Abstract

BACKGROUND

The role of liver transplantation in management of patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) is controversial. Because many such patients have low waitlist priority, centers may apply for MELD exception points to increase likelihood of receiving a liver transplant. No formal criteria exist for application or receipt of exception points for this indication. Few studies have assessed waitlist and posttransplantation outcomes in patients with metastatic NETs, and none examined the impact of exception points.

METHODS

We analyzed all adult patients waitlisted for liver transplantation for metastatic NETs between February 27, 2002 and June 4, 2014 and fit a multivariable model to evaluate the association between exception point status and posttransplantation outcomes.

RESULTS

There was variable use of MELD exception points across the UNOS regions. Patients with an approved MELD exception were nearly twice as likely to be transplanted as those without exceptions (70.8% vs 39.1% p<0.001), and half as likely to be removed for death or clinical deterioration (9.2% vs 18.2% p=0.046). In multivariable models, posttransplantation survival was not associated with receipt of exception points, whereas risk of posttransplant mortality increased significantly with elevated serum total bilirubin level at transplantation. The three-year posttransplant patient survival was 78% in transplant recipients with metastatic NETs whose total bilirubin level at transplantation was ≤1.3 mg/dL, compared to 36% in those with total bilirubin >1.3mg/dL.

CONCLUSIONS

Serum total bilirubin may serve as a predictor of poor posttransplant survival in patients with metastatic NETs, and could help risk-stratify patients applying for MELD exception points.

Introduction

The role of liver transplantation in the management of patients with metastatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) is controversial. While several series have reported excellent outcomes in well-selected patients,1,2 others have reported less favorable results, with a posttransplant 5-year survival rate as low as 49-58% in transplant recipients in the United States.3,4 Use of liver transplantation as a treatment for patients with metastatic NETs is complicated by the fact that most of these patients have preserved liver synthetic function, and thus have low waitlist priority based on their Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score. For many patients with metastatic NETs, the only means to access an organ for transplantation is to receive a living donor transplant or to gain increased waitlist priority by receiving MELD exception points.

As there are no standardized criteria for awarding exception points to patients with metastatic NETs, transplant centers must apply for a “non-standardized” exception, which requires review and approval by a regional review board.5,6 Unlike patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), for whom the natural history of the disease without transplantation is known and the long-term posttransplant survival is well-documented as similar to other transplant patients,7–9 there are little data about posttransplantation outcomes among patients with metastatic NETs. Limited existing analyses of US transplant recipients with metastatic NETs do not account for the variable use of exception points.3,4

The role of exception points in the prioritization of patients with metastatic NETs became a topic of national discussion in 2009 with the transplantation of Steve Jobs.10 Given the limited posttransplantation survival outcomes data in the context of allocating a scarce resource, it is important to understand which factors are associated with posttransplantation prognosis, how frequently exception points are used, and how exception points impact outcomes in patients with metastatic NETs. We used United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) data to perform a detailed evaluation of all US patients waitlisted for liver transplantation since 2002, with a unique focus on the outcomes related to MELD exception points and other prognostic indicators. We used our findings to propose a new criterion for approving or rejecting requests for MELD exception points in patients with hepatic NET metastases.

Materials and Methods

UNOS Study Sample

We reviewed a UNOS Standard Transplant and Research (STAR) file to identify all patients waitlisted for liver transplantation for metastatic NETs. There is no specific UNOS code (in the dgn_tcr variable) for metastatic NET, so a single reviewer (Y.N.) reviewed all free text diagnosis categories (dgn_ostxt_tcr, dgn2_ostxt_tcr, and diag_ostxt) to identify all patients with a diagnosis of a metastatic NET. Patients were coded as having a neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to the liver if the tumor type was reported in UNOS as a carcinoid tumor, ACTH-producting tumor, gastrinoma, glucagonoma, insulinoma, islet cell tumor, VIPoma, or neuroendocrine tumor not otherwise specified. The cohort was restricted to adult patients ≥18 years of age who were on or added to the waitlist starting after initiation of MELD-based allocation on February 27, 2002. We included patients who were waitlisted for a combined liver-intestine transplant, as this could be potentially curative for patients with a small intestinal NET primary that has metastasized to the liver. Re-transplant candidates were excluded. Follow-up was until June 4, 2014.

Study outcomes

Waitlist and posttransplant outcomes were assessed. Waitlist outcomes included transplantation or waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration. Waitlist death was ascertained based on UNOS coding and/or Social Security Death Master File (SSDMF) data included in the UNOS dataset. Waitlist removal for clinical deterioration included patients removed for being “too sick to transplant” or “other” reasons with a confirmed SSDMF death date within 90 days of waitlist removal.11,12 Posttransplant death was coded based on UNOS posttransplant status, and/or confirmed SSDMF death date after transplantation.

Primary exposure and study covariates

The primary exposure was whether patients had ever received MELD exception points for NET (yes/no) based on UNOS coding. For patients who applied for a MELD exception prior to June 3, 2011, we reviewed the exception narrative in detail using a UNOS exception dataset based on available data. Covariates evaluated in multivariable posttransplant survival models included age at transplantation, sex, tumor type (coded as carcinoid, ACTH-producing, gastrinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma [MEN-1], insulinoma, islet cell, or neuroendocrine not other specified), transplant type (living or deceased donor), donor risk index (DRI),13 and total bilirubin, INR, and creatinine at transplant.

Statistical analyses

Chi-square tests and Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to evaluate baseline demographics and characteristics of patients with or without exception points. Chi-squared tests were used to evaluate the binary waitlist outcomes (transplantation and waitlist removal for death or clinical deterioration). Posttransplant Cox regression survival models were fit to compare posttransplant patient survival of transplant recipients with or without exception points. Univariable models were fit with the covariates referenced above, and were included in the final multivariable model if the covariate was associated with posttransplant survival in univariable models (p<0.1). The final multivariable model included all covariates independently associated with posttransplant survival and/or significant confounders (changed the hazard ratio of posttransplant survival by 10%). Posttransplant survival rates were compared to national rates of posttransplant patient survival during the study period, excluding multi-organ and re-transplant recipients. Survival rates were also compared using a serum bilirubin at transplantation cutoff of 1.3 mg/dL, as this value has previously been shown to predict survival in patients treated with Yttrium-90 radioembolization for metastatic NETs.14

Statistics were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 22 (IBM, Armonk, New York) and Stata 13.0 (College Station, Texas). This study received Institutional Review Board approval from the University of Pennsylvania.

Results

There were 230 adult patients waitlisted for liver transplantation for metastatic NET between February 27, 2002 and June 4, 2014 who met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 120 (49%) received MELD exception points while on the waitlist, while an additional 25 patients applied for exception points but were not approved. Reasons for denial of exception point application were not available. The demographics of patients with or without exception points were clinically similar, although the serum creatinine and MELD score at waitlisting were statistically different in the two groups (Table 1). The primary tumor etiology varied significantly, with a greater proportion of patients who received exception points being diagnosed with ACTH-producing tumor, glucagonoma, insulinoma, other islet cell tumor, and VIPoma than patients without exception points (Table 1). There was also regional variability in the proportion of patients who did and did not receive exception points. For example, 15/16 (93.8%) patients waitlisted with a metastatic NET in region 8 received exception points, while only 1/13 (7.7%) of patients waitlisted with a metastatic NET in region 9 received exception points (Table 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients waitlisted for liver transplantation for metastatic neuroendocrine tumors from 2/27/02-6/4/2014, n= 230.

| No exception pointsa (n=110) | Exception pointsa (n=120) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at listing, median (IQR) | 50 (41-57) | 49 (41-55) | 0.96 |

| Male sex, n (%) | 62 (56.4) | 67 (55.8) | 0.94 |

| Race/Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.19 | ||

| White | 92 (83.6) | 99 (82.5) | |

| Black | 8 (7.3) | 13 (10.8) | |

| Hispanic | 7 (6.4) | 6 (5.0) | |

| Asian | 3 (2.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Lab data at waitlisting, median (IQR) | |||

| MELDb | 8 (6-12) | 7 (6-9) | 0.01 |

| Total Bilirubin (mg/dL)c | 0.70 (0.48-1.33) | 0.6 (0.40-1.00) | 0.06 |

| INRd | 1.1 (1.0-1.2) | 1.0 (1.0-1.1) | 0.32 |

| Serum Creatinine (mg/dL)e | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | 0.01 |

| Tumor type, n (%) | 0.04 | ||

| Carcinoid | 47 (42.7) | 34 (28.3) | |

| ACTH-producing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Gastrinoma | 3 (2.7) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Glucagonoma | 1 (0.9) | 7 (5.8) | |

| Insulinoma | 1 (0.9) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Islet Cell | 8 (7.3) | 9 (7.5) | |

| VIPoma | 1 (0.9) | 4 (3.3) | |

| Neuroendocrine, not otherwise specified | 49 (44.5) | 58 (48.3) | |

| UNOS Region, n (%) | <0.001 | ||

| 1 | 7 (6.4) | 5 (4.2) | |

| 2 | 6 (5.5) | 9 (7.5) | |

| 3 | 9 (8.2) | 13 (10.8) | |

| 4 | 3 (2.7) | 4 (3.3) | |

| 5 | 23 (20.9) | 18 (15.0) | |

| 6 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| 7 | 31 (28.2) | 18 (15.0) | |

| 8 | 1 (0.9) | 15 (12.5) | |

| 9 | 12 (10.9) | 1 (0.8) | |

| 10 | 13 (11.8) | 16 (13.3) | |

| 11 | 5 (4.5) | 21 (17.5) |

No exception points category includes patients who never applied for a MELD exception or patients who applied and were denied. Exception points category includes all patients with at least one MELD exception application approved.

Missing data for 15 (13.6%) patients with no exception points and 5 (4.2%) patients with exception points, who were listed before MELD era.

Missing data for 12 (10.9%) patients with no exception points and 1 (0.8%) patients with exception points, who were listed before MELD era.

Missing data for 12 (10.9%) patients with no exception points and 1 (0.8%) patients with exception points, who were listed before MELD era.

Missing data for 12 (10.9%) patients with no exception points and 1 (0.8%) patients with exception points, who were listed before MELD era.

Waitlist outcomes were significantly associated with receipt of exception points—patients who received exception points were nearly twice as likely to be transplanted, and half as likely to be removed from the waitlist for death or clinical deterioration (Figure 1). Notably, there were 14 patients waitlisted for a combined liver-intestine transplant, of whom only 3 (21.4%) received exception points. As above, reasons for denial of exception point application were not available. All 14 of these waitlist candidates were ultimately transplanted.

Figure 1.

Waitlist outcomes of patients waitlisted for liver transplantation for neuroendocrine tumor metastatic to the liver from 2/27/02-6/4/2014.

Transplant recipients with exception points had significantly longer waiting times from initial listing to transplantation (median: 125 vs. 47 days, p=0.002). However, due to lag time between listing and receipt of exception points, which occurred at median of 27 days (interquartile range: 8-119 days), waiting from receipt of exception points to transplantation was 65 days (IQR 38-136), which did not differ significantly from time to transplantation in the non-exception cohort (p=0.35).

Among the six UNOS regions with at least 10 patients receiving exception points for metastatic NETs (Table 1), there were significant differences in the median time from receiving exception points to transplantation by UNOS region (p=0.02). Specifically, the median waiting time was less than two months in regions 3, 8, 10, and 11, compared with three and four months in regions 5 and 7, respectively. The number of exception points awarded was also significantly different among these six regions (p<0.001), ranging from a median of 33 (IQR: 24-35) in region 5 to a median of 22 in regions 3 (IQR: 20-24), 10 (IQR: 22-24), and 11 (IQR: 22-22). The corresponding increase from a patient's laboratory MELD score to the exception MELD score differed significantly across these six region (p=0.01), and was highest in region 5 (median difference between laboratory MELD and exception MELD scores: 19, IQR: 15-27), and lowest in region 3 (median difference: 12, IQR: 8-16).

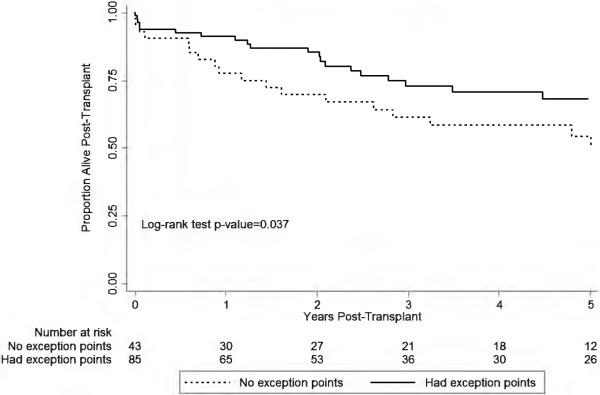

Posttransplant survival

In univariable models, increased age at transplantation, bilirubin at transplantation, and receipt of exception points were significantly associated with posttransplant mortality. However, in multivariable models, only bilirubin was associated with posttransplant mortality, with increased bilirubin at transplantation being associated with increased posttransplant mortality. Exception point status was not associated with posttransplant survival in multivariable models that included serum bilirubin at transplantation.

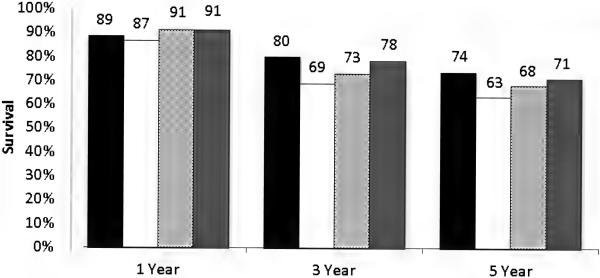

The 1-, 3, and 5-year posttransplant patient survival rates (95% confidence intervals) among all transplant recipients with metastatic NETs, regardless of exception points, were 87% (79-92%), 69% (59-77%), and 63% (53-72%), respectively. These rates were significantly lower than national posttransplant survival rates for all first-time transplant recipients, with the 3- and 5-year posttransplant survival rates of transplant recipients with metastatic NETs being 11% lower in absolute terms than survival rates among all US transplant recipients during the study period (80% and 74% 3- and 5-year survival, respectively, for all transplant recipients; Figure 3). Even when restricted to metastatic NET transplant recipients with exception points, the 3- and 5-year survival rates were still lower than national rates (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

One-, three-, and five-year survival after liver transplantation for all transplant recipients, NET transplant recipients who received MELD exception points, all NET transplant recipients regardless of exception point status, and NET transplant recipients with total bilirubin ≤1.3 at transplant.

UNOS data on cancer recurrence are incomplete and were captured only among those with graft failure or death. Of 120 patients who received transplant for metastatic NETs, 46 died posttransplant, with cause of death identified in 38. Of those in whom cause of death was defined, 20/38 (52.6%) died of recurrent NET.

Dichotomous survival analysis according to bilirubin at transplantation (bilirubin ≤1.3 mg/dL versus bilirubin >1.3 mg/dL) revealed a greater divergence in survival outcomes (p=0.005; Figure 2b), consistent with prior research.14 The 1- and 3-year posttransplant survival rates for transplant recipients with metastatic NETs and a bilirubin ≤1.3 mg/dL at transplantation was 70.8% (95% CI: 49.7-84.3%) and 36.4% (17.1-56.1%), compared to 91.3% (83.3-95.6%) and 78.3% (67.6-85.8%) in those with bilirubin ≤1.3 mg/dL at transplantation. The posttransplant survival of those with a bilirubin ≤1.3 mg/dL at transplantation closely matched the national posttransplant survival rates for all first-time transplant recipients (Figure 3). All of the survival analyses were unchanged with exclusion of the combined liver-intestine recipients (data not shown)

Figure 2.

(A) Posttransplant patient survival among transplant recipients with metastatic NETs with vs. without exception points. (B) Posttransplant patient survival among transplant recipients with metastatic NETs stratified by bilirubin at transplant. *Legends and titles embedded in Stata

Discussion

This analysis of UNOS data on all patients listed for liver transplant for NET metastases in the United States since 2002 demonstrates that liver transplant recipients with NET metastases, with or without MELD exception points, had lower posttransplant survival than all other first-time transplant recipients. In unadjusted models, patients who received MELD exception points appeared to have significantly improved posttransplantation survival compared to patients with no exception points, but this effect was lost when adjusting for total bilirubin. As such, the current unstandardized process of assigning exception points to patients with hepatic NET metastases may serve to increase waitlist priority for a subset of patients whose posttransplant survival outcomes are inferior to the average waitlist patient.

There are no specific data to guide regional review board (RRBs) when reviewing nonstandardized exception applications for patients with hepatic NET metastases. The absence of a consensus philosophy among transplant centers regarding the role of transplantation in NET metastases is evidenced by markedly variable regional utilization of exception points: 15/16 (93/8%) of patients transplanted for NET metastases received exception points in Region 8, while 1/13 (7.7%) received exception points in Region 9. The regional variability in the utilization of MELD exception points for patients with metastatic NETs is consistent with published literature that has demonstrated among-center variability in the application for, and subsequent approval of, exception points both within and across regions.15

For most indications, liver transplantation attempts cure of disease, whether decompensated cirrhosis or hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). In fact, criteria guiding MELD exceptions granted to patients with HCC promote transplantation only for those with high likelihood of cure and low risk of recurrence.16 In patients with metastatic NETs, in contrast, the survival benefit of transplantation remains unclear. Though data regarding recurrence of NET are incomplete, in our study, over half of posttransplantation deaths with reported causes were due to recurrent metastatic NET. Under an idealized scenario whereby no other transplanted patients had recurrent NET, the risk of recurrence or death from NET would be 15.6% (20/128), more than double the reported risk of recurrence or death from HCC.17 Under a more plausible scenario in which some patients had recurrent NET that did not lead to death, and was therefore not represented in the UNOS database, the risk of recurrence or death from NET would be even higher. These data suggest that unlike in the case of HCC, for which transplant is largely curative, transplant is not curative for a sizable portion of patients with metastatic NETs. In these patients, scarce organs are utilized for a palliative process.

Prospective data should be collected to further define the role of transplantation in patients with metastatic NETs. These retrospective data highlight the variable nature of data captured within UNOS on waitlisted patients with metastatic NETs. Our analysis, which accounts for waiting time and use of exception points, suggests that bilirubin may be a significant factor associated with posttransplant survival. However, this finding requires external validation, based ideally from a prospective registry. In the future, identification of laboratory values (such as serum bilirubin) and/or biomarkers that predict recurrence of metastatic NETs posttransplantation will be helpful in order to risk stratify patients for transplantation and optimally allocate exception points (akin to the role of Milan criteria in HCC).

If transplantation centers make the decision to place patients with metastatic NETs on the UNOS waitlist – as is currently accepted – consideration should be made to restrict transplantation to those with acceptable posttransplant outcomes. Future external validation is needed to determine whether exception points be restricted to those with a bilirubin ≤1.3 mg/dL in order to maximize outcomes in this cohort for whom transplantation remains controversial. In order to obtain granular data that can be used for clinical and research purposes, we would recommend that UNOS adopt a formal exception point submission form for patients with metastatic NETs, similar to those used for HCC and hepatopulmonary syndrome. Such forms should include, but not necessarily be limited to, specific questions on: 1) tumor subtype; 2) number of tumors in the liver; 3) presence of extra-hepatic metastatic disease; 4) previous treatments; and 5) location and burden of primary tumor. A more formalized approach to data submission is needed in order to properly examine the role of transplantation for metastatic NETs and risk stratification of patients for transplantation. Furthermore, future collaborations with the North American NeuroEndocrine Tumor Society should be considered in order to evaluate multi-disciplinary approaches to treating patients with metastatic NETs, as well as to evaluate outcome in transplant and non-transplant patients. Finally, although challenging to implement, consideration should be given to a prospective randomized trial that compares interventional radiology versus oncologic therapies versus transplantation for the treatment of metastatic NETs.

Any consideration of modifying or creating policies for awarding exception points for patients with metastatic NETs needs to account for the potential role of multi-visceral transplantation (MVT) for these patients. MVT offers the potential benefit of removal of complete tumor burden in order to minimize risk of recurrent NETs. This study cohort included 14 patients listed for a combined liver-intestine transplant, of whom only three received exception points. There is a limited sample size of these recipients, but there were no statistically significant differences in posttransplant outcomes in liver-alone versus liver-intestine candidates with metastatic NETs. Given the potential benefit of MVT, future policies guiding MELD exception points for patients with NETs should ensure sufficient access to both liver and intestines for centers that choose to perform MVTs, while also collecting detailed data in order to perform comparisons of posttransplant outcomes in liver-alone vs MVT transplant recipient.

Our study has limitations. Because NETs are rare conditions, the population of patients that we were able to analyze is small. Although we controlled for several patient factors in our analysis of posttransplant survival, other factors specific to NETs, such as burden of disease and spectrum of extra-hepatic metastases, could not be accounted for due to limitations of the data available in the exception narratives. The limited exception narrative data also provides insufficient characterization of tumor histology and extent of spread, and more granular data are needed to study this in detail. We used a total bilirubin level greater than 1.3 mg/dL at transplantation as a potential cutoff to identify patients with worse outcomes based on a lack of literature in transplant recipients with metastatic NETs, as well as published literature of patients undergoing Yttrium-90 treatment for metastatic NETS.14,18 However, as <25% of the transplant cohort had a bilirubin above this level, we were unable to sufficiently identify other potential cutpoints, which should be done in future work. Nevertheless, this analysis is the first to evaluate bilirubin as a prognostic factor among transplant recipients with metastatic NETs, as the largest previous analysis of UNOS transplant data focused on waiting time as a factor associated with posttransplant survival, and did not account for bilirubin levels.3

In conclusion, we demonstrate that while waitlisting and transplantation among patients with NETs metastatic to the liver is uncommon, among those who are waitlisted, nearly 50% apply for and receive exception points. Though transplantation for metastatic NETs remains controversial, these data suggest that increased prioritization through exception points should be limited to a subset of those currently on the waitlist in order to increase the likelihood of transplantation among those with acceptable posttransplant outcomes.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH K08 DK098272 (David Goldberg). This work was also supported in part by Health Resources and Services Administration contract 234-2005-37011C. The content is the responsibility of the authors alone and does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of Health and Human Services, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

• Yael Nobel participated in research design, data analysis, and writing of the manuscript. David Goldberg participated in research design, data analysis, and writing and editing of the manuscript.

ABBREVIATIONS

- HCC

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- NET

Neuroendocrine tumor

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- UNOS

United Network for Organ Sharing

Footnotes

Disclosure:

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Le Treut YP, Grégoire E, Klempnauer J, et al. Liver transplantation for neuroendocrine tumors in Europe-results and trends in patient selection: a 213-case European liver transplant registry study. Ann Surg. 2013;257(5):807–815. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828ee17c. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828ee17c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fan ST, Le Treut YP, Mazzaferro V, et al. Liver transplantation for neuroendocrine tumour liver metastases. HPB. 2014 doi: 10.1111/hpb.12308. n/a-n/a. doi:10.1111/hpb.12308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gedaly R, Daily MF, Davenport D, et al. Liver Transplantation for the Treatment of Liver Metastases From Neuroendocrine Tumors: An Analysis of the UNOS Database. Arch Surg. 2011;146(8):953–958. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nguyen NTT, Harring TR, Goss JA, O'Mahony CA. Neuroendocrine Liver Metastases and Orthotopic Liver Transplantation: The US Experience. Int J Hepatol. 2011;2011:1–7. doi: 10.4061/2011/742890. doi:10.4061/2011/742890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Health Resources and Services Administration Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network Policies and Bylaws Policy. 2013;8:1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goldberg DS, Fallon MB. Model for End-Stage Liver Disease–Based Organ Allocation: Managing the Exceptions to the Rules. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11(5):452–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.014. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao FY, Ferrell L, Bass NM, et al. Liver transplantation for hepatocellular carcinoma: expansion of the tumor size limits does not adversely impact survival. Hepatology. 2001;33(6):1394–1403. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. doi:10.1053/jhep.2001.24563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mazzaferro V, Regalia E, Doci R, et al. Liver transplantation for the treatment of small hepatocellular carcinomas in patients with cirrhosis. [October 8, 2014];N Engl J Med. 1996 334(11):693–699. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199603143341104. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/nejm199603143341104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mazzaferro V, Llovet JM, Miceli R, et al. Predicting survival after liver transplantation in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma beyond the Milan criteria: a retrospective, exploratory analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10(1):35–43. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70284-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grady D, Meier B. A Transplant That Is Raising Many Questions. The New York Times; http://www.nytimes.com/2009/06/23/business/23liver.html?_r=1&adxnnl=1&pagewanted=all&adxnnlx=1411048884-Sv9SQvWJ1y4EzJnaQvuX3w. Published June 23, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberg DS, French B, Abt P, Feng S, Cameron AM. Increasing disparity in waitlist mortality rates with increased MELD scores for candidates with eversus without hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transplant. 2012;18(4):434–443. doi: 10.1002/lt.23394. doi:10.1002/lt.23394.Increasing. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moylan CA, Brady CW, Johnson JL, Smith AD, Tuttle-newhall JE, Muir AJ. Disparities in Liver Transplantation Before and After Introduction of the MELD Score. JAMA. 2008;300(20):2371–2378. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(4):783–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. doi:10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dunfee BL, Riaz A, Lewandowski RJ, et al. Yttrium-90 radioembolization for liver malignancies: prognostic factors associated with survival. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2010;21(1):90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jvir.2009.09.011. doi:10.1016/j.jvir.2009.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldberg DS, Makar G, Bittermann T, French B. Center variation in the use of nonstandardized model for end-stage liver disease exception points. Liver Transplant. 2013;19(12):1330–1342. doi: 10.1002/lt.23732. doi:10.1002/lt.23732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mazzaferro V, Bhoori S, Sposito C, et al. Milan Criteria in Liver Transplantation for Hepatocellular Carcinoma: An Evidence-Based Analysis of 15 Years of Experience. Liver Transplant. 2011;17:S44–S57. doi: 10.1002/lt.22365. doi:10.1002/lt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samoylova ML, Dodge JL, Vittinghoff E, Yao FY, Roberts JP. Validating Posttransplant Hepatocellular Carcinoma Recurrence Data in the United Network for Organ Sharing Database. Liver Transplant. 2013;19:1318–1323. doi: 10.1002/lt.23735. doi:10.1002/lt. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Memon K, Lewandowski RJ, Mulcahy MF, et al. Radioembolization for neuroendocrine liver metastases: safety, imaging, and long-term outcomes. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2012;83(3):887–894. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.041. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2011.07.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]