Abstract

Following a previous investigation of religio-spiritual beliefs in American Indians, this article examined prevalence and correlates of religio-spiritual participation in two tribes in the Southwest and Northern Plains (N = 3,084). Analysis suggested a “religious profile” characterized by strong participation across three traditions: aboriginal, Christian, and Native American Church. However, sociodemographic variables that have reliably predicted participation in the general American population, notably gender and age, frequently failed to achieve significance in multivariate analyses for each tradition. Religio-spiritual participation was strongly and significantly related to belief salience for all traditions. Findings suggest that correlates of religious participation may be unique among American Indians, consistent with their distinctive religious profile. Results promise to inform researchers’ efforts to understand and theorize about religio-spiritual behavior. They also provide tribal communities with practical information that might assist them in harnessing social networks to confront collective challenges through community-based participatory research collaborations.

Keywords: American Indians, religiosity, religio-spiritual practice, spirituality, social networks

Introduction

Survey data have allowed sociological analysis of patterns of religious participation in the American population (e.g., Finke and Stark 2005; Gallup and Lindsay 1999; Kosmin and Keysar 2006; Pew Forum 2008). Such work has taught researchers a great deal about religious behavior and its changes over time, confirming that spirituality remains a dynamic force in American lives. This same work has revealed distinctive “religious profiles” characterizing racial-ethnic subpopulations. African Americans, for example, are the “most religious” on measures such as denominational membership and belief in God, while Asian Americans are the least so; white Americans fall in between (Kosmin and Keysar 2006; Pew Forum 2008).

Yet if religious data are plentiful for the larger American racial-ethnic groups, they are scarce for smaller ones. Deficiencies in sociological knowledge are especially acute for American Indians. Although the most recent decennial census reported almost 5 million people identifying as American Indian or Alaska Native, either exclusively or in combination with other ancestries (U.S. Census Bureau 2011), sociologists have rarely surveyed large, tribal samples on issues relevant to religion or spirituality. Even when Americans Indians are included in national samples, they are typically lumped together into an “Other” racial category, making their data unavailable for separate analysis.

Rare exceptions to the neglect of American Indians in religious research include the large American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS). This random digit dial survey collected measures of religious identification, belonging, beliefs, and overall outlook in 2001; it amassed a sample of more than 50,000 Americans, including 680 American Indians (Kosmin and Keysar 2006). Although most American Indians reported belief in God (87 percent) and most described themselves as either “religious” or “somewhat religious” (77 percent), relatively few resided in households where someone held congregational membership (46 percent as compared to 56 percent of whites and 67 percent of African Americans). Most interestingly, American Indians were significantly more likely to describe themselves as having “no religion” (19 percent compared to 15 percent of whites and 11 percent of African Americans). Adding the 6 percent of American Indians who identified themselves as following “Other Religions” together with the 4 percent who declined to answer, ARIS researchers concluded that “around one-in-three Native Americans did not subscribe to mainstream forms of religion” (Kosmin and Keysar 2006:237–38); rather, these participants “still maintain[ed] their own religious patterns” that “set them apart from the national norms” (2006: 239).

Another relevant exception to the lack of sociological work on American Indians is our own previous analysis of data from the American Indian Service Utilization, Psychiatric Epidemiology, Risk and Protective Factors Project (AI-SUPERPFP). This population-based, in-person survey collected data from legally enrolled citizens of two federally recognized tribes who occupy three reservations in the Southwest and Northern Plains (N = 3,084). Prevalence, salience, and exclusivity of belief were examined in each of three religio-spiritual traditions common to both tribes: aboriginal, Christian, and the syncretic faith known as Native American Church (NAC) or Peyote Way. Analyses revealed a portrait of the country’s largest Indian reservations as sites of considerable religio-spiritual diversity: 95–99 percent of participants in both tribes described beliefs from at least one religio-spiritual tradition as either “somewhat” or “very important” and the majority of these ascribed high salience to beliefs from more than one tradition (Garroutte et al. 2009).1

Neither study just described addressed patterns of religio-spiritual behavior. They thus leave many questions about (1) the extent to which American Indians translate religious identifications and professions into actual participation, and (2) the variables associated with participation.

Why Patterns of Religious Participation Matter

Knowledge about tribal religious participation contributes to a religious profile for American Indians. It also promises to illuminate the extent to which variables that commonly predict religious participation in the general population may function differently within racial-ethnic subpopulations and in spiritual traditions distinct from mainstream Christianity.

At the same time, our inquiry matters for tribal communities. It may have special relevance to communities interested in harnessing social capital—local sources of strength and resilience—to meet challenges that they themselves prioritize (Putnam 2000).Agrowing number of projects with this goal have involved partnerships between research organizations and vulnerable communities under a model of “community-based participatory research.” Although such collaborative projects have addressed issues from economic development to public safety (Michael et al. 2008), many have targeted public health goals. Such work supports a conclusion that social networks are an especially valuable expression of communities’ social capital; they serve as information conduits, encourage stakeholder reciprocity, and provide access to hard-to-reach populations.

Community-based research has commonly recognized the vitality that can attend social networks implied in individuals’ specifically religious participations. Most work has involved African-American and sometimes Latino Christian churches, often with notable success (review in Campbell et al. 2007). Parallel efforts to tap networks of religious participation in service of public health goals are virtually nonexistent in American Indian contexts. The dearth of basic, quantitative data and analysis illuminating the extent and constitution of relevant networks in Indian country creates a serious obstacle.

Research Questions

Our project characterizes patterns of religio-spiritual participation on the three sampled reservations representing two disparate tribal groups, with attention to extent, overlap, and composition of associated networks. To what extent do individuals translate their known, high prevalence of belief salience (Garroutte et al. 2009) into actual participation in specific traditions? How much do participations overlap? What can models using sociodemographic correlates of participation reveal about subpopulations, such as elders or women, who may be especially represented in specific networks?

We begin with brief descriptions of the three religio-spiritual traditions common in our sampled tribes: aboriginal, Christian, and NAC. We examine prevalence of participation for each tradition. We then use regression models to examine correlates of religio-spiritual behavior, including sociodemographic characteristics and belief variables, specifically salience and exclusivity. Analyses proceed according to our assumption that, in work with American Indian populations, community confidentiality is as important as individual confidentiality (Norton and Manson 1996); thus, by agreement with participating tribes, we use general descriptors instead of tribal names.

Religio-Spiritual Participation in Native America

Discussions of American Indian religion and spirituality–including anthropological and autobiographical accounts and analyses of limited survey data collected from individual tribes–suggest a complex mix of at least three sets of beliefs and practices. These include aboriginal traditions, or spiritual paths rooted in traditions of this country’s indigenous peoples before European contact. In addition, they include Christian faiths, and “new” or syncretic traditions combining aboriginal and Christian elements (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992; Gill 1982). We discuss each of these traditions below.

Aboriginal Spirituality

The federal government formally acknowledges and maintains government-to-government relationships with more than 300 tribes in the lower 48 states (U.S. Department of the Interior 2010). These tribes, and communities within them, exhibit extensive cultural diversity including distinct forms of spirituality. Although typically specific to individual tribes, aboriginal spiritual expressions frequently display strong orientations to kinship and community and to a geographic place, with its seasonal cycles (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992; Hultkrantz 1987). Perhaps the most distinctive feature of aboriginal spiritualties is the extent to which they may be incorporated into all aspects of daily life. In all their cultural variability, America’s tribal peoples commonly unite around “ways of life in which economy, politics, medicine, art, agriculture, etc., are ideally integrated into a spiritually informed whole” (McNally 2005). For this reason, aboriginal traditions may be “better described as lifeways rather than as religions” (McNally 2000:849). Creedal concerns are usually not a focus, with adherents showing little interest in requiring individuals to acknowledge doctrinal statements.

Aboriginal practitioners have suffered a long history of restrictions at the hands of colonizers (Jennings 1975:3–14). Both historic criminalization of spiritual practice (Irwin 1997) and tribes’ forcible separation from sacred places (Jenkins 2004:44–45) have circumscribed aboriginal spiritual participation. Sociologists have nevertheless described a renascence of American Indian cultural identities since the 1960s—an “ethnic renewal” that has included reinvigoration of aboriginal traditions (Nagel 1996). Our own previous examination of AI-SUPERPFP data likewise found a great majority of repondents (86–91 percent) endorsing aboriginal beliefs as at least “somewhat important,” with half or more assigning them highest salience (Garroutte et al. 2009).

If prevalent salience suggests the continuing importance of aboriginal beliefs in American Indian communities today, it sheds no light on the extent to which belief translates into actual participation or for whom. What sociodemographic characteristics typify persons who constitute networks of religio-spiritual participation? And how, exactly, does belief relate to participation? Although the general American population consistently displays a pattern in which endorsement of beliefs outstrips all forms of religious participation (Gallup and Lindsay 1999; Hadaway and Marler 2005), is this equally true in aboriginal traditions? In view of the character of aboriginal spiritualties as lifeways rather than belief systems, might participation equal or even exceed professions of belief in this subpopulation?

Christianity

American Indians have been objects of Christian proselytization from the early period of European contact (Bowden 1981; Martin 2001). Spanish and French missionaries introduced Roman Catholicism in the 16th century, and the first Bible printed in America appeared in the Massachusett language in the 17th century (Cogley 1999). Subsequent American political and military ascendancy were accompanied by the growing influence of various Protestant groups. Beginning in the late 19th century, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS or Mormons) mounted missionary campaigns in many American Indian communities in the intermountain West (Topper 1979); conservative sects such as Pentecostals and Jehovah’s Witnesses added their efforts. Independent, evangelical Protestant congregations–often led by American Indian pastors–have emerged, more so in the Southwest (e.g., Aberle 1982; Steinmetz 1998).

National data from the ARIS showed a majority of its American Indian respondents (66 percent) identifying their religion as Christian. This identification was considerably less prevalent, however, than among non-Hispanic whites (79 percent) or African Americans (85 percent; Kosmin and Keysar 2006:253, 243). By contrast, our previous analysis of belief salience in the AI-SUPERPFP suggested a larger role for Christianity in the lives of its reservation-dwelling participants; it found 75–82 percent of men and women endorsing Christian beliefs as at least “somewhat important” (Garroutte et al. 2009).

These findings must be interpreted in view of substantial scholarship on American Indian Christianity. Such work argues that American Indian attitudes toward this introduced faith have often been characterized by a “pragmatic” orientation that relies upon the colonizers’ religion as a survival tool as much as a repository for personal conviction (e.g., Grant 1984; Rollings 2004). Such work makes the extent to which Christian identifications may reflect nominal engagement a matter for debate. Our examination will allow us to sketch a religious profile for the sampled American Indian Christians, while illuminating the extent to which belief profession corresponds with actual participation.

The NAC

Archeologists, historians, and anthropologists confirm religious borrowing and synthesis as important elements in American Indian spirituality before and after European contact (Brightman 1988). A prominent example of syncretic religions is the NAC or Peyote Way. Although its practices have roots in indigenous traditions that may go back 10,000 years in Mexico, peyote ceremonialism developed in distinctive ways in the 18th- and 19th-century United States. At the heart of this tradition is the all-night “meeting” in which a ceremonial leader or “road man” guides practitioners to approach the sacred by singing, drumming, praying, and ingesting peyote, a spineless cactus regarded as a sacrament. Although subtraditions within the NAC reflect Christian influences to varying degrees, frequent overlap of interpretations and symbols is accompanied by an expectation that practitioners will respect biblical teachings as they interpret them. Stewart (1987:65, 97) largely attributed the florescence of peyote traditions in 19th-century Indian territory to young students who returned home from Indian boarding schools with interest in combining the Christian religions that they encountered there with indigenous rituals and values.

Although NAC traditions typically urge members to abstain from alcohol and pursue values such as marital fidelity and truthfulness (Fikes 1996:173), 19th-century missionaries, educators, and governmental representatives suppressed peyote ceremonialism. The movement’s practices were criminalized in Indian territory in 1899; other states followed as the movement spread. Some peyotists sought legal protection in 1918 by incorporating themselves as the NAC (Fikes 1996:169). Although this move brought partial relief, religious rights of peyotists have varied, leaving them vulnerable to arrest and incarceration. It is only since 1994 that legislation has unequivocally guaranteed American Indian peyotists rights to practice their tradition.

Peyote ceremonialism is practiced today in most of America’s western states. Membership estimates, while incomplete, suggest about 200,000 to 250,000 adherents nationwide (Fikes 1996; Stewart 1987). Our previous examination of beliefs suggested that NAC adherents constitute a substantial subgroup in the sampled tribes, with more than two-thirds of participants endorsing its beliefs at some level, and from one-quarter to one-third describing those beliefs as “very important.” Neither extent of actual participation in the NAC nor its correlates have been examined in a large sample.

Method

We begin by describing prevalence of religio-spiritual participation in each of the three American Indian religio-spiritual traditions, stratifying the sample by tribal and gender groups. For each tradition, we then use multivariate models to identify correlates of participation, including sociodemographic and self-reported belief characteristics.

Study Design and Sample

The primary objective of the AI-SUPERPFP was to estimate prevalence of psychiatric disorders and health service utilization in three reservation populations; this survey also collected data about demographics and psychosocial constructs, including religious and spiritual participation. Tribes were chosen for size and specific characteristics. The Southwest tribe and the two closely affiliated Northern Plains reservations belong to different linguistic families, have different migration histories, embrace different principles for reckoning kinship and residence, and have historically pursued different forms of subsistence. Nevertheless, both share common experiences with other American Indian groups. They have similar histories of colonization—including dramatic military resistance, externally imposed forms of governance, and active missionary movements. Although based on different epistemologies, aboriginal belief systems are active in both tribes, with those in the Southwest particularly well articulated and preserved.

AI-SUPERPFP methods are described elsewhere (Beals et al. 2003). Populations of inference were citizens of the Northern Plains or the Southwest tribe. All were 15–54-years old when the sample frame was developed in 1997 and lived on, or within 20 miles of, their reservations. Each population was stratified by age and gender using stratified random sampling procedures (Cochran 1977) with tribal rolls, which are lists of all persons holding tribal citizenship as defined by law. Data were collected between 1997 and 1999; thus, some sample members had reached 57 years at time of interview, and fewer sample members were 15. A replicate strategy was used in which random groupings of names were released in sequence for location until the target sample size (about 1,500 per tribe) was reached. Overall, 39.5 percent and 46.5 percent of the Southwest and Northern Plains tribal members were found to be living on or near their reservations. Once located and found eligible, 73.7 percent agreed to participate from the Southwest (n = 1,446) and 76.8 percent from the Northern Plains (n = 1,638).

Instrumentation

The AI-SUPERPFP interview consisted of modules; those useful to this analysis asked about sociodemographics, religio-spiritual beliefs, and religio-spiritual participation. Tribal members conducted all interviews after intensive training. Informed consent was obtained from all participants; for minors, parental/guardian consent preceded adolescent assent. Tribal approvals were obtained before project implementation. Questions were administered using a computer-assisted personal interview. Extensive quality control procedures verified that all portions of location, recruitment, and interview procedures were conducted in a standardized, reliable manner.

Statistical Methods

All inferential analyses used sample and nonresponse weights (Cochran 1977) because of the complex sampling. Descriptive proportions and participation rates were compared across both tribe and gender. Given cultural and historical differences, the two tribes are best considered separate populations. Moreover, a significantly greater percentage of the Southwest sample was female than in the Northern Plains; review of location records indicated that migration of Southwest men to off-reservation communities for employment contributed substantially to the difference. The distinctive gender distributions recommended stratifying the analysis by gender as well as tribe. For descriptive statistics, 99 percent rather than 95 percent confidence intervals were calculated because of the substantial number of possible pair-wise comparisons. We assessed differences between proportions by observing whether confidence intervals overlapped. Multivariate logistic regression models (Long and Freese 2001) allowed us to investigate relationships between religio-spiritual participation and belief variables (salience, exclusivity) while controlling for sociodemographic characteristics (gender, tribe, education, age, marital status, children, employment).

Dependent Variables

Our project asked about prevalence and frequency of participation in specific religio-spiritual traditions. During instrument development, researchers sought assistance from focus groups conducted with each tribe. Several established scales such as the Midlife Development Inventory (MacArthur Foundation 2006), the Spiritual Well-Being Scale (Ellison and Smith 1991), and the Index of Core Spiritual Experiences (Kass et al. 1991) were reviewed in groups convened exclusively for adults, adolescents, and elders. A central focus group suggestion was that we inquire separately about aboriginal, Christian, and NAC traditions, customizing item structure and wording for each.

Aboriginal Participation

Because aboriginal traditions often incorporate collective ceremonial events specific to individual tribes, focus groups recommended a participation measure naming some of these in general terms. The resulting question asked: “How often do you participate in traditional [tribal name] practices such as healing ceremonies, religious events, or naming ceremonies?” (Never/Sometimes/Often).

Christian Participation

In view of the centrality of beliefs and church attendance for Christian traditions, focus groups helped us specify two questions to address Christian participation. These were: “How much do you practice or follow the beliefs of Christianity?” and “How often do you attend church services?” (Not at all/Some/A lot). Although the second question corresponds to the focus on church attendance characterizing much sociological research, data limitations—this question was not asked of those who reported following Christian traditions “not at all”—recommended its exclusion from our statistical models. We did report frequency data from the church attendance measure.

NAC Participation

Unlike Christian church services, NAC meetings are typically held on an as-needed basis, often to seek healing or mark events such as birthdays and funerals (Fikes 1996). The focus groups again recommended a question asking about participation only in general terms: “How much do you practice or follow the beliefs of the NAC?’ (Not at all/Some/A lot).

Sociodemographic Correlates

We measured sociodemographic factors beginning with participants’ tribe (Southwest/Northern Plains). Other variables, each reflecting dichotomized factors commonly related to religious participation in the general population, included age (<35 years/≥35 years), gender (male/female), full-time employment (yes/no), and education beyond grade 12 (yes/no). Additional variables reflected aspects of “family formation” that distinguished participants who were married/living as married (yes/no) and those reporting one or more children in the home (yes/no).

Belief Correlates

We incorporated a set of variables all related to participants’ religio-spiritual beliefs and all addressing factors commonly associated with religious participation in the general population. One group of items asked about belief salience; they distinguished participants within each of the three traditions who described its corresponding beliefs as “very important” (high salience) from those who did not (low salience). We also included a measure of exclusivity of belief that distinguished participants reporting that beliefs from any one tradition were “very important” from participants who endorsed beliefs from more than one tradition at this level.

Results

Sociodemographics

Sociodemographic characteristics of the sample appear in Table 1. Differences generally followed expected patterns. More Southwest than Northern Plains women were 35 years or older, whereas women in both tribes were more likely than their male counterparts to report higher education. Although about three-quarters of women in both tribes had at least one child at home, this was true for only about half the men. Full-time employment ranged between 30 percent and 44 percent. High belief salience was more common among Southwest women than among either men or women in the Northern Plains. Among Christians, 78–87 percent of participants reported church attendance. Only about one-third of participants reported belief in only one tradition.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of sample: percentages and 99 percent confidence intervals

| Southwest | Northern Plains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (n = 617) |

Women (n = 829) |

Men (n = 790) |

Women (n = 848) |

|

| Gender | 56.5 | 50.5 | ||

| Age 34 and under | 51.9 (49.5–54.2) |

50.2 (48.2–52.2)d |

51.7 (49.5–53.9) |

55.3 (53.1–57.4)b |

| Age 35 and over | 48.1 (45.8–50.5) |

49.8 (47.8–51.8)d |

48.3 (46.1–50.5) |

44.8 (42.6–46.9)b |

| High school or less | 77.4 (72.7–81.5)b |

66.9 (62.4–71.1)a,c |

78.9 (74.7–82.6)b,d |

69.7 (65.2–73.8)c |

| Some college or more | 22.6 (18.5–27.3)b |

33.1 (28.9–37.6)a,c |

21.1 (17.4–25.3)b,d |

30.3 (26.2–34.8)c |

| Married | 57.5 (52.4–62.4) |

62.2 (57.8–66.4)c |

49.0 (44.2–53.8)b |

53.7 (49.1–58.2) |

| Not married | 42.5 (37.6–47.6) |

37.8 (33.6–42.2)c |

51.0 (46.2–55.8)b |

46.3 (41.8–50.9) |

| Child(ren) in home | 52.0 (47.1–56.9)b,d |

75.9 (72.3–79.2)a,c |

45.8 (41.1–50.6)b,d |

73.9 (69.9–77.5)a,c |

| No children in home | 48.0 (43.1–52.9)b,d |

24.1 (20.8–27.7)a,c |

54.2 (49.4–58.9)b,d |

26.1 (22.5–30.1)a,c |

| Full-time employee | 39.5 (34.6–44.7) |

43.6 (39.3–48.0)c |

30.5 (26.2–35.2)b |

34.8 (30.5–39.3) |

| Part-time, unemployed, student, retired | 60.5 (55.4–65.4) |

56.4 (52.0–60.7)c |

69.5 (64.8–73.8)b |

65.2 (60.7–69.5) |

| High belief saliencee | 72.0 (66.8, 76.6) |

76.6 (72.2, 80.4)c,d |

62.4 (57.6, 67.0)b |

64.7 (60.1, 69.1)b |

| Low belief saliencee | 28.0 (23.4, 33.2) |

23.4 (19.6, 27.8)c,d |

37.6 (33.0, 42.4)b |

35.3 (30.9, 39.9)b |

| Attends churchf | 77.9 (71.8–82.9) |

81.7 (77.0–85.7) |

83.3 (78.4–87.3) |

87.1 (82.8–90.5) |

| Does not attend churchf | 22.1 (17.1–28.2) |

18.3 (14.3–23.0) |

16.7 (12.8–21.6) |

12.9 (9.5–17.2) |

| Exclusive to one belief | 34.7 (29.6–40.1) |

36.0 (31.5–40.7) |

33.3 (28.7–38.2) |

36.4 (31.9–41.2) |

| Not exclusive to one belief | 65.3 (59.9–70.4) |

64.0 (59.3–68.5) |

66.7 (61.8–71.3) |

63.6 (58.8–68.1) |

Significantly different from Southwest men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Southwest women, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains women, p < .01.

High belief salience indicates “very important” beliefs for at least one of three traditions (Aboriginal, NAC, Christian).

Asked only of those who practice Christianity.

Prevalence of Religio-Spiritual Participation

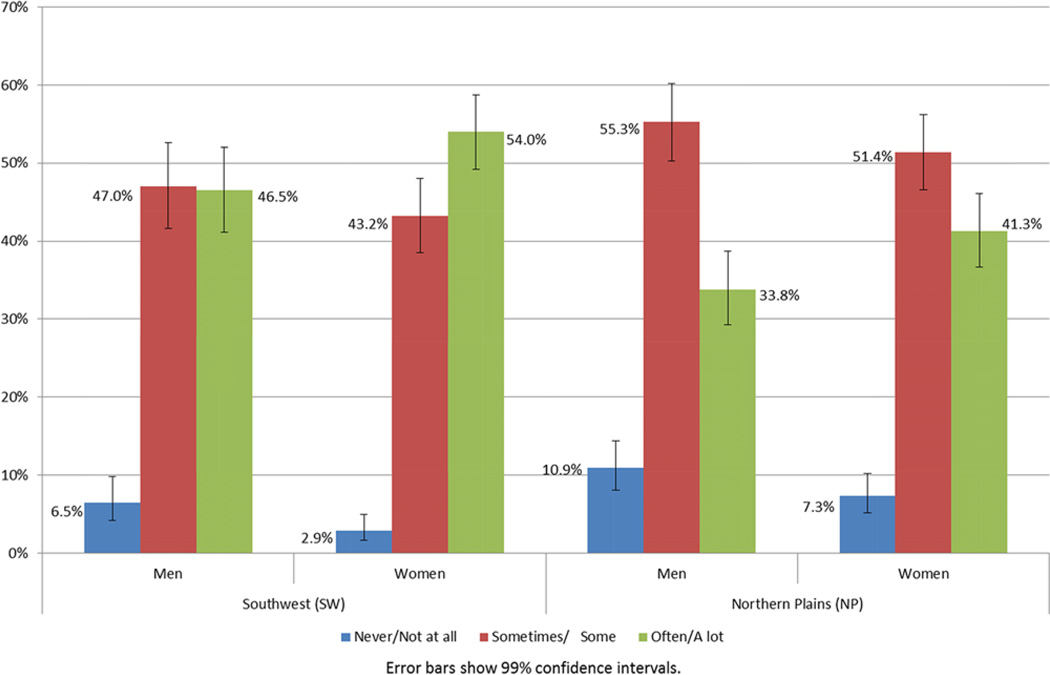

Table 2 presents overall participation rates, focusing on the tradition each participant practiced most often. Few reported never participating, with rates ranging from 3 percent to 11 percent. Approximately half of participants in both tribes reported an intermediate level of religio-spiritual participation, whereas about one-third to over one-half participated at the highest level (Often/A lot) in at least one tradition. No significant differences emerged between men and women within tribes, whereas some cross-tribal differences appeared; for example, Southwest men participated at the highest level significantly more often than Northern Plains men, and Southwest women participated at this level significantly more often than did men or women in the Northern Plains. The figure graphically summarizes information from Table 2. It underscores uniformly low levels of nonparticipation across groups, greater prevalence of participation in the Southwest in general, and particularly high prevalence of participation among Southwest women.

Table 2.

Highest level of participation for any of the three traditions: percentages and 99 percent confidence intervalsa

| Southwest | Northern Plains | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Never/not at all | 6.5 (4.2, 9.8) |

2.9 (1.7, 5.0)d,e |

10.9 (8.1, 14.4)c |

7.3 (5.2, 10.2)c |

| Sometimes/some | 47.0 (41.6, 52.6) |

43.2 (38.5, 48.0)d |

55.3 (50.3, 60.2)c |

51.4 (46.6, 56.2) |

| Often/a lot | 46.5 (41.1, 52.0)d |

54.0 (49.2, 58.7)d,e |

33.8 (29.3, 38.7)b,c |

41.3 (36.7, 46.1)c |

Calculated by assigning the maximum value across the three traditions. To be assigned a value of Never/not at all, the participant indicated this answer for all three traditions; on the other hand, to be assigned to Often/a lot, the participant chose this response for at least one of the traditions.

Significantly different from Southwest men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Southwest women, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains women, p < .01.

Table 3 summarizes data on participation in specific traditions. About 20 percent of participants in all subgroups participated in aboriginal spirituality often, while 13–29 percent participated in Christianity at the same level. Only about one-third of participants reported no participation in aboriginal spirituality, while one-quarter to one-third reported no participation in Christianity; the typical level of participation in both traditions was “sometimes.” Finally, 8–19 percent participated “a lot” in NAC, whereas about half indicated no participation.

Table 3.

Frequency of particular religious participation: percentages and 99 percent confidence intervals

| Tradition | Frequency of Participation |

Southwest | Northern Plains | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | ||

| Aboriginal | Never/not at all | 31.5 (26.6, 36.8) |

31.1 (26.9, 35.7) |

34.0 (29.5, 38.9) |

37.3 (32.9, 42.1) |

| Sometimes/some | 47.3 (41.8, 52.8) |

48.0 (43.3, 52.8) |

45.8 (40.8, 50.9) |

39.8 (35.3, 44.6) |

|

| Often/a lot | 21.3 (17.1, 26.1) |

20.9 (17.2, 25.0) |

20.2 (16.5, 24.5) |

22.9 (19.0, 27.2) |

|

| Christian | Never/not at all | 32.2 (27.4, 37.5) |

26.6 (22.7, 31.0) |

30.3 (25.9, 35.0) |

27.0 (22.9, 31.4) |

| Sometimes/some | 47.9 (42.4, 53.4) |

44.4 (39.7, 49.2)c |

56.4 (51.5, 61.3)b |

50.8 (46.0, 55.6) |

|

| Often/a lot | 19.9 (15.9, 24.7)b |

29.0 (24.9, 33.5)a,c |

13.3 (10.3, 17.0)b,d |

22.3 (18.5, 26.6)c |

|

| NAC | Never/not at all | 44.9 (39.5, 50.4) |

45.1 (40.4, 49.9)d |

50.7 (45.7, 55.8) |

55.2 (50.4, 60.0)b |

| Sometimes/some | 37.2 (32.0, 42.7) |

35.6 (31.2, 40.3) |

39.2 (34.4, 44.3) |

37.2 (32.7, 42.0) |

|

| Often/a lot | 17.9 (14.1, 22.6)c,d |

19.3 (15.8, 23.3)c,d |

10.1 (7.4, 13.6)a,b |

7.6 (5.4, 10.6)a,b |

|

Significantly different from Southwest men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Southwest women, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains men, p < .01.

Significantly different from Northern Plains women, p < .01.

No differences in aboriginal participation emerged across tribe-by-gender subgroups. By contrast, level of participation within Christianity and NAC did vary significantly. Within each tribe, women were significantly more likely to report the highest level of Christian participation (22–29 percent) as compared to male counterparts (13–20 percent), whereas frequent participation in NAC at the highest level was significantly more common in the Southwest (17–19 percent).

Other calculations (not shown) assessed religio-spiritual exclusivity by examining extent to which participants “often” participated in more than one tradition. Such overlap was relatively rare, characterizing about 9 percent of frequent practitioners in the Northern Plains and 12 percent in the Southwest. Only 2 percent of either tribe participated in all three traditions at the highest level.

Table 4 presents crude and adjusted odds ratios comparing persons who participate in each tradition “sometimes” or “often” (both coded as 1) as compared to “never” (coded as 0). Of sociodemographic variables, few were significantly associated with participation in particular traditions, none consistently. Participation in aboriginal traditions was correlated with tribe and education. Those in the Northern Plains had lower odds of participation than the Southwest tribe, whereas those with at least a high school education had significantly higher odds of participation compared to those who did not graduate; these relationships remained after adjusting for other variables. For participation in Christianity, however, crude and adjusted odds ratios differed. Unadjusted models indicated those practicing Christianity were more likely to be women, older, married, to have children at home, and to be employed. By contrast, significant adjusted odds ratios were restricted to being from the Northern Plains and being 35 years or older. Participation in NAC was related to Southwest tribe, younger age, and being less than fully employed; with adjustment, only younger age remained significant.

Table 4.

Correlates of participation: results of logistic regression analyses

| Sometimes/Often Versus Never (Referent) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tradition | Crudea Odds Ratio |

Sig. | Adjustedb Odds Ratio |

Sig. | |

| Aboriginal (n = 2,786) | Men | 1.06 | 1.08 | ||

| Northern Plains | .82 | * | .78 | ** | |

| At least high school education | 1.45 | ** | 1.35 | ** | |

| Age 35+ | 1.14 | 1.08 | |||

| Married or cohabiting | 1.10 | 1.03 | |||

| Children living at home | 1.10 | 1.15 | |||

| Employed full time | 1.05 | .90 | |||

| High aboriginal belief saliencec | 7.76 | ** | 9.05 | ** | |

| Exclusivity of beliefs (aboriginal, Christian, or NAC)d | .85 | .53 | ** | ||

| Christian (n = 2,779) | Men | .81 | * | .90 | |

| Northern Plains | 1.02 | 1.27 | * | ||

| At least high school education | 1.18 | .91 | |||

| Age 35+ | 2.20 | ** | 1.81 | ** | |

| Married or cohabiting | 1.27 | ** | 1.07 | ||

| Children living at home | 1.38 | ** | 1.08 | ||

| Employed full time | 1.43 | ** | 1.17 | ||

| High Christian belief saliencec | 19.39 | ** | 18.30 | ** | |

| Exclusivity of beliefs (Aboriginal, Christian or NAC)d | 1.23 | * | 1.00 | ||

| Native American Church (n = 2,748) | Men | 1.09 | 1.04 | ||

| Northern Plains | .73 | ** | .87 | ||

| At least high school education | .89 | .87 | |||

| Age 35+ | .80 | ** | .73 | ** | |

| Married or cohabiting | 1.04 | 1.19 | |||

| Children living at home | .88 | .85 | |||

| Employed full time | .81 | ** | .89 | ||

| High NAC belief saliencec | 16.00 | ** | 15.89 | ** | |

| Exclusivity of beliefs (Aboriginal, Christian or NAC)d | .36 | ** | .95 | ||

Note:

p < .05;

p < .01.

Odds ratios for bivariate logistic regression models.

Odds ratios for full logistic regression models (all variables for a specific tradition, as seen above, are included in each model).

High belief salience indicates “very important” beliefs for that particular tradition.

Exclusivity of beliefs indicates “very important” belief in one and only one of either Aboriginal, Christian, or Native American Church.

In contrast with the varying patterns of demographic correlates, belief salience showed strong and consistent relationships to participation across all traditions. Adjusting for other variables, participants endorsing aboriginal belief as “very important” had nine times higher odds of participation in that tradition as compared to all others (OR = 9.05; p < .01). The pattern for Christian beliefs was even more pronounced—more than 18 times higher among those endorsing the corresponding beliefs as highly salient (OR = 18.30; p < .01). The relationship for NAC beliefs was not far behind, with odds about 16 times higher among those for whom those beliefs were strongly salient (OR = 15.89; p < .01).

Finally, exclusivity of belief, a variable distinguishing participants reporting only one tradition as “very important,” was significant among crude odds ratios for Christian and NAC beliefs. However, after controlling for other variables, this was significant only for aboriginal traditions, in which persons embracing exclusive beliefs had significantly lower odds of participation (OR = .53; p < .01).

Discussion

We examined prevalence and correlates of participation in three religio-spiritual traditions in two American Indian tribes. Our most general finding revealed three active, but not extensively overlapping, networks of participation. The great majority of participants in tribe-by-gender subgroups—from 89 percent of Northern Plains men to 97 percent of Southwest women— reported participating in at least one tradition at least “sometimes,” with about one-third to half of participants participating “often.” Our adaptation of conventional participation measures to reflect the structure of American Indian spiritual practice makes comparison to data on religious participation in the general American population challenging. Nevertheless, the small percentages in our sample who indicated that they never participated in any religio-spiritual tradition—only 3–11 percent—appears strikingly small relative to the 44 percent of “unchurched” Americans indicated by national polls. Gallup polls consider individuals “unchurched” if they belong to no congregation or report attending religious services only for events such as weddings (Gallup and Lindsay 1999).

Patterns of Participation by Religio-Spiritual Tradition: Sociodemographic Correlates

Our analyses also revealed patterns of participation specific to particular religio-spiritual traditions. We discuss these findings under separate headings, turning first to sociodemographic variables.

Aboriginal Participation and Sociodemographic Correlates

About two-thirds of participants in both tribes reported participating in aboriginal traditions at least sometimes, with about 20 percent participating often/a lot. Both figures suggest that networks of participation associated with historic religio-spiritual traditions remain active in contemporary American Indian communities. Multivariate analyses revealed some small but statistically significant sociodemographic correlates of participation.

The first of these correlates was tribe, with participation in aboriginal traditions being more common in the Southwest. This might reflect the more structured nature of Southwestern traditions as compared to more individually variable orientations among Northern Plains traditions, which can be highly personal and linked to individual vision experiences (Gill 1982:163; Irwin 1994). Education also emerged as a small yet significant sociodemographic correlate of aboriginal participation; participants with at least high school education had odds of participation about one-third times higher than those with less formal education. This finding adds to a body of research in the general population that has identified associations between education and religious participation, although the direction of relationship is inconsistent. On the one hand, considerable sociological work has associated higher education with decreased religious participation (e.g., Hunter 1983; Sherkat 1998). Other work, including an extraordinary analysis of multiple, large datasets on African Americans (Chatters, Taylor, and Lincoln 1999) and a large study of Mormons (Albrecht and Heaton 1984) has found positive relationships (cf. Kosmin and Keysar 2006; Uecker, Regnerus, and Vaaler 2007).

Such inconsistent findings relating education and participation raise the theoretical possibility that associations vary across specific religious traditions, racial groups, and cultural contexts. Our identification of a positive relationship for aboriginal traditions also articulates interestingly with research proposing that the experiences of ethnic minorities in assimilating contexts, including educational institutions, ironically provides tools whereby they recognize differences between cultures of origin and the dominant culture, thus enhancing the ability to embrace their own lifeways (Xie and Goyette 1997). This “awareness hypothesis” might explain the association of higher education with aboriginal participation as reflecting a movement in which those who leave tribal communities for educational or professional purposes return home with enhanced motivation toward hereditary spirituality (cf. Nagel 1996).

Christian Participation and Sociodemographic Correlates

Almost three-quarters of participants in tribe-by-gender subgroups participated in Christian traditions at least sometimes, with 13–29 percent participating at the highest level. Odds of participating in Christianity “a lot” were comparable to or larger than those for any other tradition—a finding that discourages any conclusion that this tradition commands merely nominal adherence among American Indians. Multivariate analyses revealed that odds of Christian participation were significantly higher in the Northern Plains than in the Southwest. This difference might reflect tribal differences in the penetration of the Christian faith in different communities, or perhaps denominational differences. In particular, Catholicism is the more pervasive form of Christianity in the Northern Plains, and it has commanded lower attendance than in other Christian denominations in recent decades (Pew Forum 2008).

Christian involvement also varied with age; persons 35 years and older had significantly greater odds of participation as compared to younger counterparts. Such relationships might suggest a cohort effect whereby Christian influences is waning in Indian communities as older believers are not replaced by younger ones. Alternatively, they might reflect a trend, likewise observed in the general population, for people to become more involved in this faith as they age (Hout and Greeley 1987).

One theoretical explanation for the positive relationship between religious participation and age in the general population describes participation as characteristic of periods in the life cycle when diminishing commitments to career, child care, and similar responsibilities free up time for religious activities (Hout and Greeley 1987). If this explanation fit our data, however, one would expect it to appear for all traditions, not only for Christianity. It is plausible that the significance of older age for Christian participation, taken together with its insignificance for aboriginal and NAC participation, might reflect differing cultural dispositions toward the afterlife. As Gill observes, Western Christianity tends to view this world as “a temporary and preparatory existence in which one looks forward to a life after death,” whereas tribal spiritualities more likely “regard death in old age as the culmination and fulfillment of a life well lived” (2002:104). Such distinct orientations might motivate an intensification of religious participation in Christians for whom the anticipated afterlife draws closer, even as they are less likely to do so for tribal traditions that encourage living appropriately at every life stage. Only further research can clarify this interpretation.

One of our most interesting findings concerned gender and participation. Since the earliest years of sociological inquiry, researchers have found that women outstrip men on religiosity measures (reviews in Beit-Hallahmi and Argyle 1997; Gallup 2002; for exceptions, see Sullins 2006). Most sociological explanations for these relationships emphasize contributors such as male and female structural locations (Cornwall 1989; de Vaus and McAllister 1987), gender orientation (Sherkat 2002; Thompson and Remmes 2002), and gender role socialization (Levitt 1995).

By contrast, some relatively recent and widely cited analyses have discarded social variables, instead attributing female bias in religion to sex-linked physiological characteristics—especially relative aversion to risk. They propose that physiological predispositions make females less likely than males to hazard losing supernatural rewards through irreligiousness (Miller and Stark 2002; Stark 2002). Even more recent work has countered this “premature concession to biology” with efforts to preserve socialization explanations. This latter view accepts gendered differences in risk aversion and implications for religiosity and even allows some role for biological influences. At the same time, it argues an additional role for parental tendencies—especially of mothers in “patriarchal” households—to socialize male and female children differently. Males, in this view, are trained from childhood to tolerate more risk than females, with consequences for adult religious responses. An analysis of pooled data from the 1994 to 2004 General Social Surveys was consistent with hypotheses corresponding to this perspective. It found smaller male-female differences in religiosity between children raised in more “egalitarian” households comprising mothers and fathers of similar socioeconomic status than in “patriarchal” households characterized by greater paternal advantage (Collett and Lizardo 2009; cf. Lizardo and Collett 2009).

Our findings raise intriguing ideas in context of unresolved debates about how biological and social variables influence belief and behavior. Notably, our logistic regressions showed that odds of frequent religio-spiritual participation were no different for women and men within any tradition examined. This finding discourages researchers from uncritically generalizing familiar gender patterns across America’s racial-ethnic subgroups. Consistent with a role for gender socialization, it also suggests further questions. Collett and Lizardo (2009) predict greater differences in children’s gender socialization in “patriarchal households,” which they operationalize in terms of differences between parents’ socioeconomic statuses. Is it important that women in our sample typically equal or exceed men in both education and full-time employment? Might this mean that American Indian households in our sample were unusually egalitarian in their socialization of male and female children, with consequences for religio-spiritual behavior? Might specific cultural variables, such as tendencies to associate maleness and femaleness with unique relationships to the sacred (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992), also have helped to erase the gender gap in participation? Data collected from American Indians may provide researchers with extraordinary opportunities to approach such questions.

NAC Participation and Sociodemographic Correlates

Although rates of participation in NAC were lower than in the other traditions, about half of all participants in both tribes reported participating at least sometimes, with up to 19 percent participating often. Such figures suggest religio-spiritual practices within the experience of substantial numbers of tribal people. The higher rates of frequent NAC participation in the Southwest that appeared in tribe-by-gender analyses confirm other observations (e.g., Mead, Hill, and Atwood 2005:242) and are consistent with the southwestern origins of peyote ceremonialism. Surprisingly, these differences disappeared in multivariate models, where younger age was the only significant sociodemographic correlate.

The association of peyote participation with younger age recalls historian Omer Stewart’s remarks regarding the appeal of peyotism for Indian youth whose training in 19th-century boarding schools predisposed them to religio-spiritual practice that combined Christian and indigenous elements. Our finding raises the possibility that NAC traditions may serve a similar, spiritually integrative purpose for American Indian adolescents and young adults today, assisting them in negotiating a life stage that social scientists have viewed as especially concerned with (re)defining spiritual commitments (Gollnick 2005).

Patterns of Participation by Religio-Spiritual Tradition: Belief Correlates

If significant associations between participation and sociodemographic variables were provocative, they were small and typically unique to particular traditions. The same was true for the belief variable that we labeled exclusivity. Our previous analysis of AI-SUPERPFP data revealed that exclusivity of belief was uncommon; one-third to one-half of individuals who endorsed some religio-spiritual beliefs as “very important” also assigned that level of salience to beliefs from more than one tradition (Garroutte et al. 2009). Nevertheless, in the current analysis, exclusivity of participation achieved significance in adjusted models only for aboriginal traditions. Here a modest association emerged between exclusivity and less frequent participation. This association perhaps reflects the ecumenism of aboriginal traditions, which may encourage participants to seek spiritual wisdom from diverse sources (Beck, Walters, and Francisco 1992).

By contrast with modest associations generated by sociodemographic and exclusivity variables, measures of belief salience were extremely strong correlates of participation across all traditions. Odds of aboriginal participation were nine times higher for persons who endorsed corresponding beliefs as “very important” as compared to all other participants, odds of Christian participation were 18 times higher, and odds of NAC participation were 16 times higher.

The strikingly large association with belief salience for Christian participation may reflect the extent to which Christianity has been presented to American Indian people specifically as a belief system, meaning a set of propositions to be endorsed (McNally 2000). The smaller yet still impressive relationship of beliefs to participation for aboriginal adherents is consistent with the interpretation that doctrinal formulations occupy a less central place in these traditions than in Christianity. At the same time, it suggests that aboriginal practitioners found questions about their beliefs intelligible and that they connected professions with behavior. Supposing that the varying size of associations between belief salience and participation reflects the relative emphasis that different traditions place on creedalism, the intermediate strength of the association for NAC is unsurprising. As the tradition that melds influences from aboriginal and Christian sources, one might expect that it would show—as it does—a corresponding, intermediate relationship of belief salience to participation.

Comparison between our previous analysis (Garroutte et al. 2009) and current findings reveals that more participants reported that religio-spiritual beliefs were important to them (97–99 percent) than actually participated in a tradition (89–97 percent). Nevertheless, both estimates are consistent with a population wherein professed belief commonly translates into behavior in every tradition. This correspondence is noteworthy when compared to national opinion polls in which 60 percent of all Americans describe religion as “very important in their lives” but only 44 percent—perhaps half that number in corrected estimates—attend services (Gallup and Lindsay 1999; Hadaway and Marler 2005).

An American Indian Religious Profile?

Our findings contribute to efforts at building an American Indian religious profile grounded in statistical data. Results are consistent with robust participation within aboriginal traditions, while simultaneously arguing against nominal commitment to Christianity. They also illuminate the extent to which the NAC represents an important aspect of religio-spiritual participation in tribal communities. Conversely, our data show only small numbers of people—from 3 to 11 percent in particular tribe-by-gender subgroups—reporting no religious participation.

Such conclusions depart notably from the religious profile suggested by the ARIS, a national survey reporting religious data from a substantial number of American Indian households (Kosmin and Keysar 2006). Conducted about the same time as the data collection for the current project, the ARIS suggested relatively modest religious expression among American Indians. Its participants endorsed Christianity at a substantially lower rate as compared to the general population. Moreover, with only 6 percent identifying with “Other Religions”—a category that included tribal traditions along with various small groups—adherence to aboriginal practices appeared negligible. Indeed, the feature that ARIS researchers identified as especially distinguishing its American Indian religious profile was a significantly greater tendency to report having “no religion” as compared to African, Hispanic, or white Americans.

Several factors may have contributed to the starkly different religious profiles emerging from the ARIS and from our own analysis of AI-SUPERPFP data. One involves instrumentation. Given the typically close interrelationship of spirituality with other aspects of tribal cultures, American Indian participants may have been reluctant to distinguish and classify some spiritual practices as defining their “religion,” as the wording of ARIS items required. Such reluctance could explain the large number of American Indians who claimed “no religion” on that survey (19 percent).

Differences in sampling procedures may have contributed even more significantly to variant findings. As a telephone interview using a sampling scheme based on the largely urban/suburban distribution of the U.S. population, the ARIS might be expected to be highly biased for reservation-based American Indians, who commonly reside in rural areas and frequently lack telephone service (Sandefur, Rindfuss, and Cohen 1996). As a national survey, the ARIS also presumably included individuals from many tribes, as compared to our more targeted sample. Most important, ARIS’s reliance upon participants’ racial self-definition as American Indians may have captured persons without the social, cultural, and political ties characterizing the reservation-based, tribal citizens in the two tribes sampled by the AI-SUPERPFP (Garroutte 2003; Snipp 1989). Given the role of reservations as repositories of cultural knowledge, one might expect their residents to exhibit distinctive patterns of religio-spiritual behavior—including the high prevalence of participation in tribal traditions and NAC that we observed.

The religious profile that emerges from our analysis promises practical implications in such areas as the design of health promotion messages. It suggests, for example, that messages incorporating culturally appropriate religio-spiritual components would be widely acceptable in the sampled populations. Nevertheless, comparison across the differently constructed samples of American Indians just described—the ARIS and the AI-SUPERPFP—draws attention to challenges that attend efforts to construct a single religious profile for this special subpopulation. They recommend that future efforts consider special sampling issues and examine subethnic differences within the American Indian racial category.

Networks of Religio-Spiritual Participation

Partnerships wherein academic researchers collaborate with minority communities have met challenges threatening vulnerable populations. Many have involved efforts to reduce racial-ethnic health disparities by drawing on networks associated with faith-based institutions, especially African-American and sometimes Latino churches (review in Campbell et al. 2007). Such projects have involved interventions relevant to conditions including cancer (Demark-Wahnefried et al. 2000), substance abuse (MacMaster et al. 2007), and HIV/AIDS (Michael et al. 2008; review in Francis and Liverpool 2009).

Although community-based research collaborations serving public health goals are on the rise in Indian country (e.g., Goins et al. 2011), such efforts have seldom, if ever, engaged tribal networks of religio-spiritual participation. Our findings of widespread religio-spiritual activity among sampled American Indians suggest that neglecting corresponding networks of researchers in public health, social work, and related fields overlooks a form of social capital in which tribal communities are rich. We look forward to future work testing the ways such networks might be harnessed in service of community-defined goals, such as mental and physical health promotion. The same findings offer guidance for such efforts. Specifically, our results suggest that researchers working with the large communities sampled for this project can expect strong correspondence between professed belief salience and actual participation in every religio-spiritual tradition. Aboriginal networks are likely extensive and sociodemographically diverse, encompassing strong representation across groups defined by gender, age, employment status, and family type; they may be especially effective for reaching southwestern tribal members and individuals with higher education. That the majority of our participants in both tribes reported Christian participation suggests that collaborations with church networks in these communities may likewise prove worthwhile, perhaps being especially well received in the Northern Plains and among older adults. Efforts to engage networks related to NAC participation might be expected to reach smaller, yet still substantial and sociodemographically diverse, audiences; they may have special relevance to younger persons. That individuals in our sample typically participated regularly in only one tradition suggests that community-based researchers should consider incorporating multiple networks.

Limitations

Interpretation of findings must occur in context of project limitations. Although our sample of more than 3,000 American Indian participants is large compared to other datasets, restriction of sampling to just two of the country’s diverse tribes implies that generalization must proceed cautiously; even investigations in urban Indian populations of the same tribes may reveal different patterns than our rural, reservation sample. Although our models examined many variables commonly associated with religious participation, our cross-sectional data cannot establish causation or directionality of relationship; we cannot conclude, for instance, that high belief salience stimulated regular participation or the reverse. Additional, unmeasured variables—perhaps community relationships or religious socialization—might also have influenced outcomes (e.g., Cornwall 1989).

Our specific participation measures imply other limitations. Like the majority of empirical work in the sociology of religion, we examined individual-level measures of religio-spiritual participation. This focus disallows conclusions about the influence of meso- and macro-level variables, such as variations in the differentiation of religio-spiritual institutions or in the “supply” of religio-spiritual “products,” meaning opportunities to engage in specific types of spiritual practice. In a related vein, our measure of Christian participation did not differentiate denominations; we urge future researchers to examine social networks specific to particular denominations and to separately assess their impact on tribal communities. We relied upon self-report—a method for measuring participation that may invite overestimation; if individuals overreported participation, its association with significant correlates could be exaggerated. Finally, our need to tailor measures to religio-spiritual traditions not oriented to the regularly scheduled observances common to Christian traditions problematized comparison to national data, which commonly assesses participation by weekly religious attendance.

Conclusion

This analysis described religio-spiritual participation using survey data from a large, exclusively American Indian sample. Variables associated with participation differed across specific traditions and from those observed in the general population. Patterns of demographic variables suggest a distinctive “religious profile” for this American Indian sample and discourage researchers from assuming that relationships reliably characterizing the general American population—notably associations of participation with older age and female gender—apply equally in tribal subpopulations. The high odds of religio-spiritual participation in both tribes recommend that American Indian communities might profitably draw on social networks associated with aboriginal, Christian, and NAC participation to assist the goals of community-based research projects.

Figure 1.

Highest level of participation for any of the three traditionsa

a Calculated by assigning the maximum value across the 3 traditions.

Acknowledgments

The authors also would like to acknowledge the contributions of the Methods Advisory Group: Margarita Alegria, Evelyn J. Bromet, Dedra Buchwald, Peter Guarnaccia, Steven G. Heeringa, Ronald Kessler, R. Jay Turner, and William A. Vega. Finally, they thank the tribal members who so generously answered all the questions asked of them.

Design, conduct of study, data collection, and original data management and analyses were supported by NIH grants MH48174 (S. M. Manson and J. Beals, PIs) and MH42473 (S. M. Manson, PI). Data analyses and interpretation specific to this article, as well as preparation, review, and approval, were supported by 1K01 AG022434-01A2 (E. M. Garroutte, PI) and R01 MH073965 (J. Beals, PI).

Footnotes

AI-SUPERPFP would not have been possible without the significant contributions of many people. The following interviewers, computer/data management, and administrative staff supplied energy and enthusiasm for an often difficult job: Anna E. Barόn, Antonita Begay, Amelia T. Begay, Cathy A. E. Bell, Phyllis Brewer, Nelson Chee, Mary Cook, Helen J. Curley, Mary C. Davenport, Rhonda Wiegman Dick, Marvine D. Douville, Pearl Dull Knife, Geneva Emhoolah, Fay Flame, Roslyn Green, Billie K. Greene, Jack Herman, Tamara Holmes, Shelly Hubing, Cameron R. Joe, Louise F. Joe, Cheryl L. Martin, Jeff Miller, Robert H. Moran Jr., Natalie K. Murphy, Melissa Nixon, Ralph L. Roanhorse, Margo Schwab, Jennifer Settlemire, Donna M. Shangreaux, Matilda J. Shorty, Selena S. S. Simmons, Wileen Smith, Tina Standing Soldier, Jennifer Truel, Lori Trullinger, Arnold Tsinajinnie, Jennifer M. Warren, Intriga Wounded Head, Theresa (Dawn) Wright, Jenny J. Yazzie, and Sheila A. Young.

We use religion to describe formally organized, creedal faiths such as Christianity. We use spirituality to describe indigenous traditions that share a focus on the sacred but involve less organized ritual and collective validation. We employ the term religio-spiritual to encompass both. All these usages correspond to our earlier publication (Garroutte et al. 2009) that characterized patterns of beliefs in the same sample wherein we now examined patterns of religiospiritual participation. While each of these terms has received scrutiny in the scholarly literature, they result from extensive negotiations with out tribal partners. The choices reflect to a commitment to honor our partners’ legitimate concerns that categories applied to them correspond to their own understandings. For a discussion of the tribal consultation process, see Beals and colleagues (2003).

Contributor Information

Eva Marie Garroutte, Department of Sociology, Boston College.

Heather Orton Anderson, Department of Epidemiology, University of Colorado Denver.

Patricia Nez-Henderson, Black Hills Center for American Indian Health.

Calvin Croy, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, University of Colorado Denver.

Janette Beals, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, University of Colorado Denver.

Jeffrey A. Henderson, Black Hills Center for American Indian Health

Jacob Thomas, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, University of Colorado Denver.

Spero M. Manson, Centers for American Indian and Alaska Native Health, University of Colorado Denver

References

- Aberle David F. The future of Navajo religion. In: Brugge David M, Frisbie Charlotte J., editors. Navajo religion and culture—Selected views: Papers in honor of Leland C. Wyman. Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico; 1982. pp. 219–231. [Google Scholar]

- Albrecht Stan L, Heaton Tim B. Secularization, higher education, and religiosity. Review of Religious Research. 1984;26(1):43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Beals Janette, Manson Spero M, Mitchell Christina M, Spicer Paul and the AI-SUPERPFP Team. Cultural specificity and comparison in psychiatric epidemiology: Walking the tightrope in American Indian research. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry. 2003;27(3):259–289. doi: 10.1023/a:1025347130953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck Peggy V, Walters Anna Lee, Francisco Nia. The sacred: Ways of knowledge, sources of life. Tsaile, AZ: Navajo Community College; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Beit-Hallahmi Benjamin, Argyle Michael. The psychology of religious behaviour, belief and experience. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden Henry Warner. American Indians and Christian missions: Studies in cultural conflict. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Brightman Robert A. Toward a history of religious change in native societies. In: Calloway Colin G., editor. New directions in American Indian history. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1988. pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell Marci K, Hudson Marlyn A, Resnicow Ken, Blakeney Natasha, Paxton Amy, Baskin Monica. Church-based health promotion interventions: Evidence and lessons learned. Annual Review of Public Health. 2007;28(1):213–234. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.021406.144016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatters Linda M, Taylor Robert Joseph, Lincoln Karen D. African American religious participation: A multi-sample comparison. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1999;38(1):132–145. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran William G. Sampling techniques. New York: Wiley; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Cogley Richard W. John Eliot’s mission to the Indians before King Philip’s war. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Collett Jessica L, Lizardo Omar. A power-control theory of gender and religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(2):213–231. [Google Scholar]

- Cornwall Marie. The determinants of religious behavior: A theoretical model and empirical test. Social Forces. 1989;68(2):572–592. [Google Scholar]

- Demark-Wahnefried Wendy, McClelland Jacquelyn W, Jackson Bethany, Campbell Marci K, Cowan Arnette, Hoben Kimberly, Rimer Barbara K. Partnering with African American churches to achieve better health: Lessons learned during the Black Churches United for Better Health 5 a Day Project. Journal of Cancer Education. 2000;15(3):164–167. doi: 10.1080/08858190009528686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vaus David, Mcallister Ian. Gender differences in religion: A test of the structural location theory. American Sociological Review. 1987;52(4):472–481. [Google Scholar]

- Ellison Craig W, Smith Joel. Toward an integrative measure of health and well-being. Journal of Psychology and Theology. 1991;19(1):35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Fikes Jay C. One nation under God: The triumph of the Native American Church, edited by Huston Smith and Reuben Snake. Santa Fe: Clear Light; 1996. A brief history of the Native American Church; pp. 167–173. [Google Scholar]

- Finke Roger, Stark Rodney. The churching of America, 1776–2005: Winners and losers in our religious economy. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Francis Shelley A, Liverpool Joan. A review of faith-based HIV prevention programs. Journal of Religion and Health. 2009;48(1):6–15. doi: 10.1007/s10943-008-9171-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallup George., Jr Why are women more religious? Gallup Poll Tuesday briefing: Religion and values. 2002 Available at http://www.gallup.com/poll/7432/Why-Women-More-Religious.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup George, Jr, Lindsay D Michael. Surveying the religious landscape: Trends in U.S. beliefs. Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte Eva Marie. Real Indians: Identity and the survival of Native America. Berkeley, CA: University California; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Garroutte Eva M, Beals Janette, Keane Ellen M, Kaufman Carol, Spicer Paul, Henderson Jeff, Henderson Patricia N, Mitchell Christina M, Manson Spero M and the AI-SUPERPFP Team. Religiosity and spiritual engagement in two American Indian populations. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(3):480–500. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2009.01461.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill Jerry H. Native American worldviews: An introduction. Amherst, NY: Humanity Books; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gill Sam D. Native American religions: An introduction. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Goins R Turner, Garroutte Eva Marie, Fox Susan Leading, Geiger Sarah Dee, Manson Spero M. Theory and practice in participatory research: Lessons from the Native Elder Care Study. Gerontologist. 2011;51(3):285–294. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnq130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gollnick James. Religion and spirituality in the life cycle. New York: Peter Lang; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grant John W. Moon of wintertime: Missionaries and the Indians of Canada in encounter since 1534. Toronto: University of Toronto Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Hadaway C Kirk, Marler Penny Long. How many Americans attend worship each week? An alternative approach to measurement. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2005;44(3):307–322. [Google Scholar]

- Hout Michael, Greeley Andrew. The center doesn’t hold: Church attendance data. American Sociological Review. 1987;63(3):113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Hultkrantz Åke. Native religions of North America: The power of visions and fertility. San Francisco: Harper and Row; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter James Davison. American evangelicalism: Conservative religion and the quandary of modernity. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin Lee. The dream seekers: Native American visionary traditions of the Great Plains. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Irwin Lee. Freedom, law, and prophecy: A brief history of Native American religious resistance. American Indian Quarterly. 1997;21(1):35–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins Philip. Dream catchers: How mainstream America discovered native spirituality. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Jennings Francis. The invasion of America: Indians, colonialism and the cant of conquest. New York: W. W. Norton; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Kass Jared D, Friedman Richard, Leserman Jane, Zuttermeister Patricia C, Benson Herbert. Health outcomes and a new index of spiritual experience. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 1991;30(2):203–211. [Google Scholar]

- Kosmin Barry Alexander, Keysar Ariela. Religion in a free market: Religious and non-religious Americans. Ithaca, NY: Paramount Market; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Levitt Mairi. Sexual identity and religious socialization. British Journal of Sociology. 1995;46(3):529–536. [Google Scholar]

- Lizardo Omar, Collett Jessica L. Rescuing the baby from the bathwater: Continuing the conversation on gender, risk, and religiosity. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2009;48(2):256–269. [Google Scholar]

- Long J Scott, Freese Jeremy. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- MacArthur Foundation. MIDMAC: Survey content and availability. 2006 Available at http://midmac.med.harvard.edu/research.html#survey. [Google Scholar]

- MacMaster Samuel A, Crawford Sharon L, Jones Jenny L, Rasch Randolf F, Thompson Stephanie J, Sanders Edwin C. Metropolitan Community AIDS Network: Faith-based culturally relevant services for African American substance users at risk of HIV. Health and Social Work. 2007;32(2):151–154. doi: 10.1093/hsw/32.2.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Joel W. The land looks after us: A history of Native American religions. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- McNally Michael D. The practice of Native American Christianity. Church History. 2000;69(4):834–859. [Google Scholar]

- McNally Michael D. Research report: Native American religious and cultural freedom: An introductory essay. 2005 Available at http://www.pluralism.org/research/profiles/display.php?profile=73332. [Google Scholar]

- Mead Frank S, Hill Samuel S, Atwood Craig D. Handbook of denominations in the United States. 12th ed. Nashville, TN: Abingdon Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Michael Yvonne L, Farquhar Stephanie A, Wiggins Noelle, Green Mandy K. Findings from a community-based participatory prevention research intervention designed to increase social capital in Latino and African American communities. Journal of Immigrant Minority Health. 2008;10(3):281–289. doi: 10.1007/s10903-007-9078-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller Alan S, Stark Rodney. Gender and religiousness: Can socialization explanations be saved? American Journal of Sociology. 2002;107(6):1399–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Nagel Joane. American Indian ethnic renewal: Red power and the resurgence of identity and culture. New York: Oxford University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Norton Ilena M, Manson Spero M. Research in American Indian and Alaska Native communities: Navigating the cultural universe of values and process. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64(5):856–860. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life. U.S. Religious Landscapes Survey 2008. Religious affiliation: Diverse and dynamic. 2008 Available at http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Putnam Robert D. Bowling alone: The collapse and revival of American community. New York: Simon & Schuster; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rollings Willard Hughes. Unaffected by the gospel: Osage resistance to the Christian invasion 1673–1906: A cultural victory. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sandefur Gary D, Rindfuss Ronald R, Cohen Barry., editors. Changing numbers, changing needs: American Indian demography and public health. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat Darren E. Counterculture of continuity? Competing influences on baby boomers’ religious orientations and participation. Social Forces. 1998;76(3):1087–1115. [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat Darren E. Sexuality and religious commitment in the United States: An empirical examination. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(2):313–323. [Google Scholar]

- Snipp C Matthew. American Indians: The first of this land. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Stark Rodney. Physiology and faith: Addressing the “universal” gender difference in religious commitment. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(3):495–507. [Google Scholar]

- Steinmetz Paul B. Pipe, Bible, and peyote among the Oglala Lakota: A study in religious identity. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart Omer C. Peyote religion: A history. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sullins D Paul. Gender and religion: Deconstructing universality, constructing complexity. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;112(3):838–880. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Edward H, Jr, Remmes Kathryn R. Does masculinity thwart being religious? An examination of older men’s religiousness. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2002;41(3):521–532. [Google Scholar]

- Topper Martin D. Mormon placement: The effects of missionary foster families on Navajo adolescents. Ethos. 1979;7(2):142–160. [Google Scholar]

- Uecker Jeremy E, Regnerus Mark D, Vaaler Margaret L. Losing my religion: The social sources of religious decline in early adulthood. Social Forces. 2007;85(4):1667–1693. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. The 2011 Statistical Abstract. 2011 Available at http://www.census.gov/compendia/statab/cats/population.html.

- U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Indian Affairs. Tribal leaders directory. 2010 Available at http://www.bia.gov/DocumentLibrary/index.htm.

- Xie Yu, Goyette Kimberly. The racial identification of biracial children with one Asian parent: Evidence from the 1990 census. Social Forces. 1997;76(2):547–570. [Google Scholar]