Abstract

The μ-opioid receptor (MOR) is the primary target for opioid analgesics. MOR induces analgesia through the inhibition of second messenger pathways and the modulation of ion channels activity. Nevertheless, cellular excitation has also been demonstrated, and proposed to mediate reduction of therapeutic efficacy and opioid-induced hyperalgesia upon prolonged exposure to opioids. In this mini-perspective, we review the recently identified, functional MOR isoform subclass, which consists of six transmembrane helices (6TM) and may play an important role in MOR signaling. There is evidence that 6TM MOR signals through very different cellular pathways and may mediate excitatory cellular effects rather than the classic inhibitory effects produced by the stimulation of the major (7TM) isoform. Therefore, the development of 6TM and 7TM MOR selective compounds represent a new and exciting opportunity to better understand the mechanisms of action and the pharmacodynamic properties of a new class of opioids.

Keywords: Review, μ-opioid receptor, 6TM MOR isoform, drug discovery

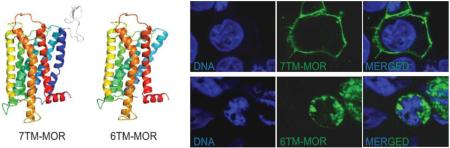

Graphical Abstract

1. Introduction: biphasic cellular inhibitory and excitatory effects of MOR agonists

Opioids are the most frequently used and effective analgesics for the treatment of moderate to severe pain. Unfortunately, both acute and chronic use is frequently associated with a number of adverse side effects such as respiratory depression, nausea, constipation, itching, xerostomia, drowsiness, as well as physical and psychological addiction. In addition, the prolonged use of opioids may lead to reduced efficacy (tolerance) and a clinically significant problem of post dosing opioid-induced hyperalgesia (OIH).1-3 At a cellular level, MOR is a primary target for clinically used opioids, and MOR-induced analgesia is due to the initiation of presynaptic and/or postsynaptic inhibitory processes that decrease the electrical excitability, neurotransmitter release, and/or pro-nociceptive processes.

The canonical seven transmembrane (7TM) MOR is a member of the G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) family. MOR signaling involves activation of a pertussis toxin (PTX)-sensitive G-proteins (Gαi/o). Receptor activation leads to the dissociation of the heterotrimeric G-protein complex: the release of the α subunit inhibits adenylyl cyclase, while the βγ subunit activates K+ channels or inhibits voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (VGCC).4-6 MOR-mediated inhibition of VGCC on the central presynaptic terminals of primary afferent nociceptors is thought to be one of the primary mechanisms mediating the spinal analgesic effects of opiates. K+ channel activation is a primary mechanism underlying the inhibitory actions of MOR on central nervous system neurons.7-9

Similarly to the analgesic effects of opioids, tolerance and OIH are also manifested in both animals and human following acute or chronic dosing.10-13 The neural mechanisms that underlie hyperalgesic effects are poorly understood, but are dependent on the concentration of the drug and the duration of exposure.4,14 A biphasic effect of opioids on cAMP formation and substance P release has also been demonstrated.4,14-18 There is evidence that the excitatory actions of MOR reflect a switch in the G protein coupling profile of the MOR from G1 to both Gs 4,19-21 and Gq,14 as well as adenylyl cyclase (AC) activation by Gβγ. 18,21 There is additional evidence for a critical role of β-arrestin in MOR desensitization and tolerance. It has been shown that in mice lacking β-arrestin-2, MOR desensitization does not occur after chronic morphine treatment and these animals fail to develop tolerance, although they still develop physical dependence.22

2. Genomic organization of OPRM1 gene

The major isoform of MOR, also called MOR-1, is coded by exons 1, 2, 3 and 4 of MOR gene locus (OPRM1), where exon 1 codes for the first transmembrane domain and exons 2 and 3 code for all the other transmembrane domains. Gene structure is highly conserved between human, mouse and rat. Today, at least 30 splice variants of MOR in mice, 16 in rats and 19 in humans have been identified.23 There are two common splicing patterns of OPRM1 that involve the C-terminus and N-terminus. C-terminus variants contain exons 1, 2 and 3 and code for all seven transmembrane domains, but differ structurally and functionally at the intracellular domains. The N-terminus also has a number of variants, some of which encode for truncated receptors with only six transmembrane domains (6TM, coded by exons 2 and 3). While other truncated receptors have been reported,24-27 analysis of the functional significance of truncated MOR receptors is still ongoing. Some truncated receptors can modulate the activity of the full version of receptor24-26 or change the biological activity of the protein, sometimes in the opposite direction.27

The 6TM MOR variants were first cloned from mouse.28 Five 6TM alternatively spliced isoforms were first reported, of which three (MOR-1G, MOR-1M, and MOR-1N) have an initial methionine positioned at exon 11 that codes for the N-terminus of the protein, and two isoforms (MOR-1K and MOR-1L) have the initial methionine positioned at the beginning of exon 2. The latter MOR mRNA splice variants also code for a short upstream peptide. The potential for these mRNA splice variants to code for 6TM MOR isoform has not been explored. Furthermore, none of the five variants have been shown to bind opioid ligands by [3H]-DAMGO displacement experiments, and thus, the functionality of these receptor variants has been questioned.28

The first described human 6TM OPRM1 isoform29 was referred to as MOR-3. It has no reported analogue in mouse or rat, and its first methionine is positioned at the beginning of exon 2. On a functional level, COS-1 cells transiently overexpressing MOR-3 receptor exhibit a dose-dependent release of nitric oxide (NO) following treatment with morphine. MOR-3 possesses a unique intracellular C-terminal amino acid sequence that has been hypothesized to serve as a coupling or docking domain required for constitutively expressed NO synthase activation.30 The expression of MOR-3 has been detected in human vascular tissue, mononuclear cells, polymorphonuclear cells, and human neuroblastoma cells by northern blot and reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR).29 The physiological and cellular pathways whereby this isoform contributes to opioid responses have not been yet identified.

Using comparative genomic approaches we reported that the human OPRM1 gene is much more complex than previously shown and has orthologs to all described mouse exons.31 Our association study analysis identified a new potentially functional single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP), namely rs563649, which showed strong contribution to variability in pain sensitivity and morphine analgesia. This finding allowed us to clone a new human isoform (MOR-1K) that carries SNP rs563649. The human MOR-1K is orthologous to mouse MOR-1K, containing an ortholog of mouse exon 13. Although similar to the human MOR-3 variant reported by Cadet29 and initiated from methionine in exon 2, MOR-1K codes for a truncated 6TM receptor isoform with an intracellular domain identical to the major MOR-1 isoform, which is different from MOR-3. In contrast to MOR-3, MOR-1K is also expressed in neuronal cell lines, neuronal tissues, and brain regions that mediate the pharmacodynamic effects of MOR agonists. The minor T allele situated in the 5’-untranslated region (5’-UTR) of MOR-1K mRNA is associated with higher pain sensitivity as well as a poorer analgesic response to morphine. It codes for higher translation efficiency of the 6TM receptor isoform,31 suggesting that the expression of the 6TM variant produces a pronociceptive effect.

In line with these observations, cellular studies with MOR-1K suggest that, after agonist activation, this isoform drives excitatory rather than the classic inhibitory cellular responses following the stimulation of the 7TM isoform.32 Indeed, morphine-induced activation of MOR-1K increases the production of excitatory mediators (e.g., Ca2+ and NO). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation experiments reveal that MOR-1K couples to Gαs, rather than Gαi/o (which classically couples with the major MOR1 isoform).32 These data suggest that MOR-1K can function as a counterbalance to the actions mediated by the 7TM isoform and may mediate the molecular processes that underlie OIH and pharmacological tolerance.

The human ortholog of mouse exon 11 also has been cloned by Pan and coworkers.33 Four new alternatively spliced forms (MOR-1G1, MOR-1G2, MOR-1I and MOR-1H) have been identified that contain exon 11 spliced either directly to exon 2 or to exon 1 through a variable 3’ acceptor splice site.33 These RNAs code for either the extended 7TM receptor isoforms (MOR-1I and MOR-1H) or for 6TM receptor isoforms, namely MOR-1G1 and MOR-1G2. While MOR-1G1 codes for the same amino acid sequence of the MOR-1K variant, MOR-1G2 is characterized by the presence of additional 10 residues at the N-terminal domain of the protein. Importantly, the human exon 11, which was cloned by Pan and coworkers, corresponds to the predicted exon 11 by Shabalina et al. revealed by comparative genomic approaches.31 This observation suggest the existence of additional exons, and reconfirms the existence of a unique class of human 6TM receptor isoforms (Figure 1).

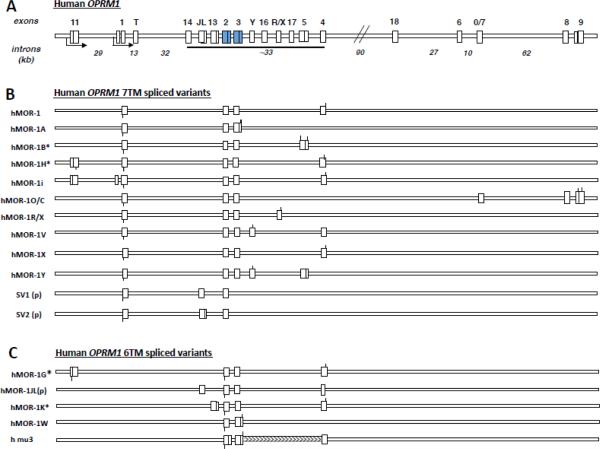

Figure 1. Schematic structure of human OPRM1 spliced variants.

(A) All predicted and cloned exons of human OPRM1 gene are in accordance with the NCBI database, UCSC genome browser GRCh37/hg19. Exons and introns are shown by vertical and horizontal boxes, respectively. Solid boxes represent constitutive exons coding for transmembrane dolmens 2-7. (B) All cloned alternatively spliced variants of OPRM1 coding for 7TM receptor isoforms. (C) All cloned alternatively spliced variants of OPRM1 coding for 6TM receptor isoforms, (p) partial sequence, (*) exons with variable exon/intron boundaries. Start codons of MOR isoforms are schematically indicated by lower vertical bars, while stop codons are indicated by upper vertical bars. Maximal sizes of human exons (for lower panel) are shown in parentheses (nt): exon 11 (206), exon 1 (580), exon T (117), exon 14 (105), exon 13 (1200), exon 2 (353), exon 3 (521), exon Y (109), exon 16 (314), exon X (1271), exon 17 (128), exon 5 (1013), exon 4 (304), exon 18 (412), exon 6 (124), exon 7 (89), exon 9 (393).

3. Receptor structure for 7TM and 6TM MOR

Before the MOR structure was resolved at high-resolution,34 in silico modeling was performed to predict its structure.35-38 Using homology modeling,38,39 we have reconstructed and further refined a structural model for 7TM MOR (Figure 2A).40 Based on the computational prediction of 7TM MOR, we designed several 7TM MORs carrying mutations in the ligand binding pocket, as well as 7TM MOR variants with mutations outside of the binding site as controls.38 Results of competitive radioligand displacement experiments and cAMP inhibition assay of the proposed mutants were fully consistent with our structural model. The model is also consistent with the recently solved MOR crystal structure,34 with a deviation of ~3.5Å.

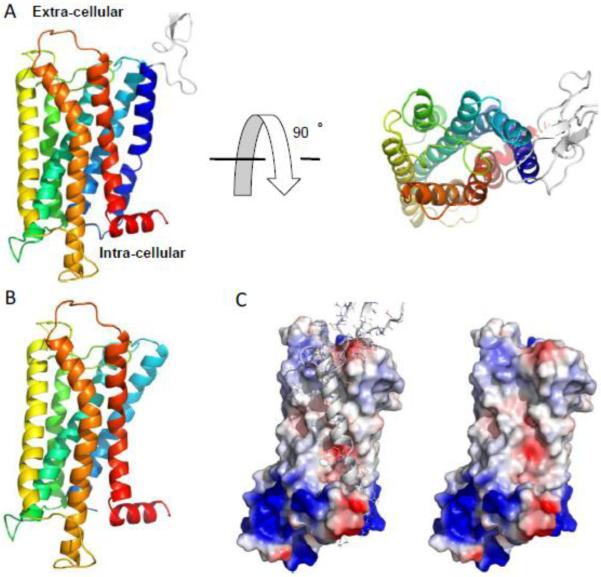

Figure 2.

Computer model of 7TM and 6TM MOR. (A) The experimentally validated structure model of 7TM MOR. The protein is shown in cartoon representation with rainbow color for N-(blue) to C-terminal (red). The extra-cellular loop is white with a weak propensity to form β-strands. (B) The initial 6TM model with the N-terminal 100 residues excised from the 7TM model. (C) The surface of 6TM model structure colored according to the local electrostatic potential. Blue and red colors correspond to positively and negatively charged surfaces, respectively, and white color corresponds the neutral hydrophobic ones.

Compared to 7TM MOR, the 6TM isoform lacks a segment of 100 residues in the N-terminal, including the extra-cellular domain as well as the first transmembrane helix (TMH1) (Figure 2B). The absence of TMH1 in 6TM MOR paves the way to a plethora of different structural hypotheses that could be potentially related to the excitatory cellular response observed upon stimulation of 6TM isoform. The newly membrane exposed surface of 6TM MOR is characterized by a different charge distribution (Figure 2C). Therefore, a possible rearrangement in the plasma membrane of the remaining helices may result in differences in ligand binding and G protein activation compared to wild type isoform. The lack of TMH1 in 6TM MOR can also alter the functional plasticity of the receptor and its ability to interact with specific intracellular signaling proteins (i.e., G protein and/or β-arrestin isoforms). Furthermore, it cannot be excluded that 6TM competes with 7TM MOR for the binding of opioids or for interactions with other GPCRs, thus reshaping intracellular GPCR-dependent signaling cascades and the resulting cellular responses.41 All of these scenarios are equally likely at this time. Therefore, there is a substantial need to further structural and functional investigations of the biological signaling mechanism mediated by 6TM MOR.

4. Cellular localization of 7TM and 6TM MOR isoforms

The cellular localization of the two MOR isoforms has recently been reported for both human and mouse.32,42 Two independent groups have showed that the 6TM MOR isoform overexpressed in mammalian cells is not constitutively expressed on the cytoplasmic membrane, but instead it is localized in intracellular compartments (Figure 3). Nevertheless, it has been shown that cells overexpressing intracellular 6TM bind fluorescently labeled naloxone.32 Furthermore, the co-transfection of the orphanin FQ receptor ORL1 (opioid receptor-like) with the 6TM variant enables high-affinity binding of the recently synthesized 6TM MOR ligand iodobenzoylnaltrexamide (IBNtxA) to 6TM MOR.42 No IBNtxA binding is observed in cells transfected with either 6TM MOR or ORL1 alone, however, binding is detected in brain tissues from 7TM MOR knockout (KO) mice.42

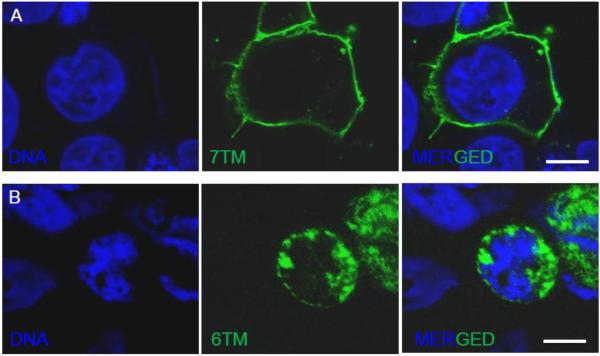

Figure 3.

Cellular localization of 7TM or 6TM MOR isoforms shows. Confocal images of HEK-293 cells expressing 7TM or 6TM MOR: A) 7TM MOR localizes on the cell surface, B) 6TM isoform is mainly localized in intracellular compartments. HEK-293 cells were transiently transfected with plasmids encoding MYC-tagged 7TM or FLAG-tagged 6TM. After forty-eight hours cells were fixed and stained with either Anti-MYC-FITC Antibody or Anti-DYKDDDDK Tag Antibody (Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate); DNA was counterstained with Hoechst 33342. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Taken together, these results suggest that the lack of the first transmembrane in MOR protein structure dramatically alters the subcellular localization of 6TM MOR and implies that the expression of the 6TM variant alone is insufficient to enable ligand binding. It is still possible that similarly to the sigma receptor (Sigma-1)43 or estrogen receptor GPR30,44 intracellularly localized 6TM can bind ligands and produce cellular signaling. It should also be recognized that 6TM MOR may be translocated to the cell surface with the aid of a cytoplasmic chaperone. Alternatively, the presence of a plasma membrane GPCR partner such as ORL1 or other GPCRs can coordinate plasma membrane co-localization and assembly, thus leading to function as a mosaic of proteins that act in concert to mediate the cellular signaling evoked by opioid ligands.

5. Behavioral studies in knockout mice demonstrate functional differences in MOR isoforms

Several studies have shown that OPRM1 is essential for morphine's analgesic actions because complete OPRM1 KO mice show a complete loss of morphine analgesia.45-47 However, KO mice with the deletion of only exon 1 or only exon 11 show substantial differences in their sensitivity to opioids. Exon 1 KO mice, which should still express 6TM receptor variants, show reduced analgesic response to heroin and morphine 6-glucuronide (M6G), but do not respond to methadone or morphine.48 In contrast, mice lacking exon 11, which can still produce 7TM receptor variants, do not show an analgesic response to heroin, fentanyl, and M6G, but are responsive to methadone and morphine.49 The absence of analgesic response to morphine in exon 1 KO mice, but not in exon 11 KO mice, is in line with the proposed hypothesis that 7TM but not 6TM MOR isoform, exclusively or largely, underlies cellular inhibitory effects of morphine and contributes to analgesia. More importantly, our results pertaining to the 6TM-dependent excitatory cellular effects of morphine32 also suggest that exon 1 KO mice may show reduced or hyperalgesic responses to morphine administration, while exon 11 KO mice, which lack the excitatory 6TM receptor variant, should show diminished OIH. This model has been indirectly examined in “triple KO” mice that lack the first exons in all three genes encoding for opioid receptors (μ, δ, and κ). The thermal nociceptive responses to morphine and oxymorphone in triple KO compared to control mice have been examined. The acute administration of test opioids (morphine or oxymorphone) in control animals evokes a profound analgesia that is absent in the triple KO mice. In contrast, a continuous infusion of either morphine or oxymorphone evokes hyperalgesia in the triple KO mice in comparison with control mice.50 Since the original MOR KO line was derived from an exon 1 KO variant,48 which leaves exon 11 available to code for 6TM variants of MOR, triple KO mice should completely lack 7TM but not 6TM variants of MOR.

Recently, Majumdar et al.42,51 demonstrated a potent opioid analgesia evoked in triple KO mice by IBNtxA and iodobenzoylnaloxamide (IBNalA), which are both morphinane derivatives. The analgesia evoked by these compounds was associated with a lack of respiratory depression, physical dependence, reward behavior, and significant constipation. Analgesia was lost in the exon 11 MOR-1 KO mice indicating that IBNtxA and IBNalA effects involve exon 11-associated MOR-1 variants, those coding for the 6TM MOR isoform. The authors reported that IBNtxA and IBNalA bind to brain lysates of the triple KO mice, which suggests the direct interaction with 6TM MOR isoform.42 However, they also demonstrated that these opioids showed high affinity for the reference 7TM variants of the three opioid receptor subtypes (in vitro affinity data and competitions studies performed with radiolabelled IBNTxA and IBNalA are reported in Tables 1 and 2, respectively).52

Table 1.

Affinity of IBNTxA and IBNalA for opioid receptor subtypes.

| Drug |

Ki (nM)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| μ-OR | δ-OR | κ-OR | |

| IBNTxA | 2.50 ± 0.82 | 0.58 ± 0.16 | 0.23 ± 0.16 |

| IBNalA | 0.70 ± 0.18 | 2.55 ± 0.74 | 0.08 ± 0.006 |

|

KD (nM)b

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| μ-OR | δ-OR | κ-OR | |

| IBNTxA | 0.11 ± 0.02 | 0.24 ± 0.005 | 0.027 ± 0.0001 |

| IBNalA | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 2.5 ± 0.22 | 0.05 ± 0.22 |

Table adapted from ref. 52.

Competition studies of 125I -radiolabelled compounds against 3H-opioids performed with 3H-DAMGO (μ-OR), 3H-DPDPE (δ-OR), and 3H-U69,593 (κ-OR) at 1 nM concentration in stably transfected CHO Cell lines. Ki values are reported as mean ± SEM; for further details refer to ref 52.

Saturation studies of 125I-labelled compounds in stably transfected CHO cell lines. Kd values are reported as mean ± SEM; for further details refer to ref. 52. Abbreviation: DAMGO, D-Ala-N-MePhe-Glyol-enkephalin; DPDPE, D-Penicillamine-2-D-Penicillamine-5-enkephalin; U69,593, N-methyl-2-phenyl-N-[(5R,7S,8S)-7-pyrrolidin-1-yl-1-oxaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl]-acetamide.

Table 2.

Competton studies of radiolabeled IBNTxA and IBNalA.

| Drug |

Ki (nM) |

|

|---|---|---|

| IBNTxA | IBNalA | |

| μ-OR | ||

| CTAP | 2.33 ± 0.48 | 2.96 ± 1.07 |

| Naloxone | 4.23 ± 0.42 | 2.27 ± 0.60 |

| Levallorphan | 1.29 ± 0.14 | 1.69 ± 0.60 |

| Naltrexone | 1.15 ± 0.10 | 2.71 ± 1.0 |

| DAMGO | 3.34 ± 0.43 | 0.45 ± 0.12 |

| Morphine | 4.60 ± 1.81 | 2.52 ± 0.28 |

| δ-OR | ||

| DPDPE | 1.39 ± 0.67 | 1.77 ± 0.80 |

| Naltrindole | 0.46 ± 0.32 | 0.50 ± 0.20 |

| κ-OR | ||

| norBNI | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 0.19 ± 0.08 |

| 5’GNTI | 0.15 ± 0.07 | 0.19 ± 0.05 |

| (−)U50,488H | 0.73 ± 0.32 | 0.95 ± 0.37 |

Table adapted from ref. 52. Competition studies were performed for each compound against 125IBNTxA and 125IBNalA at 0.1 nM concentration in membranes from stably transected CHO cell lines. Ki values are expressed as mean ± SEM; for further information refer to ref. 52. Abbreviation: CTAP, D-Phe-Cys-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Penicillamine-Thr-NH2; DAMGO, D-Ala-N-MePhe-Glyol-enkephalin; DPDPE, D-Penicillamine-2-D-Penicillamine-5-enkephalin; norBNI, nor-binailorphimine; 5'GNTI, 5'-Guanidinonaltrindole; U50,488U, 2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N- [(1R,2R)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-cyclohexyl]-acetamide.

6. A paradox

An apparent paradox to the hypothesis that agonists of the 6TM isoform may produce excitatory effects, OIH, and analgesic tolerance to opioids needs to be acknowledged. First, opioid analgesia is evoked by heroin, fentanyl, and M6G in exon 1 KO (6TM sparing) mice and greatly diminished in exon 11 KO (7TM sparing).49 Furthermore, in studies by Majumdar and co-workers, IBNtxA and IBNalA produced analgesia in triple exon 1 KO mice.42,51 These results are not in line with the observed hyperalgesic effects of the minor T allele of rs563649, coding for higher expression of 6TM MOR-1K variant,31 and the 6TM-dependent cellular excitatory effects of morphine and IBNtxA.32,53 However, there are several possible reasons for this apparent paradox. First, it is possible that there are still undiscovered OPRM1 spliced forms that contain exon 11 but not exon 1, that code for a functional 7TM isoform, or there is a difference in a signaling between 6TM MOR isoforms initiated from exon 11 and exon 2 and varying in their N-terminus (such as MOR-1G2 and MOR-1K23,54). A second possible explanation is that both 7TM and 6TM receptor isoforms are promiscuous in terms of G-protein binding capacity and both isoforms can bind either Gi or Gs proteins,55 though, as a general rule, the stimulation of the 7TM isoform signals through binding with Gi and stimulation of the 6TM isoform favors Gs binding. Certain “biased” agonists may produce sufficient thermodynamic changes to permit “protean agonism” whereby an agonist is able to produce a receptor activation state and signaling through a non-canonical pathway.56 In line with this hypothesis, potentially, developmental adaptation in the exon 1 KO animals may take place that would switch the balance of Gi/Gs/Gq coupling for 6TM variants in the absence of expression of 7TM variants. Furthermore, it can be hypothesized that specific GPCRs can partner with 6TM MOR at the cellular membrane (see section entitled cellular localization of 7TM and 6TM MOR isoforms) producing a temporally dynamic mosaic of molecular partners and, thus, different cellular signaling responses. The macromolecular composition may be influenced by the individual's history of opioid exposure or exposures to physical and psychological stressors that influence the expression and cellular distribution of 6TM MOR resulting in qualitative and quantitative differences in the pharmacodynamic responses to opioids. These responses can also depend on the concentration of a ligand, such that a low concentration may produce analgesia and higher concentrations may produce hyperalgesia. In line with this suggestion, the concentrations of morphine and IBNtxA that produced cellular excitatory effects occur at relatively high concentration (1-10 μM).32,53 Finally, it should be noted that the M6G analgesia reported in exon 1 MOR1 KO mice (6TM sparing) has not been uniformly observed. A recent study by van Dorp and coworkers57 showed both acute and chronic M6G administration to triple KO mice (deletion of exon 1 of MOR1, 6TM sparing) leads to a profound hyperalgesia.

7. Conclusions and significance

MOR agonists are the most widely used analgesics, prescribed for both acute postoperative pain and chronic pain conditions; yet, there are substantial side effects that limit usage. Thus, a further understanding of the molecular and cellular mechanisms that contribute to the analgesic, hyperalgesic, and analgesic tolerance effects of opioids is needed. Current published findings provide evidence that the 6TM MOR isoform is not just another alternatively spliced form of OPRM1, but instead it displays substantial differences in cellular distribution, evoked cellular responses, contributions to the cellular excitatory responses to opioids, and it shows evidence of both hyperalgesic and analgesic responses. Because of the potentially dual contribution of the 6TM MOR isoform to analgesic signaling, further research targeting this isoform is warranted. The development of highly selective and specific agonists and antagonists of the 6TM and 7TM MOR isoforms, as well as ligand biased compounds are required to elucidate the biological and cellular properties engaged by these distinct isoforms subclasses. The elucidation of signaling pathways associated with 6TM and 7TM MOR isoforms, along with understanding of the endogenous properties of these isoforms and the ligands that modify the biological activities of these MOR variants, will enable the development of opioids that show a high degree of analgesic efficacy with fewer side-effects.

HIGHLIGHTS.

6TM MOR is a functional isoform of μ-opioid receptor;

6TM MOR has a different cellular localization with respect to 7TM-MOR;

6TM MOR may signal via different cellular pathways with respect to 7TM MOR;

6TM MOR stimulation may mediate excitatory cellular effects.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by NIDA, NIDCR and NINDS grants R41DA032293-01, RO1-DE16558, UO1-DE017018, R01GM080742, NS41670 and PO1 NS045685.

ABBREVIATIONS

- MOR

μ-opioid receptor

- 6TM MOR

six transmembrane helices μ-opioid receptor

- 7TM MOR

seven transmembrane helices μ-opioid receptor

- OIH

opioid induced hyperalgesia

- VGCC

voltage-gated Ca2+ channels

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- AC

adenylyl cyclase

- OPRM1

μ-opioid receptor locus

- DAMGO

Ala-2-MePhe-4-Glyol-5-Enkephalin

- COS-1

CV-1 carrying the SV40 genetic material fibroblast-like cells

- NO

nitric oxide

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction

- SNP

single nuclotide polymorphism

- MOR-1K

μ-opioid receptor carrying the SNP rs563649

- TMH1

transmembrane helix 1

- GPCR

G protein-coupled receptor

- ORL1

orphanin FQ receptor

- IBNTxA

iodobenzoylnaltrexamide

- IBNalA

iodobenzoylnaloxamide

- M6G

morphine 6-glucuronide

- HEK-293

human embryonic kidney 293 cells

- MYC-tag

N-EQKLISEEDL-C

- Anti-MYC-FITC

fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-MYC antibody

- CHO

Chinese hamster ovary

- DPDPE

D-Penicillamine-2-DPenicillamine-5-Enkephalin

- U69,593

N-methyl-2-phenyl-N-[(5R,7S,8S)-7-pyrrolidin-1-yl-1-oxaspiro[4.5]decan-8-yl]-acetamide

- CTAP

D-Phe-Cys-D-Trp-Arg-Thr-Penicillamine-Thr-NH2

- norBNI

nor-binaltorphimine

- 5’GNTI

5’-Guanidinonaltrindole

- U50,488U

2-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-N-methyl-N-[(1R,2R)-2-pyrrolidin-1-yl-cyclohexyl]-acetamide

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Drs. Diatchenko and Maixner are cofounders, officers and equity shareholder in Algynomics, Inc. Dr. Dokholyan is a small equity shareholder and consultant to Algynomics, Inc. Algynomics is a company that specializes in pain diagnostics and therapeutics. Dr. Dokholyan is a founder, officer and equity shareholder in Molecules in Action. Molecules in Action is a company that specialized in scientific consulting and customized software development. A portion of the work presented in this manuscript was supported by Algynomics, Inc., and Molecules in Action, LLC. The work presented in the manuscript may have a potential commercial value.

References

- 1.a Ballantyne JC, Shin NS. Efficacy of opioids for chronic pain: a review of the evidence. Clin. J. Pain. 2008;24:469–478. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b2f26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chang G, Chen L, Mao J. Opioid tolerance and hyperalgesia. Med. Clin. North Am. 2007;91:199–211. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kim SH, Stoicea N, Soghomonyan S, Bergese SD. Intraoperative use of remifentanil and opioid induced hyperalgesia/acute opioid tolerance: systematic review. Front. Pharmacol. 2014;108(5):1–9. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Middleton C, Harden Acquired pharmaco-dynamic opioid tolerance: a concept analysis. J. J. Adv. Nurs. 2014;70(2):272–281. doi: 10.1111/jan.12150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Lee M, Silverman SM, Hansen H, Patel VB, Manchikanti L. A comprehensive review of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Pain Physician. 2011;14(2):145–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Low Y, Clarke CF, Huh BK. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia: a review of epidemiology, mechanisms and management. Singapore Med. J. 2012;53(5):357–360. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Raehal KM, Schmid CL, Groer CE, Bohn LM. Functional selectivity at the μ-opioid receptor; implications for understanding opioid analgesia and tolerance. Pharmacol. Rev. 2011;63(4):1001–1019. doi: 10.1124/pr.111.004598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Morgan MM, Christie MJ. Analysis of opioid efficacy, tolerance, addiction and dependence from cell culture to human. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2011;164(4):1322–1334. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01335.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu LF, Angst MS, Clark D. Opioid-induced hyperalgesia in humans: molecular mechanisms and clinical considerations. Clin. J. Pain. 2008;24:479–496. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0b013e31816b2f43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crain SM, Shen KF. Antagonists of excitatory opioid receptor functions enhance morphine's analgesic potency and attenuate opioid tolerance/dependence liability. Pain. 2000;84:121–131. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.North RA. Membrane conductances and opioid receptor subtypes. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1986;71:81–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol. Rev. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herz A, Millan MJ. Opioids and opioid receptors mediating antinociception at various levels of the neuraxis. Physiol. Bohemoslov. 1990;39:395–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Millan MJ. Descending control of pain. Prog. Neurobiol. 2002;66:355–474. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(02)00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stanfa L, Dickenson A. Spinal opioid systems in inflammation. Inflamm. Res. 1995;44:231–241. doi: 10.1007/BF01782974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crain SM, Shen KF. Acute thermal hyperalgesia elicited by low-dose morphine in normal mice is blocked by ultra-low-dose naltrexone, unmasking potent opioid analgesia. Brain Res. 2001;888:75–82. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)03010-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kayser V, Besson JM, Guilbaud G. Paradoxical hyperalgesic effect of exceedingly low doses of systemic morphine in an animal model of persistent pain (Freund's adjuvant-induced arthritic rats). Brain Res. 1987;414:155–157. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(87)91338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levine JD, Gordon NC, Fields HL. Naloxone dose dependently produces analgesia and hyperalgesia in postoperative pain. Nature. 1979;278:740–741. doi: 10.1038/278740a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li X, Angst MS, Clark JD. A murine model of opioid-induced hyperalgesia. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2001;86:56–62. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(00)00260-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rubovitch V, Gafni M, Sarne Y. The mu opioid agonist DAMGO stimulates cAMP production in SK-N-SH cells through a PLC-PKC-Ca++ pathway. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 2003;110:261–266. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(02)00656-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Suarez-Roca H, Abdullah L, Zuniga JR, Madison S, Maixner W. Multiphasic effect of morphine on the release of substance P from rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis slices. Brain Res. 1992;579:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90050-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suarez-Roca H, Maixner W. Morphine produces a multiphasic effect on the release of substance P from rat trigeminal nucleus caudalis slices by activating different opioid receptor subtypes. Brain Res. 1992;579:195–203. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90051-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suarez-Roca H, Maixner W. Morphine produces a bidirectional modulation of substance P release from cultured dorsal root ganglion. Neurosci. Lett. 1995;194:41–44. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11721-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang HY, Friedman E, Olmstead MC, Burns LH. Ultra-low-dose naloxone suppresses opioid tolerance, dependence and associated changes in mu opioid receptor-G protein coupling and Gbetagamma signaling. Neuroscience. 2005;135:247–261. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Esmaeili-Mahani S, Shimokawa N, Javan M, Maghsoudi N, Motamedi F, Koibuchi N, Ahmadiani A. Low-dose morphine induces hyperalgesia through activation of G alphas, protein kinase C, and L-type Ca 2+ channels in rats. J. Neurosci. Res. 2008;86:471–479. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mostany R, Diaz A, Valdizan EM, Rodriguez-Munoz M, Garzon J, Hurle MA. Supersensitivity to mu-opioid receptor-mediated inhibition of the adenylyl cyclase pathway involves pertussis toxin-resistant Galpha protein subunits. Neuropharmacology. 2008;54:989–997. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang HY, Burns LH. Gbetagamma that interacts with adenylyl cyclase in opioid tolerance originates from a Gs protein. J. Neurobiol. 2006;66:1302–1310. doi: 10.1002/neu.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–723. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pasternak GW. Opioids and their receptors: Are we there yet? Neuropharmacol. 2014;76:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2013.03.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karpa KD, Lin R, Kabbani N, Levenson R. The dopamine D3 receptor interacts with itself and the truncated D3 splice variant d3nf: D3-D3nf interaction causes mislocalization of D3 receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 2000;58:677–683. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.4.677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nag K, Sultana N, Kato A, Hirose S. Headless splice variant acting as dominant negative calcitonin receptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007;362:1037–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu X, Wess J. Truncated V2 vasopressin receptors as negative regulators of wild-type V2 receptor function. Biochem. 1998;37:15773–15784. doi: 10.1021/bi981162z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boise LH, Gonzalez-Garcia M, Postema CE, Ding L, Lindsten T, Turka LA, Mao X, Nunez G, Thompson CB. Bcl-x, a bcl-2-related gene that functions as a dominant regulator of apoptotic cell death. Cell. 1993;74:597–608. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90508-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan YX, Xu J, Mahurter L, Bolan E, Xu M, Pasternak GW. Generation of the mu opioid receptor (MOR-1) protein by three new splice variants of the Oprm gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2001;98:14084–14089. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241296098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cadet P, Mantione KJ, Stefano GB. Molecular identification and functional expression of mu 3, a novel alternatively spliced variant of the human mu opiate receptor gene. J. Immunol. 2003;170:5118–5123. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kream RM, Sheehan M, Cadet P, Mantione KJ, Zhu W, Casares F, Stefano GB. Persistence of evolutionary memory: primordial six-transmembrane helical domain mu opiate receptors selectively linked to endogenous morphine signaling. Med. Sci. Monit. 2007;13:SC5–SC6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shabalina SA, Zaykin DV, Gris P, Ogurtsov AY, Gauthier J, Shibata K, Tchivileva IE, Belfer I, Mishra B, Kiselycznyk C, Wallace MR, Staud R, Spiridonov NA, Max MB, Goldman D, Fillingim RB, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. Expansion of the human mu-opioid receptor gene architecture: novel functional variants. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009;18:1037–1051. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gris P, Gauthier J, Cheng P, Gibson DG, Gris D, Laur O, Pierson J, Wentworth S, Nackley AG, Maixner W, Diatchenko L. A novel alternatively spliced isoform of the muopioid receptor: functional antagonism. Mol. Pain. 2010;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu J, Xu M, Hurd YL, Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Isolation and characterization of new exon 11-associated N-terminal splice variants of the human mu opioid receptor gene. J. Neurochem. 2009;108:962–972. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manglik A, Kruse AC, Kobilka TS, Thian FS, Mathiesen JM, Sunahara RK, Pardo L, Weis WI, Kobilka BK, Granier S. Crystal structure of the micro-opioid receptor bound to a morphinan antagonist. Nature. 2012;485:321–326. doi: 10.1038/nature10954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alkorta I, Loew GH. A 3D model of the delta opioid receptor and ligand-receptor complexes. Protein Eng. 1996;9:573–583. doi: 10.1093/protein/9.7.573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Filizola M, Laakkonen L, Loew GH. 3D modeling, ligand binding and activation studies of the cloned mouse delta, mu; and kappa opioid receptors. Protein Eng. 1999;12:927–942. doi: 10.1093/protein/12.11.927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pogozheva ID, Lomize AL, Mosberg HI. Opioid receptor three-dimensional structures from distance geometry calculations with hydrogen bonding constraints. Biophys. J. 1998;75:612–634. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77552-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strahs D, Weinstein H. Comparative modeling and molecular dynamics studies of the delta, kappa and mu opioid receptors. Protein Eng. 1997;10:1019–1038. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.9.1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Serohijos AW, Chen Y, Ding F, Elston TC, Dokholyan NV. A structural model reveals energy transduction in dynein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18540–18545. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602867103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Serohijos AW, Yin S, Ding F, Gauthier J, Gibson DG, Maixner W, Dokholyan NV, Diatchenko L. Structural basis for mu-opioid receptor binding and activation. Structure. 2011;19:1683–1690. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wise H. The roles played by highly truncated splice variants of G protein-coupled receptors. J. Mol. Signal. 2012;7:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Majumdar S, Grinnell S, Le R Rouzic V, Burgman M, Polikar L, Ansonoff M, Pintar J, Pan YX, Pasternak GW. Truncated G protein-coupled mu opioid receptor MOR-1 splice variants are targets for highly potent opioid analgesics lacking side effects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:19778–19783. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115231108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi T, Su TP. Sigma-1 receptor chaperones at the ER-mitochondrion interface regulate Ca(2+) signaling and cell survival. Cell. 2007;131:596–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Revankar CM, Cimino DF, Sklar LA, Arterburn JB, Prossnitz ER. A transmembrane intracellular estrogen receptor mediates rapid cell signaling. Science. 2005;307:1625–1630. doi: 10.1126/science.1106943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loh HH, Liu HC, Cavalli A, Yang W, Chen YF, Wei LN. mu Opioid receptor knockout in mice: effects on ligand-induced analgesia and morphine lethality. Brain Res. Mol. Brain Res. 1998;54:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00353-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matthes HW, Maldonado R, Simonin F, Valverde O, Slowe S, Kitchen I, Befort K, Dierich A, Le Meur M, Dolle P, Tzavara E, Hanoune J, Roques BP, Kieffer BL. Loss of morphine-induced analgesia, reward effect and withdrawal symptoms in mice lacking the mu-opioid-receptor gene. Nature. 1996;383:819–823. doi: 10.1038/383819a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sora I, Takahashi N, Funada M, Ujike H, Revay RS, Donovan DM, Miner LL, Uhl GR. Opiate receptor knockout mice define mu receptor roles in endogenous nociceptive responses and morphine-induced analgesia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:1544–1549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schuller AG, King MA, Zhang J, Bolan E, Pan YX, Morgan DJ, Chang A, Czick ME, Unterwald EM, Pasternak GW, Pintar JE. Retention of heroin and morphine-6 beta-glucuronide analgesia in a new line of mice lacking exon 1 of MOR-1. Nat. Neurosci. 1999;2:151–156. doi: 10.1038/5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pan YX, Xu J, Xu M, Rossi GC, Matulonis JE, Pasternak GW. Involvement of exon 11-associated variants of the mu opioid receptor MOR-1 in heroin, but not morphine, actions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:4917–4922. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811586106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Juni A, Klein G, Pintar JE, Kest B. Nociception increases during opioid infusion in opioid receptor triple knock-out mice. Neuroscience. 2007;147:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Majumdar S, Subrath J, Le Rouzic V, Polikar L, Burgman M, Nagakura K, Ocampo J, Haselton N, Pasternak AR, Grinnell S, Pan YX, Pasternak GW. Synthesis and evaluation of aryl-naloxamide opiate analgesics targeting truncated exon11-associated μ opioid receptor (Mor-1) splice variants. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:6352–6362. doi: 10.1021/jm300305c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Majumdar S, Burgman M, Haselton N, Grinnel S, Ocampo J, Pasternak AR, Pasternak GW. eneration of novel radiolabelled opiates through site-selective iodination. Biorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;21:4001–4004. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samoshkin A, Viet CT, Convertino M, Maixner W, Dokholyan NV, Schmidt B, Diatchenko L. Structural and functional interaction between 6TM MOR isoform and β2 adrenoreceptor.. International Narcotics Research Conference 2014; Montreal, Quebec, Canada. July 13-18, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pasternak GW, Pan YX. Mu opioids and their receptors: evolution of a concept. Pharmacol. Rev. 2013;65:1257–1317. doi: 10.1124/pr.112.007138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hermans E. Biological and pharmacological control of the multiplicity of coupling at G-protein-coupled receptors. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003;99:25–44. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(03)00051-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kenakin T. Functional selectivity through protean and biased agonism: who steers the ship? Mol. Pharmacol. 2007;72:1393–1401. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.040352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.van Dorp EL, Kest B, Kowalczyk WJ, Morariu AM, Waxman AR, Arout CA, Dahan A, Sarton EY. Morphine-6beta-glucuronide rapidly increases pain sensitivity independently of opioid receptor activity in mice and humans. Anesthesiology. 2009;110:1356–1363. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181a105de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]