Abstract

The Korean Society of Hypertension published new guidelines for the management of hypertension in 2013 which fully revised the first Korean hypertension treatment guideline published in 2004. Due to shortage of Korean data, the Committee decided to establish the guideline in the form of an ‘adaptation’ of the recently released guidelines. The prevalence of hypertension was 28.5% in the recent Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey in 2011, and the awareness, treatment, and control rates are generally improving. However, the risks for cerebrovascular disease and coronary artery disease which are attributable to hypertension were the highest in Korea. The classification of hypertension is the same as in other guidelines. The remarkable difference is that prehypertension is further classified as stage 1 and 2 prehypertension because the cardiovascular risk is significantly different within the prehypertensive range. Although the decision-making was based on office blood pressure (BP) measured by the auscultation method using a stethoscope, the importance of home BP measurement and ambulatory BP monitoring is also stressed. The Korean guideline does not recommend a drug therapy in patients within the prehypertensive range, even in patients with prediabetes, diabetes mellitus, stroke, or coronary artery disease. In an elderly population over 65 years old, drug therapy can be initiated when the systolic BP (SBP) is ≥160 mm Hg. The target BP is generally an SBP of <140 mm Hg and a diastolic BP (DBP) of <90 mm Hg regardless of previous cardiovascular events. However, in patients with hypertension and diabetes, the lower DBP control <85 mm Hg is recommended. Also, in patients with hypertension with prominent albuminuria, a more strict SBP control <130 mm Hg can be recommended. In lifestyle modification, sodium reduction is the most important factor in Korea. Five classes of antihypertensive drugs, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β-blockers, calcium antagonists, and diuretics, are equally recommended as a first-line treatment, whereas a combination therapy chosen from renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and diuretics is preferentially recommended.

Key Words: Korean, Guidelines, Hypertension

Introduction

The Korean Society of Hypertension published new guidelines for the management of hypertension in 2013 which fully revised the first Korean hypertension treatment guideline published in 2004 [1]. A great amount of data from studies performed in Korea is needed to establish a treatment guideline perfectly tailored to our clinical practices; however, in reality, there is currently a serious shortage of available results from Korean studies. Practically speaking, it is difficult to construct an optimal guideline that physicians may apply exclusively to Korean patients. The Committee, therefore, decided to establish a guideline in the form of an ‘adaptation’ of the recently released guidelines including the guideline from the European Society of Hypertension/the European Society of Cardiology [2].

The Prevalence and Clinical Significance of Hypertension in Korea

In the Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES), the age-standardized prevalence of hypertension was approximately 30% among adults aged >30 years of age. The temporal trend of the prevalence of hypertension was 29.9 and 28.6% in 1998 and 2001, respectively. This prevalence decreased slightly in 2007 and 2008 and then increased again in 2011 [3]. Among adults aged 65 years or older, the prevalence increased between 2007 and 2011 from 49.3 to 58.4% in men and from 61.8 to 68.9% in women. The prevalence of prehypertension in 2001 was 39.8% in men and 30.6% in women and decreased slightly to 28.4% in men and 18.8% in women in 2008, similar to the trend in the prevalence of hypertension (table 1).

Table 1.

The trend in the prevalence of hypertension in the population aged >30 years (2011 National Health Statistics)

| 1980a | 1990a | 1998b | 2001b | 2005b | 2007b | 2008b | 2011b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | 29.9 | 28.6 | 28.0 | 24.6 | 26.3 | 28.5 | ||

| Male | 35.5 | 33.2 | 32.5 | 33.2 | 31.5 | 26.9 | 28.1 | 32.9 |

| Female | 26.9 | 25.4 | 26.9 | 25.4 | 23.9 | 21.8 | 23.9 | 23.7 |

The prevalence in 1980 and 1990 was based on the nationwide study for the prevalence of hypertension.

Age-adjusted for the estimated population in 2005.

The Korean Medical Insurance Corporation (KMIC) study enrolled approximately 100,000 male civil officers and private school teachers to evaluate the risk of high blood pressure (BP). The risks for cerebrovascular disease and coronary artery disease which are attributable to hypertension in men were 35 and 21%, respectively [4]. According to the KIMC study, the hazard ratio for cerebrovascular and coronary artery disease during a 6-year follow-up period was 2.6 for the hypertension group relative to the subjects with BP <130/85 mm Hg [5,6]. In addition, for each 20-mm Hg increase in systolic BP (SBP), the relative risks of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and subarachnoid hemorrhage were 1.79, 2.48, and 1.65, respectively, in men and 1.64, 3.15, and 2.29, respectively, in women [4]. Therefore, the risks of high BP for stroke and coronary artery disease in Korea have been well documented. Moreover, the risk of stroke is more clearly attributable to hypertension than that of coronary artery disease.

The awareness, treatment, and control rates are generally improving. According to the data from the KNHANES during the period from 2008 to 2011, the awareness rate was 58.5 and 76.1% among men and women aged >30 years, respectively, which was an improvement relative to the previous data (table 2). The treatment rate in 2001 was 22.2 and 37.5% in men and women, respectively, according to the in-depth report of the KNHANES 2005, which improved to 51.7 and 71.3% in men and women, respectively, in the 2008-2011 period (table 2). The control rate in 2001 was quite low at 9.9 and 18.0% in men and women, respectively. However, as of the 2008-2011 period, it had increased to 36.9 and 49.4% in men and women, respectively (table 2). Although there was no clear change in the prevalence of hypertension, the mean BP has steadily decreased, especially among patients with hypertension.

Table 2.

Trends in the management of hypertension (standardized for Census 2005, National Health Statistic)

| 1998 | 2001 | 2005 | 2008–2011 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awareness | 27.0 | 36.0 | 59.8 | 66.9 |

| Treatment rate | 19.1 | 29.3 | 47.1 | 61.1 |

| Control rate for all hypertension patients | 7.4 | 14.9 | 32.2 | 42.9 |

| Control rate for treated hypertension patients | 22.9 | 37.0 | 54.9 | 69.3 |

Values are presented as percentages. The criterion for patients with treatment of hypertension was taking antihypertensive drugs on >20 days per month.

Office BP-Centered Approach and Subdivision of the Prehypertension Category

Hypertension is defined as an SBP or a diastolic blood pressure (DBP) ≥140 or ≥90 mm Hg, respectively. Normal BP is defined only as both an SBP <120 mm Hg and a DBP <80 mm Hg. When SBP is ≥120 but <140 mm Hg and/or DBP is ≥80 but <90 mm Hg, the patient is considered to have prehypertension. The remarkable difference is that prehypertension is further classified as stage 1 and 2 prehypertension. In stage 1 prehypertension, SBP is ≥120 but <130 mm Hg and/or DBP is ≥80 but <85 mm Hg. In stage 2 prehypertension, SBP is ≥130 but <140 mm Hg and/or DBP is ≥85 but <90 mm Hg. The reason for this subdivision is that the cardiovascular risk is significantly different within the prehypertensive range. For example, in the KMIC study, the risk of coronary artery disease was 2.51-fold higher in the stage 2 prehypertension group than in the stage 1 prehypertension group [6,7]. In addition, the probability of progressing to hypertension and the risk for a cardiovascular event were both reported to be higher in the prehypertension group than in the normal BP group [8,9,10]. In another paper from the KMIC study, a BP >135/85 mm Hg was associated with the occurrence of hemorrhagic stroke in male subjects. Hypertension is further classified as stage 1 and 2 hypertension as shown in table 3.

Table 3.

The classification of BP and hypertension

| Category | SBP, mm Hg | DBP, mm Hg | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal BP | <120 | and | <80 | |

| Prehypertension | stage 1 | 120–129 | or | 80–84 |

| stage 2 | 130–139 | or | 85 – 89 | |

| Hypertension | stage 1 | 140 – 159 | or | 90 – 99 |

| stage 2 | 160 | or | 100 | |

| Isolated systolic hypertension | 140 | and | <90 | |

The decision-making in the Korean guideline of hypertension was based on the office BP measured by the auscultation method using a stethoscope. However, the guideline also stressed the importance of home BP measurement and ambulatory BP monitoring to diagnose white-coat hypertension, masked hypertension, and resistant hypertension, to titrate the dosage of antihypertensive drugs, and to improve the patient compliance [11]. Hypertension can be diagnosed when home BP or mean daytime BP is ≥135/85 mm Hg (table 4). When making a diagnosis of hypertension based on home BP measurement, it is recommended to measure at least on 5 consecutive days in a week and to perform 1-3 measurements in each session in the morning and evening. In the morning, BP is measured after voiding, within 1 h of awakening, and before taking antihypertensive drugs. In the evening, it is measured before sleep. When calculating the mean BP, the readings on the first day are usually omitted.

Table 4.

Criteria for the definition of hypertension with different methods of measurement

| SBP, mm Hg | DBP, mm Hg | |

|---|---|---|

| Clinic or office BP | ≥140 | ≥90 |

| Ambulatory BP | ||

| 24-hour | ≥130 | ≥80 |

| Day | ≥135 | ≥85 |

| Night | ≥120 | ≥70 |

| Home BP | ≥135 | ≥85 |

In ‘out-of-office’ BP measurement, white-coat hypertension and masked hypertension need to be considered. The KorABP registry in secondary or tertiary referral centers supported by the Korean Society of Hypertension reported that 14.9% of patients were found to have white-coat hypertension, and masked hypertension was observed in 17.6% of 1,916 subjects who underwent ambulatory BP monitoring for the diagnosis of hypertension [12].

Comprehensive Risk Stratification for Hypertension Care

The risk stratification of hypertension was based on the KMIC data, which were drawn from patients with the following characteristics: (1) registered in the early 1990s; (2) relatively young age range of 35-59 years, and (3) relatively high socioeconomic status [13]. The lowest risk for a cardiovascular event in the KMIC data was 2-3 or 2.5% among the patients in their 40s. According to the guidelines presenting risk group by cardiovascular event rates [14,15], the average-risk group included those patients with a risk approximately 2-fold higher than that of the lowest-risk group, corresponding to a 10-year cardiovascular event rate of 5%. The moderate added-risk group was defined as the patients with a risk ≥2-fold higher than that of the average-risk group, i.e. a 10-year cardiovascular event rate of ≥10%. The high added-risk group was defined as the group with a risk ≥2-fold higher than that of the moderate added-risk group, i.e. a 10-year cardiovascular event rate of ≥20%. Therefore, the 10-year cardiovascular event rates for the lowest-, average-, low added-, moderate added-, and high added-(including the highest added-) risk groups were 2.5, 5, 5-10, 10-15, and ≥15%, respectively, after consideration of the potential underestimation; these levels correspond to the cardiovascular event rates of 2.5, 5, 5-15, 15-20, and 20% in the European guidelines [14,15,16]. Patients with stage 1 hypertension who are in their 40s and have no other cardiovascular risk factors have a risk of 4.3-5.3%; some of them may be at above-average risk, whereas the women in this group are at below-average risk, i.e. 4.0-4.9%. The cardiovascular risk was stratified using the BP level, number of risk factors, evidence of subclinical organ damage, and clinical cardiovascular diseases, as shown in table 5.

Table 5.

Stratification of global cardiovascular events for hypertensive patients

| Risk profile | BP |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| stage 2 prehypertension (130–139/85 – 89 mm Hg) | stage 1 hypertension (140 – 159/90 – 99 mm Hg) | stage 2 hypertension (≥160/100 mm Hg) | |||

| Risk factors: 0 | Lowest-risk group | Low added-risk group | Moderate to high added-risk group | ||

| Risk factors other than DM: 1 – 2 | Low to moderate added-risk group | Moderate added-risk group | High added-risk group | ||

| Risk factors: ≥3 or subclinical organ damage | Moderate to high added-risk group | High added-risk group | High added-risk group | ||

| DM, cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease | High added-risk group | High added-risk group | High added-risk group | ||

Risk factors: age (men ≥45 years old, women ≥55 years old), smoking, obesity (or abdominal obesity), dyslipidemia, impaired fasting glucose or impaired glucose tolerance, family history of premature cardiovascular disease, and DM. The 10-year cardiovascular event rates for the lowest-, average-, low added-, moderate added-, and high added-(including the highest added-) risk groups were 2.5, 5, 5 – 10, 10–15, and ≥15%, respectively, according to Korean Medical Insurance Company Study data. DM = Diabetes mellitus.

Principles of Treatment

The Korean guideline does not recommend a drug therapy in patients within the prehypertensive range, even in patients with prediabetes [17,18], diabetes mellitus [19], stroke [20], or coronary artery disease [21]. In an elderly population over 65 years old, drug therapy can be initiated when the SBP is ≥160 mm Hg.

The target BP is generally an SBP of <140 mm Hg and a DBP of <90 mm Hg (table 6) [22,23,24]. In the elderly, the target SBP is approximately 140-150 mm Hg with a DBP that is not excessively low, i.e. less than approximately 60 mm Hg [25,26]. In patients with hypertension and diabetes, the recommended target BP is an SBP <140 mm Hg [27] and a DBP <85 mm Hg [28]. In patients with previous cardiovascular disease including stroke, a reduction of SBP to <130 mm Hg shows no consistent prevention [29,30,31,32,33]. Therefore, a target SBP of <140 mm Hg is recommended. In patients with chronic kidney disease, further control of SBP to <140 mm Hg has shown no additional benefit [34,35,36]. A meta-analysis has not proven that a target BP of <140 mm Hg is any more effective at preventing cardiac and renal events, either [27,37,38]. Therefore, a target SBP of <140 mm Hg is recommended regardless of the presence of diabetes. However, a target SBP <130 mm Hg can be recommended in patients with hypertension with prominent albuminuria [2].

Table 6.

Summary of the target BPs in hypertension treatment

| SBP, mm Hg | DBP, mm Hg | |

|---|---|---|

| Uncomplicated hypertension | 140 | 90 |

| Elderly | 140–150 | 90 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 140 | 85 |

| Stroke | 140 | 90 |

| Coronary artery disease Chronic kidney disease | 140 | 90 |

| Without albuminuriaa | 140 | 90 |

| With albuminuria | 130 | 80 |

Microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria.

In lifestyle modification, sodium reduction is the most important factor in non-drug treatment, because the estimated daily salt intake according to the 2010 KNHANES is 4.9 g of sodium, which is a higher amount than in western or Japanese populations [39].

Key Points in Pharmacologic Treatment

Five classes of antihypertensive drugs, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, β-blockers, calcium antagonists, and diuretics, were equally recommended as a first-line treatment. There is no uniform consensus on the role of β-blockers in elderly patients with hypertension, so prescription of β-blockers in the elderly should be limited to special circumstances. β-Blockers should also be used with care in patients at high risk for diabetes, because in combination with diuretics, they can increase the risk of new onset of diabetes [2]. In patients with BP >160/100 mm Hg or more than 20/10 mm Hg above the target BP, two drugs can be prescribed in combination to maximize the antihypertensive effect and achieve rapid BP control [2].

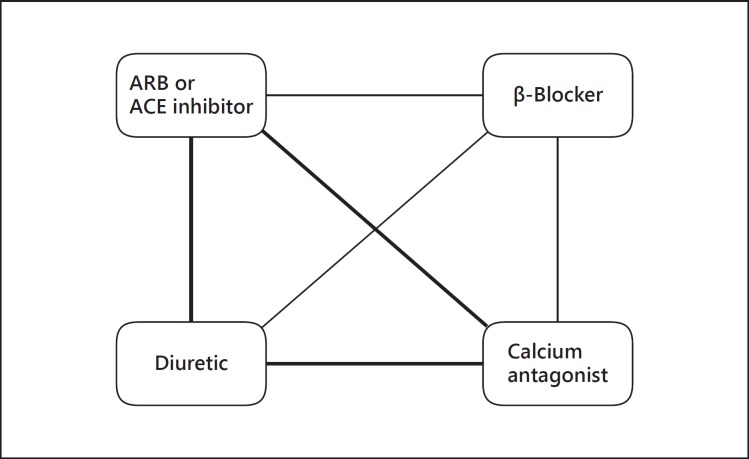

If BP is not controlled with a single drug, two drugs should be combined for BP control. Combination therapy is more effective than single-drug therapy at a higher dose [40]. Combination therapy chosen from the renin-angiotensin system inhibitors, calcium antagonists, and diuretics is recommended first because it has shown relatively good results [23,41,42], but β-blockers can also be combined with drugs of other classes (fig. 1). However, the combination of β-blockers and diuretics can increase the incidence of diabetes and metabolic disorders and thus requires periodic monitoring.

Fig. 1.

Recommended combination therapy. Thick lines indicate preferred combination, and thin lines indicate feasible combination. ARB = Angiotensin receptor blocker; ACE = angiotensin-converting enzyme.

Summary and Conclusion

With limited outcome data in Korea, the Guideline Committee of the Korean Society of Hypertension adopted other hypertension guidelines and modified them to our situation through a transparent guideline development process. Therefore, we think this guideline will be particularly useful for Koreans and guide hypertension diagnosis and management for health-care professionals in Korea.

References

- 1.Shin J, Park JB, Kim K, Kim JH, Yang DH, Pyun WB, Kim YG, Kim GH, et al. 2013 Korean Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension. Part I – epidemiology and diagnosis of hypertension. Clin Hypertens. 2015;21:1. doi: 10.1186/s40885-014-0012-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, Redon J, Zanchetti A, Bohm M, Christiaens T, Cifkova R, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, Galderisi M, Grobbee DE, Jaarsma T, Kirchhof P, Kjeldsen SE, Laurent S, Manolis AJ, Nilsson PM, Ruilope LM, Schmieder RE, Sirnes PA, Sleight P, Viigimaa M, Waeber B, Zannad F, Task Force Members 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) J Hypertens. 2013;31:1281–1357. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000431740.32696.cc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim HC, Oh SM. Noncommunicable diseases: current status of major modifiable risk factors in Korea. J Prev Med Public Health. 2013;46:165–172. doi: 10.3961/jpmph.2013.46.4.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim HC, Nam CM, Jee SH, Suh I. Comparison of blood pressure-associated risk of intracerebral hemorrhage and subarachnoid hemorrhage: Korea Medical Insurance Corporation study. Hypertension. 2005;46:393–397. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000177118.46049.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jee SH, Appel LJ, Suh I, Whelton PK, Kim IS. Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors in South Korean adults: results from the Korea Medical Insurance Corporation (KMIC) Study. Ann Epidemiol. 1998;8:14–21. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(97)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park JK, Kim CB, Kim KS, Kang MG, Jee SH. Meta-analysis of hypertension as a risk factor of cerebrovascular disorders in Koreans. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16:2–8. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.1.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim KS, Ryu SY, Park JK, Kim CB, Chun BY, Lee TY, Lee KS, Lee DH, Koh KW, Jee SH, Suh I. A nested case control study on risk factors for coronary heart disease in Korean. Korean J Prev Med. 2001;34:149–156. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Arima H, Murakami Y, Lam TH, Kim HC, Ueshima H, Woo J, Suh I, Fang X, Woodward M, Asia Pacific Cohort Studies Collaboration Effects of prehypertension and hypertension subtype on cardiovascular disease in the Asia-Pacific region. Hypertension. 2012;59:1118–1123. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.187252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim SJ, Lee J, Nam CM, Jee SH, Park IS, Lee KJ, Lee SY. Progression rate from new-onset pre-hypertension to hypertension in Korean adults. Circ J. 2011;75:135–140. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-09-0948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim SJ, Lee J, Jee SH, Nam CM, Chun K, Park IS, Lee SY. Cardiovascular risk factors for incident hypertension in the prehypertensive population. Epidemiol Health. 2010;32:e2010003. doi: 10.4178/epih/e2010003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cappuccio FP, Kerry SM, Forbes L, Donald A. Blood pressure control by home monitoring: meta-analysis of randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;329:145. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38121.684410.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shin J, Park SH, Kim JH, Ihm SH, Kim G, Kim WS, Kim YM, Pyun WB, Choi SI, Kim SK. Discordance between ambulatory versus clinic blood pressure according to the global cardiovascular risk groups. Kor J Intern Med 2014, in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Committee for Establishing Treatment Instruction for Dyslipidemia of the Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis . Guidelines for Management of Dyslipidemia. ed 2. Seoul: Korean Society of Lipidology and Atherosclerosis; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology Guidelines Committee 2003 European Society of Hypertension-European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. J Hypertens. 2003;21:1011–1053. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200306000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.1999 World Health Organization-International Society of Hypertension guidelines for the management of hypertension Guidelines Subcommittee. J Hypertens. 1999;17:151–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mancia G, De Backer G, Dominiczak A, the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension. the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology 2007 guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: the task force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dagenais GR, Gerstein HC, Holman R, Budaj A, Escalante A, Hedner T, Keltai M, Lonn E, McFarlane S, McQueen M, Teo K, Sheridan P, Bosch J, Pogue J, Yusuf S. Effects of ramipril and rosiglitazone on cardiovascular and renal outcomes in people with impaired glucose tolerance or impaired fasting glucose: results of the Diabetes Reduction Assessment with Ramipril and Rosiglitazone Medication (DREAM) trial. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1007–1014. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McMurray JJ, Holman RR, Haffner SM, et al. Effect of valsartan on the incidence of diabetes and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1477–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Esler A, Mehler P. Effects of aggressive blood pressure control in normotensive type 2 diabetic patients on albuminuria, retinopathy and strokes. Kidney Int. 2002;61:1086–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arima H, Chalmers J, Woodward M, Anderson C, Rodgers A, Davis S, Macmahon S, Neal B, PROGRESS Collaborative Group Lower target blood pressures are safe and effective for the prevention of recurrent stroke: the PROGRESS trial. J Hypertens. 2006;24:1201–1208. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000226212.34055.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zanchetti A, Amery A, Berglund G, Cruickshank JM, Hansson L, Lever AF, Sleight P. How much should blood pressure be lowered? The problem of the J-shaped curve. J Hypertens Suppl. 1989;7:S338–S348. doi: 10.1097/00004872-198900076-00165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zanchetti A, Grassi G, Mancia G. When should antihypertensive drug treatment be initiated and to what levels should systolic blood pressure be lowered? A critical reappraisal. J Hypertens. 2009;27:923–934. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32832aa6b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Li W, Zhang X, Zanchetti A, FEVER Study Group The Felodipine Event Reduction (FEVER) Study: a randomized long-term placebo-controlled trial in Chinese hypertensive patients. J Hypertens. 2005;23:2157–2172. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000194120.42722.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Zhang X, Liu L, Zanchetti A, FEVER Study Group Is a systolic blood pressure target <140 mm Hg indicated in all hypertensives? Subgroup analyses of findings from the randomized FEVER trial. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1500–1508. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.JATOS Study Group Principal results of the Japanese trial to assess optimal systolic blood pressure in elderly hypertensive patients (JATOS) Hypertens Res. 2008;31:2115–2127. doi: 10.1291/hypres.31.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogihara T, Saruta T, Rakugi H, Matsuoka H, Shimamoto K, Shimada K, Imai Y, Kikuchi K, Ito S, Eto T, Kimura G, Imaizumi T, Takishita S, Ueshima H, Valsartan in Elderly Isolated Systolic Hypertension Study Group Target blood pressure for treatment of isolated systolic hypertension in the elderly: valsartan in elderly isolated systolic hypertension study. Hypertension. 2010;56:196–202. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.146035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.ACCORD Study Group. Cushman WC, Evans GW, Byington RP, Goff DC, Jr, Grimm RH, Jr, Cutler JA, Simons-Morton DG, Basile JN, Corson MA, Probstfield JL, Katz L, Peterson KA, Friedewald WT, Buse JB, Bigger JT, Gerstein HC, Ismail-Beigi F. Effects of intensive blood-pressure control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1575–1585. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1001286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, Dahlof B, Elmfeldt D, Julius S, Menard J, Rahn KH, Wedel H, Westerling S. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) randomised trial. HOT Study Group. Lancet. 1998;351:1755–1762. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fox KM, European Trial on Reduction of Cardiac Events with Perindopril in Stable Coronary Artery Disease Investigators Efficacy of perindopril in reduction of cardiovascular events among patients with stable coronary artery disease: randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the EUROPA study) Lancet. 2003;362:782–788. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(03)14286-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Poole-Wilson PA, Lubsen J, Kirwan BA, van Dalen FJ, Wagener G, Danchin N, Just H, Fox KA, Pocock SJ, Clayton TC, Motro M, Parker JD, Bourassa MG, Dart AM, Hildebrandt P, Hjalmarson A, Kragten JA, Molhoek GP, Otterstad JE, Seabra-Gomes R, Soler-Soler J, Weber S, Coronary Disease Trial Investigating Outcome with Nifedipine Gastrointestinal Therapeutic System Investigators Effect of long-acting nifedipine on mortality and cardiovascular morbidity in patients with stable angina requiring treatment (ACTION trial): randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:849–857. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16980-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Braunwald E, Domanski MJ, Fowler SE, Geller NL, Gersh BJ, Hsia J, Pfeffer MA, Rice MM, Rosenberg YD, Rouleau JL, PEACE Trial Investigators Angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibition in stable coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2058–2068. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ovbiagele B, Diener HC, Yusuf S, Martin RH, Cotton D, Vinisko R, Donnan GA, Bath PM, PROFESS Investigators Level of systolic blood pressure within the normal range and risk of recurrent stroke. JAMA. 2011;306:2137–2144. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yusuf S, Diener HC, Sacco RL, Cotton D, Ounpuu S, Lawton WA, Palesch Y, Martin RH, Albers GW, Bath P, Bornstein N, Chan BP, Chen ST, Cunha L, Dahlof B, De Keyser J, Donnan GA, Estol C, Gorelick P, Gu V, Hermansson K, Hilbrich L, Kaste M, Lu C, Machnig T, Pais P, Roberts R, Skvortsova V, Teal P, Toni D, VanderMaelen C, Voigt T, Weber M, Yoon BW, PROFESS Study Group Telmisartan to prevent recurrent stroke and cardiovascular events. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1225–1237. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Klahr S, Levey AS, Beck GJ, Caggiula AW, Hunsicker L, Kusek JW, Striker G. The effects of dietary protein restriction and blood-pressure control on the progression of chronic renal disease. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:877–884. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199403313301301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wright JT, Jr, Bakris G, Greene T, Agodoa LY, Appel LJ, Charleston J, Cheek D, Douglas-Baltimore JG, Gassman J, Glassock R, Hebert L, Jamerson K, Lewis J, Phillips RA, Toto RD, Middleton JP, Rostand SG, African American Study of Kidney Disease and Hypertension Study Group Effect of blood pressure lowering and antihypertensive drug class on progression of hypertensive kidney disease: results from the AASK trial. JAMA. 2002;288:2421–2431. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ruggenenti P, Perna A, Loriga G, Ganeva M, Ene-Iordache B, Turturro M, Lesti M, Perticucci E, Chakarski IN, Leonardis D, Garini G, Sessa A, Basile C, Alpa M, Scanziani R, Sorba G, Zoccali C, Remuzzi G, REIN-2 Study Group Blood-pressure control for renoprotection in patients with non-diabetic chronic renal disease (REIN-2): multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;365:939–946. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71082-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Arguedas JA, Perez MI, Wright JM. Treatment blood pressure targets for hypertension. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;CD004349 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004349.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Upadhyay A, Earley A, Haynes SM, Uhlig K. Systematic review: blood pressure target in chronic kidney disease and proteinuria as an effect modifier. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:541–548. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-8-201104190-00335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 2010 Korean National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (KNHANES) Cheongju: Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2010. 2010 Korean National Health Statistics. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wald DS, Law M, Morris JK, Bestwick JP, Wald NJ. Combination therapy versus monotherapy in reducing blood pressure: meta-analysis on 11,000 participants from 42 trials. Am J Med. 2009;122:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel A, MacMahon S, Chalmers J, Neal B, Woodward M, Billot L, Harrap S, Poulter N, Marre M, Cooper M, Glasziou P, Grobbee DE, Hamet P, Heller S, Liu LS, Mancia G, Mogensen CE, Pan CY, Rodgers A, Williams B, ADVANCE Collaborative Group Effects of a fixed combination of perindopril and indapamide on macrovascular and microvascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (the ADVANCE trial): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;370:829–840. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61303-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jamerson K, Weber MA, Bakris GL, Dahlof B, Pitt B, Shi V, Hester A, Gupte J, Gatlin M, Velazquez EJ, ACCOMPLISH Trial Investigators Benazepril plus amlodipine or hydrochlorothiazide for hypertension in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2417–2428. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0806182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]