Abstract

Traditional Chinese Medicines (TCMs) have been the sole source of therapeutics in China for two millennia. In recent drug discovery efforts, purified components of TCM formulations have shown activity in many in vitro assays, raising concerns of promiscuity. Here, we investigated 14 bioactive small molecules isolated from TCMs for colloidal aggregation. At concentrations commonly used in cell-based or biochemical assay conditions, eight of these compounds formed particles detectable by dynamic light scattering and showed detergent-reversible inhibition against β-lactamase and malate dehydrogenase, two counter-screening enzymes. When tested against their literature-reported molecular targets, three of these eight compounds showed similar reversal of their inhibitory activity in the presence of detergent. For three of the most potent aggregators, contributions to promiscuity via oxidative cycling were investigated; addition of 1 mM DTT had no effect on their activity, which is inconsistent with an oxidative mechanism. TCMs are often active at micromolar concentrations; this study suggests that care must be taken to control for artifactual activity when seeking their primary targets. Implications for the formulation of these molecules are considered.

INTRODUCTION

An intriguing source of bioactive leads for drug discovery is the traditional formularies of preindustrial societies. Whereas some are untrustworthy, others have a long history of observation and optimization. Among these are traditional Chinese medicines (TCMs), which were an integral part of the medical system in China for over 2000 years.1,2 Their ongoing widespread use has spawned projects to understand the mechanism of action of TCMs and to improve their efficacy, including the purification of their active components, the determination of the molecular targets that they modulate, and the investigation of the role of the whole formulation in their activity.

The large selection of literature in which purified TCM components appear attests to the interest in their structure–activity relationships because natural products are often involved in drug discovery efforts.3 Molecules like curcumin, kaempferol, and silibinin have appeared in thousands of scholarly articles, many investigating the molecular targets through which these molecules act (Table 1). Over 10 000 targets have been identified,4 with the purified TCM components typically acting in the 1 to 200 μM concentration range (Table 1).5–37 Intriguingly, the targets reported for even a single compound are often unrelated. For instance, curcumin has been reported to inhibit calcium-dependent ATPase,5 HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases,6 human growth factor receptor 2 (HER2),38 protein kinase A (PKA),7 protein kinase C (PKC),8 lipoxygenase,39 P450 enzymes,40 tyrosinase,41 and thioredoxin reductase,42 among others.

Table 1.

TCM Citations, Targets, and Activities

| Compound | Structure | Representative molecular targets and EC50 values (μM) |

Pubmed citationsa |

|---|---|---|---|

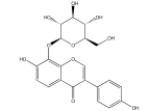

| Curcumin |

|

Ca2+-ATPase (~3), HER2, HIV-1 (100) and HIV-2 protease (250), cyclooxygenase (52), PkAand PkC |

6394 |

| Kaempferol |

|

ERR, OATP1B1, CDK (2.5 -51) and trypsin (60, 106) |

2960 |

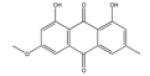

| Physcion |

|

PTP1B (20), MMP (26.8 – 45.3) | 244 |

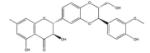

| Silibinin |

|

Hsp90 (250), GLUT4 (60) | 957 |

| Emodin |

|

MMP (12.8-20.1), AMPK (0.5), 11 β HSD1(4.2-7.2), trypsin (50), DYRK1A and CLK1 (4.2 – 6.1) |

1302 |

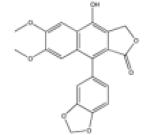

| Diphyllin |

|

Protective antigen’ DNA topoisomerase II |

40 |

| Bufalin |

|

P-glycoprotein (100), CYP3A4 (14.5) |

272 |

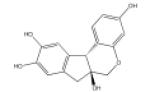

| Brazilin |

|

PKC | 66 |

| Puerarin |

|

IK1, ASICs (38.4) | 719 |

| Delphinidin |

|

Histone acetyltransferase, GL01 (1.9) |

550 |

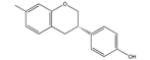

| Equol |

|

ERR (5.8), ERRD | 790 |

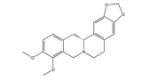

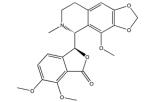

| Canadine |

|

Coagulation factor III, CDK2(>50) | 76 |

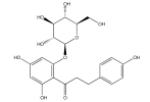

| Phlorizin |

|

SGLT1 and SGLT2 (0.02), hCNT (100-200) |

2341 |

| Noscapine |

|

OCT2 (2.6), tubulin, MATE1 (34.5) |

423 |

As of 2/26/14.

If identifying the molecular targets modulated by TCM molecules is crucial to understanding and optimizing their activity, so is the understanding of whether this activity is well-behaved and obeys classic stoichiometry. Four characteristics of TCM molecules motivated us to investigate their behavior: their resemblance to flavonoids, which can act artifactually via colloidal aggregation;43–45 their target promiscuity; the relatively high, micromolar concentration ranges in which they act (compared to drugs, whose median dissociation constant for their therapeutic targets is in the 20 nM range46); and the apparent importance of formulations involving multiple other components in their in vivo efficacy.

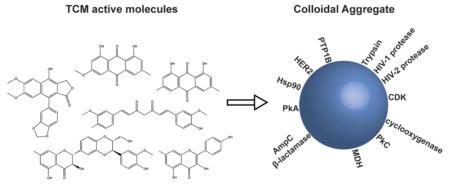

Here we investigate the formation of colloidal aggregates by TCM molecules. Colloidal aggregation of small molecules is the dominant mechanism of artifactual inhibition of soluble proteins45,47 and receptors.43 These small molecule aggregators form liquid-colloid-like particles that act by sequestering48,49 and partly denaturing50 their targets on their surfaces.51 These colloidal particles can be active both in biochemical buffers and in cell culture,52 affecting the rate and mechanism of penetration of drugs, dyes and reagents into cells.53 We selected 14 purified TCM molecules for this study on the basis of their structures, availability, and frequency of occurrence in the literature. Most of these compounds formed inhibitory colloidal aggregates, often in a concentration range overlapping that reported for on-target activity. The implications of these results for understanding the molecular mechanism of these TCM molecules and for their formulation in complex mixtures will be considered.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Investigating Aggregation of TCM Molecules by DLS and Enzyme Inhibition

Two criteria were used to investigate whether the TCM bioactive compounds formed colloidal aggregates: particle formation and detergent-reversible enzyme inhibition.48,54 Particle formation was detected and radii measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS). IC50 values were measured against model enzymes AmpC β-lactamase and malatedehydrogenase (MDH), which we have widely used as counter-screens for colloidal aggregate formation.55 Disruption of enzyme inhibition by nonionic detergents, such as Triton X-100, which little affects well-behaved substrates and inhibitors, is characteristic of a colloidal-based inhibition mechanism.

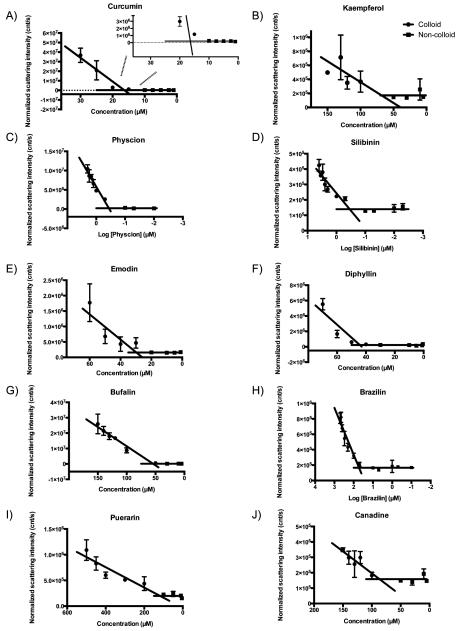

We first investigated the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) of each compound by DLS. This critical point is akin to critical micelle concentrations of detergents, though the resulting colloidal particles are typically much larger (often in the 200 nm radius range) and more polydisperse.56,57 Of the 14 TCMs, 10 had light scattering intensities and autocorrelation functions that supported particle formation, with radii ranging from 50 to >500 nm (Table 2 and Figure 1). Particles of silibinin and physcion began to be detected at submicromolar concentrations (Table 2), an order of magnitude lower than many of their literature activities (Table 1). The 17 μM CAC value of curcumin overlapped the concentration range of its reported activities, whereas those of kaempferol, emodin, canadine, and bufalin were found to be slightly above their reported activity range in the literature (Table 2). Conversely, the 135 μM CAC value of puerarin, although reproducible, puts it above the range of its bioactivities. For four TCM compounds—equol, phlorizin, noscapine, and delphinidin—no particles were observed by DLS up to their solubility limits, although enzyme inhibition suggests that delphinidin may well form inhibitory aggregates (as discussed below).

Table 2.

Bioactive Molecules in TCMs Form Particles and Inhibit Model Enzymes

| IC50 (μM) vs |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

β-lactamase |

MDH |

|||||

| compound | no detergenta | with detergentb | no detergent | with detergent | CAC (μM)c | radius (nm) |

| curcumin | 12 | >30 | 9 | >30 | 17 ± 0.44 | 465 ± 30 |

| kaempferol | 47 | >100 | 61 | >100 | 81 ± 26 | 61 ± 20 |

| physcion | 7 | >20 | 11 | >20 | 0.32 ± 0.025 | 320 ± 83 |

| silibinin | NDd | ND | 12 | >100 | 0.47 ± 0.15 | 53 ± 16 |

| emodin | 27 | >100 | 28 | >100 | 28 ± 2 | 231 ± 61 |

| diphyllin | 55 | >100 | 49 | >200 | 40 ± 4.0 | 269 ± 49 |

| bufalin | 93 | >200 | 101 | >200 | 51 ± 3 | 1317 ± 394 |

| brazilin | 302 | >500 | 1.6 | 84 | 57 ± 7 | 52 ± 10 |

| puerarin | ND | ND | 135 | 156 | 135 ± 40 | 78 ± 25 |

| delphinidin | 72 | 148 | 27 | >100 | ND | ND |

| equol | 127 | >500 | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| canadine | ND | ND | ND | ND | 95 ± 11 | 52 ± 14 |

| phlorizin | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| noscapine | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0.

50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0 + 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100.

Critical aggregation concentration determined by dynamic light scattering.

Not detected to precipitation limit.

Figure 1.

Critical colloid (●) and noncolloid (∎) aggregation curves for (A) curcumin, (B) kaempferol, (C) physcion, (D) silibinin, (E) emodin, (F) diphyllin, (G) bufalin, (H) brazilin, (I) puerarin, and (J) canadine.

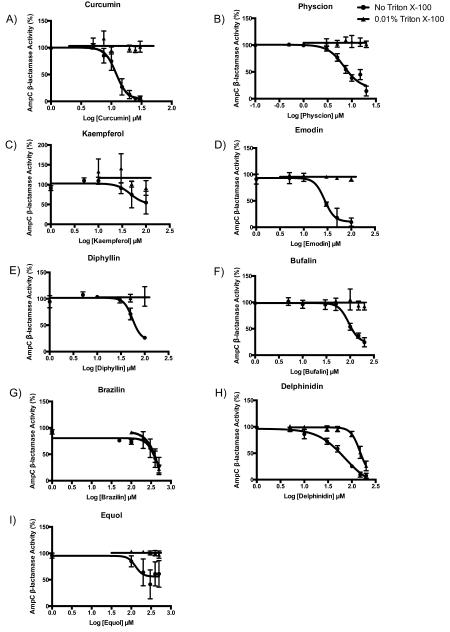

To investigate the relevance of colloidal formation on the activity against protein targets, all 14 compounds were tested for inhibition of AmpC β-lactamase and MDH. Of the 14, 11 inhibited one or both of these model enzymes (Table 2, Figures 2 and 3). A total of 10 of these showed detergent-reversible enzyme inhibition against at least one of the two enzymes, and most also formed particles as observed by DLS. The reversal of inhibition by addition of small amounts of nonionic detergent, below the critical micelle concentration (CMC) of that detergent, is a characteristic feature of a colloidal aggregator, one that is hard to reconcile with any other mechanism of inhibition.

Figure 2.

AmpC β-lactamase dose-response curves in the absence (●) and presence (▴) of detergent for (A) curcumin, (B) physcion, (C) kaempferol, (D) emodin, (E) diphyllin, (F) bufalin, (G) brazilin, and (H) delphinidin.

Figure 3.

MDH inhibition dose-response curves in the absence (●) and presence (▴) of detergent for (A) curcumin, (B) physcion, (C) kaempferol, (D) silibinin, (E) emodin, (F) diphyllin, (G) bufalin, (H) brazilin, (I) delphinin, and (J) puerarin.

We note that although canadine formed particles by DLS, it did not inhibit either counter-screening enzyme. Phlorizin and noscapine showed no inhibition against either enzyme, consistent with their lack of particle formation.

Although there was broad correspondence between colloid-derived IC50 values and critical aggregation concentrations (CACs), the two values sometimes differed. Molecules such as physcion and silibinin have CACs a log-order lower than their IC50 values, whereas curcumin’s IC50 was slightly below its DLS-measured CAC (Table 2). IC50 values being much higher than CACs is explained by the stoichiometric nature of aggregate-based inhibition and the low concentration of the colloidal particles. These particles are present in the midfemptomolar to picomolar range at their CACs58 and sequester enzymes tightly.59 If the proteins are present at high enough concentrations—which given the low concentration of colloids need not be very high—they will overwhelm the capacity of the colloids to adsorb them, and the effective inhibition will be slight until the colloids rise to such a concentration that they have enough surface to again stoichiometrically match the enzyme. This is why it is possible to diminish the inhibition of colloidal aggregates by increasing enzyme concentration.56 Conversely, because we rely on DLS to measure CAC and this can miss the scattering of low concentrations of particles, it is also possible to observe particles by enzyme inhibition before they can be observed physically.

If colloid aggregation explains the reported activity of TCMs against some targets, then it should be possible to demonstrate this on these targets. We therefore sought targets that were readily assayed for three of the most highly cited TCMs: emodin, kaempferol, and curcumin. Emodin and kaempferol had been found to inhibit trypsin in the 50 to 100 μM range, values we were able to reproduce in buffer lacking detergent and that were consistent with their CAC values in related buffer12,13,60 (Tables 2 and 3). Upon addition of 0.01% nonionic detergent Triton X-100, inhibition was essentially eliminated (Table 3, Figure 4A,B). Similarly, the addition of detergent to our HIV-2 protease inhibition assays also resulted in a significant reduction in inhibition by curcumin (Table 3, Figure 4C). The DLS data and enzymology against β-lactamase and MDH suggest that many of the TCMs in this study form colloidal aggregates at relevant concentrations, and these observations against trypsin and HIV-2 protease confirm a colloidal-based mechanism of action on the reported targets themselves.

Table 3.

Inhibition of TCM Targets Can Be Reversed by Nonionic Detergent

| IC50 vs trypsin (μM) |

IC50 vs HIV-2 protease (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | no detergenta |

with detergentb |

no detergentc |

with detergentd |

| emodin | 49 | >500 | ||

| kaempferol | 110 | >250 | ||

| curcumin | 19 | >100 | ||

50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0.

50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0 + 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100.

50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 200 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM TCEP.

50 mM sodium acetate, pH 5.5, 200 mM sodium chloride, 1 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM TCEP + 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100.

Figure 4.

Trypsin inhibition dose-response curves in the absence (black circles) and presence (red triangles) of detergent for (A) emodin and (B) kaempferol. HIV-2 protease inhibition dose response curve in the absence (black circles) and presence (red diamonds) of detergent for (C) curcumin.

Investigating the Role of Oxidative Cycling in Enzyme Inhibition

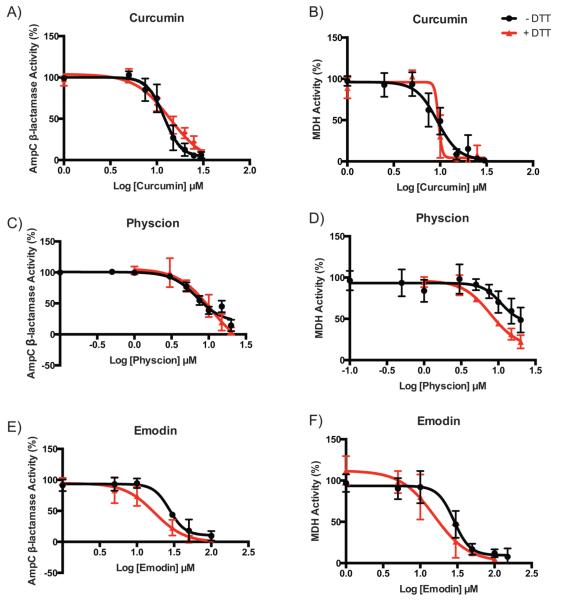

Promiscuous inhibition by (−)EGCG, a polyphenol found in some TCMs, has been attributed to the reactivity of its auto-oxidation products.61 Because 10 of our 14 compounds are also polyphenols, we were interested in exploring the contribution of oxidative cycling to their ability to inhibit the two model enzymes. We thus performed enzyme inhibition assays with curcumin, emodin, and physcion in the presence of a reducing agent to discriminate between colloidal and oxidative inhibition. Addition of 1 mM DTT did not significantly affect inhibition (Table 4 and Figure 5), suggesting that the observed activity is not influenced by auto-oxidation products. Thus, for these three polyphenols, their promiscuous activity is consistent with a dominant role of colloidal aggregation.

Table 4.

Enzyme Inhibition by Bioactive Molecules in TCMs in the Presence of 1 mM DTT

| IC50 vs AmpC β-lactamase (μM) |

IC50 vs MDH (μM) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| compound | no DTT | with DTT | no DTT | with DTT |

| curcumin | 12 | 14 | 9 | 10 |

| emodin | 27 | 17 | 28 | 18 |

| physcion | 7 | 11 | 11 | 8 |

Figure 5.

AmpC β-lactamase and MDH inhibition dose-response curves in the absence (black circles) and presence (red triangles) of DTT for (A and B) curcumin, (C and D) physcion, and (E and F) emodin.

Taken together, these results indicate that curcumin, kaempferol, physcion, silibinin, emodin, diphyllin, bufalin, and brazilin are strong aggregators that exhibit CAC and IC50 values in the 1 to 100 μM range. Puerarin, delphinidin, and equol, which either showed relatively high (poor) CAC values or were only able to satisfy one of the criteria, are likely weaker aggregators. Though we do not discount the role of oxidative cycling in the activity of polyphenols and TCM molecules, such a mechanism does not appear to contribute to the activity of the compounds in this study. For only two of the molecules tested, phlorizin and noscapine, was there no evidence of colloidal aggregation. The lack of enzyme inhibition and the high CAC value for canadine suggest that aggregation may also be irrelevant to its activity.

TCMs have been the focus of intense interest, many appearing in hundreds or thousands of scholarly studies as investigators seek the molecular targets underlying the efficacy of these preindustrial-era therapeutics. To understand and to optimize the activity of purified TCM molecules and to understand if they have reproducible and nonplacebo activities, determining their molecular targets seems crucial. A key observation from this study is that the purified components of TCMs can form colloidal aggregates that act nonspecifically on protein targets, clouding their true mechanism. Of the 14 TCM molecules investigated, 8 are strong aggregators whose IC50 values against counter-screen enzymes overlap with literature-reported activities on their putative molecular targets. Consistent with a colloidal mechanism, this inhibition could be reversed by the addition of a nonionic detergent, a treatment that leaves most specific, well-behaved ligand affinities unperturbed. For three of the TCMs, kaempferol, emodin, and curcumin, we were able to show that colloidal aggregation explained their inhibition on their putative literature targets–here trypsin and HIV-2 protease—because nonionic detergent completely disrupted inhibition (Tables 1, 2, and 3).

Naturally, not all TCMs tested here are aggregators. Molecules such as puerarin and equol may aggregate at ≥100 μM, but this behavior might only be relevant to those experiments conducted at unusually high concentrations. Correspondingly, for molecules like phlorizin and noscapine, no aggregation could be detected at accessible concentrations. Thus, not all TCM molecules can be tarred with an aggregation brush because some seem intrinsically clear of this behavior.62 Even for those that do aggregate, there are likely targets, conditions, and concentration ranges where this mechanism is not relevant. Finally, it merits re-emphasis that this study reflects only on the in vitro, target-based activity of TCM molecules, not their behavior in vivo.

What this study does suggest is that colloidal aggregation must be controlled for when seeking molecular targets for TCMs and related molecules. If it is perhaps disturbing that aggregation is so prevalent among TCM molecules, then it should also be comforting that controls for aggregation can be readily conducted. They include the addition of nonionic detergents to assays of soluble proteins44,54,57,63 and some membrane-bound receptors,43 colloid precipitation by centrifugation,48,64 increasing target concentration in the assay,56,65 and more biophysical techniques like DLS, NMR,66 and surface plasmon resonance.67 In addition to distinguishing among true and artifactual targets of TCM molecules, this study may help to illuminate the role of formulation in TCM activity, whose practitioners have long argued that it is only in the full mixture, with multiple other components, that TCMs are fully active.68,69 Although there are many explanations of the importance of formulation, it may be that the strong colloid-forming potential of many TCM molecules can affect their pharmacokinetics and biodistribution, as may be true, too, for some Western formulary drugs.70 Controlling for colloid formation may not only help with determining their target-based mechanism of action, but also with optimizing their in vivo activity, something supported by recent formulation studies of aggregating small molecules.71,72

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

AmpC β-lactamase was purified from Escherichia coli as previously described.73 Malate dehydrogenase (MDH) was purchased from VWR (M7032) and Sigma-Aldrich (CA97061-502). Trypsin from porcine pancreas (T0303) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. HIV-2 protease was kindly provided to us by Dr. Charles Craik (UCSF). CENTA (219574) was purchased from EMD Millipore. Chromogenic trypsin substrate Nα-benzoyl-dl-arginine 4-nitroanilide hydrochloride (BApNA) (B4875) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Anthranilyl-HIV protease substrate (H-2992) was purchased from BACHEM. Oxaloacetate (O4126), reduced β-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) (N4505), brazilin (PH010674), noscapine (363960, purity: 97%), delphinidin chloride (43725, purity: ≥ 95%), kaempferol (60010, purity: ≥ 97%), and curcumin (08511, purity: ≥ 98%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Canadine (C175175, purity: 96%) and bufalin (B689510, purity: 98%) were purchased from Toronto Research Chemicals. Equol (S2450, purity: 99%), silibinin (S2357, purity: 99%), puerarin (S2346, purity: 99%), physcion (S2395, purity: 99%), phlorizin (S2343, purity: 99%), and emodin (S2295, purity: 99%) were purchased from Selleck Chemicals. Diphyllin (N038-0217) was purchased from Molport. Triton X-100 (TB0198) was purchased from Bio Basic Canada.

Dynamic Light Scattering

Concentrated DMSO stocks of all 14 compounds were diluted with filtered 50 mM KPi, pH 7.0, with a final concentration of 1% DMSO. Measurements were made using a DynaPro Plate Reader II system (Wyatt Technology) with a 60 mW laser at ~830 nm in either 96- or 384-well plates; this particular instrument had been modified by Wyatt Technology to have a larger laser beam width that is appropriate for detecting large colloidal particles. Data were acquired and processed by the software Dynamics, version 1.7 (Wyatt Technology). The laser power was automatically adjusted by the Dynamics software; the detector angle was 158°. Each radius value reported represents three or more independent measurements at 25 °C at twice the compound’s CAC.

CAC Determination

Normalized scattering intensities (counts/sec, cnt/s) were plotted against decreasing concentrations of each compound. Data for colloidal and noncolloidal states were linearly regressed and the intersection point was determined to be the critical aggregation concentration. Concentrations are represented as the mean and the standard deviation of at least three independent replicates.

Enzyme Assays

All 14 compounds were tested for in hibition of AmpC β-lactamase and MDH. Emodin and kaempferol were tested for inhibition of trypsin. Stocks of the compounds were typically prepared at 100 times the working concentration in DMSO and subsequently diluted into 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer to yield a final reaction volume of 1 mL. Assays were performed at room temperature in 50 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.0, with or without 0.01% (v/v) Triton X-100, a concentration below the CMC (0.02%) of this nonionic detergent. Data acquisition was performed by an HP8453a spectrophotometer using kinetic mode in the software UV–vis ChemStation (Agilent Technologies), which also determined the first-order reaction rates. All reactions were performed in the presence of 1% DMSO to control for its effects on enzyme activity. Additional assays supplemented with 1 mM DTT were performed for curcumin, emodin, and physcion. Curcumin was tested for inhibition of HIV-2 protease. Stocks of curcumin were prepared in DMSO at 100 times the working concentration and subsequently diluted into 50 mM sodium acetate to yield a final reaction volume of 50 μL. These assays were performed at room temperature in 50 mM sodium acetate, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM TCEP, pH 5.5, with or without 0.01% Triton X-100. Fluorescence data acquisition was performed by a BioTek Synergy H4 microplate reader using the GEN5 software, which also determined the first-order reaction rates.

For AmpC β-lactamase assays, compound and 1 nM enzyme were incubated for 5 min, and the reaction was initiated with 200 μM of the chromogenic β-lactamase substrate CENTA. CENTA was prepared as a 4.6 mM stock in 50 mM potassium phosphate. Hydrolysis of CENTA was monitored at 405 nm. For MDH assays, compound and 2 nM enzyme were incubated for 5 min and the reaction was initiated with 200 μM oxaloacetate and 200 μM NADH, which were freshly prepared on the day of the experiment as 20 mM stocks in 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer. The rate of reaction was monitored spectrophotometri cally at 340 nm. For trypsin assays, compound and 1 nM enzyme were incubated for 5 min and the reaction was initiated with 60 μM BApNA. BApNA was prepared as a 200 mM stock in potassium phosphate. Cleavage of BApNA was monitored at 405 nm. For HIV-2 protease assays, curcumin was incubated with 1 μg mL−1 enzyme for 5 min, and the reaction was initiated with 0.5 mM anthranilyl HIV protease substrate. Fluorescence of the cleaved substrate was monitored with excitation and emission wavelengths of 280 and 435 nm, respectively. From these assays, an IC50 value of 19 μM was obtained for curcumin, which was an order of magnitude stronger than that previously reported.6 This difference in IC50 likely reflects the lower salt concentrations used in our assays (0.2 M vs 1 M) and the use of a FRET-based substrate.74,75

Activity was measured in triplicate for at least six different concentrations for each compound. Dose–response curves were plotted, and IC50 values were calculated by Graphpad Prism 6 (Graphpad, San Diego, CA), using a sigmoidal dose–response curve slope. analysis with variable slope.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grant GM71630. We thank M. Korczynska and M. O’Meara for reading this manuscript. We also thank C. Craik for providing us with the HIV-2 protease and C. Mahon, S. Clarke, and J. Gable for helping us with the HIV-2 protease inhibition assays.

Footnotes

Notes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Yu F, Takahashi T, Moriya J, Kawaura K, Yamakawa J, Kusaka K, Itoh T, Morimoto S, Yamaguchi N, Kanda T. Traditional Chinese medicine and Kampo: a review from the distant past for the future. J. Int. Med. Res. 2006;34:231–239. doi: 10.1177/147323000603400301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Cheng JT. Review: Drug therapy in Chinese traditional medicine. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000;40:445–450. doi: 10.1177/00912700022009198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Clardy J, Walsh C. Lessons from natural molecules. Nature. 2004;432:829–837. doi: 10.1038/nature03194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Xue R, Fang Z, Zhang M, Yi Z, Wen C, Shi T. TCMID: Traditional Chinese Medicine integrative database for herb molecular mechanism analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D1089–1095. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Logan-Smith MJ, Lockyer PJ, East JM, Lee AG. Curcumin, a molecule that inhibits the Ca2+-ATPase of sarcoplasmic reticulum but increases the rate of accumulation of Ca2+ J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:46905–46911. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M108778200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Sui Z, Salto R, Li J, Craik C, Ortiz de Montellano PR. Inhibition of the HIV-1 and HIV-2 proteases by curcumin and curcumin boron complexes. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1993;1:415–422. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(00)82152-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Fedorov O, Marsden B, Pogacic V, Rellos P, Muller S, Bullock AN, Schwaller J, Sundstrom M, Knapp S. A systematic interaction map of validated kinase inhibitors with Ser/Thr kinases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007;104:20523–20528. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708800104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Reddy S, Aggarwal BB. Curcumin is a non-competitive and selective inhibitor of phosphorylase kinase. FEBS Lett. 1994;341:19–22. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80232-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Wang J, Fang F, Huang Z, Wang Y, Wong C. Kaempferol is an estrogen-related receptor alpha and gamma inverse agonist. FEBS Lett. 2009;583:643–647. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Mandery K, Balk B, Bujok K, Schmidt I, Fromm MF, Glaeser H. Inhibition of hepatic uptake transporters by flavonoids. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2012;46:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lu H, Chang DJ, Baratte B, Meijer L, Schulze-Gahmen U. Crystal structure of a human cyclin-dependent kinase 6 complex with a flavonol inhibitor, fisetin. J. Med. Chem. 2005;48:737–743. doi: 10.1021/jm049353p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Maliar T, Jedinak A, Kadrabova J, Sturdik E. Structural aspects of flavonoids as trypsin inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2004;39:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Parellada J, Guinea M. Flavonoid inhibitors of trypsin and leucine aminopeptidase: a proposed mathematical model for IC50 estimation. J. Nat. Prod. 1995;58:823–829. doi: 10.1021/np50120a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Lee W, Yoon G, Hwang YR, Kim YK, Kim SN. Anti-obesity and hypolipidemic effects of Rheum undulatum in high-fat diet-fed C57BL/6 mice through protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibition. BMB Rep. 2012;45:141–146. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2012.45.3.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Wierzchacz C, Su E, Kolander J, Gebhardt R. Differential inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases-2, -9, and -13 activities by selected anthraquinones. Planta Med. 2009;75:327–329. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1112205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Zhao H, Brandt GE, Galam L, Matts RL, Blagg BS. Identification and initial SAR of silybin: an Hsp90 inhibitor. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2011;21:2659–2664. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.12.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhan T, Digel M, Kuch EM, Stremmel W, Fullekrug J. Silybin and dehydrosilybin decrease glucose uptake by inhibiting GLUT proteins. J. Cell. Biochem. 2011;112:849–859. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Song P, Kim JH, Ghim J, Yoon JH, Lee A, Kwon Y, Hyun H, Moon HY, Choi HS, Berggren PO, Suh PG, Ryu SH. Emodin regulates glucose utilization by activating AMP-activated protein kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:5732–5742. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.441477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Wang YJ, Huang SL, Feng Y, Ning MM, Leng Y. Emodin, an 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 inhibitor, regulates adipocyte function in vitro and exerts anti-diabetic effect in ob/ob mice. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2012;33:1195–1203. doi: 10.1038/aps.2012.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Grabher P, Durieu E, Kouloura E, Halabalaki M, Skaltsounis LA, Meijer L, Hamburger M, Potterat O. Library-based discovery of DYRK1A/CLK1 inhibitors from natural product extracts. Planta Med. 2012;78:951–956. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1298625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Zhu PJ, Hobson JP, Southall N, Qiu C, Thomas CJ, Lu J, Inglese J, Zheng W, Leppla SH, Bugge TH, Austin CP, Liu S. Quantitative high-throughput screening identifies inhibitors of anthrax-induced cell death. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2009;17:5139–5145. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2009.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Shi DK, Zhang W, Ding N, Li M, Li YX. Design, synthesis and biological evaluation of novel glycosylated diphyllin derivatives as topoisomerase II inhibitors. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2012;47:424–431. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gozalpour E, Wittgen HG, van den Heuvel JJ, Greupink R, Russel FG, Koenderink JB. Interaction of digitalis-like compounds with P-glycoprotein. Toxicol. Sci. 2013;131:502–511. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfs307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Li HY, Xu W, Zhang X, Zhang WD, Hu LW. Bufalin inhibits CYP3A4 activity in vitro and in vivo. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2009;30:646–652. doi: 10.1038/aps.2009.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Kim SG, Kim YM, Khil LY, Jeon SD, So DS, Moon CH, Moon CK. Brazilin inhibits activities of protein kinase C and insulin receptor serine kinase in rat liver. Arch. Pharm. Sci. Res. 1998;21:140–146. doi: 10.1007/BF02974018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Zhang H, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Yang X, Yu J, Shun S, Wu Y, Zeng Q, Wang T. Puerarin: a novel antagonist to inward rectifier potassium channel (IK1) Mol. Cell. Biochem. 2011;352:117–123. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0746-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Gu L, Yang Y, Sun Y, Zheng X. Puerarin inhibits acid-sensing ion channels and protects against neuron death induced by acidosis. Planta Med. 2010;76:583–588. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1240583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Seong AR, Yoo JY, Choi K, Lee MH, Lee YH, Lee J, Jun W, Kim S, Yoon HG. Delphinidin, a specific inhibitor of histone acetyltransferase, suppresses inflammatory signaling via prevention of NF-κB acetylation in fibroblast-like synoviocyte MH7A cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;410:581–586. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Takasawa R, Saeki K, Tao A, Yoshimori A, Uchiro H, Fujiwara M, Tanuma S. Delphinidin, a dietary anthocyanidin in berry fruits, inhibits human glyoxalase I. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2010;18:7029–7033. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2010.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Tilley AJ, Zanatta SD, Qin CX, Kim IK, Seok YM, Stewart A, Woodman OL, Williams SJ. 2-Morpholinoisoflav-3-enes as flexible intermediates in the synthesis of phenoxodiol, isophenoxodiol, equol and analogues: vasorelaxant properties, estrogen receptor binding and Rho/RhoA kinase pathway inhibition. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:2353–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Hirvonen J, Rajalin AM, Wohlfahrt G, Adlercreutz H, Wahala K, Aarnisalo P. Transcriptional activity of estrogen-related receptor γ (ERRγ) is stimulated by the phytoestrogen equol. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011;123:46–57. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Ge HX, Zhang J, Chen L, Kou JP, Yu BY. Chemical and microbial semi-synthesis of tetrahydroprotoberberines as inhibitors on tissue factor procoagulant activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Hegde VR, Borges S, Pu H, Patel M, Gullo VP, Wu B, Kirschmeier P, Williams MJ, Madison V, Fischmann T, Chan TM. Semi-synthetic aristolactams—inhibitors of CDK2 enzyme. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;20:1384–1387. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Chan HW, Ashan B, Jayasekera P, Collier A, Ghosh S. A new class of drug for the management of type 2 diabetes: sodium glucose co-transporter inhibitors: ‘Glucuretics’. Diabetes, Metab. Syndr. Obes.: Targets Ther. 2012;6:224–228. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2012.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Gupte A, Buolamwini JK. Synthesis and biological evaluation of phloridzin analogs as human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 (hCNT3) inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009;19:917–921. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.11.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Wittwer MB, Zur AA, Khuri N, Kido Y, Kosaka A, Zhang X, Morrissey KM, Sali A, Huang Y, Giacomini KM. Discovery of potent, selective multidrug and toxin extrusion transporter 1 (MATE1, SLC47A1) inhibitors through prescription drug profiling and computational modeling. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:781–795. doi: 10.1021/jm301302s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Chandra R, Madan J, Singh P, Chandra A, Kumar P, Tomar V, Dass SK. Implications of nanoscale based drug delivery systems in delivery and targeting tubulin binding agent, noscapine in cancer cells. Curr. Drug. Metab. 2012;13:1476–1483. doi: 10.2174/138920012803762756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Jung Y, Xu W, Kim H, Ha N, Neckers L. Curcumin-induced degradation of ErbB2: A role for the E3 ubiquitin ligase CHIP and the Michael reaction acceptor activity of curcumin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1773:383–390. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Bezakova L, Kostalova D, Oblozinsky M, Hoffman P, Pekarova M, Kollarova R, Holkova I, Mosovska S, Sturdik E. Inhibition of 12/15 lipoxygenase by curcumin and an extract from Curcuma longa L. Ceska. Slov. Farm. 2014;63:26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Oetari S, Sudibyo M, Commandeur JN, Samhoedi R, Vermeulen NP. Effects of curcumin on cytochrome P450 and glutathione S-transferase activities in rat liver. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1996;51:39–45. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(95)02113-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Patil S, Srinivas S, Jadhav J. Evaluation of crocin and curcumin affinity on mushroom tyrosinase using surface plasmon resonance. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014;65:163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2014.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Munigunti R, Gathiaka S, Acevedo O, Sahu R, Tekwani B, Calderon AI. Determination of antiplasmodial activity and binding affinity of curcumin and demethoxycurcumin towards PfTrxR. Nat. Prod. Res. 2014;28:359–364. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2013.866112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Sassano MF, Doak AK, Roth BL, Shoichet BK. Colloidal aggregation causes inhibition of G protein-coupled receptors. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:2406–2414. doi: 10.1021/jm301749y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Pohjala L, Tammela P. Aggregating behavior of phenolic compounds—a source of false bioassay results? Molecules. 2012;17:10774–10790. doi: 10.3390/molecules170910774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).McGovern SL, Shoichet BK. Kinase inhibitors: not just for kinases anymore. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:1478–1483. doi: 10.1021/jm020427b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat. Rev. Drug Discovery. 2006;5:993–996. doi: 10.1038/nrd2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Thorne N, Auld DS, Inglese J. Apparent activity in high-throughput screening: origins of compound-dependent assay interference. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2010;14:315–324. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).McGovern SL, Helfand BT, Feng B, Shoichet BK. A specific mechanism of nonspecific inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:4265–4272. doi: 10.1021/jm030266r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Coan KED, Shoichet BK. Stoichiometry and physical chemistry of promiscuous aggregate-based inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9606–9612. doi: 10.1021/ja802977h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Coan KED, Maltby DA, Burlingame AL, Shoichet BK. Promiscuous Aggregate-Based Inhibitors Promote Enzyme Unfolding. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2067–2075. doi: 10.1021/jm801605r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Ilevbare GA, Liu H, Edgar KJ, Taylor LS. Impact of polymers on crystal growth rate of structurally diverse compounds from aqueous solution. Mol. Pharmaceutics. 2013;10:2381–2393. doi: 10.1021/mp400029v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Owen SC, Doak AK, Wassam P, Shoichet MS, Shoichet BK. Colloidal Aggregation Affects the Efficacy of Anticancer Drugs in Cell Culture. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:1429–1435. doi: 10.1021/cb300189b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Horobin RW, Rashid-Doubell F, Pediani JD, Milligan G. Predicting small molecule fluorescent probe localization in living cells using QSAR modeling. 1. Overview and models for probes of structure, properties and function in single cells. Biotechnol. Histochem. 2013;88:440–460. doi: 10.3109/10520295.2013.780634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Ryan AJ, Gray NM, Lowe PN, Chung CW. Effect of detergent on “promiscuous” inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2003;46:3448–3451. doi: 10.1021/jm0340896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Babaoglu K, Simeonov A, Irwin JJ, Nelson ME, Feng B, Thomas CJ, Cancian L, Costi MP, Maltby DA, Jadhav A, Inglese J, Austin CP, Shoichet BK. Comprehensive mechanistic analysis of hits from high-throughput and docking screens against β-lactamase. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:2502–2511. doi: 10.1021/jm701500e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).McGovern SL, Caselli E, Grigorieff N, Shoichet BK. A common mechanism underlying promiscuous inhibitors from virtual and high-throughput screening. J. Med. Chem. 2002;45:1712–1722. doi: 10.1021/jm010533y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Feng BY, Shoichet BK. A detergent-based assay for the detection of promiscuous inhibitors. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:550–553. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Coan KE, Shoichet BK. Stoichiometry and physical chemistry of promiscuous aggregate-based inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9606–9612. doi: 10.1021/ja802977h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Coan KED, Shoichet BK. Stability and equilibria of promiscuous aggregates in high protein milieus. Mol. BioSyst. 2007;3:208–213. doi: 10.1039/b616314a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Jedinak A, Maliar T, Grancai D, Nagy M. Inhibition activities of natural products on serine proteases. Phytother. Res. 2006;20:214–217. doi: 10.1002/ptr.1836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Zhu J, Van de Ven WJ, Verbiest T, Koeckelberghs G, Chen C, Cui Y, Vermorken AJ. Polyphenols can inhibit furin in vitro as a result of the reactivity of their auto-oxidation products to proteins. Curr. Med. Chem. 2013;20:840–850. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Sorensen PM, Iacob RE, Fritzsche M, Engen JR, Brieher WM, Charras G, Eggert US. The natural product cucurbitacin E inhibits depolymerization of actin filaments. ACS Chem. Biol. 2012;7:1502–1508. doi: 10.1021/cb300254s. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. A high-throughput screen for aggregation-based inhibition in a large compound library. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2385–2390. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Shoichet BK. Interpreting steep dose-response curves in early inhibitor discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:7274–7277. doi: 10.1021/jm061103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Lea WA, Simeonov A. Fluorescence polarization assays in small molecule screening. Expert Opin. Drug Discovery. 2011;6:17–32. doi: 10.1517/17460441.2011.537322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (66).LaPlante SR, Aubry N, Bolger G, Bonneau P, Carson R, Coulombe R, Sturino C, Beaulieu PL. Monitoring drug self-aggregation and potential for promiscuity in off-target in vitro pharmacology screens by a practical NMR strategy. J. Med. Chem. 2013;56:7073–7083. doi: 10.1021/jm4008714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (67).Giannetti AM, Koch BD, Browner MF. Surface plasmon resonance based assay for the detection and characterization of promiscuous inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:574–580. doi: 10.1021/jm700952v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (68).Chan E, Tan M, Xin JN, Sudarsanam S, Johnson DE. Interactions between traditional Chinese medicines and Western therapeutics. Curr. Opin. Drug Discovery Dev. 2010;13:50–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Zhu YP, Woerdenbag HJ. Traditional Chinese herbal medicine. Pharm. World Sci. 1995;17:103–112. doi: 10.1007/BF01872386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Doak AK, Wille H, Prusiner SB, Shoichet BK. Colloid formation by drugs in simulated intestinal fluid. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:4259–4265. doi: 10.1021/jm100254w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Kumar A, Ahuja A, Ali J, Baboota S. Curcumin-loaded lipid nanocarrier for improving bioavailability, stability and cytotoxicity against malignant glioma cells. Drug Delivery. 2014:1–16. doi: 10.3109/10717544.2014.909906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Lv L, Shen Y, Liu J, Wang F, Li M, Li M, Guo A, Wang Y, Zhou D, Guo S. Enhancing curcumin anticancer efficacy through di-block copolymer micelle encapsulation. J. Biomed. Nanotechnol. 2014;10:179–193. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Weston GS, Blazquez J, Baquero F, Shoichet BK. Structure-based enhancement of boronic acid-based inhibitors of AmpC β-lactamase. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4577–4586. doi: 10.1021/jm980343w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Babe LM, Rose J, Craik CS. Synthetic “interface” peptides alter dimeric assembly of the HIV 1 and 2 proteases. Protein Sci. 1992;1:1244–1253. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560011003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Pichuantes S, Babe LM, Barr PJ, DeCamp DL, Craik CS. Recombinant HIV2 protease processes HIV1 Pr53gag and analogous junction peptides in vitro. J. Biol. Chem. 1990;265:13890–13898. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]