Abstract

Background

Neonatal hypoglycemia is common and can cause neurologic impairment, but evidence supporting thresholds for intervention is limited.

Methods

We performed a prospective cohort study involving 528 neonates with a gestational age of at least 35 weeks who were considered to be at risk for hypoglycemia; all were treated to maintain a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter (2.6 mmol per liter). We intermittently measured blood glucose for up to 7 days. We continuously monitored interstitial glucose concentrations, which were masked to clinical staff. Assessment at 2 years included Bayley Scales of Infant Development III and tests of executive and visual function.

Results

Of 614 children, 528 were eligible, and 404 (77% of eligible children) were assessed; 216 children (53%) had neonatal hypoglycemia (blood glucose concentration, <47 mg per deciliter). Hypoglycemia, when treated to maintain a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter, was not associated with an increased risk of the primary outcomes of neurosensory impairment (risk ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75 to 1.20; P = 0.67) and processing difficulty, defined as an executive-function score or motion coherence threshold that was more than 1.5 SD from the mean (risk ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.56 to 1.51; P = 0.74). Risks were not increased among children with unrecognized hypoglycemia (a low interstitial glucose concentration only). The lowest blood glucose concentration, number of hypoglycemic episodes and events, and negative interstitial increment (area above the interstitial glucose concentration curve and below 47 mg per deciliter) also did not predict the outcome.

Conclusions

In this cohort, neonatal hypoglycemia was not associated with an adverse neurologic outcome when treatment was provided to maintain a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter. (Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development and others.)

Neonatal hypoglycemia is a common and readily treatable risk factor for neurologic impairment in children. Although associations between prolonged symptomatic neonatal hypoglycemia and brain injury are well established,1 the effect of milder hypoglycemia on neurologic development is uncertain.2 Consequently, large numbers of newborns are screened and treated for low blood glucose concentrations, which involves heel-stick blood tests, substantial costs, and the possibility of iatrogenic harm.

Under current guidelines,3 up to 30% of neonates are considered to be at risk for hypoglycemia, 15% receive a diagnosis of hypoglycemia, and approximately 10% require admission to a neonatal intensive care unit,4 costing an estimated $2.1 billion annually in the United States alone.5 Associated formula feeding and possible separation of mother and baby reduce breast-feeding rates,6 with potentially adverse effects on broader infant health and development. In addition, pain-induced stress in neonates, such as repeated heel sticks, may itself impair brain development.7 Thus, to determine appropriate glycemic thresholds for treatment, there have been repeated calls for studies of the effect of neonatal hypoglycemia on long-term development.2,8

We report the results of the Children with Hypoglycaemia and Their Later Development (CHYLD) study, a large prospective cohort study of term and late-preterm neonates born at risk for hypoglycemia. The study investigated the relation between the duration, frequency, and severity of low glucose concentrations in the neonatal period and neuropsychological development at 2 years.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

Eligible infants were those at risk for neonatal hypoglycemia primarily on the basis of maternal diabetes, preterm birth (gestational age of <37 weeks), or a birth weight that was low (<10th percentile or <2500 g) or high (>90th percentile or >4500 g).6 Infants were enrolled before or shortly after birth in one of two parallel studies: the Babies and Blood Sugar's Influence on EEG Study (BABIES) (102 infants) and the Sugar Babies study (514 infants), conducted from 2006 to 2010 at Waikato Hospital, in Hamilton, New Zealand, a regional public hospital with 5500 births annually.6,9 Infants with serious congenital malformations or terminal conditions were excluded. Cohort characteristics, glycemic management, and neonatal outcomes have been reported previously.6,9,10 Infants underwent regular measurement of blood glucose concentrations by means of the glucose oxidase method (ABL800 FLEX, Radiometer) for 24 to 48 hours or until there were no ongoing clinical concerns. Masked continuous interstitial glucose monitoring (CGMS Gold, Medtronic MiniMed) was performed as previously described.11,12 Hypoglycemia, defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 47 mg per deciliter (2.6 mmol per liter), was treated with any combination of additional feeding, buccal dextrose gel, and intravenous dextrose to maintain a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter. Approximately one third of the infants (237) were enrolled in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of buccal dextrose gel.6

Both neonatal studies and the follow-up study were approved by the regional ethics committee. Written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian of each infant at study entry and at follow-up.

Assessment at 2 Years

At 2 years of corrected age, children born at a gestational age of at least 35 weeks underwent neurologic examination, tests of executive function, assessment with the use of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development III (BSID-III, a norm-referenced scale in which composite scores are assessed according to the scale mean [±SD] of 100±15, and lower scores indicate greater impairment),13 vision screening (for details, see the Supplementary Appendix, available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org), and global motion perception testing (assessment of dorsal-visual-pathway function, measured as optokinetic reflex responses to random-dot kinematograms of varying coherence).14 Caregivers completed questionnaires about the home environment, the child's health, and — with the use of the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–preschool version (BRIEF-P) — the child's executive function.15 All children underwent neonatal audiologic screening, with targeted audiologic follow-up when indicated.

Executive-function tests comprised four tasks that assess inhibitory control (snack delay and shape stroop),16 capacity for reverse categorization (ducks and buckets),17 and attentional flexibility (multisearch, multilocation task).18 Scores (ranging from 0 to 6 points per task, with higher scores indicating better function) were summed to obtain an executive-function score of up to 24 points.

Prespecified primary outcomes were neurosensory impairment and processing difficulty. Neurosensory impairment was defined as any of the following findings: developmental delay (BSID-III cognitive or language composite score of <85), motor impairment (BSID-III motor composite score of <85), cerebral palsy,19 hearing impairment (requiring hearing aids), or blindness (≥1.4 logMAR [log10 of the minimal angle of resolution] in both eyes). Processing difficulty was defined as either a motion coherence threshold or an executive-function score that was more than 1.5 SD from the mean, indicating performance in the worst 7% of the cohort. Secondary outcomes included individual components of the primary outcomes, BSID-III scores for social and emotional function and adaptive behavior, vision-impairment and refractive-error scores, T scores on the BRIEF-P, and seizures.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed with SAS software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute). Primary analyses compared primary and secondary outcomes between children with and those without hypoglycemic episodes in the first week after birth (any episode, ≥3 episodes, episodes on ≥3 days, and any severe episode), with the use of generalized linear models adjusted for prespecified potential confounders (socioeconomic decile,20 sex, and primary risk factor for neonatal hypoglycemia). A hypoglycemic episode was defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 47 mg per deciliter on a single measurement or consecutive measurements, with a severe episode defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 36 mg per deciliter (2.0 mmol per liter). Interstitial episodes were defined as periods of interstitial glucose concentrations that were below those thresholds for at least 10 minutes. Results are presented as risk ratios and mean differences with 95% confidence intervals. A two-tailed alpha level of less than 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance, with no adjustment for multiple comparisons. Sample size was limited by the size of the inception cohorts, but we estimated that this study would have 80% power to detect between-group differences in BSID-III scores of 5 points or more.

Secondary analyses related continuous measures of hypoglycemic exposure to primary outcomes, with the use of receiver-operating-characteristic (ROC) curves. To explore the predictive value of different glycemic thresholds for adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes, the negative interstitial increment was used, calculated as the area above the interstitial glucose concentration curve and below a given threshold. Repeated-measures mixed models explored trend over time. Logistic regression was used to estimate the likelihood of the primary outcomes according to quantile of continuous glycemic variables.

Results

Study Cohort

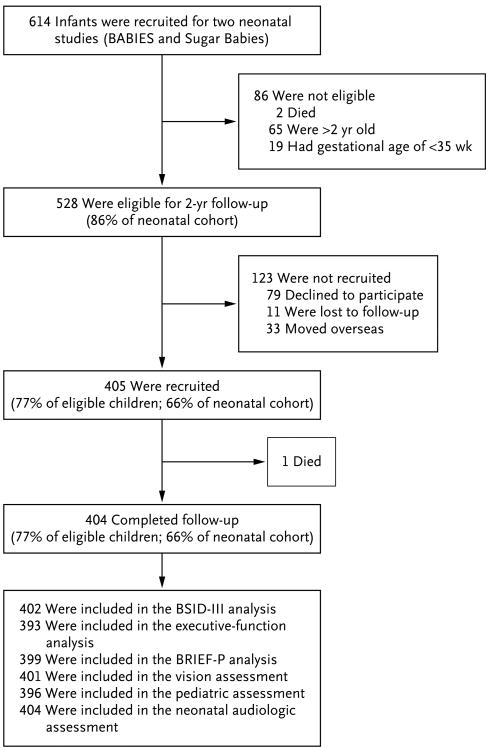

The cohort comprised 614 infants (2 infants participated in both neonatal studies) (Fig. 1). Because follow-up started after some children were older than 2 years of age and those born before 35 weeks' gestation were excluded, 528 children were eligible, of whom 404 (77% of eligible infants) were assessed at a mean (±SD) corrected age of 24.3±1.9 months. Eligible children who did not participate in the study were more likely to be of Maori or other non-European ethnic origin, and their mothers had a slightly lower body-mass index but were similar with respect to other baseline variables (Table 1).

Figure 1. Cohort of Children Followed up at 2 Years.

BABIES denotes Babies and Blood Sugar's Influence on EEG Study, BRIEF-P Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–preschool version, and BSID-III Bayley Scales of Infant Development III. Pediatric assessment included history taking and physical examination (including neurologic examination) by a pediatrician.

Table 1.

Maternal and Neonatal Characteristics of the Study Participants and Nonparticipants.*

| Characteristic | Participants | Nonparticipants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Neonatal Hypoglycemia | No Neonatal Hypoglycemia | ||

| Maternal | ||||

| No. of women | 376 | 201 | 175 | 115 |

| Age — yr | 29.9±6.3 | 29.9±6.1 | 30.0±6.5 | 29.0±7.0 |

| Body-mass index in early pregnancy† | 29.3±7.6 | 29.1±7.4 | 29.5±7.8 | 27.2±6.0‡ |

| Diabetes during pregnancy — no. (%) | ||||

| Gestational | 129 (34) | 58 (29)§ | 71 (41) | 40 (35) |

| Pregestational | 28 (7) | 20 (10) | 8 (5) | 4 (3) |

| Controlled by diet | 36 (10) | 16 (8) | 20 (11) | 11 (10) |

| Treated with oral hypoglycemic agent | 22 (6) | 6 (3) | 16 (9) | 3 (3) |

| Treated with insulin | 86 (23) | 49 (24) | 37 (21) | 23 (20) |

| Neonatal | ||||

| No. of infants | 404 | 216 | 188 | 124 |

| Female sex — no. (%) | 192 (48) | 116 (54)¶ | 76 (40) | 55 (44) |

| Twin — no. (%) | 51 (13) | 32 (15) | 19 (10) | 17 (14) |

| Ethnic group — no. (%)║ | ||||

| Maori | 115 (28) | 60 (28) | 55 (29) | 42 (34) |

| Pacific Islander | 14 (3) | 7 (3) | 7 (4) | 0 |

| Other | 69 (17) | 31 (14) | 38 (20) | 31 (25) |

| New Zealand European | 206 (51) | 118 (55) | 88 (47) | 51 (41) |

| Socioeconomic decile | 4.5±2.7 | 4.5±2.7 | 4.5±2.7 | 4.3±2.5 |

| Gestational age — wk | 37.8±1.7 | 37.7±1.6 | 37.8±1.7 | 37.8±1.8 |

| Birth weight — g | 3134±844 | 3089±811 | 3187±879 | 3026±883 |

| Birth weight z score | 0.19±1.68 | 0.13±1.70 | 0.25±1.65 | −0.05±1.71 |

| Admitted to NICU — no. (%) | 156 (39) | 101 (47)¶ | 55 (29) | 50 (40) |

| Primary risk factor for neonatal hypoglycemia — no. (%) | ||||

| Maternal diabetes | 161 (40) | 80 (37) | 81 (43) | 44 (35) |

| Late preterm: gestational age of 35 or 36 wk | 129 (32) | 71 (33) | 58 (31) | 43 (35) |

| Small: <10th percentile or <2.5 kg | 60 (15) | 39 (18) | 21 (11) | 18 (15) |

| Large: >90th percentile or >4.5 kg | 42 (10) | 17 (8) | 25 (13) | 12 (10) |

| Other** | 12 (3) | 9 (4) | 3 (2) | 7 (6) |

| Blood glucose monitoring | ||||

| Median age at first sample (IQR) — hr | 1.5 (1.2–2.1) | 1.5 (1.2–2.0) | 1.5 (1.2–2.2) | 1.6 (1.2–2.1) |

| Duration of monitoring — hr | 52.8±27.2 | 58.9 ±27.4¶ | 45.7±25.3 | 53.5±29.4 |

| No. of samples in first week | 14.7±5.7 | 16.3±6.0¶ | 11.6±3.5 | 15.4±4.6 |

| Blood glucose (range) — mg/dl†† | ||||

| <12 hr | 59.5±10.8 (9.0–137.0) | 54.1±7.2 (9.0–127.9)¶ | 64.9±10.8 (46.8–136.9) | 59.5±10.8 (12.6–133.3) |

| 12 to <24 hr | 64.9±12.6) (32.4–154.9) | 61.3±10.8 (32.4–127.9)¶ | 68.5±12.6 (46.8–145.9) | 66.7±10.8 (36.0–126.1)‡‡ |

| 24 to <48 hr | 66.7±10.8 (16.2–155.0) | 63.1±10.8 (16.2–155.0)¶ | 70.3±10.8 (46.8–129.7) | 68.5±10.8 (37.8–111.7) |

| ≥48 hr | 75.7±14.4 (19.8–171.2) | 72.1±12.6 (19.8–171.2)¶ | 79.3±14.4 (48.6–127.9) | 77.5±14.4 (34.2–176.6) |

| Hypoglycemia — no. (%) | ||||

| ≥1 Episode | 216 (53) | 216 (100)¶ | 0 | 61 (49) |

| ≥3 Episodes | 34 (8) | 34 (16)¶ | 0 | 10 (8) |

| Episodes on ≥3 days in first week | 12 (3) | 12 (6)¶ | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Severe hypoglycemia — no. (%) | ||||

| ≥1 Episode | 64 (16) | 64 (30)¶ | 0 | 18 (15) |

| ≥3 Episodes | 3 (1) | 3 (1)¶ | 0 | 0 |

| Episodes on ≥3 days in first week | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1)¶ | 0 | 0 |

| Interstitial glucose monitoring | ||||

| No. of infants (%) | 305 (75) | 164 (76) | 141 (75) | 80 (65) |

| Median age when recording commenced (IQR) — hr | 4.0 (2.5–6.2) | 3.2 (2.3–5.3)¶ | 4.9 (3.2–6.6) | 4.4 (2.4–7.3) |

| Duration of monitoring — hr | 43.7±21.4 | 48.9±22.4¶ | 37.7±18.5 | 43.8±22.4 |

| ≥1 Episode with glucose at <47 mg/dl — no. (%) | 163 (53) | 130 (79)¶ | 33 (23) | 36 (45) |

| ≥1 Episode with glucose at <36 mg/dl — no. (%) | 43 (14) | 39 (24)¶ | 4 (3) | 8 (10) |

| Median time with glucose at <47 mg/dl (IQR) — min | ||||

| In first 48 hr | 15 (0–145) | 103 (15–273)¶ | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–90) |

| In first week | 20 (0–145) | 105 (20–303)¶ | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–103) |

| Neonatal dextrose treatment — no. (%) | ||||

| Oral gel only | 101 (25) | 101 (47) | 0 | 35 (28) |

| Intravenous only | 22 (5) | 12 (6) | 10 (5) | 10 (8) |

| Oral gel and intravenous | 21 (5) | 21 (10) | 0 | 1 (1) |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD unless otherwise specified. A hypoglycemic episode was defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 47 mg per deciliter (2.6 mmol per liter) on a single measurement or consecutive measurements; an episode of severe hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 36 mg per deciliter (2.0 mmol per liter). An interstitial episode or a severe interstitial episode was defined as an interstitial glucose concentration below the respective threshold for least 10 minutes. To convert values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551. See the Supplementary Appendix for data on maternal gravidity and parity, weight gain during pregnancy, smoking status, alcohol use during pregnancy, maternal education, mode of birth, 5-minute Apgar score, and infant feeding in the first week. IQR denotes interquartile range, and NICU neonatal intensive care unit.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters. Data on maternal body-mass index were missing for 4 participants and 1 nonparticipant.

P<0.01 for the comparison with participants.

P<0.05 for the comparison with children who did not have neonatal hypoglycemia.

P<0.01 for the comparison with children who did not have neonatal hypoglycemia.

Information on ethnic group was reported by the parent or guardian. Children could be assigned to more than one ethnic group; in such cases, ethnic groups were prioritized in the following order: Maori, Pacific Islander, Other, and New Zealand European. P<0.01 for the comparison of nonparticipants with participants.

Other risk factors included sepsis, hemolytic disease of the newborn, respiratory distress, congenital heart disease, and poor feeding.

The mean was calculated from the mean blood glucose value for each infant; the range is for all blood glucose concentrations.

P<0.05 for the comparison with participants.

Neonatal Hypoglycemia

Although neonatal hypoglycemia was common (observed in 216 children [53%]), regular measurement of blood glucose concentrations and early treatment meant that recurrent hypoglycemia was infrequent (Table 1). Nevertheless, continuous interstitial glucose monitoring showed that nearly one quarter of the infants had low glucose concentrations that were not detected by intermittent blood glucose monitoring. Even with treatment, many infants had prolonged periods of low interstitial glucose concentrations. Thus, 25% of those treated for neonatal hypoglycemia had at least 5 hours of low interstitial glucose concentrations during the first week (Table 1).

Neurodevelopmental Impairment at 2 Years

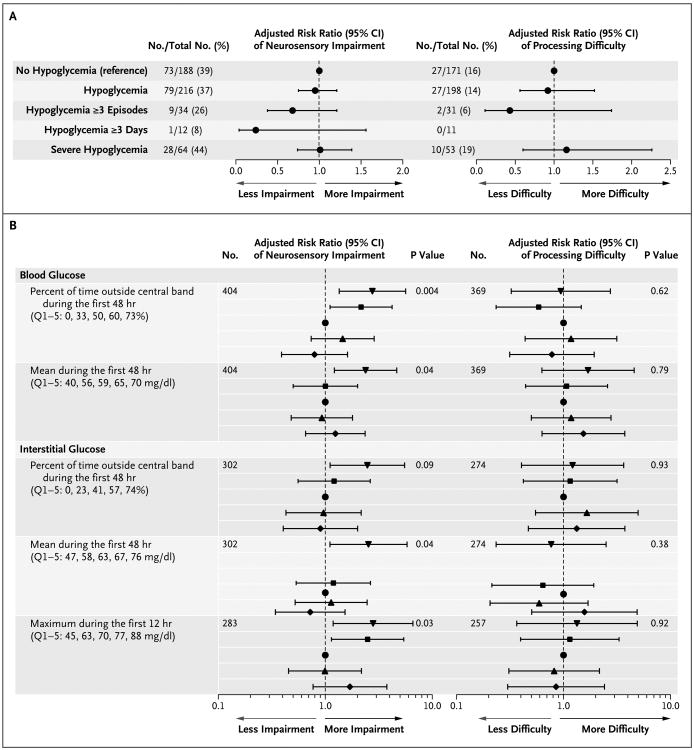

The risk of neurosensory impairment or processing difficulty was not higher among children with neonatal hypoglycemia (when treated to maintain a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter) than among those without neonatal hypoglycemia (risk ratio for neurosensory impairment, 0.95; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.75 to 1.20; P = 0.67; 404 children included in the analysis; and risk ratio for processing difficulty, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.56 to 1.51; P = 0.74; 369 children included in the analysis), even among children with multiple hypoglycemic episodes, episodes on multiple days, or severe episodes (Fig. 2A). Children with neonatal hypoglycemia had slightly better BSID-III scores for social and emotional adaptation than did children without neonatal hypoglycemia (mean difference in scores, 3.5 points; 95% CI, 0.4 to 6.5; P = 0.02) (Table 2), but other secondary outcomes were similar in the two study groups (Table S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Furthermore, children with unrecognized and therefore untreated low glucose concentrations (detected only on continuous interstitial glucose monitoring) also had no increased risk of abnormal neurodevelopment as compared with those with no evidence of low blood glucose concentrations (neurosensory impairment in 14 of 33 children vs. 45 of 108; risk ratio, 1.01; 95% CI, 0.66 to 1.54; P = 0.98; and processing difficulty in 5 of 29 children vs. 17 of 99; risk ratio, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.38 to 2.23; P = 0.86).

Figure 2. Effect of Hypoglycemia on the Primary Outcome and Relation between Continuous Glycemic Exposure and the Primary Outcome.

Panel A shows the effect of hypoglycemia on the risk of the primary outcome. A hypoglycemic episode was defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 47 mg per deciliter (2.6 mmol per liter) on a single measurement or consecutive measurements; severe hypoglycemia was defined as a blood glucose concentration of less than 36 mg per deciliter (2.0 mmol per liter). Results were adjusted for socioeconomic decile,20 sex, and primary risk factor for neonatal hypoglycemia. Panel B shows the relationship between continuous glycemic exposure and the primary outcome. Logistic regression was used to compare the risk of an adverse outcome according to the quintile of the continuous glycemic variable in the first 48 hours. Results were adjusted for socioeconomic decile, sex, and primary risk factor for neonatal hypoglycemia. Diamonds denote quintile 1, upward-pointing triangles quintile 2, circles quintile 3 (reference), squares quintile 4, and downward-pointing triangles quintile 5. Values for quintiles 1 through 5 (Q1–5) represent the lowest value for each quintile. The central band was defined as a blood glucose or an interstitial glucose concentration of 54 to 72 mg per deciliter. To convert the values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551.

Table 2.

Secondary Outcomes at 2 Years in Children with and Those without Neonatal Hypoglycemia.*

| Outcome | Neonatal Hypoglycemia | No Neonatal Hypoglycemia | Adjusted Difference in Means or Risk Ratio (95% CI) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Result | No. Assessed | Result | No. Assessed | |||

| BSID-III composite scores† | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Cognitive | 93.8±10.0 | 215 | 93.1±10.5 | 187 | 0.6 (−1.3 to 2.6) | 0.55 |

|

| ||||||

| Language | 95.5±13.1 | 215 | 93.8±15.4 | 187 | 1.4 (−1.3 to 4.1) | 0.30 |

|

| ||||||

| Motor | 98.6±9.4 | 215 | 98.7±9.7 | 187 | −0.2 (−2.1 to 1.6) | 0.81 |

|

| ||||||

| Social–emotional | 104.3±15.3 | 207 | 100.5±14.7 | 175 | 3.5 (0.4 to 6.5) | 0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| Adaptive behavior | 99.6±14.1 | 209 | 98.4±15.8 | 177 | 0.3 (−2.7 to 3.3) | 0.84 |

|

| ||||||

| Developmental delay — no. (%)‡ | 70 (33) | 215 | 68 (36) | 187 | 0.90 (0.70 to 1.17) | 0.44 |

|

| ||||||

| Executive-function score | 10.6±4.4 | 207 | 10.3±4.1 | 177 | 0.3 (−0.5 to 1.1) | 0.49 |

|

| ||||||

| BRIEF-P global T score >65 — no. (%)§ | 46 (21) | 214 | 44 (24) | 184 | 0.84 (0.59 to 1.20) | 0.34 |

|

| ||||||

| Motion coherence threshold — %¶ | 41.5±14.2 | 204 | 43.2±13.4 | 175 | −1.7 (−4.5 to 1.1) | 0.24 |

|

| ||||||

| Cerebral palsy — no. (%) | 2 (1) | 216 | 2 (1) | 185 | 0.81 (0.11 to 5.99) | 0.83 |

|

| ||||||

| Seizures, any — no. (%) | 10 (5) | 212 | 11 (6) | 184 | 0.71 (0.31 to 1.64) | 0.42 |

Plus–minus values are means ±SD unless otherwise specified. Between-group differences (children with neonatal hypoglycemia vs. children without neonatal hypoglycemia) are expressed as differences between means for Bayley Scales of Infant Development III (BSID-III) scores, executive-function score, and motion coherence threshold and as risk ratios for developmental delay, Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function–preschool version (BRIEF-P) global T score higher than 65, cerebral palsy, and seizures, with adjustment for socioeconomic decile, sex, and primary risk factor for neonatal hypoglycemia. See the Supplementary Appendix for the following additional outcomes: T scores on the BRIEF-P, executive dysfunction, visual-processing difficulty, scores for vision impairment and refractive error, hearing impairment, and blindness.

BSID-III scores have a standardized mean (±SD) of 100±15, with higher scores indicating better development.

Developmental delay was defined as a BSID-III cognitive or language score of less than 85.

T scores on the BRIEF-P have a standardized mean of 50±10, with higher scores indicating worse functioning. A score higher than 65 is considered to be indicative of a clinically significant problem with executive function.

Motion coherence threshold is a measurement of dorsal-visual-pathway function, determined from optokinetic reflex responses to randomdot kinematograms of varying coherence. Higher thresholds indicate worse visual processing ability.

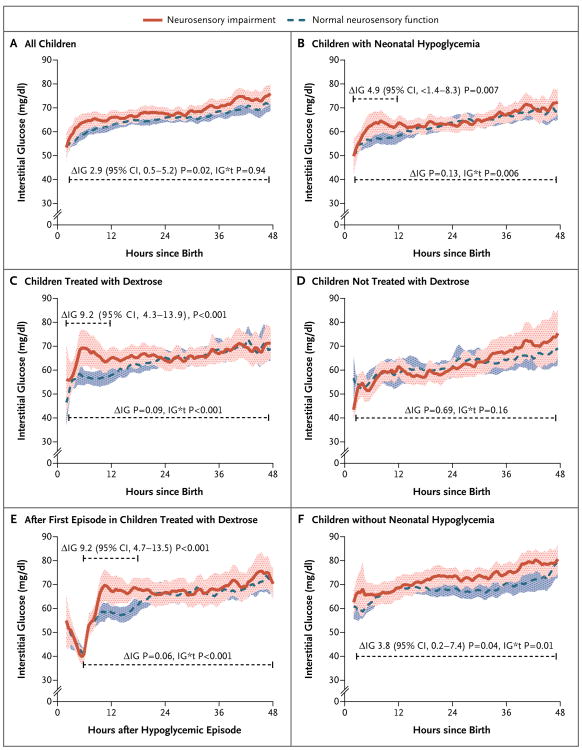

As continuous predictors, the lowest blood glucose concentration, number of hypoglycemic episodes (including severe episodes), and number of combined hypoglycemic events (blood and interstitial episodes) in the first week did not discriminate between children with and those without later neurodevelopmental impairment (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix). Similarly, at thresholds below 47 mg per deciliter, the negative interstitial increment was not predictive of neurosensory impairment. There was some evidence of a discriminative association at thresholds above 54 mg per deciliter (3.0 mmol per liter) (Fig. S1 in the Supplementary Appendix) but in the reverse direction, suggesting that neurosensory impairment was associated with higher neonatal glucose concentrations, even though clinical hyperglycemia was uncommon (3 infants had a blood glucose concentration >144 mg per deciliter [8.0 mmol per liter]). Furthermore, children with neurosensory impairment at 2 years had slightly higher interstitial glucose concentrations throughout the first 48 hours than did those with normal neurosensory function (mean difference, 2.9 mg per deciliter [0.2 mmol per liter]; 95% CI, 0.5 to 5.2 mg per deciliter [0.0 to 0.3 mmol per liter]; P = 0.02; 302 children included in the analysis) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3. Results of Interstitial Glucose Monitoring in Children with and Those without Neurosensory Disability at 2 Years.

Data are means and 95% confidence intervals and represent the per-child 0.5-hour average of continuous interstitial glucose concentrations. ΔIG denotes the mean difference in the first 12 hours or first 48 hours, as determined from repeated-measures analysis, and IG*t the group–time interaction. Panel A shows data for all 302 children who underwent interstitial monitoring in the first 48 hours after birth, Panel B shows data for the 162 children with neonatal hypoglycemia, Panel C shows data for the 104 children with neonatal hypoglycemia who were treated with dextrose (buccal dextrose gel, intravenous dextrose, or both), Panel D shows data for the 58 children with neonatal hypoglycemia who were not treated with dextrose, Panel E shows interstitial glucose values after the first hypoglycemic episode in the 104 children treated with dextrose, and Panel F shows data for the 140 children without neonatal hypoglycemia.

Given the potential for a U-shaped relation between neonatal glucose concentrations and neurodevelopmental impairment, we calculated the time outside a central band,21 defined as the proportion of blood or interstitial glucose measurements that were less than 54 mg per deciliter or greater than 72 mg per deciliter (4.0 mmol per liter) during the first 48 hours — the thresholds that approximated the lower and upper quartiles for all blood glucose concentrations during this period. Infants in the highest quintiles of time outside this central band were more likely than those in the middle (reference) quintile to have neurosensory impairment; if the proportion of blood glucose values outside the band was above the median, the risk ratio for neurosensory impairment was 1.40 (95% CI, 1.09 to 1.79; P = 0.008; 404 children included in the analysis) (Fig. 2B). There was no association between time outside the central band and processing difficulty. Greater time outside the central band was associated with an increased risk of cognitive delay but not language or motor delay. If the proportion of blood glucose concentrations outside the band was above the median, the risk ratio for cognitive delay was 1.57 (95% CI, 1.10 to 2.23; P = 0.01; 402 children included in the analysis), the risk ratio for language delay was 1.40 (95% CI, 0.97 to 2.01; P = 0.07; 401 children included in the analysis), and the risk ratio for motor delay was 1.64 (95% CI, 0.84 to 3.19; P = 0.14; 401 children included in the analysis). Neurosensory impairment was also related to the maximum interstitial glucose concentration in the first 12 hours (Fig. 2B). Although the time outside the central band was greater for infants with hypoglycemia than for those without hypoglycemia (mean difference in the proportion of blood glucose concentrations outside the central band, 0.11; 95% CI, 0.07 to 0.16; P = 0.001), the association between time outside the central band and neurosensory impairment was not influenced by neonatal hypoglycemia (P = 0.54 for interaction).

Among children who had neonatal hypoglycemia, those with subsequent neurosensory impairment had a steeper initial rise in interstitial glucose concentrations and higher concentrations for 12 hours after birth than did the children without neurosensory impairment (mean difference, 4.9 mg per deciliter [0.3 mmol per liter]; 95% CI, 1.4 to 8.3 mg per deciliter [0.1 to 0.5 mmol per liter]; P = 0.007; 162 children included in the analysis) (Fig. 3B). This higher interstitial glucose curve was seen only among infants treated with dextrose, whether it was administered orally, intravenously, or both (mean difference during the first 12 hours after birth, 9.2 mg per deciliter [0.5 mmol per liter]; 95% CI, 4.3 to 13.9 mg per deciliter [0.2 to 0.8 mmol per liter]; P<0.001) (Fig. 3C and 3D) and was temporally related to the first hypoglycemic episode (Fig. 3E). Furthermore, the risk of neurosensory impairment among infants treated with dextrose was related to the maximum interstitial glucose concentration within 12 hours after the first episode; if the maximum interstitial glucose concentration was above the median, the risk ratio was 1.77 (95% CI, 1.01 to 3.11; P = 0.047; 100 children included in the analysis). Dextrose treatment was associated with higher interstitial glucose concentrations for approximately 36 hours after the first hypoglycemic episode, as compared with no dextrose treatment (Fig. S2 in the Supplementary Appendix). Infants receiving intravenous dextrose had higher maximum interstitial glucose concentrations during the first 12 hours after the first hypoglycemic episode than did those treated with dextrose gel alone (mean difference, 18.2 mg per deciliter [1.0 mmol per liter]; 95% CI, 12.8 to 25.4 mg per deciliter [0.7 to 1.4 mmol per liter]; P<0.001), though the risk of neurosensory impairment in these subgroups was similar (37 of 101 children vs. 14 of 33; risk ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 0.71 to 1.67; P = 0.71).

Discussion

After reports of altered somatosensory evoked potentials and an increased incidence of developmental delay in infants with glucose concentrations of less than 47 mg per deciliter,22,23 a glucose concentration of 47 mg per deciliter became a well-accepted glycemic threshold for treatment in newborns,3 despite the lack of evidence that intervention at this threshold is safe or effective.8 The use of this threshold in newborns is perhaps surprising, given that blood glucose concentrations below 60 mg per deciliter (3.3 mmol per liter) are considered low in children and adults.21 In this large prospective study of at-risk term and late-preterm infants, we found that with a treatment threshold of 47 mg of glucose per deciliter, neonatal hypoglycemia was not associated with adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes at 2 years. Our study suggests that a protocol of regular blood glucose monitoring in the first 48 hours after birth and intervention aimed at maintaining a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter is effective in preventing neuronal injury in at-risk term and late-preterm newborns.

It is important to distinguish between thresholds for intervention that can be safely applied to all infants and the lowest glucose concentration at which clinically significant neuroglycopenia is avoided.22 It is unlikely that neuroglycopenia can be defined by a single numerical value, since the relationships among glycemic exposure, alternative cerebral fuels, other perinatal stressors, and neuronal function are complex and may be highly infant-specific. At present, there are no reliable tools to assess the neurologic state in relation to the blood glucose concentration in infants.9 Therefore, clinicians need a pragmatic threshold for providing treatment that ensures an adequate supply of metabolic fuels for the developing brain during the neonatal transition.

In our study, continuous interstitial glucose monitoring showed that episodes of low glucose concentrations were common, even in infants thought to have normal blood glucose concentrations and those receiving treatment for hypoglycemia. Although these data could be interpreted as evidence that a lower glycemic threshold for treatment might be safe, they also highlight the need for a considerable margin of safety in setting such a threshold. We were not able to establish an association between the degree of hypoglycemia and neurologic outcomes, most likely because treatment was effective and the infants were monitored closely, so that recurrent or severe hypoglycemia was rare. However, a recent retrospective study showed a graded association between hypoglycemic thresholds of less than 40 mg per deciliter (2.2 mmol per liter) and neurodevelopmental impairment in late-preterm infants, an observation that provides grounds for caution, particularly since the infants were followed for longer than 2 years in that study.23 Furthermore, whereas a lower threshold may reduce the need for intervention, it may not reduce the requirement for screening and associated costs, since hypoglycemia can occur at any stage in the first few days after birth, even in infants with normal initial glucose concentrations.4 Therefore, if lower intervention and treatment thresholds are to be considered, it seems reasonable that they should be evaluated in randomized trials.

A strength of our study is the comprehensive neuropsychometric assessment undertaken, including advanced testing of executive function, vision, and visual processing — skills thought to be particularly affected by neonatal hypoglycemia.24,25 Therefore, we are confident that our results are robust and that we would have detected clinically significant effects of hypoglycemia on neurocognitive processing. Nevertheless, the possibility remains that hypoglycemia affects skills that do not emerge until later phases of development, and repeat assessment at 4.5 years of age is ongoing.

Another strength of our study is the use of continuous interstitial glucose monitoring, which provides recordings every 5 minutes, allowing detailed characterization of glucose profiles over time. Although continuous interstitial glucose monitoring remains an important research tool, our study suggests that at a treatment threshold of 47 mg of glucose per deciliter, screening by means of intermittent blood glucose measurement with the use of a reference method is sufficient. However, this may not be the case at lower glucose thresholds.

A surprising finding of our study is the association of neurosensory impairment, especially cognitive delay, with higher glucose concentrations and less glucose stability, indicated by a larger proportion of time outside the central range of 54 to 72 mg per deciliter in the first 48 hours. Hyperglycemia (a blood glucose concentration of >180 mg per deciliter [10.0 mmol per liter]) is associated with neurodevelopmental impairment in very preterm infants,26 but an association has not previously been reported in more mature infants, especially at glucose concentrations typically regarded as being within the normal range. Furthermore, the estimated effect sizes in our study were relatively large, particularly given the brief glycemic exposure, with increases in the risk of neurosensory impairment ranging from 40 to 77%, and even higher for infants in the uppermost quintiles.

Of concern is the suggestion in our data that rapid correction of hypoglycemia to higher blood glucose concentrations may be associated with a poorer outcome. This finding, in an exploratory analysis, was unexpected and must be interpreted with caution, since the study was observational and unknown confounders cannot be excluded in such studies. Furthermore, the association was seen only in tests of general development (BSID-III), not in tests of processing ability. However, this finding is consistent with evidence from animal models that higher blood glucose concentrations during recovery from hypoglycemia can worsen neurologic damage, at least in part because of increased generation of reactive oxygen species.27,28 Similarly, in both children29 and adults30 in the intensive care unit, the combination of hypoglycemia and highly variable glucose concentrations is strongly associated with mortality. Thus, the manner in which hypoglycemia is treated and the subsequent stability of blood glucose concentrations may be import ant in newborns. We are currently undertaking a randomized trial (ACTRN12613000322730) to assess the long-term effects of different doses and frequencies of dextrose gel administration.

In the present cohort study, neonatal hypoglycemia was not associated with adverse neurologic outcomes when infants were treated with the aim of maintaining a blood glucose concentration of at least 47 mg per deciliter (2.6 mmol per liter), even though transient low glucose concentrations remained common. The possibility that blood glucose concentrations at the high end of the normal range or unstable blood glucose concentrations and rapid correction of hypoglycemia may be harmful requires further investigation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD069622), the Health Research Council of New Zealand (10-399), and the Auckland Medical Research Foundation (1110009).

We thank the children and families who participated in this study, as well as the members of the International Advisory Group: Heidi Feldman, Stanford University School of Medicine; William Hay, University of Colorado School of Medicine; Darrell Wilson, Stanford University School of Medicine; and Robert Hess, McGill Vision Research Unit, Department of Ophthalmology, McGill University.

Footnotes

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development or the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

References

- 1.Burns CM, Rutherford MA, Boardman JP, Cowan FM. Patterns of cerebral injury and neurodevelopmental outcomes after symptomatic neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122:65–74. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boluyt N, van Kempen A, Offringa M. Neurodevelopment after neonatal hypoglycemia: a systematic review and design of an optimal future study. Pediatrics. 2006;117:2231–43. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adamkin DH. Postnatal glucose homeostasis in late-preterm and term infants. Pediatrics. 2011;127:575–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Incidence of neonatal hypoglycemia in babies identified as at risk. J Pediatr. 2012;161:787–91. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.March of Dimes Perinatal Data Center. Special care nursery admissions. 2011 http://www.marchofdimes.org/peristats/pdfdocs/nicu_summary_final.pdf.

- 6.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Signal M, Chase JG, Harding JE. Dextrose gel for neonatal hypoglycaemia (the Sugar Babies Study): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:2077–83. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61645-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ranger M, Chau CM, Garg A, et al. Neonatal pain-related stress predicts cortical thickness at age 7 years in children born very preterm. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76702. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hay WW, Jr, Raju TN, Higgins RD, Kalhan SC, Devaskar SU. Knowledge gaps and research needs for understanding and treating neonatal hypoglycemia: workshop report from Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. J Pediatr. 2009;155:612–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.06.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Williams CE, et al. Cot-side electroencephalography monitoring is not clinically useful in the detection of mild neonatal hypoglycemia. J Pediatr. 2011;159:755–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2011.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Lactate, rather than ketones, may provide alternative cerebral fuel in hypoglycaemic newborns. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2015;100:F161–F164. doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2014-306435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harris DL, Battin MR, Weston PJ, Harding JE. Continuous glucose monitoring in newborn babies at risk of hypoglycemia. J Pediatr. 2010;157(2):198.e1–202.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Signal M, Le Compte A, Harris DL, Weston PJ, Harding JE, Chase JG. Impact of retrospective calibration algorithms on hypoglycemia detection in newborn infants using continuous glucose monitoring. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14:883–90. doi: 10.1089/dia.2012.0111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bayley N. Bayley scales of infant and toddler development. 3rd. San Antonio, TX: PsychCorp; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yu TY, Jacobs RJ, Anstice NS, Paudel N, Harding JE, Thompson B. Global motion perception in 2-year-old children: a method for psychophysical assessment and relationships with clinical measures of visual function. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:8408–19. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-13051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gioia G, Isquith P, Guy S, Kenworthy L. BRIEF: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function: professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kochanska G, Murray KT, Harlan ET. Effortful control in early childhood: continuity and change, antecedents, and implications for social development. Dev Psychol. 2000;36:220–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Carlson SM. Developmentally sensitive measures of executive function in preschool children. Dev Neuropsychol. 2005;28:595–616. doi: 10.1207/s15326942dn2802_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zelazo PD, Reznick JS, Spinazzola J. Representational flexibility and response control in a multistep multilocation search task. Dev Psychol. 1998;34:203–14. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cans C, Dolk H, Platt MJ, Colver A, Prasauskiene A, Krägeloh-Mann I. Recommendations from the SCPE collaborative group for defining and classifying cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. 2007;109:35–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.tb12626.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salmond C, Crampton P, Atkinson J. Wellington, New Zealand: Department of Public Health, University of Otago, Wellington; 2007. NZDep2006 index of deprivation. http://www.otago.ac.nz/wellington/otago020348.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanley CA, Baker L. The causes of neonatal hypoglycemia. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1200–1. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904153401510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornblath M, Hawdon JM, Williams AF, et al. Controversies regarding definition of neonatal hypoglycemia: suggested operational thresholds. Pediatrics. 2000;105:1141–5. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.5.1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kerstjens JM, Bocca-Tjeertes IF, de Winter AF, Reijneveld SA, Bos AF. Neonatal morbidities and developmental delay in moderately preterm-born children. Pediatrics. 2012;130(2):e265–e272. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tam EW, Widjaja E, Blaser SI, Macgregor DL, Satodia P, Moore AM. Occipital lobe injury and cortical visual outcomes after neonatal hypoglycemia. Pediatrics. 2008;122:507–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeBoer T, Wewerka S, Bauer PJ, Georgieff MK, Nelson CA. Explicit memory performance in infants of diabetic mothers at 1 year of age. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2005;47:525–31. doi: 10.1017/s0012162205001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van der Lugt NM, Smits-Wintjens VE, van Zwieten PH, Walther FJ. Short and long term outcome of neonatal hyperglycemia in very preterm infants: a retrospective follow-up study. BMC Pediatr. 2010;10:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-10-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ennis K, Dotterman H, Stein A, Rao R. Hyperglycemia accentuates and ketonemia attenuates hypoglycemia-induced neuronal injury in the developing rat brain. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:84–90. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Suh SW, Gum ET, Hamby AM, Chan PH, Swanson RA. Hypoglycemic neuronal death is triggered by glucose reperfusion and activation of neuronal NADPH oxidase. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:910–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI30077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wintergerst KA, Buckingham B, Gandrud L, Wong BJ, Kache S, Wilson DM. Association of hypoglycemia, hyperglycemia, and glucose variability with morbidity and death in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. 2006;118:173–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bagshaw SM, Bellomo R, Jacka MJ, Egi M, Hart GK, George C. The impact of early hypoglycemia and blood glucose variability on outcome in critical illness. Crit Care. 2009;13:R91. doi: 10.1186/cc7921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.