Abstract

CLIP-associated proteins CLASPs are mammalian microtubule (MT) plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs) that promote MT rescue in vivo. Their plus-end localization is dependent on other +TIPs, EB1 and CLIP-170, but in the leading edge of the cell, CLASPs display lattice-binding activity. MT association of CLASPs is suggested to be regulated by multiple TOG (tumor overexpressed gene) domains and by the serine-arginine (SR)-rich region, which contains binding sites for EB1. Here, we report the crystal structures of the two TOG domains of CLASP2. Both domains consist of six HEAT repeats, which are similar to the canonical paddle-like tubulin-binding TOG domains, but have arched conformations. The degrees and directions of curvature are different between the two TOG domains, implying that they have distinct roles in MT binding. Using biochemical, molecular modeling and cell biological analyses, we have investigated the interactions between the TOG domains and αβ-tubulin and found that each domain associates differently with αβ-tubulin. Our findings suggest that, by varying the degrees of domain curvature, the TOG domains may distinguish the structural conformation of the tubulin dimer, discriminate between different states of MT dynamic instability and thereby function differentially as stabilizers of MTs.

Keywords: crystal structure, microtubule, microtubule-associated protein (MAP), + TIPs, molecular modeling

Introduction

Microtubules (MTs) are highly dynamic polymers of α- and β-tubulin heterodimers that play essential roles in mitosis, intracellular transport and cell polarity. The head-to-tail association of the tubulin dimer makes MTs polar structures, which is critical for the functions of MT arrays in cells. Every tubulin dimer is oriented with β-tubulin pointing toward the faster polymerizing plus-end of a MT and, following assembly, GTP hydrolysis occurs on the β-tubulin subunit. The MT plus-ends extend to the cell periphery, undergoing alternate phases of growth and shrinkage involving two transition states termed catastrophe and rescue, a process known as dynamic instability [1,2]. This intrinsic dynamic behavior enables the MT cytoskeleton to search the interior of the cell and capture targets, such as kinetochores, vesicles and the cellular cortex.

The balance between dynamically unstable and stable MTs is finely controlled by proteins that associate with either MTs or tubulin dimers. In particular, the proteins that accumulate at growing MT plus-ends are called MT plus-end tracking proteins (+TIPs) [3]. CLIP-associated proteins CLASPs, a family of +TIPs, localize at kinetochores, the spindle midzone, the Golgi apparatus and the cell cortex where they play multifunctional roles in mitosis and cell motility [4–7]. Because CLASP1α and CLASP2α possess a tubulin-binding module known as the TOG (tumor overexpressed gene) domain, first identified in the XMAP215/Dis family proteins, CLASPs are considered to be MT-stabilizing factors [7,8]. XMAP215, which contains five TOG domains at its N terminus, functions as a processive MT polymerase: XMAP215 binds tubulin dimers to facilitate their incorporation into MT plus-ends [9]. Crystallographic analyses showed that TOG domains form a “paddle” structure containing six pairs of anti-parallel helices and a conserved flat tubulin-binding surface [10–12]. Furthermore, the crystal structure of the complex of the TOG domain from the yeast XMAP215 homolog Stu2 (Stu2-TOG1) with αβ-tubulin revealed that Stu2-TOG1 forms a 1:1 complex with the αβ-tubulin dimer via the flat surface [13]. Precise sequence analyses of various TOG domains have indicated that CLASPs possess multiple TOG domains that stabilize MTs [12,14]. However, the recent crystal structure of the CLASP1 TOG domain (hC1-TOG2) showed not only that the cryptic hC1-TOG2 is a bona fide TOG domain but also that its tubulin-binding surface is convex, which suggests that the recognition mechanism of tubulin by CLASPs differs from that of the XMAP215/Dis family [15]. Supporting these findings, the in vivo distribution of CLASPs is not identical to that of XMAP215. CLASPs associate with the MT lattice as well as with plus-ends [16], whereas XMAP215 accumulates at plus-ends and diffuses along the lattice [17]. Because each TOG domain of XMAP215 has a different affinity for tubulin, and each contributes to its activity in a distinct manner [18], the combination of multiple TOG domains may provide CLASPs with unique abilities to associate with tubulin or MTs.

Both in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that, unlike XMAP215, CLASPs promote MT rescue and inhibit catastrophe [19,20]. Although CLASPs are conserved among animals and fungi [21,22], vertebrate CLASPs exhibit novel features not observed in the yeast CLASP homolog. First, mammalian CLASPs form a complex with other +TIPs, such as CLIP-170 and EB1, and regulate plus-end dynamics, presumably in a cooperative manner [7,20,23]. Second, CLASPs are substrates of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3), and multiphosphorylation by GSK3 inhibits binding of CLASPs to MTs [16,23,24]. These GSK3 phosphorylation sites are located in the serine-arginine (SR)-rich sequences required for efficient association with MTs [18,19,25]. The SR regions of CLASPs possess SxIP (Ser-x-Ile-Pro) motifs, known as EB1-binding sequences, and the interactions between CLASPs and EB1 or MTs are strongly influenced by GSK3 phosphorylation of CLASPs [26,27]. Therefore, multiple mechanisms are thought to be involved in CLASP-mediated MT stabilization.

To investigate the effects of each TOG domain on CLASP-mediated MT dynamics, we determined the crystal structures of the two TOG domains (TOG2 and TOG3) of CLASP2. We found that these TOGs have arched structures but assume the different orientation of the curvature from that of the canonical TOG domain, Stu2-TOG1. Based on these structures, we investigated tubulin binding by CLASP2 in vitro and in silico. Our data suggested that the two TOG domains have different affinity for tubulin and MTs. Furthermore, mutations of either TOG domain or EB1-binding sites decreased the rescue frequency of MTs in vivo. Our results reveal that both TOGs and EB1 binding are essential for the full rescue activity of CLASP2.

Results

Crystal structure of two TOG domains

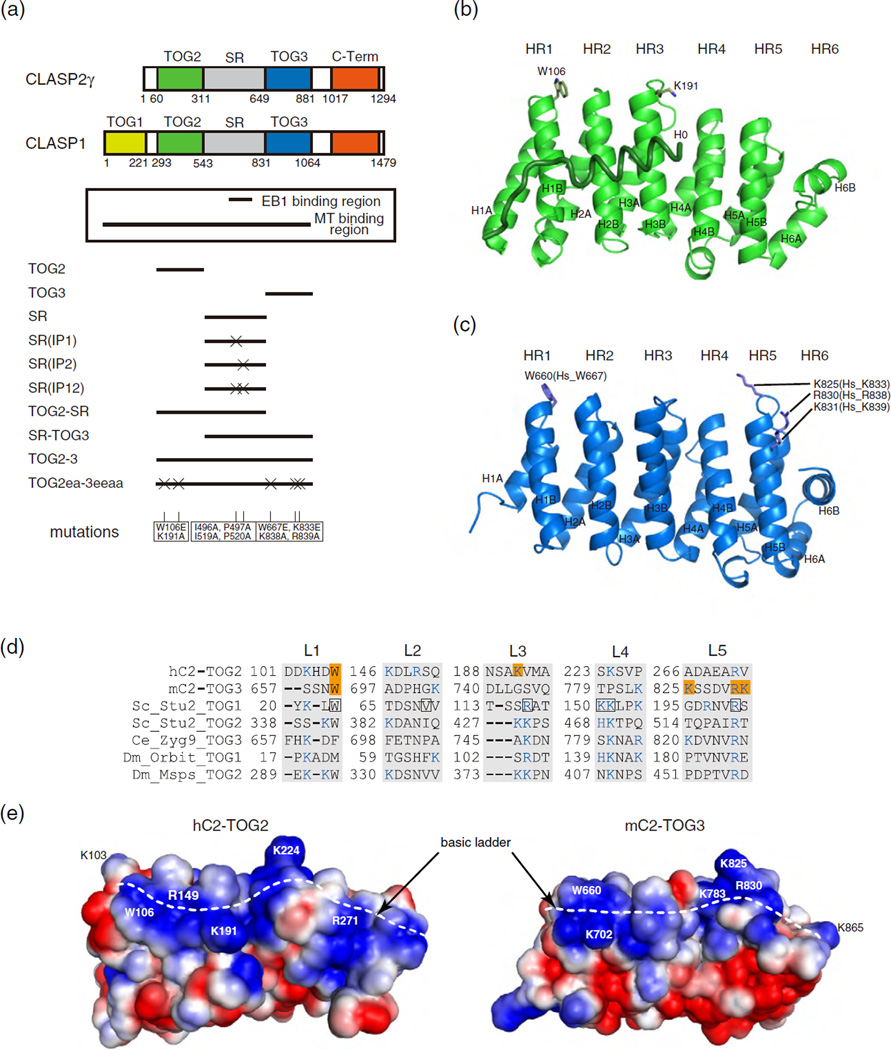

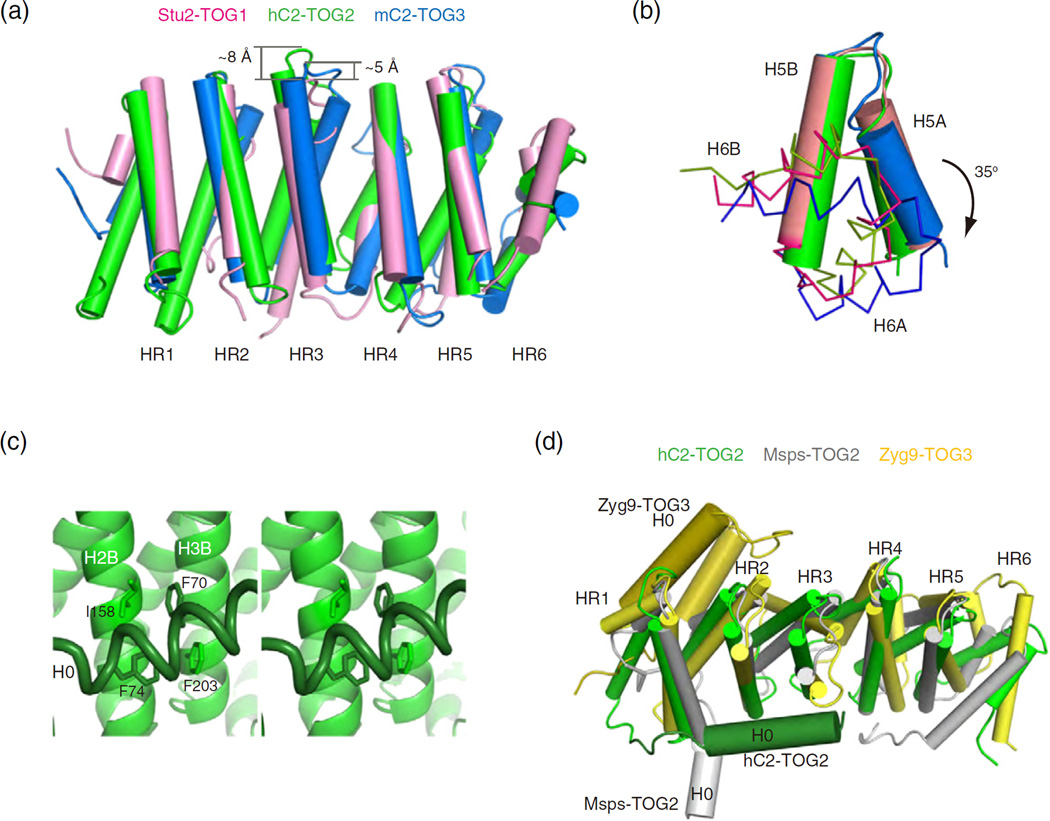

In mammals, CLASPs have two closely related paralogs: ubiquitously expressed CLASP1 and nervous-system-enriched CLASP2 [7]. The N-terminal regions of both CLASPs are sufficient for association with MTs [4,16]. Although CLASP1 has an extra TOG domain at its N terminus, CLASP1 and CLASP2 play similar roles in organizing interphase MTs (Fig. 1a) [20]. Based on the assumption that the N-terminal half of CLASP2 is sufficient to function as a MT-binding region, we determined the crystal structures of two TOG domains of CLASP2γ [human TOG2 (residues 60–310; hC2-TOG2) and mouse TOG3 (residues 642–873, corresponding to residues 649–881 in human; mC2-TOG3)] (Fig. 1b and c and Table 1). Whereas the hC2-TOG2 crystal contained a single molecule in the asymmetric unit, the mC2-TOG3 crystal contained four crystallographically independent molecules whose structures were nearly identical to each other (RMS deviation for 217 Cα positions of 1.0 Å at maximum). The architecture of both TOG domains resembles a canonical TOG domain fold comprising six HEAT repeats (HR1-6). In particular, the structure of hC2-TOG2 is very similar to that of hC1-TOG2 with RMS deviation of 1.1 Å for 241 Cα atoms (PDB code 4K92) [15]. Furthermore, both domains possess a surface consisting of a tryptophan residue with a ladder of basic residues, which is often conserved in other tubulin-binding TOG domains (Fig. 1d and e and Supplementary Fig. S1) [12,14]. In Stu2-TOG1, residues at the major tubulin-contacting sites are located in the L1, L4 and L5 loops [10,13]. In hC2-TOG2, the consensus residues are mostly conserved (W106, K224 and R271 in L1, L4 and L5, respectively). In addition, K103, R149 and K191 in L1, L2 and L3, respectively, serve to increase the basicity of the tubulin-binding surface. Superimposition of HRs of hC2-TOG2 onto those of Stu2-TOG1 reveals that the third repeat, HR3, is shifted upward by ~8 Å in hC2-TOG2, which was seen in the crystal structure of hC1-TOG2 (Fig. 2a) [15]. On the other hand, the basic residues are not strictly conserved in mC2-TOG3: L3 lacks basic residues, resulting in a discontinuous basic ladder on the surface. The structural arrangement in mC2-TOG3 is rather divergent from the canonical TOGs. As is observed in the hC2-TOG2 structure, HR3 in mC2-TOG3 is shifted slightly upward by ~5 Å. The C terminus of the H4A helix is disordered, which creates the extended L4 loop with a basic residue K783. The C-terminal repeat, HR6, is rotated clockwise by 35° relative to the analogous regions of Stu2-TOG1 and hC2-TOG2, resulting in an elongated basic ladder containing K865 (K863 in human) (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 1.

Crystal structure of the TOG domains from CLASP2. (a) Domain organization of CLASP1 and CLASP2γ. EB1- and MT-binding regions are shown in the box. Schematics of the constructs of human CLASP2 tested in this in vitro study are shown below the box. Mutations used in this study are listed at the bottom. (b and c) Cartoon representation of hC2-TOG2 (b) and mC2-TOG3 (c). The H0 helix of hC2-TOG2 is shown as a coil. The N-terminal helices of HRs are labeled “A” and the C-terminal helices are labeled “B”. Residues mutated in this study are shown in stick representation. In (c), mouse TOG3 residue numbers are labeled, and the corresponding numbers in human TOG3 are indicated in brackets. (d) Sequences of the tubulin-binding loops (L1-5) in TOG domains whose structures were determined previously: hC2-TOG2; mC2-TOG3; Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Sc) Stu2 TOG1 and TOG2; Caenorhabditis elegans (Ce) Zyg9 TOG3; Drosophila melanogaster (Dm) Orbit TOG1 and Msps TOG2. Residues mutated in this study are highlighted in orange. Basic residues forming a basic ladder are colored blue. The tubulin-binding residues seen in the Stu2-TOG1:tubulin complex are boxed in black. (e) Electrostatic potential of hC2-TOG2 (left) and mC2-TOG3 (right) countered from –1.5 kTe−1 (red) to +1.5 kTe−1 (blue), as calculated by APBS [52]. The orientation is the same as in (b) and (c). The H0 helix in hC2-TOG2 is not included. Residues discussed in the text are labeled. The basic ladders are indicated with white broken lines.

Table 1.

Crystallographic data and refinement statistics

| Structure | hC2-TOG2 | mC2-TOG3 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||||

| Beamline | PF BL-5A | PF BL-6A | PF BL-5A | ||||

| Space group | P3221 | P21 | |||||

| Unit cell dimensions | |||||||

| a (Å) | 58.8 | 58.8 | 50.9 | ||||

| b (Å) | 58.8 | 58.8 | 122.3 | ||||

| c (Å) | 157.1 | 158.0 | 86.5 | ||||

| β (°) | 94.7 | ||||||

| Data range (Å) | 50–2.0 | 50–2.6 | 50–2.1 | ||||

| Data set | Native | Se Peak | Se Edge | Se Remote | Se Peak | Se Edge | Se Remote |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1 | 0.97901 | 0.97931 | 0.96408 | 0.97803 | 0.97921 | 0.96399 |

| No. of unique reflections | 24,043 | 10,685 | 10,924 | 10,905 | 56,897 | 56,946 | 57,102 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.9 (99.6) | 97.7 (78.2) | 99.8 (96.3) | 99.7 (96.8) | 92.9 (67.7) | 92.8 (67.7) | 92.7 (63.5) |

| I/σ(I) | 62.0 (2.9) | 22.5 (0.9) | 30.2 (1.3) | 26.7 (1.3) | 20.3 (2.0) | 20.2 (2.0) | 18.1 (1.1) |

| Rmergea | 0.04 (0.65) | 0.10 (0.92) | 0.10 (0.86) | 0.10 (0.85) | 0.06 (0.47) | 0.05 (0.45) | 0.08 (0.90) |

| Overall figure of merit | 0.37 (SOLVE), 0.60 (RESOLVE) | 0.36 (SOLVE), 0.66 (RESOLVE) | |||||

| Refinement | |||||||

| Resolution range (Å) | 42.7–2.1 | 50–2.2 | |||||

| No. of reflections in working set | 18,642 | 50,760 | |||||

| Rcryst (Rfree)b | 0.18 (0.24) | 0.24 (0.28) | |||||

| Bond length RMS deviation (Å) | 0.005 | 0.006 | |||||

| Bond angles RMS deviation (°) | 1.1 | 0.9 | |||||

| Ramachandran analysis, favored/allowed area (%) | 99.2/0.8 | 98.9/1.1 | |||||

Numbers in parentheses refer to statistics for the highest shell of data.

Rmerge = ∑|Iobs –⟨l⟩|/∑Iobs, where Iobs is the intensity measurement and ⟨I⟩ is the mean intensity for multiply recorded reflections.

Rcryst and Rfree = ∑|Fobs| – |Fcalc||/Fobs| for reflections in the working and test sets, respectively. The Rfree value was calculated using a randomly selected 10% of the data set that was omitted throughout all stages of refinement.

Fig. 2.

Structural comparison of TOG domains. (a) Superposition of hC2-TOG2 (green), mC2-TOG3 (blue) and Stu2-TOG1 (pink). HEAT repeats are shown as cylinders. Structures are superimposed using HR1-5. HR3s of hC2-TOG2 and mC2-TOG3 are shifted upward by ~8 Å and ~5 Å, respectively, relative to that of Stu2-TOG1. (b) Superposition of HR5 and HR6 of hC2-TOG2, mC2-TOG3 and Stu2-TOG2. Colors are the same as in (a). HR5 is shown as cylinders, and HR6 is shown as ribbons. HR6 in mC2-TOG3 is rotated by 35° clockwise relative to HR6 of hC2-TOG2 and Stu2-TOG2. (c) Stereoview of the environment of H0 in hC2-TOG2. Heat repeats HR2 and HR3, contacting H0, are shown in cartoon representation and H0 in tube. Residues involved in hydrophobic interactions are shown in stick representation (F70 and F74 in H0, I158 in H2B and F203 in H3B). (d) Relative orientations of H0 helices in hC2-TOG2 (green), Msps TOG2 (gray; PDB code 2QK2) and Zyg9 TOG3 (yellow; code: 2OF3), shown as thicker cylinders. H0 helices are compared, after superposition of HR1-5 in three TOG domains. The view is rotated 90° around the horizontal axis with respect to (a).

hC2-TOG2 possesses an extra helix at its N terminus

hC2-TOG2 possesses an H0 helix prior to the N-terminal HR1, which is resistant to protease treatment (data not shown). In the hC2-TOG2 structure, H0 is attached to the broad surface of the paddle structure, where F70 and F74 in H0 make hydrophobic contacts with I158 and F203 in H2B and H3B, respectively (Fig. 2c). Interactions between H0 and the paddle structure are identical between hC2-TOG2 and hC1-TOG2 [15]. These hydrophobic residues are fairly well conserved among homologous TOG2 in CLASP proteins (Supplementary Fig. S1). However, no significant sequence similarity exists between the H0 in hC2-TOG2 and H0-containing TOG domains of Zyg9 and Msps. The relative orientations of H0 helices differ among proteins, suggesting that H0 of hC2-TOG2 stabilizes the paddle structure by contacting HR2 and HR3 (Fig. 2d). In support of this observation, the hC2-TOG2 construct without H0 hardly expressed in Escherichia coli cells and, if any, it tended to aggregate severely (data not shown). Moreover, the crystal structure of hC1-TOG2 revealed that both H0s are located at the same position, although crystallization was performed using a different protein construct and the crystallographic packing was not identical between the two crystals [15]. Thus, H0 is tightly linked to the HEAT repeat structure but is unlikely to participate in interactions with tubulin because H0 is not on the same surface as the basic ladder.

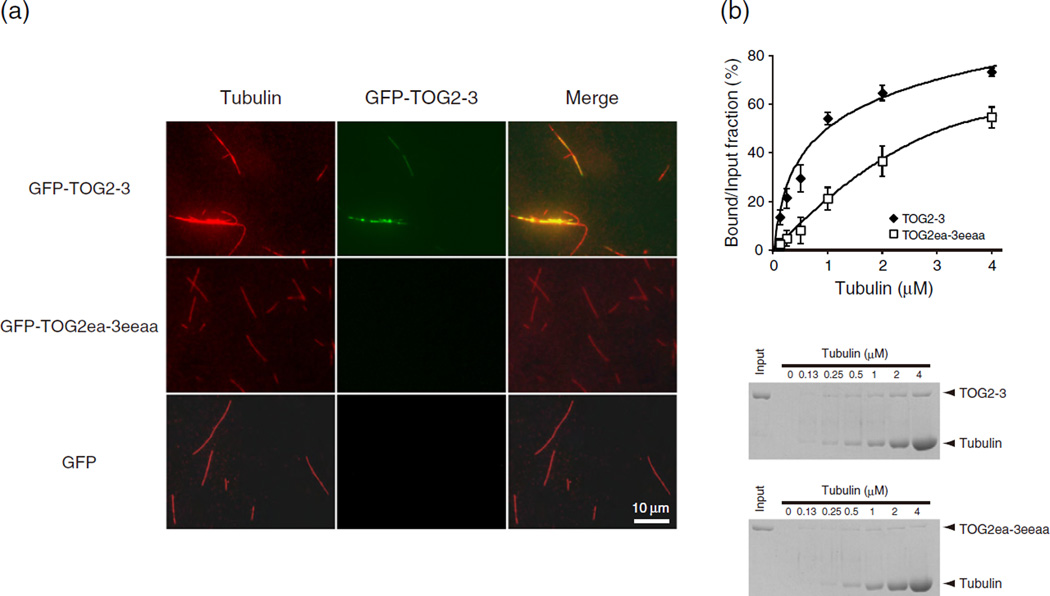

TOG domains are required for MT lattice association of CLASP2

To investigate how CLASP2 associates with MTs, we used a construct containing residues 60–881 of human CLASP2, corresponding to the MT-binding region (TOG2-3). Based on these crystal structures, we introduced simultaneous mutations into hC2-TOG2 and/or hC2-TOG3 (W106E and K191A for TOG2; W667E, K833E, K838A and R839A for TOG3; hereafter these mutants are referred to as TOG2ea and TOG3eeaa, respectively), in order to have the strongest predicted effect on binding. We used TOG2-3 and TOG2ea-3eeaa, both fused to green fluorescent protein (GFP), and compared the MT-binding properties of these fragments in vitro (Fig. 3a). The proteins were incubated with taxolstabilized MTs and visualized without fixation. Wild-type TOG2-3 bound MTs, whereas mutations in both TOG domains decreased the affinity for MTs. This result indicates that the basic surfaces of TOG2 and TOG3 are involved in MT association of CLASP2. These observations also agreed with our quantitative MT pelleting results (Fig. 3b): when taxol-stabilized MTs were mixed with TOG2-3 and sedimented, more than 70% of TOG2-3 co-pelleted with MTs, whereas mutations of the TOG domains decreased the pellet fraction of CLASP2 by 30–60%. The dissociation constant (Kd) of TOG2-3 wild-type binding to MTs is approximately 0.28 µM, where as Kd of TOG2ea-3eeaa was over 1 µM.

Fig. 3.

CLASP2 MT-binding region associates with MT lattice in vitro. (a) GFP-TOG2-3 associates with MTs. Taxol-stabilized fluorescent MTs were incubated with GFP-labeled TOG2-3 and its mutant. The images show MTs (left), associated TOG2-3 (middle) and merged images (right). (b) Binding of GFP-TOG2-3 to taxol-stabilized MTs, as determined by SDS-PAGE, shown at the bottom. Pellet fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining.

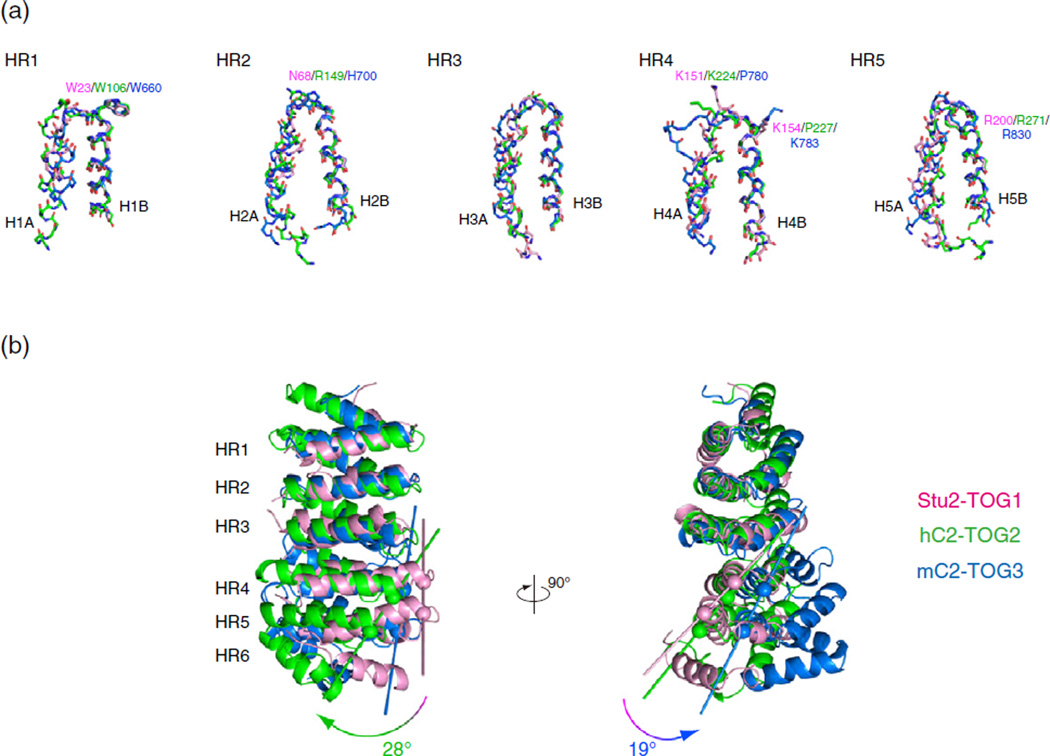

TOG3 possesses a bent conformation different from that of TOG2

Having determined the structures of CLASP2-TOGs, we compared the structures of these TOG domains with Stu2-TOG1, in order to understand the recognition mechanism of each tubulin-TOG complex. First, we dissected these structures and manually superimposed each segment of the HEAT repeats (Fig. 4a). The B helix of the HEAT repeat was used to align the structures because the conserved tubulin recognition residues are located at the N terminus of the B helices, whereas the loop regions flanked by the A helices contain insertion sequences. The sixth repeat was excluded from this alignment because HR6 in mC2-TOG3 stacks on the fifth repeat in an orientation different from those of Stu2-TOG1 and hC2-TOG2. The individual HRs were nicely aligned between TOGs, and the side-chain conformations of the conserved residues were quite similar. When we compared the structures of the multiple HRs between TOGs, we found that HRs including HR3 aligned poorly whereas HRs without HR3 showed lower RMS deviation values (Supplementary Fig. S2). These results suggest that the structural rearrangement occurred at HR3 of CLASP2-TOG2. Because the critical tryptophan residue is located at the N terminus of HR1, we structurally aligned the B helices in the N-terminal HR triad (HR1-3) and compared CLASP2-TOGs to Stu2-TOG1 (Fig. 4b). As seen in the hC1-TOG2, the second HR triad (HR4-6) of hC2-TOG2 was shifted drastically, and the tubulin-binding surface was arched in a convex manner [15]. In contrast to hC2-TOG2, the tubulin-binding surface of mC2-TOG3 formed a relatively flat plane, but the paddle structure of mC2-TOG3 was curved about an axis perpendicular to the surface. By drawing a vector from the N-terminal Cα atom of H4B to that of H5B, we calculated the bending angles to be 28° between Stu2-TOG1 and hC2-TOG2 and 19° between Stu2-TOG1 and mC2-TOG3. Furthermore, structural alignments suggested that, although the basic ladders of CLASP2-TOGs are similar to that of Stu2-TOG1, the structural divergence of TOGs might impact their interactions with the tubulin heterodimer.

Fig. 4.

Dissection of the TOG domains. (a) Structural alignment of HRs. Structures of HR1-5 from hC2-TOG2 (green), mC2-TOG3 (blue) and Stu2-TOG1 (pink) are superimposed using the main-chain Cα atoms of 15 residues in the B helix of each HR. The secondary structure is defined using DSSP [53]. The side chains of the residues involved in tubulin recognition are shown and labeled. (b) Superposition of hC2-TOG2 (green), mC2-TOG3 (blue) and Stu2-TOG1 (pink). Structures are superimposed using the B helices of HR1-3. The curvature was defined as the angle between two vectors connecting the N-terminal Cα atoms of H4B and H5B. The Cα atoms used for creating these vectors are indicated with spheres.

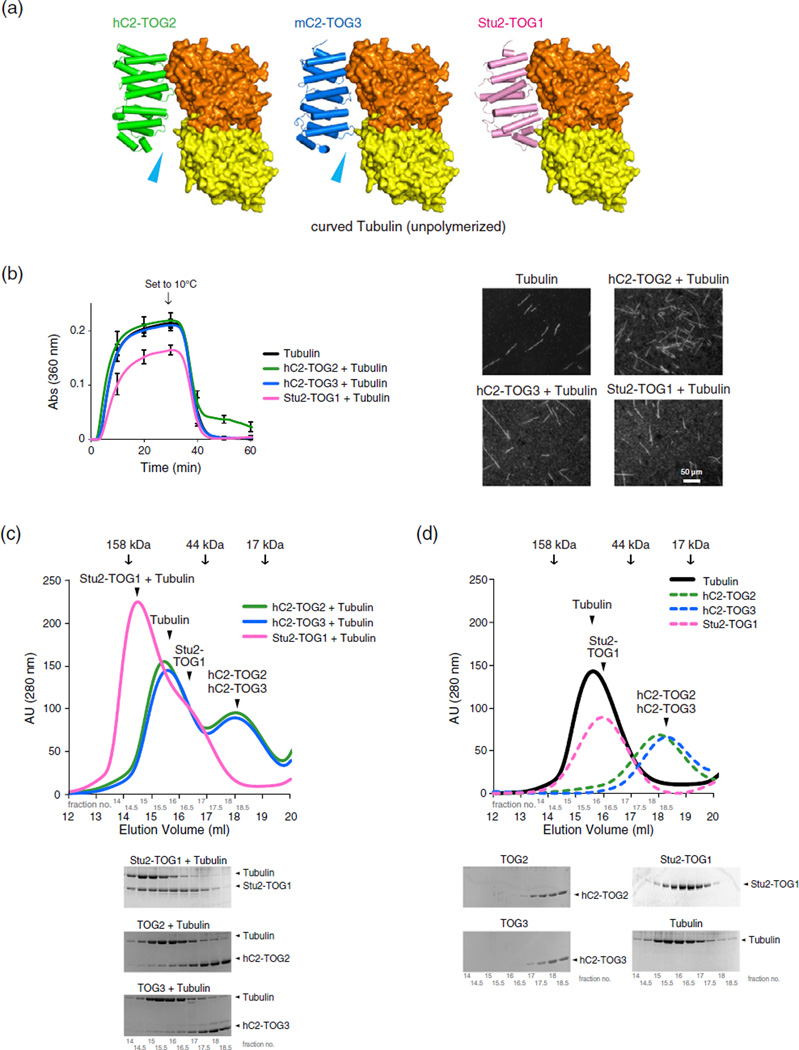

Association of CLASP2-TOGs with unpolymerized tubulin dimer

Our crystallographic analysis suggested that the arched paddle structures of CLASP2-TOGs might result in a different tubulin-binding mode from the Stu2-TOG1:tubulin complex. Therefore, we built models for the complexes between CLASP2-TOGs and the unpolymerized αβ-tubulin heterodimer, using the Stu2-TOG1:αβ-tubulin crystal structure as a guide (Fig. 5a; PDB code 4FFB) [13]. The tubulin dimer in the complex structure possesses a curved conformation, which corresponds to the unpolymerized tubulin dimer in solution. We tried to dock TOGs onto αβ-tubulin by aligning the N-terminal HR triad of CLASP2-TOGs onto that of Stu2-TOG1. As previously reported for the hC1-TOG2, the C terminus of hC2-TOG2 was unable to make contacts with α-tubulin [15], and docking mC2-TOG3 onto the curved tubulin yielded a similar result. The upward-shifted HR3s in CLASP2-TOGs created a gap between C-terminal TOGs and α-tubulin. Our modeling analysis indicated that L1 and L5 of CLASP2-TOGs would be unable to simultaneously contact curved αβ-tubulin. To determine whether TOGs can associate with tubulin, we first tested in vitro MT assembly following cold disassembly in the presence of TOGs. We employed a light-scattering assay to see whether TOGs could inhibit MT formation by binding to tubulin (Fig. 5b) [13]. Tubulin alone began polymerization after ~150 s, and the addition of Stu2-TOG1 increased the lag time to ~210 s, indicating that Stu2-TOG1 bind curved GTP-tubulin and inhibit the polymerization. Unlike Stu2-TOG1, which can bind curved unpolymerized tubulin, hC2-TOG2 or hC2-TOG3 had little effect on MT polymerization. Moreover, the length and the amount of the polymer products were mostly the same (data not shown), implying that CLASP2-TOGs have little affinity for the tubulin dimer. These data are contradictory to the in vitro MT assembly analysis of Drosophila CLASP homolog MAST in which MAST-TOG2 alone can stimulate MT polymerization [15]. When the temperature of the reaction mixture was shifted to 10 °C to induce the cold disassembly, light-scattering and microscope observations revealed that many MT polymers disappeared from the mixtures of tubulin, tubulin with hC2-TOG3 or Stu2-TOG1 after 30 min of switching temperature. On the other hand, the polymers of tubulin mixed with hC2-TOG2 remained, indicating that hC2-TOG2 may be able to have weak contact with disassembling MTs. We also analyzed tubulin binding by TOGs using size-exclusion chromatography and confirmed that CLASP2-TOGs did not form a complex with the tubulin dimer in vitro (Fig. 5c and d). Together, these results indicate that CLASP2-TOGs have a weaker affinity for the unpolymerized tubulin dimer than Stu2-TOG1 or MAST-TOG2. The single CLASP2-TOG domain may associate with tubulin in a different state or the tandem repeat of TOGs (TOG2-3) may be able to bind tubulin by increasing the tubulin-binding sites together with the SR region.

Fig. 5.

TOGs and unpolymerized curved tubulin interactions. (a) The hypothetical models of complexes between CLASP2-TOGs and the unpolymerized αβ-tubulin dimer in the curved conformation. Colors of TOGs are the same as in Fig. 2a. α-Tubulin and β-tubulin are colored yellow and orange, respectively. The complex structure of Stu2-TOG1:curved tubulin is also shown (right panel). Arrows (cyan) indicate the structural gaps between CLASP2-TOGs and α-tubulin; (b) 15 µM tubulin polymerization with 2.5 µM TOGs. (left) The kinetics of assembly as measured by the increase in light scattering. The protein mixtures were initially incubated at 37 °C. After 30 min, the temperature was shifted to 10 °C for 30 min. The reactions with TOGs at several concentration points were analyzed to exclude a protein concentration issue, and in either concentration, CLASP2-TOGs hardly affected the MT assembly (data not shown). The error bar represents the standard deviation of the results from three independent analyses. (right) Fluorescently labeled MTs with TOGs after 60 min of reaction time. (c and d) Gel-filtration analysis of hC2-TOG2, hC2-TOG3 and Stu2-TOG1 with αβ-tubulin. Gel-filtration profiles of tubulin with the TOG domain (c) or the TOG domain alone (d) are shown. Colors indicate the following: green for hC2-TOG2, blue for hC2-TOG3, pink for Stu2-TOG1 and black for tubulin. The elution volumes of molecular mass standards are indicated by arrows. SDS-PAGE analysis is shown below the profiles.

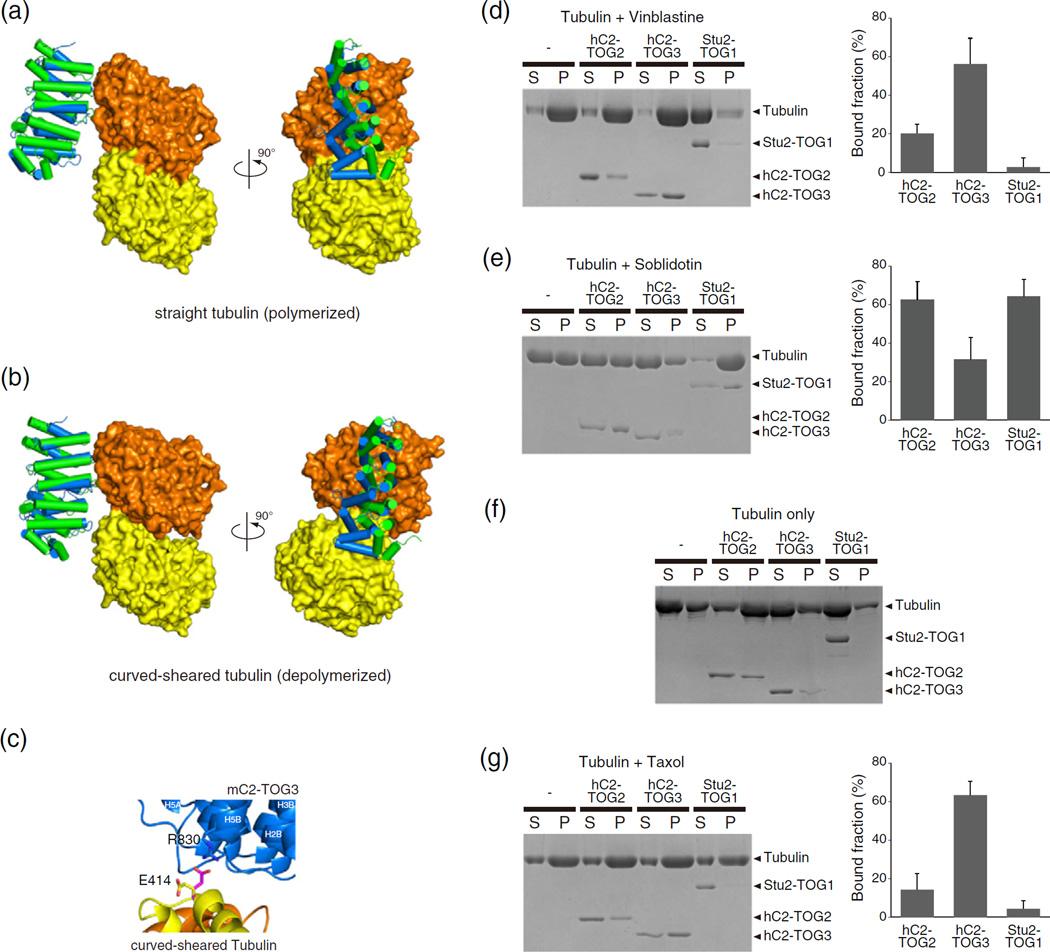

hC2-TOG3 may preferentially bind to the protofilament of depolymerizing MTs

Next, to structurally understand how CLASPs can associate with tubulin or MTs as rescue factors and Stu2 as an MT polymerase [28], we modeled the complex of TOGs and αβ-tubulin in the various states. Currently, several structures of αβ-tubulin in the different conformations are available: the straight form, corresponding to the tubulin structure in the MT lattice, obtained from the zinc-induced tubulin sheets by high-resolution electron microscopy (EM); the curved form in the protofilament, from stathmin-bound tubulin by X-ray crystallography; and the curved-sheared form of MTs induced to depolymerize by kinesin-13, obtained by cryo-EM at 11 Å resolution (PDB codes 1JFF, 1SA0 and 3J2U, respectively; Supplementary Fig. S3) [29–31]. We did not build a model of TOGs and curved stathmin-bound tubulin because the curved tubulin structures of the unpolymerized and stathmin-bound forms were very similar. Previous work showed that α-tubulin is unable to engage in interactions with Stu2-TOG1 when β-tubulin of the straight form is aligned onto β-tubulin of the Stu2-TOG1:αβ-tubulin complex [15]. We also aligned the N-terminal HR triad of CLASP2-TOGs onto the model of Stu2-TOG1:αβ-tubulin in the straight form (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. S4). None of the TOG domains contacted the α-tubulin subunit, suggesting that, although CLASPs interact with the MT lattice in cells, CLASPs may require not only TOG domains but also other interaction sites, such as SR, for CLASP lattice binding. Next, we aligned β-tubulin of curved-sheared αβ-tubulin onto β-tubulin of the Stu2-TOG1:αβ-tubulin complex (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Fig. S5). In this model, we observed unfavorable steric clashes between the side chains of Stu2-TOG1 L6 and α-tubulin. Moreover, the hydrogen bonds between α-tubulin and Stu2-TOG1 L5, as seen in the crystal structure of the yeast protein complex, were broken due to the sheared orientation of the α- and β-tubulin subunits. When the N-terminal HR triad of hC2-TOG2 was aligned onto Stu2-TOG1 in the model, neither L4 nor L5 of hC2-TOG2 interacted with tubulin. The first HR triad of mC2-TOG3 was also aligned in the same fashion to the N terminus of Stu2-TOG1; a reasonable fit was achieved for the C-terminal region of mC2-TOG3, creating a hydrogen bond between R830 in mC2-TOG3 and E414 in α-tubulin (E415 in yeast) (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Fig. S6). In this model, a displacement between the tubulin subunits resulted in a good fit to the bent conformation of mC2-TOG3, suggesting that mC2-TOG3 may possibly bind to the tubulin protofilament of depolymerizing MTs. To assess the relative affinities of TOGs to the curved MT structure, we compared the binding of TOGs to vinblastine-induced tubulin spirals, which mimic the curved protofilament structure (Fig. 6d) [32,33]. While addition of Stu2-TOG1 likely promoted depolymerization of tubulin spirals, both CLASP2-TOGs associated with vinblastine-treated tubulin; hC2-TOG3 had 3× more affinity than hC2-TOG2, which is in an agreement with the molecular modeling analysis. We also tested TOGs binding to tubulin rings whose protofilaments have a higher curvature, by using a dolastatin analog, soblidotin (Fig. 6e) [34,35]. While hC2-TOG3 showed a reduced affinity for tubulin rings or even induced depolymerization of the protofilaments, hC2-TOG2 associated with the rings at a higher level, indicating that the degree and the direction of the bent conformation of CLASP2-TOGs may affect the binding affinity for tubulin rings. Interestingly, Stu2-TOG1 was co-precipitated with tubulin rings. This finding suggests that Stu2-TOG1 may be able to distinguish the subtle structural difference of depolymerizing protofilaments when it works as a tubulin depolymerase. Since the soblidotin-binding site is located at the interface of the two-tubulin dimers in the longitudinal direction [35], we speculate that hC2-TOG2 may be able to stabilize the longitudinal contacts between tubulin dimers. Thus, we performed co-sedimentation assays of tubulin with TOGs in the absence of MT targeting agents (Fig. 6f). We performed this experiment without a cushion buffer in order to see the subtle interaction between TOGs and oligomeric tubulin polymers. When the mixture of tubulin with hC2-TOG3 or Stu2-TOG1 was ultracentrifuged, little amount of tubulin was found in the pellet fraction. On the other hand, tubulin and hC2-TOG2 were significantly co-sedimented, implying that hC2-TOG2 may associate with oligomeric tubulin polymer or connect two tubulin dimers to mediate the interactions in the longitudinal direction. In addition, we examined TOGs binding to taxol-stabilized MTs to see how they interact with straight polymerized tubulin in vitro (Fig. 6g). Both Stu2-TOG1 and hC2-TOG2 exhibited little binding to MTs, whereas hC2-TOG3 binds MTs at the same extent as vinblastine-tubulin. The result of hC2-TOG3 is contradictory to our in silico modeling. hC2-TOG3 may be able to have an affinity for the two-dimensionally extended structure of tubulin, which was not taken into account our modeling analysis using a tubulin dimer. Further structural and modeling analyses are required for TOGs and tubulin interactions.

Fig. 6.

TOGs and tubulin interactions. (a and b) The hypothetical models of the complexes of αβ-tubulin with CLASP2-TOGs. The models of CLASP2-TOGs with straight tubulin in the MT lattice (a) and depolymerized curved-sheared tubulin (b) are shown. All colors are the same as in Fig. 5a. (c) Close-up view of the interaction site of the hypothetical model between mC2-TOG3 and curved-sheared αβ-tubulin. Cartoon models of mC2-TOG3, α-tubulin and β-tubulin are colored blue, yellow and orange, respectively. A conserved residue in HR5, R830, can make a contact with the side chain of E414 in α-tubulin. The side chain of E414 in the crystal structure is colored yellow, and the same residue in the hypothetical model is shown in magenta. The nitrogen and oxygen atoms in the side chain are colored blue and red, respectively. The orientation is related to that in the right panel of (c) by a 90° rotation about a horizontal axis (Supplementary Fig. S6). (d–g) (left) SDS-PAGE of tubulin co-sedimentation assays with TOGs. Vinblastine-treated tubulin (d), soblidotin ring (e), tubulin with 0.1 mM GTP (f) and taxol-stabilized MTs (g), without TOG, with hC2-TOG2, hC2-TOG3 and Stu2-TOG1 are shown. S, supernatant; P, pellet. Without tubulin, all TOG domains were not sedimented (Supplementary Fig. S7). (d, e and g) (right) Quantification of MT co-sedimentation assays. Error bars represent standard deviations (n = 3).

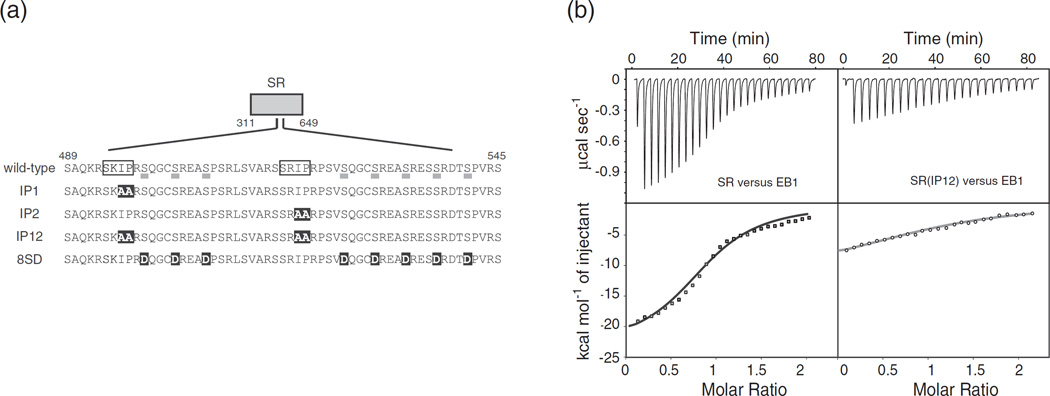

Single IP motif is sufficient for CLASP interaction with EB1

EB1 binds CLASP2 both in vivo and in vitro via the SxIP motifs, and this EB1 association is sufficient for CLASP2 targeting to MT plus-ends [26,36]. To determine the stoichiometry of binding between EB1 and CLASP2, we used isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) and measured the binding affinity between EB1 and the SR region of CLASP2 (residues 311–648) (Fig. 7a). The ITC results showed that two SR regions bind to one EB1 dimer with a Kd value of ~2 µM at 0.15 M KCl (Table 2 and Fig. 7b), suggesting that CLASP2 and EB1 form a 1:1 heterotetramer. Neither the presence of TOG (TOG2-SR and SR-TOG3) nor the disruption of either SxIP motif [mutating SxIP to SxAA; SR(IP1) and SR(IP2)] significantly influenced the binding affinity. When both motifs were mutated [SR(IP12)], however, no interaction occurred. These results indicate that SR is fully competent to bind to EB1 and that only one SxIP motif is required for the interaction, which is consistent with the previous glutathione S-transferase pull-down assay [36]. Because CLASP2 is a substrate of GSK3 and its phosphorylation influences MT dynamics, we generated a phospho-mimicking mutant by substituting eight serine residues with glutamate [SR(8SD)] and measured the binding affinity of this mutant for EB1 [23]. SR(8SD) had a reduced affinity for EB1, with Kd of 6.6 µM at the same molar ratio, and the interaction was dependent on the salt concentration. This result is consistent with a previous study showing that the electrostatic interactions partly govern the association between CLASP2 and EB1 [26].

Fig. 7.

CLASP2 interacts with EB1. (a) EB1-binding region of CLASP2. Two SxIP motifs are boxed. The eight serine residues underlined are GSK3 phosphorylation sites [23]. IP1, IP2 and IP12 indicate the alanine-substitution mutations introduced in this study. 8SD indicates the phosphorylation mimicking mutations. Mutated residues are highlighted in black. (b) ITC data for titration of EB1 into SR and SR(IP12). (top) Raw data; (bottom) integrated heat changes, corrected for the heat of dilution, and the fitted curve based on a single-site binding model.

Table 2.

Equilibrium dissociation constants obtained by ITC

| CLASP2 mutants |

Binding stoichiometry (CLASP2 versus EB1 dimer) |

Kd (µM) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| EB1 (0.15 M KCl) | SR | 2.0 | 2.0 ± 0.4 |

| SR(IP1) | 2.2 | 1.9 ± 0.5 | |

| SR(IP2) | 2.2 | 1.8 ± 0.2 | |

| SR(IP12) | n.d. | >20 | |

| SR(8SD) | 2.2 | 6.6 ±1.7 | |

| TOG2-SR | 2.2 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | |

| SR-TOG3 | 2.0 | 1.2 ± 0.2 | |

| EB1 (0.2 M KCl) | SR | 2.0 | 3.0 ± 0.4 |

| SR(8SD) | n.d. | >20 |

Equilibrium dissociation constants (Kd) and binding stoichiometry are shown. n.d. = not determined.

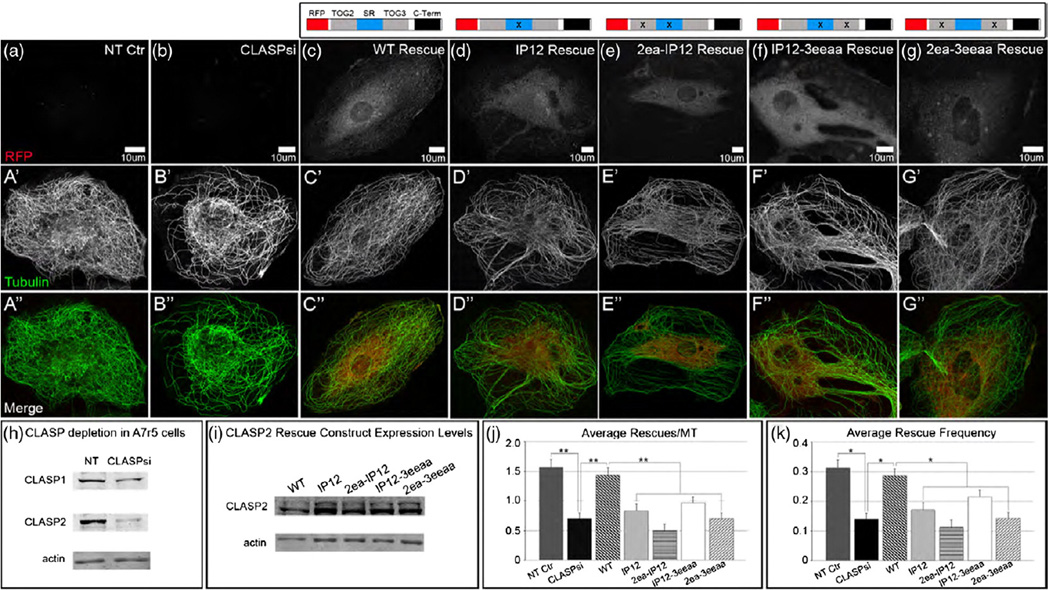

Both TOG domains and EB1 association are required for MT dynamics in vivo

To investigate the contributions of the TOG domains and EB1 binding to the CLASP2 function in vivo, we analyzed MT dynamics mediated by CLASP2 and its mutants. Parameters of MT dynamic instability were measured in CLASP-depleted A7r5 cells (siRNA against CLASP1 and CLASP2) rescued by expression of various CLASP2 mutant constructs (Table 3). Previously, it has been demonstrated that CLASP1 and CLASP2 play redundant roles in MT stabilization and that partial depletion of both CLASPs can be rescued by expression of CLASP2 alone [20]. Here, depletion of CLASPs reduced the rescue frequency down to 45% of control frequency. When wild-type CLASP2 fused to the red fluorescent protein (RFP-CLASP2) was re-introduced, the rescue frequency was restored to more than 90% of the level in control cells treated with non-targeted siRNA (Fig. 8c, j and k). CLASP depletion followed by the introduction of various CLASP2 mutant constructs exerted its most notable effect on rescue events, proving that CLASPs act as rescue factors in the regulation of MT dynamic instability. Failure of EB1 to associate with CLASP2(IP12) decreased the rescue frequency to the level of ~60% of wild type’s (Fig. 8j and k). A severe defect was also observed when multiple mutations were introduced in both TOGs [CLASP2(2ea-3eeaa)], with a tendency for lower rescue frequency. Since malfunctioning TOG domains (TOG2ea-3eeaa) did not affect EB1 binding to CLASP2 (Supplementary Fig. S8), this result implies that stable association with MTs through TOGs and plus-end accumulation with EB1 have an impact on MT rescue. Next, to compare the contribution of each TOG domain to MT dynamics, we expressed mutants in which either of the TOGs and both of the two SxIP motifs were mutated (Fig. 8e and f). Intriguingly, expression of CLASP2(2ea-IP12) and CLASP2(I-P12-3eeaa) exerted different effects on rescue frequency when compared to the IP12 mutations alone: addition of the TOG2 mutations resulted in an ~35% decrease in rescue frequency relative to CLASP2(IP12), whereas the TOG3 mutations had a smaller effect. This result clearly indicates that TOG2 is more critical for the rescue activity of CLASP2, consistent with the in vitro MT assembly study of CLASP1 and our previous in vivo study of CLASP2 [37,38].

Table 3.

MT dynamic parameters in A7r5 cells

| Number of observations |

Rescue events/MT |

Rescue frequency (per MT/min) |

Catastrophe events/MT |

Catastrophe frequency (per MT/min) |

Pause events/MT |

Pause to catastrophe events/MT |

Growth rate (µm/min) |

Shrink rate (µm/min) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NT control | 30 MTs, 10 cells | 1.57 ± 0.13 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 1.67 ± 0.12 | 0.33 ± 0.02 | 7.40 ± 0.35 | 2.77 ± 0.23 | 10.65 ± 0.32 | 14.32 ± 0.43 |

| CLASP depletion (CLASPsi) | 30 MTs, 10 cells | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 0.14 ± 0.10 | 0.70 ± 0.13 | 0.22 ± 0.03 | 6.70 ± 0.38 | 2.73 ± 0.36 | 11.20 ± 0.38 | 14.70 ± 0.42 |

| CLASP2 rescue experiments in CLASP-depleted cells | |||||||||

| RFP-(wild type) | 30 MTs, 8 cells | 1.43 ± 0.12 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 1.13 ± 0.13 | 0.23 ± 0.03 | 7.03 ± 0.39 | 3.37 ± 0.45 | 10.44 ± 0.43 | 15.11 ± 0.33 |

| RFP-(IP12) | 30 MTs, 6 cells | 0.83 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 1.00 ± 0.14 | 0.21 ± 0.03 | 6.07 ± 0.40 | 3.20 ± 0.34 | 10.90 ± 0.57 | 15.11 ± 0.37 |

| RFP-(2ea-IP12) | 30 MTs, 5 cells | 0.54 ± 0.10 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 0.75 ± 0.13 | 0.18 ± 0.04 | 5.71 ± 0.41 | 3.54 ± 0.45 | 11.06 ± 0.58 | 13.87 ± 0.36 |

| RFP-(IP12-3eeaa) | 30 MTs, 6 cells | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 0.21 ± 0.02 | 1.03 ± 0.09 | 0.25 ± 0.03 | 5.77 ± 0.33 | 2.73 ± 0.33 | 12.61 ± 0.52 | 18.41 ± 0.52 |

| RFP-(2ea-3eeaa) | 30 MTs, 8 cells | 0.70 ± 0.10 | 0.14 ± 0.02 | 0.80 ± 0.12 | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 5.93 ± 0.47 | 3.73 ± 0.48 | 12.49 ± 0.54 | 15.34 ± 0.47 |

MT dynamic parameters were determined by live-cell imaging in cells expressing 3x GFP-EMTB to visualize the MT network and are presented as means ± SEM. The number of MTs analyzed (n) per condition is indicated. Frequency measurements are in events MT−1 min−1, while growth and shrinkage rates are in micrometers per minute (µm/min). All parameters listed above are averages calculated over three independent experiments with 10 MTs each for a total of 30 MTs.

Fig. 8.

MT network organization requires CLASP MT binding and EB binding. (a–g″) A7r5 cells expressing CLASP2 mutants (a–g, grayscale; a″–g″, red), immunostained for tubulin (a’–g’, grayscale; a″–g″, green). Confocal stack maximum intensity projections. N-terminally tagged RFP-CLASP2 rescue constructs with mutations in either TOGs and/or the EB-binding region. (a–a″) NT control cells have a highly organized and dense MT network when CLASPs are present. (b–b″) MT network is hindered and random in CLASP-depleted A7r5 cells (CLASPsi = mixture of siRNAs against CLASP1 and CLASP2). (c–c″) MT network organization and density is restored in CLASP-depleted cells expressing a non-silenceable RFP-fused wild-type (WT) CLASP2 rescue construct. (d–g″) CLASP-depleted cells expressing mutant versions of CLASP2 have MT network organization resembling that of CLASP-depleted cells, indicating a lack of rescue in the absence of EB and/or MT binding. (h) Western blot showing reduction of CLASP1 and CLASP2 levels in A7r5 cells treated for 72 h with a mixture of siRNAs against both CLASPs. (i) Western blot showing levels of endogenous CLASP2 (bottom band) and expression of RFP-CLASP2 constructs (top band) in untreated A7r5 stable lentiviral lines. In (h) and (i), actin was used as a loading control. (j and k) Analysis of average rescues per MT (j) and average rescue frequency per MT per minute (k) in NT control, CLASPsi and CLASP-depleted A7r5 cells expressing the respective RFP-CLASP2 rescue constructs (n = 30 for all conditions, three independent experiments, **p < 0.005 (j), *p < 0.05 (k), unpaired Student’s t-test).

Discussion

In this study, we determined the crystal structures of CLASP2 TOG domains and built structural models of tubulin recognition using previously solved structures of tubulin in various states. We propose that TOGs require not only the basic surface to bind tubulin but also the unique curvature of the paddle structure to discriminate the molecular state of tubulin. By varying the arched conformation, CLASP2-TOGs lose the ability to associate with the unpolymerized tubulin dimer but may become capable of associating with other states of MTs, particularly with flexible protofilaments of high curvature or with tubulin spirals, in order to promote MT pause or rescue. Our current result shows a distinct difference between human CLASP-TOGs and TOG2 from Drosophila CLASP homolog MAST in MT polymerization rate in vitro [15]. MAST-TOG2 shares ~ 40% sequence identity with hC2-TOG2, suggesting that the subtle differences between TOGs may influence tubulin binding. In our molecular modeling, mC2-TOG3 fits the surface of curved-sheared tubulin in the depolymerizing state, and our biochemical analyses showed that hC2-TOG3 had more affinity for vinblastine-tubulin than for soblidotin rings. On the other hand, hC2-TOG2 associated efficiently with soblidotin rings whose higher curvature is caused by soblidotin binding to tubulin in an inter-dimer manner. The tubulin-binding surface of hC2-TOG2 is convex but not curved perpendicularly, suggesting that hC2-TOG2 has a different binding mode to interact with tubulin and possibly stabilizes the protofilaments by binding two longitudinally associated tubulin dimers. At this point, it is plausible to assume that both TOGs have a greater affinity for peeling protofilaments at plus-ends because the protofilaments in disassembling MTs may have increased structural flexibility between the tubulin dimers due to a loss of lateral contact during the structural transition from assembled MT to protofilaments. Although the medium resolution cryo-EM structural model of tubulin was used for TOG:αβ-tubulin in the depolymerizing state in this study, we believe that CLASP2-TOGs possibly form a complex with curved-sheared tubulin in a peeling protofilament, stabilize the protofilament configuration and promote rescue events because tubulin with various curvature exists in depolymerizing proto-filaments of MTs [39].

Because of the bent structures of CLASP-TOGs, our structural analyses and the previous hC1-TOG2 study have implied that CLASP-TOGs may not associate with tubulin in the straight form. In vivo and in vitro observations, however, indicate that the CLASP-TOG domains bind to the MT lattice. Tandem TOG2 and TOG3 may simultaneously bind the MT lattice by enhancing the affinity of individual tubulin-binding sites. Furthermore, SR provides an additional MT interaction site to stabilize the CLASP association with the MT lattice. Like other TOG-containing proteins, the multiple TOG domains of CLASP2 may suppress catastrophe and promote rescue by increasing CLASP affinity for MTs. Although it remains unclear how TOGs of CLASPs are organized on MTs, given the crystal structure of the Stu2-TOG1:curved tubulin complex, TOG2 likely binds to the tip of the plus-end, whereas TOG3 stays instead on the body of the filament due to the polarized αβ-tubulin structure. These observations raise the following questions: (1) Do the two TOG domains associate with the same or different protofilaments? (2) Do they stabilize the MT filaments independently or cooperatively? (3) Is EB1 necessary to place TOGs properly on MTs? It should be noted that two TOG domains of Stu2 bind tubulin dimers non-cooperatively: while one TOG domain associates with the MT plus-end, another TOG domain may deliver an unpolymerized αβ-tubulin; thus, Stu2 catalyzes the MT polymerization reaction efficiently [40]. Further biochemical analysis is required to resolve these questions regarding tubulin recognition by CLASP-TOGs and the molecular state of tubulin.

Materials and Methods

Cloning, expression and protein purification

Human CLASP2 TOG2 (hC2-TOG2; residues 60–311), human and murine CLASP2 TOG3 (hC2- and mC2-TOG3; residues 649–881 and 642–873, respectively) and budding yeast Stu2-TOG1 (residues 1–250) were cloned into the NdeI/NotI sites of a modified pET15b vector (Novagen) containing a TEV (tobacco etch virus) protease cleavage site. All proteins were expressed in E. coli strain BL21(DE3). Histidine-tagged proteins were purified with Ni-NTA Superflow (Qiagen) and digested with the recombinant TEV protease [41]. hC2-TOG2, mC2-TOG3 and Stu2-TOG1 were further purified using Superdex200, HiTrapSP and HiTrapQ (GE Healthcare), respectively, and used for crystallographic and/or biochemical analyses. Human CLASP2 deletion mutants [SR(311–648) and TOG2-3(60–881)] were subcloned into pET21a without stop codon, expressed as C-terminally histidine-tagged proteins and purified using Ni-NTA Superflow, followed by HiTrapSP. Amino acid mutations were introduced by site-directed PCR mutagenesis. For all constructs, the absence of errors was confirmed by DNA sequencing. Mutants of hC2-TOG2 and hC2-TOG3 were correctly folded, as judged by circular dichroism spectroscopy (data not shown). The selenomethionine-substituted hC2-TOG2 and mC2-TOG3 were expressed in BL21(DE3) as described previously [42] and purified in the same manner as the wild-type proteins. Both proteins were concentrated to 30 mg/ml in 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 0.15 M NaCl and 1 mM DTT for crystallization. EB1 was prepared as described previously [43].

Crystallization and structure determination

Crystals of hC2-TOG2 were obtained by hanging-drop vapor diffusion at 20 °C with reservoir solution containing 0.1 M Tris (pH 8.5) and 3% polyethylene glycol 10,000. Crystals were cryo-protected with 25% ethylene glycol in the mother liquor. mC2-TOG3 was micro-dialyzed against 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NaCl and 2 mM DTT at 4 °C and crystallized using the salting-out method. Crystals were soaked in 25% glycerol and frozen in liquid nitrogen.

For both hC2-TOG2 and mC2-TOG3, data processing and reduction were carried out using the HKL2000 program suite [44]. The initial phases were obtained by Se-MAD with the SOLVE program [45]. Phases were improved using RESOLVE [46]. The initial model was built with ARP/wARP [47]. Manual rebuilding was performed with Coot [48], followed by iterative rounds of refinement using simulated annealing and positional refinement in CNS [49]. Figures were generated using PyMOL [50].

Tubulin polymerization assay

Tubulin was isolated from porcine brain and labeled with rhodamine (Rh-tubulin) as described previously [51]. Tubulin polymerization with the TOG domains was measured at 360 nm as light scattering using a JASCO V-630BIO UV/VIS photometer in 30-s intervals at 37 °C. The reaction was initiated by adding 15 µl of a 100 µM purified tubulin solution to a final 100 µl of a buffer containing 2.5 µM of hC2-TOG2, hC3-TOG3 or Stu2-TOG1 in PMEM buffer [20 mM Pipes, 20 mM 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid, 2 mM ethylene glycol bis(β-aminoethyl ether) N,N′-tetraacetic acid and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.8] supplemented with 0.15 M KCl, 3.4 M glycerol and 0.2 mM GTP. After 30 min, the temperature was shifted to 10 °C to see cold disassembly of MTs. For microscopic analyses, ~6% Rh-tubulin was added to unlabeled tubulin. After 30 min of reactions, MTs were fixed in 1% glutaraldehyde, pelleted onto coverslips [1] and viewed on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope. Images were captured using a DS-QiMc CCD camera (Nikon) with the NIS-Element software (Nikon).

Visualization of CLASP2 binding to MTs or tubulin in vitro

Tubulin (25 µM; 6% Rh-tubulin) was polymerized for 10 min at 37 °C in PMEM buffer with 0.15 M KCl, 0.1 mM GTP and 10 µM taxol. Tubulin was diluted to 1 µM and incubated for another 3 min with 25 nM GFP-TOG2-3 or GFP-TOG2ea-3eeaa. The mixture of the two proteins was placed on a microscope slide and visualized on a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope. Images were processed using the ImageJ software.

For the polymerized tubulin and TOG2-3 binding assay, 0.13–4.0 µM taxol-stabilized MTs and 0.25 µM TOG2-3 were mixed and incubated for 1 min. All samples were layered onto a glycerol cushion buffer (PMEM, 0.15 M KCl and 30% glycerol) and centrifuged for 5 min at 37 °C at 50,000 rpm, in a TLA100.3 rotor on an Optima TLX ultracentrifuge (Beckman). The pellet fractions were resuspended in PMEM buffer and analyzed by SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue and gel images were analyzed using a LAS 4000 image analyzer (GE Healthcare). Protein bands were quantitated using the MultiGauge software (GE Healthcare). In this saturation binding experiment, the data points were fitted to the one-site specific binding model using GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software).

To generate vinblastine-bound tubulin, we incubated 30 µM tubulin with 1 mM vinblastine sulfate (Wako) in PMEM buffer supplemented with 5% (w/v) sucrose at room temperature for 3 h. For taxol-stabilized MTs, 0.2 mM taxol was mixed with 30 µM tubulin in PMEM buffer at 37 °C. We mixed 6 µM vinblastine-bound tubulin or taxol-stabilized MTs with 3 µM TOGs in PMEM buffer with 0.15 M KCl. After 10 min incubation at room temperature, the mixture was layered onto a cushion buffer, centrifuged for 15 min at 70,000 rpm in a TLA100.3 rotor and analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Soblidotin-bound tubulin protofilaments were prepared by incubating 30 µM tubulin with 50 µM soblidotin (gift from ASKA Pharmaceutical), 5% DMSO and 0.1 mM GTP in PMEM buffer. We mixed 3 µM TOGs with soblidotin-bound protofilaments for 10 min at room temperature. The mixture was then centrifuged for 20 min at 100,000 rpm without a cushion buffer and analyzed. For drug-free tubulin pelleting experiments, 30 µM tubulin was incubated with 0.1 mM GTP at room temperature. Mixtures of TOGs and tubulin were prepared and analyzed in the same manner as the case of soblidotin-bound protofilaments.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

ITC experiments were performed using a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal Inc.) at 25 °C in PMEM buffer supplemented with 0.15 M KCl and 5% glycerol. A typical experiment involved an initial 2-µl injection, followed by 26× 10-µl injections of 100 µM dimeric EB1 to solution containing 20 µM CLASP2 constructs. Data were analyzed using the Origin 7.0 software and fitted to a “one set of sites” binding model to determine the binding stoichiometry and the equilibrium binding constant (Kd). The experiments were repeated at least three times.

Gel-filtration analysis

We mixed 5 µM of the TOG domain with 2 µM tubulin and incubated it in PMEM buffer with 0.15 M KCl at 4 °C for 10 min. The mixture was then analyzed by size-exclusion chromatography using a Superdex200 10/300 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare), equilibrated with PMEM buffer with 0.15 M KCl. We collected and analyzed 0.5 ml elution fractions on SDS-PAGE.

Cells, siRNA and expression constructs

A mixture of mixed siRNA oligonucleotides against CLASP1 and CLASP2 [20] was transfected into A7r5 rat smooth muscle cells (ATCC) using HiPerFect (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol: CLASP1 siRNA targeted sequence: 5′-CGGGAUUGCAUCUUUGAAA-3′; CLASP2 siRNA targeted sequence: 5′-CUGAUAGUGU CUGUUGGUU-3′. Experiments were conducted 72 h after transfection as, at this time, minimal protein levels were detected. Non-targeting siRNA (Dharmacon) was used as a control. We used 3× GFP-EMTB for visualization of the MT network [6]. RFP-fused CLASP2 (residues 60–1294) and its mutants were subcloned into the NheI/NotI sites of CSII-CMV-MCS lentiviral vector (RIKEN BioResource Center).

Antibodies and immunofluorescence

For immunofluorescence, MTs were stained with a mouse monoclonal antibody against α-tubulin (DM 1A) and Alexa488-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG was used as the secondary antibody (Invitrogen).

Western blot analysis

A mouse polyclonal antibody against actin (pan-Ab-5; Thermo Scientific), a custom rabbit polyclonal antibody against CLASP2 (VU-83) that has been described previously [6] and a rabbit polyclonal antibody against CLASP1 (Epitomics) were used.

Transfection, lentiviral infection and stable lines

Fugene6 (Roche) and HiPerFect (Qiagen) were used according to the manufacturer’s protocols, for transfection of plasmid DNA and siRNA oligonucleotide, respectively. For viral infection, supernatant containing lentiviral particles was collected from HEK293T cells transfected with the lentiviral expression vectors and second-generation packaging constructs (Invitrogen). A7r5 cells were infected overnight with supernatant containing lentiviral particles in the presence of 8 mg/ml Polybrene.

Microscopy

Single-plane confocal live-cell video was taken using a Yokogawa QLC-100/CSU-10 spinning disk head (Visitec assembled by Vashaw) attached to a Nikon TE2000E microscope equipped with a Perfect Focus System using a CFI PLAN APO VC 100× oil lens NA 1.4 and a back-illuminated EM-CCD camera Cascade 512B (Photometrics) driven by the IPLab software (Scanalytics). For immunofluorescence imaging, a Leica TCS SP5 confocal laser scanning microscope with an HCX PL APO 100× oil lens NA 1.47 was used to take confocal stacks of fixed cells. To analyze MT dynamic parameters in NT control cells, CLASP-depleted cells and CLASP-depleted cells expressing RFP-CLASP2 rescue constructs, we used 5-min single-channel spinning disk confocal sequences (3 s/frame) of cells expressing 3× GFP-EMTB. Individual MTs were manually tracked using the MTrackJ plugin of ImageJ. Thirty MTs were analyzed over 3 days of experiments, with multiple cells analyzed per day. Average numbers of events (rescue, catastrophe and pause) were manually calculated per MT; these values were then used to calculate the frequency (rescue and catastrophe) (MT−1 min−1). Average MT growth and shrinkage rates were calculated from instantaneous velocity measurements.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the beamline staff at BL5A and BL6A of Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan) for help with data collection. We also thank A. Akhmanova for the full-length human CLASP2 cDNA and ASKA Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. for soblidotin. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research 22570190, the Astellas Foundation for Research on Metabolic Disorders, the Takeda Science Foundation (to I.H.), National Institutes of Health grant GM078373, American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 13GRNT16980096 (to I.K.) and American Heart Association Pre-Doctoral Fellowship 12PRE12040153 (to A.D.G.).

Abbreviations used

- MT

microtubule

- GSK3

glycogen synthase kinase 3

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- EM

electron microscopy

- ITC

isothermal titration calorimetry

Footnotes

Accession numbers

The coordinates for the hC2-TOG2 and mC2-TOG3 of CLASP2 structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank under ID codes 3WOY and 3WOZ, respectively.

Appendix A. Supplementary Data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2015.05.012.

References

- 1.Mitchison T, Kirschner M. Dynamic instability of microtubule growth. Nature. 1984;312:237–242. doi: 10.1038/312237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Desai A, Mitchison TJ. Microtubule polymerization dynamics. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1997;13:83–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.13.1.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akhmanova A, Steinmetz MO. Tracking the ends: a dynamic protein network controls the fate of microtubule tips. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:309–322. doi: 10.1038/nrm2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maiato H, Fairley EA, Rieder CL, Swedlow JR, Sunkel CE, Earnshaw WC. Human CLASP1 is an outer kinetochore component that regulates spindle microtubule dynamics. Cell. 2003;113:891–904. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00465-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bratman SV, Chang F. Stabilization of overlapping microtubules by fission yeast CLASP. Dev Cell. 2007;13:812–827. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Efimov A, Kharitonov A, Efimova N, Loncarek J, Miller PM, Andreyeva N, et al. Asymmetric CLASP-dependent nucleation of noncentrosomal microtubules at the trans-Golgi network. Dev Cell. 2007;12:917–930. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Akhmanova A, Hoogenraad CC, Drabek K, Stepanova T, Dortland B, Verkerk T, et al. Clasps are CLIP-115 and −170 associating proteins involved in the regional regulation of microtubule dynamics in motile fibroblasts. Cell. 2001;104:923–935. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00288-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charrasse S, Schroeder M, Gauthier-Rouviere C, Ango F, Cassimeris L, Gard DL, et al. The TOGp protein is a new human microtubule-associated protein homologous to the Xenopus XMAP215. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:1371–1383. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.10.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brouhard GJ, Stear JH, Noetzel TL, Al-Bassam J, Kinoshita K, Harrison SC, et al. XMAP215 is a processive microtubule polymerase. Cell. 2008;132:79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.11.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Bassam J, Larsen NA, Hyman AA, Harrison SC. Crystal structure of a TOG domain: conserved features of XMAP215/ Dis1-family TOG domains and implications for tubulin binding. Structure. 2007;15:355–362. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slep KC, Vale RD. Structural basis of microtubule plus end tracking by XMAP215, CLIP-170, and EB1. Mol Cell. 2007;27:976–991. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Bassam J, Chang F. Regulation of microtubule dynamics by TOG-domain proteins XMAP215/Dis1 and CLASP. Trends Cell Biol. 2011;21:604–614. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ayaz P, Ye X, Huddleston P, Brautigam CA, Rice LM. A TOG:αβ-tubulin complex structure reveals conformation-based mechanisms for a microtubule polymerase. Science. 2012;337:857–860. doi: 10.1126/science.1221698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Slep KC. The role of TOG domains in microtubule plus end dynamics. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:1002–1006. doi: 10.1042/BST0371002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leano JB, Rogers SL, Slep KC. A cryptic TOG domain with a distinct architecture underlies CLASP-dependent bipolar spindle formation. Structure. 2013;21:939–950. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wittmann T, Waterman-Storer CM. Spatial regulation of CLASP affinity for microtubules by Rac1 and GSK3beta in migrating epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:929–939. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200412114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tournebize R, Popov A, Kinoshita K, Ashford AJ, Rybina S, Pozniakovsky A, et al. Control of microtubule dynamics by the antagonistic activities of XMAP215 and XKCM1 in Xenopus egg extracts. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:13–19. doi: 10.1038/71330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widlund PO, Stear JH, Pozniakovsky A, Zanic M, Reber S, Brouhard GJ, et al. XMAP215 polymerase activity is built by combining multiple tubulin-binding TOG domains and a basic lattice-binding region. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:2741–2746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016498108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Bassam J, Kim H, Brouhard G, van Oijen A, Harrison SC, Chang F. CLASP promotes microtubule rescue by recruiting tubulin dimers to the microtubule. Dev Cell. 2010;19:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Grigoriev I, Lansbergen G, Sasaki H, Matsui C, Severin F, et al. CLASP1 and CLASP2 bind to EB1 and regulate microtubule plus-end dynamics at the cell cortex. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:141–153. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200405094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Inoue YH, do Carmo Avides M, Shiraki M, Deak P, Yamaguchi M, Nishimoto Y, et al. Orbit, a novel microtubule-associated protein essential for mitosis in Drosophila melanogaster . J Cell Biol. 2000;149:153–166. doi: 10.1083/jcb.149.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lemos CL, Sampaio P, Maiato H, Costa M, Omel’yanchuk LV, Liberal V, et al. Mast, a conserved microtubule-associated protein required for bipolar mitotic spindle organization. EMBO J. 2000;19:3668–3682. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.14.3668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumar P, Lyle KS, Gierke S, Matov A, Danuser G, Wittmann T. GSK3beta phosphorylation modulates CLASP-microtubule association and lamella microtubule attachment. J Cell Biol. 2009;184:895–908. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watanabe T, Noritake J, Kakeno M, Matsui T, Harada T, Wang S, et al. Phosphorylation of CLASP2 by GSK-3beta regulates its interaction with IQGAP1, EB1 and microtubules. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2969–2979. doi: 10.1242/jcs.046649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoogenraad CC, Akhmanova A, Grosveld F, De Zeeuw CI, Galjart N. Functional analysis of CLIP-115 and its binding to microtubules. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:2285–2297. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.12.2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kumar P, Chimenti MS, Pemble H, Schonichen A, Thompson O, Jacobson MP, et al. Multisite phosphorylation disrupts arginine-glutamate salt bridge networks required for binding of cytoplasmic linker-associated protein 2 (CLASP2) to end-binding protein 1 (EB1) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:17050–17064. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.316661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Buey RM, Sen I, Kortt O, Mohan R, Gfeller D, Veprintsev D, et al. Sequence determinants of a microtubule tip localization signal (MtLS) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:28227–28242. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.373928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Podolski M, Mahamdeh M, Howard J. Stu2, the budding yeast XMAP215/Dis1 homolog, promotes assembly of yeast microtubules by increasing growth rate and decreasing catastrophe frequency. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:28087–28093. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.584300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Löwe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of αβ-tubulin at 3.5 Å resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ravelli RB, Gigant B, Curmi PA, Jourdain I, Lachkar S, Sobel A, et al. Insight into tubulin regulation from a complex with colchicine and a stathmin-like domain. Nature. 2004;428:198–202. doi: 10.1038/nature02393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Asenjo AB, Chatterjee C, Tan D, DePaoli V, Rice WJ, Diaz-Avalos R, et al. Structural model for tubulin recognition and deformation by kinesin-13 microtubule depolymerases. Cell Rep. 2013;3:759–768. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jordan MA, Margolis RL, Himes RH, Wilson L. Identification of a distinct class of vinblastine binding sites on microtubules. J Mol Biol. 1986;187:61–73. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90406-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gigant B, Wang C, Ravelli RB, Roussi F, Steinmetz MO, Curmi PA, et al. Structural basis for the regulation of tubulin by vinblastine. Nature. 2005;435:519–522. doi: 10.1038/nature03566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moores CA, Milligan RA. Visualisation of a kinesin-13 motor on microtubule end mimics. J Mol Biol. 2008;377:647–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cormier A, Marchand M, Ravelli RB, Knossow M, Gigant B. Structural insight into the inhibition of tubulin by vinca domain peptide ligands. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:1101–1106. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Honnappa S, Gouveia SM, Weisbrich A, Damberger FF, Bhavesh NS, Jawhari H, et al. An EB1-binding motif acts as a microtubule tip localization signal. Cell. 2009;138:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel K, Nogales E, Heald R. Multiple domains of human CLASP contribute to microtubule dynamics and organization in vitro and in Xenopus egg extracts. Cytoskeleton (Hoboken) 2012;69:155–165. doi: 10.1002/cm.21005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Grimaldi AD, Maki T, Fitton BP, Roth D, Yampolsky D, Davidson MW, et al. CLASPs are required for proper microtubule localization of end-binding proteins. Dev Cell. 2014;30:343–352. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2014.06.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nogales E, Wang HW. Structural intermediates in microtubule assembly and disassembly: how and why? Curr Opin Struct Biol. 2006;18:179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ayaz P, Munyoki S, Geyer EA, Piedra FA, Vu ES, Bromberg R, et al. A tethered delivery mechanism explains the catalytic action of a microtubule polymerase. eLife. 2014;3:03069. doi: 10.7554/eLife.03069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blommel PG, Fox BG. A combined approach to improving large-scale production of tobacco etch virus protease. Protein Expr Purif. 2007;55:53–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Duyne GD, Standaert RF, Karplus PA, Schreiber SL, Clardy J. Atomic structures of the human immunophilin FKBP-12 complexes with FK506 and rapamycin. J Mol Biol. 1993;229:105–124. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayashi I, Wilde A, Mal TK, Ikura M. Structural basis for the activation of microtubule assembly by the EB1 and p150Glued complex. Mol Cell. 2005;19:449–460. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.06.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Terwilliger TC, Berendzen J. Automated MAD and MIR structure solution. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1999;55:849–861. doi: 10.1107/S0907444999000839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Terwilliger TC. Maximum-likelihood density modification. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2000;56:965–972. doi: 10.1107/S0907444900005072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Perrakis A, Morris R, Lamzin VS. Automated protein model building combined with iterative structure refinement. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:458–463. doi: 10.1038/8263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: a new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.2b2. Schrödinger, LLC. 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hyman A, Drechsel D, Kellogg D, Salser S, Sawin K, Steffen P, et al. Preparation of modified tubulins. Methods Enzymol. 1991;196:478–485. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)96041-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, McCammon JA. Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:10037–10041. doi: 10.1073/pnas.181342398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kabsch W, Sander C. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 1983;22:2577–2637. doi: 10.1002/bip.360221211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.