Abstract

As urogenital tuberculosis (UGTB) has no specific clinical features, it is often overlooked. To identify some of the reasons for misdiagnosing UGTB we performed a systematic review. We searched in Medline/PubMed papers with keywords ‘urogenital tuberculosis, rare’ and ‘urogenital tuberculosis, unusual’. ‘Urogenital tuberculosis, rare’ presented 230 articles and ‘urogenital tuberculosis, unusual’ presented 81 articles only, a total of 311 papers. A total of 34 papers were duplicated and so were excluded from the review. In addition, we excluded from the analysis 33 papers on epidemiological studies and literature reviews, papers describing non-TB cases and cases of TB another than urogenital organs (48 articles), cases of congenital TB (three articles), UGTB as a case of concomitant disease (16 articles), and UGTB as a complication of BCG-therapy (eight articles). We also excluded 22 articles dedicated to complications of the therapy, which made a total of 164 articles. Among the remaining 147 articles we selected 43 which described really unusual, difficult to diagnose cases. We also included in our review a WHO report from 2014, and one scientific monograph on TB urology. The most frequent reasons for delayed diagnosis were absence typical clinical features of UGTB, and the tendency of UGTB to hide behind the mask of another disease. We can conclude that actually UGTB is not rare disease, but it is often an overlooked disease. The main reasons for delayed diagnosis are vague, atypical clinical features and a low index of suspicion.

Keywords: bladder, cancer, diagnosis, prostate, tuberculosis, urogenital

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the world’s deadliest communicable diseases. In 2013, an estimated 9.0 million people developed TB and 1.5 million died from the disease, 360,000 of whom were HIV-positive. About 60% of TB cases and deaths occur among men, but the burden of disease among women is also high. In 2013, an estimated 510,000 women died as a result of TB, more than one-third of whom were HIV-positive. There were 80,000 deaths from TB among HIV-negative children in the same year. An estimated 1.1 million (13%) of the 9 million people who developed TB in 2013 were HIV-positive [WHO, 2014].

As such, the World Health Organization (WHO) recognized TB as a global problem, but meant TB as a whole, mostly pulmonary TB (PTB). Urogenital TB (UGTB) did not receive the attention of the WHO, although UGTB is the second most common form of TB in countries with a severe epidemic situation and the third most common form in regions with a low incidence of TB. A total of 28% of patients with PTB had prostate TB; 77% of men who died from tuberculosis of all localizations had prostate tuberculosis too, which had mostly been overlooked during their lifetime. Genital TB, both male and female, is one of the main causes of infertility [Kulchavenya and Krasnov, 2010; Kulchavenya, 2014]. The clinical features of UGTB are atypical, flexible and variable; UGTB mimics numerous other diseases, which results in delayed diagnosis.

The problem of UGTB reflects many contradictions: from terms and classification to therapy and management. Nevertheless we need to overcome these problems to achieve the best understanding of this eternally enigmatic and potentially fatally dangerous disease.

Material and methods

For our systematic review we have searched Medline/PubMed papers with the keywords ‘urogenital tuberculosis, rare’ and ‘urogenital tuberculosis, unusual’: ‘urogenital tuberculosis, rare’ presented 230 articles and ‘urogenital tuberculosis, unusual’ presented 81 articles only: a total of 311 papers. We excluded 34 papers from the review as they were duplicates. Also we excluded from the analysis 33 papers on epidemiological studies and literature reviews, papers describing non-TB cases and cases of TB another than of the urogenital organs (48 articles), cases of congenital TB (three articles), UGTB as a case of concomitant disease (16 articles), and UGTB as a complication of BCG-therapy (eight articles). We also excluded 22 articles dedicated to complications of therapy, leaving a total of 164 articles. Among the remaining 147 articles we selected 43 which described really unusual, difficult to diagnose cases. In addition, we included in our review a WHO report from 2014, and one scientific monograph on TB urology.

Results

We had to critically evaluate some papers, to determine whether in fact the authors reported usual, typical cases of UGTB, but because they were not familiar with this disease and had not enough experience, they believed it was a rare case.

Urogenital involvement in PTB patients

Urogenital involvement occurring alongside PTB, which may be common, especially in patients with disseminated TB, may be estimated incorrectly. Generalized TB may manifest first as UGTB. This scenario was described by Colbert and colleagues [Colbert et al. 2012]. The patient presented with vomiting and renal colic. Imaging studies showed nodules throughout the lungs, retroperitoneum, abdominal viscera, and kidneys. Asymmetrical hydronephrosis was found on renal imaging.

Vulval TB in a patient with PTB for a long time was diagnosed as a sexually transmitted disease [Nanjappa et al. 2012], but in a 26-year-old Indian woman with lymphatic and PTB, localized papulonecrotic tuberculid of the vulva was diagnosed in time, due to high index of suspicion [Wong et al. 2011].

UGTB and renal and urinary system cancer

Androulaki and colleagues reported the case of an inflammatory pseudotumor associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) infection, which was initially mistaken for a renal malignancy both in clinical and radiological settings [Androulaki et al. 2008].

Bouchikhi and colleagues reported a patient who presented with left back pain associated with urinary frequency and a few macroscopic episodes of hematuria for the past 6 months [Bouchikhi et al. 2013a]. Helical computed tomography revealed a left hydronephrosis and hydroureter secondary to focal wall thickening of the left lumbar ureter. On this basis, the authors had diagnosed a ureteral tumor. However, a clinical examination showed irritative voiding symptoms as well as epididymitis associated with prostate infection suggesting Mtb assessment of the patient’s urine of which the results proved strongly positive [Bouchikhi et al. 2013b]. This case is an example of incorrect interpretation of clinical findings: the authors revealed generalized involvement of urogenital system organs (bladder, kidney, epididymis), but described this as isolated ureteral TB. Again, accordingly to new classification, ureteral TB is a complicated of kidney TB (KTB) and cannot be if the kidneys are healthy.

UGTB and cancer of male genitals

UGTB is very difficult to differentially diagnose, and cancer is one of the most common causes of erroneous diagnosis. Isolated tuberculous epididymitis (ITE), defined as tuberculous epididymitis without clinical evidence of either renal or prostate involvement, is not a rare entity among UGTB, but it is extremely difficult to diagnose early on. We have found isolated epididymitis in 21.5% [Kulchavenya and Krasnov, 2010]. Kho and Chan reported a 20-year-old man who presented with a slow-growing painless scrotal tumor for 2 months, with the initial workup suspicious for a right paratesticular tumor [Kho and Chan, 2012]. Surgical resection of the tumor was therefore scheduled. However, severe pain and redness over the patient’s right hemiscrotum were noted on the day of surgery. A repeat scrotal ultrasound revealed findings suggesting a chronic inflammatory process rather than a malignancy. Frozen section of the lesion confirmed the ultrasonographic findings, and the pathology established the diagnosis of ITE [Kho and Chan, 2012].

Isolated tuberculous epididymo-orchitis may closely mimic testicular tumor particularly in patients with no history of systemic TB. A 44-year-old man presented with 4-month history of left scrotal mass and had a left orchidectomy following a presumptive diagnosis of testicular tumor. Histopathological diagnosis of testicular tuberculosis was subsequently made [Badmos, 2012]. TB orchiepididymitis, primarily misdiagnosed as scrotal tumor, has also been observed by Lakmichi et al. [Lakmichi et al. 2011].

In the report of Yu-Hung and colleagues [Yu-Hung et al. 2009] the patient presented with a scrotal mass 5 months after prostate biopsy; it was diagnosed as a tumor and managed with unilateral simple orchiepidymectomy. Histology revealed TB.

UGTB and cancer of the female genitals

Female genial tuberculosis (FGTB) may also be a reason for erroneous diagnosis of cancer. Sabita and colleagues reported a rare case of isolated cervical TB which mimicked carcinoma of the cervix [Sabita et al. 2013]. A 24-year-old woman presented with secondary amenorrhea and postcoital bleeding which were present for 1 year. The speculum examination revealed a friable cervix which bled on touch. Although the clinical history and the examination findings were suggestive of a cervical malignancy, the histopathological examination revealed a granulomatous TB inflammation.

Jaiprakash and colleagues emphasized that in countries like India, where carcinoma of the cervix is very common, cervical TB may easily be mistaken clinically for malignancy [Jaiprakash et al. 2013]. They reported a case of tuberculosis cervicitis (secondary to POTB) in a postmenopausal woman, who presented with a complaint of discharge per vaginum for a short duration. Per speculum examination showed an ulcerated lesion over the anterior lip of the cervix, clinically suggestive of malignancy. However, a Papanicolaou-smear showed features suggestive of TB which was confirmed by biopsy.

Massive uterovaginal prolapse with cervical lesion mimicked cervical carcinoma in the case described by Lim and colleagues, and surgery was performed, after which histology identified TB [Lim et al. 2012]. Vulval TB in one case was estimated as vulval carcinoma, and the patient underwent radical surgery, whereupon TB was found by histological investigation.

A 61-year-old postmenopausal woman who had undergone surgery and was treated with adjuvant chemotherapy for infiltrating ductal carcinoma of the breast 5 years previously, presented with bloody vaginal discharge, fatigue, weight loss, and low grade fevers at night for 2 months. Histological examination of the endometrium, done based on the suspicion of a second primary cancer due to the tamoxifen therapy, revealed a granulomatous reaction, Mtb was found by GeneXpert system [Neonakis et al. 2006].

Urolithiasis as a mask and comorbidity of UGTB

The same clinical features as well as laboratory and X-ray findings in urolithiasis and UGTB may conduce to misdiagnosis these diseases. Wong and colleagues [Wong et al. 2013] described a case of UGTB masquerading as a ureteral calculus. Gupta and colleagues [Gupta et al. 2013] had a patient who presented with bilateral urolithiasis and features of renal failure; he underwent left nephrectomy after thorough investigations. The biopsy revealed features of KTB. Later the patient underwent right ureteroscopic lithotripsy.

We described four cases of TB of the ureter, initially diagnosed as a stone. Ureteroscopy revealed an ulcer and biopsy was performed. Histology confirmed TB inflammation; later KTB 2 stage was found in all patients [Kulchavenya and Krasnov, 2010].

Prakash and colleagues have found a confusing picture of extensive renal and ureteral calcification due to TB [Prakash et al. 2013].

Misdiagnosed bladder tuberculosis

Bladder TB is rather often a complication of KTB, but its manifestation may be unusual and misguiding. Kumar and colleagues reported two cases of a TB cavity behind the bladder and prostate which initially eluded diagnosis, and were confirmed only after surgery [Kumar et al. 1994]. A typical situation for bladder TB was reported by Kaneko and colleagues [Kaneko et al. 2008]. A 24-year-old man experienced gross hematuria and dysuria several times a year from the age of 19, presenting to the urological department for the first time at age 21, when he was given standard antibiotic treatment for acute cystitis. Although urinary symptoms persisted, he failed to attend for follow up. He attended another clinic at the age of 24 with increased urinary frequency. Transrectal ultrasonography revealed thickening of the bladder wall, concavity of the right bladder neck, and nodular changes extending from the left bladder neck to the left bladder wall, and Mtb was detected in the urine. For a long time bladder TB was overlooked, and he was managed as a urinary tact infection (UTI) until the disease progressed up to the fourth stage.

Bladder TB stage 4 is unsuitable for conservative therapy; cystectomy with following enteroplasty is indicated. There is a risk of development a cancer of the neobladder [Lopes et al. 2013]. Lopes and colleagues presented a case of a 67-year-old patient with a history of augmentation ileocystoplasty 31 previously because of UGTB [Lopes et al. 2013]. Radiological investigations performed due to asymptomatic microscopic hematuria revealed three contrast-enhancing polyps within the neobladder. The patient underwent enterocystoprostatectomy and histopathological examination of the neobladder revealed mucinous adenocarcinoma in all three polyps, together with a prostatic adenocarcinoma Gleason 7 (3+4).

Spontaneous bladder perforation secondary to TB is very rare, and it diagnosis is often missed. Confirmation of TB via culture takes a long time and starting empirical treatment for TB is necessary. Kong and colleagues reported a young woman who presented with clinical features of a perforated appendix and was only diagnosed with bladder perforation during laparotomy [Kong et al. 2010]. She also had distal right ureteral stricture and left infundibular stenosis. The provisional diagnosis of TB was attained via typical histopathological features and a positive Mantoux test. Kumar and colleagues [Kumar et al. 1997] and Vallejo and colleagues [Vallejo et al. 1994] also described spontaneous bladder rupture secondary to UGTB.

Misdiagnosed TB of the urethra

Bouchikhi and colleagues reported an incredible case of UGTB in a man revealed by urethral narrowing and multiple urethroscrotal fistulas [Bouchikhi et al. 2013b]. The patient presented with dysuria, purulent discharge and a meatic penoscrotal fistula. A retrograde and voiding urethrocystography was performed and revealed an extended narrowing of the whole anterior urethra associated with multiple fistulous portions toward the scrotum and perineum. His condition was estimated as nonspecific sclero-inflammatory urethral stricture with complicating fistulas, and the patient underwent an urethroplasty. The wound healing was delayed and associated with the persistence of fistulas extending into the corpus cavernosum with purulent discharge. Only at that stage was TB suspected; multiple biopsies were then performed on the periurethral tissue and fistula tracts, and the histological examination confirmed the diagnosis. We suppose in fact in this case there was unrevealed KTB, as TB of the urogenital tract is a complication of KTB, according to classification. Careful estimation of the patient’s history and full examination of the urinary tract may help to reveal UGTB in time.

Misdiagnosed TB epididymitis

Rakototiana and colleagues had met with difficulty in the diagnosis of isolated testicular tuberculosis in two children [Rakototiana et al. 2009]. The clinical features had no specificity: one case of hydrocele and one case of acute scrotum inflammation. Surgical exploration showed testicular nodules in both cases. Only histological examination provided the definitive diagnosis.

A trauma may provoke the exacerbation of latent TB. The persistent hypertrophy of the right epididymis in young men had been regarded as a sequela of a recent trauma of the scrotum. The diagnosis of tuberculosis was confirmed by epididymal biopsy, and by intravenous urography which revealed a cavity in a left superior calix and above all by the presence of Mtb at bacteriological urine examination [Michel, 1990].

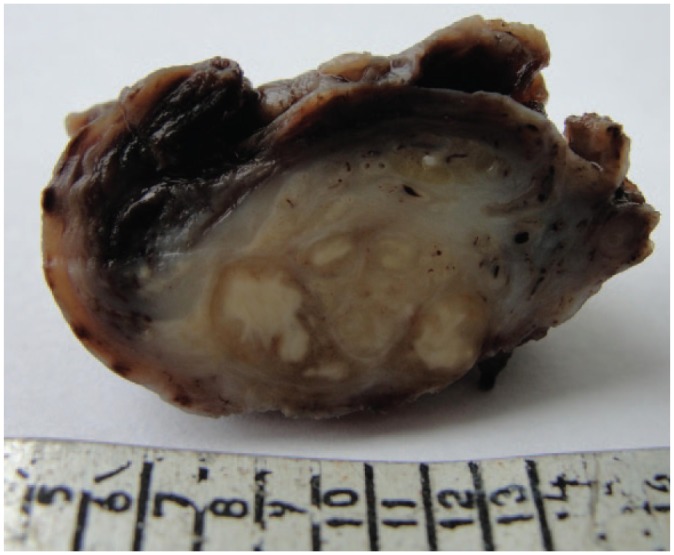

The typical picture of TB orchiepididymitis is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Caseous TB inflammation of the testis and epididymitis: section of operation material.

Misdiagnosed TB of the penis

Surprisingly, many authors report TB of the glans penis, and not only as a complication of BCG-therapy for superficial bladder cancer and bladder carcinoma [Chowdhury and Dey, 2013].

Cutaneous penile TB in an HIV-positive man masquerading as a sexually transmitted infection was confirmed by positive cultures [Stockamp et al. 2013]. Toledo-Pastrana and colleagues [Toledo-Pastrana et al. 2012] reported the case of a patient with ulcerous penile TB, presumably acquired through sexual intercourse. Kar and Kar have found primary TB of the penis in a 31-year-old man who presented with some ulcerated lesions on the glans penis [Kar and Kar, 2012]. Diagnosis was established as primary TB of the glans penis, confirmed by biopsy and supported by a strongly positive Mantoux test and positive TB polymerase chain reaction (PCR). There was no coexisting tuberculous infection elsewhere.

Also Sah and colleagues [Sah et al. 1999] revealed the case of a 60-year-old man who presented with multiple superficial ulcers on the glans penis. Histopathology, a positive tuberculin test result, and therapeutic response to anti-TB therapy confirmed the diagnosis of penile TB. Examination was otherwise normal except for a solitary enlarged reactive lymph node on the right side. Again there was no evidence of coexistent TB infection elsewhere.

Baskin and Mee [Baskin and Mee, 1989] reported a case of penis TB that presented as a subcutaneous nodule without superficial ulceration and Yonemura and colleagues [Yonemura et al. 2004] presented their experience of a case of penis TB that appeared as a scab on a nodule. A 56-year-old man presented with a 4-month history of a painless subcutaneous nodule at the glans penis. Pathological findings of the nodule showed granulomatous inflammation. Tuberculin tests were strongly positive, but Mtb could not be detected. Savu and colleagues [Savu et al. 2012] presented a case of penile tuberculosis with a bulky penoscrotal formation treated previously for the suspicion of Fournier gangrene.

Karthikeyan and colleagues [Karthikeyan et al. 2004] described a ‘water can’ penis caused by TB, which was misdiagnosed for a long time. Nakamura and colleagues [Nakamura et al. 1989] discovered 37 cases of TB of the penis in Japan in 10 years (between 1978 and 1987).

Misdiagnosed prostate TB

Otherwise isolated prostate TB is more often localization of UGTB. As an example a history case of a 65-year-old man was described. The patient presented with symptoms of frequency, dysuria and hesitancy, and 10 kg weight loss in the last 6 months, without pulmonary symptoms and negative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) test for HIV. Digital rectal examination (DRE) revealed a high volume, irregular and hard prostatic gland. Ultrasound investigation showed a prostatic volume of 39 cm3, without sign of malignity. Biopsy of the prostatic gland showed multiple granulomas and the Ziehl-Neelsen staining was positive for Mtb [López Barón et al. 2009].

Another case was of a 64-year-old man who presented with an obstructive syndrome of the low urinary tract. After clinical and biological examination, prostate cancer was highly suspected. Transrectal biopsy was performed and histological examination showed tuberculosis lesions [Rabesalama et al. 2010].

Fatal cases of UGTB

Renal TB is difficult to diagnose, because many patients present themselves with lower urinary symptoms which are typical of bacterial cystitis. Delayed diagnosis may have grave consequences, even fatal. The case of a young woman with renal TB was reported by Daher and colleague [Daher et al. 2007]. The patient was admitted with complaints of adynamia, anorexia, fever, weight loss, dysuria and generalized edema for 10 months. At physical examination she was febrile (39°C), and her abdomen had increased volume and was painful at palpation. Laboratory tests showed azotemia, leukocytosis, middle leukocyturia and proteinuria. She was also oliguric. Abdominal echography showed thick and contracted bladder walls and heterogeneous liquid collection in the left pelvic region. Two laparotomies were performed, in which abscess in pelvic region was found. Anti-TB treatment with rifampin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide was started. During the follow up, the urine culture was found to be positive for Mtb. The complex therapy was unsuccessful, and hemodialysis was then started. The computed tomography showed signs of chronic nephropathy, dilated calyces and thinning of renal cortex in both kidneys and severe dilation of the ureter. The patient developed neurologic symptoms, suggesting TB meningoencephalitis, and died despite of the supportive measures adopted [Daher et al. 2007].

Dadhwal and colleagues reported a rare case of TB flare in a 28-year-old nulliparous woman following endometrial aspiration, which drained 30 ml of pus [Dadhwal et al. 2009]. Following this, she developed high-grade fever with painful abdomen, guarding and rigidity. PCR was positive for mycobacterium and histopathology showed necrotizing granulomatous endometritis. She also showed features of FGTB and chronic TB meningitis.

TB of the renal artery as a cause of renovascular arterial hypertension

Bouziane and colleagues [Bouziane et al. 2009] have seen TB of the renal artery. A 17-year-old patient presenting with renovascular arterial hypertension, was revealed by the ultrasonography, when an occlusion of the right renal artery as well as pararenal and mesenteric polyadenopathy were found. The authors supposed TB etiology of both processes and anti-TB treatment had been carried out. In 1 month the right renal artery was revascularized with a right iliorenal bypass using reversed internal saphenous vein. The patient was operated on with an 18-month follow up. Arterial pressure was normal without antihypertensive treatment. This case is interesting, but diagnosis was not confirmed by histology nor bacteriology, so we doubt the TB etiology of this case.

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis due to tuberculosis

Granulomatous interstitial nephritis (GIN) is an uncommon form of acute interstitial nephritis. Sampathkumar and colleagues reported a young male who presented with a rapidly progressing renal failure and massive proteinuria [Sampathkumar et al. 2009]. A renal biopsy revealed GIN, and Mtb DNA was found in the biopsy specimen by PCR. The patient was started on anti-TB therapy and steroids besides 11 sessions of hemodialysis.

Discussion

UGTB has no specific pathognomonic clinical features; most common among them are pain (flank, perineal), dysuria, penal colic, hematuria, but its frequency is variable in different regions and at different times. Retrospective analysis clearly shows that almost all so-called ‘unusual’ and ‘rare’ cases of UGTB are normal, if the index of suspicion and familiarity with TB are high. Often in UGTB patients ultrasound and laboratory findings as well as clinical features are interpreted incorrectly, leading to misdiagnosis. We have to keep TB in mind in all cases of UTI, urogenital cancer, and stone disease, as UGTB may both mimic these diseases and combine with them. TB as a chronic inflammatory disease that may also be a predisposition to a cancer.

Conclusion

In fact UGTB is not a rare disease, but it is often an overlooked disease. There are two main reasons for delayed diagnosis: vague clinical features and low index of suspicion. We cannot ignore UGTB: late diagnosis always leads to loss of organ. UGTB is an infectious contagious disease, and this is one more reason for its early diagnosis. It is necessary to use all arsenals of bacteriology and histology to confirm UGTB.

Footnotes

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of interest statement: None of the contributing authors have any conflict of interest, including specific financial interests or relationship and affiliation relevant to the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Ekaterina Kulchavenya, Novosibirsk Research TB Institute, Urogenital Clinic, Novosibirsk Medical University, Okhotskaya 81-a, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation.

Denis Kholtobin, Novosibirsk Research TB Institute, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation Novosibirsk State University, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation.

References

- Androulaki A., Papathomas T., Liapis G., Papaconstantinou I., Gazouli M., Goutas N., et al. (2008) Inflammatory pseudotumor associated with Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Int J Infect Dis 12(6): 607–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badmos K. (2012) Tuberculous epididymo-orchitis mimicking a testicular tumour: a case report. Afr Health Sci 12(3): 395–397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin L., Mee S. (1989) Tuberculosis of the penis presenting as a subcutaneous nodule. J Urol 141(6): 1430–1431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchikhi A., Amiroune D., Tazi M., Mellas S., Elammari J., El Fassi M., et al. (2013a) Pseudotumoral tuberculous ureteritis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 7(1): 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchikhi A., Amiroune D., Tazi M., Mellas S., Elammari J., El Fassi M., et al. (2013b) Isolated urethral tuberculosis in a middle-aged man: a case report. J Med Case Rep 7(1): 97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouziane Z., Boukhabrine K., Lahlou Z., Benzirar A., el Mahi O., Lekehal B., et al. (2009) Tuberculosis of the renal artery: a rare cause of renovascular arterial hypertension. Ann Vasc Surg 23(6): 786.e7–786.e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury A., Dey R. (2013) Penile tuberculosis following intravesical Bacille Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy. Indian J Urol 29(1): 64–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colbert G., Richey D., Schwartz J. (2012) Widespread tuberculosis including renal involvement. Proc (Bayl Univ Med Cent) 25(3): 236–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dadhwal V., Gupta N., Bahadur A., Mittal S. (2009) Flare-up of genital tuberculosis following endometrial aspiration in a patient of generalized miliary tuberculosis. Arch Gynecol Obstet 280(3): 503–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daher E., Silva J., Damasceno R., Santos G., Corsino G., Silva S., et al. (2007) End-stage renal disease due to delayed diagnosis of renal tuberculosis: a fatal case report. Braz J Infect Dis 11(1): 169–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S., Santhosh R., Meitei K., Singh S. (2013) Primary genito-urinary tuberculosis with bilateral urolithiasis and renal failure-an unusual case. J Clin Diagn Res 7(5): 927–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiprakash P., Pai K., Rao L. (2013) Diagnosis of tuberculous cervicitis by Papanicolaou-stained smear. Ann Saudi Med 33(1): 76–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko T., Kudoh S., Matsushita N., Kashiwabara Y., Tamura T., Yoshida I., et al. (2008) [Case of bladder tuberculosis with onset at the age of nineteen–treatment of urinary tract tuberculosis in accordance with the new Japanese Tuberculosis Treatment Guidelines]. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 99(1): 29–34 (in Japanese). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kar J., Kar M. (2012) Primary tuberculosis of the glans penis. J Assoc Physicians India 60: 52–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karthikeyan K., Thappa D., Shivaswamy K. (2004) “Water can” penis caused by tuberculosis. Sex Transm Infect 80(1): 75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kho V., Chan P. (2012) Isolated tuberculous epididymitis presenting as a painless scrotal tumor. J Chin Med Assoc 75(6): 292–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong C., Ali S., Singam P., Hong G., Cheok L., Zainuddin Z. (2010) Spontaneous bladder perforation: a rare complication of tuberculosis. Int J Infect Dis 14(Suppl. 3): e250–e252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulchavenya E. (2014) Urogenital tuberculosis: definition and classification. Ther Adv Infect Dis 2(5–6): 117–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulchavenya E., Krasnov V. (2010) Selected Issues of Phthysiourology (monograph). Novosibirsk, Russia: Nauka. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R., Banerjee G., Bhadauria R., Ahlawat R. (1997) Spontaneous bladder perforation: an unusual management problem of tuberculous cystitis. Aust N Z J Surg 67(1): 69–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Srivastava A., Mishra V., Banerjee G. (1994) Tubercular cavity behind the prostate and bladder: an unusual presentation of genitourinary tuberculosis. J Urol 151(5): 1351–1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lakmichi M., Kamaoui I., Eddafali B., Sellam A., Dahami Z., Moudouni S., et al. (2011) An unusual presentation of primary male genital tuberculosis. Rev Urol 13(3): 176–178. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim P., Atan I., Naidu A. (2012) Genitourinary tuberculosis: an atypical clinical presentation. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol 2012: 3. doi: 10.1155/2012/727146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes F., Rolim N., Rodrigues T., Canhoto A. (2013) Intestinal adenocarcinoma in an augmented ileocystoplasty. BMJ Case Rep 13(3): 176–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López Barón E., Gómez-Arbeláez D., Díaz-Pérez J. (2009) Primary prostatic tuberculosis. Case report and bibliographic review. Arch Esp Urol 62(4): 309–313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel P. (1990) Urogenital tuberculosis revealed by scrotal trauma. Presse Med 19(31): 1454–1455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S., Aoki M., Nakayama K., Kanamori S., Onda S. (1989) Penis tuberculid (papulonecrotic tuberculid of the glans penis): treatment with a combination of rifampicin and an extract from tubercle bacilli (T.B. vaccine). J Dermatol 16(2): 150–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanjappa V., Suchismitha R., Devaraj H., Shah M., Anan A., Rahim S., et al. (2012) Vulval tuberculosis - an unusual presentation of disseminated tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India 60: 49–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neonakis I., Mantadakis E., Gitti Z., Mitrouska I., Manidakis L., Maraki S., et al. (2006) Genital tuberculosis in a tamoxifen-treated postmenopausal woman with breast cancer and bloody vaginal discharge. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob 5: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prakash J., Goel A., Sankhwar S., Singh B. (2013) Extensive renal and ureteral calcification due to tuberculosis: rare images for an uncommon condition. BMJ Case Rep 2013. DOI: 10.1136/bcr-2012-008508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabesalama S., Rakoto-Ratsimba H., Rakototiana A., Razafimahatratra R., Raherison R., Rantomalala H., et al. (2010) [Isolated prostate tuberculosis. Report of a case in Madagascar]. Prog Urol 20(4): 314–316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rakototiana A., Hunald F., Razafimanjato N., Ralahy M., Rakoto-Ratsimba H., Rantomalala H. (2009) [Isolated testicular tuberculosis in children. Report of 2 Malagasy cases]. Arch Pediatr 16(2): 112–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabita S., Sharmila V., Arun Babu T., Sinhasan S., Darendra S. (2013) A rare case of cervical tuberculosis which simulated carcinoma of the cervix. J Clin Diagn Res 7(6): 1189–1190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sah S., AshokRaj G., Joshi A. (1999) Primary tuberculosis of the glans penis. Australas J Dermatol 40(2): 106–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampathkumar K., Sooraj Y., Mahaldar A., Ramakrishnan M., Rajappannair A., Nalumakkal S., et al. (2009) Granulomatous interstitial nephritis due to tuberculosis-a rare presentation. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 20(5): 842–845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savu C., Surcel C., Mirvald C., Gîngu C., Hortopan M., Sinescu I. (2012) Atypical primary tuberculosis mimicking an advanced penile cancer. Can we rely on preoperative assessment? Rom J Morphol Embryol 53(4): 1103–1106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stockamp N., Paul S., Sharma S., Libke R., Boswell J., Nassar N. (2013) Cutaneous tuberculosis of the penis in an HIV-infected adult. Int J STD AIDS 24(1): 57–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toledo-Pastrana T., Ferrándiz L., Pichardo A., Muniaín Ezcurra M., Camacho Martínez F. (2012) Tuberculosis: an unusual cause of genital ulcer. Sex Transm Dis 39(8): 643–644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallejo G., Palacio E., Reig R., Raventos B., Morote R., Soler R. (1994) [Spontaneous bladder rupture secondary to urinary tuberculosis]. Actas Urol Esp 18(8): 829–832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong N., Hoag N., Jones E., Rowley A., McLoughlin M., Paterson R. (2013) Genitourinary tuberculosis masquerading as a ureteral calculus. Can Urol Assoc J 7(5–6): E363–E366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong S., Rizvi H., Cerio R., O’Toole E. (2011) An unusual case of vulval papulonecrotic tuberculid. Clin Exp Dermatol 36(3): 277–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) (2014) Global Tuberculosis Report 2014. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/137094/1/9789241564809_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Google Scholar]

- Yonemura S., Fujikawa S., Su J., Ohnishi T., Arima K., Sugimura Y. (2004) Tuberculid of the penis with a scab on the nodule. Int J Uro 11(10): 931–933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu-Hung L., Lu S., Yu H., Kuo Y., Huang C. (2009) Tuberculous epididymitis presenting as huge scrotal tumor. Urology 73(5): 1163.e5–1163.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]