Background: The molecular details of the effects of DOPAL on α-synuclein misfolding and oligomerization are unknown.

Results: DOPAL forms Schiff-base and Michael-addition adducts with α-synuclein Lys residues.

Conclusion: DOPAL modification inhibits aS fibrillization and reduces binding of α-synuclein to synaptic-like vesicles.

Significance: DOPAL modification may interfere with the normal functions of α-synuclein and favor the buildup of potentially toxic oligomers.

Keywords: α-synuclein, dopamine, oxidative stress, Parkinson disease, protein aggregation, DOPAL, oligomers

Abstract

Oxidative deamination of dopamine produces the highly toxic aldehyde 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL), enhanced production of which is found in post-mortem brains of Parkinson disease patients. When injected into the substantia nigra of rat brains, DOPAL causes the loss of dopaminergic neurons accompanied by the accumulation of potentially toxic oligomers of the presynaptic protein α-synuclein (aS), potentially explaining the synergistic toxicity described for dopamine metabolism and aS aggregation. In this work, we demonstrate that DOPAL interacts with aS via formation of Schiff-base and Michael-addition adducts with Lys residues, in addition to causing oxidation of Met residues to Met-sulfoxide. DOPAL modification leads to the formation of small aS oligomers that may be cross-linked by DOPAL. Both monomeric and oligomeric DOPAL adducts potently inhibit the formation of mature amyloid fibrils by unmodified aS. The binding of aS to either lipid vesicles or detergent micelles, which results in a gain of α-helix structure in its N-terminal lipid-binding domain, protects the protein against DOPAL adduct formation and, consequently, inhibits DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization. Functionally, aS-DOPAL monomer exhibits a reduced affinity for small unilamellar vesicles with lipid composition similar to synaptic vesicles, in addition to diminished membrane-induced α-helical content in comparison with the unmodified protein. These results suggest that DOPAL could compromise the functionality of aS, even in the absence of protein oligomerization, by affecting the interaction of aS with lipid membranes and hence its role in the regulation of synaptic vesicle traffic in neurons.

Introduction

Parkinson disease (PD),3 the second most common age-related neurodegenerative disorder after Alzheimers disease, is a progressive movement disorder that affects ∼1–2% of the population over 65 years of age (1). The clinical symptoms (resting tremors, bradykinesia, rigidity, and postural dysfunction) result predominantly from the loss of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra (SN) pars compacta and from dopamine (DA) deficiency in the striatum (1–3). The histopathological hallmark of PD is the presence of intraneuronal deposits containing fibrillar aggregates of the presynaptic protein α-synuclein (aS) (called Lewy bodies and Lewy neurites) (4, 5). Missense mutations and genomic multiplication of the aS gene have been linked to autosomal dominant familial PD (6).

Although aS is expressed throughout the brain, formation of protein deposits specifically in dopaminergic neurons in the SN suggests a connection between aS aggregation and DA metabolism. This hypothesis is corroborated by the fact that the neurotoxicity associated with aS overexpression is remarkably reduced when DA synthesis is inhibited (7), and the toxicity of oxidized catechol metabolites is exacerbated by the expression of WT aS or the PD-linked A53T variant (8). The fact that DA itself, at concentrations found in dopaminergic neurons, is not able to impair neuron functionality and cause cell death as found in PD (9) suggests that another molecule produced via DA metabolism could be responsible for this selective neuronal degeneration (10).

The enzymatic oxidation of DA by monoamine oxidase isoforms (MAO-A and MAO-B) produces the highly cytotoxic aldehyde 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde (DOPAL) (11), levels of which are enhanced in post-mortem brains of PD patients (12). Elevated DOPAL levels in PD are suggested to result from a combination of decreased vesicular uptake of cytosolic DA (decreased by ∼89%) and decreased DOPAL detoxification by the enzyme aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) (decreased by 70%) (13), which converts DOPAL to its non-toxic metabolite 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid. Interestingly, the inhibition of ALDH is sufficient to cause a parkinsonian phenotype in mice (14). Furthermore, the interaction of aS with DOPAL is reported to lead to an increase of the levels of potentially toxic aS aggregates. For instance, the injection of DOPAL into the intranigral region of mouse brains results in the formation of aS oligomers accompanied by death of dopaminergic neurons (15). This means that the interaction between aS and DOPAL might play a central role in the selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons and could explain the synergism between the toxicity of DA metabolism and aS toxicity. Unfortunately, the molecular details of the formation of aS oligomers induced by DOPAL remain unclear.

In this work, we demonstrate that Schiff-base (SB) and Michael-addition (MA) adducts formed between DOPAL and Lys residues located in the N-terminal domain of aS are associated with the stabilization of protein oligomers, likely by acting as protein cross-linkers. Interestingly, helical folding of the aS N-terminal domain, which occurs upon binding to lipid membranes, has a protective effect against DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization. However, DOPAL is able to compromise the ability of the aS monomer to interact with lipid vesicles, even in the absence of protein oligomerization, which might represent a potential mechanism for loss-of-function of aS monomers in the regulation of synaptic vesicle trafficking and exocytosis in neurons.

Experimental Procedures

Expression and Purification of aS

The expression and purification of aS were performed as described previously (16). For production of 15N-aS or 13C,15N-aS, cells were grown in minimal media containing 15N-labeled ammonium chloride or 15N-labeled ammonium chloride plus 13C-labeled glucose, respectively, and the protein expression was induced with 0.8 mm isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 4 h at 37 °C.

Preparation of aS-DOPAL Species

DOPAL was synthesized via the pinacol-pinacolone rearrangement of epinephrine (17). A solution of 50 μm recombinant aS monomer in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, was incubated at 37 °C under agitation (350 rpm) in a Thermomixer (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) in the presence of varying concentrations of DOPAL. Aliquots were withdrawn at different times and analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE or size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (void volume, 7.8 ml) (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). The percentage of the different oligomeric states of the protein, in the presence or absence of DOPAL, was determined by quantitative densitometry of proteins, in SDS-PAGE stained with Coomassie Blue, using ImageJ software (18). For the production of aS-DOPAL monomer, 10 μm aS monomer in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, was incubated in the presence of DOPAL (DOPAL/protein ratio = 5, 10, or 20) at 37 °C for 24 h (no agitation). aS-DOPAL monomers obtained under these conditions were denoted as aS-DOPAL(1:5), aS-DOPAL(1:10), and aS-DOPAL(1:20), respectively. After removal of unbound DOPAL by dialysis (cutoff, 3.5 kDa), aS-DOPAL monomer was lyophilized and stored at −20 °C for further use. The oligomeric state of aS was evaluated by SDS-PAGE and SEC. Using this protocol, we were able to produce aS-DOPAL essentially in the monomeric state (>95%).

Preparation of SUV

1,2-Dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DOPE), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine (DOPS) and 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). Phospholipid mixtures containing 60% DOPC, 25% DOPE, and 15% DOPS (molar concentrations) were prepared by drying a mixture of the different lipids dissolved in chloroform under nitrogen gas and resuspending the lipid film in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl at 25 °C. Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by pulse-sonicating the phospholipid suspensions in a bath sonicator for 10 min in 2-min increments. The size of the resulting SUVs (hydrodynamic radii of 30–50 nm) was determined by dynamic light scattering using a Zetasizer Nano ZS instrument (Malvern Instruments, Worcestershire, UK).

NMR Spectroscopy

NMR experiments were performed using 500 MHz (National Nuclear Magnetic Center at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) or 600 MHz (Weill Cornell Medical College, New York) Bruker Avance spectrometers equipped with cryogenic probes. Phase-sensitive two-dimensional 1H-15N heteronuclear single quantum coherence (1H-15N HSQC) spectra were recorded using Echo-anti-Echo gradient selection. TopSpin 3.2 was used for data acquisition. All spectra were processed with NMRPipe (19) and analyzed with CCPN software. Amide resonance assignments were performed according to previously reported chemical shift assignments for intrinsically unfolded aS (20–22). HNCA experiments of SDS-bound 13C,15N-aS provided α-carbon chemical shifts for secondary shift analysis. For this experiment, 40 mm deuterated SDS was added to 200 μm double-labeled aS-unmodified (aSunmod) or aS-DOPAL(1:10) monomer. Binding to SUV for both aSunmod and aS-DOPAL was monitored via 1H-15N HSQC experiments with varying lipid concentrations. All NMR experiments were conducted at 10 °C, except those including SDS, which were carried out at 25 °C. Protein concentration was 200 μm in the presence of 20 mm sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, 10% D2O. Kinetic experiments were performed at 15 °C instead of 10 °C to increase the rate of DOPAL oxidation.

Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement (PRE)

Considering that aS has no Cys residues, protein variants G31C, A85C, and P120C were generated by using site-directed mutagenesis. The purified mutant proteins were labeled with 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5,-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methyl-methanethiosulfonate (MTSL) (Toronto Research Chemicals, Canada) as described (23). Briefly, 8 mm MTSL (prepared in 100% DMSO) was added to protein samples (300 μm in 50 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5) and then incubated for 4 h at 25 °C (300 rpm). The mixture was then dialyzed against MilliQ water and lyophilized for further use. For aS-DOPAL samples, free MTSL was removed by dialysis against buffer and then the protein was diluted to 10 μm and incubated with 100 μm DOPAL (aS-DOPAL(1:10)) for 24 h at 37 °C (no agitation). Removal of unbound DOPAL was done by dialysis against MilliQ water. PRE was measured by collecting 1H-15N HSQC spectra using 200 μm aS or aS-DOPAL(1:10) monomer at 10 °C. For control diamagnetic samples, ascorbic acid (5-fold molar excess in relation to the protein) was added to the MTSL spin-labeled sample to reduce the nitroxide spin label. The intensities of cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of both the spin-labeled and reduced samples were measured, and their ratio was calculated.

Mass Spectrometry (MS)

Samples of aS-DOPAL-M were prepared by incubation of 100 μm aS with 1 mm DOPAL at 37 °C and 350 rpm for 24 h in 150 mm ammonium bicarbonate, pH 7.8, followed by isolation of modified monomer by SEC and lyophilization. After that, 100 μg of protein were dissolved in 7 m urea and 2 m thiourea. and the samples were then diluted to 1 m urea with 100 mm Tris-HCl buffer, pH 8.5. In sequence, MS-grade trypsin (Promega) was added (1:50 protease/substrate (w/w)) for overnight digestion at 37 °C. Proteolysis was stopped by adding 1% formic acid. Digested samples were desalted in a C18 spin column (Harvard Apparatus) following the manufacturer's instructions. The digested and desalted samples were dissolved in 0.1% formic acid to a final protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. Two micrograms of each peptide sample were injected by a nanoHPLC system nanoLC Ultra 2d (Eksigent Technologies) on a self-packed 75-μm inner diameter, 10-cm-long column, packed with Reprosil-Pur C18-AQ, 3 μm, 120 Å, coupled to an LTQ XL Orbitrap ETD mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific). Chromatography was carried out at 300 nl/min of flow, and mobile phase buffer A was 95% water, 5% acetonitrile, and 0.1% formic acid, and mobile phase buffer B was 95% acetonitrile, 5% water, and 0.1% formic acid. The analytical column was equilibrated with buffer A for 10 min prior to sample injection. The gradient duration was 60 min (5–45% B over 45 min, followed by 45–90% B over 5 min, and 90% B for another 10 min). The mass spectrometer acquisition strategy consisted of data-dependent acquisition, which automatically switches between full scan MS (Fourier transform MS, 60,000 resolution, 500-ms accumulation time, AGC 1 × 106 ions, range 300–2000 m/z) followed by fragmentation with higher energy collisional dissociation fragmentation of the six most intense ions. Each fragmentation was recorded in a high resolution spectrum (Fourier transform MS, 15,000 resolution, 100-ms accumulation time, AGC 5 × 104 ions). The recorded spectra were analyzed by Peptide Spectrum Matching, a method in which an algorithm attempts to find similarity between each experimental spectrum and an in silico generated set of spectra, achieved by a theoretical digestion of a sequence in a database and subsequent creation of a “bar code spectrum.” For direct infusion of MS/MS data acquisition, each sample was diluted using acetonitrile/water/methanol 1:1:2 and 0.1% formic acid to a final concentration of 1.0 μg/μl. Using a syringe pump, 500 μl of the solution was infused via electrospray ionization at a flow of 1.0 μl/min. The mass spectrometer acquisition strategy was the same as LC-MS/MS, with the difference of using five microscans per MS1.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC binding experiments were performed in a nano ITC low volume instrument (TA Instruments, New Castle, PA) with a fixed gold cell by titrating 100 mm SUV (60% DOPC, 25% DOPE, 15% DOPS) into 25 μm aSunmod or aS-DOPAL(1:10) monomer solution. All experiments were performed at 37 °C using 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl as buffer. The data were acquired using ITCRun data acquisition software. The incremental ITC experiments consisted of 24 injections of 2-μl at 240-s intervals with stirring speed of 250 rpm.

Far-UV Circular Dichroism (CD)

CD measurements were performed using an AVIV Circular Dichroism Spectrometer, Model 410 (Aviv Biomedical Inc., Lakewood, NJ). Solutions of 40 μm aSunmod monomer or aS treated with different concentrations of DOPAL (DOPAL/protein ratio = 5, 10 and 20) in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl, in the absence or presence of varying concentration of SUVs were analyzed in a 0.2-mm quartz cuvette at 25 °C. The ellipticity at 222 nm was measured, and the background associated with buffer or SUV solutions was subtracted. The mean residue molar ellipticity at 222 nm (θMR, 222) was determined using Equation 1,

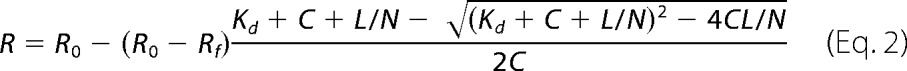

where θ222 is the measured ellipticity at 222 (millidegrees); C is the protein concentration (in molar), n = 140 (number of amino acid residues in aS), and l is the path length of the cuvette in centimeters (0.02 cm). Lipid titration curves generated by plotting [θ]MR, 222 versus the lipid concentration were analyzed as described previously (24, 25) by fitting to Equation 2,

|

where R is the measured [θ]MR 222 at a given lipid concentration; R0 is the [θ]MR, 222 in the absence of lipid; Rf is the [θ]MR, 222 in the presence of saturating lipid; L is the total lipid concentration; C is the total protein concentration; Kd is the apparent macroscopic dissociation equilibrium constant, and N is the binding stoichiometry (lipids/protein). The maximum helical content of aSunmod and aS-DOPAL was determined as described previously (26, 27).

Determination of H2O2 Content

The concentration of free H2O2 was evaluated using a fluorometric assay that measured the amount of resorufin produced from Amplex Red (Life Technologies, Inc.) in the presence of horseradish peroxidase (28). These assays were performed in a 96-well microplate at 37 °C and 350 rpm. The resorufin fluorescence was measured by excitation at 571 nm and emission at 585 nm in a Cary eclipse fluorimeter (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA).

Chemical Modification of Lysines

To evaluate the role of lysines in DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization, 100 μm aS in 100 mm phosphate buffer at pH 8.0 was incubated for 6 h in the presence or absence of 1.5 mm citraconic anhydride (CA), which causes chemical modification of the lysines of the protein (29). Lys-blocked aS was isolated from free CA by SEC. The treatment of aS with CA did not cause any detectable protein oligomerization (data not shown). Next, Lys-blocked aS and aS-unmod were incubated with DOPAL, and the formation of oligomers was investigated using SEC and SDS-PAGE.

Results

DOPAL Induces the Formation of Fibril-incompetent Soluble Oligomers of aS in Vitro

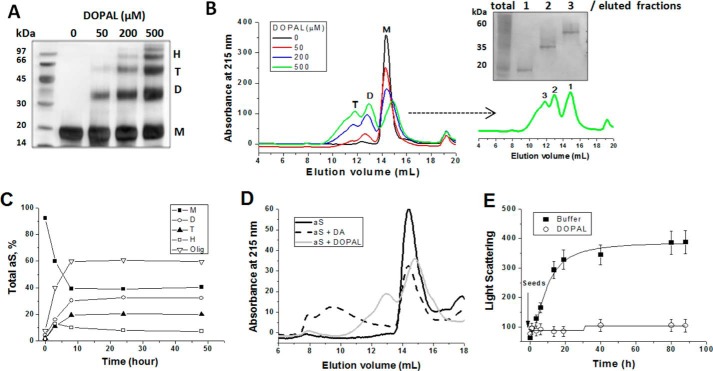

Fig. 1A shows that DOPAL promotes, in a concentration-dependent manner, the formation of soluble oligomers of aS. No effect of the treatment of aS-DOPAL sample with the protein cross-linker glutaraldehyde was observed on the gel profile, suggesting that these oligomers are not dissociated from larger species under SDS denaturing conditions (data not shown). In addition, these oligomers were stable enough to be isolated by SEC, and further analysis by SDS-PAGE indicates they are predominantly dimers and trimers of aS-DOPAL, denoted as aS-DOPAL-D and aS-DOPAL-T, respectively (Fig. 1B). Fig. 1C shows that the populations of aS-DOPAL oligomers do not evolve efficiently to larger oligomers even after long term incubation, although a small population of larger species is present after 1st hour of incubation (denoted as H) (Fig. 1C). This result contrasts with the effect of DA, which induces the formation of large oligomers of aS (Fig. 1D). Although it has been suggested that DA specifically stabilizes aS oligomers, the presence of fibrils can be observed after long term incubation with DA (30). This misleading conclusion might be attributed to the fact that the effect of DA oxidation products on ThT fluorescence has been neglected. Oxidized derivatives of DA strongly quench ThT fluorescence, which can mask the formation of ThT-positive fibrillar aggregates (31).

FIGURE 1.

DOPAL induces the formation of soluble oligomers of aS. A, 50 μm aS in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with agitation (350 rpm) in the presence of varying concentrations of DOPAL (0, 50, 200, and 500 μm), and the formation of oligomers was analyzed by 12% SDS-PAGE (M, monomer; D, dimer; T, trimer; H, large oligomers; Olig, total oligomers). B, SEC analysis of the samples from A (24 h of incubation) using Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (void volume = 7.8 ml). The eluted peaks (fractions 1–3) obtained from aS/DOPAL, 1:10 (light green), was further analyzed by SDS-PAGE (right panel). C, quantitative densitometry of proteins was used to determine the content of the different oligomer species produced in B as a function of the time of incubation. D, effect of DA and DOPAL on aS oligomerization after incubation of the protein (50 μm) in the presence of 250 μm of either DA or DOPAL for 24 h. E, effect of DOPAL on aS fibrillation under seeding conditions. 50 μm aS plus seeds (5% w/w) was incubated in the presence or absence of 250 μm DOPAL at 37 °C (no agitation). The kinetics of fibrillation were followed by the increase in light scattering, monitored by the intensity of the emission at 525 nm upon excitation at 520 nm. The results are presented as mean ± S.D. of three experiments.

The rate of aS fibrillation can be increased by abolishing the rate-limiting nucleation step through the addition of pre-formed fibrils (seeds) to the aggregating solution, which act as nuclei for monomer accretion and fibril growth (32). Because DOPAL oxidation products (essentially DOPAL-quinone, referred to here as DPQ) also strongly quench ThT fluorescence, aS fibrillation in the presence of DOPAL cannot be properly evaluated by using ThT (31) unless DOPAL oxidation is inhibited (see below). For this reason, we monitored aS aggregation/fibrillation using light scattering. Fig. 1E shows that the aSunmod displayed a remarkable increase in light scattering after the addition of aS seeds, while no effect of the seeds was observed for aS incubated in the presence of DOPAL. This implies that aS-DOPAL species cannot be effectively incorporated into pre-formed nuclei, preventing the growth of fibrils. The absence of any increase in light scattering intensity also suggests that the formation of non-fibrillar high molecular aggregates of aS-DOPAL does not occur under these conditions.

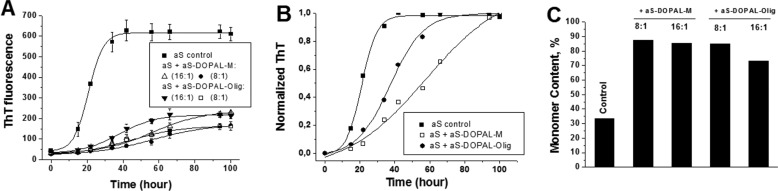

aS-DOPAL Species Are Potent Inhibitors of aS Fibrillation

Given that aS-DOPAL is not incorporated into aS seeds, we evaluated whether aS-DOPAL species may influence the fibrillation of aSunmod. Monomeric aSunmod was incubated in the presence of SEC-purified aS-DOPAL-M or aS-DOPAL-Olig, and the formation of fibrils monitored by ThT fluorescence. Note that free DOPAL and its DPQ oxidation by-products are removed by SEC, enabling the use of the ThT assay. Fig. 2A shows that both aS-DOPAL-M and aS-DOPAL-Olig act as strong inhibitors of aS fibrillation at concentrations as low as 3 μm (molar ratio of aSunmod monomer to aS-DOPAL of 16:1). Analysis of the kinetic parameters extracted from the normalized curves (Fig. 2B) revealed that the lag time duration and t½ (time required to reach 50% of maximum fibrillation) both increased in the presence of the aS-DOPAL-M or -Olig, while the elongation rates decreased (Table 1). Determination of the monomer content at the end of the aggregation reactions confirmed the anti-fibrillogenic activity of aS-DOPAL-M and aS-DOPAL-Olig (Fig. 2C). These results indicate that a small population of aS-DOPAL species can interfere with the conversion of unmodified aS monomer into fibrils and that this ability is shared by both monomeric and oligomeric forms of aS-DOPAL.

FIGURE 2.

Inhibitory activity of aS-DOPAL species on aSunmod fibrillation. A, aSunmod was incubated at 37 °C and agitation (350 rpm) in the absence or presence of SEC-purified aS-DOPAL-M or aS-DOPAL-Olig at a molar ratio of 1:8 and 1:16 (aS-DOPAL/aSunmod), and the formation of fibrils measured through ThT fluorescence. B shows the normalized kinetic curves obtained in A (molar ratio of 1:16). The kinetic assays were performed in sextuplicate and the results are expressed as mean ± S.D. C, content of aS monomer at the end of the aggregation assay. The population of the monomer was estimated by using SEC and expressed as the peak area of the monomer, at the final time, divided by peak area at the initial time. In the case of aSunmod incubated in the presence of aS-DOPAL-M, the peak areas were corrected by the values obtained for aS-DOPAL-M alone. Control corresponds to aSunmod incubated in the absence of aS-DOPAL species.

TABLE 1.

Effect of aS-DOPAL-M and aS-DOPAL-Olig on the kinetic parameters for the fibrillation of unmod-aS

| Sample | t½ | Lag time | Elongation rate |

|---|---|---|---|

| h | h | 10−3 h−1 | |

| aSunmod (buffer) | 21.2 ± 2.8 | 9.1 ± 1.1 | 37.4 ± 4.8 |

| aSunmod + aS-DOPAL-M (16:1) | 55.4 ± 6.5 | 14.1 ± 1.6 | 12.1 ± 1.4 |

| aSunmod + aS-DOPAL-Olig (16:1) | 37.7 ± 3.6 | 12.1 ± 1.2 | 18.9 ± 1.8 |

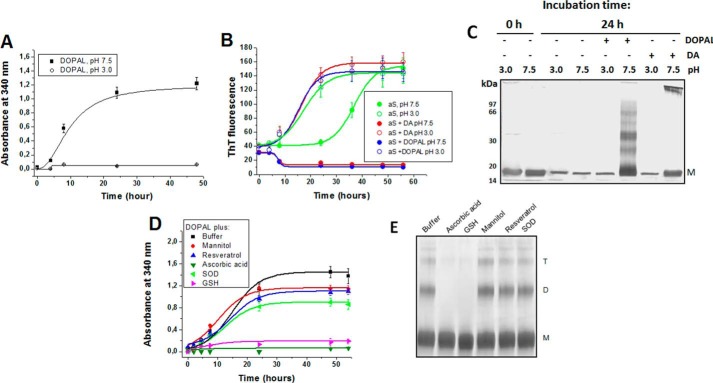

DOPAL-induced aS Oligomerization Requires DOPAL Oxidation

The spontaneous oxidation of DOPAL is largely inhibited at acidic pH, as demonstrated by the lower absorbance at 340 nm (which reports on the formation of quinone) of DOPAL solutions at pH 3.0 compared with pH 7.5 (Fig. 3A). In this context, we evaluated the effect of pH on DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization. An increase in ThT fluorescence is observed when aSunmod is incubated at pH 7.5 or 3.0, indicating the formation of amyloid fibrils. Aggregation occurs more rapidly at pH 3.0, as observed previously (33). aS plus DOPAL at pH 7.5 did not display any increase in ThT fluorescence due to the fluorescence quenching caused by DPQ (Fig. 3B). However, when this incubation was performed at pH 3.0, the oxidation of DOPAL was prevented, and an increase in ThT fluorescence was observed. Notably, DOPAL itself does not cause any quenching of ThT fluorescence when its oxidation is inhibited, e.g. by acid pH (31). SDS-PAGE analysis indicates that the formation of dimers and trimers occurs in aS incubated with DOPAL at pH 7.5 but not at pH 3.0 (Fig. 3C). For DA also, high molecular weight aS oligomers were observed only after incubation at pH 7.5 and not at pH 3.0. For both DOPAL and DA, incubation at pH 3.0 does not alter the fibrillization kinetics observed for aSunmod alone. Taken together, these findings clearly indicate that DOPAL, similar to DA, has no effect on aS oligomerization or fibrillation under conditions in which its oxidation is prevented.

FIGURE 3.

Role of DOPAL oxidation on DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization. A, effect of pH (3.0 and 7.5) on the kinetics of oxidation of DOPAL monitored as a function of time through the increase in absorbance at 340 nm (formation of DPQ). B, effect of pH on the fibrillation of 50 μm aS, in the presence or absence of DA or DOPAL (250 μm) was monitored using ThT fluorescence. C, SDS-PAGE of the samples obtained in B. D, effect of 1 mm ascorbic acid, 1 mm selegiline, 1 mm melatonin, 1 mm trans-resveratrol, 1 mm reduced glutathione (GSH), 50 mm mannitol, or 60 units of SOD on DOPAL oxidation measured by the intensity of the absorbance at 340 nm. E, 50 μm aS in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, was incubated in the presence of 250 μm DOPAL plus antioxidants, and the formation of oligomers after 3 days of incubation (37 °C, agitation) was determined by SDS-PAGE. The experiments in B and D were performed in sextuplicate, and the results are represented as mean ± S.D.

Taking into account the importance of DOPAL oxidation in the formation of aS-DOPAL oligomers, the effect of the antioxidants ascorbic acid (1 mm), selegiline (1 mm), melatonin (1 mm), trans-resveratrol (1 mm), reduced glutathione (GSH) (1 mm), mannitol (50 mm), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) (60 units) was evaluated. We found that ascorbic acid and GSH are capable of inhibiting the oxidation of DOPAL and diminish the DOPAL-stimulated formation of aS dimers and trimers (Fig. 3, D and E). The other antioxidants did not exert a significant effect on DOPAL oxidation or aS oligomerization at these concentrations, although SOD, a selective scavenger of superoxide radicals, reduced the reactive oxygen species (ROS) generated in the early stage of DOPAL oxidation, notably in the presence of aS, but it lost effectiveness over time, potentially due to the inactivation of SOD by direct reaction with DOPAL (data not shown).

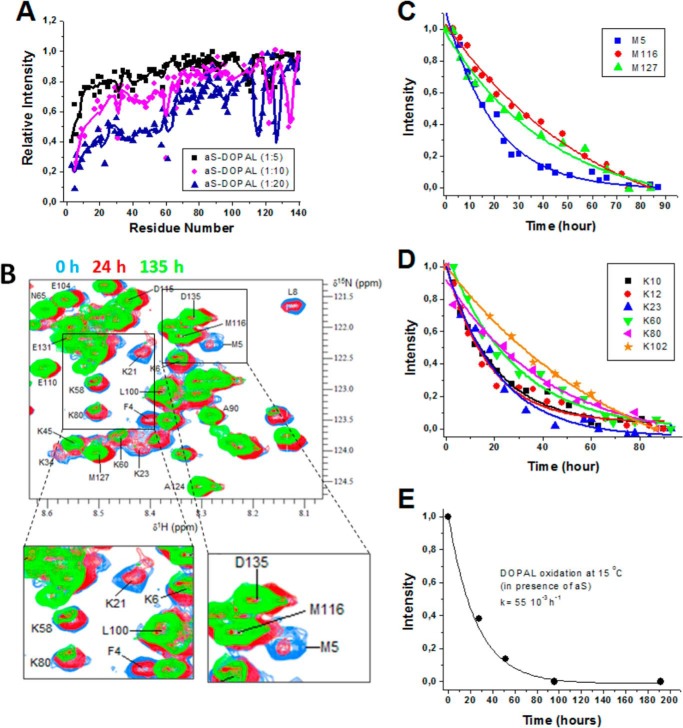

DOPAL Interacts with N-terminal Domain of aS

Fig. 4A shows that DOPAL causes a concentration-dependent decrease of NMR cross-peak intensity in 1H-15N HSQC spectra of monomeric aS. The effects are localized to residues in the N-terminal domain of the protein, especially to residues 1–60, as well as to the vicinity of Met-116 and Met-127 in the C-terminal tail. To investigate whether the DOPAL-induced spectral changes occur synchronously with DOPAL oxidation, we compared the rates of oxidation of DOPAL with the rates for the appearance of perturbations in aS HSQC spectra caused by DOPAL. 1H-15N HSQC spectra were recorded at intervals of 3 h during a total period of 7 days. In parallel, the oxidation of DOPAL was monitored using an identical sample under the same conditions of the NMR experiment. Fig. 4B shows the 1H-15N HSQC spectra for aS after 0, 24, and 135 h of incubation at 15 °C. Resonance intensities were fit using a single exponential to extract intensity decay rate constants for individual residues, which were observed to be higher for residues located in the N-terminal region of the protein (Table 2). For example, the decay rate of the Met-5 signal is significantly higher than that of Met-116 and Met-127 (58.5 × 10−3 compared with 15.7 × 10−3 and 13.9 × 10−3 h−1, respectively) (Fig. 4C and Table 2). Similarly, decay rate constants for Lys residues at the N terminus are higher than for those at the C terminus (Fig. 4D). The rate constant obtained for the oxidation of DOPAL (55 × 10−3 h−1) (Fig. 4E) is in the same range as the rate constant observed for the intensity decrease of residues in the N-terminal domain of aS, strongly suggesting that these processes occur simultaneously. Together, these data indicate that spectral changes in the N-terminal portion of aS are caused by DOPAL oxidation and that the N-terminal region is more susceptible to DOPAL-induced structural modifications than the C terminus of the protein.

FIGURE 4.

Conformational perturbations of aS monomer caused by DOPAL. A, ratio of peak intensities of 200 μm 15N-aS monomer after incubation in the presence or absence of 1, 2, and 4 mm DOPAL for 24 h at 15 °C (no agitation), normalized by the intensity of the signal in the absence of DOPAL, plotted versus residue number. In all these samples, aS was found essentially as a monomer (∼95% monomer). B, effect of time (0, 24, and 135 h) on the 15N-1H HSQC spectra of a solution containing 100 μm aS monomer plus fresh DOPAL (500 μm) at 15 °C. Ratio intensity of cross-peaks for Met residues (Met-5, Met-116, and Met-127) (C) and lysines (D) was plotted as a function of the time of incubation, and the kinetic rate constants were determined using an exponential decay fitting (Table 2). E, kinetics of the oxidation of DOPAL (500 μm), in the presence of 200 μm aS, was followed by reverse phase-HPLC (Pursuit C18 column, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA), with detection by absorbance at 215 nm and isocratic elution using 0.1% TFA, 10% methanol in water as the solvent. Kinetic rate constant for DOPAL oxidation was determined through the values of integrated peak area, obtained at different times of incubation, and fitted using a single exponential decay.

TABLE 2.

Rate constants for the effect of DOPAL on the intensity of cross-peaks of certain aS residues obtained from time-dependent 1H-15N-HSQC spectra with single-exponential fits

aS was incubated in the presence of DOPAL (protein/DOPAL = 1:5) at 15 °C, no agitation.

| Residue | k |

|---|---|

| 10−3 h−1 | |

| Phe-4 | 67.6 |

| Met-5 | 58.5 |

| Lys-10 | 50.5 |

| Leu-8 | 57.8 |

| Ala-11 | 58.8 |

| Lys-12 | 56.3 |

| Glu-20 | 56.6 |

| Lys-21 | 32.3 |

| Thr-22 | 48.8 |

| Lys-23 | 46.8 |

| Ala-30 | 43.8 |

| Ser-42 | 49.3 |

| Thr-44 | 68.4 |

| Lys-45 | 62.0 |

| Lys-58 | 29.3 |

| Thr-59 | 44.2 |

| Lys-60 | 35.4 |

| Gly-67 | 19.8 |

| Thr-75 | 15.4 |

| Lys-80 | 23.4 |

| Lys-102 | 13.0 |

| Asp-115 | 13.1 |

| Met-116 | 15.7 |

| Met-127 | 13.9 |

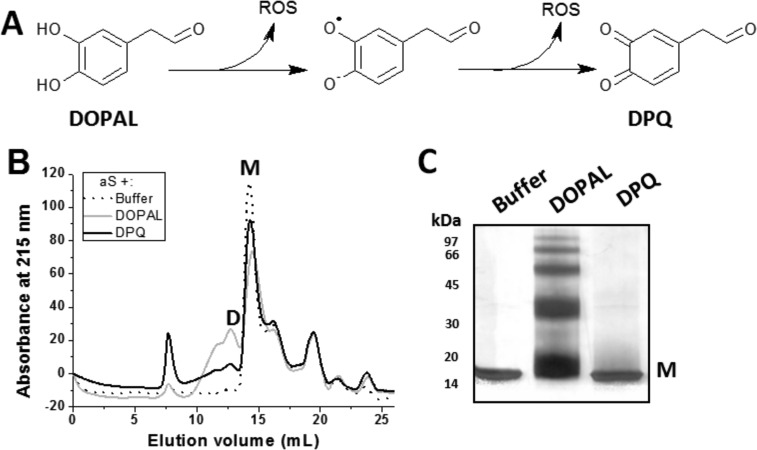

DPQ and DOPAL Have Different Effects on aS Oligomerization

DOPAL undergoes spontaneous oxidation in aerated aqueous solution, resulting in the formation of quinone derivatives with concomitant generation of ROS (Fig. 5A) (17). Considering that DOPAL oxidation is a key step for its effect on aS oligomerization, we compared the effect of DOPAL with its oxidized form, DPQ. DPQ was prepared by incubation of 1 mm DOPAL at 37 °C and agitation for 48 h, resulting in a brown-colored solution with enhanced absorbance at 340 nm. Although the incubation of aS with freshly prepared DOPAL lead to the formation of dimers and trimers, the incubation with DPQ produced a small population of large oligomers (Fig. 5, B and C), somewhat similar to those found after incubation with DA. This means that DPQ and DOPAL may have different mechanisms for inducing aS oligomerization. From these data, we hypothesized that the generation of ROS from DOPAL oxidation and its effect on aS might be important for the effects of DOPAL on aS.

FIGURE 5.

Effect of DPQ on aS oligomerization. A, DOPAL undergoes spontaneous oxidation in aerated aqueous solution, resulting in the formation of DPQ with concomitant generation of ROS. B, SEC analysis of 50 μm aS in 20 mm NaPB, pH 7.5, incubated in the presence of DOPAL or DPQ (250 μm) for 3 days at 37 °C and agitation. C shows the corresponding SDS-PAGE analysis of the samples that were injected on the SEC column. M, monomer; D, dimer.

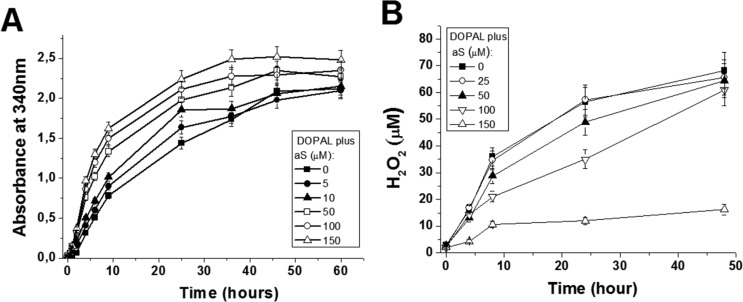

The influence of aS on both the kinetics of oxidation of DOPAL and the formation of ROS generated during this process was also investigated. The rate of formation of DPQ, monitored by the absorbance at 340 nm, is significantly enhanced, in a concentration-dependent manner, by the presence of aS (Fig. 6A). Considering that DOPAL oxidation generates not only DPQ but also ROS, which, in turn, might be converted to H2O2, the influence of aS on the H2O2 levels produced from DOPAL oxidation was investigated. Fig. 6B indicates that the level of H2O2 detected decreased with increasing aS concentrations. This suggests that aS might react either with the free radicals generated from DOPAL oxidation and/or with H2O2. In both cases, a reduction in the levels of H2O2 would be observed. Collectively, these results suggest that aS might act as a scavenger of ROS generated from DOPAL oxidation and, consequently, stimulate the oxidation of DOPAL by shifting the equilibrium of the reaction toward to the formation of DPQ.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of aS on DOPAL oxidation. A, rate of oxidation of 250 μm DOPAL in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 37 °C, monitored by the absorbance at 340 nm, in the presence of varying concentrations of aS (0–150 μm). B shows the effect of aS on the levels of H2O2 produced from the oxidation of DOPAL. The kinetic assays were performed in triplicate, and the results are represented as mean ± S.D.

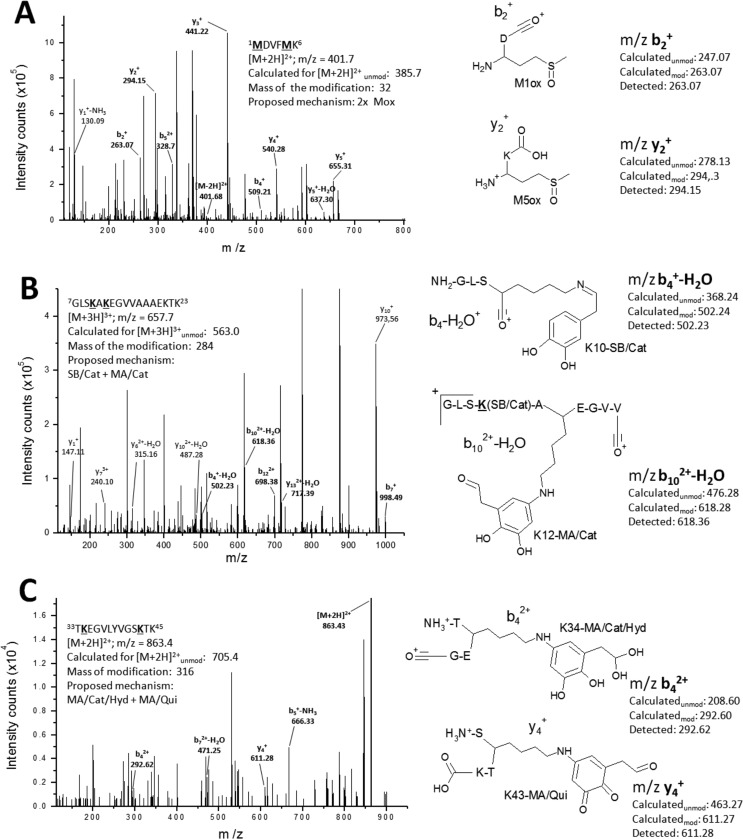

DOPAL Forms Covalent Adducts with Lysines and Promotes Oxidation of Met Residues of aS

Chemical modifications induced by DOPAL on aS monomers were investigated using MS. Because of their low oxidation potential, methionines are readily oxidized by many oxidants, producing the corresponding sulfoxide as the major product. Methionine oxidation is also a target for oxidation promoted by DA in which Met-127 seems to play an important role in the formation of oligomers (34). Incubation of aS in the presence of DOPAL leads to the oxidation of Met residues to Met-sulfoxide (Table 3), as indicated by an increased m/z = 16 in peptide fragments generated from aS-DOPAL-M. A product ion MS/MS spectrum of the peptide 1MDVFMK6 of an aS-DOPAL-M sample is shown in Fig. 7A. This peptide was detected with double-positive charge with an m/z value of 401.7 Da (unmodified control, [M + 2H]2+ detected at 385.7 Da, data not shown), which matches with the oxidation of two Met residues. Fragments b2+ and y2+ present in the MS/MS spectrum confirm that both Met-1 and Met-5 are oxidized to sulfoxide in this peptide. NMR experiments indicate that Met-5 is more susceptible to DOPAL-induced oxidation than the C-terminal methionines (Met-116 and Met-127), consistent with previous data that indicate that the C-terminal Met residues (Met-116 and Met-127) are protected by a residual structure of the disordered aS monomer (35, 36). This is corroborated by our MS analysis, which indicates the co-existence of non-oxidized and oxidized forms of Met-116 and Met-127, with variable proportions depending on the sample preparation (data not shown). In contrast, Met-1 and Met-5 were found mostly in their oxidized form.

TABLE 3.

Modified residues and mechanisms of modification of aS-DOPAL monomers detected by MS/MS

The mechanism of modification was proposed based on the results from three independent experiments. Cat, catechol; Qui, quinone; Hyd, hydrated; Mox, methionine oxidation; SB, Schiff-base; MA, Michael-adduct.

| DOPAL-modified peptide sequence | Modified residue | Mechanism of modification |

|---|---|---|

| 1MDVFMK6 | Met-1 | Mox |

| Met-5 | Mox | |

| 1MDVFMKGLSK10 | Met-1 | Mox |

| Met-5 | Mox | |

| 1MDVFMKGLSKAKEGVVAAAEK21 | Met-1 | Mox |

| Met-5 | Mox | |

| Lys-12 | MA/Cat/Hyd | |

| 7GLSKAKEGVVAAAEKTK23 | Lys-10 | SB/Cat |

| Lys-12 | MA/Qui | |

| 7GLSKAKEGVVAAAEKTKQGVAEAAGKTK34 | Lys-12 | MA/Qui/Hyd |

| Lys-21 | MA/Qui | |

| Lys-32 | SB/Cat | |

| 13EGVVAAAEKTK23 | Lys-21 | MA/Qui |

| 33TKEGVLYVGSKTK45 | Lys-34 | MA/Cat/Hyd |

| Lys-43 | MA/Qui | |

| 33TKEGVLYVGSKTK45 | Lys-34 | MA/Qui/Hyd |

| Lys-43 | MA/Qui | |

| 35EGVLYVGSKTK45 | Lys-43 | MA/Qui |

FIGURE 7.

MS/MS product-ion spectra of DOPAL-modified peptides of aS. A, [M + 2H]2+ 1MDVFMK6 (m/z 401.7 Da), in which both M1 and M5 are oxidized. B, [M + 3H]3+ 7GLSKAKEGVVAAAEKTK23 (m/z = 657.7 Da), in which Lys-10 and Lys-12 are bound to DOPAL via SB/cat and MA/cat mechanisms, respectively. C, [M + 2H]2+ 33TKEGVLYVGSKTK45 (m/z = 863.4 Da), in which Lys-34 and Lys-43 are bound to DOPAL via MA/cat/hyd and MA/quinone mechanisms, respectively (cat, catechol; qui, quinone; hyd, hydrated). Modified residues are in bold. A mass tolerance of 0.01 Da was utilized. For each panel, key fragments used to identify the location and nature of the DOPAL-induced modifications are illustrated along with their expected unmodified and modified mass and the observed mass.

In addition to the oxidation of Met residues, the mass analysis of peptides generated after trypsin digestion of aSunmod and aS-DOPAL-M indicates the formation of covalent adducts between DOPAL/DPQ and Lys residues of aS (Table 3 and Figs. 7 and 8). Notably, aS-DOPAL-M shows more missed cleavages than the aSunmod (Table 4), which is consistent with the fact that trypsin might have an impaired performance during digestion of aS-DOPAL-M because of the formation of DOPAL adducts with Lys residues.

FIGURE 8.

Chemical modifications of aS monomer produced by the incubation with DOPAL as determined by MS/MS analysis. Cat, catechol; Qui, quinone; Hyd, hydrated; Ox, oxidized.

TABLE 4.

Missed cleavages in aS and aS-DOPAL-M after digestion with trypsin

PSM indicates peptide spectrum matches.

| Sample | Σ # missed cleavages | Σ # PSM | Ratio, missed cleavages per PSM | Mode | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aSunmod | 468 | 16,021 | 0.0292 | 1 | 1.53 |

| aS-DOPAL-M | 928 | 11,282 | 0.0823 | 1 | 2.34 |

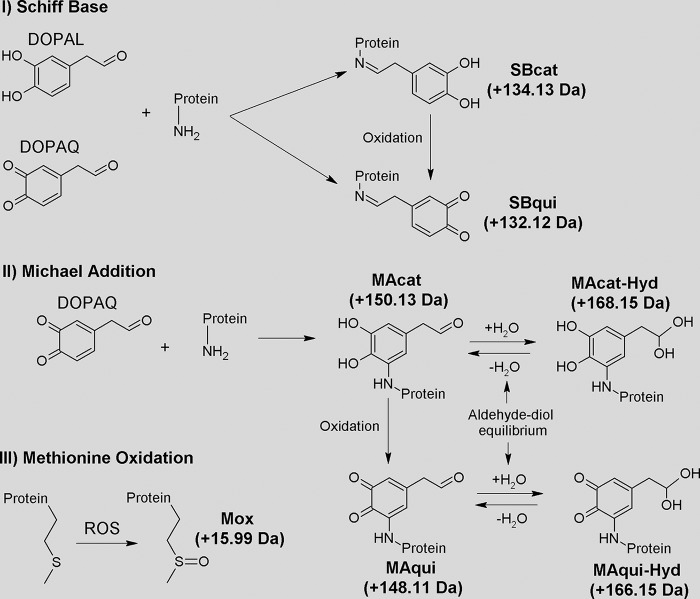

In interpreting the MS data in detail, we considered previously proposed mechanisms for protein modification by molecules structurally similar to DOPAL. Rauniyar and Prokai (37) detected the formation of SB between protein lysine residues of cytochrome c oxidase and the toxic aldehyde 4-hydroxi-2-nonenal (HNE) through the utilization of neutral loss-triggered MS3 experiments. Li et al. (38) suggest the formation of MA adducts between ortho-quinone, produced from the oxidation of catechol, and lysine residues of aS. Interestingly, such adducts were not detected in the reaction between aS and DA, which also exhibits a catechol scaffold (39). We therefore examined the data for indications that DOPAL could react with aS lysines via these two mechanisms as follows: MA involving the catechol ring or SB involving the aldehyde's carbonyl (Fig. 8).

The product ion spectrum of the peptide 7GLSKAKEGVVAAAEKTK23 (Fig. 7B) from aS-DOPAL-M sample illustrates the formation of SB adducts. This peptide was detected with triple charge and m/z value of 657.7 Da. The m/z values of the full peptide along with MS/MS fragments such as b122+ and b7+ confirm the presence of two chemical modifications localized to the two N-terminal lysines, Lys-10 and Lys-12. The formation of an SB/catechol for Lys-10 is indicated by fragment b4+-H2O. This result indicates that, despite the oxidation of DOPAL being essential for its interaction with aS, its reduced form is also able to bind to the protein via SB. In all, formation of SB adducts involving the carbonyl group of DOPAL was detected for the Lys residues Lys-10 and Lys-32 (Table 3), both in the form of catechol (+134 Da).

In addition to SB mechanism, modifications via MA on DOPAL's quinone ring were also detected for lysines in which DOPAL was found in its catechol (+150 Da) or quinone form (+148 Da). MS/MS fragments such as b4+-H2O, b7+ and b102+-H2O in Fig. 7B indicate that in addition to the SB adduct on Lys-10, Lys-12 forms an MA catechol adduct. Furthermore, we detected the formation of MA adducts containing DOPAL hydrate (+168 Da for DOPAL-catechol and +166 Da for DOPAL-quinone), which is consistent with a geminal-diol equilibrium. The MS/MS spectrum of peptide 33TKEGVLYVGSKTK45, shown in Fig. 7C, confirms the presence of MA adducts containing hydrated DOPAL. This peptide appears as a [M + 2H]2+ with an m/z value of 863.4 Da. The m/z values of the full peptide as well as fragments in the MS/MS spectrum such as b42+ and y4+ confirm the presence of an MA/catechol/hydrated modification for Lys-34, as well as a MA/quinone adduct for Lys-43. The presence of hydrated DOPAL bound to aS in a detectable amount could explain the predominance of MA adducts over SB, because the latter requires DOPAL in its aldehyde form. In all, MA modifications were detected for lysines Lys-12, Lys-21, Lys-34, and Lys-43 (Table 3). Reported SB and MA modifications were detected in three independent experiments. Modifications in additional lysines were only detected sporadically and were not taken into account.

To confirm the role of lysines in the formation of the aS-DOPAL oligomers, we used a protocol for chemical modification of Lys residues by CA. Unlike aSunmod, CA-treated aS exhibited a drastically lower content of oligomers after incubation with DOPAL (Fig. 9, A and B), which indicates that the formation of DOPAL-Lys adducts likely is a critical step for aS oligomerization mediated by DOPAL. To evaluate a potential role for Met residues in DOPAL-mediated oligomerization, we examined aS constructs aSdel 2–11 and aS1–103, missing the two N-terminal or two C-terminal Met residues, respectively. Each of these exhibited nearly the same profile of oligomerization in the presence of DOPAL as observed for WT aS (Fig. 9C). These findings point out that N-terminal methionines (Met-1 and Met-5), as well as the entire C terminus domain (103–140) are not important for the process of oligomerization induced by DOPAL. In addition, synuclein family members, β-synuclein and γ-synuclein, which present a higher sequence identity to aS at the N terminus (rich in Lys residues) than at the C terminus, also exhibited similar oligomerization profiles in the presence of DOPAL when compared with aS.

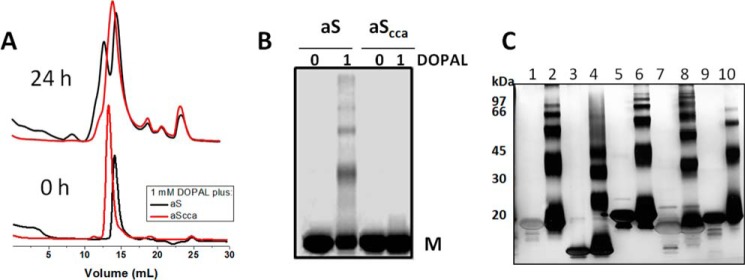

FIGURE 9.

Role of Lys residues on DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization. SEC (A) and SDS-PAGE (B) analysis of 50 μm Lys-blocked-aS (citraconic anhydride-treated aS (aScca)) and aSunmod after incubation with 1 mm DOPAL at 37 °C and agitation. C, SDS-PAGE analysis of truncated forms of aS (aS(del2–11) and aS(1–103)) and synuclein family members (β-synuclein and γ-synuclein) (protein concentration = 50 μm) after 24 h of incubation in the presence of 500 μm DOPAL, pH 7.5. Lane 1, aS(del 2–11); lane 2, aS(del 2–11) + DOPAL; lane 3, aS(1–103); lane 4, aS(1–103) + DOPAL; lane 5, β-synuclein; lane 6, β-synuclein + DOPAL; lane 7, γ-synuclein; lane 8, γ-synuclein + DOPAL; lane 9, aS; lane 10, aS + DOPAL.

Membrane Binding Protects aS against DOPAL Effects

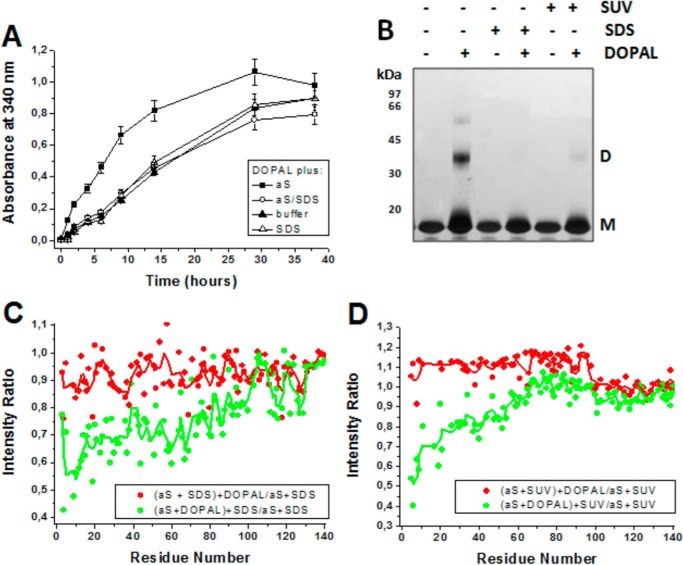

To investigate whether the effect of aS on DOPAL oxidation, observed in Fig. 6A, depends on the intrinsically disordered structure of the protein, we measured the oxidation of DOPAL in the presence of aS plus SDS micelles. Fig. 10A shows that the ability of aS to accelerate DOPAL oxidation was remarkably reduced in the presence of SDS micelles, although SDS alone had no effect on DOPAL oxidation. Next, we investigated whether helically folded aS is protected against the effects of DOPAL by comparing the effect of DOPAL on either membrane-free aS or aS in the presence of SDS micelles or SUVs. SDS-PAGE analysis clearly indicates that the binding of aS to SDS micelles or SUVs blocks DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization (Fig 10B). Fig. 10C shows the intensity ratio of signals of the 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of aS incubated in the presence of DOPAL (DOPAL/protein ratio = 10) in which the SDS micelles were added to the samples before ((aS + SDS) + DOPAL) or after ((aS + DOPAL) + SDS) incubation at 37 °C for 24 h, both normalized by the intensity for aSunmod plus SDS. The continuous line (Fig. 10C) indicates a three-residue average. When SDS is added only after the incubation, the intensity decrease of signals at the N terminus of aS plus DOPAL is similar to that observed for the free protein (Fig. 4A), which corresponds to the perturbation caused by the reaction of the protein with DOPAL. However, when SDS micelles are added to the system before the incubation with DOPAL, aS-DOPAL and aSunmod exhibited nearly identical intensities in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra, suggesting that SDS-bound aS is protected against the effects of DOPAL. Similar results were observed for aS incubated with DOPAL in the presence of 8 mm SUV (Fig. 10D) For these experiments, aS plus DOPAL was incubated at 15 °C for 72 h (no agitation), a condition in which the protein remains essentially monomeric and SUVs are fairly stable.

FIGURE 10.

Effect of membrane-bound aS on the reaction between aS and DOPAL. A, effect of SDS micelles (40 mm) on the ability of aS to accelerate DOPAL oxidation, as determined by the increase in absorbance at 340 nm. B, effect of SDS micelles or SUV on DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization monitored by SDS-PAGE. C, SDS micelle-induced protection of aS against DOPAL effects was quantified by measuring the intensity of signals of 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of 15N-aS (200 μm in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5) incubated in the presence of 1 mm DOPAL in which 40 mm SDS micelles were added at the initial time or only after the incubation at 37 °C for 24 h. The cross-peak intensities were normalized by intensity of the sample aSunmod plus SDS. D, protection promoted by the presence of 8 mm SUV against DOPAL-induced changes in aS structure during the incubation of the protein in the presence of DOPAL at 15 °C for 72 h. Spectra in the presence of SUV and SDS micelles were recorded at 10 and 25 °C, respectively. The kinetic assay in A was performed in triplicate, and the results are represented as mean ± S.D. The continuous lines in C and D indicate a three-residue average.

DOPAL-aS Adducts Strengthen the Interaction of N Terminus with NAC Domain of aS

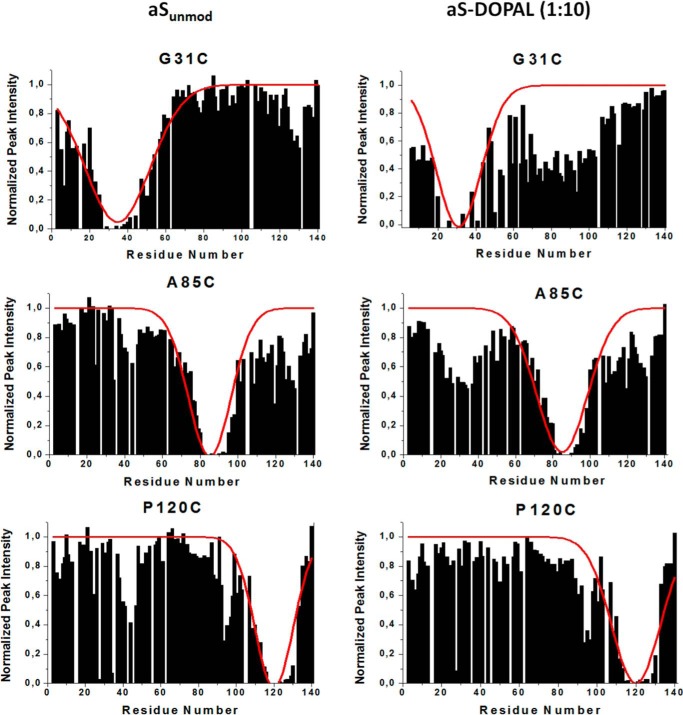

Intramolecular long range interactions between the C terminus and the N terminus of aS may influence both the aggregation of the protein and its interaction with lipid membranes. Because the formation of DOPAL-Lys adducts decreases the positive charge of the N-terminal domain of aS, we examined long range intramolecular interactions in aS-DOPAL(1:10) using PRE. PRE can establish the physical proximity of different sites within a protein through the degree of broadening observed in the NMR signals caused by the presence of a spin-labeled site (23). Here, PRE was evaluated by measuring the intensity of cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of MTSL spin-labeled aS, in the absence or presence of ascorbic acid, which was added to the MTSL spin-labeled sample to reduce the nitroxide spin label. PRE measurements for spin-labeled aSunmod mutants G31C, A85C, and P120C showed that spin labels near the N terminus, or in the NAC region (G31C and A85C), result in a broadening of residues in the C-terminal tail in the vicinity of residue 128, whereas the spin label in the C-terminal tail leads to broadening in the NAC region as well as near the N terminus of the protein (Fig. 11), as reported previously (40). However, for aS-DOPAL(1:10) monomer, the incorporation of spin-label at position 31 caused a remarkable broadening in the NAC region, which was not observed for the unmodified protein. Similarly, the presence of MTSL at aS-DOPAL position 85 caused much more extensive broadening near the N terminus of the protein than for aSunmod. In contrast, the broadening at C terminus domain caused by MTSL at position 31 was less pronounced for aS-DOPAL in comparison with the unmodified protein. Overall, these results suggest that the formation of DOPAL-aS adducts increase the interaction of the N terminus with the NAC domain but decrease long range interactions involving the N- and C-terminal regions.

FIGURE 11.

Long range interactions in aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers monitored by PRE. aS-DOPAL samples were prepared by incubation of MTSL-treated aS (in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5) in the presence of DOPAL (dopal/aS ratio = 10) for 24 h at 37 °C. Under these conditions, aS-DOPAL remains essentially monomeric (∼95%). The histograms represent the intensity of cross-peaks of the residues in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of MTSL spin-labeled and reduced protein samples. Reduction of MTSL was promoted by ascorbic acid treatment. Spectra were recorder at 10 °C. Continuous red lines indicate the broadening predicted using an idealized random coil model of the polypeptide chain (40).

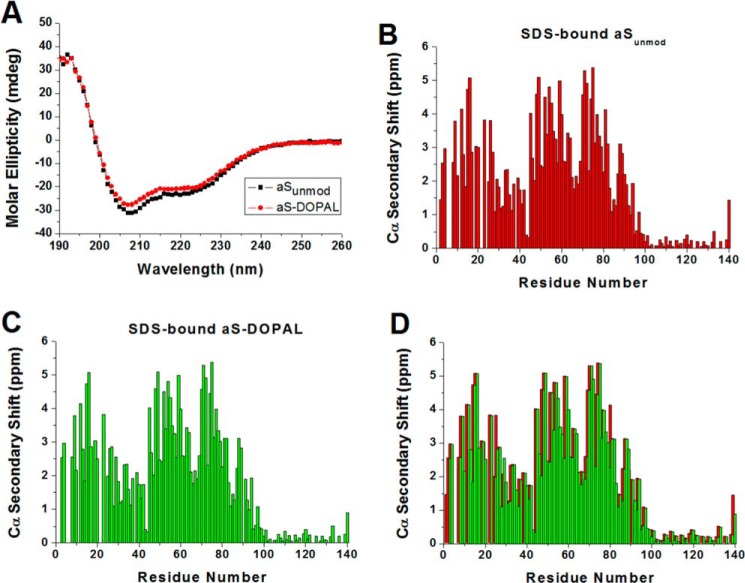

DOPAL Decreases the Affinity of aS for Synaptic Vesicle-like Membranes

The formation of DOPAL-aS adducts could affect the propensity of aS to bind to and to form helical structure upon binding to membranes, either by altering the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions that promote membrane binding or by altering the stability of α-helical backbone conformation. Fig 12A shows that the far-UV CD spectra for SDS-bound aSunmod and aS-DOPAL(1:10) samples are nearly identical, with the negative bands at 208 and 222 nm that are characteristics of α-helical conformations, suggesting that their interaction with the negatively charged headgroups and hydrophobic interior of SDS micelles is very similar. To investigate the secondary structure of SDS-bound aS-DOPAL monomer in greater detail, we measured the Cα chemical shifts, obtained from HNCA spectra, as indicators of secondary structure preferences in the protein (Fig. 12, B and C). Empirical values expected for a random coil polypeptide (41, 42) were subtracted to generate Cα secondary shifts, which provide secondary structure information. Positive Cα secondary chemical shifts indicate a preference for helical conformation, whereas residues that sample more extended conformations show the opposite pattern. Surprisingly, both samples display nearly identical values for Cα secondary chemical shifts (Fig. 12D). Therefore, the loss of positive charge due to the formation of the DOPAL-Lys adduct does not affect the helicity of the protein in the presence of SDS and does not introduce breaks in the helical structure of the protein beyond those already found in SDS-bound unmodified aS.

FIGURE 12.

Helical conformation of SDS-bound aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers. A, CD spectra of 50 μm aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers in the presence of 40 mm SDS, pH 7.5. B and C, α-carbon secondary shifts for 200 μm aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers, respectively, in the presence of 40 mm SDS, pH 7.5, determined through HNCA spectra assignment. Positive values indicate α-helix structure. aS-DOPAL samples were prepared by incubation of the protein (in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5) in the presence of DOPAL (dopal/aS ratio = 10) for 24 h at 37 °C. NMR and CD spectra were recorded at 25 °C. D, superposition of the plots displayed in B and C.

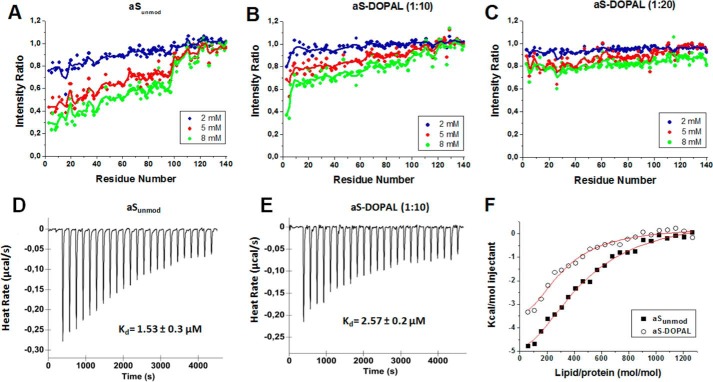

To investigate the effects of DOPAL modification on the binding of aS to lipid vesicles, we compared the HSQC spectra of aSunmod and aS-DOPAL (1:10) and (1:20) in the absence or presence of SUVs with a lipid composition similar to that found in synaptic vesicles (60% DOPC, 25% DOPE, 15% DOPS). The interaction of aS with lipid membrane occurs in the slow-exchange limit on the NMR frequency scale, and the slow rotational motion of the membrane-bound protein results in a resonance linewidth too broad for detection. Thus, the use of this approach allows us to relate the normalized signal attenuation of resonances from specific residues in the presence of SUVs to the binding of those residues to the membrane. Fig. 13, A–C, shows the intensity of cross-peaks in the 1H-15N HSQC spectra for aSunmod, aS-DOPAL (1:10), and aS-DOPAL (1:20), respectively, in the presence of varying concentrations of SUVs (2, 5, and 8 mm) normalized by the intensity in the absence of SUV. The attenuation caused by the presence of SUVs is observed primarily in the N-terminal and NAC domains of the protein. Importantly, this attenuation is higher for aSunmod in comparison with aS incubated in the presence of DOPAL, specially for aS-DOPAL(1:20), indicating that the modifications induced by DOPAL on aS lead to a decrease in the affinity of the protein for synaptic vesicle-like SUVs.

FIGURE 13.

Binding of aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers to SUVs. A–C show the intensity ratios from 1H-15N HSQC spectra of 200 μm aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers (DOPAL/aS ratio = 10 and 20) in the presence of varying concentrations of SUV to the peak intensities in the absence of lipids. The continuous line indicates a three-residue average. D and E show the ITC-measured heat release curves (baseline corrected raw data) for 25 μm aSunmod and aS-DOPAL (DOPAL/aS ratio = 10) upon titration with 100 mm SUV at 37 °C. F, integrated heat signals, with subtracted background contributions (SUV injected into buffer), for titrations of SUV into protein solutions presented in D and E. Vesicle composition: 60% DOPC, 25% DOPE, 15% DOPS. All experiments were carried out using 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, as buffer.

The interaction of the protein with SUVs may be expected to be highly dependent on temperature, particularly due to the increase of the protein hydrophobicity caused by the formation of DOPAL-Lys adducts. Thus, the parameters of binding derived from NMR experiments at 10 °C may change considerably when the temperature rises to 37 °C. For this reason, we measured the dissociation constant (Kd) at 37 °C using ITC. Fig. 13, D and E, shows the heat release curves for SUVs titrated into a calorimeter cell containing solutions of aSunmod or aS-DOPAL (1:10), respectively. The negative heat exchange upon SUV injection shows that the lipid-protein interaction is exothermic with saturable lipid-binding sites on both protein samples. After integration of the obtained heat signals, a binding curve can be derived (Fig. 13F), which provides Kd values of 1.53 ± 0.3 and 2.57 ± 0.2 μm for aSunmod and aS-DOPAL, respectively. These Kd values are somewhat higher than those reported previously based on ITC data, which indicated that the aS monomer interacts with 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine/1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylserine (4:1) vesicles with a Kd of 0.22 μm at 25 °C (62). The difference can likely be attributed to different salt concentrations (100 mm NaCl in our samples versus no salt in the previously reported experiments), although the different temperatures of the experiment (25 °C versus 37 °C) and the different compositions (headgroup and acyl chain saturation) of the vesicles used may also contribute. In any case, as observed in the NMR experiments at 10 °C, the ITC data indicate a decreased affinity of aS-DOPAL for SUVs at 37 °C.

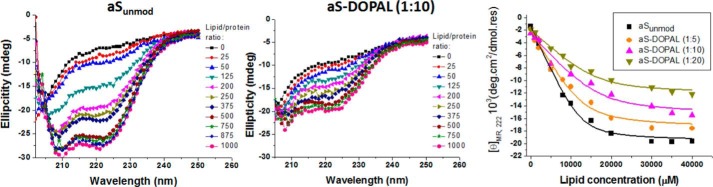

Binding to SUVs was also analyzed by measuring of the gain of helical content upon lipid titration. Far-UV CD titration curves for aS and aS-DOPAL(1:10) monomer with SUVs are shown in Fig. 14. Less helicity is induced for aS-DOPAL than for unmodified aS at equivalent SUV concentrations. Plots of ellipticity at 222 nm versus SUV concentration obtained for aS-DOPAL monomer (1:5, 1:10, and 1:20) are shifted significantly to the right compared with unmodified aS, and the degree of the rightward curve shift increases with the increase of the concentration of DOPAL, indicating that the degree of modification by DOPAL is correlated with a reduced affinity to SUVs. Fits of the titration data using Equation 2 yielded Kd values of 2.2, 4.0, 4.8, and 5.1 μm for aSunmod, aS-DOPAL(1:5), aS-DOPAL(1:10), and aS-DOPAL(1:20), respectively (Table 5), in reasonable agreement with the ITC, given the differences between the two techniques. The maximum α-helicity of the samples at saturating lipid concentration indicates that, beyond the reduced affinity for SUVs, aS-DOPAL exhibits a reduced α-helical content. Although aSunmod presents a maximum helical content of 52.6%, aS modified by DOPAL has its helical content reduced with increasing concentrations of DOPAL, yielding 46.8, 41.5, and 31.9% helicity for aS-DOPAL(1:5), aS-DOPAL(1:10), and aS-DOPAL(1:20), respectively.

FIGURE 14.

Titration of aSunmod and aS-DOPAL monomers with SUVs analyzed by far-UV CD. Protein solutions (40 μm in 20 mm sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 100 mm NaCl) were incubated at 25 °C with increasing concentrations of SUVs and analyzed by CD to determine [θ]MR, 222 (Equation 1), a measure of protein α-helicity. The data were fit to Equation 2 to calculate the values for Kd, minimum[θ]MR, 222, and maximum α-helical content. SUV composition: 60% DOPC, 25% DOPE, and 15 DOPS.

TABLE 5.

SUV affinity and maximum helicity of unmod-aS and aS treated with varying concentrations of DOPAL

| Kd | Binding stoichiometry (lipids/protein) | Ellipticity minimum | Maximum helix content | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| μm | ×103 degrees·cm2/dmol | % | ||

| Unmod-aS | 2.2 ± 0.7 | 309 ± 18 | −19.6 ± 1.3 | 52.6 ± 2.1 |

| aS-DOPAL (1:5) | 4.0 ± 1.3 | 317 ± 46 | −17.5 ± 1.8 | 46.8 ± 3.5 |

| aS-DOPAL (1:10) | 4.8 ± 2.9 | 430 ± 102 | −15.6 ± 1.1 | 41.5 ± 1.6 |

| aS-DOPAL (1:20) | 5.1 ± 1.2 | 409 ± 52 | −12.1 ± 0.9 | 31.9 ± 1.0 |

Discussion

The basis for the selective degeneration of dopamine-producing neurons in Parkinson disease remains a critical unresolved issue in Parkinson disease research. Here, we investigate the link between the most toxic by-product of dopamine production, DOPAL, and the Parkinson disease protein α-synuclein. Levels of DOPAL are found to be augmented in the post-mortem brains of patients with PD (43), potentially associated with different mechanisms as follows: (i) An increase in DA levels in the cytosol due to leakage of vesicles is possibly promoted by aS oligomers (44). DA accumulation would lead to increased MAO activity and hence to elevated DOPAL levels. (ii) An increase in MAO activity is shown with aging. Positron emission tomography experiments indicate a slight increase in MAO-B levels with age in neuronal tissue in normal healthy human subjects, which could result in elevated DOPAL levels due to MAO-catalyzed DA degradation (45). (iii) A reduction of ALDH cytosolic isoform (ALDH-1A1) expression in surviving neurons in SN of PD, as observed in post-mortem studies (12). The inhibition of mitochondrial complex I, which synthesizes NAD, a cofactor for ALDH, also results in elevated DOPAL concentration and the death of dopaminergic neurons in vitro and in vivo (11, 46). Importantly, PD patients have a deficit in mitochondrial complex I (8). Given that aS is perhaps the single most critical player in the etiology of Parkinson disease, links between DOPAL and synuclein aggregation or function may be key to understanding the basis for selective dopaminergic cell death in this disease.

DOPAL/DPQ Modify Lysine Residues in aS

Although various reports have indicated the formation of covalent adducts between dopamine or dopamine oxidation products and aS (47, 48), the precise nature of such modifications and the sites on aS where they occur have remained unclear. We developed a protocol for modifying aS with purified DOPAL and have shown that this modification leads to the formation of small aS oligomers in a manner that depends on DOPAL oxidation to DPQ. Intriguingly, DOPAL-modified aS monomers and oligomers are resistant to co-aggregation with, and also inhibit fibril formation by, unmodified aS. Given that oligomeric species are currently considered to be the most likely cause of aS-mediated toxicity in PD, the stabilization of such species by DOPAL modification of aS may represent a convergent mechanism for the toxicities associated with both aS and dopamine metabolism.

To identify specific sites at which aS is modified after incubation with DOPAL, we employed MS analysis of monomeric aS-DOPAL adducts. The data reveal that in addition to methionine oxidation, which has been previously reported to occur for aS under various oxidizing conditions, the presence of DOPAL leads to the following two types of modifications of the amino group of lysine side chains: SB formation via the carbonyl group of DOPAL or DPQ, or MA to the quinone ring of DPQ. The specificity of DOPAL modification to lysine side chains is supported by data showing that pretreatment with a lysine-blocking reagent prevents DOPAL-induced modification and oligomerization of aS. Lysines in the N-terminal domain of aS were more sensitive to adduct formation than those in the NAC or C-terminal regions of the protein. To our knowledge, this is the first report conclusively documenting the selective covalent modification of aS lysine side chains by dopamine metabolism by-products.

DOPAL May Act as an aS Cross-linker under Oxidative Conditions

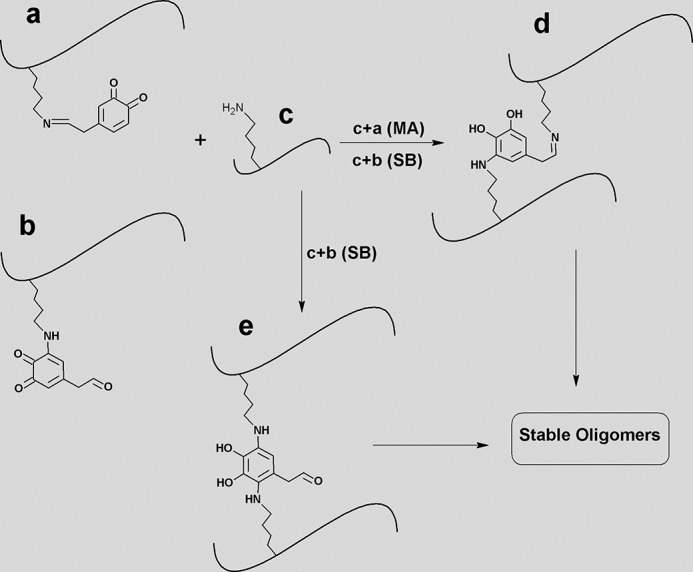

The reaction of aS with the toxic aldehydes 4-oxo-2-nonenal and HNE, generated from lipid peroxidation, results in the formation of very stable and cytotoxic protein adducts in vitro. HNE has also been found to induce oligomerization of aS and cause toxicity to dopaminergic neurons in vitro (49). Similar to 4-oxo-2-nonenal and HNE, DOPAL can form covalent adducts with aS via MA and SB reactions (50), which target Lys residues. Taking into account the formation of DOPAL-Lys adducts observed by MS and the role of Lys in the process of oligomerization triggered by DOPAL, we hypothesize a mechanism for DOPAL-induced aS oligomerization (Fig. 15). The aS-DOPAL adducts generated via an SB reaction between aS and DOPAL/DPQ could react with Lys residues of an additional aSunmod molecule via an MA mechanism, generating SB/MA cross-linked dimers of aS. Alternatively, aS-DOPAL adducts generated via MA reaction can react with Lys residues of an additional aSunmod via either SB or MA mechanisms to form MA/SB or MA/MA cross-linked dimers. Although we were unable to attempt to directly detect cross-linked peptides, due to both the limited tryptic proteolysis of these oligomers and the complexity of the analysis of the data obtained by MS, a role for protein cross-linking in DOPAL-mediated oligomer formation is supported by some of our results, including the low molecular mass of aS-DOPAL oligomers (mostly dimers and trimers), which could be attributed to steric hindrance in the formation of intra/inter-polypeptide cross-links, the high stability of these oligomers against SDS and urea denaturation and the known reaction chemistry between quinones and alkylamines such as Lys residues (e.g. via MA reactions). Moreover, the formation of protein cross-links was also observed for natural and synthetic DOPA-containing polypeptides (51, 52).

FIGURE 15.

Hypothetic mechanism of DOPAL-induced oligomerization of aS mediated by the formation of Schiff-base (SB) and Michael addition (MA) reactions. aS-DOPAL monomer (generated via SB reaction between aS and DOPAL) (a) might react with aSunmod (c) via MA mechanism, generating cross-linked dimers of aS (d). Alternatively, c can also react with aS-DOPAL monomer generated by MA reaction between aS and DOPAL (b) to form dimers via either SB or MA mechanisms. The former leads to the formation of d, and the second generates e.

DOPAL May Interfere with aS Function by Reducing Its Affinity for Membranes and Decreasing Its Propensity for Helical Structure

Our results demonstrate that the modification of aS monomer by DOPAL significantly reduces both the affinity of the protein for SUVs and the formation of helical conformations by aS upon membrane binding. DOPAL-induced impairment of binding of aS to lipid vesicles might be caused by a combination of several effects. First, we observe a large increase in intramolecular interactions between the N terminus and the NAC domain, likely caused by the reduced charge and increased hydrophobicity that results from the modification of Lys residues by DOPAL/DPQ. These increased intramolecular interactions could hinder both the initial interactions of aS with membranes and the conversion of the protein to the extended highly helical conformation associated with membrane binding (53). Second, the reduction of positive charge in the N-terminal domain of aS upon DOPAL modification would decrease the electrostatic interaction between the normally highly positively charged N-terminal domain and the negatively charged lipid headgroups present both in the SUVs used in our experiments as well as in the synaptic vesicles they are intended to represent. Finally, the formation of helical structure by aS upon membrane binding depends on the amphipathic nature of the resulting helices, including the presence of the positively charged Lys residues at the interface between the polar and apolar faces (22, 54). By converting these positively charged lysines to hydrophobic lysine adducts, the amphipathic character of the helical conformations formed by aS would be altered, potentially decreasing the ability of the protein to adopt helical structure upon membrane binding. How these different factors combine to perturb the affinity of aS for lipid membranes remains to be investigated. It is interesting to note, however, that binding of aS to SDS micelles appears to be unaffected by DOPAL, suggesting that the strong nature of this interaction, or perhaps the different broken-helix conformation adopted by the protein in the micelle-bound state (53, 55), mitigates the effects of DOPAL modification both on binding and on the formation of helical structure.

Potential Role of DOPAL in aS Function and Pathology

The physiological functions of aS remain poorly understood (56), but at presynaptic nerve terminals the protein is thought to have some role in the genesis, trafficking, or fusion of synaptic vesicles. It has been proposed that aS may function as a SNARE chaperone and promote SNARE-complex assembly (57), but aS also reportedly can inhibit SNARE-mediated vesicle fusion. Recently, it has also been proposed that aS may play a role in protecting membrane lipids from oxidative damage by coupling oxidation of its N-terminal membrane-bound methionines to reduction of oxidized lipids, leading to its release from the membrane and subsequent reduction by cytosolic methionine sulfoxide reductases (58). All of these putative functions require the protein to bind membranes (likely in the form of synaptic vesicles) via its N-terminal lipid-binding domain, which contains a series of seven imperfect 11-residue repeats centered on a KTKEGV consensus sequence. This domain adopts an amphipathic helical structure upon binding to detergent micelles or phospholipid vesicles, and Lys residues within the N-terminal repeats play an important role in the interaction of the protein with membranes (54) and may also regulate its pathophysiology (59). Importantly, 11 of 15 lysines found in aS are located in this N-terminal domain, which is the primary target of DOPAL.

Because DOPAL weakens the affinity of aS monomers for membrane vesicles, it is likely that DOPAL modification of aS in vivo would alter or compromise the function of the protein. To the extent that alterations in aS function contribute to the etiology of PD, this aspect of DOPAL's effects on aS could be important. It is also possible that by releasing aS from membrane surfaces, DOPAL may enhance the concentration of soluble monomeric aS and thereby drive aggregation of the soluble form of the protein. At the same time, release of aS from the membrane surface enhances its susceptibility to DOPAL/DPQ-mediated cross-linking of aS into small oligomers. These oligomers may potentially be toxic themselves, but in addition they, as well as monomeric aS-DOPAL, can retard the formation of mature fibrils by unmodified aS, likely increasing the population of other potentially toxic oligomeric species as well. It is also interesting to note that a number of disease-linked aS mutations, including A30P and G51D, are now known to promote release of aS from membranes (60, 61). Such mutations could thereby facilitate the modification of aS by DOPAL and promote the toxic effects of this interaction.

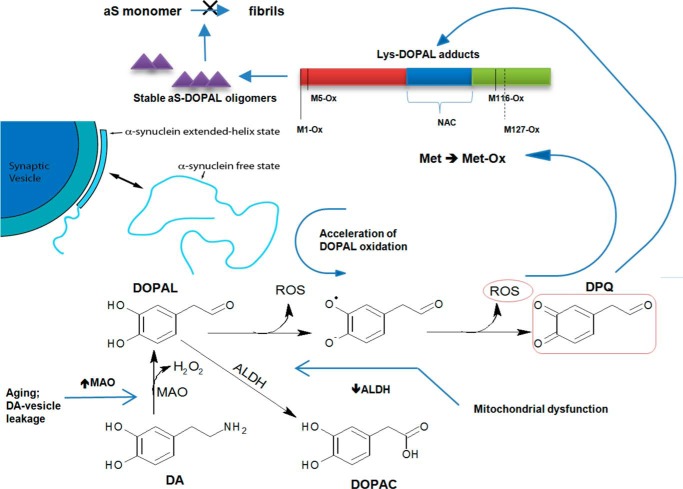

Conclusions

Our findings lead to the following model for selective dopaminergic neuron degeneration in PD based on the relationship between DA metabolism, oxidative stress, and aS aggregation (Fig. 16). Cytosolic disordered forms of aS can stimulate DOPAL oxidation, whereas binding of aS to lipid membranes may prevent, at least in part, aS-induced DOPAL oxidation. Oxidation of DOPAL leads both to the production of ROS, resulting in aS Met oxidation, as well as to the formation of covalent adducts between DOPAL and aS Lys side chains. DOPAL-modified aS forms potentially toxic small oligomers via a mechanism that remains to be fully elucidated but that likely involves the formation of DOPAL-mediated protein cross-links. These highly stable aS-DOPAL oligomers, as well as DOPAL-modified monomers, act as potent inhibitors of the formation of putatively inert or even neuroprotective mature aS fibrils, increasing the population of other potentially toxic oligomers of unmodified aS. Both Met oxidation and DOPAL modification of aS also act to reduce the affinity of the protein for synaptic-like vesicles and its ability to form helical structure, increasing the population of membrane-free aS and facilitating further DOPAL-mediated oxidation and oligomerization. Ultimately, further studies are necessary to determine the neurotoxic activity of DOPAL-induced aS oligomers and to ascertain whether these contribute directly to dopaminergic cell death and/or whether their additional effects, including potential inhibition of membrane-binding-dependent aS functions and enhancing the buildup of unmodified non-fibrillar oligomers of aS, contribute to the pathogenesis of PD.

FIGURE 16.

Model for selective dopaminergic neuron degeneration based on the linkage between DA metabolism, oxidative stress, and aS aggregation. In PD, MAO activity is augmented, which would contribute to the conversion of DA to DOPAL. An excess of DOPAL would not be converted efficiently to 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid due to the deficiency in ALDH activity. In this scenario, a cascade of events associated with the “dangerous” encounter between DOPAL and aS will occur. Unfolded aS accelerates DOPAL oxidation, increasing the level of DPQ. In addition to the methionine oxidation, aS seems to interact with DOPAL via formation of adducts with Lys residues. The highly stable aS-DOPAL oligomers can act as potent inhibitors of aS fibrillation and have reduced affinity for SUVs.

Author Contributions

C. F. and E. C. C. contributed equally to this work. C. F. and E. C. C. conducted most of the experiments and analyzed the results. C. F. conceived the idea for the project. C. F. and D. E. supervised the project, analyzed the results, and wrote the paper. D. Y. Y. F. conducted the experiments for determination of hydrogen peroxide. A. S. P. contributed to the NMR experiments. G. D. T. A. and G. B. D. conducted the MS experiments and analyzed the results.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Trudy Fiona Ramlall for help with protein production and Dr. Shifeng Xiao, Dr. Guohua Lv, and Dr. Clay Bracken for help with NMR experiments.

This work was supported by Fundação Carlos Chagas Filho de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado do Rio de Janeiro (FAPERJ), Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), and National Institutes of Health Grant R37AG019391 (to D. E.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- PD

- Parkinson disease

- ALDH

- aldehyde dehydrogenase

- CA

- citraconic anhydride

- DA

- dopamine

- DOPAL

- 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde

- DOPC

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine

- DOPE

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine

- DOPS

- 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-l-serine

- DPQ

- DOPAL oxidation products include DOPAL-quinone

- HNE

- 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal

- HSQC

- heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- MA

- Michael addition

- MTSL

- 1-oxyl-2,2,5,5,-tetramethylpyrroline-3-methylmethanethiosulfonate

- PRE

- paramagnetic relaxation enhancement

- SB

- Schiff-base

- SEC

- size exclusion chromatography

- SN

- substantia nigra

- SNARE

- soluble N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor attachment protein receptor

- SOD

- superoxide dismutase

- SUV

- small unilamellar vesicle

- ThT

- thioflavin-T

- aS

- α-synuclein

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- MAO

- monoamine oxidase

- ROS

- reactive oxygen species

- HNCA

- proton-nitrogen-α-carbon correlation

- NAC

- non-Aβ component.

References

- 1.Langston J. W. (2006) The Parkinson's complex: parkinsonism is just the tip of the iceberg. Ann. Neurol. 59, 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langston J. W., Ballard P., Tetrud J. W., and Irwin I. (1983) Chronic parkinsonism in humans due to a product of meperidine-analog synthesis. Science 219, 979–980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sulzer D. (2007) Multiple hit hypotheses for dopamine neuron loss in Parkinson's disease. Trends Neurosci. 30, 244–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillantini M. G., Schmidt M. L., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q., Jakes R., and Goedert M. (1997) α-Synuclein in Lewy bodies. Nature 388, 839–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spillantini M. G., Crowther R. A., Jakes R., Hasegawa M., and Goedert M. (1998) α-Synuclein in filamentous inclusions of Lewy bodies from Parkinson's disease and dementia with Lewy bodies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 6469–6473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Polymeropoulos M. H., Lavedan C., Leroy E., Ide S. E., Dehejia A., Dutra A., Pike B., Root H., Rubenstein J., Boyer R., Stenroos E. S., Chandrasekharappa S., Athanassiadou A., Papapetropoulos T., Johnson W. G., et al. (1997) Mutation in the α-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson's disease. Science 276, 2045–2047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu J., Kao S. Y., Lee F. J., Song W., Jin L. W., Yankner B. A. (2002) Dopamine-dependent neurotoxicity of α-synuclein: a mechanism for selective neurodegeneration in Parkinson disease. Nat. Med. 8, 600–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hasegawa T., Matsuzaki-Kobayashi M., Takeda A., Sugeno N., Kikuchi A., Furukawa K., Perry G., Smith M. A., and Itoyama Y. (2006) α-Synuclein facilitates the toxicity of oxidized catechol metabolites: implications for selective neurodegeneration in Parkinson's disease. FEBS Lett. 580, 2147–2152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Filloux F., and Townsend J. J. (1993) Pre- and postsynaptic neurotoxic effects of dopamine demonstrated by intrastriatal injection. Exp. Neurol. 119, 79–88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Follmer C. (2014) Monoamine oxidase and α-synuclein as targets in Parkinson's disease therapy. Exp. Rev. Neurother. 14, 703–716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burke W. J., Li S. W., Williams E. A., Nonneman R., and Zahm D. S. (2003) 3,4-Dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde is the toxic dopamine metabolite in vivo: implications for Parkinson's disease pathogenesis. Brain Res. 989, 205–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldstein D. S., Sullivan P., Holmes C., Kopin I. J., Basile M. J., and Mash D. C. (2011) Catechols in post-mortem brain of patients with Parkinson disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 18, 703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldstein D. S., Sullivan P., Holmes C., Miller G. W., Alter S., Strong R., Mash D. C., Kopin I. J., and Sharabi Y. (2013) Determinants of buildup of the toxic dopamine metabolite DOPAL in Parkinson's disease. J. Neurochem. 126, 591–603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fitzmaurice A. G., Rhodes S. L., Lulla A., Murphy N. P., Lam H. A., O'Donnell K. C., Barnhill L., Casida J. E., Cockburn M., Sagasti A., Stahl M. C., Maidment N. T., Ritz B., and Bronstein J. M. (2013) Aldehyde dehydrogenase inhibition as a pathogenic mechanism in Parkinson disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 636–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Burke W. J., Kumar V. B., Pandey N., Panneton W. M., Gan Q., Franko M. W., O'Dell M., Li S. W., Pan Y., Chung H. D., and Galvin J. E. (2008) Aggregation of α-synuclein by DOPAL, the monoamine oxidase metabolite of dopamine. Acta Neuropathol. 115, 193–203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coelho-Cerqueira E., Carmo-Gonçalves P., Pinheiro A. S., Cortines J., and Follmer C. (2013) α-Synuclein as an intrinsically disordered monomer–fact or artefact? FEBS J. 280, 4915–4927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anderson D. G., Mariappan S. V., Buettner G. R., and Doorn J. A. (2011) Oxidation of 3,4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde, a toxic dopaminergic metabolite, to a semiquinone radical and an ortho-quinone. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 26978–26986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Abramoff M. D., Magalhaes P. J., and Ram S. J. (2004) Image processing with ImageJ. Biophot. Int. 11, 36–42 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Delaglio F., Grzesiek S., Vuister G. W., Zhu G., Pfeifer J., and Bax A. (1995) NMRPipe: a multidimensional spectral processing system based on UNIX pipes. J. Biomol. NMR 6, 277–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bermel W., Bertini I., Felli I. C., Lee Y. M., Luchinat C., and Pierattelli R. (2006) Protonless NMR experiments for sequence-specific assignment of backbone nuclei in unfolded proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 3918–3919 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandra S., Chen X., Rizo J., Jahn R., and Südhof T. (2003) A broken α-helix in folded α-synuclein. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 15313–15318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eliezer D., Kutluay E., Bussell R. Jr., and Browne G. (2001) Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 307, 1061–1073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eliezer D. (2012) Distance information for disordered proteins from NMR and ESR measurements using paramagnetic spin labels. Methods Mol. Biol. 895, 127–138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]