Abstract

Trichosporonosis is an emerging infection predominantly caused by Trichosporon asahii which is a ubiquitous and exclusively anamorphic yeast. T. asahii urinary tract infection is rare and remains scantily reported.

T. asahii was isolated from urine of two immunocompetent patients who were receiving in-patient treatment for multiple comorbidities. T. asahii was identified phenotypically by a combination of manual and automated systems. Antifungal susceptibility done by E-test revealed multiresistance with preserved susceptibility to voriconazole.

The ubiquity and biofilm formationposes difficulty in establishing pathogenicity and delineating environmental or nosocomial infections. Risk factors such as prolonged multiple antimicrobials, indwelling catheter and comorbidities such as anemia and hypoalbuminemia may be contributory to the establishment of a nosocomial opportunistic T. asahii infection. Dedicated efforts targeted at infection control are needed to optimize management and control of Trichosporon infections.

Keywords: Trichosporon asahii, Antifungal multiresistance, Nosocomial opportunistic infection

Introduction

Trichosporonosis is an emerging infection predominantly caused by Trichosporon asahii. Trichosporon (Beigel, 1985) species are ubiquitous, exclusively anamorphic, yeast like fungi belonging to Trichosporonaceae. Trichosporon is implicated in superficial and mucosal infections, however, systemic infections are known in immunocompromised, cancer, burns, transplant patients as well as patients on steroids, peritoneal dialysis, prolonged mechanical ventilation and those undergoing prosthetic valve surgeries.1, 2 Alimentary tract, respiratory tract, broken skin and mucosa are possible portals of entry. Persistent and disseminated infections have poor prognosis. Fatal outbreak in neonates and breakthrough trichosporonosis under antifungal therapy has been reported.3, 4T. asahii urinary tract infection (UTI) is scantily reported.5, 6 We report two cases of T. asahii UTI in immunocompetent severely ill patients in a tertiary care set up.

Case 1

T. asahii was isolated from urine on two occasions from a 46 year old male patient with multiple pressure sores over sacrum and both hips. He was offered skin flap and tissue expansion. There was a past history of traumatic quadriplegia and multiple fractures following fall from height. The patient was having persistent fever, hypoalbuminemia, microcytic hypochromic anemia, persistent leukocytosis, pyuria and deteriorated further. During the course of stay in the hospital, the patient had an indwelling catheter and was aggressively managed with meropenem, levofloxacin, Co-Amoxiclav, tobramycin and linezolid in appropriate dosages along with high protein diet, albumin infusions, antacids, multivitamins, enoxaparin and whole blood transfusion.

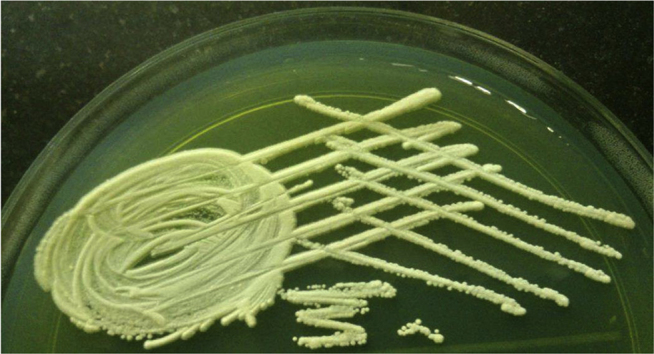

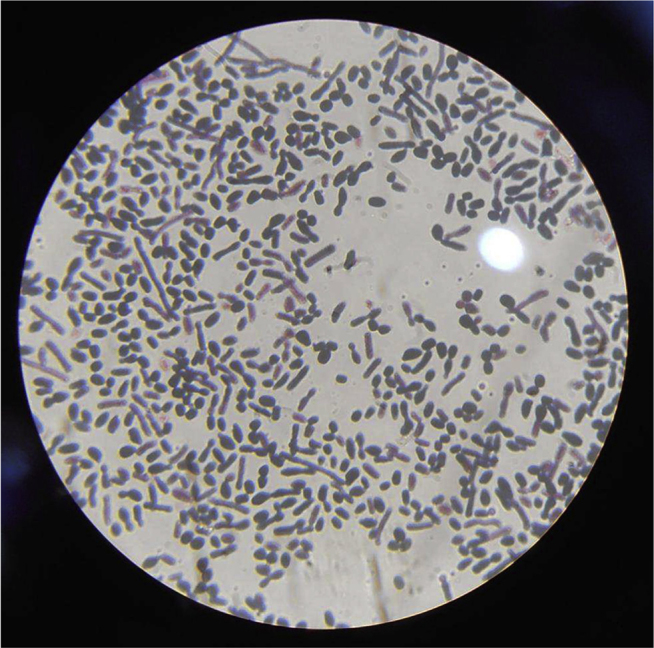

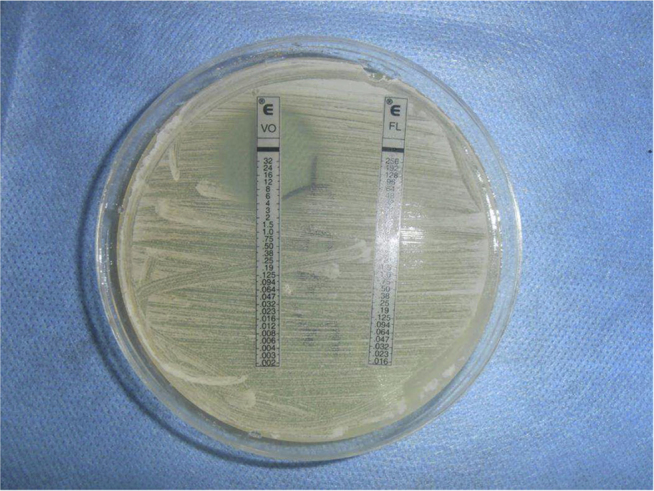

The first sample was collected by clamping the catheter while the second after catheter removal. On both occasions, routine microscopy revealed pus cells and yeast cells without budding. Urine sample inoculated with standard loop on cysteine lactose electrolyte deficient agar (HiMedia Laboratories, India) revealed significant growth of dry creamy white colonies after overnight incubation (Fig. 1). Gram stain and lactophenol cotton blue mount revealed septate hyaline hyphae with arthroconidia and few budding yeast cells (Fig. 2). After subculture, the yeast was identified to be T. asahii by morphology on cornmeal agar, Gram stain, hydrolysis of urea, assimilation of carbon/nitrogen compounds and confirmation by VITEK 2 compact automated system (bioMérieux, France).5 Subcultures on Sabouraud's dextrose agar at both 22 °C and 37 °C revealed curdy white growth which turned cottony on subsequent incubation. Antifungal susceptibility was tested by E-test (AB BIODISK, Sweden) for fluconazole, itraconazole, voriconazole, Amphotericin B and anidulafungin (Fig. 3).7 Minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) for voriconazole was 3 μg/ml and multiresistance was observed. Prompt treatment with voriconazole and management for comorbidities lead to subsequently sterile urine cultures.

Fig. 1.

Trichosporon asahii on CLED agar after overnight incubation.

Fig. 2.

Gram stain of Trichosporon asahii showing budding yeasts and barrel shaped arthroconidia.

Fig. 3.

Antifungal susceptibility of Trichosporon asahii through E-test showing an MIC of 3 μg/ml.

Case 2

T. asahii was isolated twice from urine samples of an 86 year old male patient admitted for generalized tonic clonic seizures, associated loss of consciousness and sphincter incontinence. The patient had comorbid hypothyroidism, hypertension, dyslipidemia, cholelithiasis, glaucoma in left eye and sinus bradycardia with first degree atrioventricular block. Pus cells, occasional yeast cells without budding in urine were seen. Creatinine levels were high. Leukocyte counts and other investigations were normal. The patient was being managed by clindamycin, cefoperazone, phenytoin sodium, levothyroxine, amlodipine, aspirin and antacids. The patient had a condom catheter throughout the course of his stay in the hospital. Pure significant creamy white colonies revealed hyphae, yeast cells and arthroconidia on staining. It was identified as T. asahii by urea hydrolysis, carbohydrate assimilation and confirmation by automated system. The patient was managed with voriconazole on similar lines as the first case and treatment was confirmed by subsequent sterile urine cultures.

Discussion

Trichosporon has been isolated from soil, outdoor and indoor environmental sources including hospitals. They may constitute normal flora of the human skin, vagina, respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts.8 Virulence factors for Trichosporonosis include glucuronoxylomannan in cell wall, proteases, phospholipases and the ability to form biofilms. They form true mycelia, blastoconidia and arthroconidia. Virulence factors and morphological structures may be exhibited differently in different species. Their ubiquity and biofilm formation may create confusion between colonized and truly infected patients. Invasive Trichosporonosis may be confused with disseminated candidiasis. Although invasive Trichosporonosis has been studied, however, there are no specific guidelines for clinical interpretation of Trichosporon recovery in urine.9 Azotemia and aggravation of renal dysfunction leading to renal failure may rarely occur.5

Trichosporon infections present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. They are likely to surpass routine laboratory identification. Micromorphology (hyphae, pseudohyphae, arthroconidia, blastoconidia), carbon source utilization (nonfermentative) and urease positivity are contributory. Grocott's stain and lactophenol cotton blue mount along with hematoxylin-eosin, colloidal iron and periodic acid methenamine silver stains for tissues may discern morphology.9 Production of virulence factors such as protease, phospholipase and hemolysin may be assessed by halo formation on corresponding agar plates. Diazonium blue B reaction may be elicited. Biofilm formation on polystyrene surfaces may be detected through a formazan salt reduction assay. Comprehensive diagnosis has been simplified by the advent of automated systems and molecular technology. Automation based on phenotypic properties has facilitated compaction, standardization and quality control, although has certain limitations. Semi-automated systems such as API 20C AUX, ID 32C (both bioMérieux, France) and RapID Yeast Plus system (Innovative Diagnostic System, USA) may require macro and micromorphological observation of colonies.9 Automated systems such as VITEK 2 compact (bioMérieux, France) and Microscan Walkaway (Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics, USA) may have limitations at species level identification. Both pan species (internal transcribed spacers ITS1 and ITS2 of rDNA, D1/D2 domain of 26S rRNA, intergenic spacer IGS1, small subunit SSU, mitochondrial cytochrome b) and species specific targets may be amplified for genotypic identification. The sensitivity of various molecular methods such as polymerase chain reaction, rolling circle amplification, three locus identification, reverse line blot hybridization, oligonucleotide array hybridization, DNA microarray and DNA sequencing remains variable.10 Simultaneous amplification of two targets is likely to improve identification and study of phylogenetic relationships of Trichosporon strains. Flow cytometry and proteomics based technologies have also been tried.9 In the absence of antifungal susceptibility guidelines/data on Trichosporon, guidelines for Candida are extrapolated by some microbiologists.9, 11 Azoles such as voriconazole, posaconazole and fluconazole may be effective.1, 5, 6 Combined regimens such as caspofungin and Amphotericin B may also be effective, however individual drugs may be ineffective.11, 12

Repeated isolation of T. asahii, associated pyuria and swift response to antifungal therapy helped delineate T. asahii UTI. Risk factors such as use of prolonged multiple antimicrobials, indwelling catheter and comorbidities such as anemia and hypoalbuminemia in the cases reported here may be contributory to the establishment of T. asahii infection. The multiplicity and long duration of comorbidities makes it difficult to arrive at the causation of Trichosporon transmission in these cases. The infection is most likely to be nosocomial.6, 8 Although Trichosporon is ubiquitous and colonizes many areas, it is a known opportunistic pathogen causing emergent and invasive infections in tertiary care hospitals worldwide.9Trichosporon colonization in the first patient may be due to colonization and biofilm formation on indwelling catheter which may have furthered the infection of urinary tract.6, 10 Non culture based methods have been suggested to differentiate between colonized and infected patients. Prolonged undiagnosed or untreated infections can lead to disseminated Trichosporonosis which may be indicated by repeatedly positive urine cultures. Trichosporon biofilms may be resistant to all antifungals and up to 16,000 times more resistant to voriconazole than planktonic cells.8, 9

Conclusion

A high index of clinical and microbiological suspicion is required for optimal diagnosis of Trichosporon infections. Attributing pathogenicity after diagnosis may be difficult in the presence of comorbidities with variable clinical response and administration of multiple antimicrobials. Dedicated efforts by clinicians and microbiologists targeted at infection control and further research are needed to optimize management and control of Trichosporon infections.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Dua V., Yadav S.P., Oberoi J., Sachdeva A. Successful treatment of Trichosporon asahii infection with voriconazole after bone marrow transplant. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35(3):237–238. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e318279b21b. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23211690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cawley M.J., Braxton G.R., Haith L.R., Reilly K.J., Guilday R.E., Patton M.L. Trichosporon beigelii infection: experience in a regional burn center. Burns. 2000 Aug;26(5):483–486. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00181-3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10812273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vashishtha V.M., Mittal A., Garg A. A fatal outbreak of Trichosporon asahii sepsis in a neonatal intensive care unit. Indian Pediatr. 2012 Sep;49(9):745–747. doi: 10.1007/s13312-012-0137-y. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23024079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bayramoglu G., Sonmez M., Tosun I., Aydin K., Aydin F. Breakthrough Trichosporon asahii fungemia in neutropenic patient with acute leukemia while receiving caspofungin. Infection. 2008:3668–3670. doi: 10.1007/s15010-007-6278-6. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17882360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sood S., Pathak D., Sharma R., Rishi S. Urinary tract infection by Trichosporon asahii. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2006 Oct;24(4):294–296. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.29392. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17185852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kumar S., Bandyopadhyay M., Mondal S., Pal N. A rare case of nosocomial urinary tract infection due to Trichosporon asahii. J Glob Infect Dis. 2011 Jul-Sep;3(3):309–310. doi: 10.4103/0974-777X.83541. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3162825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arikan S., Hasçelik G. Comparison of NCCLS microdilution method and Etest in antifungal susceptibility testing of clinical Trichosporon asahii isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2002 Jun;43(2):107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(02)00376-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun W., Su J., Xu S., Yan D. Trichosporon asahii causing nosocomial urinary tract infections in intensive care unit patients: genotypes, virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility testing. J Med Microbiol. 2012 Dec;61(Pt 12):1750–1757. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.049817-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22956749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colombo A.L., Padovan A.C.B., Chaves G.M. Current knowledge of Trichosporon spp. and Trichosporonosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24(4):682–700. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00003-11. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3194827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiao M., Guo L.N., Kong F. Practical identification of eight medically important Trichosporon species by reverse line blot hybridization (RLB) assay and rolling circle amplification (RCA) Med Mycol. 2013;51(3):300–308. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2012.723223. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23186014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Walsh T.J., Melcher G.P., Rinaldi M.G. Trichosporon beigelii: an emerging pathogen resistant to amphotericin B. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1616–1622. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.7.1616-1622.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li H., Lu Q., Wan Z., Zhang J. In vitro combined activity of amphotericin B, caspofungin and voriconazole against clinical isolates of Trichosporon asahii. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010 Jun;35(6):550–552. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2010.01.013. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20202797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]