Abstract

Since the cloning of the critical adapter, LAT (linker for activation of T cells), more than 15 years ago, a combination of multiple scientific approaches and techniques continues to provide valuable insights into the formation, composition, regulation, dynamics, and function of LAT-based signaling complexes. In this review, we will summarize current views on the assembly of signaling complexes nucleated by LAT. LAT forms numerous interactions with other signaling molecules, leading to cooperativity in the system. Furthermore, oligomerization of LAT by adapter complexes enhances intracellular signaling and is physiologically relevant. These results will be related to data from super-resolution microscopy studies that have revealed the smallest LAT-based signaling units and nanostructure.

Keywords: adaptor protein, cooperativity, immunology, signal transduction, T-cell

An Introduction to LAT-based Signaling

T cells have a central role in adaptive immunity, and their activation involves many signaling processes that are spatially and temporally coordinated. T cells differentiate in the thymus, circulate in the blood and lymphatics, and reside in mature lymphatic organs (lymph nodes and spleen). T cell activation requires physical contact between an antigen-presenting cell bearing antigen and a T cell, whose clonally defined antigen receptor (TCR)2 recognizes and binds its cognate peptide antigen, which is bound to a molecule encoded by the major histocompatibility complex (pMHC). This initial binding event must then be translated into a productive signal that involves the recruitment and activation of specific molecules within the lymphocyte to generate a successful immune response.

Genetic and biochemical studies have revealed the numerous molecules in the signaling cascades involved in immune function. Activation of the TCR results in engagement of Src family kinases, Lck and Fyn, and recruitment of the Syk family kinase, ZAP-70, to the TCR where, in a process not fully understood, these tyrosine kinases become activated. ZAP-70 then phosphorylates the membrane-bound adapter protein, LAT (linker for activation of T cells) (1). Phosphorylated LAT associates with critical proteins including enzymes and adapters that regulate most TCR-dependent responses. This association with multiple signaling proteins allows LAT to serve as a point of signal diversification and amplification downstream of the TCR. The essential nature of LAT complexes to TCR signaling was revealed by studies in Jurkat T cell lines lacking expression of LAT that are severely defective in several TCR-mediated signaling events (2, 3). In animal studies where either LAT is deleted (4, 5) or knock-in mutations blocking LAT phosphorylation are introduced, thymocyte development is completely blocked (6, 7). Furthermore, deletion of LAT in mature T cells severely compromises T cell signaling (8, 9).

Microscopy Reveals Signaling Microclusters

Microscopy has been vital in bridging the gap between the study of large immune structures such as tissues and cells, and the small signaling complexes identified by biochemistry. Light microscopy has revealed a specialized structure called the immune synapse (IS) formed between T cells and antigen-presenting cells upon successful TCR triggering. The complex structure of the mature IS and its function are reviewed elsewhere (10). Prior to IS formation and within the mature IS, signaling occurs within microclusters, structures of roughly 200–500 nm that are enriched in TCRs, costimulatory molecules, and multiple signaling molecules, including upstream kinases, adapters including LAT, and downstream effectors (11, 12). The enrichment of these signaling molecules in microclusters creates a localized environment in which TCR signaling events can be rapidly propagated to downstream effectors. The functional properties that result from molecular clustering of LAT-containing complexes is a significant question, but one that has been difficult to resolve due to both the essential nature of LAT to TCR signaling (see above) and the technical challenges of distinguishing between the role of individual LAT complexes versus larger LAT clusters.

The spatial structure of the immune system is thus highly organized at many size scales: from the organ level, cells, and macromolecular structures between cells, to microclusters to small protein complexes (Fig. 1). In this review, we attempt to understand the activation of T cells over multiple size scales by focusing on LAT, a protein that functions as a signaling hub in T cell activation. We will first focus on LAT-nucleated protein interactions, and then summarize current views on cooperativity and adapter-mediated oligomerization of LAT, and finally we will review the super-resolution microscopy studies that demonstrate that LAT and other signaling molecules are found in nanostructures within larger microclusters

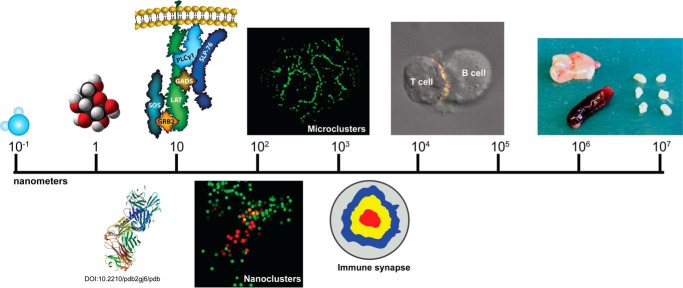

FIGURE 1.

Hierarchy of scale for studying the immune system. Important biological entities vary widely in size. Important small molecules such as water and glucose are shown on the left side of the scale. Next are two representations of protein complexes: a ribbon diagram of the T cell receptor complexed to antigen and MHC (Protein Data Bank entry 2GJ6 (66)) as well as a graphic of a LAT-based signaling complex. These complexes can be arranged into nanoclusters; a localization microscopy image shows LAT molecules in red surrounded by SLP-76 molecules shown in green. Next, a confocal image shows diffraction-limited microclusters in an activated Jurkat cell stained with an antibody to phosphorylated LAT. Signaling molecules can be arranged in large-scale patterns such as the immune synapse shown in graphic form and as part of a two-cell conjugate between a Jurkat cell and a superantigen-pulsed B cell. Finally, these molecules lead to activation of the immune system, represented by various lymphoid organs: thymus (top left), spleen (bottom left), and lymph nodes (right, axillary, brachial, and inguinal).

LAT Nucleates Signaling Complexes

LAT has a very short extracellular region, a transmembrane domain, and a long cytoplasmic region containing multiple tyrosines that are rapidly phosphorylated following TCR stimulation (13). These Tyr(P) motifs serve as binding sites for SH2 domain-containing proteins, including PLC-γ1, Grb2, and Gads (14–16), allowing the nucleation of multiple signaling complexes on LAT, which are essential for downstream signaling. Grb2 and Gads consist of an SH2 domain surrounded by two SH3 domains, which bind to proline-rich sequences in the Ras guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), Son of Sevenless (Sos), and the adapter molecule SLP-76, respectively. SLP-76 further recruits molecules Nck, Vav, and Itk to the LAT complex. Additional molecular interactions are also possible because Grb2 and Gads, via their SH3 domains, and SLP-76, via its Tyr(P) motifs and SH2 domain, can bind other proteins. PLC-γ1 has a catalytic domain as well as peptide and phospholipid interaction domains that are important for Ca2+ influx and protein kinase C activation (17). The modular architecture of protein domains in LAT-associated signaling proteins can be used in a combinatorial fashion to generate flexibility, and provides for the conversion of the same signal input into potentially a large number of different outputs (18).

The juxtamembrane region of LAT contains two cysteine residues, Cys-26 and Cys-29, that are critical for LAT palmitoylation. As a result of palmitoylation, LAT is localized in lipid rafts or membrane microdomains that are resistant to detergents (19). Reflecting the intense debate about the physiological role of lipid rafts (20, 21), the importance of raft localization for LAT function has been controversial. Although early studies using cysteine mutants concluded that LAT localization to lipid rafts was required for function (19), later studies demonstrated that targeting of LAT to the plasma membrane is sufficient for its function, irrespective of its lipid raft localization (22, 23).

In addition to being a positive regulator of T cell signaling, LAT also recruits several negative regulatory proteins, including kinases, phosphatases, and ubiquitin ligases, which ultimately leads to signal termination (17). LAT is also subject to ubiquitylation, and ubiquitin-resistant mutants of LAT display enhanced signaling (24, 25). The above-described protein-protein interactions and post-translational modifications were mapped by candidate coimmunoprecipitation studies to evaluate interactions, one protein at a time. A recent study using mass spectrometry revealed 90 signaling proteins associated with LAT, ZAP-70, and SLP-76, many of which have not been previously known to participate in TCR signaling (26). Thus, the high-resolution power of newly available technologies will lead to a more comprehensive understanding of the LAT signaling hub.

The intracellular region of LAT comprises ∼200 residues and has intrinsically disordered characteristics (27). Intrinsically disordered proteins (IDPs) or proteins with intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs) frequently function as hubs in protein-interaction networks due to their physical characteristics (28). The flexibility of IDRs allows for interactions with different partners with high specificity, but low affinity, which enables dynamic regulation of signaling complexes. The inherently unfolded conformation provides accessible sites for post-translational modifications. Because of its unstructured nature, the LAT cytosolic region is likely to have a larger intermolecular interface than a compact, well folded protein, which would improve the accessibility of LAT tyrosines for kinases and binding partners. Both modular protein domains as well as IDRs contribute to cooperative effects in LAT complex stabilization as described below.

Cooperativity Stabilizes LAT-based Signaling Complexes

Cooperative interactions among proteins are characterized by an altered affinity due to multiple binding interactions that influence each other. They can lead to nonlinear feedbacks in biochemical networks (29). A multitude of studies indicate that cooperative interactions among LAT-associated proteins drive the assembly of spatial and temporal specific signaling complexes.

Evidence for cooperativity within LAT-based signaling complexes begins with proteins that interact directly with LAT. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the LAT residues, Tyr-132, Tyr-171, Tyr-191, and Tyr-226, induces interactions with the SH2 domain-containing proteins PLC-γ1, Grb2, and Gads (14–16). A binding preference among these proteins has been observed in co-precipitation or pulldown studies with PLC-γ1 binding at Tyr(P)-132, Gads at Tyr(P)-191 and Tyr(P)-171, and Grb2 at Tyr(P)-171, Tyr(P)-191, and Tyr(P)-226 (16). Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) binding studies with synthetic peptides and purified recombinant proteins have demonstrated that Gads and Grb2 have a 50–100-fold weaker affinity to Tyr(P)-132, whereas the PLC-γ1 SH2 domain has a 10-fold stronger affinity to Tyr(P)-132. Although these data partially account for the observed binding preferences, Grb2 and Gads do not have substantially different affinities for the Tyr(P)-171, Tyr(P)-191, or Tyr(P)-226 sites. Therefore, the binding affinities alone do not sufficiently account for the above-described binding preferences of PLC-γ1 and Gads (30). Instead the results of multiple studies suggest that cooperative interactions contribute to the observed binding preferences. For instance, it was demonstrated that tyrosine to phenylalanine mutations to the Gads/Grb2-binding residues (Y171F, Y191F, Y226F) also reduced the recruitment of PLC-γ1 to LAT, likely reflecting the indirect interaction of these molecules via Gads and SLP-76 (15, 31). Further evidence for these interactions to be cooperative is that the phosphorylated LAT residues must be on the same LAT molecule, and cannot function in trans among multiple LAT molecules (14).

Observations of cooperativity within LAT-based signaling complexes have also been made from proteins that interact indirectly with LAT, including SLP-76 and Sos1. Phosphorylation sites of SLP-76 bind the SH2 domains of the kinase, Itk, and the guanine exchange factor, Vav; however, neither protein will associate with SLP-76 in the absence of the other (32). Furthermore, as detailed below, SLP-76 requires the C-terminal SH2 domain for recruitment into microclusters (33, 34). Interestingly, the C-terminal SH3 domain of Gads and the SH3 domain of PLC-γ1 induce a disorder-order transition in SLP-76, and this may have a cooperative effect on the assembly of the SLP-76 multiprotein complex on LAT (30, 35).

LAT Oligomerization by Multipoint Binding of Grb2 to LAT and Sos1

Recently, it has been recognized that multivalency, whereby a molecule can make multiple distinct binding contacts and thus oligomerize signaling complexes, is an important form of cooperativity in cellular signaling (36). In the T cell, Sos1 is recruited to LAT via the adapter Grb2, with the proline-rich region (PRR) of Sos1 interacting with Grb2 via one of its SH3 domains, and the SH2 domain of Grb2 interacting with LAT on any of three phosphorylated Tyr residues (171, 191, and 226) (15). Detailed analysis using mutated forms of LAT showed that at least two of these sites must be phosphorylated for co-immunoprecipitation between LAT and Grb2 (16), suggesting some level of cooperativity in Grb2-LAT complexes, such that individual interactions are destabilized.

Biophysical studies provided interesting insights into the individual and combined interactions between LAT, Grb2, and Sos1. ITC studies using purified Grb2 and phosphorylated LAT peptides showed multipoint binding between LAT and Grb2, such that a fully phosphorylated LAT could simultaneously interact with three Grb2 molecules (37). Furthermore, analysis of singly versus doubly phosphorylated LAT peptides revealed cooperativity upon binding to multiple Grb2 molecules (38), confirming the earlier immunoprecipitation studies. Similarly, ITC between Grb2 and the PRR of Sos1 revealed two distinct Grb2-binding sites on Sos1, such that Grb2 and Sos1 formed a 2:1 complex (37). Moreover, analytical ultracentrifugation studies revealed that Grb2-Sos1-Grb2 complexes could cross-link LAT peptides, suggesting that these complexes could act as a scaffold to promote LAT oligomerization (Fig. 2).

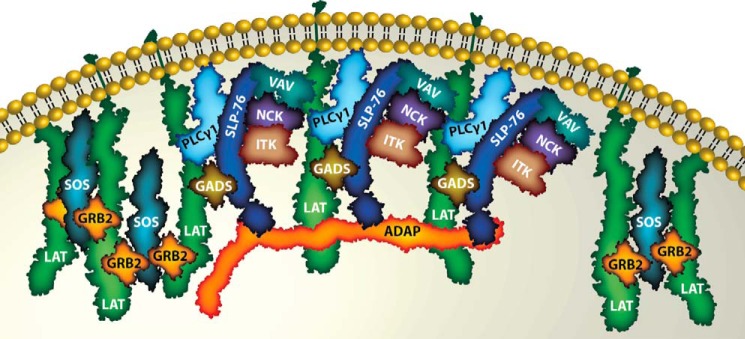

FIGURE 2.

Formation of LAT oligomers following T cell activation. Binding of two Grb2 molecules to a single Sos1 protein allows the formation of LAT oligomers. Both the GEF activity of Sos1 and multipoint binding are needed for full T cell activation. The binding of ADAP to multiple SLP-76 molecules promotes SLP-76 clustering and could potentially induce LAT oligomers as well.

Microscopic analysis of LAT microcluster formation as a surrogate measurement of LAT oligomerization confirmed a role for Grb2 and Sos1 in LAT oligomerization. An ectopically expressed LAT-YFP fusion protein, unable to bind Grb2 (LAT3YF mutant), was not incorporated into microclusters following anti-CD3ϵ stimulation (37). More directly, CD3ϵ-stimulated endogenous LAT microcluster formation was defective following Grb2 depletion in human T cells (39) and in Sos1−/− DP thymocytes (40). In each case, defective TCR-dependent ERK activation, PLCγ-1 phosphorylation, and downstream calcium flux were observed (37, 39, 40). However, it is difficult to attribute these downstream signaling defects directly to a loss of LAT oligomerization, due to the intertwined nature between interactions required for the recruitment of individual complexes to LAT and those required to promote LAT oligomerization. For example, although the LAT3YF mutation blocks LAT microcluster formation (37), this same mutation blocks the recruitment of both the Grb2-Sos1 and the PLCγ-1-Gads-SLP76-Itk complexes to LAT (15, 16). Similarly, depletion of either Grb2 or Sos1 prevents the recruitment of Sos1 RasGEF activity to LAT at the membrane. These overlapping functions make it difficult to determine whether any changes in TCR-dependent development (4–8, 41–43) or signaling (8, 15, 16, 37, 39, 40) observed by LAT deletion, LAT mutation, or Grb2/Sos1 deletion can be attributed directly to a loss of LAT oligomerization.

In Vivo Studies Reveal a Role for Sos1-dependent LAT Oligomerization in the Thymus

To overcome these limitations, we devised a transgenic system that allowed us to independently restore Sos1−/− T cells with either Sos1 RasGEF activity or the ability of Sos1 to nucleate Grb2-dependent LAT oligomerization (40). A catalytically inactive mutant of Sos1 unable to activate Ras (F929A) was still able to bind Grb2 and promote LAT microcluster formation, allowing the restoration of the Sos1 scaffolding function without its RasGEF activity. In contrast, a fusion construct in which the PRR of Sos1 was replaced with the SH2 domain of Grb2 (Sos-SH2) directly recruited Sos1 RasGEF activity to LAT, but lacked the ability to cross-link LAT molecules and promote its oligomerization.

Assessment of CD3ϵ-stimulated signaling in isolated thymocytes from Sos1−/− mice expressing these constructs revealed that the two Sos1 “functional domains” signal independently downstream of the TCR. Sos1-dependent Ras/ERK activation required the recruitment of Sos1 RasGEF activity to LAT, but was completely independent of Sos1 scaffolding function. In contrast, TCR-driven LAT phosphorylation, PLCγ-1 phosphorylation, and downstream calcium flux required Sos1-dependent LAT oligomerization, but were independent of Sos1 RasGEF activity.

To determine the functional relevance of Sos1-dependent LAT oligomerization, we further assessed receptor-driven thymocyte development in these mice. At early stages of T cell development in the thymus, a surrogate TCR known as the pre-TCR is employed. Thymocytes must progress and survive through multiple steps, including TCRβ chain selection, as well as positive and negative selection before achieving full functional status (45). Previous studies had shown a role for Sos1 in both pre-TCR-driven proliferation during β-selection (41) and TCR-dependent negative selection (42) (for a detailed review of Ras signaling during T cell development, see Ref. 46). Assessment of TCR-dependent negative selection in these mice revealed that this process required Sos1 RasGEF activity, but was independent of Sos1-driven LAT oligomerization (40), confirming the Ras dependence of this developmental checkpoint.

In contrast, pre-TCR-driven proliferation required both Sos1 RasGEF activity and scaffolding functions. Restoration of either Sos1 RasGEF activity or its scaffolding function alone failed to restore normal thymocyte proliferation. In contrast, simultaneous restoration of these two signals in trans, accomplished by simultaneous expression of the F929A and Sos-SH2 transgenes in a Sos1−/− background, completely reversed the Sos1−/− phenotype. Both normal pre-TCR-driven proliferation and activation of downstream signaling pathways were observed in these mice, confirming that Sos1 has two independent functions that act in concert downstream of the TCR. Thus, Sos1-mediated oligomerization is functionally relevant in a complex developmental pathway.

Multipoint Binding of SLP-76 by ADAP

Combined interactions are also important in recruitment of SLP-76-associated proteins to LAT. SLP-76, which binds indirectly to LAT via Gads and is critical for appropriate T cell responses, modulates signaling complex assembly by direct interactions with enzymes and adapters, including PLC-γ1, Vav, HPK1, Nck, Gads, and ADAP (17). In confocal imaging studies of T cell lines and peripheral blood lymphocytes, these and other proteins were observed in microclusters (47–49). Interestingly, SLP-76 microclusters required both the Gads-binding region and, unexpectedly, a completely different region, the C-terminal SH2 domain of SLP-76 (33). This result indicates that association with LAT is insufficient to incorporate SLP-76 into LAT-containing microclusters. Recently, direct binding of the SLP-76 SH2 domain to three phosphorylated tyrosine residues, Tyr(P)-595, Tyr(P)-651, and Tyr(P)-771, of the adapter ADAP was demonstrated along with the potential for ADAP to oligomerize SLP-76 in vitro (34). These results suggested a mechanism whereby SLP-76 microclusters are stabilized by multipoint binding of the C-terminal SH2 domain to phosphorylated ADAP sites (Fig. 2).

Multicolor confocal imaging studies of Jurkat cell lines supported and extended the multipoint binding model by demonstrating a role for all three ADAP sites in microcluster assembly and stabilization. Single tyrosine to phenylalanine point mutations to any one of the three ADAP sites reduced the total amount of SLP-76 microclusters, co-localization between SLP-76 and ADAP, and the recruitment of both SLP-76 and ADAP into microclusters. Further live cell imaging studies demonstrated a reduction in both microcluster assembly and persistence associated with a loss of the ADAP-binding sites. These results argue that ADAP is critical for the oligomerization of SLP-76. In future studies, it will be important to examine whether multipoint binding of SLP-76 to ADAP also impacts LAT oligomerization. Regardless, it appears that there are multiple mechanisms for oligomerization of TCR activation-induced signaling complexes.

Multivalent LAT and Phase Transitions

As described above, cross-linking of LAT can arise from the formation of a 2:1 complex between Grb2 and Sos1. The 2:1 Grb2-Sos1 complex can bridge two LAT molecules through interactions of the Grb2 SH2 domain with LAT phosphotyrosines on two separate LAT molecules. However, LAT contains nine conserved tyrosines in its cytoplasmic tail, and of these, the distal three are located in YXNX motifs that bind the SH2 domain of Grb2 when phosphorylated (51). Thus, the valence of LAT for Grb2 can vary from 0 to 3 depending on the number of phosphorylated LAT tyrosines.

The distribution of LAT valence states depends on the concentration of the activated kinase ZAP-70 (52), which in turn depends upon TCR activation. Theoretical modeling studies predicted that the valence of LAT for Grb2 is critical in determining the nature and extent of aggregation. Monovalent LAT-Grb2 would block LAT chain formation, whereas bivalent LAT-Grb2 would prevent LAT branching. Thus, LAT aggregation would be significantly reduced in the presence of mono- and bivalent LAT. Such states might be favored by enhanced LAT-Gads-SLP-76 binding as Gads competes for two of the Grb2-binding sites. In contrast, a dramatic rise in LAT oligomerization would occur when the valence for Grb2 switches from 2 to 3, at which point equilibrium theory predicts the formation of a gel-like phase for oligomerized LAT (53, 54).

Phase separation might promote compartmentalization of LAT and LAT-binding partners in transient structures, thus changing their local concentrations. This increased proximity of signaling molecules can greatly facilitate various biochemical processes (55). Local concentration of enzymes in proximity with their substrates and even with each other would promote enzymatic reactions and autoactivation that would not have been possible in solution because of the intrinsic low affinity of the interactions. Increased proximity between molecules in different complexes might enhance signal propagation between adjacent complexes. Moreover, LAT molecules within these compartments might be better protected from tyrosine phosphatases and thereby increase their signaling output.

This sort of phase separation has been shown to occur in other signaling systems as well. For example, in the case of the actin regulatory protein, Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP), a phase transition resulted in a sharp increase in activity toward an actin nucleation factor Arp2/3 complex. In this system, the phase transition was regulated by the degree of phosphorylation of nephrin, a known WASP interactor (56). Thus, in both LAT and WASP systems, kinase activity potentially regulates the extent of oligomerization that then leads to phase transition with functional consequences.

Super-resolution Studies Reveal LAT Nanoclusters

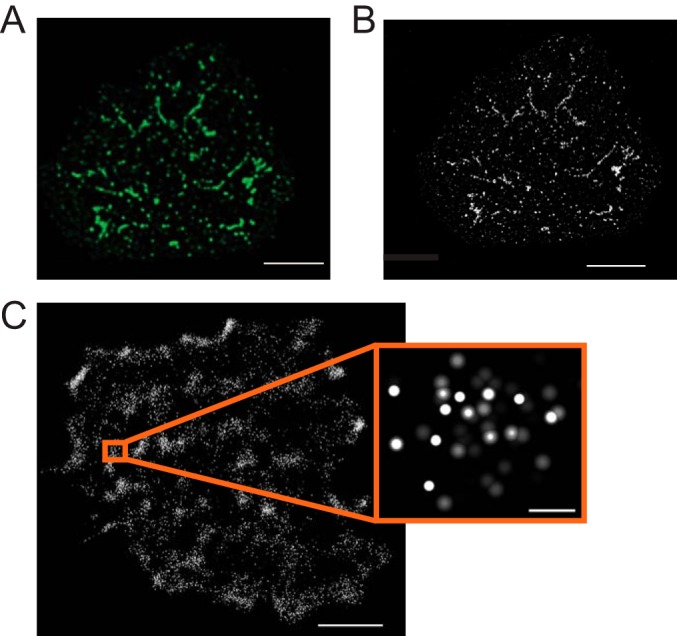

The size of TCR activation-induced signaling complexes is a long-standing question that has been addressed using a variety of imaging techniques. LAT-containing signaling microclusters appear to be 200–500 nm in diameter when visualized on a stimulatory surface by diffraction-limited light microscopy (Fig. 3A) (11, 12). LAT clusters are very dynamic, and studies describing live cell imaging of LAT as well as the debate about the cellular pool of LAT contributing to T cell activation are reviewed elsewhere (17, 57).

FIGURE 3.

Imaging LAT-based complexes at different scales. A, diffraction-limited, deconvolved image of a Jurkat T cell activated on a coverslip coated with anti-TCR (anti-CD3ϵ) antibodies and stained for phosphorylated, active LAT. Clusters of activated LAT appear as large puncta, several hundreds of nanometers in size. Scale bar = 3 μm. B, deconvolved STED image of the same cell reveals that microclusters are actually much smaller and that the largest are often several small clusters close together. The smallest of these clusters are near 50 nm in size. Scale bar = 3 μm. C, localization image of an activated Jurkat T cell showing the locations of LAT molecules conjugated to the photoactivatable protein, Dronpa. Scale bar = 2 μm. The inset shows a group of individual LAT molecules from one of the denser areas. Scale bar = 100 nm.

Since LAT microclusters were first visualized, most signaling molecules recruited to LAT have been localized to these structures, thus leading to the realization that microclusters are the primary functional signaling unit. Microclusters have been extensively studied in a wide range of model systems and in ex vivo T cells (58, 59). However, the size and molecular composition of individual signaling complexes within the microcluster are well below the limit of conventional light microscopy, limiting our ability to understand the complexity of signaling events that occur within these structures. Recently, new developments in optical methods have enabled significant improvements in spatial resolution and have allowed visualization of T cell signaling at the nanometer scale.

When viewed using stimulation emission depletion microscopy (STED), a form of super-resolution microscopy reviewed in Ref. 60, most LAT microclusters are clearly composed of smaller clusters in the range of 50–70 nm, near the limit of STED detection (Fig. 3B). Recently, many researchers have turned to single molecule localization microscopy (photo activation localization microscopy (PALM) and stochastic optical reconstruction microscopy (STORM), reviewed in Ref. 61) to visualize individual LAT molecules at even higher resolution, and thus determine the size and organization of LAT clusters (Fig. 3C). These studies revealed that LAT is clustered in both unactivated and activated cells and that the extent of clustering increased after TCR activation (62, 63).

Two-color PALM has been used to image LAT pairwise with other signaling proteins. Studies assessing pairwise interaction between LAT and TCRζ have shown conflicting results. In one study, LAT and TCRζ nanoclusters mixed in unstimulated cells. Upon stimulation, LAT nanoclusters only partially overlapped with nanoclusters containing activated TCRζ and ZAP-70, thus forming “hot spots” for LAT phosphorylation (63). These conclusions contrast with another study that emphasized the role of larger “protein islands” of TCRζ and LAT that concatenate, but do not mix upon T cell stimulation (62). In contrast, LAT clusters recruited Grb2 regardless of size, indicating that even small nanoclusters contain phosphorylated LAT. Interestingly, LAT and SLP-76 were reported to form nanostructures with LAT tending to be in the center and SLP-76 distributed on the outside (63) (Fig. 1). How small-scale organization of LAT structures influences T cell activation is a key unanswered question.

How Do Insights from LAT-based Complexes Apply to Other Systems?

Technical advances in the past few years have transformed our view of LAT complexes and clusters. Super-resolution imaging revealed that the classic LAT microclusters visualized by diffraction-limited microscopy more than a decade ago are in fact made up of LAT nanoclusters that exist in a wide range of cluster sizes in a continuous distribution. In vitro approaches, using purified proteins and biophysical techniques, have uncovered LAT oligomers that have in vivo function. Although all LAT clusters, irrespective of size, get phosphorylated, as evidenced by Grb2 recruitment (as shown by PALM), whether the smallest clusters can lead to productive T cell signaling or whether larger LAT aggregates are required for certain TCR-driven events remains an important question.

Higher-order oligomers have been observed in several signaling cascades (55) and allow for signal amplification, impart threshold response and reduction of biological noise, and render temporal and spatial control of signaling. Several adapter proteins and growth factor receptors have multiple Grb2-binding sites, so Grb2-mediated oligomerization of such proteins themselves might play a role in these signaling systems. In that context, in contrast to the widely held view that dimeric EGF receptor (EGFR) is the predominant signaling unit, some studies have implicated higher-order EGFR oligomers as the dominant species associated with the ligand-activated EGFR tyrosine kinase activation (50, 64, 65). Recent evidence that higher-order oligomers of EGFR bind Grb2 with high efficiency points to EGFR clustering and adapter binding in an oligomeric complex (44).

Key questions for future studies will involve understanding how complex cooperative interactions and oligomer formation control signal outcomes. Tractable in vitro systems can be used to generate binding parameters that can be used to build models describing the behavior of LAT-containing complexes. For example, phase transitions might be a general feature of multivalent signaling systems that impart nonlinearity in signaling pathways. Better definitions of binding parameters could also inform the design of inhibitors of signaling complex formation. Finally, single particle cryo-EM or crystal structure data could give us transformational insights into the structural basis of clustering and cell signaling.

The LAT signaling hub can be seen as a system of heterogeneous molecular organization and dynamic protein assembly, where gaining spatial and temporal information on specific proteins at the nanoscale could yield fundamentally new insights into signaling. These insights might extend to other clinically relevant signaling systems, such as those activated by growth factors, cytokines, or cell-cell contact. For T cells in particular, these insights might have impact on the control of T cells in treatment of autoimmune diseases or graft rejection and the clinical use of T cells in immunotherapy directed at cancer or chronic infection.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate the work of several former members of the laboratory who contributed to the work reviewed in this manuscript. Many important contributions could not be incorporated due to space limitations. We thank Dr. Chang Yi for helpful discussions and Dr. Connie Sommers for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, NCI, Center for Cancer Research (CCR). This is the fourth article in the Thematic Minireview series “Protein Interactions, Structures, and Networks.” The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

- TCR

- T cell receptor

- LAT

- linker for activation of T cells

- IS

- immune synapse

- GEF

- guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- Sos

- Son of Sevenless

- IDR

- intrinsically disordered region

- ITC

- isothermal titration calorimetry

- PRR

- proline-rich region

- WASP

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- STED

- stimulation emission depletion microscopy

- PALM

- photo activation localization microscopy

- PLC

- phospholipase C

- SH

- Src homology

- ADAP

- adhesion and degranulation-promoting adapter protein

- EGFR

- EGF receptor.

References

- 1.Chakraborty A. K., and Weiss A. (2014) Insights into the initiation of TCR signaling. Nat. Immunol. 15, 798–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Finco T. S., Kadlecek T., Zhang W., Samelson L. E., and Weiss A. (1998) LAT is required for TCR-mediated activation of PLCγ1 and the Ras pathway. Immunity 9, 617–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W., Irvin B. J., Trible R. P., Abraham R. T., and Samelson L. E. (1999) Functional analysis of LAT in TCR-mediated signaling pathways using a LAT-deficient Jurkat cell line. Int. Immunol. 11, 943–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen S., Zhu M., Lau J., Chuck M., and Zhang W. (2009) The essential role of LAT in thymocyte development during transition from the double-positive to single-positive stage. J. Immunol. 182, 5596–5604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhang W., Sommers C. L., Burshtyn D. N., Stebbins C. C., DeJarnette J. B., Trible R. P., Grinberg A., Tsay H. C., Jacobs H. M., Kessler C. M., Long E. O., Love P. E., and Samelson L. E. (1999) Essential role of LAT in T cell development. Immunity 10, 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nuñez-Cruz S., Aguado E., Richelme S., Chetaille B., Mura A. M., Richelme M., Pouyet L., Jouvin-Marche E., Xerri L., Malissen B., and Malissen M. (2003) LAT regulates γ/δ T cell homeostasis and differentiation. Nat. Immunol. 4, 999–1008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sommers C. L., Menon R. K., Grinberg A., Zhang W., Samelson L. E., and Love P. E. (2001) Knock-in mutation of the distal four tyrosines of linker for activation of T cells blocks murine T cell development. J. Exp. Med. 194, 135–142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mingueneau M., Roncagalli R., Grégoire C., Kissenpfennig A., Miazek A., Archambaud C., Wang Y., Perrin P., Bertosio E., Sansoni A., Richelme S., Locksley R. M., Aguado E., Malissen M., and Malissen B. (2009) Loss of the LAT adaptor converts antigen-responsive T cells into pathogenic effectors that function independently of the T cell receptor. Immunity 31, 197–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen S., Chuck M. I., Zhu M., Fuller D. M., Yang C. W., and Zhang W. (2010) The importance of LAT in the activation, homeostasis, and regulatory function of T cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 35393–35405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dustin M. L., Chakraborty A. K., and Shaw A. S. (2010) Understanding the structure and function of the immunological synapse. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a002311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bunnell S. C., Hong D. I., Kardon J. R., Yamazaki T., McGlade C. J., Barr V. A., and Samelson L. E. (2002) T cell receptor ligation induces the formation of dynamically regulated signaling assemblies. J. Cell Biol. 158, 1263–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yokosuka T., Sakata-Sogawa K., Kobayashi W., Hiroshima M., Hashimoto-Tane A., Tokunaga M., Dustin M. L., and Saito T. (2005) Newly generated T cell receptor microclusters initiate and sustain T cell activation by recruitment of Zap70 and SLP-76. Nat. Immunol. 6, 1253–1262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W., Sloan-Lancaster J., Kitchen J., Trible R. P., and Samelson L. E. (1998) LAT: the ZAP-70 tyrosine kinase substrate that links T cell receptor to cellular activation. Cell 92, 83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin J., and Weiss A. (2001) Identification of the minimal tyrosine residues required for LAT function. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29588–29595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang W., Trible R. P., Zhu M., Liu S. K., McGlade C. J., and Samelson L. E. (2000) Association of Grb2, Gads, and phospholipase C-γ1 with phosphorylated LAT tyrosine residues: effect of LAT tyrosine mutations on T cell antigen receptor-mediated signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23355–23361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu M., Janssen E., and Zhang W. (2003) Minimal requirement of tyrosine residues of linker for activation of T cells in TCR signaling and thymocyte development. J. Immunol. 170, 325–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balagopalan L., Coussens N. P., Sherman E., Samelson L. E., and Sommers C. L. (2010) The LAT story: a tale of cooperativity, coordination, and choreography. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a005512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pawson T., and Nash P. (2003) Assembly of cell regulatory systems through protein interaction domains. Science 300, 445–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang W., Trible R. P., and Samelson L. E. (1998) LAT palmitoylation: its essential role in membrane microdomain targeting and tyrosine phosphorylation during T cell activation. Immunity 9, 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horejsi V., and Hrdinka M. (2014) Membrane microdomains in immunoreceptor signaling. FEBS Lett. 588, 2392–2397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kenworthy A. K. (2008) Have we become overly reliant on lipid rafts? Talking Point on the involvement of lipid rafts in T-cell activation. EMBO Rep. 9, 531–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hundt M., Harada Y., De Giorgio L., Tanimura N., Zhang W., and Altman A. (2009) Palmitoylation-dependent plasma membrane transport but lipid raft-independent signaling by linker for activation of T cells. J. Immunol. 183, 1685–1694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhu M., Shen S., Liu Y., Granillo O., and Zhang W. (2005) Cutting Edge: localization of linker for activation of T cells to lipid rafts is not essential in T cell activation and development. J. Immunol. 174, 31–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balagopalan L., Ashwell B. A., Bernot K. M., Akpan I. O., Quasba N., Barr V. A., and Samelson L. E. (2011) Enhanced T-cell signaling in cells bearing linker for activation of T-cell (LAT) molecules resistant to ubiquitylation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 2885–2890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brignatz C., Restouin A., Bonello G., Olive D., and Collette Y. (2005) Evidences for ubiquitination and intracellular trafficking of LAT, the linker of activated T cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1746, 108–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roncagalli R., Hauri S., Fiore F., Liang Y., Chen Z., Sansoni A., Kanduri K., Joly R., Malzac A., Lähdesmäki H., Lahesmaa R., Yamasaki S., Saito T., Malissen M., Aebersold R., Gstaiger M., and Malissen B. (2014) Quantitative proteomics analysis of signalosome dynamics in primary T cells identifies the surface receptor CD6 as a Lat adaptor-independent TCR signaling hub. Nat. Immunol. 15, 384–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sangani D., Venien-Bryan C., and Harder T. (2009) Phosphotyrosine-dependent in vitro reconstitution of recombinant LAT-nucleated multiprotein signalling complexes on liposomes. Mol. Membr Biol. 26, 159–170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright P. E., and Dyson H. J. (2015) Intrinsically disordered proteins in cellular signalling and regulation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 16, 18–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Qian H. (2012) Cooperativity in cellular biochemical processes: noise-enhanced sensitivity, fluctuating enzyme, bistability with nonlinear feedback, and other mechanisms for sigmoidal responses. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 179–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Houtman J. C. D., Higashimoto Y., Dimasi N., Cho S., Yamaguchi H., Bowden B., Regan C., Malchiodi E. L., Mariuzza R., Schuck P., Appella E., and Samelson L. E. (2004) Binding specificity of multiprotein signaling complexes is determined by both cooperative interactions and affinity preferences. Biochemistry 43, 4170–4178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hartgroves L. C., Lin J., Langen H., Zech T., Weiss A., and Harder T. (2003) Synergistic assembly of Linker for Activation of T cells signaling protein complexes in T cell plasma membrane domains. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20389–20394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dombroski D., Houghtling R. A., Labno C. M., Precht P., Takesono A., Caplen N. J., Billadeau D. D., Wange R. L., Burkhardt J. K., and Schwartzberg P. L. (2005) Kinase-independent functions for Itk in TCR-induced regulation of Vav and the actin cytoskeleton. J. Immunol. 174, 1385–1392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bunnell S. C., Singer A. L., Hong D. I., Jacque B. H., Jordan M. S., Seminario M. C., Barr V. A., Koretzky G. A., and Samelson L. E. (2006) Persistence of cooperatively stabilized signaling clusters drives T-cell activation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26, 7155–7166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coussens N. P., Hayashi R., Brown P. H., Balagopalan L., Balbo A., Akpan I., Houtman J. C., Barr V. A., Schuck P., Appella E., and Samelson L. E. (2013) Multipoint binding of the SLP-76 SH2 domain to ADAP is critical for oligomerization of SLP-76 signaling complexes in stimulated T cells. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 4140–4151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Q., Berry D., Nash P., Pawson T., McGlade C. J., and Li S. S. (2003) Structural basis for specific binding of the Gads SH3 domain to an RxxK motif-containing SLP-76 peptide: a novel mode of peptide recognition. Mol. Cell 11, 471–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whitty A. (2008) Cooperativity and biological complexity. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 435–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Houtman J. C., Yamaguchi H., Barda-Saad M., Braiman A., Bowden B., Appella E., Schuck P., and Samelson L. E. (2006) Oligomerization of signaling complexes by the multipoint binding of GRB2 to both LAT and SOS1. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 798–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Houtman J. C., Brown P. H., Bowden B., Yamaguchi H., Appella E., Samelson L. E., and Schuck P. (2007) Studying multisite binary and ternary protein interactions by global analysis of isothermal titration calorimetry data in SEDPHAT: application to adaptor protein complexes in cell signaling. Protein Sci. 16, 30–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bilal M. Y., and Houtman J. C. (2015) GRB2 nucleates T cell receptor-mediated LAT clusters that control PLC-γ1 activation and cytokine production. Front Immunol. 6, 141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kortum R. L., Balagopalan L., Alexander C. P., Garcia J., Pinski J. M., Merrill R. K., Nguyen P. H., Li W., Agarwal I., Akpan I. O., Sommers C. L., and Samelson L. E. (2013) The ability of Sos1 to oligomerize the adaptor protein LAT is separable from its guanine nucleotide exchange activity in vivo. Sci. Signal. 6, ra99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kortum R. L., Sommers C. L., Alexander C. P., Pinski J. M., Li W., Grinberg A., Lee J., Love P. E., and Samelson L. E. (2011) Targeted Sos1 deletion reveals its critical role in early T-cell development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 12407–12412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kortum R. L., Sommers C. L., Pinski J. M., Alexander C. P., Merrill R. K., Li W., Love P. E., and Samelson L. E. (2012) Deconstructing Ras signaling in the thymus. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32, 2748–2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jang I. K., Zhang J., Chiang Y. J., Kole H. K., Cronshaw D. G., Zou Y., and Gu H. (2010) Grb2 functions at the top of the T-cell antigen receptor-induced tyrosine kinase cascade to control thymic selection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 10620–10625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kozer N., Barua D., Henderson C., Nice E. C., Burgess A. W., Hlavacek W. S., and Clayton A. H. (2014) Recruitment of the adaptor protein Grb2 to EGFR tetramers. Biochemistry 53, 2594–2604 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carpenter A. C., and Bosselut R. (2010) Decision checkpoints in the thymus. Nat. Immunol 11, 666–673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kortum R. L., Rouquette-Jazdanian A. K., and Samelson L. E. (2013) Ras and extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling in thymocytes and T cells. Trends Immunol. 34, 259–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Braiman A., Barda-Saad M., Sommers C. L., and Samelson L. E. (2006) Recruitment and activation of PLCγ1 in T cells: a new insight into old domains. EMBO J. 25, 774–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lasserre R., Cuche C., Blecher-Gonen R., Libman E., Biquand E., Danckaert A., Yablonski D., Alcover A., and Di Bartolo V. (2011) Release of serine/threonine-phosphorylated adaptors from signaling microclusters down-regulates T cell activation. J. Cell Biol. 195, 839–853 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sylvain N. R., Nguyen K., and Bunnell S. C. (2011) Vav1-mediated scaffolding interactions stabilize SLP-76 microclusters and contribute to antigen-dependent T cell responses. Sci. Signal. 4, ra14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walker F., Rothacker J., Henderson C., Nice E. C., Catimel B., Zhang H. H., Scott A. M., Bailey M. F., Orchard S. G., Adams T. E., Liu Z., Garrett T. P., Clayton A. H., and Burgess A. W. (2012) Ligand binding induces a conformational change in epidermal growth factor receptor dimers. Growth factors 30, 394–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Songyang Z., Shoelson S. E., McGlade J., Olivier P., Pawson T., Bustelo X. R., Barbacid M., Sabe H., Hanafusa H., Yi T., et al. (1994) Specific motifs recognized by the SH2 domains of Csk, 3BP2, fps/fes, GRB-2, HCP, SHC, Syk, and Vav. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14, 2777–2785 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Williams B. L., Schreiber K. L., Zhang W., Wange R. L., Samelson L. E., Leibson P. J., and Abraham R. T. (1998) Genetic evidence for differential coupling of Syk family kinases to the T-cell receptor: reconstitution studies in a ZAP-70-deficient Jurkat T-cell line. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18, 1388–1399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nag A., Monine M., Perelson A. S., and Goldstein B. (2012) Modeling and simulation of aggregation of membrane protein LAT with molecular variability in the number of binding sites for cytosolic Grb2-SOS1-Grb2. PLoS ONE 7, e28758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nag A., Monine M. I., Faeder J. R., and Goldstein B. (2009) Aggregation of membrane proteins by cytosolic cross-linkers: theory and simulation of the LAT-Grb2-SOS1 system. Biophys. J. 96, 2604–2623 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu H. (2013) Higher-order assemblies in a new paradigm of signal transduction. Cell 153, 287–292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li P., Banjade S., Cheng H. C., Kim S., Chen B., Guo L., Llaguno M., Hollingsworth J. V., King D. S., Banani S. F., Russo P. S., Jiang Q. X., Nixon B. T., and Rosen M. K. (2012) Phase transitions in the assembly of multivalent signalling proteins. Nature 483, 336–340 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soares H., Lasserre R., and Alcover A. (2013) Orchestrating cytoskeleton and intracellular vesicle traffic to build functional immunological synapses. Immunol. Rev. 256, 118–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dustin M. L., and Groves J. T. (2012) Receptor signaling clusters in the immune synapse. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 41, 543–556 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Seminario M. C., and Bunnell S. C. (2008) Signal initiation in T-cell receptor microclusters. Immunol. Rev. 221, 90–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Blom H., and Brismar H. (2014) STED microscopy: increased resolution for medical research? J. Intern. Med. 276, 560–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson A. J., and Hess S. T. (2014) Localization microscopy: mapping cellular dynamics with single molecules. J. Microsc. 254, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lillemeier B. F., Mörtelmaier M. A., Forstner M. B., Huppa J. B., Groves J. T., and Davis M. M. (2010) TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nat. Immunol. 11, 90–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sherman E., Barr V., Manley S., Patterson G., Balagopalan L., Akpan I., Regan C. K., Merrill R. K., Sommers C. L., Lippincott-Schwartz J., and Samelson L. E. (2011) Functional nanoscale organization of signaling molecules downstream of the T cell antigen receptor. Immunity 35, 705–720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Clayton A. H., Orchard S. G., Nice E. C., Posner R. G., and Burgess A. W. (2008) Predominance of activated EGFR higher-order oligomers on the cell surface. Growth Factors 26, 316–324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Clayton A. H., Walker F., Orchard S. G., Henderson C., Fuchs D., Rothacker J., Nice E. C., and Burgess A. W. (2005) Ligand-induced dimer-tetramer transition during the activation of the cell surface epidermal growth factor receptor-A multidimensional microscopy analysis. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30392–30399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gagnon S. J., Borbulevych O. Y., Davis-Harrison R. L., Turner R. V., Damirjian M., Wojnarowicz A., Biddison W. E., and Baker B. M. (2006) T cell receptor recognition via cooperative conformational plasticity. J. Mol. Biol. 363, 228–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]