have formally established tribal citizenship.5

Little reliable information documents how many people follow the Peyote Way. A survey sponsored by the Indian Health Service and conducted on one Northern Plains reservation in the 1960s (n = 1,500) found less than one percent of residents reporting their religion as NAC (U.S. Indian Health Service 1969), although legal sanctions that worshippers then confronted undoubtedly affected responses. More recent sources offer national membership estimates in the hundreds of thousands (Smith and Snake 1996:172; Stewart 1987:327). Overall, however, the literature agrees that previous membership estimates are based on limited data and incomplete records, and information about participants’ demographic characteristics is entirely lacking.

Having summarized three religious traditions among American Indian peoples, we now turn to our own data and analysis. We will investigate patterns of belief in two large, reservation-based tribes, with attention to the prevalence and salience of particular beliefs and to frequency of overlap among multiple beliefs. We will ask whether particular demographic characteristics are associated with particular beliefs, or with belief in multiple traditions.

Method

Study Design and Sample

The primary objective of the American Indian Service Utilization and Psychiatric Epidemiology Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP) was to estimate the prevalence of psychiatric disorders and health service utilization in two reservation populations; this survey also collected demographic data about psychosocial constructs, including religiosity and spiritual engagement. Participating tribes were chosen for their size and specific characteristics. These Southwest and Northern Plains groups belong to different linguistic families, have different migration histories, embrace different principles for reckoning kinship and residence, and have historically pursued different forms of subsistence. Nevertheless, both have many experiences in common with other American Indian groups. They share similar histories of colonization—including dramatic military resistance, externally imposed forms of governance, and active missionary movements. Although based on quite different epistemologies, aboriginal beliefs systems are active in both tribes, with those in the Southwest particularly well articulated and preserved.

AI-SUPERPFP methods are described elsewhere (Beals et al. 2003); our website provides additional information, including interview and training manuals (http://aianp.uchsc.edu/ncaianmhr/research/superpfp.htm). Populations of inference were citizens of the Northern Plains or the Southwest tribe who were enrolled under tribal law. All were 15–54 years old when the sample frame was developed (1997) and lived on or within 20 miles of their reservations. Using stratified random sampling procedures (Cochran 1977) with tribal rolls, each population was stratified by age and gender. Data were collected between 1997 and 1999; thus, some sample members had reached 57 years at the time of interview, and fewer sample members were 15. A replicate strategy was used in which random groupings of names were released in sequence for location until the target sample size (about 1,500 per tribe) was reached.6 Overall 39.5 percent and 46.5 percent of the Southwest and Northern Plains tribal members were found to be living on or near their reservations. Once located and found eligible, 73.7 percent agreed to participate from the Southwest (n = 1,446) and 76 percent from the Northern Plains (n = 1,638).

Instrumentation

The AI-SUPERPFP interview consisted of a series of modules; those of interest to the current analysis asked about demographics and religiospiritual beliefs. Tribal members conducted all interviews after intensive training in research and interviewing procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; for minors, parental/guardian consent was acquired before adolescent assent. Tribal approvals were obtained prior to project implementation.7 Questions were administered using a computer-assisted personal interview. Extensive quality control procedures verified that all portions of location, recruitment, and interview procedures were conducted in a standardized, reliable manner.

Measurement of Beliefs

Our project asked about salience of beliefs associated with specific religiospiritual traditions. During the instrument development phase, researchers sought assistance from focus groups conducted with each tribe. These groups reviewed measures commonly found in the literature on religiosity, such as the Midlife Development Inventory or MIDI (MacArthur Foundation 2006), and offered advice allowing us to adapt them for American Indian populations. A central focus group suggestion was that we separate questions about three traditions—aboriginal, Christian, and NAC. Thus, our survey questions named each tradition individually and asked: “How important are these beliefs to you?”8 Possible responses included “very important,” “somewhat important,” and “not at all important.” Notably, these measures did not force the choice of a single religiospiritual “preference” or “affiliation.” Instead, they served our interest in assessing prevalence of specific beliefs and their salience, along with overlap in beliefs from different traditions.

Statistical Methods

Variable construction was completed using SPSS (SPSS Inc. 2002). All inferential analyses were in conducted in Stata (Stata 2002) using sample and nonresponse weights (Cochran 1977). Bivariate analyses used a Pearson’s chi-square, corrected for the survey design and converted to an F statistic, and determined the significance levels of comparisons of proportions. Due to the substantial number of possible pair wise comparisons, 99 percent rather than 95 percent confidence intervals were calculated. In multivariate analyses, multinomial logistic regression methods (Long and Freese 2003) allowed for simultaneous investigation of the relationships of demographic variables to high belief salience, as well as to belief in multiple traditions.

Results

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample can be found in Table 1. Given their cultural and historical differences, the two tribes were best considered as separate populations and described independently; the table thus presents data for each tribe individually. Moreover, a significantly greater percentage of the Southwest sample was female than in the Northern Plains. (Review of location records indicated that the gender difference was largely due to the migration of Southwest men to off-reservation communities for employment.) The differing gender distributions encouraged us to stratify our analysis by gender as well as tribe. Results revealed demographic differences that followed expected patterns. For instance, Table 1 shows that significantly more Southwest women than Northern Plain women were 35 years of age or older, women in both tribes were more likely than their male counterparts to have education beyond high school, and Southwest women were more likely than Northern Plains men to be married.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample: Percentages and 99 percent confidence intervals

| Southwest (SW)

|

Northern Plains (NP)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Men (n = 617) | b. Women (n = 829) | c. Men (n = 790) | d. Women (n = 848) | |

| Gendera | 56.5 | 50.5 | ||

| Age <35 | 51.9 (49.5–54.2) | 50.2 (48.2–52.2) | 51.7 (49.5–53.9) | 55.3 (51.3–53.3) |

| Age 35+a | 48.1 (45.8–50.5) | 49.8 (47.8–51.8)e | 48.3 (46.1–50.5) | 44.8 (42.6–46.9)c |

| ≤ high school | 77.4 (72.7–81.5) | 66.9 (62.4–71.1)d | 78.9 (74.7–82.6)ce | 69.7 (65.2–73.8)d |

| >high schoola | 22.6 (18.5–27.3)c | 33.1 (28.9–37.6)bd | 21.1 (17.4–25.3)ce | 30.3 (26.2–34.8)d |

| Not married | 42.5 (37.6–47.6) | 37.8 (33.6–42.2)d | 51.0 (46.2–55.8)c | 46.3 (41.8–50.9) |

| Marrieda | 57.5 (52.4–62.4) | 62.2 (57.8–66.4)d | 49.0 (44.2–53.8)c | 53.7 (49.1–58.2) |

p ≤ .01.

Significantly different from SW men.

Significantly different from SW women.

Significantly different from NP men.

Significantly different from NP women.

Prevalence and Salience of Religious and Spiritual Belief

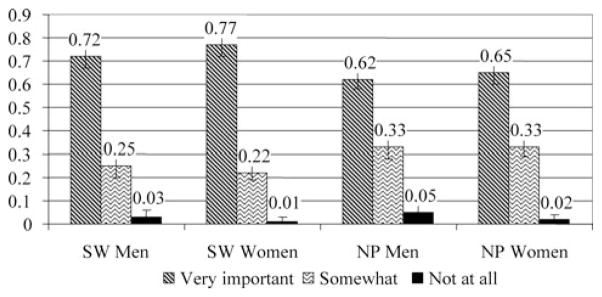

Table 2 shows the level of salience that participants attributed to any religious or spiritual belief. It shows the percentage of respondents in tribe-by-gender subgroups that endorsed at least one tradition’s beliefs as “very important” or “somewhat important,” as well as the percentage that characterized all beliefs as “not at all important.” Here one learns, for example, that the majority of Southwest men (72 percent) rate the beliefs of at least one religious or spiritual tradition at the highest level of salience. In addition, overall prevalence of belief—meaning respondents’ endorsement of any beliefs at any level—may be calculated from this table by summing responses for “somewhat” and “very” important. The prevalence of belief among Southwest men is thus 97 percent (72 percent + 25 percent). Prevalence of belief across all tribe and gender groupings ranged from 95 percent to 99 percent.

Table 2.

Prevalence+ and salience of any beliefs in tribe-by-gender subgroups: Percentages and 99 percent confidence intervals

| Level of Saliencea | Southwest (SW)

|

Northern Plains (NP)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Not at all | .03 (.02–.06) | .01 (.00–.03) | .05 (.03–.08) | .02 (.01–.04) |

| Somewhat | .25 (.20–.30) | .22 (.19–.27)cd | .33 (.28–.37)b | .33 (.29–.38)b |

| Very | .72 (.67–.77) | .77 (.72–.80)cd | .62 (.58–.67)b | .65 (.60–.69)b |

Prevalence of religious belief is calculated by summing “somewhat” and “very” responses.

p ≤ .001.

Significantly different from SW women.

Significantly different from NP men.

Significantly different from NP women.

There was no significant subgroup difference in percentage of respondents who chose “not at all important.” Differences between tribes were similarly absent for other levels of salience. However, Southwestern women were significantly less likely to describe beliefs as only “somewhat important,” and significantly more likely to describe beliefs as “very important,” as compared to both men and women in the Northern Plains. Figure 1 graphically summarizes information from Table 2. It underscores the uniformly high prevalence of belief across tribe and gender groups, along with typically high salience.

Figure 1.

Importance of combined beliefs.

Table 3 presents estimates for the salience of the three particular beliefs: aboriginal, Christian, and NAC. It shows that the great majority of respondents (86–91 percent) indicated that aboriginal beliefs were at least “somewhat important,” with about half describing these as “very important.” Although overall probability of a significant difference was .027, examination of the 99 percent confidence intervals yielded no differences in importance of aboriginal beliefs across tribe-by-gender groupings.

Table 3.

Salience of particular religious beliefs in tribe and gender groups: Percentages and 99 percent confidence intervals (N = 3,084)

| Belief | Level of Saliencea | Southwest (SW)

|

Northern Plains (NP)

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Aboriginal | Not at all | .11 (.08–.15) | .14 (.11–.17) | .09 (.07–.13) | .10 (.08–.13) |

| Somewhat | .35 (.30–.41) | .32 (.28–.37) | .38 (.33–.43) | .40 (.35–.45) | |

| Very | .53 (.48–.59) | .54 (.49–.59) | .53 (.48–.58) | .50 (.45–.55) | |

| Christian | Not at all | .25 (.20–.30) | .18 (.15–.22) | .24 (.20–.29) | .22 (.20–.24) |

| Somewhat | .44 (.39–.50) | .43 (.39–.48) | .53 (.48–.58) | .49 (.44–.54) | |

| Very | .31 (.26–.36) | .39 (.34–.43)de | .23 (.19–.28)c | .29 (.25–.33)c | |

| NAC | Not at all | .31 (.26–.37) | .33 (.29–.38) | .33 (.29–.38) | .36 (.32–.41) |

| Somewhat | .37 (.31–.42) | .32 (.28–.37) | .42 (.37–.47) | .42 (.37–.47) | |

| Very | .32 (.27–.38)e | .35 (.30–.40)de | .25 (.21–.29)c | .22 (.18–.26)bc | |

Statistical significance for level of salience given aboriginal beliefs, p ≤ .027; for Christian and NAC belief, statistical significance, p < = .001.

Significantly different from SW men.

Significantly different from SW women.

Significantly different from NP men.

Significantly different from NP women.

Note: Prevalence of particular beliefs is calculated by summing “somewhat” and “very.”

Christian beliefs were endorsed at some level by 75–82 percent of respondents across groups, with between 23–39 percent of the participants describing these as “very important.” Christianity was significantly more likely to be identified as “very important” among Southwestern women, as compared to both men and women in the Northern Plains.

A smaller majority of respondents (64–69 percent) rated NAC beliefs salient in at least some degree, with 20–35 percent describing them as “very important.” NAC was significantly more likely to be viewed as “very important” in the Southwest compared to the Northern Plains, especially among women.

Overall, each of the three traditions found substantial numbers of believers. Aboriginal beliefs were most likely to be reported as highly salient.

After examining prevalence and salience of belief in general, as well as of specific beliefs, we calculated a series of multinomial logistic models. For aboriginal, Christian, and NAC traditions, we regressed level of salience on demographic variables including gender, tribe, education, age, and marital status. The regression models compared the odds that respondents in specific demographic subgroups would attribute particular levels of salience to each tradition, with other variables controlled.

As shown in Table 4, specific demographic factors were significantly associated with salience of aboriginal beliefs. Respondents from the Northern Plains were more likely than their Southwestern counterparts to report aboriginal beliefs as “somewhat important” compared to either “not at all” or “very important,” while respondents in both tribes with education beyond high school had significantly higher odds of identifying aboriginal beliefs as “very important.”

Table 4.

Odds ratios from multinomial logistic regression examining predictors of belief salience (N = 3,084)

| Belief | Referent Category | Comparisons for Level of Salience

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Not at All Important | Somewhat Important | |||

|

| ||||

| Somewhat Important | Very Important | Very Important | ||

| Aboriginal | men | 1.18 | 1.22 | 1.03 |

| Northern Plains | 1.50** | 1.24 | .82* | |

| >high school | 1.14 | 1.45** | 1.28** | |

| age 35+ | .77 | .94 | 1.21* | |

| married or cohabiting | 1.27 | 1.21 | .96 | |

| Christian | men | .86 | .65** | .75** |

| Northern Plains | 1.08 | .68** | .63** | |

| >high school | .96 | 1.05 | 1.09 | |

| age 35+ | 2.07** | 3.33** | 1.61** | |

| married or cohabiting | 1.20 | 1.14 | .95 | |

| NAC | men | 1.14 | 1.07 | .94 |

| Northern Plains | 1.14 | .65** | .57** | |

| >high school | .96 | 1.09 | 1.14 | |

| age 35+ | .68** | .96 | 1.41** | |

| married or cohabiting | 1.12 | 1.06 | .95 | |

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Salience of Christian beliefs was also related to demographic variables, specifically gender and tribe: men and Northern Plains residents were less likely than women and Southwest residents to describe Christianity as “very important.” Age was also significant, with those aged 35 and older demonstrating a progression in which “not at all important” was least likely and “very important” was most likely.

Demographic patterns for the NAC also take in tribe and age, but differently. As with Christianity, Northern Plains respondents had lower odds of rating NAC beliefs as “very important” than of identifying lower salience. At the same time, older respondents tended not to embrace NAC beliefs at a moderate level; they had significantly higher odds of either endorsing these beliefs at the highest level of salience or of rejecting them altogether as compared to describing them as only “somewhat important.”

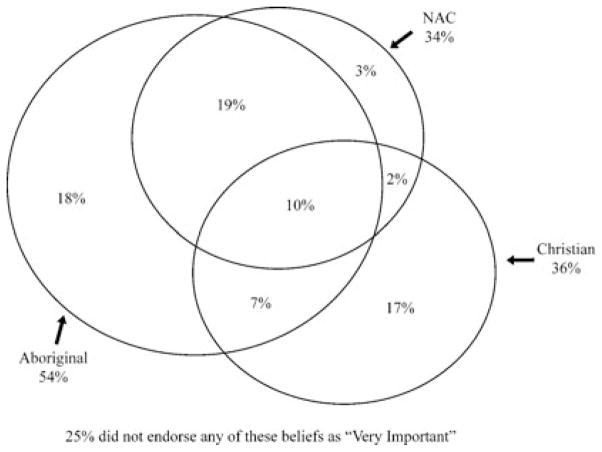

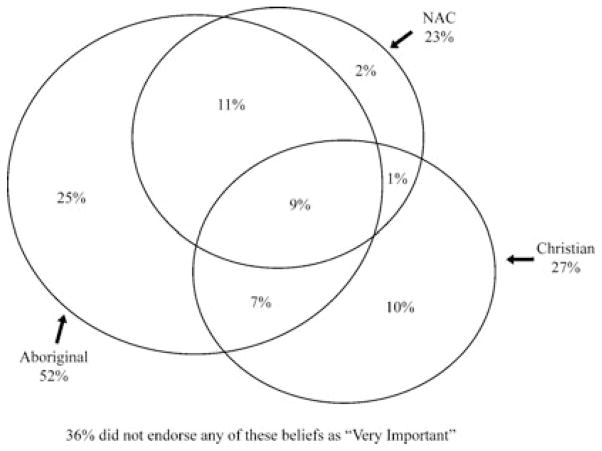

Overlap Among Beliefs

In examining overlap in beliefs, we sought patterns of exclusivity, meaning embrace of only one tradition’s beliefs as “very important,” and nonexclusivity, meaning assignment of high salience to more than one set of beliefs. Figures 2 and 3 show the percentage of respondents in both categories—first in the Southwest, then in the Northern Plains. Although percentages for highly salient belief vary by tribe, the pattern of overlap across specific traditions is similar. Most noteworthy is that a majority of believers in every tradition in both tribes indicated at least one other tradition as “very important.” Predictably, this was most pronounced among adherents of the heavily syncretic NAC. However, even among respondents ascribing to aboriginal or Christian beliefs, most reported at least one other tradition’s beliefs as “very important.” In the Southwest, identification of multiple beliefs was least common among Christians, of whom 47 percent (17 percent/36 percent) said that only Christian beliefs were “very important.” In the Northern Plains, aboriginal believers were the most distinctive, with 48 percent (25 percent/54 percent) reporting no other beliefs as “very important.”

Figure 2.

Religious exclusivity and syncretism in the Southwest: the overlap of “very important” beliefs.

Figure 3.

Religious exclusivity and syncretism in the Northern Plains: the overlap of “very important” beliefs.

Table 5 builds upon the foregoing figures, using multinomial logistic regression. For these models, we first examined demographic characteristics of respondents who reported exclusively aboriginal or exclusively Christian beliefs as “very important.” We then grouped all NAC believers together with all those who embraced more than one set of beliefs as “very important” into a single “Non-Exclusive” category and considered their characteristics. This analytic strategy simplified comparisons and seemed justifiable because the NAC is customarily described as a syncretic faith, suggesting that it is nonexclusive virtually by definition; it also reflected our own, empirical finding that the great majority of NAC believers assigned high salience to more than one set of beliefs.

Table 5.

Multinomial logistic regression: Outcome is 4-level belief choice category created by endorsing “very important”a

| Referent | No Beliefs

|

Aboriginal Only

|

Christian Only

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aboriginal Only | Christian Only | Non-Exclusiveb | Christian Only | Non-Exclusiveb | Non-Exclusiveb | |

| Men | 1.02 | .60** | .85 | .59** | .83 | 1.42** |

| Northern Plains | .94 | .39** | .51** | .42** | .55** | 1.30* |

| >high school | 1.29* | 1.26 | 1.36** | .97 | 1.06 | 1.09 |

| Age 35+ | 1.22 | 2.52** | 1.66** | 2.06** | 1.36** | .66** |

| Married or cohabiting | 1.02 | .98 | 1.07 | .95 | 1.04 | 1.10 |

p ≤ .05;

p ≤ .01.

Coefficients smaller than 1 indicate reduced odds of endorsing a category as compared to the category in the row labeled “Referent.” Numbers greater than 1 indicate greater odds of endorsing a category as compared to the referent. For example, respondents with education beyond high school had significantly higher odds of reporting only aboriginal beliefs as “very important” than of reporting no religious beliefs as “very important” (OR = 1.29). Male believers had significantly lower odds of saying that only Christian beliefs were “very important” to them, as compared to placing only aboriginal beliefs in this category (OR = .59). Men were also more likely to report “Non-Exclusive” (multiple) beliefs as “very important” than to describe only Christian beliefs in this way (OR = 1.42).

As described in the text, the “Non-Exclusive” category comprises all respondents endorsing beliefs of any two or more religions as “very important.” Because virtually all NAC respondents displayed this pattern, they were also grouped into the “Non-Exclusive” category.

Table 5 allowed comparisons of the odds that respondents in particular demographic subgroups would embrace only aboriginal beliefs (“Aboriginal Only”), only Christian beliefs (“Christian Only”), multiple beliefs (“Non-Exclusive”), or “No Beliefs” as “very important.” For the first three columns in Table 5, the referent is the category of respondents who said that no beliefs were “very important.” (This referent combines respondents who endorsed beliefs as either “not at all” or only “somewhat important,” meaning that results in Table 5 are not directly comparable to those in Tables 2–4.)

As shown, both men and members of the Northern Plains tribe were significantly less likely to embrace “Christian Only” beliefs than to have described none of the three beliefs as very important (“No Beliefs”). Age and education were also significant in these comparisons. For example, respondents over age 35 were significantly more likely to identify only Christian beliefs as “very important” than they were to describe “no beliefs” in this way, while those with more than high school education were more likely to attribute high salience only to aboriginal beliefs as compared to no beliefs. Older respondents and respondents with more formal education were also more likely to report the multiple beliefs defining the “Non-Exclusive” category compared to describing no beliefs as “very important.”

Columns 4–6 in Table 5 show paired comparisons between believer subgroups—that is, between respondents classified into the “Aboriginal Only,” “Christian Only,” and “Non-Exclusive” categories. In Columns 4 and 5, the referent is “Aboriginal Only” and in Column 6 it is “Christian Only.” Resulting patterns often resemble those derived from the foregoing comparisons with the “No Beliefs” category. For example, men and Northern Plains residents were relatively unlikely to describe “Christian Only” beliefs as very important, compared to either “Aboriginal Only” or “Non-Exclusive” beliefs. Older respondents were the most likely to respond “Christian Only” as compared to any other beliefs.

Discussion

This is the first population-based, systematic report of the importance of three religiospiritual traditions that qualitative research (and our focus groups) have described as common among American Indians. The first notable finding concerns religiosity and spiritual engagement as measured by prevalence of belief in general: almost all our respondents (95–99 percent in specific tribe and gender groups) said that the beliefs from one or more traditions were at least “somewhat important”; only tiny percentages (1–5 percent) described all beliefs as “not at all important.” These figures provide evidence for very high prevalence of belief in the tribal populations sampled. Although differences in question wording dictate only cautious comparison, data from the recent American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) indicating that about 14 percent of Americans in the general population report themselves as having no religion provides context for our finding (Kosmin, Mayer, and Keysar 2001a). A 2007 Gallup poll of about 1,000 Americans reported the similar finding that 17 percent indicated that religion was “not very important” in their lives (Polling Report.com 2007).

Results from our questions about salience of belief in particular religiospiritual traditions in our sample similarly compel attention. Given the overt oppression of aboriginal spiritualities from European contact into recent times, it is especially noteworthy that at least half the respondents in both tribes described aboriginal beliefs as “very important.” These findings correspond rather closely with rare data collected in the early 1990s from a subpopulation of one Southwestern tribe (residents in delimited areas of the Navajo reservation) as part of an epidemiological study. While methodological differences do not allow direct comparisons, this earlier finding adds to confidence in our strikingly high estimates for strongly salient aboriginal beliefs in the Southwest (Kunitz, Levy, and Andrews 1994:113). Moreover, anecdotal reports indicate that the oldest tribal members ascribe to aboriginal beliefs at higher rates, suggesting that our sample (which included no one over 57 years) may even underrepresent aboriginal belief.

Our findings stand in dramatic contrast not only to popular stereotypes about “vanishing” American Indian cultures, but also to the only large-scale research that offers any comparable figures on American Indian religiosity, the ARIS. This survey asked a nationally representative sample of 50,000 Americans: “What is your religion, if any?” Of American Indian respondents (1–2 percent of the full sample), it reported that only 3 percent affiliated with “Indian” or tribal religion (Kosmin, Mayer, and Keysar 2001b).

The enormous difference in findings may result, in part, from different instrumentation between our survey and the ARIS. Yet of even greater probable importance are definitions of “American Indian” that captured disparate populations: while the nationwide ARIS defined Indians by self-identification, our project exclusively sampled reservation-based tribal citizens. Given the role of reservations as repositories of cultural knowledge and practice, one would expect our survey to identify more people assigning importance to aboriginal religion than do broader samples. Finally, as a telephone interview using a sampling scheme based on the largely urban/suburban distribution of the U.S. population, the ARIS might be expected to be highly biased for American Indians, who are more likely to reside in rural areas and frequently lack telephone service (Ericksen 1996; Snipp 1996). The important lesson is that, even in the rare case where religiosity data from national surveys are available for American Indians, they may seriously underrepresent prevalence of aboriginal religion in particular tribal populations, perhaps especially in reservation populations.

The aboriginal beliefs endorsed by about half our sample are not the only focus of religiospiritual expression. With about one-third of respondents assigning high salience to Christian and another one-third to NAC beliefs, these faiths clearly constitute substantial minorities. (Percentages do not sum to 100 because many respondents endorsed more than one set of beliefs.) Instructive variations emerged, however, in patterns of belief among respondents by demographic subgroups. That Northern Plains respondents were significantly less likely than Southwest to consider Christian or NAC beliefs very important is consistent with general patterns that researchers in anthropology and religious studies have described (Bowden 1981; Stewart 1987).

The probable primary explanation for intertribal variations in prevalence of particular religiospiritual beliefs revolves around cultural differences: compared to the Southwest tribe, Northern Plains aboriginal spiritualities are highly personal and individually variable, often linked to individual vision experiences (Gill 1982:163; Irwin 1994). With such a cultural history, it is reasonable that Northern Plains tribal members would be less likely to report that the more formal traditions—those incorporated as churches—were important. As for Christian churches in particular, these experienced a surge in membership in the Southwest in the second half of the 20th century; this increase is commonly attributed to the growth of more fundamentalist and Pentecostal denominations that pursued distinctive evangelistic strategies, especially the installation of American Indian clergy (Levy 1998; Kunitz, Levy, and Andrews 1994). The continuing success of Christian evangelism in the Southwest relative to the Northern Plains may reflect this denominational history.

Within each tribe, the relative frequency of assigning importance to specific traditions by gender is of special interest. Research in the sociology of religion has consistently found that women score higher on measures of personal piety than men (Gallup 2002). This pattern persists even across nations and cultures (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Sullins 2006) and is so pervasive that some sociologists have recently gone so far as to entertain its biological basis (Stark 2002; Miller and Stark 2002). Nevertheless, the typical “female advantage in religiousness” (Sullins 2006:838) is reproduced within neither of the tribes we examined.

At the same time, gender is not irrelevant in all comparisons; Southwest women are significantly more likely than any of their Northern Plains counterparts—male or female—to claim Christian beliefs. The meaning of this difference is unclear but provokes questions about whether the female-dominant pattern will hold true within tribal populations. Further examination of such cases wherein gender does not behave as expected might shed light on factors that researchers have advanced to explain female dominance in religiosity and spirituality; these include women’s socialization, their structural position in the division of labor, their personality traits, and their disinclination toward risk taking (review in Sullins 2006).

Equally interesting are relationships with education. Associations between formal educational achievement and measures of religiosity are debatable even for the general population. A significant body of research associates higher education with lower religiosity, as measured by both beliefs and practices (Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Princeton Religion Research Center 2002; cf. Newport 2006; Winseman 2005). Yet other research, including a study of over 7,400 Mormons in the United States and Canada, has linked educational attainment positively to indicators of religiosity, including belief salience (Albrecht and Heaton 1984; cf. Merrill, Lyon, and Jensen 2003; Thompson, Carroll, and Hoge 1993). Other work argues for no significant association (Caplow, Bahr, and Chadwick 1983; Wortham 2006). Our analysis similarly found no relationships between belief salience and education for Christianity and NAC; however, strongly salient aboriginal beliefs were significantly more prevalent among tribal members with education beyond high school. These findings are consistent with the possibility that the relationship between religiosity and education should not be overgeneralized but “needs to be qualified by specific references to particular denominations and faith traditions” (Merrill, Lyon, and Jensen 2003:114).

The distinctive, significant variations in salience by education for different religiospiritual traditions invite theoretical interpretation, for which the sociological perspective of the “religious marketplace” offers a starting point. Sociology of religion was long dominated by a paradigm, associated with researchers from Durkheim (1915) to Berger (1969), in which religious homogeneity—the authoritatively imposed “monopoly” of a single tradition—stimulates religiosity. Exponents argued that religious monopoly reduces likelihood that believers will experience the collapse of taken-for-granted realities that can accompany the confrontation of ideas and practices with alternatives available in more pluralistic contexts (review in Warner 1993; cf. Wortham 2006).

By contrast, advocates of a newer paradigm have proposed an opposite dynamic: “the more pluralism, the greater the religious mobilization of the population” (Finke and Stark 1988:43; cf. Stark and Finke 2000, 2002). In this view, demonopolized settings may actually foster religious florescence because they “provide niches that satisfy the consumer demand for religious products” while simultaneously holding down participation costs (Wortham 2006:456). Indeed, empirical studies have associated religious pluralism with higher rates of participation and greater belief (Iannaccone 1991; Wortham 2006).

The “marketplace” perspective urges sociologists to devote less effort to thinking about how religious people create “plausibility structures” to shore up beliefs. Instead, it urges us to attend to what religion does for its adherents (Warner 1993). In our case, this perspective encourages reflection upon possible reasons for the prevalence of highly salient aboriginal beliefs among today’s more formally educated tribal members.

Notably, this finding is consistent with research on the “ethnic renewal” that both sociologists (Nagel 1996) and American Indian people themselves (Deloria 1973) have observed in American Indian communities since the 1960s, as growing numbers of individuals becoming willing—even eager—to assert an American Indian identity (Cornell 1988; Cornell and Hartmann 1998; Garroutte 2003). At the same time, access to some of the most indisputable symbolic markers of this identity, including tribal first-language fluency, has arguably contracted in the same period. This may be especially true for highly educated tribal members. Barriers in the educational system can disadvantage tribal first-language speakers, selecting for those whose primary language is English (Brod and McQuiston 1983); moreover, higher education often takes students away from tribal community or from immediate and undivided attention to its social and cultural activities.

It is possible that the resulting, restricted access to important symbolic markers of American Indian identity might encourage more educated tribal members to embrace aboriginal beliefs as an alternative identifier in the current period of ethnic renewal. This interpretation reflects sociological literature that points to religion as “an accepted mode … of establishing a distinct identity” in ethnic subpopulations (Williams 1988:3) and one that often becomes a vehicle for identity when other symbolic markers, especially language, become unavailable. A similar pattern has long been found in successive generations of immigrant groups (Herberg 1960; Mullins 1988; Millett 1975; Niebuhr [1929] 1957). Nevertheless, more definite interpretation awaits further research.

Another remarkable aspect of our data is the degree of overlap among belief systems. Religious nonexclusivity, or the designation of multiple religious beliefs as “very important,” was common. Among Northern Plains participants who identified at least one religion as very important, more than one-fourth (28 percent) described two or more sets of beliefs in this way, while the number in the Southwest rose to more than one-third (38 percent). At the same time, substantial subgroups—especially of Christians and respondents in the Southwest—reported religious exclusivity, saying that they did not combine beliefs.

These prevalence estimates gain special relevance in the context of prevailing, strong interest in social and behavioral interventions incorporating elements of specifically aboriginal religion. For example, a recent article in the American Journal of Public Health described a program promoting an “integrated healing approach” implemented among the Yavapai of Arizona, which included prayer and participation in religious ceremonies such as sweat lodges (Napoli 2002). Other programs incorporate activities such as vision questing and meditation, increasingly with active participation by American Indian ceremonialists and traditional healers (Abbott 1998; Baird-Olson and Ward 2000; Csordas 2000; Edwards 2003; Mehl-Madrona 1999; Sanchez-Way and Johnson 2000).

Widespread anecdotal reports and growing empirical evidence suggest that such programs have positive outcomes for many (e.g., Abbott 1998), and our findings support the expectation that they will find a sizable audience—perhaps especially among those with more formal education. Yet the sizeable numbers in our sample who endorsed only Christian beliefs as “very important,” especially in the Southwest, suggest that not all American Indian people will find a good fit with intervention programs incorporating elements of aboriginal spirituality. These findings certainly should not discourage such efforts. They do encourage program designers to pay specific attention to the religious characteristics of local American Indian communities and remain open to developing program variations for audiences with a range of religious commitments, including aboriginal, Christian, and NAC.9

Limitations

This study has limitations. It is the first of its kind in American Indian populations, meaning that comparisons to previous work are limited. In addition, our sample represents only a subset of American Indian respondents. Those participating in AI-SUPERPFP lived on or near their home reservations and the location efforts indicated that over half of these tribal populations lived elsewhere; different patterns of results would likely emerge for tribal members not living on or near the reservation.

Similarly, tribes included in this work represented only a small proportion of the cultural diversity of American Indian peoples. We have no reason to believe that the sampled tribes are unique in their religiospiritual patterns; our findings add statistical detail to general patterns suggested in previous anthropological work but do not widely contradict them. Nevertheless, research in other tribal populations will not yield identical results. For instance, we would not expect the NAC to be as influential among all tribal groups (Stewart 1987); Christianity may have greater availability and broader reach in urban areas and in nonreservation populations (such as in Oklahoma) where ongoing contact has facilitated religious adaptation. And while we have argued for the reservations we studied as “cultural repositories” for aboriginal belief, it is unlikely that all reservations function as such to the same extent. Tribes with longer histories of colonization have suffered more severe cultural losses, with repercussions for aboriginal spirituality on the reservation as well as off. Future researchers seeking to understand configurations of belief in other tribal populations should consider factors such as tribal demographics, population size, and geographic location (reservation/nonreservation, urban/rural), duration and nature of cultural contact with other groups, and religious histories, including experiences with missionization or particular spiritual movements.

A further limitation is that this analysis focused exclusively on beliefs; future research should attend to other dimensions of American Indian religiosity and spiritual engagement, particularly practices. Also, our samples do not include respondents younger than 15 or older than 57 years, meaning that we cannot address beliefs in these age groups. Finally, we note statistical limitations. The small numbers in some categories (especially “not at all important”) make it difficult to detect significant differences among tribe and gender groups; odds ratios were of moderate size. Although such limitations are not trivial, they are similar to those characterizing research in studies of belief.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest a portrait of the country’s largest Indian reservations as sites of considerable religiospiritual diversity—settings where a multiplicity of beliefs are highly salient, often in rich combination. Our findings encourage future research that extends our description of American Indian religious and spiritual lives to additional tribal populations. Such efforts promise to broaden theoretical understandings of patterns of belief and their relationship to other variables. They may also inform current interest in social and behavioral interventions that are tailored to the spiritual and cultural needs of American Indian populations.

Footnotes

In 1977, the National Congress of American Indians and National Tribal Chairmens’ Association issued a joint resolution that, in the absence of specific tribal designation, the term “American Indian” was preferred to “Native American” when referring to the indigenous population of the lower 48 states (Beals et al. 2005). The Indian Nations at Risk Task Force (1991) later made the same decision, and we follow this terminological preference.

Religion refers to “system[s] of beliefs, practices, rituals, and symbols designed to facilitate closeness to the sacred … and to foster an understanding of one’s relationship and responsibility to others living in a community” (Koenig, McCullough, and Larson 2001:18). Religiosity then indicates the extent to which individuals express the same. Whereas these terms most clearly apply to experiences that involve regularized ritual and creedal elements, such as Christianity, forms of belief and practice are likely to be labeled as spirituality when they share the “sacred core” of religion but (like many indigenous traditions) involve less organized ritual and collective validation (Larson, Swyers, and McCullough 1997:21). We use the term spiritual engagement to reflect within the domain of spirituality what religiosity reflects within religion.

Other important developments followed. Most notably, these included the Religious Freedom Restoration Act in 1993 and an amendment to AIRFA in 1994. An excellent research report sponsored by the Pluralism Project at Harvard University (McNally 2005) provides a timeline of legislation relevant to American Indian religion since the 19th century, with links to texts. Available at http://www.pluralism.org/research/profiles/display.php?profile=73332.

Tinker’s (1993) Missionary Conquest: The Gospel and Native American Cultural Genocide explicitly characterizes missionary activities as an integral adjunct to the military and political conquest of the Americas; the author describes Christian attitudes toward American Indian spiritualities as an aspect of genocide as contextualized within the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (adopted by Resolution 260 (III) A of the United Nations General Assembly on December 9, 1948). Full text available at http://www.hrweb.org/legal/genocide.html.

Citizenship criteria vary by tribe, but most often require applicants to bureaucratically establish at least one-fourth degree of biological ancestry in a tribe (Thornton 1997).

As we started the AI-SUPERPFP project, researchers knew overall population size as described in tribal enrollment records; however, we did not know how many enrolled persons met sampling criteria by continuing to live on or near the reservation. Thus, rather than releasing all names at once, we did so in randomly chosen groups (N ~ 120) of randomly selected names across the eight age-by-gender strata (15 names per group or “replicate”). This insured that randomness of selection was maintained. Since new replicates were not released until previous ones were closed out, this also ensured that “difficult to locate” tribal members were not left until last, thus reducing another source of bias.

As we began data collection in 1997, the respective tribal councils passed resolutions approving the project, signed by the tribal chair or president or his approved signatory.

In addition to asking about “traditional tribal beliefs,” “Christian traditions,” and “Native American Church,” the survey allowed respondents to indicate “Other” religious beliefs, but this response option was chosen so rarely that we did not report data.

Some tribes are very alert to the complex synthesis (and sometimes antithesis) that exists between aboriginal, Christian, and NAC beliefs and practices and the ways that associated healing traditions may interact with biomedicine to affect reservation health. They have begun to collaborate with researchers to understand such relationships and to formulate responses that promote positive health outcomes. See, for instance, Csordas (1999, 2000) and other articles about the Navajo Healing Project in the same issue.

Contributor Information

Eva M. Garroutte, Boston College and Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver

Janette Beals, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver.

Ellen M. Keane, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver

Carol Kaufman, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver.

Paul Spicer, Center for Applied Social Research at the University of Oklahoma.

Jeff Henderson, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver and the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health.

Patricia N. Henderson, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver and the Black Hills Center for American Indian Health

Christina M. Mitchell, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver

Spero M. Manson, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health at the University of Colorado Denver

References

- Abbott Patrick J. Traditional and western healing practices for alcoholism in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Substance Use and Misuse. 1998;33(13):2605–46. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht Stan L, Heaton Tim B. Secularization, higher education, and religiosity. Review of Religious Research. 1984;26(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Baird-Olson Karren. Retraditionalism and revitalization movements, plains. In: Crawford Suzanne J, Kelley Dennis F., editors. American Indian religious traditions: An encyclopedia. Vol. 3. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio; 2005. pp. 917–24. (R-Z) [Google Scholar]

- Baird-Olson Karren, Ward Carol. Recovery and resistance: The renewal of traditional spirituality among American Indian women. American Indian Culture and Research Journal. 2000;24(4):1–35. [Google Scholar]

- Beals Janette, Manson Spero M, Mitchell Christina M, Spicer Paul the AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: Walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):259–89. doi: 10.1023/a:1025347130953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals Janette, Manson Spero M, Whitesell Nancy R, Mitchell Christina M, Novins Douglas K, Simpson Sylvia, Spicer Paul. Prevalence of major depressive episode in two American Indian reservation populations: Unexpected findings with a structured interview. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2005;162(9):1713–22. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.9.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck Peggy V, Walters Anna Lee, Francisco Nia. The sacred: Ways of knowledge, sources of life. Tsaile, AZ: Navajo Community College; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Begay David H, Maryboy Nancy C. The whole universe is my cathedral: A contemporary Navajo spiritual synthesis. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2000;14(4):498–520. doi: 10.1525/maq.2000.14.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallahmi Benjamin, Argyle Michael. The psychology of religious behaviour, belief and experience. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berger Peter L. The sacred canopy: Elements of a sociological theory of religion. Garden City, NY: Anchor; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Boas Franz, Stocking George W., editors. The shaping of American anthropology, 1883–1911: A Franz Boas reader. New York: Basic Books; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden Henry Warner. American Indians and Christian missions: Studies in cultural conflict. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brod Rodney L, McQuiston John M. American Indian adult education and literacy: The first national survey. Journal of American Indian Education. 1983;22(2):1–16. Available online at: http://jaie.asu.edu/v22/V22S2Ame.html. [Google Scholar]

- Brown Joseph Epes. Teaching spirits: Understanding Native American religious traditions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Cajete Gregory. Look to the mountain: An ecology of indigenous education. Durango, CO: Kivaki Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Caplow Theodore, Bahr Howard M, Chadwick Bruce A. All faithful people: Change and community in Middletown’s religion. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran William G. Sampling techniques. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Stephen E. The return of the native: American Indian political resurgence. New York: Oxford University Press; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Stephen E, Hartmann Douglas. Ethnicity and race: Making identities in a changing world. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas Thomas J. Ritual healing and the politics of identity in contemporary Navajo society. American Ethnologist. 1999;26(1):3–23. [Google Scholar]

- Csordas Thomas J. The Navajo healing project. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2000;14(4):43–75. doi: 10.1525/maq.2000.14.4.463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport Frances Gardiner., editor. European treaties bearing on the history of the United States and its dependencies to 1648. Washington, DC: Carnegie Institution of Washington; 1917. [Google Scholar]

- de Angulo Jaime. Background of religious feeling. American Anthropologist. 1926;28(2):352–60. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria Vine., Jr . God is red: A native view of religion. New York: Grosset & Dunlap; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria Vine, Jr, Lytle Clifford M. American Indians, American justice. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Deloria Vine, Jr, Wildcat Daniel R. Power and place: Indian education in America. Golden, CO: American Indian Graduate Center and Fulcrum Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Durkheim Emile. The elementary forms of the religious life: A study in religious sociology. London: G. Allen & Unwin; 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards Yvonne. Cultural connection and transformation: Substance abuse treatment at Friendship House. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs. 2003;35(1):53–8. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10399993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericksen Eugene P. Problems in sampling Native American and Alaska Native populations. In. In: Sandefur Gary D, Rindfuss Ronald R, Cohen Barry., editors. Changing numbers, changing needs: American Indian demography and public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. pp. 113–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finke Roger, Stark Rodney. Religious economies and sacred canopies: Religious mobilization in American cities. American Sociological Review. 1988;53(1):41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup George H., Jr Why are women more religious? [accessed May 29, 2009];Gallup Tuesday Briefing. 2002 Dec 17; Available at http://www.gallup.com.

- Garrett Michael T, Wilbur Michael P. Does the worm live in the ground? Reflections on Native American spirituality. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 1999;27(4):193–206. [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte Eva Marie. Real Indians: Identity and the survival of Native America. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gill Sam D. Native American religions: An introduction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Grieco Elizabeth M, Cassidy Rachel C. Overview of race and Hispanic origin: Census 2000 brief. U.S. Census Bureau; 2001. [accessed December 5, 2006]. Available at http://www.census.gov/prod/2001pubs/c2kbr01-1.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hartz Paula R. Native American religions. New York: Facts on File; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Heidenreich C Adrian. Missionization, Northern Plains. In: Crawford Suzanne J, Kelley Dennis F., editors. American Indian religious traditions: An encyclopedia. Vol. 2. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC Clio; 2005. pp. 534–43. (J-P) [Google Scholar]

- Herberg Will. Protestant, Catholic, Jew: An essay in American religious sociology. Garden City, NY: Anchor Books; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Hultkrantz Ake. Native religions of North America: The power of visions and fertility. San Francisco, CA: Harper San Francisco; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Iannaccone Laurence R. The consequences of religious market structures. Rationality and Society. 1991;3(2):156–77. [Google Scholar]

- Indian Nations at Risk Task Force. Indian nations at risk: An educational strategy for action (Final report of the Indian Nations at Risk Task Force) Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin Lee. The dream seekers: Native American visionary traditions of the Great Plains. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin Lee. Freedom, law, and prophecy: A brief history of Native American religious resistance. American Indian Quarterly. 1997;21(1):35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Philip. Dream catchers: How mainstream America discovered native spirituality. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings Francis. The invasion of America: Indians, colonialism and the cant of conquest. New York: W. W. Norton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kidwell Clara Sue. Choctaws and missionaries in Mississippi, 1818–1918. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig Harold G, McCullough Michael E, Larson David B. Handbook of religion and health. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin Barry A, Mayer Egon, Keysar Ariela. American Religious Identification Survey. The Graduate Center of the City University of New York; 2001a. [accessed June 13, 2007]. Database online. Available at http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_studies/aris.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin Barry A, Mayer Egon, Keysar Ariela. [accessed June 13, 2007];American religious identification survey: Key findings. 2001b Available at http://www.gc.cuny.edu/faculty/research_briefs/aris/key_findings.htm.

- Kunitz Stephen J, Levy Jerrold E, Andrews Tracy J. Drinking careers. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Larson David B, Swyers James P, McCullough Michael E., editors. Scientific research on spirituality and health: A consensus report. Rockville, MD: National Institute for Healthcare Research; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Larson Gustave O. Brigham Young and the Indians. In: Ferris Robert G., editor. The American West: An appraisal. Santa Fe, NM: Museum of New Mexico; 1963. pp. 176–87. [Google Scholar]

- Levy Jerrold E. In the beginning. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Long J Scott, Freese Jeremy. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur Foundation. [accessed July 9, 2008];MIDMAC: Survey content and availability. 2006 Available at http://midmac.med.harvard.edu/research.html#survey.

- Martin Joel W. The land looks after us: A history of Native American religions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McNally Michael. Native American religious and cultural freedom: An introductory essay. The Pluralism Project at Harvard University; 2005. [Accessed July 9 2008]. Available at http://www.pluralism.org/research/profiles/display.php?profile=73332. [Google Scholar]

- Mehl-Madrona Lewis E. Native American medicine in the treatment of chronic illness: Developing an integrated program and evaluating its effectiveness. Alternative Therapies in Health and Medicine. 1999;5(1):36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill Ray M, Lyon Joseph L, Jensen William J. Lack of a secularizing influence of education on religious activity and parity among Mormons. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2003;42(1):113–24. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Alan, Stark Rodney. Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(6):1399–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Robert J. Native America, discovered and conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, and manifest destiny. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Millett David. Religion as a source of perpetuation of ethnic identity. In: Migus Paul M., editor. Sounds Canadian: Languages and cultures in multi-ethnic society. Toronto, Canada: Peter Martins; 1975. pp. 105–09. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan Thomas J. Rules for Indian courts (1892) In: Prucha Francis., editor. Documents of United States Indian policy. 2. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; [1892] 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Mullins Mark R. The organizational dilemmas of ethnic churches: A case study of Japanese Buddhism in Canada. Sociological Analysis. 1988;49(3):217–33. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel Joane. American Indian ethnic renewal: Red power and the resurgence of identity and culture. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli Maria. Holistic health care for native women: An integrated model. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(10):1573–75. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.10.1573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomb Steven T. Pagans in the promised land: Decoding the doctrine of Christian discovery. Golden, CO: Fulcrum; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Newport Frank. Religion most important to blacks, women, and older Americans. Gallup Poll Briefing. 2006 Nov 29;:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Niebuhr H Richard. The social sources of denominationalism. New York: Meridian Books; [1929] 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Norton Ilena M, Manson Spero M. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):856–60. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien, Crawford Suzanne J. Religion and healing in Native America: Pathways for renewal. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Pesantubbee Michelene E. Choctaw women in a chaotic world: The clash of cultures in the colonial Southeast. Albuquerque, NM: University of New Mexico Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Polling Report.com. [accessed July 2, 2007];Gallup Poll. 2007 May 10–13; Available at http://www.pollingreport.com/religion.htm.

- Princeton Religion Research Center. Religion in America 2002: Will America experience a spiritual transformation? Princeton, NJ: Princeton Religion Research Center; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Prucha Francis. The great father: The United States government and the American Indians. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Way Ruth, Johnson Sandie. Cultural practices in American Indian prevention programs. Juvenile Justice Journal. 2000;7(2):20–30. [Google Scholar]

- Smith Huston, Snake Reuben. One nation under God: The triumph of the Native American Church. Santa Fe, NM: Clear Light Publishers; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Snipp C Matthew. The size and distribution of the American Indian population: Fertility, mortality, migration, and residence. In: Sandefur Gary D, Rindfuss Ronald R, Cohen Barry., editors. Changing numbers, changing needs: American Indian demography and public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. pp. 17–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spider Emerson., Sr . The Native American Church of Jesus Christ. In: Treat James., editor. Native and Christian: Indigenous voices on religious identity in the United States and Canada. New York: Routledge; 1996. pp. 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS Inc. SPSS. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Rodney. Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(3):495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Rodney, Finke Roger. Acts of faith: Exploring the human side of religion. Berkeley, CA: University of California; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Rodney, Finke Roger. Beyond church and sect: Dynamics and stability in religious economies. In: Jelen Ted., editor. Sacred markets, sacred canopies: Essays on religious markets and religious pluralism. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield; 2002. pp. 31–62. [Google Scholar]

- Stata. Stata statistical software. College Station, TX: Stata Corporation; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz Paul B. Pipe, Bible, and peyote among the Oglala Lakota: A study in religious identity. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Omer C. Peyote religion: A history. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- St Pierre Mark, Soldier Tilda Long. Walking in the sacred manner: Healers, dreamers, and pipe carriers–Medicine women of the Plains Indians. New York: Simon & Schuster; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Sullins D Paul. Gender and religion: Deconstructing universality, constructing complexity. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;112(3):838–80. [Google Scholar]

- Talamantez Inez. In the space between the earth and the sky: Contemporary Mescalero Apache ceremonialism. In: Sullivan Lawrence E., editor. Native religions and cultures of North America. New York: Continuum; 2000. pp. 142–59. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Wayne L, Carroll Jackson W, Hoge Dean R. Growth or decline in Presbyterian congregations. In: Roozen David A, Kirk Hadaway C., editors. Church and denominational growth. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press; 1993. pp. 188–207. [Google Scholar]

- Thornton Russell. Tribal membership requirements and the demography of “old” and “new” Native Americans. Population Research and Policy Review. 1997;16(1):33–42. [Google Scholar]

- Tinker George E. Missionary conquest: The gospel and Native American cultural genocide. Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Treat James., editor. Native and Christian: Indigenous voices on religious identity in the United States and Canada. New York: Routledge; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- U.S . Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. [accessed September 24, 2007];Tribal leaders directory. 2007 Available at http://library.doi.gov/internet/triballeaders9.pdf.

- U.S. Indian Health Service. Some denominational preferences among the Oglalas. Pine Ridge Research Bulletin. 1969:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Vecsey Christopher. Where two roads meet. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Warner R Stephen. Work in progress toward a new paradigm for the sociologica study of religion in the United States. American Journal of Sociology. 1993;98(5):1044–93. [Google Scholar]