Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is the number one cause of hospital-acquired infections. Understanding host pathogen interactions is paramount to the development of more effective treatment and prevention strategies. Therefore, whole exome sequence and chip-based genotype data were used to conduct rare variant and genome-wide association analyses in a Mexican-American cohort from Starr County, Texas to identify genes and variants associated with S. aureus nasal carriage. Unlike most studies of S. aureus that are based on hospitalized populations, this study used a representative community sample. Two nasal swabs were collected from participants (n = 858) 11–17 days apart between October 2009 and December 2013, screened for the presence of S. aureus, and then classified as either persistent, intermittent, or non-carriers. The chip-based and exome sequence-based single variant association analyses identified 1 genome-wide significant region (KAT2B) for intermittent and 11 regions suggestively associated with persistent or intermittent S. aureus carriage. We also report top findings from gene-based burden analyses of rare functional variation. Notably, we observed marked differences between signals associated with persistent and intermittent carriage. In single variant analyses of persistent carriage, 7 of 9 genes in suggestively associated regions and all 5 top gene-based findings are associated with cell growth or tight junction integrity or are structural constituents of the cytoskeleton, suggesting that variation in genes associated with persistent carriage impact cellular integrity and morphology.

Introduction

Infectious diseases result from complex interactions between the microorganism, the host, and the environment. Host genetic factors play a major role in determining differential susceptibility to major infectious diseases of humans, including malaria [1], HIV/AIDS [2], tuberculosis [3], hepatitis B [4], Norovirus diarrhea [5], prion disease [6], Cholera [7], and Helicobacter pylori infections [8]. The first evidence that genetic factors could impact infectious disease outcomes was derived from epidemiological studies that identified differences between human populations exposed to the same infectious organism [9]. This is equally true for S. aureus [10–12], but this pathogen represents a special case because it is an opportunistic pathogen that can colonize humans without causing overt disease [13]. It is therefore an ideal system for examining host pathogen interactions.

Even though humans are exposed to S. aureus at birth, not all are equally susceptible to colonization [9]. Many body sites can be colonized by S. aureus, but nasal decolonization has been shown to be effective in reducing colonization at other body sites, suggesting that the anterior nares is one of the primary S. aureus reservoirs [14, 15]. Human carriage has been classified as either persistent, intermittent, or non-carriage with rates of carriage ranging from 10–35%, 20–75%, and 5–70%, respectively, depending on race, age, gender, and whether the population examined was hospital- or community-based [9, 16–18]. Carriage is not representative of infection, per se. Rather, carriage impacts the risk of acquiring infection, disease presentation, and disease severity [13]. Furthermore, the genotype of the colonizing S. aureus strain, the nature of the immune response elicited following exposure, and underlying host genetic factors may all play a role in susceptibility to colonization and/or infection [9, 19–24]. Like other complex conditions, susceptibility to infectious agents does not typically follow a simple Mendelian pattern of inheritance, largely due to the fact that human immune responses are controlled by complex genetic mechanisms and modifying environmental influences [25, 26].

Candidate gene studies have uncovered associations between specific genes and carriage status [20–23, 27–29]. For example, IL4 and C-reactive protein have been shown to be associated with carriage in the Rotterdam Study [20, 22]. In the same study, a 68% reduction in risk of persistent carriage was observed related to the glucocorticoid receptor gene [30] (S1 Table). Polymorphisms in genes encoding different defensins and MBL (manose binding lectin) have also been associated with S. aureus persistent carriage [20, 31, 32] (S1 Table). The toll-like receptors have also been associated with increased risk of streptococci and enterococci skin and soft tissue infections [21, 33] suggesting that there may be some commonalities in the genetics of susceptibility to infection with different pathogens. No community-based genome-wide association or whole exome sequencing studies have previously been performed in the context of S. aureus carriage, but recently, 2 hospital-based genome-wide association studies of S. aureus infections were conducted [34, 35]. That these studies failed to identify targets with genome wide significance is not necessarily surprising since hospital environments themselves are a significant risk factor for acquiring S. aureus infections and these effects may overwhelm modest genetic influences on risk [36].

The present study was designed to identify genes/markers associated with persistent and intermittent carriage of S. aureus in a community-based sample of 858 Mexican-Americans from Starr County, Texas. Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) data from the Affymetrix Genome-Wide SNPArray 6.0 assay imputed out to the complete SNP set in the 1000 Genomes Project [37] and whole exome sequence data were used to conduct single variant and gene-based burden tests. The single variant analyses identified the KAT2B (lysine acetyltransferase 2B) region as significantly associated with intermittent S. aureus carriage. All 5 top genes identified in the gene-based burden test and at least 1 gene in each region suggestively associated with persistent carriage in the single variant analysis are associated in some fashion with maintenance of cellular integrity, the cytoskeleton, or the cell cycle. On the other hand, genes associated with intermittent carriage were largely associated with immune function, adipogeneisis, or inflammation. These analyses identified little evidence of overlap between genes or regions corresponding to different carriage phenotypes suggesting that each carrier state may be distinct.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

This study and the consenting procedures were approved by the University of Texas Health Science Center Institutional Review Board (HSC-SPH-06-0225). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before they were enrolled in the study.

Microbiologic testing

Specimens were collected from the nares using dry, unmoistened sterile BBL™ CultureSwabs™ Liquid Stuart swabs. Swabs were inserted into the patient’s nostril approximately 1 inch from the edge from the anterior nares placing the swab in proximity with the inferior and middle concha and rolled several times. Bar-coded specimen tubes were stored and shipped at 4°C to the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston School of Public Health for processing.

To identify and characterize S. aureus from specimens containing mixed flora, nasal swabs were inoculated on manitol salt agar (MSA) plates (Remel Inc., Lenexa, KS) as described [38]. Following inoculation of primary plates, swabs were broken off into tryptic soy broth for enrichment (TSB) (Remel Inc.). The enrichment broths were vortexed for 10 seconds to ensure that any bacteria still attached to the swab were released into the media and the samples subsequently incubated at 37°C for 48 hours and re-plated on secondary MSA plates. Gram staining of respective colonies that turned MSA plates yellow were used to ensure that selected colonies possessed S. aureus morphology. Presumptive S. aureus colonies were streaked on blood agar (BA) (Quad Five, Ryegate, MT) and TSB agar and incubated at 37°C for 24 h.

Following incubations on BA and TSB agar from the primary and secondary MSA plates, colonies were subjected to catalase (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) and coagulase testing (BactiStaph® Latex 450, Remel Inc.). Positive tests were considered diagnostic for S. aureus. The identification of S. aureus was also confirmed genetically by PCR amplification and sequencing of a fragment of the spa gene for 1598/1662 (96%) of the isolates as done previously [38]. The second MSA plates streaked from the overnight liquid broth cultures were examined for additional growth, and colonies with S. aureus morphology were isolated and tested as above. Once isolates were defined as S. aureus, their respective susceptibilities to methicillin were determined using the E-test® (AB Biodisk, Biomerieux, I’Etoile, France). Methicillin resistance was defined by growth at antibiotic concentrations ≥4 μg/ml. All confirmed S. aureus isolates were stored at -80°C [38].

Definition of the S. aureus carriage phenotypes

Carriage status was determined for individuals from whom nasal swabs were collected at two time points, 2 weeks apart (14±3 days) as described previously [39]. Carriers were defined by S. aureus positive cultures at either visit, and intermittent carriers were S. aureus positive at either the first or second visit but not both. Non carriers were negative for S. aureus at both visits [39].

Genome-wide association studies and generation of whole genome imputation data

Subjects (n = 858) were eligible for this study because of prior participation in genome-wide association studies for diabetes [40]. Genotyping was performed at the Center for Inherited Disease Research using the Affymetrix Genome-wide SNPArray 6.0 assay with sample- and SNP-level genotyping quality control performed as described in Below et al. [40]. Imputations were carried out in the full Starr County sample, cleaned of ethnic outliers and including 1,616 unrelated (pairwise identity by descent ≤ 0.3) [41] individuals of which 858 met inclusion criteria in the present study. A set of autosomal scaffold SNPs were selected to drive imputation by excluding those with: 1) minor allele frequency <1%, 2) Hardy-Weinberg p-values < 10−4 in the full sample 3) missingness >10% in the full sample and 4) all ambiguous strand (AT/CG) SNPs. Individual-level missingness is <5% in all samples. 603,042 scaffold SNPs were carried forward into a two-step imputation strategy: i) pre-phasing using the program SHAPEIT [42] and ii) Imputation from the reference panel into the estimated haplotypes with IMPUTE v2 [43–45]. Imputations were done in conjunction with the T2D-GENES consortium as part of a larger set of some 13,000 multiethnic samples. SNPs with imputation quality ≥ 0.8 and minor allele frequency > 0.05 were carried forward for single variant analyses. Population stratification was evaluated using EIGENSOFT on a subset of directly genotyped SNPs pruned for local and long distance linkage disequilibrium as described in Patterson et al. [46].

Analyses were conducted by comparing persistent S. aureus carriers to noncarriers or intermittent carriers to noncarriers. Persistent carriers were defined as unrelated [41] individuals passing genotyping quality control and testing positive for colonization of S. aureus at both of two time points, 11 to 17 days apart (n = 141). Genes located within 50 kilobases of signals comprised of at least 4 SNPs and study-based minor allele frequency > 0.05 with a p value <10−5 were considered suggestively significant. For each region showing association, we identified a sentinel marker, defined as the most significant SNP meeting all quality control thresholds (locus zoom plots, Figs A-L, in S1 File).

Associations of the imputed genetic markers with S. aureus carrier status were tested with the program SNPTEST v2 [44] using frequentist association tests, based on an additive model. To control for genotype uncertainty, we used the missing data likelihood score test (the score method). All association analyses corrected for ancestry using the first and second principal components from EIGENSOFT as covariates, and all analyses were run once including diabetes status as a covariate and once excluding diabetes status in the model.

Generation and analysis of whole exome single variants

Whole exome sequence data were available for a subset of 792 participants (131 persistent carriers, 88 intermittent carriers, and 573 non-carriers, as defined above). These were part of a larger group sequenced as part of the T2D-GENES Consortium at the Broad Institute using Agilent Truseq capture reagents on Illumina HiSeq2000 instruments.

Association tests of the 1,011 common (minor allele frequency > 0.05) single variants present in the exome sequence data were performed using logistic regression in the program PLINK v2 [47]. As above, association analyses were corrected for ancestry using the first and second principal components, and all analyses were run including and excluding diabetes status as a covariate in the model. These results were combined with the imputed data results in common Manhattan plots (Figs 1 and 2 and Figs M-N in S1 File).

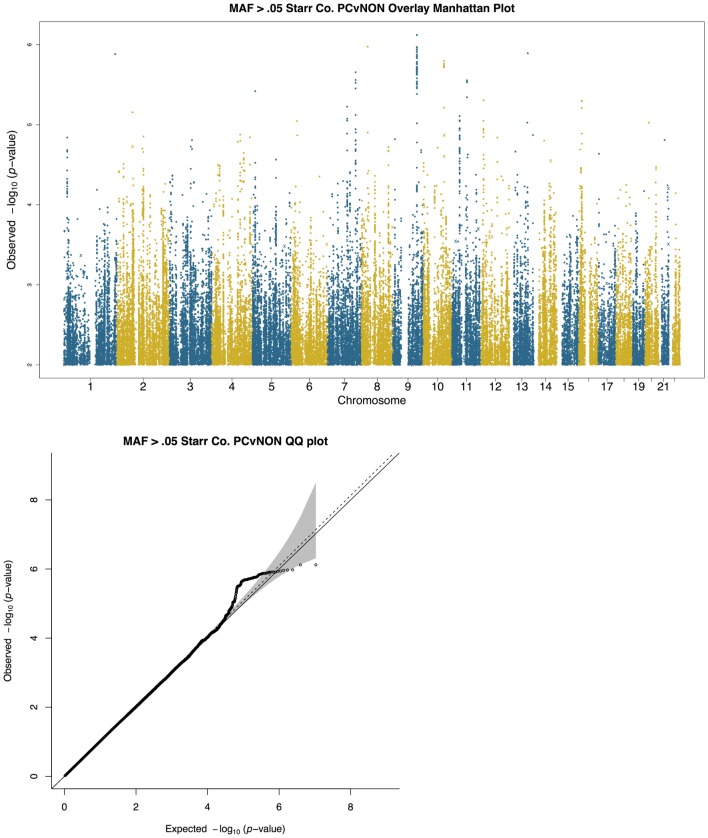

Fig 1. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of single variant logistic regression of persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier, including PC1 and PC2 as covariates.

The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represents a single polymorphic variant with minor allele frequency greater than 0.05. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for the same variants shown in (a). Grey shading indicates the 95% confidence interval, the solid line indicates the expected null distribution, and the dotted line indicates the slope after lambda correction for genomic control. The 1,011 common variants identified by whole exome sequencing are shown as x’s in the Manhattan plots.

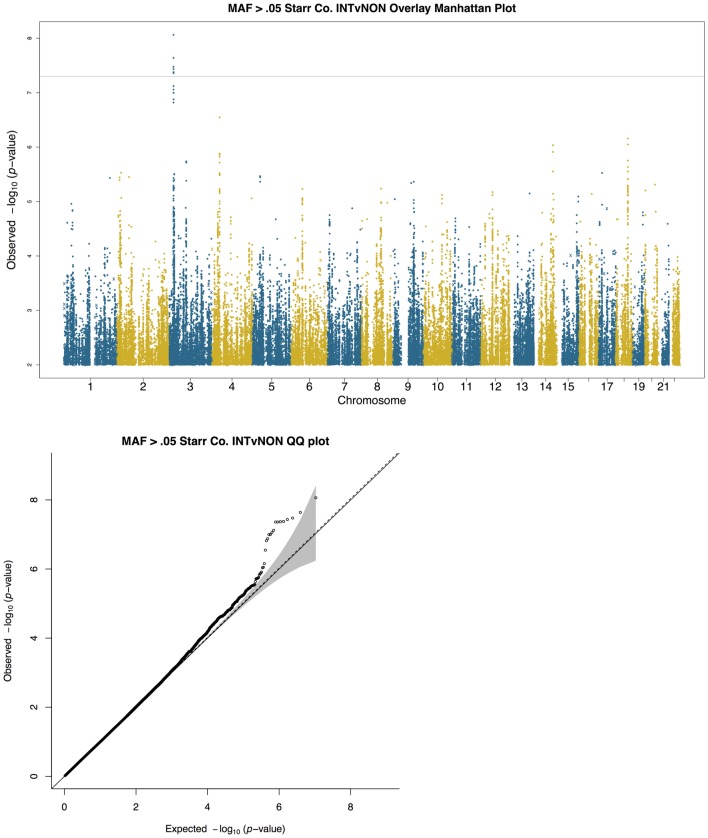

Fig 2. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of single variant logistic regression of intermittent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier, including PC1 and PC2 as covariates.

The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represents a single polymorphic variant with minor allele frequency greater than 0.05. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for the same variants shown in (a). Grey shading indicates the 95% confidence interval, the solid line indicates the expected null distribution, and the dotted line indicates the slope after lambda correction for genomic control. The 1,011 common variants identified by whole exome sequencing are shown as x’s in the Manhattan plots.

Gene-based analysis of whole exome sequence data

We used the Variant Annotation Analysis and Search Tool (VAAST) to identify genes associated with increased risk of S. aureus colonization [48, 49]. For quality-control purposes, we removed sites with missingness >10% in the full sample. We also used the rate option to set the maximum expected disease allele frequency to 0.05, as we expect to be powered to detect effects of common variants in single variant tests. The top two principle components from EIGENSOFT were used as covariates in all VAAST analyses, and analyses were performed with and without diabetes status as a covariate, as above. Statistical significance was assessed using a covariate-adjusted randomization test as previously described [50, 51]; p-value confidence intervals were calculated using a Poisson approximation based on the number of successes in the randomization test. Genome-wide significance thresholds for the gene-based tests were calculated from the number of genes tested (0.05/18665 = 2.68×10−6).

Results

Population demographics and S. aureus carriage determination

Carriage status was established by collecting and analyzing swabs for the presence of S. aureus on 2 occasions from a single nostril 11–17 days apart on 858 Mexican Americans from Starr County, TX, USA [39]. A summary of demographic information for these individuals, who were eligible due to prior participation in a genome-wide association study for type 2 diabetes, are presented in Table 1 [40]. Participants testing positive for S. aureus on 2 separate occasions were defined as persistent carriers (n = 141), participants testing positive once were defined as intermittent carriers (n = 97), and participants testing negative on both occasions were defined as non-carriers (n = 620) as previously described [38, 39].

Table 1. Demographic information for study participants by S. aureus carriage phenotype.

| Persistent Carrier | Intermittent Carrier | Non Carrier | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 141 (131) A | 97 (88) | 620 (573) | 858 (792) |

| % Female | 70.9 | 76.3 | 69.2 | 70.3 |

| % Diabetes | 52.5 | 62.9 | 48.7 | 50.9 |

| Mean BMI | 32.7 ±9.5 | 33.5 ±11.7 | 32.4 ±10.5 | 32.4 ±10.5 |

| Mean Age | 53.7 ±12.8 | 56.5 ±14.8 | 54.2 ±13.2 | 54.4 ±13.3 |

| Mean hbA1C | 6.8 ±2.4 | 7.2 ±2.7 | 6.6 ±2.3 | 6.7 ±2.4 |

ANumber of individuals with available exome data.

Single variant association tests

Single variant association tests of persistent S. aureus carriage identified 5 loci as suggestively significant (p value ≤ 10−5, as defined in the Methods) are summarized in Fig 1 and Table 2, namely MKLN1 (muskelin 1), SORBS1 (sorbin and SH3 domain containing 1), SLC1A2 (solute carrier family 1) SORBS1, a region intergenic between EPB41L4B (erythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 like 4B) and PTPN3 (cytoskeletal-associated protein tyrosine phosphatase), and a region downstream of FGF3 (fibroblast growth factor 3). MKLN1 encodes an intracellular mediator of cell morphology and cytoskeletal responses [52, 53]. SORBS1 is involved in insulin signaling and SLC1A2 is a member of the solute transporter family. EPB41L4B and PTPN3 are involved in membrane-cytoskeletal interactions while FGF3 is a member of the fibroblast growth factor family of genes. MKLN1 has been previously associated with childhood asthma [54], SORBS1 with suicide risk (46) and childhood obesity in Hispanics [55], SLC1A2 with fatty acid levels [56], essential tremor [57–59], and other traits [58, 59], EPB41L4B with wound healing [60], PTPN3 with cancer [61], and FGF3 with breast cancer [62] and deafness [63, 64]. Whole exome sequencing identified 1,011 common variants (minor allele frequency > 0.05). These are shown as x’s in the Manhattan plots. In no case did any of these variants reach a suggestive level indicating that it is unlikely that there are common protein-coding variants of substantial effect. LocusZoom [65] plots for each top locus highlight LD (linkage disequilibrium) patterns among the top SNPs and show multiple SNPs in LD blocks being associated (Figs A-E in S1 File).

Table 2. SNPs reaching suggestive significance in single variant logistic regression for persistent S. aureus carrier vs. non-carrier (top) and intermittent S. aureus carrier vs. non-carrier (bottom), including PC1 and PC2 as covariates.

| Persistent Carrier (PC) vs. Non Carrier Eigenscore 1,2 | Intermittent Carrier (INT) vs. Non Carrier Eigenscore 1,2 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SNP | Chr | Position | Risk allele | Non-risk allele | OR (95% CI) [p value] | OR (95% CI) [p value] | IMPUTE2 info score | Freq (all) | Freq (PC) | Freq (INT) | Freq (controls) | Genes within 50 kb of locus | Location of sentinel SNP |

| rs118047622 | 7 | 130819082 | C | G | 2.57 (1.74–3.80) [2.22E-06] | 1.72 (1.08–2.75) [2.25E-02] | 0.89 | 0.16 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.13 | LINC-PINT, MKLN1 | Intronic MKLN1 A |

| rs138799235 | 9 | 112129775 | C | T | 3.00 (1.94–4.63) [7.57E-07] | 1.04 (0.60–1.79) [8.91E-01] | 0.98 | 0.11 | 0.19 | 0.09 | 0.09 | EPB41L4B B , PTPN3 C | Intergenic EPB41L4B and PTPN3 |

| rs4918947 | 10 | 97293912 | A | G | 3.91 (2.24–6.83) [1.61E-06] | 0.69 (0.32–1.48) [3.37E-01] | 0.99 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.03 | 0.05 | SORBS1 D , ALDH18A1 E | Intronic SORBS1 |

| rs2421770 | 11 | 35320880 | C | G | 1.83 (1.40–2.38) [7.81E-06] | 1.25 (0.92–1.72) [1.57E-01] | 0.98 | 0.65 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.62 | SLC1A2 F | Intronic SLC1A2 |

| rs734102 | 11 | 69624482 | C | T | 3.68 (2.13–6.35) [2.79E-06] | 1.51 (0.83–2.75) [1.80E-01] | 0.99 | 0.94 | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.92 | FGF3 G , FGF4 G | Downstream FGF3 |

| rs61440199 | 3 | 20111546 | A | G | 2.63 (1.36–5.11) [4.20E-03] | 8.68 (4.16–18.13) [8.68E-09] | 0.99 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.12 | 0.03 | KAT2B H , SGOL1 I , PP2D1 J , SGOL1-AS1 K , MIR3135A L | Intronic KAT2B |

| rs7611684 | 3 | 23482812 | A | G | 1.31 (0.84–2.06) [2.32E-01] | 3.26 (1.98–5.35) [3.12E-06] | 0.96 | 0.11 | 0.12 | 0.21 | 0.10 | UBE2E2 M | Intronic UBE2E2 |

| rs11127662 | 3 | 79771987 | G | C | 1.27 (0.73–2.20) [3.99E-01] | 4.32 (2.37–7.87) [1.84E-06] | 0.99 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.15 | 0.06 | ROBO1 N | Intronic ROBO1 |

| rs16993852 | 4 | 37737989 | T | C | 3.48 (1.85–6.52) [1.03E-04] | 6.93 (3.31–14.52) [2.84E-07] | 0.98 | 0.06 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.04 | RELL1 O | Intergenic RELL1 and PGM2 P |

| rs222458 | 6 | 52890625 | A | G | 1.02 (0.53–1.94) [9.53E-01] | 4.77 (2.39–9.49) [8.71E-06] | 1.00 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.11 | 0.04 | GSTA4 Q , RN7SK R , ICK S , RN7SL244P T , FBXO9 U | Intronic ICK |

| rs1682522 | 14 | 87641837 | T | A | 1.05 (0.70–1.59) [7.99E-01] | 3.16 (1.99–4.99) [9.21E-07] | 0.91 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.25 | 0.12 | LOC283585 V , GALC W | Intergenic LOC283585 and GALC |

| rs8088420 | 18 | 56511908 | C | T | 1.17 (0.85–1.60) [3.45E-01] | 2.48 (1.73–3.55 [6.98E-07]) | 0.94 | 0.27 | 0.28 | 0.41 | 0.25 | RNU6-219P X , ZNF532 Y , RN7SL112P Z | Intergenic MALT1 AA and ZNF532 |

AMuskelin 1; encodes an intracellular mediator of cell morphology and cytoskeletal responses [52, 53].

BErythrocyte membrane protein band 4.1 like 4B (also known as Ehm2); involved in membrane and cytoskeletal interactions [60].

CCytoskeletal-associated protein tyrosine phosphatase; regulates cell growth, differentiation, mitotic cycle, and oncogenic transformation [61].

DSorbin and SH3 domain containing 1; encodes a CBL-associated protein which functions in the signaling and stimulation of insulin [132].

EAldehyde Dehydrogenase 18 Family, Member A1; Diseases associated with ALDH18A1 include cutis laxa, autosomal recessive, type iiia and aldh18a1-related cutis laxa [149–151].

FSolute carrier protein 1; associated with fatty acid levels, essential tremor and other traits [56–59].

HLysine acetlytransferase 2B (also known as PCAF or p300/CBP associated factor); associated with various phenotypes including inflammatory responses to S. aureus [66–70].

IShugoshin-Like 1 cancer; associated with the cell cycle [102].

JProtein Phosphatase 2C-Like Domain Containing 1; function unknown.

KSGOL1 Antisense RNA 1; RNA gene. Function undefined.

LMicroRNA 3135a; Function undefined.

NRoundabout, axon guidance receptor, homolog 1; encodes a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and neuronal precursor cell migration [74–77].

ORELT-like 1; tumor necrosis receptor family member also involved in immune regulation [109].

PPhosphoglucomutase 2; Catalyzes the conversion of the nucleoside breakdown products ribose-1-phosphate and deoxyribose-1-phosphate [genecards.org].

QGlutathione S-Transferase Alpha 4;involved in cellular defense against toxic, carcinogenic, and pharmacologically active electrophilic compounds [genecards.org].

RRNA, 7SK Small Nuclear; RNA gene [genecards.org].

TRNA, 7SL, Cytoplasmic 244, Pseudogene [genecards.org].

VRNA gene; non coding RNA [genecards.org].

XPseudogene [genecards.org]

YZinc finger protein 532; affects adipogenesis differentiation [110].

ZRNA; unknown function.

In addition, we carried out single variant association tests of intermittent carriage of S. aureus, defined as individuals testing positive for S. aureus colonization at either visit compared to non S. aureus carriers (Fig 2, Table 2). The 7 regions suggestively associated (as defined above) with intermittent carriage include a genome-wide significant finding on chromosome 3 at rs61440199 (p value 8.68 x 10−9) that is intronic to KAT2B (lysine acetyltransferase 2B) (also known as PCAF; p300/CBP-associated factor), a gene associated with post-traumatic stress disorder [66], mean arterial blood pressure [67], adipogenesis [68], development of T regulatory cells [69], and recently shown to be a potential regulator of inflammatory responses following infection with S. aureus in a mouse model of disease (Table 2) [70]. Other signals were at or near UBE2E2 (ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2E 2), a gene that has been associated with risk to gestational and type 2 diabetes [71–73], ICK (intestinal cell [MAK-like] kinase), and ROBO1 (roundabout, axon guidance receptor, homolog 1), which encodes a member of the immunoglobulin gene superfamily and plays a role in axon guidance and neuronal precursor cell migration (Table 2). A SNP highly correlated with ROBO1 expression in the brain has been reproducibly associated with reading disabilities [74, 75], and SNPs mapped to ROBO1 have been associated with levels of liver enzymes [76] and other pQTLs [77]. Three sentinel SNPs were intergenic between (RELT-like 1) and PGM2 (phosphoglucomutase 2), between genes LOC283585 and GALC, and between ZNF532 (zinc finger protein 532) and MALT1 (mucosa associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma translocation gene 1) (Table 2). GALC encodes the enzyme β-galactocerebrosidase, mutations in which are responsible for Krabbe disease [78, 79]. Homozygous mutations in MALT1 have been associated with immunodeficiency [80–82] (Table 2). MALT1 has also been associated with multiple-sclerosis [83]. No common (minor allele frequency >0.05) variants in the whole exome sequencing data reached p value < 10−5 (shown as x’s in the Manhattan plot, Fig 2). LocusZoom plots for each top locus highlight LD patterns among top SNPs (Figs F-L in S1 File). It is notable that the signals for persistent carriage of S. aureus appear to be largely independent of signals for intermittent carriage of S. aureus. Of all top findings, only rs61440199 (KAT2B) and rs16993852 (RELL1) show nominal evidence of association in both persistent and intermittent carriage of S. aureus. Diabetes stratified and non-stratified analyses of both persistent and intermittent carriage gave highly concordant results across all analyses (Figs M-N in S1 File).

Gene-based tests of functional variants

The program VAAST [49, 50] was used to identify genes enriched for functional rare variation in cases based on next generation whole exome sequence data. In the analysis of persistent carriers (131 cases, Table 1) versus non-carriers (573 controls, Table 1) of S. aureus, one gene, FAM123C (APC membrane recruitment protein 3), approached genome-wide significance (p value 6.50 x 10−6) (Table 3). Other top gene-based findings include NGEF (neuronal guanine nucleotide exchange factor, p value 1.22 x 10−5), CCDC69 (coiled-coil domain containing 69, p value 1.40 x 10−5), ERP29 (endoplasmic reticulum protein 29, p value 3.72 x 10−5), and TSGA10IP (testis-specific protein 10-interacting protein, p value 7.45 x 10−5 (Table 3 and Fig O in S1 File). In the analysis of intermittent carriers (88 cases, Table 1) versus non-carriers (573 controls, Table 1) top gene-based findings included SLC4A4 (bicarbonate cotransporter, member 4, p value 2.27 x 10−4), TSPAN11 (tetraspanin 11, p value 1.98 x 10−4), TPO (thyroid peroxidase, p value 4.05 x 10−4), ZNF280D (zinc finger protein 280D, p value 3.76 x 10−4), and CSF2RB (colony stimulating factor 2 receptor, beta, low-affinity, p value 4.15 x 10−4) (Table 3 and Fig P in S1 File). Specific variant enrichment and predicted function of variants driving top gene-based findings are shown in Table 3 and gene functions are discussed below.

Table 3. Top findings from gene-based burden tests of rare functional variation in VAAST for persistent S. aureus carriers versus non-carriers (top) and intermittent S. aureus carriers versus non-carriers (bottom); including PC1, and PC2 as covariates.

| Gene ID | p value, Persistent Carrier (PC) vs. Non Carrier (Eigenscore 1,2) | p value, Intermittent Carrier (INT) vs. Non Carrier (Eigenscore 1,2) | Variant Location | Mutation | Count (PC) | Count (INT) | Count (control) | PC vs Non OR (95% CI) | INT vs Non OR (95% CI) | Mutation Taster Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FAM123C | 6.5x10−6 (4.93x10−6, 8.17x10−6) | 0.156 (0.112, 0.205) | chr2:131520672 | p.D343H | 3/253 | 0/176 | 0/1124 | - | - | polymorphism |

| chr2:131520276–131520278 | p.211_211del | 2/258 | 0/174 | 0/1130 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr2:131520231 | p.R196W | 0/256 | 1/173 | 0/1098 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr2:131520255 | P204A | 2/256 | 0/170 | 0/1108 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| NGEF | 1.22x10−5 (9.54x10−6, 1.5x10−5) | 0.123 (0.084, 0.166) | chr2:233744262 | p.M690I | 3/259 | 1/175 | 0/1146 | - | - | polymorphism |

| chr2:233756151 | p.D397N | 2/258 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr2:233757708 | p.V348M | 1/261 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| CCDC69 | 1.4x10−5 (1.12x10−5, 1.7x10−5) | 0.0399 (0.0254, 0.0561) | chr5:150565006 | p.R198W | 3/259 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | polymorphism |

| chr5:150567017 | p.L108P | 12/240 | 6/166 | 13/1109 | 4.27 (1.92, 9.46) | 3.08 (1.16, 8.22) | damaging A | |||

| ERP29 | 3.72x10−5 (2.79x10−5, 4.71x10−5) | 0.0193 (0.0124, 0.027) | chr12:112460215 | p.K182R | 7/249 | 2/174 | 5/1129 | 6.35 (2.00, 20.16) | 2.60 (0.50, 13.48) | polymorphism |

| chr12:112460316 | p.F216L | 1/261 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr12:112459997 | p.K109N | 1/261 | 1/175 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr12:112460195 | p.E175D | 1/257 | 1/173 | 0/1132 | - | - | damaging | |||

| TSGA10IP | 7.45E-05 (5.59x10−5, 9.43x10−5) | 1 (1, 1) | chr11:65714925 | p.A210V | 30/214 | 9/155 | 56/1008 | 2.52 (1.58, 4.03) | 1.05 (0.51, 2.16) | NA |

| chr11:65715005 | p.R237S | 1/257 | 0/176 | 0/1140 | - | - | NA | |||

| SLC4A4 | 0.236 (0.182, 0.295) | 2.27x10-4 (1.81x10-4, 2.76x10-4) | chr4:72205078 | p.T38I | 0/262 | 1/175 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging |

| chr4:72215759 | p.R130W | 1/261 | 2/174 | 1/1145 | 4.39 (0.27, 70.37) | 13.16 (1.19, 145.92) | damaging | |||

| chr4:72316967 | p.G380D | 1/257 | 4/172 | 4/1140 | 1.11 (0.12, 9.96) | 6.63 (1.64, 26.75) | damaging | |||

| chr4:72319250 | p.A410V | 0/262 | 1/175 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr4:72363275 | p.G634R | 0/260 | 1/171 | 0/1136 | - | - | damaging | |||

| TSPAN11 | 0.113 (0.0757, 0.154) | 1.98x10-4 (1.55x10-4, 2.43x10-4) | chr12:31132507 | p.D120N | 0/262 | 1/175 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging |

| chr12:31135497 | p.D163N | 1/257 | 4/172 | 1/1145 | 4.46 (0.28, 71.47) | 26.63 (2.96, 239.65) | damaging | |||

| TPO | 1 (1, 1) | 4.05x10-4 (3.19x10-4, 4.97x10-4) | chr2:1488616 | p.L356F | 1/261 | 2/174 | 6/1140 | 0.73 (0.09, 6.07) | 2.18 (0.44, 10.91) | damaging |

| chr2:1497657 | p.V445M | 0/256 | 7/169 | 5/1135 | - | 9.40 (2.95, 29.96) | polymorphism | |||

| chr2:1499870 | p.M533V | 0/250 | 7/161 | 4/1110 | - | 12.07 (3.49, 41.67) | polymorphism | |||

| chr2:1544436 | p.G853R | 1/261 | 2/174 | 4/1142 | 1.09 (0.12, 9.83) | 3.28 (0.60, 18.05) | polymorphism | |||

| ZNF280D | 0.0342 (0.0208, 0.0493) | 3.76x10-4 (2.93x10-4, 4.65x10-4) | chr15:56923895 | p.G901V | 1/261 | 3/173 | 13/1133 | 0.33 (0.04, 2.56) | 1.51 (0.43, 5.36) | damaging |

| chr15:56974513 | p.Q302K | 0/254 | 1/171 | 0/1116 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr15:56981270 | p.N237I | 0/260 | 2/174 | 0/1144 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr15:56981286 | p.C232R | 0/260 | 1/175 | 0/1144 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr15:56923952 | p.Q882R | 1/259 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr15:56924054 | p.I848T | 1/261 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr15:56958707 | p.I614T | 1/261 | 0/176 | 0/1146 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr15:56993196 | p.I93V | 1/259 | 0/174 | 0/1142 | - | - | damaging | |||

| CSF2RB | 7.04x10−4 (4,77x10−4, 9.53xx10−4) | 4.15x10-4 (3.27x10-4, 5.08x10-4) | chr22:37326443 | p.E249Q | 14/246 | 21/153 | 65/1077 | 0.94 (0.52, 1.71) | 2.27 (1.35, 3.83) | polymorphism |

| chr22:37326794 | p.D312N | 4/258 | 3/173 | 2/1144 | 8.87 (1.62, 48.68) | 9.92 (1.65, 59.79) | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37328885 | p.R364L | 1/255 | 1/173 | 0/1128 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37331407 | p.V444M | 0/262 | 1/175 | 0/1144 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37319324 | p.Y39H | 1/261 | 0/176 | 0/1144 | - | - | damaging | |||

| chr22:37326794 | p.D312N | 4/258 | 3/173 | 2/1144 | 8.87 (1.62, 48.68) | 9.92 (1.65, 59.79) | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37328885 | p.R364L | 1/255 | 1/173 | 0/1128 | - | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37329979 | p.G420S | 2/254 | 0/176 | 1/1141 | 8.98 (0.81, 99.47) | - | polymorphism | |||

| chr22:37334510 | p.P887R | 1/257 | 0/176 | 0/1140 | - | - | polymorphism |

APredicted to be a disease causing polymorphism by CASM (Conservation-Controlled Amino Acid Substitution Matrix Prediction)(72).

As in the single variant analysis of 1000 Genomes imputed data and common variants from the exome sequence data, the gene-based findings in analyses of intermittent carriers of S. aureus appear to be largely independent between analyses of persistent versus intermittent carriage groups (Table 3). Only genes CCDC69 and ZNF280D reach nominal levels of significance (p value < 0.05) in both tests. CSF2RB shows suggestive enrichment of missense variation in both analyses, and may constitute a gene involved in general S. aureus carriage susceptibility (Table 3). Shared signals should be interpreted with caution given that the non-carriage control group is the same in both tests, and thus the two tests are not strictly independent. As observed for the single variant association tests, diabetes stratified and non-stratified analyses gave highly concordant results across all analyses (Figs Q-R in S1 File). Manhattan and QQ plots suggest the type 1 error for both single variant and gene-based tests are well controlled (Figs M-R in S1 File).

We used the Disease Association Protein-Protein Link Evaluator (DAPPLE) [84] to identify interactions between proteins encoded by the top 5 candidate genes in the persistent versus non-carrier and intermittent versus non-carrier VAAST runs. DAPPLE searches for protein-protein interactions among a candidate gene list; a significant number of protein-protein interaction may indicate a shared molecular pathway relevant to S. aureus susceptibility. In the analysis of persistent carriers versus non-carriers we did not detect any direct protein-protein interactions. However, among the top 5 genes identified from the intermittent carriers versus non-carriers run, we found that TPO is directly interacting with CSF2RB (Fig S in S1 File). The p-value for observing at least one interaction among the top 5 genes is 0.008; the p-values for observing at least one interacting protein for TPO and CSF2RB are 0.015 and 0.014, respectively.

Replication of previously identified loci

We compared our persistent carriage single variant and gene-based test results to all sites previously reported in genetic analyses of S. aureus (S1 Table) [20–23, 27, 30–32, 34, 35, 85]. When the variant in question was not present in our post-quality control imputed or exome sequenced variant lists, and therefore not analyzed in this study, we identified the best proxy variant by assessing linkage disequilibrium patterns in the Mexican-American (MEX) reference population within the 1000 Genomes Project data (release 27). In these cases, statistics for the variant with the highest linkage disequilibrium r2 are provided in S1 Table.

With the exception of CDK7 (discussed below) our findings do not replicate the genes and variants described in 2 previously conducted genome wide association studies, possibly because of several differences between these prior studies and the current study (described in the Discussion)[34, 35]. We found suggestive evidence of association at rs4918120 (p value 0.034) a SNP previously identified by Nelson et al. [34] in Caucasian inpatients; however, we observed the opposite direction of effect of the T allele (odds ratio 0.70 versus 1.68, see S1 Table). Interrogation of our single variant test results for intermittent carriage at previously reported loci yielded replication at three loci identified by Ye et al. [35]: rs12696090 (p value 0.0214), rs7643377 (p value 0.0081), and rs9867210 (p value 0.0079), however as before; we find opposite direction of effect at each of these loci (S1 Table).

We also examined our gene-based test results for replication of previous findings at genes near previously associated SNPs and genes. CDK7 (cyclin-dependent kinase) (gene-based p value 0.040) replicates findings by Ye et al. [35] who studied genetic risk of hospital-based S. aureus infection in Caucasians and identified CDK7 using gene-based tests in the program VEGAS (S1 Table).

Discussion

This was the first genome-wide association study of S. aureus carriage states in a community-based representative population. This approach is significantly different from previously described genome-wide association studies that were carried out in the context of S. aureus infections [34, 35]. We found genome-wide significance at 1 gene region and 11 other regions meeting suggestive levels of significance for association with persistent and intermittent carriage states by single variant analysis. We also reported the 5 top findings from gene-based tests of persistent and intermittent carriage. The lack of overlap in signals between gene-based tests of rare functional variation and single-variant tests suggested that genome-wide association signals were not driven by coding sequence variation. Non-genic regulatory factors affecting gene expression levels or post-translational modifications may also affect carriage phenotypes.

We found that top signals associated with persistent and intermittent carriage captured genes of different cellular functions. Genome-wide single variant analysis identified 5 gene regions suggestively associated with persistent carriage. Gene-based rare variant analysis identified 5 genes in association with persistent carriage. Near genome-wide significance was observed only for FAM123C (p value < 6.50 x 10−6). Each of these genes (except for TSGA10IP, which has not been previously described to our knowledge) was involved with cellular growth, tissue homeostasis, and/or cancer [86–92]. It should be noted however, that TSGA10IP (TSGA10 interacting protein) interacts with TSGA10, a protein also associated with cancer and that binds cytoskeletal proteins (e.g., vimentin and actin-γ1) [93, 94].

In analyses of persistent S. aureus carriage, all of the top 5 findings from gene-based tests and all regions identified in the single variant analysis harbored at least 1 gene associated with either regulation of cell growth or maintenance of cellular integrity (e.g., tight junctions) [95, 96]. Conversely, a minority of genes identified in previous genome-wide association studies of S. aureus infection were involved in cell cycle, cellular growth, or cellular integrity (S1 Table) [34, 35]. These differences are important for 2 reasons: i) carriage and infection are not mutually exclusive i.e., the S. aureus carriage status of individuals was not established in relation to the infections described in the previous genome-wide association studies, and ii) susceptibility to infections in hospital environments may not accurately reflect an individual's susceptibility to an infectious agent. Hospital environments in and of themselves place patients at increased risk for infections with numerous pathogens including S. aureus, an agent responsible for more healthcare-associated infections and surgical site infections than any other pathogen [97].

Genome-wide association analysis of intermittent carriage identified a different set of genes from those identified in association with persistent carriage. This analysis identified 7 gene regions. The top signal (rs61440199) was genome-wide significant (p value 8.68 x 10−9) and intronic to KAT2B. This gene was of particular interest since its expression in mice was affected by the nature of the infecting S. aureus strain [70]. In addition, KAT2B has been linked to immune function, cancer progression, and adipogenesis [68, 98–100]. The association of KAT2B with cancer progression/cell cycle was also shared by SGOL, ROBO1, and ICK, and represents the only functional overlap with genes identified with persistent and intermittent carriage of S. aureus [101–107]. The other themes observed in the context of genes associated with intermittent carriage were genes associated with both adipogenesis and inflammation/immunity (KAT2B, ZNF532, RELL1, FOXO9, MALT1) [68, 80, 98, 100, 101, 103, 108–112]. In light of sample ascertainment for diabetes in this cohort [40], a gene in 1 region, UBE2E2, was of interest because of prior associations with diabetes risk [71–73], however, stratification for diabetes provided highly concordant results with the unstratified analysis (data not shown). Our gene-based analyses did not model complications that present in diabetic patients (e.g., obesity, immune function, elevated blood glucose levels) that may alter susceptibility to intermittent carriage. The number of adipogenesis genes linked to intermittent carriage may be of significance in light of recent studies that identified a protective role for adipose tissue in a murine model of S. aureus skin infection, suggesting that immune factors produced by adipose tissues (e.g., antimicrobial peptides) may play a role in intermittent carriage [112].

Although gene-based analyses of rare functional variants failed to identify any genome-wide significant differences in association with intermittent carriage, a top signal, CSF2RB, demonstrated concordance of burden in both persistent and intermittent carriers (p value 7.04 x 10−4 and p value < 4.15 x 10−4, respectively). CSF2RB codes for CD131, the common β receptor subunit for IL-3, IL-5, and GM-CSF (granulocyte/monocyte colony stimulating factor) that in mice was shown to play a role in regulating Th2 type immune responses [113]. In addition, CD131 stimulated the recruitment of neutrophils (which are a key innate immune component) and controlled the homeostasis of tissue dendritic cells [114, 115]. In addition, DAPPLE analysis identified a significant protein-protein interaction between the CSF2RB and TPO gene products. TPO is critical to the production of thyroid hormones that can impact immune function and is also associated with mucinosis (myxedema), a disease characterized by increased glycosaminoglycan deposition in the skin [116, 117]. Other than CSF2RB, no other top finding in the gene-based tests were even modestly associated with both persistent and intermittent carriage.

Results from the 2 previously described genome-wide association studies identified a number of loci with statistical significance. However, those associations were for the most part not replicated in our studies or previous work [9, 18–23, 27, 30, 32, 34, 35, 85, 118]. Lack of replication between studies may be due to population differences, the impact of the respective colonizing/infecting S. aureus strains (and their relationship with distinct human genetic determinants), study design (i.e., S. aureus infection versus carriage), and the size of respective populations examined [9, 22]. Replication of 1 gene identified by gene-based tests was observed in the context of persistent carriage that identified CDK7 (p value 0.041) from the VEGAS gene test conducted by Ye et al. (S1 Table). We also assessed gene-based evidence of replication in our analyses of intermittent carriage versus non-carriage and found no support for previously identified genes (data not shown).

Previous colonization studies have suggested that the 3 described staphylococcal carriage phenotypes (persistent, intermittent, and non-carriers) be modified to include only 2 carriage phenotypes: persistent carriers and intermittent/non-carriers [17]. However gene targets identified in the present S. aureus carriage genome-wide association study suggested that each phenotype is distinct. That the genome-wide association and rare variant analyses identified relatively little functional similarity between persistent and intermittent carriers may suggest underlying differences between these 2 carriage states. An alternate explanation is that these studies lacked sufficient power to identify common factors across the carriage states. Despite the recommendation of previous studies to consider intermittent and non-carriers as a single group, this reclassification would require ignoring the differences that exist between these 2 carriage states. It is clear, however, that persistent carriers represent the most distinct carriage state. This is supported by colonization studies that demonstrated that non-carriers (and decolonized intermittent carriers) artificially inoculated with S. aureus in the nares cleared the bacteria over a similar time period (4 days for non-carriers and 14 days for intermittent carriers) compared to persistent carriers (decolonized and then re-inoculated) that still harbored the S. aureus inoculum >154 days later [17]. Persistent carriers also had a different antibody profile against some staphylococcal virulence factors compared to the indistinguishable profile described for non-carriers and intermittent carriers [17]. In addition, persistent carriers that were decolonized and re-inoculated with a heterogeneous mix of S. aureus isolates were more likely to be re-colonized with their original colonizing isolate suggestive of an intimate association between the colonizing strain and the host [17].

This difference between persistent carriers and intermittent carriers (and intermittent carriers and non-carriers) is further accentuated by the function of the genes associated with the respective carriage states. Almost all determinants associated with persistent carriage were associated with cellular integrity, morphology, and growth, functions that directly hold the potential of impacting the host/pathogen interface that establishes environments permissive to persistent carriage.

Attachment to host surfaces is requisite for colonization and infection of host tissues by pathogens. S. aureus possesses an arsenal of adhesins capable of binding an array of host extracellular matrix (ECM) components. These components include fibrinogen, fibronectin, collagen, cytokeratin 10, elastin, heparan sulfate proteoglycans, von Willebrand factor, bone sialoprotein, vitronectin, and prothrombin that all facilitate the colonization of diverse tissues and accounts in part for the myriad of diseases than can result following infection with this pathogen [119–121]. It is not surprising therefore that host polymorphisms potentially affecting cellular integrity, morphology and growth could also impact colonization with different pathogens or strains of the same pathogen.

That various potential genes identified by the genome-wide association study (e.g., ALDH18A1, EPB41L4B, FGF3, and FGF4) and all but 1 gene identified in the rare variant analysis have been shown to possess tumorogenic potential should not be surprising since various genes shown to play roles in the progression of various cancers also play critical roles in wound healing, cellular migration, cellular integrity, and angiogenesis [60, 122, 123]. Polymorphisms in these gene products or any gene products with the potential of altering the structural integrity of the host cell could potentially impact staphylococcal colonization.

Focal adhesions represent large, multi-protein complexes that are closely associated with cell surface integrins that span the eukaryotic plasma membrane linking the cellular cytoskeleton to the ECM (surrounding the cell) [124]. Most integrins and their respective focal adhesions are expressed in the epidermis and regulate epithelial cell homeostasis by mediating cell adhesion processes (and signaling) critical to tissue repair following injury [124]. Of the gene targets identified in association with S. aureus persistent carriage, EHM2, PTPN3, SORS1, and MKLN1 can impact the integrity of focal adhesions that in turn alters the cytoskeleton [53, 120, 124–133].

SORBS1 encodes CAP (Cbl-Associated Protein) [129, 132, 134] that affects insulin receptor signaling and also functions as a cytoskeletal regulatory protein [129]. In fibroblasts, when CAP associates with actin stress fibers, focal adhesion kinase binds CAP, and CAP over-expression induces the development of actin stress fibers and focal adhesions that physically link intracellular actin bundles to the extracellular substrates of many cell types [127, 135]. Various pathogens like S. aureus usurp focal adhesions as a means of triggering their uptake by various non-professional antigen presenting cells, including epithelia/endothelial cells, osteoclasts, kidney cells, fibroblasts and keratinocytes [120]. S. aureus possess various fibronectin binding proteins (e.g., FnbpA, FnbpB, ClfA, ClfB) that facilitate coating the bacterial surface with this matrix molecule that in turn binds to α5β1 integrins resulting in the formation of a molecular bridge linking S. aureus to the host cell [125]. This interaction triggers the recruitment of focal adhesion proteins that further alter the cytoskeleton facilitating attachment, invasion, and the ability to persist in their hosts [125]. The importance of this interaction for the successful attachment/invasion of human cells by staphylococci was demonstrated by generating fnbpA/fnbpB-deficient S. aureus that less effectively infected epithelial cells and in a mastitis model caused less severe disease [136, 137]. Furthermore, cells unable to form focal adhesions were resistant to integrin α5β1-mediated cellular invasion by S. aureus [120, 127].

EHM2 is a member of the 4.1R, ezrin, radixin, moesin (FERM) protein superfamily consisting of over 40 proteins that contain the characteristic 3-lobed FERM domain on the N-terminus that binds various cell membrane-associated proteins and lipids and the spectrin/actin binding domain (SABD) at the C-terminus [126]. The PTPN3 gene product also belongs to the FERM family and is a protein phospatase that is a structural constituent of the cytoskeletal shown to play a role in T cell activation, maintenance of tight junction integrity (between the cell membrane and the cytoskeleton) and both EHM2 and PTPN3 gene products are associated with focal adhesions [95, 128, 130, 133, 138]. EHM2 expression has been observed on wounds undergoing healing (primarily at the wound's leading edge) functioning as a positive regulator of keratinocyte adhesion and motility in addition to affecting the rates of cellular invasion and adhesion to collagen via regulation of matrix metaloprotease 9 (MMP9) i.e., EHM2 knockdown cells expressed significantly reduced levels of MMP9. This is of interest in the context of S. aureus since up- or down-regulation of MMP9 levels has been shown to affect disease progression resulting from S. aureus infections, that is, MMP9 levels that are either too high or too low can negatively affect wound healing and MMP9-deficient mice poorly controlled S. aureus infections [60, 126, 131, 139–143]. In addition, MMPs play critical roles in tissue remodeling (including the maintenance of the ECM), altering immune cell migration and infiltration patterns, and impacted inflammation by exerting effects on cytokines and chemokines [143, 144]. As it relates to S. aureus colonization, a role for MMP9 has yet to be described; however, staphylococcal lipoteichoic acid has been shown to increase production of MMP9 in middle ear epithelial cells suggesting that increased MMP9 levels could be involved in progression of otitis media [141].

Unlike EHM2, PTPN3, and SORS1; the MKLN1 gene product muskelin mediates ECM binding via complex mechanisms involving interactions between different thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) domains and various ligands (expressed by different cell types) including integrins, proteoglycans, or integrin-associated proteins. Alterations to muskelin expression levels altered attachment to TSP-1 in association with subtle changes to the organization of focal contacts [53]. Since TSP-1 has also been shown to serve as a ligand for S. aureus, polymorphisms in MKLN1 could alter staphylococcal binding or prevent clearance of S. aureus since TSP-1 breakdown products function as antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) that have broad antibacterial properties affecting both Gram-positive and -negative bacteria [145–148].

Homozygous mutations in ALDH18A1 (or other genes e.g., PYCR1, ATP6V0A2) can result in a heteogenous group of rare diseases characterized by loose or wrinkly skin known as cutis laxa [149–151]. Histologic analysis of skin from cutis laxa patients identified reduced elastin levels with less-well defined collagen fibers lacking the characteristic wavy morphology. In addition, collagen I and III levels were significantly reduced, and fibroblasts harvested from the dermis presented with reduced growth rates [149]. The majority of studies that have examined genes resulting in this rare condition have only described case reports of patients with homozygous mutations, making it difficult to interpret how polymorphisms with a less pronounced phenotype present at the cytoskeletal level.

Although adherence to host surfaces also represents a component of intermittent carriage (i.e., the organism has to attach to host tissues even if this association is transient), the intermittent periods of carriage, carriage of different strains over time, carriage of multiple strains, and the reduced S. aureus inocula recoverable from the nares of intermittent carriers suggests that different determinants are associated with this phenotype [17]. This is emphasized by the observation that the majority of gene targets associated with intermittent carriage were also associated with immune function/inflammation.

Our data suggested that determinants associated with persistent carriage and intermittent carriage differed. A limitation to the present study was the analysis of only two nasal swabs to establish carriage. Even though Nouwen et al. established that the 'two-culture' rule was 93.6% reliable [39] and numerous studies have used this approach to establish S. aureus carriage phenotypes [20, 38, 118, 152–156] there exists room for classification error. Second, because only one nostril was sampled some participants may have been misclassified as intermittent or non carriers based on one study that described differences in S. aureus carriage between colonization [157]; however, two other studies did not identify any differences [158, 159]. It should be noted that samples that were collected and analyzed for the present study were of the ciliated pseudostratified columnar epithelium associate the inferior and middle concha and not the nonkeratinized, squamous epithelium present in the anterior nares and used to establish S. aureus carriage by other studies. Furthermore, due to population differences and power we should be cautious in making assumptions with regard to specific genes associated with respective carriage states. We should therefore further dissect the observation that persistent carriage of S. aureus is affected primarily by polymorphisms at the host/pathogen interface and that intermittent carriage is more likely impacted by environmental factors combined with the heterogeneity of the host immune response.

Supporting Information

Figs A-E. LocusZoom plots of each top finding in the single variant association analyses of persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier. (A) EPB41L4B, (B) LINC-PINT, (C) SORBS1, ALDH18A1, (D) SLC1A2, and (E) FGF4, FGF3. Figs F-L. LocusZoom plots of each top finding in the single variant association analyses of persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier. (F) KAT2B, (G) UBE2E2, MIR548AC, (H) ROBO1, (I) RELL1, (J) GSTA4, ICK, FBXO9, (K) LOC283585, GALC, and (L) ZNF532. Fig M. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of single variant logistic regression of persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier, including diabetes, PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represents a single polymorphic variant with minor allele frequency greater than 0.05. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for the same variants shown in (a). Grey shading indicates the 95% confidence interval, the solid line indicates the expected null distribution, and the dotted line indicates the slope after lambda correction for genomic control. The 1,011 common variants identified by whole exome sequencing are shown as x’s in the Manhattan plots. Fig N. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of single variant logistic regression of intermittent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier, including diabetes, PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represents a single polymorphic variant with minor allele frequency greater than 0.05. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for the same variants shown in (a). Grey shading indicates the 95% confidence interval, the solid line indicates the expected null distribution, and the dotted line indicates the slope after lambda correction for genomic control. The 1,011 common variants identified by whole exome sequencing are shown as x’s in the Manhattan plots. Figs O. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of gene-based burden tests of rare functional variation in VAAST for persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier including PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represent one protein-coding gene. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for all protein-coding genes, grey shading represents 95% confidence interval, the red line indicates the null distribution of p-values. Fig P. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of gene-based burden tests of rare functional variation in VAAST for intermittent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier including PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represent one protein-coding gene. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for all protein-coding genes, grey shading represents 95% confidence interval, the red line indicates the null distribution of p-values. Fig Q. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of gene-based burden tests of rare functional variation in VAAST for persistent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier including diabetes, PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represent one protein-coding gene. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for all protein-coding genes, grey shading represents 95% confidence interval, the red line indicates the null distribution of p-values. Fig R. Manhattan (a) and QQ plots (b) of results of gene-based burden tests of rare functional variation in VAAST for intermittent S. aureus carriage versus non-carrier including diabetes, PC1, and PC2 as covariates. The x-axis represents the chromosome number and each dot represent one protein-coding gene. QQ plot shows the observed versus expected p-values for all protein-coding genes, grey shading represents 95% confidence interval, the red line indicates the null distribution of p-values. Fig S. Protein-protein interactions among top-5 candidate genes in the gene-based test of intermittent carriersversus non-carriers analysis. Red: genes that encode proteins with direct interactions to another top-5 candidate; blue: genes that encode proteins with second-degree interactions to another top-5 candidate; grey: genes that are not top-5 candidates, but encode proteins interacting with at least two top-5 candidates. The figure was generated using DAPPLE software.

(DOCX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI085014-01A1 (E.L. Brown and C.L. Hanis), R01 GM104390 (C.D. Huff and H. Hao), HL102830 (C.L. Hanis), DK085501 (C.L. Hanis) and P30DK020595 (G.I. Bell). H. Hao is also supported by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Odyssey Program. This work was also partially supported from a grant from the Kleberg Foundation to E.L.B. Genotyping imputation and whole exome sequencing were performed as part of our involvement in the T2D-GENES Consortium and we acknowledge those efforts. We also express appreciation to the field staff in Starr County who contacted and collected the necessary participant data and samples. Lastly, we thank the participants for their generous and willing participation.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by NIH grants R01 AI085014-01A1 (E.L. Brown and C.L. Hanis), R01 GM104390 (C.D. Huff and H. Hao), HL102830 (C.L. Hanis), DK085501 (C.L. Hanis) and P30DK020595 (G.I. Bell). H. Hao is also supported by the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center Odyssey Program. This work was also partially supported from a grant from the Kleberg Foundation to E.L. Brown. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Kwiatkowski DP. How malaria has affected the human genome and what human genetics can teach us about malaria. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77(2):171–92. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu R, Paxton WA, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin SR, Horuk R, et al. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86(3):367–77. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bellamy R. Genetic susceptibility to tuberculosis. Clin Chest Med. 2005;26(2):233–46, vi . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Frodsham AJ, Zhang L, Dumpis U, Taib NA, Best S, Durham A, et al. Class II cytokine receptor gene cluster is a major locus for hepatitis B persistence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103(24):9148–53. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lindesmith L, Moe C, Marionneau S, Ruvoen N, Jiang X, Lindblad L, et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med. 2003;9(5):548–53. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Zeidler M, Stewart G, Cousens SN, Estibeiro K, Will RG. Codon 129 genotype and new variant CJD. Lancet. 1997;350(9078):668 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Levine MM, Nalin DR, Rennels MB, Hornick RB, Sotman S, Van Blerk G, et al. Genetic susceptibility to cholera. Ann Hum Biol. 1979;6(4):369–74. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Malaty HM, Engstrand L, Pedersen NL, Graham DY. Helicobacter pylori infection: genetic and environmental influences. A study of twins. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):982–6. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sollid JU, Furberg AS, Hanssen AM, Johannessen M. Staphylococcus aureus: determinants of human carriage. Infect Genet Evol. 2014;21:531–41. 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.03.020 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Embil J, Ramotar K, Romance L, Alfa M, Conly J, Cronk S, et al. Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus in tertiary care institutions on the Canadian prairies 1990–1992. Infection control and hospital epidemiology: the official journal of the Society of Hospital Epidemiologists of America. 1994;15(10):646–51. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Hill PC, Wong CG, Voss LM, Taylor SL, Pottumarthy S, Drinkovic D, et al. Prospective study of 125 cases of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in children in New Zealand. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2001;20(9):868–73. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Tong SY, Bishop EJ, Lilliebridge RA, Cheng AC, Spasova-Penkova Z, Holt DC, et al. Community-associated strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus in indigenous Northern Australia: epidemiology and outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(10):1461–70. 10.1086/598218 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lowy FD. Staphylococcus aureus infections. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:520–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kalmeijer MD, Coertjens H, van Nieuwland-Bollen PM, Bogaers-Hofman D, de Baere GA, Stuurman A, et al. Surgical site infections in orthopedic surgery: the effect of mupirocin nasal ointment in a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;35(4):353–8. 10.1086/341025 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. von Eiff C, Becker K, Machka K, Stammer H, Peters G. Nasal carriage as a source of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(1):11–6. 10.1056/NEJM200101043440102 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wertheim HF, Vos MC, Ott A, van Belkum A, Voss A, Kluytmans JA, et al. Risk and outcome of nosocomial Staphylococcus aureus bacteraemia in nasal carriers versus non-carriers. Lancet. 2004;364(9435):703–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. van Belkum A, Verkaik NJ, de Vogel CP, Boelens HA, Verveer J, Nouwen JL, et al. Reclassification of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage types. J Infect Dis. 2009;199(12):1820–6. Epub 2009/05/08. 10.1086/599119 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Vandenbergh MF, Verbrugh HA. Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: epidemiology and clinical relevance. J Lab Clin Med. 1999;133(6):525–34. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. von Kockritz-Blickwede M, Rohde M, Oehmcke S, Miller LS, Cheung AL, Herwald H, et al. Immunological mechanisms underlying the genetic predisposition to severe Staphylococcus aureus infection in the mouse model. Am J Pathol. 2008;173(6):1657–68. 10.2353/ajpath.2008.080337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. van den Akker EL, Nouwen JL, Melles DC, van Rossum EF, Koper JW, Uitterlinden AG, et al. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage is associated with glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(6):814–8. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. van Belkum A, Emonts M, Wertheim H, de Jongh C, Nouwen J, Bartels H, et al. The role of human innate immune factors in nasal colonization by Staphylococcus aureus . Microbes Infect. 2007;9(12–13):1471–7. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Emonts M, Uitterlinden AG, Nouwen JL, Kardys I, Maat MP, Melles DC, et al. Host polymorphisms in interleukin 4, complement factor H, and C-reactive protein associated with nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and occurrence of boils. J Infect Dis. 2008;197(9):1244–53. 10.1086/533501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Emonts M, de Jongh CE, Houwing-Duistermaat JJ, van Leeuwen WB, de Groot R, Verbrugh HA, et al. Association between nasal carriage of Staphylococcus aureus and the human complement cascade activator serine protease C1 inhibitor (C1INH) valine vs. methionine polymorphism at amino acid position 480. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;50(3):330–2. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cole AM, Tahk S, Oren A, Yoshioka D, Kim YH, Park A, et al. Determinants of Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8(6):1064–9. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Schumann RR. Host cell-pathogen interface: molecular mechanisms and genetics. Vaccine. 2004;22 Suppl 1:S21–4. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Clementi M, Forabosco P, Amadori A, Zamarchi R, De Silvestro G, Di Gianantonio E, et al. CD4 and CD8 T lymphocyte inheritance. Evidence for major autosomal recessive genes. Hum Genet. 1999;105(4):337–42. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Panierakis C, Goulielmos G, Mamoulakis D, Maraki S, Papavasiliou E, Galanakis E. Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage might be associated with vitamin D receptor polymorphisms in type 1 diabetes. Int J Infect Dis. 2009. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. O'Brien LM, Walsh EJ, Massey RC, Peacock SJ, Foster TJ. Staphylococcus aureus clumping factor B (ClfB) promotes adherence to human type I cytokeratin 10: implications for nasal colonization. Cell Microbiol. 2002;4(11):759–70. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Moore CE, Segal S, Berendt AR, Hill AV, Day NP. Lack of association between Toll-like receptor 2 polymorphisms and susceptibility to severe disease caused by Staphylococcus aureus . Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11(6):1194–7. . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ruimy R, Angebault C, Djossou F, Dupont C, Epelboin L, Jarraud S, et al. Are host genetics the predominant determinant of persistent nasal Staphylococcus aureus carriage in humans? J Infect Dis. 2010;202(6):924–34. 10.1086/655901 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Fode P, Larsen AR, Feenstra B, Jespersgaard C, Skov RL, Stegger M, et al. Genetic variability in beta-defensins is not associated with susceptibility to Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e32315 10.1371/journal.pone.0032315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Nurjadi D, Herrmann E, Hinderberger I, Zanger P. Impaired beta-defensin expression in human skin links DEFB1 promoter polymorphisms with persistent Staphylococcus aureus nasal carriage. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(4):666–74. 10.1093/infdis/jis735 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stappers MH, Thys Y, Oosting M, Plantinga TS, Ioana M, Reimnitz P, et al. TLR1, TLR2, and TLR6 gene polymorphisms are associated with increased susceptibility to complicated skin and skin structure infections. J Infect Dis. 2014;210(2):311–8. 10.1093/infdis/jiu080 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nelson CL, Pelak K, Podgoreanu MV, Ahn SH, Scott WK, Allen AS, et al. A genome-wide association study of variants associated with acquisition of Staphylococcus aureus bacteremia in a healthcare setting. BMC infectious diseases. 2014;14:83 10.1186/1471-2334-14-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ye Z, Vasco DA, Carter TC, Brilliant MH, Schrodi SJ, Shukla SK. Genome wide association study of SNP-, gene-, and pathway-based approaches to identify genes influencing susceptibility to Staphylococcus aureus infections. Frontiers in genetics. 2014;5:125 10.3389/fgene.2014.00125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. System N. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) System Report, Data Summary from January 1990-May 1999, issued June 1999. A report from the NNIS System. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27(6):520–32. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hayes MG, Pluzhnikov A, Miyake K, Sun Y, Ng MC, Roe CA, et al. Identification of type 2 diabetes genes in Mexican Americans through genome-wide association studies. Diabetes. 2007;56(12):3033–44. 10.2337/db07-0482 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Leung NS, Padgett P, Robinson DA, Brown EL. Prevalence and behavioural risk factors of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization in community-based injection drug users. Epidemiology and infection. 2014:1–10. 10.1017/S0950268814003227 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nouwen JL, Ott A, Kluytmans-Vandenbergh MF, Boelens HA, Hofman A, van Belkum A, et al. Predicting the Staphylococcus aureus nasal carrier state: derivation and validation of a "culture rule". Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(6):806–11. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Below JE, Gamazon ER, Morrison JV, Konkashbaev A, Pluzhnikov A, McKeigue PM, et al. Genome-wide association and meta-analysis in populations from Starr County, Texas, and Mexico City identify type 2 diabetes susceptibility loci and enrichment for expression quantitative trait loci in top signals. Diabetologia. 2011;54(8):2047–55. 10.1007/s00125-011-2188-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Staples J, Nickerson DA, Below JE. Utilizing graph theory to select the largest set of unrelated individuals for genetic analysis. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(2):136–41. 10.1002/gepi.21684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nature methods. 2012;9(2):179–81. 10.1038/nmeth.1785 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Howie B, Fuchsberger C, Stephens M, Marchini J, Abecasis GR. Fast and accurate genotype imputation in genome-wide association studies through pre-phasing. Nature genetics. 2012;44(8):955–9. 10.1038/ng.2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marchini J, Howie B. Genotype imputation for genome-wide association studies. Nature reviews Genetics. 2010;11(7):499–511. 10.1038/nrg2796 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Marchini J, Howie B, Myers S, McVean G, Donnelly P. A new multipoint method for genome-wide association studies by imputation of genotypes. Nat Genet. 2007;39(7):906–13. 10.1038/ng2088 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS genetics. 2006;2(12):e190 10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, et al. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. American journal of human genetics. 2007;81(3):559–75. 10.1086/519795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yandell M, Huff C, Hu H, Singleton M, Moore B, Xing J, et al. A probabilistic disease-gene finder for personal genomes. Genome Res. 2011;21(9):1529–42. 10.1101/gr.123158.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Hu H, Huff CD, Moore B, Flygare S, Reese MG, Yandell M. VAAST 2.0: improved variant classification and disease-gene identification using a conservation-controlled amino acid substitution matrix. Genet Epidemiol. 2013;37(6):622–34. 10.1002/gepi.21743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hu H, Roach JC, Coon H, Guthery SL, Voelkerding KV, Margraf RL, et al. A unified test of linkage analysis and rare-variant association for analysis of pedigree sequence data. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(7):663–9. 10.1038/nbt.2895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Epstein MP, Duncan R, Jiang Y, Conneely KN, Allen AS, Satten GA. A permutation procedure to correct for confounders in case-control studies, including tests of rare variation. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91(2):215–23. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Valiyaveettil M, Bentley AA, Gursahaney P, Hussien R, Chakravarti R, Kureishy N, et al. Novel role of the muskelin-RanBP9 complex as a nucleocytoplasmic mediator of cell morphology regulation. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;182(4):727–39. 10.1083/jcb.200801133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Adams JC, Seed B, Lawler J. Muskelin, a novel intracellular mediator of cell adhesive and cytoskeletal responses to thrombospondin-1. The EMBO journal. 1998;17(17):4964–74. 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Ding L, Abebe T, Beyene J, Wilke RA, Goldberg A, Woo JG, et al. Rank-based genome-wide analysis reveals the association of ryanodine receptor-2 gene variants with childhood asthma among human populations. Human genomics. 2013;7:16 10.1186/1479-7364-7-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Comuzzie AG, Cole SA, Laston SL, Voruganti VS, Haack K, Gibbs RA, et al. Novel genetic loci identified for the pathophysiology of childhood obesity in the Hispanic population. PloS one. 2012;7(12):e51954 10.1371/journal.pone.0051954 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guan W, Steffen BT, Lemaitre RN, Wu JH, Tanaka T, Manichaikul A, et al. Genome-wide association study of plasma N6 polyunsaturated fatty acids within the cohorts for heart and aging research in genomic epidemiology consortium. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2014;7(3):321–31. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.113.000208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Thier S, Lorenz D, Nothnagel M, Poremba C, Papengut F, Appenzeller S, et al. Polymorphisms in the glial glutamate transporter SLC1A2 are associated with essential tremor. Neurology. 2012;79(3):243–8. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31825fdeed [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Garcia-Martin E, Martinez C, Serrador M, Alonso-Navarro H, Navacerrada F, Agundez JA, et al. SLC1A2 rs3794087 variant and risk for migraine. Journal of the neurological sciences. 2014;338(1–2):92–5. . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jimenez-Jimenez FJ, Alonso-Navarro H, Martinez C, Zurdo M, Turpin-Fenoll L, Millan-Pascual J, et al. The solute carrier family 1 (glial high affinity glutamate transporter), member 2 gene, SLC1A2, rs3794087 variant and assessment risk for restless legs syndrome. Sleep medicine. 2014;15(2):266–8. 10.1016/j.sleep.2013.08.800 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bosanquet DC, Ye L, Harding KG, Jiang WG. Expressed in high metastatic cells (Ehm2) is a positive regulator of keratinocyte adhesion and motility: The implication for wound healing. Journal of dermatological science. 2013;71(2):115–21. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2013.04.008 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gao Q, Zhao YJ, Wang XY, Guo WJ, Gao S, Wei L, et al. Activating mutations in PTPN3 promote cholangiocarcinoma cell proliferation and migration and are associated with tumor recurrence in patients. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(5):1397–407. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.01.062 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Turnbull C, Ahmed S, Morrison J, Pernet D, Renwick A, Maranian M, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies five new breast cancer susceptibility loci. Nature genetics. 2010;42(6):504–7. 10.1038/ng.586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Riazuddin S, Ahmed ZM, Hegde RS, Khan SN, Nasir I, Shaukat U, et al. Variable expressivity of FGF3 mutations associated with deafness and LAMM syndrome. BMC medical genetics. 2011;12:21 10.1186/1471-2350-12-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sensi A, Ceruti S, Trevisi P, Gualandi F, Busi M, Donati I, et al. LAMM syndrome with middle ear dysplasia associated with compound heterozygosity for FGF3 mutations. American journal of medical genetics Part A. 2011;155A(5):1096–101. 10.1002/ajmg.a.33962 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Pruim RJ, Welch RP, Sanna S, Teslovich TM, Chines PS, Gliedt TP, et al. LocusZoom: regional visualization of genome-wide association scan results. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(18):2336–7. 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]