Background: The formation of juxtanuclear aggresomes from aggregation-prone proteins is widely believed to be protective to cells.

Results: Cell lines containing aggresomes suffer from DNA double-strand breaks, cell cycle arrest, mitotic defects, and apoptosis.

Conclusion: Long term accumulation of aggresomes has detrimental effects on nuclear function in cells.

Significance: This study provides the first evidence that aggresomes can cause significant cellular dysfunction in dividing cells.

Keywords: aggresome, apoptosis, DNA damage, Huntington disease, p53, polyglutamine, protein aggregation, cell cycle arrest, mitotic defects

Abstract

Juxtanuclear aggresomes form in cells when levels of aggregation-prone proteins exceed the capacity of the proteasome to degrade them. It is widely believed that aggresomes have a protective function, sequestering potentially damaging aggregates until these can be removed by autophagy. However, most in-cell studies have been carried out over a few days at most, and there is little information on the long term effects of aggresomes. To examine these long term effects, we created inducible, single-copy cell lines that expressed aggregation-prone polyglutamine proteins over several months. We present evidence that, as perinuclear aggresomes accumulate, they are associated with abnormal nuclear morphology and DNA double-strand breaks, resulting in cell cycle arrest via the phosphorylated p53 (Ser-15)-dependent pathway. Further analysis reveals that aggresomes can have a detrimental effect on mitosis by steric interference with chromosome alignment, centrosome positioning, and spindle formation. The incidence of apoptosis also increased in aggresome-containing cells. These severe defects developed gradually after juxtanuclear aggresome formation and were not associated with small cytoplasmic aggregates alone. Thus, our findings demonstrate that, in dividing cells, aggresomes are detrimental over the long term, rather than protective. This suggests a novel mechanism for polyglutamine-associated developmental and cell biological abnormalities, particularly those with early onset and non-neuronal pathologies.

Introduction

Expression of misfolded proteins frequently leads to the formation of intracellular aggregates either in the cytoplasm or the nucleus (1). Aggregate formation is associated with oxidative stress in mitochondria (2) and a breakdown in protein homeostasis or proteostasis through chaperone defects (3) and impairment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS)2 (4). When proteostasis is compromised to the extent that the number of abnormally folded proteins exceeds the capacity of the UPS and autophagy systems to degrade them (5–7), a large juxtanuclear aggregate known as the aggresome (7, 8) forms by microtubule-dependent deposition of smaller aggregates close to the centrosome (i.e. the microtubule-organizing center; MTOC). Aggresomes are later degraded by autophagy (9–11), which is possibly stimulated by the UPS (11, 12).

Further research has revealed that the ubiquitination of substrates within aggregates is a prerequisite for aggregate recognition and transport to aggresomes. This is initially mediated by HDAC6, which binds both the polyubiquitin chains of protein substrates and the microtubule (MT) motor protein dynein, thereby promoting the transport of polyubiquitinated aggregates along MTs toward the MTOC (13). A number of other factors have been associated with aggresome formation, such as CDC48 and its cofactors, 14-3-3, UFD1, and NLP4 (14).

Although there is still debate on the issue, it is widely believed that because aggresomes sequester potentially toxic misfolded proteins such as polyglutamine (polyQ), they are protective for cells (9, 14–16) and even serve as a cytoplasmic recruitment center to facilitate the degradation of misfolded proteins (8, 9, 14). In contrast, some research has suggested that aggresomes cause or exacerbate cell pathology. For example, the deposition of an aggresome results in indentations in, and disruption of, the nuclear envelope (6–8, 17). One factor contributing to this discrepancy may be that most studies on the effects of aggresomes in cell models rely on short term experiments carried out over only a few days. These studies are unlikely to uncover long term effects, such as an impact on mitosis. To address this, we have produced stable cell lines that express polyQ proteins from inducible, single-copy genes and examined the effects of expression over a period of up to 3 months. We provide the first evidence that long term accumulation of juxtanuclear aggresomes results in nuclear malformation, DSBs, and interference with the mitotic spindle apparatus, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. Thus, although in the short term aggresome formation may be beneficial, the longer term persistence of such a large juxtanuclear structure has detrimental effects on cells.

Experimental Procedures

Materials

l-Glutamine, zeocin, hygromycin, blasticidin, DMEM, PBS, FBS, hydroxyurea, etoposide, carbenicillin solution, and agarose were purchased from Sigma. The Flp-In T-REx293 cell line and plasmid pcDNA5/FRT/TO were purchased from Life Technologies, whereas GeneJammer transfection reagent was purchased from Agilent Technologies. DreamTaq was purchased from Fermentas UK. The Spin Mini Prep kit, QIA Quick Gel Extraction kit, and DNeasy Blood and Tissue kit were purchased from Qiagen. The Phusion High Fidelity PCR kit and restriction enzymes were purchased from New England BioLabs. Antibodies against polyQ (MAB1574) (dilution for immunoblotting 1:2000), γ-H2AX (05–636) (dilution for immunofluorescence 1:300; for immunoblotting 1:2000), and GAPDH (AB2302) (dilution for immunoblotting 1:2000) were from Millipore. Antibodies against P-p53 (Ser-15) (9284) (dilution for immunoblotting 1:2000) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibodies p53 (P8999) (dilution for immunoblotting 1:2000) and p21 (P1484) (1:2000) were from Sigma.

Cells

Mammalian Flp-In T-REx293 cells were grown in T75 or T25 flasks or 6-well plates by incubation at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Complete medium for normal cell growth consists of 90% DMEM, 10% FBS with 2 mm l-glutamine; antibiotics were used as appropriate. Cells were kept in logarithmic phase growth and passaged on reaching 80–90% confluence (approximately every 3–4 days). Medium was changed every 2 or 3 days. Routine cell counting and viability assays were carried out using a hemocytometer and trypan blue. Transfections were performed on cells at 80% confluency. A mixture of 97 μl of serum-free, antibiotic-free DMEM and 3 μl of GeneJammer reagent was incubated at room temperature for 5 min, after which 1 μg of plasmid was added, and the mixture incubated for a further 45 min at room temperature. The GeneJammer/DMEM mixture was added dropwise to each plate, and cells were incubated for 3 h at 37 °C in the incubator before an additional 1 ml of complete medium containing the appropriate selection antibiotics was added. Stable cell line construction has been described previously (19). Histone 2B-DsRed and pericentrin-mCherry plasmids were gifts from Dr. Viji Draviam, Cambridge (61). Positive controls for p53, P-p53 (Ser-15), p21, and cleaved caspase-3 experiments were treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm in complete medium) for 8 h. Positive controls for γ-H2AX were treated with etoposide (25 μm in complete medium) for 8 h. After treatment, samples were washed 3 times with PBS and added with complete medium for further treatment.

Immunoblotting

Cell pellets were lysed on ice in radioimmune precipitation lysis and extraction buffer (89900, Thermo Scientific) for 30 min in the presence of protease inhibitors (Roche Applied Science). Blots were probed with anti-mouse (NA931V, GE Healthcare) or anti-rabbit IgG (NA934V, GE Healthcare) and visualized using Clarity Western ECL substrate (170-5060, Bio-Rad). A G:BOX ChemiXT4 (Syngene, UK) was used for immunoblot imaging. Auto-exposure was selected for imaging to avoid saturation. The relative level of target proteins was quantified by normalizing the intensity of the image against that of GAPDH.

Immunofluorescence and Microscopy

After induction for various times, SNAP-HDQ72-expressing cells were labeled for 30 min in 37 °C and 5% CO2 atmosphere with 300 mm SNAP-Cell TMR-Star (New England Biolabs) dissolved in complete medium. After labeling, samples were washed 3 times with complete medium and incubated for 30 min before imaging. For β-tubulin labeling, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.5% Tween, and stained with a monoclonal anti-β-tubulin mouse antibody (Sigma T5168) at room temperature. After rinsing three times with PBS, samples were incubated with Alexa 568 donkey anti-mouse IgG (Life Technologies A-10037). For DNA labeling, samples were stained with Hoechst 33342 (Sigma BG2261) diluted 1:2500 in PBS solution for 1 h. Samples were mounted with VETASHEILD Mounting Medium (H-1000, Vector Laboratories Inc.). The whole process was carried out in room temperature, and the sample slices were stored at 4 °C.

For the fixed samples cells were imaged on a confocal microscope (Leica TCS SP5, using the Leica Application Suite (LAS AF)) with a HCX PL APO 40×/1.25–0.75 oil objective lens (Leica) or HCX PL APO 63×/1.40–0.60 oil objective lens (Leica) at room temperature. Fluorochromes were chosen according to each of the experiments, as described in the individual figure legends. To visualize mitosis cells were grown in glass-bottom Petri dishes at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. On the day of imaging, Petri dishes were first stabilized in the incubation chamber of the Leica TCS SP5 system with continuous air supply (37 °C and 5% CO2). Complete medium was used for cells subjected to live-cell imaging, and half of the medium was replaced every 2 days. The time interval between the capture of two images varied from 5 to 15 min as appropriate. The entire set-up was performed using LAS AF software, and ImageJ was used for image processing and analysis.

Phenotype Quantification

Approximately 200 or 600 EGFP-or SNAP-positive cells were assessed per population per experiment, as described in the individual figure legends. Mitotic cells were defined as described in the individual figure legends. Three independent experiments were performed, with the scorer blind to treatment, on different days.

Statistical Analysis

Densitometry was done on the immunoblots using ImageJ 1.47V software. Significance was determined by binary logistic regression using IBM SPSS Statistics 20 software. The y axis values are shown as a percentage (%). ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. Bar charts were produced from Prism6 software.

Results

Long Term Accumulation of Aggresomes Increases the Incidence of Abnormal Nuclear Morphology

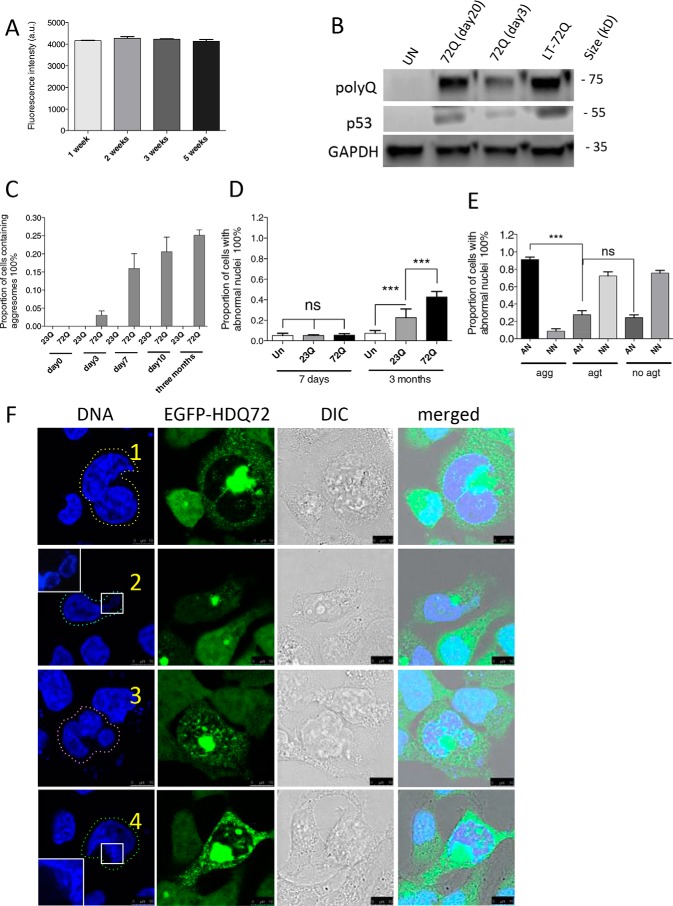

Previous work has shown that aggresomes can have a detrimental effect on nuclear morphology (7, 8, 18, 19). To investigate this phenomenon with EGFP-polyQ proteins, we established stable cell lines expressing inducible, single copy constructs of either EGFP-HDQ72 or EGFP-HDQ23 in a Flp-In T-REx293 cell background; the former protein is highly prone to aggregation, whereas the latter should not form aggregates and acts as a control. Both cell lines are constructed with the same promoter, and their respective genes are expressed at comparable levels (19). Using EGFP-HDQ72-expressing cells as an example, we verified the consistency of gene expression by flow cytometry over a 5-week period (Fig. 1A) and by immunoblotting over a 10-week period (Fig. 1B). After gene induction, juxtanuclear aggresomes gradually accumulated in the EGFP-HDQ72 cell line (but not in EGFP-HDQ23 cells) such that 16% of cells contained aggresomes 7 days after induction of the expression; this proportion increased further to 25% over a period of 3 months and stabilized at that level (Fig. 1C). Lagging behind aggresome formation was the appearance of cells in the population with abnormal nuclei: very few such cells were apparent after 7 days of polyQ gene expression, but 40% of cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 for 3 months showed aberrant nuclear morphology (Fig. 1D). In contrast, only 20% of EGFP-HDQ23 cells were affected, a significantly lower proportion (Fig. 1D). In the EGFP-HDQ72 cell line, there is a strong correlation of abnormal nuclear morphology with the presence of aggresomes, as >90% of such cells contain malformed nuclei (Fig. 1E), whereas cells without aggresomes, which include cells with only cytoplasmic aggregates and cells with neither aggresomes nor cytoplasmic aggregates, have fewer abnormal than normal nuclei. Nuclei in EGFP-HDQ72 cells may be abnormal in several different ways; they may be partially fragmented or deformed or may contain multiple nuclei within a single cell (Fig. 1F). Nevertheless, despite the nuclear abnormalities, the majority of these cells are intact, and only a few cells have the highly fragmented nuclei typical of apoptosis. Thus, although long term accumulation of EGFP-HDQ72 aggresomes is almost invariably associated with abnormal nuclei, these abnormalities are not due to apoptosis in the vast majority of cases. The degree to which apoptosis is activated by the presence of abnormal nuclei will be described below.

FIGURE 1.

Long term accumulation of aggresomes leads to abnormal nuclear morphology. A, cells expressed EGFP-HDQ72 consistently during long term expression as determined by flow cytometry, in which 10,000 cells were measured per independent cell population. The chart represents mean fluorescence ± S.D. of three independent cell populations. a.u., arbitrary units. B, immunoblotting of EGFP-HDQ72. Cells expressed EGFP-HDQ72 at the same level between day 20 and day 90 (long term). Un, uninduced cells. C, accumulation of juxtanuclear aggresomes in cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 protein over a 3-month period. Cells expressing EGFP-HDQ23 did not form aggresomes. Four independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per population per experiment (average of 4 sets of data: day 0, 0; day 3, 7 cells of 208 assessed; day 7, 34/213; day 10, 45/217; 3 months, 52/206). D, proportion of cells either induced (expressing EGFP-HDQ72 or EGFP-HDQ23 protein) or uninduced (negative control of the effects of protein expression) with abnormal nuclei at 7 days and 3 months. Three independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per population per experiment. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. E, for cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 for 3 months, >90% of cells containing aggresomes have abnormal nuclei. EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes have a similar proportion of abnormal nuclei as EGFP-HDQ23 cells. AN, abnormal nuclei; NN, normal nuclei; agg, aggresomes present; agt, cytosolic aggregates present (excluding aggresomes); no agt, neither aggresomes nor aggregates. Three independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per population per experiment (average of three sets of data: AN (agg): 48/51 (of 51 aggresome-containing cells, 48 have abnormal nuclei); NN (agg): 3/51; AN (agt): 3/13; NN (agt): 10/13; AN (no agt): 41/149; NN (no agt): 108/149). The chart represents mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001. F, confocal microscopy of abnormal nuclei in long term (3 months)-induced cells with aggresomes. Representative images of abnormal nuclei: 1, double nucleus (yellow dashed line, top row) (34/213: observed in 34 of 213 cells assessed); 2, fragmented nucleus (cyan dashed line, second row) (58/213); 3, compound abnormality (pink dashed line, third row) (29/213); and 4, damaged nucleus (green dashed line, fourth row) (119/213). As some abnormal nuclei have more than one type of abnormality, the sum of cells from all categories is larger than the total number of cells counted. Scale bars, 10 μm. G, wide-field microscopy showing that both soluble cytoplasmic EGFP-HDQ72 and insoluble aggresomes are gradually degraded after EGFP-HDQ72 expression is turned off. Long term (3 months)-induced cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 represent samples before gene-switch-off (0 days), after which the medium was replaced with medium without inducer for 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 days. Scale bar: 50 μm. H, proportion of cells with aggregates (both cytoplasmic aggregates and aggresomes) after expression of EGFP-HDQ72 was turned off. Long term induced cells were counted at different time points (2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 days) after the medium was replaced with medium without inducer. Three independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per experiment. To limit the dilution effect of population growth, the proportion of cells with aggregates was normalized against the size of the cell population. I, proportion of cells with abnormal nuclei after expression of EGFP-HDQ72 was turned off. Long term-induced cells (LT) were counted at different time points (1, 2, and 3 weeks) after the medium was replaced with medium without inducer. Three independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per population per experiment. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001; UN, uninduced EGFP-HDQ72 cells. J, confocal microscopy showing the nuclear morphology of uninduced EGFP-HDQ72 and induced EGFP-HDQ23 and EGFP-HDQ72 cells 3 weeks after EGFP-HDQ72 expression was turned off. Scale bar: 25 μm. DIC, differential interference contrast.

In addition to this we examined whether the formation of aggresomes and the occurrence of abnormal nuclei are reversible. In long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells, when the gene encoding the polyQ protein was switched off, the aggresomes disappeared over ∼6 days in culture (Fig. 1, G and H). This shows that cells can degrade aggresomes if the proteostasis systems are not overwhelmed by aggregating species. Furthermore, as aggresomes are cleared, there is a reduction in the rate of nuclear abnormalities to basal levels (Fig. 1, I and J).

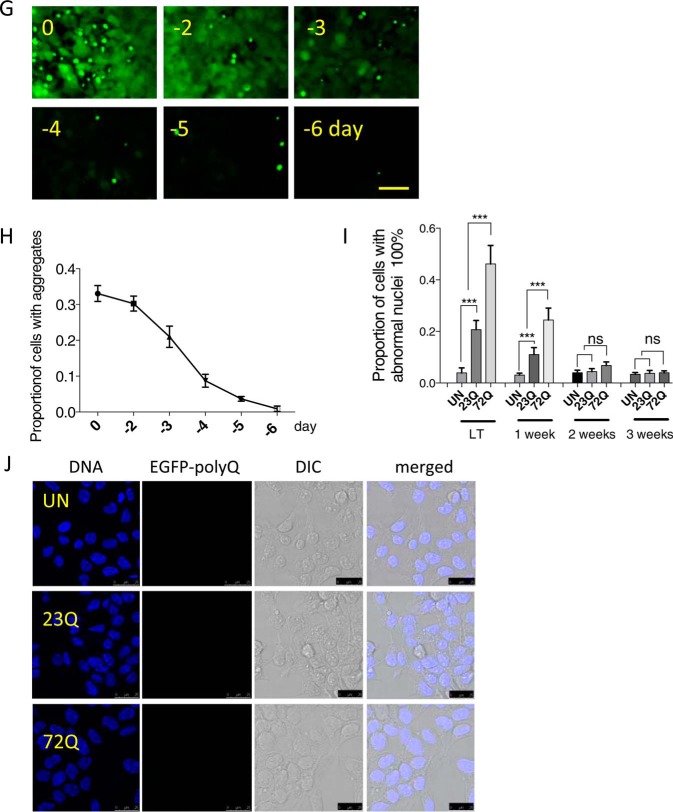

DNA Double-strand Breaks Are Prevalent in Aggresome-containing Cells

The presence of abnormal nuclei within aggresome-containing cells suggests that the genome experiences stress due to the accumulation of polyQ proteins and that DNA damage could occur. Indeed, it has been reported that DSBs are elevated in mouse models of some neurodegenerative diseases (20–22). DSBs generally recruit and activate the ataxia telangiectasia mutated (ATM) kinase, which phosphorylates several substrates including H2AX (23). As a DSB marker, phosphorylated (Ser-139) H2AX (γ-H2AX) coordinates virtually every aspect of the DNA damage response (24). We therefore tested for DSBs by examining cells for the presence of γ-H2AX in immunostaining and immunoblotting experiments. Confocal microscopy showed that in cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 for 3 months, γ-H2AX foci were present in 50.4% of the population containing aggresomes (Fig. 2, A and B). In EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes, a significantly lower proportion of the population contained γ-H2AX foci in the nucleus, similarly to cells expressing EGFP-HDQ23 (Fig. 2B). In contrast to the etoposide-treated positive control (uninduced EGFP-HDQ23 cells), in which DSB breaks are apparently widely dispersed throughout the genome, EGFP-HDQ72 cells display discrete γ-H2AX foci (Fig. 2A), suggesting that DNA damage is highly localized.

FIGURE 2.

DNA double-strand breaks occur in aggresome-containing cells. A, confocal microscopy showing immunostaining of γ-H2AX. Long term (three month) expression of EGFP-HDQ72 led to the formation of γ-H2AX foci in the nuclei of cells that contain aggresomes. Positive control: 3-month cultures of EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with 25 μm etoposide for 8 h. Negative control: untreated 3-month cultures of EGFP-HDQ23 cells. B, quantitation of cells with γ-H2AX foci in nuclei (from confocal microscopy data). Half (50.4%) of aggresome-containing EGFP-HDQ72 cells had DSBs, whereas this proportion was much reduced (∼15%) in EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes and in negative control EGFP-HDQ23 cells. Three independent experiments are represented with ∼200 EGFP-HDQ72 or EGFP-HDQ23 cells assessed per experiment. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. C, immunoblotting of γ-H2AX in long term (3 months) cell cultures. Left panel, an elevated level of γ-H2AX was present in EGFP-HDQ72 cells (EGFP-HDQ72) compared with the negative controls, uninduced EGFP-HDQ72 cells (UN), and EGFP-HDQ23 cells (EGFP-HDQ23). The positive control was long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with 25 μm etoposide for 8 h. D, γ-H2AX protein level correlates with polyQ expression level. SNAP-HDQ72 expression of long term-induced cells (3 months) was driven from either weak (W), intermediate-strength (I), or strong (S) promoters. UN (−) represents uninduced SNAP-HDQ72 cells (strong promoter) as the negative control. E, quantitation of cells with γ-H2AX foci in the nucleus. Confocal microscopy shows that the proportion of cells containing γ-H2AX foci correlates with polyQ expression levels controlled by weak (W), intermediate-strength (I), or strong (S) promoters. Samples are from cells with long term (3 months) EGFP-HDQ72 expression. Three independent experiments were performed with ∼200 cells assessed per population per experiment. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. F, γ-H2AX levels increased after expression of EGFP-HDQ72 for 2 weeks. γ-H2AX levels increased during a longer period (5 weeks) of consistent expression of EGFP-HDQ72. UN (−) represents uninduced SNAP-HDQ72 cells (strong promoter) as the negative control. G, γ-H2AX levels increased after expression of EGFP-HDQ72 for 2 weeks and reached peak levels after 4 weeks.

Immunoblotting confirmed that γ-H2AX accumulates in long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells to a greater extent than in uninduced cells or in long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells (Fig. 2C). Our previous data (19) showed that the rate of formation, penetrance, and morphology of aggresomes within the cell population are dependent on polyQ expression level. We therefore investigated whether a similar correlation pertains between polyQ expression level and the presence of DSBs using three independent, single-copy cell lines where SNAP-HDQ72 expression is driven by low, intermediate-strength, or strong promoters. Immunoblotting and immunostaining experiments demonstrated that both the amount of γ-H2AX protein and the proportion of cells containing γ-H2AX foci were higher in cells expressing polyQ protein from a strong promoter than from weak or intermediate-strength promoters (Fig. 2, D and E). A time-course experiment showed that γ-H2AX began to accumulate ∼10 days after induction of SNAP-HDQ72 expression from the strong promoter (Fig. 2, F and G), reaching peak levels after 30 days (Figs. 2G and 3A). Thus, the long term persistence of aggresomes in cells increases the incidence of highly localized DSBs, as shown by the presence of γ-H2AX loci in most abnormal nuclei, and this effect is expression level-dependent.

FIGURE 3.

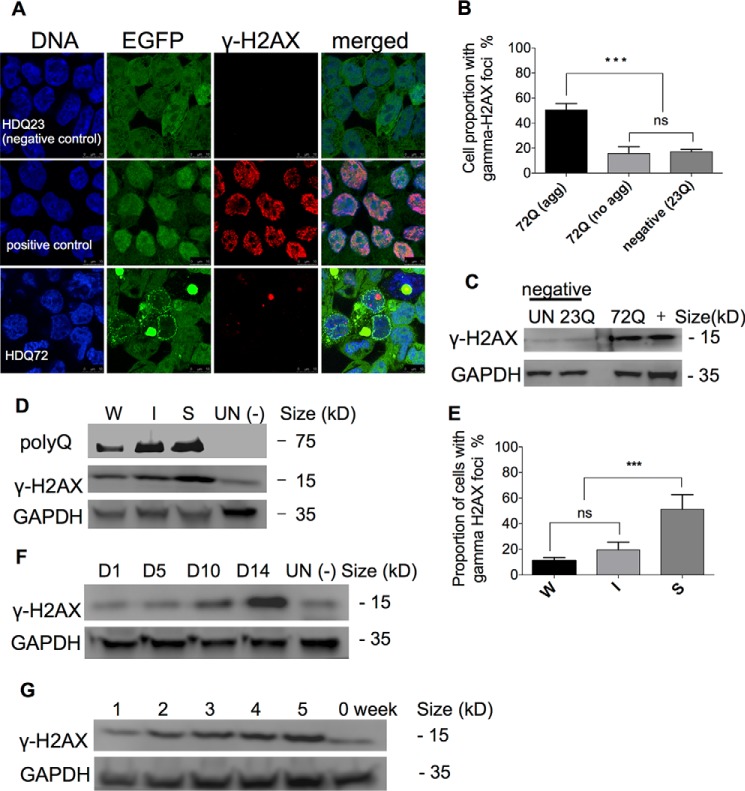

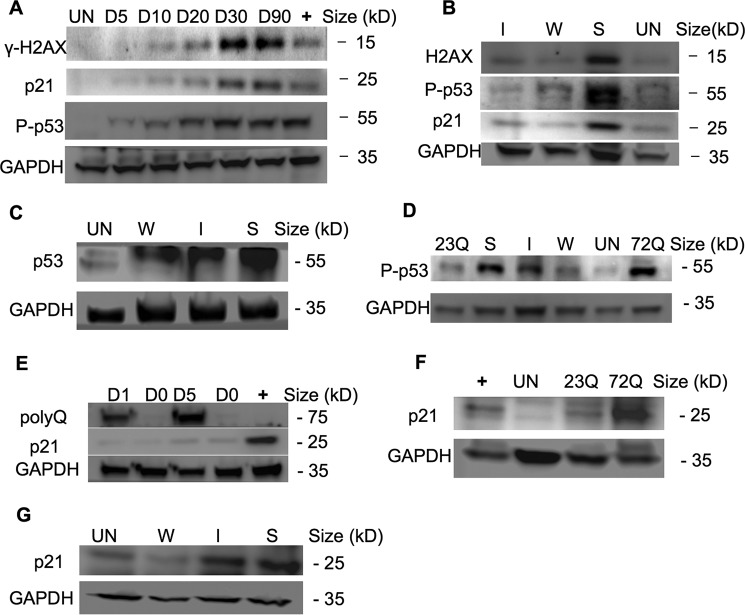

p53 activates the DNA damage checkpoint in aggresome-containing cells, leading to mitotic arrest. A, γ-H2AX, P-p53 (Ser-15), and p21 were gradually elevated in EGFP-HDQ72 cells over a 3-month expression period. Bar charts show the quantification of γ-H2AX, P-p53, and p21 normalized against GAPDH. Positive control: long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm) for 8 h to activate P-p53. Un, uninduced cells. B, immunoblotting showed P-p53 (Ser-15) and p21 are correlated with polyQ expression level, which increases with polyQ expression driven by weak (W), intermediate-strength (I), or strong (S) promoters. Bar charts show the quantification of γ-H2AX, P-p53 (Ser-15), and p21 normalized against GAPDH. C, overall p53 level was significantly elevated in cells in which SNAP-HDQ72 expression was driven by a strong promoter over a 3-month period. Uninduced EGFP-HDQ23 cells were used as the negative control. D, P-p53 (Ser-15) was significantly elevated in cells in which EGFP-HDQ72 and SNAP-HDQ72 expression was driven by a strong promoter over a 3-month period. E, expression of p21 lagged behind polyQ expression. The positive control was uninduced EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm) for 8 h. F, p21 levels were significantly elevated in long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells while remaining low level in uninduced and EGFP-HDQ23 cells. The positive control was long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm) for 8 h. G, immunoblotting showed p21 levels were correlated with polyQ expression level. SNAP-HDQ72 expression was driven by weak (W), intermediate-strength (I), or strong (S) promoters.

p53 Activates the DNA Damage Checkpoint in Aggresome-containing Cells

If DSBs are not repaired, ATM will further phosphorylate p53 (Ser-15) (25). This leads to stabilization of p53, which thus promotes the transcription of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 leading to arrest of the cell cycle at the G1/S transition (26) or which initiates apoptosis (27). We used immunoblotting to investigate whether P-p53 (Ser-15) is more prevalent in aggresome-containing cells and found that long term expression of EGFP-HDQ72 caused a gradual increase in P-p53 (Ser-15) levels over a 3-month period (Fig. 3, A and B). We also observed a correlation between P-p53 (Ser-15) level and the degree of polyQ expression, with strong expression of EGFP-HDQ72 giving rise to the most P-p53 (Ser-15) (Fig. 3B). Overall levels of p53 also vary with EGFP-HDQ72 expression level and induction time (Figs. 1B and 3C). Induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells accumulate a limited amount of P-p53 (Ser-15), although much less than EGFP-HDQ72 cells (Fig. 3D), whereas uninduced EGFP-HDQ72 cells have negligible amounts (Fig. 3, A, B, and D). The effect of P-p53 (Ser-15) on induction of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 was also observed in aggresome-containing cells; compared with negative controls, p21 was up-regulated with increasing P-p53 (Ser-15) levels (Fig. 3, A and B). The level of p21 induction correlated with the strength of the promoter used to drive polyQ expression (Fig. 3, B and G).

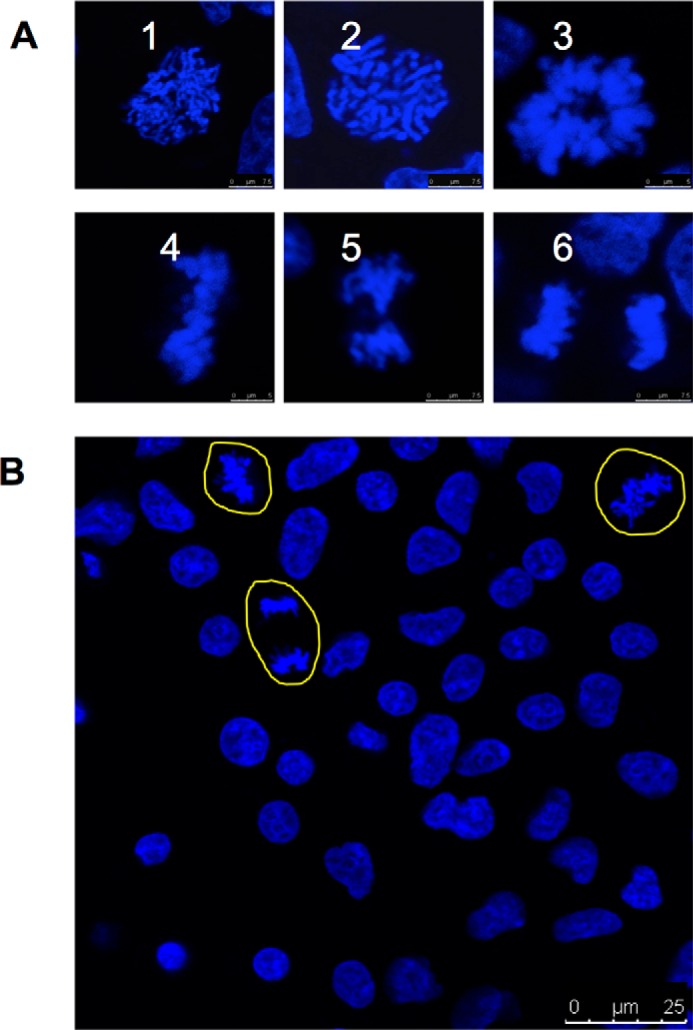

Cell Cycle Arrest in Aggresome-containing Cells

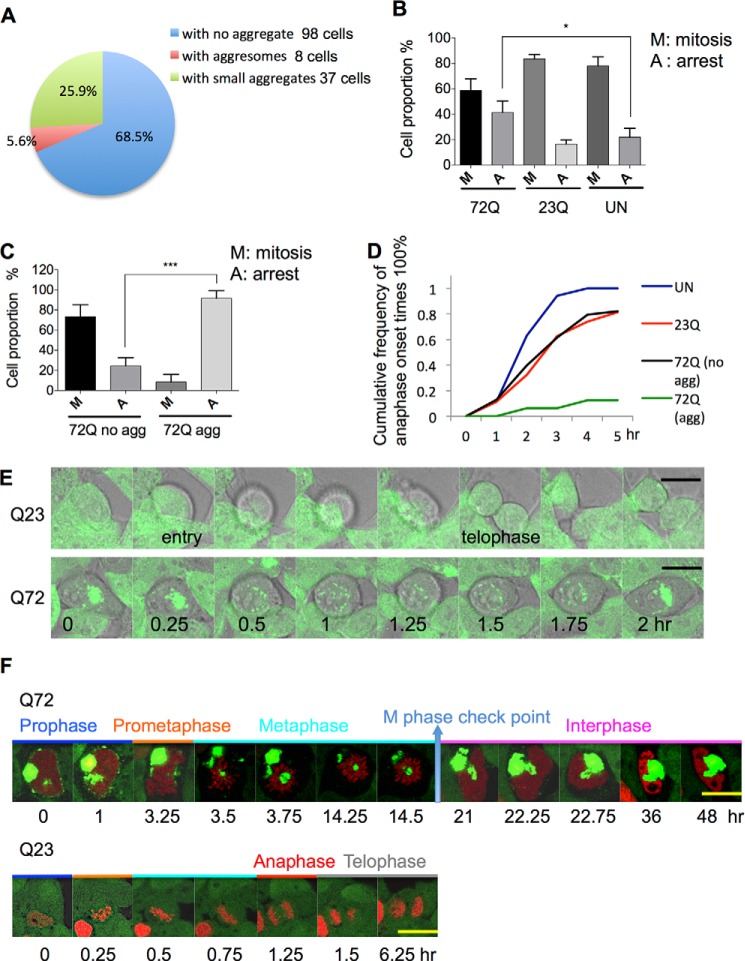

Elevated levels of p53 and p21 are associated with arrest in G1 phase of the cell cycle (28–30). Therefore, we investigated whether cells with aggresomes resulting from long term polyQ expression experienced cell cycle arrest by quantifying the proportion of the cell population in mitosis. Mitotic cells in fixed samples were identified by the presence of individual chromosomes, with representative examples shown in Fig. 4. Cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 over the long term have a lower proportion of cells in mitosis than uninduced cells or cells expressing EGFP-HDQ23. Cell counting shows that among EGFP-HDQ72 cells, those containing aggresomes composed only ∼5.6% of the whole mitotic population (Fig. 5A). Because ∼25% of long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells contain aggresomes, this suggests that a proportion of EGFP-HDQ72 cells do not enter mitosis. This cell cycle arrest was thus consistent with the up-regulation of p21 in these cells.

FIGURE 4.

Examples of mitotic cells. A, examples of mitotic cells in fixed samples stained with Hoechst 33352. 1–3, prophase, prometaphase, and metaphase (vertical view). 4–6, metaphase (front view), anaphase, and telophase. Scale bar: 7.5 μm. B, examples of mitotic cells in long term induced cells. Cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33342. Yellow outlines indicate mitotic cells (other cells are not in mitosis). Scale bar: 25 μm.

FIGURE 5.

Cell cycle arrest in aggresome-containing cells. A, quantitation of mitotic cells in the EGFP-HDQ72 cell population after long term (3 months) expression of polyQ. Samples were fixed and analyzed by cell counting by confocal microscopy. As mitotic cells represent a small proportion among the whole population, ∼600 cells were assessed per experiment for three independent experiments, and 143 mitotic cells were counted in total. Mitotic cells were defined as the change of nucleus morphology if its intact structure was replaced by individual chromosomes. B, quantitation of mitotic arrest in different cell lines from time-lapse recording. Sixty percent of long term EGFP-HDQ72-expressing cells (both with and without aggresomes) successfully proceeded through mitosis, whereas 40% of them arrested. In the negative controls, 80% of cells proceeded through mitosis. Three independent experiments were performed. ∼600 cells per population per experiment were analyzed, which gave ∼40 mitotic cells assessed per population per experiment. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. *, p < 0.05; ns, not significant. C, quantitation of mitotic arrest in long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells. ∼80% of cells without aggresomes proceeded through mitosis but only 10% of aggresome-containing cells. Therefore, a large number of cells (∼600) was assessed per experiment for three independent experiments. Of all cells assessed, there were 133 mitotic cells consisting of 32 aggresome-containing cells and 101 cells without aggresomes. The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001; ns, not significant. D, analysis of time-lapse images shows the cumulative frequency of telophase onset times. Mitotic entry was defined as detachment of the cell from the bottom of the Petri dish and spherical morphology. Telophase was defined by division into two daughter cells. Aggresome-containing cells are significantly delayed, and most of them exit mitosis after a long arrest. UN, uninduced cells; EGFP-HDQ23, long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells; EGFP-HDQ72, long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells with or without aggresomes. Three independent experiments were performed. ∼600 cells per population per experiment were analyzed, which gave ∼40 mitotic cells assessed per population per experiment. E, time-lapse images recorded by confocal microscopy of long term-induced EGFP-HDQ23 and EGFP-HDQ72 cells during 2 h of mitosis at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Mitosis was defined as the duration of cell detachment from the bottom of the Petri dish, with a spherical morphology. The EGFP-HDQ23 cells successfully divided into two daughter cells after 1.5 h (24/29: observed in 24 cells of 29 assessed). The aggresome-containing EGFP-HDQ72 cells arrested partway through the process and finally exited mitosis (12/14). Scale bar, 7.5 μm. The time scale and intervals are the same in both sequences. F, time-lapse images of EGFP-HDQ23 and EGFP-HDQ72 cells expressing histone-DsRed during mitosis at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Aggresomes are the large green structures, whereas nuclei and chromosomes are in red. Mitosis was defined by the duration of cell detachment from the bottom of the Petri dish, with a spherical morphology. Telophase was taken as the end of mitosis. The aggresome-containing EGFP-HDQ72 cell arrested partway in metaphase and exited mitosis after >5 h. An EGFP-HDQ23 cell is shown as a control in the lower panel. Each mitotic phase is marked by a different color and is labeled. Scale bar, 10 μm.

Next we asked whether cells expressing polyQ proteins could pass mitotic checkpoints and thereby progress through mitosis by recording time-lapse videos of long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 and EGFP-HDQ23 cells (Fig. 5, B, C, and D). Mitotic entry was defined by a cell's spherical morphology as it detached from the bottom of the Petri dish (entry in Fig. 5E). Telophase was identified as the division of two daughter cells (Fig. 5E, upper sequence), whereas mitotic arrest was defined by cell reattachment to the Petri dish without cell division (Fig. 5E, lower sequence). Cell counting based on these recordings revealed a higher level of mitotic arrest in cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 over the long term than in uninduced cells or in cells expressing EGFP-HDQ23 (Fig. 5B). When the EGFP-HDQ72 cell population was divided into cells with and without aggresomes, a marked difference was observed, with mitotic arrest in 92% of aggresome-containing cells and only control levels (24%) of mitotic arrest in EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes (Fig. 5C). Within 5 h of entering mitosis, almost all uninduced cells have completed this phase of the cell cycle (Fig. 5D). The proportion of cells completing mitosis is slightly lower in EGFP-HDQ23 cells and in EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes but drops to 10% in aggresome-containing EGFP-HDQ72 cells (Fig. 5D). A representative set of images from time-lapse recordings of a dividing cell expressing EGFP-HDQ23 and an aggresome-containing EGFP-HDQ72 cell that fails to progress through mitosis is presented in Fig. 5E. Together, these data indicate a significant cell cycle failure in cells containing aggresomes.

By labeling chromatin with a fluorescently tagged histone, we next examined the phase of mitosis at which aggresome-containing cells arrest. In the example presented, time-lapse confocal microscopy images show that perinuclear aggresomes occupying a large volume arrest the cell at the metaphase checkpoint (Fig. 5F). In the example shown, a large aggresome is localized in the center of the metaphase plate. This cell was unable to segregate its chromosomes, and after 30 h it finally exited the cell cycle (Fig. 5F, upper row). After reassembly of the nuclear envelope, half the nucleus was occupied by the aggregate, which left the cell with a malformed nucleus and double the normal complement of chromosomes. In contrast, a cell expressing EGFP-HDQ23 is shown successfully passing though all checkpoints and forming two daughter cells over a much shorter period (Fig. 5F, bottom row).

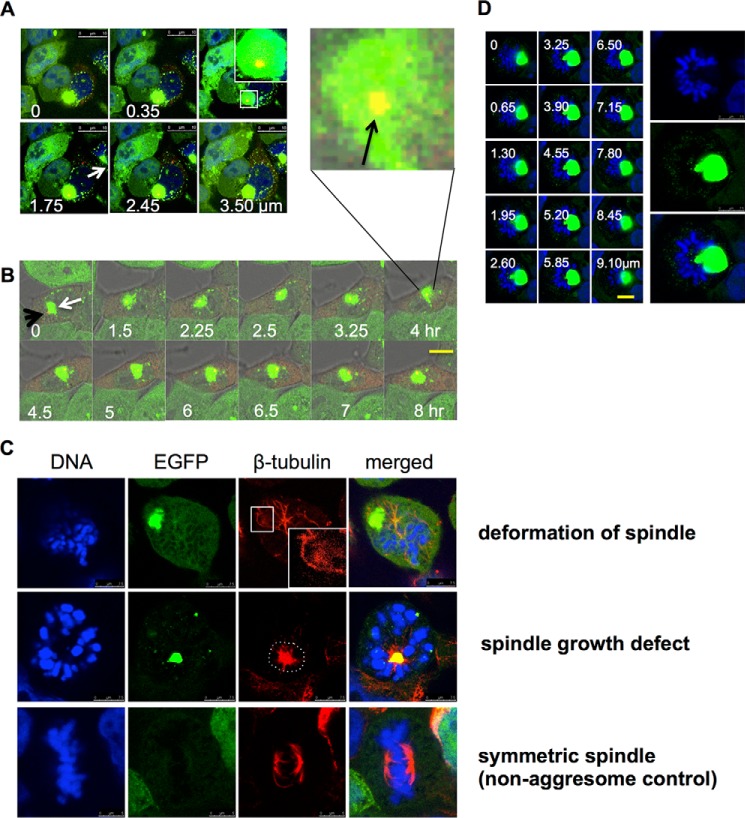

Disruption of Mitotic Spindle Apparatus Function by Aggresomes

Although, as described above, cells with large aggresomes are unlikely to enter mitosis, we were interested to observe the effects of such aggresomes on the mitotic apparatus in those few cells that managed to proceed. Thus, we investigated whether perinuclear aggresomes associate with the mitotic apparatus, including the centrosome(s) and the mitotic spindle. Aggregates of misfolded proteins are known to accumulate close to the centrosome (8) or MTOC, although no direct effect on the centrosome or the microtubules themselves has previously been reported. We first confirmed the colocalization of aggresomes and centrosomes by transfection of fluorescently tagged pericentrin into cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 over the long term. Imaging of fixed cells by confocal microscopy demonstrated that centrosomes localize to the edge of aggresomes and in many cases, representing ∼90% (16/18) of the aggresome-containing cell population, may be trapped inside (Fig. 6A). Tracing the movement of aggresome and centrosome by time-lapse image capture showed that the centrosome moves together with the aggresome throughout the recording process (Fig. 6B; of eight cells recorded, six cells suffered from this problem). Thus, the aggresome not only colocalizes with the centrosome but can also strongly interact with it and even engulf it, which seems likely to exert a negative influence on centrosome dynamics and mobility.

FIGURE 6.

Disruption of mitotic apparatus function by aggresomes. A, Z-stack imaging shows a centrosome trapped inside an aggresome. Long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells transfected with a pericentrin-mCherry expression construct were fixed and analyzed by confocal microscopy. The white arrow indicates an aggresome, whereas the orange spot in the middle of aggresome is pericentrin. White font labels indicate the depth of each image. Scale bar, 10 μm. B, time-lapse experiments recorded the movement of a centrosome with an aggresome in a long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cell, which was transfected with a pericentrin-mCherry construct at 37 °C and 5% CO2. During the whole recording, pericentrin (orange spot) was accompanied by the aggresome (green cluster). The white arrow indicates the aggresome, whereas the black arrow indicates pericentrin (orange spot). Scale bar, 10 μm. C, representative confocal images show the interference of the aggresome with mitotic spindles and associated deformation (top row) (9/14: among 14 mitotic cells with aggresomes, 9 cells had this defect) and growth defects (middle row) of microtubules (5/14). Long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells were fixed and stained for β-tubulin. Control cells (without an aggresome) have symmetric spindle microtubules (bottom row) (52/52). D, representative Z-stack images show an aggresome dominating the MTOC, with marked effects on the organization of the mitotic plate in 6 cells of 21 assessed. White font labels indicate the depth of each image. Scale bar, 5 μm.

During prophase, the replicated centrosomes normally migrate to opposite poles of the cell, forming two highly dynamic mitotic spindles. The lengthening and shortening of spindle microtubules determines to a large extent the shape of the mitotic spindle and promotes the proper alignment of chromosomes at the spindle plate. To investigate whether the presence of aggresomes interferes with mitotic spindle function, we examined both the structure and spatial distribution of spindles and chromosomes in aggresome-containing cells that were attempting to perform mitosis. In long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells, we observed various spindle defects whereby microtubules were apparently deformed or distorted when in close proximity to aggresomes; the resulting spindle structures seem incommensurate with successful chromosome segregation. For example, the top row, third column of Fig. 6C (enlarged in the inset) shows a microtubule deformed around an aggresome. The middle row of Fig. 6C shows an aggresome located at the MTOC blocking the formation of the mitotic spindle; microtubules are concentrated at the MTOC rather than radiating from it. By contrast, the bottom row of Fig. 6C shows an EGFP-HDQ72-expressing cell without an aggresome in which spindle fibers attach correctly to chromosomes. In another example, an aggregate occupying a large cell volume (typically a juxtanuclear aggresome) displaces chromosomes, resulting in a misshapen chromosome plate (Fig. 6D), which will certainly block the MTOC and the formation of spindle. In all cases (12 counted) where large aggresomes occupy the center of the cell and interact with chromosomes or microtubules, the above problems were observed.

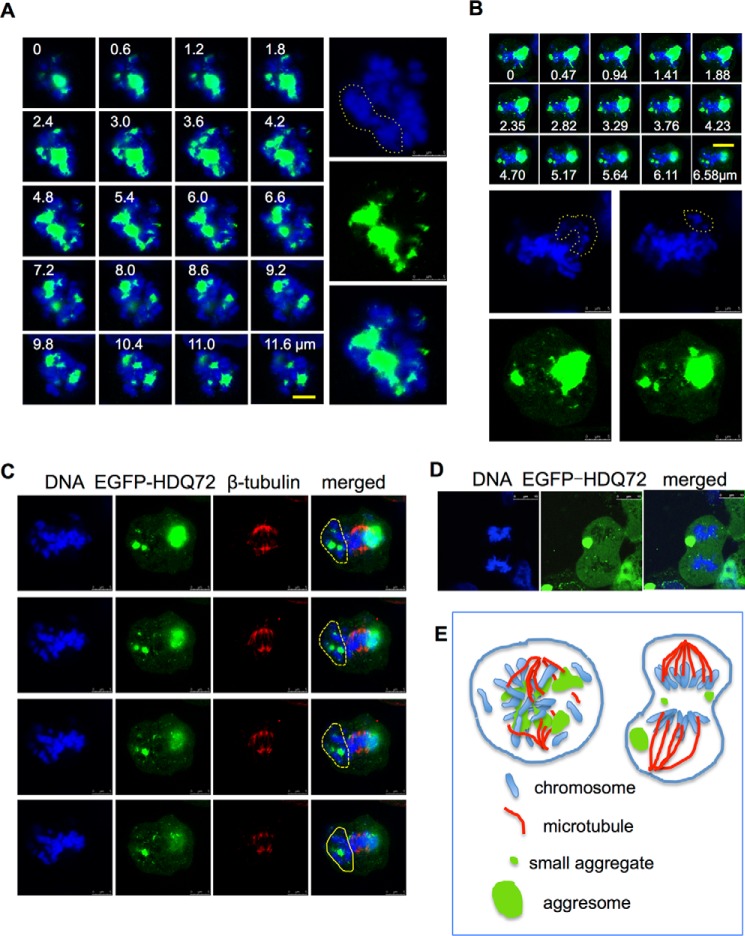

Three-dimensional Z-stack confocal microscopy revealed that the effects of aggregates on the spindle and metaphase chromosomes are highly dependent on aggregate size and position. These large aggregates can also cause some chromosomes to become separated from the main group, apparently blocking the attachment of microtubules (Fig. 7, A, B, and C). Any kinetochores that remain unattached to the spindle as a result are likely to prevent the transition from metaphase to anaphase, which could explain the mitotic arrest at the metaphase checkpoint that we observe in aggresome-containing cells (Fig. 5F). Equally seriously, where aggresomes or large aggregates are spatially interspersed among the chromosomes, the alignment of chromosomes and proper formation of spindles are disrupted, and the genetic material becomes tangled with aggregates, forming a twisted and expanded structure rather than a properly condensed chromosome (Fig. 7, A and B). Occasionally during mitosis, aggresomes may move from the center to the periphery of the cell (Fig. 7D). In this very rare situation (only 2 cases of 64 were observed) aggresomes do not interact strongly with centrosomes, and the cell can successfully pass the metaphase spindle checkpoint and enter anaphase (Fig. 7D). Nevertheless, in the vast majority of cases, aggresomes can disrupt mitosis by physical interaction with the mitotic apparatus (Fig. 7E) in addition to causing DNA damage-dependent cell cycle arrest.

FIGURE 7.

Disruption of chromosome alignment by aggresomes. A and B, representative Z-stack images of the spatial interference of aggresome in the mitotic nucleus. Long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells were fixed and analyzed by cell counting by confocal microscopy. In the 21 mitotic cells with aggresomes, 9 had this problem. Data shown below were collected using the same method. Yellow dashed lines highlight portions of the DNA segregated by the aggresome. White font labels indicate the depth of each image (in μm). Scale bar, 5 μm. C, representative Z-stack images of the spatial interference of the aggresome with spindles. Yellow dashed lines highlight portions of the DNA segregated by the aggresome, which blocks the attachment with microtubules. White font labels indicate the depth of each image (in μm) (four cells of 14 assessed). Scale bar, 5 μm. D, confocal microscopy images of a cell in anaphase with multiple aggregates and an aggresome at the periphery of the cytoplasm (two cells of 21 assessed). Scale bar, 10 μm. E, schematic model of aggresome interference with chromosome and spindle organization. Left, if an aggresome (green) is positioned at the center of the cell, it can lead to spatial disorganization of chromosomes (blue) and spindles (red) and subsequent mitotic defects. If the aggresome is located more peripherally, it has less of an effect on cell division.

Long Term Accumulation of Aggresomes Can Initiate Apoptosis

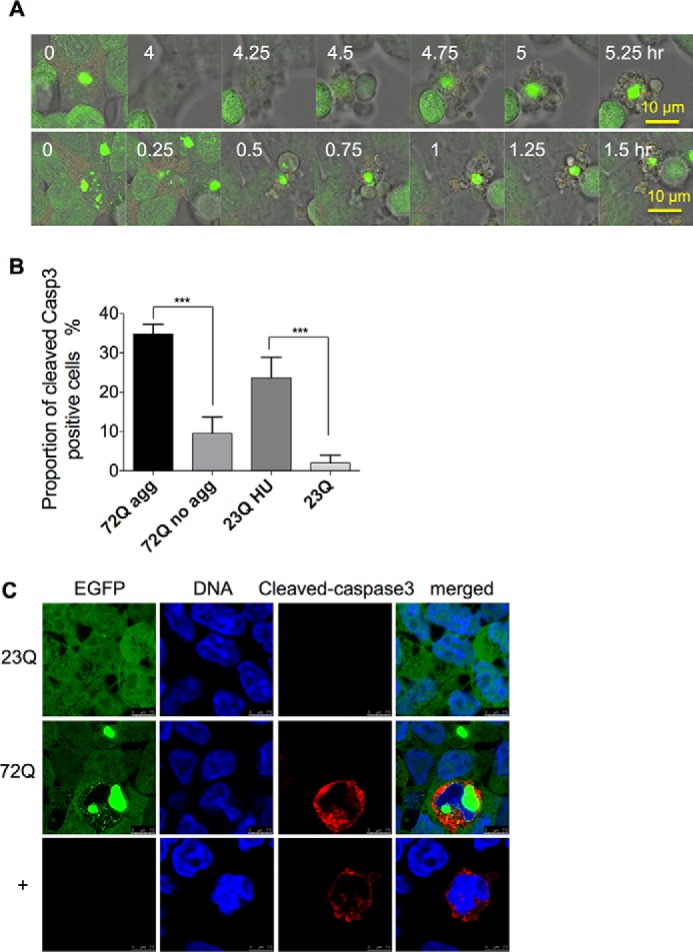

Both the occurrence of DSBs and disruption of mitosis can initiate apoptosis (31, 32). Time-lapse confocal microscopy showed that some aggresome-containing cells do undergo apoptosis (Fig. 8A); in these cases, cell shrinkage and blebbing occurred within 2 h, during which aggresomes maintained integrity. One of the key effectors of apoptosis is the protease caspase-3, which is itself cleaved and activated by initiator caspases and which proteolytically degrades many cell proteins to execute the cell death program (33, 34). Immunostaining for cleaved caspase-3 showed an increased proportion of cells with positive signals in long term-induced EGFP-HDQ72 cells with aggresomes compared with EGFP-HDQ72 cells without aggresomes and EGFP-HDQ23 cells (Fig. 8, B and C). Thus, the presence of cleaved caspase-3 correlates with the presence of aggresomes and abnormal nuclei; 91% of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells have abnormal nuclei.

FIGURE 8.

Aggresome-containing cells undergo apoptosis. A, time-lapse confocal microscopy of apoptosis in two representative aggresome-containing cells. The process can take from 2 h to 5 h. Live samples of long term-induced (3 months) EGFP-HDQ72 cells were recorded by confocal microscopy, which demonstrated three apoptotic cells among 12 aggresome-containing cells. B, quantitation of cells positive for cleaved caspase-3. Apoptosis in cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 over the long term (3 months) is strongly correlated with the presence of aggresomes. EGFP-HDQ23 cells treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm for 8 h) act as the positive control, and EGFP-HDQ23 cells act as the negative control. Three independent experiments were carried out, with ∼200 cells assessed per experiment in each sample (EGFP-HDQ72, EGFP-HDQ23, and EGFP-HDQ23 hydroxyurea (HU)). The chart represents the mean ± S.D. Samples were analyzed by binary logistic regression. ***, p < 0.001. C, immunostaining of cleaved caspase-3 in long term-induced (3 months) EGFP-HDQ72 cells showed that a proportion of EGFP-HDQ72 cells undergoes apoptosis. Negative control: long term induced EGFP-HDQ23 cells. Positive control: uninduced cells treated with hydroxyurea (1.5 mm for 8 h).

Discussion

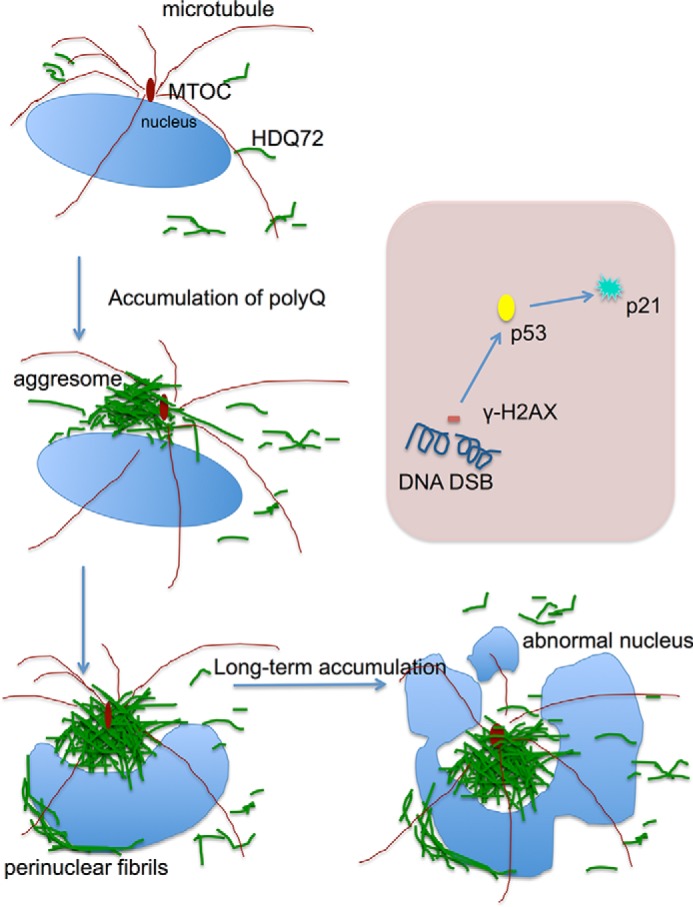

PolyQ aggregation has a detrimental effect on spatial organization of the nucleus (1). It has been reported (7, 8) that nuclear indentation and disruption of the nuclear envelope occurs in cells with aggresomes formed from integral membrane proteins. Such abnormal nuclear morphology has been interpreted as a sign of the toxicity of intracellular protein aggregation (6, 7). However, the mechanisms of this effect are not clear. We approached this question using long term expression of polyQ proteins in stable cell lines, which allowed us to model a more gradual, progressive pathology of polyQ aggregation. The accumulation of aggresomes over a 3-month period was accompanied by an increase in abnormal nuclear morphology and DSBs, resulting in failure to pass the p53-dependent checkpoint and subsequent mitotic arrest (Fig. 9). We also discovered that aggresomes can spatially interfere with chromosomes, centrosomes, and mitotic spindles, which probably contributes to mitotic arrest. Perhaps not surprisingly, therefore, all these lead to the activation of caspase-dependent apoptosis in aggresome-containing cells at last. Although apoptotic cells represent a minor population (35%) in aggresome-containing cells, this incidence is still much higher than in cells with smaller cytoplasmic aggregates or no aggregates (9%). These detrimental effects require the presence of aggresomes in cells over a relatively long period, i.e. weeks or months. Thus, our findings do not necessarily contradict the results of other workers, who have suggested that aggresome formation is beneficial to cells (9, 14), if this protective effect is operative in the short term.

FIGURE 9.

Schematic of the process of aggresome formation and its progressive effects. The nucleus is shown in light blue, microtubules are in dark red, and polyQ72 is in green. During long term expression, polyQ-containing proteins are consistently expressed throughout the cytoplasm, and they gradually form an aggresome at the MTOC, which process is accompanied by polyQ fibrils covering the nuclear envelope. The aggresome formation is dependent on expression levels, as stronger promoters lead to higher incidence of aggresomes. The large volume occupied by aggresomes means they exert a strong steric interference on the mitotic machinery, resulting in perturbation of the formation of spindles and the alignment of chromosomes. The long term persistence of an aggresome leads to abnormal nuclei and a DNA damage response. At the molecular level (shown in the light pink box), long term accumulation of a juxtanuclear aggresome resulted in DSBs. This activates the DNA damage response, including the phosphorylation of H2AX and activation of p53-dependent cell cycle arrest. In summary, aggresomes generated by long term expression of aggregation-prone proteins have two major effects on the cells: DNA damage-induced cell cycle arrest and mitotic failure, with the latter caused by steric interaction between an aggresome and the mitotic machinery, including spindles and chromosomes.

There are relatively few studies of the effects of long term expression of polyQ proteins in cell models. However, Fig. 2D emphasizes the importance of a long term overview because pathological effects such as abnormal nuclear morphology only appear after a week or 10 days of polyQ expression and lag behind the formation of aggresomes. Transient expression experiments, which typically last only a few days, are therefore less likely to reproduce these phenomena. Long term expression of polyQ also allows us to observe the activation of P-p53(Ser-15) and p21 (Fig. 3) as well as cell cycle arrest (Fig. 5), which would be hard to detect in transient expression experiments. In this regard it is worth noting that polyQ pathology in patients is a gradual and cumulative process involving loss of specific neuronal subpopulations as the disease progresses (33, 34). In addition, we also find that aggresomes, once formed, seem to be persistent in cells if HDQ72 is consistently expressed. However, cells retain the capacity to remove both cytoplasmic aggregates and aggresomes if HDQ72 expression is switched off (Fig. 1, G and H). Although our experiments were carried out over only 3 months, a much shorter time frame than the course of a neurodegenerative disease, our observations are consistent with the need to assess pathological outcomes over more than a few days.

Neurodegenerative diseases are commonly associated with DNA damage and eventual apoptosis. Elevated DSB levels have been noted in mouse models of Alzheimer disease (20–22), and a reduction in levels of DSB repair proteins has been described in Alzheimer disease patients compared with age-matched controls (35–38). Expression of polyQ43 can activate ATM and phosphorylate H2AX in PC12 cells (39), and phosphorylated H2AX associated with DSBs has also been reported in neuronal cultures expressing mutant polyQ (40). Ku70 is a mediator of DNA damage repair in mutant Htt-expressing neurons (41), and exposure to polyQ can increase levels of reactive oxygen species, which precedes DNA damage and activation of the DNA damage response checkpoint (42). However, the precise mechanistic link between polyQ expression and DNA breakage is not known. Thus, it is not clear which form of polyQ protein, soluble monomers or oligomers, aggregates, or aggresomes, is responsible for DNA damage and whether this effect is immediate or the result of long term accumulation. We argue that the long term accumulation of aggresomes, rather than cytoplasmic polyQ per se, is a key factor in DSB formation, as cells expressing EGFP-HDQ72 but lacking aggresomes behave similarly to cells expressing a non-aggregating form of polyQ (EGFP-HDQ23). In our experiments DSBs were highly localized in certain areas of the nucleus. A study on DNA damage in models of aging has revealed that it is markedly increased in the promoters of genes with reduced expression in the aged cortex, such as genes coding for synaptic plasticity, vesicular transport, and mitochondrial function (43). It would be interesting to investigate, therefore, whether the DSBs in aggresome-containing cells are localized to specific genes.

As a higher incidence of cleaved caspase-3 arises in cells containing abnormal nuclei, most of which have perinuclear aggresomes, we conclude that long term accumulation of aggresomes rather than cytoplasmic soluble polyQ or other small aggregates leads to apoptosis. As cells with many small aggregates dispersed throughout the cytosol are quite rare in the whole population (<1%), it is difficult to draw solid conclusions on the effect of these dispersed aggregates compared with aggresomes. However, we did not observe cellular abnormalities, including damaged nuclei, DSBs, or apoptosis in these cells. All phenotypes associated with aggresome formation, including nuclear malformation, DNA double-strand breaks, and activation of p53 and p21, can lead to activation of caspase-dependent apoptosis. Of these, p53 plays a central role linking DNA damage to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. It was previously reported that in Huntington disease p53 expression is increased in brain cells (44) and that DNA damage induced by polyQ up-regulates p53 (45). We have now shown in our cell model that the activation of P-p53 (Ser-15) by long term aggresome accumulation leads to elevated p21 levels. As p21 regulates the cell cycle at the G1/S transition and induces G1 phase arrest in response to a variety of stimuli, this is the likely cause of the reduced numbers of aggresome-containing cells entering mitosis. Any event in this pathway, from DSB formation, the activation of p53, and up-regulation of p21 to cell cycle arrest, can lead to caspase-dependent apoptosis (27, 46, 47). Driven by long term deposition of juxtanuclear aggresomes, these events may, therefore, contribute to the activation of apoptosis. However, as caspase-dependent apoptosis can result from a variety of other pathways and stimuli (48), we cannot rule out the possibility that other stress responses activate apoptosis during long term accumulation of aggresomes.

Recent studies have shown that neuronal cell cycle re-entry is also associated with apoptosis in Huntington disease models (49–51). Increased expression levels of cyclin B, cyclin-dependent kinase (Cdk5), and E2F-1 in neurons mark re-entry into the cell cycle, which is associated with an increased incidence of apoptosis. However, what triggers this cell cycle re-entry, for example whether it is dependent on DNA damage, is unclear, as are the reasons for its lethality in neurons. Cell cycle re-entry in neuronal cells may be just one of the consequences of the accumulation of aggresomes. Whether an aggresome-containing neuron dies due to cell cycle re-entry or apoptosis resulting from DNA damage may depend on the genomic or proteomic context of a particular cell type and is far from well elucidated.

When polyQ proteins are expressed over the long term, the aggresomes that form are highly stable and long-lived, and their physical effect on the nucleus suggests they are robust structures. However, time-lapse video shows that they are also mobile and dynamic structures in cells (Figs. 5, E and F, and 6B) and may resolve into several smaller structures during mitosis (Fig. 7, A and B), although this is very rare. Furthermore, where the centrosome is apparently encapsulated by the aggresome, transfection with pericentrin demonstrates permeability to proteins within the cytoplasm to a certain degree (Fig. 6, A and B). This suggests material exchange between the inside and outside of the aggresome.

The effect of aggresome accumulation on mitosis provides a possible explanation for the neurodevelopmental defects observed in polyQ diseases. It has been reported that neural stem cells expressing a polyQ expansion protein suffer from impaired lineage restriction, reduced proliferative potential, and enhanced late-stage self-renewal (52), suggesting that polyQ pathology begins very early in the development of neural cells. Cell models expressing aggregation-prone polyQ proteins also experience problems with cell division, such as cell cycle arrest (51) and decreased proliferation (53). Furthermore, neuroimaging has shown that prodromal Huntington disease males have a smaller intracranial volume than controls, suggesting abnormal development in brain tissues expressing mutant Htt (54). Cell death associated with mitotic re-entry, as discussed above, may contribute to disease onset in mature patients with postnatal neurons; however, it cannot explain disorders that occur during neural development.

In addition, there is growing evidence that aggregation-prone polyQ proteins can also affect non-neuronal cells, for example, causing cardiac dysfunction and dilation in cardiomyocytes as well as reduced lifespan in mouse models (55). It has also been reported that, in a transgenic mouse model of Huntington disease, pancreatic β-cells suffer from reduced replication and deficient insulin secretion (56). Other effects on adipose tissues (57) and muscles (58, 59) have also been reported. It is not clear whether aggresomes form and are involved in the pathogenesis of these non-neuronal cells, but our results would suggest this as an intriguing avenue of exploration.

The aggresome occupies a considerable volume in the cell and might be expected to affect the function of cell organelles, particularly those in close proximity, such as the centrosome, the Golgi, and the nucleus. Our results demonstrate a strong interaction between centrosome and aggresome (Fig. 6), but further study is required to elucidate the molecular details of this interaction and its consequences, including the effect on the dynamics of spindle formation. When aggresomes occupy the same space as the mitotic spindle, the elongation of microtubules will be compromised, interfering with or preventing attachment to kinetochores. However, our results do not rule out other possible mechanisms by which aggresomes could precipitate defects in mitosis. Multiple lines of evidence demonstrate that the UPS is impaired by polyQ protein accumulation (60); thus, aggresomes might cause failure of the UPS to degrade key proteins, such as cyclins and securin, thereby leading to mitotic defects.

Author Contributions

A. T. and M. L. designed the experiments, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. M. L. performed the experiments and collected the data. C. B. helped perform the experiments and assisted with statistical analysis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Viji Draviam for histone 2B-DsRed and pericentrin-mCherry plasmids and for helpful advice and comments on the manuscript and Prof. David Rubinsztein for comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by an Advanced Investigator Award (AdG233232) from the European Research Council (to A. T.) and by scholarships from the Cambridge Overseas Trust and the Chinese Scholarship Council (to M. L.). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- UPS

- ubiquitin proteasome system

- ATM

- ataxia telangiectasia mutated

- DSB

- double-strand break

- MT

- microtubule

- MTOC

- microtubule organizing center

- polyQ

- polyglutamine

- P-p53

- phosphorylated p53

- SNAP

- soluble NSF attachment protein

- EGFP

- enhanced GFP.

References

- 1.Rubinsztein D. C. (2002) Lessons from animal models of Huntington's disease. Trends Genet. 18, 202–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lin M. T., and Beal M. F. (2006) Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature 443, 787–795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Voisine C., Pedersen J. S., and Morimoto R. I. (2010) Chaperone networks: tipping the balance in protein folding diseases. Neurobiol. Dis. 40, 12–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bingol B., and Sheng M. (2011) Deconstruction for reconstruction: the role of proteolysis in neural plasticity and disease. Neuron 69, 22–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ciechanover A., and Brundin P. (2003) The ubiquitin proteasome system in neurodegenerative diseases: sometimes the chicken, sometimes the egg. Neuron 40, 427–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martinez-Vicente M., Talloczy Z., Kaushik S., Massey A. C., Mazzulli J., Mosharov E. V., Hodara R., Fredenburg R., Wu D. C., Follenzi A., Dauer W., Przedborski S., Ischiropoulos H., Lansbury P. T., Sulzer D., and Cuervo A. M. (2008) Dopamine-modified α-synuclein blocks chaperone-mediated autophagy. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 777–788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Waelter S., Boeddrich A., Lurz R., Scherzinger E., Lueder G., Lehrach H., and Wanker E. E. (2001) Accumulation of mutant huntingtin fragments in aggresome-like inclusion bodies as a result of insufficient protein degradation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 12, 1393–1407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Johnston J. A., Ward C. L., and Kopito R. R. (1998) Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1883–1898 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Taylor J. P., Tanaka F., Robitschek J., Sandoval C. M., Taye A., Markovic-Plese S., and Fischbeck K. H. (2003) Aggresomes protect cells by enhancing the degradation of toxic polyglutamine-containing protein. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 749–757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olzmann J. A., and Chin L. S. (2008) Parkin-mediated K63-linked polyubiquitination: a signal for targeting misfolded proteins to the aggresome-autophagy pathway. Autophagy 4, 85–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hao R., Nanduri P., Rao Y., Panichelli R. S., Ito A., Yoshida M., and Yao T. P. (2013) Proteasomes activate aggresome disassembly and clearance by producing unanchored ubiquitin chains. Mol. Cell 51, 819–828 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nanduri P., Hao R., Fitzpatrick T., and Yao T. P. (2015) Chaperone-mediated 26S proteasome remodeling facilitates free K63 ubiquitin chain production and aggresome clearance. J. Biol. Chem. 290, 9455–9464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawaguchi Y., Kovacs J. J., McLaurin A., Vance J. M., Ito A., and Yao T. P. (2003) The deacetylase HDAC6 regulates aggresome formation and cell viability in response to misfolded protein stress. Cell 115, 727–738 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang Y., Meriin A. B., Zaarur N., Romanova N. V., Chernoff Y. O., Costello C. E., and Sherman M. Y. (2009) Abnormal proteins can form aggresome in yeast: aggresome-targeting signals and components of the machinery. FASEB J. 23, 451–463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park R., Wang'ondu R., Heston L., Shedd D., and Miller G. (2011) Efficient induction of nuclear aggresomes by specific single missense mutations in the DNA-binding domain of a viral AP-1 homolog. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 9748–9762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Burnett B. G., and Pittman R. N. (2005) The polyglutamine neurodegenerative protein ataxin 3 regulates aggresome formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4330–4335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chapple J. P., Bros-Facer V., Butler R., and Gallo J. M. (2008) Focal distortion of the nuclear envelope by huntingtin aggregates revealed by lamin immunostaining. Neurosci. Lett. 447, 172–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kazantsev A., Walker H. A., Slepko N., Bear J. E., Preisinger E., Steffan J. S., Zhu Y. Z., Gertler F. B., Housman D. E., Marsh J. L., and Thompson L. M. (2002) A bivalent Huntingtin binding peptide suppresses polyglutamine aggregation and pathogenesis in Drosophila. Nat. Genet. 30, 367–376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lu M., Williamson N., Boschetti C., Ellis T., Yoshimi T., Tunnacliffe A. (2015) Expression-level dependent perturbation of cell proteostasis and nuclear morphology by aggregation-prone polyglutamine proteins. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 112, 1883–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dobbin M. M., Madabhushi R., Pan L., Chen Y., Kim D., Gao J., Ahanonu B., Pao P. C., Qiu Y., Zhao Y., and Tsai L. H. (2013) SIRT1 collaborates with ATM and HDAC1 to maintain genomic stability in neurons. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 1008–1015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D., Frank C. L., Dobbin M. M., Tsunemoto R. K., Tu W., Peng P. L., Guan J. S., Lee B. H., Moy L. Y., Giusti P., Broodie N., Mazitschek R., Delalle I., Haggarty S. J., Neve R. L., Lu Y., and Tsai L. H. (2008) Deregulation of HDAC1 by p25/Cdk5 in neurotoxicity. Neuron 60, 803–817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suberbielle E., Sanchez P. E., Kravitz A. V., Wang X., Ho K., Eilertson K., Devidze N., Kreitzer A. C., and Mucke L. (2013) Physiologic brain activity causes DNA double-strand breaks in neurons, with exacerbation by amyloid-β. Nat. Neurosci. 16, 613–621 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burma S., Chen B. P., Murphy M., Kurimasa A., and Chen D. J. (2001) ATM phosphorylates histone μμ in response to DNA double-strand breaks. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 42462–42467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lukas J., Lukas C., and Bartek J. (2011) More than just a focus: the chromatin response to DNA damage and its role in genome integrity maintenance, Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 1161–1169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Canman C. E., Lim D. S., Cimprich K. A., Taya Y., Tamai K., Sakaguchi K., Appella E., Kastan M. B., and Siliciano J. D. (1998) Activation of the ATM kinase by ionizing radiation and phosphorylation of p53. Science 281, 1677–1679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rodriguez R., and Meuth M. (2006) Chk1 and p21 cooperate to prevent apoptosis during DNA replication fork stress, Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 402–412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Imreh G., Norberg H. V., Imreh S., and Zhivotovsky B. (2011) Chromosomal breaks during mitotic catastrophe trigger γH2AX-ATM-p53-mediated apoptosis. J. Cell Sci. 124, 2951–2963 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.el-Deiry W. S., Tokino T., Velculescu V. E., Levy D. B., Parsons R., Trent J. M., Lin D., Mercer W. E., Kinzler K. W., and Vogelstein B. (1993) WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell 75, 817–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.el-Deiry W. S., Harper J. W., O'Connor P. M., Velculescu V. E., Canman C. E., Jackman J., Pietenpol J. A., Burrell M., Hill D. E., and Wang Y. (1994) WAF1/CIP1 is induced in p53-mediated G1 arrest and apoptosis. Cancer Res. 54, 1169–1174 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bunz F., Dutriaux A., Lengauer C., Waldman T., Zhou S., Brown J. P., Sedivy J. M., Kinzler K. W., and Vogelstein B. (1998) Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science 282, 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bouwman P., and Jonkers J. (2012) The effects of deregulated DNA damage signalling on cancer chemotherapy response and resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bieging K. T., and Attardi L. D. (2012) Deconstructing p53 transcriptional networks in tumor suppression. Trends Cell Biol. 22, 97–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boatright K. M., and Salvesen G. S. (2003) Mechanisms of caspase activation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 725–731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paulson H. L., Bonini N. M., and Roth K. A. (2000) Polyglutamine disease and neuronal cell death. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 12957–12958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Adamec E., Vonsattel J. P., and Nixon R. A. (1999) DNA strand breaks in Alzheimer's disease. Brain Res. 849, 67–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jacobsen E., Beach T., Shen Y., Li R., and Chang Y. (2004) Deficiency of the Mre11 DNA repair complex in Alzheimer's disease brains. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 128, 1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mullaart E., Boerrigter M. E., Ravid R., Swaab D. F., and Vijg J. (1990) Increased levels of DNA breaks in cerebral cortex of Alzheimer's disease patients. Neurobiol. Aging 11, 169–173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shackelford D. A. (2006) DNA end joining activity is reduced in Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol. Aging 27, 596–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giuliano P., De Cristofaro T., Affaitati A., Pizzulo G. M., Feliciello A., Criscuolo C., De Michele G., Filla A., Avvedimento E. V., and Varrone S. (2003) DNA damage induced by polyglutamine-expanded proteins. Hum. Mol. Genet. 12, 2301–2309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Qi M. L., Tagawa K., Enokido Y., Yoshimura N., Wada Y., Watase K., Ishiura S., Kanazawa I., Botas J., Saitoe M., Wanker E. E., and Okazawa H. (2007) Proteome analysis of soluble nuclear proteins reveals that HMGB1/2 suppress genotoxic stress in polyglutamine diseases. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 402–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Enokido Y., Tamura T., Ito H., Arumughan A., Komuro A., Shiwaku H., Sone M., Foulle R., Sawada H., Ishiguro H., Ono T., Murata M., Kanazawa I., Tomilin N., Tagawa K., Wanker E. E., Okazawa H. (2010) Mutant huntingtin impairs Ku70-mediated DNA repair. J. Cell Biol. 189, 425–443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bertoni A., Giuliano P., Galgani M., Rotoli D., Ulianich L., Adornetto A., Santillo M. R., Porcellini A., and Avvedimento V. E. (2011) Early and late events induced by polyQ-expanded proteins: identification of a common pathogenic property of polyQ-expanded proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 4727–4741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu T., Pan Y., Kao S. Y., Li C., Kohane I., Chan J., and Yankner B. A. (2004) Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature 429, 883–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bae B. I., Xu H., Igarashi S., Fujimuro M., Agrawal N., Taya Y., Hayward S. D., Moran T. H., Montell C., Ross C. A., Snyder S. H, and Sawa A. (2005) p53 mediates cellular dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities in Huntington's disease. Neuron 47, 29–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Illuzzi J., Yerkes S., Parekh-Olmedo H., and Kmiec E. B. (2009) DNA breakage and induction of DNA damage response proteins precede the appearance of visible mutant huntingtin aggregates. J. Neurosci. Res. 87, 733–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pietenpol J. A., and Stewart Z. A. (2002) Cell cycle checkpoint signaling: cell cycle arrest versus apoptosis. Toxicology 181, 475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaina B. (2003) DNA damage-triggered apoptosis: critical role of DNA repair, double-strand breaks, cell proliferation, and signaling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 66, 1547–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Elmore S. (2007) Apoptosis: a review of programmed cell death. Toxicol. Pathol. 35, 495–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pelegrí C., Duran-Vilaregut J., del Valle J., Crespo-Biel N., Ferrer I., Pallàs M., Camins A., and Vilaplana J. (2008) Cell cycle activation in striatal neurons from Huntington's disease patients and rats treated with 3-nitropropionic acid. Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 26, 665–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fernandez-Fernandez M. R., Ferrer I., and Lucas J. J. (2011) Impaired ATF6α processing, decreased Rheb and neuronal cell cycle re-entry in Huntington's disease. Neurobiol. Dis. 41, 23–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu K. Y., Shyu Y. C., Barbaro B. A., Lin Y. T., Chern Y., Thompson L. M., James Shen C. K., and Marsh J. L. (2015) Disruption of the nuclear membrane by perinuclear inclusions of mutant huntingtin causes cell cycle re-entry and striatal cell death in mouse and cell models of Huntington's disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 24, 1602–1616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Molero A. E., Gokhan S., Gonzalez S., Feig J. L., Alexandre L. C., and Mehler M. F. (2009) Impairment of developmental stem cell-mediated striatal neurogenesis and pluripotency genes in a knock-in model of Huntington's disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 21900–21905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bufalino M. R., and van der Kooy D. (2014) The aggregation and inheritance of damaged proteins determines cell fate during mitosis. Cell Cycle 13, 1201–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nopoulos P. C., Aylward E. H., Ross C. A., Mills J. A., Langbehn D. R., Johnson H. J., Magnotta V. A., Pierson R. K., Beglinger L. J., Nance M. A., Barker R. A., Paulsen J. S., and PREDICT-HD Investigators and Coordinators of the Huntington Study Group (2011) Smaller intracranial volume in prodromal Huntington's disease: evidence for abnormal neurodevelopment. Brain 134, 137–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pattison J. S., Sanbe A., Maloyan A., Osinska H., Klevitsky R., and Robbins J. (2008) Cardiomyocyte expression of a polyglutamine preamyloid oligomer causes heart failure. Circulation 117, 2743–2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Björkqvist M., Fex M., Renström E., Wierup N., Petersén A., Gil J., Bacos K., Popovic N., Li J. Y., Sundler F., Brundin P., and Mulder H. (2005) The R6/2 transgenic mouse model of Huntington's disease develops diabetes due to deficient β-cell mass and exocytosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 565–574 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Phan J., Hickey M. A., Zhang P., Chesselet M. F., and Reue K. (2009) Adipose tissue dysfunction tracks disease progression in two Huntington's disease mouse models. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 1006–1016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sathasivam K., Hobbs C., Turmaine M., Mangiarini L., Mahal A., Bertaux F., Wanker E. E., Doherty P., Davies S. W., and Bates G. P. (1999) Formation of polyglutamine inclusions in non-CNS tissue. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 813–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ribchester R. R., Thomson D., Wood N. I., Hinks T., Gillingwater T. H., Wishart T. M., Court F. A., and Morton A. J. (2004) Progressive abnormalities in skeletal muscle and neuromuscular junctions of transgenic mice expressing the Huntington's disease mutation. Eur. J. Neurosci. 20, 3092–3114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ortega Z., and Lucas J. J. (2014) Ubiquitin-proteasome system involvement in Huntington's disease. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 7, 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shrestha R. L., Tamura N., Fries A., Levin N., Clark J., and Draviam V. M. (2014) TAO1 kinase maintains chromosomal stability by facilitating proper congression of chromosomes. Open Biol. 4, 130108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]