Abstract

Background

Nearly every fourth person in Germany has an advance directive that is to be used in certain medical situations. It is questionable, however, whether advance directives truly influence important treatment decisions in the intensive care unit. We studied the extent to which doctors and patients’ relatives agree on the applicability of advance directives in the acute setting.

Methods

A prospective study was carried out by questionnaire among the physicians and relatives of 50 patients with advance directives who were hospitalized on four different multidisciplinary intensive care units. The answers of 25 residents in training, 14 senior physicians, and 19 relatives were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. The extent of agreement was assessed by means of Gwet’s AC1 with linear weighting.

Results

In most of the advance directives, the conditions under which they were meant to apply were stated in broad, general terms in prewritten blocks of text. 23 of the 50 patients (46%) died. All relatives stated that they were very familiar with the patients’ wishes; 18 of 19 were legally responsible for decision-making. In assessing whether the advance directive was applicable to the situation at hand, the strength of agreement between physicians and relatives as well as between the two groups of physicians was only fair and non-significant (0.35; 95% confidence interval [CI]: –0.01 to 0.71; p = 0.059 and 0.24; 95% CI: –0.03 to 0.50; p = 0.079). The relatives found the advance directives more useful than the doctors did (median, 5 vs. 3 [p = 0.018] on a Likert scale ranging from 0 [not useful at all] to 5 [very useful]) and favored their literal application (median, 5 vs. 4 [p = 0.018] on a Likert scale ranging from 0 [favoring the doctor’s interpretation] to 5 [favoring literal application]). 30 days after the decision, 13 relatives (68%) felt that the patient’s wishes had been fully complied with.

Conclusion

These groups’ clearly differing assessments of the applicability of advance directives imply that the currently most common types of advance directive are not suitable for use in intensive care. In order to support patients’ relatives in their role as surrogate participants in decision-making, improved advance directives should be developed, and their implementation should be incorporated into the training and continuing medical education of intensive-care physicians.

Almost one in four persons in Germany report that they have prepared an advance directive (1). Due to demographic changes, older, sicker patients are increasingly treated in intensive care units and as a result are more and more likely to die there. Advance directives are intended to guarantee an individual’s autonomy when that individual can no longer express himself or herself as a result of disease severity or treatment. Retrospective studies, however, show that advance directives in intensive care units have only a small effect on the management of life-sustaining treatment (2, 3). A retrospective data analysis found that although cardiopulmonary resuscitation was performed less frequently in patients who had an advance directive at the time of death there was no effect on the length of time spent in the ICU or on end-of-life treatment (2).

In intensive care units advance directives for patients who are unable to consent are binding for all those involved, provided they are valid. The representative—or, if the representative is absent or unavailable, the treatment team—must therefore first examine the directive’s validity (4). ICU doctors complain that advance directives are often too generally worded and are therefore rarely applicable to an ICU patient’s situation (5). To investigate this problem, we asked treating physicians and relatives of intensive care patients who were unable to consent to rate the validity of available advance directives.

Methods

Study design and conduct

A mixed-method study was conducted in four intensive care units (mixed surgical, cardiological, and neurological) of a university hospital, with a total of 72 beds, between September 2013 and March 2014. All ICU patients were screened on weekdays. Inclusion criteria were ICU stay lasting longer than 48 hours, loss of ability to consent as assessed by the treating senior physician, and availability of an advance directive. Senior physicians, residents in training, and next of kin were questioned in a structured interview including both closed and open questions within 48 hours of the patient’s inclusion in the study. All the interviews were conducted by one individual (NL). Answers to open questions were recorded and transcribed. Thirty days after the patients died or were discharged from the ICU we questioned the relatives again, by telephone, in a standardized interview. This procedure had been approved by the university hospital’s ethics committee (approval no. 3732–03/13).

For the primary question of how often advance directives were rated as valid, directives had to be rated as meeting at least one validity criterion. We also investigated the following points:

Were there differences between the assessments of those involved?

How were individual validity criteria rated?

What reasons were given for the assessments?

Were advance directives rated as helpful?

Should they be interpreted literally?

How did relatives rate the implementation of patients’ wishes 30 days later?

The development of the guideline for conducting the interviews is described in the eBox. The questionnaires are also available as part of the supplementary material (eQuestionnaires).

ebox. Interview compilation and conduct.

-

Methods

The guideline for the structured interview for this study was developed in several stages. In order to guarantee that the content of the questions was valid, the drafts were discussed with senior physicians of intensive care units and the chair of the clinical ethics committee of the University Hospital of Jena. An initial draft was compiled on the basis of an earlier retrospective study by the authors (2) and examination of 10 advanced directives of patients in the ICU. It contained the validity criteria in the form of pre-established categories. A preliminary test with ICU doctors based on five specific cases showed that the procedure did not do justice to individual advance directives

The second draft of the guideline was therefore modified so that the participants were presented with an exact copy of the validity criteria and the patients’ wishes regarding their treatment. The questions in the guideline were presented orally and audio recordings of the interviews were made. The guideline and the procedure were tested again using five specific cases, with ICU doctors and relatives. With the exception of individual questions that were redrafted, no further changes were needed. This testing procedure guaranteed the face validity of the questions and that the interview was suitable for use.

-

Qualitative evaluation of open comments

The audio recordings of open comments were transcribed and imported into a computer program for qualitative data analysis (e1). The categories were established as inductive, structured, qualitative content analysis (e2). NL and JH, 10th-semester medical students, developed the categories through dialogue and consensus and evaluated the findings.

In a second step, CSH examined the categories. These were then jointly reworked until consensus was achieved.

Data evaluation

Advance directives were analyzed with regard to type of text (template or free text), type of validity criteria, and treatment wished or refused. The patients’ data was taken from their electronic patient records. Cross-classified tables were drawn up to compare how validity was rated by doctors and relatives on the one hand, and by senior physicians and residents on the other. Gwet’s AC1 (6) with linear weighting (7) was calculated as a measure of agreement. Senior physicians’ assessments were used in comparison of doctors and relatives, and missing interviews were replaced by information on the same patient provided by residents. Doctors’ and relatives’ answers on a scale were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Comments were transcribed and qualitatively evaluated (eBox). Relatives’ and doctors’ demographic characteristics were described using descriptive statistics, and the judgements of resident and senior physicians were compared using Fisher’s exact test or the chi-square test.

Results

Patients, advance directives, and interview partners

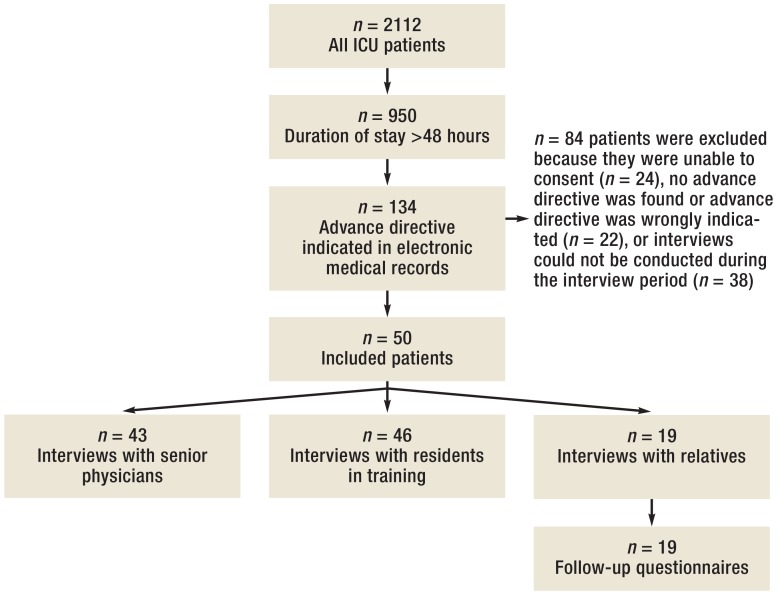

Of 2112 patients treated in the ICU during the study period, 134 met the inclusion criteria. For 50 of these, advance directives were available and relatives could be interviewed (Figure 1). Patients were mostly male and a median of 71.5 years old. The most common grounds for admission were medical. At the time of questioning, approximately two-thirds of the patients were receiving mechanical ventilation, 29 (58%) through a tube and four (8%) via a tracheostomy. Life-sustaining measures were limited in 56% of patients (Table 1). The ICU mortality rate was 46%. A median of three days elapsed between ICU admission and the point at which an advance directive documented in the patient’s medical records became available. Without exception, all advance directives contained a form of rejection of life-sustaining measures; 39 (78%) consisted of prewritten sections of text or fields to be checked, while the remainder were written independently by their authors. However, these often also contained standard wordings. Most advance directives met three or four validity criteria; one met as many as eight (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram

ICU, Intensive care unit

Table 1. Overview of patients.

| Patients: n (%) | 50 (100) |

| Age: median (IQR) | 71.5 (62.5 to 82) |

| Male: n (%) | 36 (72) |

| SAPS II score: median (IQR) | 42 (33 to 54.25) |

| Length of stay, days: median (IQR) | 18 (10 to 26) |

| Days from ICU admission to actual availability of an advance directive recorded in patient records: median (IQR) | 3 (1 to 6) |

| Grounds for admission: n (%) | |

| Medical elective | 5 (10) |

| Medical emergency | 29 (58) |

| Surgical elective | 9 (18) |

| Surgical emergency | 7 (14) |

| ICU treatment at time of survey: n (%) | |

| Analgesics | 47 (94) |

| Nutrition, parenteral or via tube | 42 (84) |

| Antibiotics | 40 (80) |

| Vasopressors | 29 (58) |

| Intubation and ventilation | 29 (58) |

| Ventilation via tracheostomy | 4 (8) |

| Sedation | 23 (46) |

| Renal replacement therapy | 13 (26) |

| Blood products | 10 (20) |

| Extracorporeal circulation | 5 (10) |

| Pacemaker | 3 (6) |

| Treatment restrictions during ICU treatment: n (%) | |

| None | 23 (46) |

| DNR/DNI | 14 (28) |

| Withhold | 2 (4) |

| Withdraw | 11 (22) |

| Following discharge: n (%) | |

| Died in ICU | 23 (46) |

| Rehabilitation facility | 10 (20) |

| Normal ward | 16 (32) |

| Care home | 1 (2) |

IQR: interquartile range; ICU: intensive care unit; SAPS: Simplified Acute Psychology Score; DNR/DNI: do not resuscitate/do not intubate

Table 2. Advance directives.

| Total, n (%) | 50 (100) |

| Content | |

| Free text | 11 (22) |

| Prewritten (prepared text with options to check) | 39 (78) |

| Organ donors | 3 (6) |

| Organ donation in contradiction of rejection of LSM?*1 | 2 (4) |

| Medical care proxy | 49 (98) |

| Validity criteria categories | |

| Serious long-term brain damage | 25 (50) |

| Coma with no prospect of regaining consciousness | 34 (68) |

| Lasting loss of vital body functions | 24 (48) |

| Inevitable death | 37 (74) |

| End stage of disease | 25 (50) |

| Dementia, mental confusion | 14 (28) |

| No dignified existence | 5 (10) |

| Other*2 | 10 (20) |

| No. of validity criteria | |

| 1 to 2 | 8 (16) |

| 3 to 4 | 31 (62) |

| 5 to 6 | 10 (20) |

| 8 | 1 (2) |

| No. of advance directives in which LSM rejected in writing | 50 (100) |

LSM: life-sustaining measures

*1Written consent for organ donation contradicts written rejection of life-sustaining measures.

*2This includes wording such as “comparable conditions not specifically mentioned here,” “very severe physical suffering.”

It proved impossible to contact 28 of the relatives within the time window, and three refused to participate. Interviews were conducted in person with 19 relatives and by telephone with eight, in line with their own wishes. Most relatives were female (84%), spouses or life partners (68%), with a median age of 62 years. Eighteen were authorized to act as proxies to arrange medical care. All relatives stated that they were very familiar with the patient’s wishes. All the relatives were successfully contacted after 30 days. Of those questioned, 13 (68%) declared that the patient’s wishes had been followed during their ICU treatment. However, only two advance directives were assessed as suited to ICU treatment by relatives and doctors (Table 3).

Table 3. Relatives.

| Total, n (%) | 19 (100) |

| Age: median (IQR) | 62(51.5 to 71.5) |

| Female: n (%) | 16 (84.2) |

| Relationship to patient: n (%) | |

| Spouse or life partner | 13 (68.4) |

| Mother or father | 0 (0) |

| Daughter or son | 5 (26.3) |

| Other | 1 (5.3) |

| Schooling: n (%) | |

| School not graduated | 1 (5.3) |

| Regular school | 4 (21.1) |

| Graduated from grammar school | 12 (63.2) |

| College/university degree | 2 (10.5) |

| Medical care proxies | 18 (94.7) |

| Knowledge of patient’s wishes | |

| “How well do you know the patient’s wishes, for example from conversations with him/her, on a scale from 0 (not at all) to 5 (very well)?” n = 15* | 5.0 (5.0 to 5.0) |

| 30-day follow-up | |

| “Were the patient’s wishes followed during treatment in the intensive care unit?” | |

| Yes | 13 (68.4) |

| No | 1 (5.3) |

| Partly | 4 (21) |

| Unsure | 1 (5.3) |

IQR: interquartile range

*This question was added to the interview at a later point in time

Senior physicians (n = 14) were older (p = 0.036) and more experienced with advance directives in their daily work (p = 0.003) than residents (n = 25). Only two senior physicians and three residents had prepared an advance directive or arranged a medical care proxy themselves (eTable 1).

eTable 1. Doctors.

| Residentsn = 25 n (%) | Senior physiciansn = 14 n (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age >30 | 18 (72) | 14 (100) | 0.036 |

| Female | 8 (32) | 2 (14.3) | 0.279 |

| How much experience with advance directives have you had in your day-to-day work? | |||

| Not much | 8 (32) | 1 (7.1) | 0.003 |

| Some | 10 (40) | 1 (7.1) | |

| A lot | 7 (28) | 12 (85.7) | |

| Do you have an advance directive yourself? | |||

| Yes | 2 (8) | 2 (14.3) | 0.609 |

| Do you have a medical care proxy yourself? | |||

| Yes | 2 (8) | 3 (21.4) | 0.329 |

Rating of advance directives

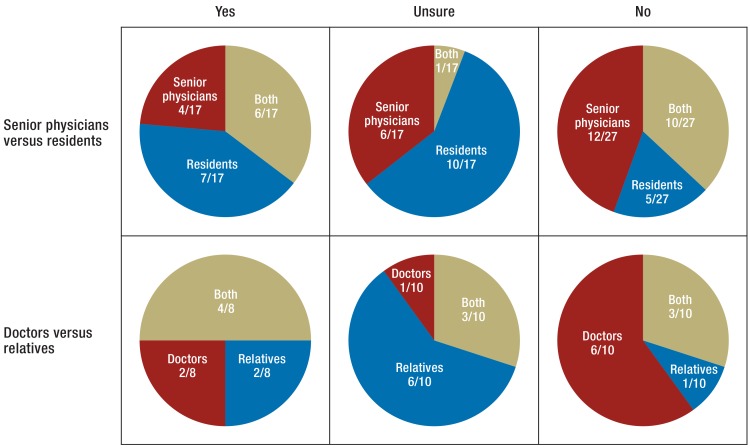

The assessments of senior physicians were available for 43 advance directives, those of residents for 46, and those of relatives for 19. The assessments of residents and senior physicians could be compared in 39 cases, and those of relatives and doctors in 19 cases. Doctors declared 17 of 39 advance directives valid when questioned, but only six were rated as valid by both senior physicians and residents (Figure 2). Assessment of advance directive validity by senior physicians and residents matched slightly, but insignificantly (AC1 = 0.24; 95% confidence interval [95% CI]: –0.03 to 0.50; p = 0.079). When individual validity criteria were rated, doctors showed substantial agreement (AC1 = 0.7; 95% CI: 0.61 to 0.79; p =0.001). Of the 153 validity criteria, 25 were rated satisfactory, but only five were rated so by both groups (Table 4). When the assessments of doctors and relatives were compared, it was found that although eight advance directives were declared valid only four were declared so by both parties (Figure 2, Table 4). Of a total of 82 individual validity criteria, 22 were described as having been met, but assessments coincided in only six of these cases (Table 4) (AC1 for comparison of doctors and relatives found 0.35; 95% CI: –0.01 to 0.71; p = 0.059 and 0.38; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.56; p =0.001 respectively). This indicated a slight degree of agreement (7).

Figure 2.

Agreement on validity of available patient advance directives

An advance directive could be rated as valid (“Yes”), invalid (“No”), or unsure. This figure compares the evaluations given by residents in training versus senior physicians and of doctors versus relatives. “Both” indicates agreement between evaluations. Specifically, there was only slight, insignificant agreement between residents’ and senior physicians’ evaluations of advance directive validity (AC1 = 0.24; 95% confidence interval: –0.03 to 0.50; p = 0.079). There was only fair, insignificant agreement between doctors’ and relatives’ evaluations (AC1 = 0.35; 95% confidence interval: –0.01 to 0.71; p = 0.059)

Table 4. Comparison of assessments of individual advance directives and the validity criteria they meet.

| A.Advance directive validity | ||||

| Residents | ||||

| Senior physicians | No | Unsure | Yes | Total |

| No | 10 | 8 | 4 | 22 |

| Unsure | 3 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Yes | 2 | 2 | 6 | 10 |

| Total | 15 | 11 | 13 | 39 |

| B Validity of individual validity criteria | ||||

| Residents | ||||

| Senior physicians | No | Unsure | Yes | Total |

| No | 97 | 19 | 11 | 127 |

| Unsure | 9 | 3 | 3 | 15 |

| Yes | 4 | 2 | 5 | 11 |

| Total | 110 | 24 | 19 | 153 |

| C Advance directive validity | ||||

| Relatives | ||||

| All doctors* | No | Unsure | Yes | Total |

| No | 3 | 5 | 1 | 9 |

| Unsure | 0 | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 4 | 6 |

| Total | 4 | 9 | 6 | 19 |

| D Validity of individual validity criteria | ||||

| Relatives | ||||

| All doctors | No | Unsure | Yes | Total |

| No | 29 | 25 | 11 | 65 |

| Unsure | 0 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| Yes | 1 | 1 | 6 | 8 |

| Total | 30 | 32 | 20 | 82 |

The assessments of residents and senior physicians concerning the validity of advance directives matched slightly but insignificantly (A: AC1 = 0.24; 95% confidence interval [CI]: –0.03 to 0.50; p = 0.079). In contrast, there was substantial agreement regarding individual validity criteria (B: AC1 = 0.70; 95% CI: 0.61 to 0.79; p ≤0.001). There was slight agreement between the assessments of doctors and relatives regarding both advance directive validity (C: AC1 = 0.35; 95% CI: –0.01 to 0.71; p = 0.059) and individual validity criteria (D: AC1 = 0.38; 95% CI: 0.20 to 0.56; p ≤0.001).

*Senior physicians’ evaluations were used (n = 17). Where these were unavailable, those of residents were used (n = 2).

Doctors explained the reasons for their assessments of advance directive validity in 78 of the questionnaires. Of these comments, 60 concerned the patient’s state of health or likely prognosis, while 17 concerned unclear or excessively general wording in the advance directive. Turning to relatives, 13 gave reasons for their assessments, five could not state the patient’s wishes in their current situation on the basis of the advance directive, and three were guided by doctors’ opinions (eTable 2).

eTable 2.

| A Reasons given for the evaluation of validity | |||||

| Residents, n | Senior physicians, n | Relatives, n | Examples | ||

| Total | 43 | 35 | 13 | ||

| State of health or likely prognosis | 30 | 30 | “Treatment aim exists”; “Currently comatose but is likely to awaken”; “Has infavorable prognosis” | ||

| Advance directive unclearly worded | 12 | 5 | “What is a decent life?”; “Notarized, legally not bad, medically completely unworkable”; “What is severe, long-term damage?”; “What does “vitally important” mean?”; “It’s hard to define “incurable” here, too […] You can’t cure a stroke, but that doesn’t mean you can’t live with it.” | ||

| Patient’s wishes in the situation in question cannot be inferred from advance directive | 5 | “I can’t tell you that. My husband’s been asleep since his surgery.”; “I can’t say, this is the first time this has happened to us”; “We don’t want to let her starve” | |||

| Advance directive valid/invalid | 4 | “That definitely doesn’t apply”; “Been caring for him for seven years, wishes stated in advance directive” | |||

| Hope and patience | 3 | “Hope, hope, hope […]” | |||

| Inclined towards doctors’ opinion | 3 | “The doctors say things are moving in the right direction” | |||

| B How helpful is the advance directive? | |||||

| Residents, n | Senior physicians, n | Relatives, n | Examples | ||

| Total | 44 | 38 | 16 | ||

| Advance directive provides additional information | 17 | 4 | “This is important for the doctor, to read about the patient’s wishes in a situation like this” (RES); “OK, it’s a template. But because you see this kind of wording a lot, you know that ultimately he doesn’t want his life prolonged if there’s no more chance of recovery or there’s no more chance of making contact with the outside world and actively taking part in life” (SP) | ||

| Advance directive gives binding instructions | 8 | 5 | 8 | “Because I’m not the only one who has to decide. If the situation arose, I’d know what he wanted” (REL); “[The advance directive] describes exactly the situation he’s in now and he’s said exactly what he wants” (SP) | |

| Wording of advance directive too general or contradictory | 14 | 15 | “The wording’s too general. Advance directives don’t usually describe the situations that arise at the end of life” (SP); “Not very helpful, some of the wishes expressed contradict each other” (RES) | ||

| Aids dignified death | 3 | “If there’s no chance any more that they can do anything, that this can be turned off” (REL) | |||

| Puts decision in the hands of relatives | 3 | “If you’re alone, just like her at the moment, and didn’t have something like this, someone from the state would come along” (REL) | |||

| Ambivalent due to difficult decisions | 3 | “Although I know he wouldn’t want to be kept hooked up to machines forever, he’s always said that, it’s still very difficult for me now to say it’s what he would have wanted” (REL) | |||

| Other | 2 | 4 | Consensus with physicians required; patients do not understand the options they check in advance directives; relatives do not implement advance directive; advance directive is superfluous following surgery | ||

| Not applicable | 6 | 12 | |||

| C Should written patient wishes be implemented? | |||||

| Residents, n | Senior physicians, n | Relatives, n | Examples | ||

| Total | 13 | 10 | 4 | ||

| No | 6 | 2 | “Advance directive not applicable”; “Tracheotomy will improve his quality of life” | ||

| Yes | 2 | 7 | 2 | “No doubt”; “My personal opinion, but no consensus with relatives”; “Yes, but no consensus with doctors” | |

| Sometimes/unsure | 5 | 1 | 2 | “Symptoms are controlled, for everything else wait until advance directive is applicable” (RES); “Advance directive unclear: what is life-sustaining?” (RES); “Unclearly worded” (SP); “First consult with doctors again—I don’t want to have him deliberately killed, either” | |

| D Relatives on whether patients’ wishes were followed, 30 days later | |||||

| Were the patients’ wishes followed? | Comments | ||||

| Yes, completely | “Very satisfied […] Treatment decisions made well […]” | ||||

| Yes, completely | “Belatedly, but yes. In the end I have to say it was all right. […] because so much has happened in the meantime […] So it was implemented correctly, I have to say” | ||||

| Yes, completely | “We do still feel conflicted sometimes […] are we doing it right […]. And if I’d known how much was riding on it, I mean, absolutely everything was affected […] he’s changed hugely. Yes, it’s a turning point […] but he’s still alive. So yes, they were followed” | ||||

| No | “Not really…what was written down wasn’t enough. […] because she said yes, if it comes to that, I’d prefer to die […] I could have lived with it if I’d said I wanted to assert her wishes like that, I wouldn’t have known anything about the other thing […] but you have to say, too, from the form there’s nothing you can criticize them [doctors] for, they have to cover themselves too […] so if this is not done she will die, but if it is, she won’t [referring to consent for craniectomy following cerebral hemorrhage]… also, my mother now [says] she’d want to be alive still […] [in the past] she’d have rejected that condition […] she can’t do anything for herself anymore” | ||||

| Partly | “In her advance directive she refused life-sustaining measures and certainly didn’t note everything down that specifically […] I talked with my mother and she told me she wouldn’t have wanted it the way it turned out […] I’d have to say now that my mother should have died […] in retrospect I’d say they shouldn’t have done the tracheotomy […] definitely if it had all gone the way the doctor said, that she’d already got better by that point, then it would definitely have been all right and she would have agreed, too. […] it’s been very hard for me too, and I’m not a doctor who has to decide everything. But I must say what nobody really knows before, quality of life didn’t come back, like the doctor said. There’s been no improvement so far, my mother’s in the care home and she still has the tube in her. It didn’t go the way it should have” | ||||

RES: resident; SP: senior physician; REL: relative

Handling advance directives, follow-up

The answers of 17 doctor–relative pairs to the question of how literally an advance directive should be followed were evaluated. Relatives gave a median answer of 5 (interquartile range [IQR]: 3 to 5), and doctors a median answer of 3 (IQR: 1 to 4; p = 0.018). The scale ranged from 0 (according to the doctor’s interpretation) to 5 (literally). On the question of how helpful the advance directive was for the treatment decisions being faced, again 17 doctor–relative pairs provided comments, and these were evaluated. This scale ranged from 0 (not at all helpful) to 5 (very helpful). Relatives gave a median answer of 5 (IQR: 4 to 5), and treating physicians 4 (IQR: 2 to 5; p = 0.018). Doctors made comments in 82 interviews. Of these, 29 comments rated the advance directives as having excessively general wording or contradictory wording, 21 rated them as a source of additional knowledge concerning the patient, and 13 as a binding guide to treatment. Of the 13 relatives who stated their reasons, eight saw the advance directive as binding, three as helpful for a dignified death, and three as a means to put the choice of treatment in the hands of relatives. Three relatives complained of the difficulty of the decision. Doctors who had rated an advance directive as valid or uncertain were asked whether they experienced personal conflict when implementing the patient’s wishes. This question was answered by 22 doctors; 19 answered negatively, and three positively. Statements concerning the applicability of patients’ written wishes were made by 23 doctors and four relatives. Five treating physicians and three patient representatives were unsure or considered the wishes only partly applicable (eTable 2).

For 38 of the advance directives, doctors gave an assessment of whether it would have been helpful for the advance directive to be available when the patient was admitted to the ICU: 64% answered negatively, and 11% positively. For the other cases this question was not applicable, as the advance directives had been available.

After 30 days 13 (68%) of relatives said yes when asked whether the patient’s wishes had been fully implemented in the ICU. Only one person stated that the patient’s wishes had not been followed (Table 3). Comments illustrate the following problems on the part of relatives (eTable 2):

Responsibility for life and death (“I’d have to say now that [she] should have died.”)

Unclear wording of advance directive (“what was written down wasn’t enough.”)

Altered normality (“He’s […] changed hugely […] but he’s still alive.”)

Change in the patient’s perspective (“[…] my mother now [says] she’d want to be alive still.”)

Discussion

This study is the first to investigate how relatives and treating physicians rated the validity of an available advance directive in a particular situation. The judgements regarding an advance directive or individual validity criteria, both of different groups of doctors and of treating physicians and relatives, coincided in only half the cases. Previous observational studies have shown that an advance directive has only a small effect on end-of-life treatment. However, neither doctors’ nor relatives’ judgement of advance directives had been investigated (2, 3, 8, 9). In contrast, the authors of a large US cohort study concluded that treatment of patients who were unable to consent at the end of life was more likely to comply with the patients’ wishes if patients had an advance directive (10). However, this finding was subject to criticism, as relatives’ assessments were given after a delay: a median of approximately13 months later (11).

Reasons for the low level of agreement between assessments

ICU doctors tend to interpret the spirit of advance directives, whereas relatives understand them literally. Doctors often describe the wording used in advance directives as unclear, contradictory, and not applicable to the actual medical situation. The written content of advance directives usually consisted of prewritten sections of text that were imprecise or contradictory and in critical cases insufficient to determine their validity unambiguously in view of ICU patients’ complex clinical conditions and uncertain prognoses. A similar finding was reached in a small survey of ICU doctors (5). Advance directives tended to serve doctors as a guideline, and in particular they provided additional knowledge concerning the patient. For the treatment decisions to be taken, however, they were rated as of little use. It therefore comes as no surprise that only a minority of the doctors have prepared an advance directive themselves.

On the one hand ICU patients’ relatives have great respect for the signed directive and want to implement it literally, but on the other hand advance directives fail because the ways in which they are worded do not help relatives make decisions or provide them with instructions. Although relatives know patients’ wishes precisely from discussion and generally find an advance directive helpful, comments show that its applicability is often impossible to ascertain with certainty in the specific situation faced. Relatives find it very challenging to bring their own needs into line with the patient’s wishes (12). They often suffer considerable psychological after-effects for long periods (13).

Senior physicians, who are usually older and tend to have more experience with intensive care, rated advance directives differently from residents undergoing specialist training. In an earlier study involving a questionnaire, which was based on a hypothetical case with an available advance directive, doctors and nurses also rated applicability differently from each other (14). There are many reasons for the differences in assessments, including personality and sex. A lack of training in palliative care as part of initial training and continuing medical education was also mentioned. Issues relating to palliative care play too small a role in the training provided to students (15). Because such issues are becoming increasingly important in an aging society, they should also be part of specialist training in intensive care medicine (16).

Low levels of conflict

In this study, after 30 days 68% of relatives answered that ICU treatment had fully complied with the patient’s wishes. This suggests that a consensus between those involved may have developed subsequently. Determining and interpreting the patient’s wishes is a joint task for treating physicians and patient representatives. Conversations with relatives as part of a dialogue-based process are particularly helpful in this (17). Trusting dialogue can also provide emotional support for the relatives (17). Relatives’ retrospective satisfaction is therefore probably also affected by the quality of such conversations. Physicians expressed few potential conflicts when individual patient wishes were implemented. Concerns relating to medical law, such as those mentioned in earlier surveys (18), were not raised. This may be taken as a sign that advance directives have become part of daily practice in ICUs since those earlier surveys were conducted.

Appropriate advance directives for ICUs

Although the actual situation cannot usually be predicted precisely, the findings of this study suggest it would be desirable for individuals to prepare advance directives that are assessed in the same way by all those involved in the event of ICU treatment and are directly applicable. Advance care planning (ACP) may be suitable for developing informed preferences for specific scenarios, discussing them with relatives, and documenting them. However, this requires qualified and, where appropriate, longer-term consultation discussions (19). An ACP program has already been successfully implemented in German nursing homes for the elderly (20). French intensive care doctors presented films showing scenarios they had faced in the ICU to individuals aged over 80 years and then asked them what their wishes were. Up to two-thirds of the participants refused mechanical ventilation or renal replacement therapy following a complication during intensive care (21). The majority of intensive care doctors who were asked about these scenarios tailored their treatment recommendations to the participants’ wishes (22).

Study strengths and weaknesses

The extent to which the inquiries made in this study can be generalized is limited, as although they were conducted in multidisciplinary ICUs they were conducted in only one hospital. The documented opinions provide only a snapshot at a single point in time, and subsequent changes resulting from clinical alterations have not been taken into account. The strengths of the study are its use of qualitative and quantitative procedures and the summary of the wording of the clauses that were prepared and made available for the inquiries.

Key Messages.

Relatives and doctors differed in their ratings of half the advance directives.

While patient representatives tend to interpret advance directives literally, treating physicians do so more freely.

In an acute situation, the patient’s wishes often cannot be clearly deduced from the written content of an advance directive.

In view of the increasing use of intensive care, more appropriate advance directives are needed.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Caroline Shimakawa-Devitt, M.A.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

Ms. Leder received a doctoral grant from the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research (IZKF, Interdisziplinäres Zentrum für Klinische Forschung), University Hospital of Jena for this study.

The study was partly financed by the Center for Sepsis Control and Care, University Hospital of Jena, which is funded by Germany’s Federal Ministry of Education and Research: no. FKZ 01EO1002.

The other authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

We would like to thank Prof. Randall J. Curtis (University of Washington, Seattle, USA), Dr. Birgit van Oorschot (University Hospital of Würzburg), Dr. Ulrike Skorsetz (Ethics Committee Chair, University Hospital of Jena), and Dr. Heike Hoyer (Institute of Medical Statistics, Computer Sciences and Documentation, University Hospital of Jena) for their valuable support in planning this study. We would also like to thank Julia Hase for collaborating on subject-related analysis of the comments.

References

- 1.Deutsche Schlaganfall-Hilfe. Umfrage: Immer mehr Deutsche erstellen Patientenverfügung. www.schlaganfall-hilfe.de/patientenverfuegung. (last accessed on 15 June 2015) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartog CS, Peschel I, Schwarzkopf D, et al. Are written advance directives helpful to guide end-of-life therapy in the intensive care unit? A retrospective matched-cohort study. J Crit Care. 2014;29:128–133. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Halpern NA, Pastores SM, Chou JF, Chawla S, Thaler HT. Advance directives in an oncologic intensive care unit: a contemporary analysis of their frequency, type, and impact. J Palliat Med. 2011;14:483–489. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jannsens U, Burchardi H, Duttge G, et al. Therapiezieländerung und Therapiebegrenzung in der Intensivmedizin. Positionspapier der Sektion Ethik der Deutschen Interdisziplinären Vereinigung für Intensiv- und Notfallmedizin (DIVI) 2012;3:103–107. doi: 10.1007/s00101-012-2126-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Langer S, Knorr JU, Berg A. Umgang mit Patientenverfügungen: Probleme durch pauschale Formulierungen. Dtsch Arztebl. 2013;110:2186–2188. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gwet KL. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. Br J Math Stat Psychol. 2008;61:29–48. doi: 10.1348/000711006X126600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33:159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Rietjens JA, van der Heide A. The effects of advance care planning on end-of-life care: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2014;28:1000–1025. doi: 10.1177/0269216314526272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kish Wallace S, Martin CG, Shaw AD, Price KJ. Influence of an advance directive on the initiation of life support technology in critically ill cancer patients. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2294–2298. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gillick MR. Reversing the code status of advance directives? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1239–1240. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1000136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenker Y, Crowley-Matoka M, Dohan D, Tiver GA, Arnold RM, White DB. I don’t want to be the one saying ’we should just let him die’: intrapersonal tensions experienced by surrogate decision makers in the ICU. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27:1657–1665. doi: 10.1007/s11606-012-2129-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome-family. Crit Care Med. 2012;40:618–624. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318236ebf9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thompson T, Barbour R, Schwartz L. Adherence to advance directives in critical care decision making: vignette study. BMJ. 2003;327 doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7422.1011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weber M, Schmiedel S, Nauck F, Alt-Epping B. Knowledge and attitude of final-year medical students in Germany towards palliative care - an interinstitutional questionnaire-based study. BMC Palliat Care. 2011;10 doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-10-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiese CH, Vagts DA, Kampa U, et al. [Palliative care oriented therapy for all patients : recommendations of an expert circle] Anaesthesist. 2012;61:529–536. doi: 10.1007/s00101-012-2025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borasio GD. Das Patientenverfügungsgesetz und die medizinische Praxis. In: Borasio GD, Hessler HJ, Jox RJ, Meier C, editors. Patientenverfügung: Das neue Gesetz in der Praxis. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer; 2012. pp. 26–36. [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Oorschot B, Lipp V, Tietze A, Nickel N, Simon A. [Attitudes on euthanasia and medical advance directives] Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2005;130:261–265. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lund S, Richardson A, May C. Barriers to advance care planning at the end of life: an explanatory systematic review of implementation studies. PLoS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.In der Schmitten J, Lex K, Mellert C, Rotharmel S, Wegscheider K, Marckmann G. Implementing an advance care planning program in German nursing homes: results of an inter-regionally controlled intervention trial. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2014;111:50–57. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philippart F, Vesin A, Bruel C, et al. The ETHICA study (part I): elderly’s thoughts about intensive care unit admission for life-sustaining treatments. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1565–1573. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2976-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrouste-Orgeas M, Tabah A, Vesin A, et al. The ETHICA study (part II): simulation study of determinants and variability of ICU physician decisions in patients aged 80 or over. Intensive Care Med. 2013;39:1574–1583. doi: 10.1007/s00134-013-2977-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- e1.Huang R. Rqda: R-based qualitative data analysis. R package version 0.2-2. 2011. rqda.r-forge.r-project.org. (last accessed on 20 September 2012) [Google Scholar]

- e2.Kuckartz U. Methoden, Praxis. Computerunterstützung. Weinheim, Basel: Beltz Juventa; 2012. Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse. [Google Scholar]